Abstract

Objective

History and physical examination do not reliably exclude serious bacterial infections (SBIs) in infants. We examined potential markers of SBI in young febrile infants.

Design

We reviewed white cell count (WBC), absolute neutrophil count (ANC), neutrophil to lymphocyte count ratio (NLR) and C reactive protein (CRP) in infants aged 1 week to 90 days, admitted for fever to one medical centre during 2012–2014.

Results

SBI was detected in 111 (10.6%) of 1039 infants. Median values of all investigated diagnostic markers were significantly higher in infants with than without SBI: WBC (14.4 vs 11.4 K/µL, P<0.001), ANC (5.8 vs 3.7 K/µL, P<0.001), CRP (19 vs 5 mg/L, P <0.001) and NLR (1.2 vs 0.7, P<0.001). Areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for discriminating SBI were: 0.65 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.71), 0.69 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.74), 0.71 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.76) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.71) for WBC, ANC, CRP and NLR, respectively. Logistic regression showed the best discriminative ability for the combination of CRP and ANC, with AUC: 0.73 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.78). For invasive bacterial infection, AUCs were 0.70 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.85), 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.92), 0.78 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.89) and 0.78 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.90), respectively. CRP combined with NLR or ANC were the best discriminators of infection, AUCs: 0.82 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.95), respectively.

Conclusions

Among young febrile infants, CRP was the best single discriminatory marker of SBI, and ANC was the best for invasive bacterial infection. ANC and NLR can contribute to evaluating this population.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This large cohort is one of only a few descriptions of bacterial epidemiology of serious bacterial infection (SBI) evaluation in young febrile infants seen in the emergency department in the last 10 years.

We determined cut-off values for a number of infection markers for the evaluation of SBI in the 1 week to 3 months age group.

This is the first study to examine the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a diagnostic marker for bacterial infections in young infants.

Absolute neutrophil count and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio are inexpensive, readily available markers that can be used in settings in which C reactive protein is not available.

This is a retrospective study. Not all the older infants in the study underwent a complete workup. Some fairly rare neonatal bacterial infections, such as bacterial pneumonia, gastroenteritis and arthritis, were not ruled out. Only a relatively low number of invasive bacterial infections occurred in the study group.

Introduction

Fever (body temperature >38.0°C) is a common complaint in infants aged up to 3 months.1 2 Several protocols have been developed to help clinicians differentiate infants with low risk for serious bacterial infection (SBI), who can be managed as outpatients, from those requiring treatment and hospitalisation.3–5 These protocols use primarily laboratory values such as: leucocytosis (white cell count (WBC) >15 000/µL) or leucopaenia (WBC <5000/µL), the presence of leukocyturia or urinary nitrites, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) WBC to create a stratification of low-risk and high-risk febrile infants. The use of C reactive protein (CRP) as a marker for SBI is in common clinical use.6 7 Nonetheless, the prediction value of these laboratory tests remains controversial.

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a measure of systemic inflammation.8

In adults, NLR was found to predict bacteraemia in the emergency department (ED),9 indicate short and long-term mortalities among critically ill patients and guide prognosis in various acute infections, ischaemic heart disease, metabolic diseases, cancer and other medical conditions.10 11 In children, NLR was found to differentiate between viral and bacterial pneumonia,12 to be a useful diagnostic marker of acute appendicitis13 and to predict an attack of familial Mediterranean fever in children already diagnosed with this condition.14

The aim of this study was to assess, in hospitalised febrile infants aged 1 week to 3 months, the discriminatory ability of various, commonly available, markers of SBI, including NLR, which has not been previously studied in this age group and to determine cut-off values that could aid clinicians in the evaluation of febrile infants.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study comprised previously healthy, full-term infants (≥37 weeks at birth), 1 week to 90 days of age, who were admitted to the ED or paediatric department of Assaf Harofeh, a tertiary medical centre in Israel, during 2012–2014. Febrile infants (body temperature >38°C) from whom at least a blood count, CRP test and blood culture were taken were included in the analysis. Blood was drawn from all febrile infants who were admitted to the ED. In all neonates (<28 days old), urine and CSF cultures were also taken. In infants aged >28 days who were to receive antibiotics, urine cultures were also taken. In this age group CSF cultures were taken on clinical consideration. SBI was defined as the growth of a known pathogen in culture. Invasive bacterial infection (IBI) was determined as the presence of bacteraemia or meningitis. Infants with underlying haematological, immunological, respiratory or other medical conditions that might involve corticosteroid or antibiotic use in the previous 72 hours were excluded from the analysis. For analysis, we divided the cohort into two age groups: neonatal (<28 days old) and older infants (29–90 days old).

