Abstract

Functional abdominal pain (FAP) is a common childhood somatic complaint that contributes to impairment in daily functioning (e.g., school absences) and increases risk for chronic pain and psychiatric illness. Cognitive behavioral treatments for FAP target primarily older children (9+ years) and employ strategies to reduce a focus on pain. The experience of pain may be an opportunity to teach viscerally hypersensitive children to interpret the function of a variety of bodily signals (including those of hunger, emotions) thereby reducing fear of bodily sensations and facilitating emotion awareness and self-regulation. We designed and tested an interoceptive exposure treatment for younger children (5–9 years) with FAP. Assessments included diagnostic interviews, 14 days of daily pain monitoring, and questionnaires. Treatment involved 10 weekly appointments. Using cartoon characters to represent bodily sensations (e.g., Gassy Gus), children were trained to be “FBI agents” – Feeling and Body Investigators - who investigated sensations through exercises that provoked somatic experience. 24 parent-child dyads are reported. Pain (experience, distress, and interference) and negative affect demonstrated clinically meaningful and statistically significant change with effect sizes ranging from .48–71 for pain and from .38–.61 for pain distress, total pain: X2 (1, n=24) = 13.14, p < .0003. An intervention that helps children adopt a curious stance and focus on somatic symptoms reduces pain and may help lessen somatic fear generally.

Keywords: interoceptive awareness, interoceptive exposure, functional abdominal pain, visceral hypersensitivity, somatic fear, anxiety, anorexia nervosa

Introduction

Complaints of abdominal pain are the most frequently reported somatic symptom in pediatric primary care practices occurring in ≥10% of children (Ramchandani, Hotopf, Sandhu, Stein, & Team, 2005). According to the Rome III Committee, when this pain occurs for at least 2 months in either an episodic or continuous fashion and cannot be ascribed to an inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process, then a diagnosis of functional abdominal pain (FAP) is warranted (see footnote for Rome IV information Hyams, et al., 2016; Rasquin, et al., 2006)1. If childhood FAP remains untreated, the prognosis is poor (Campo, et al., 2001). Individuals with FAP in childhood have been shown to develop chronic abdominal pain, other pain diseases, and psychiatric disorders in later life (Campo, et al., 2001; Campo & Gilchrist, 2009; Christensen & Mortensen, 1975). Concurrently, children with FAP are significantly more likely to have one or more psychiatric disorders: Campo et al. reported that 43% of 8–15 year-old children presenting to primary care with FAP had a depressive disorder and 79% had an anxiety disorder (Campo, et al., 2004). Thus, while early pain appears to be a vulnerability factor, how pain increases vulnerability to the emergence of mental health symptoms is unclear.

Individual differences in pain sensitivity have been hypothesized as vulnerability factors for pain disorders (Leeuw, et al., 2007): young children with pain may be more sensitive to the experience of visceral sensations than children without GI symptoms (Simrén, et al., 2017). Work by Simrén et al. (2017) demonstrated that visceral hypersensitivity, objective sensitivity to changes in visceral sensation, was associated with the intensity of GI symptoms across five independent cohorts of children (a combined total of over 1000 patients). This sensitivity, in turn, may not only guide attention towards the body, increasing preoccupation, but may also increase the likelihood that these interoceptive sensations are experienced as aversive and potentially fear-provoking.

The social environment may augment visceral sensitivity in vulnerable children (J. W. Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). The absence of a precise medical cause for FAP leaves some parents in search for alternative explanations for their child’s pain; indeed, FAP accounts for significant, often unnecessary, healthcare expenditures, and is the leading cause of outpatient physician visits due to a gastrointestinal complaint (Lindley, Glaser, & Milla, 2005; Nyrop, et al., 2007; Peery, et al., 2012). As a consequence of these frequent visits, some children may fear there is something wrong with their bodies that remain untreated. Subsequently, children with an early history of pain may learn to fear and be preoccupied with even innocuous somatic sensations (Crombez, Van Damme, & Eccleston, 2005; Harvie, Moseley, Hillier, & Meulders, 2017).

An elegant and well-studied model of individual vulnerability to the emergence of chronic pain and pain -related fear is the Fear Avoidance Model. The Fear Avoidance Model is a comprehensive framework designed to explain the transition from acute to chronic pain via learning theory (Leeuw, et al., 2007; Lethem, Slade, Troup, & Bentley, 1983; J. W. Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000; J. W. S. Vlaeyen & Linton, 2012). By way of a brief and oversimplified summary, the model suggests that the association of pain with fear is adaptive in that pain is a signal of threat and potential injury. With experience, combined with individual vulnerability, cues that may predict the future experience of pain may produce avoidance and/or escape behaviors that are negatively reinforced in the short term due to the avoidance or reduction of pain. However, in the long term, these behaviors may promote disuse, functional disability, and depression via the avoidance of activities and related reinforcing environmental events (Leeuw, et al., 2007).

Several observations gleaned from the systematic study of this model are relevant for the current intervention. First, while cognitive vulnerabilities such as pain catastrophizing and anxiety sensitivity have been most frequently studied in adult samples of pain (Leeuw, et al., 2007), individual differences in the experience of pain intensity may also be a vulnerability for pain chronicity (Simrén, et al., 2017; J. W. S. Vlaeyen & Linton, 2012). Correspondingly, in young children, for whom abstract beliefs and the capacity to predict future harm is emerging, the intensity of pain experience may be a more relevant vulnerability factor than cognitive vulnerability factors (Simrén, et al., 2017). Second, interoceptive cues can become conditioned to signal the onset of pain and thus, fearful reactions to innocuous interoceptive cues can emerge. For example, hunger can signal future hunger pain, and the somatic sensations of anxiety, which may occur with pain predictions, can become feared. Third, the use of exposure-based strategies in the treatment of chronic pain continues to evolve, but generalization to novel contexts is relatively poor. Exposure to interoceptive cues, cues that are ubiquitous across contexts, may be a particularly efficacious strategy to facilitate generalization of treatment effects. Consequently, early training that helps children to develop a curious stance to body sensations via interoceptive exposures conducted in a playful context may teach them to differentiate pain from other sensations, to have less fear-based reactions to bodily change, and, in turn, to provide far-reaching emotion awareness and regulatory capacities. These capacities, in turn, may alter harmful illness trajectories in both pain and psychiatric domains (Drossman, 2006).

