Abstract

Biosynthesis of the dihydrogenated forms of ergot alkaloids is of interest because many of the ergot alkaloids used as pharmaceuticals may be derived from dihydrolysergic acid (DHLA) or its precursor dihydrolysergol. The maize (Zea mays) ergot pathogen Claviceps gigantea has been reported to produce dihydrolysergol, a hydroxylated derivative of the common ergot alkaloid festuclavine. We hypothesized expression of C. gigantea cloA in a festuclavine-accumulating mutant of the fungus Neosartorya fumigata would yield dihydrolysergol because the P450 monooxygenase CloA from other fungi performs similar oxidation reactions. We engineered such a strain, and high performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analyses demonstrated the modified strain produced DHLA, the fully oxidized product of dihydrolysergol. Accumulation of high concentrations of DHLA in field-collected C. gigantea sclerotia and discovery of a mutation in the gene lpsA, downstream from DHLA formation, supported our finding that DHLA rather than dihydrolysergol is the end product of the C. gigantea pathway.

Keywords: dihydrolysergic acid, dihydrolysergol, P450 monooxygenase, CloA, gene cluster

INTRODUCTION

Ergot alkaloids are a diverse collection of tryptophan-derived compounds produced by several different fungi.1–4 In some cases, they contaminate food or feed, but in other cases, they are valued for their clinical applications. Most ergot alkaloid-producing members of the Clavicipitaceae (order Hypocreales), such as the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea and several Epichloë species that grow as endophytic symbionts in grasses, produce ergot alkaloids via a pathway that proceeds through lysergic acid, 9 (Figure 1). Ergot alkaloids derived from 9 have had a significant effect on agriculture due to their accumulation in grain or forage crops. Two members of the Clavicipitaceae, C. africana and C. gigantea, are exceptional in that they produce dihydroergot alkaloids.5–7 Dihydroergot alkaloids differ from the more commonly encountered 9-derived ergot alkaloids in that their fourth-formed or D ring of the ergoline skeleton is fully reduced (Figure 1). Dihydroergot alkaloids generally are less toxic than lysergic acid derivatives and are the basis of many of the ergot alkaloid-derived pharmaceuticals such as nicergoline, cabergoline, and hydergine, which are used clinically to treat migraines, dementia, and hyperprolactinemia.8–11 A better understanding of dihydroergot alkaloids and their biosynthesis may be useful for the engineering of lead compounds for pharmaceutical development.

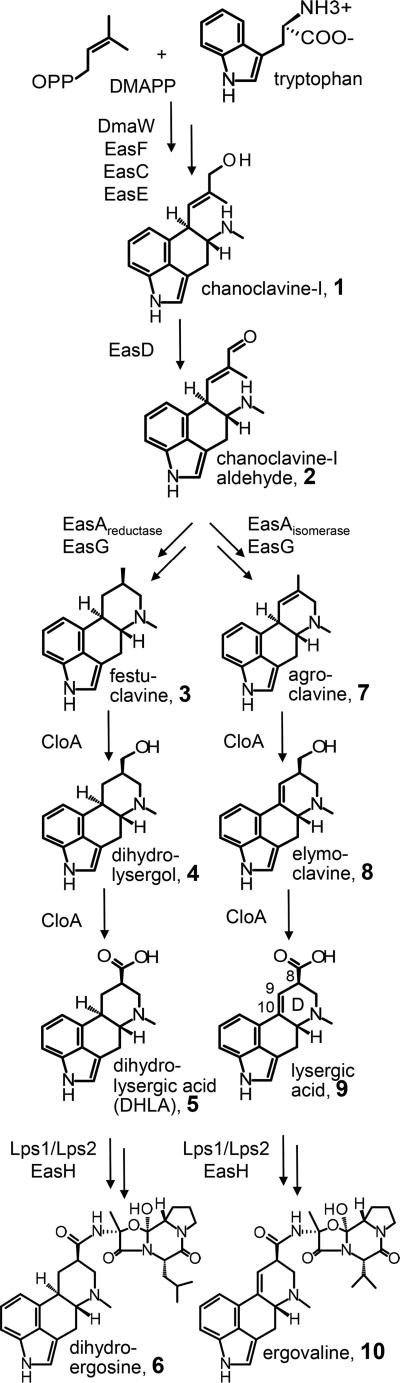

Figure 1.

Pathways to selected lysergic acid-derived ergot alkaloids and DHLA-derived ergot alkaloids. Enzymes responsible for catalysis are listed at appropriate points. Double arrows indicate omission of one or more intermediates. Relevant ring and carbon labeling (referred to in text) is indicated on the lysergic acid, 9, structure. Ergovaline, 10, is shown as a representative of several possible 9-derived ergopeptines; dihydroergosine, 6, is the only known dihydroergopeptine. Abbreviations: DMAPP, dimethylallylpyrophosphate; dma, dimethylallyl; eas, ergot alkaloid synthesis; clo, clavine oxidase; lps, lysergyl peptide synthetase.

The biosynthetic pathway to 9-derived ergot alkaloids has been studied intensively for the past two decades and has been reviewed recently.1–4,12,13 The elucidation of the pathway was greatly aided by the clustering of all genes involved in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis at a single chromosomal locus in each ergot alkaloid-producing fungus.12–15 The pathway to dihydroergot alkaloids diverges from the pathway to 9 at the step controlled by easA.16–19 Dihydroergot alkaloids are derived from festuclavine, 3, which has a fully saturated D ring, whereas 9-derived ergot alkaloids are built on agroclavine, 7, which contains a double bond between carbons customarily referred to as carbon 8 and carbon 9 (Figure 1). Different forms of the enzyme EasA are responsible for synthesizing 3 versus 7 from chanoclavine-I aldehyde, 2.16–18 After formation of 3 versus 7, the pathways appear to follow each other in parallel, with the next step catalyzed by the products of alternate alleles of cloA. For example, the version of CloA in the 9 producer Epichloe typhina × festucae recognizes 7 as substrate and oxidizes it to 920,21 but does not recognize 3 as substrate.21 In contrast, the dihydroergot alkaloid producer C. africana has a version of CloA that accepts 3 as substrate, oxidizing it to dihydrolysergic acid, 5 (DHLA).21 Most 9 producers incorporate 9 into ergopeptines or lysergic acid amides using a combination of the enzymes Lps1, Lps2, and EasH. In the 9 producer C. purpurea, the relevant downstream enzymes Lps2 and EasH accept dihydrogenated substrates as well as lysergic acid-based substrates.22,23 The substrate specificities of these enzymes in the dihydroergosine, 6, producer C. africana have not been studied.

