Abstract

The stagnation in drug development for schizophrenia highlights the need for better translation between basic and clinical research. Understanding the neurobiology of schizophrenia presents substantial challenges but a key feature continues to be the involvement of subcortical dopaminergic dysfunction in those with psychotic symptoms. Our contemporary knowledge regarding dopamine dysfunction has clarified where and when dopaminergic alterations may present in schizophrenia. For example, clinical studies have shown patients with schizophrenia show increased presynaptic dopamine function in the associative striatum, rather than the limbic striatum as previously presumed. Furthermore, subjects deemed at high risk of developing schizophrenia show similar presynaptic dopamine abnormalities in the associative striatum. Thus, our view of subcortical dopamine function in schizophrenia continues to evolve as we accommodate this newly acquired information. However, basic research in animal models has been slow to incorporate these clinical findings. For example, psychostimulant-induced locomotion, the commonly utilised phenotype for positive symptoms in rodents, is heavily associated with dopaminergic activation in the limbic striatum. This anatomical misalignment has brought into question how we assess positive symptoms in animal models and represents an opportunity for improved translation between basic and clinical research. The current review focuses on the role of subcortical dopamine dysfunction in psychosis and schizophrenia. We present and discuss alternative phenotypes that may provide a more translational approach to assess the neurobiology of positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Incorporation of recent clinical findings is essential if we are to develop meaningful translational animal models.

Introduction

Our knowledge of the neurobiology of schizophrenia, while still rudimentary, has advanced considerably in recent years. However, these findings have not translated to better treatments for those with schizophrenia. The three primary symptom groups, positive, cognitive and negative (Box 1), have been associated with reports of abnormalities in virtually every neurotransmitter system1–5. The onset of psychotic symptoms, which is strongly associated with alterations in dopamine function, is a key feature underpinning a clinical diagnosis6, 7. However, results from clinical research regarding the specific loci of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia8–10, have triggered a reappraisal of our perspective on the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Currently there is a disparity between the tests for positive symptoms in animal models and recent clinical evidence for dopaminergic abnormalities in schizophrenia. Therefore, it is critical that this contemporary clinical knowledge actively influences the agenda in applied basic neuroscience.

Box 1: Symptom groups in schizophrenia

-

Positive symptoms

: Positive symptoms include delusions and hallucinations, linked to aberrant salience. These symptoms are most recognisable during periods of acute psychosis.

-

Cognitive symptoms

: Impairments in learning, memory, attention and executive functioning are all included as cognitive symptoms.

Negative symptoms: Negative symptoms include blunting of affect (lacking emotional expression), avolition (deficits in motivation) and social withdrawal.

It is widely acknowledged that we cannot recreate the complicated symptom profile of schizophrenia in animal models. However, animal models (the majority and focus of the present article being rodent models) provide an avenue to invasively explore the role of neurotransmitters and circuitry in psychiatric diseases. To improve the poor predictive validity of treatments in animal models11, it is critical that our understanding and the use of animal models evolves alongside our knowledge of schizophrenia neurobiology. The delayed incorporation of new clinical findings to develop better animal models highlights the need for better communication between clinical and basic research communities.

In this article, we discuss the challenges clinicians and researchers are facing in understanding the neurobiology of positive symptoms and psychosis in schizophrenia. We discuss the implications this has for current assessments of positive symptoms in rodents and propose a more relevant set of tests for future study. Finally, the need for a joint focus on bi-directional translation between clinical and basic research is outlined.

Challenges in diagnosing schizophrenia

Psychiatric symptoms exist on continua from normal to pathological, meaning the threshold for diagnosis of schizophrenia in clinical practice can be challenging. The clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia relies heavily on the positive symptoms associated with a prolonged psychotic episode. However, a relatively high percentage of the general population (8–30%) report delusional experiences or hallucinations in their lifetime12–14, but for most people these are transient15. Psychotic symptoms are also not specific to a particular mental disorder16. The clinical efficacy of antipsychotic drugs is heavily correlated with their ability to block subcortical dopamine D2 receptors17, 18, suggesting dopamine signalling is important. In spite of this, no consistent relationship between D2 receptors and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia has emerged19, 20. In contrast, the clinical evidence points towards presynaptic dopamine dysfunction as a mediator of psychosis in schizophrenia19.

The neurobiology of psychosis: the centrality of dopamine

Dopamine systems: anatomy and function

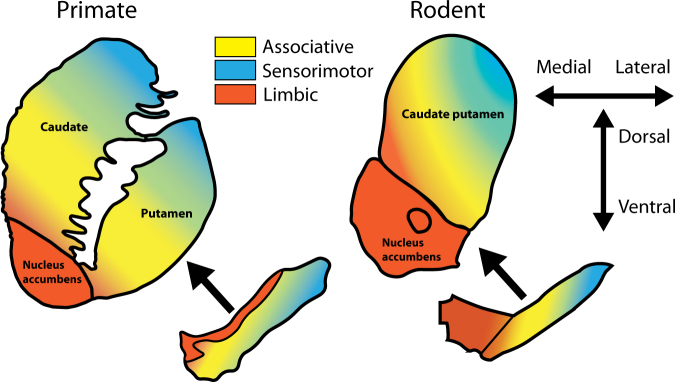

An appreciation for the neuroanatomical differences in subcortical dopaminergic projections/circuitry between rodents and primates is essential for effective communication between clinical and basic researchers. For example, primates feature a more prominent substantia nigra and less distinctive ventral tegmental area than rodents. However, more pertinent to the current review are homologous functional subdivisions of the striatum observed in both rodents and primates21–24. These include the limbic, associative and sensorimotor areas (Fig. 1). The associative striatum, defined by its dense connectivity from the frontal and parietal associative cortices, is key for goal-directed action and behavioural flexibility. The limbic striatum, defined by connectivity to the hippocampus, amygdala and medial orbitofrontal cortex, is involved in reward and motivation. The sensorimotor striatum, defined by connectivity to sensory and motor cortices, is critical for habit formation. These functional subdivisions are also interconnected by feedforward striato-nigro-striatal projections25. The heavy basis on behavioural outcomes in neuropsychiatry has made functional subdivisions such as these more relevant than ever.

Fig. 1. Functional subdivisions of the dopamine system across species.

