Abstract

Loss of proteostasis underlies aging and neurodegeneration characterized by the accumulation of protein aggregates and mitochondrial dysfunction1–5. Although many neurodegenerative-disease proteins can be found in mitochondria4,6, it remains unclear how these disease manifestations may be related. In yeast, protein aggregates formed under stress or during aging are preferentially retained by the mother cell in part through tethering to mitochondria, while the disaggregase Hsp104 helps dissociate aggregates to enable refolding or degradation of misfolded proteins7–10. Here we show that in yeast cytosolic proteins prone to aggregation are imported into mitochondria for degradation. Protein aggregates formed under heat shock (HS) contain both cytosolic and mitochondrial proteins and interact with mitochondrial import complex. Many aggregation-prone proteins enter mitochondrial intermembrane space and matrix after HS, while some do so even without stress. Timely dissolution of cytosolic aggregates requires mitochondrial import machinery and proteases. Blocking mitochondrial import but not the proteasome activity causes a marked delay in the degradation of aggregated proteins. Defects in cytosolic Hsp70s leads to enhanced entry of misfolded proteins into mitochondria and elevated mitochondrial stress. We term this mitochondria-mediated proteostasis mechanism MAGIC (mitochondria as guardian in cytosol) and provide evidence that it may exist in human cells.

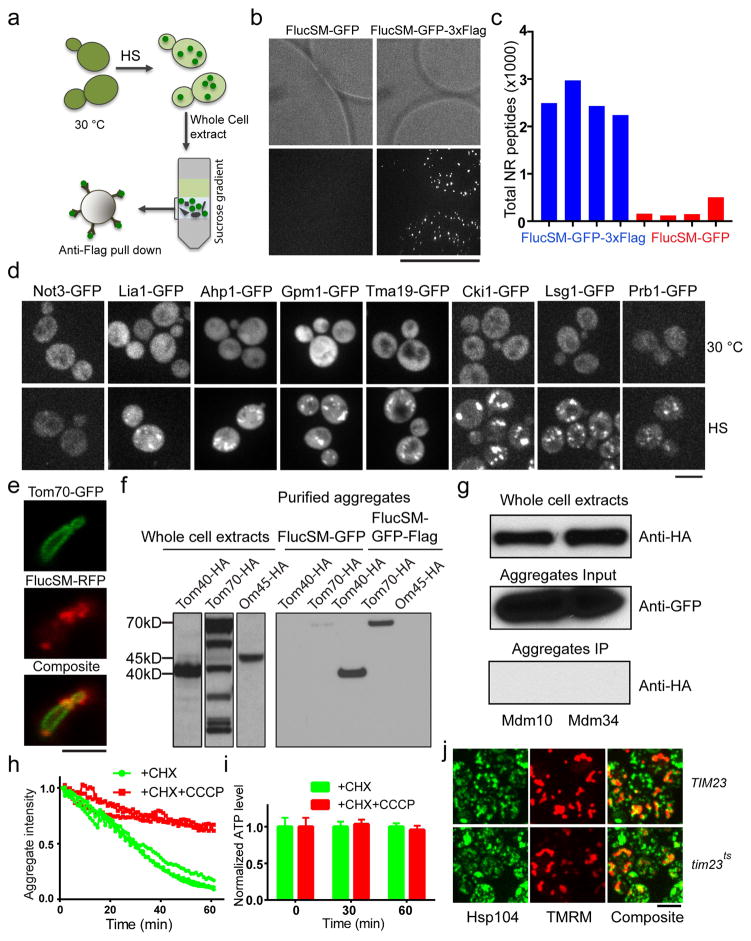

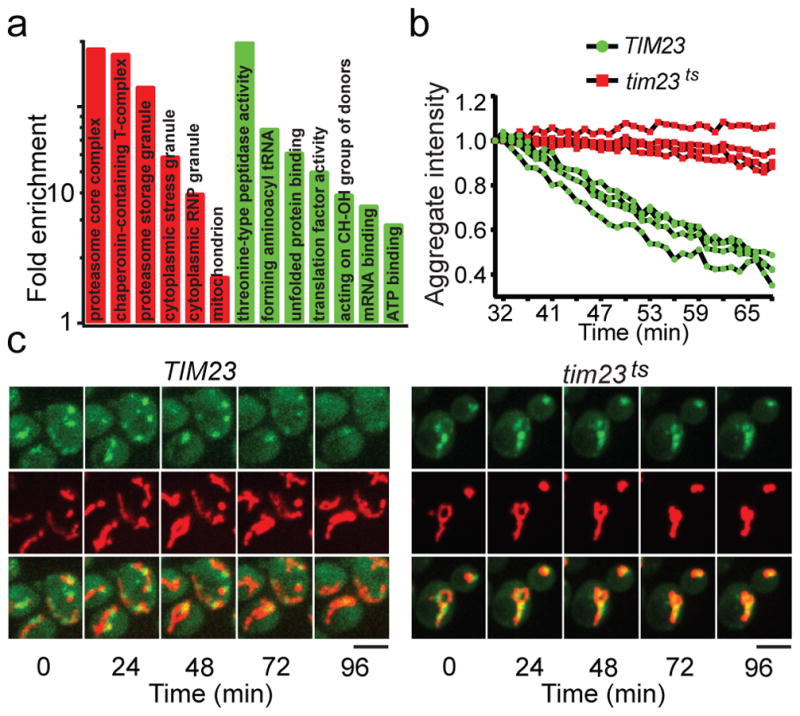

We developed an affinity-based method, using GFP and Flag-tagged luciferase (FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag), a model aggregation substrate11, to purify protein aggregates induced by HS and identify their components by quantitative Multi-Dimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) comparing the experimental strain with the control lacking the Flag tag (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b,c). 319 proteins were found to enrich significantly in HS-induced aggregates (Table S1, S2). These proteins are referred to as aggregate proteins (APs) hereafter. 45% of APs were observed to form visible aggregates after HS by using available GFP-tagged strains (Extended Data Fig. 1d). 18% APs found in our study overlap with those identified previously using differential centrifugation12. Gene ontology revealed significant enrichment in proteasome components, chaperones, RNA-binding proteins, stress granules, and mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 1a).

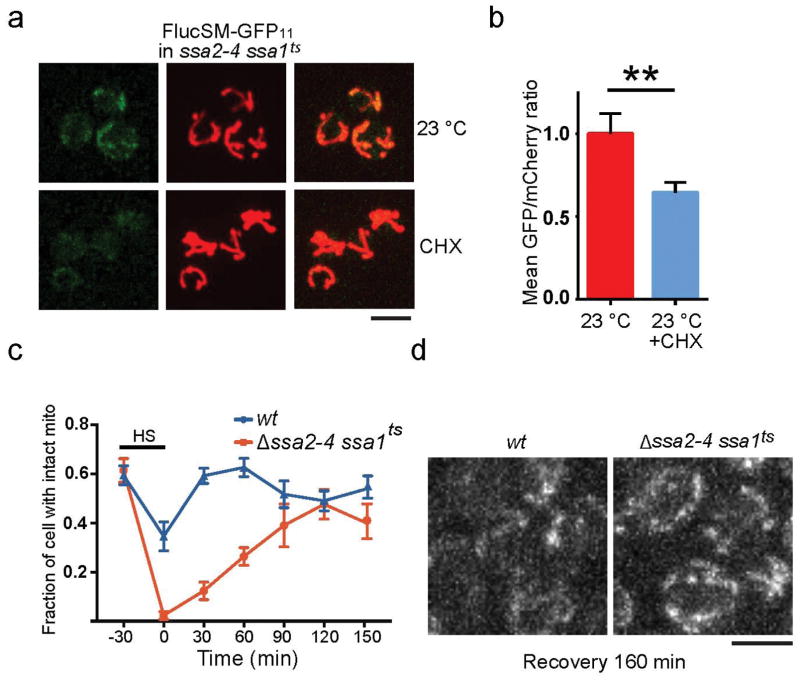

Figure 1. HS aggregates and mitochondrial import.

a, GO enrichment of APs. Green: molecular function; red: cellular components. b, Aggregates, labeled with Hsp104-GFP dissolution in TIM23 (green) or tim23ts cells (red). Shown are fluorescence traces from 3 biological repeats. c, Montage of movies used in (b). Top: aggregates; middle: mitochondria; bottom: merged. Scale bars: 5 μm.

Tom70 and Tom40, two mitochondrial outer membrane (OM) proteins involved in import13, were among the mitochondrial proteins co-purified with aggregates. Microscopy revealed Tom70-GFP to be evenly distributed on mitochondrial membrane rather than colocalizing with aggregates (Extended Data Fig. 1e), but the biochemical interaction of Tom70 and Tom40 with aggregates was verified (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g). We showed previously that chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), which disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential required for import14, but not antimycin, which blocks mitochondrial ATP production, prevented the dissolution of Hsp104-GFP-labeled aggregates9. CCCP also disrupted dissolution of FlucSM-GFP aggregates in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX), without depleting cellular ATP (Extended Data Fig. 1h,i)15,16. We therefore hypothesized that aggregate dissolution involves import of APs into mitochondria. To test this, we compared dissolution kinetics of HS aggregates in wild type (wt) or tim23ts, a temperature-sensitive mutant of TIM23, encoding a subunit of the mitochondrial inner-membrane (IM) import complex13,17. tim23ts was inactivated during HS and prevented aggregate dissolution after shifting back to 23 °C in the presence of CHX (Fig. 1b–c), and this delay was not due to disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential (Extended Data Fig. 1j).

