Abstract

Strategies for site-specific protein modification are highly desirable for the construction of conjugates containing non-genetically-encoded functional groups. Ideally, these strategies should proceed under mild conditions, and be compatible with a wide range of protein targets and non-natural moieties. The transpeptidation reaction catalyzed by bacterial sortases is a prominent strategy for protein derivatization that possesses these features. Naturally occurring or engineered variants of sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus catalyze a ligation reaction between a five-amino-acid substrate motif (LPXTG) and oligoglycine nucleophiles. By pairing proteins and synthetic peptides that possess these ligation handles, it is possible to install modifications onto the protein N- or C-terminus in site-specific fashion. As described in this unit, the successful implementation of sortase-mediated labeling involves straightforward solid-phase synthesis and molecular biology techniques, and this method is compatible with proteins in solution or on the surface of live cells.

Keywords: sortase, transpeptidation, site-specific labeling, chemoenzymatic labeling

INTRODUCTION

Protein conjugates possessing non-genetically-encoded functional groups are fundamentally important tools for the biochemical sciences. Through the careful addition of non-natural moieties, one is able to obtain unique protein derivatives that enable activities ranging from the development of novel therapeutics to the study of complex biochemical processes. With these applications in mind, this unit describes the use of sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation for the site-specific modification of protein termini. This chemoenzymatic method, which involves a ligation between a five-amino-acid recognition motif (LPXTG) and an oligoglycine nucleophile, is suitable for modifying proteins in solution, in complex lysates, or even on the surface of living cells (Mao, Hart, Schink, & Pollok, 2004; Parthasarathy, Subramanian, & Boder, 2007; Popp, Antos, Grotenbreg, Spooner, & Ploegh, 2007; Ritzefeld, 2014; Schmohl & Schwarzer, 2014; Tanaka, Yamamoto, Tsukiji, & Nagamune, 2008). This experimentally straightforward approach is also notable for its mild reaction conditions, as well as its capacity to tolerate a wide range of protein targets and modifications. To enable implementation of sortase-based labeling, this unit includes multiple protocols covering the design and preparation of all necessary reagents (Support Protocols 1 and 2), and a protocol for the sortase-catalyzed ligation itself (Basic Protocol). In addition, an Alternate Protocol for using sortase to modify protein targets on the surface of live cells is included.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Selection of Sortase Enzyme

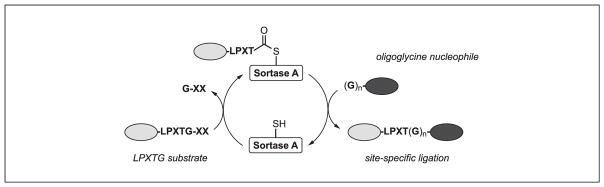

The majority of sortase-based protein labeling relies on sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus (SrtAstaph) or related mutants (Antos, Truttmann, & Ploegh, 2016; Popp & Ploegh, 2011; Ritzefeld, 2014; Schmohl & Schwarzer, 2014). As such, this unit will focus on this subset of enzymes. In all cases, these sortases recognize substrates displaying a five-amino-acid substrate motif (LPXTG), cleaving between the threonine and glycine residues to generate a thioester-linked acyl enzyme intermediate (Fig. 15.3.1). The acyl enzyme is then attacked by an oligoglycine nucleophile (typically three to five glycines), resulting in site-specific ligation of the substrate and nucleophile via a native amide bond. If the nucleophile is omitted, the acyl enzyme intermediate will hydrolyze under the aqueous reaction conditions. Currently, two engineered variants of SrtAstaph containing either five (SrtAstaph pentamutant) or seven (SrtAstaph heptamutant) point mutations have risen to prominence as the preferred enzymes for this process by offering key advantages over the wild-type enzyme. These include enhanced reaction rates (penta-and heptamutant) and lack of the requirement for a Ca2+ cofactor (heptamutant) in the reaction mixture (Chen, Dorr, & Liu, 2011; Hirakawa, Ishikawa, & Nagamune, 2015; Witte et al., 2015; Wuethrich et al., 2014). Given these features, the authors recommend that initial labeling studies employ either of these engineered SrtAstaph derivatives, and complementary labeling protocols for the use of either the penta- or heptamutant are provided below. Protocols for sortase expression are also included here, and expression plasmids for both enzymes are conveniently available through the online gene repository Addgene, or via request from the authors.

Figure 15.3.1.

Sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation. Wild-type and engineered variants of sortase A from Staphylococcus aureus recognize substrates containing an LPXTG motif. The active site cysteine of sortase A cleaves between the threonine and glycine residues to generate a thioester-linked acyl enzyme intermediate. This intermediate is then attacked by an oligoglycine nucleophile, which releases the sortase enzyme and generates a site-specific ligation product linked via a native amide bond. This reaction can be harnessed to generate proteins site-specifically labeled at the N- or C-terminus.