Laboratory data

The following data were collected from the medical records: complete history and physical examination, laboratory evaluation including blood counts, CRP testing, blood cultures, urine cultures and lumbar puncture. Samples were drawn by venepuncture. Blood tests were taken on admission; when the first sample was technically unsatisfactory and tests were repeated, results of blood counts or CRP were considered only if taken within 24 hours of taking cultures. Blood cell count was performed using the Beckman coulter LH750 design (USA). If a blood smear was performed, bands were added to the total number of neutrophils. CRP serum level was measured by the immunoturbidimetric assay using the Roche Cobas c701 (Japan). Blood was drawn for cultures as recommended in a BACTEC-PED. Blood culture results were examined and identified using the microbiology database. Urine cultures were obtained by transurethral bladder catheterisation or suprapubic aspiration.

From the blood count, ANC was retrieved and NLR was calculated as the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes. An age-adjusted NLR ratio was also created, by dividing NLR by a mean NLR based on the medical literature,15 according to age groups (1–2 weeks, 2 weeks to 1 month, ≥1 month). A urinary tract infection (UTI) was defined as the isolation of >50 000 colony-forming units per millilitre of urine of a single pathogen, not deemed as a contamination by a paediatric infectious specialist. Urinary analysis was not considered in this study. Cultures with more than one isolate were considered to be contaminated. Blood cultures were considered contaminated by pathogens and by the clinical course of the patient, following review of a paediatric infectious specialist. Patients were either discharged home from the ED or hospitalised at the paediatric department. The study was approved by the local institutional ethics review board.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.23.0, Armonk, NY: IBM). All tests were two-sided, and values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics are presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables, and as means and SD, or medians and IQR. Continuous variables were evaluated for normal distribution using histogram. Categorical variables were compared by χ2 test or Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared by t test or Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. Univariate logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of age, sex and blood tests with SBI. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the probability of having SBI. The multivariate logistic regression included the infection markers studied, and the probability calculated was the basis for the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The discriminative ability of each studied predictor was observed using the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detection16 and Classification and Regression Trees17 were used to identify threshold values of blood tests for SBI. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, positive predicted values and negative predicted values were reported.

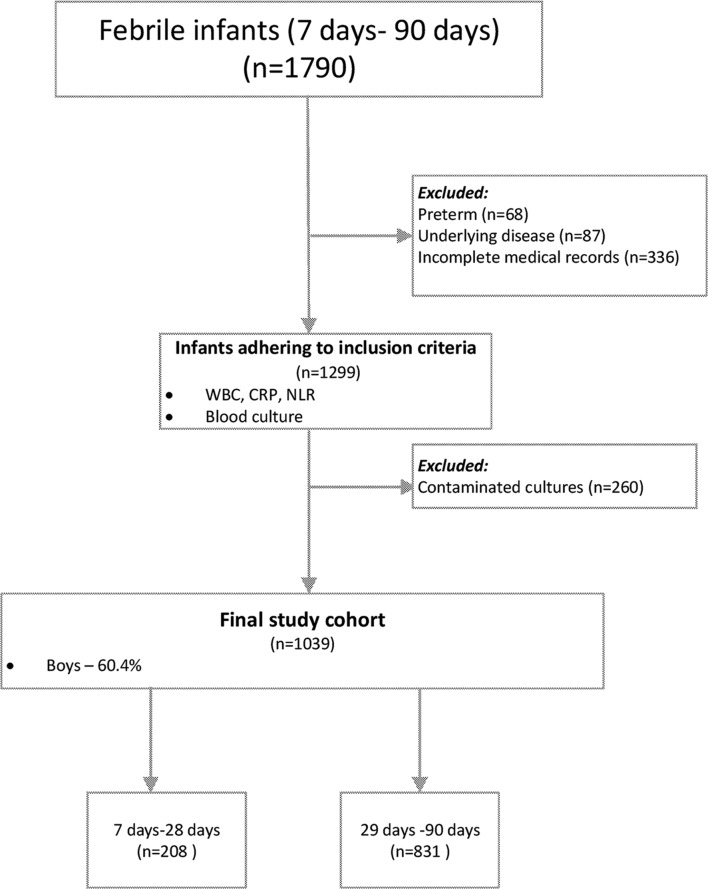

Results

During the study period, 1790 febrile infants aged 7–90 days were admitted to the ED or paediatric department. Of them, 68 preterm infants, 87 with underlying disease and 336 with incomplete medical records were excluded from the analysis. Incomplete medical records were mainly due to the absence of one of the following: a blood count within 24 hours of blood cultures, a CRP value, a blood culture or any bacterial culture in the neonatal age group. Of 1299 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 260 were excluded since their cultures were considered contaminated, as detailed below (figure 1). There were no statistically significant differences in the mean values of any of the markers studied, between those with contaminated cultures and those without an SBI (P>0.05). Females and younger infants were more likely to have contaminated cultures (P<0.01). Since no statistically significant differences were found between the contaminated and the non-SBI groups, we decided to exclude the contaminated cultures so as to avoid misclassification bias.

Figure 1.