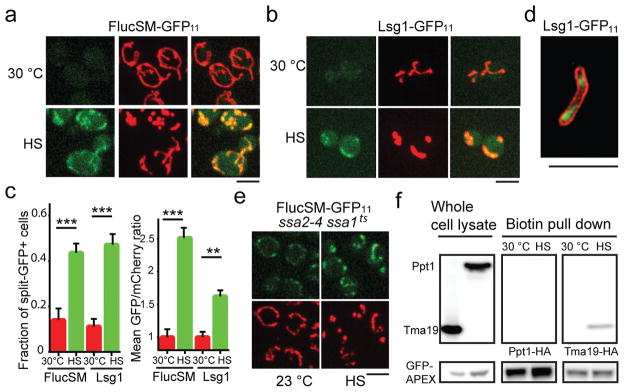

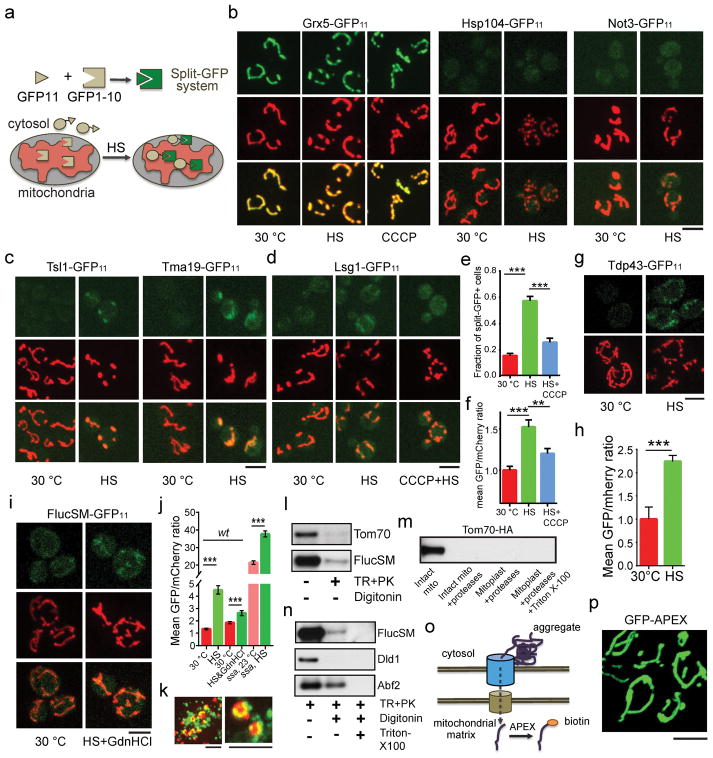

To visualize the entry of APs into mitochondria, we employed the split GFP system18 where the first 10 β strands of GFP (GFP1-10), linked with mCherry, was targeted to mitochondria through linkage with a mitochondria-targeting sequence19 (MTS-mCherry-GFP1-10), while the 11th β strand (GFP11) was linked with an AP (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Mitochondrial GFP fluorescence was only expected if the latter entered mitochondria. For positive and negative controls, GFP11-tagged Grx5, a mitochondrial matrix protein, showed prominent mitochondrial split-GFP signal, whereas GFP11-tagged Hsp104 or non-aggregate cytosolic protein Not3 (Extended Data Fig. 1d) showed no mitochondrial split-GFP signal with or without HS (Extended Data Fig. 2b). GFP11-tagged APs, including FlucSM and several native APs, showed no or low-level mitochondrial GFP fluorescence before HS, but after HS the mitochondrial split-GFP signal increased dramatically (Fig. 2a–c; Extended Data Fig. 2c), and this increase could be prevented by CCCP (Extended Data Fig. 2d–f). Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) applied to a strain, in which mitochondrial OM was labeled with Fis1TM-mCherry9 and GFP1-10 was targeted into mitochondria by linking to Grx5, confirmed that the split GFP signal was indeed inside mitochondria (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Video 1). Mitochondrial import under HS was also observed for TDP-43 expressed in yeast, a protein associated with several forms of neurodegeneration20 (Extended Data Fig. 2g,h). Interestingly, Δssa2,3,4 ssa1ts mutations21 disrupting cytosolic Hsp70 proteins led to import of FlucSM with or without HS (Fig. 2e), whereas disrupting Hsp104 activity with GdnHCl22 reduced the amount of imported FlucSM-GFP11 (Extended Data Fig. 2i,j), suggesting that Hsp104 but not Hsp70s is involved in mitochondrial import of APs.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial import of aggregate proteins.

a,b, Images of cells expressing FlucSM-GFP11 (a) and Lsg1-GFP11 (b). Left panels: split GFP; middle: mitochondria; right: merged. c, Fractions of split-GFP+ cells and normalized mean GFP/mCherry ratio from experiments in (a) and (b). Shown: means and SEM of, left to right, 209, 215, 252 and 235 (left graph) and 145, 147, 111 and 133 (right graph) cells imaged and quantified; 3 biological repeats. d, Merged SIM images after HS. Green: Lsg1 split GFP; red: mCherry-Fis1TM. 3 biological repeats. 21 cells imaged. e, Images with FlucSM-GFP11 split-GFP (top) and mitochondria (bottom). Quantification in Extended Data Fig. 2j. 3 biological repeats. f, Anti-HA immunoblot of whole-cell lysate and proteins biotinylated by MTS-GFP-APEX2. Unpaired two-tailed t test for c: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Scale bars, 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

To biochemically examine the import of APs into mitochondria, mitochondria were purified from cells expressing FlucSM-HA after HS. Sequential trypsin and protease K treatments were used to eliminate the substantial amount of aggregates attached to the outside of mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 2k–m). Mitochondrial OM and IM were permeabilized with digitonin or Triton X-100, respectively23,24. Immunoblots of FlucSM, and markers of OM (Tom70), intermembrane space (Dld1) and matrix (Abf2) revealed FlucSM to be present in both intermembrane space and matrix (Extended Data Fig. 2l–n). As an alternative method, MTS-GFP-APEX2 (Extended Data Fig. 2o,p) was introduced into the strain with a native AP, Tma19, tagged with HA at its genomic locus. After cell permeabilization, the mitochondrial matrix was briefly biotinylated, followed by extensive washes, removal of mitochondrial inner membrane and affinity purification of biotinylated proteins. AP protein Tma19-HA, but not the control (HA-tagged cytosolic Ppt1), was detected among the biotinylated proteins after but not before HS (Fig. 2f).

