Here, we show that moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea is associated with longer telomeres, independent of age and cardiovascular risk factors, challenging the hypothesis that telomere shortening is a unidirectional process related to age/disease. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying telomere dynamics may identify targets for therapeutic intervention in cardiovascular aging/other chronic diseases.

Keywords: intermittent hypoxemia, obstructive sleep apnea, telomere length

Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with cardiometabolic diseases. Telomere shortening is linked to hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases. Because these conditions are highly prevalent in OSA, we hypothesized that telomere length (TL) would be reduced in OSA patients. We identified 106 OSA and 104 non-OSA subjects who underwent polysomnography evaluation. Quantitative PCR was used to measure telomere length in genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood samples. The association between OSA and TL was determined using unadjusted and adjusted linear models. There was no difference in TL between the OSA and non-OSA (control) group. However, we observed a J-shaped relationship between TL and OSA severity: the longest TL in moderate-to-severe OSA [4,918 ± 230 (SD) bp] and the shortest TL in mild OSA (4,735 ± 145 bp). Mean TL in moderate-to-severe OSA was significantly longer than in the control group after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and depression (β = 96.0, 95% confidence interval: 15.4–176.6, P = 0.020). In conclusion, moderate-to-severe OSA is associated with telomere lengthening. Our findings support the idea that changes in TL are not unidirectional processes, such that telomere shortening occurs with age and disease but may be prolonged in moderate-to-severe OSA.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Here, we show that moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea is associated with longer telomeres, independent of age and cardiovascular risk factors, challenging the hypothesis that telomere shortening is a unidirectional process related to age/disease. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying telomere dynamics may identify targets for therapeutic intervention in cardiovascular aging/other chronic diseases.

obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep breathing disorder that affects >20 million United States adults (53, 73). OSA is an independent risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases and is related to worse cardiovascular outcomes. OSA is often diagnosed with hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, stroke, and atrial fibrillation (13, 29, 43, 66). Cardiovascular diseases are characteristic of aging, and telomeres have been proposed as a marker of disease progression and cardiovascular aging (26, 33, 54, 56).

Telomeres are a repetitive DNA sequence (TTAGGG), which, along with telomere protein complexes, protect the ends of chromosomes from DNA damage, degradation, and fusion (18b, 51). Telomeres shorten with each cell cycle as a result of the incomplete replication of linear DNA (the end-replication problem). Thus, telomeres serve as a checkpoint where the cell cycle is arrested after telomeres reach a critical size. Cells then become senescent or undergo apoptosis (46, 50). Telomeres are therefore postulated to act as a biological clock, reflecting mitotic cell capacity and cumulative exposure to oxidative stress and other environmental stressors over a lifetime (35), and thus to be one of the molecular mechanisms explaining cellular aging.

Numerous studies have investigated the association between telomeres, cardiometabolic risk factors [such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, physical activity, etc. (31, 58, 70, 75)], and cardiovascular diseases [such as arteriosclerosis (19, 61, 71), ischemic heart disease (24, 32), coronary disease (49, 56), myocardial infarction (10, 18a), and stroke (1, 18a, 21)]. However, the findings are often inconsistent and conflicting showing negative, positive, or no association. Even less clear is the association between telomere length (TL) and OSA, likely because of complex interactions and mechanisms shared between OSA, cardiometabolic risk factors, and cardiovascular disease. Most studies have linked OSA with short telomeres (4, 9, 38, 59, 62, 67), whereas one study has shown telomere elongation (37). Increased oxidative stress and inflammation are among the proposed mechanisms linked to both elevated cardiovascular risk and telomere shortening in OSA (16, 20, 23, 35, 45, 52, 67a, 72). However, the mechanisms underlying telomere shortening have not been completely investigated or confirmed in all studies (4, 62). Importantly, not all studies used polysomnography to identify the presence or absence of OSA (59, 62).

In this cross-sectional exploratory study, we sought to compare TL between non-OSA and OSA groups and examine the association of sleep-related variables with telomere characteristics. We hypothesized that telomere shortening would be accelerated in OSA and thus potentially may be used as a biomarker to assess physiological stress related to OSA and/or disease progression. In this study, we present results that further address the complicated association between OSA and TL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

In this cross-sectional study, we pooled data collected for 210 subjects participating in sleep-related research studies conducted at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) between the years of 2000 and 2007 and for whom extracted DNA was available. All subjects had undergone polysomnography evaluation to confirm or exclude the presence of OSA. Subjects with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of <5 were classified as the control group. Subjects with an AHI of ≥5 were identified as patients with OSA. All OSA subjects were naive to treatment for their sleep disorder. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (IRB no. 1872-99), and each participant signed an informed consent form.

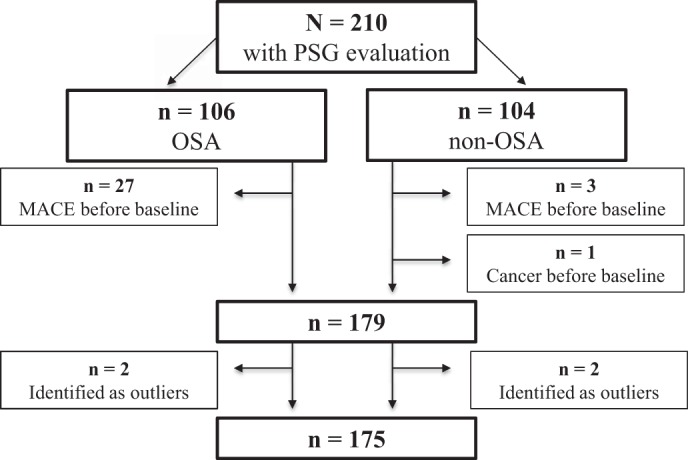

Participants with major adverse cardiac events defined as arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and/or heart failure (n = 30) and participants with any type of cancer diagnosed before baseline of sleep study (n = 1) were excluded (Fig. 1) as these conditions have been shown to be associated with TL (33, 63, 69). Demographics and individual and family medical history were collected for all study subjects. Hypertension was defined as self-reported or receiving antihypertensive treatment, dyslipidemia was defined as self-reported dyslipidemia/high lipid concentrations or receiving antihyperlipidemic treatment, smoking was defined as currently smoking, diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported or as receiving insulin treatment, and depression was defined as receiving medication from antidepressant drug class regardless of a prescription indication. Physical activity was reported as self-reported hours of leisure activity per week.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of subject inclusion in the study. MACE, major adverse cardiac events; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PSG, polysomnographic.

