Abstract

The house mouse (Mus musculus) provides a fascinating system for studying both the genomic basis of reproductive isolation, and the patterns of human-mediated dispersal. New Zealand has a complex history of mouse invasions, and the living descendants of these invaders have genetic ancestry from all three subspecies, although most are primarily descended from M. m. domesticus. We used the GigaMUGA genotyping array (approximately 135 000 loci) to describe the genomic ancestry of 161 mice, sampled from 34 locations from across New Zealand (and one Australian city—Sydney). Of these, two populations, one in the south of the South Island, and one on Chatham Island, showed complete mitochondrial lineage capture, featuring two different lineages of M. m. castaneus mitochondrial DNA but with only M. m. domesticus nuclear ancestry detectable. Mice in the northern and southern parts of the North Island had small traces (approx. 2–3%) of M. m. castaneus nuclear ancestry, and mice in the upper South Island had approximately 7–8% M. m. musculus nuclear ancestry including some Y-chromosomal ancestry—though no detectable M. m. musculus mitochondrial ancestry. This is the most thorough genomic study of introduced populations of house mice yet conducted, and will have relevance to studies of the isolation mechanisms separating subspecies of mice.

Keywords: Mus musculus, mitochondrial capture, subspecies hybridization, sterility, invasion, phylogeography

1. Introduction

The house mouse, Mus musculus, provides a powerful model system for understanding evolution, and is arguably the best mammalian model for studies of the genomic basis for reproductive isolation during the early stages of speciation. It includes at least three closely related subspecies with parapatric distributions: M. m. musculus found in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia, M. m. castaneus in Southeast Asia and India, and M. m. domesticus in western Europe, the Near East and northern Africa [1]. These three subspecies rapidly diverged in allopatry around 350 000 years ago [2–4], and evidence suggests that M. m. castaneus and M. m. musculus are more closely related to each other than either is to M. m. domesticus [5,6]. During the past 10 000 years, house mice have become commensal with humans, and, as stowaways with them, have become the most successful small mammal colonizers of new continents during the past few hundred years [7,8].

Regions of secondary contact and introgression may mark where mouse subspecies meet in nature. The best studied of these is a narrow hybrid zone between M. m. domesticus and M. m. musculus that stretches from Denmark to the Black Sea in central Europe [9–18]. This hybrid zone is young, with mice having colonized this area around 3000 years ago [19,20]. Hybridization in the wild between M. m. domesticus and M. m. castaneus is best known from one study of an introduced population in California [21] and one in New Zealand [22]. Within the native range, other possible domesticus/castaneus hybrid zones in Iran [23–25] and in Indonesia [26] have produced only preliminary results, because these regions are complex, supporting multiple (and potentially undescribed) subspecies [24], and because comprehensive nuclear loci have not been used to look at the levels of admixture across the genomes.

Hybrids between subspecies have been extensively studied in laboratory strains of mice, with data indicating that M. m. musculus and M. m. domesticus are largely reproductively isolated [27,28]. These studies have helped us to understand the genetics of speciation, particularly the genetic basis of hybrid male sterility [29–32], revealing an important role of the X chromosome in producing reproductive incompatibilities [33–39]. Studies of both wild and laboratory mice have also found that hybrid male sterility has a complex basis, involving many genes [31,32,37,40]. Laboratory crosses between M. m. domesticus and M. m. musculus led to the identification of Prdm9 on chromosome 17, the only gene at present known to contribute to hybrid sterility in vertebrates [29,41]. The identification of other genes underlying hybrid male sterility in the wild remains a challenge, but the combination of mapping studies in the laboratory and in regions showing limited introgression in nature have identified good candidates for future study [18,32,42]. Despite the high degree of hybrid incompatibility and reduced fitness, most standard inbred strains of laboratory mice have been derived from admixtures between mouse subspecies. They often feature Y-chromosome or mitochondrial capture, where these uni-parentally inherited markers do not match the ancestry of the rest of the genome [43–45].

The GigaMUGA array is the third generation of the Mouse Universal Genotyping Array (MUGA) and consists of a 143 259-probe Illumina Infinium II array developed specifically for the house mouse. These probes were designed to be evenly distributed across the 19 autosomal, and X and Y chromosomes with minimal linkage disequilibrium (LD), and they include markers across the mitochondrial genome [45]. While the GigaMUGA array was optimized for Collaborative Cross and Diversity Outbred populations, for substrain-level identification of laboratory mice, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) informative for subspecies of origin were also included to facilitate studies of wild mice. The array was designed to have a density of at least one ‘diagnostic marker’ per 300 kb for each subspecies, and to place at least one diagnostic marker for each subspecies within each recombination of the intervals identified in Liu et al. [46]. Therefore, this cheap, high-density array specified for high-throughput biomedical and developmental genomic studies has the potential to analyse colonization patterns and evolutionary genomics of wild mice at an unprecedented scale.

1.1. Mice in New Zealand

House mice have accompanied humans around the world for thousands of years [47]. Because of their high-standing genetic diversity, it has been possible to track the origins of introduced mouse populations [2], revealing activities and movements of people invisible to traditional historical methods [48–52]. New Zealand was entirely free of all terrestrial mammals until the introduction of the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans), which arrived with Polynesian settlement around 1280 AD [53]. House mice arrived among infested food and cargo on early European vessels, starting around the 1790s [54].

Most New Zealand mice closely resemble M. m. domesticus morphologically, however some morphological characteristics of M. m. musculus have been identified at low frequencies [48]. The mitochondrial diversity of New Zealand mice is surprisingly large, with 23 M. m. domesticus D-loop haplotypes descending from all six major M. m. domesticus clades, six M. m. castaneus D-loop haplotypes from a single clade and one M. m. musculus haplotype so far identified [48,55]. Across most of the two main islands, and on most offshore islands, M. m. domesticus mitochondrial haplotypes predominate. In the southern South Island, however, one M. m. castaneus mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is solely found, with a narrow ‘hybrid’ zone around 50 km wide separating the M. m. castaneus to the south and M. m. domesticus to the north [22,55]. The same M. m. castaneus mtDNA haplotype is also present in the lower North Island around the Wellington region, and a second one is the only mtDNA haplotype so far identified on Chatham Island. The only place where M. m. musculus mtDNA has been detected is in the lower North Island in Wellington.

While the distribution of mouse mitochondrial lineages across New Zealand has been well documented, the nuclear genomic ancestry of mice in New Zealand is poorly understood. All studies to date have found a predominance of M. m. domesticus nuclear ancestry across the country, including ‘hybrid’ populations containing unquantified mixes of the other two subspecies present but insufficiently characterized. Of the few nuclear markers that have been sequenced previously, all mice, regardless of mitochondrial haplotype, have had predominantly M. m. domesticus ancestry, though some mice in the upper South Island also have had M. m. musculus markers [22]. No M. m. castaneus nuclear ancestry has yet been detected in New Zealand mice.

New Zealand mouse populations are of particular interest for genetic studies due to the presence of hybrids between all three subspecies. Hybrids of domesticus/castaneus are of particular interest, as this mixture has rarely been studied, and has never been confirmed in their native range. In this study, we aimed to ascertain the relative contribution of each subspecies to these hybrid populations, with a view to better understanding the invasion history of mice in New Zealand, describing the spatial patterns of present genomic diversity, and the ancestral origins of each population.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection

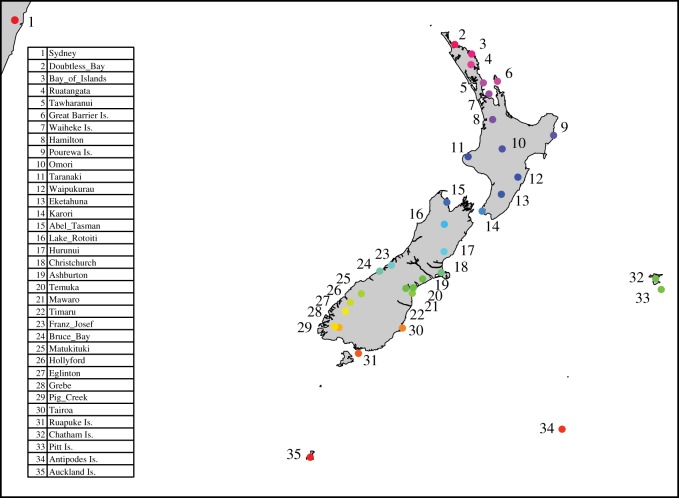

A total of 182 mouse tail samples approximately 10 mm long were obtained from across the country (figure 1), selected to achieve geographically representative sampling from across the two main islands, from all distant offshore islands with extant mouse populations, some large inshore islands, and from Sydney, Australia—a potential source population for invading mice, as it was the major port in the region in the nineteenth century. Where possible, samples of known mitochondrial lineages that had previously been sequenced for the mitochondrial control region by King et al. [55] were used. Fifty-nine new samples were obtained from locations of interest that had previously not been sampled, or from locations where these previous tissue samples were found to be degraded. Tail samples were stored frozen from fresh.

Figure 1.

Sampling locations for genomic genotyping. For the mitochondrial dataset, data from King et al. [55] was also included (q.v. for map and further details on those sample sites). Colour codes are based on latitude and used to help display relationships between sampling locations in future figures.

2.2. DNA extraction and GigaMUGA sequencing

Tail samples were sent to the University of North Carolina, where genomic DNA was extracted using a Qiagen Gentra Pure tissue kit according to the manufacturer's protocols. All genome-wide genotyping was performed using the GigaMUGA array at the University of North Carolina (GeneSeek, Lincoln, NE) [56]. Genotypes were called using Illumina BeadStudio (Illumina, Carlsbad, CA) and processed with argyle [57].

