Abstract

The genera Anastrepha, Bactrocera, Ceratitis, Dacus and Rhagoletis in the family Tephritidae order Diptera are economically important, worldwide distributed and cause damage to a large number of commercially produced fruits and vegetables. China had regulated these five genera as quarantine pests, including the species Carpomya vesuviana. An accurate molecular method not depending on morphology able to detect all the quarantine fruit flies simultaneously is required for quarantine monitoring. This study contributes a comparative analysis of 146 mitochondrial genomes of Diptera species and found variable sites at the mt DNA cox2 gene only conserved in economically important fruit flies species. Degenerate primers (TephFdeg/TephR) were designed specific for the economically important fruit flies. A 603 bp fragment was amplified after testing each of the 40 selected representative species belonging to each economically important Tephritid genera, no diagnostic fragments were detected/amplified in any of the other Tephritidae and Diptera species examined. PCR sensitivity assays demonstrated the limit of detection of targeted DNA was 0.1 ng/μl. This work contributes an innovative approach for detecting all reported economically important fruit flies in a single-step PCR specific for reported fruit fly species of quarantine concern in China.

Introduction

The family Tephritidae, the true fruit flies, is among the largest families in Diptera. Tephritidae includes over 5000 species classified in 500 genera1,2, is distributed worldwide except Antarctica1. Most species in the true fruit flies group cause significant damage to fruit and vegetable production and many species have spread to new regions where they have become a significant threat to global horticulture1,3. Relevant pest genera are Anastrepha Schiner, Bactrocera Macquart, Ceratitis Macleay, Dacus Fabricius and Rhagoletis Loew which are considered economically important1. China had regulated these five genera as quarantine pest, and had included other species from other genera like Carpomya vesuviana Costa. Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel), B. cucurbitae (Coquillett) and Carpomya vesuviana, which are considered invasive species and are managed carefully by the Ministry of Agriculture of China. The movements of these devastating fruit flies have increased in recent years due to international trade and globalization. Rigorous quarantine measures are in place in many countries to limit the international movement of these insects across countries and/or continents. Several International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) have been created by the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) to address the problem of invasive fruit flies. These international standards involve aspects related to pest risk managements, quarantine treatment, monitoring and control.

Rapid detection of economically important fruit flies is a pivotal measure to prevent the introduction of potentially invasive species. Indeed, this is the first and most effective approach to minimize the harm caused by invasive fruit flies4. Molecular detection methods are effective procedures to identify fruit flies rapidly overcoming life-stage restrictions because are based on species specific nucleotide sequence data. Moreover, there is no need to rear the intercepted fruit fly eggs, larvae or pupae to adults, which is a time-consuming and sometimes unsuccessful process5.

Current molecular methods for fruit flies identification focus on DNA barcoding, PCR or quantitative PCR with species-specific primers and probes. DNA barcoding uses mitochondrial (mt) DNA and focuses on the cox1 gene, which allows discrimination of most fruit flies, except several species complex which are difficult to identify in to species level6,7. However, the carry-on time for sequencing can take several hours to days causing delay downstream quarantine procedures and decision making. Universal barcode primers8 for metazoan invertebrates did not consistently discriminate some Ceratitis species such as C. cristata6. To bypass the need for post sequencing, end point PCR or quantitative PCR processing, species-specific markers were developed for one or several specific species only9–15. Jiang et al. developed a standardized reaction system for simultaneous detection of 27 fruit fly species intercepted at ports in China based on a microfluidic dynamic array of mt DNA cox1 gene that uses species-specific primers and probes for quarantine concern16. However, these molecular methods are yet insufficient to detect all economically important fruit flies at the border during quarantine inspections.

Focus toward mitochondrial genes have been consistently matter of attention for fruit flies molecular identification studies2,6,7,17,18. Most of these studies had targeted the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) as a near-exclusive data source for fruit fly species identification and species delimitation since DNA barcoding was proposed2,6,7,17–20. However, for higher taxons, such as Tephritidae, there is no suitable markers that can be used for simultaneous broad detection of economically important fruit flies21,22. Exploring mitochondrial genomes provide more information about genetic variability than shorter sequences of individual genes such as cox1 and are widely used for molecular systematics at different taxonomic levels23. We hypothesize that analyzing the whole mitochondrial genomes of Tephritidae unfolded toward some Diptera will provide new markers of value for broad detection of economically important fruit flies.

