Abstract

Objective

To determine the economic impact of medication non-adherence across multiple disease groups.

Design

Systematic review.

Evidence review

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and Scopus in September 2017. Studies quantifying the cost of medication non-adherence in relation to economic impact were included. Relevant information was extracted and quality assessed using the Drummond checklist.

Results

Seventy-nine individual studies assessing the cost of medication non-adherence across 14 disease groups were included. Wide-scoping cost variations were reported, with lower levels of adherence generally associated with higher total costs. The annual adjusted disease-specific economic cost of non-adherence per person ranged from $949 to $44 190 (in 2015 US$). Costs attributed to ‘all causes’ non-adherence ranged from $5271 to $52 341. Medication possession ratio was the metric most used to calculate patient adherence, with varying cut-off points defining non-adherence. The main indicators used to measure the cost of non-adherence were total cost or total healthcare cost (83% of studies), pharmacy costs (70%), inpatient costs (46%), outpatient costs (50%), emergency department visit costs (27%), medical costs (29%) and hospitalisation costs (18%). Drummond quality assessment yielded 10 studies of high quality with all studies performing partial economic evaluations to varying extents.

Conclusion

Medication non-adherence places a significant cost burden on healthcare systems. Current research assessing the economic impact of medication non-adherence is limited and of varying quality, failing to provide adaptable data to influence health policy. The correlation between increased non-adherence and higher disease prevalence should be used to inform policymakers to help circumvent avoidable costs to the healthcare system. Differences in methods make the comparison among studies challenging and an accurate estimation of true magnitude of the cost impossible. Standardisation of the metric measures used to estimate medication non-adherence and development of a streamlined approach to quantify costs is required.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42015027338.

Keywords: health economics, health policy, quality in health care, public health, adherence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a novel attempt to use existing studies to broaden the scope of knowledge associated with the economic impact of medication non-adherence via quantifying the cost of medication non-adherence across different disease groups.

A large comprehensive review—2768 citations identified, 79 studies included.

Inability to perform a meaningful meta-analysis—insufficient statistical data and considerable heterogeneity according to outcome/indicators.

Robust application of adapted Drummond checklist to evaluate the quality of economic evaluations.

Introduction

Nearly half of all adults and approximately 8% of children (aged 5–17 years) worldwide have a chronic condition.1 This, together with ageing populations, is increasing the demand on healthcare resources.2 Medications represent a cost-effective treatment modality,3 but with estimates of 50% non-adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses,4 intentional and unintentional medication non-adherence signifies a prevalent and persistent healthcare problem. Medication adherence is defined as ‘the extent to which the patients’ behaviour matches agreed recommendations from the prescriber’, emphasising the importance on the patients’ decisions and highlighting the modifiable aspect of non-adherence.5

Given the proportion of the population who do not adhere to their medication efforts to improve medication adherence represents an opportunity to enhance health outcomes and health system efficiency. Annual costings of medication non-adherence range from US$100 to U$290 billion6 in the USA, €1.25 billion7 in Europe and approximately $A7 billion8 9 in Australia. Additionally, 10% of hospitalisations in older adults are attributed to medication non-adherence10 11 with the typical non-adherent patient requiring three extra medical visits per year, leading to $2000 increased treatment costs per annum.12 In diabetes, the estimated costs savings associated with improving medication non-adherence range from $661 million to $1.16 billion.13 Non-adherence is thus a critical clinical and economic problem.4

Healthcare reformers and payers have repeatedly relied on cost-effectiveness analysis to help healthcare systems deal with the rising costs of care.14 However, there is still a budgetary problem that needs to be considered, especially given the widespread policy debate over how to best bend the healthcare cost curve downward15 and the proportion of healthcare budgets spent on prescription medication.16 Quantifying the cost of medication non-adherence will help demonstrate the causal effect between medication non-adherence, increased disease prevalence and healthcare resource use. Justification of the associated financial benefit may incentivise health policy discussion about the value of medication adherence and promote the adoption of medication adherence intervention programmes.15

The objective of this systematic review was, first, to determine the economic impact of medication non-adherence across multiple disease groups, and second, to review and critically appraise the literature to identify the main methodological issues that may explain the differences among reports in the cost calculation and classification of non-adherence.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews database (CRD42015027338) and can be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015027338. The systematic review was undertaken in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search was conducted in September 2017. Studies reporting the cost of medication non-adherence for any disease state were included. Searches were conducted in PubMed and Scopus. Neither publication date nor language restriction filters were used. The search used in PubMed was: (non-adherence[TIAB]) OR (‘Patient Compliance’[MH] AND (‘Drug Therapy’[MH]) OR medication[TIAB])) OR ‘Medication adherence’[MH] AND (costs[TIAB] OR ‘Costs and Cost Analysis’[MH] OR burden[TIAB]). This was adapted for other databases in online supplementary etable 1. Duplicate records were removed.

bmjopen-2017-016982supp001.pdf (170.8KB, pdf)

To identify relevant articles, an initial title and abstract screening was conducted by the lead reviewer (RLC) to identify studies appropriate to the study question. This process was overinclusive. In the second phase appraisal, potentially relevant full-text papers were read and excluded based on the following criteria: (i) papers not reporting the cost of medication non-adherence as a monetary value, (ii) systematic reviews, (iii) papers not reporting a baseline cost of medication non-adherence prior to the provision of an intervention and (iv) papers not reporting original data. Any uncertainty was discussed among two adherence experts (RLC and VGC) and resolved via consensus.

Extracted information

A data extraction form was developed based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews18 and piloted on a sample of included studies. The extracted information included the source (study identification, citation and title), eligibility (confirmation of inclusion criteria), objective, methods (study design, study groups, year data extracted, follow-up period, comparison, adherence measure, adherence data source and adherence definition), population (sample size, setting, country, disease state/drug studied, inclusion/exclusion criteria and perspective), impact/outcome indicators (indicators measured, indicator data source, indicator definitions and characteristics of the method of assessment), results (costs reported, standardised costs, type of costs, non-cost findings, subgroup analysis and statistical significance), conclusions and miscellaneous (funding source, references to other relevant studies, limitations and reviewers’ comments).

Costs were defined as any indicator associated with medication non-adherence that was quantified with a monetary value in the original study. This included direct costs (those costs borne by the healthcare system, community and patients’ families in addressing the illness), indirect costs (mainly productivity losses to society caused by the health problem or disease) and avoidable costs (those costs incurred for patients suffering complications, resulting from suboptimal medicines use, and patients with the same disease who experienced no complications). The indicators were grouped for analysis based on the original studies’ classification of the cost. All costs were converted to US$ (2015 values) using the Cochrane Economics Methods Group—Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating—Centre Cost Converter tool,19 allowing meaningful comparisons between non-adherence cost data. This online tool uses a two-stage computation process to adjust estimates of costs for currency and/or price year using a Gross Domestic Product deflator index and Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) for Gross Domestic Product.19 The PPP values given by the International Monetary Fund were chosen. If details of the original price year could not be ascertained from a study, the midpoint year of the study period was used for calculations. The mean cost was calculated and reported where studies separated out costs for different confounding factors within the one outcome measure in a disease state. Annual costs were extrapolated from the original study data if results were not presented in this manner.

