Abstract

The decline in the discovery and development of novel antibiotics has resulted in the emergence of bacteria that are resistant to almost all available antibiotics. Currently, polymyxin B and E (colistin) are being used as the last-line therapy against life-threatening infections, unfortunately resistance to polymyxins in both the community and hospital setting is becoming more common. Octapeptins are structurally related non-ribosomal lipopeptide antibiotics that do not exhibit cross-resistance with polymyxins and have a broader spectrum of activity that includes Gram-positive bacteria. This makes them a precious and finite resource for the development of new antibiotics against these problematic polymyxin-resistant Gram-negative pathogens, in particular Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. This review surveys the progress in understanding octapeptin chemistry, mechanisms of antibacterial activity and biosynthesis. With the lack of cross-resistance and their broad antibacterial activity, the octapeptins represent ideal candidates for the development of a new generation of polymyxin-like lipopeptide antibiotics targeting polymyxin-resistant ‘superbugs’.

Keywords: Octapeptin, polymyxin, lipopolysaccharide, lipid A, structure activity relationships, resistance, mechanism, pharmacology

1. Octapeptins, a forgotten antibiotic discovery

In recent times the world has seen the emergence of bacteria that are resistant to almost all available antibiotics.1, 2 Over the last 30 years only two novel antibiotic classes have been introduced into the clinic (linezolid and daptomycin), illustrating that the golden era of antibiotic discovery is well and truly over.3, 4 Many pharmaceutical companies have lost interest in producing new antibiotics, preferring to focus on the development of more profitable products for the treatment of chronic conditions and lifestyle issues. Thus, there has been a decline in the discovery and development of novel antibiotics, and as a result we have seen the increasing global emergence of extremely resistant (XDR) ‘superbugs’, a dire situation has been dubbed the ‘perfect storm’.3, 4 The World Health Organization identifies antimicrobial resistance as one of the greatest threats to human health.2, 5, 6

In the 1970s the therapeutic use of polymyxins declined due to their nephrotoxicity as well as introduction of alternative antibiotics such as the β-lactams that were considered safer than polymyxins at that time.7–9 However, the exhaustive use of the β-lactam antibiotics has led to wide-spread resistance, leaving only very limited therapeutic options available to clinicians.10–13 Polymyxin B and colistin are now being increasingly used, especially in critically-ill patients as last-line therapy.2–7 Resistance to polymyxins can rapidly emerge in vitro to P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii and K. pneumonia.2–7 Moreover, polymyxin resistance in community and nosocomial acquired infections is being increasingly reported and even more worrying is the emergence and spread of MCR-1 plasmid borne polymyxin-resistance.14 Unfortunately polymyxin resistance indicates a total lack of treatment options for problematic Gram-negative infections. Therefore, there is an urgent unmet medical need to develop new and safer lipopeptide antibiotics. The problematic Gram-positive Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus together with XDR Gram-negative bacteria P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, K. pneumoniae, and Enterobacter species, are the 6 top-priority dangerous ESKAPE ‘superbugs’ identified by Infectious Diseases Society of America as requiring the most urgent attention for discovery of novel antibiotics.8

The octapeptins are a family of naturally occurring cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics with broad antimicrobial spectrum against polymyxin-resistant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The approaching ‘perfect storm’ of bacteria that are resistant to all available antibiotics combined with the dry antibiotic pipeline means that that the time has come to revisit these ‘forgotten’ antibiotics with ‘new potential’. Although octapeptins were discovered over 40 years ago there is very little coverage of them in the literature and they were discovered before the establishment of contemporary drug development processes. Consequently, a lot of work remains to be done as their mode of action, pharmacology and toxicity remains, largely uncharacterized. This review surveys the literature knowledge-base for the octapeptins in relation to the clinically used polymyxin lipopeptides. An emphasis is placed on the development of octapeptins as a potential new generation of lipopeptide antibiotics for targeting polymyxin-resistant ‘superbugs’.

2. Chemical structures and nomenclature

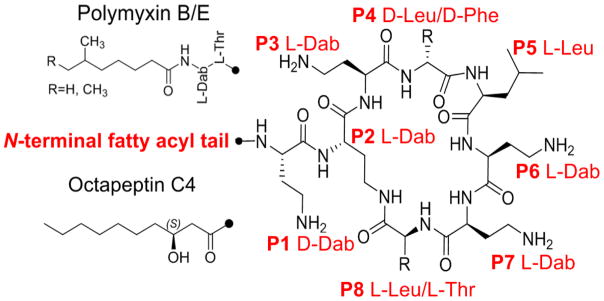

The octapeptins were originally isolated, from the soil bacteria Bacillus circulans.9–14 Like the polymyxins they are produced by bacteria as mixtures of structurally related peptides. To date 19 octapeptins have been isolated and characterized (Table 1). The octapeptins scaffold consists of a cyclic heptapeptide ring linked to a D-amino acid at position 1 and an N-terminal β-hydroxyl fatty acyl tail (Figure 1). The N-terminal hydroxyl-fatty acyl group varies in length from C8 to C10 across the different octapeptins and can be non-branched (3-(R)-hydroxydecanoic acid) or branched ((R)-3-hydroxy-(S)-6-methyloctanoyl, 3-(R)-hydroxy-8-methyl-nonanoic acid, 3-(R)-hydroxy-8(S)-methyldecanoic acid) fatty acyl chain. They contain 3–4 L-α,γ-diaminobutyric acid (Dab) residues; which make the octapeptin molecule a polycation at pH 7.4. Structural variation amongst the octapeptins is conserved to the structure of the N-terminal of the β-hydroxy-fatty acid and the structure and/or chirality of the amino acids presented at positions 1, 4 and 5 (Table 1). Before the nomenclature ‘octapeptin’ was coined, these lipopeptides were originally given the company codes Bu-2470, EM49, 333-25 and Bu-1880 or known as circulins/battacins by the teams from the pharmaceutical firms Squibb and Bristol-Myers.11–14 Eventually a consensus on nomenclature was reached and the octapeptins were alphabetically designated into four groups; Octapeptins A-D based on the combination of amino acid residues presented at positions 1, 4 and 5 of their scaffold. (Table 1).10 Further designation was given to individual lipopeptides within these groups by placing a subscripted number after the designated letter of the group. Individual lipopeptides within a group are differentiated by the structure of their N-terminal fatty acyl group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Octapeptin structures and nomenclature.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octapeptin | Synonym | N-terminal Fatty acyl group | Pos 1 | Pos 4 | Pos 5 |

