Abstract

The cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregation of TAR DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43) is a common histopathological hallmark of the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia disease spectrum (ALS/FTD). However, the composition of aggregates and their contribution to the disease process remain unknown. Here, we used proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) to interrogate the interactome of detergent-insoluble TDP-43 aggregates, and found them enriched for components of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) and nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery. Aggregated and disease-linked mutant TDP-43 triggered the sequestration and/or mislocalization of nucleoporins (Nups) and transport factors (TFs), and interfered with nuclear protein import and RNA export in mouse primary cortical neurons, human fibroblasts, and iPSC-derived neurons. Nuclear pore pathology is present in brain tissue from sporadic ALS cases (sALS) and those with genetic mutations in TARDBP (TDP-ALS) and C9orf72 (C9-ALS). Our data strongly implicate TDP-43-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport defects as a common disease mechanism in ALS/FTD.

Introduction

ALS and FTD are relentlessly progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorders that show a considerable overlap in genetics, clinical features, and neuropathology, suggesting that they are part of a disease spectrum1. A common histopathological hallmark in ALS/FTD patient brains is the cytoplasmic mislocalization of the predominately nuclear RNA-binding TDP-43 and the accumulation of its hyper-phosphorylated and ubiquitinated C-terminal fragment (CTF) in detergent-insoluble aggregates2,3. This pathology is observed in ~97% of ALS and ~50% of FTD cases, but also frequently present in other neurodegenerative diseases1. TDP-43 is encoded by the TARDBP gene and contains two RNA-recognition motifs, a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), and a nuclear export signal (NES), allowing it to shuttle between the nucleus and cytosol. The C-terminal glycine-rich region consists of a low-complexity domain with a prion-like Q/N-rich sequence, which mediates protein-protein interactions4. Remarkably, the C-terminus harbors most of the disease-causing missense mutations identified in ALS/FTD patients, which promote cytoplasmic mislocalization and neurotoxicity of TDP-435–7. Under environmental stress conditions, persistent stress granule formation in the cytosol may increase stability of TDP-43 and facilitate aggregation8. Although aberrant sequestration of RNA-binding proteins and other interacting proteins could lead to impaired RNA and protein homeostasis1, the exact molecular mechanism by which TDP-43 pathology (i.e. cytoplasmic aggregation or mutation of TDP-43) causes neurodegeneration remains poorly understood.

To explore the mechanisms through which TDP-43 pathology contributes to neurodegeneration, we adapted the BioID method to interrogate the proteome of detergent-insoluble cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates. Our proteomic analysis identified components of nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways as a major group of proteins present in the pathological TDP-43 aggregates. Morphological and functional analyses in primary cortical neurons, patient fibroblasts, and stem cell-derived neurons confirmed that TDP-43 pathology causes the mislocalization and/or aggregation of Nups and TFs, as well as disruption of nuclear membrane (NM) and NPCs, leading to reduced nuclear protein import and mRNA export. In addition, mutations in Nup genes act as genetic modifiers in Drosophila models of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Our findings of Nup205 pathology in the brain tissue of sALS and TDP-ALS point to nucleocytoplasmic transport defects caused by TDP-43 pathology as a common disease mechanism in ALS/FTD, and potentially other TDP-43 proteinopathies.

Results

Cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates are enriched for components of nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways

A 25kDa C-terminal fragment of TDP-43 (TDP-CTF) generated by proteolytic cleavage at Arg208 is found as a major component of insoluble cytoplasmic aggregates in ALS/FTD patient’s brain tissue3. Its expression as a fusion protein in vitro recapitulates histopathological features present in human patients9–11. To characterize changes in the interaction partners of TDP-43 under normal and pathological conditions, we used the BioID approach, which is based on the fusion of a promiscuous mutant of E. coli biotin ligase (BirA*) to proteins of interest and catalyzes the biotinylation of proximate proteins in the natural cellular environment12,13.

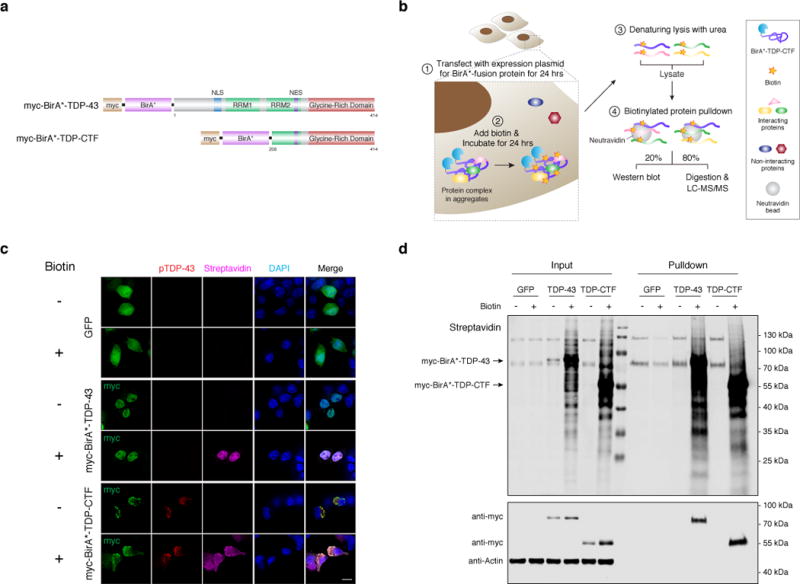

To determine physiological and aggregate-specific interacting partners of TDP-43, we transfected Neuro-2A (N2a) neuroblastoma cells with expression vectors for myc-BirA*-tagged human TDP-43 (myc-BirA*-TDP-43) or TDP-CTF (myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF) (Fig. 1a). Cells were incubated with excess biotin in the culture media to induce biotinylation of proximate proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), followed by denaturing lysis in 8M urea to solubilize protein aggregates, and affinity-purification via neutravidin beads (Fig. 1b). Biotinylated proteins co-localized with myc-BirA*-TDP-43 in the nucleus, and with myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF in cytoplasmic aggregates that were positive for hyper-phosphorylated TDP-43 (pTDP-43 Ser409/410), ubiquitin, and p62/SQSTM1 (Fig. 1c, and Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Proximity-dependent biotinylation of myc-BirA*-TDP-43 and myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF associated proteins showed distinct patterns in western blots (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. A modified BioID method identifies the composition of pathological detergent-insoluble TDP-43 aggregates.

a, Domain structures of myc-BirA* fusion constructs with human full-length TDP-43 and TDP-CTF protein. b, Schematic for the proximity-dependent biotinylation and identification of proteins associated with myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF. c, Anti-myc staining shows nuclear myc-BirA*-TDP-43 and cytoplasmic aggregates of myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF (green) that are positive for pTDP-43 (S409/410) (red) and biotin (magenta). d, Western blot analysis of biotinylated proteins in lysates and after pulldown with neutravidin beads. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Uncropped blots are provided in Supplementary Figure 17. Scale bar: 10 μm.

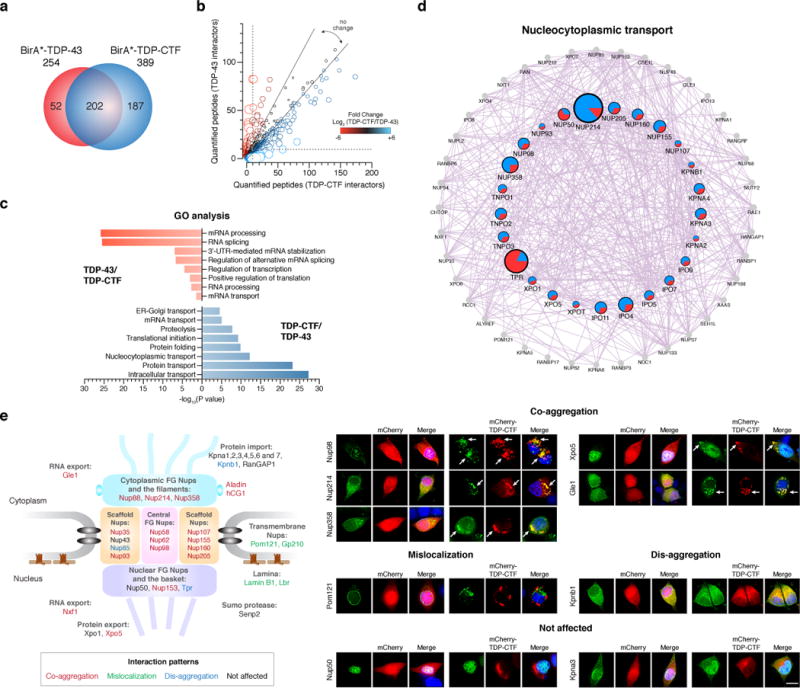

Affinity purified biotinylated proteins were subjected to unbiased proteomic analysis. We found 254 proteins associated with myc-BirA*-TDP-43, and 389 proteins with myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF (Fig. 2a). Clustering analysis of TDP-43 or TDP-CTF associated proteome versus mock transfected control based on gene ontology (GO) in DAVID identified distinct categories of strongest interacting proteins. The top categories in TDP-43/Mock were mRNA processing and splicing, whereas those in TDP-CTF/Mock were intracellular protein transport and translation initiation (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We further characterized the differences in the function-specific enrichment and interaction networks by comparing the TDP-CTF and TDP-43 associated proteome (Fig. 2b, c). Proteins involved in mRNA processing primarily associated with TDP-43 (Supplementary Fig. 2c), whereas the TDP-CTF associated proteome was enriched for proteins involved in intracellular transport (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Our network analysis also showed comparable results in biological processes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, we identified components of nucleocytoplasmic transport pathway as a major subset of protein interactors within TDP-CTF aggregates (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Pathological TDP-43 aggregates contain components of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery.

a, Mass spectrometry analysis of proximity-biotinylated proteins associated with BirA*-TDP-43 and BirA*-TDP-CTF. The 202 proteins present in both datasets accounted for 80% of the TDP-43 and 52% of the TDP-CTF associated proteome. b, Mapping the number of identified peptide spectra matches (PSMs) for the interacting protein of TDP-43 and TDP-CTF (circle). The relative abundance ratio (log2-fold change) between TDP-CTF and TDP-43 associated proteome is shown by circle size and color. Positive values indicate predominant association with TDP-CTF (blue), and negative values with TDP-43 (red). The dotted line indicates the cut-off threshold. c, Gene ontology (GO) analysis of proteins preferentially associated with TDP-43 or TDP-CTF. P-values indicate the probability of seeing a number of proteins annotated to a particular GO term, given the proportion of proteins in the total mouse proteome that are annotated to that GO Term. d, Network analysis of the TDP-CTF versus TDP-43 proteome in the nucleocytoplasmic transport pathway by GeneMANIA. Grey circles represent unidentified proteins. Colored circles represent the identified proteins and their PSMs in TDP-CTF (blue) and TDP-43 (red) associated proteome. Circle sizes reflect log2-fold change between TDP-CTF and TDP-43. e, Summary diagram of the TDP-CTF interaction screen with 37 proteins involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Representative images of the co-aggregation (arrows) of GFP-tagged proteins with mCherry-TDP-CTF in N2a cells. Images for all tested components of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery are shown in Supplementary Figure 4 and 5. Each experiment was repeated independently two to four times. Scale bar: 10 μm.