Design of Proteins Compatible with Sortase-Mediated Transpeptidation

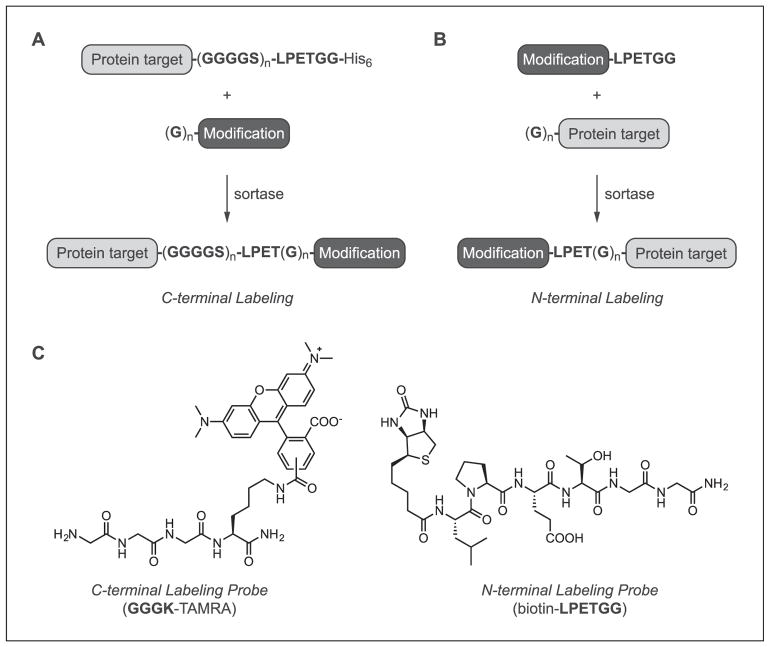

Proteins compatible with sortase-mediated labeling are accessible using standard molecular biology and cloning techniques. The specific design features required depend on which terminus of the protein is being targeted for modification. For C-terminal labeling, the protein target will serve as the initial sortase substrate, and so the LPXTG motif is simply inserted onto the C-terminal end of the protein (Fig. 15.3.2A). Most amino acids are tolerated in the X position of the substrate motif, though glutamic acid (E) is frequently used in this position due to its prevalence in in vivo sortase A substrates (Boekhorst, de Been, Kleerebezem, & Siezen, 2005; Litou, Bagos, Tsirigos, Liakopoulos, & Hamodrakas, 2008). The accessibility of the LPXTG motif is also critical for successful transpeptidation, and so it is common to add a short, flexible linker composed of Gly4Ser repeats between the body of the protein and the LPXTG site (Chen et al., 2015; Heck, Pham, Hammes, Thöny-Meyer, & Richter, 2014; Wagner et al., 2014). Whether this linker is required, and the exact length needed for the linker sequence, are protein dependent and must be determined empirically. Other design features that are important include not placing the LPXTG motif at the very C-terminus of the protein target. Best results are obtained when at least one additional residue is in amide linkage with the final glycine. In practice, this is typically achieved by adding an affinity purification handle (e.g., His6) following the LPXTG site. The loss of this tag following transpeptidation not only provides a convenient means of monitoring the efficiency of gel labeling by immunoblotting and/or Coomassie staining, but can also be leveraged for protein conjugate purification (Antos, Miller, Grotenbreg, & Ploegh, 2008; Levary, Parthasarathy, Boder, & Ackerman, 2011; Massa et al., 2016; Swee et al., 2013).

Figure 15.3.2.

Site-specific labeling of target proteins using sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation. (A) Reaction scheme for installing modifications at the protein C-terminus. Target proteins contain the requisite sortase substrate motif (e.g., LPETGG) separated from the body of the protein with an optional GGGGS linker. The sortase cleavage site is followed by an optional tag, such as His6, to assist with reaction monitoring and labeled protein purification. For C-terminal labeling, the target protein is paired with an oligoglycine nucleophile tethered to the desired modification. (B) Reaction scheme for installing modifications at the protein N-terminus. Target proteins serve as the reaction nucleophile, and contain one or more N-terminal glycines. Protein targets are paired with synthetic peptides containing the sortase recognition site (e.g., LPETGG) and the modification of interest. (C) Representative examples of peptide probes compatible with sortase-mediated C-terminal (left) or N-terminal (right) labeling.

With respect to N-terminal labeling, the target protein will serve as the oligoglycine nucleophile, and therefore at least one N-terminal glycine residue is inserted at the protein N-terminus (Fig. 15.3.2B; Antos et al., 2009a; Hess et al., 2012; Schoonen, Pille, Borrmann, Nolte, & van Hest, 2015; Williamson, Webb, & Turnbull, 2014; Yamamoto & Nagamune, 2009). As in the case of C-terminal labeling, accessibility of the reactive terminus is critical, so multiple glycines (3 to 5 residues) are often utilized to ensure optimal results. For substrates produced in E. coli, glycines should be placed immediately following the initiator methionine, which should be removed by methionylaminopeptidase to liberate a free aminoglycine terminus (Hirel, Schmitter, Dessen, Fayat, & Blanquet, 1989). In the event that methionine removal is incomplete, protease cleavage sites that generate a free glycine N-terminus can provide an alternate strategy. Appropriate proteases for this purpose include thrombin, TEV, Factor Xa, or the SUMO protease Ulp1 (Malakhov et al., 2004; Waugh, 2011).

One final note about protein target design concerns derivatives with both a C-terminal LPXTG motif and N-terminal glycines. If the end goal is selective modification of a specific protein terminus, then such dual-functionalized derivatives should be avoided, as they may be susceptible to intramolecular transpeptidation, giving rise to circular protein products (Antos et al., 2009b; Jia et al., 2014; van ’t Hof, Maňásková, Veerman, & Bolscher, 2015). In certain cases, proteins containing a C-terminal LPXTG site and an N-terminal glycine may be amenable to site-specific modification at both sites. Examples of controlled modification at both protein termini using a sortase-based approach have been reported, and will not be discussed further here (Antos et al., 2009a; Wuethrich et al., 2014).

Design of Peptide Probes Compatible with Sortase-Mediated Transpeptidation

As in the case of the design principles for compatible protein targets, the structural requirements for the associated peptide probes depends on whether these materials are intended for C-terminal or N-terminal modification. In the case of C-terminal ligations, LPXTG-containing proteins are paired with a synthetic oligoglycine nucleophile consisting of at least one N-terminal glycine covalently tethered to the modification of choice (Fig. 15.3.2A). While a single glycine can be sufficient for successful transpeptidation (Alt et al., 2015; Baer et al., 2014; Row, Roark, Philip, Perkins, & Antos, 2015), most nucleophiles contain three to five glycine residues (for examples see Fang et al., 2016; Hui, Tamsen, Song, & Tsourkas, 2015; Policarpo et al., 2014; Rashidian et al., 2015). This more closely mimics the pentaglycine nucleophile utilized in vivo by S. aureus sortase A (Ton-That, Faull, & Schneewind, 1997), and presumably prevents the peptide payload from obstructing the reaction of the peptide amine terminus with the acyl enzyme intermediate. It should also be noted that alternate primary amine (Baer et al., 2014; Glasgow, Salit, & Cochran, 2016; Parthasarathy et al., 2007) or hydrazine nucleophiles (Li et al., 2014) have been successfully used in transpeptidation reactions; however, these non-glycine nucleophiles are generally less successful than glycine derivatives.

For N-terminal labeling, protein targets with one or more N-terminal glycines are ligated to peptides containing the LPXTG motif (Fig. 15.3.2B). The modification of choice is positioned on the N-terminus of the LPXTG peptide probe. Like the LPXTG-containing proteins described above, LPXTG peptides often contain glutamic acid in the X position, and possess an additional residue following the LPXTG sequence (e.g., LPXTGG) or terminate in a primary amide (e.g., LPXTG-NH2) to promote optimal reactivity (for examples see Hess, Guimaraes, Spooner, Ploegh, & Belcher, 2013; Schoonen et al., 2015; Swee, Lourido, Bell, Ingram, & Ploegh, 2015; Yamamoto & Nagamune, 2009).