2.3. Bioinformatic filtering and analyses

We filtered and combined the separate genotyping runs in argyle [57], an R package specifically designed for manipulating MUGA data. We then used PLINK 1.9 [58] to remove any individuals from the dataset that had 10% or more missing data, and to filter SNPs based on coverage across individuals (loci were retained only if present in at least 90% of samples). All further filtering and analyses steps were also conducted in PLINK 1.9 unless otherwise stated. We then merged our dataset with two published datasets: (i) the reference GigaMUGA dataset (with a number of loci identical to our data) and (ii) the MegaMUGA wild mouse reference dataset. For the GigaMUGA dataset, we included only wild mice, and a few wild-derived laboratory strains that had been shown previously to be relatively pure and non-divergent from their sub-specific origins [56]. This dataset therefore retained only a handful of each subspecies as references, but contained the full set of approximately 135 000 SNP markers. The MegaMUGA SNP array consists of approximately 78 000 markers, of which approximately 65 000 overlap with the GigaMUGA array. Over 500 wild mice from across the native range have been genotyped using the MegaMUGA array, therefore this dataset provided a much larger wild reference dataset than the GigaMUGA reference dataset, but with reduced SNP coverage. Both our combined datasets were filtered for LD with a window size of 10 kb, a step size of 5 and an R2 of 2.

Both of these datasets were then filtered for a minimum minor allele frequency of 0.05. For subspecies identification, we further filtered the data to include only those loci which were most highly differentiated between subspecies (dataset 3). When the MegaMUGA array was developed, Morgan & Welsh [56] evaluated the information content of each site in terms of subspecies differentiation—calculating the Shannon information content for each locus. This takes values between 0 and 1, where 0 means identical allele frequencies and, therefore, no information to inform identification, and 1 is reached when it detects a fixed difference between subspecies. We filtered our data for subspecies admixture calculations to exclude loci with a Shannon information of less than 0.5—leaving only loci with high differentiation between subspecies, and removing the ascertainment bias in the chip towards M. m. domesticus diversity.

To investigate the population genetic structure within New Zealand, we used the program fastSTRUCTURE [59], on the complete dataset (dataset 1) employing the choose.K command to ascertain the optimal number of clusters present in our data. To examine the autosomal (and X chromosomal) subspecies ancestry of individuals, we used the program ADMIXTURE, using both the combined MegaMUGA reference dataset (dataset 2) and the reduced, weighted dataset that contained only those SNPs that were most diagnostic for subspecies identification (dataset 3). For genome-wide comparisons in ADMIXTURE, we did some initial pilot runs using all of the reference samples, and then when it became clear that the majority of M. m. domesticus ancestry came from Europe, as expected from historical shipping records, we limited the subspecies reference dataset to include only wild M. m. domesticus from this region. This was done because working with highly uneven reference populations may cause biases in admixture assignment [60]. ADMIXTURE was run for all autosomal chromosomes together, and for each chromosome separately, to further resolve the contributions of each subspecies to the genomic makeup of each mouse. We then used the R package TessR3 to plot ancestry admixture coefficients spatially using Kriging [61].

As a comparison for the ADMIXTURE outputs, we also used the MegaMUGA wild mouse reference database to search for fixed differences (diagnostic SNPs) among subspecies reference sets, and then counted the relative contribution of these SNPs to each of the New Zealand mouse samples. While these diagnostic data yield a far smaller dataset than the total GigaMUGA or MegaMUGA genotypes, it provides an unbiased estimate of ancestral contribution, which can be compared to the model-based outputs from ADMIXTURE.

We extracted both the mitochondrial and Y-chromosome SNPs and compared these haplotypes with the GigaMUGA reference samples, and with the known mitochondrial control region sequences previously recorded for most of the New Zealand samples [55]. There are multiple (greater than 5) diagnostic SNPs on both the Y chromosome and mt-genome featured on this array, therefore we were able accurately to classify each haplotype to subspecies origin, and, where possible, to infra-subspecies clade.

We created an identity-by-state differentiation matrix between individuals using PLINK, and used these to construct neighbour-joining trees in the R package APE [62], and principal component analyses (PCAs) in PLINK. We ran these analyses both for the New Zealand samples independently, and for the combined GigaMUGA (dataset 1) and MegaMUGA (dataset 2) references.

3. Results

3.1. Data filtering and statistics

Of the 182 mouse tail samples collected from around New Zealand (and from Sydney and Lord Howe Island in Australia), 166 had high enough DNA quality to pass quality control and be analysed using the GigaMUGA SNP array. We filtered for a maximum of 10% missing data per individual, removing a further five individuals, yielding a final dataset of 161 mice. Neither of the two mouse samples obtained from Lord Howe Island were of high enough quality to be retained in analyses, but all other locations remained represented for spatial population analyses.

Of the 129 704 autosomal SNPs, 119 645 remained after filtering for coverage, and 49 266 remained for analyses requiring linkage equilibrium. Examining the reference samples, mitochondrial and Y-chromosome haplotypes could be assigned to subspecies using multiple (greater than 5) fixed differences, and to intra-subspecies clade by greater than 2 fixed SNPs. For mitochondrial haplotypes and clades for all individuals, see the electronic supplementary material, table ST1. For the subspecies admixture analyses, we retained only SNPs that had a differentiation Shannon weighting of greater than 0.5 between subspecies, leaving the most differentiated 9501 SNPs for high-accuracy subspecies genomic assignment, and these were scattered across all chromosomes (electronic supplementary material, table ST2).

As a second method to confirm ancestry proportions, we created datasets composed of fixed differences between subspecies pairs domesticus/castaneus (106 loci) and domesticus/musculus (481 loci). The relative number of these ‘fixed’ loci between subspecies will not reflect real differences in the levels of similarity between subspecies, nor are they necessarily fixed, because the sizes of the M. m. castaneus and M. m. musculus reference populations were small relative to those for M. m. domesticus. Given the large size of the M. m. domesticus reference dataset, these ‘fixed’ differences do however represent loci where one allele is likely to be very rare or absent from M. m. domesticus, therefore these should be useful for identifying ancestry from these other two subspecies.

3.2. Genetic population structure

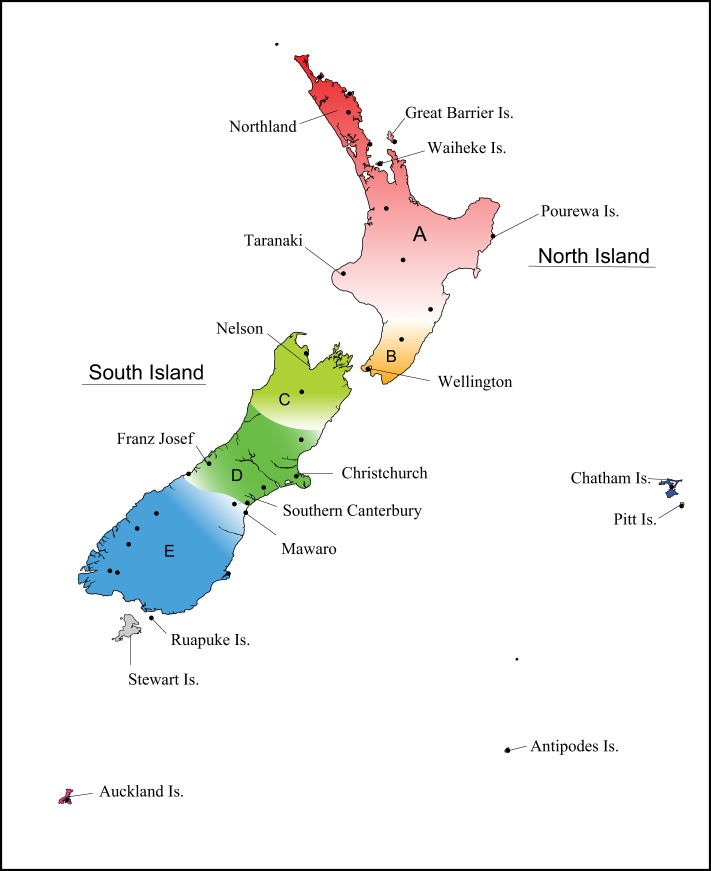

Across all sampling locations, individuals grouped together most closely with other individuals from the same location—see neighbour-joining trees (electronic supplementary material, figures SF1, SF2), indicating that differentiation between locations was always higher than within them. There was also clear regional structure evident: for ease in describing the spatial genetic patterns of mice across New Zealand, we have divided the two main islands into five regions (A–E) corresponding to population genetic regions, and provide a map highlighting the locations mentioned in the text (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of New Zealand indicating the geographical regions discussed and highlighting any particular locations mentioned in the text. Sampling locations shown as black dots.

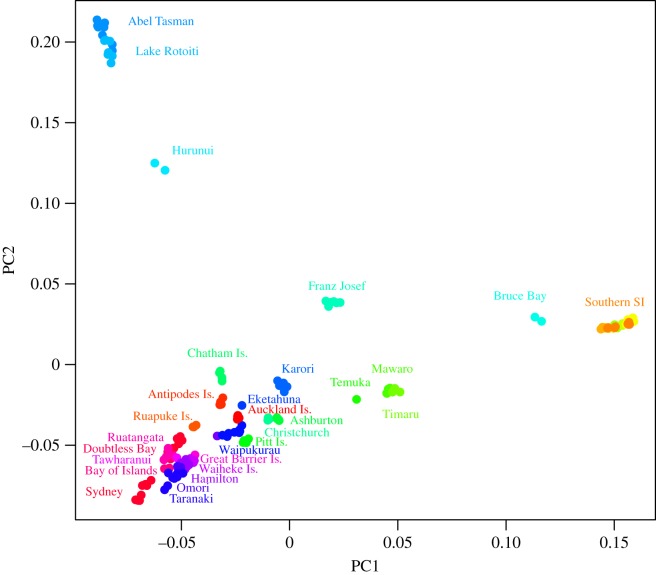

The primary population genetic structure among mouse populations in New Zealand is defined by the divergences between the southern South Island sampling locations (Matukituki, Hollyford, Eglinton, Grebe, Pig Creek and Tairoa—region E; for detailed location data, see [55]), and the northern South Island sampling locations (Abel Tasman & Lake Rotoiti—region C) from the remaining locations (figure 3). Sampling locations that exhibit admixtures with these divergent groups within the South Island (e.g. Hurunui, Bruce Bay), are shown as slightly divergent from the other populations.