TDP-43 pathology causes the cytoplasmic aggregation and mislocalization of Nups and TFs

NPCs are multiprotein channels that act as gatekeepers regulating the receptor-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport of macromolecules. NPCs contain ~30 different Nups and are among the largest proteinaceous assemblies in the eukaryotic cell14. To confirm putative TDP-CTF-associated proteins detected in our proteomic screen, we co-expressed Nups or TFs together with TDP-CTF in N2a cells. We identified four different interaction patterns, as summarized in the schematic of the NPC (Fig. 2e, and Supplementary Fig. 4, 5): (1) Co-aggregation with TDP-CTF was predominantly found for phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeat-containing Nups, scaffold Nups and nuclear export factors; (2) Mislocalization but no co-aggregation was found in transmembrane Nups and nuclear lamina proteins, indicating a major structural disruption of the NPCs; (3) Nup85, Tpr and Kpnb1 caused dis-aggregation of TDP-CTF; (4) No or minor effect on the nuclear FG-Nups as well as nuclear import factors. A list of co-aggregation scores is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

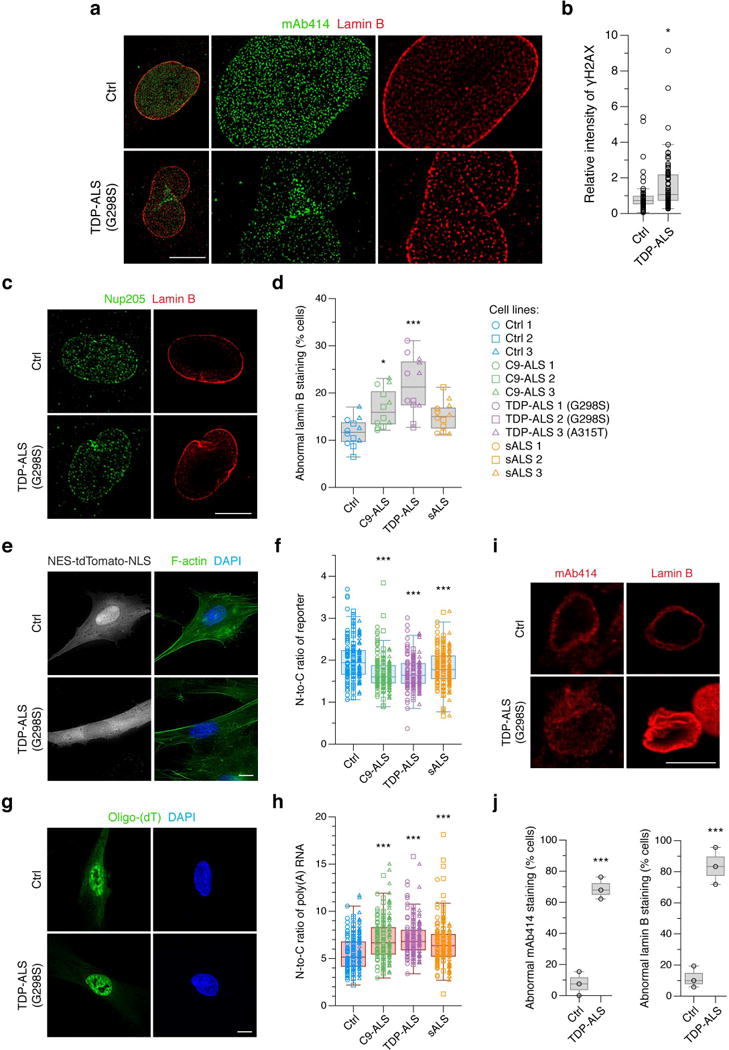

Figure 5. Human cells from ALS patients exhibit defects in NPC and nuclear lamina morphology and nucleocytoplasmic transport.

a, Super-resolution immunofluorescence (IF) imaging of endogenous FG-Nups (mAb414, green) and lamin B (red) in fibroblasts from healthy control (Ctrl) and TDP-ALS. This was repeated independently three times with similar results. Scale bar: 10 μm. b, IF and quantification of mean anti-γH2AX intensity. c, d, IF of endogenous Nup205 (green) and lamin B (red) (c) and quantification of cells with abnormal lamin B staining in fibroblasts from three Ctrl, C9-ALS, TDP-ALS and sALS cases (d). Scale bar: 10 μm. e, f, IF and quantification of N-to-C ratio of a transport reporter. Scale bar: 10 μm. g, h, IF and quantification of N-to-C ratio of poly(A) RNA. Scale bar: 10 μm. i, j, IF and quantification of cells with abnormal FG-Nups and lamin B staining in iPSC-derived motor neurons from Ctrl and TDP-ALS. Scale bar: 10 μm. Graphs represent quartiles (boxes) and range (whiskers). Five independent experiments for b (circles represent Ctrl: n = 51, TDP-ALS: n = 62; * P < 0.05, two-sided unpaired t-test), four independent experiments for d (symbols represent each independent experiment per cell line; * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), four independent experiments for f (symbols represent Ctrl: n = 178, C9-ALS: n = 175, TDP-ALS: n = 183, sALS: n = 180; *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), four independent experiments for h (symbols represent Ctrl: n = 186, C9-ALS: n = 180, TDP-ALS: n = 190, sALS: n = 181; *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) and triplicates for each group for j (symbols represent each independent experiment; *** P < 0.001, two-sided unpaired t-test). Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

ALS-linked missense mutations, such as Q331K and M337V, increase cytoplasmic TDP-43 mislocalization and neurotoxicity15. To test whether wild-type and mutant TDP-43 affect the localization of Nups and TFs, we co-expressed Nups or TFs together with TDP-43WT or TDP-43Q331K in N2a cells. Both TDP-43WT and TDP-43Q331K triggered the cytoplasmic aggregation of Nup62, whereas TDP-43Q331K increased the propensity for cytoplasmic mislocalization of Nup98 and cytoplasmic aggregates of Nup93, Nup107 and Nup214 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Our results show that TDP-CTF altered the cellular localization of nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins to varying degrees. Although mutant TDP-43 does not induce visible aggregates in this cell culture model, it can still compromise the localization of a subset of FG-Nups.

FG-Nups contain prion-like domains (PrLDs) that mediate the cytoplasmic co-aggregation with TDP-CTF

TDP-43 harbors a low-complexity domain and PrLD at the C-terminus, which contributes to self-assembly and protein-protein interactions8. PrLDs are frequently found in transcription factors and RNA-binding proteins16, but have been recently identified in the FG-rich domains of yeast Nups17. FG repeats are also present in mammalian Nups, and form amyloid-like interaction within sieve-like hydrogels and natively unfolded sites that act as effective barriers to normal macromolecules, but are permeable to shuttling nuclear transport receptor complexes18.

We used the PLAAC algorithm and other online tools (see Methods) to identify prion-like and low-complexity sequences in human Nups and TFs. Quantitative analysis revealed the presence of a PrLD and low-complexity domain in the hydrogel-forming Nup21419 and other FG-Nups including Nup54, Nup98, Nup153 and Nup358, but not Nup50 (Supplementary Fig. 7). To investigate whether PrLDs can mediate the co-aggregation with TDP-CTF, we generated and co-expressed the PrLD or non-PrLD fragment of Nup98, Nup153 and Nup214. We found that PrLDs of Nup98 and Nup214 were both required and sufficient to mediate cytoplasmic co-aggregation (Supplementary Fig. 8). Notably, although Nup153 PrLD had weak co-aggregation tendency with TDP-CTF, it caused dramatic mislocalization of both exogenous and endogenous full-length TDP-43.

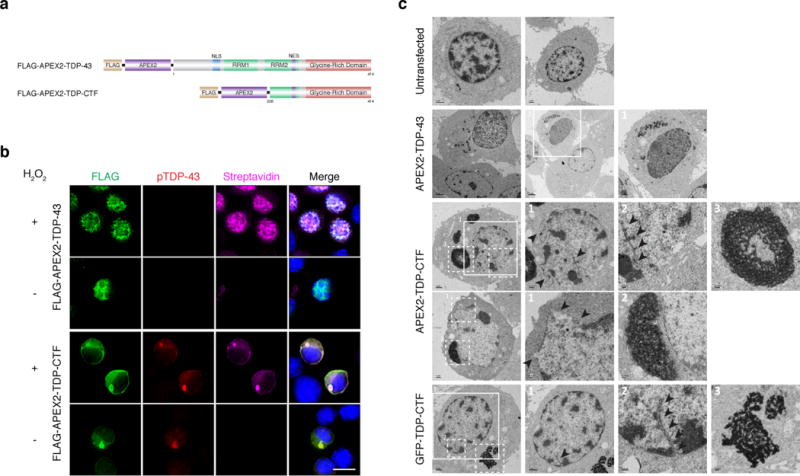

TDP-43 pathology disrupts the morphology of the NM and NPCs

To visualize the nuclear morphology of transfected cells at high resolution in electron microscopy (EM), we fused TDP-43 and TDP-CTF to the engineered peroxidase APEX2, which functions as an EM tag20 (Fig. 3a). APEX2-TDP-CTF formed pTDP-43-positive aggregates in the cytosol (Fig. 3b). Irregularly nuclear morphology with invaginated NMs was observed only in cells expressing APEX2-TDP-CTF or GFP-TDP-CTF (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Electron microscopy (EM) analysis reveals abnormal nuclear membrane (NM) morphology in N2a cells containing TDP-CTF aggregates.

a, Schematic domain structures of engineered peroxidase, APEX2, fusion TDP-43 and TDP-CTF. b, Nuclear signals of FLAG-APEX2-TDP-43 and cytoplasmic aggregates of FLAG-APEX2-TDP-CTF were detected by anti-FLAG antibody (green). TDP-CTF phosphorylation was detected by anti-pTDP-43 (S409/410) antibody (red). Protein biotinylation catalyzed by APEX2 was detected by cy5-conjugated streptavidin (magenta). Scale bar: 10 μm. c, EM analysis of untransfected N2a cells and cells expressing FLAG-APEX2-TDP-43, FLAG-APEX2-TDP-CTF or GFP-TDP-CTF. Untransfected cells showed dense chromatin and round-shaped nuclei. APEX2 catalyzed the deposition of diaminobenzidine (DAB) near nuclear APEX2-TDP-43 and in cytoplasmic APEX2-TDP-CTF aggregates. APEX2-TDP-CTF as well as GFP-TDP-CTF expressing cells exhibited irregularly shaped nuclei with deep invaginations of the NM. Each experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results.

