Abstract

Background

Photosynthetic oleaginous microalgae are promising feedstocks for biofuels. Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) represent rich sources for engineering microalgal lipid production. The principal activity of DGATs has been defined as a single-function enzyme catalyzing the esterification of diacylglycerol with acyl-CoA.

Results

A dual-function PtWS/DGAT associated with diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum is discovered in the current study. Distinctive to documented microalgal DGAT types, PtWS/DGAT exhibits activities of both a wax ester synthase (WS) and a DGAT. WS/DGATs are broadly distributed in microalgae, with different topology and phylogeny from those of DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s. In vitro and in vivo assays revealed that PtWS/DGAT, functioning as either a WS or a DGAT, exhibited a preference on saturated FA substrate. Endogenous overexpression of PtWS/DGAT demonstrated that the DGAT activity was dominant, whereas the WS activity was condition dependent and relatively minor. Compared with the wild type (WT), overexpression of PtWS/DGAT in the diatom resulted in increased levels of total lipids (TL) and triacylglycerol (TAG) regardless of nitrogen availability. The stability and scalability of the introduced traits were further investigated at a 10-L photobioreactor, where the mutant growth resembled WT, with moderately increased productivity of TL and TAG. Furthermore, the production of wax esters increased considerably (from undetectable levels to 2.83%) under nitrogen-deplete conditions.

Conclusions

PtWS/DGAT is a bifunctional enzyme and may serve as a promising target for the engineering of microalga-based oils and waxes for future industrial use.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-018-1029-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Phaeodactylum tricornutum, WS/DGAT, TAG, Wax ester, Metabolic engineering

Background

Microalgae sequester the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, converting this gas into green chemicals for scalable production of valuable molecules ranging from therapeutic proteins to biofuels [1]. Triacylglycerol (TAG) is an energy-dense lipid and a promising source for biofuel production from microalgae [2]. However, few natural strains exhibit the demanding traits associated with feedstock for TAG accumulation and, hence, genomic and biological technologies with increased specificity for microalga-based biofuel studies have been sought [3]. Identification of the pathways and crucial enzymes that underlie the oleaginous phenotype should guide the rational genetic engineering of microalgae for the overproduction of TAG [4, 5].

The unicellular microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [6, 7], Phaeodactylum tricornutum [8–10], and Nannochloropsis sp. [11–14] have served as model species for investigating the genetic mechanism of TAG production. Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) catalyze the final and committed step in TAG biosynthesis. The function of DGATs, mainly DGAT1s and DGAT2s, has been characterized in various studies [8, 9, 12, 14–29]. Despite functional differentiation, DGATs have been defined as single-function enzymes catalyzing the esterification of diacylglycerol (DAG) with acyl-CoA [12, 30].

Similar to TAG, in a number of plants and microorganisms, wax esters serve as energy reservoir which has been regarded as potential alternative energy sources for biofuel production. A dual-function enzyme wax ester synthase/acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA):diacylglycerol acyltransferase (WS/DGAT) has been discovered in some plants and bacteria [31–33], catalyzing the final step in TAG and wax esters biosynthesis. However, WS/DGAT enzyme has been very rarely reported so far in eukaryotic microorganisms [33] and has not been discovered in microalgae. The oleaginous microalga P. tricornutum harbors a single DGAT1 and four putative DGAT2s, of which DGAT1 [8] and DGAT2B [9] have been functionally characterized in vitro. This characterization revealed a distinct substrate preference with PtDGAT1 exhibiting a preference toward saturated C16 and C18 fatty acids (FAs) [8] and PtDGAT2B exhibiting specificity on unsaturated C16 and C18 FAs [9, 10]. In P. tricornutum, we discovered a group of acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferases (designated as PtDGATX) with an identity high to WS/DGAT and low to DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s, in amino acid sequence. This suggests that the function of DGATXs differs from those of the remaining types of DGATs. However, identification of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of PtDGATX underlying TAG or wax ester metabolism remains challenging. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate PtDGATX function, substrate preference, and regulatory mechanisms in lipid biosynthesis. Distinctive substrate preferences and in-concert choreography in TAG or wax ester biosynthesis of individual DGATs are revealed. Furthermore, a genetically modified diatom with elevated lipid, wax ester, and TAG productivity is created. In particular, the engineered strains yield (although low) wax esters, a class of oleochemicals that can potentially be used for many applications in various industries [34, 35].

Results and discussion

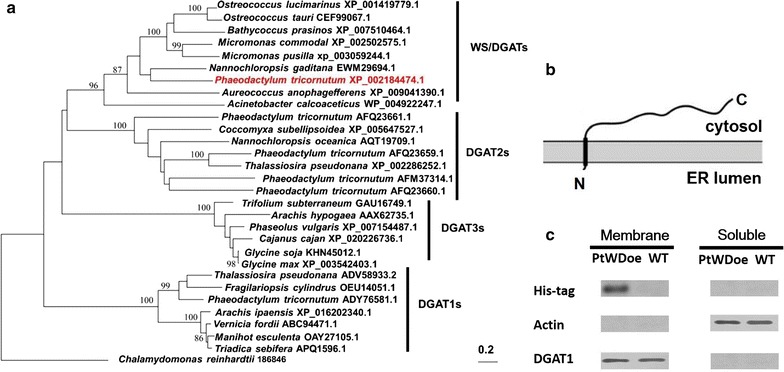

DGATX distribution in microalgae

The PtDGATX was characterized by first validating its gene model through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from cDNA and genomic DNA (Additional file 1: Dataset S1). The lack of intron suggested that the gene structure of PtDGATX was compact. The PtDGATX was distributed separately from (Fig. 1a) and was modestly similar to characterized microalgal DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s (Fig. 1a). This suggested that the origin and function of PtDGATX were distinct from those of DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s. The phylogeny of DGATXs revealed a broad presence and a high level of sequence conservation ranging from bacteria, microalgae to flowering plants (Additional file 2: Figure S1). A relatively high identity in amino acid sequence was revealed between DGATX and WS/DGAT (20%; bacterium Acinetobacter, AF529086; Additional file 2: Figure S2), which has been characterized in bacteria as a bifunctional enzyme WS/DGAT [32]. Moreover, the TIGR02946 domain of WS/DGATs [31] was present in PtDGATX. DGAT1s have at least six transmembrane domains [8] and are larger than DGAT2s, which have (in general) at least two putative transmembrane domains [36], while DGAT3s are cytosolic diacylglycerol acyltransferase in the absence of transmembrane domains [37]. PtDGATX resembled AcWS/DGAT, and was predicated to harbor a single hydrophobic transmembrane region in the N terminal (Val3-Met35) (Fig. 1b and Additional file 2: Figure S3a). This was validated by fusing the coding sequence of PtDGATX with a His tag. The fusion protein was expressed endogenously in P. tricornutum and the His-tag antibody was used to determine the localization of the PtDGATX protein via western blotting. Soluble and membrane proteins were separated and used for this blotting. Bands were absent from the soluble proteins, but a band occurred in the membrane proteins (Figs. 1c and Additional file 2: Figure S3b), suggesting that PtDGATX was a transmembrane enzyme. Altogether, in terms of topology and phylogeny, PtDGATX is more similar to WS/DGATs than to DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s.

