Abstract

Xin Sun and colleagues discuss the development of real world evidence in Chinese healthcare and propose strategies to improve its quality and usefulness

Worldwide, real world evidence has become a topic of broad interest in healthcare. Its definition, however, has not achieved wide consensus.1 As an umbrella term, real world evidence comes from a spectrum of studies that apply various epidemiological methods to data collected from real world settings.2 Real world data can be derived from a wide range of sources, such as routine healthcare (eg, electronic medical records), traditional epidemiological studies (eg, classical cohort studies), surveillance (eg, spontaneous adverse drug events monitoring), administrative databases (eg, death registers, medical claims), or personal devices (eg, regular blood pressure measured with mobile devices). Study designs are generally classified into three categories: pragmatic clinical trials, which may or may not be randomised; observational studies involving prospective collection of data; and observational studies using retrospective administrative databases (box 1).

Box 1. Classification and data sources of real world studies.

Pragmatic clinical trials

Varying, may include multiple sources as below

Observational studies involving prospective data collection

Disease registries

Patient surveys

Traditional cohort studies

Data collected from mobile devices

Observational studies using existing administrative data

Electronic medical records

Medical claims data

Birth or death registries

Surveillance databases

Spontaneous adverse drug events databases

Real world evidence can be used for developing medical products and informing healthcare practice and policy making. Examples of its uses include support for identification of unmet medical needs,3 design of registered clinical trials,4 post-approval drug safety assessment and pharmacovigilance,5 payment and coverage decisions,6 healthcare quality improvement,7 new indications of medical products,8 assessment of healthcare technologies,9 and clinical practice guideline development.10 In addition, the abundance and diversity of data allows exploration of clinical research questions other than healthcare interventions, such as disease burdens, prognoses, and clinical predictions.

A common misunderstanding is that traditional randomised controlled trials do not reflect the real world setting, and that all observational studies are real world.1 In fact, randomised controlled trials may include components of real world settings (eg, broad eligibility criteria and pragmatic trials)11, and real world studies may have elements that are not part of regular care (eg, intensified follow-up). Instead of a dichotomy there is a continuum in the study features of traditional randomised controlled trials and real world studies, with external validity increasing as more real world features are included in the design.

Some also argue that observational studies have advantages over randomised controlled trials in assessing the “real world” treatment effects of healthcare interventions.12 However, randomised controlled trials that have practical features continue to provide the best available evidence in the assessment of benefits and common harms, given the importance of randomisation in balancing known and unknown prognostic factors. Observational studies can provide important evidence when we want to assess harms of very uncommon events, answer harm questions that involve interactions between multiple interventions, or generate hypotheses for further testing.

Chinese experience with real world evidence

In China, the concept of real world evidence arose from awareness of the limitations of traditional clinical trials, and the need for additional evidence to inform healthcare practice and policy decisions.13 As early as 2002, the Chinese Ministry of Labour and Social Security hosted an academic forum on the use of insurance claims data for drug formulary decision and pharmacoeconomic evaluation.14

The term “real world evidence” was not explicitly used until 2010, when researchers from traditional Chinese medicine carried out a real world study to evaluate traditional Chinese medicine interventions, mainly to accommodate the complexities of such interventions.13 Since then, the Chinese research community has started to embrace the concept, and has adopted the same definition as the international research community, although some terms, such as outcomes research and comparative effectiveness research, which share overlapping concepts, have also sometimes been used.15 16 For instance, the Chinese Medical Doctor Association began to promote outcomes research in 2012, and the use of observational studies to assess the effects of healthcare interventions. In 2016, the Chinese Evidence-based Medicine Centre organised a national workshop on real world evidence to explain the concept and introduce methods of real world studies to the Chinese audience. In 2017, the centre hosted a national academic forum on the use of real world evidence in healthcare decision making.