The definition of medication non-adherence was derived from the included studies; with non-adherence referring to differing degrees of adherence based on the studies metric of estimation. Multiple non-adherence costs from individual studies may have been included where further subclassification of non-adherence levels was defined. The analysis assessed non-adherence costs within disease groups, with disease group and cost classification derived from the study. Total healthcare costs included direct costs to the healthcare system while total costs incorporated direct and indirect costs.

Quality criteria and economic evaluation classification

Economic evaluation requires a comparison of two or more alternative courses of action, while considering both the inputs and outputs associated with each.20 All studies were classified in accordance with Drummond’s distinguishing characteristics of healthcare evaluations as either partial evaluations (outcome description, cost description, cost–outcome description, efficacy or effectiveness evaluation, cost analysis) or full economic evaluations (cost– benefit analysis, cost–utility analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost minimisation analysis) by team consensus (RLC and VGC).

The Drummond checklist21 for economic evaluation was used to assess the quality of studies. The original checklist was modified to remove inapplicable items (4, 5, 12, 14, 15, 30 and 31) as no full economic evaluation met all inclusion criteria. A score of 1 was assigned if the study included the required item and 0 if it did not with a maximum potential score of 28. The study was classified as high quality if at least 75% of Drummond’s criteria were satisfied, medium quality if 51%–74% were satisfied and low quality if 50% of the criteria or less were satisfied.

Meta-analysis

Outcome/indicator costs were independently extracted using predesigned data extraction forms (total healthcare costs, total costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, pharmacy costs, medical costs, emergency department costs and hospitalisation costs) for the purpose of integrating the findings on the cost of medication non-adherence to pool data and increase the power of analysis.

Results

Study selection

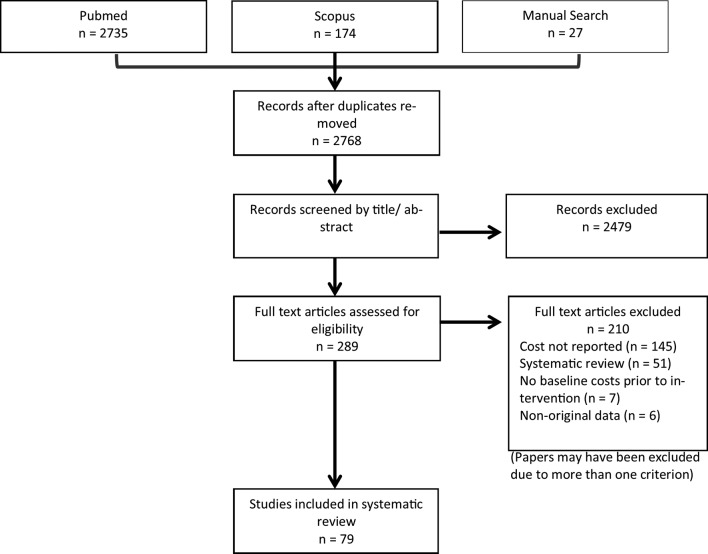

Search strategies retrieved 2768 potential articles after duplicates were removed. Two hundred and eighty nine articles were selected for full-text review. Seventy-nine studies were included in the review (figure 1). Numerous other papers do discuss non-adherence costs; however, they addressed tangential issues or did not present primary relevant data. Many studies failed to report the monetary value of medication non-adherence associated with a range of cost estimate indicators.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. The PRISMA diagram details the search and selection process applied during the overview. The search yielded a total of 2768 citations. Studies were selected based on the inclusion criteria; studies reporting the cost of medication non-adherence using original cost data. Intervention studies were required to report baseline data. Seventy-nine original studies met the inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of individual studies

Sixty-six studies (83%) were conducted in the USA,10 22–85 four in Europe,86–89 four in Asia,90–93 three in Canada,94–96 one in the UK97 and one across multiple countries throughout Europe and the UK.98 Publication years ranged from 1997 to 2017; in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews, no date restriction filters were used18 with earlier studies following the same pattern of association between medication non-adherence and increasing healthcare costs. Individual studies reported a large variety of costs, calculated by varying means. In total, 44 studies (56%) reported unadjusted costs,22 26 27 30 32–36 38–42 45 47–49 51–55 57 62–67 71 74 80–82 85 87–89 91–93 98 21 (26%) adjusted costs,10 23–25 29 31 43 50 56 58–60 70 72 75–77 83 84 86 90 11 a combination of adjusted and unadjusted,28 37 44 46 61 68 69 73 78 79 96 2 unadjusted and predicted94 95 and 1 predicted costs.97 The method of determining non-adherence ranged significantly between studies with majority of papers using pharmacy and/or healthcare claims data (97%).10 22–29 31–51 54 56 58–87 91–96 Some studies used a combination of surveys or questionnaires, observational assessment, previous study data and disease state-specific recommended guidelines. Medication possession ratio (MPR) was the most used method to calculate patient non-adherence with 51 studies (63%) reporting non-adherence based on this measure13 24 25 28 29 32–36 40–43 45 46 48–50 54 56 57 59–63 66–77 80 81 85–87 91–96; however, the cut-off points to define medication non-adherence differed with some studies classifying non-adherence as <80% medication possession and others through subclassification of percentage ranges (eg, 0%–20%, 20%–40%, 40%–60%, 60%–80%, 80%–100%). The proportion of days covered (PDC) was the next most common measure of non-adherence (11%),31 37 44 47 51 78 79 82–84 with all other studies using an array of measures including self-report,97 urine testing,55 observational assessment,98 time to discontinuation,58 cumulative possession ratio,23 disease-specific medication management guidelines,65 88 Morisky four-Item scale,52 medication gaps,38 prescription refill rates22 27 and medication supplies.10 The main characteristics of the included studies are summarised in online supplementary etable 2.

bmjopen-2017-016982supp002.pdf (952.8KB, pdf)

Quality assessment and classification of economic evaluations

The quality assessment of economic evaluations yielded 10 studies of high,13 33 37 49 50 56 70 74 86 92 59 of medium10 22–26 28–32 34–36 38–47 52–55 57 58 60–63 65 66 68 69 71 72 75–81 83–85 87 88 90 93–98 and 10 of low quality.27 48 59 64 67 73 82 89 91 Scores ranged from 26.1% to 87.5% (mean 62.63%). Only one study identified the form of economic evaluation used and justified it in relation to the questions that were being addressed.70 The item ‘the choice of discount rate is stated and justified’ was applicable only to studies covering a time period of >1 year; all studies that cover >1 year failed to identify or explain why costs had not been discounted. Details of the analysis and interpretation of results were lacking in the majority of studies resulting in medium-quality or low-quality scores.

Through use of Drummond’s distinguishing characteristics of healthcare evaluations criteria,20 it is apparent that no full economic evaluation was conducted in any of the included studies. All studies performed partial economic evaluations of varying extents. The classification of economic evaluations resulted in 59 cost description studies (74% of those included), 15 cost–outcome descriptions and 5 cost analysis studies (online supplementary etable 2).