Fig. 1.

Sequence analysis of PtDGATX. a Phylogenetic analysis of DGATs. The PDAT gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (186846) was used as the root at the outer group. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed with BLAST and CLUSTALW, respectively. Bootstrap support values were estimated using 100 pseudo-replicates. b The putative transmembrane construct of PtDGATX. The transmembrane region was analyzed by the online software TMHMM, DAS, and TMpred. c Topology analysis of PtDGATX via western blotting. Soluble and membrane proteins were separated and used for blotting. Actin and DGAT1 which were known soluble protein and membrane protein, respectively, were used as controls. N the N terminal, C the C terminal, Membrane transmembrane proteins, Soluble soluble proteins, PtWDoe the PtDGATX overexpression line of P. tricornutum, WT the wild-type P. tricornutum

PtDGATX, DGAT1, and DGAT2B: Similarities and differences

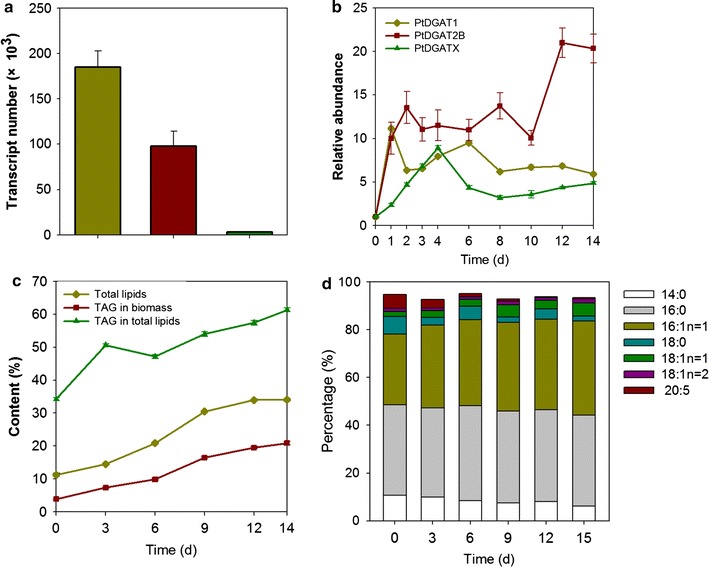

Two DGAT isoforms, i.e., PtDGAT1 [8] and PtDGAT2B [9], which are essential for TAG formation, have been functionally verified in P. tricornutum. The similarities and differences between PtDGATX and other DGAT types were determined via absolute quantitative PCR (qPCR) investigation of the transcriptional dynamics associated with DGAT isoforms in P. tricornutum. Among these three DGAT genes, DGAT1 and DGATX exhibited the highest absolute transcript level and the lowest absolute transcript level, respectively, in P. tricornutum at late logarithmic phase (Fig. 2a). The three PtDGAT genes were all upregulated under nitrogen (N)-depleted conditions, although the expression patterns of the individual DGATs were markedly different. PtDGAT1 showed transient upregulation, with its transcript levels peaking at 1 day following the onset of N depletion and declining slightly thereafter (Fig. 2b). PtDGAT2B exhibited the greatest fold change (20.3-fold). Upregulation of PtDGAT2B occurred rapidly within the first day upon N− and remained at a relatively constant level thereafter (Fig. 2b). Compared with those of PtDGAT1 and PtDGAT2B (being transcriptionally unregulated rapidly within the first day), the transcript levels of PtDGATX increased more slowly and continuously, peaking at 4 days (Fig. 2b). This suggested that, upon N−, relative to PtDGAT1 and DGAT2B, DGATX gene may contribute more to TAG synthesis in the latter stage than during the earlier stages.

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of DGATs and lipidomics of P. tricornutum following nitrogen depletion. a Absolute abundance of DGATs in wild-type P. tricornutum at late logarithmic phase. Y axis means the transcript number. The concentrations of pMD19T-PtDGAT1, pMD19T-PtDGAT2A, and pMD19T-PtWS/DGAT were determined and diluted to 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 as templates in real-time PCR for standard curve. R2 with values above 0.99 and amplification efficiencies with values above 90% were obtained for PtDGAT1, DGAT2A, and WS/DGAT genes (amplification curves and melting curves are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S4). b Transcriptional dynamics of DGATs upon nitrogen depletion. To impose N deprivation, P. tricornutum cells in the stationary phase were collected, washed, and re-suspended with N-free f/2 medium at room temperature. Samples were collected at indicated periods for transcript analysis. c Dynamics of total lipids and TAG in P. tricornutum after nitrogen depletion. d Profiles of fatty acids in TAG in P. tricornutum after nitrogen depletion

The correlation between lipid accumulation and gene regulation (Fig. 2c) was determined via lipidomic analysis. For direct comparison of the results, the same independent batches of cells were used for the transcription and lipidomic analyses. N− conditions yielded the following occurrences, namely the (i) total lipid (TL) content increased by approximately twofold (from 11 to 34%) within 14 days (Fig. 2c), (ii) TAG content increased significantly (from 3.85 to 20.87% mg DW−1, see Fig. 2c), (iii) FA profiles changed significantly, (iv) content of monounsaturated FAs (i.e., C16:1 n = 1 and C18:1 n = 1) increased markedly, whereas the content of saturated FAs (i.e., C14:0 and C18:0) and polyunsaturated (i.e., C20:5) FAs decreased (Fig. 2d), and (v) many TAG molecular species increased considerably with the transcript increase of the three DGATs. The lipid composition changed substantially with an increased percentage of TAG in TLs (from 34.22 to 61.33%; Fig. 2c). Regardless of N availability, C16:0 and C16:1 in P. tricornutum (Fig. 2d) constituted the main FAs of TAG. The transient or progressive upregulation of the DGATs may have resulted in most of the TAG formed during N depletion. Therefore, we assumed that the upregulation of these DGAT genes occurs concomitantly with the increase in TAG under N− conditions. PtDGAT1 and PtDGAT2B play (in general) a major role in TAG synthesis, whereas PtDGATX may play only a minor role. However, PtDGATX is actively involved in the response to N− conditions and appears crucial in the late stage under N− periods, whereas the role of PtDGATX remains unclear.