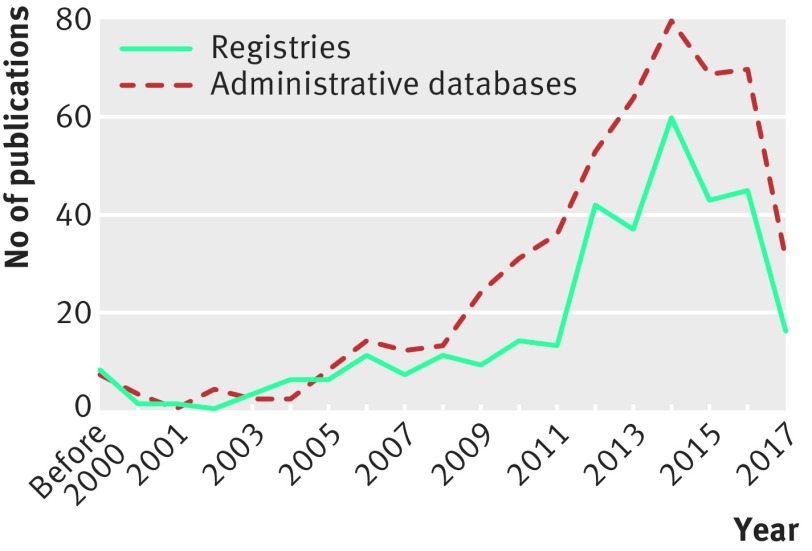

In fact, efforts to generate real world evidence started far earlier than the official introduction of the concept. The first registry in China was the Shanghai Tumour Registry, which collected data from children aged under 15 years between 1973 and 1977.17 Since then, more disease registries have been established. Our search of PubMed found that 338 articles on registries have been published since 1983. Cancer and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases are the most common topics, accounting for 75% of the publications. More registries were started after the introduction of the concept of real world evidence (fig 1, appendix 1). Some of these registries were developed at the national level. Both public and private sponsors have supported the studies, and some of the studies served simply to monitor disease.

Fig 1.

Number of published peer reviewed articles based on registries and retrospective databases in China. More details are given in appendices 1-3 on bmj.com

The first use of retrospective administrative data to produce real world evidence was in 1993, when a case-control study used medical records data of 2691 participants to examine the association between cholecystectomy and the risk of colorectal cancer.18 More recently, the interest in using electronic medical records data has increased, largely because of the growth of information technologies, and adoption of electronic medical records systems in large hospitals across the country since 2005.19

The earliest study that used electronic medical records was reported in 2006; it investigated phenotypes and clinical patterns of Crohn’s disease.20 In certain disease areas (eg, cancer), disease specific databases were also created that used a standardised process and data structure to collect data from electronic medical records across hospitals, many of which were funded by private organisations. Such databases captured data during patient hospitalisation, and patients may not be followed up if transferring to other healthcare institutions. In some regions (eg, Xiamen city), databases of electronic health records are supported and guided by local health authorities. These databases link information from community hospitals and larger hospitals, health insurance databases, and birth and death registries, making longitudinal follow-up of patients possible. In China, 523 peer reviewed articles have been cited in PubMed since 1993 using administrative databases (fig 2, appendix 2). Again, cancer and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are the most common topics of studies using retrospective databases.

In the past decade, efforts have focused on observational studies. Few pragmatic clinical trials have been conducted. Our search of both PubMed and the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database found only 16 trials explicitly labelled as pragmatic (appendix 3), all of which were published in the past decade, and nine were on traditional Chinese medicine treatments. Most trials had moderate sample sizes; only three had 700 or more participants (median 280, range 50 to 28 130). The trial with the longest follow-up investigated the feasibility and effectiveness of a comprehensive intervention package for cardiovascular disease care for three years.21 These trials were mainly funded by government grants. In addition, a few published review articles discussed the concept and methods of such designs.22 23

A number of challenges remain in the production of real world evidence. Our experience and observations have shown several problems in the use of retrospective data. The most important one is data accessibility and sharing. Concerns exist about confidentiality and the extent to which researchers may use the data (ie, data ownership). Explicit policies for data access, consent, and privacy are lacking.24

Another problem is the accuracy, completeness, and consistency of data. Established and systematic technical guidance for data collection or quality control is not available. Ethical issues are a further challenge. In many cases, the ethical approval process for retrospective database studies has proved lengthy and difficult, and ethics review boards often question the potential benefits of such studies. Lack of rigorous methods when using these retrospective databases is common—for example, failure to set eligibility criteria or include a control group. Pragmatic clinical trials and registries are less common in China, mainly because of the lack of funding, especially from public agencies, to support prospective studies. When conducting such studies, maintaining adequate follow-up in the real world setting is an important concern, mainly because patients can freely choose healthcare institutions and doctors without referral, and healthcare data are not connected across healthcare institutions.

A difficulty applicable to all types of real world evidence is the wide gap between the limited research capacity and the great demand. Researchers well trained in the methods are lacking, especially leading scientists who have an in-depth understanding of evolving frameworks and methodologies, research data, and healthcare settings.

