Abstract

Purpose

To describe structural network differences in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with high versus low executive abilities, as reflected by measures of white matter connectivity using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional study. Of the 128 participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database who had both a DTI scan as well as a diagnosis of MCI, we used an executive function score to classify the top 15 scoring patients as high executive ability, and the bottom-scoring 16 patients as low executive ability. Using a regions-of-interest-based analysis, we constructed networks and calculated graph theory measures on the constructed networks. We used automated tractography in order to compare differences in major white matter tracts.

Results

The high executive ability group yielded greater network size, density and clustering coefficient. The high executive ability group reflected greater fractional anisotropy bilaterally in the inferior and superior longitudinal fasciculi.

Conclusions

The network measures of the high executive ability group demonstrated greater white matter integrity. This suggests that white matter reserve may confer greater protection of executive abilities. Loss of this reserve may lead to greater impairment in the progression to Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Keywords: Cognitive dysfunction, Diffusion tensor imaging, Neuroanatomy, White matter, Dementia

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a disorder that is severe enough to cause cognitive deficits but not to significantly disrupt basic day-to-day function [1]. The most common complaint of those with MCI is memory loss, although frequently this complaint is accompanied by executive deficits, which can have a deleterious impact on day-to-day activities [1]. These deficits may be subtle enough to escape detection at diagnosis. Gibbons et al. [2] developed an Executive Function (EF) score using neuropsychological data from the Alzheimer’s Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), and have reported that the EF score is a major predictor of conversion from MCI to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which suggests that those with impaired executive abilities are more likely to develop AD dementia. Executive function is the ability required to plan, organize, operate on working memory and switch between tasks [3, 4]. It requires integrated coordination of brain regions, thereby depending upon white matter connections. To date, studies of the white matter in AD have found widespread decreases in fractional anisotropy (FA) in the uncinate fasciculus, fornix and superior longitudinal fasciculus [5]. Individuals with MCI have been found to show differences in DTI measures when compared with normal individuals, including FA in the frontal and parietal regions [6]. In addition to tract-based analyses, in which major white matter bundles of the brain are examined for differences in volume and diffusive properties, the brain can be represented as a network. By looking at brain regions as ‘nodes’ of the networks and white matter tracts as the edges, analyses of ‘network measures’ can be used to describe how the brain is functioning as a whole. Prior studies have shown that network changes in AD include widespread disruptions [7] and changes in topological network organisation [8]. Executive abilities, which are known to require many distinct brain regions working together in order to efficiently perform complex tasks, are well suited to network analysis because of their reliance on global brain function.

The purpose of our study was to determine if structural network differences exist between individuals with MCI that have high versus low executive abilities. In order to do this, we used tractography calculations and network measures of white matter connectivity derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) values. We include a comparison of cortical thickness and volume between the two groups in regions both known to undergo changes in AD dementia [9, 10] (hippocampus, entorhinal cortex) as well as frontal regions implicated in executive abilities. We describe how alterations in the network of white matter connections in the brain relate to differences in executive abilities found in individuals with MCI. Although executive abilities and MCI have previously been linked using DTI [11], the use of network measures to describe this relationship is not well characterised in the literature.

Materials and methods

Our study was approved by institutional review boards of all participating institutions and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or authorised representatives. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. The data archive was initially accessed on 25 July 2014 and on 27 March 2017, and the data archive was re-accessed to verify that no new eligible participants had been added to the archive. The primary search criteria were: (i) diagnosis of MCI (including early or late MCI) and (ii) no DTI scan had been carried out. The DTI scan was added to the ADNI protocol for General Electric (GE) 3.0 T scanners in the ADNI-GO phase of the study, which was the second phase of the study and introduced imaging as a marker to determine who may progress to AD dementia of those diagnosed with MCI. The ADNI database search resulted in 128 eligible participants.

