Abstract

Introduction:

Periodontitis is defined as a destructive inflammatory disease involving the supporting tissues of the teeth due to specific microorganisms which results in a progressive destruction of supporting structures of the periodontium. Obesity is excessive body fat in proportion to lean body mass, to such an extent that health is impaired. Obesity, a serious public health problem, relates to a chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and is involved in the development of obesity-linked disorders including insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. The accurate process whereby obesity can affect periodontal health is so far unclear. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between obesity (using body mass index [BMI] and waist circumference [WC]) and periodontal health and disease using various periodontal parameters.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 participants were randomly taken and were divided into two groups (fifty participants per group). The participants with BMI more than 30 were considered as obese and participants with BMI <30 were considered nonobese. WC was also measured. Gingival index (GI), pocket probing depth (PPD), gingival recession (REC), and clinical attachment level (CAL) were measured by a single examiner.

Results:

Independent t-test was performed to compare GI, probing depth, gingival recession, and clinical attachment level among obese and nonobese participants. The prevalence of periodontitis was significantly more in obese as compared to nonobese group (P < 0.05 for GI, P < 0.05 for PPD, and P < 0.031 for CAL).

Conclusion:

Strong correlation was found to exist between obesity and periodontitis. Obese participants could be at a greater risk of developing periodontal disease.

Keywords: Body mass index, gingival index, obesity, oral health, pocket probing depth, waist circumference

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis, commonly called pyorrhea, is an inflammatory infection that alters the tooth-supporting structure, leading to accelerated alveolar bone loss and if not treated, can eventually advance to tooth loss. Chronic periodontal infection is an inflammatory state that is described by a deviation in the microbial environment and composition of subgingival plaque biofilms and accelerated destruction of tooth-supporting architecture that is host mediated.[1] It has been considered as one of the extremely prevalent worldwide conditions and that it is represented as a leading public health dilemma for both developing and developed society. It abstracts among the ten biggest prevalent chronic infections. Periodontitis is a disease of multifactorial origin. Numerous systemic or local risk factors play a major role in its clinical sequences. Periodontal diseases are also influenced by various risk factors including aging, smoking, oral hygiene, socioeconomic status, genetics, race, gender, psychosocial stress, osteopenia, osteoporosis, and various other systemic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease which signifies that periodontitis does not occur merely as a consequence of plaque deposition but is also coupled with various host factors which could alter the consequence of the plaque on a particular individual.

Obesity is defined as excessive body fat in proportion to lean body mass, to such an extent that health is impaired.[2] Obesity, which is considered as a large-scale public health dilemma, is linked to a chronic low-grade systemic inflammation that affords to the evolution of obesity-related disorders including metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases.[3] In the past few decades, obesity has increased substantially among the population worldwide. It is now considered the sixth biggest crucial dangerous factor contributing to diseases worldwide, and it has been suggested that decreased life expectancy in the future may be the result of increased levels of obesity.[4] Obesity, as recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO), has been known to be one of the predisposing components to majority of chronic diseases which ranges from cardiovascular disease to cancer.[1] A superabundance of energy-dense food and reduced opportunities and encouragements for physical activity have drastically changed the lifestyle pattern of an individual.

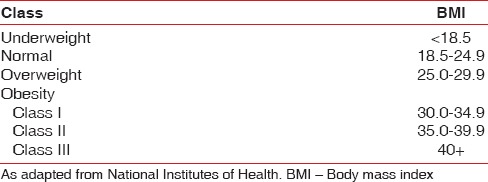

As advocated by the WHO, body mass index (BMI) can be used to measure obesity and categorize it for all adult age groups. The full classification for overweight and obesity, developed by the National Institutes of Health through an expert panel that reviewed data from approximately 394 studies, is shown in Table 1.[5]

Table 1.

Classifications for body mass index

Several researches from around the world have repeatedly shown a positive affiliation among prevalent periodontal disease and obesity. Linden et al. did not observe an affiliation among obesity in early adulthood and severity of periodontitis at the age of 60–70 years, whereas 6 years earlier in a study done by Morita et al., it was described that periodontal disease and BMI were positively associated.[4,6] Till date, most of the studies which have been carried out related to obesity were among adults and elderly people. An analytical review of Suvan et al. noticed a heterogeneity among various studies, where higher odds of periodontitis was noted among obese individual but, no studies where identified among young adults that have evaluated whether obesity directly causes periodontitis.[7] Hence, it is of great relevance to figure out this affiliation to effectively interpret the early systemic outcomes of obesity among young adults.