Figure 3.

PCA based on identity by descent for all New Zealand mice derived from LD filtered loci. The southern South Island population (Southern SI) consists of Matukituki, Hollyford, Eglinton, Grebe, Pig Creek and Tairoa, which overlap too much to be labelled separately. Colours are derived from latitude, matching figure 1.

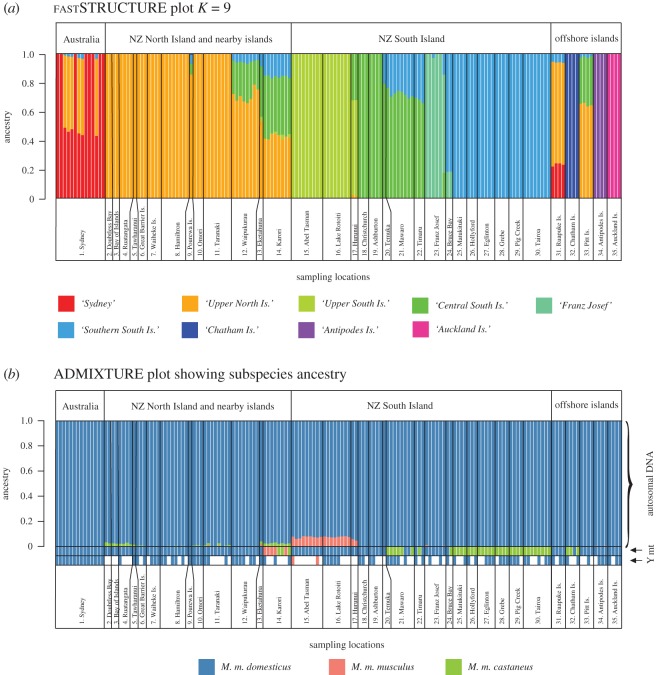

While mice from each location could be identified to their sampling location (electronic supplementary material, figures SF1, SF2), fastSTRUCTURE indicated nine clusters were optimal to explain the genetic differentiation present across New Zealand (figure 4a). These clusters represent groups of individuals with similar genetic makeup and similar ancestry—though there will be spatial patterns of diversity and connectivity within these groupings. It is possible that each cluster therefore represents a different population, founded primarily via different introduction events, though long periods of relative isolation could also account for the divergence of clusters.

Figure 4.

(a) Cluster assignment plot derived from fastSTRUCTURE (K = 9) for New Zealand mice. Each individual mouse is represented by a column, and the proportion of each colour is the proportion of ancestry from that cluster. Clusters are named according to the region that primarily contributes to that cluster. (b) ADMIXTURE plot showing the percentage of autosomal nuclear DNA ancestry from each subspecies for each mouse, along with their matrilineal mitochondrial (mt) and patrilineal Y-chromosome (Y) ancestry. Each individual mouse is represented by a column, with the proportion of each colour representing the proportion of ancestry derived from each subspecies.

Three of the most remote offshore islands (Chatham, Antipodes and Auckland) are highly differentiated from all other populations. Ruapuke Island clusters with Sydney and some North Island sites, and Pitt Island is most similar to locations in the lower North Island. The relatively near shore islands (Great Barrier, Waiheke and Pourewa islands) belong to the same cluster as nearby North Island mainland locations—all in region A.

For the mainland sites, admixture between clusters is evident, with southern Canterbury (Mawaro, Timaru and Temuka) being composed of a mixture of central South Island cluster to the north (Christchurch, Ashburton—region D) and the southern South Island cluster to the south (Matukituki, Hollyford, Eglinton, Grebe, Pig Creek and Tairoa—region E). In the lower North Island—region B—a mixture of clusters is also evident, with contributions from the northern North Island cluster diminishing southwards, plus elements of both the central and southern South Island clusters.

3.3. Genomic contributions from each subspecies

We found significant discrepancies among the mitochondrial, autosomal and Y-chromosome ancestries across the country, indicating frequent admixtures between subspecies and genetic clusters in multiple locations, both before and after arrival in New Zealand (figure 4b).

Across all sampling locations, ADMIXTURE indicated that the nuclear ancestries of New Zealand (and Australian) mice are predominantly M. m. domesticus. In the southern North Island (region B), southern South Island (region E) and on Chatham Island, there were notable discrepancies between mitochondrial ancestry and nuclear ancestry (figures 4b and 5). In Wellington (Karori), all mice had either M. m. musculus or M. m. castaneus mtDNA, while their autosomal DNA consistently showed approximately 97% M. m. domesticus ancestry, with approximately 2% M. m. castaneus and approximately 0.02% M. m. musculus input. In the southern South Island M. m. castaneus mtDNA dominated, with all mice sampled south of Mawaro having M. m. castaneus mtDNA. ADMIXTURE however indicated no trace (less than 0.001%) of M. m. castaneus nuclear DNA in any individuals from these locations, and effectively no trace of M. m. castaneus nuclear ancestry across the South Island. This ADMIXTURE result matched closely the ‘diagnostic’ subspecies SNP frequencies, with 0.6% of ‘diagnostic’ M. m. castaneus alleles present on average across the southern South Island. Across all populations the diagnostic SNP marker sets confirmed the ADMIXTURE analyses (electronic supplementary material, figure SF3), although because many of these loci are identical between M. m. musculus and M. m. castaneus, the proportions of hybrid alleles should be interpreted as a percentage of ancestry that is non-domesticus rather than clearly identifying one or other of these two minor component subspecies.

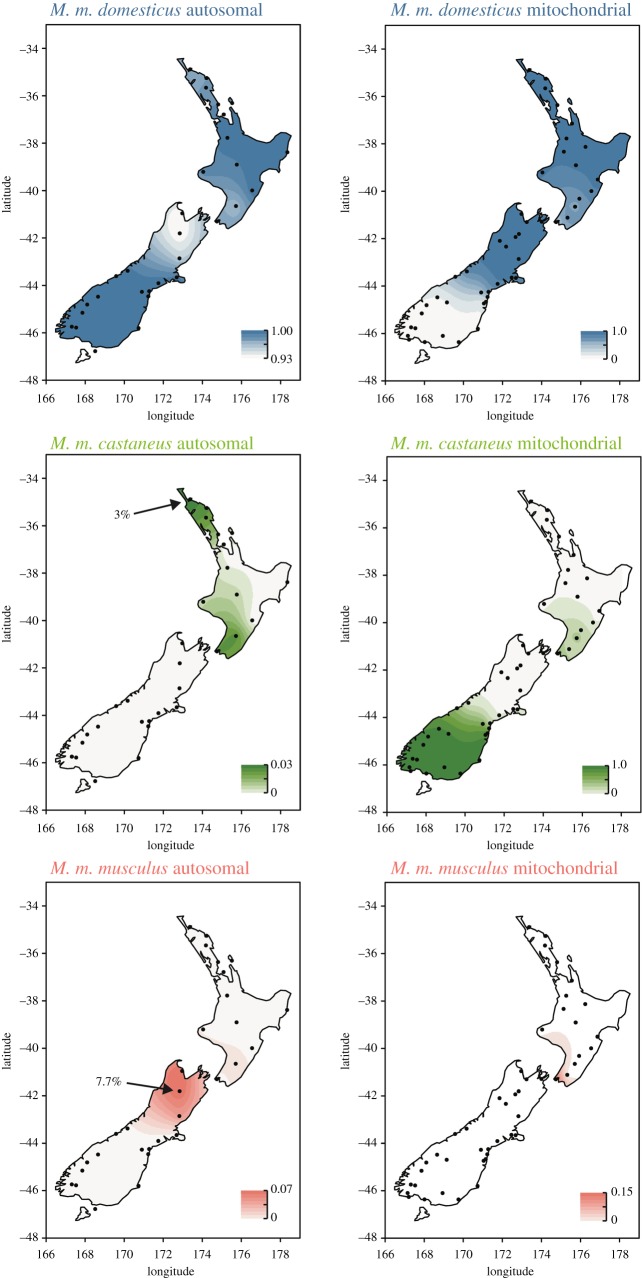

Figure 5.

Maps of New Zealand showing the comparative subspecies ancestry proportions for mice in each region as determined in Tess3r for both nuclear autosomal DNA (left) and mitochondrial DNA (right). Note the different scales for each map, as ancestry percentages varied hugely between subspecies and DNA type. Mitochondrial data are concatenated from the present study and King et al. [55]. Sampling locations are shown as dots; the places with the maximum recorded nuclear ancestry for M. m. castaneus and M. m. musculus are indicated.

We detected a similar situation on Chatham Island, where three of the four mice sampled had M. m. castaneus mtDNA, and the fourth had M. m. domesticus mtDNA. No M. m. domesticus mtDNA had previously been recorded among nine mice previously collected there. Nuclear ancestry of Chatham Island mice was consistently over 99.8% M. m. domesticus from the ADMIXTURE analysis. The diagnostic SNP analysis gave a slightly higher percentage of M. m. castaneus ancestry (approx. 3%), though with the small number of loci available this may be less accurate than the approximately 9500 SNPs analysed in ADMIXTURE. The M. m. castaneus mitochondrial genotypes from Chatham Island matched the previously identified casNZ.2 haplotype, and the single M. m. domesticus mitochondrial haplotype matched M. m. domesticus clade E haplotypes, which dominate both the North and South Islands.

