Abstract

Using existing prognostic models, including the Graded Prognostic Assessment (GPA), it is difficult to identify patients with brain metastases (BMs) who are not likely to survive 2 months after whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT). The purpose of this study was to identify a subgroup of patients who would not benefit clinically from WBRT. We retrospectively reviewed the records of 111 patients with BMs who were ineligible for surgery or stereotactic irradiation and who underwent WBRT between March 2013 and April 2016. Most patients were scheduled to receive a total dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Non–small cell lung cancer represented the most common primary cancer type (67%), followed by breast cancer (12%). Median survival time (MST) was 109 days (range, 4–883). Univariate analysis identified five factors significantly associated with poor prognosis: performance status (PS) 2–4, perilesional edema, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), using steroids during WBRT, and presence of hepatic metastases. Multivariate analysis confirmed elevated LDH (>300 IU/l) as an independent predictor. MST for LDH >300 IU/l (n = 30) and LDH ≤300 IU/L (n = 87) cohorts were 47 days and 148 days, respectively (P < 0.001). MSTs for GPA 0–1 patients (n = 85) with and without elevated LDH were 37 days and 123 days, respectively (P < 0.001). More than half of the patients with GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH died within two months. Adding elevated LDH to the GPA will permit identification of patients with BMs who have extremely unfavorable prognoses.

Keywords: whole-brain radiotherapy, palliative radiotherapy, prognostic factors, brain metastases

INTRODUCTION

Estimates suggest that 20–40% of patients with malignant neoplasms develop brain metastases (BMs) during their illness [1]. The lung is the most common primary site leading to BMs, followed by the breast [2].

Whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is a standard treatment used to improve neurologic deficits caused by the BMs and surrounding edema, and to prevent further deterioration of neurologic function for patients with BMs who are not suitable for surgical resection or stereotactic irradiation (STI). The WBRT response rate ranges from 40 to 60%, and the median survival time (MST) ranges from 3 to 6 months [3–9]. Potential risks of WBRT include hair loss, nausea, and neuro-cognitive deficits. The Quality of Life after Treatment for Brain Metastases (QUARTZ) trial recently showed no difference in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or overall survival (OS) between best supportive care (BSC) alone and BSC plus WBRT in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with unfavorable prognostic factors [10]. WBRT for patients with extremely unfavorable prognoses may offer little clinical benefit, and BSC alone may be the more appropriate approach. Therefore, accurate identification of patients who are unlikely to receive any benefit from WBRT is necessary.

Useful tools for prognostic modeling of patients with BMs include the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) – Recursive Partitioning Analysis (RPA) and the Graded Prognostic Assessment (GPA) [11–13]. The RTOG-RPA identifies three prognostic classes of patients based on age, absence or presence of extracranial disease, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), and status of primary cancer: Class I (patients <65 years, KPS ≥70, controlled primary tumor, and no extracranial metastasis), Class III (KPS <70) and Class II (all patients not in Class I or III). The GPA is the sum of scores (0, 0.5 and 1.0) for four factors including age, KPS, presence of extracranial metastases and number of BMs. In the RTOG-RPA, MSTs for patients in Classes I, II and III were 7.7, 4.5 and 2.3 months, respectively. MSTs of patients with GPA 3.5–4.0, GPA 3, GPA 1.5–2.5 and GPA 0–1 were 11.0, 6.9, 3.8 and 2.6 months, respectively [13]. These tools can identify patients with unfavorable prognoses, but it is somewhat difficult to identify those with extremely unfavorable prognoses (survival time of <2 months). The purpose of this study was to identify a subgroup of patients with BMs that have extremely unfavorable prognoses and will not receive clinical benefits from WBRT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study retrospectively reviewed the records of 111 patients with BMs who were not eligible for surgical resection or STI and who underwent WBRT at our institution between March 2013 and April 2016. Patients with diagnoses such as primary brain tumors, leukemia, and malignant lymphoma were excluded. The presence of BMs was defined based on appropriate computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results. Information concerning patient characteristics, treatments and survival durations were collected using chart review.