Such training may be particularly efficacious prior to puberty as sensitivity to visceral change and bodily preoccupation may become further amplified during the physical changes of puberty. Panic disorder and anorexia nervosa increase in incidence during puberty (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Reed & Wittchen, 1998). These two disorders are also characterized by fears of somatic sensations, are associated with extreme disability, and, in the case of anorexia, elevated premature mortality (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, & Nielsen, 2011; Duits, et al., 2016; Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, & Agras, 2004; Kessler, et al., 2006; Papadopoulos, Ekbom, Brandt, & Ekselius, 2009). During adolescence, neural circuits which attribute salience and meaning to aversive interoceptive stimuli are maturing (Ernst, Romeo, & Andersen, 2009) and these interpretations become increasingly elaborated with context (Li, Zucker, Kragel, Covington, & LaBar, 2016). This occurs while prefrontal circuits that prioritize behavior are also maturing. Combined, this suggests that an intervention that shapes the interpretation of interoceptive signals and links these signals with adaptive behavior prior to puberty may have the possibility of circumventing maladaptive interoceptive conditioning (Korterink, Devanarayana, Rajindrajith, Vlieger, & Benninga, 2015).

Despite the prevalence and consequences of early abdominal pain, there are no interventions that specifically target very young children (Eccleston, et al., 2012; Levy, et al., 2010). Effective interventions for older children include parents, have a somatic component (e.g. relaxation skills), and often address pain catastrophizing (Levy, et al., 2010; Levy, et al., 2006). However, mental health symptoms are inconsistently responsive to these interventions and the focus on distraction and minimization of pain experience inherent in many interventions for children has led to some concern that children may be learning to stop reporting their pain while not altering pain experience (Eccleston, et al., 2012; Levy, et al., 2010). Further, diversion away from an informative sensation may be a missed opportunity for a child to learn about and gain trust in their body’s function and develop emotion regulation skills. This is particularly critical at younger ages when children are first learning to associate bodily sensations with specific emotional and motivational states (Hietanen, Glerean, Hari, & Nummenmaa, 2016).

Notably, approaches that incorporate a deliberate, mindful, and accepting (objective, nonjudgmental, present) focus on pain have increasingly been incorporated into adult approaches for pain management and are increasingly recommended for children (Palermo, 2009). The prior rationale for the use of distraction in pain management was that the diversion of attention could directly alter the gain of dorsal spinal afferents conveying painful stimuli (Sprenger, et al., 2012). Thus, distraction was proposed to directly reduce pain experience. While this strategy has proven effective for some individuals, the incorporation of more directed attention, acceptance-based approaches for adults suggests at the very least that these strategies may not work for everyone (Hughes, Clark, Colclough, Dale, & McMillan, 2016). Yet, there is recognition for the need of more rigorous trials to examine the efficacy of acceptance-based approaches in pain management (Hilton, et al., 2016). For children, we propose that the broad value in training interoceptive sensitivity (defined here as the ability to sense and accurately decipher interoceptive signals) in terms of enhanced emotion awareness and improved self-regulation provides a rationale for attention focused approaches to pain management in children.

In the current study, we build on CBT approaches in creating an acceptance-based interoceptive exposure treatment for young children (5–9 years old) with abdominal pain. Treatment was designed to address three goals: 1) promote a playful and curious approach towards body signals (as opposed to vigilance and fear) by teaching children to be “FBI Agents,” i.e., Feeling and Body Investigators; 2) provide caregivers and children with a decision-tree to help children describe, label, and interpret the meaning of somatic signals using cartoon characters as metaphors for body experience (e.g., Gassy Gus, Betty the Butterfly), and 3) employ strategies that attempt to respond to the bodily need and notice how the body changes. We hypothesized that this approach would not only reduce pain intensity, frequency and distress, but also would improve often accompanying mental health symptoms.

Patients and Methods

Recruitment and Enrollment

An attempt was made to assess all children in the appropriate age range presenting at a pediatric primary care clinic. Referrals from primary care providers within the designated practice were also accepted for screening and possible enrollment. The intervention focused on a narrow age-window (5 –9 years) relative to prior treatments for FAP because this window represents the developmental period during which children are beginning to differentiate and interpret the meaning of diverse bodily sensations (Hietanen, et al., 2016). Criteria for screening were as follows: a) ages between 60 months (5 years) and 119 months (9 years, 11 months) on the day of screening, b) accompaniment by a legal guardian fluent in English, c) access to the Internet or a mobile phone with video chat capabilities, and d) a positive screen for FAP using the Questionnaire on Pediatric Gastrointestinal Symptoms, Rome III Version (QPGS-RIII) (Drossman, 2006). A positive screen is met if either: 1) the child has 2 or more stomachaches associated with impairment; or 2) the child has 8 or more stomachaches with or without any associated impairment over a two-month period. Children with a diagnosed history of mental retardation (IQ < 70) or any other pervasive developmental disorder were not eligible for enrollment. The presence of an exclusionary developmental disorder was determined based on medical chart abstraction. Additionally, parents and children who failed to complete at least 50% of the first 14 days of pain monitoring were excluded from further participation.

Pre and Post-Treatment Assessments

The assessment battery included a semi-structured diagnostic interview administered to the parents (Preschool Aged Psychiatric Assessment, PAPA)(Egger, et al., 2006; Sterba, Egger, & Angold, 2007); a 2-week period of pain-diary collection completed by parent and child; and a battery of self-report questionnaires assessing parent and child mental health, emotion regulation, and pain symptoms. Additional questionnaires and a laboratory mood-induction task probed exploratory moderators and mediators of treatment effect. This paper presents results on the primary study outcomes, child reports of pain and negative affect and parent reports of the child’s pain, distress regarding pain, interference from pain, and negative and positive affective symptoms. This study was under-powered to detect mediation and moderation, but the full battery was administered to assess feasibility.

Psychiatric Diagnosis

The PAPA is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that was developed to assess psychiatric diagnoses in preschool-aged and young children. The test-retest reliability and validity of this interview has been established (Egger, et al., 2006; Sterba, et al., 2007; Wichstrom, et al., 2012). The interview was designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of a preschooler in his or her social and emotional context. We chose to focus on domains of affective and anxiety disorders given their frequent association with pain disorders, and ADHD, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorders to assess the appropriateness of this treatment strategy for children with behavioral dysregulation. The interview assesses the three month interval and was used to characterize the baseline characteristics of our sample.