The spatial distribution of subspecies ancestry, and the discrepancies between the mitochondrial haplotypes and nuclear genomes are highlighted in figure 5—note the differences in ancestry proportions in the scale bars between the comparative mitochondrial and nuclear maps. The only places in the country with any substantial M. m. castaneus contribution to the nuclear genome were in Northland (Doubtless Bay, Bay of Islands, Ruatangata, and Tawharanui—the northern part of region A), and the Wellington region (Karori and Eketahuna—region B), with 2–3% M.m. castaneus ancestry each (figure 5). Traces (approx. 1%) of M. m. castaneus ancestry were also recorded in Taranaki. Of these places, only Wellington had any evidence of M. m. castaneus mtDNA, and M. m. castaneus Y-chromosomal DNA was never recorded in any of the sampled locations.

While M. m. musculus mtDNA has never been recorded in the South Island, the three populations sampled in the north of the South Island (region C) showed a gradient of M. m. musculus autosomal ancestry from approximately 7–8% in Abel Tasman National Park and Lake Rotoiti, declining southwards to 5% at Hurunui. Two mice sampled from Franz Josef had approximately 1% M. m. musculus nuclear ancestry, suggesting that gene flow containing this admixed DNA has spread this far south. These observations were confirmed by the diagnostic SNP frequencies, and the M. m. musculus diagnostic alleles often clustered together on the genome, representing stretches of chromosomes inherited from this subspecies. The only two male mice sampled from Abel Tasman National Park both had M. m. musculus Y chromosomes—and these were the only mice sampled across the entire study not to have M. m. domesticus Y-chromosomal ancestry.

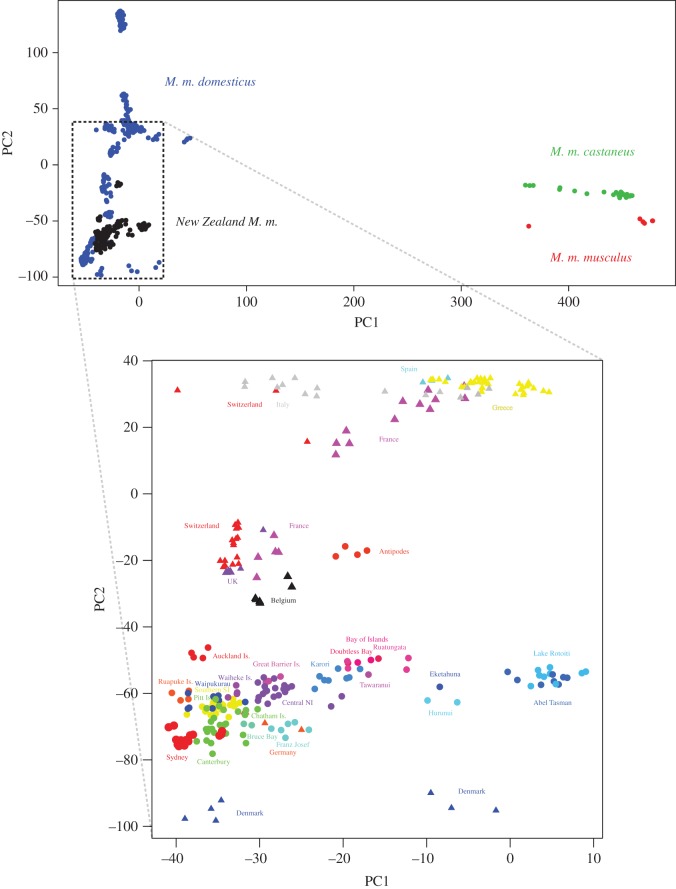

Comparing the samples of mice from New Zealand and from the native range shows that all New Zealand mice clearly cluster with the wild native M. m. domesticus samples (figure 6), though the populations with some M. m. musculus admixture (Lake Rotoiti, Abel Tasman, Hurunui—region C) and M. m. castaneus admixture (Eketahuna, Doubtless Bay, Bay of Islands, Ruatangata, Tawharanui and Karori) are pulled slightly right, towards their respective minor subspecies components.

Figure 6.

PCA based on sections of identity by descent for all wild mice genotyped with the MegaMUGA SNP array, with an enlargement below of the distribution of New Zealand wild mouse samples. New Zealand locations are shown as circles, native-range samples are shown as triangles (in the lower plot). Owing to crowding we amalgamated some sampling locations for ease of display: Canterbury = (Christchurch, Ashburton, Mawaro, Temuka, Timaru), Central NI = (Hamilton, Omori, Taranaki, Pourewa Is.) and Southern SI = (Matukituki, Hollyford, Eglinton, Grebe, Pig Creek, Tairoa).

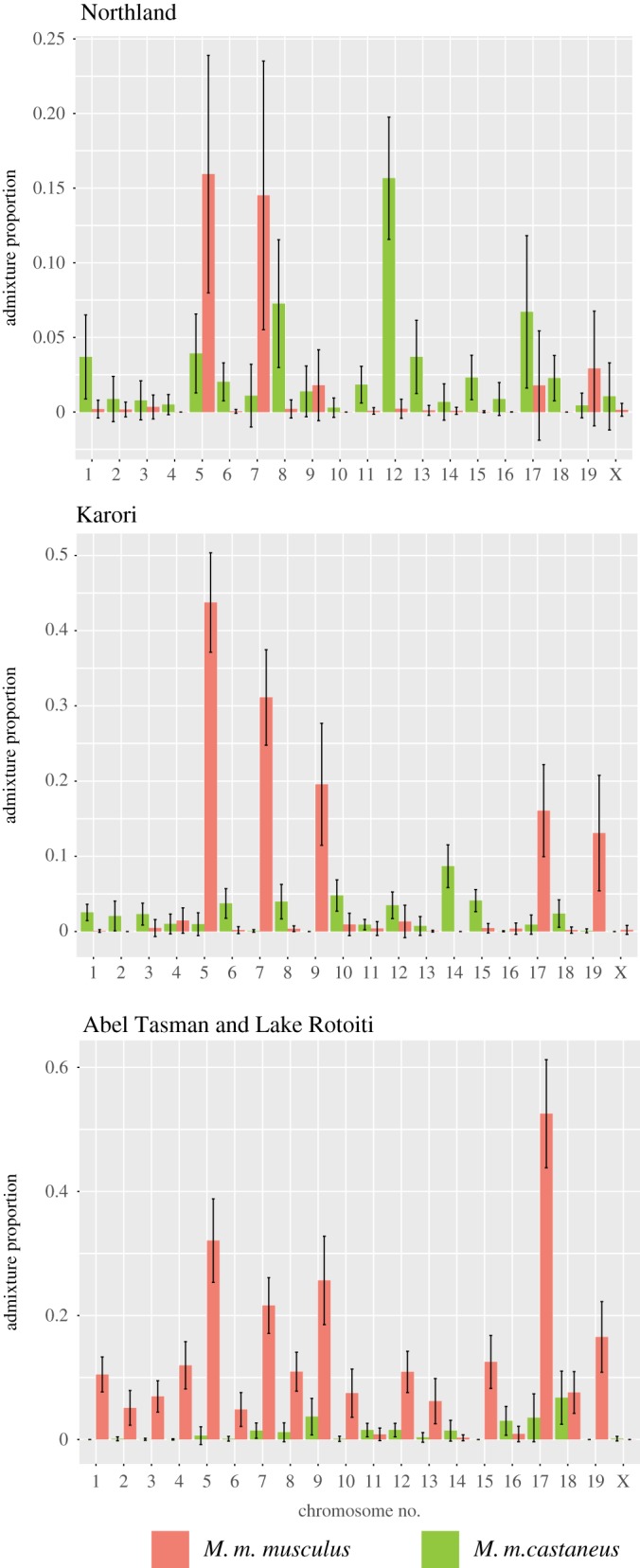

The contributions of each subspecies to the genomic makeup of New Zealand mice varied significantly across chromosomes (figure 7). For the three identified geographic regions with large numbers of admixed individuals (at the nuclear level)—Northland, Wellington, and the upper South Island---we display these results graphically (figure 7). Of particular note, there was minimal evidence for genomic input from M. m. castaneus or M. m. musculus for the X chromosome across these three populations, but a large proportion (greater than 50%) of the genomic ancestry of mice from the upper South Island came from M. m. musculus on chromosome 17, compared with the average M. m. musculus ancestry across the genome of around 7.5%.

Figure 7.

The proportion of admixture by chromosome for the three regions with highest nuclear diversity (Northland: Doubtless Bay, Bay of Islands, Ruatangata, Tawharanui; Karori; and the upper South Island: Abel Tasman and Lake Rotoiti). In all cases, only the admixture contributions of M. m. castaneus and M. m. musculus are shown—the remainder being M. m. domesticus.

4. Discussion

The application of cheap high-density genotyping arrays now available for mice has corrected many false assumptions, and greatly increased our knowledge about the diversity, ancestry and admixture of laboratory mice [45,63]. These tools, developed primarily for developmental genetics and biomedical research, can also assist us in understanding the ancestry, invasion histories and diversity of wild mice populations. Using the GigaMUGA SNP genotyping array, we have significantly expanded our knowledge of the genomic diversity and colonization history of mice in New Zealand—highlighting the need to go beyond mitochondrial markers to trace biological invasions. This need for greater genomic resolution in evaluating biological invasions was recently also emphasized in a similar genomic study of Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) [64]—another species for which invasion biology has benefitted from the genomic resources developed using domesticated laboratory strains. We have also gained significant insights into the abilities of wild mouse subspecies to hybridize during colonization events.

