Significance

Subnational immigrant policies (i.e., those instituted at the state level in the United States) are not only key to successful integration, they send a message about who belongs. Our evidence suggests that welcoming state-level immigrant policies lead to greater belonging among foreign-born Latinos, US-born Latinos, and even US-born whites. Only self-identified politically conservative whites showed depressed feelings of belonging when state policies support immigrants. Patterns remained constant across states that vary in their historic reception of immigrants (Arizona and New Mexico). These findings suggest that debates about the polarizing effects of immigration policies by racial group are misplaced. With a majority of whites nationally identifying as either liberal or moderate, welcoming immigration policies have direct and spillover effects that can further national unity.

Keywords: immigration, belonging, integration, ideology, policy

Abstract

In the past 15 years, the adoption of subnational immigration policies in the United States, such as those established by individual states, has gone from nearly zero to over 300 per year. These include welcoming policies aimed at attracting and incorporating immigrants, as well as unwelcoming policies directed at denying immigrants access to public resources and services. Using data from a 2016 random digit-dialing telephone survey with an embedded experiment, we examine whether institutional support for policies that are either welcoming or hostile toward immigrants differentially shape Latinos’ and whites’ feelings of belonging in their state (Arizona/New Mexico, adjacent states with contrasting immigration policies). We randomly assigned individuals from the representative sample (n = 1,903) of Latinos (US and foreign born) and whites (all US born) to consider policies that were either welcoming of or hostile toward immigrants. Across both states of residence, Latinos, especially those foreign born, regardless of citizenship, expressed more positive affect and greater belonging when primed with a welcoming (vs. hostile) policy. Demonstrating the importance of local norms, these patterns held among US-born whites, except among self-identified politically conservative whites, who showed more negative affect and lower levels of belonging in response to welcoming policies. Thus, welcoming immigration policies, supported by institutional authorities, can create a sense of belonging not only among newcomers that is vital to successful integration but also among a large segment of the population that is not a direct beneficiary of such policies—US-born whites.

Immigration policies have been at the forefront of national debates in recent years and in the United States were a core part of candidates’ platforms in the 2016 Presidential election. However, for over a decade, the US Congress has been unsuccessful in passing comprehensive immigration reform legislation. However, efforts to adopt and implement broad national policies on immigration have been incremental, and the policies that are implemented send inconsistent messages about the extent to which immigrants are welcomed. For example, during President Obama’s tenure, there was a rise in deportations along with executive action intended to give legal status to undocumented child arrivals (1).

In the absence of a uniform and far-reaching set of national policies regarding immigration, subnational policies at the state and regional level play key roles in shaping the climate for immigrant reception. States have increasingly adopted policies and resolutions that are both unwelcoming and welcoming toward immigrants, growing in the last 15 y from nearly zero to over 300 per year, and reaching a high of 490 in 2012 (2). These include unwelcoming policies directed at denying immigrants access to public resources and making it difficult for unauthorized migrants to set down roots as well as welcoming local policies aimed at attracting and incorporating immigrants. Emblematic of the unwelcoming turn in subnational immigration laws was Arizona’s SB1070, which required law enforcement officers to assess individuals’ immigration status during a stop or arrest when there is “reasonable suspicion.” Garnering far less attention are local efforts to provide a welcoming environment for immigrants. In 2012, for example, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced, “I am committed to making Chicago the most immigrant-friendly city in the nation,” as he unveiled a 27-point plan for his city. Many other cities, counties, and states, including Cleveland, St. Louis, Baltimore, Santa Clara County (California), Iowa, and Michigan have likewise taken concrete steps to offer a welcoming environment for immigrants along with programs that focus on immigrant integration. Moreover, immediately after the election of Donald Trump, many municipal and state leaders announced that they would step up efforts to protect the rights of immigrants in their communities.

Given that both unwelcoming and welcoming responses to immigration have proliferated at the local level, what effect do these policies have on the attitudes of immigrants and members of the nonimmigrant, established communities? Much of the discussion has focused on the factors that lead states to adopt different types of policies (3–5) rather than on their psychological consequences on residents. However, psychological consequences shape the process through which policies make newcomers either successfully incorporated members of the nation or permanent outsiders (6–8). Comparative studies of locales that have adopted different approaches can unveil differences in attitudes in response to established local policies (9, 10). While evidence of state-by-state differences are suggestive, such an approach does not allow for causal inferences as to whether the policy prompted changes in attitudes or that preexisting opinions set the climate for the adoption of the policy. An experimental approach is needed to conclude that changes in local immigrant reception can elicit changes in identity and belonging that are crucial to building unity in a nation undergoing dramatic demographic changes brought on, in part, by recent waves of immigration.