Pain and affect monitoring

Diaries included both parent reports of child experience and child reports of their own experience and were completed three times daily (beginning of day, before dinner, and end of day)(Vetter, 2011). The end of day assessments differed from the prior 2 daily assessments in that it served as summary for the day (described below). Diaries included the following components: 1) abdominal pain intensity measured with a “pain thermometer” (parent- and child-report) (Schachtel & Thoden, 1993); 2) an item written for the study assessing child’s distress about abdominal pain (parent-report); and 3) child’s affective valence using the Self-Assessment Manikin- valence, child report (Bradley & Lang, 1994; von Leupoldt, et al., 2007). During the course of treatment, these diaries were simplified to include only end of day summary ratings. Each aspect of the assessment diary is described in more detail below.

Pain

We opted for a pain thermometer and separate measure of child pain distress and affect as we were interested in separating out the experience of pain from distress related to pain or general affect. There is concern that faces scales used to measure pain confound these two constructs (Tomlinson, von Baeyer, Stinson, & Sung, 2010). This pain assessment contains a colored graphic of a thermometer with more intense shades of red (the “mercury”) corresponding to the intensity of pain experience. Levels of red were also numbered (from 0 to 12) and verbal anchors were provided from “no pain” to the “worst possible pain imaginable.” The presence of multiple sources of information (visual, numeric, verbal) guided the selection of this pain thermometer (the Iowa Pain Thermometer)(Herr, Spratt, & Garand, 2007). Instructions for the item at the beginning of the day and before dinner asked “Using the pain thermometer, please rate the intensity of your child’s tummy pain at this moment by circling the number that best matches your child’s current tummy pain.” The child item read “Please ask your child how much tummy pain he/she is in right now. He/she can point to a number or line on the pain thermometer. The end of day pain item was only completed by parents and instructed parents “What is the highest level of tummy pain that your child reached today?” Parents were trained in pain recognition using the FLACC scale (Faces, Legs, Arms, Crying, Consolibility) which gives them behavioral anchors to help rate pain intensity to help them make global ratings on the pain thermometers (Merkel, Voepel-Lewis, Shayevitz, & Malviya, 1997) and children were given examples of different levels of pain intensity. Reliability and validity of assessment of pain via a visual thermometer (specifically the Iowa Pain Thermometer employed) has been established, it has been employed in pediatric and vulnerable populations, and is sensitive to change (Chordas, et al., 2013; Kim, et al., 2011; Vetter, 2011; Ware, et al., 2015).

Pain Distress

The pain distress item for the beginning of day and prior to dinner read: “How distressed is your child about tummy pain?” – with responses ranging on a 5-point scale from “Not at all” to “Extremely.” The end-of-day pain distress item read: “Today, my child was distressed about his/her tummy pain” with responses ranging on a 5-point scale from Never to Almost Always.”

Affective Symptoms

Items assessing negative affect were taken from parent proxy items of emotional distress and pain interference from the NIH PROMIS® measurement system (Irwin, et al., 2012). This measurement system provides reliability and validity at the item as well as the scale level, allowing for flexible use in the assessment of relevant constructs (see Irwin et al. (2012) for the development and validation of this item bank). Sample items used from the emotional distress scale included “My child felt sad” and “My child felt nervous” rated on a five point scale from never to almost always.

Interference from Pain

The NIH PROMIS® parent proxy pain interference scale, included eight items rated on a five point scale from never almost always. A sample item included “My child had trouble sleeping when he or she had tummy pain.” See Irwin et al. (2012) for information on scale reliability and validity.

Treatment

The 10-week therapy regimen trained children to become “Feeling and Body Investigators”, aka FBI Agents. In Session 1, parents were provided a formulation of their children as “sensitive individuals,” sensitive to their own internal experience and potentially to the world around them. This sensitivity was framed as a gift, one that enabled their children to live a more vibrant and vital life and potentially, to be more sensitive to the experience of others as well as their own experience. However, it also meant that their children were more sensitive to pain and the sensations of negative emotional experiences. The use of the extended metaphor of body detectives was explained as designed to help children develop a playful and curious framework around this sensitivity. A similar narrative – but relayed in simpler terms such as having “sensory superpowers” was given to the children. Children were told that we (parent/child/therapist) would become body detectives, investigating bodily clues to learn more about what our bodies are trying to tell us.

Children were then guided in the development of a body map in which they lay on a large piece of butcher paper and had their parent trace the outline of their figure. The children decorated this figure and put an “x” in the body areas where they were likely to experience pain. The sheet was framed as their body map - just as a detective might make a crime map to keep track of clues. Everything new that was learned about the body was to be added to that sheet. Following this introduction and body map creation, workbook pages were read to introduce the children to particular body sensations. Interoceptive exposure exercises were conducted (“body investigations”) based on one or two of the sensations. The new knowledge acquired about the body from these exposures was then added to the body map. Following this, a body brainstorm worksheet was completed, and homework assigned. Each of these components will briefly be described in turn.

Workbook

To make the treatment developmentally accessible, metaphorical characters were used to educate parent-child dyads about body sensations, e.g. Gassy Gus, Betty Butterfly, etc. (see Figure 1). In each session, new body sensation characters were introduced via workbook pages. These pages included the message the body sensation may be communicating and the situations the sensation is likely to arise.

Figure 1. Body characters of the FBI intervention.

Characters were used to portray different bodily sensations. A few new characters were learned each session. The program started with more basic sensations such as hunger and fullness and progressed onto sensations of emotional experience (for example, Ricky the rock, Betty butterfly, Julie jitters) and different forms of pain (for example, Patricia the poop pain, Harold the hunger pain). Study Characters, © 2017 Duke University. All Rights Reserved.

Body Investigations

In session, parent-child dyads were guided through “body investigations” in which bodily sensations were provoked to explore a body mystery. For example, the child may have assessed what makes him/her more nauseous, being spun around in a chair for 30 seconds or twirling for 30 seconds. Or the child may guess how fast they could run down the hall with a belt fastened tightly around her belly to cause discomfort. Following each body investigation, the new information the child learned about his or her body was added to the body map in the form of a statement or picture.

