Abstract

This study analyzed the health of migrants in 4 types of neighborhood in the city of Guangzhou in China. The research shows that the health of internal migrants in urban villages and private housing neighborhoods is much better than those living in older inner city neighborhoods (which are known as jiefang shequ) and unit neighborhoods (which are known as danwei). The reasons behind this are the facts that the migrants in urban villages tend to be relatively young and there tend to be better social and economic conditions in the private housing neighborhood. Moreover, among the 4 kinds of neighborhood, the gap between psychological health and physical health is the largest in urban villages. In addition, migrants who are younger, have better working conditions, and have higher levels of education have better health scores, and they tend to have more friends in the city, larger houses, better insurance, and more satisfaction with their neighborhood relationships, and they tend to be better adapted to urban life. As for the determinants of health, individual characteristics, community factors, and insurance are the most important factors. Specifically, individual age and age of housing have negative influences on physical health while insurance has a positive effect. This study shows that the type of neighborhood that migrants live in has a great impact on their psychological health, which can be improved by promoting neighborhood environments. Last, we propose that it is necessary to implement different strategies in different communities.

Keywords: migrant, health, neighborhood, Guangzhou, China

Introduction

Since the implementation in 1978 of the program of economic reforms known as the “Reform and Opening Up” policy, China has experienced massive population mobility from rural to urban areas. However, after 30 years, the living conditions of internal migrants in China are often poor.1,2 Subject to urban and rural dual structure, which was formed during the period of the planned economy, although there is a large number of migrants moving to cities, most of them lack basic social protection.3 Most of these migrants live in urban villages and the run-down older inner city neighborhoods, which lack public facilities.4 Poor living environments and a lack of government support have a negative impact on the health of migrants.5,6 Therefore, it is important to carry out research into the health issues faced by China’s migrants.

Qi et al7 used data from the Chinese Mobility and Health Survey and found that the health of migrants is better than the health of the rural population that did not migrate. However, the authors also found that the health of the migrants who return home is lower than before, which leads to the poorer health seen in the rural population compared with that seen in the urban population. After moving to cities, migrants tend to face more health risks than the local population, as they tend to work in jobs that are more difficult and more dangerous.8 Many migrants from rural areas are young and healthy, but when they get older or become ill, they return to the rural areas. Therefore, the health risks and disease burden is transferred to rural areas, which exacerbates the demand for health resources in rural areas.9 In addition, studies have suggested that the health of migrants in China is affected by intergenerational effects, ie, migrants whose parents have poorer health or greater levels of work pressure are more likely to have poor physical health.10 Therefore, narrowing the expanding gap between the rich and poor and reducing health inequity is an important task for modern China.

Regarding the factors that influence health, socioeconomic status (SES), living and working conditions, and other regional development disparities are important determinants.11,12 Lynch et al13 found that children’s family environments have a large impact on their health behaviors and psychological characteristics in adulthood. In addition, Robert and House14 found that there is a significant positive correlation between liquid assets and the health status of those who are middle-aged and elderly. Lynch et al15 studied data from 282 metropolitan areas in the United States and found that the greater the income gap in each area, the higher mortality rate. Many individuals with high SES experience health problems largely in the later stages of life, but those with lower SES often suffer from a rapid decline in health in middle age.16 With increasing age, the differentiation between the health of people from different socioeconomic backgrounds becomes more obvious. Therefore, Lynch et al13 believe that the government and society in the United States should recognize the need to improve public health as part of the economic policy, which would be an important measure to enhance the health of the population.

Work status is also an important factor that helps to explain the health of individuals. For example, unemployment has a negative impact on people’s health.17 Grayson’s study in Canada found that, when people have the same level of exercise, the unemployed have poorer health compared with the working population.18 Stuckler et al19 found that for every 1% increase in unemployment in Europe, there was a 0.79% rise in suicides among those aged below 65 years, and every $10 per person invested in labor market programs reduced the effect of unemployment on suicides by 0.038%.