The EF score, a composite score developed by Gibbons et al. [2], is a normalised score calculated using the scores of the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution, Digit Span Backwards, Trails A and B, Category Fluency, and Clock Drawing scores. Gibbons et al. [2] developed the EF score using 800 participants in the ADNI 1 phase of ADNI, and included normal controls, those with AD dementia and those with MCI. The score was normalised such that the population mean was 0 and the standard deviation was 1. The group has provided the EF score for all subsequent participants, including those used in this study, which is available for download from the ADNI website (adni.loni.usc.edu). Of our group of 128 included participants, the mean EF score was 0.15, with a standard deviation of 0.76. Individuals with mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities (MCI-highEF participants) were classified as being one standard deviation above the group mean EF score, resulting in 20 participants with a score above 0.91. Individuals with cognitive impairment with low executive abilities (MCI-lowEF participants) were classified as being one standard deviation below the group mean, resulting in 18 participants with a score below −0.61. Five participants from the MCI-highEF group and two participants from the MCI-lowEF group had to be excluded because of incomplete or corrupted imaging data, resulting in 15 participants in the MCI-highEF group and 16 participants in the MCI-lowEF group.

MRI acquisition

Standard anatomical T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo sequences were acquired (256 × 256 matrix; voxel size: 1.2 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3; inversion time [TI] = 400 ms, repetition time [TR] = 6.984 ms; echo time [TE] = 2.848 ms; flip angle = 11°) in the same session as the diffusion-weighted images (DWI; 256 × 256 matrix; voxel size: 2.7 × 2.7 × 2.7 mm3; TR = 9000 ms; scan time = 9 min; more imaging details can be found at http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/ADNI2_GE_3T_22.0_T2.pdf). Forty-six separate images were acquired for each DTI scan: five T2-weighted images with no diffusion sensitization (b = 0 images) and 41 diffusion-weighted images (b = 1000 s/mm2).

Analysis

Cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation were performed for each structural scan for each participant with the Freesurfer v5.3 image analysis suite, which is documented and freely available for download online (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). The technical details of these procedures are described in prior publications [12, 13]. Gyral based regions of interest (ROIs) were constructed from the segmentation using the atlas described in Desikan et al. [14]. The results were visually inspected for artefact or incomplete segmentation. From the automatically segmented regions we selected four white matter subcortical regions, including the hippocampus and amygdala, for volume comparison between the two groups. We performed a t-test comparison of the volumes of the two groups. We included an automated measurement of white matter hypointensity to describe white matter damage in our analysis. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bejamini-Hochberg method [15] and the number of regions compared.

Ninety-three grey and white matter ROIs from the cortex, sub-cortex, brainstem and cerebellum were chosen from the generated segmentation labels. The DTI data were preprocessed using Freesurfer’s dt_recon function, which performed eddy/motion correction on the DTI files [16]. Freesurfer’s bbregister function registered the structural data files to the DTI files [17]. Then, diffusion values for each ROI were extracted from the registered and corrected data. Fibre tracking files of FA values were generated from the DTI data using DSI Studio, and tract data were generated between each ROI using a seed count of 10,000, an FA threshold of 0.0241, a turning angle of 60 and smoothing parameter of 0.3. The fibre-tracking algorithm implemented in DSI Studio is a generalized deterministic tracking algorithm that uses quantitative anisotropy as the termination index [18]. Tracts of size 20–140 mm were included. A matrix was generated from the output files using a Perl script that included the number of tracts found between each ROI, and values normalised by dividing by seed count (10,000).

Permutation testing was conducted on the networks by shuffling the edges of each network to construct 10,000 new random networks. While the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) score was significantly different between the two groups, we did not control for these differences in our analyses as MMSE contains an executive (working memory) component and therefore is a measure strongly dependent on group assignment. The generated tract matrices and the permutation assignments were imported into MATLAB (Release 2012b, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The following network measures were calculated on both the study data and the randomly generated networks: network size (total number of edges), network density (an average of the total number of connections out of the total possible), global efficiency (a measure of the efficiency of the network, or the inverse of the average path length between all pairs of nodes), assortativity (the preference of nodes to connect to nodes that are similar) and clustering coefficient (the number of triangles completed around a given ROI out of the number possible, or the number of neighbours of a given ROI connected to each other). All measures except for network size were calculated using the Brain Connectivity Toolbox in MATLAB [19]. A threshold of 0.0005 (five tracts) between regions was used to determine the presence of an edge, and to eliminate connections that were incorrectly generated. A t-statistic was generated by measuring the average difference between two groups, and the p-value was calculated by comparing this t-statistic to the t-statistics calculated on the randomly generated networks.

Freesurfer TRACULA (TRActs Constrained by UnderLying Anatomy) software was used to perform tract-based analysis on the preprocessed DTI data [16]. Eighteen major white matter tracts were reconstructed and calculations of FA and radial diffusivity (RD) were performed. The MCI-highEF and MCI-lowEF groups were compared using permutation testing for each measure. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control for the false discovery rate was used to control for number of tracts [15].