All patients were treated with conventional external beam radiotherapy using a Clinac iX or Trilogy linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) with a photon energy of 10 MV and opposed lateral treatment fields that encompassed the entire brain. The prescribed dose was calculated at the isocenter of the radiation field. The treatment plan included a total dose of 30 Gy in ten fractions over 2 weeks for all patients except two; one was scheduled for a total dose of 37.5 Gy in 15 fractions and the other was scheduled for 20 Gy in five fractions. After treatment completion, patients were followed up every 1–2 months during the first year.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to determine the impact of the following parameters on overall survival (OS): age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) score, primary tumor histopathological subtype, status of primary tumor control, extracranial lesion control, number of BMs, presence of perilesional edema, presence of meningitis carcinomatosa, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, steroid use, chemotherapy before WBRT, and presence of hepatic metastases. The categorical scores of the RTOG-RPA and GPA were calculated. Because of the large proportion of patients with lung cancer in the patient population, the prognosis of lung cancer patients with BMs was compared by the status of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutation. The prognosis of lung cancer patients was also analyzed using the new prognostic models of diagnostic specific GPA (DS-GPA) and Lung-mol GPA [14, 15]. We used JMP 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to evaluate the association between OS and potential predictive factors. Univariate analyses consisted of Fisher’s exact tests, with the factors achieving statistical significance (defined as P < 0.05 throughout this study in two-sided tests) entered into the multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazards model). Actuarial survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were compared using the log-rank test. OS was defined as the length of time from the initiation of WBRT to death or to the last follow-up date. This study was approved by our institutional review board in December of 2016 (Approval No. 16–233).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients were followed until end of life, and all died from their systemic disease progression or BMs. The median follow-up was 3.6 months (range, 0.1–29.4 months). The median age was 70 years; 59% of patients were male and 41% were female. Lung cancer represented the most common primary cancer type (67%), followed by breast cancer (12%). Sixty patients had NSCLC and 14 patients had small cell lung cancer. Fifty-eight percent of the patients had poor PS (ECOG-PS 2–4). Only 4% of patients did not have extracranial lesions. There were more than three BMs in 59% of the patients, and 80% had perilesional edema. Eighty-eight patients received steroid therapy during WBRT. Sixty-three patients used steroids to relieve symptoms such as nausea, headache, and neurological deficits, and 18 patients used them to suppress progression of brain edema without symptoms. Forty-five patients had neurological symptoms such as hemiplegia and/or aphasia before WBRT. After WBRT, the symptoms were relieved in ten patients (22%), but without steroids the symptoms were relieved in only one patient. Fourteen percent of the patients had meningitis carcinomatosa. Eighty-nine percent of the patients received the planned total dose during WBRT, but 11% were not able to complete planned WBRT due to deterioration of their general condition.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 111).

| n (%) | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 (36–90) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 65 (59) | |

| Female | 46 (41) | |

| ECOG-PS | ||

| 0–1 | 49 (44) | |

| 2–4 | 62 (56) | |

| Primary tumor subtype | ||

| Lung | 74 (67) | |

| Breast | 13 (12) | |

| Melanoma | 5 (5) | |

| Other | 19 (16) | |

| Histopathology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 71 (64) | |

| Small cell carcinoma | 16 (14) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 13 (12) | |

| Melanoma | 5 (5) | |

| Other | 6 (5) | |

| Status of primary disease | ||

| Controlled | 24 (22) | |

| Uncontrolled | 87 (78) | |

| Extracranial metastases | ||

| Yes | 107 (96) | |

| No | 4 (4) | |

| Number of brain metastases | ||

| 1 | 12 (11) | |

| 2–3 | 33 (30) | |

| ≥4 | 66 (59) | |

| Using steroids during WBRT | ||

| Yes | 88 (79) | |

| No | 23 (21) | |

| Meningitis carcinomatosa | ||

| Present | 15 (14) | |

| Absent | 96 (86) | |

| Perilesional edema | ||

| Present | 89 (80) | |

| Absent | 22 (20) | |

| Maximal tumor size (mm) of brain metastases | 20 (0–74) | |

| ≤30 | 94 (85) | |

| >30 | 17 (15) | |

| Radiation dose (Gy) | 30 (3–37.5) | |

| <30 | 14 (13) | |

| 30 | 96 (86) | |

| 37.5 | 1 (1) | |

| Gene mutation in NSCLC (n = 60) | ||

| EGFR positive | 22 (37) | |

| ALK positive | 2 (3) | |

| Not tested | 11 (18) | |

| Molecular target therapy | ||

| Using before WBRT started | 17 (15) | |

| Using after WBRT finished | 20 (18) |

ALK = anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, NSCLC = non–small cell lung cancer, WBRT = whole brain radiotherapy.