C. gigantea, the ergot fungus of maize, appears to be geographically limited to high altitudes in Mexico.24,25 On the basis of very limited studies of its ergot alkaloid profile, the fungus is reported to be unique in ending its ergot alkaloid pathway at dihydrolysergol, 4, while also accumulating earlier pathway compounds including chanoclavine-I, 1, and 3.5,6 Labeling studies have demonstrated that 4 is a biosynthetic intermediate between 3 and 5.26 C. africana, a closely related fungus from sorghum, incorporates 5 into the dihydroergopeptine 6.7,26 The objective of this present study was to better understand the biosynthesis of the dihydrogenated ergot alkaloids of C. gigantea. One hypothesis to account for a pathway terminating at 4 in C. gigantea is that the version of CloA in this fungus performs only a two-electron oxidation of its substrate 3 to yield the primary alcohol form 4. We tested this hypothesis by expressing C. gigantea cloA in the 3-accumulating easM knockout strain of the fungus Neosartorya fumigata.27 The unexpected results of this experiment prompted a more detailed analysis of the ergot alkaloid biosynthetic capacity of C. gigantea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Transformation Constructs

Three different constructs were prepared over the course of this study to express C. gigantea cloA.28 Each construct was prepared by attaching a N. fumigata promoter and, in some cases, additional 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) to cloA coding sequences from C. gigantea by fusion PCR. The fusion PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes for which unique recognition sequences had been encoded in PCR primers. The restricted fragments were then cloned into pBCphleo (Fungal Genetics Stock Center, Manhattan, KS).29 All PCRs were performed with Phusion high-fidelity polymerase (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and followed a similar protocol with an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C (15 s), annealing at a temperature specific to each primer as indicated in Table 1 (15 s), extension at 72 °C (for the time interval specified for each reaction in Table 1), and a final extension at 72 °C for 60 s. PCRs were conducted in 25 µL containing 5 µL of 5× Thermo Phusion HF buffer (100 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1.5 mM MgCl2), dNTPs (final concentration 200 µM each), forward and reverse primers (final concentration 0.5 µM each), approximately 20–100 ng of template DNA, and 0.5 units of Phusion high-fidelity polymerase.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR Protocol Information

| primer pair |

primer sequencesa (5′ to 3′) | product (length in base pairs) | annealing temperature, extension time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAGTAGGCACTCCGCACCATGTCACTAACATCGTTTTACGCCC + CTACAAGCTTCGACTAGGCCACCCACACC | cloA with easA promoter extension (2491 bp) | 63 °C, 75 s |

| 2 | GACCTCTAGACATTGCTTCTAATCCACCAAGTACTTG + GGCGTAAAACGATGTTAGTGACATGGTGCGGAGTGCCTACTC | easA promoter with cloA extension (814 bp) | 64 °C, 30 s |

| 3 | GACCTCTAGACATTGCTTCTAATCCACCAAGTACTTG + CTACAAGCTTCGACTAGGCCACCCACACC | easA promoter-cloA fusion product (3253 bp) | 63 °C, 100 s |

| 4 | GAGTAGGCACTCCGCACCATGTCACTAACATCGTTTTACGCCC + CCGCCGATGTCATACTTCAACTAGTATGTGACTTCAGTCCATC | processed cloA with easA promoter and 3′ UTR extensions (1562 bp) | 63 °C, 40 s |

| 5 | GACTGAAGTCACATACTAGTTGAAGTATGACATCGGCG + CACAGAATTCGAACTTCTGTGACGTCGCCAGATTG | 3′ UTR with cloA extension (422 bp) | 63 °C, 20 s |

| 6 | GACCTCTAGACATTGCTTCTAATCCACCAAGTACTTG + CACAGAATTCGAACTTCTGTGACGTCGCCAGATTG | easA promoter-processed cloA-3′ UTR fusion product (2713 bp) | 64 °C, 90 s |

| 7 | GTACCAGACGAATCTACACAATGTCACTAACATCGTTTTACGCC + CCGCCGATGTCATACTTCAACTAGTATGTGACTTCAGTCCATC | processed cloA with gpdA promoter and 3′ UTR extensions (1564 bp) | 61 °C, 40 s |

| 8 | GATTCTAGAAGTCCTGAATAGTAG + GGCGTAAAACGATGTTAGTGACATTGTGTAGATTCGTCTGGTAC | gpdA promoter with cloA extension (990 bp) | 64 °C, 40 s |

| 9 | GATTCTAGAAGTCCTGAATAGTAG + CACAGAATTCGAACTTCTGTGACGTCGCCAGATTG | processed cloA with gpdA promoter and 3′ UTR fusion product (2889 bp) | 60 °C, 90 s |

| 10 | CTATAGAGTAGGCACTCCGCAC + CTACGCCGACTACTGTTGTCC | cloA cDNA (1524−1621 bp) | 58 °C, 45 s |

| 11 | CAGTTCGAGCACGTCTTCTCG + GTGCTCGACAATCATGAGGTC | lpsA near frame shift (743 bp) | 60 °C, 30 s |

Underlines indicate unique restriction sites used for cloning fusion PCR products: TCTAGA, XbaI; GAATTC, EcoRI; and AAGCTT, HindIII.

The first construct contained the coding sequences and 364 bp of 3′ UTR of cloA from C. gigantea under the control of the easA promoter from N. fumigata. The respective fragments were amplified individually and ultimately fused with primers (combinations 1, 2, and 3) and conditions as indicated in Table 1. The fusion PCR product was cloned as an XbaI/HindIII fragment into pBCphleo. The second construct contained a fully processed, intron-free version of cloA from C. gigantea fused to 399 bp of 3′ UTR sequences from C. gigantea cloA and under the control of the N. fumigata easA promoter. Primers for assembly of the construct, which was cloned into pBCphleo as an XbaI/EcoRI fragment, are provided in Table 1 (combinations 4, 5, and 6). The third construct contained the fully processed, intron-free version of cloA from C. gigantea fused to 399 bp of 3′ UTR sequences from C. gigantea cloA and under the control of the N. fumigata gpdA promoter, as assembled with primer pairs 7, 8, and 9 and conditions listed in Table 1. For the purposes of this experiment, the N. fumigata gpdA promoter was operationally defined as the 956 bp immediately upstream of N. fumigata gpdA.30

Modification of N. fumigata by Transformation

The recipient for all transformations was the festuclavine-accumulating N. fumigata easM knockout strain.27 Protoplasts were prepared and transformed as described previously.16,21,27 Transformants were screened for changes in ergot alkaloid profile by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection according to established methods31 that are described in more detail below. Transformed colonies selected for further study were purified to nuclear homogeneity by culturing from single conidia and checked for the presence of the introduced cloA construct by PCR with primer combination 1 (Table 1).

mRNA Analysis

Transformed fungal cultures were grown in 50 mL of malt extract broth (per liter: 6.0 g malt extract; 1.8 g maltose; 6.0 g dextrose; 1.2 g yeast extract) in a 250 mL flask for 1 d at 37 °C with shaking at 80 rpm. The resulting fungal mat was placed in an empty Petri dish and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 1 d. The RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to extract RNA from approximately 80 mg of fungal mat. Ten microliters DNaseI-treated RNA (of 40 µL recovered) was reverse transcribed with Superscript IV (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) in a 20 µL reaction. One microliter of the resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase and primer combination 10 (Table 1) in a 25 µL reaction. cDNA from bands representing different transcript lengths (1524 and 1621 bp) were excised, purified with Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), and sequenced by Sanger technology at Eurofins Genomics (Louisville, KY).