Body Brainstorms

Body brainstorms were designed to facilitate generalization by linking the sensation experienced during the body exposure to other sensations the child encounters in daily life. For example, for body investigations regarding the heartbeat, the child may be asked to list three things that make her heart beat faster and three things that make her heart beat more slowly.

Homework

Finally, a worksheet was developed to guide the parent and child to understand the message a particular bodily sensation was communicating, and to guide the child in a strategy to explore the need communicated by that sensation (Figure 2). For example, in Step 1: Listen to your Body, a child might notice Betty the Butterfly and Henry the Heartbeat. In Step 2: Conduct an Investigation, he/she may indicate that he/she was taking a math test. This step was designed to teach child and parent to contextualize body sensations so that they learned that similar sensations can have different meanings depending on the context. In Step 3: Take a Guess at What the Sensation may Mean, the child guesses the meaning of the sensation (for example, he/she may decide that her body was telling her she was nervous). In Step 4: Try a Strategy and See What Happens, he/she could then try one of the suggested strategies (e.g., drawing a picture about it, get a hug) and evaluate the subsequent effects on his/her body. Importantly, the goal of these explorations is not to change an emotion or end pain. The intention is to train the children to be curious observers of their bodies and to view their bodies as a source of useful information that can tell them what they need. Body missions were tasks designed to encourage children to continue daily functioning and activities – such as going to school – even in the presence of visceral pain.

Figure 2. Worksheet for the FBI intervention.

Sections of the worksheet were added as the intervention progressed. The goal of the worksheet was to help children learn to understand the messages of bodily experiences and to respond to those messages in an investigative fashion. The intention was to teach children that bodily signals communicate needs and if you listen to your body and learn more about what you need to get to know yourself and trust yourself and your body. Contact the first author for intervention materials (Nancy.Zucker@duke.edu).

Sessions 2–10 followed a similar format. Homework sheets were reviewed and new things learned about the body were added to the body map. Workbook pages were read with new characters added. A body investigation was done with two or three these characters. New knowledge was added to the body map. A body brainstorms worksheet was completed and homework assigned for the following week. Sessions five and seven were completed via video chat in the home to facilitate generalization. At the successful conclusion of treatment, children were graduated as “FBI Agents.”

Data Analysis

The analysis cohort was comprised of 24 parent-child dyads. Parent and child ratings of child pain, the primary outcome, were obtained three times daily for a 14-day pretreatment period and, equivalently, for a 14-day post treatment period. Parents rated the intensity of their child’s pain, the child’s distress about the pain, and the child’s positive and negative affect. The child rated their pain intensity 3 times daily (overnight, morning, evening) and negative affect twice daily (morning, evening). For analyses, ratings were aggregated to derive a single pre-treatment and single post-treatment score. Mean daily ratings both pre- and post-treatment are also presented graphically (Supplemental Figure 1a–1c), and as weekly means throughout the course of treatment (Supplemental Figure 2a and 2b). Because missing data were minimal, scores were averaged using available data without imputation. Resulting pre- and post-treatment scores were tested using generalized linear models (SAS 9.4: PROC GENMOD) based on generalized estimating equations. This class of models accommodates correlated (clustered) data as well as a variety of distributions including those employed for these analyses: Gaussian, binomial (logistic), and gamma. Because of diurnal variation, ratings were tested by time-of-day (morning, evening, and end-of-day) in addition to aggregate measures for daily pain, pain distress, and negative affect. Pain diary scores were regressed on a dichotomous proxy variable denoting phase (pre- versus post-treatment). Experiment-wide error rates were controlled using Bonferroni adjustments for same-scale measurements over time. In a second series of analyses, effect sizes for the distress, affect, and pain measures were calculated at the various daily test intervals. Effect size metrics for each subject at each measurement interval were again aggregated from the 14-day daily ratings in the pre- and post-treatment test phases and averaged across subjects by phase. In addition to testing actual pain diary scores, outcomes were modeled in a second series of analyses based on pre- versus post-treatment response rates. Aggregated mean pain diary scores for each subject (calculated as described above) were used to define responders as follows: Parent report of child pain: responders had an average rating < 1.00 signifying below minimal levels of pain; Parent report of the child’s pain distress: responders had an average rating of < 0.50; Child pain: responder <= 0.50; Child negative affect: responder: < 3.00, signifying an average positive mood. Changes in the proportion of responders at post-treatment were tested as described above when using logistic regression procedures to regress the dichotomous proxy denoting responder status on a dichotomous proxy variable denoting phase with subject treated as a within condition (SAS 9.4: PROC GENMOD). While the boundaries for responder delineated above were based on clinical utility, we also report a range of responding outcomes based on proportion of symptom change of 15%, 30%, and 45%. As above, inference levels were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni procedures.

Results

Sample demographics

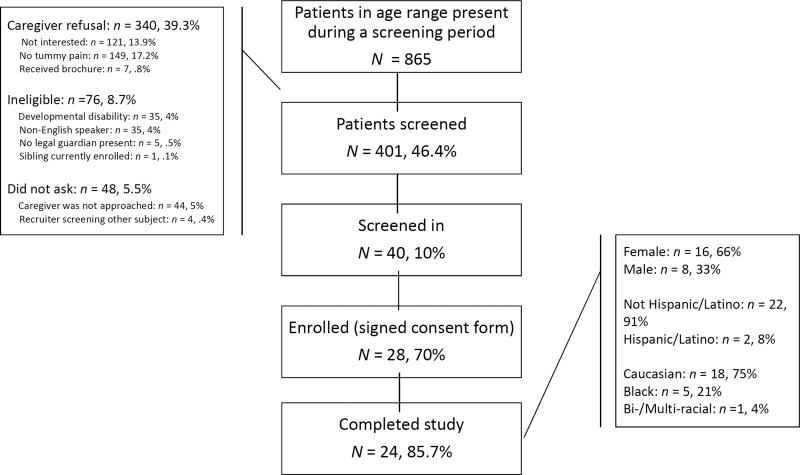

The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 3. Study recruiters were able to screen 46.4% of the 865 children in the eligible age range who presented to primary care during the screening period. Of those screened (n=401), 10% met screening criteria for FAP of which 70% were enrolled in the study. 85.7% of the sample completed the required dose of session and post-intervention data collection. Table 1 describes the demographic and baseline characteristics of the 24 families that made up the study cohort. The majority were Caucasian (75%), female (66%), and Non-Hispanic (91%). The average age was 7.14, with a range of 5.54–9.32. The average number of stomachaches assessed during the three-month pre-treatment period covered by the PAPA interview was 53.8 (9.5) - or about four per week- with an average duration of 2.7 hours (.8)(Egger, et al., 2006). The children experienced several somatic symptoms including headaches with an average frequency of 15.6 (5.1) - or about one per week- with an average duration of 1.9 hours. The majority met criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder with Generalized Anxiety Disorder diagnosed in over half the sample and Separation Anxiety Disorder diagnosed in a about a third (Egger, et al., 2006; Sterba, et al., 2007).