In this study, mitochondrial genomes of Diptera sourced in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) were aligned aiming for variable landmarks in Diptera but conserved in economically important fruit flies to develop a ‘specific broad detection’ pair of primers for simultaneous broad detection of all the economically important fruit flies in a single-step end point PCR.

Results

DNA extraction and quality

DNA was extracted from legs of adults of both sex and the obtained DNA concentration varied from 70–120 ng/μl. The DNA quality was determined at A260/A280 and ranged between 1.7–2.0.

Sequence alignment and primer design

The complete mitochondrial genomes of 146 Diptera species were sourced from GenBank and the pool included 16 economically important Tephritidae species: Bactrocera (Bactrocera) arceae (Hardy & Adachi)24, B. (B.) carambolae Drew & Hancock, B. (B.) correcta (Bezzi), B. (B.) dorsalis25, B. (B.) latifrons (Hendel)26, B. (B.) melastomatos Drew & Hancock26, B. (B.) tryoni (Froggatt)27, B. (B.) umbrosa (Fabricius)26, B. (B.) zonata (Saunders)28, B. (Daculus) oleae (Gmelin)27,29, B. (Tetradacus) minax (Enderlein)30, B. (Z.) cucurbitae31, B. (Z.) diaphora (Hendel)32, B. (Z.) scutellata (Hendel), B. (Z.) tau (Walker)33 and Ceratitis (Ceratitis) capitata (Wiedemann)34. Software assisted and visual analysis of the Diptera mitochondrial genomes allowed the detection of polymorphic sites. The sequence alignment is provided in Appendix S1. To specifically amplify all economically important Tephritidae species, degenerate primers were designed to target a DNA fragment within the mt DNA cox2 gene. The location of the degenerate primer pair is provided in Appendix S1. The sense primer spans from loci 5331 to 5390. The antisense primer spans from loci 5981 to 6003. Location refers to accession DQ 845759, Bactrocera dorsalis. This broad detection degenerate primer pair was labeled TephFdeg (sense) and TephR (antisense). Detailed information about this primer pair is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence, localization and thermodynamic parameters of primers used.

| Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ | Location in DQ845759* | Fragment Size (bp) | Tm (°C) | GC% | 3′ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TephFdeg | GACAACATGAGCHGSHYTHGGBCT | 3142–3165 | 603 | 55.1 to 57.6 | 41.7 | −7.0 |

| TephR | GCTCCACAAATTTCTGAACATTG | 3722–3744 | 56.6 | 39.1 | −5.9 |

*DQ845759 complete mitochondrial genome of Bactrocera dorsalis.

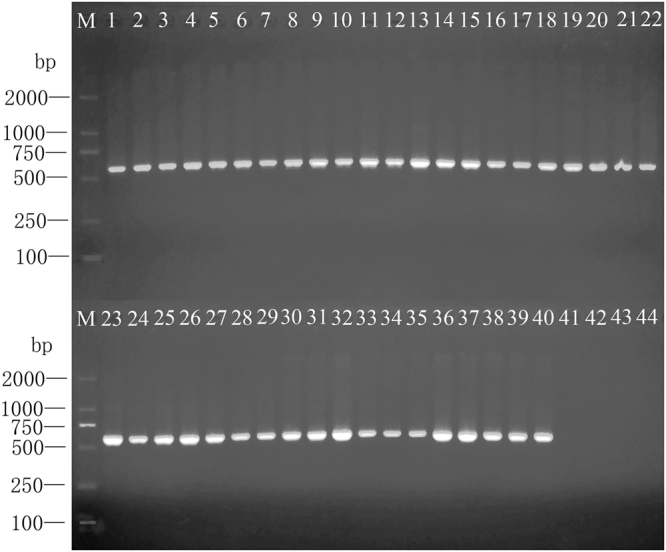

Degenerate primers specificity

Specificity test showed the amplification of a single 603 bp DNA product in each of the economically important Tephritidae species tested. No amplification was detected in of the non-economic Tephritidae and Diptera species tested (Fig. 1). These results were consistent after three replications. BLAST alignments of all obtained fragment sequences amplified by primer set TephFdeg/TephR matched with mitochondrial genes of Tephritidae species with 89%–100% identity and 0.0 E value. Detailed information of the compared species, including accession number, score, query cover, E value and identity is listed in the Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Specificity of primers TephFdeg/TephR for fruit fly broad detection. Lanes 1 to 43 correspond to species No. 1 to 43 listed in Table 2; Lane 41 is P. utilis, Lane 42 is A. striates and Land 43 is D. melanogaster, three non economically important fruit flies; Lane 44 is ddH2O non template control (NTC); and Lane M is a D2000 DNA ladder.