Results

Table 1 summarises the participants’ demographic information. There were 15 participants in the MCI-highEF group and 16 participants in the MCI-lowEF group. The average ages between the two groups were different, with an average age of the MCI-highEF group of 70.9 years and the average age of the MCI-lowEF group of 75.9 years; however, the difference was not significant due to the large standard deviation of both groups. MMSE scores are significantly different between the two groups; however, this score reflects an executive component and thus is dependent on group assignment. Table 2 demonstrates a comparison of volume and cortical thickness. None of these measurements show significant difference once corrected for multiple comparisons. In addition, examination of white matter hypointensity shows extremely large standard deviation, showing that this varies widely across both groups. Average network density, the network size and clustering coefficient of the MCI-highEF group were significantly greater than the MCI-lowEF group (Table 3). The t-statistic, showing the difference between the two groups, is reflected, as well as the average of the 10,000 t-statistic permutation with the standard deviation of the generated values. While differences in density and clustering coefficient showed a very small absolute difference, the standard deviations of the randomly generated permutation sets are smaller.

Table 1.

Population statistics for groups with mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities (MCI-highEF) and cognitive impairment with low executive abilities (MCI-lowEF), including gender, age and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score

| Male | Female | Age (mean ± SD) | MMSE (mean)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI-highEF | 8 | 7 | 70.9 ± 7.4 | 28.4 ± 1.5 |

| MCI-lowEF | 10 | 6 | 75.9 ± 8.9 | 25.6 ± 1.7 |

| p-value | 0.09 | 9.9E-05 |

MMSE: one value missing from high EF group in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database, two values missing from low EF group

Table 2.

Select mean volumes and cortical thickness of regions of interest (ROIs), with standard deviations. p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method

| MCI-highEF volume (mm3): mean ± SD | MCI-lowEF volume(mm ): mean ± SD | Adjusted p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left hippocampus | 3,676 ± 661.6 | 3,128.7 ± 323.5 | 0.12 |

| Left amygdala | 1,404.2 ± 238.5 | 1,208.5 ± 321.5 | 0.62 |

| Right hippocampus | 3,676 ± 609.6 | 3,293.2 ± 529.8 | 0.45 |

| Right amygdala | 1,647.1 ± 346.1 | 1,402.2 ± 412.8 | 0.40 |

| White matter hypointensities | 5,211.1 ± 7,939.9 | 9,273.6 ± 8,527.5 | 0.57 |

| MCI-highEF Thickness (mm): mean ± SD | MCI-lowEF Thickness(mm): mean ± SD | Adjusted p-val* | |

| Left caudal anterior cingulate cortex | 2.55 ± 0.71 | 2.52 ± 0.26 | 0.96 |

| Right caudal anterior cingulate cortex | 2.27 ± 0.49 | 2.24 ± 0.13 | 0.67 |

| Left caudal middle frontal cortex | 3.1 ± 0.83 | 3.07 ± 0.4 | 0.85 |

| Right caudal middle frontal cortex | 2.49 ± 0.4 | 2.44 ± 0.17 | 1.0 |

| Left entorhinal cortex | 2.24 ± 0.62 | 2.22 ± 0.15 | 1.0 |

| Right entorhinal cortex | 2.63 ± 0.66 | 2.66 ± 0.23 | 1.0 |

| Left lateral orbitofrontal cortex | 2.36 ± 0.34 | 2.32 ± 0.12 | 0.76 |

| Right lateral orbitofrontal cortex | 2.51 ± 0.25 | 2.67 ± 0.39 | 0.63 |

| Left medial orbitofrontal cortex | 2.21 ± 0.88 | 2.22 ± 0.13 | 0.98 |

| Right medial orbitofrontal cortex | 3.33 ± 0.96 | 3.32 ± 0.51 | 0.98 |

| Left rostral anterior cingulate cortex | 2.38 ± 0.17 | 2.31 ± 0.15 | 0.96 |

| Right rostral anterior cingulate cortex | 2.28 ± 0.98 | 2.28 ± 0.23 | 0.80 |

| Left superior frontal cortex | 2.73 ± 0.38 | 2.81 ± 0.24 | 0.81 |

| Right superior frontal cortex | 2.3 ± 0.96 | 2.31 ± 0.11 | 1.0 |

MCI-highEF Individuals with mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities, MCI-lowEF Individuals with cognitive impairment with low executive abilities, SD standard deviation

Table 3.