An attractive feature of sortase-based methods is that peptide probes for both N-terminal and C-terminal labeling are conveniently available via standard solid-phase peptide synthesis. The exceptional versatility of the technique arises from the ability to decorate these probes with a variety of non-genetically-encoded functional groups. To this end, numerous commercial sources provide access to non-natural amino acid building blocks and amine- or thiol-reactive reagents that can be readily incorporated into a solid-phase synthesis scheme. As examples, synthetic protocols for both N-terminal and C-terminal labeling probes are presented in this unit. While we recommend manual peptide synthesis as a cost-effective means for obtaining the required peptide materials, suitably modified peptide materials may also be obtained via commercial peptide synthesis or university core facilities.

BASIC PROTOCOL: SITE-SPECIFIC LABELING OF PURIFIED PROTEINS VIA SORTASE-MEDIATED TRANSPEPTIDATION (N- OR C-TERMINAL LABELING)

This protocol describes the labeling of proteins that have been purified prior to the transpeptidation reaction. Generally, this involves target proteins that can be produced and isolated from E. coli or other standard expression hosts. Progress of the reaction is best monitored in accordance with the peptide probe to be installed; immunoblotting can be used for probes with a biotin moiety, while in-gel fluorescence scanning is convenient for probes containing a fluorophore. SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining may also be used, as transpeptidation products often exhibit mobilities that are distinct from the unlabeled input protein. Mass spectrometry provides an additional alternative for reaction monitoring. This protocol also takes advantage of engineered sortase variants that show increased activity relative to wild-type SrtAstaph. This includes the SrtAstaph pentamutant, which exhibits increased activity but still requires the Ca2+ cofactor (Chen et al., 2011), and the SrtAstaph heptamutant, which also has increased activity but does not require the presence of Ca2+ for transpeptidation (Hirakawa et al., 2015; Witte et al., 2015; Wuethrich et al., 2014).

Materials

Purified LPXTG-containing target protein (see Strategic Planning; cannot be in phosphate-containing buffer when using pentamutant variant of sortase)

Purified sortase A pentamutant or heptamutant stock solution (see Strategic Planning and Support Protocol 1)

Oligoglycine peptide probe stock solution (5 to 10 mM in DMSO or H2O; Support Protocol 2)

-

10× sortase reaction buffer:

for pentamutant: 500 mM Tris·Cl, pH 7.5 (APPENDIX 2E), 1.5 M NaCl, 100 mM CaCl2)

for heptamutant: 500 mM Tris·Cl, pH 7.5 (APPENDIX 2E) supplemented with 1.5 M NaCl, or 10× phosphate buffered saline (PBS; APPENDIX 2E)

Purified target protein containing 1 to 5 N-terminal glycine residues (see Strategic Planning; cannot be in phosphate-containing buffer when using pentamutant variant of sortase)

LPXTGG peptide probe stock solution (5 to 10 mM in DMSO or H2O; Support Protocol 2)

Ni-NTA column (optional; see UNIT 9.4; Petty, 1996)

Imidazole (optional)

1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes

4°C or 25°C incubator

Zeba desalting column (ThermoFisher) or centrifugal concentrator with MWCO below the molecular weight of the target protein (Millipore)

Additional reagents and equipment for SDS-PAGE (UNIT 10.1; Gallagher, 2012), Coomassie staining (UNIT 10.5; Echan & Speicher, 2002), immunoblotting (UNIT 10.10; Ni, Xu, & Gallagher, 2017), mass spectroscopy (see Chapter 16 in this manual), and Ni-NTA chromatography (UNIT 9.4; Petty, 1996)

-

Mix the following in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube such that the final concentrations are as follows.

-

For C-terminal labeling:

50 μM purified target protein (possessing C-terminal LPXTG motif)

2.5 μM sortase A (pentamutant or heptamutant)

250 μM oligoglycine peptide probe

1× sortase reaction buffer (1:10 dilution of 10× sortase reaction buffer in the final reaction solution).

-

For N-terminal labeling:

50 μM purified target protein (possessing 1 to 5 N-terminal glycine residues)

2.5 μM sortase A (pentamutant or heptamutant)

250 μM LPXTGG peptide probe

-

1× sortase reaction buffer (1:10 dilution of 10× sortase reaction buffer in the final reaction solution).

The choice of reaction buffer depends on whether pentamutant or heptamutant sortase is used. See Materials above for buffer components and concentrations.

-

-

Incubate the reaction for 2 hr at 4°C or 30 min at 25°C. Analyze by SDS-PAGE (UNIT 10.1; Gallagher, 2012) followed by Coomassie staining (UNIT 10.5; Echan & Speicher, 2002) or in-gel fluorescence staining, immunoblotting (UNIT 10.10; Ni et al., 2017), or mass spectrometry (see Chapter 16 in this manual).

The reaction conditions described in steps 1 and 2 provide a suitable starting point for optimizing the labeling protocol. Slightly different reaction rates are observed for each purified target protein, and consequently the reaction parameters may require optimization to achieve high levels of protein labeling. Often, the concentrations of sortase and peptide probe may be reduced without sacrificing labeling efficiency. Reactions can be carried out at 4°C or 25°C, depending on target protein stability. -

Remove excess peptide probe using commercial desalting columns (Zeba) or spin concentrators.

If required, additional purification of the labeled protein may be achieved via size-exclusion or ion-exchange chromatography. Optional step for C-terminal labeling: If a His6 tag has been included C-terminal to the LPXTG motif in the target protein, then unlabeled target protein and His6-tagged sortase may be conveniently removed by passing the crude reaction mixture over an Ni-NTA column (UNIT 9.4; Petty, 1996). The column flow-through will contain the C-terminally labeled protein. To minimize nonspecific binding, the reaction mixture can be diluted in 1× sortase reaction buffer supplemented with imidazole (10 to 30 mM final imidazole concentration) prior to exposure to the Ni-NTA resin.