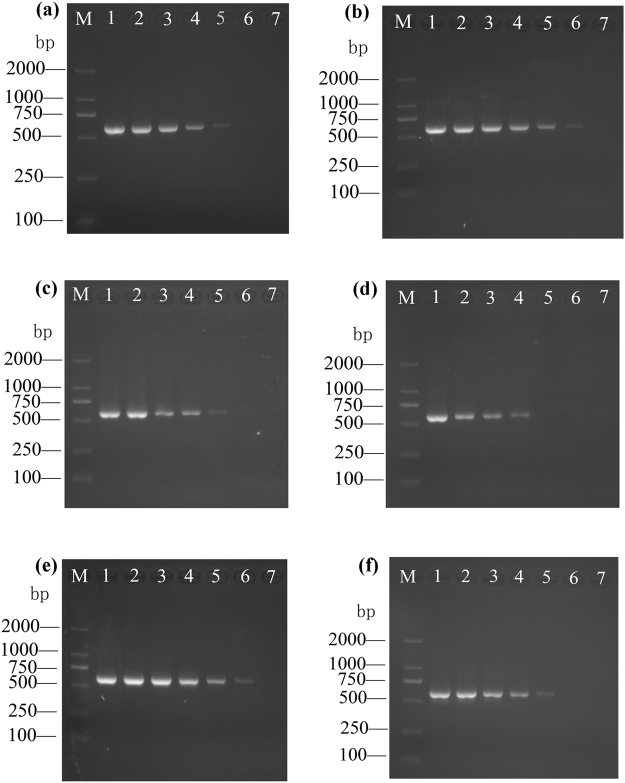

Primers sensitivity

Three sensitivity assays were performed and showed the limit of detection using Bactrocera spp. and Dacus spp. as reference species was 0.001 ng/μl, Anastrepha spp., Carpomya spp. and Rhagoletis spp. was 0.01 ng/μl, and Ceratitis spp. was 0.1 ng/μl (Fig. 2, one species of each genus as an example, the results of all tested species were shown in Supplementary Figure S1–S40). Overall, the limit of detection of all economically important Tephritidae species is 0.1 ng/μl.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity of primers TephFdeg/TephR. Template DNA are: (a) Anastrepha spp., (b) Bactrocera spp., (c) Carpomya spp., (d) Ceratitis spp., (e) Dacus spp. and (f) Rhagoletis spp.; DNA serial dilutions are as follows: Lane 1: 100 ng/μl, Lane 2: 10 ng/μl, Lane 3: 1 ng/μl, Lane 4: 0.1 ng/μl, Lane 5: 0.01 ng/μl, Lane 6: 0.001 ng/μl, Lane 7: ddH2O NTC, Lane M: is a D2000 DNA ladder.

Discussion

A pair of degenerate primers was designed and a single-step PCR method was developed to detect broad range of economically important fruit flies simultaneously. The method amplifies a single product of 603 bp. The method has application monitoring quarantine samples in China and elsewhere. It is a simple method transferable to non-taxonomists and particularly useful for detection of important fruit flies and their immature stages or partially damaged specimens missing characteristics diagnostic body parts which cannot be identified by traditional means. Previously reported molecular methods developed for identification of Tephritidae species detected several species only. This new proposed method is simple and requires no further sequencing of the amplified products, and requires only widely used PCR equipment, which facilitates the process of detection in any applied quarantine laboratory.