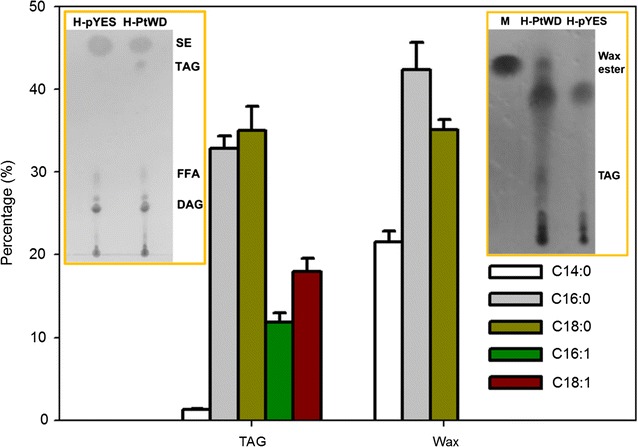

Functional rescue of TAG-deficient yeast by PtWS/DGAT

To verify the role of PtDGATX, the gene was expressed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae H1246 that is deficient in TAG biosynthesis. TLC revealed that TAG was absent from the H-pYES strains (H1246 cells harboring an empty pYES2 vector) and a prominent spot corresponding to TAG in the transformants harboring the pYES2-PtDGATX vector (H1246-PtDGATX) was observed (Table 1 and Fig. 3 left inset). Meanwhile, a substantial amount of wax ester was detected in H1246-PtDGATX (Table 1 and Fig. 3 right inset), indicating the dual function of PtDGATX (hereafter PtWS/DGAT) with activities of both WS and DGAT. In H1246-PtWS/DGAT, TAG and wax ester accounted for ~ 10.51 and 5.17%, respectively, of the TLs. C16:1 and C18:1 were the dominant FA species in TLs. However, C16:0 and C18:0 FAs were the principle components of TAG and C14:0, C16:0, and C18:0 FAs were the main FAs in the wax ester (Table 1 and Fig. 3). This indicated that PtWS/DGAT, functioning as either a WS or a DGAT, exhibits a preference on saturated FA substrates in yeast. Moreover, unsaturated FAs (i.e., C16:1 and C18:1 FAs) were detected in TAG, but were absent from the ester, suggesting a difference in substrate preference of PtWS/DGAT functioning as a WS or a DGAT. In addition, the number of TLs accumulated by H1246-PtWS/DGAT was almost triple the number accumulated by the controls (H-pYES strains). This suggested that in vivo manipulating PtWS/DGAT would yield increased lipid production in the oleaginous P. tricornutum.

Table 1.

Fatty acid content of total lipid in S. cerevisiae

| Fatty acid | H1246-pYES2 (% of TFA) | H1246-PtWS/DGAT (% of TFA) | H1246-PtWS/DGAT (% of TAG) | H1246-PtWS/DGAT (% of wax ester) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12:0 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | – | – |

| C14:0 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 1.33 ± 0.03 | 21.56 ± 1.29 |

| C16:0 | 10.81 ± 0.76 | 16.84 ± 1.15 | 32.81 ± 1.57 | 42.37 ± 3.25 |

| C18:0 | 9.90 ± 0.78 | 14.36 ± 1.03 | 35.04 ± 2.86 | 35.14 ± 1.24 |

| C14:1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | – | – |

| C16:1 | 29.93 ± 1.37 | 25.31 ± 2.14 | 11.84 ± 1.14 | – |

| C17:1 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | – | – |

| C18:1 | 47.56 ± 1.95 | 41.37 ± 2.35 | 17.97 ± 1.56 | – |

| C18:2 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | – | – |

| C20:1 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | – | – |

| Content | 3.25 ± 0.39 (of DW) | 9.55 ± 1.21 (of DW; 194%↑) | 10.51 ± 0.94 (of TL) | 5.17 ± 0.28 (of TL) |

TL total lipid, DW dry weight

Fig. 3.

Lipid analysis of the recombinant S. cerevisiae H1246. The FA contents of TAG and wax ester were analyzed by GC–MS. M cetylpalmitate, H-PtWD H1246-PtDGATX, H-pYES H1246-pYES2, SE sterol ester, TAG triacylglycerol, FFA free fatty acids, DAG diacylglycerol

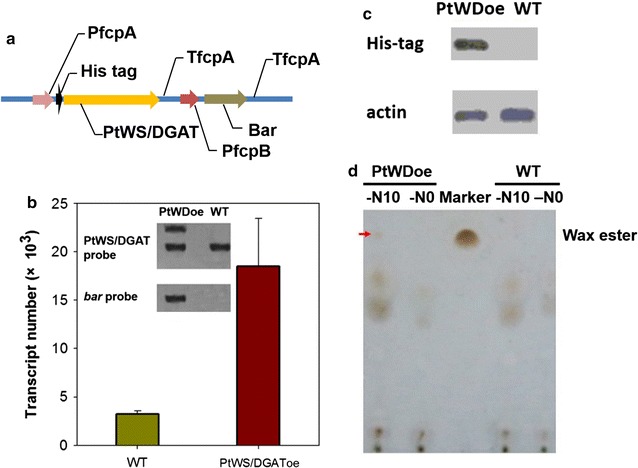

In vivo TAG-synthetic activities of PtWS/DGAT revealed via endogenous overexpression

To probe the endogenous function, PtWS/DGAT was overexpressed in P. tricornutum (PtWS/DGAToe). The PtWS/DGAT overexpression vector harbored a full-length PtWS/DGAT gene and a basta resistance (bar) gene. The PtWS/DGAT gene fused with a His tag was driven by the fcpA promoter (PfcpA) and terminated by the fcpA terminator (TfcpA) region. Moreover, the bar gene expression was driven by the fcpB promoter (PfcpB) and terminated with the fcpA2 terminator (TfcpA2) (Fig. 4a). Transformants were selected on f/2 plates supplemented with basta. The desired in vivo function of each of these promoters and terminators in P. tricornutum was individually validated. Specifically, the transcriptional level of the PtWS/DGAT gene was determined by the absolute quantitative PCR. Under N-replete (N+) conditions, a significant increase (4.5-fold) of PtWS/DGAT transcription occurred in the PtWS/DGAToe cells relative to that occurring in the wild-type cells (WT) (Fig. 4b). The integration of the PtWS/DGAT vector was validated via Southern blotting, as indicated by a clear band using bar gene as a probe (Fig. 4b inset). Using the PtWS/DGAT gene as a probe during blotting revealed two bands in PtWS/DGAToe and a single band in WT (Fig. 4b inset). This was consistent with a single integration of the exogenous PtWS/DGAT gene into the alga chromosome. Furthermore, in vivo expression of the PtWS/DGAT protein was validated by using His-tag antibodies to detect the PtWS/DGAT-6 × His fusion protein via immunoblotting. A band was detected in PtWS/DGAToe, whereas no signal was detected in WT (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Overexpression PtWS/DGAT in P. tricornutum. a Construct of the P. tricornutum expression vector. PfcpA, promoter of fcpA gene; His tag, 6 × His tag; TfcpA, terminator of fcpA gene; PfcpB, promoter of fcpB gene; bar, the herbicide basta-resistant gene. b Quantitative transcriptional levels of PtWS/DGAT in the PtWS/DGAToe and WT cells. Inset, Southern blotting of PtWS/DGAToe with the PtWS/DGAT gene probe or the bar gene probe. c Immunodetection of PtWS/DGAT-6 × Hisfusion protein with His-tag antibodies. d TLC analysis of wax ester in PtWS/DGAToe. PtWDoe PtWS/DGAT overexpression P. tricornutum, WT the wild-type P. tricornutum, −N0 nitrogen replete culture, −N10 nitrogen depletion for 10 days. TAG and wax ester were separated from total lipid by scraping their spots from TLC plates. The FA composition of TAG and wax ester was analyzed by GC–MS