Although unwelcoming and welcoming subnational immigration policies would reasonably be expected to directly affect those most closely associated with these policies (i.e., foreign-born noncitizens), because these policies define the immediate normative climate around immigration, such policies may also systematically influence other segments of the population. We thus examined the impact of unwelcoming and welcoming subnational immigration policies not only on foreign-born Latinos but also on US-born Latino Americans and US-born white Americans. While subnational-immigration policies that are unwelcoming or welcoming would likely affect foreign-born Latinos most strongly because of the potential direct impact on them personally, such policies would also likely affect US-born Latinos who are citizens by birth because such policies signal social exclusion or inclusion of members of their ethnic-identity group generally. The social messages conveyed by local adoption of unwelcoming or welcoming immigration policies, which communicate the local climate in terms of intergroup relations, might also influence the response of US-born white Americans, even though these immigration policies do not have direct personal impact on them. As the 2016 US presidential election showed, some white Americans embrace more liberal immigration policies (e.g., path to citizenship for the undocumented, welcoming refugees), but others take a more nativist stand and support slowing or stopping immigration all together. Thus, how residents respond to the adoption of unwelcoming or welcoming immigration reception policies in their state may depend upon individual-level factors, such as political ideology or historical influences including variations across states in the traditional and existing levels of receptivity toward immigrants. To address these propositions, we recruited representative samples of residents of Arizona and New Mexico. We selected these two states because they are geographically adjacent, border on Mexico (a top country of origin for migrants to the United States), and have similar population demographics (e.g., distribution of ethnic groups), but have had and currently have dramatically different orientations to immigration. To examine the extent to which our experimental manipulation of local immigrant reception similarly or differentially affect different groups of states residents, we consider both preexisting state climate and key individual differences including ethnicity, nativity, and political ideology.

An Experiment with Representative Samples of Latinos and White Americans Across Two States

Our study (n = 1,903) draws from representative samples of approximately equal numbers of Latinos and whites from two states that vary widely in their immigrant reception (Arizona-unwelcoming and New Mexico-welcoming). Against a background of extant differences in immigrant reception, we examine whether new proposals by legislators can change individuals’ feelings and sense of belonging. Participants were randomly assigned to consider a set of state immigration policies proposed by lawmakers that are framed as either welcoming of immigrants into the state (social services for noncitizens, bilingual government documents, state-issued identification cards) or unwelcoming (restrict access to social services for noncitizens, English-only laws, employer verification of immigration status). The policies are described as designed to either help immigrants become integrated into or deter them from settling in the state.

Our approach allows us to test the extent to which the adoption of new immigrant reception policies can play an independent and causal role in eliciting systematic changes in attitudes while at the same time considering whether existing differences in political climate across states will moderate the hypothesized relationship. Arizona and New Mexico are ideal locations in which to test our hypothesis about how historical norms may moderate the intended effects of new immigration reception policies. Although the two neighboring states have similar demographics, Arizona has been at the forefront of adopting statewide policies that are particularly hostile to immigrants, while New Mexico has adopted policies that routinely bring the rights of immigrants in alignment with those of citizens (e.g., in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants and issuing state identification cards regardless of immigration status) (11). Conducting the study in these two states, we can examine whether individuals will be more receptive toward messages that are consistent with existing state norms (stronger effect of welcoming policies in New Mexico vs. Arizona) and more resistant toward messages that are inconsistent with state immigration climate (12, 13); or whether instead that local institutional norms as expressed in proposed policies can independently affect individuals’ sense of belonging (less so in response to unwelcoming policies and more so in response to welcoming policies).