Midbrain dopamine neurons are the source of dopamine projections to the striatum in primates (left) and rodents (right). Important neuroanatomical differences exist, especially when considering functional subdivisions of the striatum. In the primate, the limbic system (orange) originates in the dorsal tier of the substantia nigra (the ventral tegmental area equivalent). In the rodent, the limbic system originates in ventral tegmental area, which sits medially to the substantia nigra. The midbrain projections to the associative striatum (yellow) and sensorimotor striatum (blue) follow a dorsomedial-to-ventrolateral topology

Dopaminergic features of psychosis in schizophrenia

In healthy individuals, dopamine stimulants such as amphetamine can induce psychotic symptoms26, 27 and people with schizophrenia are more sensitive to these effects27, 28. Studies using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging have shown patients with schizophrenia show increases in subcortical synaptic dopamine content29, 30, abnormally high dopamine release after amphetamine treatment30–35 and increased basal dopamine synthesis capacity (determined indirectly by increased radiolabelled L-DOPA uptake)19,36, 37 compared with healthy controls. Increased subcortical dopamine synthesis and release capacity are strongly associated with positive symptoms in patients33, 38, and increased subcortical synaptic dopamine content is predictive of a positive treatment response29. It was widely anticipated that the limbic striatum would be confirmed as the subdivision where these alterations in dopamine function would be localised in patients. The basis for this prediction was the belief that reward systems were aberrant in schizophrenia39. However, as PET imaging resolution improved it was found that increases in synaptic dopamine content9, 10 and synthesis capacity8 were localised, or more pronounced37, in the associative striatum (Fig. 1; yellow). Furthermore, alterations in dopamine function within the associative striatum likely contribute to the misappropriate attribution of salience to certain stimuli, a key aspect of delusions and psychosis40.

Clinical studies have confirmed that dopamine abnormalities are also present prior to the onset of psychosis in schizophrenia and thus are not a consequence of psychotic episodes or antipsychotic exposure. Similar to what has been observed in patients with schizophrenia, ultra-high risk (UHR) subjects show increased subcortical synaptic dopamine content41 and basal dopamine synthesis capacity8, 42–44. Importantly, alterations in dopamine synthesis capacity in UHR subjects progress over time45 and are greater in subjects who transition to psychosis compared with those who do not46. Furthermore, higher baseline synaptic dopamine levels in UHR subjects predicts a greater reduction in positive symptoms after dopamine depletion41. Overall, these findings in UHR subjects are congruent with those observed in schizophrenia and provide evidence indicating that presynaptic dopaminergic abnormalities are present prior to the onset of psychosis.

Several avenues have been proposed to explain a selective increase in associative striatal dopamine function, such as alterations in hippocampal control of dopamine projections47, 48, alterations in cortical inputs to midbrain dopamine systems2, 49 and, although little direct evidence has been observed, developmental alterations in dopamine neurons themselves50, 51. Furthermore, other pathways and/or neurotransmitters may be more critical in treatment-resistant patients52. We propose a network model whereby dysfunction in a central circuit, including the associative striatum, prefrontal cortex and thalamus, is critical for the expression of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. This model would suggest that dysfunction in auxiliary circuits (both limbic and cortical) contribute to psychotic symptoms by feeding into this primary network. Ascertaining the role of dopaminergic dysfunction, in the context of networks important for psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia, will provide a better base for constructing objective readouts in basic and clinical research.

Psychosis: a consequence of network dysfunction

Psychosis is a condition that features a range of behavioural alterations that relate to a loss of contact with reality and a loss of insight. People with psychosis experience hallucinations (primarily auditory in schizophrenia53) and delusions. In schizophrenia, auditory hallucinations have been associated with altered connectivity between the hippocampus and thalamus54. During hallucinations, increased activation of the thalamus, striatum and hippocampus have also been observed55. Thus, altered thalamocortical connectivity, especially with the hippocampus, may impede internal/external representations of auditory processing56. In contrast, delusions in people with schizophrenia have been associated with overactivation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and diminished deactivation of striatal and thalamic networks57. Thus, the complexity of psychotic symptoms is congruent with the highly connected nature of implicated brain regions.

Although we still know little about the underlying neurobiology of psychosis, focal brain lesions allow for a better understanding of the networks involved without the confounds of medication and unrelated neuropathology. Generally speaking, lesions that induce hallucinations are often in the brain networks associated with the stimulus of the hallucination (i.e., auditory, visual or somatosensory)58. Visual hallucinations have been associated with dysfunction of the occipital lobe, striatum and thalamus, whereas auditory hallucinations are associated with dysfunction of the temporal lobe, hippocampus, amygdala and thalamus58. Insight is generally maintained after focal brain lesions that produce hallucinations and subcortical dopamine function is normal59, unlike what is observed in schizophrenia58. In contrast, a loss of insight (which can manifest as delusionary beliefs) is associated with alterations in cortico-striatal networks. For example, people with basal ganglia or caudate lesions can present with both hallucinations and delusions60, 61. Furthermore, a case study of religious delusions in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy was associated with overactivity of the PFC62, and there are multiple lines of evidence suggesting that the PFC is integral for delusionary beliefs63. Therefore, while impairing networks specific to certain sensory modalities can lead to hallucinations, dysfunctional integration of PFC input to the associative striatum may be especially important for delusional symptoms in schizophrenia.

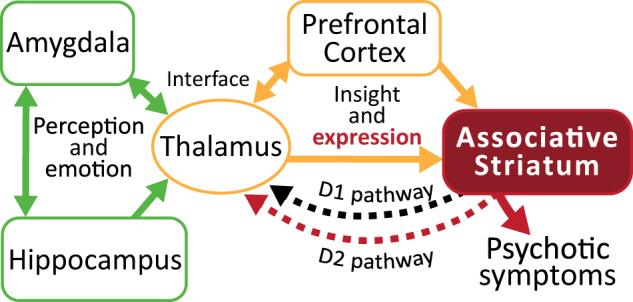

Central to the networks involved in psychosis and schizophrenia, the thalamus acts as a relay for most information going to the cortex64. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated that medication-naive patients with schizophrenia have significantly reduced thalamic and caudate volumes relative to healthy controls and medicated patients65. Moreover, reduced thalamic volumes has also been observed in UHR subjects66. A simplified schematic of the networks that may be especially relevant to psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia is presented in Fig. 2. The thalamus forms a circuit with the associative striatum and PFC whereby impairments in any of these regions can impair the functionality of the network as a whole. In addition, the hippocampus and amygdala, which are both involved in sensory perception and emotional regulation, can affect this network via their connectivity with the thalamus (but other indirect pathways also exist). Although this is an over simplification, it highlights how psychotic symptoms could arise from multiple sources of neuropathology/dysfunction or abnormal connectivity.