To demonstrate the accurate multi-target detection of fruit flies, the specificity and broad detection of the primers is the most important element. During the process of the primer design, 146 Diptera mitochondrial genomes were compared to ensure the specificity and broad detection of designed primers. However, newly released mitochondrial genomes of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann)35, B. (B.) invadens Drew, Tsuruta & White36, B. (Paradacus) depressa (Shiraki)37, B. (Z.) caudata (Fabricius)38 and Dacus (Callantra) longicornis Wiedemann39 were not included since were not available, nonetheless, TephFdeg/TephR primers amplify A. fraterculus, B. caudata and D. longicornis during the specificity test (Specimens 1, 9 and 38, Fig. 1). The competence of primers TephFdeg/TephR to amplify target fragments from B. depressa and B. invadens was verified in silico according to the sequence alignments analysis. This PCR detection method was validated with 40 economically important fruit flies. Only the expected product size was amplified and their identity was confirmed by sequencing. The NCBI accession numbers of all detection/ diagnostic fragments are listed in Table 2. Primers TephFdeg/TephR did not amplify three different species of non economic fruit flies as predicted. Primers TephFdeg/TephR showed to be reliable, since all specificity assays were successfully replicated three times.

Table 2.

Specimens tested with primers TephFdeg/TephR.

| Specimen No. | Family | Genus | Species | Stage | Source/country | Accession numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tephritidae | Anastrepha* | A. fraterculus | Adult | Intercepted | MG020783 |

| 2 | A. obliqua | Larva | Intercepted | MG020784 | ||

| 3 | A. sp1 | Adult | Intercepted | MG020785 | ||

| 4 | A. sp2 | Larva | Intercepted | MG020786 | ||

| 5 | Bactrocera* | B. albistrigata | Adult | Indonesia | MG020787 | |

| 6 | B. atrifacies | Adult | China | MG020788 | ||

| 7 | B. bezziana | Adult | China | MG020789 | ||

| 8 | B. carambolae | Adult | Surinam | MG020790 | ||

| 9 | B. caudata | Adult | Thailand | MG020791 | ||

| 10 | B. cilifera | Adult | China | MG020792 | ||

| 11 | B. correcta | Adult | China | MG020793 | ||

| 12 | B. cucurbitae | Adult | China | MG020794 | ||

| 13 | B. diversa | Adult | China | MG020795 | ||

| 14 | B. dorsalis | Adult | China | MG020796 | ||

| 15 | B. hochii | Adult | China | MG020797 | ||

| 16 | B. kandiensis | Adult | Sri Lanka | MG020798 | ||

| 17 | B. latifrons | Adult | Malaysia | MG020799 | ||

| 18 | B. minax | Adult | China | MG020800 | ||

| 19 | B. oleae | Adult | Italy | MG020801 | ||

| 20 | B. rubigina | Adult | China | MG020802 | ||

| 21 | B. scutellaris | Adult | China | MG020803 | ||

| 22 | B. scutellata | Adult | China | MG020804 | ||

| 23 | B. synnephes | Adult | China | MG020805 | ||

| 24 | B. tau | Adult | China | MG020806 | ||

| 25 | B. thailandica | Adult | Thailand | MG020807 | ||

| 26 | B. tryoni | Adult | Australia | MG020808 | ||

| 27 | B. tsuneonis | Adult | China | MG020809 | ||

| 28 | B. umbrosa | Adult | Thailand | MG020810 | ||

| 29 | B. wuzhishana | Adult | China | MG020811 | ||

| 30 | B. yoshimotoi | Adult | China | MG020812 | ||

| 31 | B. zonata | Adult | Pakistan | MG020813 | ||

| 32 | Carpomya* | C. vesuviana | Adult | China | MG020814 | |

| 33 | Ceratitis* | C. capitata | Adult | Intercepted | MG020815 | |

| 34 | C. cosyra | Larva | Intercepted | MG020816 | ||

| 35 | C. rosa | Larva | Intercepted | MG020817 | ||

| 36 | Dacus* | D. bivittatus | Larva | Intercepted | MG020818 | |

| 37 | D. ciliatus | Larva | Intercepted | MG020819 | ||

| 38 | D. longicornis | Adult | China | MG020820 | ||

| 39 | Rhagoletis* | R. pomonella | Larva | Intercepted | MG020821 | |

| 40 | R. sp. | Larva | Intercepted | MG020822 | ||

| 41 | Procecidochares | P. utilis | Adult | China | ||

| 42 | Pyrgotidae | Adapsilia | A. striatis | Adult | China | |

| 43 | Drosophilidae | Drosophila | D. melanogaster | Adult | China |

*Economically important fruit flies tested in this study.