ALTERNATE PROTOCOL: LABELING CELL-SURFACE PROTEINS IN LIVING CELLS VIA SORTASE-MEDIATED TRANSPEPTIDATION

In this protocol, we describe strategies for labeling proteins displayed on the surface of live cells using the Ca2+-independent sortase A heptamutant. This procedure is suitable for targets with extracellularly exposed N-termini (type I membrane proteins) or C-termini (type II membrane proteins). To allow labeling of type I membrane proteins, the target should be engineered to display 1 to 5 glycines at its N-terminus. For type II membrane proteins, the sortase recognition motif (LPXTG) is fused at the C-terminus. Once expressed on the target cell, these proteins can be labeled by exposing them to sortase and the appropriate peptide probe in tissue culture medium. After washing to remove excess peptide probe and sortase, labeled cells can be directly imaged, characterized by flow cytometry, or subjected to other analyses.

Materials

Target cells

Plasmid encoding target protein (type II membrane protein with C-terminal LPXTG motif or type I membrane protein with 1 to 5 N-terminal glycines)

Transfection reagent (Lipofectamine, Invitrogen; Trans IT, Mirus; FuGENE 6, Promega)

Culture medium such as DMEM (phenol red–free; presence of 10% serum does not inhibit the sortase reaction)

1 mM purified sortase A heptamutant stock solution (Support Protocol 1)

10 mM peptide probe stock in DMSO or H2O (oligoglycine probe for labeling type II membrane proteins, LPXTGG probe for labeling type I membrane proteins; Support Protocol 2)

10× sortase reaction buffer: 500 mM Tris·Cl, pH 7.5 (APPENDIX 2E) containing 1.5 M NaCl

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (without Ca2+ or Mg2+; APPENDIX 2E)

1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes

Plastic tissue culture dishes

Microscope

-

Transfect target cells with a plasmid encoding the engineered target protein according to transfection reagent manufacturer’s directions.

Cells may be cultured and transfected on plastic dishes, subsequently detached, and collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes for labeling. Collect ~1 × 106 cells and resuspend in 70 μl of DMEM. Place cell suspension on ice.

-

Label cells by preparing the following reaction mixtures:

For N-terminal labeling of type I membrane proteins: Combine 10 μl of 1 mM heptamutant sortase, 5 μl of 10 mM LPXTGG peptide probe, 5 μl of 10× sortase reaction buffer, and 10 μl of sterile water. Mix well and let the mixture incubate on ice for 10 min prior to adding this mixture to the cells suspended in DMEM.

For C-terminal labeling of type II membrane proteins: Combine 10 μl of 1 mM heptamutant sortase, 5 μl of 10 mM oligoglycine probe, 5 μl of 10× sortase reaction buffer, and 10 μl of sterile water. Mix well and directly add to the cells suspended in DMEM.

-

Incubate the cell suspension and the appropriate sortase reaction mixture on ice for 45 min with occasional gentle mixing.

As in the case of labeling purified proteins in solution (see Basic Protocol), the above conditions provide an appropriate starting point for further optimization. Sortase and probe concentrations, as well as reaction times, should be varied to achieve the desired level of labeling. In particular, peptide probe concentrations may be lowered without significant loss of labeling efficiency, though this must be determined empirically. Sortase-mediated cell labeling may also be carried out at higher temperatures (room temperature or 37°C), though ice-cold temperatures are often preferable if endocytosis or other membrane trafficking events affect the target protein of interest. Finally, to label a higher or lower number of cells, simply adjust the volume of reactions proportionally. -

Wash cells at least three times with 1-ml portions of ice-cold PBS.

This step removes both sortase and excess probe. Extensive washing is necessary to remove unbound probe and decrease the background signal for microscopy applications. -

Add either phenol red-free tissue culture medium or PBS to labeled cells, and replate to observe by microscopy.

Labeled cells can also be resuspended, treated with relevant antibody or affinity reagents, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Alternatively, cell lysates may be characterized using SDS-PAGE (UNIT 10.1; Gallagher, 2012) and immunoblotting (UNIT 10.10; Ni et al., 2017).

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 1: EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF SrtAstaph PENTAMUTANT AND HEPTAMUTANT

Several mutant versions of SrtAstaph are now available, including those with increased catalytic activity and lack of dependence on a Ca2+ cofactor (Chen et al., 2011; Gianella, Snapp, & Levy, 2016; Hirakawa et al., 2015; Witte et al., 2015). In nearly all cases, the N-terminal transmembrane domain present in the wild-type enzyme has been truncated to improve solubility. Early in the development of sortase-mediated protein labeling, transpeptidations were often performed with a version of wild-type SrtAstaph lacking the first 59 amino acids (Ilangovan, Ton-That, Iwahara, Schneewind, & Clubb, 2001). The SrtAstaph pentamutant and heptamutant utilized in the Basic and Alternate Protocols of this unit are based on this original 59 amino acid–deletion construct. Both mutant versions can be obtained in large quantities (20 to 40 mg/liter) following expression and purification from E. coli. These enzymes also possess C-terminal His6 tags to aid in purification.

Materials

Sortase pentamutant or heptamutants expression plasmid: pET30b (available from Addgene or via request from the authors)

E. coli BL-21(DE3) competent cells (New England Biolabs)

Terrific broth (TB) medium with and without appropriate antibiotic: kanamycin (1000× stock = 30 mg/ml in H2O)

LB agar plates containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin

1 M isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in H2O

Lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8 (APPENDIX 2E), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol

10 mg/ml DNAse I stock solution in H2O

Ni-NTA agarose slurry (Qiagen)

Elution buffer: 50 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8 (APPENDIX 2E), 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol (v/v), with and without 350 mM imidazole

Culture plates and tubes

4-liter culture flask

37° and 30°C incubators with shaking

Spectrophotometer and appropriate cuvettes

Refrigerated centrifuge

French press (pre-chilled; see UNIT 6.2; Wingfield, 2014) or probe sonicator (Branson Sonifier 450)

1.5 × 12–cm disposable polypropylene column (BioRad)

Centrifugal concentrator with low <10 kD MWCO (optional, Millipore)

Additional reagents and equipment for Ni-NTA chromatography (UNIT 9.4; Petty, 1996)

Transform sortase expression plasmid into E. coli BL-21(DE3) and plate on LB agar plates containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin. Grow overnight at 37°C.

Pick a single colony and inoculate 25 ml of TB containing the appropriate antibiotic (30 μg/ml kanamycin). Grow overnight at 37°C as a starter culture.

Add 25 ml of the overnight culture to 1 liter of TB with 30 μg/ml kanamycin in a 4-liter culture flask. Grow with agitation to ensure proper aeration. Monitor the OD600 until 0.6. At that point, induce by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM and shake overnight at 30°C.