Fig. 2. Network implicated in psychotic symptoms and schizophrenia.

Dysfunction in a variety of brain regions can elicit psychotic symptoms. A primary circuit involved in psychosis includes the thalamus and prefrontal cortex (yellow) feeding into the associative striatum. Alterations in the thalamus and prefrontal cortex are involved in hallucinations and also insight for delusional symptoms. Expression of psychotic symptoms in most cases requires increased activity in the associative striatum and specifically excessive D2 receptor stimulation (red). Other limbic regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala (green) can feed into this circuit contributing to altered sensory perception and emotional context

Why do antipsychotics work?

This raises important questions as to how antipsychotic drugs exert their effects. In most individuals with schizophrenia, antipsychotic treatment is effective in reducing positive symptoms67; therefore, excessive D2 signalling in the associative striatum appears to be critical. Stimulation of D2 and D1 receptor expressing medium spiny neurons (which are largely segregated68) in the associative striatum feedback indirectly to the thalamus, completing a loop that allows for feedforward-based and feedback-based signalling. The basal ganglia acts as a gateway for, or mediator of, cortical inputs69–71 and may represent a common pathway through which psychotic symptoms present. Therefore, excessive dopamine signalling in the associative striatum may directly lead to psychotic symptoms by compromising the integration of cortical inputs. In treatment-responsive patients, antipsychotics may attenuate the expression of psychotic symptoms by normalising excessive D2 signalling29 to restore the balance between D1 and D2 receptor pathways72. Because they act downstream to schizophrenia-related presynaptic abnormalities, they fail to improve indices of cortical function (i.e., cognitive symptoms). Alternatively, impaired cortical input to the associative striatum via the thalamus, PFC or other regions could dysregulate this system independently of, or in addition to, associative striatal dopamine dysfunction. In this case, D2 receptor blockade may be insufficient to restore normal function, which is one explanation for why some individuals are treatment refractory. For example, increases in subcortical synaptic dopamine content29 and increases in presynaptic striatal dopamine function52 are both associated with increased treatment efficacy. Thus, in treatment-resistant subjects, there is little evidence of abnormal dopaminergic function29, 52. Medicated persons with schizophrenia, who remain symptomatic with auditory hallucinations, show increased thalamic, striatal and hippocampal activation55. Moreover, treatment-refractory patients who respond positively to clozapine treatment show alterations in cerebral blood flow in fronto-striato-thalamic circuitry, suggesting clozapine is restoring a functional imbalance in these systems73. Taken together, this evidence suggests that psychosis is the result of a network dysfunction that includes a variety of brain regions (and multiple neurotransmitter-specific pathways), of which impairment at any level could precipitate psychotic symptoms.

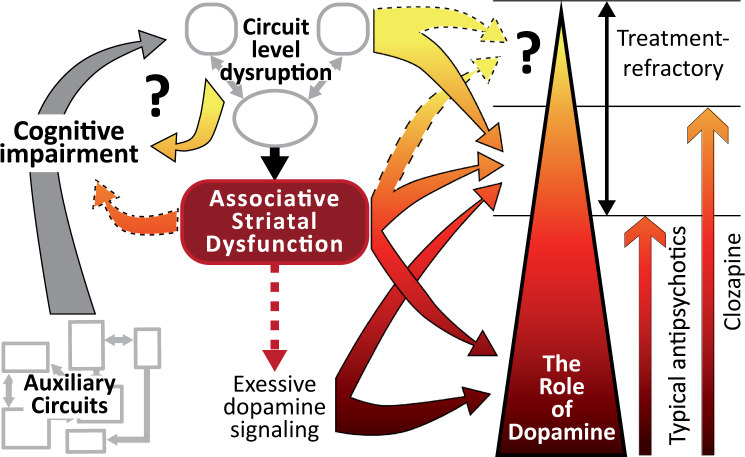

Although increased positive symptom severity has been associated with impaired cognitive flexibility74, there is a little evidence for subcortical hyperdopaminergia playing a direct role in the cognitive impairments observed in schizophrenia. Furthermore, antipsychotic treatments do not improve patient’s cognitive function75. There is a mounting evidence that cognitive symptoms may present prior to positive symptoms in schizophrenia76. Given brain networks involved in hallucinations and delusions all involve cortical regions, the underlying pathology causing cognitive symptoms may also contribute to psychotic symptoms. Thus, in some cases psychosis may represent the summation of broad cognitive impairments inducing local network dysfunction (Fig. 3). Regardless, positive symptoms are relatively distinct in the clinical setting but the presence and severity of symptoms are determined interactively with interviews and questionnaires. The inability to do the same in other species means the best avenue for assessing animal models may be to identify outcomes that are sensitive to the underlying neurobiology observed in schizophrenia and psychosis. Given the action/effectiveness of antipsychotics, the primary downstream region of interest, in the context of elevated dopamine transmission, is the associative striatum.

Fig. 3. Psychosis: a consequence of severe circuit specific cognitive impairment.

This schematic representation highlights the potential for cognitive symptoms to feed into psychosis networks and create positive feedback loops that spiral to psychosis. Non-specific and heterogeneous deficits in auxiliary neurocircuitry (in the context of psychosis) lead to broad cognitive impairments unique to each individual. These systems feed into the primary psychosis networks leading to destabilisation of associative striatal dysfunction and further cognitive impairment. In most individuals with schizophrenia, excessive dopamine signalling in the associative striatum leads to positive symptoms. Antipsychotics antagonise downstream D2 receptor signalling to blunt the expression of symptoms. In treatment-refractory patients (those who do not respond to first-line antipsychotics) blocking D2 receptors is insufficient to blunt positive symptoms suggesting further upstream dysfunction in the associative striatum or psychosis networks. Clozapine may lead to improvement in some of these individuals by stabilising function throughout these networks in addition to D2 receptor antagonism. Positive symptoms in treatment-refractory patients who fail to respond to clozapine may be the result of severe impairment throughout psychosis networks (and the associative striatum) that are independent of dopamine dysfunction. Thus, our current treatments for positive symptoms act downstream of the source of cognitive impairments, hence their ineffectiveness in treating cognitive symptoms. While the expression of psychotic symptoms may be a discrete outcome, separate to impairments in cognitive function, the upstream cause of these symptoms may share common neuropathology