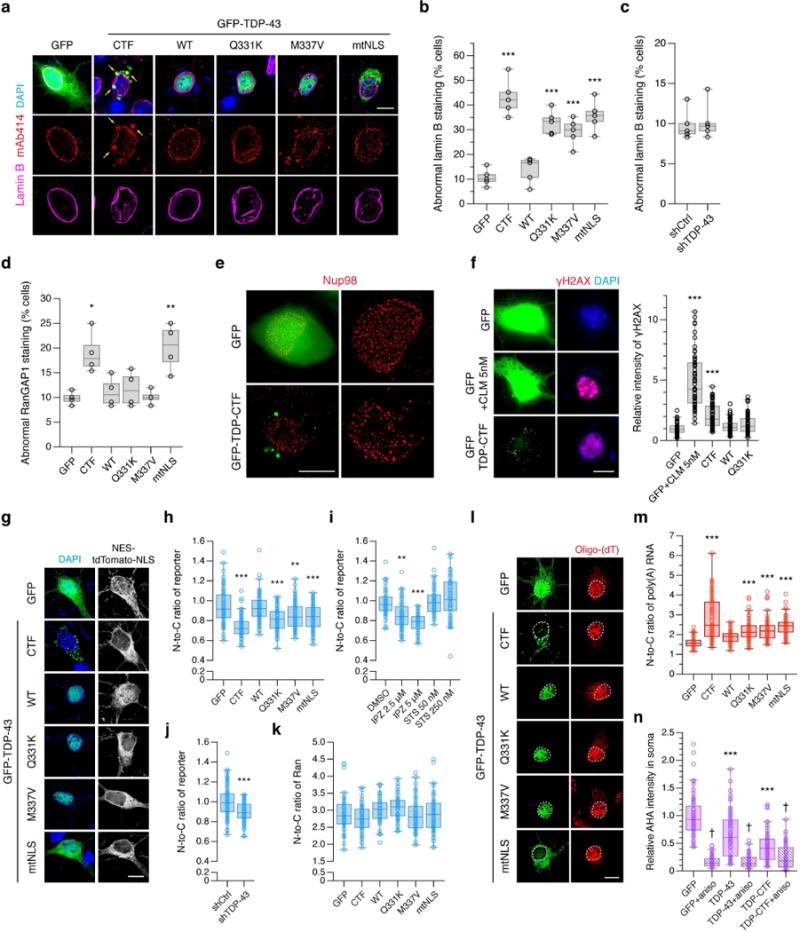

To further investigate morphological deficits in the NM and NPCs, we used fluorescence microscopy on mouse primary cortical neurons expressing GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-CTF, wild-type TDP-43 (TDP-43WT), ALS-linked mutants (TDP-43Q331K and TDP-43M337V), or an NLS mutant (TDP-43mtNLS). Aggregated and mutant TDP-43 caused cytoplasmic mislocalization and/or aggregation of endogenous FG-Nups concomitant with morphological abnormalities in the NM stained with anti-lamin B antibody (Fig. 4a). A total of 43% of TDP-CTF expressing cells and 29 to 36% of mutant TDP-43 expressing cells exhibited abnormal lamin B staining (Fig. 4b). 3D-reconstruction of nuclei stained with anti-lamin B antibody further confirmed the deep invaginations of the NM in the presence of TDP-CTF aggregates (Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Videos). Knockdown of TDP-43 did not cause obvious NM defects in our primary neuron model (Fig. 4c), whereas morphological nuclear defects were previously reported in the TDP-43-depleted HeLa cells21. While this could be caused by a very severe reduction (>90%) of this essential RNA-binding protein leading to increased apoptosis, a dual gain and loss-of-function mechanism leading to NM defects cannot be excluded. Abnormal RanGAP1 staining was only observed in the cells expressing TDP-CTF or TDP-43mtNLS (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Figure 4. TDP-43 pathology disrupts NPC and nuclear lamina morphology and nucleocytoplasmic transport.

a, Immunofluorescence (IF) of endogenous FG-Nups (mAb414, red) and lamin B (magenta) in primary cortical neurons expressing GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-CTF, TDP-43WT, TDP-43Q331K, TDP-43M337V or TDP-43mtNLS. This experiment was repeated independently five times. Scale bar: 10 μm. b, c, The percentage of transfected cells exhibiting abnormal lamin B staining (i.e. invagination, distortion) after transfection with TDP-43 expression vectors (b), or TDP-43 knockdown constructs (c). d, The percentage of transfected cells exhibiting abnormal RanGAP1 staining. e, Super-resolution IF imaging of endogenous Nup98 (red) in N2a cells expressing GFP or GFP-TDP-CTF. Scale bar: 10 μm. f, IF and quantification of mean γH2AX intensity in cortical neurons expressing GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-CTF, TDP-43WT or TDP-43Q331K. Calicheamicin (CLM) was added at 5 nM to induce DNA damage. Scale bar: 10 μm. g-i, IF and quantification of N-to-C ratio of a transport reporter encoding NES-tdTomato-NLS in cortical neurons expressing GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-43 constructs (g, h) or with treatment of staurosporine (STS) or importazole (IPZ) (i). This experiment was repeated independently three times. Scale bar: 10 μm. j, Quantification of N-to-C ratio of reporter in neurons with TDP-43 knockdown. k, Quantification of the N-to-C ratio of Ran in neurons expressing GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-43 constructs. l, m, IF and quantification of N-to-C ratio of poly(A) RNA. Poly(A) RNA was detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with oligo-(dT) probes (red). l, Quantification of levels of newly synthesized protein via metabolic labeling with azidohomoalanine (AHA). Anisomycin was added as a translation inhibitor. Scale bar: 10 μm. Graphs represent quartiles (boxes) and range (whiskers). Five independent experiments for b (circles represent each independent experiment; *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), five independent experiments for c (circles represent each independent experiment; two-sided unpaired t-test), four independent experiments for d (circles represent each independent experiment; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA), three independent experiments for f (circles represent GFP: n = 58, GFP+CLM 5 nM: n = 59, TDP-CTF: n = 61, TDP-43WT: n = 59 and TDP-43Q331K: n = 57; *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), three independent experiments for h (circles represent GFP: n = 70, TDP-CTF: n = 72, TDP-43WT: n = 70, TDP-43Q331K: n = 70, TDP-43M337V: n = 70, TDP-43mtNLS : n = 61; ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), three independent experiments for i (circles represent DMSO: n = 46, IPZ 2.5 μM: n = 45, IPZ 5 μM: n = 45, STS 50 nM: n = 46, STS 250 nM: n = 47; ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), four independent experiments for j (circles represent shCtrl: n = 77, shTDP-43: n = 80; *** P < 0.001, two-sided unpaired t-test), three independent experiments for k (circles represent GFP: n = 43, TDP-CTF: n = 44, TDP-43WT: n = 36, TDP-43Q331K: n = 51, TDP-43M337V: n = 46, TDP-43mtNLS : n = 48; one-way ANOVA), three independent experiments for m (circles represent GFP: n = 46, TDP-CTF: n = 61, TDP-43WT: n = 49, TDP-43Q331K: n = 51, TDP-43M337V: n = 60, TDP-43mtNLS : n = 58; *** P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), five independent experiments for n (circles represent GFP: n = 58, TDP-43WT: n = 58, TDP-CTF: n = 63, GFP+aniso: n = 59, TDP-43WT+aniso: n = 55, TDP-CTF+aniso: n = 53; *** P < 0.001, † P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

To clearly resolve the distribution of NPCs under normal and pathological conditions, we employed super-resolution structured-illumination microscopy (SIM). We found severely disturbed Nup98 distribution in the NM of N2a cells expressing GFP-TDP-CTF with signs of NPC clustering in some parts of the NM (Fig. 4e). These strong defects in the nuclear morphology and the localization of Nups and TFs caused by aggregated or mutant TDP-43 suggested a consequential effect on nucleocytoplasmic transport processes.

The nuclear lamina plays major roles in maintaining nuclear morphology, anchoring NPCs, organizing chromatin, and triggering DNA repair22. We found that the impaired lamina structure in TDP-CTF expressing neurons was associated with increased immunoreactivity of γH2AX, a marker for DNA double-strand breaks (Fig. 4f). There was a modest but significant difference between TDP-CTF and TDP-43WT (1.7-fold increase) or TDP-43Q331K (1.5-fold increase). Laminopathy-related DNA damage has also been observed in Alzheimer’s disease with tau pathology23, suggesting that lamin dysfunction may be frequently associated with neurodegeneration. To anchor the nuclear lamina to the inner NM, lamins are tethered to the cytoskeleton through the LInkers of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex24,25. We found that expression of TDP-CTF and TDP-43Q331K caused the mislocalization of the LINC proteins sun2 and nesprin-2 as well as a loss of F-actin integrity in cortical neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9c–f). These data suggest that TDP-43 pathology causes the disruption of the nuclear lamina by interfering with the structural support from LINC complex proteins and the peripheral cytoskeleton.

TDP-43 pathology disrupts nuclear import of proteins and export of mRNA

To examine nuclear protein import, we co-expressed GFP or GFP-TDP-43 with a fluorescent reporter protein flanked by NES and NLS sequences (NES-tdTomato-NLS) in primary cortical neurons. Quantitative analysis revealed a significant reduction of the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N-to-C) ratio of the reporter in cells expressing TDP-CTF or TDP-43 mutants compared to GFP control (Fig. 4g, h), indicating the cytoplasmic accumulation of reporter protein in the cells. Treatment with the nuclear import inhibitor, importazole (IPZ), reduced the N-to-C ratio of the reporter to a similar degree, whereas staurosporine (STS)-induced apoptosis did not, thus ruling out that the observed protein import defects were caused by cell death (Fig. 4i). We also found that shRNA-mediated reduction of TDP-43 levels lowered the N-to-C ratio of reporter (Fig. 4j). However, the N-to-C ratio of Ran was not obviously affected by TDP-43 (Fig. 4k). Compared to TDP-43WT, a significant reduction of the N-to-C ratio of TDP-43, and increases in cytoplasmic TDP-43 levels for TDP-43M337V and TDP-43mtNLS (TDP-43M337V/TDP-43WT: 1.3-fold, TDP-43mtNLS/TDP-43WT: 4.3-fold) were also observed (Supplementary Fig. 10a–c). The moderate but significant correlation of the N-to-C ratio of reporter to the N-to-C ratio of TDP-43 and the cytoplasmic TDP-43 levels (Supplementary Fig. 10d–f) suggest that subcellular TDP-43 levels need to be tightly regulated, and that a relative increase in cytoplasmic TDP-43 levels may compromise nuclear protein import. To investigate whether TDP-43 pathology affects nuclear RNA export, poly(A) RNA levels in both nucleus and cytoplasm were quantified. Expression of TDP-CTF and TDP-43 mutants caused nuclear retention of poly(A) RNA, indicating impaired nuclear RNA export (Fig. 4l, m and Supplementary Fig. 10g). As a likely consequence of this defect, we observed a significant reduction of steady state levels of protein translation in cells expressing TDP-43WT or TDP-CTF, as measured by metabolic labeling of newly synthesized proteins (Fig. 4n).