Housing and community both have a direct impact on the health of residents, for example, damp and moldy living conditions have an adverse effect on health.20,21 Housing tenure also has an effect on the health of residents. Ellaway and Macintyre22 found that different types of housing tenures expose people to different levels of health hazards. Gabe and Williams23 found that there is a J-shaped relationship between housing density and psychological symptoms, ie, low as well as high levels of crowding are detrimental to psychological health. In addition, the health of residents in different communities can be very different. The health of residents living in poor communities is generally lower than that of those living in affluent communities. High crime rates and chaotic living conditions in poor communities are important factors that affect the health of residents.24 Aneshensel and Sucoff25 analyzed a community-based sample of 877 adolescents in Los Angeles County and found that youth in low-SES neighborhoods perceived more hazards in their local environment than those in high-SES neighborhoods.

It should be noted that the impacts of social and economic conditions and the impacts of the physical environment on health do not only act in a single direction. People often take proactive measures to change their poor living environments in order to improve their health and that of their families. Kearns and Parkes26 found that dissatisfaction and annoyance with a given neighborhood significantly increases the likelihood of residential mobility. Areas that attract migrants from other areas will, in the long run, develop healthier populations.27

Building healthy spaces is an important way to maintain or enhance the health of individuals and families.28 Several studies have found that transnational migrants often maintain their original customs in order to provide healthy living spaces for their families.29 Dyck and Dossa30 found that migrant women from India and Afghanistan in Canada continued to practice their customs related to food preparation and consumption, traditional healing, and religious observance, which enhanced the physical, social, and symbolic dimensions of their living environment for their families.

Overall, migrant is one of the main research objects of the researches on health. And the existing research on factors that affect health has largely been carried out in the West and in China. From the above, we can see that personal factors, work-related factors, housing factors, medical and pension insurance factors, community factors, and urban life factors are the main factors, which affect migrants’ health. Still, it is valuable to analyze the health of migrants from geographical and urban planning perspective in China’s context. In this article, our focus is on the neighborhood. We try to answer the following questions: How is the status of health of migrants in different neighborhoods? and What are the influences of neighborhood on the health of migrants? This article contributes to the literature on health of migrants in China by first investigating the impact of neighborhood. The next section introduces the data collection and methods. Third section is empirical findings from the Guangzhou survey. The article concludes with a summary of key findings and a discussion.

Data and Methods

In this article, we analyzed data from the urban areas of the Chinese city of Guangzhou. The data concerned the health of migrants, where migrants refer to those who were registered as temporary residents in Guangzhou. The main data set used in this article was collected via a questionnaire survey that was conducted in Guangzhou from September to November 2015.