-

Harvest the bacterial pellet by centrifuging for 20 min at 6000 × g, 4°C. Decant TB and resuspend pellet in 35 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer supplemented with 20 μg/ml DNAse I.

Do not add protease inhibitors to lysis buffer, as these may interfere with sortase activity. Lyse bacteria by passing through a pre-chilled French press cell (UNIT 6.2; Wingfield, 2014) two times at 1250 psi. Alternatively, lyse by sonication (four cycles of 1 min with duty cycle set to 50%, and output control set to 4). Chill samples in between sonication cycles to avoid excessive warming.

Clarify the lysate by centrifuging for 30 min at 12,000 × g, 4°C.

-

Pack 2 to 5 ml of Ni-NTA agarose slurry into a polypropylene column and wash with 10 slurry volumes of lysis buffer. Apply the clarified supernatant to the column and allow it to flow through. Wash column with 50 slurry volumes of lysis buffer.

Ni-NTA chromatography is described in UNIT 9.4 (Petty, 1996). Elute sortase with 2.5 slurry volumes of elution buffer.

-

Optional: Dialyze two times against 4 liters of lysis buffer without imidazole to remove excess imidazole.

It is advisable at this stage to check the purity of the enzyme by SDS-PAGE (both pentamutant and heptamutant are ~17.7 kDa), and to determine enzyme concentration using either Bradford assay or protein absorbance at 280 nm. -

Optional: Concentrate the protein further in a centrifugal concentrator with a low-molecular-weight cutoff (<10 kDa).

The sortase constructs described are soluble and have been concentrated to 1 mM without signs of aggregation. Stock solutions can be stored for up to 1 month at 4°C, or several months at −80°C, without loss of activity.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 2: SYNTHESIS OF OLIGOGLYCINE PROBES FOR C-TERMINAL LABELING AND LPXTG PROBES FOR N-TERMINAL LABELING

Sortase-based methods for protein labeling impose very few limitations on modifications that can be tethered to the oligoglycine or LPXTG peptide probes. In a case-by-case manner, readers may find more efficient synthetic routes to access desired probes based on the available orthogonal protecting groups or the special structural requirement of payloads to be conjugated. Nevertheless, in this section, we will introduce three representative examples describing the synthesis of peptide substrates compatible with N- or C-terminal transpeptidation reactions using solid-phase synthesis and established peptide conjugation chemistries. The ‘a’ steps below describe the solid-phase synthesis of GGGK(TAMRA), a triglycine-derived organic fluorophore for C-terminal protein labeling (see Fig. 15.3.2C). The ‘b’ steps also outline the synthesis of a C-terminal labeling probe, in this case via solution-phase labeling of a GGGC peptide with widely available maleimide-derived payloads through thiol-Michael addition. Finally, the ‘c’ steps describe an N-terminal labeling probe synthesized via solution-phase conjugation of an LPETGG peptide to amine-reactive NHS esters (see Fig. 15.3.2C for a related example). All procedures require minimum instrumentation and should be feasible for laboratories not specialized in peptide or synthetic chemistry.

Materials

Rink amide resin, 100 to 200 mesh, cross-linked with 1% (w/w) divinylbenzene (Advanced ChemTech, cat. no. SA5030)

Dichloromethane (DCM)

Piperidine

N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF)

-

Fmoc protected amino acids:

Fmoc-Gly3-OH (ChemImpex, cat. no. 08072)

Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852008)

Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852065)

Fmoc-Leu-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852011)

Fmoc-Pro-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852017)

Fmoc-Glu(tBu)-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852009)

Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852000)

Fmoc-Gly-OH (Novabiochem, cat. no. 852001)

HBTU (2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexauorophosphate; ChemPep, cat. no. 120802)

Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA)

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

Triisopropylsilane (TIPS)

5(6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)

Benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate (PyBOP)

Diethyl ether, ice cold

Phosphate buffered saline (without Ca2+ or Mg2+; APPENDIX 2E)

Maleimide- or NHS-derived modification (Conju-probe, ThermoFisher, or Lumiprobe)

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)

EDT (1,2-ethanedithiol)

Solid-phase peptide synthesis vessel with associated caps and filter frits

Wrist-action shaker or similar equipment for mixing solid-phase reaction vessels

Vacuum source

HPLC system with C18 reversed-phase column (UNIT 8.7; Josic & Kovac, 2010)

Lyophilizer

Additional reagents and equipment for reversed-phase HPLC (UNIT 8.7; Josic & Kovac, 2010) and mass spectroscopy (Chapter 16)

Solid-phase synthesis of GGGK(TAMRA)

-

1a

Add 0.2 mmol of Rink amide resin to a peptide synthesis vessel and solvate the resin by adding DCM (10 ml). Gently shake the reaction vessel in a wrist-action shaker at room temperature for 15 min and remove the DCM by vacuum filtration.

-

2a

Add 20% (v/v) piperidine solution in DMF (5 ml) to the resin and shake for 30 min at room temperature. Remove the solution by vacuum filtration and wash the resin with DMF (10 ml) three times with filtration and occasional shaking in between.

Piperidine serves as a base for the selective removal of the Fmoc protecting group. -

3a

Dissolve Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-OH (1 mmol), HBTU (1 mmol), and DIPEA (2 mmol) in DMF (5 to 10 ml) and add the mixture to the resin. Shake the suspension for 2 hr at room temperature.

-

4a

Remove the reaction solution by vacuum filtration, then wash resin three times with DMF (5 ml).

-

5a

Repeat step 2 to remove the Fmoc group.

-

6a

Repeat step 3, substituting Fmoc-Gly3-OH for Fmoc-Lys(Mtt)-OH.

-

7a

Remove the reaction solution by vacuum filtration, then wash the resin three times with DMF (5 ml).

-

8a

Add 5 ml of a solution of 1% (v/v) TFA and 2% (v/v) TIPS in DCM to selectively remove the 4-methyl trityl (Mtt) protecting group from the previously coupled Lys residue. Incubate the resin with this cleavage solution for 30 min at room temperature. Remove the cleavage solution via vacuum filtration. Add an additional 5 ml of Mtt cleavage solution and incubate for 30 min to ensure removal of the Mtt group.

The colorimetric Kaiser test (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 60017), a very sensitive method to detect the presence of primary amines, can be used to confirm the successful deprotection of Mtt (Kaiser, Colescott, Bossiniger, & Cook, 1970). Similarly, this test can be used after each amino acid coupling step to ensure reaction completion. -

9a

Wash the resin with three 5-ml portions of DCM followed by three 5-ml portions of DMF.