We next assessed the effect of TDP-43 pathology at the endogenous levels in human fibroblasts from three sALS, TDP-ALS, C9-ALS and healthy control cases. Super-resolution imaging revealed evenly distributed FG-Nups and round-shaped lamin B staining in controls, while clustered FG-Nups and irregular and fragmented lamin B staining was present in TDP-ALS (Fig. 5a). γH2AX immunoreactivity increased by 1.6-fold in TDP-ALS compared to control (Fig. 5b). The distribution pattern of Nup205 was altered in C9-ALS and TDP-ALS fibroblasts, which exhibited significantly increased abnormal lamin B staining (17% and 22%), whereas sALS cells showed a trend for increase (Fig. 5c, d). Quantitative analysis further showed a significant reduction of the N-to-C ratio of reporter (Fig. 5e, f) and nuclear retention of poly(A) RNA (Fig. 5g, h) in ALS cases. iPSC-derived motor neurons from healthy control and TDP-ALS showed significant increases in the percentage of TDP-ALS cells with mislocalized FG-Nups and distorted lamin B with increased immunoreactivity (Fig. 5i, j). These data suggest that the defects in the nucleocytoplasmic transport pathway are consistently observed in cortical neurons with ectopic expression of aggregated or mutant TDP-43, in fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neurons from ALS cases, as well as in a mechanistic ALS mouse model26. The dysregulation of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and disruption of the NM and NPCs may be a common mechanism in both sALS and fALS exhibiting TDP-43 proteinopathy.

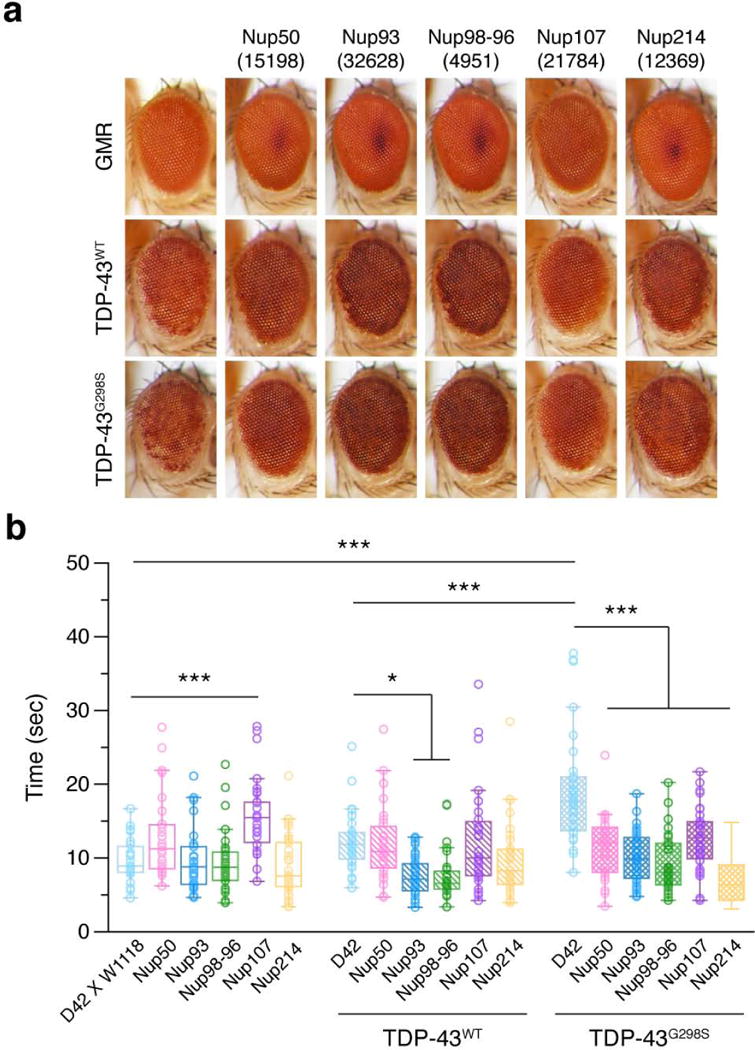

Mutations in several Nup genes act as suppressors of TDP-43 toxicity in Drosophila models of ALS

To identify genetic interactions between TDP-43 toxicity and Nup function in vivo, we tested whether mutations in Nup genes could alter TDP-43 toxicity in Drosophila disease models for ALS. Interestingly, expression of mutant TDP-43 in Drosophila motor neurons caused abnormal nuclear morphology27, similar to that found in spinal motor neurons of ALS patients28. Overexpression of human TDP-43WT or TDP-43G298S led to retinal degeneration and larval motor dysfunction (Fig. 6a, b). In addition to a Nup50 mutation previously implicated as a genetic suppressor of TDP-43 toxicity29, we identified several loss-of-function mutations in Nup genes that suppressed TDP-43-mediated eye phenotypes, including Nup93, Nup98-96, Nup107 and Nup214 (Fig. 6a). In larval turning assays, these mutations also rescued the locomotor dysfunction caused by TDP-43WT or TDP-43G298S expression in motor neurons (Fig. 6b). The results show that at least some aspects of TDP-43 toxicity in vivo depend on the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery.

Figure 6. Identification of genetic suppression of TDP-43 toxicity in Drosophila disease models of ALS.

a, b, Overexpression of human TDP-43WT and TDP-43G298S in Drosophila leads to neurodegeneration in the adult retina (a) and impairment in larval locomotor function (b). GMR GAL4 and D42 GAL4 driver lines were used for expression in the retina and motor neurons, respectively. W1118 was used as a control fly line. Loss-of-function mutations in several Drosophila Nup genes rescue the phenotypes caused by TDP-43 pathology. Graph represents quartiles (boxes) and range (whiskers) of b (dots represent D42 × w1118: n = 26, others: n = 30 animals; * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA), Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

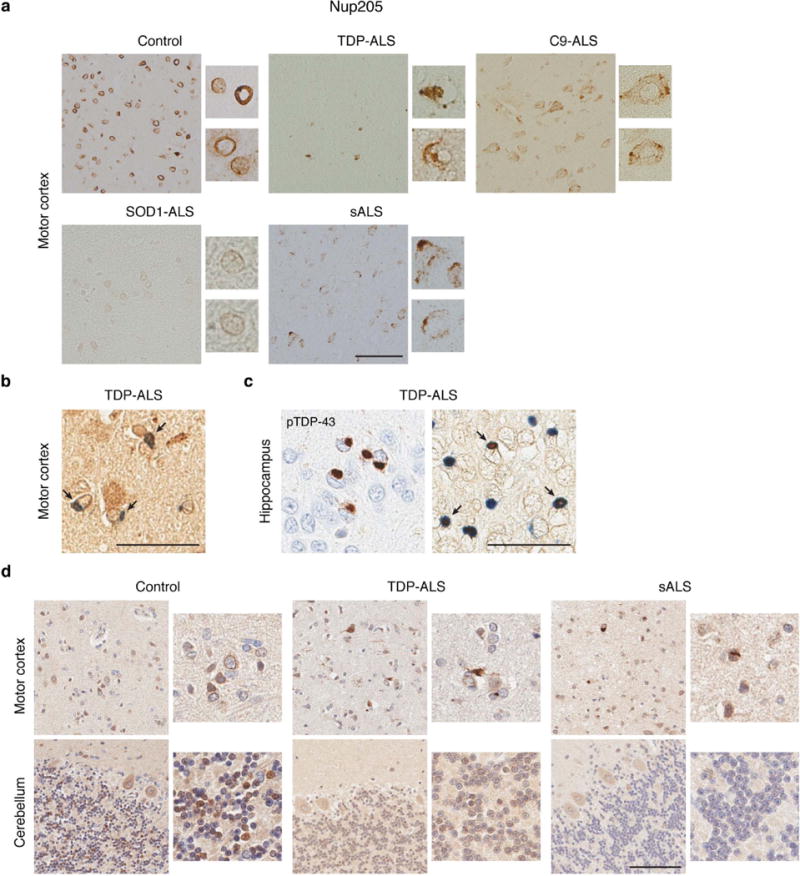

Nuclear pore pathology is common in ALS patient brain tissue with TDP-43 proteinopathy

We next investigated the presence of nuclear pore pathology in patient’s brain tissue with pTDP-43-positive inclusions, including sALS, TDP-ALS and C9-ALS cases (Supplementary Fig. 11a and Supplementary Table 2). To investigate the connection between TDP-43 and Nup pathology, we also stained the motor cortex from one SOD1 case (SOD1-ALS) and cerebellum from TDP-ALS and sALS cases, which acted as pTDP-43-negative controls (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Indeed, in the motor cortex, TDP-ALS and sALS cases but not age-matched controls presented with a widespread loss of Nup205 immunoreactivity and large Nup205-positive cytoplasmic inclusions, whereas neurons in C9-ALS cases exhibited abnormal perinuclear punctate staining (Fig. 7a). We found co-localization of Nup205 with pTDP-43-posive-inclusions in the motor cortex and more frequently in the hippocampus of TDP-ALS, suggesting partial co-aggregation (Fig. 7b, c). Cytoplasmic Nup205-positive inclusions were also observed in the frontal cortex of ALS cases (Supplementary Fig. 12). However, neither the SOD1-ALS motor cortex nor any cerebellum exhibited Nup205 pathology (Fig. 7a, d). Notably, one of our TDP-ALS cases showed no pTDP-43-positive inclusions in the motor cortex30 and was also devoid of Nup205 pathology. Abnormal NM morphology was occasionally present in the motor cortex of TDP-ALS but scarcely found in C9-ALS and sALS cases (Supplementary Fig. 13). However, we did not observe obvious defects in RanGAP1 staining among our cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 14). These data show that nuclear pore pathology may be a histopathological hallmark of fALS and sALS cases exhibiting TDP-43 proteinopathy, even in the absence of C9orf72 repeat expansion.

Figure 7. Nuclear pore pathology is present in brain tissue of fALS and sALS cases with pTDP-43-positive inclusions.

a, Immunohistochemical staining of Nup205 in human motor cortex was done once on five control, ten sALS, seven C9-ALS, and the SOD1-ALS and TDP-ALS cases, with similar results within groups. Scale bar: 100 μm. b, Double staining of pTDP-43 (blue) and Nup205 (brown) in motor cortex of TDP-ALS. Arrow indicates co-localization. Scale bar: 50 μm. c, pTDP-43 (left), and double staining of pTDP-43 (blue) and Nup205 (brown) (right) in hippocampus of TDP-ALS. Arrow indicates co-localization. Scale bar: 50 μm. d, Immunohistochemical staining of Nup205 in motor cortex and cerebellum was done once on five control, five sALS, and the TDP-ALS cases, with similar results within groups. Scale bar: 100 μm.