Polysomnography examination.

All participants underwent polysomnographic evaluation at the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research and Trials Unit or the Center for Sleep Medicine. Sleep was scored according to standard criteria (1a, 57). Apneas were defined as complete cessation of airflow lasting ≥10 s, whereas hypopneas were defined as reduction of airflow lasting ≥10 s accompanied by ≥4% decrease in oxygen saturation (). The AHI was computed as a total number of respiratory events per hour of sleep (n/h). Arousal index and mean and minimum were also determined. On the basis of the AHI, subjects were primarily classified as controls (non-OSA; AHI < 5) or OSA (AHI ≥ 5). In secondary analysis, OSA subjects were grouped as mild OSA (5 ≥ AHI < 15), moderate OSA (15 ≥ AHI < 30), and severe OSA (AHI ≥ 30).

Leukocyte TL measurements.

Peripheral blood samples were collected and stored at −80°C until DNA isolation. DNA was extracted within 1–2 days of blood collection using the PureGene method. Since the DNA extraction method may impact accurate measurements of TL, we ensured that DNA was extracted using the same method in all our study subjects (8, 18). TL was measured by Cawthon’s quantitative PCR (qPCR) method for determining relative TL (14). Briefly, TL qPCR uses two primers designed to hybridize to the telomeric hexamer repeats, and it determines the sample’s telomere-to-single copy gene ratio (T/S) compared with the T/S of a reference DNA sample. The β2-globin gene on chromosome 11 was used a single copy gene (S) in our study. TL qPCR measurements were performed on an Applied Biosystems Viia 7 machine. For each sample, TL qPCRs were performed in triplicate on a 384-well plate, and failed samples or those with a coefficient of variation of >5% were repeated up to two times. The interassay coefficient of variation was <1% for both telomere and single copy gene primers. Using a reference DNA sample for all TL qPCR runs, a standard curve was generated, which allowed for the reliable determination of TL as T/S (14). T/S was converted into base pairs using the following validated formula: base pairs = (T/S) × 1,470.8 + 7,674.5, as previously described by Boardman et al. (7).

Statistical analysis.

Before any analysis, the distribution of TL was examined, and subjects with TL below 3,842 bp or above 5,873 bp (>3 times the interquartile range above the third quartile or below the first quartile) were excluded as these were regarded as extreme outliers. Pairwise comparisons between OSA groups used a Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Pearson χ2-test for categorical variables. Linear regression evaluated the association between OSA severity and TL and between TL and sleep parameters. In the multivariate analysis, factors known to be associated with cardiovascular risk were included. The first adjusted model controlled for age alone; a second multivariable model controlled for traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; and the third model was additionally adjusted for depression. Information regarding P value and regression estimates (β) to explain the relationship between compared groups is provided. Regression assumptions (homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, and linearity of continuous adjustment factors) were evaluated; no significant violations were detected. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with JMP 10.0.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the R program (version 1.0.44).

RESULTS

After exclusion of subjects with major adverse cardiac events (n = 30) and cancer (n = 1) before baseline and extreme outliers (n = 4), the analytic sample included 101 subjects in the non-OSA (control) group and 74 subjects in the OSA group. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| n | Non-OSA | OSA | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere length, bp | 175 (101/74) | 4,802 (4,711−4,965) | 4,824 (4,709−5,009) | 0.774 |

| 4,846 ± 190 | 4,866 ± 224 | |||

| Age, yr | 175 (101/74) | 33 (27−43) | 47 (38−55) | <0.001 |

| 35 ± 11 | 48 ± 12 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 165 (93/72) | 122 (112−137) | 132 (124−143) | <0.001 |

| 124 ± 16 | 131 ± 15 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 165 (93/72) | 74 (66−80) | 76 (70−82) | 0.057 |

| 73 ± 10 | 76 ± 9 | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 158 (93/65) | 69 (62−76) | 72 (64−84) | 0.031 |

| 70 ± 11 | 74 ± 14 | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 174 (101/73) | 26 (23−28) | 32 (28−37) | <0.001 |

| 27 ± 5 | 32 ± 7 | |||

| Female sex, n (%) | 175 (101/74) | 30 (30) | 11 (15) | 0.022 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 175 (102/78) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 0.180 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 175 (101/74) | 5 (5) | 12 (16) | 0.013 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 175 (101/48) | 6 (6) | 11 (15) | 0.049 |

| Depression, n (%) | 175 (101/74) | 5 (5) | 10 (14) | 0.047 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 172 (100/72) | 9 (9) | 5 (7) | 0.627 |

| Physical activity, h/wk | 165 (96/69) | 3 (0−4) | 3 (0−5) | 0.922 |

| 2.7 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 2.7 | |||

| Parental cardiovascular disease history, n (%) | 175 (101/74) | 25 (25) | 32 (43) | 0.010 |

| Parental cancer history, n (%) | 175 (101/74) | 10 (10) | 8 (11) | 0.845 |

| Arousal index, n/h | 175 (101/74) | 14 (9−19) | 42 (27−63) | <0.001 |

| 15 ± 8 | 46 ± 22 | |||

| Apnea-hypopnea index, n/h | 175 (101/74) | 1 (0−1) | 29 (10−51) | <0.001 |

| 1 ± 1 | 34 ± 27 | |||

| Minimum blood O2 saturation % | 168 (98/70) | 91 (88−93) | 85 (77−88) | <0.001 |

| 90 ± 5 | 82 ± 9 | |||

| Mean blood O2 saturation, % | 170 (98/72) | 97 (96−98) | 94 (93−95) | <0.001 |

| 96 ± 2 | 94 ± 3 |

Values are medians (25th−75th percentile) and means ± SD or percentages of number of subjects [n (%)] for each group; n refers to subjects with available data [number of subjects without obstructive sleep apnea (non-OSA)/number of subjects with OSA]. Hypertension was defined as self-reported or receiving antihypertensive treatment, dyslipidemia was defined as self-reported dyslipidemia/high lipid concentrations or receiving antihyperlipidemic treatment, smoking was defined as currently smoking, diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported or as receiving insulin treatment, and depression was defined as receiving medication from antidepressant drug class regardless of a prescription indication. OSA was defined on the basis of an apnea-hypopnea index ≥5. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2-test.