The MST of all patients was 109 days (range, 4–883), and the OS rates at 6 and 12 months were 32% and 16%, respectively (Table 2). Fifty-five percent of patients were classified as RTOG-RPA Class III and 44% were Class II. The MSTs of RTOG-RPA Class III (n = 61) and Class II (n = 49) patients were 61 days and 173 days, respectively (P < 0.001). The OS rates at 6 and 12 months for Class III and Class II patients were 16% and 7%, and 47% and 27%, respectively. Seventy-seven percent of patients were classified as GPA 0–1 and 22% were classified as GPA 1.5–2.5. The MSTs of GPA 0–1 (n = 85) and GPA 1.5–2.5 (n = 24) patients were 61 days and 173 days, respectively (P < 0.001). The OS rates at 6 and 12 months for GPA 0–1 and GPA 1.5–2.5 patients were 26% and 12%, and 50% and 29%, respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis.

| MST | 6-month | 12-month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (days) | survival (%) | survival (%) | P-value | |

| Overall | 111 | 109 | 32 | 16 | |

| ECOG-PS | |||||

| 0–1 | 49 | 182 | 51 | 24 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 | 62 | 46 | 15 | 3 | |

| Perilesional edema | |||||

| Presence | 89 | 74 | 26 | 8 | 0.03 |

| Absence | 22 | 123 | 50 | 32 | |

| Serum LDH | |||||

| <1.5 × ULN | 81 | 134 | 41 | 17 | <0.001 |

| ≥1.5 × ULN | 30 | 36 | 3 | 0 | |

| Using steroids during WBRT | |||||

| Yes | 88 | 74 | 25 | 7 | 0.015 |

| No | 23 | 209 | 52 | 35 | |

| Hepatic metastases | |||||

| Present | 32 | 58 | 19 | 6 | 0.02 |

| Absent | 79 | 111 | 35 | 16 | |

| Primary site control | |||||

| Yes | 24 | 123 | 38 | 13 | 0.43 |

| No | 87 | 93 | 24 | 13 | |

| Maximum tumor size | |||||

| ≤3 cm | 94 | 104 | 32 | 14 | 0.39 |

| >3 cm | 17 | 44 | 24 | 6 | |

| Meningitis carcinomatosa | |||||

| Present | 15 | 192 | 53 | 20 | 0.14 |

| Absent | 96 | 74 | 27 | 11 | |

| Age | |||||

| <70 | 55 | 111 | 32 | 11 | 0.67 |

| ≥70 | 56 | 74 | 29 | 14 |

Univariate analyses were performed using Fisher’s exact tests. ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, MST = median survival time, ULN = upper limit of normal, WBRT = whole brain radiotherapy.

Univariate analysis revealed that five factors were significantly associated with poor prognosis (Table 2): ECOG-PS 2–4, presence of perilesional edema, elevated LDH, using steroids during WBRT, and presence of hepatic metastases. The threshold LDH level was set at >1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN, >300 IU/l) because the P-value was lowest at this level. Multivariate analysis confirmed elevated LDH as an independent predictor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis.

| Parameter | n | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH | ||||

| <1.5 × ULN | 81 | Ref. | ||

| ≥1.5 × ULN | 30 | 2.2 | 1.1–4.6 | 0.037 |

| ECOG-PS | ||||

| 0–1 | 49 | Ref. | ||

| 2–4 | 62 | 1.7 | 1.0–3.0 | 0.053 |

Multivariate analyses were performed using Cox’s proportional hazards model. CI = confidence interval, ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status, HR = hazard risk, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, ULN = upper limit of normal.

