Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke are unanticipated major healthcare events that require emergent and expensive care. Given the potential financial implications of AMI and stroke among uninsured patients, we sought to evaluate rates of catastrophic healthcare expenditures (CHEs), defined as expenses beyond financial means, in a period before implementation of insurance expansion and protections in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).1

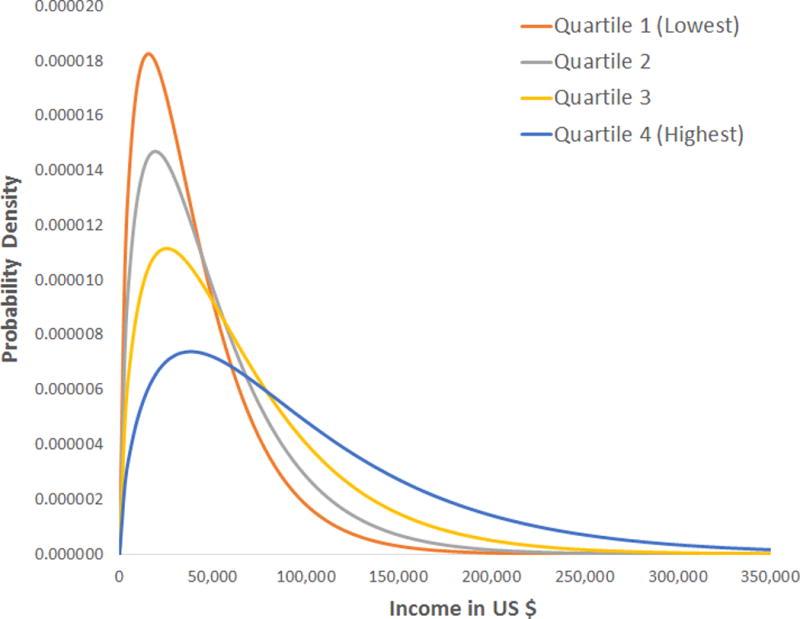

In a large nationally-representative database of inpatient hospitalizations, the National Inpatient Sample, we identified all AMI (Clinical Classification Software code 100 as primary diagnosis) and stroke (International Classification of Disease-Ninth Edition code – 430, 431, 432.x, 433.x1, 434.x1 or 436 as primary diagnosis) hospitalizations among uninsured nonelderly adults (ages:18–64 years) between 2008–2012. To estimate patient expenses relative to income, we obtained two data components from the NIS; hospitalization charges and an ordinal variable (values 1–4) representing quartiles of median income based on residential zip code. However, patient incomes can vary widely for each income quartile, and assessing CHEs requires an estimate of patient-level income. Therefore, using a previously suggested microsimulation model for assessing patient-level income from community income quartiles,2, 3 we estimated income for each patient from a 2-parameter gamma probability-distribution. We used the US Gini-coefficient (a measure of income inequality) of 0.411 to define the shape parameter, and the community-level income corresponding to each quartile to define the scale parameter for the income curve for each quartile (Figure 1A).4 As previously suggested, to prevent over-estimation of CHE due to under-estimation of income, mean quartile-income values centered at the highest value of the quartile range for quartiles 1–3 and at 80% of the upper bound for quartile 4.3

Figure 1.

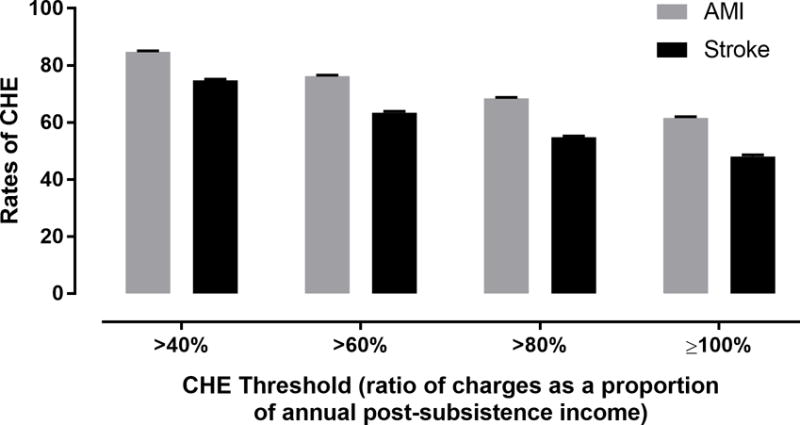

(A) Gamma distribution of income across the four income quartiles. (B) Rates of catastrophic health expenditures (CHE) with different cut-points for the defining CHE based on the ratio of hospitalizations charges to post-subsistence incomes.