Compared with the non-OSA group, the OSA group was significantly older (P < 0.001) and had higher body mass index (P < 0.001), systolic blood pressure (P = 0.013), and heart rate (P = 0.031) but not diastolic blood pressure (P = 0.057). There were also significantly more men than women, with a higher percentage of women in the non-OSA group than in the OSA group (P = 0.022). The OSA group was also characterized by a higher rate of dyslipidemia (P = 0.013), hypertension (P = 0.049), and depression (P = 0.047); however, there was no difference in smoking status (P = 0.627), diabetes (P = 0.18), or leisure physical activity (P = 0.922). The OSA group reported a higher rate of parental history of cardiovascular disease (P = 0.01), but there was no difference in the rate of parental history of cancer between groups (P = 0.845). As anticipated, the OSA group had a significantly higher arousal index, AHI, and mean and minimum (P < 0.001).

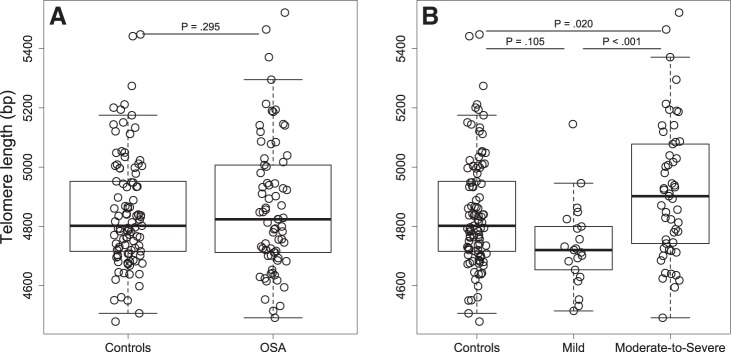

Comparison of TL between OSA and non-OSA groups showed no statistical difference between groups (P = 0.774). Adjusting for age and additionally for sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and depression did not change this result (P = 0.536 and P = 0.295, respectively; Fig. 2A). We found no association between parental history of cancer or cardiovascular disease, physical activity, TL, and OSA status. Subjects receiving antidepressants tended to have shorter telomeres than control subjects (regardless of OSA status): 4,789 ± 167 versus 4,861 ± 207 bp (means ± SD, P = 0.160).

Fig. 2.

Telomere length according to obstructive sleep apnea status (A) and severity (B). Boxes represent interquartile range (the third quartile minus the first quartile); whiskers are drawn to the farthest point within 1.5× interquartile range from the box. Horizontal lines indicate medians. P values for comparisons between groups were obtained from models adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and depression.

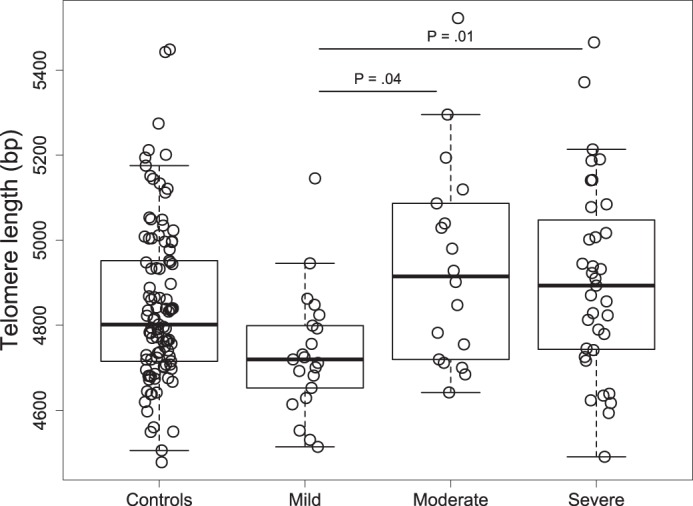

We explored further whether OSA severity, based on the AHI metric, was associated with TL. We divided OSA subjects into three groups: mild OSA (n = 21), moderate OSA (n = 18), and severe OSA (n = 35). We showed that severe OSA and moderate OSA subjects had longer TL than mild OSA subjects (4,906 ± 227 vs. 4,735 ± 145 bp, P = 0.01, and 4,941 ± 241 vs. 4,735 ± 145 bp, P = 0.04, respectively, means ± SD) after adjustment for age. There was no difference in TL between moderate OSA and severe OSA (P = 0.987) and between the control group and any given OSA severity group (Fig. A1). For further analysis, we merged moderate OSA and severe OSA groups into the moderate-to-severe OSA group as there was no difference in TL between these two groups and, clinically, AHI ≥ 15 is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk (66). Table A1 in the appendix shows the subject characteristics across OSA categories.