The sensitivity of primers TephFdeg/TephR is 0.1 ng/μl of template DNA and was determined for 40 species of six economically important fruit fly genera (Fig. 2). Highly sensitive detection is very important when testing a trace amount of DNA template. A previous study showed at least 5 ng/μl DNA are obtained from any life stages of a single fruit fly sample12. DNA extraction would take time and energy, for quarantine application, quick methods for DNA extraction will also be needed. The new methodology developed here can detect the target species as long as the concentrate of DNA is above 0.1 ng/μl whatever DNA extraction method used. We believe any quick DNA extraction methods should obtain DNA from a single fruit fly with the concentrate higher than 0.1 ng/μl. Therefore, the molecular method described in this study is able to detect the presence of economically important fruit flies in any developmental stages even from a single egg.

This fruit fly detection method was developed particularly for quarantine purposes. The genera Anastrepha, Bactrocera, Ceratitis, Dacus and Rhagoletis are considered quarantine pests in China and other countries and detection at genus level is sufficient. If compared with the species-specific primers, the TephFdeg/TephR primers in this study are relatively universal and can amplify various species of quarantine fruit flies in China. Primers TephFdeg/TephR are more specific than the universal barcode primers Lco1490/Hco2198 which are widely used to amplify invertebrates8. This study did not focus on the species confirmation. For the further species confirmation, the species-specific primers and/or probes can be used to identify specific species. DNA barcoding can also be used for most Tephritidae species. However, DNA barcoding based on mt DNA cox1 gene may not allow a sharp discrimination of economically important Tephritidae species, because the existence of species complex and the lack of barcoding primers for some species6,7. The primers designed in this study overcome the described shortcomings and may provide a potential marker within mt DNA cox2 gene that facilitates the detection of economically important fruit flies at ports of entry. A more comprehensive analysis including tree-based, distance-based and character-based methods will be required to verify further uses of this new cox2 marker regarding cox1. However, a special database with obtained markers from all Tephritidae would contribute an important fruit flies identification resource particularly for quarantine purpose. Meanwhile, a standardized quarantine and identification procedure for all quarantine fruit flies can be implemented to provide a decision support tool for global import and export trade.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Thirty-two species were obtained from field collections, and the remaining 11 species were intercepted at ports of entry in China. The origin and stage information of the samples tested in this study is listed in Table 2. The larvae intercepted at ports of entry were reared to adult stage for identification. All adult samples were preserved in 100% ethanol and stored at −20 °C at the Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine until use. The adult specimens were identified according to available taxonomic keys before initiating the molecular works1,40.

Broad detection primer design

The mitochondrial genomes of Diptera were downloaded from GenBank. The sequence alignment of Diptera mitochondrial genomes was performed using DNAMAN (Demonstration Version)41. Sites with variability in Diptera, but showing conservation in economically important fruit flies only were visually identified. The broad detection primers were visually designed without software assistance during the analysis of the aligned sequences covering these sites of interest. Primer thermodynamics, GC contents and the false priming efficiency of the broad detection primer sequences were checked with OLIGO 7.042. Primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Broad detection, specificity and sensitivity of the primer test

Total genomic DNA was extracted from legs of individual adults using the TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN, China). DNA concentrations were estimated by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific, USA). The rest of the insect body and DNA were kept at −20 °C as voucher.

The specificity of the broad detection primers was tested performing PCR with the samples listed in Table 2. The criterion for primer selection was broad detection of only economically important Tephritidae samples, and no amplification of other Tephritidae and Diptera species (e.g., Procecidochares spp., Adapsilia spp. and Drosophila spp.). The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 μl, including 12.5 μl Taq PCR Master Mix (TIANGEN, China), 0.5 μl of each primer (10 μM), 1 μl of template DNA, and 10.5 μl of distilled water. PCR cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing and extension at 60 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 60 °C for 1 min. To confirm products were generated by the broad detection primers, each amplified product was sequenced using the same PCR primers. Sequencing services were by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd, and the derived sequences were submitted to GenBank for accession numbers (Table 2) and compared with known sequences in the NCBI database. The specificity test was repeated three times and three individuals of each population were used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the result.