Awareness and use of real world evidence among doctors, regulators, health insurers, and other health policy makers have increased in the past few years. The main uses are for post-approval monitoring and assessment of medical products, and payment and coverage decisions. However, opinions on the value of real world evidence differ between policy makers. Misunderstandings about real world evidence, similar to those that have occurred in the international community, are common.25 26 Tools to support the appropriate interpretation of real world evidence and to inform decisions are urgently needed.

Although the production of real world evidence is at an early stage, a few important governmental initiatives have begun in China. One such programme is the China Hospital Pharmacovigilance System, which was started in 2015 by the National Centre for Adverse Drug Reactions Monitoring at the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration. This nationwide programme was designed to identify safety signals and determine the association between drug exposure and adverse events, particularly those that occur during hospital admission. This system complements the current passive drug safety monitoring system. The system includes electronic medical records data from 300 hospitals and healthcare claims data and will be used to generate real world drug safety evidence through the use of established drug risk analytics tools, which will enable policy makers to make more informed decisions.

The China Health Policy Evaluation and Technology Assessment Network is another important government initiative through which routine or rapid assessment of healthcare technologies is commissioned by the Chinese health authorities. To assess innovative or costly healthcare technologies, retrospective data and public surveillance data are used to generate evidence on disease burdens, clinical benefits, and harms. Retrospective data are often preferred to inform rapid policy decisions when clinical evidence is lacking or locally relevant evidence is unavailable.

In the future, we expect that the need for real world evidence will continue to increase. One particular development is the use of real world evidence from the Chinese population to develop evidence based guidelines. This work is ongoing in cardiovascular diseases:27 the China Patient-centred Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events Prospective Study is being conducted to inform the prospective Chinese guideline on percutaneous coronary interventions.27

Improving real world evidence in China

We propose the following strategies to improve the quality and usefulness of real world evidence in China. Firstly, government bodies such as the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China and the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration should reinforce regulations to deal with concerns about data sources, such as confidentiality, privacy protection, data sharing, and ethical approval. The establishment of an explicit policy framework and regulatory documents will greatly improve the development of China’s real world evidence initiatives.

Secondly, a research community to foster collaboration across institutions and stakeholders must be developed urgently. This is needed to cultivate an environment of mutual understanding and cooperation to develop shared goals and agendas. We call for public and private collaborations such as the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership in the US. Recently, a national real world evidence consortium (China REal world evidence ALliance, ChinaREAL) has been established, which brings together researchers, doctors, journal editors, and policy makers across the country. The main aims include support for the production of high quality real world evidence and translation of evidence into practice and policy decisions in the Chinese setting. One of the efforts is to develop consistent and coherent technical guidance to improve data quality, and standardise diagnosis, procedures, and drug coding systems.

Thirdly, an important step is for academic institutions to develop rigorous academic postgraduate degree and fellowship programmes to foster the next generation of researchers and leaders. Educational opportunities should also be accessible to other stakeholders, including doctors, policy makers, and industry, to improve understanding and use of real world evidence.

Lastly, we call for public and private research foundations to support research that can improve data infrastructure and develop new technologies and methods. We believe such investments will greatly improve the production and use of real world evidence in China. Although the movement started later in China than in developed countries, we are confident that, with endeavours from all sides, real world evidence will further boost evidence based healthcare practice and policy decisions.

Key messages.

Real world evidence has gained wide attention in China in the past few years

Disease registries and retrospective databases are the two main types of real world studies in the China; limited resources are available for pragmatic clinical trials

Use of real world evidence for healthcare practice and policy decisions is limited at present, although there are a few important governmental initiatives

To advance the real world evidence movement, China must develop an explicit policy framework; reinforce consistent and coherent technical standards; strengthen research capacity, and foster collaborative efforts across institutions and stakeholders

Acknowledgments

We thank Hong Li and Jason Busse for their insightful review and comments. We also thank Dongtao Lin for copyediting this manuscript.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