Modelling psychosis: the use of animal models

Potentially, the most useful avenue for animal models to assist in schizophrenia research will be identifying convergent aetiological pathways77. Understanding which neurotransmitter systems and brain regions are most involved may help to identify the core neurobiological features of schizophrenia. For example, changes in dopaminergic systems are observed in animal models after manipulation of factors based on schizophrenia epidemiology50, 51, genetics78, pharmacology79 and related hypotheses80. These include changes in early dopamine specification factors50, 51, sensitivities to psychostimulants50,51,78, 80 and alterations in dopamine neurochemistry50,51,78, 79. Evidence of subcortical dopaminergic hyperactivity or sensitivity in animal models is proposed to represent the face validity (i.e., mimicking the phenomenology of schizophrenia) for psychosis in patients. The most commonly used behavioural assessments of positive symptoms in animal models include enhanced amphetamine-induced locomotion and deficits in prepulse inhibition (PPI)81. These tests are widely used because they are relatively simple to perform. However, we propose that given current knowledge of the neurobiology in schizophrenia, they have outlived their usefulness as measures of positive symptoms.

Amphetamine-induced locomotion

Amphetamine increases dopamine release in striatal brain regions of both humans38 and rats82. Amphetamine-related behaviours in rodents are also strongly linked to activity in striatal brain regions82, 83. Thus, an increased locomotor response to amphetamine (and other psychostimulants, which face similar criticisms) is considered a simple test to reflect the subcortical hyperdopaminergia underlying the psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Most animal models of schizophrenia report increased locomotor activation after psychostimulants78. However, the recent clinical evidence described above suggests that current assessments of animal models does not reflect contemporaneous knowledge of dopamine activity in those with schizophrenia.

The relative contribution of specific dopamine pathways to amphetamine-induced locomotion provides a good example of why a paradigm shift is required for research using animal models for positive symptoms in schizophrenia. For example, amphetamine-induced locomotion is largely driven by limbic dopamine release. Local administration of amphetamine84–87 or dopamine84,88, 89 into the nucleus accumbens induces locomotion. Furthermore, blocking dopamine signalling in the nucleus accumbens attenuates amphetamine-induced locomotion90. Specifically activating limbic dopamine projections using chemogenetic tools robustly increases locomotion, but activating associative dopamine projections does not91. Thus, there is an anatomical misalignment between the primary behavioural outcome deemed important for positive symptoms in animal models of schizophrenia (i.e, psychostimulant-induced locomotion driven by limbic dopamine), and clinical evidence in patients (hyperactive associative striatal dopamine). Furthermore, clinical studies directly comparing activity levels in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder suggest that hyperactivity may be a core feature of bipolar disorder rather than schizophrenia92.

One argument for amphetamine-induced locomotion is that it is predictive of antipsychotic efficacy, but this is merely a serendipitous side effect. Systemically administered amphetamine increases dopamine function in both the limbic striatum (locomotion) and associative striatum (positive symptoms). Systemically administered antipsychotics antagonise D2 receptors throughout the brain. Therefore, amphetamine-induced locomotion acts serendipitously to predict antipsychotic effectiveness via dopamine release in a parallel circuit (limbic vs. associative dopamine). Optimally, antipsychotics that diminish dopamine signalling preferentially in the associative, rather than the limbic, striatum need to be developed. Obviously, amphetamine-induced locomotion would not be predictive for the latter treatment options.

Prepulse Inhibition

One of the most consistently observed neurological impairments in schizophrenia is impaired sensorimotor gating in the form of decreased PPI93, 94. Deficits in PPI may reflect an inability to gate out irrelevant information. PPI deficits also respond to antipsychotics but are not specific to schizophrenia93, 94. Thus, PPI deficits do not represent a specific or diagnostic trait of schizophrenia. Intact cortical and striatal function are critical for PPI95 and, therefore, deficits in PPI also reflect an interface between positive and cognitive symptom groups81.

PPI is assessed almost identically in rodents and humans and, therefore, is one of the most widely studied deficits in schizophrenia. In rodents, the contribution of limbic dopamine projections to PPI are well-known95, though the associative striatum has also been implicated96, 97. Thus, PPI deficits clearly lack specificity concerning the hyperdopaminergia observed in schizophrenia. Therefore, when assessing rodent models, PPI impairments alone are insufficient for determining positive symptom phenotypes and their predictive validity suffers from the same criticism as that of amphetamine-induced locomotion (parallel blockade of limbic D2 receptors).

Can we objectively test positive symptom connectivity in rodents?

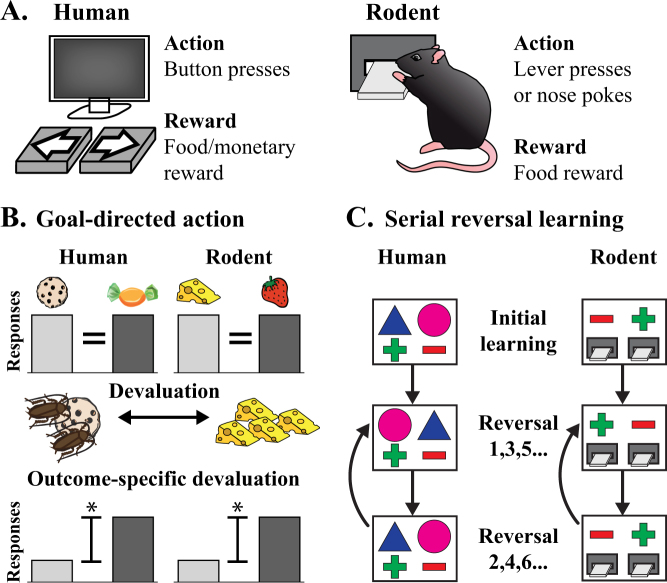

Clearly, alternative behavioural phenotypes in animal models, consistent with the underlying neuroanatomical/biological features of schizophrenia, need to be established. This does not invalidate our current rodent models; it just emphasises that, in light of the recent compelling PET evidence in patients, we need to review their relevance to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychosis, an extremely ‘human’ syndrome, will never be truly observable in rodents. However, we can, and should, aim to establish more translationally relevant tests for the underlying neurobiology of psychosis. Ultimately, we need better behavioural tests for positive symptoms in animal models that will lead to therapies efficacious for both positive and cognitive symptoms in patients. We contend that tests aimed at understanding associative striatal function are imperative. We propose that a combination of cognitive behavioural tasks, that can be tested similarly in humans and rodents (Fig. 4a), represents our best opportunity to assess positive symptom neurobiology in animal models. It is important to consider that neither task alone is a reliable indicator of positive symptom neurobiology (as these tasks assess cognitive function and outcomes are therefore relevant to cognitive symptoms); however, in combination they can help isolate associative striatal function.