Compared with those of WT, the respective TL content and TAG content of the PtWS/DGAToe increased by (i) 21 and 40% under N+ conditions and (ii) 10 and 25% following N− (see Table 2). The levels of unsaturated FAs (e.g., C16:1 n − 1, C16:1 n − 2, and C18:1 n − 1 FAs) decreased and the levels of saturated FAs (especially the C14:0, C16:0, and C18:0 FAs) increased slightly under both N+ and N− conditions (Table 2). This may have resulted from the substrate preference of PtWS/DGAT on saturated FAs. Therefore, regardless of N availability, PtWS/DGAT exhibited a DGAT activity with a preference on saturated FAs. In contrast, under N−, the WS activity of PtWS/DGAT seemed to be higher in the late stage (than in the early stages). Wax ester was absent from either WT or the PtWS/DGAToe cells under N+ conditions. In contrast, following prolonged N−, a small amount (0.53 ± 0.05% of TLs) of wax ester occurred in the PtWS/DGAToe, but was absent from WT, although a large amount of lipids was loaded for TLC analysis (Fig. 4d). Hence, although the activity as WS is condition dependent and relatively minor, PtWS/DGAT exhibits activities in both wax ester synthesis and TAG synthesis in P. tricornutum.

Table 2.

Fatty acid content of TAG in the recombinant P. tricornutum

| Fatty acid | Nitrogen repletion | Nitrogen depletion for 10 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (% of TAG) | PtWS/DGAToe (% of TAG) | Wild type (% of TAG) | PtWS/DGAToe (% of TAG) | |

| Saturated fatty acid | ||||

| C14:0 | 10.73 ± 0.83 | 11.07 ± 0.64 | 6.27 ± 0.23 | 7.36 ± 0.58 |

| C15:0 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.04 |

| C16:0 | 32.84 ± 2.45 | 34.47 ± 3.49 | 40.04 ± 3.39 | 43.82 ± 2.93 |

| C18:0 | 7.31 ± 0.34 | 8.01 ± 0.48 | 3.07 ± 0.04 | 5.31 ± 0.21 |

| C19:0 | 1.26 ± 0.21 | 1.71 ± 0.30 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.03 |

| C20:0 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| C22:0 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.52 ± 0.05 |

| C24:0 | 3.73 ± 0.39 | 4.01 ± 0.23 | 3.24 ± 0.27 | 2.12 ± 0.72 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acid | ||||

| C16:1 n − 1 | 29.56 ± 2.32 | 28.06 ± 3.74 | 36.85 ± 2.46 | 34.25 ± 2.93 |

| C16:1 n − 2 | 1.11 ± 0.32 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 1.53 ± 0.17 | 1.20 ± 0.08 |

| C18:1 n − 1 | 2.11 ± 0.34 | 1.71 ± 0.25 | 4.43 ± 0.48 | 2.34 ± 0.40 |

| C18:1 n − 2 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 1.27 ± 0.34 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| C24:1 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acid | ||||

| C16:3 | 1.55 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.09 |

| C20:3 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| C20:4 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| C20:5 (EPA) | 5.86 ± 0.11 | 4.59 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| TAG (% of DW) | 3.85 ± 0.22 | 5.39 ± 0.15 (40%↑) | 18.27 ± 1.48 | 22.78 ± 1.59 (25%↑) |

| Total lipid (% of DW) | 11.25 ± 1.17 | 13.61 ± 1.84 (21%↑) | 32.64 ± 2.51 | 36.18 ± 2.38 (10%↑) |

DW dry weight, EPA eicosapentaenoic acid, TAG triacylglycerol, ↑ increased

Engineering PtWS/DGAT for increased lipid productivity

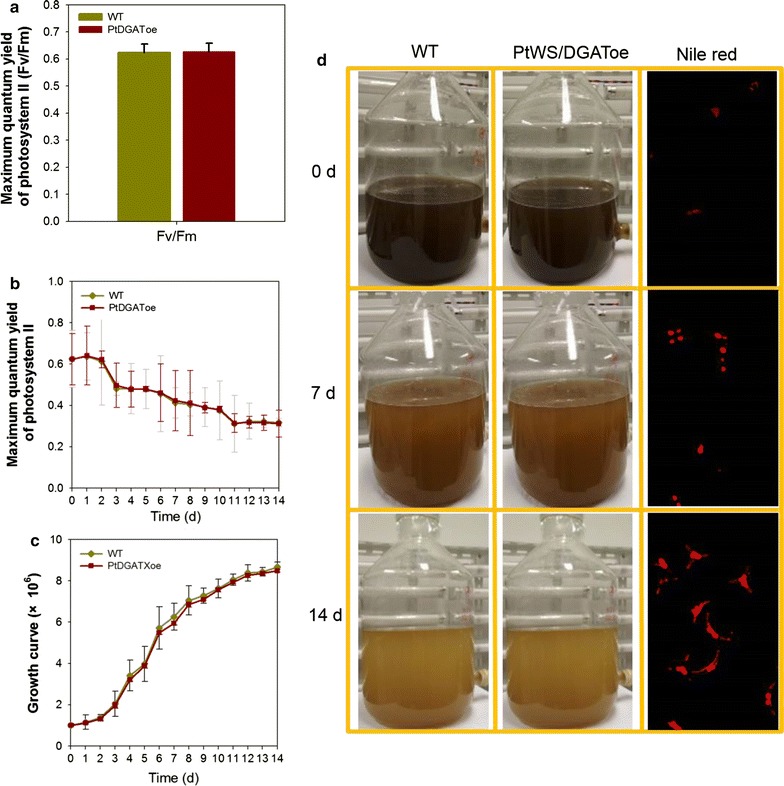

The in vitro and in vivo evidence indicated that perturbation on PtWS/DGAT resulted in increased production of TLs and TAG. However, increased cellular lipid biosynthesis occasionally leads to decreased growth, thereby neutralizing the overall lipid productivity [2]. Biomass accumulation (i.e., growth rate of microalgal strains) is thus crucial for determining the lipid productivity. Therefore, to determine whether the genetically modified (GM) P. tricornutum cells can be exploited for enhanced lipid production, the photosynthetic performance of both WT and PtWS/DGAToe was tracked under either N+ or 14-day N− conditions. Under N+ conditions, both lines demonstrated a high Fv/Fm value (the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II, approximately 0.62, which implies a fit growth condition; a typical result is shown in Fig. 5a). Upon nitrogen depletion, although Fv/Fm values of both lines were decreased, barely any difference was observed between WT and the GM strains (Fig. 5b and Additional file 3 Table S2). Consistently, the growth of the two lines was very similar under the explored conditions (monitored by detecting cell numbers daily; see Fig. 5c for growth under N+ conditions and see Additional file 2: Figure S5 for that under both N+ and N− conditions). Moreover, the dry weight (DW) of PtWS/DGAToe strains (397.50 ± 16.25 mg L−1) was determined after fourteen-day nitrogen starvation which was similar to that of WT (398.75 ± 26.25 mg L−1) and the DW of both was comparable to the levels of documented P. tricornutum strains (Table 3) [38].

Fig. 5.