Medication non-adherence and costs

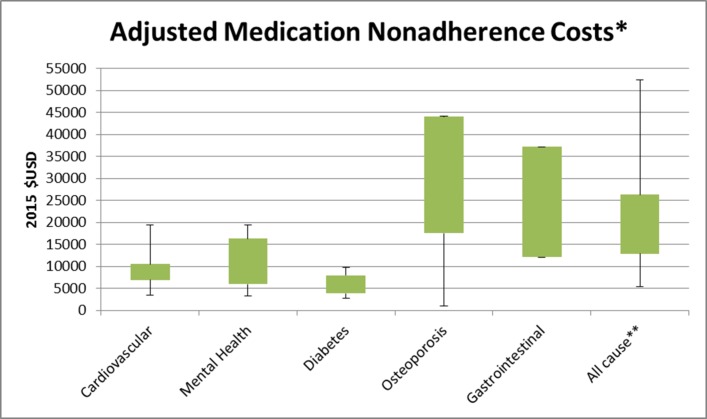

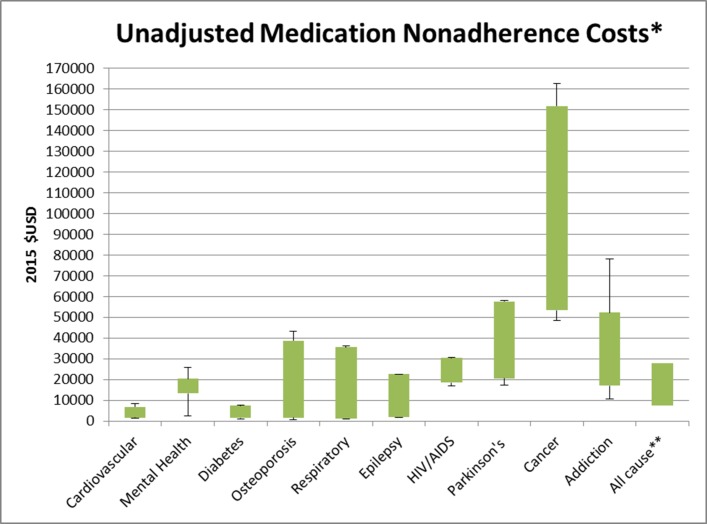

The cost analysis of studies (figures 2 and 3) reported annual medication non-adherence costs incurred by the patient per year. The adjusted total cost of non-adherence across all disease groups ranged from $949 to $52 341, while the unadjusted total cost ranged from $669 to $162 699. Figures 2 and 3 highlight the minimum, maximum and interquartile range (IQR) of annual costs incurred by patients across disease groups where three or more studies were included for review. All-cause costs encompass non-adherence costs incurred in mixed disease state studies, taking into account other confounding factors such as comorbidities.

Figure 2.

Annual adjusted medication non-adherence costs per patient per year. Encompasses the minimum, maximum and IQR of adjusted annual costs incurred by patients across disease groups where three or more studies were included for review. Gastrointestinal only included three studies limiting the range of costs. All-cause costs encompass non-adherence costs incurred in mixed disease state studies, taking into account other confounding factors such as comorbidities.

Figure 3.

Annual unadjusted medication non-adherence costs per patient per year. Encompasses the minimum, maximum and IQR of unadjusted annual costs incurred by patients across disease groups where three or more studies were included for review. Epilepsy and addiction only included three studies limiting the range of costs. All-cause costs encompass non-adherence costs incurred in mixed disease state studies, taking into account other confounding factors such as comorbidities.

Many different indicators were used to estimate medication non-adherence costs with no clear definition of what was incorporated in each cost component. The composition of included costs to estimate total cost or total healthcare cost varied significantly between studies, thus indicators were grouped for analysis based on the original studies’ classification of the cost. The main ones were total cost or total healthcare cost (83%), pharmacy costs (70%), outpatient costs (50%), inpatient costs (46%), medical costs (29%), emergency department costs (27%) and hospitalisation costs (18%) (online supplementary etable 2). Avoidable costs (eg, unnecessary hospitalisations, physician office visits and healthcare resource use) were not well defined with majority of studies failing to quantify these costs.

Lower levels of adherence across all measures (eg, MPR, PDC) were generally associated with higher total costs. From those that reported total or total healthcare costs, 39 studies (49%) reported non-adherence costs to be greater than adherence costs24 25 27 29 31 32 34 37–39 41 42 46 48 49 54 55 57 60–64 69–77 83 85 86 95–98 and 11 studies (15%) reported non-adherence costs to be less than adherence costs.23 26 36 43 58 62 65 80 91 93 94 Four reported fluctuating findings based on varying non-adherence cost subcategories,33 47 66 92 and two studies reported conflicting findings between adjusted and unadjusted costs.78 79 Higher all-cause total non-adherence costs and lower disease group-specific non-adherence costs were reported in four studies,40 67 84 90 whereas Hansen et al46 reported all-cause total non-adherence costs to be lower ($18 540 vs $52 302) but disease group-specific non-adherence total costs to be higher ($3879 vs $2954).

The association between non-adherence and cost was determined through use of a variety of scaling systems. The most used methods were MPR and PDC. These measures could then further be subcategorised based on the percentage of adherence/non-adherence. The 80%–100% category was classified as the most adherent group across both scales, with the most common definition of non-adherence being <80% MPR or PDC.

Cost of medication non-adherence via disease group

Cancer exhibited more than double the cost variation of all other disease groups ($114 101). Osteoporosis ($43 240 vs $42 734), diabetes mellitus ($7077 vs $6808) and mental health ($16 110 vs $23 408) cost variations were similar between adjusted and unadjusted costs while cardiovascular disease adjusted costs were more than double unadjusted costs ($16 124 vs $6943). Inpatient costs represented the greatest proportion of costs contributing to total costs and/or total healthcare costs for cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, mental health, epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease. HIV/AIDS, cancer and gastrointestinal disease groups’ highest proportion of costs were attributed to pharmacy costs while outpatient costs were greatest in musculoskeletal conditions. Direct costs had greater economic bearing than indirect costs across all disease groups. Cost comparisons across disease groups are summarised in online supplementary etable 3.

bmjopen-2017-016982supp003.pdf (201.3KB, pdf)

Cardiovascular disease

Twelve studies measured the economic impact of medication non-adherence in cardiovascular disease.10 24 31 60 61 64 66 75 80 92 94 95 Six studies reported adjusted costs10 24 31 60 61 75 with annual costs being extrapolated for two of these.31 60 Total healthcare costs and/or total costs were assessed in all of the studies with the major indicators measured including pharmacy costs,10 31 60 61 75 medical costs10 24 31 60 75 and outpatient costs.31 61 The annual economic cost of non-adherence ranged from $3347 to $19 472. Sokol et al10 evaluated the economic impact of medication non-adherence across three cardiovascular conditions: hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and chronic heart failure. For all three cardiovascular conditions examined, pharmacy costs were higher for the 80%–100% adherent group than for the less adherent groups. Total costs and medical costs were lower for the adherent groups of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia patients. However, for patients with chronic heart failure, total costs and medical costs were lower for the 1%–19% and 20%–39% adherent groups than for the 80%–100% adherent groups.