Fig. 4. Comparisons for cognitive tests in humans and rodents.

Humans and rodents can both perform cognitive tasks that feature actions to obtain rewards (a) The primary differences in testing are that humans can receive monetary rewards whereas rodents tend to be given food rewards. Furthermore, rodents require more initial training to learn the action (i.e., lever pressing or nose poking). To test for goal-directed action (b) both humans and rodents are trained to associate two actions (left and right button/lever presses) with two separate food rewards. One of these rewards is then devalued through an aversive video (cockroaches on the food item) for humans or feeding to satiety in rodents. Healthy controls will demonstrate outcome-specific devaluation by biasing their response towards the food reward that was not devalued. Serial reversal learning (c) requires the subject to learn a simple discrimination between two choices of which one is associated with a reward. Once certain criteria are met, the contingencies are reversed so that the non-rewarded stimulus is now rewarded and the previously rewarded stimulus does not attain a reward. This is classified as the first reversal. Once the criteria are met for the new contingencies, the rewarding stimulus is switched again (back to the original pairings) for the second reversal. This switching back and forth continues until completion of the test

Goal-directed action: sensitivity to outcome devaluation

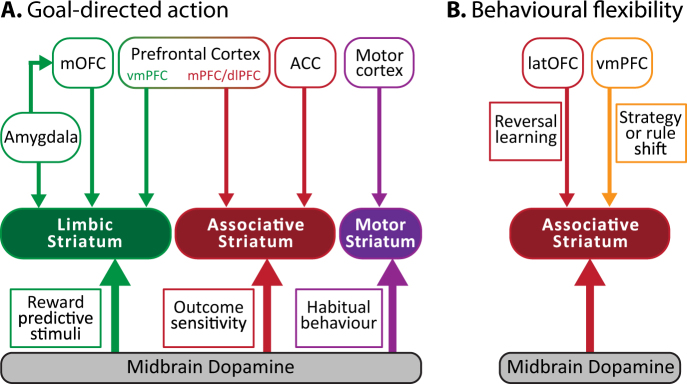

Goal-directed behaviour is critical for understanding the relationship between actions and their consequences in both humans and rodents. Moreover, goal-directed action heavily depends on the function of the associative striatum21,24, 98–100 and can be assessed using near identical behavioural paradigms in both humans101 and rodents102 (Fig. 4b). To test impairments in the learning of action-outcome associations in humans and rodents the sensitivity to outcome-specific devaluation can be determined. Outcome-specific devaluation is useful way of establishing that an action is goal-directed and that the correct action–outcome associations have been formed. In order to test this, after training to associate actions with specific outcomes (action–outcome association), one of the outcomes is devalued. After devaluation, when the subject is given the choice between the two action-outcome pairs, healthy controls respond more for the outcome that was not devalued. This demonstrates the ability to establish action-outcome associations correctly and adapt actions based on newly acquired information. The specific neurocircuitry involved in goal-directed behaviour is based on years of associative learning research103. Sensitivity to outcome devaluation is dependent on the PFC and associative striatum (Fig. 5a). Impairments in goal-directed action in schizophrenia have been associated with altered caudate function101 and disorganised thought104. Importantly, the insensitivity to outcome devaluation observed in persons with schizophrenia was not due to impairments in reward sensitivity after devaluation (i.e., limbic systems) but rather, reflected an inability to use this information to direct choice101.

Fig. 5. Behavioural tests to probe associative striatal function.

a The neurocircuitry involved in goal-directed action can be split into three primary circuits. The associative system (red), including the PFC and ACC, is required for the acquisition and expression of goal-directed action, which is sensitive to outcome devaluation. In contrast, the limbic system (green) is critical for the formation of associations between reward predictive stimuli and action. Habitual behaviours rely on the sensorimotor system (purple). b Behavioural flexibility involves OFC and PFC inputs to the associative striatum. The OFC is critical for reversal learning whereas the PFC is required when shifting to new rules or strategies. The associative striatum is the only common region required for goal-directed action that is sensitive to outcome devaluation and serial reversal learning. OFC orbitofrontal cortex, PFC prefrontal cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, vm ventromedial, m medial, dl dorsolateral, lat lateral

Behavioural flexibility: serial reversal learning

One limitation of outcome-specific devaluation is that it does not allow for the delineation of functional deficits in the PFC vs. associative striatum. Thus, pairing this task with another that relies on the associative striatum, but not the PFC, is required. The basal ganglia is also involved in flexible decision-making and specifically reversal learning (the ability to adapt when outcome contingencies are reversed) which can be tested similarly in humans and rodents (Fig. 4c). Extensive work in rodents, primates and humans have demonstrated that specific forms of behavioural flexibility are dependent on differing neurocircuitry69,105, 106(Fig. 5b). For example, the orbitofrontal cortex and associative striatum are critical for reversal learning when re-exposed to previous contingencies (e.g., serial reversal learning). In contrast, the PFC is critical for shifting from one rule or strategy to another (i.e., attentional set-shifting). Thus, deficits in serial reversal learning are particularly sensitive to orbitofrontal cortex and associative striatal dysfunction but not PFC dysfunction. Persons with schizophrenia exhibit deficits in both attentional set-shifting and reversal learning107. Deficits in reversal learning are independent of working memory deficits and have also been associated with disorganised thought108.

A circuit level approach to positive symptoms in animal models

Advances in behavioural neuroscience have helped to delineate specific circuits important for aspects of complex behaviour. Moreover, improvements in circuit isolation using techniques such as optogenetics109 or chemogenetics110 mean the field is at a point now where we can focus on particular brain regions and circuits. The proposed tasks, outcome-specific devaluation and serial reversal learning, provide a potential mechanism to focus on associative striatal function (Fig. 5). For example, an insensitivity to outcome devaluation and impaired serial reversal learning would be predicted if associative striatal function is compromised. In contrast, an insensitivity to outcome devaluation but maintained serial reversal learning would predict impairments in PFC function. The opposite would be true if orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction is present. Although this is far from perfect, an understanding of the extended connectivity from the associative striatum provides a starting point to probe animal models of schizophrenia to determine whether they demonstrate true associative striatal dysfunction rather than limbic dysfunction. Like psychosis, deficits in goal-directed behaviour103 and reversal learning107 are observed in a multitude of disorders other than schizophrenia, meaning that multiple tests assessing cognitive function and other circuitry will still be required to determine how useful one particular animal model will be to an individual psychiatric condition. This combination of tests, however, will allow for a more selective assessment of associative striatal function.