Linear models used to test the difference between groups showed a J-shaped association between TL and OSA severity: mean TL in the mild OSA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (non-OSA, P = 0.020) and moderate-to-severe OSA group (P < 0.001); the moderate-to-severe OSA group had longer TL than the control group (P = 0.034), even though this group was significantly older than the control group. Adjustment for age (model 1) did not change these main findings; in the model with additional adjustment for recognized cardiovascular risk factors such as sex, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (model 2) and in the model additionally adjusted for depression (model 3), the difference in TL between mild OSA and moderate-to-severe OSA and between moderate-to-severe OSA and controls remained statistically significant (Table 2 and Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Association of telomere length with obstructive sleep apnea categories

| β | −95% Confidence Interval | +95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model (n = 175) | 0.002 | |||

| Mild vs. control | −111.7 | −203.6 | −19.8 | 0.020 |

| Moderate to severe vs. mild | 183.6 | 83.2 | 284.0 | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe vs. control | 71.9 | 5.9 | 137.9 | 0.034 |

| Adjusted model 1 (n = 175) | 0.005 | |||

| Mild vs. control | −107.3 | −204.0 | −10.5 | 0.031 |

| Moderate to severe vs. mild | 184.7 | 83.9 | 285.5 | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe vs. control | 77.4 | 4.4 | 150.4 | 0.039 |

| Adjusted model 2 (n = 174) | 0.046 | |||

| Mild vs. control | −91.2 | −194.1 | 11.8 | 0.085 |

| Moderate to severe vs. mild | 182.5 | 78.5 | 286.2 | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe vs. control | 91.4 | 11.5 | 171.2 | 0.026 |

| Adjusted model 3 (n = 174) | 0.046 | |||

| Mild vs. control | −85.9 | −189.8 | 18.0 | 0.105 |

| Moderate to severe vs. mild | 181.9 | 77.3 | 286.5 | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe vs. control | 96.0 | 15.4 | 176.6 | 0.020 |

β, β-coefficient. Model 1 was adjusted for age. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Model 3 was adjusted additionally for depression. P values for comparisons between groups were obtained from the generalized linear model.

We explored the association between TL and sleep parameters in an unadjusted model, a model adjusted for age (model 1), and a model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (model 2; Table A2 in the appendix). We found a positive association between AHI and TL in the fully adjusted model for the entire group (β = 1.5 ± 0.7, means ± SE, P = 0.041). However, we found no association between TL and arousal index, minimum and mean in the whole group or in the OSA group only (Table A2).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that OSA is not associated with telomere shortening. Importantly, elongation of telomeres was observed in patients with moderate-to-severe OSA. Additionally, we found a positive association between the AHI and TL for the entire group.

In contrast to our initial hypothesis that TL would be reduced in OSA, we found no difference in TL between the OSA and control (non-OSA) groups. However, exploratory analysis considering OSA severity revealed a J-shaped relationship between TL and OSA: the shortest telomeres in mild OSA and the longest in moderate-to-severe OSA. Importantly, TL of the moderate-to-severe OSA group was even longer than in the control group. This finding is of particular interest as the moderate-to-severe OSA group was significantly older than the control group and would be expected to have shorter TL (47). The difference in TL between moderate-to-severe OSA and controls was independent of age and traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as sex, body mass index, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and depression.

Our results add to the recent studies that have examined TL in health and disease. At the inception of this study, use of polysomnography to evaluate OSA and TL in relatively larger study samples was lacking, and discrepancies in sleep-related factors associated with altered TL existed (4, 9, 38, 67). Since then, several recent well-controlled studies have shown telomere shortening that is more predominant in subjects with moderate and severe OSA (9, 38, 67). Similar to these studies, we showed shorter TL in participants with mild OSA. However, in contrast to these studies, OSA patients with moderate-to-severe OSA in our study showed telomere lengthening. Elongation of TL in moderate-to-severe OSA has been previously demonstrated in the pediatric population (37). The concept of telomere lengthening in patients with moderate-to-severe OSA is not unlikely and needs further investigation. The AHI and oxygen desaturation have been proposed as potential mechanisms underlying telomere shortening in recently published studies (9, 38, 67). In our study, we observed a positive association between AHI and TL but no association with the arousal index or oxygen desaturation. We speculate that a possible effect of OSA (potentially through the downstream cascade of events related to intermittent hypoxemia, blood oxygen desaturation, and/or sleep fragmentation) on TL may be through increased telomerase expression and/or activity. Most human somatic cells present low telomerase expression/activity or are telomerase negative and thus experience telomere shortening with each cell division (15). However, it has been shown that telomerase activity can be modulated by environmental signals such as oxidative stress and inflammation (5, 15, 28). Also, it has been observed that hypoxia upregulated telomerase activity in endothelial cells, and TL seemed to be regulated by a balance between telomere attrition by hypoxia and telomere elongation by enhanced telomerase activity (2, 30). Furthermore, there is evidence that human telomerase can be induced to selectively extend short telomeres by exposure to low pH (27). This finding is of particular interest because acidity is characteristic of both the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and respiratory acidosis in OSA (40). Indeed, telomere lengthening via increased telomerase activity is a hallmark to retain cellular mitotic capacity (15) and several types of cancer (17, 64, 65, 76). Notably, several recent studies have shown an increased cancer risk in OSA patients (11, 12, 39, 41). From this point of view, our results may provide a novel perspective on the biological mechanisms by which OSA may increase the risk of cancer. In the context of the hypothesis that OSA may upregulate telomerase expression/activity, a differential cell response should also be considered. Telomerase activity levels are different in low- and high-turnover cells (15). Therefore, cells with different turnover rates may exhibit differential responses and may manifest opposite effects on TL. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that mean TL measured in leukocytes is equivalent to TL in other tissue within the same individual. Future studies are needed to elucidate mechanisms regulating telomere dynamics in OSA.

The nonlinear association of TL with disease progression and/or severity is not unique to our study. The German Chronic Kidney Disease Study demonstrated a U-shaped association between TL and chronic kidney disease duration as opposed to an expected progressive TL shortening with disease duration (43). The authors speculated that chronic oxidative stress and inflammation might activate protective mechanisms leading to telomere lengthening in chronic kidney disease. Upregulated antioxidative mechanisms have been also implicated in OSA (34). It has been also shown that chronic exposure to intermittent hypoxemia may stimulate beneficial physiological effects on the cardiovascular system, an adaptive phenomenon known as intermittent hypoxemia-mediated ischemic preconditioning (44, 48).