Analysis of CloA Substrate Specificity

Substrate 7 is oxidized to 9 by the versions of CloA found in Epichloë typhina × festucae isolate Lp120 and C. africana.21 The ability of CloA from C. gigantea to oxidize 7 was tested by feeding 7 to a C. gigantea cloA-transformed N. fumigata strain. Twelve cultures each of the C. gigantea cloA-transformed strain and N. fumigata easM knockout strain, as a negative control, were grown from 60 000 conidia in 200 µL of malt extract broth. Six cultures of each strain were supplemented with 2 µL of 7 (10 nmol/µL in methanol), whereas the other 6 cultures were supplemented with 2 µL of methanol as a control. Twelve noninoculated malt extract broth controls also were treated with the same supplements. The cultures were incubated for 7 d in a 37 °C incubator and pulverized with the addition of 300 µL HPLC-grade methanol and 10 glass beads (3 mm diameter) in a Fastprep 120 instrument (Bio101, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 s at 6 m/s. Methanol was selected as the extraction solvent for this experiment and for others in this study because of the relatively polar nature of the clavine analytes and DHLA. The extracted alkaloids were analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection (described below).

Characterization of the Ergot Alkaloid Synthesis (eas) Cluster of C. gigantea

The C. gigantea eas gene cluster (Figure 7)28 was characterized by finding additional eas genes neighboring cloA through blastx comparisons of serial, contiguous 5-kb fragments, sampled in both directions from cloA, to the nonredundant nucleotide database at blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. A portion of the pseudogene lpsA was further characterized by PCR amplification from C. gigantea genomic DNA samples with primer combination 11 (Table 1) and Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics).

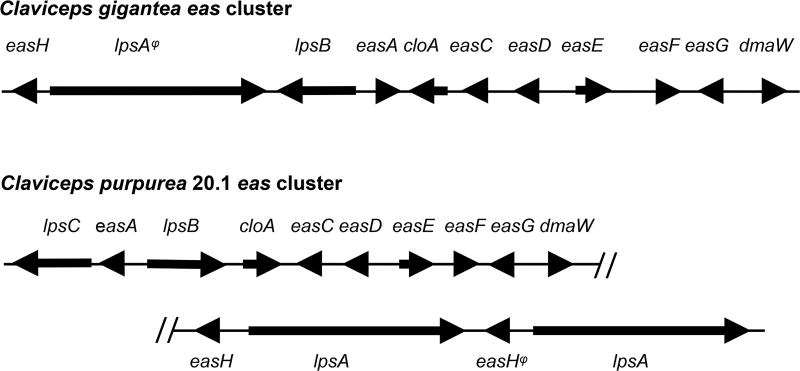

Figure 7.

Ergot alkaloid synthesis (eas) clusters from C. purpurea12,14 and C. gigantea.28 Abbreviations: dma, dimethylallyl; eas, ergot alkaloid synthesis; clo, clavine oxidase; lps, lysergyl peptide synthetase. The symbol Ψ indicates a pseudogene.

HPLC and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) Analyses

For HPLC with fluorescence detection, colonies of N. fumigata strains were grown on malt extract agar. Approximately 300 µL samples were obtained by removing a plug of culture with the wide end of a 1000-µL pipet tip, and alkaloids were extracted with 300 µL of HPLC-grade methanol. C. gigantea sclerotium samples from Calimaya, Mexico were generously donated by Dr. Carlos De Leon of Montecillo, Mexico. Samples of 100 mg from the head of each sclerotium were pulverized with 10 glass beads (3 mm diameter) in 1 mL of HPLC-grade methanol in a Fastprep 120 (Bio101, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 s at 6 m/s. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, particulates were pelleted by centrifugation.

Twenty microliters of extract was analyzed for ergot alkaloids by HPLC with fluorescence detection by methods described in detail previously.31 The column used was a 150 × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size, Prodigy C18 (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The mobile phase was a 55 min, binary, multilinear gradient of 5% acetonitrile to 75% acetonitrile in 50 mM aqueous ammonium acetate. Ergot alkaloids were detected with two serially connected fluorescence detectors, one set with excitation and emission wavelengths of 310 and 410 nm, respectively, and the other at 272 and 372 nm. Detection of fluorescence at these wavelengths was highly selective, minimizing interference in these otherwise minimally purified samples.

Reference standards for 4 and 7 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and 1 was obtained from Alfarma (Prague, Czech Republic). A standard for determining chromatographic retention of 5 was prepared by incubating 1 mg of ergoloid mesylate (Sigma) in 100 µL of 1.2 M NaOH at 75 °C for 6 h, succeeded by neutralization with 100 µL of 1.2 M HCl. The presence of a compound with a mass corresponding to the molecular formula of 5 (m/z 271.1441) was confirmed by high-resolution mass spectrometry.

Alkaloids were quantitated by comparing their peak areas to standard curves prepared from dihydroergocristine (Sigma) for alkaloids fluorescing at 272 and 372 nm and ergotamine (Sigma) for alkaloids fluorescing at 310 and 410 nm. Peak areas for diastereoisomers of ergotamine and other ergot alkaloids with a 9,10 double bind were combined for quantitative purposes. Descriptive statistics and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were calculated with JMP (SAS, Cary, NC).

For high-resolution, accurate-mass LC–MS analysis of N. fumigata strains, 7 day-old cultures grown on malt extract agar were washed with 4 mL of HPLC-grade methanol. Particulates were pelleted by centrifugation; supernatant was concentrated to 200 µL in a SpeedVac, and 2 µL were injected into an Acquity UHPLC (Waters Corp.; Milford, MA) coupled to a Q Exactive hybrid quadrupol-orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific; San Jose, CA). Separations were performed at 50 °C on a 150 × 4.6 mm i.d., 2.6 µm, Kinetex EVO C18 LC column (Phenomenex; Torrance, CA). Samples were loaded onto the column with solvent A (0.1% formic acid, 99.9% water) and were eluted with an increasing concentration of solvent B (0.1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 500 µL/min. The gradient program initiated at 2% solvent B and held at that level for 2 min before linearly ramping to 40% solvent B at 15 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode using a top 5 data dependent acquisition mode for MS/MS. Precursor data were collected at 70 000 resolution with a scan range of m/z 100 to 600, while MS/MS data were collected at 35 000 resolution with a precursor dependent scan range. Precursor ions selected for MS/MS were isolated with a window of m/z 2.0 and fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy of 40.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