Figure 3. Recruitment and Eligibility Flow Diagram.

An active recruitment strategy was employed in which recruiters remained on-site at a pediatric primary care practice. Nurses asked families deemed eligible by age and medical chart review if they were interested in learning more about a treatment study for abdominal pain in children aged 5 to 9 years old. In this manner, we attempted to screen all potentially eligible children presenting to primary care.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| Family context characteristics | |

|

| |

| Age Biological Parent 1 (n=24) | Range: 25–50 |

| Average (std): 39.25 (6.7) | |

|

| |

| Age Biological Parent 2 (n=24) | Range: 24–57 |

| Average (std): 42.25 (7.5) | |

|

| |

| Age Non-Biological Parent 1 (n=4) | Range: 36–57 |

| Average (std): 49.00 (9.5) | |

|

| |

| Age Non-Biological Parent 2 (n=1) | Range: 57 |

| Age: 57 (n/a) | |

|

| |

| Family Organization | % Divorced (of P1 & P2): 4.17% |

| % Single parent: 4.17% | |

| % in 2 parent home (Includes Grandparent as second parent): 100% | |

| % Adopted: 4.17% | |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | 8.3% Hispanic (n=2) |

|

| |

| Education | % completed HS: 97.96% |

| % completed 4 year college: 77.55% | |

| % completed graduate work: 40.82% | |

|

| |

| SES | % Medicaid or CHIP: 16.67% |

| % Food stamps: 17.39% | |

| % Enrolled in state entitlement: 8.33% | |

|

| |

| Subject characteristics | |

|

| |

| Subject’s Age | Range: 5.54–9.32 Years Old |

| Average (std): 7.14 (1.12) | |

|

| |

| Subject’s Sex | 66% female |

| 34% male | |

|

| |

| Subject’s Race | 75% White (n=18) |

| 20.8% Black (n=5) | |

| 4.2% Biracial (n=1) | |

|

| |

| Stomach Achea: mean (standard error) | Frequency: 53.8 (9.5) |

| Duration: 2.7 hours (.9) | |

|

| |

| Head Achea : mean (standard error) | Frequency: 7.1 (3.0) |

| Duration: 2.6 hours (.7) | |

|

| |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | 58.3% Generalized Anxiety Disorder (n=14) |

| 29.2% Separation Anxiety Disorder (n=7) | |

| 16.7% Social anxiety (n=4) | |

| 4.2% Major Depressive Disorder (n=2) | |

| 4.2% Oppositional Defiant Disorder (n=2) | |

| 4.2% ADHD (n=2) | |

Note: n=24 unless otherwise specified. Caregivers who have regular access to the child’s care included in this description, although only the caregiver with the greatest access the child was used for data collection.

= over a 3-month period, so an average of four stomachaches per week.

Pain reduction

Average post-treatment parent ratings of child pain were substantially and significantly reduced below pre-treatment levels (Figure 4) with typical decreases in excess of 50–60%. Given the difference in instructions, highest pain ratings occurred at the end of the day. Ratings at all measurement intervals were statistically significant with estimated p-values substantially below Bonferroni-adjusted levels. Decreases in ratings among children for pain were of a similar magnitude and were also statistically significant (Figure 4). Using the conventions suggested by Cohen (1988), average effects sizes of parent ratings of child pain were in the medium/large (0.7) range. Effect sizes for both child ratings were of large magnitude (0.9). These pre- and post-treatment outcomes are also presented graphically as daily means in Supplemental Figure 1a–1c. In a series of main effects repeated measures regressions stratified by time-of-day, daily pain(pain distress) measurements were regressed on a dichotomous proxy variable denoting treatment interval (pre = 0; post =1) and time (days 1–14), the proxy variable denoting treatment phase was significant in all instances. In a second set of interaction models, the above analyses were re-estimated after the inclusion of an interaction term crossing phase and time. In no instance did the latter term approach significance (data not shown). Thus, levels of pain and pain distress were constant during the two week pre- and post-treatment assessment intervals, but different between pre- and post-treatment.

Figure 4. Parent ratings of child pain and child pain distress.

Parents rated their child’s pain for two weeks prior to the intervention and two weeks post-intervention. Ratings about pain were made at several time points: overnight – assessed as soon as the child woke up; beginning of day, between 6 and 9 AM; before dinner – between 5 PM and 8 PM; end of day, approximately between 7 PM and 9 PM. End of day ratings reflected worse pain experienced during that day and overall mood throughout the day. Total effect sizes reflect all individual data points combined across all time periods. All posttreatment scores were significantly below Bonferroni corrected levels of significance.

Weekly changes in pain, pain distress, nervousness, and anxiety during by treatment session are presented in Supplemental Figure 2a and 2b, provided along with model parameter estimates. These results are based on end-of-day daily diaries in which a parent rated the child’s worst pain of the day, overall mood, and overall distress about pain. Mean weekly parental pain (distress, nervousness, fear) ratings were regressed on session number. Models were estimated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) methodology using SAS PROC GENMOD (SAS 9.3) specifying first-order autoregressive structure. To accommodate data skew and curvi-linearity, models were estimated using an assumed gamma distribution with a log link. In all instances, the estimated coefficient associated with slope was significant and sign negative, with corresponding p-values: changes in pain per parent report (p = .015), child report (p = .011), parent report of child pain distress (p < .001) and negative affect (p = .013).