Our understanding of telomere dynamics is constantly evolving with growing evidence supporting the concept that changes in TL are not unidirectional processes such that telomere shortening always occurs with age and disease. Several studies have demonstrated both a stable and increased TL over time (3, 36, 68). One longitudinal study showed bidirectional changes in TL in patients with coronary artery disease: TL maintenance was observed in 32% of subjects and TL lengthening in 23% of subjects (25). Importantly, individuals with shorter telomeres maintained or increased their length, whereas those with the longest telomeres experienced a shortening. These studies suggest a threshold effect such that telomere lengthening may be initiated when a critical TL is reached (6).

Some limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, this is a cross-sectional study, and we cannot make any inferences or casual statements about mechanisms underlying TL dynamics in OSA; we had no access to blood samples to test for oxidative stress, antioxidant response markers, or telomerase activity. Second, we had no information regarding OSA onset/duration. This may bias our results, as it is conceivable that the observed telomere dynamics may be linked not only to OSA severity but also to exposure duration. Third, although we have adjusted models for traditional confounders relevant to cardiovascular risk, we cannot exclude that other variables related to treatment and lifestyle may affect TL. Specifically, we had no information regarding socioeconomic status or validated assessment of physical activity, anxiety, and depression: we relied on information from past studies, which were not designed primarily to test the association between TL and sleep breathing disorders. Fourth, four subjects were identified as outliers and excluded from analysis. However, it should be noted that these outliers represent 2% of the study population and may represent phenomena or statistical populations that are distinct from those under study. Although the significance of these outliers remains uncertain, it can be assumed that individual TL variability is influenced by unique factors related to genetic background, environment, or other variables that were not included in this study (60). Finally, the relatively modest sample size of each OSA group imposes further limitations on our study. Although we have identified statistically significant associations between OSA severity and TL, wide confidence intervals indicate variability that may reflect individual differences in health, disease, and environmental exposure as described above. Our findings need to be confirmed in larger populations. Indeed, a future confirmation study is needed using data from this study to estimate the power and sample size. Nevertheless, our study has generated new hypotheses and identified areas for further research.

In summary, this exploratory study demonstrated complex telomere dynamics in OSA where mild OSA is related to telomere shortening but moderate-to-severe OSA is associated with telomere lengthening, independent of age. Our findings challenge the hypothesis that telomere shortening is a unidirectional process related to age and age-related disease and highlight several new hypotheses. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying telomere dynamics may identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention in cardiovascular aging and other chronic diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-65176, HL-114676, and HL-114024 (to V. K. Somers and P. Singh) and CA-2024013 (to L. A. Boardman), American Heart Association Grants 16POST30260005 (to K. Polonis), 16POST27210011 (to C. Becari), and 16SDG27250156 (to N. Covassin), and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development Brazil Grant 203802/2014-4 (to C. Becari).

DISCLOSURES

V. K. Somers: grant support from Philips Respironics Foundation (gift to Mayo Foundation); consultant for Respicardia, ResMed, Sorin Incorporated, U-Health, GlaxoSmithKline, Rhonda Grey, Dane Garvin, Philips Respironics, Biosense Webster; working with Mayo Health Solutions and their industry partners on intellectual property related to sleep and cardiovascular disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.P., V.K.S., B.R.D., L.A.B., and P.S. conceived and designed research; B.R.D. and R.A.J. performed experiments; K.P. and P.J.S. analyzed data; K.P., V.K.S., C.B., N.C., and P.S. interpreted results of experiments; K.P. prepared figures; K.P. drafted manuscript; K.P., V.K.S., C.B., N.C., P.J.S., B.R.D., K.N., L.A.B., and P.S. edited and revised manuscript; K.P., V.K.S., C.B., N.C., P.J.S., B.R.D., R.A.J., K.N., L.A.B., and P.S. approved final version of manuscript.

APPENDIX

Box plots of TL across OSA severity groups are shown in Fig. A1. Characteristics of the study population across categories of OSA severity are shown in Table A1, and the association between TL and sleep parameters is shown in Table A2.

Fig. A1.

Box plots of telomere length across obstructive sleep apnea severity groups. P values for comparisons between groups were obtained from the age-adjusted model. Boxes represent interquartile range (the third quartile minus the first quartile); whiskers are drawn to the farthest point within 1.5× interquartile range from the box. Horizontal lines indicate medians.

Table A1.

Characteristics of the study population across categories of OSA severity

| n | Control (non-OSA) | Mild OSA | Moderate-to-Severe OSA | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telomere length, bp | 175 (101/21/53) | 4,802 (4,711−4,965)a | 4,719 (4,641−4,812)b | 4,902 (4,733−5,081)a | 0.002 |

| 4,846 ± 190 | 4,735 ± 145 | 4,918 ± 230 | |||

| Age, yr | 175 (101/21/53) | 33 (27−43)a | 45 (37−51)b | 48 (39−57)b | <0.001 |

| 35 ± 11 | 45 ± 10 | 47 ± 13 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 165 (93/20/52) | 122 (112−137)a | 124 (114−139)b | 134 (129−143)b | <0.001 |

| 124 ± 16 | 124 ± 18 | 134 ± 13 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 165 (93/20/52) | 74 (66−80) | 75 (69−84) | 76 (71−82) | 0.152 |

| 73 ± 10 | 76 ± 11 | 76 ± 8 | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 158 (93/18/47) | 69 (62−76) | 74 (67−88) | 72 (64−83) | 0.079 |

| 70 ± 11 | 78 ± 18 | 74 ± 12 | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 174 (101/20/53) | 26 (23−28)a | 31 (25−39)b | 32 (29−36)b | <0.001 |

| 27 ± 5 | 32 ± 8 | 33 ± 6 | |||

| Female sex, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 30 (30) | 5 (24) | 6 (11) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 1 (1) | 2 (10) | 1 (2) | 0.06 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 5 (5) | 4 (19) | 8 (15) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 7 (7) | 3 (14) | 11 (21) | 0.040 |