The large sample size of our survey and embedded experiment allow us to also examine differences across key subgroups in response to the proposed immigrant reception policies. Specifically, we examine whether the effect of new immigration reception policy proposals would differentially affect the attitudes of three key groups: (i) foreign-born Latinos who represent the newcomers; (ii) US-born Latinos who, despite having been born in the United States, are by association disproportionately affected by policies that affect immigrants (14); and (iii) US-born whites who represent the host community. Political orientation also plays a key role in shaping views about immigration. In general, politically conservative individuals are more likely to support restrictive immigration policies and are less likely to endorse welcoming policies than those who are more liberal (15–18). However, policies proposed by political leaders can affect change in public opinions through discourse and policy proposals (19). Our study tests the extent to which the effect of the proposed policies are different for political conservatives, liberals, and moderates. In sum, the experimental study design with large and representative samples of Latinos and whites drawn from two US states that diverge in their general immigrant reception climate allows us to examine the extent to which political elites can reset norms and thus affect residents’ sense of belonging through policy proposals and whether these effects differ across ethno-nativity groups (foreign-born Latinos, US-born Latinos, and US-born whites) and by political ideology (conservatives, liberals, and moderates).

Overview of Study Goals and Hypotheses

In a two-state survey with representative and approximately equal samples of Latinos and whites, we embed an experiment in which we manipulate the content of newly proposed legislation to reflect either an intent to exclude or to welcome immigrants. This approach, unlike past work that compared the association between attitudes and state climate, allows us to infer whether the adoption of immigration reception policies would lead impacted individuals to feel more or less at home in their state of residence. With the unique features of this sample, we were able to examine the effects of key demographic variables including ethno-nativity and political ideology. Specifically, we tested whether welcoming proposals led to greater belonging among members of three key groups: foreign-born Latinos who represent the immigrant community; US-born Latinos who share an ethnoracial background with their foreign-born counterparts; and US-born whites who represent the dominant US ethnoracial group. (Our goal was to present participants with a proposed set of policies to potentially change perceptions of the local norms for immigrant reception. A control condition where participants are presented with no or neutral information, while useful in comparing across experiences, is not feasible in our paradigm, which requires the proposal of and reactions to substantive policies.) Recent research suggests that whites are particularly sensitive to the group’s changing status as the majority ethnic group in the United States, and when reminded of this reality they become less tolerant of newcomers (20–22). Thus, we expected that while a welcoming reception would lead to greater feelings of belonging and generally more positive reception among Latinos, especially the foreign-born, it may alienate whites and lead to lower feelings of belonging and more negative affect. Moreover, while belonging to the same broad ethnoracial category entails some shared experiences and outlooks, ethnoracial groups are not monolithic in their political ideology (23–25). We thus also examined whether the hypothesized experimental effects would vary across the ideological spectrum with greater resistance toward welcoming policies among conservatives than among either liberals or moderates, especially among the native-born (both Latinos and whites) who have been politically socialized in the United States.

Last, we examined the extent to which these predictions hold across two states that have existing and historical political climates that are either unwelcoming (Arizona) or welcoming (New Mexico) of immigrants. Because Arizona and New Mexico share similar population characteristics but vary dramatically in their approach to immigrant reception, including this variable in our analysis allows us to test whether past and existing state climate toward immigrants would constrain the effectiveness of new proposals for immigrant reception. If we observe systematic differences as a function of state of residence, the theoretical meaning of this difference would be unclear given that the states differ on a number of potentially relevant, unmeasured dimensions. That outcome would suggest the limitations of new policy proposals to affect immigrant reception. By contrast, a pattern of findings comparable across the two states—the effects observed are not moderated by state of residence—would suggest the robustness and potential generalizability of our findings across state with diametrically different approaches toward immigrant reception.

Results

Data for our analysis come from a random digit-dialing telephone survey conducted in Arizona and New Mexico in February and March of 2016. This approach generated sizeable, representative samples of Latinos and whites from each state. A two-condition experiment exposed participants to proposals of state policies that sought either to incorporate or discourage immigrants (welcoming vs. hostile policies). The sample included 954 Latinos (324 foreign born; 630 US born), 906 US-born whites, and a small number of foreign-born whites. (In addition to the 906 US-born whites, our sample also included 43 foreign-born whites. Because the sample was too small for subgroup analysis, these cases were excluded from analyses.) A Spanish version of the survey was available and used by 29% of Latino participants. [The high correspondence between language used in the interview and ethnoracial-nativity (100% of US-born whites and 95% of US-born Latinos used English; 75% of foreign-born Latinos used Spanish) precluded us from testing the effect of interview language independent of the effect of ethnoracial-nativity.] We first ran analysis that distinguished among foreign-born Latinos who are and are not US citizens. Because the findings were similar for foreign-born Latinos, regardless of citizenship status, we collapsed across all foreign-born Latinos in our analyses. The findings below are based on comparison of three ethnoracial-nativity groups: foreign-born Latinos (47% citizens), US-born Latinos, and US-born whites.