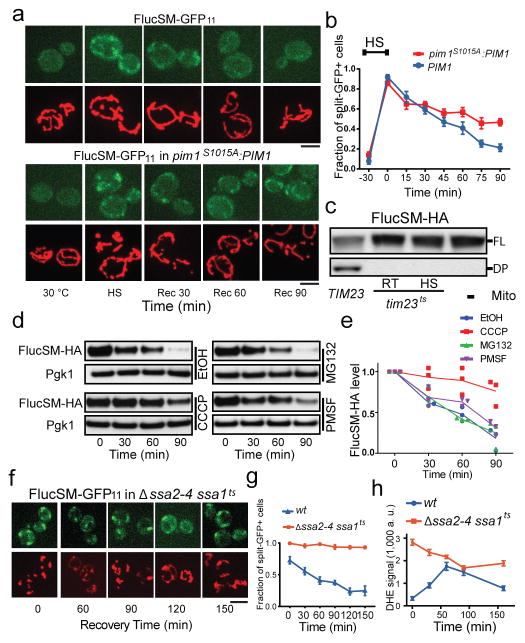

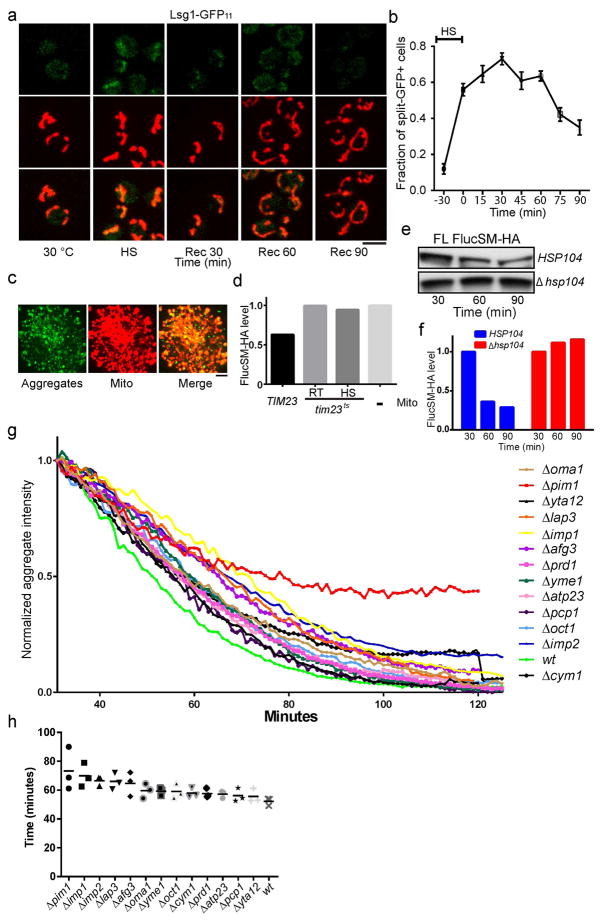

During recovery at normal temperature after HS, the split-GFP signal of APs in mitochondria disappeared with kinetics similar to the dissolution of cytosolic aggregates (Fig. 3a,b, Extended Data Fig. 3a,b, compared to Fig. 1b), suggesting that degradation of APs imported into mitochondria accompanied aggregate dissolution. To test this biochemically, aggregates purified from the strain expressing FlucSM-HA-GFP-3xFlag were incubated with protease inhibitors and purified mitochondria (labeled with mCherry). As expected, aggregates and mitochondria clustered together (Extended Data Fig. 3c). FlucSM-HA-GFP-3xFlag degradation was observed after 1.5-hour incubation, as shown by the marked decrease of the full-length protein accompanied by the appearance of a cleavage product, in the reactions with wt mitochondria, but not those without mitochondria or when mitochondria from tim23ts mutant were used (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 3d). Furthermore, FlucSM-HA-GFP-3xFlag in aggregates purified from the Δhsp104 strain was not degraded by wt mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). This result confirmed that degradation of FlucSM in aggregates required import-competent mitochondria and Hsp104.

Figure 3. Degradation of aggregate proteins in mitochondria.

a,b, Images (a) and quantification (b) of FlucSM-GFP11 split-GFP signal in wt (top set) and pim1S1015A:PIM1 (bottom set) during recovery after HS. Bottom panels in each show mitochondria. Shown in (b): mean and SEM of 1643 (wt) and 1805 (pim1S1015A:PIM1) cells imaged and quantified; 3 biological repeats. c, Immunoblots of FlucSM-HA after aggregates incubated for 90 min with or without TIM23 or tim23ts mitochondria as indicated. RT: room temperate; FL: full length; DP: degradation product. d,e, Immunoblots (d) and quantification (e), showing data points and mean plots from 3 biological repeats, of FlucSM-HA degradation in vivo in the presence of indicated agents. f,g, Images (f, organized as in a) and quantification (g) of FlucSM split-GFP signal in ssa1tsΔssa2-4 during recovery after HS. Shown in (g): mean and SEM of 244, 253, 295, 163, 196 and 209 mutant and 174, 218, 221, 197, 203 and 280 wt cells imaged and quantified; 3 biological repeats. h, Quantification of DHE (ROS). Shown: mean and SEM of 1621 (mutant) and 2151 (wt) cells imaged and quantified; 2 biological repeats. Scale bars, 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

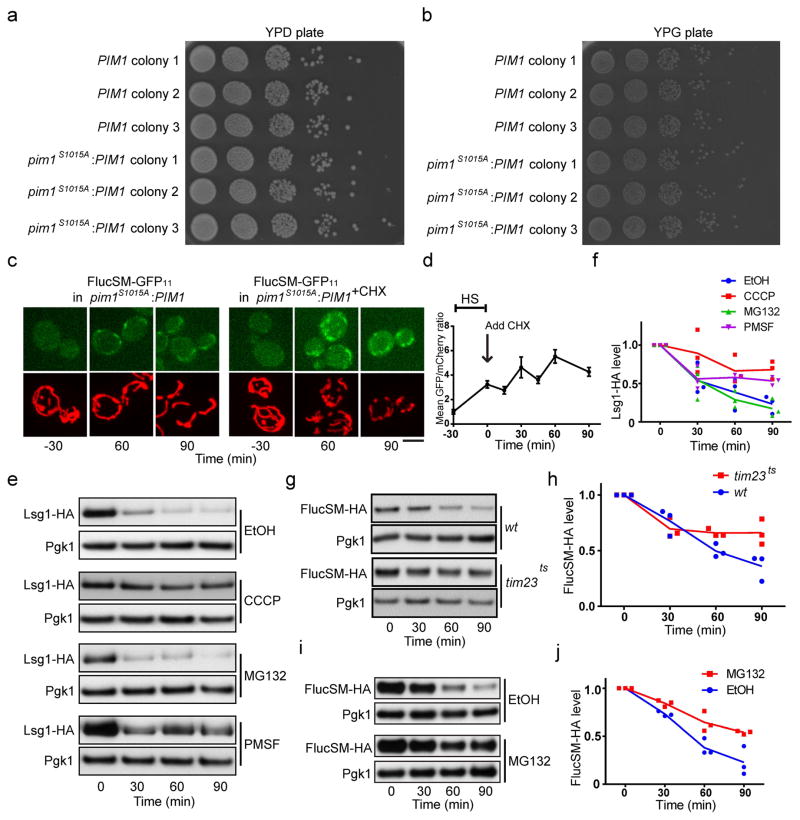

We next screened the 13 non-essential mitochondrial proteases, processing peptidases or oligopeptidases25 for their effect on the dissolution of HS aggregates. Deletion of PIM1, encoding a LON protease showed the strongest inhibitory effect (Extended Data Fig. 3g,h). To test the role of Pim1 further, we introduced into the genome the pim1S1015A mutation, which disrupts Pim1’s proteolytic activity26. This mutant showed normal mitochondrial morphology and growth (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 4a–b), but the disappearance of FlucSM split-GFP signal in mitochondria during recovery was delayed compared to wt cells without or with CHX that prevented further production of APs9 (Fig. 3a, b; Extended Data Fig. 4c, d).

To estimate the contribution of mitochondrial import to the turnover of APs relative to other mechanisms, we compared the degradation kinetics of FlucSM-HA, as well as Lsg1-HA, after HS in the presence of CHX combined with MG132 (inhibiting proteasome), PMSF (inhibiting serine proteases in the vacuole), or CCCP, in the Δpdr5 strain with enhanced drug permeability27,28. CCCP strongly delayed the degradation of FlucSM and Lsg1 after HS (Fig. 3d, e and Extended Data Fig. 4e, f). Consistently, inhibition of import with tim23ts also delayed FlucSM turnover after HS (Extended Data Fig. 4g, h). By contrast, MG132 had little effect on AP degradation after HS, even though the drug efficacy was confirmed by the inhibition of FlucSM degradation without HS (Extended Data Fig. 4i, j). PMSF moderately slowed down the degradation of Lsg1 and FlucSM. This experiment shows a substantial contribution of mitochondrial import to the degradation of APs after HS, while a lack of requirement for proteasome is consistent with the observation that many proteasome components were enriched in aggregates after HS (Fig. 1a).

We next tested the effect of loss of cytosolic proteostasis in Δssa2,3,4 ssa1ts mutant on AP clearance inside mitochondria. The split GFP signal in this mutant persisted after shifting back to 23°C (Fig. 3f, g), likely due to continuous flow of misfolded FlucSM-GFP11 into mitochondria, since CHX treatment enabled split-GFP-signal decay (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). Interestingly, this mutant also displayed much more severe and persistent fragmentation of mitochondria (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5c) and high-level mitochondrial reactive oxidative species (ROS) compared to wt cells after HS (Fig. 3h, Extended Data Fig. 5d). These manifestations of mitochondrial stress were also observed in neurodegenerative diseases1,4,29.