Unadjusted costs were measured in six studies with the annual total healthcare costs and/or total costs of non-adherence ranging from $1433 to $8377.64 66 80 92 94 95 Rizzo et al64 reported cost findings through subgroup analysis of five conditions. For all conditions, the total healthcare costs were higher for non-adherent groups compared with adherent. While Zhao et al80 categorised participants into adherence subgroups, finding that total healthcare costs were lower for the non-adherent population. The remaining studies used five key indicators to determine the economic impact: inpatient costs,66 92 outpatient costs,66 92 pharmacy costs,66 94 95 medical costs94 95 and hospitalisation costs.94 95

Mental health

The analyses used to report the economic impact of medication non-adherence in mental health varied widely. Also, 11 of 14 studies provided a total non-adherence cost estimate in mental health,23 25 27 51 58 65 72 81 90 97 98 with annual cost data being extrapolated for 4 of these.27 65 81 98 Six studies used adjusted costs, finding that the total annual cost of non-adherence per patient ranged from $3252 to $19 363.23 25 58 59 72 90 Bagalman et al25 focused primarily on the indirect costs associated with non-adherence—short-term disability, workers’ compensation and paid time off costs while Robertson et al81 highlighted the association between medication non-adherence and incarceration, with findings indicating incarceration and arrest costs are higher for worsening degrees of non-adherence. All other studies addressed direct costs. The main indicators used to measure the direct economic impact of medication non-adherence were pharmacy costs,23 39 51 58 59 65 72 98 inpatient costs,39 59 65 97 98 outpatient costs23 39 58 65 98 and hospitalisation costs.22 23 58 98

The total unadjusted cost for medication non-adherence ranged from $2512 to $25 920 as reported in four studies.51 65 81 98 Becker et al27 used a subgroup analysis to classify patients based on their adherence level. For every 25% decrement in the rate of adherence (75%–100%, 50%–74%, 25%–49%,<25%), non-adherence total costs increased. The negligible adherence group (<25%) incurred annual costs that were $3018 more than those of the maximal adherence group (75%–100%).

Knapp et al97 outlined the predicted cost of non-adherence with reference to relative impact and other factors associated with resource use and costs in patients with schizophrenia. Total costs ($116 434) were substantially higher than the other two indicators, which were inpatient costs ($13 577) and external services costs ($3241).

Diabetes mellitus

Eleven studies reported a cost measurement of the impact of medication non-adherence with reference to the health system and the individual.13 44 46 50 73 75 82 83 91 93 96 One study estimated that the total US cost attributable to non-adherence in diabetes was slightly >$5 billion.50 Five studies reported the adjusted total healthcare costs and/or total costs with annual costs per patient ranging from $2741 to $9819.46 50 73 75 83 96 One study reported total costs in relation to subgroup analysis based on MPR level,73 and another reported total healthcare costs through subgroup analysis of commercially insured and Medicare supplemental patients.75 Curtis et al83 used a diabetic population to report all-cause costs, with non-adherence costs being higher than adherence costs across all outcome indicators bar pharmacy costs.

A further four studies reported unadjusted cost findings13 82 91 93 with an additional four studies reporting unadjusted costs in combination with adjusted values.44 46 73 96 Unadjusted total healthcare costs and/or total costs ranged from $1142 to $7951. Extrapolated annual costs were determined for two studies based on cost data presented.13 93

The most prominent indicators used to determine costs were pharmacy costs,13 44 46 73 75 82 83 96 outpatient costs,13 46 75 83 93 96 inpatient costs46 75 96 and hospitalisation costs.50 91 93 All studies assessed the direct costs associated with medication non-adherence. One study evaluated the relationship between non-adherence and short-term disability costs in addition to assessing direct costs.44

Osteoporosis

The cost of medication non-adherence in relation to osteoporosis was predominantly examined through analysis of the direct costs associated with non-adherence using total healthcare costs and/or total costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, pharmacy costs and emergency department costs. Two studies further assessed the economic impact of non-adherence through evaluation of fracture-related costs.47 87 Also, 4 out of 11 studies reported the adjusted cost of medication non-adherence in addition to reporting unadjusted costs.28 78 79 86 Three studies further classified non-adherence through subgroup analysis, with Briesacher et al28 using MPR 20% interval increases and the two studies conducted by Zhao et al78 79 using PDC, with ≥80% classified as high adherence, 50%–79% medium adherence and <50% low adherence. In the studies conducted by Zhao et al,78 79 total healthcare costs were highest for the medium adherence group ($41 402 and $44 190) followed by the highest adherence group ($37 553 and $43 863), and lowest for the low adherence group ($34 019 and $43 771). These annual costs were extrapolated from study data. In contrast, Briesacher et al28 modelled the subgroup analyses against the lowest adherence group (<20% MPR), finding that costs decreased as adherence increased.

Overall, the unadjusted total healthcare costs and/or total costs of non-adherence ranged from $669 to $43 404. Studies that further classified patients based on subgroups had the wider cost ranges. In the three studies that reported the lowest level of non-adherence to be PDC <50%, the cost of this category ranged from $16 938 to $43 404.47 78 79

One study examined only the medical costs of non-adherence through MPR subgroup analysis in commercial and Medicare supplemental populations. The findings were that, for all levels of non-adherence, costs of non-adherence were higher for Medicare supplemental patients.45

Respiratory disease

The majority of studies reported unadjusted cost of medication non-adherence, with significant variation in the method of adherence classification.36 38 52 63 88 Two studies used MPR,36 63 one the Morisky four-item scale,52 one the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2007 guidelines88 and one a 37-day gap in claims data.38 Joshi et al52 reported on the indirect costs of medication non-adherence through consideration of losses in total productivity costs, absenteeism costs and presenteeism costs, while all remaining studies examined direct costs. Delea et al36 reported a direct relationship between decreases in medication non-adherence level and total costs, whereas Quittner et al63 reported an inverse relationship between decreases in medication non-adherence level and total healthcare cost. The total expenses associated with the lowest subgroup of adherence across all measures ranged from $804 to $36 259. In contrast, Davis et al84 used adjusted costs across four subclassifications of PDC adherence ranges to demonstrate that non-adherence costs were lower than adherence costs in all-costing outcomes reported except hospitalisation costs.

Gastrointestinal disease

Three of five studies reported the adjusted annual cost of medication non-adherence per patient using the MPR method.43 56 70 Of these, two reported the total cost ($12 085 and $37 151)43 70 with the main contributors to the overall total cost being inpatient costs (22% and 37%), outpatient costs (57% and 17%) and pharmacy costs (20% and 45%).

The remaining two studies used infusion rates to assess non-adherence with neither reporting the total cost nor total healthcare costs.30 53 Carter et al30 reported hospitalisation costs to be $42 854 while Kane et al53 reported a significantly lower cost at $5566 in addition to other direct cost contributors.

Epilepsy

Three studies reported the economic impact of medication non-adherence in epilepsy. All reported unadjusted costs using an MPR cut-off of <80%.35 41 42 The main economic indicators used to assess total costs were inpatient costs ($2289–6874), emergency department visit costs ($331–669) and pharmacy costs ($442–1067). Davis et al35 modelled the costs of the non-adherent group against the adherent group. The annual costs reported by Faught et al42 were extrapolated from original cost data. The total cost of non-adherence in epilepsy ranged from $1866 to $22 673.

HIV/AIDS

The economic impact of medication non-adherence for patients with HIV and AIDS reported among all three studies was similar.26 32 62 Two of the three studies examined the costs only for HIV,26 32 while Pruitt et al62 assessed the cost in AIDS as well as HIV. The total unadjusted costs for non-adherent HIV patients ranged from $16 957 to $30 068 with one study further categorising patients with HIV as having either a high viral load or low viral load.26 The total cost of non-adherence in AIDS was $30 523.62 All studies used comparable indicators (total cost, inpatient cost, outpatient cost, pharmacy cost) to determine the cost of non-adherence.