Assessment of the production performance of PtWS/DGAToe. a Typical results of photosynthetic measurements of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe strains under nitrogen repletion conditions. b Comparison of maximum quantum yield of photosystem II of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe strains under nitrogen depletion conditions. c Growth of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe lines under nitrogen repletion conditions. d Image of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe lines following nitrogen depletion in a 10-L photobioreactor. Only typical results of Nile red staining are shown in the right column since no significant difference is observed between WT and the PtWS/DGAToe cells. PtWS/DGAToe, PtWS/DGAT overexpression P. tricornutum

Table 3.

Productivity comparison of P. tricornutum WT and PtWS/DGAToe lines cultured in a 10-L PBR following nitrogen deprivation for fourteen days

| Wild type (mg L−1day−1) | PtWS/DGAToe (mg L−1day−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dry weight | 28.5 ± 1.9 | 28.4 ± 1.2 (0.3%↓) |

| Total lipid | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 10.5 ± 0.6 (13.5%↑) |

| Triacylglycerol | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.3 (18.4%↑) |

| Wax ester | 0 | 0.8 ± 0.1 (↑) |

↑ increased, ↓ decreased

Combined with the elevated lipid and TAG content, this indicated that GM P. tricornutum cells were quite capable of photoautotrophic growth, absorbing CO2 and producing (especially) biomass, lipids, and TAG. The stability and scalability of the GM P. tricornutum were further determined by evaluating the life cycle performance in a 10-L photobioreactor (PBR) (Fig. 5d). The growth rate of the mutant under nitrogen repletion conditions was identical to that of WT, reaching a biomass productivity of 28.4 mg L−1 day−1 (See “Methods” for details). The biomass and lipid content were determined for both WT and GM P. tricornutum cultivated in nitrogen-free f/2 medium in PBR for 14 days. Compared with those of WT, the respective TL content and TAG content of the PtWS/DGAToe increased by 13.8 and 18.4% (371.1 mg g−1 DW TL and 226.4 mg g−1 DW TAG in PtWS/DGAToe) (Table 3), corresponded to a TAG productivity of 6.4 mg L−1 day−1 (an 18.4% increase relative to that of 5.4 mg L−1 day−1of WT). Moreover, following prolonged N− conditions, a considerable amount of wax ester (from undetectable levels to 28.3 mg g−1 DW) was also generated. Although the productivity remains to be improved, our results provide insight into the customized production of different high-value chemicals via engineering of a single gene [39].

Conclusions

We have discovered in diatom P. tricornutum a dual-function WS/DGAT which has previously only been characterized in bacteria and plants. Distinctive to DGAT1s, DGAT2s, and DGAT3s, PtWS/DGAT exhibited activities of both wax ester and TAG biosynthesis. Moreover, PtWS/DGAT, functioning as either a WS or a DGAT, exhibited a preference on saturated FA substrates. Overexpression of PtWS/DGAT endogenously yielded wax under N− conditions and increased production of TLs and TAG (relative to WT) under both N+ and N− conditions. Scale-up cultivation of GM diatom strains yielded increased production of TLs, TAG, and wax esters, without compromising cell growth. These findings improve our understanding of the origin, function, and cellular properties of DGATs in TAG biosynthesis and have important implications for the rational engineering of microalga-based oils and waxes for future industrial use.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

The P. tricornutum strains were kindly donated by Prof. Mingyan Yin of the Key Laboratory of Experimental Marine Biology, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. P. tricornutum was grown as previously described [3], i.e., at 23 °C under a 40–50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light with a 12/12 h light:dark photoperiod. To impose N deprivation, P. tricornutum cells in the stationary phase (8.5 × 106 cell mL−1) were collected, washed, and re-suspended in nitrogen-free f/2 medium. Samples were collected at indicated periods for transcript and lipid analysis [40]. For the scaled up cultivation of the diatom, 10-L cylinder glass bottles (50 cm diameter and 70 cm height) were used. Cells with an initial concentration of 5 × 106 cell mL−1 were cultured using a continuous filtered gas at 1.3 m3 min−1 and 40–50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 illumination with a 12/12 h light:dark photoperiod. The biomass productivity was calculated 7 days later using the following formula:

where DWs is the DW of cells at sampled time point, DWi is the DW of initial culture, T is the duration of culture period, and V is the volume of algal culture. Afterward, cells were collected, washed, and re-suspended in nitrogen-free f/2 medium. Lipid measurements were conducted after 14 days.

Phenotyping and Nile red staining

The growth of microalgae was monitored by measuring the turbidity (OD750) or cell number at indicated intervals. The chlorophyll fluorescence parameter was measured with Diving PAM (WALZ, Germany). The lipid accumulation was monitored by Nile red staining. P. tricornutum cultures (approximately 4 × 106 cells) at indicated time points were harvested, stained with 1% (v/v) Nile Red (0.5 mg mL−1 in dimethylsulfoxide), incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and immediately observed by Laser scanning confocal microscopy with an excitation filter at 480 nm (FluoViewFV1000, Olympus, Japan).

Sequence analysis of PtWS/DGAT

Sequence analysis and comparison were undertaken in accordance with previous reports [41]. In brief, sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed with BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and CLUSTALW, respectively [42]. Bootstrap support values were estimated using 100 pseudo-replicates. The Conserved Domain Database (CDD; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/), Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search) and SMART (http://smart.emblheidelberg.de/) databases were used to search for structurally conserved domains within specific proteins. The transmembrane region was analyzed by the software TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/), DAS (http://www.sbc.su.se/~miklos/DAS/), and TMpred (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html). The complete amino acid sequence of PtDGATX protein was submitted in the software online and the probable transmembrane regions were shown.

Gene expression analysis

Genomic DNA, total RNA extraction, and reverse transcription were performed as previously described [3, 40, 41]. Total RNA was extracted and purified with the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega) and then subjected to genomic DNA digestion and reverse transcription using a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara) [40, 41].

Relative qPCR was performed in two steps as given in our earlier description [40]. First, 0.5 μg RNA was mixed with 2 μL of 4×g DNA wiper Mix and Nuclease-free H2O was added to a final volume of 8 μL. The mixture was kept at 42 °C for 2 min. Second, 2 μL of 5 × HiScript II Q RT SuperMix IIa was added to the above mix. Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, USA) with a program of 25 °C for 10 min, 50 °C for 30 min, and 85 °C for 5 min. The 10 μL RT reaction mix was then diluted with 10 μL nuclease-free water and held at − 20 °C. Real-time PCR was performed using LightCycler® 480 II Real-time PCR Instrument (Roche, Swiss) with 10 μL PCR reaction mixtures including 1 μL of cDNA, 5 μL of 2 × QuantiFast® SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Germany), 0.2 μL of forward primer, 0.2 μL of reverse primer, and 3.6 μL of nuclease-free water. Reactions were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. At the end of the PCR cycles, melting curve analysis was performed. Each sample was run in triplicate. The expression levels of mRNAs were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The mRNA expression level was normalized using the 18S gene as the internal control [43].