4.1. Insights into mouse subspecies hybridization

New Zealand is a particularly interesting location to look at the hybridization of mouse subspecies in the wild, because traces of ancestry from all three major subspecies are present, the results of multiple comparatively recent hybridization events. The hybrid domesticus/castaneus populations in New Zealand are of particular interest given the rarity of this particular cross, however both of the previously identified ‘hybrid’ populations, one in the south of the South Island—region E---and the other on Chatham Island, are hybrids only in the very limited sense that there is discordance between their nuclear M. m. domesticus and mitochondrial M. m. castaneus DNA. Both populations are essentially pure M. m. domesticus across the nuclear genome, but they retain the mitochondrial ‘ghosts’ of a previous hybridization event which failed to lead to nuclear admixture in the long term, i.e. they are cases of ‘mitochondrial lineage capture’ (reviewed in [65]). The fact that these populations have significantly different M. m. castaneus mitochondrial haplotypes implies that these mitochondrial lineage capture events occurred independently. The process of mitochondrial lineage capture has been observed across a diverse range of taxa including Crotaphytus lizards [66], chipmunks [67], loaches [68], deer [69], goats [70], hares [71–73], pocket gophers [74], voles [75], daphnia [76], and indeed between mouse subspecies [45,77,78]. While relatively commonly identified in mammals, mitochondrial capture with no traces of nuclear introgression has rarely been demonstrated to be so complete as in these mouse populations. Our ability to detect it has been made possible due to the extensive genomic markers available for this species.

Theoretical comparisons of pre- and post-zygotic models of isolation demonstrate that, under certain conditions, models of prezygotic isolation (e.g. female choice or male–male competition) allow for much more rapid introgression of maternally inherited DNA [79]. This result should be strongest when the source of the mtDNA is relatively rare, overall population sizes are small and there is asymmetric hybridization [65,79]. These are precisely the conditions that would have occurred if a small founding population of resident M. m. castaneus was invaded by M. m. domesticus mice, and it is particularly likely given the relative hybrid fitness of these two subspecies.

The authors of reports of attempted crosses at the Jackson laboratory between M. m. castaneus and M. m. domesticus state that fighting is particularly prevalent in progeny of any crosses involving male M. m. castaneus [22]. Similarly, in the Collaborative Cross, a set of recombinant inbred lines derived from crosses between eight strains [80], the M. m. castaneus X chromosome was underrepresented [31]. Male infertility was responsible for nearly half of all observed lineage extinctions [81]. Furthermore, severe breeding problems have also been noted with crosses of another M. m. castaneus strain, CasA [82]. A recent quantitative trait loci study of genes related to hybrid fitness identified regions on the autosomes, the X chromosome, and particularly in the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of the X and Y chromosomes which confer hybrid male sterility for crosses between M. m. domesticus and M. m. castaneus [31]. A substantial proportion of F2 males in White et al.'s study [31] exhibited phenotypes that previously had been connected with sterility. These included high levels of abnormal sperm, strong reductions in the apical sperm hook and severely amorphous sperm heads that are unable to fertilize ova [40,83,84]. All of these factors indicate that when initially successful, hybridization between M. m. domesticus and M. m. castaneus is likely to be highly asymmetrical and unstable due to both behavioural and genetic incompatibility.

Along with the domesticus/castaneus hybrid populations described above, there is evidence of a hybrid population with nuclear introgression in the northern half of the South Island, between M. m. domesticus and M. m. musculus. The nuclear ancestry of this population is approximately 92% domesticus/8% musculus population, and Y chromosomes from both subspecies are present in this region. These two Y chromosomes could be spatially differentiated, because M. m. musculus Y chromosomes were recorded only in the two male mice sampled from Abel Tasman National Park, while only domesticus Y chromosomes were detected in five males from Lake Rotoiti. Given the small numbers sampled, we can only speculate about this trend. We have yet to find evidence of M. m. musculus mitochondrial ancestry in this population. Our results expand and quantify the findings of Searle et al. [48], who also found some evidence of domesticus/musculus hybrids in this region.

Our finding that the domesticus/musculus hybrid population in the upper South Island has particularly high M. m. musculus ancestry for chromosome 17 is also an intriguing result worthy of further investigation. The only gene (Prdm9) known to cause hybrid sterility in vertebrates, identified in crosses between M. m. musculus and a classical inbred strain primarily derived from M. m. domesticus, is on chromosome 17 [27,29,85]. Our results could indicate that incompatibilities in this region have led to a high proportion of this chromosome being inherited from M. m. musculus across this population.

4.2. The mouse invasion history of New Zealand

Our study highlights the extreme complexity of assessing the origins and invasion pathways of organisms using genetic data. While our results match those of previous studies [22,48,55], the vastly increased range of genetic markers highlight the need for genomic data to fully explain invasion histories. These previous studies relied on mitochondrial data, along with a handful of nuclear markers, because this focus allowed large numbers of mice to be genotyped. Since mitochondrial DNA is uni-parentally inherited, a clear and detailed pattern of inheritance can be established for this molecule and the matrilineal history [51]. Gene trees, however, are not species trees, and mitochondrial DNA is only one locus, which is largely unrelated to phenotype.

Firstly, we note the similarity of the nuclear genomes of mice across New Zealand. All mice in New Zealand other than those on Antipodes and Auckland Islands genetically clustered together with each other (and with Sydney, Australia), indicating similar origins, or significant mixing among locations post-introduction. This pattern of similarity among most New Zealand sites (other than Antipodes and Auckland Islands) is more clearly seen in the electronic supplementary material, figures SF1, SF2. As previous work has indicated by the diversity of mitochondrial haplotypes, there have been many introductions to New Zealand of mice representing diverse origins; however, those that have contributed to the bulk of the modern nuclear genetic diversity across the country are primarily descended from M. m. domesticus ancestors from northwestern Europe.

Our study has revealed discordant genomes in many parts of New Zealand, as in other well-studied islands such as Madeira subject to multiple invasions by mice of different origin [86–93]. The differences between the genders in behaviour and breeding biology permit invading male markers to spread more rapidly than female markers [94]. Hence, island populations are more porous to incoming males than to females, so mtDNA is more likely to mark the original colonists. Therefore, mtDNA can be helpful in establishing priority among propagules in the order of colonization, but misleading as to the genomic ancestry of individuals in the extant population. Here we update and review the story of the mouse invasion of New Zealand and its surrounding knowledge, in light of our new insights from the genomic data. King [54] made a number of hypotheses as to the origins of New Zealand mice, at that time based on mitochondrial data along with historical shipping records. We have reproduced a table of these hypotheses, along with the level of support offered by the genomic data (electronic supplementary material, table ST3).

Briefly, the hypothesis of mice arriving to Sydney with supply fleets from Europe is highly supported, as all Sydney mice cluster with northwestern European mice—as had previously been suggested using mitochondrial data [49]. The hypothesis of mice arriving in Sydney from India or Canton is not supported, as no M. m. castaneus nuclear or mitochondrial ancestry has been detected. If M. m. castaneus arrived in Sydney they either failed to establish, or were entirely replaced by M. m. domesticus. We cannot rule out traces of M. m. castaneus in small local populations around the ports—as our samples came from the north and west of Sydney, but if these exist, this genetic component must be minimal for traces to not have spread further.

The lack of M. m. castaneus signal in Sydney means that the M. m. castaneus ancestry recorded in New Zealand is likely to have come directly from Asia. There are clearly two M. m. castaneus mitochondrial lineages in New Zealand: (i) the southern South Island (region E) which is also present in the southern North Island (Region B), and (ii) Chatham Island. Nuclear M. m. castaneus ancestry was however only recorded in the North Island, primarily in the southern and northern regions (figure 5). There are several possible scenarios that may account for the first of these two hybrid populations (on the North and South Islands). King suggests (i) direct colonization of the southern South Island from Canton by sealers in the 1790s to 1810s, (ii) colonization from trading ships from China to Wellington from 1840 and (iii) from China to the southern South Island (Dunedin or Hokitika) with gold miners from 1865–1890 [54]. We cannot rule out any of these hypotheses, but given that the majority (or all of) the nuclear genome of mice in these regions has been replaced with M. m. domesticus DNA, hybridization must have started early, potentially before arrival on a boat or in a previous port.

The fact that it is the same mitochondrial lineage in the southern North Island and the southern South Island brings up the possibility that mice with M. m. castaneus ancestry colonized only one of these places, then moved to the other. This hypothesis is supported by the mixture of genetic clusters found in Wellington, including some ancestry for the southern South Island cluster. We have not yet tried to assess the direction of this movement.

In the northern North Island, the discordance between the same two subspecies runs in the opposite direction (figure 4) with some traces of M. m. castaneus nuclear ancestry, but with no M. m. castaneus mitochondrial DNA yet detected. In the 107 mice from that area previously examined, 92% carried a single haplotype of M. m. domesticus identical to equivalent representatives of clade E in UK and Australia. For compelling biological reasons summarized above, it is reasonable to doubt that M. m. castaneus could have invaded such a strongly established M.m. domesticus population in Northland. There are also historical reasons to suspect that mice arrived in the Bay of Islands only in the 1820s or 1830s, after restrictions on trans-Tasman trade with Sydney were lifted [54]. Sydney had by then developed into the major port of the southwest Pacific, offering unlimited opportunities for hybridization among mice living on shore or among cargo. The most likely explanation for our results is that the mice colonizing Northland and spreading south were already hybrids, dominantly M.m. domesticus but carrying evidence of past encounters with M. m. castaneus.

4.3. Offshore island mouse invasion histories

Mice from the three relatively near-shore islands off the northeast coast of the North Island (Great Barrier, Waiheke and Pourewa) all belonged to the same cluster as the nearby mainland, indicating probable colonization from vessels moving between the mainland and each island.

Although Chatham and Pitt islands are relatively close to each other (approx. 25 km), their mouse populations have different genetic histories. Pitt Island mice appear to be mixed from two clusters—the central South Island cluster and the North Island cluster. Pitt Island mice had the mitochondrial D-loop haplotype DomNZ.7, and the only locations it has been found on the main islands of New Zealand are around Timaru—where the primary shipping company to Pitt Island is based. Our results therefore strengthen the view that mice may have been exchanged between Pitt Island and the South Island [55]. Chatham Island mice, however, were very different. Mice from this population predominantly had an M. m. castaneus haplotype, casNZ.2, which has yet to be detected anywhere else in New Zealand or Australia. It remains difficult to speculate as to the origins of this population as there are no clear mitochondrial links, and nuclear clustering indicates it is very separate from other New Zealand populations. This differentiation may be due to high genetic drift and founding effects, or because these mice have (some) origins independent of the other New Zealand populations.