Study population. CRP, C reactive protein; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; WBC, white cell count.

The final study cohort comprised 1039 infants; of them, 208 (20%) were neonates (ages 7–28 days old). In addition to blood cultures, urine culture results were available for 827 infants and CSF cultures for 587.

SBI was detected in 111 (10.6%) infants. Infants with SBI tended to be younger (median 34 (IQR 18–56) vs 46 (IQR 32–60) days, P<0.001). Boys comprised 60.4% of the febrile infants but only 54% of the infants with SBI. UTI was detected in 104 (10%) infants, bacteraemia in 11 (1.1%) and meningitis in 2 (0.2%). Four of the patients with UTI had concurrent bacteraemia and two had concurrent meningitis. UTI was the most common SBI (94%). Escherichia coli was the most common pathogen, detected in 74 (71.1%) of the UTIs, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae in 13 (12.5%) and Enterococcus faecalis in 8 (7.6%).

Median values of all the diagnostic markers investigated were significantly higher in patients with than without SBI: WBC (14.4 vs 11.4 K/µL, P<0.001), ANC (5.8 vs 3.7 K/µL, P<0.001), CRP (19 vs 5 mg/L, P<0.001) and NLR (1.2 vs 0.7, P<0.001) (table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in the assessment of SBI between the unadjusted NLR and the adjusted for age NLR.

Table 1.

Median values (IQR) for investigated diagnostic markers by age groups

| Age group | Status | Age | NLR | WBC | CRP | ANC |

| 7–28 days | Non-SBI | 20 (15–25) | 0.90 (0.52–1.8) | 11.35 (8.82–14.28) | 3.93 (1.25–9.43) | 4.3 (2.82–6.48) |

| SBI | 15 (12–19) | 2.15 (0.95–2.98) | 15.4 (10.7–21.23) | 31.2 (6.94–66.11) | 7.45 (5.03–12.08) | |

| P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | ||

| 29–90 days | Non-SBI | 51 (40–63) | 0.71 (0.4–1.25) | 11.4 (8.6–14.78) | 5.24 (1.49–12.33) | 3.6 (2.3–5.8) |

| SBI | 54 (41–61) | 0.87 (0.55–1.52) | 14 (10.1–17.9) | 15.74 (3.78–33.7) | 5.1 (3.6–5.1) | |

| P=0.81 | P=0.008 | P=0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | ||

| All age group | Non-SBI | 46 (32–60) | 0.74 (0.42–1.33) | 11.4 (8.6–11.4) | 4.95 (1.48–12.1) | 3.7 (2.4–5.98) |

| SBI | 34 (18–56) | 1.23 (0.68–2.5) | 14.4 (10.1–18.1) | 19.03 (5.18–50.5) | 5.8 (4.3–9.2) | |

| P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; SBI, serious bacterial infections; WBC, white cell count.

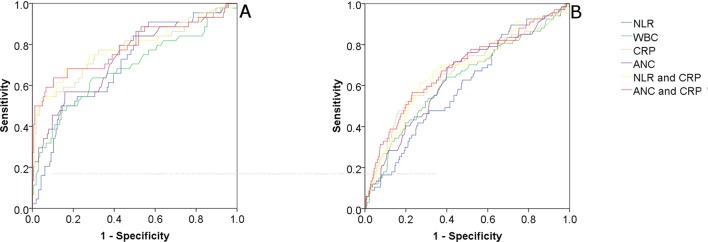

Tables 2 and 3 show sensitivities, specificities and ratio values of WBC, CRP and NLR for cut-off values that were arbitrarily chosen either due to their common use in clinical practice or to their ease of use (eg, in the case of NLR), for the discrimination of SBI. AUCs for the discrimination of SBI were 0.65 (95% CI 0.6 to 0.71), 0.69 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.74), 0.71 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.76) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.6 to 0.71) for WBC, ANC, CRP and NLR, respectively. CRP combined with ANC or NLR showed the best discriminatory values for a SBI: AUC of 0.73 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.78) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.78), respectively (table 4 and figure 2).

Table 2.

The sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratio values of NLR, CRP and WBC for discrimination of SBI in infants aged 7–28 days (95% CI)

| Parameter and threshold value | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR− | PPV | NPV | |

| NLR | >0.85 | 86.4% (74.1 to 94.4) | 47% (39.5 to 54.6) | 1.6 (1.4 to 2) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 30.3% | 92.8% |

| >1 | 72.7% (58.2 to 83.7) | 55.5% (57.8 to 62.9) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) | 30.4% | 88.3% | |

| >1.5 | 56.8% (42.2 to 70.3) | 67.7% (60.2 to 73.4) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.9) | 32% | 85.4% | |

| >2 | 52.3% (37.9 to 66.2) | 78% (71.1 to 83.7) | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.6) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | 38.9% | 85.9% | |