Effect of Local Immigrant Reception Proposals on Positive Affect.

We first examined the effect of introducing new immigrant reception proposals (welcoming/hostile) on participants’ affect [index of reports of feeling happy, angry (recoded), and sad (recoded)] and whether this effect would be moderated by ethnoracial-nativity groups (foreign-born Latinos, US-born Latinos, and US-born whites), political ideology (liberal, moderate, conservative), and state of residence (Arizona/New Mexico). We conducted an ANOVA 2 (hostile/welcoming reception) × 3 (foreign-born Latinos/US-born Latinos/US-born whites) × 3 (liberal/moderate/conservative) × 2 (Arizona/New Mexico) on the composite of positive feelings in response to the proposed policy. Cell means and SDs are presented in Table S1.

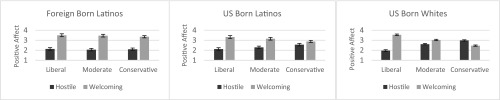

We hypothesized that the effect of condition (hostile vs. welcoming reception of immigrants in participants’ home state) would be qualified by the ethnoracial-nativity status of individuals as well as their self-identified political ideology. The findings indicate support for this hypothesis with a significant three-way (condition) by (ethnoracial-nativity) by (ideology) interaction [F(4,1,610) = 10.83, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.03]. Fig. 1 depicts the interaction between condition and ideology for each of the three ethnoracial-nativity groups. This pattern of findings was not further moderated by state of residence (i.e., patterns were similar in Arizona and New Mexico).

Fig. 1.

Effect of experimental condition on positive affect in reaction to policy proposal by ideology and by ethnoracial-nativity. Means and SE for each cell are presented.

Foreign-born Latinos.

Among foreign-born Latinos, there was a significant main effect for condition [F(1,264) = 188.63, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.42]. Overall, foreign-born Latinos reported more positive affect in response to the welcoming proposal relative to the hostile proposal. There was no significant condition by ideology interaction (P = 0.770). Together, these results indicate that reported affect in response to policy condition was similar among liberals [mean (M) = 3.50 vs. M = 2.13], moderates (M = 3.46 vs. M = 2.06) as well as conservatives (M = 3.35 vs. M = 2.10).

US-born Latinos.

Among US-born Latinos, there was also a significant main effect of condition [F(1,546) = 116.42, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.18]. However, this effect was qualified by a significant condition by ideology interaction [F(2,546) = 11.95, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.04]. As Fig. 1 shows, although all US-born Latinos responded more positively to the welcoming condition relative to the hostile condition, the strongest effect was among liberals (M = 3.32 vs. M = 2.12), less so among moderates (M = 3.15 vs. M = 2.29), and lowest among conservatives (M = 2.88 vs. M = 2.56).

US-born whites.

As with their Latino counterparts, there was a significant main effect of condition [F(1,818) = 64.83, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.07] among US-born whites. This effect was qualified by a significant condition by ideology interaction [F(2,818) = 91.49, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.18]. Fig. 1 indicates that the pattern of the interaction among US-born whites is distinct from that observed for US-born Latinos. Relative to the hostile condition, white liberals in the welcoming condition reported more positive affect (M = 3.54 vs. M = 1.96), while white conservatives in the same condition reported less positive affect (M = 2.46 vs. M = 2.98). These opposite effects of condition for white liberals and white conservatives were complemented by white moderates, who like white liberals reported more positive affect in response to the welcoming (vs. hostile) condition but the magnitude of difference across conditions was smaller (M = 3.00 vs. M = 2.61).

In addition to the hypothesized three-way interaction between experimental condition, ethnoracial-nativity, and ideology, several other effects were also statistically significant. There was a main effect of condition such that participants reported more positive feelings in the welcoming (versus hostile) immigrant reception condition [M = 3.19 vs. M = 2.29; F(1,1,610) = 336.28, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.17]. There were two two-way interactions: (i) condition by ethnoracial-nativity [F(2,1,610) = 25.29, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.03]; and (ii) condition by ideology [F(2,1,610) = 41.38, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.05]. These two-way interactions were qualified by the three-way interaction described above. Last, there was one additional three-way interaction of condition by ethnoracial-nativity by state [F(2,1,610) = 4.34, P = 0.013, η2partial = 0.005*]. There were no other statistically significant main or higher-order effects.