For absolute qPCR, RT reaction was conducted following the instruction of Fast Quant RT Kit KR106 (with gDNase; Tiangen, China). The total RNA (500–1000 ng) in 8 μL RNAase-free H2O was preheated in 65 °C for 5 min and transferred to ice immediately, mixed with 2 μL 5×g-DNA buffer (containing g-DNase) in 42 °C for 3 min, and transferred to ice immediately. The solution was then mixed with 10 μL premixed buffer containing primers and FastQuant RT Enzyme. RT reaction was performed in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, USA) at 42 °C for 15 min, 95 °C for 3 min, and 4 °C for 10 min. PtDGAT1, PtDGAT2A, and PtWS/DGAT genes were amplified and cloned into pMD19T vector (TAKARA, China). The concentrations of vectors pMD19T-PtDGAT1, pMD19T-PtDGAT2A, and pMD19T-PtWS/DGAT were measured with Nanodrop ND2000 (Thermo, USA), and diluted to 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 as templates for standard curve. The qPCR was performed using ABI7500 (ABI, USA) with a 25 μL PCR reaction mixture (included 1 μL of cDNA, 12.5 μL Bestar SybrGreen Qpcrmaster mix (DBI Bioscience, Germany), 0.25 μL of forward primer, 0.25 μL of reverse primer, and 11 μL of nuclease-free water). Reactions were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. All primers were validated by PCR, sequencing, and gel electrophoresis where a single and clear band was observed for each pair of primers (Additional file 2: Figure S4a). Amplification curves and melting curves are shown in Additional file 2: Figure S4b. As for absolute qPCR, R2 with values above 0.99 and amplification efficiencies with values above 90% were obtained for PtDGAT1, DGAT2A, and WS/DGAT genes (Additional file 2: Figure S4c).

Gene cloning and expression in S. cerevisiae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain H1246 (relevant genotype: MATa ADE2-1can1–100 ura3-1 are1-D::HIS3 are2-D::LEU 2 dga1-D::KanMX4 Iro1-D::TRP1 containing knockouts of DGA1, LRO1, ARE1, and ARE2) was kindly donated by Prof. Sten Stymne (Scandinavian Biotechnology Research, Alnarp, Sweden). S. cerevisiae H1246 was maintained in a YPD medium at 30 °C and manipulated as previously described [44, 45]. PtWS/DGAT cDNA was cloned and inserted into the yeast expression vector pYES2 (Invitrogen). The recombinant PtWS/DGAT constructs were transformed into the TAG-deficient S. cerevisiae strain H1246 (Δdga1Δlro1Δare1Δare2) using an S. cerevisiae EasyComp TM transformation kit (Invitrogen), as described in our previous studies [44, 45]. Prior to transformation, yeast cells were cultivated in 1% (w⁄v) yeast extract, 2% (w⁄v) peptone, and 2% (w⁄v) glucose (YPD medium) at 30 °C. H1246-pYES cells harboring the empty pYES2 vector were used as negative controls. Transformants were selected via uracil prototrophy on a yeast synthetic minimal-defined medium (SC) lacking uracil (Invitrogen). For functional expression, a minimal selection medium containing 1% (w⁄v) raffinose and 2% galactose (w/v) was inoculated with the PtWS/DGAT transformants and incubated at 22 °C for 3–5 days. The induced cells were tested for the presence of PtWS/DGAT by PCR, and its expression by RT-PCR (see Additional file 3: Table S1 for PCR primers). Cells with positive results (H1246-PtWS/DGAT) were harvested via centrifugation, washed twice with 0.1% (w⁄v) NaHCO3, freeze-dried, and used for lipid analysis.

Expression vector design and P. tricornutum transformation

The PtWS/DGAT overexpression vector harbored a full-length PtWS/DGAT gene and a basta resistance (Bar) gene, each of which was driven by an endogenous promoter and terminated by an endogenous terminator (Fig. 4a). The PtWS/DGAT gene was driven by the Fucoxanthin-chlorophyll protein A promoter (PfcpA) and terminated by the Fucoxanthin-chlorophyll protein A1 termination (TfcpA) region. Expression of the Bar gene was driven by the Fucoxanthin-chlorophyll protein B promoter (PfcpB) and terminated with TfcpA terminator. The fragments were cloned with primers harboring indicated restriction enzyme cutting sites (Additional file 3: Table S1), while the commercial vector pBluescript SK(+) was employed as an acceptor vector. The PtWD/DGAT gene was inserted into the XbaI and SacII sites, while the PfcpA fragment and the TfcpA fragment were inserted into the position between the SalI and HindIII sites and between the SmaI and BamHI sites, respectively. On the other hand, the bar gene was inserted into the EcoRV and PstI sites, while the PfcpB fragment and the TfcpA2 fragment were ligated into the SpeI and XbaI sites and SacII and SaxI sites, respectively.

Bombardment transformation was performed using a GJ-1000 apparatus (Ningbo, China) with a field strength and shunt resistance of 1350 psi and 9 cm, respectively. Afterward, the cells were immediately transferred onto f/2 plates with 15 μg mL−1 basta and 150 μg mL−1 kanamycin, and incubated at 23°C with continuous illumination of 40–50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 until transformants were observed. Individual colonies were picked and transferred into fresh f/2 plates with selective agents. The transformants were subjected to successive passages and maintained in a liquid f/2 medium.

Immunodetection

The stable integration of the transforming cassette into the chromosome and expression were validated via Southern blotting and western blotting, respectively. For Southern blotting, no less than 1 μg genomic DNA was digested with HindIII and analyzed by DNA gel blotting using nonradioactive DIG-containing PtWS/DGAT or Bar gene probes (PCR DIG probe synthesis kit; Roche Diagnostics). The PtWS/DGAT or Bar gene probes were labeled with DIG-dUTP using corresponding primers (Additional file 3: Table S1). His-tag antibodies were used to detect the expression fusion protein of PtWS/DGAT-His-tag. To determine whether PtWS/DGAT has a transmembrane motif, the PtWS/DGAToe cells at the log phase were harvested and soluble and membrane proteins were used for (previously described) immunodetection [37]. In brief, cell pellets were re-suspended in 10 mL extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mg mL−1 leupeptin, and 0.25 M sucrose) and broken by an ultrasonic cell disrupter (SCIENTZ-ID, China) at 100 W for 20 min. The soluble and membrane proteins were separated via centrifugation at 18,000 g for 20 min (Beckman Optimatm L-100 XP, America). Afterward, each protein was immunoblotted with His-tag antibodies. For each sample, 35–40 μg protein was loaded and the Coomassie staining is shown in Additional file 2: Figure S6.

Lipid extraction and analysis

Cells were harvested via centrifugation at 4 °C and 5000 g min−1 for 5 min, freeze-dried, and used for lipid analysis. Lipid extraction and TLC analysis of the neutral lipids were performed as described by Yoon [7]. For TLC analysis, a mixture of normal hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (70/30/1 by volume) was used as the mobile phase for TAG analysis. Wax ester analysis was performed using petroleum ether/diethyl ether/acetic acid (90:10:1). TAG and wax ester were detected by iodine vapor and 50% sulfuric acid, respectively. The lipid quantification was performed by GC–MS, as previously described [14, 46].

Statistical analysis

To ensure reproducibility, the experiments were all performed with at least three biological triplicates. Each of the presented values corresponds to a mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package (http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/). Furthermore, the paired-samples t test was performed and differences were considered statistically significant at P values of < 0.05.