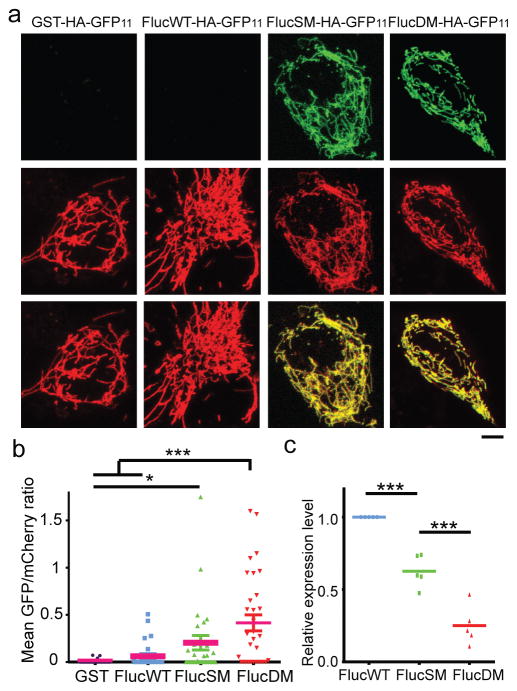

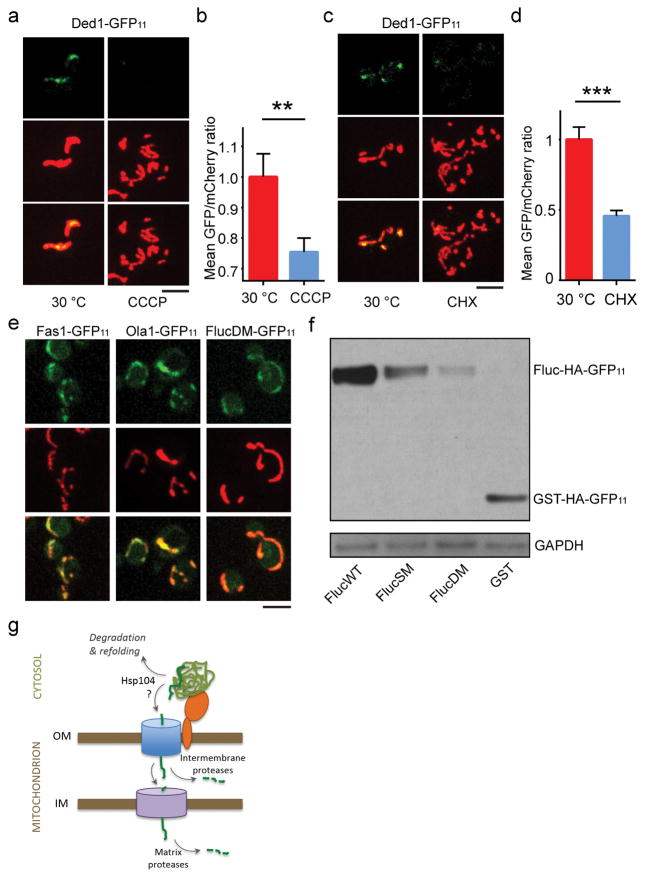

Although mitochondrial import of most APs tested occurred after HS, some, such as Ded1, a RNA helicase, showed prominent split-GFP signal in mitochondria even without HS (Extended Data Fig. 6a–d, and e for additional examples). Ded1 was previously classified as a super aggregator with low stress threshold for aggregation12. After CCCP was added to prevent further import or CHX to prevent further synthesis, the split-GFP signal of Ded1, but not of the stable mitochondrial protein Grx5, diminished with time (Extended Data Fig. 6a–d, 2b), suggesting that highly unstable cytosolic proteins are imported into and degraded in mitochondria even under physiological conditions. To test if import of aggregation-prone proteins into mitochondria occurs in mammalian cells, we fused HA-GFP11 to luciferase (FlucWT), and two mutants, FlucSM and FlucDM, of which FlucDM has the highest structural instability11. Each construct, or GST-HA-GFP11 as another control for stable protein, was co-transfected with a plasmid expressing MTS-mCherry-GFP1-10 into human RPE1 cells. GST-HA-GFP11 or FlucWT-HA-GFP11 produced no or minimal split-GFP fluorescence, whereas FlucSM-HA-GFP11 and FlucDM-HA-GFP11 showed increasingly strong split-GFP fluorescence in mitochondria (Fig. 4a, b), even though the protein levels of FlucWT, FlucSM and FlucDM were in a decreasing order due to instability of the mutants11 (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 6f), suggesting that unstable aggregation-prone cytosolic proteins are also imported into mitochondria in human cells.

Figure 4. Mitochondrial import of unstable proteins in RPE cells.

a, Images of mitochondria (middle) and split-GFP (top) of GFP11-taged proteins in RPE1 cells. Bottom: merged. b, Quantification of normalized GFP/mCherry ratio in a field. Pink line: mean; 34, 26, 39 and 32 fields quantified. Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, none parametric. 3 biological repeats. c, Expression level of Luciferase proteins normalized to FlucWT. Shown: data points and mean of 5 biological repeats. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: ***P<0.001; *P<0.05. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Taken together, we speculate that protein aggregates engaged with mitochondria via interaction with import receptors such as Tom70, leading to import of APs followed by degradation by mitochondrial proteases such as Pim1 (Extended Data Fig. 6g). Import of APs appears not to require cytosolic Hsp70, but Hsp104 is involved, possibly by dissociating proteins from aggregates to enable their entry into import channels. Since blocking mitochondrial import prevented dissaggregation in vivo, the mitochondrial import process may facilitate disaggregation by actively removing dissociated proteins from aggregates although we cannot rule out an indirect effect. While mechanistic details require further investigation, our findings establish mitochondria as an important guardian of cytosolic proteostasis and we term this mechanism MAGIC. In yeast, MAGIC appears to be crucial for the turnover of proteins that aggregate under stress. If this also happens in human cells, it could suggest the accumulation of certain disease proteins in mitochondria4 to reflect a general deficiency in cellular proteostasis30. A resulting overabundance of disease or misfolded proteins inside mitochondria could disrupt mitochondrial biosynthetic activities or overwhelm mitochondria’s own proteostasis, leading to organelle dysfunction. On the other hand, the decline of mitochondrial fitness in aging or disease could lead to diminished MAGIC due to loss of membrane potential or protein degradation capacity, leading to impeded cytosolic proteostasis and buildup of protein aggregates.

Methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

Yeast strains used in this study are based on the BY4741 background as listed in Table S3. ssa1ts strain was a gift from Dr. Elizabeth Craig’s lab (University of Wisconsin, Madison). tim23ts was a gift from Dr. Patrick Silva’s lab (Indian Institute of Science). Gene deletion, HA, GFP11 and GFP tagging were performed with PCR mediated homologous recombination31 and correct integrations were confirmed by PCR. pim1S1015A:PIM1 was constructed by integration of plasmid carries pim1S1015A under PIM1 promotor into PIM1 locus. Plasmids containing FlucWT, FlucSM and FlucDM were constructed using the plasmids kindly provided by Dr. Franz-Ulrich Hartl (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry)32. pRS306-LuciYFP was a gift from Dr. Bernd Bukau (Heidelberg University). Tdp43 plasmid was a gift from Dr. Jiou Wang’s lab (Johns Hopkins University). Most of the expression plasmids were constructed based on the p404 backbone33. The verification of MudPIT hits was done with the strains from the yeast GFP library34. Split-GFP system’s DNA fragments were synthesized by gBlocks (Cabantous et al., 2005). GFP1-10 was in frame with mitochondria targeting sequence (MTS) and mCherry. GFP11 replaced GFP in pFA6a-GFP (S65T)-His3MX6 to serve as the universal C-terminal tagging plasmid. APEX2 was in frame with MTS-GFP. For SIM assay, mitochondrial outer membrane was labeled with mCherry-Fis1TM35; GFP1-10 was fused with the mitochondrial matrix protein Grx5 (Grx5- GFP1-10); the native aggregate protein Lsg1 was tagged with GFP11. For mammalian plasmids, MTS-mCherry-GFP1-10 replaced the DsRed in pDsRed-Monomer-Hyg-N1 vector; GST-HA-GFP11, FlucWT-HA-GFP11, FlucSM-HA-GFP11 or FlucDM-HA-GFP11 replaced the GFP in pAcGFP1-N1 vector, respectively.

Confocal microscopy

Live-cell images of yeast were acquired using either a Yokagawa (Tokyo, Japan) CSU-10 spinning disc on the side port of a Carl Zeiss (Jena, Germany) 200m inverted microscope or Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA) Ultraview VoX system equipped with Zeiss Definite Focus, or a Carl Zeiss LSM-510 Confocor 3 system. 488/561 nm excitation was used to excite GFP/RFPs, and emission was collected through the appropriate filters onto a Hamamatsu C9100-13 EMCCD on the spinning disc systems or the single photon avalanche photodiodes on the Confocor 3. All GFP images were acquired through a 500–550 nm filter. RFP images were acquired with a 580 nm long pass filter on the CSU-10, and a 420–475/502–544/582–618/663–691 multiband filter on the Ultraview. All images were acquired in a multi-track, alternating excitation configuration so as to avoid GFP bleed through. The CSU-10 and Ultraview systems utilized a 100× 1.45 NA Plan-Apochromat objective. Images were acquired using MetaMorph (version 7.0; MDS Analytical Technologies) on CSU-10 spinning disc system, Volocity 6.3 (Perkin Elmer) on Ultraview system and Carl Zeiss AIM software for the LSM 510. Mammalian cell images were acquired using Zeiss LSM780 confocal (Jena, Germany) with 40X/1.4 oil Plan-Apochromat objective.

Yeast cells were grown in synthetic complete (SC) or drop-out media containing 2% dextrose overnight at 30 °C (23 °C for ts mutants). The 4 ml (or 8 ml for recovery assays) mid-log culture with OD600 of roughly 0.5 was transferred to 42 °C to be heat-shocked for 30 min. For 3D fluorescence time-lapse imaging, cells were placed on a thin SC (2% dextrose) agarose gel pad to allow for prolonged imaging at room temperature36. 3D image stacks were acquired every minute for 60–90 min. Each z-series was acquired with 0.5-micron step size. All image processing was performed using the Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). For visualization purposes, images in the figure were scaled with bilinear interpolation.