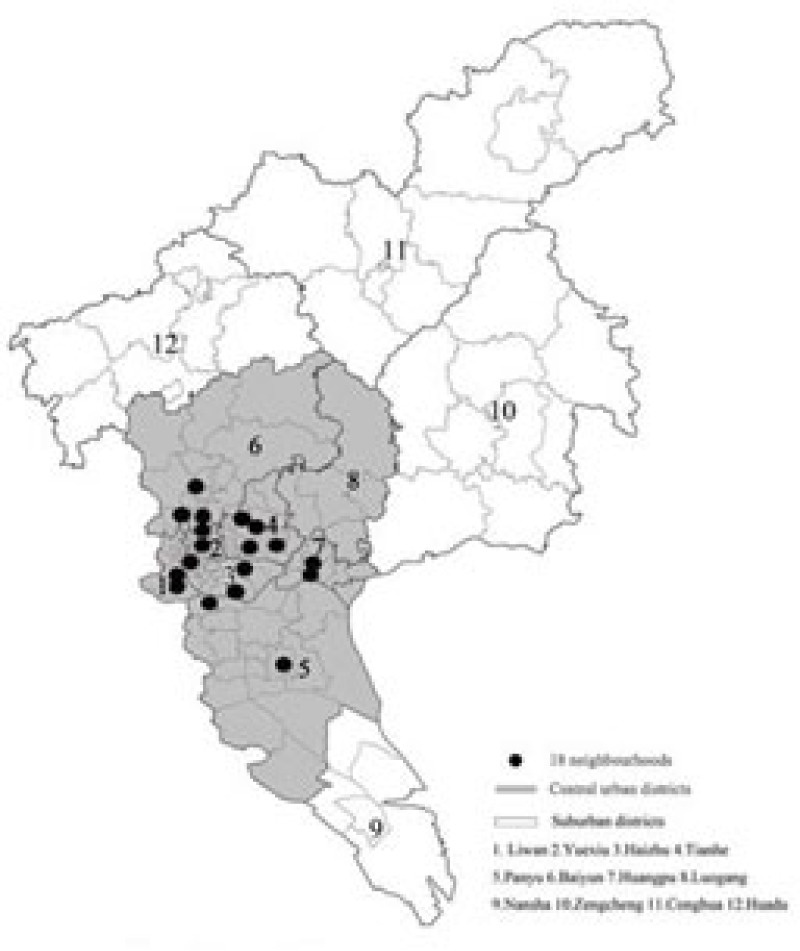

We explored data from 4 types of neighborhood: older inner city neighborhood (which are known as jiefang shequ), unit neighborhoods (which are known as danwei, or “work units,” which used to be integrated work and living spaces that acted as the basic unit of urban organization for the state), urban villages, and private housing neighborhoods. Figure 1 shows the locations of the 18 sampled neighborhoods. Among them, we collected 61 valid questionnaires from migrants in older inner city neighborhoods, 67 from migrants in unit neighborhoods, 115 from migrants in urban villages, and 84 from migrants in private housing neighborhoods.

Figure 1.

Eighteen sampled neighborhoods in the central urban districts of Guangzhou.

We collected data on migrants’ self-assessed physical and mental health scores, which were measured on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing the worst health and 5 representing the best health. To reflect the health of migrants more accurately, we also took the average value between physical health scores and mental health scores as “overall health score.” Based on the reviews and analysis, data were collected on the following variables:

Personal factors: gender (male or female), age (years), length of residence (years), marital status (unmarried, married, or others), education level (primary school and below, high school, or college and above) and annual household income

Work-related factors: satisfaction with work score, daily working hours, number of days of work per month, type of workplace (government department, private enterprise, or self-employed), farming duration, frequency of changing jobs, and type of work (agricultural work or nonagricultural work)

Housing factors: size of housing (m2), age of housing, type of household (family household or nonfamily household), housing ownership (owned housing or nonowned housing), and age of housing (years)

Medical and pension insurance factors: urban workers’ basic medical insurance, new rural cooperative medical insurance, private enterprise employees’ basic pension insurance, and new rural social pension insurance

Community factors: community attachment score, satisfaction with neighborhood score, community awareness score, and community quality of life score

Urban life factors: urban lifestyle fitness score, quality of diet score, satisfaction with Guangzhou score, number of close friends in the city, and wishes to return home

We used logistic regression models to quantify the effects of personal factors, work-related factors, housing factors, community factors, insurance factors, and urban life factors on the migrants’ health.

Results

Health of Migrants in Different Neighborhoods

As shown in Table 1, migrants in urban villages and private housing neighborhoods had higher self-assessed physical health scores, which were 4.51 and 4.46, respectively, and migrants in older inner city neighborhoods and unit neighborhoods had lower levels of health, with scores of 4.15 and 4.27, respectively. Regarding self-assessed mental health scores, a similar pattern was exhibited, with migrants in urban villages and private housing neighborhoods having higher scores compared with migrants in older inner city neighborhoods and unit neighborhoods. Regarding the overall health scores, migrants in urban villages and private housing neighborhoods had higher scores (both had scores of 3.99) compared with those in older inner city neighborhoods and unit neighborhoods (both had scores of 3.76).

Table 1.

Health of Migrants in Different Neighborhoods.

| Type of neighborhood | Total | Older inner city neighborhood | Unit neighborhood | Urban village | Private housing neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-assessed physical health score | 4.39 | 4.15 | 4.27 | 4.51 | 4.46 |

| Self-assessed mental health score | 3.41 | 3.37 | 3.26 | 3.44 | 3.51 |

| Overall health score | 3.90 | 3.76 | 3.76 | 3.99 | 3.99 |

| Percentage of individuals with good healtha | 53.5 | 37.7 | 47.8 | 61.7 | 58.3 |

Good health is defined as an overall health score greater than the sample mean.

Using the sample mean of the overall health score (3.90) as a threshold for good health, we calculated the proportions of migrants in each of the 4 neighborhoods who had health scores of greater than and less than the sample mean, which were used to define those in “good health” and “poor health,” respectively. The highest percentage of those with good health was 61.7%, which was for migrants in urban villages. The second highest percentage was 58.3%, which was for migrants in private housing neighborhoods. The lowest percentage, 37.7%, was for migrants in older inner city neighborhoods.