| >3 | 22.7% (12.8 to 37) | 90.9% (85.5 to 94.4) | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.1) | 0.9 (0.72 to 1) | 40% | 81.4% | |

| CRP (mg/L) | >5 | 79.5% (65.5 to 88.9) | 56.7% (49.1 to 64.1) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.3) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.7) | 32.9% | 91.1% |

| >20 | 54.4% (40.1 to 68.3) | 89% (83.3 to 92.9) | 5 (3 to 8.3) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | 56.9% | 87.9% | |

| >40 | 45.5% (31.7 to 59.9) | 97% (93.1 to 98.7) | 14.9 (5.9 to 37.5) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | 80.2% | 86.9% | |

| >80 | 15.9% (7.9 to 29.3) | 99.4% (96.6 to 99.9) | 26 (3.3 to 206.5) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1) | 87.6% | 81.5% | |

| ANC (103/μL) | >5 | 75% (60.6 to 85.4) | 58.5% (50.9 to 65.8) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.7) | 32.6% | 89.7% |

| >7 | 56.8% (42.2 to 70.3) | 84.1% (7.8 to 89) | 3.6 (2.3 to 5.6) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | 48.9% | 87.9% | |

| >10 | 34.1% (21.9 to 48.9) | 93.9% (89.1 to 96.7) | 5.6 (2.7 to 11.6) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | 59.9% | 84.2% | |

| >15 | 13.6% (6.4 to 26.7) | 100% (97.7 to 100) | n/a | 0.9 (0.8 to 1) | 100% | 81.2% | |

| WBC (103/μL) | >10 | 79.5% (65.5 to 88.9) | 39% (31.9 to 46.7) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 0.5 (0.3 to 1) | 25.8% | 87.7% |

| >15 | 50% (35.8 to 64.2) | 78% (71.1 to 83.7) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.4) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.9) | 37.8% | 85.4% | |

| >20 | 27.3% (16.4 to 41.9) | 85.7% (79.8 to 90.5) | 1.9 (1.1 to 3.6) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1) | 33.8% | 81.5% | |

| >25 | 9.1% (3.6 to 21.2) | 99.4% (96.6 to 99.9) | 14.9 (1.7 to 130) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1) | 80.2% | 80.3% | |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; LR, likelihood ratio; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; NPV, negative predictive value, PPV, positive predictive value; SBI, serious bacterial infection; WBC, white cell count.

Table 3.

The sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratio values of NLR, CRP and WBC for discrimination of SBI in infants aged 29–90 days (95% CI)

| Parameter and threshold value | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR− | PPV | NPV | |

| NLR | >0.85 | 52.2% (40.5 to 63.8) | 58.1% (54.6 to 61.6) | 1.3 (1 to 1.6) | 0.82 (0.6 to 1.1) | 9.9% | 93.2% |

| >1 | 47.8% (36.3 to 59.5) | 65.3% (61.9 to 68.6) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1) | 10.8% | 93.4% | |

| >1.5 | 25.4% (16.5 to 36.9) | 82.7% (79.9 to 85.2) | 1.5 (1 to 2.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1) | 11.5% | 92.6% | |

| >2 | 16.4% (9.4 to 27.1) | 89.8% (87.4 to 91.7) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 12.4% | 92.4% | |

| >3 | 9% (4.17 to 18.2) | 96.6% (95.1 to 97.7) | 2.6 (1.1 to 6.2) | 0.94 (0.9 to 1) | 18.9% | 92.3% | |

| CRP (mg/L) | >5 | 74.6% (63.1 to 83.5) | 49% (45.4 to 52.5) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) | 11.4% | 95.6% |

| >20 | 44.8% (33.5 to 56.6) | 84.7% (82 to 97.1) | 2.9 (2.1 to 4) | 0.7 (0.5 to 08) | 20.5% | 94.6% | |

| >40 | 20.9% (12.9 to 32.1) | 93.2% (91.2 to 94.8) | 3.1 (1.8 to 5.2) | 0.85 (0.8 to 1) | 21.3% | 93% | |

| >80 | 7.5% (3.2 to 16.3) | 98% (96.8 to 98.8) | 3.8 (1.4 to 10.1) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1) | 25% | 92.3% | |

| ANC (103/µL) | >5 | 52.2% (40.5 to 63.8) | 68.3% (64.9 to 71.5) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 12.7% | 94.2% |

| >7 | 31.3% (21.5 to 43.2) | 82.6% (79.7 to 85.1) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.7) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1) | 13.7% | 93.2% | |

| >10 | 13.4% (7.2 to 23.6) | 94.4% (92.5 to 95.8) | 2.4 (1.2 to 4.7) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1) | 17.4% | 92.5% | |

| >15 | 6% (2.4 to 14.3) | 99.1% (98.1 to 99.6) | 6.5 (2 to 21.7) | 1 (0.9 to 1) | 5.5% | 91.9% | |

| WBC (103/µL) |

>10 | 76.1% (64.7 to 84.7) | 37.6% (34.2 to 41.1) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 6 (0.4 to 1) | 9.7% | 94.7% |

| >15 | 43.4% (32.1 to 55.2) | 76.3% (73.2 to 79.2) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.5) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | 13.9% | 93.9% | |

| >20 | 13.4% (7.2 to 23.6) | 93.5% (91.5 to 95) | 2.1 (1.1 to 4) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1) | 15.4% | 92.5% | |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; LR, likelihood ratio; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SBI, serious bacterial infection; WBC, white cell count.