Drug treatments and antibodies

Cycloheximide (C4859, Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Hydrogen peroxide solution (216763, Sigma) was diluted 10 times in H2O and added to a final concentration of 0.7 mM at 30 °C to induce protein aggregation. CCCP (C2759, Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO or ethanol to 20 mM as stock and 25μM was used to treat cells. MG132 (c2211, Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO and 80 μM was used to treat cells. PMSF (P7626, Sigma) was dissolved in ethanol and 1 mM was used to treat cells. DHE staining was done by incubating cells with 180 μM DHE (D11347, Invitrogen) for 10min at room temperature. Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM, T5428, Sigma) was added to a final concentration 1 μM for 30 minutes at 30 °C. Anti-HA-Peroxidase in APEX assay was from Sigma (12013819001). HA-Tag (C29F4) Rabbit mAb #3724 from Cell Signaling Technique was used in all the other immunoblots. Anti-GFP was from MBL International Corporation (#598). Guanidine hydrochloride (Sigma G3272) 3 mM was added during heat shock. Anti-Tom70 antibody, anti-Dld1 antibody and anti-Abf2 antibody were kindly provided by Steven Claypool’s lab (Johns Hopkins University).

Aggregate dissolution assay

Aggregate dissolution assays were done as described previously37. Briefly, yeast cells were heat shocked at 42 °C for 30 min and recovered for 15min at 30 °C or 23 °C (for ts mutants) with or without additional drug such as CHX or CCCP before mounted on an agarose gel-pad slide for 3D time-lapse imaging. The major technical flow is as follows: after generating masks of the aggregates, cell areas and cytoplasm were created and used to calculate the average intensity of aggregate regions (including cytosolic background), average cytosolic intensity, and total aggregates area. The average cytosolic intensity was subtracted from the average aggregate region intensity to obtain the corrected average aggregate intensity without cytosolic background. Finally, the total aggregate intensity was calculated by multiplying the corrected average aggregates intensity by the aggregate area and normalized to the initial intensity for comparison between strains or conditions. Aggregate intensities were measured starting at 30 minutes after the start of acquisition because during the early part of the movies aggregates grew in intensity as explained in detail previously37.

Measurement of cellular ATP level using FRET-based biosensor

FRET measurement of cellular ATP level was performed by using the acceptor photobleaching method as described previously35. Briefly, yeast cells expressing AT1.0338 were heat-shocked at 42 °C for 30 min and recovered with or without indicated compounds for 0 min, 30 min or 60 min. Cells were then immobilized on a glass slide and imaged using a Perkin-Elmer Ultraview spinning disc system with a CSU-X1 Yokogawa disc. A 100X 1.4 NA Plan-apochromatic objective was used, and emission was collected onto a C9100 Hamamatsu Photonics EM-CCD. CFP was excited with a 440 nm laser, and emission was collected through a 456–484 nm band pass filter. All FRET efficiency was normalized to the mean of CHX treated group.

Purification of protein aggregates

240 mL yeast culture (FlucSM-GFP or FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag) with OD around 0.5 were heat shocked in 42 °C water bath or treated with 0.7 mM H2O2 for desired period of time. After HS or H2O2, CHX and CCCP were added to prevent aggregate formation and dissolution. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 2 min and the pellet was washed once with water, re-suspended in 1mL 10 mM DTT (100 mM Tris-H2SO4, PH 9.3) for 5min at 30 °C. Then the cells were washed once with sorbitol buffer (20 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, PH 7.5, 1.2 M Sorbitol), followed by 5 min digestion with 0.7 mg/mL zymolase100T (US biological) in 1 mL zymolyase buffer. Zymolyase was removed by centrifugation (800 g) and cells were washed twice with zymolyase buffer. Cells were lysed with 800 μl ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES PH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton-X100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (roche #11836170001) and 10 U/mL RNasin plus RNase Inhibitor (N2611) by pipetting 15–20 times on ice. 2min centrifugation at 800 g was followed by 1min 6,000 g centrifugation to remove cell debris. The supernatant was carefully transferred to the top of sucrose gradient consisting of 650 μl 50%, 2 mL 20% and 1 mL 10% sucrose dissolved in the lysis buffer. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 16 min. 18-gauge needles were used to insert into 20% sucrose fraction from the side of centrifuge tube to collect about 900 μl 20% sucrose fraction. The entire 900 μl 20% fraction was directly applied to the column prefilled with about 600 μl M2 resin (A2220, sigma) prepared in cold room according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The column was then washed 20 times with 1 mL cold wash buffer (1xTBS contain 10 U/mL RNasin plus). Then the beads were carefully transferred into a new 2 mL tube, gently inverted 10–15 times and left on rack for about 5 min-10 min to separate beads from wash buffer. The supernatant was replaced with fresh wash buffer. The beads were then loaded back to column and incubated with 650 μl of 1xTBS supplemented with 2% SDS for 5 min on bench before elution. To examine Tom70 and Tom40 in the purified aggregates, we engineered HA tag to the C-termini of Tom40, Tom70, Om45, Mdm10 and Mdm34, respectively, in FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag background; Tom40 and Tom70 in FlucSM-GFP background. Similar amounts of aggregates purified from 7 different strains were used to detect Tom70 and Tom40.

MudPIT Analysis

TCA-precipitated proteins were urea-denatured, reduced, alkylated and digested with endoproteinase Lys-C (Roche) followed by modified trypsin (Promega)39, 40. Peptide mixtures were loaded onto 250 μm fused silica microcapillary columns packed with strong cation exchange resin (Luna, Phenomenex) and 5 μm C18 reverse phase (Aqua, Phenomenex), and then connected to a 100 μm fused silica microcapillary column packed with 5 μm C18 reverse phase (Aqua, Phenomenex)39. Loaded microcapillary columns were placed in-line with a Quaternary Agilent 1100 series HPLC pump and a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-LC electrospray ionization source (ThermoScientific, San Jose, CA). Fully automated 10-step MudPIT runs were carried out on the electrosprayed peptides, as described in (Florens and Washburn, 2006). Tandem mass (MS/MS) spectra were interpreted using SEQUEST41 against a database consisting of 6019 nonredundant yeast proteins (NCBI, 2013-02-26 release), 160 usual contaminants (human keratins, IgGs, and proteolytic enzymes). To estimate false discovery rates (FDR)s, the amino acid sequence of each non-redundant protein entry was randomized to generate a virtual library. This resulted in a total library of 12038 non-redundant sequences against which the spectra were matched. Peptide/spectrum matches were sorted and selected using DTASelect42 with the following criteria set: Spectra/peptide matches were only retained if they had a DeltCn of at least 0.08, and minimum XCorr of 1.8 for singly-, 2.0 for doubly-, and 3.0 for triply-charged spectra. In addition, peptides had to be fully tryptic and at least 7 amino acids long. Combining all runs, proteins had to be detected by at least 2 such peptides, or 1 peptide with 2 spectra. Peptide hits from multiple runs were compared using CONTRAST42. To estimate relative protein levels, distributed Normalized Spectral Abundance Factors (dNSAFs) were calculated for each detected protein/protein group, as described43. Table S1 and S2 were generated by filtering the hits with stringent cutoff (FDR<0.05 and were identified in 3 out of 4 repeats for 30 min HS, 2 out of 2 repeats for other samples). The average dNSAF was used to calculate percentage of aggregate proteins identified in each condition. The aggregate proteins that can be found in a previous published mitochondrial proteome44 were included to calculate the percentage of mitochondrial protein in 30min HS sample.

Mammalian cell culture, transfection and Immunoblots

Human RPE1 (ATCC CRL4000) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (GIBCO®), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin. Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. RPE1 cells were double transfected with MTS-mCherry-GFP1-10 and protein of interest that tagged with GFP11 (2.5μg of each plasmid were applied). After 24 hours of transfection, each sample was equally divided into a new plate and a MatTek (P35G-0-14-C) dish, for western blot and imaging after another 24 hours, respectively. The cell line has been tested as mycoplasma negative.

Split GFP assay and quantification

In yeast, protein of interest was tagged with GFP11 at C terminus of its genomic locus in the strain that carries MTS-mCherry-GFP1-10. Yeast cells were grown and imaged as described above. HS was performed at 42 °C in 4 ml culture for 30 min with shaking of 220 rpm. 1 ml of yeast culture was directly taken out and imaged after HS. Post HS cultures were shaking with 220 rpm at 30 °C when indicated time points were acquired (with new medium were added to the culture to keep the OD600 below 0.5 all the time). For CCCP treatment, log phase yeast was treated with 25 μM CCCP at 30 °C for 15 min. For CHX treatment, log phase yeast was treated with 100 μg/ml CHX at 30 °C for 30 min. All the images were acquired with same laser and exposure setting. RPE1 cells were double transfected with Split-GFP constructs as described above. Cells were located using mCherry channel only.