Hence, the need of the present research is to assess the affiliation between obesity (using BMI and waist circumference [WC]) and periodontal health and disease using various periodontal parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A descriptive cross-sectional research was carried out at the Department of Periodontology. The study period was from March 2015 to March 2016. The study was conducted after approval of Institutional Ethics Committee. In this study, enrollment of the participants was done by means of convenience sampling. The study population in the present research was preferred based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Participants above the age of 18 years

Participants with BMI >30 are considered obese

Participants with BMI <30 are considered nonobese

Participants with at least 6 natural teeth present in the oral cavity

Participants with generalized chronic periodontitis

Participants with generalized chronic gingivitis.

Exclusion criteria

Participants who had received any antibiotic therapy or any periodontal treatment at most 3 months before are included in the research

Physically or mentally challenged participants

Pregnant women and lactating mothers

Participants with any type of malignancy

Participants not willing to participate.

Sample size determination

To get 0.12 difference in mean GI between two groups at 95% confidence interval and 80% power, the sample size required for the study was 100 (50 per group). The sample size was obtained using N-Master statistical software.

Investigations were conducted by a single researcher. Intraexaminer calibration of the examiner was carried out. The data obtained were evaluated applying Kappa statistics. The coefficient of 0.86 was constructed, reflecting a high degree of agreement in the observations.

For each participant, freshly sterilized instruments were used. A total of 100 participants were enrolled in the research. Before enrollment of any participant in the study, all the participants were briefed verbally about the objective of the research. Written information regarding the study was given, and participants willing to take part in the study were enlisted and written informed consent was procured from entire study participants.

Anthropometric parameters used to assess obesity were recorded that includes measuring of the BMI and WC. BMI was measured as a person's weight, in kilograms, and divided by the square of his/her height in meters. The participants with BMI >30 were considered as obese and participants with BMI <30 were considered nonobese. WC was measured (in centimeter) at the midpoint between lower border of ribs and upper border of pelvis and is divided into two categories using the cutoff points 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women.[8] To record the measurements, weighing machine and measuring tape were used. Periodontal parameters including gingival index (GI) (Loe and Sillness, 1963), pocket probing depth (PPD), gingival recession (REC), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) were recorded. PPD was measured from marginal gingiva to the base of the pocket, gingival recession measured from cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the marginal gingiva, clinical attachment loss (CAL) from the CEJ to the base of the pocket, on the mesiobuccal, mid-buccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, midlingual, and distolingual sites of all the teeth.

Data analysis

The data obtained were coded and fed into the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS software by IBM, USA) version 16 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to account for mean and standard deviation. Independent t-test was used to compare PPD, REC, CAL, and GI among the test group (obese participants) and control group (nonobese participants). P = 0.05 was set as the level of significance.

RESULTS

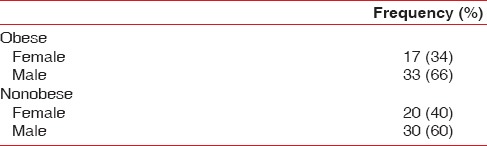

Out of fifty obese participants, 34% were females and 66% were males [Table 2], whereas out of 50 nonobese participants, 40% were females and 60% males [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of gender among obese and nonobese participants

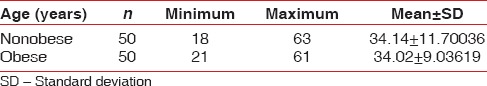

Mean age of nonobese and obese participants was calculated to be 34.14 ± 11.70 and 34.02 ± 9.03, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of mean age among obese and nonobese participants

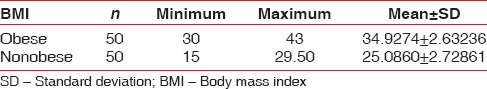

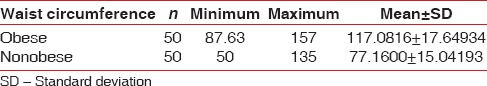

Mean BMI among obese and nonobese was 34.93 ± 2.63 and 25.09 ± 2.73, respectively [Table 4]. Whereas the mean WC among obese and nonobese was 117.08 ± 17.65 and 77.16 ± 15.04, respectively [Table 5].