| Depression, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 5 (5) | 3 (14) | 7 (13) | 0.137 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 9 (9) | 1 (5) | 4 (8) | 0.846 |

| Physical activity, h/wk | 165 (96/17/52) | 3 (0−4) | 4 (0−5) | 2.5 (0−5) | 0.928 |

| 2.7 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 2.4 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | |||

| Parental cardiovascular disease history, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 25 (25) | 6 (29) | 26 (49) | 0.010 |

| Parental cancer history, n (%) | 175 (101/21/53) | 10 (10) | 2 (10) | 6 (11) | 0.956 |

| Arousal index, n/h | 175 (101/21/53) | 14 (9−19)a | 27 (20−41)b | 47 (30−69)c | <0.001 |

| 15 ± 8 | 33 ± 18 | 51 ± 22 | |||

| Apnea-hypopnea index, n/h | 175 (101/21/53) | 1 (0−1)a | 6 (5−9)b | 40 (23−58)c | <0.001 |

| 1 ± 1 | 7 ± 2 | 44 ± 26 | |||

| Minimum blood O2 saturation, % | 168 (98/20/50) | 91 (88−93)a | 89 (84−90)b | 83 (75−86)c | <0.001 |

| 90 ± 5 | 88 ± 4 | 80 ± 10 | |||

| Mean blood O2 saturation, % | 170 (98/20/52) | 97 (96−98)a | 95 (92−95)b | 94 (92−95)c | <0.001 |

| 96 ± 2 | 95 ± 3 | 93 ± 3 |

Values are medians (25th–75th percentile) and means ± SD or percentages of numbers of subjects [n (%)] for each group; n refers to those subjects with available data [number of control subjects/number of subjects with mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)/number of subjects with moderate-to-severe OSA]. Hypertension was defined as self-reported or receiving antihypertensive treatment, dyslipidemia was defined as self-reported dyslipidemia/high lipid concentrations or receiving antihyperlipidemic treatment, smoking was defined as currently smoking, diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported or as receiving insulin treatment, and depression was defined as receiving medication from antidepressant drug class regardless of a prescription indication. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2-test.

Levels not connected by same letter are significantly different at P < 0.05 (nonparametric comparisons for each pair using the Wilcoxon method).

Table A2.

Association between telomere length and sleep parameters

| Unadjusted |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | OSA | All | OSA | All | OSA | |

| Apnea-hypopnea index | ||||||

| n/h | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 1.0 |

| P value | 0.077 | 0.091 | 0.069 | 0.097 | 0.041 | 0.151 |

| Arousal index | ||||||

| n/h | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 1.4 |

| P value | 0.195 | 0.328 | 0.167 | 0.346 | 0.096 | 0.538 |

| Minimum blood O2 saturation | ||||||

| % | −0.3 ± 2.0 | −0.8 ± 3.0 | 0.03 ± 2.1 | −0.7 ± 2.3 | −0.5 ± 2.4 | −0.3 ± 3.5 |