| A1 | EM49β | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-8-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| A2 | EM49α1 | (R)-3-Hydroxy-8-methylnonanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| A3 | EM49α2 | (R)-3-Hydroxydecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| A4 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxy-9-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| B1 | EM49δ | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-8-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Phe |

| B2 | EM49γ1 | (R)-3-Hydroxy-8-methylnonanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Phe |

| B3 | EM49γ2 | (R)-3-Hydroxydecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Phe |

| B4 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxy-9-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Leu | L-Phe |

| B5 | Battacin | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-6-methyloctanoyl | D-Dab | L-Leu | D-Phe |

| C0 | Bu-2470 A | H | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| C1 | Bu-2470, 333-25, | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-6-methyloctanoyl | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| C2 | Bu-2470 B1 | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-8-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| C3 | Bu-2470 B2α | (R)-3-Hydroxy-9-methyldecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| C4 | Bu-2470 B2β | (R)-3-Hydroxydecanoyl | D-Dab | D-Phe | L-Leu |

| D1 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-8-methyldecanoyl | D-Ser | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| D2 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxy-8-methylnonanoyl | D-Ser | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| D3 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxydecanoyl | D-Ser | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| D4 | - | (R)-3-Hydroxy-9-methyldecanoyl | D-Ser | D-Leu | L-Leu |

| - | Bu-1880* | (R)-3-Hydroxy-(S)-8-methyldecanoyl | D/L-Dab | D/L-Leu, D/L-Phe | |

Bu-1880 has the same N-terminal fatty-acyl group and amino acid composition as octapeptin B1 and C2. However the exact positions and stereochemistry of each amino acid is yet to be determined

Dab = diaminobutyric acid, Phe = phenylalanine; Leu = leucine; Ser = serine.

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of octapeptin C4 and polymyxin B1. Leu: leucine; Phe: phenylalanine; Dab: α,γ-diaminobutyric acid.

3. Octapeptins and polymyxins: chalk and cheese or peas in a pod?

In terms of similarities, polymyxins and octapeptins are both cyclic lipopeptides characterized by a high proportion of positive Dab residues in their sequence. Both polymyxins and octapeptins have a cyclic heptapeptide core linked to an N-terminal fatty acyl chain (Figure 1). Both octapeptin and polymyxins possess a hydrophobic motif in their cyclic heptapeptide ring (positions 4 and 5 for octapeptins; positions 6 and 7 for polymyxins).15 However there are several notable structural differences between the polymyxins and the octapeptins The exo-cyclic side chain of the octapeptins is invariably a single D-amino acid (D-Dab or D-Ser), whereas in the polymyxins the side chain consists of a tri-peptide segment, with all amino acids residues usually of the L-configuration; except for polymxyins A, D and P, which display either D-Dab or D-Ser at position 3 (position 1 in the octapeptins). In the octapeptin cyclic hepta-peptide ring a hydrophobic L-Leu residue is found at position 8, whereas the equivalent residue in the polymyxins (position 10 in polymyxins) is a hydrophilic L-Thr. The length of the N-terminal fatty acyl chains also differ, with the octapeptins displaying longer C9 or C10 β-hydroxyl fatty acyl chains as opposed to the shorter C7 or C8 fatty acyl chains of polymyxins which also lack a β-hydroxyl group (polymyxin B1 and colistin A: 6-(S)-methyloctanoyl; polymyxin B2 and colistin B: 6-methylheptanonyl).16–25 Notably, polymyxin B6 is unique in that it’s the only polymyxin that has a fatty acyl chain containing a 3-hydroxy group.15 Octapeptins and polymyxins also differ in their charges as a result of the reduced number Dab residues due to the truncated linear segment; octapeptins possess 3–4 positive charges, whereas the polymyxins possess 4–5 positive charges. All of these structural differences increase the overall hydrophobicity of the octapeptins relative to the polymyxins. Furthermore in the octapeptins the chirality of the amino acid residues found at positions 4 and 5 of the cyclic hepta-peptide ring (positions 6 and 7 in the polymyxins) can vary between the different octapeptin groups where as in the polymyxins the chirality is conserved across the different groups.

4. Antibacterial activity

Fundamentally, the octapeptin molecule can be considered as being a truncated polymyxin molecule, albeit, this compact package packs a powerful punch with superior activity against polymyxin-resistant pathogens and Gram-positive bacteria (Table 2). Not unlike the polymyxins the octapeptins are outer membrane (OM) active antibiotics with biocidal activity against Gram-negative bacteria.14 However, unlike the polymyxins which have a narrow spectrum of activity solely against Gram-negative bacteria, octapeptins exhibit a broader spectrum of activity that also includes Gram-positives, yeast, filamentous fungi and protozoa (Table 2).16, 17, 26–31 Most importantly, octapeptins do not display cross-resistance with polymyxins against Gram-negative bacteria; this is potentially owing to a unique mode of action. Interestingly, the octapeptins generally display reduced activity against polymxyin-susceptible Gram-negative isolates.16, 17, 26–30 Notably, neither the polymyxins nor octapeptins are active in vitro against Serratia marcescens and Proteus spp., presumably due to the unique lipid A structures of these species.27, 32–34 The addition of human serum (25, 50 or 75%) does not impact the in vitro antibacterial activity of octapeptins.27, 34 Octapeptins have also been shown to possess potent antipseudomonal biofilm activity.35, 36

Table 2.