Additional files

Additional file 1. PtWS DGAT cDNA sequence.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis of DGATXs. Figure S2. Multiple protein-sequence alignments of DGATXs. Figure S3. Representative topology of DGAT1s, DGAT2s, DGAT3s and WS/DGAT. Figure S4. Assessment of primers of PtDGAT1, DGAT2A, and PtWS/DGAT genes for qPCR. (a) Gel electrophoresis of the PCR product using PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and PtWS/DGAT primers. (b) Amplification curves and melting curves of PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and PtWS/DGAT primers. (c) Standard curve for absolute qPCR using vectors pMD19T-PtDGAT1, pMD19T-PtDGAT2A and pMD19T-PtWS/DGAT as templates. The vector concentrations were determined by Nanodrop ND2000 and diluted to 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 for standard curve. R2 with values above 0.99 and amplification efficiencies with values above 90% were obtained for PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and WS/DGAT genes. Figure S5. Growth of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe lines under nitrogen repletion conditions (black bar) followed by nitrogen starvation (white bar).

Additional file 3: Table S1. Primers used in this study. Table S2. The Fv/Fm of WT and PtWS/DGAToe P. tricornutum lines following nitrogen deprivation for fourteen days.

Authors’ contributions

YC, SQ, and YL planned the experiments. YC, JZ, and YW performed the experiments. YC analyzed the data. YC and YL wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge with apologies that many excellent studies could not be cited due to space limitations. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable improvement to this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript (and its Additional files 1, 2, 3).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFB0601001), National Nature Science Foundation of China (41406192 and 41176144), Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (317010), Project of Innovation & Development of Marine Economy (2017-285), Project of State Key Laboratory of Marine Resource Utilization in South China Sea (2016005), and Foundation of Hainan University (KYQD1561).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- bar

a basta resistance gene

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DGATs

acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferases

- DW

dry weight

- FAs

fatty acids

- GC–MS

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- GM

genetically modified

- H-pYES strains

H1246 cells harboring an empty pYES2 vector

- H1246-PtDGATX

the H1246 transformants harboring the pYES2-PtDGATX vector

- N−

N-deplete conditions

- N+

N-replete conditions

- PBR

photobioreactor

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PfcpA

a fcpA promoter

- PfcpB

a fcpB promoter

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TfcpA

a fcpA terminator

- TfcpA2

a fcpA2 terminator

- TL

total lipid

- WS

wax ester synthase

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-018-1029-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Song Qin, Email: sqin@yic.ac.cn.