Challenging longstanding assumptions and moving forward

Clozapine, discovered in the 1960’s, remains the most effective antipsychotic medication, although its use is restricted due to its side effect profile111. This stagnation in drug development for schizophrenia highlights a key weakness in schizophrenia research; a lack of effective bi-directional translation between basic and clinical research. The fact that the current methods of testing for psychotic symptoms in rodents are now misaligned with recent clinical evidence indicates a need to advance how positive symptoms are examined in animal models. We have proposed a combination of behavioural tests in rodents that are sensitive to dysfunction at the primary site of dopaminergic neurobiology observed in schizophrenia. There will never be a perfect model for psychosis in rodents, but it is critical that we acknowledge the limitations of current methods so that an active dialogue is established.

It is also imperative that basic and clinical researchers maintain active collaborations to prevent the misinterpretation or mistranslation of animal studies. For example, based on the work in monkeys and rodents112–114, the results of D1 receptor agonists on working memory function in schizophrenia have been largely negative115–117. One contributing factor may have been that the preclinical studies tested delay-dependent working memory (i.e., how long a piece of information is kept in working memory), whereas the clinical studies tested a differing working memory construct, memory span capacity (i.e., how many items can be kept in working memory at one time). Other factors such as medication history118 may also interfere with the effectiveness of translation between preclinical and clinical studies. To improve translational schizophrenia research it is imperative that we build better avenues for communication between basic and clinical research teams to avoid the aforementioned issues.