To determine the sensitivity of the selected multi-target primers with the above-mentioned PCR condition, a dilution series of template DNA were dissolved in TE buffer from one of each species used. The DNA concentrations were 100 ng/μl, 10 ng/μl, 1 ng/μl, 0.1 ng/μl, 0.01 ng/μl, 0.001 ng/μl, respectively. Double distilled water was used as a negative control. The sensitivity test was also repeated three times for each species to make sure that the result was accurate and reliable.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 6174052), the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFF0203200) and Basic Scientific Research Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine (No. 2016JK003). Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine and Chinese Academy of Agricultural Engineering have contributed equally to this work.

Author Contributions

S.-F.Z., Z.-H.L., F.J. and Y.-P.W. designed the study; L.L. and J.W. performed the molecular work; F.J., L.L. and Y.-X.Y. analysed the data; and F.J. and L.L. wrote the manuscript with the other authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Fan Jiang and Liang Liang contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20555-2.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhihong Li, Email: lizh@cau.edu.cn.

Yuping Wu, Email: wuyuping@caiqtest.com.

Shuifang Zhu, Email: zhusf@caiq.gov.cn.

References

- 1.White, I. M. and Elson-Harris, M. M. Fruit Flies of Economic Significance: Their Identification and Bionomics. (CAB International, Wallingford, 1992).

- 2.Van Houdt JKJ, Breman FC, Virgilio M, De Meyer M. Recovering full DNA barcodes from natural history collections of Tephritid fruitflies (Tephritidae, Diptera) using mini barcodes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010;10:459–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boontop Y, Schutze MK, Clarke AR, Cameron SL, Krosch MN. Signatures of invasion: using an integrative approach to infer the spread of melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae), across Southeast Asia and the West Pacific. Biol. Invasions. 2017;19:1597–1619. doi: 10.1007/s10530-017-1382-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis, M. A. Invasion Biology. (Oxford University Press Inc., New York City, New York, 2009)