Quantification of split-GFP fluorescence was done using a custom python code, which can be found within the git repository located at https://github.com/RongLiLab/image_analysis_and_quantification/blob/master/Ruan_Zhou_2016_zstack_analysis.py. Briefly, after reading the mCherry and GFP channel z-stacks, the intensities were summed along the z-axis. The resulting 2D image in the GFP channel was then subject to the random walk segmentation in order to segment out the yeast cells from background and watershed segmentation to separate adjacent cells. The segmentation algorithms were taken from the scikit-image library. Following the segmentation, the median GFP and mCherry intensity in each cell was calculated. Cells whose median GFP is significantly superior to the five cells with lowest GFP in the image are eliminated from further analysis, since they correspond to auto-fluorescence of dying cells. For each cell, mCherry channel was thresholded at 5% of maximal value in order to detect the mitochondria, and median GFP intensity within mitochondria was calculated. This median GFP intensity and mCherry intensity were used in the following analyses.

For yeast quantification of fraction of cells that had the split-GFP signal, all images were acquired with same microscopy setting. Different time points of each sample were set with the same minimum and maximum display value. Maximal z-projection images were used to count the number of total cell and cells with distinct split-GFP that co-localize with mitochondria mCherry. At least 9 fields from 3 different experiments were quantified at each time point. Worth noting is that, when using cells recovered from frozen glycerol stocks, about 5% of yeast in FlucSM-GFP11 showed nuclear GFP signal, but not mCherry signal. Those cells were eliminated from quantification in both cell counting and GFP/mCherry intensity ratio quantification.

Quantification of the cells with intact mitochondria

Quantification was done with another custom analysis pipeline and the python code can be found within the git repository located at https://github.com/RongLiLab/image_analysis_and_quantification/blob/master/Ruan_Zhou_2016_zstack_analysis.py. Global Otsu threshold is then applied to the maximum projection of mCherry channel to identify the locations of the mitochondria and the resulting binary mask is then segmented to determine projections of individual mitochondria. Following that, each binary label corresponding to an individual mitochondrion is skeletonized by morphological thinning in order to qualify its morphological structure (circular fragments of mitochondria v.s. elongated mitochondria). Following this, for every binary label, the length of the skeleton and total area covered is computed and used as a basis to classify the region it spans as either intact mitochondria or fragmented mitochondria. Skeleton longer than 20 pixels and total area larger than 25 pixels were used as cutoff for intact mitochondria.

APEX experiment

GFP-APEX2 was cloned from a plasmid from Dr. Alice Y. Ting lab (MIT, Massachusetts) and the following protocol was derived from the original protocol for mammalian cell culture45. MTS-GFP-APEX2 was introduced into the TRP1 locus of the strains expressing HA-tagged cytosolic proteins identified in aggregates. 4 mL of the mid-log culture was heat-shocked for 30 min at 42°C. The cell wall was reduced by incubating with 10 mM DTT (pH 9.5) for 5 min and cells were washed with zymolyase buffer (pH 7.5, 0.6 M sorbitol, 150 mM NaCl). After re-suspending the cells in zymolyase buffer, zymolyase (0.2 mg/mL), saponin (0.5 mg/mL) and biotin-phenol (BP) (500 μM) were added for 10 min to remove the cell wall and permeabilize plasma membrane to allow BP to access mitochondria. The completion of cell permeablization was verified microscopically. H2O2 (1 mM) was added for 1 min to activate biotinylation of mitochondrial proteomeby APEX2. Cells were then washed three times with reducing buffer (10 mM sodium ascorbate, 5 mM Trolox and 10 mM sodium azide in zymolyase buffer) to stop biotinylation and remove free BP. In this step, the pellet fraction containing organelles, including mitochondria, was separated from cytosolic proteins by centrifugation. After re-suspending the organelles in 100 μl zymolyase buffer, 1 mL cold lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton x100 and 1x protein inhibitor (04693159001 ROCHE)) was added to lyse the cells for 5 min on ice. After centrifugation for 10 min at 15,500 g, the lysate was incubated 30 min at room temperature with streptavidin magnetic beads (Dynabeads® M-280, 11205D) prepared according to manufacturer’s instruction and washed 5×5 min with PBS supplemented with 0.1% tween-20 and 1 mg/mL BSA. The biotinylated proteins were released from beads by incubating with sample buffer (1x NuPAGE sample buffer (NP0007) supplemented with 20 mM DTT and 2 mM D-biotin) for 10 min at 95 °C.

Mitochondrial isolation and in vitro import assay

Mitochondria purification was based on a previous protocol46. Briefly, yeast cells expressing MTS-mCherry (in wt and tim23ts background) were cultured in 10 liter lactate medium (3 g/L yeast extract, 0.5 g/L glucose, 0.5 g/L CaCl2-H20, 0.5 g/L NaCl, 0.6 g/L MgCl2-6H20, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 22 ml/L 90% Lactic acid, adjust to PH 5.5 with NaOH) to OD600 of 1. Cells were collected by centrifugation and treated with Tris-DTT buffer (0.1 M Tris, 10 mM DTT, adjust PH to 9.4). After washing with SP buffer (1.2 M Sorbital, 20 mM KPi, pH7.4), cells were treated with 0.5 mg/ml zymolase100T (US biological) at 30 °C for 40 min. Spheroplasts were pelleted, washed with the SP buffer, and then resuspended in regeneration buffer (1.2 M Sorbitol, 1 x Lactate media without glucose) in order to isolate robust mitochondria. For the protease protection assay, regeneration step was skipped. Spheroplasts were then washed with the SEH buffer (0.6M Sorbital, 20 mM HEPES-KOH of pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA of pH8.0, protease cocktail (P2714, Sigma), 10 μM Benzamidine-HCl (B6506), 1 μg/ml 1,10-Phenanthroline (P9375), PMSF 1 mM was added before use) and broken with a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,500 g (low-speed) for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 12,000 g (high-speed) for 10 min at 4 °C. This step was repeated with resuspending the first low-speed pellet and breaking it with Dounce again. The homogenate was centrifuged with low-speed and high-speed as described above. The high-speed pellet was collected and the Dounce homogenization was repeated with a loose-fitting pestle. The final high-speed pellet contained the crude mitochondria was carefully transferred to a Nycodenz gradient in Beckman 14 × 89 mm Ultra-Clear Centrifuge tubes (344059). The gradient consisted of 2.1 ml 25%, 2.1 ml 20%, 2.1 ml 15%, 2.1 ml 10%, and 2.1 ml 5% Nycodenz from bottom to top. The gradient was ultracentrifuged in a Swinging bucket rotor (Beckman SW41 rotor) for 60 min at 4 °C with speed at 30,000 rpm. Mitochondria were concentrated around 16% Nycodenz and appeared as a wide red-brownish band in the fourth layer counting from the top.

Aggregates were purified based on the method described above but with two changes. First, the strains used here (both wt and hsp104 deletion background) expressed FlucSM-HA-GFP-3xFlag-3xFKBP-Myc. The motif 3xFKBP was originally included because we thought induced binding may be necessary for import of aggregate proteins in vitro, but we found that aggregates naturally bind mitochondria without any artificial method needed (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Second, we used the crude aggregate fraction from the sucrose gradient without the affinity purification in order to obtain sufficient free aggregates for the in vitro import assay. The mitochondria import assay in vitro was detailed described previously47. Briefly, purified mitochondria 10 mg/ml were pre-treated with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma P2714, Cell Signaling Technology 5872S) for 15 min and mixed with aggregates in import buffer (3% w/v Fatty acid-free BSA, 250 mM Sucrose, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH7.2, 10 μM ATP). We note that the ATP requirement in our assay was much lower than that in previous work48, 49. This could be due to possible ATP production by the mitochondria in the assay, leading to increased ATP levels that are sufficient to support Hsp104 activity, or due to a different mechanistic action of Hsp104 in our assay system. The aggregate to mitochondria volume ratio was 1:10 (3 μl 125 μg/ml aggregates from sucrose gradient to 30 μl 10 mg/ml mitochondria). Aggregates concentration was measured and adjusted by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific #23225) and confirmed by imaging of GFP labeled FlucSM puncta’s density. Same amount of mixture was taken out at indicated time points up to 1.5 hour and boiled 15 min in SDS sample buffer for immune blot analysis.

Protease protection assay

Mitochondria from the strain expressing FlucSM-HA were purified based on above protocol in “Mitochondrial isolation and in vitro import assay”, after heat shock at 42°C. The only difference was no regeneration step after inducing spheroplasts. Purified mitochondria was washed 3 time with import buffer without ATP (3% w/v Fatty acid-free BSA, 250 mM Sucrose, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH7.2) to get rid of protease inhibitor. Then the mitochondria were spin down in 4°C 13000rpm for 10 minutes. Mitochondria were resuspended and same amount was added to 4 different 1.5 ml tubes. Group 1 without any treatment as total mitochondria. Group 2 was treated with Trypsin for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) continued with protease K treatment for another 1 hour at RT to assess the protection by mitochondrial outer membrane. Group 3 was added with digitonin to permeabilize outer membrane and Group 4 was added with both digitonin and Triton-X100 to permeabilize inner membrane. Then group 3 and 4 underwent same proteases treatment as Group 2. The volume difference was equalized with SEH buffer. Immediately after the treatment, all the samples were added with PMSF and boiled 15 minutes in SDS sample buffer for immunoblot analysis.