Table 4.

Area under the curve for SBI and IBI for diagnostic markers, by age group (95% CI)

| Age | NLR | WBC | CRP | ANC | ANC and CRP | NLR & CRP | |

| SBI | 7–28 days | 0.7 (0.62 to 0.79) | 0.68 (0.59 to 0.78) | 0.78 (0.69 to 0.87) | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.82) | 0.79 (0.7 to 0.88) | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.88) |

| 29–90 days | 0.6 (0.53 to 0.67) | 0.63 (0.55 to 0.7) | 0.67 (0.59 to 0.74) | 0.64 (0.57 to 0.71) | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.76) | 0.67 (0.to 0.71) | |

| All age group | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.71) | 0.65 (0.59 to 0.71) | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.76) | 0.69 (0.63 to 0.74) | 0.73 (0.67 to 0.78) | 0.72 (0.66 to 0.78) | |

| IBI | All age group | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.9) | 0.7 (0.56 to 0.85) | 0.78 (0.68 to 0.89) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.95) | 0.82 (0.7 to 0.95) |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; IBI, invasive bacterial infection; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SBI, serious bacterial infection; WBC, white cell count.

Figure 2.

(A and B) ROC curve of NLR, CRP, WBC, ANC and the combinations of CRP and NLR, and CRP and ANC for discrimination of serious bacterial infection. (A) Left: age <28 days. (B) Right: age 29–90 days. ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; NLR, neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; WBC, white cell count.

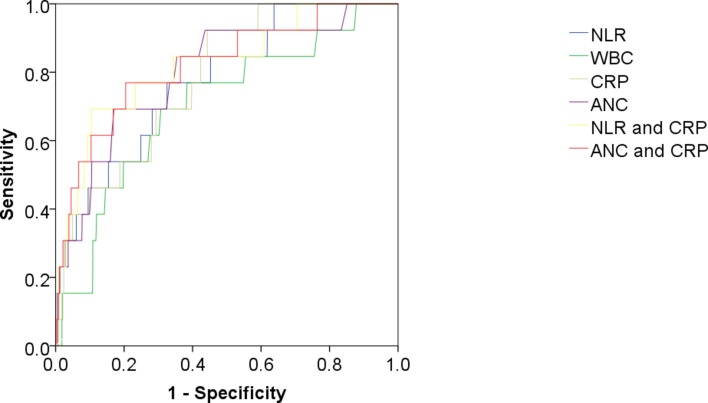

In an analysis of infants with an IBI such as bacteraemia or meningitis, the ANC, CRP and NLR performed similarly as discriminatory factors, with AUC of 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.92), 0.78 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.89) and 0.78 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.90), respectively, compared with AUC 0.70 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.85) for WBC. The combinations of CRP with NLR and with ANC were the best discriminators of bacterial infection: AUCs of 0.82 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.95), respectively (table 4, figure 3).

Figure 3.

ROC of NLR, WBC, CRP, ANC and the combinations of CRP and NLR, and CRP and ANC for discrimination of IBI. ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CRP, C reactive protein; IBI, invasive bacterial infection; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SBI, serious bacterial infection; WBC, white cell count.

All neonatal infants (aged <28 days) had undergone a full sepsis workup (CSF, blood and urine cultures were obtained); 44 infants (21.1%) had at least one positive culture. All mean investigated diagnostic markers were significantly higher in patients with than without SBI (table 1). The sensitivity and specificity of NLR, CRP and WBC for discriminating SBI tended to be greater for the younger than the older age group (tables 2 and 3).