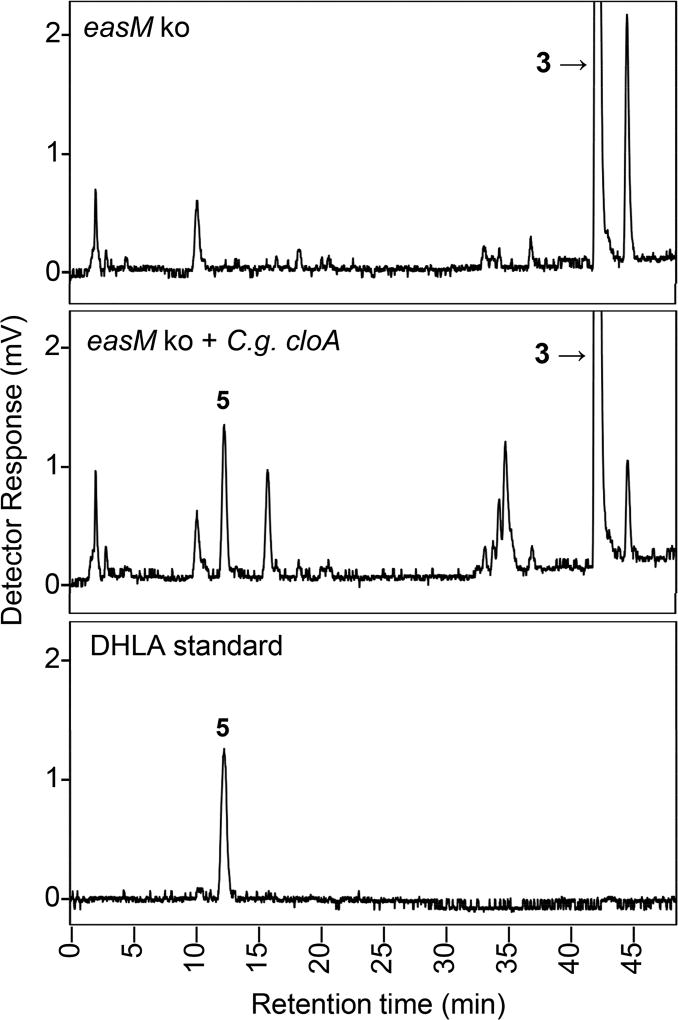

Function of C. gigantea CloA

A construct for expressing C. gigantea cloA was successfully transformed into the festuclavine-accumulating N. fumigata easM knockout strain. A total of 52 transformants was obtained from several transformation experiments, and 33 transformants produced a novel peak that shared its retention time with 5, as shown by HPLC with fluorescence detection (Figure 2). No peak with the retention time of 4 (31.1 min) was observed in extracts of any transformants. Relatively large quantities of 3 were still observed in the transformants expressing cloA and accumulating 5. A similarly low turnover of 3 to 5 was observed in recent experiments with the C. africana allele of cloA.21 Other novel peaks associated with expression of the C. gigantea allele of cloA eluted at approximately 16 and 34 min and did not correspond to any of our ergot alkaloid standards. Peaks with these same retention times were observed when the C. africana allele of cloA was expressed in the N. fumigata easM knockout.21 Extracts of the recipient strain, N. fumigata easM knockout, contained large quantities of 3 and nothing that eluted near 5 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of N. fumigata easM knockout strain and representative transformant expressing C. gigantea cloA. Ergot alkaloids were detected by fluorescence with excitation and emission wavelengths of 272 and 372 nm, respectively. Abbreviations: easM ko, easM knockout; Trp, tryptophan; C.g., Claviceps gigantea; 3, festuclavine; 5, dihydrolysergic acid.