Parkinson’s disease

The direct costs associated with Parkinson’s disease were assessed in all three studies. The unadjusted total cost ranged from $10 988 to $52 023.34 37 71 Wei et al71 further subgrouped patients into MPR adherence percentage categories and found that costs increased in all economic indicators (inpatient costs and outpatient costs) as adherence decreased, except for pharmacy costs which decreased with non-adherence. One study additionally reported the adjusted cost, estimating that $10 290 could be attributed to medication non-adherence annually.37

Musculoskeletal conditions

Differing subgroup analyses was used to measure the impact of medication non-adherence on the annual cost incurred by patients. One study assessed both the direct and indirect costs of non-adherence,49 one assessed only the medical costs68 and one examined the direct costs in commercial and Medicare supplemental patient populations.77 Zhao et al77 reported the adjusted annual cost in the commercial population to be $22 609, and in the Medicare supplemental group, $28 126. Ivanova et al49 reported only unadjusted costs and the annual total cost of $3408. This figure was extrapolated from study data provided. The main indicators used to evaluate the economic impact of non-adherence were inpatient costs, outpatient costs, pharmacy costs and medical costs. Outpatient costs made the largest contribution to the overall total.

Cancer

Two studies evaluated the effects of medication non-adherence in cancer.33 74 One study reported total annual costs of $119 416,74 while the other gave a subgroup analysis based on classified adherence levels.33 In general, the lowest two adherence subgroups (<50% and 50%–90%) reported the highest total healthcare costs ($162 699 and $67 838). This trend followed for inpatient costs, outpatient costs and other costs, but the reverse relationship was found for pharmacy costs.

Addiction

The adjusted annual total healthcare cost of medication non-adherence was reported as $53 50455 while the unadjusted cost ranged from $16 996 to $52 213.55 69 85 Leider et al55 reported the main contributors to this cost to be outpatient costs ($10 829) and pharmacy costs ($8855), whereas Tkacz et al69 and Ruetsch et al85 reported them to be inpatient costs ($28 407 and $5808) and outpatient costs ($15 460 and $5743).

Metabolic conditions other than diabetes mellitus

One study measured the influence of medication non-adherence on direct healthcare costs in metabolic conditions, reporting an unadjusted attributable total cost of $138 525.54 The economic indicators used to derive this cost were inpatient costs ($16 192), outpatient costs ($111 100), emergency department visit costs ($801) and pharmacy costs ($3538).

Blood conditions

Candrilli et al29 reported cost findings on the relationship between non-adherence and healthcare costs, giving an adjusted total cost estimate of $13 458 for non-adherence classified as MPR <80%.

All causes

In addition to disease-specific studies of the economic impact of medication non-adherence, 28 studies reported the all-causes costs, encompassing cost drivers such as comorbidities. In seven of these studies, annual costs were extrapolated from the original data.46 49 60 63 65 84 98 Eleven studies reported on economic indicators without giving total cost or total healthcare cost,22 44 45 53 54 56 59 80 82 89 98 and one study reported on costs per episode of non-adherence.89

The adjusted cost of medication non-adherence was reported in 14 studies with an estimated range of $5271–52 341.10 29 31 56 58–60 70 75 76 83 84 86 90 Sokol et al10 reported the all-cause cost of non-adherence through subgroup analysis of disease states and MPR levels, while Pittman et al60 reported only using MPR-level breakdown.

Fifteen studies reported the unadjusted economic impact of medication non-adherence with an estimated range of $1037–53 793.22 40 45 49 53 54 57 63–65 67 80 82 89 98 A further four studies reported adjusted and unadjusted costs.37 44 46 96 The most frequent indicators used to measure the economic impact were total healthcare costs and/or total costs (71%), pharmacy costs (75%), inpatient costs (46%), outpatient costs (46%), medical costs (28%) and emergency department visit costs (25%).

Meta-analysis

Statistical analysis was attempted to collate the large collection of results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings on the cost of medication non-adherence. However, the criterion for a meta-analysis could not be met due to the heterogeneity in study design and lack of required statistical parameters in particular SD.99 Combining studies that differ substantially in design and other factors would have yielded meaningless summary results.

Discussion

This systemic review broadens the scope of knowledge associated with the economic impact of medication non-adherence across different disease groups while building on previous reviews where greater focus was on targeting overall risk factors or conceptual issues associated with medication non-adherence. Medication non-adherence was generally associated with higher healthcare costs. A large variety of outcomes were used to measure the economic impact including total cost or total healthcare cost, pharmacy costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, emergency department costs, medical costs and hospitalisation costs.

The costs reported reflect the annual economic impact to the health system per patient. None of the studies estimated broader economic implications such as avoidable costs arising from higher disease prevalence with studies failing to quantify avoidable costs separately to direct and indirect costs possibly due to coding restraints in healthcare claims databases. The majority of studies took the patient or healthcare provider perspective, estimating additional costs associated with non-adherence compared with adherence. Current literature identifies and quantifies key disease groups that contribute to the economic burden of non-adherence, but no research has attempted to synthesise costs across disease states within major healthcare systems. Comparisons across disease groups would benefit the development of health planning and policy yet prove problematic to interpret due to the varying scope of their inclusion (eg, mental health vs Parkinson’s disease). Similarly, there is substantial variation in the differential cost of adherence among disease groups with certain diseases requiring greater cost inputs (eg, cancer and supportive care costs). Further exploration of non-adherence behaviour and associated costs is required to adequately quantify the overall cost of non-adherence to healthcare systems as the available data are subject to considerable uncertainty. Given the complexity of medication non-adherence in terms of varying study designs, methods of estimation and adherence definitions, there is a limitation as to the ability to truly estimate costs attributed to non-adherence until further streamlined processes are defined.

Significant differences existed in the range of costs reported within and among disease groups. No consistent approach to the estimation of costs or levels of adherence has been established. Many different cost indicators were used, with few studies defining exactly what that cost category incorporated, so it is not surprising that cost estimates spanned wide ranges. Prioritisation of healthcare interventions to address medication non-adherence is required to address the varying economic impact across disease groups. Determining the range of costs associated with medication non-adherence facilitates the extrapolation of annual national cost estimates attributable to medication non-adherence, thus enabling greater planning in terms of health policy to help counteract increasing avoidable costs.

The economic, clinical and humanistic consequences of medication non-adherence will continue to grow as the burden of chronic diseases grows worldwide. Evolution of health systems must occur to adequately address the determinants of adherence through use of effective health interventions. Haynes et al100 highlights that ‘increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments’. Improving medication adherence provides an opportunity for major cost savings to healthcare systems. Predictions of population health outcomes through use of treatment efficacy data need to be used in conjunction with adherence rates to inform planning and project evaluation.4 The correlation between increased non-adherence and higher disease prevalence should be used to inform policymakers to help circumvent avoidable costs to the healthcare system.