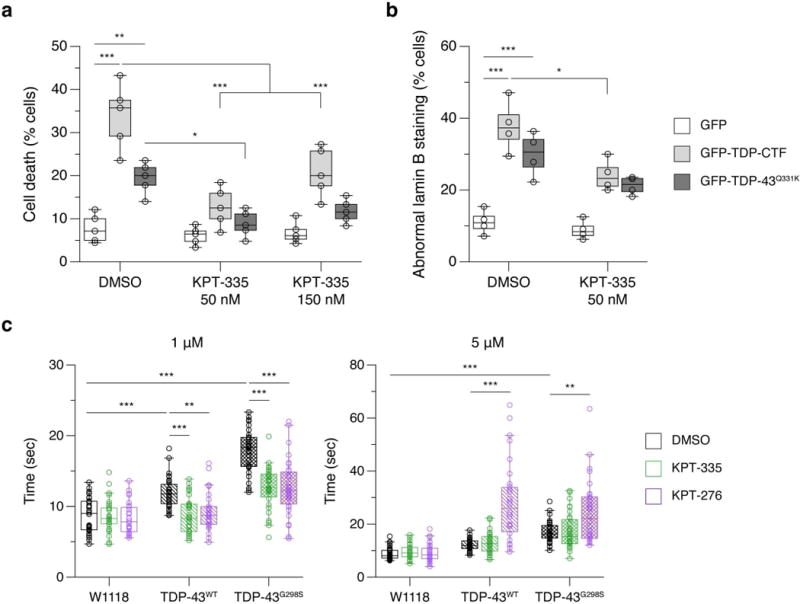

Suppression of TDP-43 toxicity rescues nucleocytoplasmic transport defects in vitro and in vivo

To assess pharmacological rescue of nucleocytoplasmic transport defects in TDP-43 pathology, we used a selective inhibitor, KPT-335 (Verdinexor), which interferes with Xpo1/Crm1-dependent nuclear export pathway. KPT-335 was reported to inhibit influenza virus31 and TNF-α neurotoxicity32. The related compound, KPT-276, has previously shown its neuroprotective role in C9-ALS33, and KPT-350 in Huntington’s disease34. We have previously shown that aggregated and mutant TDP-43 increased neurotoxicity in primary cortical neurons10. Treatment of 50 nM KPT-335 significantly suppressed 55 to 62% of cell death caused by TDP-CTF or TDP-43Q331K in cortical neurons, whereas 150 nM KPT-335 exhibited a trend for increased toxicity (Fig. 8a). The defects in nuclear morphology caused by TDP-CTF were also recused by the treatment of 50 nM KPT-335 (Fig. 8b). Larval locomotor defects caused by human TDP-43WT or TDP-43G298S were also ameliorated by the treatment of 1 μM but not 5 μM of KPT-276 or KPT-335 (Fig. 8c).

Figure 8. Pharmacological inhibition of TDP-43 toxicity rescues nucleocytoplasmic transport function caused by TDP-43 pathology.

a, Overexpression of TDP-CTF or mutant TDP-43Q331K increases cell death in transfected cortical neurons compared to GFP. Treatment of 50 nM KPT-335 for 24 hours reduced cell death in both TDP-CTF and TDP-43 Q331K. b, Abnormal nuclear morphology with lamin B staining in neurons expressing TDP-CTF or TDP-43Q331K is rescued via the treatment of 50 nM KPT-335. c, Locomotion defects in larva expressing human TDP-43WT and TDP-43G298S is ameliorated by treatment with 1 μM but not 5 μM PT-335 or KPT-276. Graphs represent quartiles (boxes) and range (whiskers). Five independent experiments for a (circles represent each independent experiment; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA), four independent experiments for b (circles represent each independent experiment; * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA) and c (circles represent n = 30 animals; ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Full statistical details are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Previously, we had identified poly(A)-binding protein nuclear 1 (PABPN1) as a potent suppressor of TDP-43 toxicity and aggregation that acts via a proteasome-dependent mechanism10. To assess its ability to rescue nucleocytoplasmic transport defects, we co-expressed TDP-CTF with PABPN1 in cortical neurons. PABPN1 overexpression not only led to the clearance of soluble and insoluble TDP-CTF (Supplementary Fig. 15a), but also restored the proper localization of endogenous FG-Nups and lamin B (Supplementary Fig. 15b, c). TDP-CTF-mediated defects in nuclear protein import (Supplementary Fig. 15d) and mRNA export (Supplementary Fig. 15e) were also rescued. These results suggest that suppression of TDP-43 toxicity via pharmacological or molecular inhibition may be a valid strategy to rescue the defective nucleocytoplasmic transport function.

Discussion

Here we have established a modified BioID procedure as a novel method to interrogate the proteome of insoluble aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Our study provides evidence that (1) proteins involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport are major components of pathological TDP-43 aggregates; (2) aggregated and mutant TDP-43 cause cytoplasmic mislocalization and/or aggregation of Nups and TFs; (3) PrLDs present in human Nups containing FG repeats are required and sufficient for co-aggregation; (4) aggregated and mutant TDP-43 trigger morphological defects in the NM and NPCs, as well as functional defects in nuclear protein import and mRNA export; (5) several Nup genes act as genetic modifiers of TDP-43 toxicity in Drosophila; (6) pharmacological and molecular inhibition of TDP-43 toxicity rescue nucleocytoplasmic transport defects and (7) nuclear pore pathology is present in motor and frontal cortex of sALS and fALS cases with pTDP-43-positive inclusions, suggesting that defective nucleocytoplasmic transport represents a common neuropathological hallmark in ALS cases and potentially other TDP-43 proteinopathies.

The specific composition of TDP-43 aggregates has remained unknown, perhaps due to technical limitations in preserving protein interactions under the harsh lysis conditions required for the extraction of insoluble aggregates. To address this open question, we adapted a method for proximity-based biotinylation of proteins for the characterization of pathological aggregates12,13. The high affinity of streptavidin/neutravidin to biotin allowed us to perform purification of biotinylated proteins under the strong denaturing condition required for solubilizing protein aggregates. Robust labeling of proteins within detergent-insoluble aggregates suggests that this method has a broad applicability to study a wide range of neuropathological inclusions. Our proteomic analysis of pathological TDP-43 aggregates led to the unexpected discovery that cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates are highly enriched for components of NPCs as well as TFs. Our findings implicate that TDP-43 may not only be mislocalized as a consequence of defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport, but also directly inhibit the nuclear import and export of macromolecules by sequestering components in this pathway. In addition, proteins involved in vesicular trafficking between ER and Golgi were also enriched in the TDP-CTF interactome (Supplementary Fig. 2). Of note, ER-Golgi transport dysfunction was found associated with various ALS mutations35. TDP-43 mutation had also been reported to compromise axonal mRNA transport in human motor neurons36, suggesting that deficits in multiple intracellular trafficking could be linked to the pathogenesis of ALS/FTD.

Although pathogenic mechanisms related to Nups have been widely studied in a variety of diseases37, little is known about their role in neurodegeneration. The first evidence related to ALS addressed a loss of Kpnb1 immunoreactivity and ruffled nuclear morphology stained with Nup62 and Nup153 antibodies in spinal motor neurons of sALS cases28. Mutations in the Gle1 gene, encoding an essential RNA export factor, were found associated with ALS and caused a deficit in motor neuron development in zebrafish via its loss-of-function38. Notably, several recent studies have linked ALS/FTD caused by an intronic G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in the C9orf72 locus to nucleocytoplasmic transport defects. Expression of 30 G4C2 repeats resulted in retinal degeneration in a Drosophila model for C9-ALS. One of the proposed mechanisms was the sequestration of RanGAP1 into G4C2 RNA foci, which interfered with Ran-dependent nucleocytoplasmic transport33. Additionally, unbiased genetic screens identified components of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery as genetic modifiers of C9orf72 toxicity in Drosophila expressing (G4C2)58, and in yeast expressing poly-proline-arginine (PR)5039,40. Poly-glycine-alanine (GA) formed intracellular aggregates that were found to sequester nuclear pore proteins, such as Pom121, in a new C9-ALS mouse model41. Additionally, several Nups, such as Pom121 and Nup107, were very long-lived proteins in post-mitotic cells and susceptible to oxidative insults. The poor turnover of damaged Nups as well as age-dependent decline of TFs may result in irreversible neuronal dysfunction and death42,43. Taken together, these studies suggest that defects in the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery may be central to the pathogenesis of C9-ALS.

Notably, several of these studies suggest that defects in nuclear transport leads to TDP-43 cytoplasmic mislocalization as a consequence. Ran has been identified as an essential regulator of TDP-43 nuclear localization44. The expression of (G4C2)30 RNA impaired the NM morphology and reduced the N-to-C Ran gradient. The reduction of nuclear Ran was found correlated with the nuclear depletion of TDP-43 in C9-ALS iPSC-derived neuron and GRN knockout mouse model33,44. The siRNA-mediated reduction of Nup62, CAS or Kpnb1 levels also triggered cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-4345.

In this study, however, we show that TDP-43 pathology itself triggers structural defects in the NM and NPCs with ensuing impairment of nucleocytoplasmic transport in mouse primary cortical neurons, as well as fibroblasts and iPSC-derived neurons from ALS patients. This is further supported by our observation of nuclear pore pathology in the brain tissues of pTDP-43-positive sALS and TDP-ALS cases but not those of pTDP-43-negative cases. Altered nuclear morphology has also been observed in brain samples of TDP-43 transgenic mice and human cases of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)-TDP46. Our data suggest a common role for NM and NPC pathology in the disease mechanism of most ALS/FTD cases. A broader role for nucleocytoplasmic transport defects in age-dependent neurodegeneration is further supported by the finding that the cytoplasmic aggregation of artificial β-sheet proteins, as well as fragments of mutant huntingtin and TDP-43, can interfere with mRNA export in HEK293T cells and mouse primary cortical neurons. This deficit may result from mislocalization of a subunit of the THO complex (THOC2), which is involved in mRNA export47. Interestingly, cytoplasmic but not nuclear β-sheet protein triggered cellular toxicity, and the mislocalization of nuclear transport factors and poly(A) RNA. Notably, an altered localization of Nups and TFs and nucleocytoplasmic transport function was also found as an age-dependent phenotype in a mutant huntingtin knock-in mouse model and Huntington’s disease patients34,48. These results suggest that several disease-associated protein aggregates can impair the NPC integrity and nucleocytoplasmic transport function. However, how protein aggregates in distinct compartments share a similar pathogenic mechanism in various diseases remains to be investigated in detail.