For responder analyses (also see Supplemental Table 1a and 1b), daily scores aggregated over the 14-day pre- and post-treatment intervals were averaged and classified on a dichotomous basis as above or below threshold as described above. The subsequent dichotomous proxy denoting responder status was tested for pre-post differences using generalized linear regression procedures (SAS 9.4: PROC GENMOD) clustered on subject. Mean number of children classified as responders according to parent pain ratings was in excess of 75% (n = 18–21) at all times of day. Child ratings of pain response exceeded 85% (n=21) at both daily periods (Supplemental Table 1a). We also conducted responder analyses corresponding to a proportion of change in pain at levels of 15%, 30%, and 45%. Percentage of responders ranged from 75%, 50%, and 37.5%, respectively, for parent reports of child pain; 58%; 50%, and 37% for child reports of pain; and 62%, 38%, and 13% for parent ratings of child pain distress. Bonferroni-adjusted differences at all time points were statistically significant for both parents and children excepting the evening parent rating.

Distress about pain

An important goal of the FBI intervention was to decrease a child’s fear of bodily sensations as operationally reflected in parent ratings of child pain distress. Concordant with decreased ratings of pain noted above, post-treatment parent ratings of the child’s pain distress were substantially reduced relative to pre-treatment levels (Figure 4) at all measurement intervals. Magnitude of the decreases varied from approximately 60–70%, with corresponding effect sizes, on average, in the medium range (0.6) (Figure 4); Bonferroni-adjusted statistics were significant at all three measurement intervals and in the aggregate.

Pain Interference

Pre- to post-treatment parent-reported measurements of pain interference (PROMIS Pain interference measure) were significantly decreased (approximately 14%) from pre-treatment levels; Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in affect and pain interference

| Positive Affect | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Post-Pre | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Time of Day | N | Mean | SE | N | Mean | SE | Diff | SE | χ2 | Pr > χ2a | ES |

| Morning | 24 | 3.78 | 0.16 | 24 | 3.89 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.78 | 0.1523 | 0.16 |

| Evening | 24 | 3.89 | 0.15 | 24 | 3.90 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.8997 | 0.04 |

| End of Day | 24 | 3.74 | 0.14 | 24 | 3.84 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.46 | 0.2275 | 0.21 |

| Total | 24 | 3.75 | 0.15 | 24 | 3.82 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.4019 | 0.14 |

| Negative Affect | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Post-Pre | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Time of Day | N | Mean | SE | N | Mean | SE | Diff | SE | χ2 | Pr > χ2a | ES |

| Morning | 24 | 1.34 | 0.06 | 24 | 1.16 | 0.04 | −0.17 | 0.06 | 6.12 | 0.0134 | 0.30 |

| Evening | 24 | 1.36 | 0.07 | 24 | 1.13 | 0.03 | −0.23 | 0.07 | 7.11 | 0.0077 | 0.39 |

| End of Day | 24 | 1.41 | 0.08 | 24 | 1.22 | 0.05 | −0.19 | 0.08 | 4.88 | 0.0272 | 0.37 |

| Total | 24 | 1.35 | 0.06 | 24 | 1.15 | 0.03 | −0.19 | 0.06 | 7.01 | 0.0081 | 0.46 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Pain Interference | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Post-Pre | ||||||||

| Time of Day | N | Mean | SE | N | Mean | SE | Diff | SE | χ2 | Pr > χ2 | ES |

| End of Day | 24 | 1.35 | 0.08 | 24 | 1.16 | 0.06 | −0.19 | 0.06 | 6.78 | 0.0092 | 0.63 |

Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.0124

Note : Positive affect items assessed the child’s intensity of calm and cheerful affect. Higher scores indicate stronger positive emotions. Negative affect items assess nervousness and sadness. Higher scores indicate more intense negative moods.

Positive and Negative Affect

Positive (calmness, happiness) and negative affect (sadness, nervousness) of child affect per parent report are summarized by time of day as well as an aggregate (Table 2, Figure 4). Results at all time points and for both informants were similar: Per parent proxy report, positive affect (calmness, happiness, cheer) remained essentially unchanged from the pre- to post-treatment phases. In contrast, negative affect (sadness, nervousness) significantly decreased by- approximately 15% at post-treatment, excepting the end-of-day rating where significance remained above the Bonferroni-adjusted inference level. The average change in negative affect was of medium effect size (.5). Child reports negative affect also decreased significantly with a large effect size (.8, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Child ratings of pain and negative affect.

Children rated their pain for two weeks prior to the intervention and two weeks post-intervention. Ratings about pain and negative affect were made at several time points: beginning of day, between 6 and 9 AM and before dinner – between 5 PM and 8 PM. Total effect sizes reflect all individual data points combined across all time periods. All posttreatment scores were significantly below Bonferroni corrected levels of significance.

Discussion

Our approach represents one of the few attempts to develop a treatment specifically for younger children with FAP and to our knowledge, one of the few that deliberately induces exposure to pain experiences in young children. Parent and child reports demonstrated pre- to post-treatment reductions in pain with the magnitude of effect sizes in the moderate to large range. Emotional reactions to pain and interference due to pain were similarly decreased, the former by similar magnitudes. These findings demonstrate that deliberate exposure to pain related sensations not only does not exacerbate pain experience but can actually reduce pain-related distress. Responder analyses resulted in significant change (ranging from 79–85% response percentage) defined based on a threshold of pain free days. The one exception was evening pain. In our responder analysis, the pain rating that occurred right before dinner did not survive correction. Notably, at baseline, this time period already demonstrated a high percentage of individuals at the threshold for pain-free days. Thus, before dinner time may be a relatively pain-free period relative to other times of day. Heading into an evening with parents may be viewed as less stressful than other times of day.

Moreover, it is unlikely that change can be attributed to reductions in the child’s reporting of pain, but in fact reflects actual reductions in pain experience. To wit, children were encouraged to report pain and such reports were met with “investigative curiosity” (e.g., What sensations were you noticing in your body? What message was your body trying to tell you? Was it is type of emotion? Was it a type of pain?). Prior CBT strategies have attempted to help parents redirect their child’s attention from pain, a strategy that have raised some concerns that what is changing is the child’s reporting behavior rather than their pain experience. An additional limitation to a strategy based on distracting the child’s attention from pain is that such a strategy may inadvertently invalidate the child’s experience of his/her body, potentially disrupting the child’s learning to recognize and decipher the meaning of various somatic signals.