Effect of Local Immigrant Reception Proposals on Belonging.

We similarly examined the effect of immigrant reception proposals on individuals’ sense of belonging [index of reports of feeling more at home in their state of residence and more likely to move from that state (recoded)] among ethnoracial-nativity groups (foreign-born Latinos, US-born Latinos, and US-born whites) and ideological categories (liberal, moderate, conservative) across states (Arizona/New Mexico). Again, we conducted a 2 (hostile/welcoming reception) × 3 (foreign-born Latinos/US-born Latinos/US-born whites) × 3 (liberal/moderate/conservative) × 2 (Arizona/New Mexico) ANOVA, this time on the sense of belonging in the state in response to the proposed policy. Cell means and SDs are presented in Table S2.

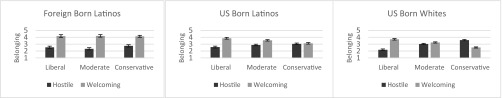

Again, we hypothesized that the effect of condition (hostile vs. welcoming reception) would be qualified by individuals’ ethnoracial-nativity and their self-identified political ideology. The findings are consistent with this hypothesis, with a significant three-way (condition) by (ethnic-nativity) by (ideology) interaction [F(4,1,586) = 8.36, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.02]. Fig. 2 depicts the interaction between condition and ideology for each of the three ethnoracial-nativity groups. Once again, this pattern of findings was not moderated by state.

Fig. 2.

Effect of experimental condition on belonging in local community by ideology and by ethnoracial-nativity. Means and SE for each cell are presented.

Foreign-born Latinos.

Among foreign-born Latinos, there was again a significant main effect for condition [F(1,258) = 152.93, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.37]. Foreign-born Latinos expressed a greater sense of belonging in response to the welcoming proposal relative to the hostile proposal. There was no significant condition by ideology interaction (P = 0.304). In other words, the sense of belonging evoked within each condition was similar among liberals (M = 4.18 vs. M = 2.54), moderates (M = 4.20 vs. M = 2.32), and conservatives (M = 4.14 vs. M = 2.75). Together, these results indicate that foreign-born Latinos, across ideological categories, reported greater belonging in their home state in response to the welcoming proposal relative to the hostile proposal.

US-born Latinos.

Among US-born Latinos, in contrast, there was a significant main effect of condition [F(1,538) = 44.91, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.08] qualified by a significant condition by ideology interaction [F(2,538) = 10.90, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.04]. Fig. 2 shows that, although all US-born Latinos responded more positively to the welcoming condition relative to the hostile condition, the strongest effect was among liberal (M = 3.85 vs. M = 2.57), less so among moderates (M = 3.56 vs. M = 2.88), and lowest among conservatives (M = 3.12 vs. M = 3.04).

US-born whites.

As with their Latino counterparts, there was both a significant main effect of condition [F(1,808) = 8.15, P = 0.004, η2partial = 0.01] among US-born whites that was qualified by a significant condition by ideology interaction [F(2,808) = 84.16, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.17]. Fig. 2 shows that, once again, the pattern of the interaction among US-born whites is distinct from that observed for US-born Latinos. Relative to the hostile condition, white liberals in the welcoming condition reported greater belonging (M = 3.70 vs. M = 2.18), while white conservatives in the same condition reported lower level of belonging (M = 2.52 vs. M = 3.59). These opposite effects among white liberals and white conservatives were complemented by white moderates for whom like white liberals expressed greater belonging in response to the welcoming relative to the hostile condition, but the magnitude of difference across conditions was smaller (M = 3.25 vs. M = 3.02).

In addition to the hypothesized three-way interaction between experimental condition, ethnoracial-nativity, and political ideology, several other effects were also statistically significant. There was a main effect of condition such that there was significantly greater sense of belonging in the welcoming (vs. hostile) immigrant reception condition [M = 3.61 vs. M = 2.75; F(1,1,586) = 173.53, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.10]. There were three two-way interactions: (i) condition by ethnoracial-nativity [F(2,1,610) = 35.63, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.04]; (ii) condition by ideology [F(2,1,586) = 40.96, P < 0.001, η2partial = 0.05]; and (iii) condition by state [F(1,1,586) = 7.43, P = 0.006, η2partial = 0.005]. These two-way interactions were qualified by the three-way interaction described above. There were no other main or higher-order effects that were statistically significant.