As a possible mechanistic explanation, we have identified PrLDs and low-complexity domain similar to those frequently found in RNA-binding proteins within FG-rich domains of several human Nups. These domains were both required and sufficient for co-aggregation with TDP-CTF. Interestingly, the arginine-rich DPRs including poly-PR and glycine-arginine (GR) can interact with membraneless organelles, such as nucleoli, NPCs and stress granules, through the low-complexity domains, and disrupt organelle function and dynamics49. The sorting capability of NPCs is driven by the phase separation of FG domains into dense and sieve-like hydrogels. A similar phase separation process driven by low-complexity domains has also been recognized in stress granule formation and the pathological transition into insoluble aggregates, making this process an important emerging principle in neurodegeneration50. Our findings suggest that the interaction of PrLDs in TDP-43 and those in FG-Nups may trigger the pathological cascade in a similar way.

We found that many Nups and TFs were affected by TDP-43 pathology. Interestingly, some components of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery were not affected, but instead prevented the cytoplasmic aggregation of TDP-CTF. The most pronounced effect was found for Kpnb1, which is involved in the nuclear import in concert with NLS-binding Kpna proteins. A previous screen of 82 proteins involved in nuclear transport has found that downregulation of Kpnb1 caused cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-4345.

Here we identified several genetic suppressors in our fly system. Among these, Nup98-96 and Nup107 mutations have been previously shown to reduce G4C2-mediated toxicity39. In a search for candidate genes near the gene locus of Hey, a Nup50 mutation was found to rescue the lifespan of TDP-43 transgenic flies29. The reduced expression of Nups may compensate the defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport and ameliorate TDP-43 toxicity by reducing cytoplasmic shuttling of TDP-43. We also found that pharmacological treatment with selective nuclear export inhibitors KPT-276 and KPT-335 rescued TDP-43 toxicity and defective nucleocytoplasmic transport function in cortical neurons and Drosophila, similar to its effect in C9-ALS models33, suggesting a potential therapeutic application in the majority of ALS cases.

Taken together, our data suggest that the disruption of the NM and NPCs and nucleocytoplasmic transport function may be a common pathogenesis in the vast majority of ALS and most of FTD with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Based on our findings, we propose that (1) cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 due to nucleocytoplasmic transport defects caused by the C9orf72 repeat expansion, can exacerbate these defects in a positive feedback loop; and (2) cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-43 can directly trigger nucleocytoplasmic transport defects by disrupting the localization of Nups and TFs (Supplementary Fig. 16). A better understanding of the role of TDP-43 in intracellular transport pathways may help in developing therapeutic strategies for ALS/FTD and other TDP-43 proteinopathies.

Online Methods

Constructs

The expression plasmids encoding nucleoporin (Nup) and nucleocytoplasmic transport factor (TF) fusion proteins were obtained from multiple sources (Supplementary Table 3). PCR-amplified human TDP-43 and TDP-CTF were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 myc-BioID vector (Addgene)12 as XhoI/KpnI fragments, and cloned from GFP expression plasmids into the Kpn2I/MluI sites of the APEX2-Actin plasmid (Addgene)20. TDP-CTF (aa 208-414) were generated by PCR, and Q331K, M337V and NLS (KRK….KVKR > AAA….AVAA)51 mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange II, Agilent), and cloned into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech) or mCherry vector. A flexible linker [(SGGG)3] was inserted between all the fusion partners to facilitate correct protein folding. PCR primers used to generate PrLD and non-PrLD fragments of Nup98: 5′-CAGATCTCCGGAGGCGGCTCCATGGAGATGTTTAACAAATCATTTGG-3′; 5′-ACAATTGCATCAACCTCCAGGCTGTGAGGCTTG-3′; 5′-CAGATCTCGATGCTTTTTGGGACAGCTACAAACACC-3′; 5′-ACAATTGATTCACTGTCCTTTTTTCTCTACCTGAGG-3′. PCR products were cloned into the BglII/MfeI sites of pEGFP-Nup98. PCR primers used to generate PrLD and non-PrLD fragments of Nup153: 5′-CGCTAGCTCTAGACTAGGGGACACCATGG-3′; 5′-GACCGGTGGTACAAAGGAGGATCCTGCAGAGCTAG-3′; 5′- CGCTAGCTCTAGACTAGGGGACACCATGTTTGGAACTGGACCCTCAGCACC-3′; 5′-GACCGGTGGTTTCCTGCGTCTAACAGC-3′. PCR products were cloned into the NheI/AgeI sites of pNup153-EGFP. PCR primers used to generate PrLD and non-PrLD of Nup214: 5′-CAGATCTCCGGAGGCGGCGCGATGGGAGACGAGATGGATG-3′; 5′-ACAATTGCATCAGGCAGCTGCTGTGCTGGCTGTG-3′; 5′-CAGATCTCCGGAGGCGGCGCGATGACACCACAGGTCAGCAGCTCAGG-3′; 5′-ACAATTGCCTCAGCTTCGCCAGCCACCAAAACCCTGG-3′. PCR products were cloned into pEGFP-Nup214 as BglII/MfeI fragments. GIPZ TDP-43 shRNA constructs (shTDP-43, V3LHS_636490) and a non-silencing control (shCtrl, RHS4346) were obtained from Open Biosystems.

Drosophila Genetics

All Drosophila stocks and crosses were maintained on standard yeast/cornmeal/molasses food at 22°C. GAL4 drivers (GMR GAL4 for retinal expression and D42 GAL4 for motor neuron expression) were used to express human TDP-43 with C-terminal YFP tag as previously described52. For controls, w1118 flies were crossed with the appropriate GAL4 driver. Drosophila lines harboring mutations in nuclear pore components were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and have the following genotypes: y[1]; P{y[+mDint2] w[BR.E.BR]=SUPor-P}Nup50[KG09557]; ry[506], w[*] P{w[+mC]=EP}Nup93-1[G9996], Nup98-96[339]/TM3, Sb[1] and y[1] w[67c23]; P{y[+t7.7] w[+mC]=wHy}Nup107[DG40512]/SM6a. Both female and male adults were tested.

Adult Eye Imaging

Adult fly eyes were imaged with a Leica MZ6 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP73 camera and controlled by Olympus DP Controller and Olympus DP Manager software. Individual images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe).

Larval Turning Assays

Larval turning was performed as described53. Briefly, crosses were carried out at 22°C and wandering third instar larvae were placed on a grape juice plate. After a short acclimation period, larvae were gently turned ventral side up. They were observed until they turned over (dorsal side up) and began making a forward motion. The time it took to complete this task was recorded.

For drug screening, UAS TDP-43 males were crossed with D42-GAL4 female virgins on fly food containing either DMSO, KPT-226 or KPT-335. For DMSO controls, the same volume of DMSO as the corresponding drug concentration was added. Crosses were made on drug food and maintained at 25°C. Both female and male larvae were tested.

Cell culture and transfection

All procedures for animal experiments were approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary cortical neurons were isolated from cerebral cortex of mixed male and female C57BL/6J mouse embryos at day 16.5 (E16.5) and cultured as previously described54. Briefly, cells were plated on coverslips coated with 0.5 mg/ml poly-L-ornithine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hrs in MEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS (Hyclone). After switching to complete neural cell culture medium (Neurobasal medium (Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies) and 2% B-27 supplements (Life Technologies)), cells were cultured for 5 days. Neurons were transected via magnetofection with 0.5 μg plasmid DNA and 1.75 μL NeuroMag (Oz Biosciences) as described55. Cells were cultured for 24 hrs and processed for immunofluorescence. For TDP-43 knockdown, cells were transfected with expression plasmids for shCtrl or shTDP-43, and cultured for another 5 days to efficiently reduce TDP-43 protein levels9. Transfection efficiency was in the range of 20–30% for overexpression, and 10–15% for TDP-43 knockdown experiments. shTDP-43 reduced TDP-43 protein levels to 61% of shCtrl-transfected cells.

Mouse Neuro-2a (N2a) neuroblastoma cells were plated in 6-well plates for immunoblotting or on coverslips in 12-well plates for immunofluorescence, and cultured in DMEM medium (Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS and 1% PenStrep (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were transfected with either Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) or PolyMag Neo (Oz Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and the medium was changed the next day. Cells were fixed 48 hrs after transfection. Transfection efficiency was in a range of 70–80%. N2a cells were obtained from ATCC (CCL-131) and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Collection of human fibroblasts was approved by the Emory and Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Boards, and informed consent for participation was obtained from every subject and/or an appropriate surrogate. Human fibroblasts of healthy control and ALS cases were plated on coverslips coated with 0.5 mg/ml poly-L-ornithine in DMEM containing 10% FBS supplemented with 0.5% PenStrep, 1% MEM with nonessential amino acids (NEAA) (Life Technologies) and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies).

Control and TDP-43 mutant iPS cell lines were cultured and maintained in MTeSR media (Stem Cell Technologies) in the presence of ROCK-inhibitor. During the neuralization stage, cells were cultured for 2 days in WiCell Medium (DMEM/F12, knockout serum replacement, 1% L-Glutamine, 1% NEAA, 110 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with 0.5 μM LDN (Stemgent) and 10 μM SB (Sigma) for BMP and SMAD pathway inhibition. To induce caudalization, cells were cultured for 5 days in 50% WiCell + 50% Neural Induction Media (NIM: DMEM/F12, 1% L-Glutamine, 1% NEAA, 1% N2, 1% Pen/Strep and 2 μg/ml heparin) and supplemented with 0.5 μM LDN, 10 μM SB and 0.5 μM retinoic acid (RA) (Sigma). For ventralization, cells were cultured and maintained in NIM supplemented with 0.5 μM RA, 200 ng/ml SHH-C (Peprotech), 10 ng/ml BDNF (Invitrogen) and 0.4 μg/ml ASAC (Sigma) for 7 days. At the stage of neural progenitor cell differentiation, cells were cultured for 6 days in 50% NIM + 50% Neural Differentiation Media (NDM: Neurobasal, 1% L-Glutamine, 1% NEAA, 1% N2, 1% Pen/Strep) and supplemented with 0.5 μM RA, 200 ng/ml SHH-C, 0.4 μg/ml ASAC, 2% B27, 10 ng/ml BDNF, 10 ng/ml GDNF (R&D systems), 10 ng/ml IGF (R&D systems) and 10 ng/ml CNTF (R&D systems). The media was then changed to 100% NDM. On differentiation day 32, iPS neurons were treated with 20 mM AraC (Sigma) for 48 hr to remove glial progenitors cells. 90% of cells were positive for Tuj-1 neuronal marker and 30–40% of the cells were positive for the motor neuron marker HB9 as previously described56. For co-culture of human iPSC-derived neurons with mouse astrocytes, starting DIV40, differentiated neurons were co-cultured on top of a confluent monolayer of mouse cortical astrocytes prepared from post-natal day 0–1 mouse pups. The cells were kept until DIV 54–57, when they were fixed for mAb414 and lamin B staining.