Children (and adults) with pain often are characterized as viscerally hypersensitive, a vulnerability that may lead to increased reactivity to visceral sensations (Mayer & Gebhart, 1994). Whether due to the intensity of visceral sensations, social modeling of pain catastrophizing, or both, visceral experience is often met with distress and fear. Such reactions can subsequently generalize beyond those that signal pain to even innocuous bodily signals (e.g., hunger pains, gas), and bodily signals of emotional experience. Fear of bodily sensations, and subsequent attempts to suppress or avoid those sensations, can inadvertently eliminate informative messages communicated by these somatic experiences. This muting of informative sensations may retard or stultify the emergence of adaptive capacities related to them including emotional self-regulation. Against this background, further evidence of the success of our treatment strategy is indirectly related to our findings of reductions in pain-related negative affect (also see Zucker et al. for changes in the ability to discriminate emotion from pain)(Zucker, Lewis, Davila-Hernandez, Egger, & Porges, Manuscript in preparation). These latter results derive from a novel movie mood induction task in which children are asked to indicate changes in bodily sensations (e.g., perceived changes in heartbeat, gut motility, hunger, and pain) and label changes in emotional experience. Demonstration of interoceptive discrimination would occur if changes in somatic volatility (e.g., increased gut motility) could occur in the absence of increased perceived pain experience. As this task is still being validated, we elected to present the development and preliminary results of this task in a separate manuscript.

The motivation for our approach, with its focus on identifying, decoding, and accepting interoceptive gut sensations, emerged from prior research on interoceptive exposure interventions for panic disorder (Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek, & Vervliet, 2014). In panic disorder, not only is there a catastrophic reaction to an innocuous bodily sensation (such as the heartbeat), but also fear of sensations generalizes such that individuals try to avoid the anxious “panic” response to these bodily sensations. Over time, an increasing number of situations are avoided for fear that they will evoke the feared bodily sensations. During exposure therapy, feared bodily sensations are intentionally evoked and new learning occurs: individuals can experience these feared sensations without social (people do not think you’re going crazy) or physical consequence (no heart attack) (Craske, et al., 2014). Our strategy can be considered a developmentally-sensitive melding of these approaches: behavioral exposure exercises provide new learning about the meaning and danger of body signals; body missions decrease behavioral avoidance; and we attempt to promote generalization of non-fear-based reactions by altering in the context in which bodily sensations are experienced. Rather than fear, body signals beckon curiosity and are a source of valuable information. Thus children are taught to learn from bodily sensations and use it to guide adaptive behavior: a developmentally informed acceptance-based approach.

Yet, despite this focus on pain-acceptance, children and parents were asked to monitor pain, a strategy that may have provided mixed messages. While this was of practical necessity to demonstrate the effects of this pilot intervention, yet, there may be more efficacious strategies that are more consonant with an acceptance framework. One example is to have children monitor sensations associated with the experience of a feeling of calm or comforting sensations (Piotr Gruska, personal communication; or see for example, Chooi, White, Tan, Dowling, & Cyna, 2013). Future work should explore whether the assessment of pain is experienced as contradicting the message of pain acceptance.

Limitations of this pilot research include our small sample size, short-term follow-up, and lack of a control arm. Further, despite the measure of pain distress, including measurement of the fear of pain or anxiety sensitivity would have strengthened the conceptual model and should be included in future iterations of this work. Future work needs to compare this intervention to an active control arm and to examine the stability of these findings over time. It is certainly premature to claim that any changes reported in this pilot investigation are the result of the intervention itself rather than nonspecific factors such as attention or placebo related factors by virtue of receiving a treatment for pain.

In summary, this playful intervention, with its intention to teach young children about the meaning of bodily sensations, was successful in reducing pain, pain distress, interference due to pain, and negative affect. Helping children to be “FBI agents-Feeling and Body Investigators” may be a viable strategy to prevent future disorders that arise from sensitivity and fear-based reactions to bodily sensations.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We pilot an acceptance-based interoceptive exposure treatment for children with abdominal pain.

Young children are first learning to discriminate the meaning of bodily sensations.

Children learn to focus on and decode somatic signals, a departure from CBT treatments that divert attention from pain.

Results demonstrate medium to large effect sizes on intervention outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: All phases of the study were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21-MH-097959)

Abbreviations

- FBI

Feeling and Body Investigator

- FAP

functional abdominal pain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest: The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical trial registration: NCT02075437

Contributors’ Statements

Nancy Zucker was responsible for the design of the intervention, the design and implementation of the intervention, and oversaw all aspects of study implementation

Helen Egger oversaw the diagnosis of early childhood psychopathology and the design and implementation of assessment batteries

Hannah Hopkins, Kristen Caldwell, and Adam Kiridly were responsible for recruitment and conducting diagnostic interviews and lab assessments along with data management

Samuel Marsan assisted with data management

Emeran Mayer informed our model of visceral hypersensitivity

Michelle Craske provided guidance on mechanisms of change in interoceptive exposure treatments in the context of anxiety

Gary Maslow served as the study pediatrician to help monitor the safety of participants

Nandini Datta was the artist responsible for drawing all study characters

Christian Mauro served as a study therapist and contributed to the design of the intervention

Ryan Wagner is responsible for statistical analysis

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study began recruitment under the guidelines of the Rome III committee. Since treatment inception, the Rome IV guidelines have been produced for which Functional Abdominal Pain- Not Otherwise Specified is the appropriate term to describe children for whom abdominal pain is not better explained by another medical condition; there is insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, or abdominal migraine; and episodic pain occurs for at least four months, and is not solely during physiologic events such as eating or menses. This definition allows for the co-occurrence of a G.I. disorder if pain experience is in excess of what would be expected from the disorder. Children enrolled in the study meet criteria for both Rome III and Rome IV criteria.