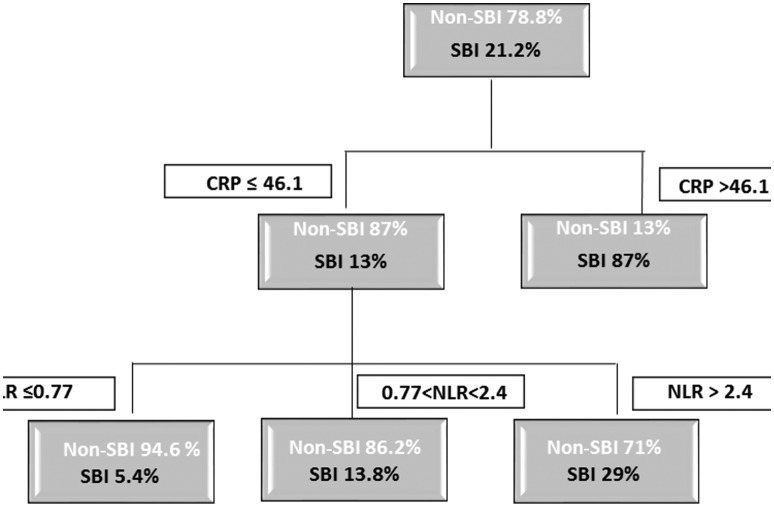

CRP combined with either ANC or NRL increased the discrimination of a SBI, compared with CRP alone (AUC 0.78–0.79) in the neonatal age group. The combination of optimal cut-off values for CRP and NLR in identifying a SBI is depicted in a decision tree (figure 4). For the neonatal age group, the overall SBI rate was 21.2%. For infants with CRP >46.1 mg/L (11% of the neonates), the risk for a SBI was 87%, compared with 13% for those with CRP <46.1 mg/L. Using a cut-off point of NLR <2.4, we found that infants with CRP <46.1 mg/L and NLR <2.4 have a risk of 9.7% for a SBI, compared with a 29% risk for those with NLR >2.4. The risk is further reduced to 5.4% for infants with NLR <0.77.

Figure 4.

Optimal cut-off values for CRP and NLR in discrimination of SBI in the neonatal age group. CRP, C reactive protein; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; SBI, serious bacterial infection.

Discussion

Our data reveal that NLR, ANC and CRP performed better in discriminating SBI in the neonatal age group than among older infants. CRP was found to be the single best indicator for discriminating a non-invasive SBI in both the neonates and older infants. In the absence of CRP, the markers ANC and NLR have similar sensitivity for identifying serious bacterial disease, especially in neonates. Both were similar as indicators for discriminating an IBI in infants younger than 3 months of age. The composite of ANC with CRP, or NLR with CRP, outperforms any of the single-studied markers for SBI or IBI.

In the USA, the incidence rate of all SBIs in infants younger than 90 days was estimated at 3.75/1000 full-term infants.18 Bacterial infection still represents an important cause of morbidity and mortality among young infants.19 Our results concur with other large studies that reported SBI to be ultimately diagnosed in about 10% of febrile infants in this age group.20 Differentiating between bacterial and viral infections in young infants is of utmost importance. Failure to identify bacterial pathogens may lead to delayed initiation of therapy and severe illness on one hand; or to prolonged and unnecessary therapy and the emergence of resistant microorganisms on the other hand. Several clinical and laboratory parameters are generally considered together to diagnose SBIs in this age group, although the optimal combination has not been determined.5

The early hyperdynamic phase of infection is characterised by a proinflammatory state and mediated by neutrophils, macrophages and monocytes, with the release of inflammatory cytokines. The onset of acute neutrophilia is associated with the generation of endotoxin, tumour necrosis factor, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8 and haematopoietic growth factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Maximal response usually occurs within 4–24 hours of exposure to these agents and probably results from the release of neutrophils from the marrow into circulation.21 The systemic inflammatory response is also associated with suppression of neutrophil apoptosis and increase in lymphocyte apoptosis.22

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess NLR as a diagnostic marker of bacterial infection in febrile young infants. In this large cohort of young febrile infants, we found that those with a SBI had statistically significant higher mean values of WBC, ANC, NLR and CRP. Of these markers, CRP was the best discriminatory parameter for a SBI. These findings concur with the results of another prospective Israeli study that found CRP to be a valuable laboratory test in the assessment of febrile infants aged <3 months old.6 However, in other studies, plasma CRP level was found to inadequately predict SBI in neonates. In a study conducted in Taiwan, CRP level was not elevated at the onset of clinical sepsis in approximately one-fourth of the cases of SBI in neonates.23 The low sensitivity of CRP may be due to its delayed elevation; an estimated 6–12 hours is needed for a significant increase.24 This is especially relevant in young febrile infants who usually arrive to the ED soon after the onset of fever. Thus, the identification of other predictors for neonatal sepsis is important. There is no one acceptable cut-off value of CRP for assessing an SBI in the febrile infant; however, studies use the cut-off values of 40 and 20 mg/L to rule in and rule out an SBI, respectively.25

WBC parameters are known to vary with age. NLR was shown to be positively associated with age in a healthy population,26 with the lowest NLR found in the youngest age group (age <20 years, mean 16 years). The mean value in this age group was 1.53±0.56. We did not find any report of normal ranges of NLR values for healthy neonatal or paediatric populations, though mean values for neutrophils versus lymphocytes as components of the WBC are 41% vs 45% at 1 week of age, 40% vs 48% at 2 weeks, 35% vs 56% at 1 month and 32% vs 61% at 6 months.15 This suggests a mean NLR value of between 0.52 and 0.91 for healthy children in the studied age group. Due to the significant changes in neutrophil and lymphocyte counts from birth to young adulthood, cut-off values used to distinguish infections in adults differ from those that we identified for young infants. An NLR cut-off value of >5, when sufficient exclusion criteria are used, was suggested for detecting bacteraemia or sepsis in adults.27