Table 4.

Distribution of mean body mass index

Table 5.

Distribution of mean waist circumference

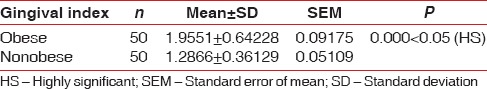

Mean GI score among obese and nonobese participants was 1.95 ± 0.64 and 1.29 ± 0.36, respectively. Mean GI score was found to be greater among obese participants and it was statistically significant with P < 0.05 [Table 6].

Table 6.

Distribution of mean gingival index score

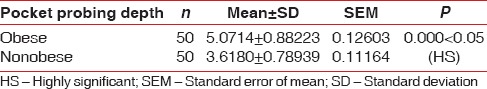

Mean probing depth values among obese and nonobese participants were 5.07 ± 0.88 and 3.62 ± 0.79, respectively. Mean probing depth values were found to be greater among obese participants and it was statistically significant with P < 0.05 [Table 7].

Table 7.

Distribution of mean pocket probing depth

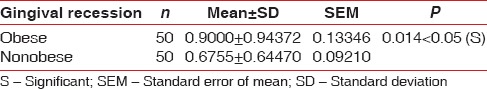

Mean gingival recession values among obese and nonobese participants were 0.9 ± 0.94 and 0.68 ± 0.64, respectively. Mean gingival recession values were found to be greater among obese participants and it was statistically significant with P < 0.014 [Table 8].

Table 8.

Distribution of mean gingival recession

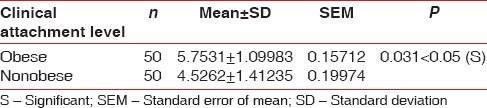

Mean clinical attachment level values among obese and nonobese participants were 5.75 ± 1.09 and 4.53 ± 1.41, respectively. Mean clinical attachment level values were found to be greater among obese participants and this was statistically significant with P < 0.031 [Table 9].

Table 9.

Distribution of clinical attachment level

DISCUSSION

Our research figures out the affiliation among obesity and periodontitis; where both states are chronic inflammatory diseases by nature, which can possibly worsen the overall systemic inflammatory response. With the emergence of periodontal medicine, it has shed light on the association between oral and systemic health and disease. In today's world, obesity has become one of the biggest significant health risks, which is chronic in nature with multifactorial etiology.

Periodontitis is caused by certain organisms resulting in a progressive destruction of the supporting structures of periodontium. The diseased periodontal tissues yield a lot of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 β, IL-6, prostaglandin E2, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which further continues periodontal destruction.

The exact mechanism(s) through which obesity may influence the periodontal health is still unclear. An affiliation among obesity and periodontitis could be explained by an array of possible likely mechanisms. Overweight participants, especially young participants, have an unhealthy dietary pattern which includes the excessive content of sugar and fat, with insufficient micronutrients. Dietary patterns of such type may increase the risk for developing periodontal disease. Excess gain of fat in early life, that is often associated with increased stress levels, may also play a role in promoting periodontal disease. Diversification in oral surroundings or small grade of chronic inflammation may be due to excess of adipose tissue. As many as fifty bioactive molecules known as adipokines are secreted by adipose cells in obese participants. The adipokines comprise hormone-like proteins (adipocytokines, adiponectin, and leptin) and classical cytokines (TNF α and IL-6).[8] The increased adipocytes and macrophages lead to the creation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 β, and IL-6. As the release of inflammatory cytokines is linked closely to a higher vulnerability to bacterial infection, increased production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines increases the host susceptibility heading for the evolution and advancement of periodontal disease.