The metric of adherence estimation varied substantially within and across disease groups; likely affecting the comparisons between studies. However, Hess et al,101 who compared six key adherence measures on the same study participants, found that the measures produced similar adherence values for all participants, although PDC and continuous measure of medication gaps produced slightly lower values. While this highlights the comparability of the measures of medication non-adherence, it further justifies the need to agree on consistent methods for estimating non-adherence through use of pharmacy claims data.

MPR was the most commonly used measure to estimate medication non-adherence. MPR was used in 63% of studies, followed by PDC, which was used in 11%. These percentages were consistent with those found recently by Sattler et al.102 Even though the measures of medication non-adherence may be comparable, the definition of MPR and the cut-off points to define non-adherence differed significantly. Dragomir et al94 defined MPR as the total days’ supply of medication dispensed in the period, divided by the follow-up period, with the assumption of 100% adherence during hospitalisation; Wu et al75 removed the number of hospitalised days from the calculation; and Pittman et al60 calculated the total number of days between the dates of the last filling of a prescription in the first six months in a given year and the first filling of a prescription in the 365 days before the last filling. Non-adherence could also be further classified into subcategories within MPR and PDC based on percentages. Thirty studies defined non-adherence as MPR <80%, and 12 studies categorised non-adherence into varying percentage subgroups. While Karve et al103 validated the empirical basis for selecting 80% as a reasonable cut-off point based on predicting subsequent hospitalisations in patients across a broad array of chronic diseases, 76 of the 79 studies included in this review examined more than just hospitalisation costs as an indicator metric. Further research is required to identify and standardise non-adherence thresholds using other outcomes such as laboratory, productivity and pharmacy measures.

Within the 79 studies covered, 35 different indicators were used to measure the cost of non-adherence and 19 reporting styles were identified. Because of the resultant heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was impossible. It is imperative that a standardised approach be established to measure and report the economic impact of medication non-adherence. The core outcome set must take into consideration the perspective of the intended audience and the proportion of non-adherence cost that is attributable to each outcome to determine an appropriate model.104 The critical indicators based on the findings of this review include total costs, pharmacy costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, emergency department visit costs, medical costs and hospitalisation costs for analysis based on direct costs. For indirect analysis, the core outcomes include short-term disability costs, workers’ compensation costs, paid time off costs, absenteeism costs and productivity costs. We suggest that further analysis of the contribution of each outcome to the overall cost of non-adherence be undertaken to help develop a tool that can be used for future research.

Many studies have examined the relationship between non-adherence and economic outcomes using a cross-sectional analysis.50 The implications of this are that potentially crucial confounders such as baseline status are ignored. In addition, a cross-sectional analysis may obscure temporality: for example, did greater adherence result in reduced costs and improved health outcomes, or was the patient healthier initially and more capable of being adherent? A longitudinal design is needed to overcome this limitation.

Economic evaluations inform decisions on how to best make use of scarce societal health resources through offering an organised consideration of the range of possible alternative courses of action and the evidence of the likely effects of each.20 While none of the studies taken separately could inform a choice between alternative courses of action, they did provide key evidence for decision makers about costs associated with medication non-adherence. Pharmacy claims data were used by the majority of studies to model cost estimates. Three-quarters of the studies were classified as cost descriptions, providing a cost or outcome overview of the health consequences associated with non-adherence. Ten studies garnered a high-quality classification, potentially limiting the overall conclusions that are able to be drawn and emphasised the need for future study design to incorporate elements allowing full economic evaluations to be conducted. Hughes et al105 highlighted the need for more information on the consequences of non-adherence, so that economic evaluations could reflect the potential long-term effect of this growing problem.

Of the 79 included studies, 66 of the studies were conducted in the USA. Conversion of costs to a common currency (US$) facilitated the comparison of studies and disease groups. Comparison of costs between healthcare systems is difficult as no two are the same and as healthcare is generally more expensive in the USA, cost estimates may not reflect average values. Thus caution needs to be taken when interpreting results; however, findings help to represent the significance of the economic burden medication non-adherence plays. Analysis of studies not conducted in the USA supports the finding that generally medication non-adherence incurs greater costs for all cost indicator outcomes other than pharmacy costs.

Due to the advances in technology available to record and assess medication non-adherence, the inclusion of studies undertaken in the late 1990s and early 2000s may have affected the comparability of results, despite the fact that these studies met the inclusion criteria.22 23 64 72 73 97 The quality of data presents a limitation. Information on disease groups with fewer included studies may be less reliable than information on those with more. However, our findings affirm the pattern of association between non-adherence and increasing healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Medication non-adherence places a significant cost burden on healthcare systems. However, differences in methodological strategies make the comparison among studies challenging and reduce the ability for the true economic magnitude of the problem to be expressed in a meaningful manner. Further research is required to develop a streamlined approach to classify patient adherence. An economic model that adequately depicts the current landscape of the non-adherence problem using key economic indicators could help to stratify costs and inform key policy and decision makers. Use of existing data could help to better define costs and provide valuable input into the development of an economic framework to standardise the economic impact of medication non-adherence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RC research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Footnotes

Contributors: RLC and VGC performed all the data extraction and quality assessment. RLC drafted the initial form and all revisions of this manuscript. All authors conceived the paper, made significant contributions to the manuscript and read and modified the drafts, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: RLC’s research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Patient consent: Not requried.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data from systematic review available in paper and supplementary material.

References

- 1. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview (accessed 24 Jun 2016).

- 2. World Health Organisation, National Institute of Aging, National Institute of Health and US Department of Health and Human Services. Global health and ageing. 2011. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf (accessed 24 Jun 2016).

- 3. Congressional Budget Office. Offsetting effects of prescription drug use on medicare’s spending for medical services. Congressional budget office report. 2012. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43741-MedicalOffsets-11-29-12.pdf (accessed 10 Aug 2017).

- 4. World Health Organisation. Adherence to long term therapies; evidence for action. 2003. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 6 Nov 2015).

- 5.Horne RWJ, Barber N, Elliot R, et al. . COncordance, adherence and compliance inmedicine taking. Report for the national coordinating centre for nhs service delivery and organization R & D (NCCSDO), 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6. New England Healthcare Institute. Thinking outside the pillbox: a system-wide approach to improving patient medication adherence for chronic disease. 2009. http://www.nehi.net/publications/44/thinking_outside_the_pillbox_a_systemwide_approach_to_improving_patient_medication_adherence_for_chronic_disease (accessed 24 Jun 2016).

- 7. Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. Targeting adherence. Improving patient outcomes in Europe through community pharmacists’ intervention. 2008. http://www.pgeu.eu/policy/5-adherence.html (accessed 28 Jan 2016).

- 8. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Advancing the responsible use of medicines; applying levers for change. 2012. http://pharmanalyses.fr/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Advancing-Responsible-Use-of-Meds-Report-01-10-12.pdf (accessed 10 Mar 2016).