Annual food expenditures were derived from US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates of food-related expenses as a function of income.5 Post-subsistence income was the difference between income and food-related subsistence-expenses. Based on previous literature,3 a hospitalization charge was classified as a CHE if charges exceeded 40% of the post-subsistence income. Bootstrapped mean and 95% confidence intervals were obtained by repeating the model over 10,000 simulations. All estimates were indexed to the year 2012 based on the Consumer Price Index. National estimates were obtained using survey-analysis tools in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

We identified 39,296 AMI (81% ≥45y, 26% women, 13% black, 38% in lowest income-quartile and 12% in highest quartile) and 29,182 stroke (82% ≥45y, 39% women, 26% black, 41% in lowest income-quartile and 11% in highest quartile) hospitalizations among uninsured nonelderly, corresponding to 188,192 and 139,687 nationally. The uninsured represented 15% of both AMI and stroke hospitalizations among nonelderly. Median hospitalization charges for AMI were $53,384 (IQR 33,282 –84,551) and for stroke were $31,218 (IQR 18,805 – 60,009). Among hospitalizations in the uninsured, the rates of CHE following AMI were 85% (95% CI 84 – 85%), and following stroke were 75% (95% CI 74 – 75%) (Figure 1B). In sensitivity analyses where CHE was redefined by hospitalization charges representing higher proportions of annual post-subsistence income (charge thresholds at 60%, 80% and ≥100% of annual post-subsistence income), a substantial proportion of uninsured nonelderly had CHEs during AMI and stroke hospitalizations (Figure 1B). Further, CHE rates for AMI and stroke were similar in four additional analyses where patient income was assumed to be (a) at the upper bound of respective quartiles, (b) restricted to quartile limits, (c) derived from income distribution for the general US population (US Census data), and (d) distributed in a different 2-parameter distribution (Weibull).

Our study’s strengths include evaluation of a nationally-representative sample of the uninsured, a frequently understudied patient population. Several limitations merit comment. First, patient income in NIS is not reported at an individual-level. Therefore, we estimated individual income based on prior work suggesting the gamma distributions as an appropriate approach to model income between pre-defined population-specific cut-offs for income.3 While imputed individual incomes from the microsimulation model are expected to be imprecise, summary estimates provide meaningful estimates of CHE risk among the uninsured. Moreover, results were robust to several sensitivity analyses. Next, we cannot account for income differences among uninsured who suffer AMI/stroke compared with others in the same income quartile. Finally, hospitalization costs may be overestimated as some charges may be reduced/waived. However, they are likely to encounter continued financial difficulties due to missed work, disability and outpatient healthcare needs, putting them at risk for financial catastrophe, including bankruptcy.

In summary, prior to the ACA, over 1 in 8 AMI and stroke hospitalizations among non-elderly adults occurred among those without insurance. In this vulnerable group of patients, in-hospital expenditures alone would be expected to cross the threshold to define a catastrophic expense in the large majority. Since many of these patients will have additional hospitalizations and health expenditures, they may easily exceed their annual income while being deprived of work during the illness. The potentially devastating financial impact of these events in the uninsured is considerable.

Acknowledgments

Data Sharing: The National Inpatient Sample data used in the study are owned by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Therefore, while the authors cannot make them available to the public for purposes of reproducing the results, these can be obtained from the AHRQ directly. The authors will be happy to share further details of the methodology on request.

Funding: Dr. Khera is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5T32HL125247-02) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001105) of the National Institutes of Health. The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Presentation Details:

QU.AOS.721 - Best of QCOR Oral Abstracts: Health Policy, Cost and Value

Session Date: November 13, 2017, Session Time: 5:45 PM PACIFIC TIME, Presenter: Rohan Khera

Session Time: 5:45 PM PACIFIC TIME

Presenter: Rohan Khera

Disclosures: Dr. Nasir is a consultant for Regeneron. Dr. Krumholz has research agreements with Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson through his institution; is a member of the scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth; and is founder of Hugo. None of the other authors have any relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.Eltorai AE, Eltorai MI. The Risk of Expanding the Uninsured Population by Repealing the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2017;317:1407–1408. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem AB, Mount T. A convenient descriptive model of income distribution: the gamma density. Econometrica: journal of the Econometric Society. 1974:1115–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott JW, Raykar NP, Rose JA, Tsai TC, Zogg CK, Haider AH, Salim A, Meara JG, Shrime MG. Cured into Destitution: Catastrophic Health Expenditure Risk Among Uninsured Trauma Patients in the United States. Annals of surgery. 2017 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Bank. Gini Index. 2016 (Accessed May 12, 2017, at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=US.

- 5.US Bureau of Labor and Statisitics: Consumer Expenditures. 2012 (Accessed May 12, 2017, at http://www.bls.gov/cex/csxann11.pdf)