Abstract

Wei Fu and colleagues discuss the use of research to help develop evidence based health policies in China

Health is a basic right of human beings and is the basis of national development and prosperity. To better meet the health needs of its population, the Communist Party and the central government in China started major healthcare reforms.1 The new round of health systems reform, which began in 2009 with the goal of assuring affordable universal basic healthcare for all Chinese citizens, has had considerable success, especially in coverage of universal health insurance.2 However, important and long term health related issues still need to be tackled, given new challenges from industrialisation, urbanisation, and the ageing population, as well as environmental and lifestyle changes.3 4 5 6 As a result, the Healthy China 2030 Plan was launched. However, because of these challenges and slowing economic growth, the health policy making needed to be based on scientific evidence.

Healthy China 2030 Plan

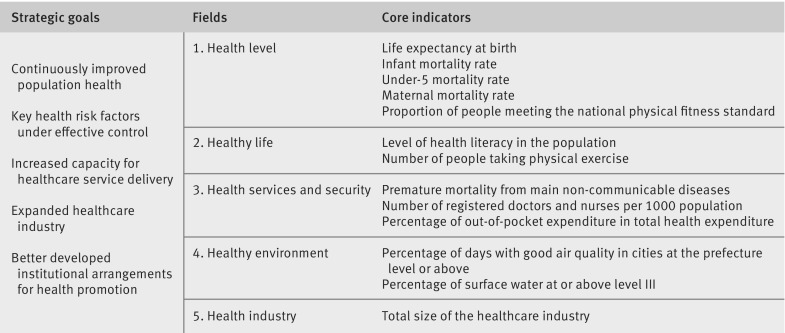

Healthy China 2030 Plan, which was launched in October 2016 by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the State Council, is an important national medium and long term strategic plan for the health sector. The plan aims to promote healthy lifestyles, improve health services and the health industry, and build a sustainable health system to provide essential health services to every citizen by 2020 and reach the main health indicators of high income countries by 2030.7 The plan is based on four core principles—health as a priority, reform and innovation, scientific development, and equity and justice—and five strategic goals. To monitor and evaluate these goals, 13 indicators in five fields were set to be achieved by 2020 and 2030. The framework of the plan is shown in fig 1.

Fig 1.

Framework of Healthy China 2030

Healthy China 2030 is a complete national action plan covering the important areas of healthcare, including infant and maternal health, mental health, healthy ageing, healthy lifestyle promotion and education, control and management of non-communicable diseases, disease prevention, capacity building of healthcare services, building healthy environments (water and air quality improvement), and health services and security. The plan sets targets for percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure.7 The health expenditure financing mechanism safeguards people’s access to healthcare services, and the percentage of out-of-pocket payment is an important indicator of people’s health financial burden and health financing equity in the population.

National health accounts and out-of-pocket payment

Policy makers and stakeholders are becoming more aware of the importance of monitoring resources for health. Health accounts provide a systematic record of expenditure on healthcare goods and services.8 National health accounts were developed in the early 1980s in China with the help of the World Bank and since then their quality has improved substantially.

In China, total health expenditure is defined as the total funds spent on healthcare and services, which is in keeping with international standards, and has three financing components—government health expenditure, social health expenditure (eg, non-government social insurance contributions, commercial health insurance payments, and donations from non-governmental organisations), and out-of-pocket payments.9

Out-of-pocket payments are defined as the direct medical costs borne by households8 and depend on the willingness and ability of individuals or households to pay. If a health financing system relies too much on out-of-pocket payments, people may face catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment or have to forgo care because of unaffordable medical costs. According to the World Health Organization, an increase of 1% in the share of out-of-pocket payment in the total health expenditure will increase catastrophic health expenditure of households by 2.2%. When out-of-pocket payments account for less than 30% of total health expenditure people can be protected from health financing risk and the disparity in health service use can be reduced between people with different income levels.9