-

10a

Add 7 ml of a solution of 5(6)-TAMRA (0.2 mmol), PyBOP (0.2 mmol), and DIPEA (0.4 mmol) in DMF to the resin and shake overnight at room temperature. Avoid exposure to light and keep reaction vessel covered when possible.

If the dye is readily available, the amount of TAMRA may be increased to improve coupling efficiency. Whether this is done or not, the non-coupled peptide will ultimately be removed during HPLC purification. -

11a

Remove the reaction solution by vacuum filtration, then wash the resin three times with DMF (5 ml).

-

12a

Remove the terminal Fmoc group by repeating step 2. Include two additional washes with DCM (5 ml) prior to cleavage of the peptide from the resin.

-

13a

Cleave the peptide from the resin by treatment with 5 ml of a solution consisting of 95% (v/v) TFA, 2.5% (v/v) water, and 2.5% (v/v) TIPS for 3 hr at room temperature.

-

14a

Elute the cleavage solution into 35 ml of ice-cold diethyl ether, and rinse the resin with an additional 3 ml of the cleavage solution (from step 13a) into the ether.

-

15a

Pellet the precipitate by centrifuging 10 min at ≥1500 × g, room temperature or lower. Remove the supernatant, and evaporate the excess diethyl either under a constant air flow for ~20 min in a fume hood.

-

16a

Redissolve the pellet in ~5 to 10 ml water. A small aliquot can be sent for mass spectrometry analysis (see Chapter 16). Purify the remaining material by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column (Josic & Kovac, 2010).

-

17a

Lyophilize the pure peptide fractions and redissolve as needed for sortase-catalyzed protein labeling (see Basic Protocol or Alternate Protocol)

Probes can be stored as solutions in DMSO at −20°C for several months without loss of activity.

Synthesis of GGGC probes via maleimide coupling

-

1b

Manually synthesize the GGGC peptide using the solid-phase technique outlined in the ‘a’ steps.

Appropriate Fmoc-protected amino acid building blocks (Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH and Fmoc-Gly3-OH) are listed in Materials, above. Follow steps 1a to 7a for Fmoc deprotection and amino acid coupling to generate the desired GGGC sequence. Follow steps 12a to 17a for cleavage from the resin and downstream analysis and purification. For cysteine-containing sequences, an additional 2% (v/v) of EDT should be added to the cleavage solution described in step 13a. In addition to manual peptide synthesis, the short GGGC sequence may be obtained from commercial sources or core facilities dedicated to peptide synthesis.IMPORTANT NOTE: Avoid extended storage of GGGC peptide in solution, as intermolecular disulfide bonds will form, which in turn will compromise cysteine side chain reactivity. For the following steps, only dissolve the amount needed or remove solvent immediately after use if recovery of excess GGGC peptide is desired. -

2b

Dissolve the desired amount of GGGC in PBS (without Ca2+ and Mg2+) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. In a separate tube, dissolve the maleimide-functionalized payload in a minimum amount of aqueous or water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., DMF, acetonitrile, PBS, water). Combine the solutions to achieve a final molar ratio of 2 equivalents of peptide to 1 equivalent of maleimide reagent. Gently shake at room temperature.

An excess of peptide is typically used to fully consume costly maleimide-functionalized reagents. Maleimide-derived reagents containing modification such as fluorophores, biotin, or biorthogonal reaction handles are available from various commercial sources (e.g., Conju-probe, ThermoFisher, Lumiprobe). -

3b

Monitor the maleimide coupling reaction by mass spectrometry (Chapter 16).

The expected mass of the peptide conjugate will be equal to the summation of the free GGGC peptide plus the maleimide-functionalized payload. The reaction is complete when the limiting reagent (typically the maleimide) is fully consumed. This often occurs within 4 hr at room temperature; however, the reaction may also be left to incubate overnight. -

4b

After the coupling is complete, directly inject the reaction into a reversed-phase HPLC system (C18 column) for purification of the GGGC-maleimide peptide (UNIT 8.7; Josic & Kovac, 2010).

-

5b

Lyophilize the pure peptide fractions and redissolve as needed for sortase-catalyzed protein labeling (see Basic Protocol or Alternate Protocol)

Probes can be stored as solutions in DMSO at −20°C for several months without loss of activity.

Synthesis of LPETGG probes via NHS-ester coupling

-

1c

Manually synthesize the LPETGG peptide using the solid-phase technique outlined in the ‘a’ steps.

Appropriate Fmoc-protected amino acid building blocks (Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Pro-OH, Fmoc-Glu(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH, and Fmoc-Gly-OH) are listed in Materials, above. Follow steps 1a to 7a for Fmoc deprotection and amino acid coupling to generate the desired LPETGG sequence. Follow steps 12a-17a for cleavage from the resin and downstream analysis and purification.While other amino acids may be substituted in place of Glu (E), lysine should be avoided to prevent competing reactivity with the peptide N-terminus in the following NHS-ester coupling steps. In addition to manual peptide synthesis, the short LPETGG sequence may be obtained from commercial sources or core facilities dedicated to peptide synthesis. -

2c

Dissolve the desired amount of LPETGG peptide in DMSO to a final concentration of 5 mg/ml. Add the dissolved peptide directly to the NHS ester-activated payload to achieve a final molar ratio of 2 equivalents of peptide to 1 equivalent of NHS reagent. If the payload does not fully dissolve in organic solvent, a small amount of aqueous solvent at neutral pH can be added without significantly compromising yield. Gently shake at room temperature.

-

3c

Monitor the NHS-ester coupling reaction by mass spectrometry (Chapter 16).

The reaction is usually complete within 4 hr at room temperature, but may also be left to incubate overnight. -

4c

After the coupling is complete, dilute the reaction with water to ~50% DMSO (v/v). The reaction may then be directly injected into a reversed-phase HPLC system (C18 column) for purification of the modified LPETGG peptide.