The association between various factors and the migrants’ health were analyzed, as shown in Table 2. Regarding gender, the health score for males was higher than that for females. The proportion of males with good health was 62%, while that for females was 43%. Regarding marital status, the proportion of unmarried individuals with good health was 61%, while that for married individuals was 52%. There were also health differences by age and length of residence. For those in poor health, the mean age was 38 years and the mean length of residence was 13 years, and for those in good health, the mean age was 35 years and the mean length of residence was 13 years. In addition, the higher the migrants’ education level, the higher the health scores. For migrants who had primary education and below, 41% had good health. For migrants who had college education and above, 61% had good health.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Migrants’ Health.

| Poor healtha | Good healtha | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 38% | 62% |

| Female | 57% | 43% |

| Type of work | ||

| Agricultural work | 47% | 53% |

| Nonagricultural work | 45% | 55% |

| Mean age (years) | 38 | 35 |

| Mean frequency of changing jobs | 1.22 | 1.25 |

| Type of workplace | ||

| Government department | 45% | 55% |

| Private enterprise | 52% | 48% |

| Self-employed | 43% | 57% |

| Urban workers’ basic medical insurance | ||

| Yes | 43% | 57% |

| No | 49% | 51% |

| Private enterprise employees’ basic pension insurance | ||

| Yes | 44% | 56% |

| No | 48% | 52% |

| Mean size of housing (m2) | 42.82 | 49.37 |

| Mean satisfaction with work score | 3.67 | 3.66 |

| Mean urban lifestyle fitness score | 4.05 | 4.21 |

| Mean satisfaction with neighborhood score | 3.76 | 3.86 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 39% | 61% |

| Married | 0.48% | 52% |

| Type of household | ||

| Family household | 47% | 53% |

| Nonfamily household | 44% | 56% |

| Mean length of residence (years) | 13.0 | 11.9 |

| Mean daily working hours | 8.76 | 9.25 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary school | 59% | 41% |

| High school | 47% | 53% |

| College | 39% | 61% |

| New rural cooperative medical insurance | ||

| Yes | 42% | 58% |

| No | 49% | 51% |

| New rural social pension insurance | ||

| Yes | 48% | 52% |

| No | 46% | 54% |

| Number of close friends in the city | 17.5 | 21.2 |

| Mean quality of diet score | 4.14 | 4.13 |

| Mean satisfaction with Guangzhou score | 3.98 | 3.97 |

| Mean community attachment score | 3.63 | 3.70 |

Poor and good health are defined as overall health scores lower than and greater than the sample mean, respectively.

Regarding work-related factors, for those migrants with poor health, the mean of their daily working hours was 8.76 h, while those with good health worked a mean of 9.25 h. Regarding the type of workplace, 55% and 57% of migrants who worked in government departments and those who were self-employed had good health, respectively. Migrants who worked in private enterprises had comparatively lower health scores.

A higher proportion of migrants who had social security-related insurance had good health, apart from those who had new rural social pension insurance, which indicates that a sound social security system can improve migrants’ health. Migrants with good health had mean house sizes of 49.37 m2 and those with poor health had mean house sizes of 42.82 m2. In addition, migrants who had good health had larger numbers of friends, better urban lifestyle fitness scores, and higher satisfaction with neighborhood scores.

Factors That Influence Migrants’ Health

First, using the overall health score as the dependent variable and the personal factors as control variables in each of the models, the following 6 regression models were estimated: a personal factors model, a work-related factors model, a housing model, a community model, an insurance model, and an urban life model. Subsequently, the statistically significant independent variables in each of the 6 models were combined in a comprehensive model, and the determinants of the migrants’ health scores were explored.

As shown in Table 3, in the personal factors model, gender and age were statistically significant. The males’ health scores were higher than females’, which may indicate that males have more adaptability to urban life and work pressure. In contrast, age had a statistically significant negative relationship with health scores. Except in the work-related factors model, the gender and age variables had similar effects in the other 4 models.

Table 3.