Global network measures, compared for each group. All network measures were calculated using a threshold of 0.0005 (>five total tracts between regions of interest (ROIs)), and using permutation testing to assess significance

| Measure | MCI-highEF: mean ± SD | MCI-lowEF: mean ± SD | t: MCI-highEF – MCI-lowEF | Permutation t-statistic: mean ± SD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 567.47 ± 122.2 | 541.38 ± 42.9 | 26.09 | 1.70 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Density | 0.134 ± 0.029 | 0.129 ± 0.010 | 0.005 | −.0016 ± 0.0013 | <0.001 |

| Assortativity | 0.0508 ± 0.064 | 0.0586 ± 0.054 | −0.0079 | −0.004 ± 0.0013 | 0.3835 |

| Global efficiency | 0.4881 ± 0.058 | 0.4858 ± 0.016 | 0.0023 | −2.9e-4 ± 0.0015 | 0.09 |

| Clustering coefficient | 0.0109 ± 1.9e-4 | 0.0069 ± 1.7e-4 | 0.0039 | −1.0e-4 ± 1.5e-4 | <0.001 |

The t-statistic (MCI-highEF (mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities) – MCI-lowEF (cognitive impairment with low executive abilities) is reflected, and the mean of the 10,000 randomly generated t-statistics, with the standard deviation of the population also reflected. The p-value reflects where on the randomly generated t-statistic distribution the measured t-statistic lies

MCI-highEF Individuals with mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities, MCI-lowEF Individuals with cognitive impairment with low executive abilities, SD standard deviation

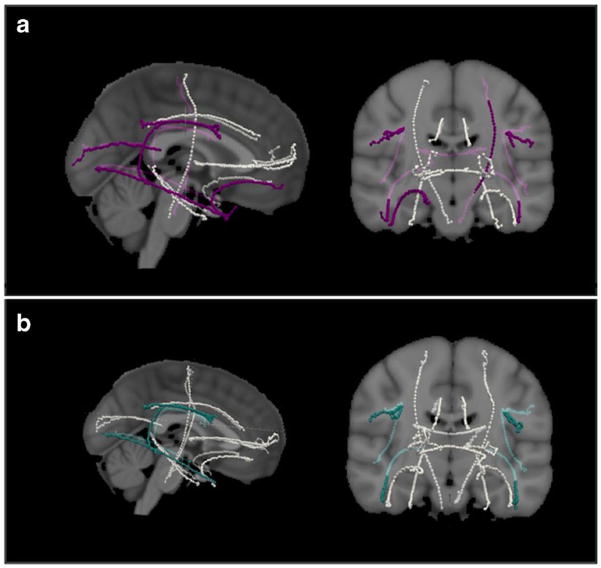

The TRACULA processed data [16] yielded significantly higher FA values in the MCI-highEF group in the inferior and superior longitudinal fasciculi bilaterally, and the MCI-lowEF group showed greater RD values in the corpus callosum, left corticospinal tract, the bilateral superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and the right uncinate fasciculus. The p-values have been corrected for multiple comparisons using the number of tracts. (Table 4; Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Tract-based measurements of average radial diffusivity and fractional anisotropy for major white matter tracts of the brain, as calculated using Freesurfer’s TRACULA

| Radial diffusivity | Fractional anisotropy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| MCI-highEF: mean ± SD | MCI-lowEF: mean ± SD | Adjusted p-value | MCI-highEF: mean ± SD | MCI-lowEF: mean ± SD | Adjusted p-value | |

| Corpus callosum – forceps major | 5.06E-04 ± 8.33E-05 | 6.35E-04 ± 2.64E-04 | 0.041 | 0.59 ± 0.049 | 0.05 ± 0.538 | 0.084 |

| Corpus callosum – forceps minor | 6.50E-04 ± 5.94E-05 | 7.04E-04 ± 1.01E-04 | 0.071 | 0.46 ± 0.054 | 0.05 ± 0.44 | 0.170 |