Discussion

The settlement of immigrants in virtually all parts of the United States has prompted policy makers to move to either make state and local contexts either more welcoming or unwelcoming. These policies emanate from political leaders’ desire for policy change, and they have a material effect on those targeted by the policies (e.g., Latinos who are not yet US citizens). However, the effect of these policies also registers psychologically, shaping the outlooks of the immigrants targeted by those laws and policies as well as the individuals who may be more tangentially affected, either positively or negatively (e.g., Latino citizens by birth/naturalization and US-born whites).

Our study drew from a representative sample of immigrants and nonimmigrants from two states that have diametrically different approaches toward immigrant reception (Arizona and New Mexico). With the unique features of this sample, we examined the influence of key demographic variables including nativity, ethnicity, political ideology, and state of residence. Importantly, our study implemented an experiment in which the participants were randomly assigned to consider a new set of policy proposals that were either unwelcoming or welcoming. One possibility for why we found similar patterns of findings in Arizona and New Mexico, despite their vastly different approaches to immigrant reception, is that the immediacy of a new proposal may raise hope or anxiety that override current state climate surrounding immigration. The fact that our key findings were not moderated by state suggests that political leaders have the potential to alter views about immigrant reception by adopting a new policy even one that departs from current practice. This analysis suggests that even discussions raised by proposed changes in policy (vs. actual policy changes) can lead to corresponding changes in attitudes.

Some of our findings affirm well-established social science research demonstrating that an unwelcoming or discriminatory climate can diminish feelings of belonging in the community (17, 26, 27). Indeed, we find that when foreign-born Latinos are exposed to the welcoming condition, they exhibit far higher levels of positive affect and a greater sense of belonging relative to their counterparts exposed to the unwelcoming condition. This effect is robust and held up regardless of state of residence or political ideology. These findings are perhaps unsurprising given that policies implemented at the state level directly target these individuals. US-born Latinos, on the other hand, are legally protected from state-level immigration policies because they are US citizens by birth. However, our results among US-born Latinos offer a similar picture, except that political ideology moderates the effect with liberals exhibiting the strongest effect, followed by moderates and then conservatives. Still, US-born Latinos in the welcoming condition, across the ideological spectrum, expressed more positive affect and felt more welcomed compared with those in the unwelcoming condition. These findings support other research showing that US-born Latinos feel the sting of unwelcoming immigration policies, for their skin color and surname can leave them vulnerable to the negative effects of stereotypes related to the nativity and legal status of Latino immigrants (14). Our findings among US-born Latinos reflect the anticipated spillover effects of proposed immigration policies specifically targeting the foreign-born noncitizens.

More surprising are our findings regarding US-born whites. Research and public discourse focus on the political rightward turn among whites, which is partly due to their views on immigration (22). The public narrative following the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump, who ran on calls for draconian restrictions on immigration, centered on his support from whites. That research and discourse led to the expectation that whites would oppose welcoming immigration policies and knowledge that political elites were considering such policies would spur negative affect and feelings of being unwelcomed. Our evidence contradicts this expectation to a large degree. Both liberal and moderate whites exhibited more positive affect and felt more welcomed when they were told that political leaders were considering making their state more welcoming to immigrants. This general pattern was moderated by political ideology, with the effect more pronounced among liberals than among moderates. The only deviation from this pattern was among self-identified conservatives. White conservatives showed less positive affect and felt less welcomed when primed to believe that policies welcoming immigrants to their state were being considered.

Our findings suggest that policies that welcome immigrants are not only likely to receive broader support than public discourse suggests, but can also have a profoundly positive effect on both immigrants and the established populations that receive them, including a large segment of US-born whites. Although a rightward turn in response to immigration among some whites exists (22), a plurality of whites identify as either moderate or liberal. [In the 2016 American National Election Study, only 35% of whites identified themselves as conservative (www.electionstudies.org/studypages/anes_timeseries_2016/anes_timeseries_2016.htm).] As we have shown, these moderate and liberal whites, in addition to foreign- and US-born Latinos, are likely to have positive responses to welcoming immigration policies in their state of residence. [Prior research has shown that more local contextual factors, like the pace of immigration-driven demographic change, partisanship, and politicized messages, can shape attitudes about immigration and immigration policy (10). While our data do not permit such analyses, it is an important direction for future research.] Thus, such policies proposed by political elites can potentially bridge across groups that vary in nativity, ethnicity, and even for the most part ideology to create greater unity in immigrant receiving communities in a time where there is uncertainty associated with an absence of clear and consistent policies toward immigrants nationally.†