Conclusion

Complex syndromes like schizophrenia require a constant reformulation and evolution of ideas and strategies that cannot be achieved by either basic or clinical research in isolation. Clinically, the point at which psychotic symptoms become apparent has dictated our primary diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, it has become evident that a range of complex symptoms emerge before this diagnostic time point. Clinical research must continue to elucidate the features associated with the development of psychosis and better inform a patient’s clinical trajectory throughout the course of schizophrenia. However, our current ability to model psychotic symptoms in animal models is at best questionable and based on historical presumptions rather than recent clinical evidence. Thus, it is imperative that basic research using animal models develops objective measures for the neurobiology underlying psychosis in schizophrenia. Understanding in detail the neurobiological processes that precede these behavioural abnormalities, an avenue of research that cannot be conducted in humans, now becomes a priority. It is only by a synthesis of such approaches that novel therapeutic targets and treatments will emerge.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Advance Queensland Research Fellowship (to J.P.K.), a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Practitioner Fellowship Grant (APP1105807 to J.G.S.), a NHMRC John Cade Fellowship (APP1056929 to J.J.M.) and a Niels Bohr Professorship from the Danish National Research Foundation (to J.J.M.).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McNally JM, McCarley RW. Gamma band oscillations: a key to understanding schizophrenia symptoms and neural circuit abnormalities. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2016;29:202–210. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laruelle M. Schizophrenia: from dopaminergic to glutamatergic interventions. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014;14:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aymard N, et al. Long-term pharmacoclinical follow-up in schizophrenic patients treated with risperidone - Plasma and red blood cell concentrations of risperidone and its 9-hydroxymetabolite and their relationship to whole blood serotonin and tryptophan, plasma homovanillic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, dihydroxyphenylethyleneglycol and clinical evaluations. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;26:975–988. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00218-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egerton A, Stone JM. The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia: neuroimaging and drug development. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012;13:1500–1512. doi: 10.2174/138920112800784961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS project for developing cognition-enhancing agents for schizophrenia. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2006;8:109–113. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.1/smarder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLisi LE. The significance of age of onset for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1992;18:209–215. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howes OD, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 2009;66:13–20. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kegeles LS, et al. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:231–239. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laruelle M, et al. Schizophrenia is associated with increased synaptic dopamine in associative rather than limbic regions of the striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:S196–S196. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CA, Watson DJ, Fone KC. Animal models of schizophrenia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;164:1162–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha S, Scott JG, Varghese D, McGrath JJ. The association between general psychological distress and delusional-like experiences: a large population-based study. Schizophr. Res. 2011;127:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurens KR, Cullen AE. Toward earlier identification and preventative intervention in schizophrenia: evidence from the London Child Health and Development Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015;51:475–491. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelleher I, et al. Neurocognitive performance of a community-based sample of young people at putative ultra high risk for psychosis: support for the processing speed hypothesis. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;18:9–25. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2012.682363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connell M, et al. Hallucinations in adolescents and risk for mental disorders and suicidal behavior in adulthood: prospective evidence from the MUSP birth cohort study. Schizophr. Res. 2016;176:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGrath JJ, et al. The bidirectional associatio ns between psychotic experiences and dsm-iv mental disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2016;173:997–1006. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15101293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH. Dopamine receptor binding predicts clinical and pharmacological potencies of antischizophrenic drugs. Science. 1976;192:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeman P, Lee T. Antipsychotic drugs: direct correlation between clinical potency and presynaptic action on dopamine neurons. Science. 1975;188:1217–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.1145194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howes OD, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:776–786. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kegeles LS, et al. Striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2/D3 receptors in schizophrenia evaluated with [18F]fallypride positron emission tomography. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liljeholm M, O’Doherty JP. Contributions of the striatum to learning, motivation, and performance: an associative account. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012;16:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joel D, Weiner I. The connections of the dopaminergic system with the striatum in rats and primates: An analysis with respect to the functional and compartmental organization of the striatum. Neuroscience. 2000;96:451–474. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilbronner SR, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Quirk GJ, Groenewegen HJ, Haber SN. Circuit-based corticostriatal homologies between rat and primate. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;80:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balleine BW, O’Doherty JP. Human and rodent homologies in action control: corticostriatal determinants of goal-directed and habitual action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:48–69. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2016;18:7–21. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/shaber. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angrist B, Vankammen DP. CNS stimulants as tools in the study of schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 1984;7:388–390. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(84)80062-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberman JA, Kane JM, Alvir J. Provocative tests with psychostimulant drugs in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 1987;91:415–433. doi: 10.1007/BF00216006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janowsky DS, Elyousef MK, Davis JM, Sekerke HJ. Provocation of Schizophrenic Symptoms by Intravenous Administration of Methylphenidate. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1973;28:185–191. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750320023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abi-Dargham A, et al. Increased baseline occupancy of D-2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abi-Dargham A, van de Giessen E, Slifstein M, Kegeles LS, Laruelle M. Baseline and Amphetamine-Stimulated Dopamine Activity Are Related in Drug-Naive Schizophrenic Subjects. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;65:1091–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breier A, et al. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: Evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Kegeles L, Innis R. Increased dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: Relationship to illness phases. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:56–72. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham P. Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: new evidence from brain imaging studies. J. Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:358–371. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abi-Dargham A, et al. Increased striatal dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: confirmation in a second cohort. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:761–767. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laruelle M, et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9235–9240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fusar-Poli P, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Striatal Presynaptic Dopamine in Schizophrenia, Part II: Meta-Analysis of F-18/C-11 -DOPA PET Studies. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39:33–42. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howes OD, et al. Midbrain dopamine function in schizophrenia and depression: a post-mortem and positron emission tomographic imaging study. Brain. 2013;136:3242–3251. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howes OD, Fusar-Poli P, Bloomfield M, Selvaraj S, McGuire P. From the prodrome to chronic schizophrenia: the neurobiology underlying psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairments. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18:459–465. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winton-Brown TT, Fusar-Poli P, Ungless MA, Howes OD. Dopaminergic basis of salience dysregulation in psychosis. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bloemen OJ, et al. Striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor binding following dopamine depletion in subjects at ultra high risk for psychosis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egerton A, et al. Presynaptic striatal dopamine dysfunction in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: findings in a second cohort. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fusar-Poli P, et al. Abnormal frontostriatal interactions in people with prodromal signs of psychosis A Multimodal Imaging Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:683–691. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fusar-Poli P, et al. Abnormal prefrontal activation directly related to pre-synaptic striatal dopamine dysfunction in people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:67–75. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howes O, et al. Progressive increase in striatal dopamine synthesis capacity as patients develop psychosis: a PET study. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:885–886. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howes OD, et al. Dopamine synthesis capacity before onset of psychosis: a prospective (18)F -DOPA PET imaging study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:1311–1317. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016;17:524–532. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone JM, et al. Altered relationship between hippocampal glutamate levels and striatal dopamine function in subjects at ultra high risk of psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connor WT, O’Shea SD. Clozapine and GABA transmission in schizophrenia disease models: establishing principles to guide treatments. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;150:47–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eyles D, Feldon J, Meyer U. Schizophrenia: do all roads lead to dopamine or is this where they start? Evidence from two epidemiologically informed developmental rodent models. Transl. Psychiatry. 2012;2:e81. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kesby JP, Cui X, Burne THJ, Eyles DW. Altered dopamine ontogeny in the developmentally vitamin D deficient rat and its relevance to schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;7:111. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demjaha A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in schizophrenia associated with elevated glutamate levels but normal dopamine function. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:E11–E13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCarthy-Jones S, et al. Occurrence and co-occurrence of hallucinations by modality in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amad A, et al. The multimodal connectivity of the hippocampal complex in auditory and visual hallucinations. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:184–191. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silbersweig DA, et al. A functional neuroanatomy of hallucinations in schizophrenia. Nature. 1995;378:176–179. doi: 10.1038/378176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behrendt RP. Contribution of hippocampal region CA3 to consciousness and schizophrenic hallucinations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010;34:1121–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larivière S, et al. Altered functional connectivity in brain networks underlying self-referential processing in delusions of reference in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2017;263:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braun CM, Dumont M, Duval J, Hamel-Hebert I, Godbout L. Brain modules of hallucination: an analysis of multiple patients with brain lesions. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28:432–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Howes OD, et al. Dopaminergic function in the psychosis spectrum: an F-18 -DOPA Imaging Study in healthy individuals with auditory hallucinations. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39:807–814. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMurtray A, et al. Acute Psychosis Associated with Subcortical Stroke: Comparison between Basal Ganglia and Mid-Brain Lesions. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2014;2014:428425. doi: 10.1155/2014/428425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng YC, Liu HC. Psychotic symptoms associated with left caudate infarction. Int. J. Gerontol. 2015;9:180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2015.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arzy S, Schurr R. “God has sent me to you”: right temporal epilepsy, left prefrontal psychosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;60:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poletti M, Sambataro F. The development of delusion revisited: a transdiagnostic framework. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1245–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Behrens TE, et al. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:750–757. doi: 10.1038/nn1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PCMP, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39:1129–1138. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrisberger F, et al. Alterations in the hippocampus and thalamus in individuals at high risk for psychosis. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:16033. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sommer IE, et al. The treatment of hallucinations in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2012;38:704–714. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Ghiglieri V, Di Filippo M. Direct and indirect pathways of basal ganglia: a critical reappraisal. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:1022–1030. doi: 10.1038/nn.3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Schouwenburg M, Aarts E, Cools R. Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive control: distinct roles for the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010;16:2026–2032. doi: 10.2174/138161210791293097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colder B. The basal ganglia select the expected sensory input used for predictive coding. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2015;9:119. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2015.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Redgrave P, Prescott TJ, Gurney K. The basal ganglia: a vertebrate solution to the selection problem? Neuroscience. 1999;89:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cazorla M, et al. Dopamine D2 receptors regulate the anatomical and functional balance of basal ganglia circuitry. Neuron. 2014;81:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ertugrul A, et al. The effect of clozapine on regional cerebral blood flow and brain metabolite ratios in schizophrenia: relationship with treatment response. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waltz, J. A. The neural underpinnings of cognitive flexibility and their disruption in psychotic illness. Neuroscience345, 203–217 (2017).. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Swartz MS, et al. What CATIE found: results from the schizophrenia trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008;59:500–506. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reichenberg A, et al. Static and dynamic cognitive deficits in childhood preceding adult schizophrenia: a 30-year study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167:160–169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitchell, K. J. et al.Schizophrenia: Evolution and synthesis in: (eds Silverstein S. M., Moghaddam B., & Wykes T.) 212–226 (MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2013) [PubMed]