Regression Analyses of Overall Health Scores of Migrants in Guangzhou.

| Variable | Model 1: Personal factors | Model 2: Work-related factors | Model 3: Housing | Model 4: Community | Model 5: Insurance | Model 6: Urban life | Model 7: Comprehensive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (ref: female) | 0.176** | 0.149* | 0.182*** | 0.161** | 0.174** | 0.158** | 0.140** |

| Age | −0.012** | −0.008 | −0.012** | −0.013*** | −0.012** | −0.013*** | −0.008** |

| Length of residence | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Marital status (ref: married and others) | −0.087 | −0.093 | −0.101 | −0.098 | −0.063 | −0.084 | |

| Education level | 0.021 | 0.017 | −0.003 | −0.005 | 0.014 | 0.011 | |

| Annual household income | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | |

| Satisfaction with work | 0.029 | ||||||

| Daily working hours | 0.017 | ||||||

| Number of days of work per month | −0.024* | −0.007 | |||||

| Type of workplace (ref: government department) | |||||||

| Private enterprise | −0.016 | ||||||

| No unit or self-employed | 0.102 | ||||||

| Farming duration | −0.012* | −0.008 | |||||

| Size of housing | 0.002* | 0.001 | |||||

| Age of housing | −0.043* | −0.032 | |||||

| Type of household (ref: family household) | 0.067 | ||||||

| Housing ownership (ref: nonowned housing) | −0.053 | ||||||

| Community attachment score | 0.020 | ||||||

| Satisfaction with neighborhood score | −0.030 | ||||||

| Community awareness score | 0.093** | 0.057 | |||||

| Community quality of life score | 0.074** | 0.065** | |||||

| Urban workers’ basic medical insurance (ref: uninsured) | 0.341* | 0.112 | |||||

| New rural cooperative medical insurance (ref: uninsured) | 0.205* | 0.161* | |||||

| Private enterprise employees’ basic pension insurance (ref: uninsured) | −0.185 | ||||||

| New rural social pension insurance (ref: uninsured) | −0.085 | ||||||

| Urban lifestyle fitness score | 0.113** | 0.034 | |||||

| Wishes to return home | 0.050 | ||||||

| Number of close friends in the city | 0.001 | ||||||

| Constant | 4.100*** | 4.399*** | 3.894*** | 3.678*** | 4.019*** | 3.556*** | 3.413*** |

| N | 327 | 327 | 327 | 327 | 327 | 327 | |

| df | 6 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | |

| F | 4.535*** | 3.294*** | 4.289*** | 5.559*** | 3.689*** | 4.635*** | |

| R2 | .078 | .121 | .119 | .150 | .105 | .117 | |

P < .1. ** P < .05. ***P < .01.

In the work-related factors model, the number of days worked per month and farming duration were statistically significant, and they both had negative associations with the health scores. The effect of the number of days worked per month reveals that work intensity influences health, while the variable on farming duration reveals that there may be adaptability issues when migrants transfer from agricultural to nonagricultural employment.

In the housing model, size of housing and age of housing were important factors. The smaller the housing and the older the housing, the greater the negative impact on migrants’ health scores. As research in the West has shown, improvements to people’s living situations can improve their health.31 Similarly, the community has also been confirmed to be an important dimension that can influence migrants’ health.32

In the community model, community awareness and community quality of life had a positive impact on migrants’ health scores. Therefore, enhancing community awareness (e.g., by setting up community bulletins, other community notification systems, and community events) and the quality of life in the community may contribute to improving migrants’ health. In the insurance model, the variables concerning urban workers’ medical insurance and new rural cooperative medical insurance were statistically significant, as medical insurance promotes health. In the urban life model, the degree of lifestyle adaptation score had a statistically significant impact. Adaptation to urban life tends to help to improve health.

In the comprehensive model, gender, age, community quality of life, and rural cooperative medical insurance were the most important factors. That is to say, personal characteristics, community factors, and insurance are the most prominent factors that influence migrants’ health.

Subsequently, physical health scores and mental health scores were used as the dependent variables in 2 regression analyses which tested the effects of the 27 variables from the 6 dimensions (i.e., personal factors, work-related factors, housing factors, community factors, insurance factors, and urban life factors). A forward selection method was employed in the regression analyses.

In the physical health score model, migrants’ health scores were statistically significantly influenced by age, age of housing, pension and medical insurance, and type of workplace. Among these, age and housing completion time had a negative impact on the physical health scores, while the new rural social pension insurance and the urban workers’ basic medical insurance each had a positive impact on the physical health scores. Compared with those working in government departments, migrants who worked in private enterprises had lower health scores, which is likely to have been due to the work intensity.