CHX chase assay

Log phase yeast expressing FlucSM-HA in TIM23 and tim23ts backgrounds, expressing FlucSM-HA or Lsg1-HA in Δpdr5 background were heat-shocked at 42°C for 30 minutes. Recovery at 30 °C (23 °C for tim23ts groups) was performed in the presence of 100 μg/ml CHX and indicated drugs (50 μM CCCP, 1 mM PMSF, 80 μM MG132). At indicated time points, same amount of yeast cells were collected and lysed followed by 15 minutes boiling in SDS sample buffer and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Yeast growth assays

3 single colonies of both wild type cells and pim1S1015A:PIM1 cells were inoculated in YPD and YPG (YP plus glycerol) at 30 °C overnight. The cultures were then diluted to same OD of 0.075 to refresh for 3 hours at 30 °C in order to enter log phase. Then the OD adjusted wild type cells and pim1S1015A:PIM1 cells were plated on YPD and YPG plates. Cells were spotted at 10x serial dilutions from left to right and cultured in 30 °C incubator for 44 hours on YPD plate and 60 hours on YPG plate before scanning.

Structured illumination microscopy

Mitochondrial outer membrane was labeled with mCherry-Fis1TM. GFP1-10 was fused with the mitochondrial matrix protein Grx5 (Grx5-GFP1-10). The native aggregate protein Lsg1 was tagged with GFP11. After 30 min heat shock at 42 °C, the split GFP signal was imaged with mitochondria by using the Nikon structured illumination microscope (Nikon, N-SIM) with the 100x TIRF objective. 3D reconstruction was done using the Elements N-SIM software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 6.0. For the yeast cell data, unpaired Student’s t test was used to determine significant differences between samples. For the mammalian cell imaging data, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (nonparametric distribution) was used to determine significant differences between samples; for the mammalian cell immunoblot results, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test nonparametric distribution) was used to determine significant differences between samples (significance levels: (*) for p < 0.05, (**) for p < 0.01, (***) for p < 0.001).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Aggregate purification and role of mitochondrial import in aggregate dissolution.

a, Schematics of aggregate purification. Yeast strain expressing FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag or FlucSM-GFP as control were treated with heat shock (HS) at 42°C to induce aggregate formation (green dots). Cell lysates were then applied to sucrose gradient centrifugation to separate FlucSM-GFP monomers from aggregates. The fraction enriched for protein aggregates was applied to an anti-Flag column to separate FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag aggregates from other cellular debris (grey shapes). b, Representative images (n=8) of anti-flag resin and associated aggregates isolated from FlucSM-GFP (left) or FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag (right) strains. c, Total non-redundant peptides identified by MudPIT of independent repeats using FlucSM-GFP-3xFlag (Blue) and FlucSM-GFP (Red) strains. d, Representative images of examples of proteins identified by MudPIT that form aggregates after 30 min HS. Not3 is a negative control. 3 images for each. e, Tom70-GFP did not colocalize with aggregates after 30 min HS. FlucSM-RFP was used as a marker for cytosolic aggregates. Image represents 5 captured. f, Anti-HA immunoblot showing co-purification of HA-tagged Tom70 and Tom40 but not Om45 with aggregates. g, Additional negative controls for experiment in (f): anti-HA immunoblotting of two mitochondrial outer membrane proteins Mdm10 and Mdm34 that face cytosol and were not identified by proteomics to be enriched in aggregates. h, Dissolution kinetics of HS-induced FlucSM-GFP aggregates in cells treated with CHX (green) or CHX+CCCP (red). Shown are fluorescent traces of 3 biological repeats for each condition. i, Measurement of ATP level under the same experimental condition as that for (h) using a FRET-based sensor showing that CCCP did not deplete cellular ATP. The FRET efficiency of CCCP+CHX treated group and CHX treated group were normalized to the mean of CHX treated group at each indicated time point. 36 cells were measured for time 0 (right before drug addition), 43, 74 cells for CHX condition (30′ and 60′), and 39, 74 cells for CHX/CCCP (30′ and 60′). Shown are mean and SEM. j, Images, representative of ~ 300 cells imaged, from 3 biological repeats of TIM23 and tim23ts cells stained with TMRM (red) after HS to demonstrate that the membrane potential of these cells were similar. Scale bar: 2.5 μm for (e), 5 μm for the others. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 2. Additional data demonstrating import of aggregate proteins into mitochondria after HS.

a, Schematic diagram explaining the split-GFP assay to detect translocation of a cytosolic protein to mitochondria. b, Positive (Grx5) and negative (Hsp104, Not3) controls used for the split-GFP assay. Also shown is that the split-GFP signal for the stable mitochondrial matrix protein Grx5 did not diminish in cells treated at 30°C with CCCP for 15 min. This result is to be compared with that in Extended Data Figure 6a. Top panels: split GFP images; middle panels: MTS-mCherry-labeled mitochondria; bottom panels: merged images. Images represent 9, 9, 4, 7, 8, 6, 7 captured from left to right. c, Additional examples of HS-induced translocation of cytosolic aggregate proteins into mitochondria, as shown by split-GFP signal after heat shock. Tsl1 and Tma19 are aggregate proteins confirmed by both imaging and proteomics (n=9, 3 biological repeats). d–f, Representative images (d) and quantifications (e,f) showing that CCCP treatment blocked the HS-induced mitochondrial translocation of Lsg1-GFP11. Shown in (e) and (f) are mean and SEM of, from left to right, 874, 503 and 385 cells counted (e) and 351, 164 and 261 cells quantified (f); 3 biological repeats. In (f) the intensity ratio from each cell normalized to the mean of 30°C control samples before treatment. g,h, Images (g) and quantification (h) of TDP43-GFP11 split-GFP (top) and mitochondria (bottom). Shown in h: mean and SEM of 96 (30 °C) and 133 (HS) cells imaged and quantified; 3 biological repeats. i, Representative images showing the effect of inhibition of Hsp104 with GdnHCl on FlucSM import. j, Quantification of images in (i) and Fig. 2e with the corresponding controls. Shown are mean and SEM, from left to right, of 174, 195, 181, 183, 180 and 168 cells. k–n, Protease protection assay. (k) shows aggregates with FlucSM-GFP attached to purified mitochondria (red), representative of 8 images acquired. (l,n) show immunoblots of purified post-HS mitochondria treated with or without detergents and proteases as indicated. TR, trypsin; PK, protease K. m, Anti-HA immunoblot of Tom70-HA as a mitochondria outer membrane protein in the protease protection assay in various treated samples. o, Schematics of the APEX assay to detect mitochondrial import. p, Image showing localization of GFP-APEX in mitochondria, representative of 3 images acquired. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for (e,f); unpaired two-tailed t test for (h,j): **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Scale bars: 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 3. Mitochondrial proteases and peptidases are important for efficient dissolution of aggregates after HS.

a and b, Representative images (a) and quantification (b) over time showing that the mitochondrial split-GFP signal of Lsg1-GFP11 increased after 30 min HS and gradually diminished during the 90 min recovery after returning to 30 °C. Top panels: split-GFP images; middle panels: MTS-mCherry-labeled mitochondria; bottom panels: merged images. Shown in (b) are the mean and SEM of the fraction of cells from 3 experiments that have split-GFP signal at each time point. Total 2153 cells were counted. 3 biological repeats. c, Representative images (n=8) of purified aggregates labeled by GFP-tagged FlucSM, bound to purified mitochondria, labeled with MTS-mCherry. d, Quantification of the immunoblot shown in Figure 3c. e,f, Immunoblots of FlucSM-HA after aggregates purified from Δhsp104 cells were incubated with wt mitochondria for various amounts of time as indicated (e) and quantification of the immunoblot (f). g and h, Dissolution curves of aggregates (g) and their half-decay times (h) showing that the deletion of different mitochondrial proteases delayed the dissolution of cytosolic protein aggregates. Shown in (g) are the mean curves and in (h) are data points and mean half decay times extracted from fitted curves of 3 biological repeats. Original data for each repeat is available in Supplementary Information. Scale bars: 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 4. Pim1’s protease activity is important for efficient degradation of misfolded cytosolic proteins.

a and b. pim1S1015A:PIM1 grows normally in fermentable (a) and non-fermentable conditions (b). c. Representative images showing that delayed split-GFP of FlucSM disappearance in pim1S1015A:PIM1 was not affected by CHX during the recovery phase. Top panels: split GFP images; bottom panels: MTS-mCherry-labeled mitochondria. d. Quantification of mean split-GFP/mCherry ratio for pim1S1015A:PIM1. CHX was added after heat shock. Plotted are mean and SEM from 747 cells that were imaged and measured; 3 biological repeats. e and f, Representative immunoblots (e) and quantification (f) from three biological repeats showing that the mitochondrial import (inhibited by CCCP) is the major source for degrading stress-damaged endogenous Lsg1-HA, but vacuole-mediated degradation (inhibited by PMSF) also plays a role, while the proteasome pathway (inhibited by MG132) has the least effect. (f) shows data points and mean. g and h, Representative immunoblots (g) and quantification (h) of wt or tim23ts cells treated with CHX after HS showing that mitochondrial import (inhibited by tim23ts) was a major player in the degradation of stress-damaged FlucSM-HA. (h) shows data points and mean plots from 3 biological replicates. i and j, Representative immunoblots (i) and quantification (j) showing that without HS, proteasome-mediated degradation of FlucSM-HA was inhibited by MG132. (j) shows data points and mean plots from 3 biological replicates. Scale bar: 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 5. Impairment of cytosolic Hsp70 leads to enhanced import of unfolded proteins into mitochondria and mitochondrial damage.