Yandu Lu, Email: ydlu@hainu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zaimes GG, Khanna V. Microalgal biomass production pathways: evaluation of life cycle environmental impacts. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:88–88. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajjawi I, Verruto J, Aqui M, Soriaga LB, Coppersmith J, Kwok K, Peach L, Orchard E, Kalb R, Xu W, Carlson TJ, Francis K, Konigsfeld K, Bartalis J, Schultz A, Lambert W, Schwartz AS, Brown R, Moellering ER. Lipid production in Nannochloropsis gaditana is doubled by decreasing expression of a single transcriptional regulator. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:647. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan Q, Zhou W, Wang S, Li X, Xie Z, Wang J, Jiang J, Lu Y. A customized contamination controlling approach for culturing oleaginous Nannochloropsis oceanica. Algal Res. 2017;27:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2017.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merchant SS, Kropat J, Liu B, Shaw J, Warakanont J. TAG, you’re it! Chlamydomonas as a reference organism for understanding algal triacylglycerol accumulation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2012;23:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Y, Xu J. Phytohormones in microalgae: a new opportunity for microalgal biotechnology. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Moellering ER, Liu B, Johnny C, Fedewa M, Sears BB, Kuo MH, Benning C. A galactoglycerolipid lipase is required for triacylglycerol accumulation and survival following nitrogen deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4670–4686. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon K, Han D, Li Y, Sommerfeld M, Hu Q. Phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase is a multifunctional enzyme involved in membrane lipid turnover and degradation while synthesizing triacylglycerol in the unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3708–3724. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guihéneuf F, Leu S, Zarka A, Khozin-Goldberg I, Khalilov I, Boussiba S. Cloning and molecular characterization of a novel acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1-like gene (PtDGAT1) from the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. FEBS J. 2011;278:3651–3666. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong Y, Zhang J, Guo X, Wan X, Liang Z, Hu CJ, Jiang M. Identification and characterization of PtDGAT2B, an acyltransferase of the DGAT2 acyl-coenzyme A: diacylglycerol acyltransferase family in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niu Y, Zhang M, Li D, Yang W, Liu J, Bai W, Li H. Improvement of neutral lipid and polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis by overexpressing a type 2 diacylglycerol acyltransferase in marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Marine Drugs. 2013;11:4558–4569. doi: 10.3390/md11114558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Ning K, Li J, Hu J, Han D, Wang H, Zeng X, Jing X, Zhou Q, Su X, Chang X, Wang A, Wang W, Jia J, Wei L, Xin Y, Qiao Y, Huang R, Chen J, Han B, Yoon K, Hill RT, Zohar Y, Chen F, Hu Q, Xu J. Nannochloropsis genomes reveal evolution of microalgal oleaginous traits. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zienkiewicz K, Zienkiewicz A, Poliner E, Du Z-Y, Vollheyde K, Herrfurth C, Marmon S, Farré EM, Feussner I, Benning C. Nannochloropsis, a rich source of diacylglycerol acyltransferases for engineering of triacylglycerol content in different hosts. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:8. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei H, Shi Y, Ma X, Pan Y, Hu H, Li Y, Luo M, Gerken H, Liu J. A type-I diacylglycerol acyltransferase modulates triacylglycerol biosynthesis and fatty acid composition in the oleaginous microalga, Nannochloropsis oceanica. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:174. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0858-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xin Y, Lu Y, Lee YY, Wei L, Jia J, Wang Q, Wang D, Bai F, Hu H, Hu Q, Liu J, Li Y, Xu J. Producing designer oils in industrial microalgae by rational modulation of co-evolving type-2 diacylglycerol acyltransferases. Mol Plant. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jako C, Kumar A, Wei Y, Zou J, Barton DL, Giblin EM, Covello PS, Taylor DC. Seed-specific over-expression of an Arabidopsis cDNA encoding a diacylglycerol acyltransferase enhances seed oil content and seed weight. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:861–874. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone SJ, Levin MC, Farese RV. Membrane topology and identification of key functional amino acid residues of murine acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40273–40282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, Fan J, Taylor DC, Ohlrogge JB. DGAT1 and PDAT1 acyltransferases have overlapping functions in Arabidopsis triacylglycerol biosynthesis and are essential for normal pollen and seed development. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3885–3901. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner M, Hoppe K, Czabany T, Heilmann M, Daum G, Feussner I, Fulda M. Identification and characterization of an acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2) gene from the microalga O. tauri. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Siloto RM, Snyder CL, Weselake RJ. Functional and topological analysis of yeast acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2, an endoplasmic reticulum enzyme essential for triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13115–13126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turchetto-Zolet AC, Maraschin FS, Morais GL, Cagliari A, Andrade CM, Margis-Pinheiro M, Margis R. Evolutionary view of acyl-CoA diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT), a key enzyme in neutral lipid biosynthesis. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyle NR, Page MD, Liu B, Blaby IK, Casero D, Kropat J, Cokus SJ, Hong-Hermesdorf A, Shaw J, Karpowicz SJ. Three acyltransferases and nitrogen-responsive regulator are implicated in nitrogen starvation-induced triacylglycerol accumulation in Chlamydomonas. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15811–15825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JE, Smith AG. A look at diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) in algae. J Biotechnol. 2012;162:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Siloto RM, Lehner R, Stone SJ, Weselake RJ. Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase: molecular biology, biochemistry and biotechnology. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:350–377. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banaś W, Sanchez Garcia A, Banaś A, Stymne S. Activities of acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) and phospholipid: diacylglycerol acyltransferase (PDAT) in microsomal preparations of developing sunflower and safflower seeds. Planta. 2013;237:1627–1636. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1870-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanhercke T, Tahchy A, Shrestha P, Zhou XR, Singh SP, Petrie JR. Synergistic effect of WRI1 and DGAT1 coexpression on triacylglycerol biosynthesis in plants. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrett TP, Weise SE, Benning C. Increasing the energy density of vegetative tissues by diverting carbon from starch to oil biosynthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9:874–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller R, Durrett TP, Kosma DK, Lydic TA, Muthan B, Koo AJ, Bukhman YV, Reid GE, Howe GA. Altered lipid composition and enhanced nutritional value of Arabidopsis leaves following introduction of an algal diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2. Plant Cell. 2013;25:677–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwai M, Ikeda K, Shimojima M, Ohta H. Enhancement of extraplastidic oil synthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using a type-2 diacylglycerol acyltransferase with a phosphorus starvation–inducible promoter. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12:808–819. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanjaya R, Miller TP, Durrett DK, Kosma TA, Lydic B, Muthan AJK, Koo YV, Bukhman GE, Reid GA, Howe J, Ohlrogge C. Benning, Altered lipid composition and enhanced nutritional value of Arabidopsis leaves following introduction of an algal diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2. Plant Cell. 2013;25:677–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.104752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Han D, Yoon K, Hu Q, Li Y. Characterization of type 2 diacylglycerol acyltransferases in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals their distinct substrate specificities and functions in triacylglycerol biosynthesis. Plant J. 2016;86:3–19. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villa JA, Cabezas M, de la Cruz F, Moncalián G. Use of limited proteolysis and mutagenesis to identify folding domains and sequence motifs critical for wax ester synthase/acyl coenzyme A:diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1132–1141. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03433-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalscheuer R, Steinbuchel A. A novel bifunctional wax ester synthase/acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase mediates wax ester and triacylglycerol biosynthesis in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8075–8082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Mao Z, Luo L, Wan X, Huang F, Gong Y. Two bifunctional enzymes from the marine protist Thraustochytrium roseum: biochemical characterization of wax ester synthase/acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity catalyzing wax ester and triacylglycerol synthesis. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:185. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0869-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanhercke T, Wood CC, Stymne S, Singh SP, Green A. Metabolic engineering of plant oils and waxes for use as industrial feedstocks. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11:197–210. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi S, Vallerodriguez JO, Khoomrung S, Siewers V, Nielsen J. Functional expression and characterization of five wax ester synthases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their utility for biodiesel production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:7–7. doi: 10.1186/PREACCEPT-1932279820621895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lung SC, Weselake RJ. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase: a key mediator of plant triacylglycerol synthesis. Lipids. 2006;41:1073–1088. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saha S, Enugutti B, Rajakumari S, Rajasekharan R. Cytosolic triacylglycerol biosynthetic pathway in oilseeds. Molecular cloning and expression of peanut cytosolic diacylglycerol acyltransferase. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1533–1543. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alias CB, Lopez MCG, Fernandez FGA, Sevilla JMF, Sanchez JLG, Grima EM. Influence of power supply in the feasibility of Phaeodactylum tricornutum cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:723–733. doi: 10.1002/bit.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aslan S, Sun C, Leonova S, Dutta P, Dormann P, Domergue F, Stymne S, Hofvander P. Wax esters of different compositions produced via engineering of leaf chloroplast metabolism in Nicotiana benthamiana. Metab Eng. 2014;25:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y, Zhou W, Wei L, Li J, Jia J, Li F, Smith SM, Xu J. Regulation of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway and its integration with fatty acid biosynthesis in the oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:81. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-7-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu Y, Tarkowska D, Tureckova V, Luo T, Xin Y, Li J, Wang Q, Jiao N, Strnad M, Xu J. Antagonistic roles of abscisic acid and cytokinin during response to nitrogen depletion in oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica expand the evolutionary breadth of phytohormone function. Plant J. 2014;80:52–68. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y, Jiang P, Liu S, Gan Q, Cui H, Qin S. Methyl jasmonate- or gibberellins A3-induced astaxanthin accumulation is associated with up-regulation of transcription of β-carotene ketolase genes (bkts) in microalga Haematococcus pluvialis. Biores Technol. 2010;101:6468–6474. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu Y, Chi X, Yang Q, Li Z, Liu S, Gan Q, Qin S. Molecular cloning and stress-dependent expression of a gene encoding Delta(12)-fatty acid desaturase in the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris NJ-7. Extremophiles. 2009;13:875–884. doi: 10.1007/s00792-009-0275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu Y, Chi X, Li Z, Yang Q, Li F, Liu S, Gan Q, Qin S. Isolation and characterization of a stress-dependent plastidial Δ12 fatty acid desaturase from the Antarctic microalga Chlorella vulgaris NJ-7. Lipids. 2010;45:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Han D, Hu G, Dauvillee D, Sommerfeld M, Ball S, Hu Q. Chlamydomonas starchless mutant defective in ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase hyper-accumulates triacylglycerol. Metab Eng. 2010;12:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. PtWS DGAT cDNA sequence.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis of DGATXs. Figure S2. Multiple protein-sequence alignments of DGATXs. Figure S3. Representative topology of DGAT1s, DGAT2s, DGAT3s and WS/DGAT. Figure S4. Assessment of primers of PtDGAT1, DGAT2A, and PtWS/DGAT genes for qPCR. (a) Gel electrophoresis of the PCR product using PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and PtWS/DGAT primers. (b) Amplification curves and melting curves of PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and PtWS/DGAT primers. (c) Standard curve for absolute qPCR using vectors pMD19T-PtDGAT1, pMD19T-PtDGAT2A and pMD19T-PtWS/DGAT as templates. The vector concentrations were determined by Nanodrop ND2000 and diluted to 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 for standard curve. R2 with values above 0.99 and amplification efficiencies with values above 90% were obtained for PtDGAT1, DGAT2A and WS/DGAT genes. Figure S5. Growth of WT and the PtWS/DGAToe lines under nitrogen repletion conditions (black bar) followed by nitrogen starvation (white bar).

Additional file 3: Table S1. Primers used in this study. Table S2. The Fv/Fm of WT and PtWS/DGAToe P. tricornutum lines following nitrogen deprivation for fourteen days.