In the mental health score model, community quality of life and community awareness were important factors that influenced migrants’ mental health scores. Therefore, enhancing the quality of communities may improve migrants’ health. The length of residence and the new rural social pension insurance have negative impacts on health. For migrants who had lived in Guangzhou for a long period of time, the willingness to settle down in Guangzhou was very high, but there are high levels of economic pressure in Guangzhou so migrants often face high levels of psychological pressure. Meanwhile, although the new rural social pension insurance is handled, willingness to return home is not high, which resulted in the negative impact of this variable. Moreover, in terms of migrants mainly engaged in labor-intensive industries, their daily working hours are proportional to their income and greater income helps to relieve life pressures.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study measured and analyzed older inner city neighborhoods, unit neighborhoods, urban villages, and private housing neighborhoods in Guangzhou. Regarding self-assessed physical and mental health scores, the scores of migrants in urban villages and private housing neighborhoods were higher than those of migrants in older inner city neighborhoods and unit neighborhoods. The migrants in the urban villages tend to be young, and in the private housing, neighborhoods tend to have better SES, which are important reasons behind these phenomena. Urban villages and private housing neighborhoods located at prosperous areas of cities are emerging residential communities after the reform and opening up, while older inner city neighborhoods and unit neighborhoods mostly formed in the planned economy era. The health level of migrants in the former neighborhoods is higher than that of migrants in the latter neighborhoods, which partly reflects that the growth and the development of economy influence the health level of migrants in a positive way.

Regarding the different dimensions of health, migrants’ self-assessed mental health scores were far lower than their self-assessed physical health scores. Migrants in urban villages had the largest gap between the 2 scores, and the gap between the scores in different neighborhoods decreased from unit neighborhoods to private housing neighborhoods to older inner city neighborhoods.

Males had better health than females, and there was a higher proportion of younger people with good health compared with older people. The migrants’ education levels had a positive correlation with their health scores. Migrants who worked in government departments and those who were self-employed had higher health scores than migrants who worked in private enterprises. Compared with private enterprises, social welfare of governmental agency unit is better. In the period of the planned economy, the social welfare of employees in China is mainly affected by their work units or the related rules and institutions. The social status of different employees with different social welfare varied a lot. However, in the marketization reform process, social welfare of employees in different employment sectors still has a large difference. Narrowing the welfare gap between different employment sectors is still an important part of China’s reform.

Migrants whose health scores were higher tended to have more comprehensive insurance, larger housing, larger numbers of friends, better urban lifestyle fitness scores, and greater levels of satisfaction with their neighborhoods. Personal characteristics, community factors, and insurance are the most prominent factors that influence migrants’ health scores. Among the influential factors associated with physical health scores, age, size and age of housing, pension insurance, and medical insurance are important. Age of housing had a negative impact, while insurance had a positive impact on health scores. Among the influential factors associated with mental health scores, community was an important factor. Health insurance is one of the important influence factors on health of migrants. In the context of China’s current special background, registered residence (known as hukou) is a threshold for migrants to become urbanite.33 In this case, improving migrant’s health insurance means a lot for narrowing social welfare between urban and rural migrants. Most of the rural migrants in city are at the bottom of the heap. Because the social welfare system is not perfect, when they get injured or are suffering from diseases such as pneumoconiosis, they will lose the ability and opportunity to continue to work in urban area. They have to return to the rural areas (their hometown), thus lowering the health level of rural places. It should be noted that rural areas where the social welfare system is less developed face the biggest health risk. Cities have better welfare system, while the government investments of the public services in rural areas are far from enough, which is also the current controversial China’s dualistic urban-rural structure.