Medical financial burden

Changes in health financing policies have led to a rapid rise in medical costs for people in China since the 1980s, mainly for two reasons.10 The first is a substantial decrease in health insurance coverage, especially for rural residents when communes and their cooperative medical schemes collapsed after privatisation of the agricultural sector economy. The second is the implementation of a policy that allowed health facilities to recover costs by charging for services. This encouraged health facilities to generate revenue through, for example, overtreatment and overprescription. Fees for services became the main way of financing healthcare,11 12 with the percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure increasing from 21.2% in 1980 to 60% in 2001.13 As a result, financial difficulties from high medical costs increased during this period. In 2008, out-of-pocket payment as a share of household expenditure was 12.1%, and 13.0% of households experienced catastrophic health expenditure.14 According to WHO, China ranked 188th among 191 member states in fairness of financial contribution.15 High dependence on out-of-pocket payment had exacerbated inequity in China.

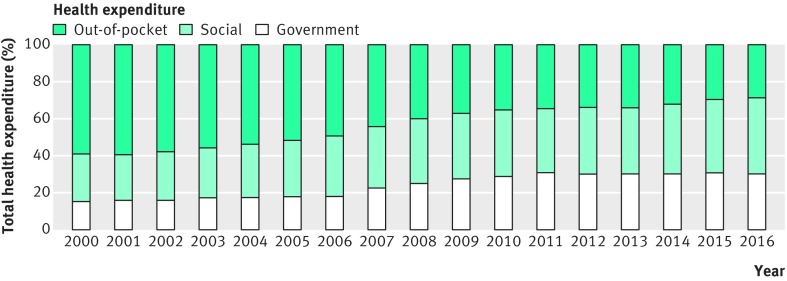

To reduce the medical financial burden on households and ensure access to healthcare, the Chinese government implemented a series of healthcare reforms with stated healthcare goals.1 For example, the 12th Five-year Health Plan of China (2011–15) set a target to reduce the percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure to below 30% by 2015 as one of the development indicators.16 During the plan, health insurance coverage was expanded, government health investment was increased, and the medical financial burden on people decreased greatly. The percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure in China declined from 60% in 2001 to 28.8% in 201613 (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Distribution of health expenditure in China, 2000-16

However, the financial burden for medical care is still excessive, and impoverishment from medical expenses has not been eliminated. The Chinese government has had success in alleviating poverty—for example, the number of rural people living in absolute poverty in China dropped substantially from 462 million in 2000 to 56 million in 2015.17 However, among underprivileged households, 44.1% were impoverished because of illness in 2015.18 Eliminating poverty caused by illness is a priority of the government in its goal to achieve universal health coverage and a prosperous society. Hence, the Healthy China 2030 Plan has set targets for the percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure to monitor the level of health financial risk protection and evaluate whether further measures need to be taken.

Projections for percentage of out-of-pocket payment

Setting a realistic target for out-of-pocket payments requires accurate prediction of health expenditure and financing trends. This is challenging, especially when socioeconomic transitions, urbanisation, population ageing, and the epidemiological transition from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases all affect future health expenditure. Projections also need to take into consideration trends in health expenditure worldwide and future public finance and health insurance schemes in China.

Health expenditure projection models fall into three broad classes with varying levels of aggregation of the analysis unit and the level of health expenditure—macro level models, component based projection models, and micro simulation models.19 Component based models stratify sections of health expenditure into groups, or individuals into groups, or a combination of the two. They are usually used for longer term forecasting and allow different assumptions.

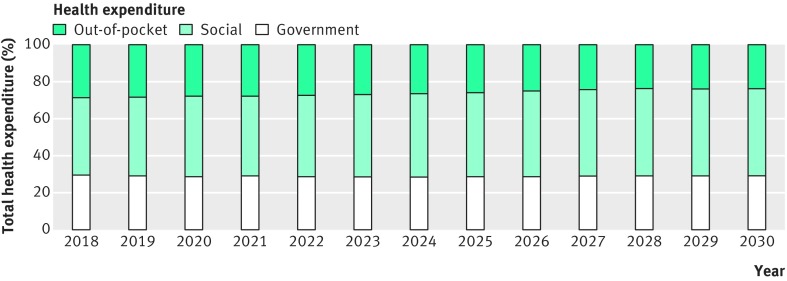

We used a component based projection model to answer policy questions about how urbanisation, population ageing, epidemiological change, and policy interventions (eg, hierarchical medical system) would affect health expenditure in the future. The explanatory factors included the projected population, age structure, disease prevalence, health service use, distribution of health service use by providers, and healthcare cost inflation. To project health expenditure by financing schemes, the increase in health expenditure in China and worldwide, and probable future health financing policies were considered. We made projections for government health expenditure and social health expenditure. The percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure was calculated by subtracting government health expenditure and social health expenditure from total health expenditure. The result is shown in fig 3.20

Fig 3.