| Left anterior thalamic radiation | 6.03E-04 ± 5.52E-05 | 6.22E-04 ± 5.33E-05 | 0.592 | 0.42 ± 0.026 | 0.03 ± 0.401 | 0.094 |

| Left cingulum – angular (infracallosal) bundle | 6.76E-04 ± 5.06E-05 | 6.80E-04 ± 3.88E-05 | 1.000 | 0.32 ± 0.041 | 0.04 ± 0.315 | 0.416 |

| Left cingulum – cingulate gyrus (supracallosal) bundle | 5.26E-04 ± 5.66E-05 | 5.53E-04 ± 4.15E-05 | 0.271 | 0.51 ± 0.062 | 0.06 ± 0.49 | 0.171 |

| Left corticospinal tract | 5.18E-04 ± 3.05E-05 | 5.48E-04 ± 3.66E-05 | 0.027 | 0.49 ± 0.017 | 0.02 ± 0.483 | 0.215 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 5.89E-04 ± 5.17E-05 | 6.54E-04 ± 6.84E-05 | 0.001 | 0.48 ± 0.041 | 0.04 ± 0.424 | 0.011 |

| Left superior longitudinal fasciculus – parietal bundle | 5.89E-04 ± 3.60E-05 | 6.42E-04 ± 5.05E-05 | 0.001 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.38 | 0.009 |

| Left superior longitudinal fasciculus – temporal bundle | 5.76E-04 ± 3.23E-05 | 6.23E-04 ± 4.52E-05 | 0.002 | 0.44 ± 0.024 | 0.02 ± 0.414 | 0.012 |

| Left uncinate fasciculus | 6.35E-04 ± 4.39E-05 | 6.63E-04 ± 4.78E-05 | 0.128 | 0.39 ± 0.026 | 0.03 ± 0.372 | 0.054 |

| Right anterior thalamic radiation | 6.67E-04 ± 2.33E-04 | 6.40E-04 ± 4.53E-05 | 1.000 | 0.38 ± 0.064 | 0.06 ± 0.392 | 0.640 |

| Right cingulum – angular (infracallosal) bundle | 6.67E-04 ± 6.55E-05 | 7.44E-04 ± 2.23E-04 | 0.201 | 0.34 ± 0.042 | 0.04 ± 0.316 | 0.183 |

| Right cingulum – cingulate gyrus (supracallosal) bundle | 6.18E-04 ± 2.29E-04 | 5.89E-04 ± 4.32E-05 | 1.000 | 0.44 ± 0.042 | 0.04 ± 0.411 | 0.083 |

| Right corticospinal tract | 5.23E-04 ± 5.01E-05 | 5.35E-04 ± 3.33E-05 | 1.000 | 0.48 ± 0.036 | 0.04 ± 0.478 | 0.621 |

| Right inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 5.82E-04 ± 5.42E-05 | 6.74E-04 ± 1.07E-04 | 0.001 | 0.46 ± 0.042 | 0.04 ± 0.423 | 0.033 |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus – parietal bundle | 5.66E-04 ± 4.91E-05 | 6.12E-04 ± 3.56E-05 | 0.006 | 0.43 ± 0.023 | 0.02 ± 0.397 | 0.009 |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus – temporal bundle | 5.51E-04 ± 3.16E-05 | 6.02E-04 ± 4.20E-05 | 0.001 | 0.44 ± 0.029 | 0.03 ± 0.412 | 0.033 |

| Right uncinate fasciculus | 6.19E-04 ± 4.44E-05 | 6.67E-04 ± 4.37E-05 | 0.008 | 0.39 ± 0.032 | 0.03 ± 0.375 | 0.116 |

p-values were calculated using permutation testing, and were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control for the false discovery rate. All mean values and standard deviations, along with adjusted p-values are reported, with significant differences reflected in bold

Fig. 1.