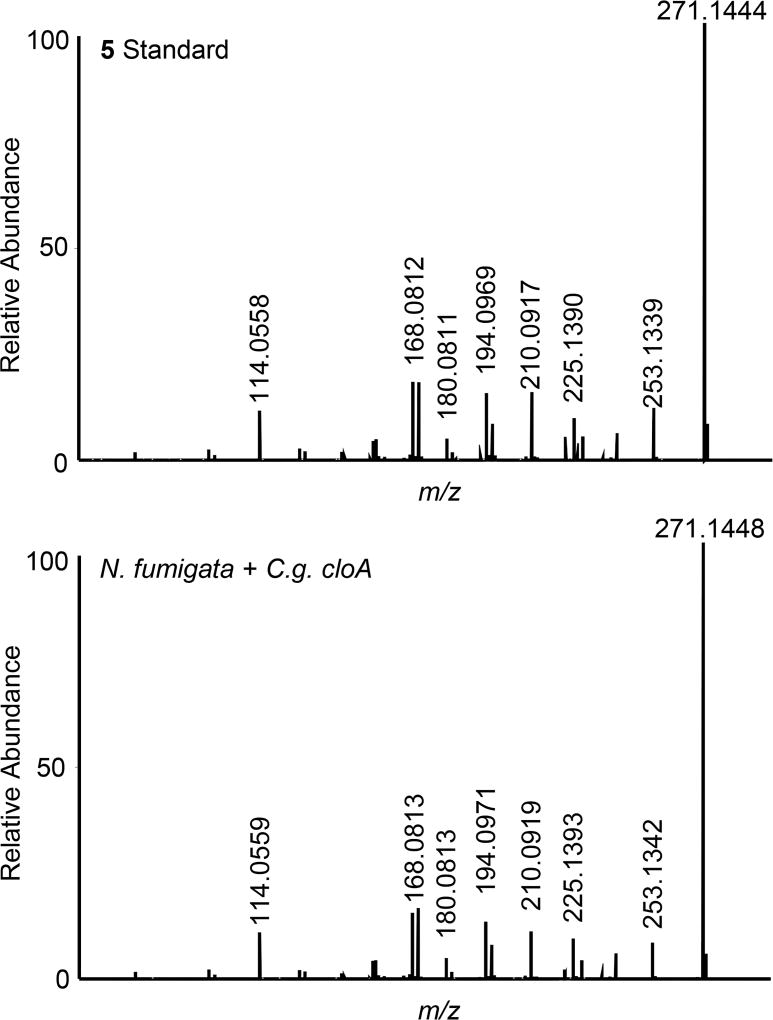

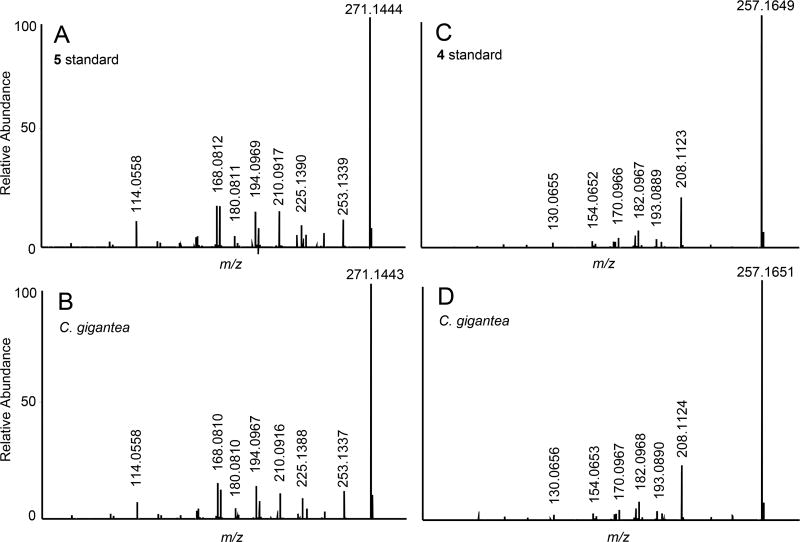

The accumulation of 5 in the transformants was supported by LC–MS analyses in which the cloA-transformed strains produced an analyte of m/z 271.1448 that had the same retention time as 5. The m/z value of this analyte is consistent with the [M + H]+ of 5 (calculated, 271.1441; observed, 271.1444), and the parent ion produced fragments similar in m/z to those obtained by fragmenting the 5 standard (Figure 3). The data indicate that C. gigantea CloA catalyzes a six-electron oxidation of 3 to 5 as opposed to stopping at 4 (Figure 1) as expected based on the reported ergot alkaloid profile of C. gigantea.6 Only trace quantities of 4 were detected by LC–MS analyses of the N. fumigata strain transformed with C. gigantea cloA, supporting the hypothesis of rapid turnover over of 4 intermediate to 5.

Figure 3.

Parent ions and fragments of 5 and analyte accumulating in N. fumigata easM knockout expressing C. gigantea cloA. Spectra were collected with electrospray ionization in positive mode. Abbreviations: easM ko, easM knockout; C.g., Claviceps gigantea.

The lack of significant accumulation of 4, the primary alcohol intermediate between 3 and 5, in the cloA-expressing strains is consistent with previous observations of N. fumigata strains expressing cloA from other sources. When N. fumigata was engineered to produce 9 from 7 by expressing the cloA allele of E. typhina × festucae, no elymoclavine, 8 (the analogous primary alcohol intermediate between 7 and 9), was detected, indicating that the enzyme bound substrate and did not release it until the substrate was fully oxidized.20 Similarly, when a synthetic version of C. africana cloA was expressed in N. fumigata easM knockout, 5 but not 4 was detected.21

The accumulation of 5 as opposed to 4 following expression of C. gigantea cloA in the 3-accumulating, easM knockout of N. fumigata showed that the allele of cloA from the isolate collected in Jajalpa, Mexico, encoded an enzyme capable of fully oxidizing 3 to 5. Turnover of 3 was low, as previously noted in studies in which cloA from C. africana was expressed in this same background.21 Possible reasons for low turnover include separate compartmentalization of expressed enzyme and endogenous substrate in N. fumigata, low expression of the introduced gene, and inherent properties of the expressed enzyme.

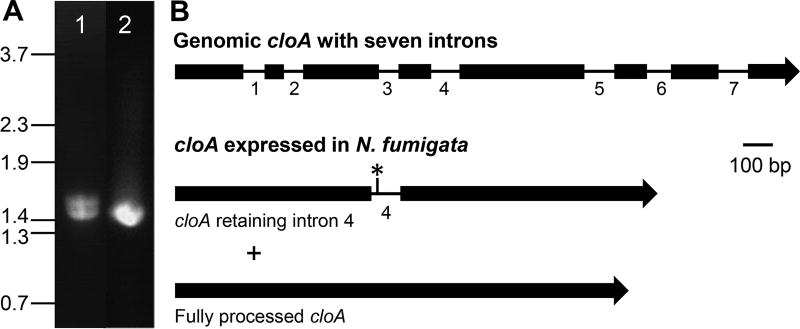

To check for expression of cloA and evaluate if the introns in cloA were being spliced correctly, mRNA was extracted from the transformants, reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and sequenced. Qualitative RT-PCR analysis and sequencing of cDNA prepared from mRNA of a cloA-transformed strain indicated that some of the mRNA was fully processed, whereas some was represented by a fragment that was larger than expected (Figure 4A). DNA sequence analysis demonstrated that the smaller fragment was free of introns, presumably providing it with the capacity to encode the enzyme that catalyzed the observed conversion of 3 to 5. The larger fragment retained one of the seven introns, specifically intron 4, resulting in a frame shift that led to a stretch of six amino acids read from an incorrect frame, followed by a premature termination codon (Figure 4B). Ultimately the product of the intron 4-containing transcript was truncated by 282 amino acids compared to the product of the fully processed allele. This truncation presumably rendered the resulting protein nonfunctional.

Figure 4.

Analysis of C. gigantea cloA mRNA expressed in N. fumigata easM knockout. (A) Qualitative reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of mRNA from genomic clone of C. gigantea cloA transformed into N. fumigata easM knockout (lane 1) or fully processed clone of C. gigantea cloA expressed in N. fumigata easM knockout (lane 2). Sizes of relevant fragments of BstEII-digested bacteriophage λ DNA are indicated to the left of the image. (B) Representations of structures of C. gigantea cloA genomic DNA and the two versions of cloA mRNA that accumulated upon expression of the genomic C. gigantea cloA in N. fumigata easM knockout.

It is interesting to note that N. fumigata was able to fully process some of the transcripts, whereas others retained intron 4. In previous work with the C. africana allele of cloA, no fully processed mRNA was observed when the genomic clone of cloA was expressed in the N. fumigata easM knockout.21 The most abundant transcript observed in that study contained two retained introns and a third misprocessed intron.

In an attempt to increase turnover of 3 to 5, modified versions of the cloA expression construct were prepared containing the fully processed cloA coding sequences derived from the cDNA. The fully processed version of cloA was expressed from the original N. fumigata easA promoter to test the effectiveness of removing the intron and also was expressed from a N. fumigata gpdA promoter to investigate whether a different promoter would increase the accumulation of DHLA. Neosartorya fumigata easM knockout transformants obtained with these constructs were analyzed by HPLC for accumulation of 5. The mean percent conversion yields of 3 to 5 for the fully processed cloA under the control of the easA promoter (2.1 ± 0.5%) or under the control of the gpdA promoter (1.9 ± 0.5%) compared to that obtained with the original C. gigantea cloA construct (1.6 ± 0.7%) were not significantly different (P = 0.86 in ANOVA).