Projected contributions of different financing schemes to total health expenditure in China, 2018-30

The results were reviewed by experts and officials from the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) and Ministry of Finance, submitted to the NHFPC and included in the Healthy China 2030 Plan. The target is to reduce the percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure to 28% by 2020, and to 25% by 2030.7 Once the current initiatives (eg, the percentage of out-of-pocket payment in total health expenditure) are underway, data on the health financial burden, health financing equity among the population, and health outcomes can be used to evaluate, adjust, and improve policies on government health input and health security.

Conclusion

Healthy China 2030, the most important national health action plan in China, initiated the move to evidence based health policy making in China. Growing awareness of the need for evidence informed health policies means health research will play an increasingly important role in developing public health policy in China.

Key messages.

Public policy making should be based on evidence

Projections of out-of-pocket spending were used to set targets in the Healthy China Plan

Health research is essential to enable increased evidence based policy making in China

Contributors and sources: All the authors have studied and reported widely on health issues and healthcare reform in China, and have a long research interest in health financing security. This article originated from discussion at a meeting on the Healthy China 2030 Plan and health research. All authors approved the final version. WF, YZ, and PC are the guarantors.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ramesh M, Wu X, He AJ. Health governance and healthcare reforms in China. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:663-72. 10.1093/heapol/czs109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yip WC-M, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 2012;379:833-42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gong P, Liang S, Carlton EJ, et al. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet 2012;379:843-52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61878-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeng Y. Toward deeper research and better policy for healthy aging – using the unique data of Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. China Economic J 2012;5:131-49. 10.1080/17538963.2013.764677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Langenbrunner J,, Marquez P,, Wang S. Toward a healthy and harmonious life in China: stemming the rising tide of non-communicable diseases. World Bank, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhai F, Wang H, Du S, et al. Prospective study on nutrition transition in China. Nutr Rev 2009;67(Suppl 1):S56-61. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.[Healthy China 2030. Outline] [Chinese]. Xinhua News Agency 25 Oct 2016. http://news.xinhuanet.com/health/2016-10/25/c_1119786029.htm

- 8. OECD A system of health accounts. OECD, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003;362:111-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hsiao WC. The political economy of Chinese health reform. Health Econ Policy Law 2007;2:241-9. 10.1017/S1744133107004197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eggleston K, Ling L, Qingyue M, Lindelow M, Wagstaff A. Health service delivery in China: a literature review. Health Econ 2008;17:149-65. 10.1002/hec.1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu S, Tang S, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Escobar M-L, de Ferranti D. Reform of how health care is paid for in China: challenges and opportunities. Lancet 2008;372:1846-53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61368-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. China National Health Development Research Center China National Health Accounts Report. CNHDRC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li Y, Wu Q, Xu L, et al. Factors affecting catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from medical expenses in China: policy implications of universal health insurance. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:664-71. 10.2471/BLT.12.102178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization The world health report 2000 — health systems: improving performance. WHO, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The twelfth five-year plan for health sector development. KPMG, 2011 https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/files/CHN%202011%20National%20Health%20Plan%202011-2015.pdf

- 17. China statistical yearbook 2016. China Statistical Press, National Bureau of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.State Council Information Office. [The State Council holds a press conference on the implementation of health poverty alleviation projects] [Chinese]. SCIO, 2016. http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/xwbfbh/wqfbh/33978/34697/index.htm

- 19. Astolfi R, Lorenzoni L, Oderkirk J. A comparative analysis of health forecasting methods. OECD Health Working Papers, No. 59 OECD Publishing, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.China National Health Development Research Center. Health expenditure forecast and its financing structure by 2030. 2016.