Tract values calculated using TRACULA [16] to determine fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity (RD) of the 18 major tracts of the brain, represented on the MNI brain. (a) Tractography, with tracts showing significantly greater RD in the cognitive impairment with low executive abilities (MCI-lowEF) group shown in purple. These include the corpus callosum-forceps major, left corticospinal tract, bilateral superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi, and the right uncinate fasciculus. (b) Tracts with significantly greater FA in the mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities (MCI-highEF) group shown in teal. These include the bilateral inferior and superior longitudinal fasciculi

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that individuals with greater executive abilities in the setting of MCI have greater FA and lower RD, reflecting better white matter integrity in many of the large white matter tracts of the brain as well as a larger, more efficient network overall than those with lesser executive abilities in the setting of MCI. The MCI-highEF group had on average a larger diffusion network with greater density, global efficiency and clustering coefficient. Examination of white matter network changes in AD dementia have shown widespread network disruptions [7] and decreased topological organisation [8]. Decreased FA in a number of tracts has been shown to be a marker of AD dementia, relating changes in diffusive properties of white matter to impairment in AD dementia [20]. FA has been shown to be less sensitive to the early changes of mild cognitive impairment [21]; however, the significant differences that we found in FA between those with high and executive abilities suggests that FA changes in MCI may be related to executive deficits [22]. Our study confirms that the white matter changes found previously in AD may manifest earlier as a function of diminished executive abilities in MCI, and that these diminished abilities are likely to accompany early white matter changes in specific white matter tracts.

The lack of significant differences of cortical thickness and subcortical volume measurements suggests that tract-based differences are limited to diffusive properties of the white matter and gross structural differences are not contributing to the executive deficit differences between these groups. While others have shown that hippocampal volume differences may be seen between normal participants and those with MCI [9], our results demonstrate that there are not significant differences between those with low and high executive abilities and MCI. In addition, the lack of differences in cortical thickness in frontal regions suggests that changes in executive abilities are related to changes in white matter diffusivity rather than to grey matter differences. We included a measurement of white matter hypointensity to investigate any global structural damage differences between the two groups. We used white matter hypointensities on T1-weighted imaging in lieu of T2-weighted white matter hyperintensities, which are thought to reflect late-stage changes after vascular incidents [23]. The standard deviation of these groups was quite large, with a non-uniform distribution across the entire population. The differences between the white matter hypointensities between the two groups were not significant and previous vascular episodes are likely non-contributory to our results.

The parietal portion of the superior longitudinal fasciculus connects the parietal region with the frontal lobe [24]. The diffusion properties of this tract have been related to executive abilities [3]; the decreased FA and increased RD found in the MCI-lowEF group affirms the importance of this tract to executive function. The tractography differences noted between the MCI-highEF group and the MCI-lowEF group in the superior longitudinal fasciculus have been described not only in AD dementia [20], but also accompanying cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease and chronic hypertension. While the pathophysiology of these diseases may be different, it is important to note that differences in these regions accompany similar diminished executive changes [25, 26]. As such, it may be that a disruption in the efficiency of this tract in MCI is most indicative of whom will go on to develop dementia. However, this was not the only tract found to be different between the two groups. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus, as well as the right left corticospinal tract, the forceps major of the corpus callosum and the right uncinate fasciculus all demonstrated increased RD in the MCI-lowEF group. Gold et al. [5] described widespread increases in RD in a pre-AD state, which may be related to breakdown of myelin. While the regions we found to be significantly different may not be regions traditionally thought of as being involved in executive abilities, executive tasks can be complex enough to require the whole brain, and these differences are likely due to global changes during disease progression. Because we corrected for multiple comparisons, it is unlikely that these changes would be due to chance.

Limitations of our study include a lack of correction for native abilities. It may be that some individuals have a native stronger white matter network but this needs further investigation. Similarly, higher pre-morbid IQ may be the result of better network connections, another notion that needs further investigation as this is not likely to be a simple linear relationship given the broad-based types of education that exist. In a study of this type it is impossible to control for the types of life experiences that are likely to have an impact on the depth and breadth of one’s executive abilities. However, these limitations indicate why one might have better executive abilities, not how they relate to disease.

We have described a number of measures that correlate with differences in MCI-highEF versus MCI-lowEF. A natural next step will be to attempt to follow these changes longitudinally to see how changes in these measures relate to a worsening of AD pathology. Gibbons et al. [2] demonstrated that the EF score is a significant predictor of those who will progress to AD, and our next step would be to discover if the described network measures are similarly predictive. Our proposed technique may not only describe who may be at increased risk for progression to AD based on white matter network measures, but also the regional changes that contribute to executive behavioural deficits shown in MCI.

Key Points.

The MCI high executive ability group yielded a larger network.

The MCI high executive ability group had greater FA in numerous tracts.

White matter reserve may confer greater protection of executive abilities.

Loss of executive reserve may lead to greater impairment in AD dementia.