-

5c

Lyophilize the pure peptide fractions and redissolve as needed for sortase-catalyzed protein labeling (see Basic Protocol or Alternate Protocol)

Probes can be stored as solutions in DMSO at −20°C for several months without loss of activity.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

The construction of site-specifically modified proteins remains a significant challenge, and numerous strategies for this purpose are now available. Existing methods span a range of chemical approaches, from the use of lysine- or cysteine-reactive small molecule reagents to genetic techniques involving the installation of reactive natural amino acids (e.g., cysteine), unnatural amino acids, or entire protein domains (e.g., GFP, SNAP-tag) (for relevant reviews see Hinner & Johnsson, 2010; Kim, Axup, & Schultz, 2013; Spicer & Davis, 2014). Within this spectrum of options, sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation represents a powerful hybrid strategy that combines the most advantageous features of chemical and genetic strategies, namely flexibility in the types of modifications installed and the site specificity afforded by a genetically encoded short peptide tag. Sortase is not alone in this regard, and an expanding repertoire of conceptually similar chemoenzymatic labeling strategies have emerged that are built on the ability of natural or engineered enzymes to recognize short peptide tags, and facilitate the subsequent installation of non-genetically-encoded modifications. Representative examples of this group include butelase (Nguyen et al., 2014), transglutaminase (Lin & Ting, 2006), biotin ligase (Chen, Howarth, Lin, & Ting, 2005), lipoic acid ligase (Fernández-Suárez et al., 2007), trypsiligase (Liebscher et al., 2014), formyl-glycine generating enzyme (Carrico, Carlson, & Bertozzi, 2007), phosphopantetheinyl transferase (Yin et al., 2005), farnesyltransferase (Duckworth, Zhang, Hosokawa, & Distefano, 2007), and tubulin tyrosine ligase (Schumacher et al., 2015). The key attributes of many of these enzymes have been reviewed (Rabuka, 2010; Rashidian, Dozier, & Distefano, 2013). Among these strategies, sortase stands out due to its simplicity. Required for successful implementation are relatively simply techniques in synthetic peptide chemistry and protein cloning and expression. With these tools in place, sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation can be leveraged to decorate proteins with an extensive range of useful modifications.

Given the flexibility of sortase-mediated labeling, this method has proven effective for building a diverse range of polypeptide conjugates. Notable examples include the ligation of proteins or peptides to fluorophores (Popp et al., 2007; Yamamoto & Nagamune, 2009), carbohydrates (Samantaray, Marathe, Dasgupta, Nandicoori, & Roy, 2008; Wu, Guo, Wang, Swarts, & Guo, 2010), polymers (Parthasarathy et al., 2007; Qi, Amiram, Gao, McCafferty, & Chilkoti, 2013), solid supports (Chan et al., 2007; Le, Raeeszadeh-Sarmazdeh, Boder, & Frymier, 2015; Sinisi et al., 2012), therapeutics (Beerli, Hell, Merkel, & Grawunder, 2015; Fang et al., 2016), lipids (Antos et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2010), nucleic acids (Koussa, Sotomayor, & Wong, 2014; Pritz et al., 2007), metal chelators (Paterson et al., 2014; Westerlund, Honarvar, Tolmachev, & Eriksson Karlström, 2015), viral particles (Hess et al., 2013; Schoonen et al., 2015), live cells (Popp et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2014; Yamamoto & Nagamune, 2009), or even intramolecular ligations for generating cyclic proteins and peptides (Antos et al., 2009b; Jia et al., 2014; van ’t Hof et al., 2015). A full discussion of all relevant applications is beyond the scope of this unit, and we refer to the reader to reviews on this topic (Haridas, Sadanandan, & Dheepthi, 2014; Popp & Ploegh, 2011; Ritzefeld, 2014; Schmohl & Schwarzer, 2014). Furthermore, while this unit does not outline specific procedures for generating each of the conjugates listed here, it should be stressed that most are attainable using simple variations of the Basic and Alternate Protocol outlined above.

The proliferation of sortase-mediated applications has also been accompanied by refinements in the method itself. Early critiques of using sortase for protein modification pointed to poor reaction rates, reaction reversibility, and the requirement for Ca2+ in the reaction, as well as the fact that transpeptidation was restricted to LPXTG substrates. Notably, progress has been made in circumventing these limitations. The protocols in this unit, for example, rely on engineered variants of SrtAstaph with enhanced catalytic activity. These include the SrtAstaph pentamutant, which was identified in a directed evolution screen and exhibits an approximately 120-fold increase in enzyme activity versus wild-type SrtAstaph (Chen et al., 2011). The heptamutant builds on this derivative by including two additional point mutations that alleviate Ca2+ dependency (Hirakawa et al., 2015; Witte et al., 2015; Wuethrich et al., 2014). In terms of reaction reversibility, a handful of strategies have been introduced that drive reaction equilibrium through selective removal or deactivation of transpeptidation products. These strategies may be as simple as running the reaction under dialysis conditions to separate out low-molecular-weight byproducts (Kobashigawa, Kumeta, Ogura, & Inagaki, 2009; Refaei et al., 2011; Pritz et al., 2007), but also include the use of β-hairpins (Yamamura, Hirakawa, Yamaguchi, & Nagamune, 2011), depsipeptides (Liu, Luo, Flora, & Mezo, 2014; Williamson, Fascione, Webb, & Turnbull, 2012), or masked metal-binding peptides (Row et al., 2015) that prevent certain transpeptidation products from re-entering the catalytic cycle. Finally, advances have been made in expanding the substrate scope of sortase-catalyzed transpeptidations beyond the LPXTG motif. For example, sortase A from Streptococcus pyogenes is known to accept both LPXTG and LPXTA substrates (Antos et al., 2009a; Hess et al., 2013; Wuethrich et al., 2014). In addition, sortase derivatives from phage display or yeast display libraries have been identified that process XPKTG (numerous residues tolerated in the X position), LAETG, or LPEXG (X = A, C, S) substrates (Dorr, Ham, An, Chaikof, & Liu, 2014; Piotukh et al., 2011). This increased substrate scope has already enabled unique applications such as the semi-synthesis of histone H3 (Piotukh et al., 2011), orthogonal labeling of different proteins in the same viral capsid (Hess et al., 2013), and selective labeling of fetuin A in human plasma (Dorr et al., 2014).

Critical Parameters

For successful transpeptidation, the reactive protein termini (C-terminal LPXTG motif or N-terminal glycine) must be accessible to the sortase enzyme. Where possible, examination of the target protein’s crystal or NMR structure is helpful in assessing solvent accessibility. In cases where steric interference is problematic, flexible linkers may be inserted between the body of the protein and the sortase-reactive terminus (see Strategic Planning).