a and b, Representative images (a) and quantification (b) of split-GFP signal for the FlucSM-GFP11 in ssa2-4, ssa1ts strain. The cells growing at 23° C were treated with CHX for 30 min. Shown are mean and SEM of 126 and 133 cells imaged and measured; 3 biological repeats. Unpaired two-tailed t test: ** p < 0.01. c, Fraction of cells with intact mitochondria were decreased after HS and the ssa2-4, ssa1ts mutant showed more severe fragmentation and delayed recovery compare to wt (also see representative mitochondrial images in Fig. 3a). Shown are mean and SEM quantified from 3 biological repeats with 1335 cells for wild type and 967 cells for the mutant. d, Representative images (from the 160 min time point of the plot in Figure 3h) of ROS indicated by DHE signal. 1621 (mutant) and 2151 (wt) cells were imaged and quantified in this experiment. Scale bars: 5 μm.

Extended Data Figure 6. Unstably-folded cytosolic proteins are imported into mitochondria in both yeast and human RPE1 cells.

a–d, Representative images (a and c) and quantification (b and d, as in Fig. 2c) of the split-GFP signal for the super-aggregator Ded1 in cells grown at 30° C without or with CCCP for 15 min or without or with treatment with CHX for 30 min at 30° C, with 205 and 182 cells imaged and quantified in (a,b), 283 and 287 cells imaged and quantified in (c,d); 3 biological repeats. Top panels: split GFP images; middle panels: MTS-mCherry-labeled mitochondria; bottom panels: merged images. (b) and (d) show mean and SEM of the measurements from the indicated number of cells. Unpaired two-tailed t test: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. e, Images of the split-GFP signal of the cells expressing super aggregators Fas1-GFP11, Ola1-GFP11 or FlucDM-GFP11 under non-stressful growth condition (30°C) showing that these proteins are imported into mitochondria even without imposed proteotoxic stress. Top panels: split GFP images; middle panels: MTS-mCherry-labeled mitochondria; bottom panels: merged images. n=7, 9 and 9 from left to right. f, Immunoblot showing expression level of different Luciferase mutants relative to wild type Luciferase in human RPE1 cells (corresponding to the quantification in Fig. 4c), representative of 5 biological repeats for the Fluc proteins. Loading control: GAPDH. g, Working model of MAGIC. Cytosolic aggregates are attached to mitochondria through interaction with import receptors such as Tom70. Individual aggregate proteins, which may be dissociated from aggregates by Hsp104, are imported through the OM import complex to the intermembrane space, where they are either degraded by intermembrane proteases and peptidases, or continued to be imported through an IM channel to be degraded by matrix proteases such as Pim1. Scale bars: 5 μm. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kausik Si (Stowers Institute) for technical advice and reagents; Franz-Ulrich Hartl (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry), Elizabeth Craig (University of Wisconsin, Madison), Patrick Silva (Indian Institute of Science), Bernd Bukau (Heidelberg University), Steven Claypool and Jiou Wang (Johns Hopkins University) for reagents. This work was supported by the grant R35 GM118172 from the National Institute of Health to RL, and a fellowship from the American Heart Association to CZ.

Footnotes

Author contributions

L.R.: split-GFP experiments, biochemical assays with purified mitochondria (assisted by E.J.), all protein degradation experiments, aggregate dissolution in protease mutants, manuscript preparation; C.Z.: aggregate purification for proteomics, APEX experiments, aggregate dissolution in tim23ts, measurement of mitochondrial ROS, manuscript preparation; E.J.: validation of proteomics candidates, Split-GFP imaging repeats and quantification, growth assays; A.K.: image quantification programs and data analysis; Y.Z., Z.W. and L.F.: MudPIT proteomics; R.L.: overall project supervision and manuscript preparation.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schapira AH. Mitochondrial diseases. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379:1825–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansson Petersen CA, et al. The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:13145–13150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806192105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsell DA, Kowal AS, Singer MA, Lindquist S. Protein disaggregation mediated by heat-shock protein Hsp104. Nature. 1994;372:475–478. doi: 10.1038/372475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle SM, Genest O, Wickner S. Protein rescue from aggregates by powerful molecular chaperone machines. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2013;14:617–629. doi: 10.1038/nrm3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou C, et al. Organelle-based aggregation and retention of damaged proteins in asymmetrically dividing cells. Cell. 2014;159:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SB, Mogk A, Bukau B. Spatially organized aggregation of misfolded proteins as cellular stress defense strategy. Journal of molecular biology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R, et al. Firefly luciferase mutants as sensors of proteome stress. Nature methods. 2011;8:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace EW, et al. Reversible, Specific, Active Aggregates of Endogenous Proteins Assemble upon Heat Stress. Cell. 2015;162:1286–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neupert W, Herrmann JM. Translocation of proteins into mitochondria. Annual review of biochemistry. 2007;76:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.163409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin J, Mahlke K, Pfanner N. Role of an energized inner membrane in mitochondrial protein import. Delta psi drives the movement of presequences. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:18051–18057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano R. Energy requirements for maltose transport in yeast. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1977;80:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens HC, Nichols JW. The proton electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane of yeast is necessary for phospholipid flip. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:17563–17567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pareek G, Krishnamoorthy V, D’Silva P. Molecular insights revealing interaction of Tim23 and channel subunits of presequence translocase. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33:4641–4659. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00876-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabantous S, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Protein tagging and detection with engineered self-assembling fragments of green fluorescent protein. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:102–107. doi: 10.1038/nbt1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehrenbacher KL, Yang HC, Gay AC, Huckaba TM, Pon LA. Live cell imaging of mitochondrial movement along actin cables in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1996–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:R46–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker J, Walter W, Yan W, Craig EA. Functional interaction of cytosolic hsp70 and a DnaJ-related protein, Ydj1p, in protein translocation in vivo. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:4378–4386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kummer E, Oguchi Y, Seyffer F, Bukau B, Mogk A. Mechanism of Hsp104/ClpB inhibition by prion curing Guanidinium hydrochloride. FEBS letters. 2013;587:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan MT, Voos W, Pfanner N. Assaying protein import into mitochondria. Methods in cell biology. 2001;65:189–215. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(01)65012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devi L, Raghavendran V, Prabhu BM, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of alpha-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:9089–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker MJ, Tatsuta T, Langer T. Quality control of mitochondrial proteostasis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rep M, et al. Promotion of mitochondrial membrane complex assembly by a proteolytically inactive yeast Lon. Science. 1996;274:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:27280–27284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins GA, Gomez TA, Deshaies RJ, Tansey WP. Combined chemical and genetic approach to inhibit proteolysis by the proteasome. Yeast (Chichester, England) 2010;27:965–974. doi: 10.1002/yea.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knott AB, Perkins G, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy-Wetzel E. Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2008;9:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nrn2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyedmers J, Mogk A, Bukau B. Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longtine MS, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta R, et al. Firefly luciferase mutants as sensors of proteome stress. Nat Methods. 2011;8:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huh WK, et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou C, et al. Organelle-based aggregation and retention of damaged proteins in asymmetrically dividing cells. Cell. 2014;159:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran PT, Paoletti A, Chang F. Imaging green fluorescent protein fusions in living fission yeast cells. Methods. 2004;33:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou C, et al. Motility and segregation of Hsp104-associated protein aggregates in budding yeast. Cell. 2011;147:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imamura H, et al. Visualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:15651–15656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Florens L, Washburn MP. Proteomic analysis by multidimensional protein identification technology. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;328:159–175. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-026-X:159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2002;1:21–26. doi: 10.1021/pr015504q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wen Z, Washburn MP, Florens L. Refinements to label free proteome quantitation: how to deal with peptides shared by multiple proteins. Analytical chemistry. 2010;82:2272–2281. doi: 10.1021/ac9023999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinders J, Zahedi RP, Pfanner N, Meisinger C, Sickmann A. Toward the complete yeast mitochondrial proteome: multidimensional separation techniques for mitochondrial proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1543–1554. doi: 10.1021/pr050477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lam SS, et al. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat Methods. 2015;12:51–54. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boldogh IR, Pon LA. Purification and subfractionation of mitochondria from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods in cell biology. 2007;80:45–64. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stojanovski D, Pfanner N, Wiedemann N. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Methods in cell biology. 2007;80:783–806. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desantis ME, et al. Operational plasticity enables hsp104 to disaggregate diverse amyloid and nonamyloid clients. Cell. 2012;151:778–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernandez-Higuero JA, et al. Allosteric communication between the nucleotide binding domains of caseinolytic peptidase B. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25547–25555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).