| P value | 0.875 | 0.804 | 0.988 | 0.823 | 0.841 | 0.934 |

| Mean blood O2 saturation | ||||||

| % | 1.5 ± 6.1 | 8.0 ± 9.4 | 2.3 ± 6.4 | 8.0 ± 9.5 | 1.5 ± 6.8 | 4.9 ± 9.9 |

| P value | 0.803 | 0.400 | 0.717 | 0.401 | 0.823 | 0.627 |

Values are β-coefficients ± SE with the corresponding P value. OSA, obstructive sleep apnea. Model 1 was adjusted for age. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allende M, Molina E, González-Porras JR, Toledo E, Lecumberri R, Hermida J. Short leukocyte telomere length is associated with cardioembolic stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 47: 863–865, 2016. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.American Sleep Disorders Association EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep 15: 173–184, 1992. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson CJ, Hoare SF, Ashcroft M, Bilsland AE, Keith WN. Hypoxic regulation of telomerase gene expression by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Oncogene 25: 61–69, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aviv A, Chen W, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Brimacombe M, Cao X, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Leukocyte telomere dynamics: longitudinal findings among young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 169: 323–329, 2009. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barceló A, Piérola J, López-Escribano H, de la Peña M, Soriano JB, Alonso-Fernández A, Ladaria A, Agustí A. Telomere shortening in sleep apnea syndrome. Respir Med 104: 1225–1229, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beery AK, Lin J, Biddle JS, Francis DD, Blackburn EH, Epel ES. Chronic stress elevates telomerase activity in rats. Biol Lett 8: 1063–1066, 2012. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi A, Shore D. How telomerase reaches its end: mechanism of telomerase regulation by the telomeric complex. Mol Cell 31: 153–165, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boardman LA, Johnson RA, Viker KB, Hafner KA, Jenkins RB, Riegert-Johnson DL, Smyrk TC, Litzelman K, Seo S, Gangnon RE, Engelman CD, Rider DN, Vanderboom RJ, Thibodeau SN, Petersen GM, Skinner HG. Correlation of chromosomal instability, telomere length and telomere maintenance in microsatellite stable rectal cancer: a molecular subclass of rectal cancer. PLoS One 8: e80015, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boardman LA, Skinner HG, Litzelman K. Telomere length varies by DNA extraction method: implications for epidemiologic research−response. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23: 1131–1131, 2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer L, Audureau E, Margarit L, Marcos E, Bizard E, Le Corvoisier P, Macquin-Mavier I, Derumeaux G, Damy T, Drouot X, Covali-Noroc A, Boczkowski J, Bastuji-Garin S, Adnot S. Telomere shortening in middle-aged men with sleep-disordered breathing. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13: 1136–1143, 2016. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201510-718OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brouilette S, Singh RK, Thompson JR, Goodall AH, Samani NJ. White cell telomere length and risk of premature myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 842–846, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000067426.96344.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos-Rodriguez F, Martinez-Garcia MA, Martinez M, Duran-Cantolla J, Peña ML, Masdeu MJ, Gonzalez M, Campo F, Gallego I, Marin JM, Barbe F, Montserrat JM, Farre R; Spanish Sleep Network . Association between obstructive sleep apnea and cancer incidence in a large multicenter Spanish cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 99–105, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1671OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao J, Feng J, Li L, Chen B. Obstructive sleep apnea promotes cancer development and progression: a concise review. Sleep Breath 19: 453–457, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caples SM, Garcia-Touchard A, Somers VK. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular risk. Sleep 30: 291–303, 2007. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e47, 2002. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cong Y-S, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66: 407–425, 2002. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.407-425.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correia-Melo C, Hewitt G, Passos JF. Telomeres, oxidative stress and inflammatory factors: partners in cellular senescence? Longev Healthspan 3: 1, 2014. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui Y, Cai Q, Qu S, Chow WH, Wen W, Xiang YB, Wu J, Rothman N, Yang G, Shu XO, Gao YT, Zheng W. Association of leukocyte telomere length with colorectal cancer risk: nested case-control findings from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21: 1807–1813, 2012. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham JM, Johnson RA, Litzelman K, Skinner HG, Seo S, Engelman CD, Vanderboom RJ, Kimmel GW, Gangnon RE, Riegert-Johnson DL, Baron JA, Potter JD, Haile R, Buchanan DD, Jenkins MA, Rider DN, Thibodeau SN, Petersen GM, Boardman LA. Telomere length varies by DNA extraction method: implications for epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22: 2047–2054, 2013. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.D’Mello MJ, Ross SA, Briel M, Anand SS, Gerstein H, Paré G. Association between shortened leukocyte telomere length and cardiometabolic outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 82–90, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b.de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19: 2100–2110, 2005. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Vusser K, Pieters N, Janssen B, Lerut E, Kuypers D, Jochmans I, Monbaliu D, Pirenne J, Nawrot T, Naesens M. Telomere length, cardiovascular risk and arteriosclerosis in human kidneys: an observational cohort study. Aging (Albany NY) 7: 766–775, 2015. doi: 10.18632/aging.100814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewan NA, Nieto FJ, Somers VK. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA: implications for comorbidities. Chest 147: 266–274, 2015. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding H, Chen C, Shaffer JR, Liu L, Xu Y, Wang X, Hui R, Wang DW. Telomere length and risk of stroke in Chinese. Stroke 43: 658–663, 2012. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.637207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisele HJ, Markart P, Schulz R. Obstructive sleep apnea, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular disease: evidence from human studies. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015: 608438, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/608438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellehoj H, Bendix L, Osler M. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of 1,397 Danish men and women. Cardiology 133: 173–177, 2016. doi: 10.1159/000441819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farzaneh-Far R, Lin J, Epel E, Lapham K, Blackburn E, Whooley MA. Telomere length trajectory and its determinants in persons with coronary artery disease: longitudinal findings from the heart and soul study. PLoS One 5: e8612, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fyhrquist F, Saijonmaa O, Strandberg T. The roles of senescence and telomere shortening in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 10: 274–283, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge Y, Wu S, Xue Y, Tao J, Li F, Chen Y, Liu H, Ma W, Huang J, Zhao Y. Preferential extension of short telomeres induced by low extracellular pH. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 8086–8096, 2016. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gizard F, Heywood EB, Findeisen HM, Zhao Y, Jones KL, Cudejko C, Post GR, Staels B, Bruemmer D. Telomerase activation in atherosclerosis and induction of telomerase reverse transcriptase expression by inflammatory stimuli in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 245–252, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.219808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzaga C, Bertolami A, Bertolami M, Amodeo C, Calhoun D. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. J Hum Hypertens 29: 705–712, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan JZ, Guan WP, Maeda T, Makino N. Different levels of hypoxia regulate telomere length and telomerase activity. Aging Clin Exp Res 24: 213–217, 2012. doi: 10.1007/BF03325250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guzzardi MA, Iozzo P, Salonen M, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Rate of telomere shortening and metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors: a longitudinal study in the 1934–44 Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Ann Med 47: 499–505, 2015. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1074718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haver VG, Mateo Leach I, Kjekshus J, Fox JC, Wedel H, Wikstrand J, de Boer RA, van Gilst WH, McMurray JJV, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Harst P. Telomere length and outcomes in ischaemic heart failure: data from the COntrolled ROsuvastatin multiNAtional Trial in Heart Failure (CORONA). Eur J Heart Fail 17: 313–319, 2015. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haycock PC, Heydon EE, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Thompson A, Willeit P. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 349: g4227, 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann MS, Singh P, Wolk R, Romero-Corral A, Raghavakaimal S, Somers VK. Microarray studies of genomic oxidative stress and cell cycle responses in obstructive sleep apnea. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 661–669, 2007. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houben JM, Moonen HJ, van Schooten FJ, Hageman GJ. Telomere length assessment: biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med 44: 235–246, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huzen J, Wong LS, van Veldhuisen DJ, Samani NJ, Zwinderman AH, Codd V, Cawthon RM, Benus GF, van der Horst IC, Navis G, Bakker SJ, Gansevoort RT, de Jong PE, Hillege HL, van Gilst WH, de Boer RA, van der Harst P. Telomere length loss due to smoking and metabolic traits. J Intern Med 275: 155–163, 2014. doi: 10.1111/joim.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Lee S, Bhattacharjee R, Khalyfa A, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Leukocyte telomere length and plasma catestatin and myeloid-related protein 8/14 concentrations in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 138: 91–99, 2010. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KS, Kwak JW, Lim SJ, Park YK, Yang HS, Kim HJ. Oxidative stress-induced telomere length shortening of circulating leukocyte in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Aging Dis 7: 604–613, 2016. doi: 10.14336/AD.2016.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim R, Kapur VK. Emerging from the shadows: a possible link between sleep apnea and cancer. J Clin Sleep Med 10: 363–364, 2014. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, Konety SH. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation 133: 1104–1114, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kukwa W, Migacz E, Druc K, Grzesiuk E, Czarnecka AM. Obstructive sleep apnea and cancer: effects of intermittent hypoxia? Future Oncol 11: 3285−3298, 2015. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lattimore J-DL, Celermajer DS, Wilcox I. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 1429–1437, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavie L, Lavie P. Ischemic preconditioning as a possible explanation for the age decline relative mortality in sleep apnea. Med Hypotheses 66: 1069–1073, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavie L, Lavie P. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in OSAHS: the oxidative stress link. Eur Respir J 33: 1467–1484, 2009. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00086608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy MZ, Allsopp RC, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. J Mol Biol 225: 951–960, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mather KA, Jorm AF, Parslow RA, Christensen H. Is telomere length a biomarker of aging? A review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66: 202–213, 2011. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Navarrete-Opazo A, Mitchell GS. Therapeutic potential of intermittent hypoxia: a matter of dose. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307: R1181–R1197, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00208.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogami M, Ikura Y, Ohsawa M, Matsuo T, Kayo S, Yoshimi N, Hai E, Shirai N, Ehara S, Komatsu R, Naruko T, Ueda M. Telomere shortening in human coronary artery diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 546–550, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000117200.46938.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olovnikov AM. Telomeres, telomerase, and aging: origin of the theory. Exp Gerontol 31: 443–448, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(96)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palm W, de Lange T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet 42: 301–334, 2008. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pialoux V, Hanly PJ, Foster GE, Brugniaux JV, Beaudin AE, Hartmann SE, Pun M, Duggan CT, Poulin MJ. Effects of exposure to intermittent hypoxia on oxidative stress and acute hypoxic ventilatory response in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 1002–1009, 2009. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0671OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 136–143, 2008. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raschenberger J, Kollerits B, Ritchie J, Lane B, Kalra PA, Ritz E, Kronenberg F. Association of relative telomere length with progression of chronic kidney disease in two cohorts: effect modification by smoking and diabetes. Sci Rep 5: 11887, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep11887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raschenberger J, Kollerits B, Titze S, Köttgen A, Bärthlein B, Ekici AB, Forer L, Schönherr S, Weissensteiner H, Haun M, Wanner C, Eckardt KU, Kronenberg F; GCKD Study Investigators . Do telomeres have a higher plasticity than thought? Results from the German Chronic Kidney Disease (GCKD) study as a high-risk population. Exp Gerontol 72: 162–166, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raschenberger J, Kollerits B, Titze S, Köttgen A, Bärthlein B, Ekici AB, Forer L, Schönherr S, Weissensteiner H, Haun M, Wanner C, Eckardt KU, Kronenberg F; GCKD Study Investigators . Association of relative telomere length with cardiovascular disease in a large chronic kidney disease cohort: the GCKD study. Atherosclerosis 242: 529–534, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Los Angeles, CA: Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, University of California, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rehkopf DH, Needham BL, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Zota AR, Wojcicki JM, Epel ES. Leukocyte telomere length in relation to 17 biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk: a cross-sectional study of US adults. PLoS Med 13: e1002188, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riestra P, Gebreab SY, Xu R, Khan RJ, Quarels R, Gibbons G, Davis SK. Obstructive sleep apnea risk and leukocyte telomere length in African Americans from the MH-GRID study. Sleep Breath 21: 751–757, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11325-016-1451-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rode L, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and mortality among 64,637 individuals from the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst 107: djv074, 2015. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Samani NJ, Boultby R, Butler R, Thompson JR, Goodall AH. Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis. Lancet 358: 472–473, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Savolainen K, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Lahti M, Räikkönen K. The history of sleep apnea is associated with shorter leukocyte telomere length: the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Sleep Med 15: 209–212, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.11.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serrano AL, Andrés V. Telomeres and cardiovascular disease: does size matter? Circ Res 94: 575–584, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122141.18795.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shay JW, Bacchetti S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur J Cancer 33: 787–791, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skinner HG, Gangnon RE, Litzelman K, Johnson RA, Chari ST, Petersen GM, Boardman LA. Telomere length and pancreatic cancer: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21: 2095–2100, 2012. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, Daniels S, Floras JS, Hunt CE, Olson LJ, Pickering TG, Russell R, Woo M, Young T; American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American College of Cardiology Foundation . Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation 118: 1080–1111, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tempaku PF, Mazzotti DR, Hirotsu C, Andersen ML, Xavier G, Maurya PK, Rizzo LB, Brietzke E, Belangero SI, Bittencourt L, Tufik S. The effect of the severity of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome on telomere length. Oncotarget 7: 69216–69224, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67a.von Zglinicki T. Oxidative stress shortens telomeres. Trends Biochem Sci 27: 339–344, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Telomere shortening unrelated to smoking, body weight, physical activity, and alcohol intake: 4,576 general population individuals with repeat measurements 10 years apart. PLoS Genet 10: e1004191, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wentzensen IM, Mirabello L, Pfeiffer RM, Savage SA. The association of telomere length and cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 1238–1250, 2011. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willeit P, Raschenberger J, Heydon EE, Tsimikas S, Haun M, Mayr A, Weger S, Witztum JL, Butterworth AS, Willeit J, Kronenberg F, Kiechl S. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: new prospective cohort study and literature-based meta-analysis. PLoS One 9: e112483, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willeit P, Willeit J, Brandstätter A, Ehrlenbach S, Mayr A, Gasperi A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Reindl M, Kronenberg F, Kiechl S. Cellular aging reflected by leukocyte telomere length predicts advanced atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1649–1656, 2010. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.205492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamauchi M, Nakano H, Maekawa J, Okamoto Y, Ohnishi Y, Suzuki T, Kimura H. Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 127: 1674–1679, 2005. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 1217–1239, 2002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao J, Miao K, Wang H, Ding H, Wang DW. Association between telomere length and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8: e79993, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu X, Han W, Xue W, Zou Y, Xie C, Du J, Jin G. The association between telomere length and cancer risk in population studies. Sci Rep 6: 22243, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep22243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]