Hosmer and Lemeshow suggest that areas under the ROC curve of 0.70–0.80 offer ‘acceptable’ discrimination, 0.80–0.90 ‘excellent’ discrimination and ≥0.9 offer ‘outstanding’ discrimination.28 Thus, in assessment of SBI, values of ANC (AUC 0.69) and CRP (AUC 0.71), along with the combinations of CRP with either ANC (AUC 0.73) or NLR (0.72), offer similarly ‘acceptable’ discriminative ability. In assessing IBI, values of CRP, ANC and NLR, as well as the combination of CRP with either NLR or ANC, similarly offer ‘excellent’ or close to excellent discriminations. In the neonatal age group, all markers mentioned above meet the ‘acceptable’ criterion. Due to the ease of use of the single biomarkers compared with the combinations and the similarity of their discriminative abilities, we recommend clinicians to use the markers separately rather than creating a combined score.

Among our neonates, a NLR of 2 did not show statistically different sensitivity from a CRP value of 40 mg/L (52.3% vs 45.5%, P<0.001), though it had lower specificity (78% vs 97%, P=0.67) in distinguishing a SBI in the neonatal age group. Likewise, compared with the CRP value of 40 mg/L, an ANC of 7×103/µL had similar sensitivity: 56.8% (P<0.001) with a lower specificity: 84.1% (P=0.166). Therefore, we suggest that when CRP is not available, ANC of >7×103/µL or NLR >2 may raise the suspicion level for an SBI, due to their similar sensitivity to CRP, though lower specificity.

In our search for non-intuitive cut-off values, we created a decision tree (figure 4) that shows the added value of NLR to CRP in assessing febrile neonates. When CRP is high (>46.1 mg/L), so is the risk of a SBI. In the low-CRP group (<46.1 mg/L), NLR contributes to the assessment of SBI risk, lowering it by as much as 58% compared with the entire low-CRP group when NLR is not considered; and by 81% for neonates with NLR <0.77, compared with infants in the low-CRP group but with NLR >2.4. Although we currently recommend antibiotic treatment for all febrile neonates, these data aid in the assessment of SBI risk on admission to the ED, and may in the future, together with new markers, diminish the need for antibiotic use for well-looking febrile neonates.

ANC outperformed NLR and CRP in the discrimination of IBI; bacteraemia or meningitis. This finding might be attributed to the delay in rise of CRP compared with other inflammation markers. The combination of NLR with CRP, and ANC with CRP, is superior to any of the single markers.

The strengths of this study are its large cohort and being the first to test NLR as a diagnostic marker for bacterial infections in young infants. The study has some limitations. As a retrospective study, treatment of the infants enrolled was according to clinical considerations and hospital policy, and not research considerations. For example, not all the older infants underwent a full sepsis workup, though all infants of neonatal age did. We are, however, confident that we have not under called true bacterial infections, since the policy at our hospital warrants at least blood and urine cultures prior to the initiation of antibiotics for any young febrile infant and CSF cultures for any ill-looking one. Bacterial infections, such as bacterial pneumonia, gastroenteritis and arthritis, were not ruled out. However, these infections are fairly rare in this age group. Due to a low number of IBIs, the analysis in the group as a whole is more reflective of UTI than of meningitis or bacteraemia. There was a 20% rate of contaminated cultures, compared with 12%–14% in studies citing urine catheter specimen contamination rates alone in infants <24 months.29 30 Our study did not examine procalcitonin, since our aim was to study commonly available diagnostic markers.

In our comparison of various diagnostic markers for infections in young infants, we found CRP to be a valuable marker for discriminating SBI. However, CRP values are not always available. We showed that ANC and NLR, which are readily available, can aid, together with other markers of infection, in identifying children in the 1 week to 3 month age group who are at risk of serious as well as IBIs. We showed the discriminatory ability of detecting SBI infections based on a number of possible cut-off values of all tested markers, including NLR, which has not been previously studied in this age group. We recommend drawing blood for all febrile infants aged ≤3 months, and suggest using the cut-off values we determined, as well as other available ones, to aid in the management of febrile infants. The specificity of the markers studied is not sufficient to rule out bacterial infections. However, due to the reasonably high sensitivity, we recommend antibiotic use for all patients with one or more tests indicative of a possible bacterial infection, as well as for ill-looking patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Cindy Cohen for her excellent editorial assistance, would like to thank Mmes Luda Kurilionk, Natalia Paller and Stella Avrutin for their aid in collection of the data, and Dr Yair Mordish for his assistance in assessment and review of the data.

Footnotes

UH and HB contributed equally.