- 9. AIHW. Health and welfare expenditure series no.57. Cat. no. HWE 67. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. . Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005;43:521–30. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermiere E, Avonts D, Van Royen P, et al. . Context and health outcomes. Lancet 2001;357:2059–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05153-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Pharmacists Association/APhA AP. Medication compliance-adherence-persistence (CAP) Digest. Washington DC: American Pharmacists Association and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egede LE, Gebregziabher M, Dismuke CE, et al. . Medication nonadherence in diabetes: longitudinal effects on costs and potential cost savings from improvement. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2533–9. 10.2337/dc12-0572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bach PB. New math on drug cost-effectiveness. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1797–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1512750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roebuck MC, Liberman JN, Gemmill-Toyama M, et al. . Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending. Health Aff 2011;30:91–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. OECD. Health at a Glance: OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemilt I, Thomas J, Morciano M. A web-based tool for adjusting costs to a specific target currency and price year. Evid Policy 2010;6:51–9. 10.1332/174426410X482999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. . Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford university press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ 1996;313:275–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:805–11. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. . Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:692–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aubert RE, Yao J, Xia F, et al. . Is there a relationship between early statin compliance and a reduction in healthcare utilization? Am J Manag Care 2010;16:459–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagalman E, Yu-Isenberg KS, Durden E, et al. . Indirect costs associated with nonadherence to treatment for bipolar disorder. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:478–85. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181db811d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnett PG, Chow A, Joyce VR, et al. . Determinants of the cost of health services used by veterans with HIV. Med Care 2011;49:848–56. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b34c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker MA, Young MS, Ochshorn E, et al. . The relationship of antipsychotic medication class and adherence with treatment outcomes and costs for Florida Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34:307–14. 10.1007/s10488-006-0108-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Yood RA, et al. . Consequences of poor compliance with bisphosphonates. Bone 2007;41:882–7. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candrilli SD, O’Brien SH, Ware RE, et al. . Hydroxyurea adherence and associated outcomes among Medicaid enrollees with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2011;86:273–7. 10.1002/ajh.21968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter CT, Waters HC, Smith DB. Impact of infliximab adherence on Crohn’s disease-related healthcare utilization and inpatient costs. Adv Ther 2011;28:671–83. 10.1007/s12325-011-0048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casciano JP, Dotiwala ZJ, Martin BC, et al. . The costs of warfarin underuse and nonadherence in patients with atrial fibrillation: a commercial insurer perspective. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:302–16. 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.4.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooke CE, Lee HY, Xing S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in managed care members in the United States: a retrospective claims analysis. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20:86–92. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.1.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darkow T, Henk HJ, Thomas SK, et al. . Treatment interruptions and non-adherence with imatinib and associated healthcare costs: a retrospective analysis among managed care patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:481–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis KL, Edin HM, Allen JK. Prevalence and cost of medication nonadherence in Parkinson’s disease: evidence from administrative claims data. Mov Disord 2010;25:474–80. 10.1002/mds.22999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis KL, Candrilli SD, Edin HM. Prevalence and cost of nonadherence with antiepileptic drugs in an adult managed care population. Epilepsia 2008;49:446–54. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delea TE, Stanford RH, Hagiwara M, et al. . Association between adherence with fixed dose combination fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on asthma outcomes and costs*. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:3435–42. 10.1185/03007990802557344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delea TE, Thomas SK, Hagiwara M. The association between adherence to levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone therapy and healthcare utilization and costs among patients with Parkinson’s disease: a retrospective claims-based analysis. CNS Drugs 2011;25:53–66. 10.2165/11538970-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diehl JL, Daw JR, Coley KC, et al. . Medical utilization associated with palivizumab compliance in a commercial and managed medicaid health plan. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16:23–31. 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eaddy M, Grogg A, Locklear J. Assessment of compliance with antipsychotic treatment and resource utilization in a Medicaid population. Clin Ther 2005;27:263–72. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenberg DF, Placzek H, Gu T, et al. . Cost and consequences of noncompliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:56–65. 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ettinger AB, Manjunath R, Candrilli SD, et al. . Prevalence and cost of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs in elderly patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009;14:324–9. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faught RE, Weiner JR, Guérin A, et al. . Impact of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs on health care utilization and costs: findings from the RANSOM study. Epilepsia 2009;50:501–9. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosselin A, Luo R, Lohoues H, et al. . The impact of proton pump inhibitor compliance on health-care resource utilization and costs in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Value Health 2009;12:34–9. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagen SE, Wright DW, Finch R, et al. . Impact of compliance to oral hypoglycemic agents on short-term disability costs in an employer population. Popul Health Manag 2014;17:35–41. 10.1089/pop.2013.0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halpern R, Becker L, Iqbal SU, et al. . The association of adherence to osteoporosis therapies with fracture, all-cause medical costs, and all-cause hospitalizations: a retrospective claims analysis of female health plan enrollees with osteoporosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2011;17:25–39. 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen RA, Farley JF, Droege M, et al. . A retrospective cohort study of economic outcomes and adherence to monotherapy with metformin, pioglitazone, or a sulfonylurea among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States from 2003 to 2005. Clin Ther 2010;32:1308–19. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hazel-Fernandez L, Louder AM, Foster SA, et al. . Association of teriparatide adherence and persistence with clinical and economic outcomes in Medicare Part D recipients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:4 10.1186/1471-2474-14-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ. Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 2006;38:922–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ivanova JI, Bergman RE, Birnbaum HG, et al. . Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. J Med Econ 2012;15:601–9. 10.3111/13696998.2012.667027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jha AK, Aubert RE, Yao J, et al. . Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Aff 2012;31:1836–46. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang Y, Ni W. Estimating the impact of adherence to and persistence with atypical antipsychotic therapy on health care costs and risk of hospitalization. Pharmacotherapy 2015;35:813–22. 10.1002/phar.1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Ambegaonkar A, et al. . Association of medication adherence with workplace productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with asthma. J Asthma 2006;43:521–6. 10.1080/02770900600857010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kane SV, Chao J, Mulani PM. Adherence to infliximab maintenance therapy and health care utilization and costs by Crohn’s disease patients. Adv Ther 2009;26:936–46. 10.1007/s12325-009-0069-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee A, Song X, Khan I, et al. . Association of cinacalcet adherence and costs in patients on dialysis. J Med Econ 2011;14:798–804. 10.3111/13696998.2011.627404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leider HL, Dhaliwal J, Davis EJ, et al. . Healthcare costs and nonadherence among chronic opioid users. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitra D, Hodgkins P, Yen L, et al. . Association between oral 5-ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2012;12:132 10.1186/1471-230X-12-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Modi A, Siris ES, Tang J, et al. . Cost and consequences of noncompliance with osteoporosis treatment among women initiating therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:757–65. 10.1185/03007995.2015.1016605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Offord S, Lin J, Mirski D, et al. . Impact of early nonadherence to oral antipsychotics on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with schizophrenia. Adv Ther 2013;30:286–97. 10.1007/s12325-013-0016-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, et al. . Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenia patients with Medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J 2013;49:625–9. 10.1007/s10597-013-9638-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pittman DG, Chen W, Bowlin SJ, et al. . Adherence to statins, subsequent healthcare costs, and cardiovascular hospitalizations. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1662–6. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pittman DG, Tao Z, Chen W, et al. . Antihypertensive medication adherence and subsequent healthcare utilization and costs. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:568–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pruitt Z, Robst J, Langland-Orban B, et al. . Healthcare costs associated with antiretroviral adherence among medicaid patients. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2015;13:69–80. 10.1007/s40258-014-0138-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quittner AL, Zhang J, Marynchenko M, et al. . Pulmonary medication adherence and health-care use in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2014;146:142–51. 10.1378/chest.13-1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: implications for health care costs. Clin Ther 1997;19:1446–57. 10.1016/S0149-2918(97)80018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson RL, Long SR, Chang S, et al. . Higher costs and therapeutic factors associated with adherence to NCQA HEDIS antidepressant medication management measures: analysis of administrative claims. J Manag Care Pharm 2006;12:43–54. 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stroupe KT, Teal EY, Tu W, et al. . Association of refill adherence and health care use among adults with hypertension in an urban health care system. Pharmacotherapy 2006;26:779–89. 10.1592/phco.26.6.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sunyecz JA, Mucha L, Baser O, et al. . Impact of compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy on health care costs and utilization. Osteoporos Int 2008;19:1421–9. 10.1007/s00198-008-0586-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, et al. . Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2011;28:51–61. 10.1007/s12325-010-0093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tkacz J, Volpicelli J, Un H, et al. . Relationship between buprenorphine adherence and health service utilization and costs among opioid dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014;46:456–62. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wan GJ, Kozma CM, Slaton TL, et al. . Inflammatory bowel disease: healthcare costs for patients who are adherent or non-adherent with infliximab therapy. J Med Econ 2014;17:384–93. 10.3111/13696998.2014.909436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wei YJ, Palumbo FB, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. . Antiparkinson drug adherence and its association with health care utilization and economic outcomes in a Medicare Part D population. Value Health 2014;17:196–204. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.White TJ, Vanderplas A, Ory C, et al. . Economic impact of patient adherence with antidepressant therapy within a managed care organization. Disease Management & Health Outcomes 2003;11:817–22. 10.2165/00115677-200311120-00006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White TJ, Vanderplas A, Chang E, et al. . The Costs of non-adherence to oral antihyperglycemic medication in individuals with diabetes mellitus and concomitant diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in a managed care environment. Disease Management & Health Outcomes 2004;12:181–8. 10.2165/00115677-200412030-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu EQ, Johnson S, Beaulieu N, et al. . Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with non-adherence to imatinib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:61–9. 10.1185/03007990903396469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu J, Seiber E, Lacombe VA, et al. . Medical utilization and costs associated with statin adherence in Medicaid enrollees with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45:342–9. 10.1345/aph.1P539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu N, Chen S, Boulanger L, et al. . Duloxetine compliance and its association with healthcare costs among patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. J Med Econ 2009;12:192–202. 10.3111/13696990903240559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao Y, Chen SY, Wu N, et al. . Medication adherence and healthcare costs among fibromyalgia patients treated with duloxetine. Pain Pract 2011;11:381–91. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao Y, Johnston SS, Smith DM, et al. . Association between teriparatide adherence and healthcare utilization and costs among hip fracture patients in the United States. Bone 2014;60:221–6. 10.1016/j.bone.2013.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao Y, Johnston SS, Smith DM, et al. . Association between teriparatide adherence and healthcare utilization and costs in real-world US kyphoplasty/vertebroplasty patients. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2525–33. 10.1007/s00198-013-2324-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao Y, Zabriski S, Bertram C. Associations between statin adherence level, health care costs, and utilization. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:703–13. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Robertson AG, Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, et al. . Treatment participation and medication adherence: effects on criminal justice costs of persons with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2014;65:1189–91. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Buysman EK, Anderson A, Bacchus S, et al. . Retrospective study on the impact of adherence in achieving glycemic goals in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients receiving canagliflozin. Adv Ther 2017;34:937–53. 10.1007/s12325-017-0500-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Curtis SE, Boye KS, Lage MJ, et al. . Medication adherence and improved outcomes among patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2017;23:e208–e14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Davis JR, Wu B, Kern DM, et al. . Impact of Nonadherence to inhaled corticosteroid/LABA therapy on COPD exacerbation rates and healthcare costs in a commercially insured US population. Am Health Drug Benefits 2017;10:92–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ruetsch C, Tkacz J, Nadipelli VR, et al. . Heterogeneity of nonadherent buprenorphine patients: subgroup characteristics and outcomes. Am J Manag Care 2017;23:e172–e79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kjellberg J, Jorgensen AD, Vestergaard P, et al. . Cost and health care resource use associated with noncompliance with oral bisphosphonate therapy: an analysis using Danish health registries. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:3535–41. 10.1007/s00198-016-3683-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2639–47. 10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miravitlles M, Sicras A, Crespo C, et al. . Costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in relation to compliance with guidelines: a study in the primary care setting. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2013;7:139–50. 10.1177/1753465813484080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alvarez Payero M, Martínez López de Castro N, Ucha Samartín M, et al. . Medication non-adherence as a cause of hospital admissions. Farm Hosp 2014;38:328–33. 10.7399/fh.2014.38.4.7660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Joe S, Lee JS. Association between non-compliance with psychiatric treatment and non-psychiatric service utilization and costs in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:444 10.1186/s12888-016-1156-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hong JS, Kang HC. Relationship between oral antihyperglycemic medication adherence and hospitalization, mortality, and healthcare costs in adult ambulatory care patients with type 2 diabetes in South Korea. Med Care 2011;49:378–84. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820292d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dilokthornsakul P, Chaiyakunapruk N, Nimpitakpong P, et al. . The effects of medication supply on hospitalizations and health-care costs in patients with chronic heart failure. Value Health 2012;15:S9–S14. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.An SY, Kim HJ, Chun KH, et al. . Clinical and economic outcomes in medication-adherent and -nonadherent patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Republic of Korea. Clin Ther 2014;36:245–54. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dragomir A, Côté R, White M, et al. . Relationship between adherence level to statins, clinical issues and health-care costs in real-life clinical setting. Value Health 2010;13:87–94. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dragomir A, Côté R, Roy L, et al. . Impact of adherence to antihypertensive agents on clinical outcomes and hospitalization costs. Med Care 2010;48:418–25. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d567bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gentil L, Vasiliadis HM, Préville M, et al. . Adherence to oral antihyperglycemic agents among older adults with mental disorders and its effect on health care costs, Quebec, Canada, 2005-2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E230 10.5888/pcd12.150412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Knapp M, King D, Pugner K, et al. . Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication regimens: associations with resource use and costs. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184:509–16. 10.1192/bjp.184.6.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, et al. . Clinical and economic consequences of medication non-adherence in the treatment of patients with a manic/mixed episode of bipolar disorder: results from the European Mania in bipolar longitudinal evaluation of medication (EMBLEM) study. Psychiatry Res 2011;190:110–4. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Deeks JJ HJ, Altman DG, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, et al. . Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;2:CD000011 10.1002/14651858.CD000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, et al. . Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1280–8. 10.1345/aph.1H018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sattler EL, Lee JS, Perri M. Medication (re)fill adherence measures derived from pharmacy claims data in older Americans: a review of the literature. Drugs Aging 2013;30:383–99. 10.1007/s40266-013-0074-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, et al. . An empirical basis for standardizing adherence measures derived from administrative claims data among diabetic patients. Med Care 2008;46:1125–33. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gargon E, Williamson PR, Altman DG, et al. . The COMET initiative database: progress and activities from 2011 to 2013. Trials 2014;15:279 10.1186/1745-6215-15-279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hughes DA, Bagust A, Haycox A, et al. . Accounting for noncompliance in pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:1185–97. 10.2165/00019053-200119120-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016982supp001.pdf (170.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016982supp002.pdf (952.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016982supp003.pdf (201.3KB, pdf)