Substrate Specificity of C. gigantea CloA

To test substrate specificity of C. gigantea CloA, six small-scale, liquid cultures of the N. fumigata easM knockout transformed with C. gigantea cloA were exogenously fed 20 nmol of 7, the precursor to 9.20 HPLC analysis showed the 7-fed transformants accumulated 9 (mean of 0.2 nmol ± 0.03 nmol per culture), whereas controls consisting of the easM knockout strain fed 7, or the C. gigantea cloA-transformed easM knockout fed the solvent methanol in place of 7, failed to produce any detectable 9. These data are consistent with those obtained with the C. africana allele of cloA in analogous studies21 and indicate that C. gigantea CloA can accept and fully oxidize 7 as well as 3 as substrate. Previous studies have shown that CloA from a producer of 9 (E. typhina × festucae) accepts 7 but not 3 as substrate.21

Phylogenetic data indicate that fungi that produce 9 are ancestral to those that produce 5,4 so the version of CloA observed in producers of 5 may have evolved to have a larger substrate binding pocket to accommodate the extra hydrogens associated with the saturated D ring of the substrate 3. Not enough is known about the structural motifs associated with substrate binding in CloA to assess this possibility critically.

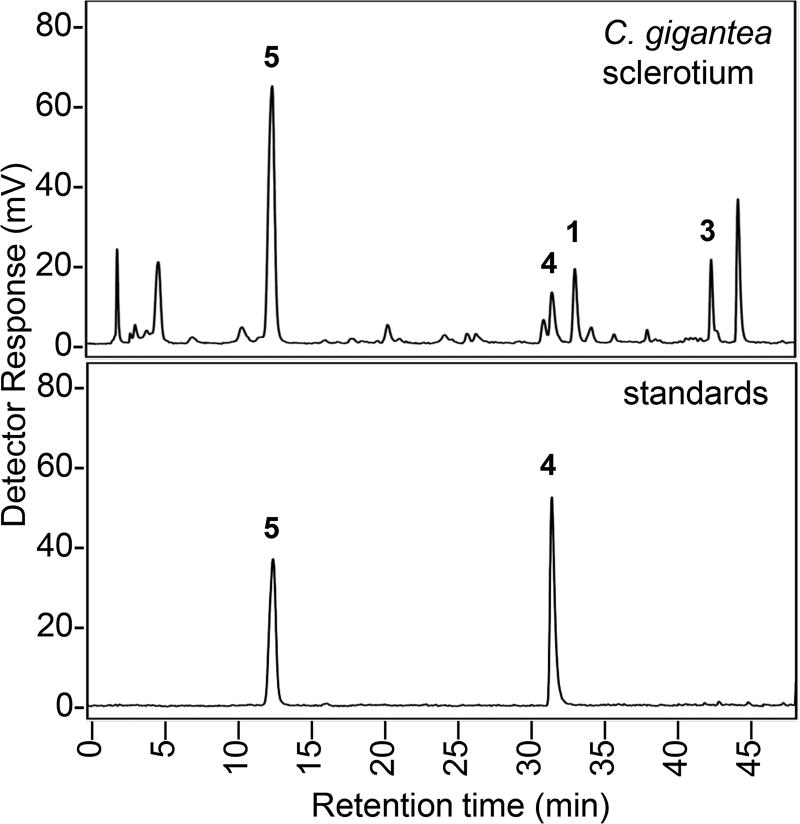

Analysis of the Ergot Alkaloid Profile of Field-Collected C. gigantea Sclerotia

Because C. gigantea CloA catalyzed the synthesis 5 as opposed to 4, we further investigated the ergot alkaloid biosynthetic capacity of C. gigantea by analyzing three field-collected C. gigantea sclerotia by HPLC and LC–MS. In HPLC analyses with fluorescence detection, each of the three sclerotia contained 1, 3, 4, and 5 (Figure 5; Table 2). This ergot alkaloid profile differed from the profile reported previously,5,6 which included 1, 3, and 4 but not 5. Small quantities of pyroclavine, a diastereoisomer of 3, also were detected in the previously published studies (Table 2).5,6 Pyroclavine may have been present in the sclerotia analyzed in this present study but could have gone unrecognized due to our lack of a reference standard.

Figure 5.

HPLC analysis of a C. gigantea sclerotium. Analytes were detected by fluorescence with excitation and emission wavelengths of 272 and 372 nm, respectively. Peaks corresponding to characterized ergot alkaloids are indicated: 1, chanoclavine-I; 3, festuclavine; 4, dihydrolysergol; 5, dihydrolysergic acid.

Table 2.

Ergot Alkaloids in Field-Collected Sclerotia of C. giganteaa

The presence of 5 in C. gigantea sclerotia was supported by high-resolution LC–MS analyses (Figure 6), which demonstrated the presence of an analyte with the same retention time as the standard and had a m/z of 271.1443, consistent the m/z values calculated (271.1441) and observed (271.1444) for 5. The analyte from the C. gigantea sclerotia fragmented similarly to the 5 standard (Figure 6). Similarly, the C. gigantea sclerotia contained an analyte that shared its retention time with standard for 4 and produced an ion of m/z 257.1651, consistent with the [M + H]+ for 4 (calculated, 257.1648; observed, 257.1649), and fragmented similarly to the standard for 4 (Figure 6). The presence of 1 and 3 also was supported by high-resolution LC–MS/MS analyses. Interestingly, trace concentrations of an analyte that produced a parent ion (m/z 269.1290) typical of 9 (calculated m/z 269.1285) also were detected in C. gigantea sclerotia, and the analyte produced fragment ions typical of those liberated from 9. The trace quantities of 9 detected in the C. gigantea sclerotia may result from the ability of C. gigantea CloA to oxidize 7 to 9, as detected in our substrate specificity studies. Agurell et al.5 reported 7 as a constituent of C. gigantea sclerotia they collected near Popocatepetl, Mexico. The presence of 7 in our sclerotium samples could not be unambiguously ascertained.

Figure 6.

High resolution LC–MS fragmentation spectra for (A) 5 standard and (B) coeluting analyte from C. gigantea sclerotia and (C) 4 standard and (D) coeluting analyte from C. gigantea sclerotia.

The difference in chemotype observed in this present study as compared to that observed in previous publications5,6 may be due to true isolate-level differences in chemotype or to differences in analytical technology and approaches. The sclerotia analyzed by Agurell et al.5,6 were collected near Popocatepetl, which is 75–100 km away from the origins of the isolates analyzed in the present study. The possibility that 5 was present in the Popocatepetl isolates but was not recognized cannot be excluded. Compound 5 was not known at that time, and a derivative of it was not isolated until several years after Agurell and colleagues published their work.7 It should be noted, however, that Agurell et al.5 looked specifically for 9 in their sclerotia and thus may have followed procedures that would have led them to 5 if it had been present. Compound 5 was the dominant ergot alkaloid in our sclerotium samples, with a concentration 7-fold greater than that of the second most abundant ergot alkaloid.