Three New Zealand southern island populations—Auckland, Antipodes and Ruapuke Islands---supported mice belonging to clades different from the rest of the New Zealand mouse samples, indicating a probable origin outside of mainland New Zealand. Our genetic results lend strong support to two specific introduction scenarios for the Antipodes and Ruapuke mice.

All Antipodes Island mice so far sequenced were mitochondrial M. m. domesticus clade C, a clade originating from France, Spain, Portugal and Italy [19] that has yet to be detected on mainland New Zealand, or in Sydney—although a different clade C haplotype is present on Ruapuke Island. The origins of the Antipodes mice appear to be independent of the other mice in New Zealand, with strong inferred genetic links to France as the source of this invasion. As suggested by Russell [95], the Antipodes Island mouse population was probably founded through a shipwreck, and a likely contender is that of the Président Felix Fauré, a four-masted barque which was wrecked on rocks on the north side of the island in Anchorage Bay in 1908. All 22 men on board made it ashore and survived for two months before being rescued [96,97]. The first records of mice on Antipodes Island are dated to one year later in 1909, by Waite [98] who wrote, ‘I am told by Captain Bollons that mice are very numerous at the Government depots on Campbell and Antipodes Islands'.

The genomic links between the Ruapuke Island population and mice from Sydney also match the known invasion history of the island. The first recorded population of mice in New Zealand arrived on Ruapuke in 1824 with the stranded flax trading ship Elizabeth Henrietta, which came from Sydney [99]. The fact that they have a mitochondrial haplotype of clade C not yet observed in Sydney (or mainland New Zealand) could be due to (i) the small number of samples available of mitochondrial haplotypes from Australia, which are few and not from around the historical dock area; or (ii), founding effects whereby a small random sample of a relatively rare haplotype in Sydney rose to prominence on Ruapuke Island.

The origin of the Auckland Island mice remains less certain. Following the discovery of the Auckland Islands in 1806, mice were first recorded there in 1840 by a United States expedition, but likely had already been present for some time before this. As there are no records of shipwrecks during this period, it is speculated that mice arrived here during sealing activities [100]. The only mitochondrial haplotype found on Auckland Island (NZ_dom4) is from clade E and matches haplotypes from Sydney, and both North and South Islands of mainland New Zealand. At a nuclear level, however, this population clades most closely with introduced mouse populations from the USA. This population was possibly founded through activities of American sealers (or whalers) which were both active in the region at the time, although, due to the very significant bottleneck experienced by the Auckland Island population, further research and modelling will be needed to reveal the source of the mouse population on Auckland Island.

4.4. Applicability of the GigaMUGA SNP array

Ideally for population genomic studies, SNP variation recorded should represent the average SNP variation present across individuals, however this is rarely the case. SNP genotyping often suffers from an ascertainment bias, due to the procedure used to select SNPs [101–106]. The degree of ascertainment bias primarily depends on the size and representativeness of the panel of individuals, in this case the mice, used to select the SNPs. If a panel is chosen from individuals from a subpopulation or geographical region that is not representative of the population as a whole, variability in groups related to the ascertainment group will be over-represented [105].

The ascertainment bias for the GigaMUGA SNP array is both extreme and not uniform, due to the development procedures used to create the array. The GigaMUGA array was designed primarily from laboratory strains of mice, for use in biomedical and developmental genomic research. As the majority of laboratory strains are descended primarily from M. m. domesticus, a large proportion of SNPs will, therefore, be informative only between M. m. domesticus lineages, and monomorphic in the other subspecies. Furthermore, SNPs in the array were selected in a way to minimize mutual information between markers, which has the side effect of eliminating LD signals. This ascertainment bias means that comparing populations with differing proportions of the three subspecies may lead to biases in estimates of nucleotide diversity, population size, demographic changes, LD, selective sweeps and inferences of population structure [107–109]. We specifically chose analyses and data-filtering steps to avoid the effects of the inherent ascertainment bias in the GigaMUGA array, and these methods should be robust to the previously mentioned caveats [106,109]. We caution against using our data to assess other properties such as nucleotide diversity or to identify selective sweeps without careful consideration for appropriate filtering.

4.5. Future directions

Our study is the first looking at the invasion history of wild mice using the GigaMUGA SNP array, and indeed the first to use a high-density SNP array of any kind to assess population genomics of wild mice. Our data are available online (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tm617 [110]) so that researchers, from both ecological and genomic fields, can compare their populations with ours using similar SNP genotyping methods. For regions within the native range of house mice where complex patterns of divergence and introgression have been observed, such as Turkey and Iran [24,111] and across Europe [20], the GigaMUGA array has significant potential to add to our understandings of the genomics of these hybrid zones.

We have not fully addressed the precise origins in the native ranges of the representatives of each subspecies that came to New Zealand, largely due to the paucity and unevenness of wild-mouse samples genotyped across these native ranges. However, these results are consistent with what is known from historic shipping records [54]. Given the standardization of the GigaMUGA array, it should be relatively easy to investigate this in the future, by obtaining and genotyping samples of mice from across the home range—particularly around historically significant ports. Furthermore, using runs of homozygosity, it should be possible to model the demographic history and the effects of the expanding invasion fronts on genomic diversity (e.g. [112]).

New Zealand is currently investigating the use of gene-drive technology [113] to help eradicate mammalian pest species as part of the aspirational ‘Predator Free 2050’ project [114]. Current laboratory proof-of-concept research is proceeding on mice as a model organism, due to their short generation times and the extensive genomic resources available for this species. Our study of wild mice would be informative to this research, as an understanding of the standing variation, spatial structuring and genomic ancestry of wild mice will be vital to informing laboratory work, and could help identify islands where trials or application for this technique could be conducted.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the people who supplied mouse specimens for the previous mtDNA analyses, and to Neil Barton, Anna Clark, Daniel Hurley, Pete McClelland, Peter Banks, John Birchfield, Jean Stanley, Russel and Teresa Trow, Judy Gilbert, Lyndon Slater, Elaine Murphy, John Henderson and Jamie Mackay for newly collected material. Thanks also to Anne Mitchell for sample curation, and to Andrew Morgan and Darla Miller at UNC for their extensive support in the sequencing, filtering and advice for analyses.

Ethics

Tissue samples obtained for this research were either from pre-existing collections or were obtained from pest control contractors.

Data accessibility

The software used in the research can be located as follows:

Plink 1.9: https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2;

argyle: https://github.com/andrewparkermorgan/argyle;

Admixture: https://www.genetics.ucla.edu/software/admixture/download.html;

Tess3r: https://github.com/cayek/TESS3/tree/master/tess3r;

Ape: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ape/index.html.

The reference MUGA data in PLINK format can be obtained at: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.689d2 [45].

All raw genotypic data described in the manuscript have been uploaded as PLINK binary files (.bed, .bim, .fam) to Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tm617) [110].

Authors' contributions

A.V. resampled all the accumulated material stored at Waikato University described by King et al. [55]; extracted and processed all new genetic samples; sent them for processing; analysed the results; and wrote most of the paper. J.R. supplied extra samples from Abel Tasman, Antipodes Is., Auckland Is., Ruapuke Is., Tawharanui, Bay of Islands, Doubtless Bay, Timaru, Pourewa Is. and Lord Howe Is., and commented on the manuscript. C.K. organized the collection and care of the mice since 1999; applied for the funds; and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

Major funding supplied by the University of Waikato Strategic Investment Fund Grant F715 to C.K.