Acknowledgments

Funding Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organisation is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- ADNI

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

- DTI

Diffusion tensor imaging

- EF

Executive function

- FA

Fractional anisotropy

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MCI- highEF

Individuals with mild cognitive impairment with high executive abilities

- MCI-lowEF

Individuals with cognitive impairment with low executive abilities

- MMSE

Mini-Mental Status Examination

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- RD

Radial diffusivity

- ROI

Region of interest

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Guarantor The scientific guarantor of this publication is Ron Killiany, PhD.

Conflict of interest The conflicts of interest are as follows: Dr. Budson has been an investigator for clinical trials for the following companies: AstraZenica, Hoffmann-La Roche, Eli Lily, FORUM Pharmaceuticals, and Neuronetrix. Dr. Moss serves as a consultant for Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Killiany is funded on two research grants from Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Mian is a shareholder of Boston Imaging Core Lab.

Statistics and biometry Danielle Farrar, MA performed the statistical analysis for this paper, with input from Dr. Ronald J. Killiany.

Informed consent Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study.

Ethical approval Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Study subjects or cohorts overlap This study was performed using data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Other studies published utilizing this dataset can be found at http://www.adni-info.org/Scientists/ADNIScientistsHome/ADNIPublications.html

- retrospective

- cross-sectional study

- multicentre study

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

References

- 1.Aretouli E, Brandt J. Everyday functioning in mild cognitive impairment and its relationship with executive cognition. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:224–233. doi: 10.1002/gps.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, et al. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behavior. 2012;6:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettcher BM, Mungas D, Patel N, et al. Neuroanatomical substrates of executive functions – Beyond prefrontal structures. Neuropsychologia. 2016;85:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold BT, Johnson NF, Powell DK, Smith CD. White matter integrity and vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: preliminary findings and future directions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1822;2012:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowrangi MA, Lyketsos CG, Leoutsakos JS, et al. Longitudinal, region-specific course of diffusion tensor imaging measures in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.05.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daianu M, Jahanshad N, Nir TM, et al. Breakdown of brain connectivity between normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease: a structural k-core network analysis. Brain Connect. 2013;3:407–422. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo C, Wang P, Chou K, Wang J, He Y, Lin C. Diffusion tensor tractography reveals abnormal topological organisation in structural cortical networks in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16876–16885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4136-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desikan R, Cabral H, Hess C, et al. Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:2048–2057. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi M, Kim H, Gim S, et al. Differences in cognitive ability and hippocampal volume between Alzheimer’s disease, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and healthy control groups, and their correlation. Neurosci Lett. 2016;620:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng D, Sun H, Dong X, et al. Executive dysfunction and gray matter atrophy in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischl B, Salat D, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischl B, Kouwe A, Destrieux C, et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yendiki A, Panneck P, Srinivasan P, et al. Automated probabilistic reconstruction of white-matter pathways in health and disease using an atlas of the underlying anatomy. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2011.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grieve SM, Williams LM, Paul RH, Clark CR, Gordon E. Cognitive aging, executive function, and fractional anisotropy: a diffusion tensor MR imaging study. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007:226–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh F, Verstynen TD, Wang Y, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Tseng WI. Deterministic diffusion fiber tracking improved by quantitative anisotropy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goveas J, O’Dwyer L, Mascalchi M, et al. Diffusion-MRI in neurodegenerative disorders. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33:853–876. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acosta-Cabronero J, Nestor PJ. Diffusion tensor imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: insights into the limbic-diencephalic network and methodological considerations. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:143. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowrangi MA, Okonkwo O, Lyketsos C, et al. Atlas-based diffusion tensor imaging correlates of executive function. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:585–598. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wardlaw J, Valdés-Hernández M, Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of?: relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc: Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;4:e001140. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamali A, Flanders AE, Brody J, Hunter JV, Hasan KM. Tracing superior longitudinal fasciculus connectivity in the human brain using high resolution diffusion tensor tractography. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:269–281. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0498-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan GW, Firbank MJ, Yarnall AJ, et al. Gray and white matter imaging: a biomarker for cognitive impairment in early Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 2016;31:103–110. doi: 10.1002/mds.26312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Liang Y, Chen Y, et al. Disrupted frontoparietal network mediates white matter structure dysfunction associated with cognitive decline in hypertension patients. J Neurosci. 2015;35:10015–10024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5113-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]