Affinity pulldown of biotinylated proteins and immunoblotting

N2a cells were transfected with expression plasmids for GFP, myc-BirA*-TDP-43 or myc-BirA*-TDP-CTF using Lipofectamine 3000. The culture medium was changed after 4 hrs and, the next day, biotin was added to the medium at 50 μM. After 24 hrs, cells were harvested and washed with cold 1×PBS three times before cell lysis in urea buffer (8M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5) supplemented with 1×protease inhibitor (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor (Roche) for 20 mins at room temperature (RT) with occasional vortexing. Cells were sonicated three times in two-second pulses and centrifugated at 20,000 g at RT for 15 mins. A small aliquot from the supernatant (input sample) was mixed with Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 mins. For the pulldown of biotinylated proteins, neutravidin beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were pre-washed with lysis buffer and incubated with the remaining lysate sample with constant rotation overnight at RT. Beads were collected by centrifugation and washed five times with lysis buffer. Twenty percent of the sample was reserved for immunoblotting and 80% were used for mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 1b, d).

Immunoblotting was performed according to standard protocols. Samples mixed with Laemmli buffer were heated for 5 minutes at 98°C and spun-down before running on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and electro-transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer (LiCor) for 1 hr, followed by incubation with primary antibodies including anti-myc (1:2000), anti-TDP-43 (1:2000), anti-α-Tubulin (1:10000) and anti-γ-Actin (1:10000) overnight at 4°C, and incubation with secondary antibodies (1:10000, LI-COR) in blocking buffer in 1×PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 hr at RT. Biotinylated proteins were detected with IRDye Streptavidin (1:10000). Blots were scanned on an Odyssey imager (LiCor).

Sample digestion for mass spectrometry analysis

Neutravidin beads were spun down and residual urea was removed. Digestion buffer (200 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3) was added and the bead solution was then treated with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 25°C for 30 mins, followed by 5 mM iodoacetimide (IAA) treatment at 25°C for 30 mins in the dark. Proteins were digested with 1 μg of lysyl endopeptidase (Wako) at RT for 2 hrs and further digested overnight with 1:50 (w/w) trypsin (Promega) at RT. Resulting peptides were desalted with a Sep-Pak C18 column (Waters) and dried under vacuum.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) was performed at the Emory Integrated Proteomics Core (EIPC) essentially as described57. The dried samples were resuspended in 10 μL of loading buffer (0.1% formic acid, 0.03% trifluoroacetic acid, 1% acetonitrile), vortexed for 5 minutes and centrifuged down at maximum speed for 2 minutes. Peptide mixtures (2 μL) were loaded onto a 25 cm × 75 μm internal diameter fused silica column (New Objective, Woburn, MA) self-packed with 1.9 μm C18 resin (Dr. Maisch, Germany). Separation was carried out over a 120 min gradient by a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano at a flowrate of 350 nL/min. The gradient ranged from 3% to 80% buffer B (buffer A: 0.1% formic acid in water, buffer B: 0.1 % formic in ACN). The mass spectrometer cycle was programmed to collect at the top speed for 3 second cycles. The MS scans (400–1600 m/z range, 200,000 AGC, 50 ms maximum ion time) were collected at a resolution of 120,000 at m/z 200 in profile mode and higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) MS/MS spectra (0.7 m/z isolation width, 30% collision energy, 10,000 AGC target, 35 ms maximum ion time) were detected in the ion trap. Dynamic exclusion was set to exclude previous sequenced precursor ions for 20 seconds within a 10 ppm window. Precursor ions with +1, and +8 or higher charge states were excluded from sequencing.

Database search

All raw data files were processed using the Proteome Discoverer 2.0 data analysis suite (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). The database was downloaded from Uniprot (April 15, 2015) and consists of 53,291 mouse target sequences supplemented with 2 BirA*-fusion sequences. Peptide matches were restricted to fully tryptic cleavage, a precursor mass tolerance of +/− 10 ppm and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.6 Da. Dynamic modifications were set for methionine oxidation (+15.99492 Da), asaparagine and glutamine deamidation (+0.98402 Da), lysine ubiquitination (+114.04293 Da), biotinylation (+226.2994 Da) on N terminus and lysine and protein N-terminal acetylation (+42.03670). A maximum of 3 modifications were allowed per peptide (up to 2 missed cleavages) and a static modification of +57.021465 Da was set for carbamidomethyl cysteine. The Percolator58 node within Proteome Discoverer was used to filter the peptide spectral match (PSM) false discovery rate to 1%.

Identification of the TDP-43 and TDP-CTF interactome

Urea homogenates were collected from N2a cells transfected with expression vectors for GFP (Mock control), BirA*-TDP-43 and BirA*-TDP-CTF. The experiment was performed with two biological replicates. Four different comparisons of proteomic data were performed: (1) BirA*-TDP-43 versus Mock control; (2) BirA*-TDP-CTF versus Mock control; (3) BirA*-TDP-43 versus BirA*-TDP-CTF; (4) BirA*-TDP-CTF versus BirA*-TDP-43. To filter the results, in comparisons 1 and 2, a protein was identified as TDP-43 or TDP-CTF associated if there was no missing data, the average number of peptide spectrum matches (PSM) in the TDP-43 or TDP-CTF associated proteome was ≥ 10 and Mock ≤ 2. In comparisons 3 and 4, the same criteria were also applied to a protein considering a TDP-43-preferred interactor when the PSM in BirA*-TDP-43 was ≥ 10 and Mock ≤ 2, and the fold increase was ≥ 2^0.5 as compared to the PSM in BirA*-TDP-CTF, and vice versa. Mock control cells provided the background levels of endogenous biotinylation and unspecific pulldown. The identification of BirA*-TDP-43- or BirA*-TDP-CTF-preferred interactors addresses their cellular compartment- and function-specific roles. These proteins were analyzed and categorized on the basis of biological process, cellular component and molecular function using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Bioinformatic Resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

Bioinformatics analyses

Prion-like amino acid composition of human Nups and TFs was predicted by the open-source PLAAC algorithm (http://plaac.wi.mit.edu/). The log-likelihood ratio (LLR) score allows for the exploratory screening of potential PrLDs. Since low content of hydrophobic residues and high net charge are known predictors for low-complexity sequence domains and intrinsically disordered proteins, we performed a predictive analysis of mean hydrophobicity using ProtScale (http://web.expasy.org/protscale/) with the hydrophobicity scale of Kyte and Doolittle. Hydrophobic amino acids include Ala (1.8), Cys (2.5), Gly (−0.4), Ile (4.5), Leu (3.8), Met (1.9), Phe (2.8) and Val (4.2), and hydrophilic residues include Arg (−4.5), Asn (−3.5), Asp (−3.5), His (−3.2), Lys (−3.9), Pro (−1.6), Gln (−3.5), Glu (−3.5) and Tyr (−1.3). Low-complexity and intrinsic disorder predictions were performed using DisEMBL version 1.5 (http://dis.embl.de/) and GlobPlot version 2.3 (http://globplot.embl.de/) to validate the relationship between hydrophobicity and protein intrinsic disorder in human Nups and TFs.

Immunofluorescence and image acquisition and analysis

To validate the interaction of Nups and TFs with TDP-CTF, N2a cells were co-transfected with expression plasmids for GFP or epitope-tagged Nups or TFs (Supplementary Table 3) and mCherry or mCherry-tagged TDP-CTF. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1×PBS 48 hrs after transfection for 15 mins at RT, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1×PBS for 5 mins, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 45 mins. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies including anti-myc (1:200), anti-FLAG (1:500), anti-HA (1:500), anti-T7 (1:500), anti-TDP-43 (1:500), anti-pTDP-43 (S409/410) (1:500), anti-SQSTM1/p62 (1: 1000), anti-nuclear pore complex proteins (mAb414; 1:1000), anti-Nup98 (1:500), anti-Nup205 (1:100), anti-Lamin B (1:200), anti-Sun2 (1:100), anti-Nesprin-2 (1:100), anti-Ran (1:500), anti-RanGAP1 (1:300) and anti-γH2AX (1:500) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and streptavidin for 1 hr at RT. F-actin was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 or Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (1:1000) for 1 hr at RT.

To examine DNA damage, cortical neurons were transfected with expression plasmids for GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-CTF, TDP-43WT or TDP-43Q331K. γH2AX has been identified as the marker of DNA double-strand breaks59. The mean pixel intensity of stained γH2AX in the nucleus of human fibroblasts and transfected cortical neurons was analyzed by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). DNA damage inducing calicheamicin γ1 (CLM) was added at 5 nM for 2 hrs as a positive control.

To quantitate the percentage of cells that have morphological abnormalities in the NM stained with anti-lamin B or anti-RanGAP1 antibodies, the presence of irregularity, distortion or rifts in the NM was scored. For 3D reconstructions of whole nuclei, lamin B staining was used to outline the nuclear region of cortical neurons. On average 45 to 50 Z-stack sections at 0.3 μm steps were required to reconstruct the whole nucleus using Imaris software (Bitplane). A surface was created to mask the nucleus with a smooth factor of 0.3 μm. The optical sections at XY, XZ and YZ plane were generated.

To investigate the nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins, NES-tdTomato-NLS, a protein transport reporter60, was transfected into human fibroblasts or co-transfected with expression plasmids for GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-CTF, TDP-43WT, TDP-43Q331K, TDP-43M337V or TDP-43mtNLS into cortical neurons. The mean pixel intensity of NES-tdTomato-NLS and GFP-TDP-43 in the nucleus and cytoplasm were measured for calculating the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic (N-to-C) ratio. To examine whether induction of apoptosis causes a similar defect in the nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins, the GFP transfected cells were incubated with staurosporine (STS) at 50 nM or 250 nM for 12 hrs to induce caspase-3/9-dependent apoptosis61. The inhibition of nuclear protein import was induced by importazole (IPZ)62 at 2.5 μM or 5 μM for 12 hrs. DMSO was added as the vehicle control.

For high-resolution imaging, Z-series (15–50 sections, 0.15–0.3 μm steps) were acquired according to the different experimental designs with an epifluorescence microscope (Ti, Nikon) equipped with a cooled CCD camera (HQ2, Photometrics). Within each experiment, all groups were imaged with the same acquisition settings. Image stacks were deconvolved using a 3D blind constrained iterative algorithm (AutoQuant, Media Cybernetics).