The findings show that, in order to improve migrants’ health, strategies should be targeted to the different types of neighborhood. Enhancing the quality of communities and the environment may improve migrants’ health. Migrants in private housing neighborhoods have relatively high SES, and the market-oriented approach in these neighborhoods may help to protect and improve their health. However, migrants in the other 3 neighborhoods, especially in the urban villages and the older inner city neighborhoods, should be given more support from the government and the wider community. The quality of housing, the environment, and the public facilities need to be gradually upgraded. In addition, improvements to the insurance systems and the promotion of social integration are important ways to enhance migrants’ health. In this article, we use subjective variables to study the health of migrants from the perspective of migrants. This study reflects the respondents’ own subjective understanding of their own health. Of course, we can also see the differences between this subjective evaluation and objective evaluation. Subjective evaluation may not be a true reflection of the real health of the respondents. Taking health assessment index like body mass index, blood pressure, lipids, etc, as evaluation criteria may reflect a more scientific reflection of migrants’ health. But as a self-health evaluation research, this study is worth trying. In the future, based on the research, we will use objective indicators to conduct more objective studies of the migrants’ health. In addition, there are a lot of health issues that still need to be explored, especially regarding the effects of different neighborhood and environments. The effect of environmental strategies on migrants’ health should be studied further using specific neighborhood case studies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China [grant number 2242016S10010, 2242015S10011].

References

- 1. Wang C. The relationship between social identity and urban integration of the new generation of rural migrants. Sociol Stud. 2001;3(1):63-76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen H, Liu Z, Li Z. Social integration of neo-immigrants in urban China: a case study of six large cities. Mod Urban Res. 2015;6:112-119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang L. Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power, and Social Networks Within China’s Floating Population. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu Y, Li Z, Liu Y, Chen H. Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, China: agency, everyday practice and social mobility. Urban Stud. 2015;52(16):3086-3105. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kong X. Thoughts on the prospectiveness of local development and urban planning profession in the healthy city movement. Urban Stud. 2005;12(2):5-11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yue J, Li X. Health consciousness and health service utilization of the floating population in the Pearl River Delta area: a community perspective. J Public Manage. 2014;11(4):125-135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qi Y, Niu J, William M, Donald T. China’s internal migration and health selection effect. Popul Res. 2012;36(1):102-112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ji Y, Yuan Y, Su C, Chang C. Comparative study on health status and health services utilization of rural-urban young migrants and rural youths. Popul J. 2013;2:90-96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niu J. Migration and its impact on the differences in health between rural and urban residents in China. Soc Sci China. 2013;2:46-63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 10. He H, Ren D. Health integration and its determinants of the new generation migrant workers. Popul Res. 2014;38(6):92-103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kearns RA, Joseph AE. Space in its place: developing the link in medical geography. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(6):711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tunstall H, Shaw M, Dorling D. Places and health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(1):6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Why do poor people behave poorly? variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic lifecourse. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(6):809-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robert S, House JS. SES differentials in health by age and alternative indicators of SES. J Aging Health. 1996;8(3):359-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, et al. Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(7):1074-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. House JS, Lepkowski JM, Kinney AM, Mero RP, Kessler RC, Herzog AR. The social stratification of aging and health. J Health Soc Behav. 1994;35(3):213-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brenner MH, Mooney A. Unemployment and health in the context of economic change. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(16):1125-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grayson JP. Health, physical activity level, and employment status in Canada. Int J Health Serv. 1993;23(4):743-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gemmell I. Indoor heating, house conditions, and health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(12):928-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Platt SD, Martin CJ, Hunt SM, Lewis CW. Damp housing, mould growth, and symptomatic health state. BMJ. 1989;298(6689):1673-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellaway A, Macintyre S. Does housing tenure predict health in the UK because it exposes people to different levels of housing related hazards in the home or its surroundings? Health Place. 1998;4(2):141-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gabe J, Williams P. Is space bad for your health? The relationship between crowding in the home and emotional distress in women. Sociol Health Illn. 1986;8(4):351-371. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37(4):293-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kearns A, Parkes A. Living in and leaving poor neighbourhood conditions in England. Hous Stud. 2003;18(6):827-851. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verheij RA, Van de Mheen HD, de Bakker DH, Groenewegen PP, Mackenbach JP. Urban-rural variations in health in The Netherlands: does selective migration play a part? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(8):487-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smyth F. Medical geography: therapeutic places, spaces and networks. Prog Hum Geogr. 2005;29(4):488-495. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mankekar P. “India shopping”: Indian grocery stores and transnational configurations of belonging. Ethnos. 2002;67(1):75-97. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dyck I, Dossa P. Place, health and home: gender and migration in the constitution of healthy space. Health Place. 2007;13(3):691-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):758-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Minkler M. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu Y, Li Z, Breitung W. The social networks of new-generation migrants in China’s urbanized villages: a case study of Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 2012;36:192-200. [Google Scholar]