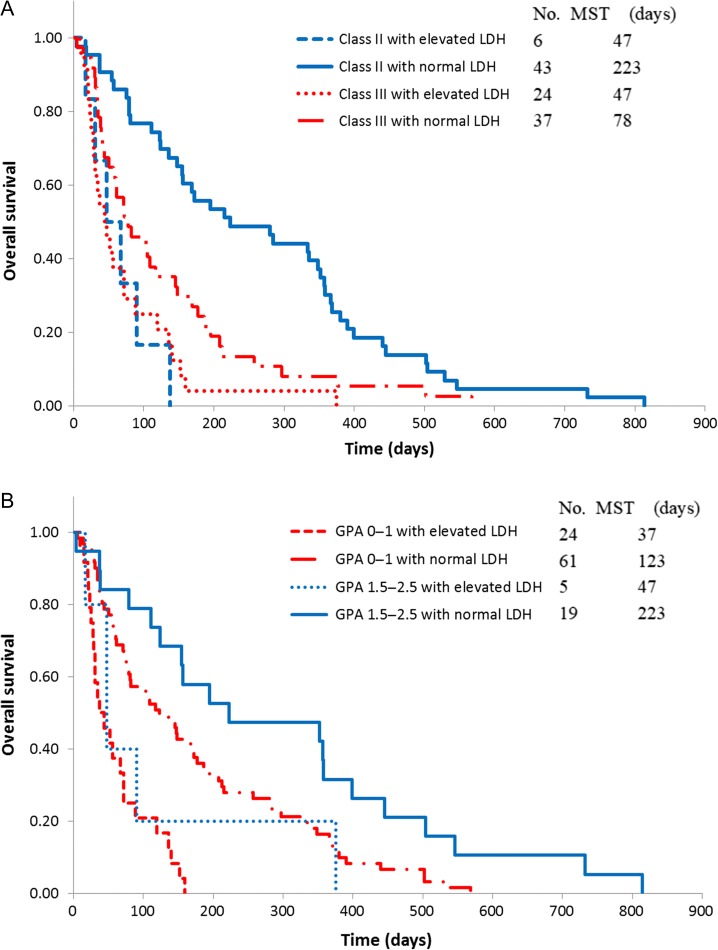

OS distributions of the patients in RTOG-RPA and GPA classes with or without elevated LDH are shown in Fig. 1. The MSTs for patients with and without elevated LDH were 36 days and 134 days, respectively (P < 0.001; Table 2). The MSTs of patients with and without elevated LDH were 47 days and 78 days, respectively (P < 0.001) for 61 RTOG-RPA Class III patients, and 47 days and 223 days, respectively (P < 0.001), for 49 RTOG-RPA Class II patients. Among 85 GPA 0–1 patients, MSTs with and without elevated LDH were 37 days and 123 days, respectively (P < 0.001); 24 patients with GPA 1.5–2.5 had MSTs with and without elevated LDH of 47 days and 223 days, respectively (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Overall survival curves by RTOG-RPA class and GPA score. (A) Overall survival curves by RTOG-RPA class. (B) Overall survival curves by GPA score. GPA = Graded Prognostic Assessment, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, MST = median survival time, RTOG-RPA = Radiation Therapy Oncology Group – Recursive Partitioning Analysis.

Among NSCLC patients, 22 showed positive for EGFR mutation and 2 showed positive for ALK mutation. All of them were treated with molecular target therapy such as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and ALK inhibitors (Table 1). Seventeen patients were treated with the molecular target therapy before WBRT and 20 were treated after WBRT. No patient received such treatment during WBRT. The MST of patients with EGFR or ALK mutation was 350 days (range, 50–814), and the OS rates at 6 and 12 months were 71% and 46%, respectively. In contrast, the MST of patients without EGFR or ALK mutation was 107 days (range, 4–529), and the OS rates at 6 and 12 months were 28% and 10%, respectively. For lung cancer patients, the MSTs of DS-GPA 0–1 and D-GPA 1.5–2 were 67 days and 355 days, respectively (P < 0.001). Among 54 DS-GPA 0–1 patients, the MSTs with and without elevated LDH were 45 days and 159 days, respectively (P < 0.001). Fifty-eight percent of patients with DS-GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH died within 2 months. Similarly for NSCLC, the MSTs of Lung-mol GPA 0–1 and Lung-mol GPA 1.5–2 were 80 days and 309 days, respectively (P < 0.001). Among 36 Lung-mol GPA 0–1 patients, the MSTs with and without elevated LDH were 34 days and 105 days, respectively (P < 0.001). Fifty-six percent of patients with Lung-mol GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH died within 2 months.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated that elevated serum LDH level in patients with RTOG-RPA Class III or GPA 0–1 status was associated with extremely unfavorable prognosis after WBRT for BMs. WBRT is a palliative treatment that can relieve symptoms such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and neurological deficits. Pease and colleagues conducted a systematic review of WBRT and reported that neurological status response rates varied between 7% and 90% [16]. The response rates for treating headaches and motor loss ranged from 56% to 96%, and from 46% to 77%, respectively. The median response duration varied from 1 to 8 months. The median time to improvement in neurologic function ranged from 1 to 3 weeks, with two-thirds of patients showing improved neurologic function at 4 weeks after WBRT [3, 17]. A neurocognitive analysis of the RTOG 91–04 study using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) showed that approximately one-third of patients treated with WBRT experience neurocognitive improvement [18]. On the other hand, some adverse events such as nausea, headache, fatigue, scalp irritation, hair loss and neurocognitive deficits can occur during or after WBRT. Up to 40% of patients will experience acute radiation-induced toxicities [16]. In a recent study, 34% of patients experienced hair loss and 42% experienced moderate or severe episodes of drowsiness at 4 weeks from initiation of WBRT [10]. A randomized trial comparing radiosurgery alone with radiosurgery plus WBRT demonstrated that patients receiving adjuvant WBRT experienced significant deterioration in neurocognitive function [19].

In the QUARTZ trial, there was no difference in OS and quality of life (QOL) scores between BSC alone and BSC plus WBRT for patients with NSCLC [10]. More than one-third of the patients in this trial had RPA Class III, and many patients had a poor prognosis, as the MST was ~2 months. In the subgroup analyses, younger patients, particularly those younger than 60 years and KPS ≥70, showed improved survival with WBRT. Although the results of the clinical trial did not deny the efficacy of WBRT for BMs, BSC alone may be an appropriate alternative in patients with a very limited life span because it would save time spent on travel and hospital stays for radiation therapy. In contrast, WBRT may be a valuable approach for relieving symptoms and improving cranial control in patients with favorable prognoses. Better OS has been achieved in NSCLC patients with one to four BMs who were treated with WBRT and STI compared with those treated with STI alone [20].

Some useful models are available to classify patients with BMs by prognosis. RTOG-RPA, which consists of only four factors (age, KPS, status of primary lesions, and extracranial metastases), is more convenient to use than other prognostic indices. A limitation of this index is that most patients with BMs are classified into RTOG-RPA Class II. GPA is a new index that has been developed, and it is the most quantitative and easiest to use. However, it is somewhat difficult to identify patients with an extremely unfavorable prognosis (survival time of <2 months) by the RTOG-RPA or GPA. In our study, deaths within 2 months from initiation of WBRT initiation were observed in 49% of RTOG-RPA Class III patients (n = 61) and in 63% of patients in RTOG-RPA Class III with elevated LDH (n = 24). Similarly, deaths within 2 months from initiation of WBRT initiation were observed in 39% of GPA 0–1 patients (n = 85), and in 63% of patients with GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH (n = 24).

Sperduto and colleagues reported on DS-GPA and Lung-mol GPA [14, 15]. DS-GPA is an up-to-date prognostic index for specific malignant neoplasms such as lung cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and gastrointestinal cancer. DS-GPA for lung cancer is the sum scores (0, 0.5 and 1.0) for four factors including age, KPS, presence of extracranial metastases, and number of BMs. Lung-mol GPA is a new index that includes EGFR and ALK mutation status for NSCLC patients with BMs. In the current study, DS-GPA and Lung-mol GPA were suggested to be effective tools for predicting the prognosis of lung cancer patients and NSCLC patients. Furthermore, patients with DS-GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH, and patients with Lung-mol GPA 0–1 and elevated LDH, had very poor prognosis. From the results of the current study, it is suggested that addition of the laboratory factor of elevated LDH to the existing prognostic models (RTOG-RPA, GPA, DS-GPA or Lung-mol GPA) will enable identification of the subgroup of patients with extremely unfavorable prognosis after WBRT.

LDH is released from cells into the bloodstream when cells are damaged or destroyed. Elevated LDH reflects progressive conditions, such as progressive disease in extracranial lesions, and serum LDH is a general marker for predicting overall tumor load and cell turnover in patients with malignant neoplasms [21]. Partl and colleagues reported that the median OS of patients with KPS <70 and elevated LDH was 29 days, suggesting that a combination of KPS and LDH could be used to identify metastatic melanoma patients with BMs that have a very short life expectancy [22]. Nieder and colleagues concluded that LDH was the most important prognostic factor in patients with BMs [23]. In a study of 311 cancer patients with metastatic disease and serum LDH >1000 IU/l, the MST was 1.7 months and half of the patients survived <2 months, indicating that serum LDH levels predicted a terminal stage in metastatic cancer patients [24]. In our study, only six patients (5%) had an LDH level of >1000 IU/l. Their MST was 36 days (range, 9–67), and five patients (83%) died within 2 months.