- 5.Armstrong KF, Cameron CM, Frampton ER. Fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) species identification: a rapid molecular diagnostic technique for quarantine application. B. Entomol. Res. 1997;87:111–118. doi: 10.1017/S0007485300027243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr NB, Islam MS, De Meyer M, McPheron BA. Molecular identification of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) using DNA sequences of the COI barcode region. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2012;105:339–350. doi: 10.1603/AN11100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang F, Jin Q, Liang L, Zhang AB, Li ZH. Existence of species complex largely reduced barcoding success for invasive species of Tephritidae: a case study in Bactrocera spp. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014;14:1114–1128. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu DJ, Zhang GM, Chen ZL, Zhang RJ, Yin WY. Rapid identification of Bactrocera latifrons (Dipt., Tephritidae) by real-time PCR using SYBR Green chemistry. J. Appl. Entomol. 2004;128:670–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2004.00907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu DJ, Chen ZL, Zhang RJ, Yin WY. Real-time qualitative PCR for the inspection and identification of Bactrocera philippinensis and Bactrocera occipitalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) using SYBR Green assay. Raffles B. Zool. 2005;53:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua TH, Song BK, Chong YV. Development of allele-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism-based polymerase chain reaction markers in cytochrome oxidase I for the differentiation of Bactrocera papaya and Bactrocera carambolae (Diptera: Tephritidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2010;103:1994–1999. doi: 10.1603/EC10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang F, et al. Rapid diagnosis of the economically important fruit fly, Bactrocera correcta (Diptera: Tephritidae) based on a species-specific barcoding cytochrome oxidase I marker. B. Entomol. Res. 2013;103:363–371. doi: 10.1017/S0007485312000806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang F, Li ZH, Wu JJ, Wang FX, Xiong HL. A rapid diagnostic tool for two species of Tetradacus (Diptera: Tephritidae: Bactrocera) based on species-specific PCR. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014;138:418–422. doi: 10.1111/jen.12041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arif M, et al. Array of synthetic oligonucleotides to generate unique multi-target artificial positive controls and molecular probe-based discrimination of Liposcelis species. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreason SA, et al. Single-target and multiplex discrimination of whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Bemisia tabaci and Trialeurodes vaporariorum with modified priming oligonucleotide thermodynamics. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017;110:1821–1830. doi: 10.1093/jee/tox125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang F, et al. A high-throughput detection method for invasive fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) species based on microfluidic dynamic array. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016;16:1378–1388. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong KF, Ball SL. DNA barcodes for biosecurity: invasive species identification. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2005;360:1813–1823. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey JE, et al. Developing diagnostic SNP panels for the identification of true fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) within the limits of COI-based species delimitation. BMC Evol. Biol. 2013;13:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, DeWaard JR. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. P. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2003;270:313–321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, DeWaard JR. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. P. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2003;270(Suppl.):S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staley M, et al. Universal primers for the amplification and sequence analysis of actin-1 from diverse mosquito species. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2010;26:214–218. doi: 10.2987/09-5968.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibson JF, et al. Diptera-Specific polymerase chain reaction amplification primers of use in molecular phylogenetic research. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2011;104:976–997. doi: 10.1603/AN10153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron SL. Insect mitochondrial genomics: implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014;59:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yong HS, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of Bactrocera arecae (Insecta: Tephritidae) by next-generation sequencing and molecular phylogeny of Dacini tribe. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15155. doi: 10.1038/srep15155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu DJ, Xu L, Nardi F, Li JG, Zhang RJ. The complete nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) Gene. 2007;396:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yong HS, Song SL, Lim PE, Eamsobhana P, Suana IW. Complete mitochondrial genome of three Bactrocera fruit flies of subgenus Bactrocera (Diptera: Tephritidae) and their phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nardi F, et al. Domestication of olive fly through a multi-regional host shift to cultivated olives: Comparative dating using complete mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010;57:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary JS, Naaz N, Prabhakar CS, Rao MS, Das B. The mitochondrial genome of the peach fruit fly, Bactrocera zonata (Saunders) (Diptera: Tephritidae): Complete DNA sequence, genome organization, and phylogenetic analysis with other tephritids using next generation DNA sequencing. Gene. 2015;569(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nardi F, Carapelli A, Dallai R, Frati F. The mitochondrial genome of the olive fly Bactrocera oleae: two haplotypes from distant geographical locations. Insect Mol. Biol. 2003;12(6):605–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, Nardi F, Hull-Sanders H, Wan XW, Liu YH. The complete nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae) PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu PF, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the melon fly Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Mitochondr. DNA. 2013;24(1):6–7. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2012.710224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang KJ, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Bactrocera diaphora (Diptera: Tephritidae) Mitochondr. DNA Part A. 2016;27:4314–4315. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1089479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan M, Zhang R, Xiang C, Zhou X. The complete mitochondrial genome of the pumpkin fruit fly, Bactrocera tau (Diptera: Tephritidae) Mitochondr. DNA Part A. 2016;27(4):2502–2503. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1036249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spanos L, Koutroumbas G, Kotsyfakis M, Louis C. The mitochondrial genome of the Mediterranean fruit fly. Ceratitis capitata. Insect Mol. Biol. 2000;9(2):139–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isaza JP, Alzate JF, Canal NA. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Andean morphotype of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae) Mitochondr. DNA Part B: Resour. 2017;2(1):210–211. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1307706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang LJ, et al. The status of Bactrocera invadens Drew, Tsuruta & White (Diptera: tephritidae) inferred from complete mitochondrial genome analysis. Mitochondr. DNA Part B: Resour. 2016;1(1):680–681. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2016.1219638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong SY, Kim MJ, Kim JS, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the pumpkin fruit fly, Bactrocera depressa (Diptera: Tephritidae) Mitochondr. DNA Part B: Resour. 2017;2(1):85–87. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1285212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yong HS, Song SL, Lim PE, Eamsobhana P, Suana IW. Differentiating sibling species of Zeugodacus caudatus (Insecta: Tephritidae) by complete mitochondrial genome. Genetica. 2016;144:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s10709-016-9919-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang F, et al. The first complete mitochondrial genome of Dacus longicornis (Diptera: Tephritidae) using next-generation sequencing and mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Dacini tribe. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36426. doi: 10.1038/srep36426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drew, R. A. I. and Romig, M. Tropical Fruit Flies of South-East Asia (Tephritidae: Dacinae). (CAB International, Wallingford, 2013).

- 41.Woffelman, C. DNAMAN for Windows, Version 5.2.10. (Lynon Biosoft, Institute of Molecular Plant Sciences, Leiden University, Netherlands, 2004).

- 42.Rychlik, W. OLIGO Primer Analysis Software Version 7. (Molecular Biology Insights, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO, 2009).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.