References

- 1.Bonhomme F, Searle JB. 2012. House mouse phylogeography. In Evolution of the house mouse (eds Macholan M, Baird SJE, Munclinger P, Pialek J), pp. 278–298. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boursot P, Auffray JC, Brittondavidian J, Bonhomme F. 1993. The evolution of house mice. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24, 119–152. (doi:10.1146/annurev.es.24.110193.001003) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geraldes A, Basset P, Gibson B, Smith KL, Harr B, Yu H-T, Bulatova N, Ziv Y, Nachman MW. 2008. Inferring the history of speciation in house mice from autosomal, X-linked, Y-linked and mitochondrial genes. Mol. Ecol. 17, 5349–5363. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04005.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geraldes A, Basset P, Smith KL, Nachman MW. 2011. Higher differentiation among subspecies of the house mouse (Mus musculus) in genomic regions with low recombination. Mol. Ecol. 20, 4722–4736. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05285.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White MA, Ane C, Dewey CN, Larget BR, Payseur BA. 2009. Fine-scale phylogenetic discordance across the house mouse genome. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000729 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000729) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keane TM, et al. 2011. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature 477, 289–294. (doi:10.1038/nature10413) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guenet JL, Bonhomme F. 2003. Wild mice: an ever-increasing contribution to a popular mammalian model. Trends Genet. 19, 24–31. (doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00007-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phifer-Rixey M, Nachman MW. 2015. Insights into mammalian biology from the wild house mouse Mus musculus. Elife 4, e05959 (doi:10.7554/eLife.05959) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanlerberghe F, Dod B, Boursot P, Bellis M, Bonhomme F. 1986. Absence of Y-chromosome introgression across the hybrid zone between Mus musculus domesticus and Mus musculus musculus. Genetic Res. 48, 191–197. (doi:10.1017/S0016672300025003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dod B, Jermin LS, Boursot P, Chapman VH, Nielsen JT. 1993. Counterselection on sex-chromosomes in the Mus musculus european hybrid zone. J. Evol. Biol. 6, 529–546. (doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1993.6040529.x) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dod B, Smadja C, Karn R, Boursot P. 2005. Testing for selection on the androgen-binding protein in the Danish mouse hybrid zone. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84, 447–459. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00446.x) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payseur BA, Krenz JG, Nachman MW. 2004. Differential patterns of introgression across the X chromosome in a hybrid zone between two species of house mice. Evolution 58, 2064–2078. (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00490.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raufaste N, Orth A, Belkhir K, Senet D, Smadja C. 2005. Inferences of selection and migration in the Danish house mouse hybrid zone. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84, 593–616. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00457.x) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macholan M, Munclinger P, Sugerkova M, Dufkova P, Bimova B, Bozikova E, Zima J, Pialek J. 2007. Genetic analysis of autosomal and X-linked markers across a mouse hybrid zone. Evolution 61, 746–771. (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00065.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teeter KC, Payseur BA, Harris LW, Bakewell MA, Thibodeau LM. 2008. Genome-wide patterns of gene flow across a house mouse hybrid zone. Genome Res. 18, 67–76. (doi:10.1101/gr.6757907) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teeter KC, Thibodeau LM, Gompert Z, Buerkle CA, Nachman MW. 2010. The variable genomic architecture of isolation between hybridizing species of house mice. Evolution 64, 472–485. (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00846.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LY, et al. 2011. Measures of linkage disequilibrium among neighbouring SNPs indicate asymmetries across the house mouse hybrid zone. Mol. Ecol. 20, 2985–3000. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05148.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janousek V, et al. 2012. Genome-wide architecture of reproductive isolation in a naturally occurring hybrid zone between Mus musculus musculus and M. m. domesticus. Mol. Ecol. 21, 3032–3047. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05583.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones EP, Jóhannesdóttir F, Richards MB, Searle JB. 2011. The expansion of the house mouse into northern-western Europe. J. Zool. 283, 257–268. (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00767.x) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baird SJE, Macholan M. 2012. What can the Mus musculus musculus/M. m. domesticus hybrid zone tell us about speciation? In Evolution of the house mouse (Cambridge studies in morphology and molecules: New paradigms in evolutionary biology) (eds Macholán M, Baird SJE, Munclinger P, Piálek J), pp. 334–372. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orth A, Adama T, Din W, Bonhomme F. 1998. Natural hybridization of two subspecies of house mice, Mus musculus domesticus and Mus musculus castaneus, near Lake Casitas (California). Genome 41, 104–110. (doi:10.1139/gen-41-1-104) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormick H, Cursons R, Wilkins RJ, King CM. 2014. Location of a contact zone between Mus musculus domesticus and M. m. domesticus with M. m. castaneus mtDNA in southern New Zealand. Mamm. Biol. 79, 297–305. (doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2014.05.006) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunduz I, Rambau RV, Tez C, Searle JB. 2005. Mitochondrial DNA variation in the western house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) close to its site of origin: studies in Turkey. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84, 473–485. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00448.x) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardouin EA, Orth A, Teschke M, Darvish J, Tautz D, Bonhomme F. 2015. Eurasian house mouse (Mus musculus L.) differentiation at microsatellite loci identifies the Iranian plateau as a phylogeographic hotspot. BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 26 (doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0306-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamid HS, Darvish J, Rastegar-Pouyani E, Mahmoudi A. 2017. Subspecies differentiation of the house mouse Mus musculus Linnaeus, 1758 in the center and east of the Iranian plateau and Afghanistan. Mammalia 81, 147–168. (doi:10.1515/mammalia-2015-0041) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terashima M, Furusawa S, Hanzawa N, Tsuchiya K, Suyanto A, Moriwaki K, Yonekawa H, Suzuki H. 2006. Phylogeographic origin of Hokkaido house mice (Mus musculus) as indicated by genetic markers with maternal, paternal and biparental inheritance. Heredity 96, 128–138. (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800761) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forejt J. 1996. Hybrid sterility in the mouse. Trends Genet. 12, 412–417. (doi:10.1016/0168-9525(96)10040-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britton-Davidian J, Fel-Clair F, Lopez J, Alibert P, Boursot P. 2005. Postzygotic isolation between the two European subspecies of the house mouse: estimates from fertility patterns in wild and laboratory-bred hybrids. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84, 379–393. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00441.x) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihola O, Trachtulec Z, Vlcek C, Schimenti JC, Forejt J. 2009. A mouse speciation gene encodes a meiotic histone H3 methyltransferase. Science 323, 373–375. (doi:10.1126/science.1163601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White MA, Steffy B, Wiltshire T, Payseur BA. 2011. Genetic dissection of a key reproductive barrier between nascent species of house mice. Genetics 189, 289–304. (doi:10.1534/genetics.111.129171) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White MA, Stubbings M, Dumont BL, Payseur BA. 2012. Genetics and evolution of hybrid male sterility in house mice. Genetics 191, 917 (doi:10.1534/genetics.112.140251) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner LM, Harr B. 2014. Genome-wide mapping in a house mouse hybrid zone reveals hybrid sterility loci and Dobzhansky-Muller interactions. Elife 3, e02504 (doi:10.7554/eLife.02504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker PK, Sage RD, Warner J, Wilson AC, Eicher EM. 1992. Abrupt cline for sex-chromosomes in a hybrid zone between 2 species of mice. Evolution 46, 1146–1163. (doi:10.2307/2409762) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oka A, Mita A, Sakurai-Yamatani N, Yamamoto H, Takagi N, Takano-Shimizu T, Toshimori K, Moriwaki K, Shiroishi T. 2004. Hybrid breakdown caused by substitution of the X chromosome between two mouse subspecies. Genetics 166, 913–924. (doi:10.1534/genetics.166.2.913) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storchova R, Gregorova S, Buckiova D, Kyselova V, Divina P, Forejt J. 2004. Genetic analysis of X-linked hybrid sterility in the house mouse. Mamm. Genome 15, 515–524. (doi:10.1007/s00335-004-2386-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Good JM, Giger T, Dean MD, Nachman MW. 2010. Widespread over-expression of the X chromosome in sterile F-1 hybrid mice. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001148 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001148) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Good JM, Dean MD, Nachman MW. 2008. A complex genetic basis to X-linked hybrid male sterility between two species of house mice. Genetics 179, 2213–2228. (doi:10.1534/genetics.107.085340) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oka A, Shiroishi T. 2012. The role of the X chromosome in house mouse speciation. In Evolution of the house mouse (eds Macholan M, Baird SJE, Munclinger P, Pialek J), pp. 431–454. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calaway JD, Lenarcic AB, Didion JP, Wang JR, Searle JB, McMillan L, Valdar W, de Villena FP-M. 2013. Genetic architecture of skewed X inactivation in the laboratory mouse. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003853 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003853) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oka A, et al. 2007. Disruption of genetic interaction between two autosomal regions and the X chromosome causes reproductive isolation between mouse strains derived from different subspecies. Genetics 175, 185–197. (doi:10.1534/genetics.106.062976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker CL, Kajita S, Walker M, Saxl RL, Raghupathy N, Choi K, Petkov PM, Paigen K. 2015. PRDM9 drives evolutionary erosion of hotspots in Mus musculus through haplotype-specific initiation of meiotic recombination. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004916 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004916) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phifer-Rixey M, Bomhoff M, Nachman MW. 2014. Genome-wide patterns of differentiation among house mouse subspecies. Genetics 198, 283 (doi:10.1534/genetics.114.166827) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frazer KA, et al. 2007. A sequence-based variation map of 8.27 million SNPs in inbred mouse strains. Nature 448, 1050–1053. (doi:10.1038/nature06067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Bell TA, Churchill GA, de Villena FP-M. 2007. On the subspecific origin of the laboratory mouse. Nat. Genet. 39, 1100–1107. (doi:10.1038/ng2087) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan AP, et al. 2016. The mouse universal genotyping array: from substrains to subspecies G3-Genes Genomes Genetics 6, 263–279. (doi:10.1534/g3.115.022087) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu EY, Morgan AP, Chesler EJ, Wang W, Churchill GA, de Villena FP-M. 2014. High-resolution sex-specific linkage maps of the mouse reveal polarized distribution of crossovers in male germline. Genetics 197, 91–106. (doi:10.1534/genetics.114.161653) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berry RJ, Scriven PN. 2005. The house mouse: a model and motor for evolutionary understanding. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84, 335–347. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00438.x) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Searle JB, Jamieson PM, Gunduz I, Stevens MI, Jones EP, Gemmill CEC, King CM. 2009. The diverse origins of New Zealand house mice. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 209–217. (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0959) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabriel SI, Stevens MI, Mathias MD, Searle JB. 2011. Of mice and ‘convicts’: origin of the Australian house mouse, Mus musculus. PLoS ONE 6, 10028622 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabriel SI, Mathias ML, Searle JB. 2015. Of mice and the ‘Age of Discovery': the complex history of colonization of the Azorean archipelago by the house mouse (Mus musculus) as revealed by mitochondrial DNA variation. J. Evol. Biol. 28, 130–145. (doi:10.1111/jeb.12550) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones EP, Eager HM, Gabriel SI, Johannesdottir F, Searle JB. 2013. Genetic tracking of mice and other bioproxies to infer human history. Trends Genet 29, 298–308. (doi:10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones EP, Skirnisson K, McGovern TH, Gilbert MTP, Willerslev E, Searle JB. 2012. Fellow travellers: a concordance of colonization patterns between mice and men in the North Atlantic region. BMC Evol. Biol. 12, 35 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-35) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilmshurst JM, Anderson AJ, Higham TFG, Worthy TH. 2008. Dating the prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal pacific rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7676–7680. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0801507105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.King CM. 2016. How genetics, history and geography limit potential explanations of invasions by house mice Mus musculus in New Zealand. Biol. Invasions 18, 1533–1550. (doi:10.1007/s10530-016-1099-0) [Google Scholar]