These findings speak to a larger view of an American society that generally favors certain welcoming polices. A reliable majority of Americans, including Republicans, favor a pathway to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants, provided that they meet certain criteria (28). If federal, state, and local policies are intended to reflect the will of the people, federal immigration policies are woefully out of step. A more unwelcoming move in the enforcement of current immigration laws is likely to exacerbate the attitude–policy disconnect. As the findings here suggest, such polices are also likely to create a dark cloud over immigrants and a large swath of the established population in the communities where these immigrants reside.

Methods

Our experiment was embedded toward the end of a telephone survey conducted by ISA Corporation. A mixture of sampling methods was used: random digit dialing (RDD), landline untargeted; RDD, landline targeted (zip codes where 30% or more of the population is Latino); RDD, wireless; and targeted surname, landline. The mean interview length was 15.65 min. The cooperation rate (percentage of participants contacted who agreed to participate) was 25.6%. Data and study materials are available from the authors. The research was approved by the IRB at Stanford University, Tufts University, University of California, Los Angeles, and Yale University. The interviewer conducted verbal consent by reading a script approved by the IRBs and recorded participant’s response.

Experimental Manipulation.

Participants were told that lawmakers in their state were considering new policies that are either welcoming of or hostile toward immigrants. The specific policies varied depending on whether participants were assigned to the welcoming or to the unwelcoming condition (see SI Methods for verbatim stimuli). Latino and white participants from Arizona and New Mexico were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions.

Measured Variables.

We report below the variables included in our analyses of study hypotheses. The complete list of variables in the survey is available from the authors.

State.

We targeted residents of only these two states: Arizona or New Mexico. If individuals indicated they were not a resident of either state, the survey was terminated.

Ethnoracial-nativity groups.

We targeted Arizona and New Mexico residents who were either Latino or white. If individuals reported a different ethnicity or race, the survey was terminated. We also asked participants whether they were US or foreign born. With information about ethnicity and nativity, we identified the three ethnoracial-nativity groups for our analysis: foreign-born Latinos (17%), US-born Latinos (34%), and US-born whites (49%).

Political orientation.

Participants were asked whether they generally thought of themselves as conservative (39%), moderate (36%), or liberal (25%).

After exposure to the experimental stimuli, participants were asked five questions about their reactions if their state adopted the proposed set of policies. Would they feel (i) more or less at home, (ii) more or less likely to want to move out of the state in the future, (iii) angry, (iv) sad, or (v) happy?

Belonging.

The first two items (feel more at home, want to move out of state, reverse coded) were averaged together to for a single indicator of belonging [r(1,614) = 0.49, P < 0.001].

Positive affect.

The latter three items (angry and sad reverse coded, happy) were averaged together to form a single indicator of positive affect toward the proposal (α = 0.75).

Participants.

Our sample (n = 1,903) comprised 54% women and had a mean age of 57 y (SD, 18.38; range from 18 to 96). Of the foreign-born Latinos (n = 324), there are more conservatives (40%) than either moderates (31%) or liberals (29%), and 47% are US citizens. Of US-born Latinos (n = 630), there are more moderates (39%) than either conservatives (35%) or liberals (26%). Among whites (n = 906; all US born), there were more conservatives (40%) and moderates (37%) than liberals (23%).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Boch, Marlene Orozco, and Zachary Shufro for their research assistance. ISA Corporation carried out the data collection. The research was supported primarily by Stanford University’s United Parcel Service Endowment Fund. Early stages of this research were supported by the Russell Sage Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*To understand the three-way interaction, we conducted follow-up analysis within each ethnoracial-nativity group. In all three groups (foreign-born Latinos, US-born Latinos, US-born whites), there were significant main effects of condition (P levels < 0.001) such that respondents reported more positive affect in response to the welcoming proposal relative to the hostile proposal. This main effect of condition was qualified by state only among US-born Latinos [F(1,617) = 9.56, P = 0.002], such that the magnitude of the effect was stronger among Arizona residents (M = 3.22 vs. M = 2.22) than among New Mexico residents (M = 3.05 vs. M = 2.47).