Reported MICs for octapeptins.

| Octapeptin | Synonym | Isolate | MIC (mg/L) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | EM49β | Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC8329 | 0.8 | 17 | |

| Escherichia coli SC8294 | 0.6 | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 6.3 | ||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 0.8 | ||||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 9.4 | ||||

|

| |||||

| A2 | EM49α1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC8329 | 0.8 | 17 | |

| Escherichia coli SC8294 | 0.6 | ||||

|

|

|||||

| A3 | EM49α2 | Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 12.5 | ||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 1.6 | ||||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 9.4 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Octapeptin A (EM49) component mixture |

Octapeptin A (EM49) hydrochloride component mixture MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

16,17,18 | ||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC8329 | 0.9 | 0.64 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC 8327 | <0.4 | <0. 4 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC 8754 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC 8822 | 1.6 | 0.39 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC 9108 | 0.4 | 1.2 | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli ATCC10536 | 0.78 | 0.05 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC2927 | 0.8 | 0.05 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC8294 | 0.47 | 0.55 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC8517 | 0.25 | 0.19 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC8518 | ≤ 0.78 | ≤ 0.78 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC8599 | 2.3 | 0.8 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC8600 | 0.13 | >50 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC9251 | 1.65 | 1.17 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC9252 | 0.3 | 100 | |||

| Escherichia coli SC9253 | <0.1 | >200 | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae SC 8411 | 0.78 | 37.5 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae SC 8495 | 1.6 | 9.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Serratia marcescens SC 1468 | >100 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Enterobacter cloacae SC 8405 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |||

| Enterobacter cloacae SC 8415 | 1.8 | 0.8 | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella schottmuelleri SC 3850 | 0.8 | 0.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhosa NIH #779 | 0.1 | 0.05 | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus rettgeri SC 8217 | 100 | >200 | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus mirabilis SC 3855 | 150 | >200 | |||

|

| |||||

| Bordetella bronchiseptica ATCC 19395 | 0.16 | 0.21 | |||

|

| |||||

| Vibrio parahemolyticus ATCC 17802 | 0.78 | <0.09 | |||

|

| |||||

| Herella sp. SC 8333 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Hemophilus suis ATCC 19417 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |||

|

| |||||

| Hemophilus influenzae ATCC 9333 | 1.0 | 0.06 | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 0.6 | 2.1 | |||

| Streptococcus pyogenes SC3862 | 0.6 | 2.1 | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus lysodeikticus SC 2529 | 1.2 | 9.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus faecalis ATCC10541 | 6.3 | 50 | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 5.5 | 25 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus 1276 | 5.5 | 25 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2406 | 9.4 | >50 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2399 | 12.5 | 150 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2400 | 12.5 | 75 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2961 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2664 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2661 | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC2957 | 18.7 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus SC3538 | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC12228 | 0.6 | 1.8 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis SC9052 | 3.1 | 18.7 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis SC4056 | 0.6 | 1.3 | |||

|

| |||||

| Diplococcus pneumoniae ATCC 6303 | 2.4 | 25 | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | 0.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus cereus 17B | 18.7 | >200 | |||

| Bacillus cereus Philpot#1 | 18.7 | >200 | |||

| Bacillus cereus Philpot#2 | 18.7 | >200 | |||

| Bacillus cereus 69B | 37.5 | >200 | |||

|

| |||||

| Corynebacterium minutissimum ATCC23346 | 0.37 | 0.78 | |||

| Corynebacterium minutissimum ATCC23349 | 0.5 | 1.6 | |||

|

| |||||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 9.4 | 66.7 | |||

|

| |||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae SC 1600 | 2.4 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Aspergillus niger SC 2528 | 50 | >200 | |||

|

| |||||

| Microsporum canis SC 3767 | 6.3 | 25 | |||

|

| |||||

| Microsporum audouini SC 5282 | 6.3 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes SC2637 | 6.3 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Trichomonas vaginalis SC8560 | 18.7 | 75 | |||

|

| |||||

| Trichomonas foetus SC 9644 | 37.5 | 37.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| A4 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| Isolate | MIC (mg/L) | ||||

|

|

|||||

| B1 | EM49δ | Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC8329 | 1.2 | 17 | |

| Escherichia coli SC8294 | 0.4 | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 2.4 | ||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 0.4 | ||||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 4.7 | ||||

|

| |||||

| B2 | EM49γ1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa SC8329 | 0.4 | 17 | |

| Escherichia coli SC8294 | 0.6 | ||||

|

|

|||||

| B3 | EM49γ2 | Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 3.1 | ||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 0.4 | ||||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 6.3 | ||||

|

| |||||

| B4 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| B5 | Battacin |

Octapeptin B5 (Battacin) hydrochloride MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

38 | |

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5215 | 2–4 | 2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5313 | 4 | 1–2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5585 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5298 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5510 | 4 | 2 | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 35318 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Escherichia coli 5237 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Escherichia coli 5353 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Escherichia coli 5364 | 4 | 0.5–1 | |||

| Escherichia coli 5539 | 4 | 0.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii 5064 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Acinetobacter baumannii 5520 | 8–16 | 1 | |||

| Acinetobacter baumannii 5383 | 8–16 | 1 | |||

| Acinetobacter baumannii 5349 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Acinetobacter baumannii 5075 | 8 | 1 | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumonia 5405 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumonia 5147 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumonia 5614 | 8 | 1 | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 | 64–128 | 100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | 64–128 | 100 | |||

|

| |||||

| C0 | Bu-2470 A | Octapeptin C0 (Bu-2470 A) hydrochloride MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

34 | |

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus 209P | >100 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus faeealis B402-3 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus luteus #1001 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus flavus D-12 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus anthracis IID-115 | 100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis PCI 219 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Escherichia coli Juhl | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella enteritidis #4432 | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhosa A9498 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella dysenteriae D-163 | 100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella sonnei Yale | 25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa D 15 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15150 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15194 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa GN4925 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A21428 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas melanogenum | 1.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-15 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-66 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida KUH-11 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20620 | 1.6 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21384 | 0.4 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21550 | 0.8 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-36 | 0.40 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-81 | 0.4 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae D-11 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Enterobacter cloacae A9654 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus mirabilis A9554 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus vulgalis A9526 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus rnorranii A9553 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| C1 | Bu-2470, 333-25, | Octapeptin C1 hydrochloride MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

29 | |

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ JC-2 | 25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes C203 | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae type I | >50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhimurium | 3.13 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus FDA209P | 50 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis PCI 219 | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus anthracis | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| C2 | Bu-2470 B1 | Octapeptin C2 (Bu-2470 B1) hydrochloride MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

34 | |

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus 209P | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus faeealis B402-3 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus luteus #1001 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus flavus D-12 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus anthracis IID-115 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis PCI 219 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Escherichia coli Juhl | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella enteritidis #4432 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhosa A9498 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella dysenteriae D-163 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella sonnei Yale | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa D 15 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15150 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15194 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa GN4925 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A21428 | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas melanogenum | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-15 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-66 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida KUH-11 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20620 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21384 | 1.6 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21550 | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-36 | 0.8 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-81 | 1.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae D-11 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Enterobacter cloacae A9654 | 25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus mirabilis A9554 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus vulgalis A9526 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus rnorranii A9553 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| C3 | Bu-2470 B2α | Octapeptin C3 (Bu-2470 B2) hydrochloride MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

34 | |

|

| |||||

| C4 | Bu-2470 B2β | ||||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus 209P | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Streptococcus faeealis B402-3 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus luteus #1001 | 1.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus flavus D-12 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus anthracis IID-115 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis PCI 219 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Escherichia coli Juhl | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella enteritidis #4432 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhosa A9498 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella dysenteriae D-163 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella sonnei Yale | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa D 15 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15150 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A15194 | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa GN4925 | 12.5 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A21428 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas melanogenum | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-15 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida AKH-66 | 3.1 | nd | |||

| Pseudomonas putida KUH-11 | 6.3 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20620 | 6.3 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21384 | 0.8 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A21550 | 1.6 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-36 | 1.6 | nd | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia AKH-81 | 1.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | 1.6 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae D-11 | 3.1 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Enterobacter cloacae A9654 | 25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus mirabilis A9554 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus vulgalis A9526 | 100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus rnorranii A9553 | >100 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| D1 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| D2 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| D3 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| D4 | nd | ||||

|

| |||||

| Octapeptin D component mixture | - |

Octapeptin D hydrochloride component mixture MIC (mg/L) |

Polymyxin B sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

24 | |

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ JC-2 | 6.25 | nd | |||

| Escherichia coli EC-14 | 12.5 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus 209P JC-1 | 50 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | 50 | nd | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermis TB-548 | 25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhimurium | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella sonnei | 3.13 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus subtilis PCI 219 | 6.25 | nd | |||

|

| |||||

| Bu-1880 |

Bu-1880 hydrochloride component mixture MIC (mg/L) |

Colistin sulfate MIC (mg/L) |

31 | ||

|

| |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa D15 | 6.3 | 3.1 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A9923 | 12.5 | 6.3 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa A9930 | 3.1 | 0.8 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa D113 | 12.5 | 6.3 | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa Yale | 6.3 | 1.6 | |||

|

| |||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20620 | 3.1 | 3.1 | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20355 | 6.3 | 1.6 | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20358 | 12.5 | 3.1 | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia A20368 | 100 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Escherichia coli NIHJ | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Escherichia coli Juhl | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Escherichia coli A20363 | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Escherichia coli K12 | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Klebsiella pneumonia D11 | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumonia A9678 | 3.1 | 0.8 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumonia A9977 | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumonia A20680 | 12.5 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Serratia marcescens A20019 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Serratia marcescens A20335 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Serratia marcescens A20442 | >100 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus Russell | 6.3 | 50 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus Smith | 6.3 | 50 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermis No.193 | 6.3 | 50 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermis BX-1633 | 6.3 | 25 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermis Terajima | 3.1 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Sarcina lutea PCI 1001 | 12.5 | 50 | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella typhosa Yale | 3.1 | 0.8 | |||

| Salmonella typhosa NIHJ | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella paratyphi A | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Salmonella enterididis A9351 | 3.1 | 0.8 | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella flexneri A9634 | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella dysenteriae | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Shigella sonnei Yale | 3.1 | 0.4 | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus vulgaris ATCC 9920 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Proteus vulgaris A9436 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Proteus vulgaris A9699 | 6.3 | 12.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Proteus morganii A9553 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Proteus morganii A20454 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Proteus morganii A20455 | >100 | >100 | |||

| Proteus morganii A9900 | 6.3 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Micrococcus flavus | 3.1 | 6.3 | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus mycoides | 25 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus cereus ATCC 10702 | 6.3 | >100 | |||

|

| |||||

| Bacillus anthracis No.115 | 6.3 | >100 | |||

Encouragingly, attempts to develop resistance to octapeptins in vitro were unsuccessful when sub-culturing of Escherichia coli, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus through ten successive transfers in the presence of octapeptin A (EM49).37 However, an inoculum effect was evident against E. coli, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, as octapeptins were less active at higher inoculums sizes.27, 34 In vivo experiments using a mouse blood infection model showed that the octapeptin A, when administered subcutaneously at 18.7 mg/kg and 110–130 mg/kg, protected mice from E. coli and Streptococcus pyogenes, respectively.37 The octapeptin A was inactive following oral administration.37 A 0.5% cream based formulation of the octapeptin A was also demonstrated to be effective in a P. aeruginosa wound infection model.37 An in vivo study by the Bristol-Myers Company using an interperitoneal mouse infection model showed that octapeptins C0 (Bu-2470 A), C2 (Bu-2470B1) and C3/C4B2 protected mice from lethal challenge by E. coli, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae at intramuscular doses of 7.6–25 mg/kg octapeptin C0, 43–100 mg/kg (octapeptin C2) and 22 mg/kg (octapeptin C3; octapeptin C3 was inactive against E.coli and K. pneumoniae. Notably, octapetin C0, which is des-fatty acyl octapeptin (i.e has the N-terminal β-hydroxyl fatty acyl removed) was more active in vivo than in vitro compared to octapeptin C2 and octapetin C3B2 which have an intact β-hydroxyl decanoyl fatty acyl terminus.27, 34 This finding would suggest that the N-terminal β-hydroxyl fatty acyl can impact the pharmacokinetics of octapeptins, possibly by increasing the plasma protein binding. Another in vivo study from the Bristol-Myers Company also using the same interperitoneal mouse infection model showed that octapeptin Bu-1880 protected mice from a lethal challenge of E. coli, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus at subcutaneous doses of 165, 100 and 80 mg/kg, respectively.31 The study employed colistin as the comparator, which showed superior protection against E. coli (3.4 mg/kg), P. aeruginosa (15 mg/kg), but not surprisingly was inactive against S. aureus.31 A more recent in vivo study with octapeptin B5 dosed intravenously at 4 mg/kg provided 90 and 100% protection of mice challenged with lethal doses of E.coli ATCC 35318 and E. coli 5539, respectively.38

5. Mechanism of action

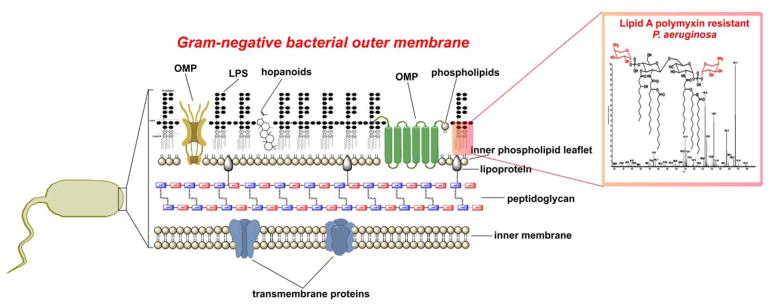

In light of the fact that there is limited information on the mode of action of octapeptins; and given their structural similarities with the polymyxins, it is pertinent to mention our current understanding of the mode of action of polymyxins. Polymyxins are believed to exert their primary antimicrobial mode of action by permeabilizing the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane via a direct interaction with the lipid A component of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Figure 2). Not unlike the octapeptins, the polymyxins are amphipathic in nature due to a hydrophobic N-terminal fatty acyl chain and the polar and cationic residues that constitute their structure. The disruptive effect of polymyxins on the outer membrane is thought to involve a two stage interaction mechanism with the lipid A component of LPS. In stage one, it is purported that the cationic side-chains of the 5 Dab residues on the polymyxin molecule electrostatically bind to the anionic phosphate groups on the lipid A core; thereby displacing the divalent cations that normally bridge adjacent lipid A molecules and serve to maintain membrane integrity.39–44 Not surprisingly, the most common resistance mechanism against polymyxins that Gram-negative bacteria employ is to modify their lipid A phosphate groups with positively charged groups such as ethanolamine or 4′-aminoarabinose, which acts to abolish the initial electrostatic interaction.45–50 This initial electrostatic stabilizing interaction allows the N-terminal fatty acyl chain of the polymyxin molecule to insert into the hydrocarbon layer of the lipid A molecules. Evidence in support of this mechanism is the observation that des-fatty acyl polymyxin nona-peptide (which lacks the N-terminal fatty acyl chain through enzymatic removal) does not have any bactericidal activity and is only bacterisostatic.51,52 Intriguingly, the same cannot be said for des-fatty acyl octapeptins, this topic is discussed further in the following SAR section. This suggests that it is a combination of the stage one electrostatic and stage two hydrophobic interactions that are crucial for the mode of action of polymyxins. Subsequent events remain unclear, however, a ‘self-promoted’ up-take mechanism is believed to produce disruption of the outer membrane structure, and gives the lipopeptide access to the cytoplasmic membrane.40–44 An early mechanistic 32P NMR study by Stephen Fesik at Abbott Labs revealed that octapeptins have the ability to bind to lipid A, particularly to the ethanolamine or 4′-aminoarabinose modified lipid structures seen in polymyxin resistant strains.53 This finding suggests that unlike polymxyins that primarily target lipid A and show poor affinity for phospholipids, the octapeptins retain the ability to avidly bind both of these core lipids; which could help explain their extended spectrum of activity against Gram-positives, that lack LPS in their outer membrane.23 Notably, similar to the polymyxins, octapeptins have been shown to disrupt the normal electrostatic interactions between divalent cations and lipid A that stabilize the outer membrane, this mechanism is supported by the specific protection of Gram-negatives against octapeptins afforded by Mg2+ and Ca2+.23, 38

Figure 2.

Architecture of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane.

What is known about the primary mode of action of octapeptins is that they bind to bacterial phospholipids and perturb the outer membrane structure, which helps explain their broad activity.30 Since octapeptins are amphipathic in character, at first glance it may be assumed that their disruptive influence on the bacterial outer membrane can be attributed to an activity akin to that of a simple cationic detergent. However, this is not the case as octapeptins exhibit bactericidal activity at much lower concentrations than simple cationic detergents and moreover, they display dose-dependent activity.16–19 Furthermore, minor structural modifications to the octapeptin core scaffold produce significant changes in their bactericidal activity.30, 54 Taken together, these findings highlight that there are specific interactions between the octapeptin molecule and the bacterial outer membrane that are at play. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy revealed that E. coli cells treated with octapeptin A caused the formation of numerous protrusions or blebs extending from the outer membrane of the cells.23 The composition of the blebs was shown to be outer membrane fragments.18, 23, 30 Furthermore it was shown that octapeptin treatment rapidly stimulated the release of membrane vesicles from the cells into the surrounding media, further indicating this was not the result of a secondary event.18, 30 Notably, a similar blebbing effect was observed with Gram-negative bacterial cells treated with polymyxin B and colistin.55 The cytoplasmic membrane permeabilizing effect of octapeptins has also been demonstrated by their ability to produce potassium release, proton leakage and an enhanced uptake of fluorescent membrane probes.23, 30, 35, 38 A recent report also showed octapeptin B5 has a depolarizing effect on the cytoplasmic membrane of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 cells, albeit, the effect somewhat weaker than that of polymxyin B.38 So it follows, we can conclude the ability of octapeptins to disrupt the other membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is somewhat akin to that of the polymyxins. The characterization of octapeptin interactions with bacterial membranes using spin-labeled octapeptin probes suggested that the β-hydroxyl fatty acyl chain of the octapeptin inserts into the hydrocarbon domain of lipid bilayers.56 Furthermore, spectral analysis of the spin-labeled octapeptin showed the β-hydroxyl fatty acyl chain interacts with the position 4 and 5 hydrophobic motif (D-Leu/D-Phe – P5 L-Leu) in the solution configuration; suggesting the octapeptin structure forms a hydrophobic triad that penetrates the bacterial membrane.56

In terms of a secondary mode of action, the octapeptins appear to interfere with a range of biochemical processes in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria such as respiration, selective membrane ion transport, ATP pool size and miscellaneous inner membrane enzyme-catalyzed activities.22, 30, 57 However, it remains unknown which of these secondary effects result from the aforementioned primary outer membrane lesions.30 Coincidently, our group demonstrated that a secondary mode of action of polymyxin B and colistin against Gram-negatives involves inhibition of a key bacterial respiratory chain inner membrane enzyme, NADH-quinone oxidoreductase.58

Overall, although octapeptins appear to have mechanistic similarities with polymxyins, their broad spectrum of activity and ability to avidly bind phospholipids perhaps attests to a unique mode of action

6. Structure Activity Relationships

To date most of the available SAR data for octapeptins has focused around the N-terminus.27, 34–36 The early work from the Bristol-Myers Company showed that des-fatty acyl octapeptin C0 lost all in vitro antibacterial activity against Gram-positives, but retained appreciable activity against Gram-negatives species.27, 34 Interestingly, the des-fatty acyl octapeptin C0 showed superior in vivo activity against Gram-negatives than its counterparts octapeptins C2 and C3 which are contain an N-terminal β-hydroxyl fatty-acyl groups.27, 34 Similarly, a more recent study reported that a synthetic des-fatty acyl octapeptin B5 retained comparable in vitro antipseudomonal activity as its fatty acylated counterpart, albeit, Gram-positive activity against S. aureus was once again abolished.35 The substitution of the β-hydroxyl fatty acyl with a series of C2 to C18 straight chain fatty acids revealed that the ideal N-terminal chain length for octapeptin activity against E. coli was C8 to C10, whereas the ideal chain length for activity against Bacillus subtilis was C12 to C16.56 The substitution of the N-terminus of octapeptin B5 with a C6 4-methylhexanoyl or Fmoc group did not impact its activity against Gram-negatives, however, the Fmoc substituted analogue showed a marked improvement in activity against Gram-positives.35 In contrast the substitution of the N-terminus of octapeptin B5 with a C8 geranyl (3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-yl acetate) or C14 myristyl chain abolished all antibacterial activity.35 Collectively these results suggest that the ideal chain length for antibacterial activity is in the range of C8 to C10, hydrophobicity at the N-terminus is also critical for activity against Gram-positives and the β-hydroxy group on the N-terminal fatty acyl is dispensable.

As covered in the preceding mode of action discussions the 5 cationic Dab residues are crucial for the antibacterial mode of action of the polymxyins.15 Not surprisingly, the cationic charge and exact side-chain length of the 4 Dab residues in the octapeptin sequence are also critical, as substitution with Ala or Lys residues leads to a marked decrease in antibacterial activity.35 More specifically, Ala screening studies revealed that the Dab residues at positions 1,3 and 6 are absolutely critical, whereas those at positions 2 and 7 are less important for antibacterial activity.35

The indispensability of the D-Phe/D-Leu–Leu hydrophobic motif at positions 6 and 7 for the antibacterial activity of the polymyxins is well known.15 Similarly, Ala scanning studies with octapeptin B5 showed that the corresponding motif at positions 4 and 5 of the octapeptin scaffold is also indispensible.35 Notably, the same study showed that Ala substitution of the invariable position 8 Leu of octapeptins (position 10 Thr in polymxyins) does not markedly impact antibacterial activity, suggesting this position is a good target for regio-selective modification.35 The position 4 D-Phe/D-Leu and position 5 L-Phe/L-Leu variations seen across the naturally occurring octapeptins do not appear to noticeably impact antibacterial activity.20, 30, 54, 59 The recent discovery of octapeptin B5 which has D-Phe at position 5 instead of L-Leu is fascinating as this is the first example of a polymxyin-like lipopeptide with the order of the D-Phe/D-Leu - L-Leu motif reversed.38 Octapeptin B5 showed MICs ranging from 2–8 mg/L against P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae, whereas the MICs for polymyxin B ranged from 0.5–2 mg/L; both lipopeptides were in active against the S. aureus and E. faecalis strains tested (Table 2).38 These finding suggest the unusually position 5 D-Phe substitution does not impact antibacterial activity against Gram-negatives, but appears to decrease activity against Gram-positives.

Unlike polymyxins, where the cyclic structure is critical for antibacterial activity,15 linear octapeptins have been show to retain comparable in vitro antibacterial activity to their cyclic forms.35

7. Toxicity

The Achilles heel of the polymxyins is dose-limiting nephrotoxicity. There is a clear need to develop less nephrotoxic analogues, thereby allowing the use of higher doses to maximise efficacy and minimise the development of resistance. A number of reports have indicated that the reduction of positive charge renders polymyxins less toxic.15, 60 Considering the octapeptins possess one less positive charge than the polymyxins (i.e 4 vs. 5, respectively), assessments of whether octapeptins display a polymyxin-like dose-dependent nephrotoxicity would be most worthwhile. Acute toxicity assessments in mice by the Bristol-Myers Company showed that the octapeptin Bu-1880 and octapeptin C3 are less toxic than colistin via both intravenous and subcutaneous routes of administration.27, 31, 34 Interestingly, the des-fatty acyl octapeptin C2 was found to be less toxic than colistin by the intravenous route but more toxic subcutaneously. Moreover, the acute toxicity of octapeptin C2, was comparable to octapeptin C3 when administered intravenously, but octapeptin C2was 5-fold more toxic than octapeptin C3 subcutaneously; this would suggest the fatty acyl portion contributes to a depot effect in animals.27, 34

In mouse acute toxicity studies octapeptin B5 show an LD50 of 15.46 mg/kg which was less toxic than the comparator polymyxin B (LD50 6.52 mg/kg).38 Octapeptin B5 was shown to exhibit negligible hemolysis of human and mouse blood cells and no toxicity aganst HEK293 cell up to concentrations of 128 mg/L.35, 38 However, the analogs of octapeptin B5 with N-termini substituted with very hydrophobic Fmoc or myristyl groups showed significantly increased hemolytic activity.35

8. Biosynthesis

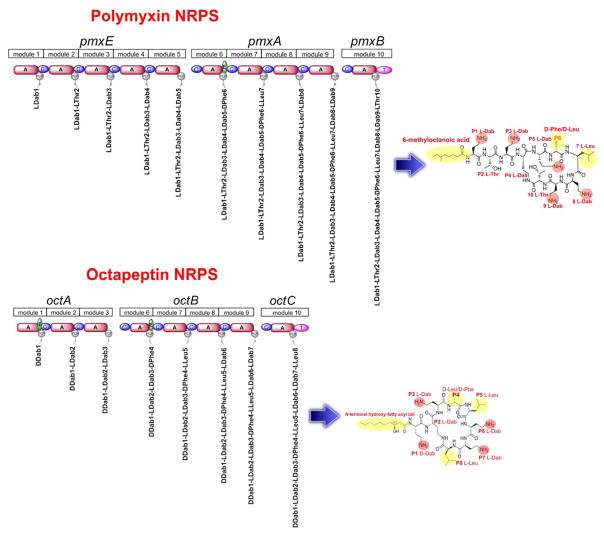

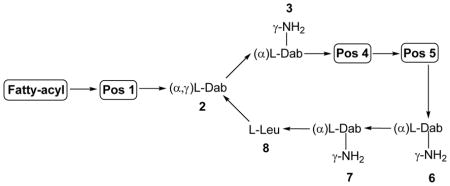

The enormous structural and functional diversity of polymyxin-like lipopeptides is attributable to their nonribosomal mode of biosynthesis by large multifunctional enzymes termed non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS). NRPS enzymes function as natures specialized peptide assembly lines. NRPS are composed of semi-autonomous modular units, which in turn are composed of homologous catalytic domains.61 The order of these modules is co-linear with the sequence of the peptide product, such that the repeating series of modules forms an ordered macromolecular assembly line (Figure 3). Our group characterized the first sequence of an octapeptin biosynthetic cluster from the octapeptin C4 producer Bacillus circulans ATCC 31805 (unpublished results). The assembly of the octapeptin C4 peptide backbone involves three different nonribosomal peptide synthetise (NRPS) systems, OctA, OctB and OctC (Figure 3). The OctA NRPS is composed of three semi-autonomous modular units, which are in turn composed of homologous domains responsible for the activation and polymerisation of the first three constituent amino acids, Dab1-Dab2-Dab3 of the octapeptin peptide core. This tri-peptide is then translocated to the next NRPS, OctB which has four modules that incorporate Phe4-Leu5-Dab6-Dab7 into the growing peptide. The peptide is finally translocated to OctC where it receives the last amino acid Leu8, then is cyclized and concomitantly released by the terminal thioesterase-like (TE) domain on OctC. The three individual NRPS enzymes come together during lipopeptide assembly to form an ordered assembly line. Every module is composed of homologous domains responsible for the activation, modification and polymerisation of the constituent amino acids of octapeptin. The basic modular unit consists of catalytic domains responsible for substrate amino acid activation (A-domain, ~500 amino acids), a Thiolation domain (T, ~80–100 amino acids) which acts to translocate the 4′-phosphopantetheine (4′-Ppant) covalently tethered peptidyl chain intermediate between modular active sites, and a condensation (C-domain, ~450 amino acids) responsible for amide bond formation. In addition to these fundamental domain, some module may harbor auxiliary domain that perform specialized functions such as Epimerization domains (E) (seen in module 6 of OctA) that catalyze the generation of D-configured amino acids from the corresponding L-isomers when attached to the 4′-Ppant; Thio-Esterase domains (TE, ~280 amino acids; seen in module 10 of OctC).61 During the synthesis of non-ribosomal peptides, the growing peptide-chain is transferred from one module to the next, such that the growth of the octapeptin peptide occurs by an ordered succession of transpeptidation and condensation reactions. The consummation of octapeptin assembly results in the release of the mature peptide by ring closure catalyzed by a TE-domain situated at the extreme C terminus of the last module of OctC. The lipidation of octapeptin peptide core with the N-terminal hydroxyl-fatty acyl chain possibly occurs post-assembly and is likely mediated by as yet uncharacterized external fatty acyl ligase enzymes.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the polymyxin B and octapeptin C4 nonribosomal peptide synthetase biosynethtic clusters. These multi-enzyme complexes are composed of modules which contain domains that activate and incorporate the cognate amino acids of each lipopeptide. All modules contain condensation, adenylation (A) and peptidyl-carrier (PCP) and condensation (C) domains. Certain modules also contain an epimerization (E) domain and terminal modules contain a thioesterase domain (TE) which catalyzes the intra-molecular cyclization and release of the lipopeptide.

The smaller octapeptin NRPS cluster contrasts the larger polymxyin NRPS gene cluster which consists of five open reading frames, pmxA, pmxB, pmxC, pmxD and pmxE (Figure 3). Three of the genes pmxA, pmxB and pmxE are NRPS directly involved in polymyxin synthesis, while pmxC and pmxD encode self-resistance ABC transporters responsible for export of the lipopeptide out of the cell. The sequence pmxA (15 kb) encodes for a synthetase of 4,998 amino acids, pmxB (3.3 kb) encodes for a synthetase of 1,102 amino acids and pmxE (18.9 kb) encodes for a synthetase of 6,292 amino acids. The three NRPSs (PmxA, PmxB, and PmxE) contain different numbers of modules, PmxB is a single module NRPS, PmxA is composed of four modules and PmxE of five modules.

From comparisons with the larger polymxyin B NRPS cluster it becomes obvious that the octapeptin NRPS evolved through module deletion events or visa versa the polymyxin NRPS cluster evolved through deletion events. It is tenable to imagine that in order to achieve killing of polymyxin-resistant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria which were competing for nutrients in its environment, Bacillus circulans has evolved the octapeptin core scaffold through module swapping and deletion events of its nonribosomal biosynthetic machinery.62, 63 Whereas, the polymyxin producing Bacillus polymyxa may not have encountered Gram-positive competition, and hence did not have a need to diversify the polymyxin core scaffold to increase its antimicrobial spectrum beyond Gram-negatives. This would make sense given that they are both the polymyxins and octapeptins are produced by closely related Bacillus spp.62, 63 In line with this theory, the aforementioned mode of action studies suggest that octapeptins have retained the polymyxin-like ability to bind to lipid A (a Gram-negative specific outer membrane component), whilst having developed the extra ability to bind to bacterial phospholipids, which endows them with a broader spectrum of activity against Gram-positives and yeast.

9. Outlook

There is a critical requirement for new antibacterial agents to meet growing unmet treatment needs especially in the hospital setting. The time has come for a global commitment to develop new antibiotics. The octapeptins have superior antimicrobial activity against polymyxin-resistant XDR Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and appear to have improved pharmacological profiles compared to the ‘last-line’ polymyxin B and colistin. Based on their higher order activity, lack of cross-resistance and apparent lower toxicity, octapeptins represent viable clinical candidates. The fact that octapeptins are produced by Bacillus circulans via non-ribosomal template driven synthesis makes future biosynthetic approaches aimed at generating therapeutics highly amenable to recombinant technologies. Overall, this review highlights the benefits and caveats underpinning the foundations for the re-development of octapeptins as a new-generation of lipopeptide antibiotics to treat life-threatening infections caused by ‘superbugs’.

Acknowledgments

T. V. and J. L. are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI111965 and AI098771). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. J.L. is an Australian NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. T.V. is an Australian NHMRC Industry Career Development Research Fellow.

References

- 1.Ventola CL. P T. 2015;40:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.C. f. D. C. a. Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United State. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shlaes DM. Antibiotics. 2010. pp. 97–99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shlaes DM, Spellberg B. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IDSA. [last accessed on April 29, 2008];Bad bugs, no drugs. http://www.idsociety.org/badbugsnodrugs.html.

- 6.Journal, 2013

- 7.Clardy J, Fischbach MA, Currie CR. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JM. J S C Med Assoc. 2001;97:38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGraw DJ. Bull Bibliogr. 1986;43:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapor MJ, Erwin D, Erowele G, Wortmann G. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:661–663. doi: 10.1086/588702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Veen HW, Margolles A, Putman M, Sakamoto K, Konings WN. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole K. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:500–508. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikaido H. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:119–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082907.145923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE, Jr, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:657–668. doi: 10.1086/499819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velkov T, Thompson PE, Nation RL, Li J. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1898–1916. doi: 10.1021/jm900999h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyers E, Brown WE, Principe PA, Rathnum ML, Parker WL. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1973;26:444–448. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.26.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers E, Pansy FE, Basch HI, McRipley RJ, Slusarchyk DS, Graham SF, Trejo WH. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1973;26:457–462. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.26.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers E, Parker WL, Brown WE, Linnett P, Strominger JL. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;235:493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker WL, Rathnum ML. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1973;26:449–456. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.26.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker WL, Rathnum ML. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:379–389. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puar MS. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:760–763. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal KS, Ferguson RA, Storm DR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;12:665–672. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenthal KS, Swanson PE, Storm DR. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5783–5792. doi: 10.1021/bi00671a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoji J, Sakazaki R, Wakisaka Y, Koizumi K, Matsuura S, Miwa H, Mayama M. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:182–185. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugawara K, Yonemoto T, Konishi M, Matsumoto K, Miyaki T, Kawaguchi H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983;36:634–638. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato T, Shoji T. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:186–191. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konishi M, Sugawara K, Tomita K, Matsumoto K, Miyaki T, Fujisawa K, Tsukiura H, Kawaguchi H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983;36:625–633. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian CD, Wu XC, Teng Y, Zhao WP, Li O, Fang SG, Huang ZH, Gao HC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1458–1465. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05580-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoji J, Hinoo H, Wakisaka Y, Koizumi K, Mayama M. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1976;29:516–520. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storm DR, Rosenthal KS, Swanson PE. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:723–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawaguchi H, Tsukiura H, Fujisawa KI, Numata KI. Journal. 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makimura Y, Asai Y, Sugiyama A, Ogawa T. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1440–1446. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidorczyk Z, Zahringer U, Rietschel ET. Eur J Biochem. 1983;137:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konishi M, Sugawara K, Tomita K, Matsumoto K, Miyaki T, Fujisawa K, Tsukiura H, Kawaguchi H. Journal of Antibiotics. 1983;36:625–633. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Zoysa GH, Cameron AJ, Hegde VV, Raghothama S, Sarojini V. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;58:625–639. doi: 10.1021/jm501084q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.HGaS, De Zoysa V. Chemistry in New Zealand. 2015 Apr;:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyers E, Pansy FE, Basch HI, McRipley RJ, Slusarch Ds, Graham SF, Trejo WH. Journal of Antibiotics. 1973;26:457–462. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.26.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian C-D, Wu X-C, Teng Y, Zhao W-P, Li O, Fang S-G, Huang Z-H, Gao H-C. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2011 doi: 10.1128/AAC.05580-11. published ahead of print, 19 Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikaido H. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hancock RE. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:1–3. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hancock RE. Lancet. 1997;349:418–422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hancock RE. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)81773-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hancock RE, Lehrer R. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velkov T, Thompson PE, Nation RL, Li J. J Med Chem. 53:1898–1916. doi: 10.1021/jm900999h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunn JS. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, Kim K, Guo L, Hackett M, Miller SI. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gunn JS, Ryan SS, Van Velkinburgh JC, Ernst RK, Miller SI. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6139–6146. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6139-6146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schurek KN, Sampaio JL, Kiffer CR, Sinto S, Mendes CM, Hancock RE. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4345–4351. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01267-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi Y, Cromie MJ, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaara M. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1991;17:437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viljanen P, Vaara M. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:701–705. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterson AA, Fesik SW, McGroarty EJ. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:230–237. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyers E, Parker WL, Brown WE. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1976;29:1241–1242. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koike M, Iida K, Matsuo T. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:448–452. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.1.448-452.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swanson PE, Paddy MR, Dahlquist FW, Storm DR. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3307–3314. doi: 10.1021/bi00555a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LaPorte DC, Rosenthal KS, Storm DR. Biochemistry. 1977;16:1642–1648. doi: 10.1021/bi00627a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deris ZZ, Akter J, Sivanesan S, Roberts KD, Thompson PE, Nation RL, Li J, Velkov T. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013;67:147–151. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shoji J, Hinoo H, Sakazaki R. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1976;29:521–525. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaara M, Fox J, Loidl G, Siikanen O, Apajalahti J, Hansen F, Frimodt-Moller N, Nagai J, Takano M, Vaara T. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3229–3236. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00405-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Velkov T, Lawen A. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2003;9:151–197. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(03)09002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park SY, Choi SK, Kim J, Oh TK, Park SH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;78:4194–4199. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07912-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choi SK, Park SY, Kim R, Kim SB, Lee CH, Kim JF, Park SH. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3350–3358. doi: 10.1128/JB.01728-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]