For visualization of NPCs, super-resolution 3D structured illumination microscopy (SIM) was performed on a Nikon microscope using a 100× (1.49 NA) object. 10–30 Z-stacks were acquired per image to capture the entire nuclear volume and SIM reconstructions were performed in NIS elements (Nikon). Fourier transformations were applied to assess reconstruction quality. 3D SIM images were analyzed in ImageJ. Series of widefield images were acquired and merged with the super-resolution image of Nup98 and mAb414 staining.

For imaging iPSC-derived neurons, images were taken on a LSM800 confocal microscope using Airyscan mode super-resolution. All images represent Z-optical slices of the nuclear membrane. Eighty to ninety cells were analyzed per group per staining.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunofluorescence

Cortical neurons and human fibroblasts were washed with 1×PBS and fixed with 4% PFA in 1×PBS for 10 mins. FISH was performed with some modifications of previously described method63. Briefly, fixed cells were permeabilized with 50%, 70% and 100% ethanol in subsequent steps and stored at −20°C for overnight and rehydrated the next day with 1×SSC for 10 mins. Cells were washed with 10% formamide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 mins and incubated in hybridization buffer (20% dextran sulfate, 4×SSC, 4 mg/mL BSA, 20 mM ribonucleoside vanadyl complex, and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) at 37°C for 1.5 hrs. To detect poly(A) RNAs, 1 μL biotinylated oligo-(dT) probes (Biosearch Technologies) were resuspended with 10 μg each of E. coli tRNA and salmon sperm DNA in 50 μL of hybridization buffer and incubated with the coverslips at 37°C overnight. Oligo-(dA) probes were used as a negative control. Cells were washed by 1×PBS for 10 mins to remove formamide, blocked with 5% BSA for 45 mins, and incubated with Cy3-conjugated streptavidin for 1 hr at RT to detect the biotinylated oligo-(dT) probes. Mean pixel intensities for poly(A) RNA in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cells were determined with ImageJ software.

Metabolic labeling of newly synthesized proteins

Cortical neurons were transfected with expression vectors for GFP or GFP-tagged TDP-43WT or TDP-CTF. After 24 hrs, cells were incubated in methionine-free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with or without 40 μM anisomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr at 37°, followed by incubation with 100 μg/mL L-azidohomoalanine (AHA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 mins. Cells were washed with 1×PBS and fixed by 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 mins and blocked with 3% BSA in 1×PBS for 30 mins. Click-iT reaction cocktail (50 μL per sample) was prepared right before the end of blocking using Click-iT assay kits and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated alkyne (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were incubated for 30 mins at RT and washed with 3% BSA in 1×PBS before mounting. The mean pixel intensity of AHA in the cell body was quantified with ImageJ software.

Electron microscopy (EM) of nuclear envelope

To visualize nuclear envelope morphology in transfected N2a cells by EM, we used fusion constructs of the engineered APEX2 peroxidase with FLAG-tagged TDP-43 and TDP-CTF20. N2a cells were transfected with expression plasmids for FLAG-APEX2-TDP-43, FLAG-APEX2-TDP-CTF or GFP-TDP-CTF. Cells were fixed with PFA and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. APEX2 catalyzes the deposition of 3,3′-diaminobenzoic acid (DAB), which allowed us to identify APEX2-TDP-43 and APEX2-TDP-CTF expressing cells under EM (JEOL JEM-1400).

Immunohistochemistry

All procedures for collection of human brain tissue were approved by the Emory University and Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their authorized legal representatives. Paraffin embedded sections from post-mortem human motor and frontal cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum of 8 μm thickness were deparaffinized by incubation in a 60°C oven for 30 mins and rehydrated by immersion in Histo-Clear and 100% ethanol and 95% ethanol solutions. Antigen retrieval was then performed as sections were microwaved in 10mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 for a total of 5 mins and allowed to cool to RT for 30 mins. Peroxidase quenching was performed as sections were incubated in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution in methanol for 5 mins at 40°C and then rinsed in Tris-Brij buffer (1M Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 100mM NaCl, 5mM MgCl2, 0.125% Brij 35). For blocking, sections were incubated in normal goat serum (Elite Vectastain ABC kit) for 15 mins at 40°C. Sections were then incubated with Nup205 (1:50), Lamin B1 (1:300) or RanGAP1 (1:50) (diluted in 1% BSA in tris-brij 7.5) overnight at 4°C. The following day sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody at 5 μL/mL (Elite IgG Vectastain ABC kit) for 30 mins at 37°C and then incubated with the avidin-biotin enzyme complex (Vector Laboratories) for 30 mins. Stains were visualized by incubation of DAB Chromogen (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 mins at RT. Slides were then dehydrated in an ethanol series and mounted with cover slips. Investigators were blinded for quantitative analysis of IHC staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA based on the experimental design. Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in the previous literatures in the field33,39,64. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments, except for quantitative analysis of human fibroblasts and IHC staining. In this study, no animals/samples were assigned to experimental groups, and therefore no randomization was performed. Data from different experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Software. Differences were considered statistically significant for P values < 0.05.

Data availability

Data available on reasonable request from the authors. Proteomic source data are available from Synapse (http://www.synapse.org) via accession syn11597066. Figure 2 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 are associated with the source data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathryn R. Moss and Kristen T. Thomas for help with the preparation of primary cortical neurons, Gary J. Bassell for logistical support, and Monica Castanedes-Casey for expert staining of human brain tissue. For numerous expression plasmids used in this study (Supplementary Table 3), we thank Martin Hetzer, Jan Ellenberg, Valérie Doye, Jose Teodoro and Jomon Joseph, Larry Gerace, Bryce Paschal, and Mary Dasso. We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for fly lines, and Emory Integrated Proteomics Core, Neuropathology/ Histochemistry Core and Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy Core for technical support. This work was supported by grants from the ALS Association (17-IIP-353) to W.R., and (16-IIP-278) to R.S., the Emory Medicine Catalyst Funding Program to W.R., Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA348086) to R.S., and NIH grants K08-NS087121 to C.M.H., P30-NS055077 to the Neuropathology/Histochemistry core of the Emory NINDS Neurosciences Core Facility, AG025688 to Emory’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, NIH R01-NS091299 to D.C.Z., R35-NS097261 to R.R., R01-NS085207 to R.S., R01NS091749 to W.R., R01-NS093362 to W.R. and T.K., who is also supported by The Bluefield Project to Cure FTD, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation to N.J.C, and NIH R01-AG053960 to N.T.S., who is also supported in part by an Alzheimer’s Association (ALZ), Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK), The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF), and the Weston Brain Institute Biomarkers Across Neurodegenerative Diseases Grant (11060). S.V. was partially funded by UBRP with funds from the UA Provost’s Office. P.G.D. was funded by an ARCS Fellowship Roche Foundation Award.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

W.R. conceived and directed the project. C-C.C., Y.Z. and W.R. designed the experiments. C-C.C. and W.R. interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. C-C.C. characterized protein interactome, performed bioinformatic analysis and conducted experiments in N2a cells, primary cortical neurons and human fibroblasts with help from F.L. and Y.H.C.. Y.Z. performed the BioID pulldown and sample preparation for LC-MS/MS analysis. M.E.U. performed immunohistochemistry staining. S.W.V., M.S. and D.C.Z. performed Drosophila experiments. I.L. and R.S. performed experiments in iPSC-derived motor neurons. C-C.C. and P.G.D. conducted SIM experiments. D.M.D., N.T.S. and M.A.P. provided technical support. T.K. provided key reagents. C.M.H., M.G., N.J.C., K.B.B., D.W.D., R.R., Y-J.Z., L.P. and J.D.G. provided patient tissue with associated clinical and genetics data.

Competing Financial Interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Accession codes

A Life Science Reporting Summary is available.

References

- 1.Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igaz LM, et al. Enrichment of C-terminal fragments in TAR DNA-binding protein-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in brain but not in spinal cord of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:182–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 binds heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B through its C-terminal tail: an important region for the inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exon 9 splicing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37572–37584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gitcho MA, et al. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:535–538. doi: 10.1002/ana.21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nonaka T, Kametani F, Arai T, Akiyama H, Hasegawa M. Truncation and pathogenic mutations facilitate the formation of intracellular aggregates of TDP-43. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3353–3364. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo W, et al. An ALS-associated mutation affecting TDP-43 enhances protein aggregation, fibril formation and neurotoxicity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:822–830. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li YR, King OD, Shorter J, Gitler AD. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallini C, Bassell GJ, Rossoll W. The ALS disease protein TDP-43 is actively transported in motor neuron axons and regulates axon outgrowth. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3703–3718. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou CC, et al. PABPN1 suppresses TDP-43 toxicity in ALS disease models. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5154–5173. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Igaz LM, et al. Expression of TDP-43 C-terminal Fragments in Vitro Recapitulates Pathological Features of TDP-43 Proteinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8516–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809462200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roux KJ, Kim DI, Raida M, Burke B. A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:801–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DI, et al. Probing nuclear pore complex architecture with proximity-dependent biotinylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2453–2461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406459111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rout MP, et al. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim L, Wei Y, Lu Y, Song J. ALS-Causing Mutations Significantly Perturb the Self-Assembly and Interaction with Nucleic Acid of the Intrinsically Disordered Prion-Like Domain of TDP-43. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halfmann R, Wright JR, Alberti S, Lindquist S, Rexach M. Prion formation by a yeast GLFG nucleoporin. Prion. 2012;6:391–399. doi: 10.4161/pri.20199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey S, Gorlich D. A saturated FG-repeat hydrogel can reproduce the permeability properties of nuclear pore complexes. Cell. 2007;130:512–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato M, et al. Cell-free formation of RNA granules: low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell. 2012;149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam SS, et al. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat Methods. 2015;12:51–54. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala YM, Misteli T, Baralle FE. TDP-43 regulates retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation through the repression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3785–3789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800546105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Bonne G, Yaou RB, Hutchison CJ. Nuclear lamins: laminopathies and their role in premature ageing. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:967–1008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost B, Bardai FH, Feany MB. Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies. Curr Biol. 2016;26:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crisp M, et al. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, et al. Nesprin-1 and -2 are involved in the pathogenesis of Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and are critical for nuclear envelope integrity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2816–2833. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita T, Aizawa H, Teramoto S, Akamatsu M, Kwak S. Calpain-dependent disruption of nucleo-cytoplasmic transport in ALS motor neurons. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39994. doi: 10.1038/srep39994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estes PS, et al. Motor neurons and glia exhibit specific individualized responses to TDP-43 expression in a Drosophila model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2013;6:721–733. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinoshita Y, et al. Nuclear contour irregularity and abnormal transporter protein distribution in anterior horn cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1184–1192. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181bc3bec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan L, Hanson KA, Kim SH, Tare A, Tibbetts RS. Identification of genetic modifiers of TDP-43 neurotoxicity in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairns NJ, et al. TDP-43 proteinopathy in familial motor neurone disease with TARDBP A315T mutation: a case report. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;36:673–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]