†One potential barrier to the adoption of welcoming policies, despite evidence of its positive effects on a broad segment of the immigrant receiving communities, is that elected officials in Arizona may find it advantageous to cater to constituents more likely to engage in political participation (e.g., conservative whites). To explore this possibility, we examined data from the 2016 Cooperation Congressional Election Study, which has large numbers of respondents from Arizona and New Mexico. Those data indicate that white respondents of all ideological orientations in Arizona were extremely likely to report that they voted in the 2016 presidential election, but that white conservatives outnumbered white moderates and liberals. Forty-one percent of white respondents in Arizona considered themselves conservative compared with 27% who identified as liberal and 32% who identified as moderate. By contrast, whites in New Mexico were evenly distributed across the three ideological categories, and no group was more likely than another to report having voted in the 2016 election (29).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1711293115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lopez MH, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Motel S. 2011 As deportations rise to record levels, most Latinos oppose Obama’s policy (Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC). Available at www.pewhispanic.org/2011/12/28/as-deportations-rise-torecord-levels-most-latinos-oppose-obamas-policy. Accessed December 14, 2017.

- 2.National Conference of State Legislatures 2017 State laws related to immigration and immigrants. Available at www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/state-laws-related-to-immigration-and-immigrants.aspx. Accessed December 14, 2017.

- 3.Chavez JM, Provine DM. Race and the response of state legislatures to unauthorized immigrants. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2009;623:78–92. doi: 10.1177/0002716208331014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulasekaram P, Ramakrishnan SK. The New Immigration Federalism. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varsanyi MW, Lewis PG, Provine DM, Decker S. A multilayered jurisdictional patchwork: Immigration federalism in the United States. Law Policy. 2012;34:138–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Citrin J, Sears DO. American Identity and the Politics of Multiculturalism. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Saguy T. Commonality and the complexity of “we”: Social attitudes and social change. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2009;13:3–20. doi: 10.1177/1088868308326751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huo YJ, Molina LW. Is pluralism a viable model of diversity? The benefits and limits of subgroup respect. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2006;9:359–376. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ. Public attitudes toward immigration. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2014;17:225–249. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins DJ. Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104:40–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varsanyi M, Provine M. Divergent States: Comparing Immigration Enforcement Regimes in New Mexico and Arizona. Law and Society Association; Minneapolis, MN: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eagly AH, Telaak K. Width of the latitude of acceptance as a determinant of attitude change. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;23:388–397. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidwell B, Farmer A, Hardesty DM. Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. J Consum Res. 2013;40:350–367. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez TR. Replenished Ethnicity: Mexican Americans, Immigration, and Identity. Univ of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albertson B, Gadarian SK. Who’s afraid of immigration? In: Freeman GP, Hansen R, Leal DL, editors. Immigration and Public Opinion in Liberal Democracies. Routledge; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadarian SK, Albertson B. Anxiety, immigration, and the search for information. Polit Psychol. 2014;35:133–164. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schildkraut DJ. Americanism in the Twenty-First Century: Public Opinion in the Age of Immigration. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schildkraut DJ. Ambivalence in American public opinion about immigration. In: Berinsky A, editor. New Directions in Public Opinion. 2nd Ed. Routledge; New York: 2016. pp. 278–298. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaller J. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig MA, Richeson JA. More diverse yet less tolerant? How the increasingly diverse racial landscape affects white Americans’ racial attitudes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:750–761. doi: 10.1177/0146167214524993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danbold F, Huo YJ. No longer “all-American”? Whites’ defensive reactions to their numerical decline. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2015;6:210–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrajano M, Hajnal ZL. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barreto M, Pedraza F. The renewal and persistence of group identification in American politics. Elect Stud. 2009;28:595–605. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Branton R. Latino attitudes toward various areas of public policy: The importance of acculturation. Polit Res Q. 2007;60:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fields CD. Black Elephants in the Room: The Unexpected Politics of African American Republicans. Univ of California Press; Oakland, CA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portes A, Rubén G. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Univ of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conway MM, Wong J. The Politics of Asian Americans: Diversity and community. Routledge; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopan T, Agiesta J. 2017 CNN/ORC poll: Americans break with Trump on immigration policy. CNN.com. Available at www.cnn.com/2017/03/17/politics/poll-oppose-trump-deportation-immigration-policy/. Accessed March 21, 2017.

- 29.Ansolabehere S, Schaffner BF. 2017 Cooperative congressional election study, 2016: Common content. Available at https://cces.gov.harvard.edu. Accessed December 14, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.