Our study has certain limitations. First, this study suffers from biases associated with being a single institutional retrospective study. The sample was too small to justify the effect of multiple clinical features on survival. The prognostic value of the LDH level should be evaluated in a larger, multicenter setting. Second, our study primarily intended to evaluate the OS after WBRT. This cohort may have included some patients who would have benefited from WBRT (in terms of improvement of neurologic function or symptom relief), even in those with extremely unfavorable prognoses. We do not deny the role of WBRT for patients with BMs who have unfavorable prognoses. Administration of WBRT for patients with a very limited life span should, however, be carefully considered. Further studies should be conducted to validate the results reported here.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by a grant-in-aid from the Department of Radiation Oncology, Saitama Medical University, International Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tsao MN, Lloyd N, Wong RK et al. Whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;4:CD003869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borgelt B, Gelber R, Kramer S et al. The palliation of brain metastases: final results of the first two studies by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1980;6:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zimm S, Wampler GL, Stablein D et al. Intracerebral metastases in solid-tumor patients: natural history and results of treatment. Cancer 1981;48:384–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egawa S, Tukiyama I, Akine Y et al. Radiotherapy of brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1986;12:1621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pladdet I, Boven E, Nauta J et al. Palliative care for brain metastases of solid tumour types. Neth J Med 1989;34:10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Komarnicky LT, Phillips TL, Martz K et al. A randomized phase III protocol for the evaluation of misonidazole combined with radiation in the treatment of patients with brain metastases (RTOG-7916). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:53–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nieder C, Niewald M, Schnabel K. The radiotherapy of brain metastases in bronchial carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol 1994;170:335–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan GF, Ball DL, Smith JG. Treatment of brain metastases from primary lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995;31:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mulvenna P, Nankivell M, Barton R et al. Dexamethasone and supportive care with or without whole brain radiotherapy in treating patients with non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases unsuitable for resection or stereotactic radiotherapy (QUARTZ): results from a phase 3, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2004–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997;37:745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gaspar LE, Scott C, Murray K et al. Validation of the RTOG recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) classification for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47:1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sperduto PW, Berkey B, Gaspar LE et al. A new prognostic index and comparison to three other indices for patients with brain metastases: an analysis of 1,960 patients in the RTOG database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;70:510–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sperduto PW, Kased N, Roberge D et al. Summary report on the graded prognostic assessment: an accurate and facile diagnosis-specific tool to estimate survival for patients with brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sperduto PW, Yang TJ, Beal K et al. Estimating survival in patients with lung cancer and brain metastases: an update of the graded prognostic assessment for lung cancer using molecular markers (lung-molGPA). JAMA Oncol 2017;3:827–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pease NJ, Edwards A, Moss LJ. Effectiveness of whole brain radiotherapy in the treatment of brain metastases: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2005;19:288–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borgelt B, Gelber R, Larson M et al. Ultra-rapid high dose irradiation schedules for the palliation of brain metastases: final results of the first two studies by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1981;7:1633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Regine WF, Scott C, Murray K et al. Neurocognitive outcome in brain metastases patients treated with accelerated-fractionation vs. accelerated-hyperfractionated radiotherapy: an analysis from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 91-04. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;51:711–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brown PD, Jaeckle K, Ballman KV et al. Effect of Radiosurgery Alone vs Radiosurgery With Whole Brain Radiation Therapy on Cognitive Function in Patients With 1 to 3 Brain Metastases: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316:401–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aoyama H, Tago M, Shirato H. Stereotactic Radiosurgery With or Without Whole-Brain Radiotherapy for Brain Metastases: Secondary Analysis of the JROSG 99-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walenta S, Mueller-Klieser WF. Lactate: mirror and motor of tumor malignancy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2004;14:267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Partl R, Fastner G, Kaiser J et al. KPS/LDH index: a simple tool for identifying patients with metastatic melanoma who are unlikely to benefit from palliative whole brain radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nieder C, Marienhagen K, Dalhaug A et al. Towards improved prognostic scores predicting survival in patients with brain metastases: a pilot study of serum lactate dehydrogenase levels. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:609323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu R, Cao J, Gao X et al. Overall survival of cancer patients with serum lactate dehydrogenase greater than 1000 IU/L. Tumour Biol 2016;37:14083–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]