Another probable mechanism associating obesity and periodontal disease is insulin resistance. Dietary-free fatty acids accord not alone to obesity but as well as to insulin resistance, by acceptable abolition of beta cells of the pancreas. In turn, insulin resistance also contributes to a hyperinflammatory state which is generalized, including periodontal tissue.[8]

In the present research, the occurrence of periodontitis was greater in obese participants as compared to nonobese participants. These findings are in concurrence with results obtained in a study done by Al-Zahrani et al. where it was noted that individuals with a BMI >30 kg/m2 had remarkably greater risk of periodontal disease.[9]

Mean GI score among obese and nonobese participants was 1.95 ± 0.64 and 1.29 ± 0.36, respectively. The mean GI was found to be greater among obese participants, and the difference was statistically significant with P < 0.005. In a study done by Singh et al., he had divided 45 patients into three groups and noted that the mean of GI in Group 1 (nonobese participants without systemic disease), Group 2 (obese participants without systemic disease), and Group 3 (obese participants with systemic disease [hypertension]) were 1.44, 1.78, and 1.86, respectively. There was statistically significant difference between Group 1 and Group 2 (P = 0.001).[8]

Mean probing depth values among obese and nonobese participants were 5.07 ± 0.88 and 3.62 ± 0.79, respectively, which was found to be greater among obese participants and was statistically significant with P < 0.005. In the study done by de Castilhos et al. involving examination of 720 participants, the author found that existence of periodontal pocket was not affiliated with obesity or WC.[10]

Mean clinical attachment level values among obese and nonobese participants were 5.75 ± 1.09 and 4.53 ± 1.41, respectively. It was found to be greater among obese participants and was statistically significant with P < 0.031 [Table 9]. Johanne Kongstad et al. (2008) found that obese participants had a lower odds ratio (OR) for CAL in comparison to participants with normal weight (OR: 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.36–0.99). He concluded that BMI may be inversely associated with CAL but positively related with the balance of payments.

However, despite all attempts being made to carry out a study which considers all the required parameters, for assessing obesity and periodontal disease, some limitations do exist in this study as well.

One of the limitations of this study is its research design (cross-sectional study design) which is known to hinder the establishment of a definite cause and effect relationship

Furthermore, a number of possible confounders such as socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, genetic predisposition, age, sex, stress, and smoking status associated with body weight and oral health have not been considered in this study

The individual markers and confounding factors at a molecular level that may cause obesity were not considered

To measure obesity, BMI and WC were taken into consideration in our study while several studies used wait-to-hip ratio also which was not considered in this study

Here, in this study, manual probe (UNC 15) was used to measure periodontal findings, whereas other generations of probe could have been used for better results

The sample size in this study is comparatively low to generalize the results for a large scale of population. The samples included in the present study were taken from only one institution which cannot generalize the whole population. The study can be organized on an array of population to validate the noted affiliation and to rule their level of generalization

In the present study, patient's deleterious oral habits were not taken into consideration

Investigator blinding could have been done to overcome the chance of bias. Further studies can be planned keeping in mind the shortcomings of this study.

CONCLUSION

Obesity has been suspected as a dangerous aspect for a number of conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. In the present research, the relationship between measures of overall and abdominal obesity (BMI and WC) and periodontal disease have demonstrated significant affiliation. In the era of evolving periodontal medicine, considering various factors affecting the development of chronic periodontitis has become a two-way process. The current study sheds light on the association of obesity and chronic periodontitis. Keeping in mind the limitations of the study, still, long-term longitudinal multicenter studies are required to further validate this relationship.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaffee BW, Weston SJ. Association between chronic periodontal disease and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1708–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronne LJ, Segal KR. Adiposity and fat distribution outcome measures: Assessment and clinical implications. Obes Res. 2002;10(Suppl 1):14S–21S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linden G, Patterson C, Evans A, Kee F. Obesity and periodontitis in 60-70-year-old men. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:461–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie CS. Obesity and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44:154–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita I, Okamoto Y, Yoshii S, Nakagaki H, Mizuno K, Sheiham A, et al. Five-year incidence of periodontal disease is related to body mass index. J Dent Res. 2011;90:199–202. doi: 10.1177/0022034510382548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suvan J, D’Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults. A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e381–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh MP, Chopra R, Bansal P, Dhuria S. Association between obesity & periodontitis – A clinical and biochemical study. Indian J Dent Sci. 2013;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Castilhos ED, Horta BL, Gigante DP, Demarco FF, Peres KG, Peres MA, et al. Association between obesity and periodontal disease in young adults: A population-based birth cohort. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:717–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]