Characterization of C. gigantea eas Gene Cluster

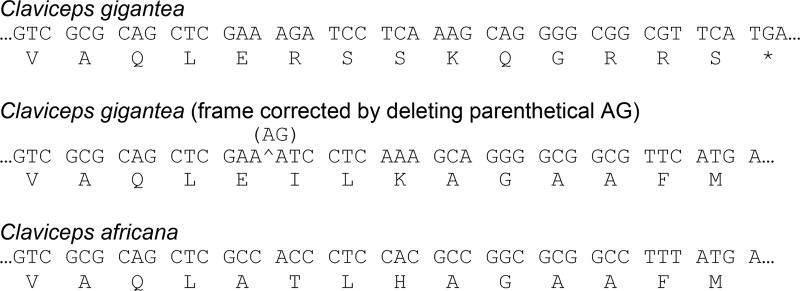

The eas gene cluster of C. gigantea28 was investigated to obtain additional evidence of the genetic capacity of this fungus to produce ergot alkaloids. The eas cluster contained homologues of the following genes: dmaW, easF, easC, easE, easD, easA, easG, cloA, lpsA, lpsB, and easH (Figures 1 and 7). The composition of the gene cluster, including genes downstream from cloA such as lpsA, lpsB, and easH, indicated the fungus was once capable of producing a dihydroergopeptine derivative of DHLA. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that CloA from C. gigantea fully oxidized carbon 17 of 3 to produce 5. The ability of C. gigantea to produce an alkaloid more complex than 5, however, appears to be prevented by a mutation in lpsA.

The gene lpsA encodes lysergyl peptide synthetase subunit 1, which acts downstream of CloA in the pathway as part of the enzyme complex that converts 5 into ergopeptines. The sequence of lpsA from C. gigantea contains a frameshift mutation, which almost certainly renders the product of the gene nonfunctional (Figure 8). This region of lpsA was resequenced by Sanger technology, and the mutation was confirmed. Comparison of nucleotide and amino acid sequences indicated the frameshift occurred between nucleotides 4345 and 4352 and appears to have resulted from the presence of two additional nucleotides in the C. gigantea coding sequence compared to that of lpsA from the close relative C. africana.32 The frame shift results in a premature termination codon appearing after amino acid 1458 of the projected 3581 amino acid length calculated for an in-frame translation product. Such a mutation is consistent with the observed accumulation of 5 as the pathway end product in C. gigantea sclerotia. Although Lps1 does not directly bind 5, it interacts with lysergyl peptide synthetase 2 (Lps2) which does bind 5, adenylates it, and binds it as a thioester for transfer to amino acids which are similarly adenylated and thioesterified by Lps1.22,33 Thus, without a functioning version of Lps1, 5 cannot be incorporated into more complex ergot alkaloids and becomes the de facto pathway end product. We hypothesize that if C. gigantea had a functional Lps1, it would produce a dihydroergopeptine such as 6, as observed by Mantle and Waight7 for the related fungus C. africana.

Figure 8.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences from the region immediately surrounding a frameshift mutation in C. gigantea lpsA.28 In the second sequence, nucleotides AG were deleted to restore the reading frame to align with that of the closely related fungus C. africana,32 which produces 6. These particular nucleotides were chosen to maximize amino acid sequence identity of the deduced products; removal of other combinations of two nucleotides also would restore the frame. Spaces were inserted between codons to improve clarity of presentation.

It should be noted that the C. gigantea DNA used in this present study was obtained from an isolate collected in Jajalpa, Mexico,34 which is approximately 77 km from Calimaya, Mexico, the origin of the three field-collected sclerotia that we analyzed by LC–MS. We sequenced the same region of lpsA from a Calimaya isolate and found the DNA sequence to be identical to that obtained from the Jajalpa isolate. The 4-containing isolates analyzed by Agurell et al.5,6 were collected near the Popocatepetl crater, approximately 105 km from Calimaya and 76 km from Jajalpa.

Agricultural and Translational Implications

The results of our genetic, biochemical, and chemical analyses demonstrate that some isolates of C. gigantea, the ergot pathogen of maize, have more extensive ergot alkaloid biosynthetic capacity than was previously determined. Isolates from two locations in Mexico were demonstrated to have an allele of cloA that encodes an enzyme capable of a six-electron oxidation of 3 to 5. C. gigantea is the first fungus known to produce 5 as its pathway end product. Whereas only trace quantities of 4 were detected in strains of N. fumigata expressing the C. gigantea allele of cloA, 4 represented about 10% of the ergot alkaloid detected in natural samples of C. gigantea sclerotia; the enzymatic origin of that 4 remains unknown. The sclerotia of C. gigantea assayed in this study also contained festuclavine and chanoclavine-I. Although toxicity of ergot alkaloids is most closely associated with those forms derived from 9, as opposed to the dihydrogenated forms found in C. gigantea, little is known about the potential toxicity of the dihydrogenated ergot alkaloids. Feed containing sorghum ergot (C. africana), which has a similar array of dihydrogenated ergot alkaloids as those found in C. gigantea but also accumulates the dihydroergopeptine 6, was refused by cattle and pigs35 and was associated with agalactia in dairy cattle35 as well as in pigs.36 The chemical composition of maize ergot is thus a relevant issue; that issue is compounded by the importance of maize as a food staple and as a component of animal feed as well as by the high incidence of the disease in areas close to Mexico City.37 C. gigantea also is a potential source of genes for synthetic biology approaches to synthesizing lead chemicals of pharmaceutical relevance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Tooley (USDA ARS) for the sample of C. gigantea genomic DNA from the isolate originating from Jajalpa, Mexico, and Carlos De León (Montecillo, Mexico) for the C. gigantea sclerotia from Calimaya, Mexico. The article was published with permission of the West Virginia Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station as scientific article number 3329.

Funding

This study was supported by Grant R15GM114774 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and by Hatch funds from United States Department of Agriculture.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