Contributors: UH and HB: conceived the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. UH, HB, EK, YH, TZ-B and MG: designed the study, wrote the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the data. TZ-B: performed the statistical analysis. UH: is guarantor of the paper and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work. All authors: revised the work critically and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Local Ethics Committee (Assaf Harofe Medical Centre)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Data sharing statement: Raw laboratory data are available upon request by emailing the authors

References

- 1. Judge JM. Fever in the pediatric patient. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1965;64:1171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baskin MN. The prevalence of serious bacterial infections by age in febrile infants during the first 3 months of life. Pediatr Ann 1993;22:462–6. 10.3928/0090-4481-19930801-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gomez B, Mintegi S, Bressan S, et al. . Validation of the "Step-by-Step" Approach in the Management of Young Febrile Infants. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20154381–6. 10.1542/peds.2015-4381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dagan R, Powell KR, Hall CB, et al. . Identification of infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infection although hospitalized for suspected sepsis. J Pediatr 1985;107:855–60. 10.1016/S0022-3476(85)80175-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biondi EA, Byington CL. Evaluation and management of febrile, well-appearing young infants. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015;29:575–85. 10.1016/j.idc.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Ashkenazi S, et al. . C-reactive protein as a marker of serious bacterial infections in hospitalized febrile infants. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:1776–80. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olaciregui I, Hernández U, Muñoz JA, et al. . Markers that predict serious bacterial infection in infants under 3 months of age presenting with fever of unknown origin. Arch Dis Child 2009;94:501–5. 10.1136/adc.2008.146530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Imtiaz F, Shafique K, Mirza SS, et al. . Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a measure of systemic inflammation in prevalent chronic diseases in Asian population. Int Arch Med 2012;5:2 10.1186/1755-7682-5-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lowsby R, Gomes C, Jarman I, et al. . Neutrophil to lymphocyte count ratio as an early indicator of blood stream infection in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2015;32:531–4. 10.1136/emermed-2014-204071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Jager CP, van Wijk PT, Mathoera RB, et al. . Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit Care 2010;14:R192 10.1186/cc9309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J, Du J, Fan J, et al. . The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio correlates with age in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2015;77:109–16. 10.1159/000375534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bekdas M, Goksugur SB, Sarac EG, et al. . Neutrophil/lymphocyte and C-reactive protein/mean platelet volume ratios in differentiating between viral and bacterial pneumonias and diagnosing early complications in children. Saudi Med J 2014;35:442–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yazici M, Ozkisacik S, Oztan MO, et al. . Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in the diagnosis of childhood appendicitis. Turk J Pediatr 2010;52:400–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uluca Ü, Ece A, Şen V, et al. . Usefulness of mean platelet volume and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for evaluation of children with Familial Mediterranean fever. Med Sci Monit 2014;20:1578-82 10.12659/MSM.892139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dallman PR. Rudolph AM, New YorPediatrics. sixteenth. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kass GV. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Appl Stat 1980;29:119 10.2307/2986296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breiman L, Friedman J, Charles J, et al. . Classification and regression trees. Chapman & Hall 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM, et al. . The changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33:595–9. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Gesualdo M, et al. . Early and Late Infections in Newborns: Where Do We Stand? A Review. Pediatr Neonatol 2016;57:265–73. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. . Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24422856 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stuart H, Orkin MD, David E, et al. . Thomas Look MD SELM and DGNM. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood. 8th ed: Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wesche DE, Lomas-Neira JL, Perl M, et al. . Leukocyte apoptosis and its significance in sepsis and shock. J Leukoc Biol 2005;78:325–37. 10.1189/jlb.0105017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lai MY, Tsai MH, Lee CW, et al. . Characteristics of neonates with culture-proven bloodstream infection who have low levels of C-reactive protein (≦10 mg/L). BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:320 10.1186/s12879-015-1069-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hofer N, Zacharias E, Müller W, et al. . An update on the use of C-reactive protein in early-onset neonatal sepsis: current insights and new tasks. Neonatology 2012;102:25–36. 10.1159/000336629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gomez B, Bressan S, Mintegi S, et al. . Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in well-appearing young febrile infants. Pediatrics 2012;130:815–22. 10.1542/peds.2011-3575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li J, Chen Q, Luo X, et al. . Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio positively correlates to age in healthy population. J Clin Lab Anal 2015;29:437–43. 10.1002/jcla.21791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gürol G, İH Çiftci, Terizi HA, et al. Are there standardized cutoff values for neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios in bacteremia or sepsis? http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25341467. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016 doi: 10.4014/jmb.1408.08060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Hoboken NJ. Applied logistic regression. USA: JohnWiley & Sons, Inc., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wingerter S, Bachur R. Risk factors for contamination of catheterized urine specimens in febrile children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011;27:1–4. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182037c20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tosif S, Baker A, Oakley E, et al. . Contamination rates of different urine collection methods for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections in young children: an observational cohort study. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:659–64. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.