- 78.O’Tuathaigh CM, Waddington JL. Closing the translational gap between mutant mouse models and the clinical reality of psychotic illness. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015;58:19–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.du Bois TM, et al. Altered dopamine receptor and dopamine transporter binding and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression following perinatal NMDA receptor blockade. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:1224–1231. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9571-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moore H, Jentsch JD, Ghajarnia M, Geyer MA, Grace AA. A neurobehavioral systems analysis of adult rats exposed to methylazoxymethanol acetate on E17: Implications for the neuropathology of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van den Buuse M. Modeling the positive symptoms of schizophrenia in genetically modified mice: pharmacology and methodology aspects. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:246–270. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharp T, Zetterstrom T, Ljungberg T, Ungerstedt U. A direct comparison of amphetamine-induced behaviours and regional brain dopamine release in the rat using intracerebral dialysis. Brain Res. 1987;401:322–330. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kelly PH, Seviour PW, Iversen SD. Amphetamine and apomorphine responses in the rat following 6-OHDA lesions of the nucleus accumbens septi and corpus striatum. Brain Res. 1975;94:507–522. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pijnenburg AJ, Honig WM, Van der Heyden JA, Van Rossum JM. Effects of chemical stimulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system upon locomotor activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1976;35:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.David HN, Sissaoui K, Abraini JH. Modulation of the locomotor responses induced by D-1-like and D-2-like dopamine receptor agonists and D-amphetamine by NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptor agonists and antagonists in the core of the rat nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kelley AE, Gauthier AM, Lang CG. Amphetamine microinjections into distinct striatal subregions cause dissociable effects on motor and ingestive behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 1989;35:27–39. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(89)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Staton DM, Solomon PR. Microinjections of D-amphetamine into the nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen differentially affect stereotypy and locomotion in the rat. Physiol. Psychol. 1984;12:159–162. doi: 10.3758/BF03332184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campbell A, Villavicencio AT, Yeghiayan SK, Balikian R, Baldessarini RJ. Mapping of locomotor behavioral arousal induced by microinjections of dopamine within nucleus accumbens septi of rat forebrain. Brain Res. 1997;771:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Swanson CJ, Heath S, Stratford TR, Kelley AE. Differential behavioral responses to dopaminergic stimulation of nucleus accumbens subregions in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1997;58:933–945. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pijnenburg AJJ, Honig WMM, Vanrossum JM. Inhibition of D-amphetamine-induced locomotor activity by injection of haloperidol into nucleus accumbens of rat. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;41:87–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00421062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boekhoudt L, et al. Chemogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area, but not substantia nigra, induces hyperactivity in rats. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:1784–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perry W, et al. Quantifying over-activity in bipolar and schizophrenia patients in a human open field paradigm. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Braff, D. L. Prepulse in: Behavioral Neurobiology of Schizophrenia and Its Treatment Vol. 4 (ed. Swerdlow N. R.) 349–371 (Springer-Verlag Berlin: Berlin, 2010)

- 94.Swerdlow NR, et al. Deficient prepulse inhibition in schizophrenia detected by the multi-site COGS. Schizophr. Res. 2014;152:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koch M. The neurobiology of startle. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999;59:107–128. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baldan Ramsey LC, Xu M, Wood N, Pittenger C. Lesions of the dorsomedial striatum disrupt prepulse inhibition. Neuroscience. 2011;180:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Swerdlow NR, Caine SB, Geyer MA. Regionally selective effects of intracerebral dopamine infusion on sensorimotor gating of the startle reflex in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02245306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Corbit LH, Janak PH. Posterior dorsomedial striatum is critical for both selective instrumental and Pavlovian reward learning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:1312–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hikosaka O, Kim HF, Yasuda M, Yamamoto S. Basal ganglia circuits for reward value-guided behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;37:289–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-013924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yin HH, Ostlund SB, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. The role of the dorsomedial striatum in instrumental conditioning. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morris RW, Quail S, Griffiths KR, Green MJ, Balleine BW. Corticostriatal control of goal-directed action is impaired in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Matamales M, et al. Aging-related dysfunction of striatal cholinergic interneurons produces conflict in action selection. Neuron. 2016;90:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Griffiths KR, Morris RW, Balleine BW. Translational studies of goal-directed action as a framework for classifying deficits across psychiatric disorders. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014;8:101. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bates AT, Kiehl KA, Laurens KR, Liddle PF. Error-related negativity and correct response negativity in schizophrenia. Clin. Neurophysiol.: Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1454–1463. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ragozzino ME. The contribution of the medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsomedial striatum to behavioral flexibility. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1121:355–375. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Izquierdo A, Jentsch JD. Reversal learning as a measure of impulsive and compulsive behavior in addictions. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219:607–620. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Functions of frontostriatal systems in cognition: comparative neuropsychopharmacological studies in rats, monkeys and humans. Biol. Psychol. 2006;73:19–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pantelis C, et al. Relationship of behavioural and symptomatic syndromes in schizophrenia to spatial working memory and attentional set-shifting ability. Psychol. Med. 2004;34:693–703. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cardozo Pinto D. F., Lammel S. Viral vector strategies for investigating midbrain dopamine circuits underlying motivated behaviors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. (in press) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Urban DJ, Roth BL. DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs): chemogenetic tools with therapeutic utility. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015;55:399–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;209:385–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Castner SA, Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Reversal of antipsychotic-induced working memory deficits by short-term dopamine D1 receptor stimulation. Science. 2000;287:2020–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Roberts BM, Seymour PA, Schmidt CJ, Williams GV, Castner SA. Amelioration of ketamine-induced working memory deficits by dopamine D1 receptor agonists. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:407–418. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1840-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zahrt J, Taylor JR, Mathew RG, Arnsten AF. Supranormal stimulation of D1 dopamine receptors in the rodent prefrontal cortex impairs spatial working memory performance. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8528–8535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08528.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Girgis RR, et al. A proof-of-concept, randomized controlled trial of DAR-0100A, a dopamine-1 receptor agonist, for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:428–435. doi: 10.1177/0269881116636120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.George MS, et al. A single 20 mg dose of dihydrexidine (DAR-0100), a full dopamine D1 agonist, is safe and tolerated in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2007;93:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rosell DR, et al. Effects of the D1 dopamine receptor agonist dihydrexidine (DAR-0100A) on working memory in schizotypal personality disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:446–453. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gill KM, Cook JM, Poe MM, Grace AA. Prior antipsychotic drug treatment prevents response to novel antipsychotic agent in the methylazoxymethanol acetate model of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40:341–350. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]