Contributors and sources: XS’s research interests include clinical research methodology and its application to disease management, clinical evaluation of drugs, and surgical technologies. JT focuses on real world studies. LT has expertise in randomised controlled trials. JJG is an expert in pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics. XL is responsible for the development of the China Hospital Pharmacovigilance System. This article was commissioned by The BMJ, and arose from our work experience, observations, and discussions about real world studies in China. XS is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that the study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81590955; 71573183; 71704122), Thousand Youth Talents Plan of China (grant number D1024002), and The National Science Foundation for Post-doctoral Scientists of China (grant number 2016M602699). JJG is supported by the US Center of Medicaid and Medicare Services, PCORI, and unrestricted educational research grants sponsored by Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Ortho-McNeil, Roche, and Eli Lilly. None is related to this article.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Makady A, de Boer A, Hillege H, Klungel O, Goettsch W, on behalf of GetReal Work Package 1 ). What is real-world data? a review of definitions based on literature and stakeholder interviews. Value Health 2017;20:858-65. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real-world evidence— what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med 2016;375:2293-7. 10.1056/NEJMsb1609216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charter R, Yeung A, Smith M, et al. The assessment of value for medical devices: using real world evidence (RWE) to quantify unmet needs in diabetes management. Value Health 2016;19:A703 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.2046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li G, Sajobi TT, Menon BK, et al. 2016 Symposium on Registry-Based Randomized Controlled Trials in Calgary Registry-based randomized controlled trials—what are the advantages, challenges, and areas for future research? J Clin Epidemiol 2016;80:16-24. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s Sentinel Initiative. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/Safety/FDAsSentinelInitiative/default.htm.

- 6. Garrison LP, Jr, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, Marshall D, Mullins CD. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health 2007;10:326-35. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ko CY, Hall BL, Hart AJ, Cohen ME, Hoyt DB. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: achieving better and safer surgery. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2015;41:199-204. 10.1016/S1553-7250(15)41026-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration. Use of real-world evidence to support regulatory decision-making for medical devices: guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff. 31 August, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-meddev-gen/documents/document/ucm513027.pdf.

- 9. Makady A, Ham RT, de Boer A, Hillege H, Klungel O, Goettsch W, GetReal Workpackage 1 Policies for use of real-world data in health technology assessment (HTA): a comparative study of six HTA agencies. Value Health 2017;20:520-32. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oyinlola JO, Campbell J, Kousoulis AA. Is real world evidence influencing practice? A systematic review of CPRD research in NICE guidances. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:299. 10.1186/s12913-016-1562-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147. 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ross JS. Randomized clinical trials and observational studies are more often alike than unlike. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1557. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tian F, Xie YM. [Real-world study: a potential new approach to effectiveness evaluation of traditional Chinese medicine interventions]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao 2010;8:301-6. 10.3736/jcim20100401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo JJLG, Li H. China hosts the first pharmacoeconomic international forum for medical insurance executive members in Shanghai [Newsletter]. International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) . Connections 2003;9:14. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xie Q, Jiang L, Liu B, et al. [Discussion on the key issues and strategies about carrying out the comparative effectiveness research of Chinese Medicine in real-world] [Chinese]. World Chin Med 2014;9:28-31.25558275 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Y. [Engaging actively with effectiveness evaluation of drugs in real-world study] [Chinese]. Chin J Drug Eval 2012;29:1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tu J, Li FP. Incidence of childhood tumors in Shanghai, 1973-77. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983;70:589-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeng ZS, Zhang ZF. Cholecystectomy and colorectal cancer in China. Surg Oncol 1993;2:311-9. 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shu T, Liu H, Goss FR, et al. EHR adoption across China’s tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Med Inform 2014;83:113-21. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu X, Lu XH. [The phenotype and clinical patterns of Crohn’s disease in the Chinese] [Chinese]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2006;45:661-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei X, Walley JD, Zhang Z, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention for patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease in rural China: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183169. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tang L, Kang D, Yu J, et al. [Pragmatic randomized controlled trial: An important design for real-world study] [Chinese]. Chin J Evid Based Med 2017;17:999-1004. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang YH, Liang WX, Zhu L. [Comparison of pragmatic clinical trials and explanatory clinical trials] [Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2009;29:161-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aljunid SM, Srithamrongsawat S, Chen W, et al. Health-care data collecting, sharing, and using in Thailand, China mainland, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Malaysia. Value Health 2012;15(Suppl):S132-8. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun Xin TJ, Li T, Chuan Y, et al. [Revisiting real-world study] [Chinese]. Chin J Evid Based Med 2017;17:126-30. 10.7507/1672-2531.201701088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang Z, Luo Y, Liu J. Method and practice of real world study. J Evid Based Med 2014;14:364-8. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kwong JSW, Sun X. Development of local clinical practice guidelines in the real world: an evolving scene in China. Heart Asia 2017;9:e010903 10.1136/heartasia-2017-010903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3: