Abstract

The UN Sustainable Development Goals of 2015 have restored universal health coverage (UHC) to prominence in the international health agenda. Can understanding the past illuminate the prospects for UHC in the present? This article traces an earlier history of UHC as an objective of international health politics. Its focus is the efforts of the International Labor Organization (ILO), whose Philadelphia Declaration (1944) announced the goal of universal social security, including medical coverage and care. After World War II, the ILO attempted to enshrine this in an international convention, which nation states would ratify. However, by 1952 these efforts had failed, and the final convention was so diluted that universalism was unobtainable. Our analysis first explains the consolidation of ideas about social security and health care, tracing transnational policy linkages among experts whose world view transcended narrow loyalties. We then show how UHC goals became marginalized, through the opposition of employers and organized medicine, and of certain nation states, both rich and poor. We conclude with reflections on how these findings might help us in thinking about the challenges of advancing UHC today.

In September 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were announced at a summit of the United Nations in New York.1 Comprising numerous social, economic, and environmental policy objectives, these followed the Millennium Development Goals of 2000 through 2015, in which public health targets had figured prominently. Although they continued earlier concerns with reducing infectious diseases and child mortality, a novel feature of the SDGs was Target 3.8:

Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.2

Not only did this prioritize health systems on the UN agenda, but it also emphasized universalism, in a way rarely seen since the “Health For All” drive of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 1970s.3

What exactly does the target of universal health coverage (UHC) imply? “Coverage” is a term deriving from the insurance industry, but proponents of UHC stress that it may also refer to tax-based health security.4 Equally, “universal” has never straightforwardly signified the whole population. For example, an early usage, from Germany in 1882, referred to the “universal adoption of sickness insurance” with respect to Bismarck’s scheme to compel only the industrial workforce to join sick funds.5 Such definitional ambiguities have cued an impassioned debate among today’s global health community about how UHC should be operationalized in low- and middle-income countries. Latin America is a particular focus of controversy. Some advocate the approach of “structured pluralism,” with insurance as the main medium of coverage, and the state’s role as regulator rather than provider. Others argue that the priority must be universal health care as a basic human right, and that statist single-payer systems are best placed to deliver this.6

This is not the first time that the issue of universal rights to health services has generated debate in the international arena. This article discusses an earlier episode, centered on the Philadelphia Declaration of the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 1944. The ILO was originally an autonomous agency of the League of Nations, founded in the aftermath of World War I with the “protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment” among its constitutional goals.7 The ILO’s methods included an annual conference at which optimal standards, initially drafted by its officials, were debated and agreed upon. These were written into “conventions,” which states were asked to ratify, or “recommendations,” which were advisory and nonbinding. States were then offered advice and information on how to develop appropriate legislation.8

The Philadelphia Declaration was propounded in the latter stages of World War II, when the ILO had fled Geneva, Switzerland, for the safety of Montreal, Canada. It set out a vision of basic political and economic rights for working people in the postwar settlement. These encompassed the full gamut of social security arrangements available in more-advanced welfare states, including the right to sickness benefits and “comprehensive medical care.”9 In the recommendation that elaborated the main text, a universalist intent was specified. Health services were for “all members of the community, whether or not they are gainfully occupied”; if under a social insurance system, the uninsured would have the same right to care “pending their inclusion”; if under a state public health service, then “all beneficiaries should have an equal right” to care, without qualifying conditions or means testing.10 Once peace was achieved, debate began on how these ideals could be translated into a convention and hence into action by member states. The outcome, in 1952, was a bitter disappointment to champions of the declaration, for the text that was finally agreed upon had so diluted the standards required for ratification that the original goals were lost.

Our aim in this article is to describe and explain this earlier rise and fall of UHC as a goal in international health policy. How and why did it come onto the agenda, and why was it ultimately unsuccessful? Conceptually, we follow scholars of international organizations who find the key to understanding change in the tensions between the authority of the member states and the autonomous actions of the agencies themselves.11 Within this literature is a spectrum of emphasis. Some argue that the interests of the most powerful nations are always the dominant forces in international engagement, and that international organizations exert no supranational authority over the anarchic behavior of individual states, each in “a struggle for power.”12 Others stress the global issues that compel states toward interdependence, fostering independent bureaucracies and transnational networks of expertise through which international organizations formulate and shape policy distinct from the goals of national actors.13

Signing the Philadelphia Declaration, May 17, 1944. Seated, left to right, Franklin D. Roosevelt (President, United States), Walter Nash (Deputy Prime Minister, New Zealand; President, International Labor Conference), Edward J. Phelan (Acting Director, International Labor Organization [ILO]). Standing, left to right, Cordell Hull (Secretary of State, United States), Frances Perkins (Secretary of Labor, United States), Lindsay Rogers (Assistant Director, ILO).

Source: International Labor Organization Photo Archive, ILO.

Our explanation falls somewhere between these poles. The powers delegated to the ILO’s bureaucracy at its foundation, and the internationalist nature of early welfare state development, encouraged its increasing advocacy of health coverage under social insurance. However, the weakness of the League of Nations system meant that the ILO lacked authority, and its early work in this field was Eurocentric and of limited achievement. In the late 1930s and 1940s, a temporary concordance between ILO experts and policymakers in Britain and the United States informed planning for more comprehensive health cover under social security. However, with the advent of peace, the Cold War, and the impending end of colonialism, the positions of the member states became too divided to sustain the ILO’s ambitious vision.

First, we focus on the interwar period, establishing the international context of health policymaking within incipient state welfare schemes, then identifying the themes, networks, and individuals whose intellectual groundwork underlay the Philadelphia Declaration’s medical sections. We next describe the debates between officials and member states prior to, and following, the declaration, then advance our explanation for its failure, blending issues of ideology, practicality, and realpolitik. We close with reflection on how this history speaks to the present juncture. Our method is documentary research in the Geneva archives of the ILO, the League of Nations Health Organization, and the WHO, including conference proceedings, journals, committee records, correspondence, and office files.

Adrien Tixier (1893–1946), Director of Social Insurance Section, International Labor Organization, 1927–1937.

Source: International Labor Organization Photo Archive, International Labor Organization.

THE INTERWAR CONTEXT

The circumstances of the ILO’s establishment at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 were conducive to innovative thought about social security. Britain, France, and the United States took the leading role in its creation, at a time when each was preoccupied with labor unrest at home and abroad. In particular, the Russian Revolution encouraged politicians to create a Western foil to Bolshevism, in which representatives of workers, employers, and governments would convene to address the injustices that otherwise provoked conflict.14 The delegation of responsibilities for social goals to the ILO therefore had a legitimation function, but it also responded to the spread of socialist or social democratic ideas, and the softening of laissez-faire principles within liberalism, as in French solidarisme, British New Liberalism, and American Progressivism.

The context in which the ILO’s thinking occurred was one of expanding entitlements to health services within prominent nation-states. Prior to the 1880s, individuals outside the medical marketplace resorted either to poor laws or charity, or joined mutual sickness funds, sometimes regulated or subsidized by governments. A fundamental break came in Germany, with Bismarckian social insurance against sickness (1883), accidents (1884), and old age and disability (1889). This mandated employer contribution to sick funds; compelled participation of substantial sections of the working class, thus creating large general risk pools; and introduced (initially through accident insurance) the principle of no-fault liability, so that risk was removed from the individual and managed collectively using actuarial mathematics.15 The national health insurance (NHI) approach was taken up in the territories of Austria-Hungary, whose constituent nations retained and extended it on gaining independence following World War I. Britain adopted a variant in 1911, and France in 1930. The Soviet Union’s Constitution enshrined a public health system in 1917, although implementation awaited stability in the 1920s.16 In the liberal democracies, the first constitution pledging “a comprehensive system of insurance . . . to maintain health” as a right of citizenship was that of Germany’s Weimar Republic (1919).17 The United States considered, then rejected, NHI proposals placed before state legislatures in the 1910s, and did so again when mooted by New Dealers for the Social Security Bill in 1934 and 1935, although some Latin American nations, such as Chile, adopted it (1924).18 More radically, New Zealand’s Labour government pioneered a state national health service in 1938.19

This early welfare state building was inherently internationalist, for contemporary policymakers frequently employed foreign comparison and borrowing. Bismarck had been inspired by French Emperor Louis Napoleon’s regulation of mutual funds, whereas both Britain and France borrowed from Germany, their upstart competitor.20 US Progressives reported on England and Germany and deployed international comparison in reform propaganda.21 New Zealanders sought to surpass British NHI, whereas the Soviet Union (which joined the ILO in 1934) attracted much observer interest as an ideal type.22 In sum, then, the officials of League of Nations organizations and their constituent representatives would have been well aware of health policymaking as a common and active endeavor across the member states, albeit with much national variation.

Within this context, discussion of access to health services came formally onto the ILO’s agenda in 1927. One route was through the League of Nations Health Organization (LNHO). This separate agency of the League had originated as its Provisional Health Committee (1921), to address its Covenant obligations for the control and prevention of disease. Its activities included establishing a global surveillance network, collating comparative health metrics, developing the International Classification of Diseases, and providing technical assistance, for example in Greece and China.23 Several of its leading figures were from Central European countries and advocates of social medicine, such as the Polish bacteriologist Ludwik Rajchman and the Yugoslav professor of hygiene Andrija Stampar. It was another successor state, Czechoslovakia, that first requested the LNHO to advise on a problem common to nations developing social health insurance. How should this work alongside public health agencies, which were typically funded by the local state to deal with tuberculosis and infant health?24 Behind this question lay issues of entitlement and the irrationality of systems relying partly on general taxation and partly on individual insurance. A joint LNHO–ILO committee was convened to consider this, chaired by Sir George Newman, the British chief medical officer, a mainstream liberal. Unsurprisingly, it backed away from recommending formal integration, in favor of less-rigid consultative councils.25

The second area of action was the ILO’s Sickness Insurance (Industry) Convention of 1927. Ratifying nations agreed to establish compulsory sickness insurance for workers in industry and commerce, principally through self-governing nonprofit institutions funded by employees and employers.26 Various exceptions were permitted to the occupations covered, deductibles and qualifying periods were allowed, and the state’s contribution was determined nationally. Ten years on, only 15 member states had ratified: Germany, Hungary, and Luxembourg (1928); Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Latvia (1929); Bulgaria (1930); Great Britain, Chile, and Lithuania (1931); Spain (1932); and Uruguay and Colombia (1933).27

The nature of the convention, and the predominance of Central European states among the early signatories, illuminates the proactive role of key ILO staff, who now keenly advocated a German, Bismarckian model of NHI. This arose partly from the “privileged representation” of German experts in the ILO’s Correspondence Committee on Social Security.28 Also important were two ILO officials: Adrien Tixier, a disabled French war veteran who headed the Social Insurance Section, and his Czech deputy, Osvald Stein, who had earlier overseen unemployment insurance in Austria.29 Both were prominent in establishing the International Conference of National Unions of Mutual Benefit Societies and Sickness Insurance Funds (predecessor of the International Social Security Association), whose title acknowledged the differing French and German approaches.30 Chaired by a Czech politician and ILO official, Leo Winter, they used this as a “propaganda tool” in the international promotion of social insurance.31

International advocacy for the expansion of NHI by ILO figures became more urgent during the Depression. An LNHO memorandum of 1932 by German Health Section official Otto Olsen argued this was a humanitarian and political necessity, for insecurity could foster the extremism exemplified by Hitler.32 These themes were echoed in 1933 by a new ILO–LNHO expert committee considering “the best methods of safeguarding public health during the depression.” Chaired by Georges Cahen-Salvador, an expert on Bismarckian insurance and active promoter of NHI in France, the committee included other leaders of European social medicine, such as Jacques Parisot, Franz Goldmann, Winter, and Stampar.33 Its conclusion was that “compulsory sickness insurance must be regarded as the most appropriate and rational method of organizing the protection of the working classes.”34 Tixier, too, became bolder, dismissing earlier objections that broadening entitlements to dependent family members would damage private medicine, and frankly asserting the inadequacy of “individual saving, public assistance, and voluntary insurance” for achieving social security. Instead, “compulsory social insurance . . . is the most scientific and the most effective means.”35 Although still hesitant about recommending a “public medical service” for “the whole population of the country,” he felt it “fairly safe to say” that “State intervention” in combination with NHI made this direction inevitable.36 Thus, by 1939 an ILO position was discernible that yoked modernist tropes of science and rationality to a vision of progressive advance.

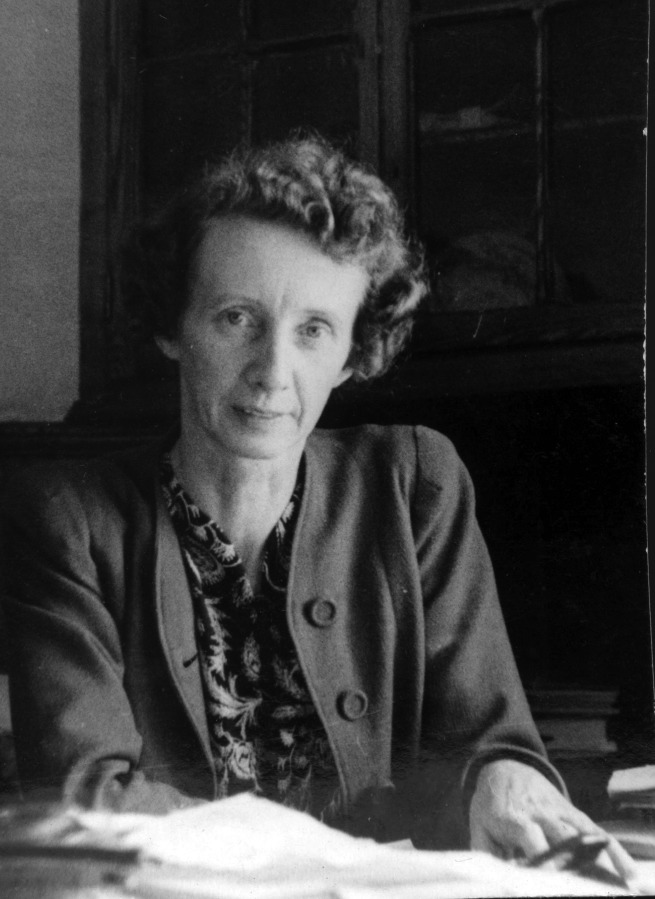

Laura Bodmer (1898–1965), Member, Social Insurance Section (Later, Social Security Division), International Labor Organization, 1932–1958.

Source: International Labor Organization Photo Archive, International Labor Organization.

TOWARD THE PHILADELPHIA DECLARATION

From this base, a more radical position was adopted in 1944. Why? Partly the answer lies with the changing international context and the publication of two influential documents in 1942. One was Britain’s Beveridge Report. ILO officials had contributed evidence to this, although they felt their influence was doubtful compared with the “strong movement in the trade unions and among the private ‘planners’” favoring the radical developments in New Zealand.37 William Beveridge’s vision of a universal, comprehensive social security system captured the war-weary public imagination at home, inspired exiled French and Scandinavian politicians in London, and quickly circulated in the Anglophone world.38 In North America, the National Resources Planning Board report, Security, Work and Relief Policies, was also significant for broaching a universalist language.39 For example, both documents, and the New Zealand innovations, shaped thinking in Canada, the ILO’s temporary home, where the Marsh Report (1943) proposed full employment, social security, and health insurance against “universal risks.”40

International Labor Organization (ILO) Consultation of Social Security Experts, Montreal, Canada, July 9–12, 1943. A: Edward J. Phelan (Acting Director ILO). B: William Beveridge (author Social Insurance and Allied Services). C: Isidore S. Falk (Director of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration, USA). D: Edgarde Rebagliati (Director, National Insurance Fund, Peru). E. Leonard C. Marsh (author of Report on Social Security for Canada). F: Miguel Etchebarne (former Chilean Minister of Public Health and Social Insurance).

Source: International Labor Organization Photo Archive, ILO.

The importance of British and American social thought also reflected changing networks of expertise and influence that followed Europe’s disintegration and the ILO’s flight West in 1940.41 Advisers from the Roosevelt administration now came center stage in the ILO’s consultative work, for having drawn heavily on European precedents in making New Deal legislation they could now offer America’s own experience.42 In addition, with the introduction of the first Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill seeking to implement federal health insurance in the United States (1943), new questions arose about how international recommendations would accommodate an American model. Also to the fore came Latin American officials, building on networks that Stein had developed through an inter-American conference and the Declaration of Santiago de Chile (1942), which outlined a social security program and technical assistance arrangements.43

The adoption of more radical elements of British policy also followed changes within the ILO bureaucracy in 1943, after Stein’s accidental death and Tixier’s departure to the Free French. Maurice Stack now headed the Social Insurance Section, but of more central importance was Laura Bodmer. An Anglo-German economist with a PhD from Zurich, Switzerland, in British trade unionism, Bodmer joined the ILO as a statistician in 1925, moving to the section in 1932, where she increasingly specialized in “des questions medico-sociales.”44 She took main responsibility for drafting sections on medical aspects of social security for the declaration, creating and then amending texts in a balancing act between ILO goals and member state wishes.

This process began with a major consultation in July 1943, convening luminaries like Britain’s William Beveridge; American New Deal experts Isidore Falk, Arthur Altmeyer, and George Perrott; Canadian NHI planner Leonard Marsh; and Latin American politicians Miguel Etchebarne (Chile) and Edgarde Rebagliati (Peru). Bodmer’s draft proposed a health plan covering “all individuals whether or not gainfully occupied” and comprehensive in form, providing “all care required for the restoration, conservation and promotion of health.”45 Her preferred option was a “public general service” financed by general or special taxation; the alternative was contributory social insurance supported by taxation for individuals unable to pay.46 In the ensuing discussions, American delegates like Falk repositioned the “general medical service” as a longer-range “ultimate objective” achievable incrementally through different paths, rather than by forcing nations into a “common mold.”47 The agreed text was debated at the International Labor Conference in Philadelphia, where it was embraced by a vote of 76 to 6.48 Among abstainers was the US government, whose employer delegates disapproved, and the UK government, resistant to intrusion into its colonial sphere of influence.

DILUTING THE CONVENTION, 1949–1952

Against the backdrop of reconstruction and the creation of the United Nations, the ILO now worked toward a convention that would implement the vision of 1944. Formal decisions were taken at its annual conferences, with consultations in the interim. Retreat from the recommendation that accompanied the declaration was first obvious at the 1951 International Labor Conference. After debate of a draft convention, it was decided that ratification could be for either “minimum” or “advanced” standards.49 Dilution went further at the 1952 International Labor Conference, where the convention was finally approved. Ratifying members needed only to implement three out of the nine specified branches of social security, and could thus omit medical insurance altogether.50 In addition, low-income nations could claim temporary exemptions to even these obligations. In place of compulsion, voluntary insurance was accepted, and the principle of state subsidy rejected. The notion of advanced standards to which richer ratifying nations should subscribe was also dropped.51

Four explanations can be suggested for this outcome. First was the pragmatic concern of low-income countries about the requirements of the declaration. The need to distinguish minimum and advanced standards was evident to Latin American member states contemplating the extension of social security to rural populations. Given their lack of resources, they would have to retreat from universalism and comprehensiveness, and instead “try to extend, as soon as possible, to the greatest number of persons, within the possibilities of each country, social security medical services, or other appropriate methods.”52 It was newly independent India that proposed the idea of permitted exclusions, considering even the “minimum standards” too demanding for a country whose population was highly dispersed and largely rural.53 To some extent, these difficulties arose from the mostly Eurocentric precedents in ILO thinking about welfare, but they may also reflect the fissures within the early United Nations over the nature of internationalism under late colonialism. Although representatives from Latin America, China, the Soviet Union, and India envisaged the supervisory role of the UN system displacing colonial prerogatives, the imperial powers, with some support from the United States, were broadly successful in preserving “a world safe for empire” in the new dispensation.54 This was hardly conducive to generalizing Western models of health security to poorer nations.

Second, opposition was articulated by hostile business and medical interest groups. Employers’ representatives inveighed against the proposals in intemperate language: it was a “monstrosity,” a “Utopian” project; it augured “socialisation . . . destruction”; it would extend the “all-embracing tentacles” of the state. Above all, it was beyond the ILO’s sphere of competence.55 Physicians also expressed their discontent, following the launch in 1947 of the World Medical Association, aided by funding from US pharmaceutical firms. As in national debates, objections emphasized patients’ freedom of choice, and doctors’ rights to diagnose, treat, and charge as they saw fit. The underlying agenda, though, was to defend the profession’s status and market position.56

Third was the well-documented marginalization of social medicine in postwar international health.57 The ILO had initially hoped that the newly created WHO would endorse and support the proposals. Yet although its constitution proclaimed the human right to “the highest attainable standard of health,” its founding article on “strengthening health services” pledged only assistance “upon request.”58 Nonetheless, in 1951 a joint WHO–ILO consultant group was formed to address the draft convention, containing leading social medicine exponents like Henry Sigerist and René Sand. Its statement backed the ILO position, favoring, inter alia, universal coverage where possible, services free from means testing or cost sharing, remuneration by salary as optimal, unified national administration, and regionally integrated hospitals and clinics.59 The WHO’s Executive Board immediately distanced itself from this, and the World Medical Association claimed the “vast majority” of physicians disagreed.60 By now, WHO policy was moving firmly toward big, “vertical” interventions against infectious diseases, due both to faith in biotechnical solutions like vaccines and pesticides and to baser geopolitical considerations.61 Health systems work merited only a “study and report” brief.

Finally, the position of the United States, as the key funder of the United Nations and now the leading world power, was crucial. The attempts of the Truman administration to legislate for NHI had been roundly defeated, not least because of a vituperative and well-funded campaign by the American Medical Association (in which World Medical Association council members Louis Bauer and Morris Fishbein were prominent).62 As AJPH readers will know, moderate New Deal progressives were then tarnished by character assassination, while more radical health internationalists endured a McCarthyite purge.63 Faced with this domestic context, it became impossible for the United States to support a universalist health services agenda on the world stage. Such considerations would remain matters for national jurisdiction.

CONCLUSIONS

This account of the early rise and fall of UHC illustrates the capacity of international organizations to exercise some autonomous agency. Building health systems within proto-welfare states was always a supranational endeavor, because no country, even Bismarck’s Germany, was immune from the diffusion of ideas and policy learning. National experiences fostered communities of experts willing to serve in international bodies, although external events could determine which regions and ideas dominated at different times, and epistemic communities could be oppositional as well as supportive. Responsible officers within organizations were similarly conditioned by prior experiences, but they also sought a creative and proactive role in directing policy, beyond simply reacting to the perceived position of member states.

In this case, though, the arc of the story was determined by the willingness of powerful member states to delegate authority to the ILO. Health system reform to universalize single-payer or NHI models has never been uncontentious, touching as it does on the material concerns of vested interests and on core beliefs about equity and individualism. Once the idealistic ardor of wartime cooled, national interests disrupted the apparent consensus. Low-income countries sought acknowledgment that poverty drastically constrained ambition, and into this breach it was easy for opponents to ride, depleting commitments until they were worthless. Colonial calculations played some part in Britain’s reluctance, and Cold War polarities helped determine the US position, in which “socialized” medicine was now anathema. The new global superpower would not endorse a position unacceptable within its own national polity.

How might this history speak to the present? Of course, much has changed in the interim. The movement for “selective primary health care” from the 1980s narrowed the meaning of universalism to entitlement to a limited number of services of proven cost-effectiveness. At the same time, the constraints exercised by powerful member states have been offset by the proliferation, since the 1990s, of philanthropic foundations and public–private partnerships that can set agendas unfettered by national governments. However, some parallels remain. Then as now, the goal of universalism was politically controversial, with today’s “structured pluralism” bearing some affinity to the incremental advance that Americans like Falk advocated between 1938 and 1950. Today’s champions of universal health care may also trace their genealogy to progressive social medicine advocates of the midcentury.

The recurrent nature of this debate prompts challenging questions. How far should idealists stifle their objections and work with pragmatists to exploit opportunities that were missed before? Where are the oppositional networks of today, and how can they be addressed, so that vested interests do not impede the honoring of human rights?64 What examples of best practice can be advanced to better address the pragmatic objections of poor countries, so that, unlike in 1949 to 1952, these do not become a wedge to forestall change?65 And what will be the leadership role of the United States, at a time when its own domestic health politics, and the nationalist sentiments circulating among its electorate, also echo the early 1950s?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our research is funded by a Wellcome Trust Medical Humanities Investigator Award (grant 106720/Z/15/Z), and we are most grateful for this generous support.

We thank Marcos Cueto and James Gillespie for preliminary advice, and Anne Mills and Martin McKee for their comments. The assistance of M. Jacques Rodriguez in the archives of the International Labor Organization was indispensable.

Preliminary versions were presented at the European Healthcare Before Welfare States Conference, University of Huddersfield, February 17, 2017; History Seminar Series, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, May 18, 2017; and the European Association for the History of Medicine and Health Conference, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, August 30–September 2, 2017. We thank participants for their feedback.

Footnotes

See also de Camargo Jr, p. 301.

ENDNOTES

- 1. “Breakdown of UN Sustainable Development Goals,” New York Times, September 26, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/26/world/breakdown-of-un-sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed December 18, 2017)

- 2. UN Sustainable Development Platform, Goal 3.8, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed December 18, 2017)

- 3. M. Cueto, “The Origins of Primary Health Care and Selective Primary Health Care,” American Journal of Public Health 94, no. 11 (2004): 1864–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. A. Mills, Universal Health Coverage: The Holy Grail? (London, UK: Office of Health Economics, 2014), 3.

- 5. W. H. Dawson, Social Insurance in Germany, 1883–1911: Its History, Operation, Results, and a Comparison With the National Insurance Act, 1911 (London, UK: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912), 8.

- 6. Juan-Luis Londoño and Julio Frenk, “Structured Pluralism: Towards an Innovative Model for Health System Reform in Latin America,” Health Policy 41, no. 1 (1997): 1–36; Julio Frenk, “Leading the Way Towards Universal Health Coverage: A Call to Action,” The Lancet 385, no. 9975(2015): 1352–1358; Nila Heredia, Asa Cristina Laurell, Oscar Feo, José Noronha, Rafael González-Guzmán, and Mauricio Torres-Tovar, “The Right to Health: What Model for Latin America?” The Lancet 385, no. 9975 (2015): e34–e37; Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Laura Nervi, and Eduardo Siqueira, “Neoliberalism Redux: The Global Health Policy Agenda and the Politics of Cooptation in Latin America and Beyond,” Development and Change 47, no. 4 (2016): 1–26.

- 7. “Appendix II Constitution of the International Labour Organization: Preamble, 1919,” in Gerry Rodgers, Eddy Lee, Lee Swepston, and Jasmien Van Daele, The International Labour Organization and the Quest for Social Justice, 1919–2009 (Geneva, Switzerland: ILO, 2009), 249.

- 8. Rodgers et al., International Labour Organization, 19–20.

- 9. “Appendix II Declaration Concerning the Aims and Purposes of the International Labour Organization (Declaration of Philadelphia), 1944,” in Rodgers et al., International Labour Organization, 253.

- 10. “Recommendation Concerning Medical Care. Adoption: Philadelphia, 26th ILC session (12 May 1944),” International Labour Organization, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312407 (accessed January 12, 2018)

- 11. D. Hawkins, D. Lake, D. Nielson, and M. Tierney, “Delegation Under Anarchy: States, International Organizations, and Principal–Agent Theory,” in Delegation and Agency in International Organizations, ed. D. Hawkins, D. Lake, D. Nielson, and M. Tierney (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 3–38; Chelsea Clinton and Devi Sridhar, Governing Global Health: Who Runs the World and Why? (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017), 20–22, 30–32.

- 12. H. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948); Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (London, UK: Addison Wesley, 1979)

- 13. R. Keohane and J. S. Nye, Power and Interdependence (London, UK: Longman, 2012); Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore, Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004); Nitsan Chorev, The World Health Organization Between North and South (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012)

- 14. A. Alcock, History of the International Labour Organisation (London, UK: Macmillan, 1971); Rodgers et al., International Labour Organization, 2–8.

- 15. E. P. Hennock, The Origin of the Welfare State in England and Germany, 1850–1914: Social Policies Compared (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007)

- 16. H. E. Sigerist, Socialised Medicine in the Soviet Union (London, UK: Victor Gollancz, 1937)

- 17. D. Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity (London, UK: Allen Lane, 1991), 133.

- 18. P. Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1982), 243–257, 263–270; A. Tixier, “The Development of Social Insurance in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay: II,” International Labour Review 32 (1935): 624–626.

- 19. L. Bryder and J. Stewart, “Some Abstract Socialistic Ideal or Principle: British Reactions to New Zealand’s 1938 Social Security Act,” Britain World 8, no. 1 (2015): 51–75.

- 20. G. A. Ritter, Social Welfare in Germany and Britain: Origins and Development (Leamington Spa, UK: Berg, 1986), 34–35, 53; E. P. Hennock, British Social Reform and German Precedents: The Case of Social Insurance, 1880–1914 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1987); Allan Mitchell, The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991)

- 21. D. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998)

- 22. Bryder and Stewart, “Some Abstract Socialistic Ideal,” 56–57; E. Fee, “The Pleasures and Perils of Prophetic Advocacy: Henry E. Sigerist and the Politics of Medical Reform,” American Journal of Public Health 86, no. 11 (1996): 1637–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. I. Borowy, Coming to Terms With World Health the League of Nations Health Organisation, 1921–1946 (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: P. Lang, 2009)

- 24. LONA R 968/12B/46868/46868, “Sixth Assembly of the League of Nations. Work of the Health Organisation. Resolution Proposed by the Second Committee and Adopted by the Assembly on September 21st, 1925 (Morning),” September 1925.

- 25. LONA R 968/12B/46871/46868, “League of Nations Health Organisation. Notes on the Health Insurance Inquiry”; LONA R 992/12B/58852/57687, “Joint Commission of Experts for the Study of the Relationship Between Public Health Services and Health Insurance Organisations. Report of the First Session,” 1927; LONA R 992/12B/58852/57687, Sir George Newman, untitled draft speech, March 1927.

- 26. International Labour Organization, “Sickness Insurance (Industry) Convention, 1927 (No. 24),” http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE: C024 (accessed December 18, 2017)

- 27. ILO ACD 3-24-0-1, Ten Yearly Reports on Sickness Insurance, “Draft Report of the Governing Body of the International Labour Office Upon the Working of the Convention (No 24),” 7.

- 28. S. Kott, “Une ‘communauté Épistémique’ du Social? Experts de l’OIT et Internationalisation Des Politiques Socialises Dans L’entre-Deux-Guerres,” Genèses 71, no. 2 (2008): 30; idem., “Dynamiques de L’internationalisation: L’allemagne et L’organisation Internationale Du Travail (1919–40),” Critique Internationale 52, no. 3 (2011): 69–84.

- 29. Anon, “Adrien Tixier,” International Labour Review 53, no. 1–2 (1946): 1–4; anon, “Osvald Stein,” International Labour Review 49, no. 2 (1944): 139–144.

- 30. C. Guinand, “The Creation of the ISSA and the ILO,” International Social Security Review 61, no. 1 (2008): 81–98; Sandrine Kott, “Constructing a European Social Model: The Fight for Social Insurance in the Interwar Period,” in ILO Histories: Essays on the International Labour Organization and Its Impact on the World during the Twentieth Century, ed. Jasmien Van Daele, Magaly Rodriguez Garcia, and Geert van Goethem (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2010), 173–195.

- 31. Kott, “Une ‘Communauté Épistémique’ du Social?,” 40–41.

- 32. “The Economic Depression and Public Health Memorandum Prepared by the Health Section,” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 1 (2015): 62–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. E. Jabbari, Pierre Laroque and the Welfare State in Postwar France, Oxford Historical Monographs (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012), 20–21; Borowy, Coming to Terms With World Health, 372.

- 34. ILO SI 21/7/2/3, The Best Methods of Safeguarding the Public Health During the Depression, 18.

- 35. ILO SI 21/7/2/3, letter, Tixier to Kinnear, September 27, 1933; A. Tixier, “The Development of Social Insurance in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay: II,” 779.

- 36. Adrien Tixier, “Social Insurance Medical Services,” International Labour Review 29 (1934): 189–190, 198.

- 37. M. Margairaz, “L’OIT et la Sécurité du Travail. Du Rapport Beveridge à la Conférence de Philadelphie: l’invention de la Sécurité Sociale,” in Humaniser le Travail: Régimes Économiques, Régimes Politiques et Organisation Internationale du Travail (1929-1969), ed. Alya Aglan, Olivier Feiertag, and Dzovinar Kévonian (Brussels, Belgium: PIE-P. Lang, 2011), 131–148, at 142–143; ILO SI 4/0/67/1, letter, Stack to Henderson, June 18, 1942.

- 38. Great Britain Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, and William Henry Beveridge, Social Insurance and Allied Services (London, UK: HMSO, 1942), 18, 287–293.

- 39. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, 489–500; National Resources Planning Board, Security, Work, and Relief Policies, 1942: Report of the Committee on Long-Range Work and Relief Policies to the National Resources Planning Board (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1942)

- 40. L. Marsh, Report on Social Security for Canada (Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1943 [1975]), xiii–xviii, 26–27.

- 41. Rodgers et al., International Labour Organization, 151.

- 42. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, 437–446; Jill Jensen, “US New Deal Social Security Experts and the ILO, 1948–1954,” in Globalizing Social Rights: The International Labour Organization and Beyond, ed. Sandrine Kott and Joëlle Droux, ILO Century Series (Geneva, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan and International Labour Office, 2013), 172–189.

- 43. “The Work of the Inter-American Conference on Social Security at Santiago de Chile. A New Structure of Social Security,” International Labour Review 46 (1942): 661–691.

- 44. ILO File P. 1844, “Miss L. Bodmer,” Dossier du Service Personnel.

- 45. ILO SI 23-10-1, “Social Security Consultation on Income Maintenance and Medical Care,” paragraphs 406, 409.

- 46. “Social Security Consultation,” passim; ILO SI 23-10-1, draft letter, Bodmer to Falk, August 1943.

- 47. ILO SI 23-10, “Minutes of Meeting Held by Medical Sub-Committee, 11 July 1943, at 3 p.m.” 6, 7, 10A; ILO SI 23-10-1, 17:OD, letter, Falk to Bodmer, August 14, 1943.

- 48. International Labour Conference. Twenty-Sixth Session, Philadelphia, 1944. Record of Proceedings (Montreal, Canada: ILO, 1944), 269.

- 49. Objectives and Minimum Standards of Social Security. Report IV(1) (Geneva, Switzerland: ILO, 1950)

- 50. These were as follows: unemployment benefit, invalidity benefit, medical care, sickness benefit, employment injury, survivors’ allowances, old-age pensions, maternity benefit, and family allowances.

- 51. Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952 (No. 102), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312247 (accessed December 18, 2017)

- 52. International Labour Office, “Resolution Concerning Medical Care,” Official Bulletin, June 20, 1952, pp. 24–25.

- 53. International Labour Conference. Thirty-Fifth Session, Geneva, 1952. Record of Proceedings (Geneva: ILO, 1953), 325.

- 54. J. L. Pearson, “Defending Empire at the United Nations: The Politics of International Colonial Oversight in the Era of Decolonisation,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 45, no.3 (2017): 525–549, at 543; Mark Mazower, No Enchanted Palace: the End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009)

- 55. International Labour Conference. Thirty-Forth Session, Geneva, 1951. Record of Proceedings (Geneva, Switzerland: ILO, 1952), 398–401.

- 56. ILO NGO 53/1, “Preliminary Report on Social Security and the Medical Profession,” World Medical Association Bulletin 3 (1949): 114–118; ILO NGO 53/1, “Report on Mission to the Third General Assembly of the World Medical Association,” 1949, 4–5.

- 57. J. A. Gillespie, “Social Medicine, Social Security and International Health, 1940–60,” in The Politics of the Healthy Life: An International Perspective, ed. E. R. Ocaña (Sheffield, UK: European Association for the History of Medicine and Health Publications, 2002), 219–239.

- 58. Constitution of the World Health Organization, 1946, 2–3, https://archive.org/stream/WHO-constitution#page/n0/mode/2up (accessed December 18, 2017)

- 59. WHO EB9/66, World Health Organization, Executive Board, Ninth Session “Co-Operation With the International Labour Organization in the Field of Health and Social Insurance,” January 11, 1952.

- 60. “Medical Aspects of Social Security,” Chronicle of the World Health Organization 6, no. 12 (1952): 341–346; International Labour Conference. Thirty-Fifth Session, Geneva, 1952. Minimum Standards of Social Security. Fifth Item on the Agenda. Report V(a) (2) (Geneva, Switzerland: ILO, 1952), 304; ILO ILC 35-505-2, “International Labour Conference. 35th Session, Geneva, June 1952. Committee on Social Security. Second Sitting, 10 June 1952, 4.00 p.m.,” II/4.

- 61. J. Farley, Brock Chisholm, the World Health Organization, and the Cold War (Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press, 2008); R. M. Packard, “Malaria Dreams: Postwar Visions of Health and Development in the Third World,” Medical Anthropology 17, no. 3 (1997): 279–296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62. Starr, Social Transformation of American Medicine, 275–289.

- 63. Alan Derickson, “The House of Falk: The Paranoid Style in American Health Politics,” American Journal of Public Health 87, no. 11 (1997): 1836–1843; Gillespie, “Social Medicine,” 230; Starr, Social Transformation of American Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64. Birn, Nervi, and Siqueira, “Neoliberalism Redux.”.

- 65. D. Balabanova, M. McKee, and A. Mills, “Good Health at Low Cost” 25 Years on: What Makes a Successful Health System? (London, UK: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2011)