References

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality Rates in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating Disorders A Meta-analysis of 36 Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:724–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. MEASURING EMOTION - THE SELF-ASSESSMENT MANNEQUIN AND THE SEMANTIC DIFFERENTIAL. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, Altman S, Lucas A, Birmaher B, Di Lorenzo C, Iyengar S, Brent DA. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:817–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo JV, Di Lorenzo C, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Colborn DK, Gartner JC, Jr, Gaffney P, Kocoshis S, Brent D. Adult outcomes of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain: do they just grow out of it? Pediatrics. 2001;108:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo JV, Gilchrist RH. Psychiatric comorbidity and functional abdominal pain. Pediatric Annals. 2009;38:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chooi CS, White AM, Tan SG, Dowling K, Cyna AM. Pain vs comfort scores after Caesarean section: a randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:780–787. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chordas C, Manley P, Modest AM, Chen B, Liptak C, Recklitis CJ. Screening for Pain in Pediatric Brain Tumor Survivors Using the Pain Thermometer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2013;30:249–259. doi: 10.1177/1043454213493507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MF, Mortensen O. Long-term prognosis in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1975;50:110–114. doi: 10.1136/adc.50.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez G, Van Damme S, Eccleston C. Hypervigilance to pain: An experimental and clinical analysis. Pain. 2005;116:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duits P, Hofmeijer-Sevink MK, Engelhard IM, Baas JMP, Ehrismann WAM, Cath DC. Threat expectancy bias and treatment outcome in patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2016;52:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams ACD, Lewandowski A, Morley S, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;85 [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Romeo RD, Andersen SL. Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: a window into a neural systems model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvie DS, Moseley GL, Hillier SL, Meulders A. Classical conditioning differences associated with chronic pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.02.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Spratt KF, Garand L. Evaluation of the Iowa Pain Thermometer and other selected pain intensity scales in younger and older adult cohorts using controlled clinical pain: A preliminary study. Pain Medicine. 2007;8:585–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietanen JK, Glerean E, Hari R, Nummenmaa L. Bodily maps of emotions across child development. Dev Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1111/desc.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, Maglione MA. Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes LS, Clark J, Colclough JA, Dale E, McMillan D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain: A systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Clin J Pain. 2016 doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE, Gross HE, Stucky BD, Thissen D, DeWitt EM, Lai JS, Amtmann D, Khastou L, Varni JW, DeWalt DA. Development of six PROMIS pediatrics proxy-report item banks. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:415–424. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY, Kim JH, Lee JU, Kim YM, Lee JA, Yoon NM, Hwang BY, Kim KJ, Lee HM, Kim B, Kim J. Temporal Changes in Pain and Sensory Threshold of Geriatric Patients after Moist Heat Treatment. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2011;23:797–801. [Google Scholar]

- Korterink J, Devanarayana NM, Rajindrajith S, Vlieger A, Benninga MA. Childhood functional abdominal pain: mechanisms and management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2015;12:159–171. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JDG, Bentley G. OUTLINE OF A FEAR-AVOIDANCE MODEL OF EXAGGERATED PAIN PERCEPTION .1. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1983;21:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, Romano JM, Christie DL, Youssef N, DuPen MM, Feld AD, Ballard SA, Welsh EM, Jeffery RW, Young M, Coffey MJ, Whitehead WE. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Children With Functional Abdominal Pain and Their Parents Decreases Pain and Other Symptoms. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:946–956. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, Creed F. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Zucker NL, Kragel PA, Covington VE, LaBar KS. Adolescent development of insula-dependent interoceptive regulation. Dev Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1111/desc.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley KJ, Glaser D, Milla PJ. Consumerism in healthcare can be detrimental to child health: lessons from children with functional abdominal pain. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90:335–337. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.032524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Gebhart GF. BASIC AND CLINICAL ASPECTS OF VISCERAL HYPERALGESIA. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:271–293. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyrop KA, Palsson OS, Levy RL, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Turner MJ, Whitehead WE. Costs of health care for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional abdominal pain. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2007;26:237–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo TM. Enhancing daily functioning with exposure and acceptance strategies: an important stride in the development of psychological therapies for pediatric chronic pain. Pain. 2009;141:189–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos FC, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Ekselius L. Excess mortality, causes of death and prognostic factors in anorexia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:10–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR, Ringel Y, Kim HP, Dibonaventura MD, Carroll CF, Allen JK, Cook SF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD, Shaheen NJ. Burden of Gastrointestinal Disease in the United States: 2012 Update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-+. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani PG, Hotopf M, Sandhu B, Stein A, Team AS. The epidemiology of recurrent abdominal pain from 2 to 6 years of age: Results of a large, population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:46–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed V, Wittchen HU. DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: how specific are panic attacks? J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtel BP, Thoden WR. A PLACEBO-CONTROLLED MODEL FOR ASSAYING SYSTEMIC ANALGESICS IN CHILDREN. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1993;53:593–601. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simrén M, Tornblom H, Palsson OS, van Tilburg MA, Van Oudenhove L, Tack J, Whitehead WE. Visceral hypersensitivity is associated with GI symptom severity in functional GI disorders: consistent findings from five different patient cohorts. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger C, Eippert F, Finsterbusch J, Bingel U, Rose M, Buchel C. Attention modulates spinal cord responses to pain. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1019–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba S, Egger HL, Angold A. Diagnostic specificity and nonspecificity in the dimensions of preschool psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:1005–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson D, von Baeyer CL, Stinson JN, Sung L. A Systematic Review of Faces Scales for the Self-report of Pain Intensity in Children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1168–E1198. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter TR. Assessment Tools in Pediatric Chronic Pain: Reliability and Validity. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–332. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain. 2012;153:1144–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Leupoldt A, Rohde J, Beregova A, Thordsen-Sorensen I, zur Nieden J, Dahme B. Films for eliciting emotional states in children. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:606–609. doi: 10.3758/bf03193032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LJ, Herr KA, Booker SS, Dotson K, Key J, Poindexter N, Pyles G, Siler B, Packard A. Psychometric Evaluation of the Revised Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT-R) in a Sample of Diverse Cognitively Intact and Impaired Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Pain Management Nursing. 2015;16:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrom L, Berg-Nielsen TS, Angold A, Egger HL, Solheim E, Sveen TH. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:695–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker NL, Lewis G, Davila-Hernandez MI, Egger HL, Porges S. Changes in the vagel tone following interoceptive exposure in children with functional abdominal pain (Manuscript in preparation) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.