- 55.King C, Alexander A, Chubb T, Cursons R, MacKay J, McCormick H, Murphy E, Veale A, Zhang H. 2016. What can the geographic distribution of mtDNA haplotypes tell us about the invasion of New Zealand by house mice Mus musculus? Biol. Invasions 18, 1551–1565. (doi:10.1007/s10530-016-1100-y) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgan AP, Welsh CE. 2015. Informatics resources for the collaborative cross and related mouse populations. Mamm. Genome 26, 521–539. (doi:10.1007/s00335-015-9581-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan AP. 2015. argyle: An R package for analysis of illumina genotyping arrays. G3 6, 281–286. (doi:10.1534/g3.115.023739) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier L, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. 2015. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7 (doi:10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raj A, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. 2014. fastSTRUCTURE: variational inference of population structure in large SNP Data Sets. Genetics 197, 573 (doi:10.1534/genetics.114.164350) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falush D, van Dorp L, Lawson DJ. 2016. A tutorial on how (not) to over-interpret Structure/Admixture bar plots. bioRxiv preprint. (http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/066431) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caye K, Deist TM, Martins H, Michel O, Francois O. 2016. TESS3: fast inference of spatial population structure and genome scans for selection. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 540–548. (doi:10.1111/1755-0998.12471) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. 2004. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang H, et al. 2011. Subspecific origin and haplotype diversity in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Genet. 43, 648 (doi:10.1038/ng.847) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Puckett EE, et al. 2016. Global population divergence and admixture of the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20161762 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1762) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wirtz P. 1999. Mother species--father species: unidirectional hybridization in animals with female choice. Anim. Behav. 58, 1–12. (doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1144) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGuire JA, Linkem CW, Koo MS, Hutchison DW, Lappin AK, Orange DI, Lemos-Espinal J, Riddle BR, Jaeger JR. 2007. Mitochondrial introgression and incomplete lineage sorting through space and time: pylogenetics of crotaphytid lizards. Evolution 61, 2879–2897. (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00239.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Good JM, Hird S, Reid N, Demboski JR, Steppan SJ, Martin-Nims TR, Sullivan J. 2008. Ancient hybridization and mitochondrial capture between two species of chipmunks. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1313–1327. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03640.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tang QY, Liu SQ, Yu D, Liu HZ, Danley PD. 2012. Mitochondrial capture and incomplete lineage sorting in the diversification of balitorine loaches (Cypriniformes, Balitoridae) revealed by mitochondrial and nuclear genes. Zool. Scr. 41, 233–247. (doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2011.00530.x) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cathey JC, Bickham JW, Patton JC. 1998. Introgressive hybridization and nonconcordant evolutionary history of maternal and paternal lineages in North American deer. Evolution 52, 1224–1229. (doi:10.2307/2411253) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ropiquet A, Hassanin A. 2006. Hybrid origin of the Pliocene ancestor of wild goats. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 41, 395–404. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thulin CG, Jaarola M, Tegelstrom H. 1997. The occurrence of mountain hare mitochondrial DNA in wild brown hares. Mol. Ecol. 6, 463–467. (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.t01-1-00199.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thulin CG, Tegelstrom H. 2002. Biased geographical distribution of mitochondrial DNA that passed the species barrier from mountain hares to brown hares (genus Lepus): an effect of genetic incompatibility and mating behaviour? J. Zool. 258, 299–306. (doi:10.1017/s0952836902001425) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melo-Ferreira J, Boursot P, Suchentrunk F, Ferrand N, Alves PC. 2005. Invasion from the cold past: extensive introgression of mountain hare (Lepus timidus) mitochondrial DNA into three other hare species in northern Iberia. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2459–2464. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02599.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ruedi M, Smith MF, Patton JL. 1997. Phylogenetic evidence of mitochondrial DNA introgression among pocket gophers in New Mexico (family Geomyidae). Mol. Ecol. 6, 453–462. (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00210.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tegelstrom H. 1987. Transfer of mitochondrial-DNA from the northern red-backed vole (Clethrionomys rutilus) to the bank vole (C. glareolus). J. Mol. Evol. 24, 218–227. (doi:10.1007/bf02111235) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Markova S, Dufresne F, Manca M, Kotlik P. 2013. Mitochondrial capture misleads about ecological speciation in the Daphnia pulex complex. PLoS ONE 8, e0069497 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069497) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferris SD, Sage RD, Huang CM, Nielsen JT, Ritte U, Wilson AC. 1983. Flow of mitochondrial-DNA across a species boundary. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 80, 2290–2294. (doi:10.1073/pnas.80.8.2290) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Prager EM, Sage RD, Gyllensten U, Thomas WK, Hubner R, Jones CS, Noble L, Searle JB, Wilson AC. 1993. Mitochondrial-DNA sequence diversity and the colonization of Scandinavia by house mice from East Holstein. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 50, 85–122. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1993.tb00920.x) [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chan KMA, Levin SA. 2005. Leaky prezygotic isolation and porous genomes: rapid introgression of maternally inherited DNA. Evolution 59, 720–729. (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01748.x) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Churchill G, et al. 2004. The collaborative cross, a community resource for the genetic analysis of complex traits. Nat. Genet. 36, 1133–1137. (doi:10.1038/ng1104-1133) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shorter JR, et al. 2017. Male infertility is responsible for nearly half of the extinction observed in the mouse collaborative cross. Genetics 206, 557–572. (doi:10.1534/genetics.116.199596) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hammer MF, Wilson AC. 1987. Regulatory and structural genes for lysozymes of mice. Genetics 115, 521–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krzanowska H, Lorenc E. 1983. Influence of egg investments on in-vitro penetration of mouse eggs by misshapen spermatozoa. J. Reprod. Fertil. 68, 57 (doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0680057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Styrna J. 2008. Genetic control of gamete quality in the mouse - a tribute to Halina Krzanowska. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 52, 195–199. (doi:10.1387/ijdb.072328js) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Forejt J, Ivanyi P. 1974. Genetic studies on male sterility of hybrids between laboratory and wild mice (Mus musculus L). Genet. Res. 24, 189–206. (doi:10.1017/S0016672300015214) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ramalhinho MD, Auffray JC, Nunes AC, Gazave E, Searle JB, Mathias MD. 2005. Chromosomal phylogeny of Robertsonian races of the house mouse on the island of Madeira: testing between alternative mutational processes. Genet. Res. 86, 171–183. (doi:10.1017/s0016672305007809) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Lopez J, Ganem G, Nunes AC, Ramalhinho MG, Auffray JC, Searle JB, Mathias ML. 2007. Patterns of genic diversity and structure in a species undergoing rapid chromosomal radiation: an allozyme analysis of house mice from the Madeira archipelago. Heredity 99, 432–442. (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6801021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nunes AC, Catalan J, Lopez J, Ramalhinho MD, Mathias MD, Britton-Davidian J. 2011. Fertility assessment in hybrids between monobrachially homologous Rb races of the house mouse from the island of Madeira: implications for modes of chromosomal evolution. Heredity 106, 348–356. (doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.74) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nunes AC, Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ramalhinho MG, Capela R, Mathias ML, Ganem G. 2005. Influence of physical environmental characteristics and anthropogenic factors on the position and structure of a contact zone between two chromosomal races of the house mouse on the island of Madeira (North Atlantic, Portugal). J. Biogeogr. 32, 2123–2134. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01337.x) [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gunduz I, Auffray JC, Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ganem G, Ramalhinho MG, Mathias ML, Searle JB. 2001. Molecular studies on the colonization of the Madeiran archipelago by house mice. Mol. Ecol. 10, 2023–2029. (doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01346.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Berry RJ. 2009. Evolution rampant: house mice on Madeira. Mol. Ecol. 18, 4344–4346. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04345.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Forster DW, Gunduz I, Nunes AC, Gabriel S, Ramalhinho MG, Mathias ML, Britton-Davidian J, Searle JB. 2009. Molecular insights into the colonization and chromosomal diversification of Madeiran house mice. Mol. Ecol. 18, 4477–4494. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04344.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Forster DW, Mathias ML, Britton-Davidian J, Searle JB. 2013. Origin of the chromosomal radiation of Madeiran house mice: a microsatellite analysis of metacentric chromosomes. Heredity 110, 380–388. (doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jones CS, Noble LR, Jones JS, Tegelstrom H, Triggs GS, Berry RJ. 1995. Differential male genetic success determines gene flow in an experimentally manipulated mouse population. Proc. R. Soc. B 260, 251–256. (doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Russell JC. 2012. Spatio-temporal patterns of introduced mice and invertebrates on Antipodes Island. Polar Biol. 35, 1187–1195. (doi:10.1007/s00300-012-1165-8) [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taylor R. 2006. Straight through from London: the Antipodes and Bounty Islands, New Zealand. Christchurch, New Zealand: Heritage Expeditions. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eden AW. 1955. Islands of despair: being an account of a survey expedition to the sub-Antarctic islands of New Zealand. London, UK: Andrew Melrose. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Waite ER. 1909. Vertebrata of the subantarctic islands of New Zealand. In The subantarctic islands of New Zealand (ed. Chilton C.), pp. 542–600. Wellington, New Zealand: Philosophical Institute of Canterbury. [Google Scholar]

- 99.McNab R. 1908. Historical records of New Zealand, vol 1 Wellington, New Zealand: Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Richards R. 2010. Sealing in the southern oceans 1788 to 1833. Wellington, New Zealand: Paramata Press. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nielsen R. 2000. Estimation of population parameters and recombination rates from single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genetics 154, 931–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kuhner MK, Beerli P, Yamato J, Felsenstein J. 2000. Usefulness of single nucleotide polymorphism data for estimating population parameters. Genetics 156, 439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eller E. 2001. Effects of ascertainment bias on recovering human demographic history. Hum. Biol. 73, 411–427. (doi:10.1353/hub.2001.0034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Clark AG, Hubisz MJ, Bustamante CD, Williamson SH, Nielsen R. 2005. Ascertainment bias in studies of human genome-wide polymorphism. Genome Res. 15, 1496–1502. (doi:10.1101/gr.4107905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]