- Figure S1: Fragmentation of chanoclavine-I, 1, standard and analyte of similar m/z from C. gigantea sclerotium; Figure S2: Fragmentation of festuclavine, 3, derived from N. fumigata culture and analyte of similar m/z value from C. gigantea sclerotium; Figure S3: Fragmentation of analyte from C. gigantea sclerotium with parent ion mass and fragment ion masses similar to those observed previously for lysergic acid, 9, on similar instrumentation (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Gerhards N, Neubauer L, Tudzynski P, Li S-M. Biosynthetic pathways of ergot alkaloids. Toxins. 2014;6:3281–3295. doi: 10.3390/toxins6123281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young CA, Schardl CL, Panaccione DG, Florea S, Takach JE, Charlton ND, Moore N, Webb JS, Jaromczyk J. Genetics, genomics and evolution of ergot alkaloid diversity. Toxins. 2015;7:1273–1302. doi: 10.3390/toxins7041273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson SL, Panaccione DG. Diversification of ergot alkaloids in natural and modified fungi. Toxins. 2015;7:201–218. doi: 10.3390/toxins7010201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florea S, Panaccione DG, Schardl CL. Ergot alkaloids of the family Clavicipitaceae. Phytopathology. 2017;107:504–518. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-16-0435-RVW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agurell SL, Ramstad E, Ullstrup AJ. The alkaloids of maize ergot. Planta Med. 1963;11:392–398. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agurell S, Ramstad E. A new ergot alkaloid from Mexican maize ergot. Acta Pharm. Suecica. 1965;2:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantle PG, Waight ES. Dihydroergosine: a new naturally occurring alkaloid from the sclerotia of Sphacelia sorghi (McRae) Nature. 1968;218:581–582. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baskys A, Hou AC. Vascular dementia: pharmacological treatment approaches and perspectives. Clin. Interventions Aging. 2007;2:327–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winblad B, Jones RW, Wirth Y, Stoffler A, Mobius HJ. Memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Dementia Geriatr. Cognit. Disord. 2007;24:20–27. doi: 10.1159/000102568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr JL, Timpe EM, Petkewicz KA. Bromocriptine mesylate for glycemic management in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010;44:1777–1785. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morren JA, Galvez-Jimenez N. Where is dihydroergotamine mesylates in the changing landscape of migraine therapy? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010;11:3085–3093. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.533839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz N, Haarmann T, Pazoutova S, Jung M, Tudzynski P. The ergot alkaloid gene cluster: functional analyses and evolutionary aspects. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1822–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallwey C, Li S-M. Ergot alkaloids: structure diversity, biosynthetic gene clusters and functional proof of biosynthetic genes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:496–510. doi: 10.1039/c0np00060d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schardl CL, Young CA, Hesse U, Amyotte SG, Andreeva K, Calie PJ, Fleetwood DJ, Haws DC, Moore N, Oeser B, Panaccione DG, Schweri KK, Voisey CR, Farman ML, Jaromczyk JW, Roe BA, O’Sullivan DM, Scott B, Tudzynski P, An Z, Arnaoudova EG, Bullock CT, Charlton ND, Chen L, Cox M, Dinkins RD, Florea S, Glenn AE, Gordon A, Güldener U, Harris DR, Hollin W, Jaromczyk J, Johnson RD, Khan AK, Leistner E, Leuchtmann A, Li C, Liu JG, Liu J, Liu M, Mace W, Machado C, Nagabhyru P, Pan J, Schmid J, Sugawara K, Steiner U, Takach JE, Tanaka E, Webb JS, Wilson EV, Wiseman JL, Yoshida R, Zeng Z. Plant-symbiotic fungi as chemical engineers: multi-genome analysis of the Clavicipitaceae reveals dynamics of alkaloid loci. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schardl CL, Young CA, Pan J, Florea S, Takach JE, Panaccione DG, Farman ML, Webb JS, Jaromczyk J, Charlton ND, Nagabhyru P, Chen L, Shi C, Leuchtmann A. Currencies of mutualisms: sources of alkaloid genes in vertically transmitted epichloae. Toxins. 2013;5:1064–1088. doi: 10.3390/toxins5061064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyle CM, Cheng JZ, O’Connor SE, Panaccione DG. An old yellow enzyme gene controls the branch point between Aspergillus f umigatus and Claviceps purpurea ergot alkaloid pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:3898–3903. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02914-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng JZ, Coyle CM, Panaccione DG, O’Connor SE. A role for old yellow enzyme in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1776–1777. doi: 10.1021/ja910193p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng JZ, Coyle CM, Panaccione DG, O’Connor SE. Controlling a structural branch point in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12835–12837. doi: 10.1021/ja105785p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallwey C, Matuschek M, Li S-M. Ergot alkaloid biosynthesis in Aspergillus f umigatus: conversion of chanoclavine-I to chanoclavine-I aldehyde catalyzed by a short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase FgaDH. Arch. Microbiol. 2010;192:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00203-009-0536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson SL, Panaccione DG. Heterologous expression of lysergic acid and novel ergot alkaloids in Aspergillus f umigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:6465–6472. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02137-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold SL, Panaccione DG. Biosynthesis of the pharmaceutically important fungal ergot alkaloid dihydrolysergic acid requires a specialized allele of cloA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e00805–17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00805-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riederer B, Han M, Keller U. D-Lysergyl peptide synthetase from the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:27524–27530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havemann J, Vogel D, Loll B, Keller U. Cyclolization of Dlysergic acid alkaloid peptides. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuentes SF, Ullstrup A, Rodriguez A. Claviceps gigantea, a new pathogen of maize in Mexico. Phytopathology. 1964;54:379–381. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ullstrup AJ. Maize ergot: a disease with a restricted ecological niche. Trop. Pest Manage. 1973;19:389–391. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrow KD, Mantle PG, Quigley FR. Biosynthesis of dihydroergot alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:1557–1560. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilovol Y, Panaccione DG. Functional analysis of the gene controlling hydroxylation of festuclavine in the ergot alkaloid pathway of Neosartorya fumigata. Curr. Genet. 2016;62:853–860. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claviceps gigantea strain SP1 DmaW, EasG, EasF, EasE, EasD, EasC, CloA, EasA, Lps2, truncated Lps1, and EasH genes, complete cds. [accessed November 20, 2017]; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KY906251.

- 29.Silar P. Two new easy to use vectors for transformations. Fungal Genet. Rep. 1995;42:73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brock M, Jouvion G, Droin-Bergere S, Dussurget O, Nicola MA, Ibrahim-Granet O. Bioluminescent Aspergillus fumigatus, a new tool for drug efficiency testing and in vivo monitoring of invasive aspergillosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7023–7035. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panaccione DG, Ryan KL, Schardl CL, Florea S. Analysis and modification of ergot alkaloid profiles in fungi. Methods Enzymol. 2012;515:267–290. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394290-6.00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claviceps africana strain Cla9 alkaloid synthesis gene cluster, partial sequence. [accessed November 20, 2017]; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KY677717.

- 33.Correia T, Grammel N, Ortel I, Keller U, Tudzynski P. Molecular cloning and analysis of the ergopeptine assembly system in the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tooley PW, Bandyopadhyay R, Carras MM, Pazoutova S. Analysis of Claviceps africana and C. sorghi from India using AFLPs, EF-1α gene intron 4, and β-tubulin gene intron 3. Mycol. Res. 2006;110:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaney BJ, McKenzie RA, Walters JR, Taylor LF, Bewg WS, Ryley MJ, Maryam R. Sorghum ergot (Claviceps africana) associated with agalactia and feed refusal in pigs and dairy cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 2000;78:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb10535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kopinski JS, Blaney BJ, Murray SA, Downing JA. Effect of feeding sorghum ergot (Claviceps africana) to sows during midlacation on plasma prolactin and litter performance. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2008;92:554–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno-Manzano CE, De Leon-Garcia de Alba C, Nava-Diaz C, Sanchez-Pale R. Sclerotial germination and ascospore formation of Claviceps gigantea, Fuentes, De la Isla, Ullstrup and Rodriguez. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2016;34:223–241. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.