Optimal labeling is also achieved when the protein target serves as the limiting reagent and the peptide ligation partner is used in molar excess. This reaction stoichiometry helps ensure full conversion of the protein target to its modified form, which otherwise might be limited by the reversibility of the transpeptidation reaction. Excess peptide also minimizes the effect of competing acyl enzyme intermediate hydrolysis, which leads to unreactive protein or peptide side products.

Finally, the activity of the sortase A penta-mutant requires the inclusion of Ca2+ in the reaction buffer. As outlined above, a 10 mM final concentration of calcium chloride is sufficient for optimal sortase A pentamutant activity. If heptamutant sortase A is used, then the calcium cofactor may be omitted.

Troubleshooting

For the protocols in this unit, the most likely issue encountered will be low protein labeling efficiency. As discussed in the Basic Protocol, the reaction conditions provided serve as a starting point from which the user can optimize variables to achieve the desired labeling outcome. Therefore, in most cases higher reaction conversion may be achieved by simply extending reaction times, increasing sortase enzyme loading, or increasing the ratio of peptide probe to protein target. Running reactions at 37°C may also prove beneficial, though this is typically not required for pentamutant or heptamutant sortase A. Other recommended steps include checking the reaction pH to ensure that it is near neutral pH for optimal sortase activity, and independently characterizing the reaction components (sortase enzyme, protein target, peptide probe) to confirm that they are fully intact and free from degradation.

In the event that simple optimization is not sufficient, other possible causes of poor labeling include inaccessible protein termini (see Critical Parameters) or competing acyl enzyme hydrolysis. If poor accessibility of protein termini is suspected, extended flexible linker sequences should be inserted between the body of the protein and either the C-terminal LPXTG motif or the N-terminal oligoglycine (see Strategic Planning for details). For extensive hydrolysis, which may be evident when characterizing reactions by SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry, the recommended course of action is to increase the ratio of peptide probe to protein target. It is also important to consider the reversible nature of the transpeptidation reaction. Successful transpeptidation leads to products with intact LPXTG motifs, which can in turn be repeatedly cleaved by sortase. On long enough time scales, these products will be irreversibly hydrolyzed, and therefore it is important to carefully monitor reaction progress and to halt the reaction when the desired product has reached peak levels.

Finally, precipitation may be observed in some transpeptidation reactions. One cause may be the combination of calcium with phosphate buffers. Ca2+ is required to promote the activity of pentamutant sortase; thus, phosphate should be avoided in favor of Tris or HEPES. Alternatively, the sortase heptamutant may be used, as it does not require the Ca2+ cofactor. Precipitation may also indicate issues with the solubility of target or labeled proteins. If this is encountered, overall protein concentrations can be reduced in the reaction mixture, and the transpeptidation reaction can be performed at lower temperature (4°C) to limit protein precipitation.

Anticipated Results

The Basic Protocol described in this unit can typically be optimized to achieve excellent conversion (>90%) of the input protein to the desired transpeptidation product. Depending on the modification that is installed, formation of the site-specifically modified protein may be detected by mass spectrometry, SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining or in-gel fluorescence, or immunoblotting. In the case of SDS-PAGE characterization, transpeptidation products often show distinct electrophoretic mobility as compared to the input protein, which facilitates detection of product formation. Mass spectrometry also provides an excellent technique for confirming successful labeling and monitoring reaction progress.

While robust transpeptidation is anticipated for most proteins, certain reaction byproducts may be observed. For C-terminal protein labeling, in which the protein target contains the LPXTG motif, SDS-PAGE may reveal small quantities of hydrolyzed material at a lower apparent molecular weight, or residual acyl enzyme intermediate at a molecular weight appropriate for this covalent complex. Substrate hydrolysis may also be detected by mass spectrometry. For N-terminal labeling, given that the LPXTG peptide probe is used in excess, it is common to observe the formation of the acyl enzyme intermediate in significant quantities via in-gel fluorescence or immunoblotting if the LPXTG peptide contains a fluorophore or biotin.

For proteins displayed on live cells, the Alternate Protocol provided here typically results in detectable protein labeling after a 45-min incubation. Installation of the desired probe, which is often fluorescent or biotinylated, can then be confirmed by microscopy or flow cytometry. Alternatively, cells may be lysed and transpeptidation products may be separated by SDS-PAGE followed by in-gel fluorescence or immunoblotting.

Time Considerations

The expression and purification of pentamutant and heptamutant SrtAstaph is typically completed in 1 to 2 days. The synthesis and purification of peptide probes for C-terminal and N-terminal labeling may vary depending on peptide sequence, but generally this can be accomplished in 3 to 5 days. With all required materials in hand, the setup and analysis of sortase-catalyzed ligation reactions can be performed within 1 day. Transpeptidation reactions employing the pentamutant or heptamutant sortase are rapid, and labeling of purified protein targets in solution may be detected within minutes. However, full conversion to the labeled protein conjugate may require a few hours of incubation. In the case of cell surface labeling, 45 min of incubation is usually sufficient to achieve robust labeling. Importantly, for transpeptidation reactions both in solution and involving live cells, the specific reaction conditions will vary depending on the protein target, and should therefore be optimized for the particular application.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Antos and Ploegh labs for helpful input and suggestions. This work was supported by an NIH Award to H.L.P. (R01AI087879). J.I. also acknowledges support from the Claudia Adams Barr Program for Innovative Cancer Research.

Literature Cited

- Alt K, Paterson BM, Westein E, Rudd SE, Poniger SS, Jagdale S, … Hagemeyer CE. A versatile approach for the site-specific modification of recombinant antibodies using a combination of enzyme-mediated bioconjugation and click chemistry. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2015;54:7515–7519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos JM, Chew GL, Guimaraes CP, Yoder NC, Grotenbreg GM, Popp MWL, Ploegh HL. Site-specific N- and C-terminal labeling of a single polypeptide using sortases of different specificity. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009a;131:10800–10801. doi: 10.1021/ja902681k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos JM, Miller GM, Grotenbreg GM, Ploegh HL. Lipid modification of proteins through sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:16338–16343. doi: 10.1021/ja806779e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos JM, Popp MWL, Ernst R, Chew GL, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. A straight path to circular proteins. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009b;284:16028–16036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901752200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos JM, Truttmann MC, Ploegh HL. Recent advances in sortase-catalyzed ligation methodology. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2016;38:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer S, Nigro J, Madej MP, Nisbet RM, Suryadinata R, Coia G, … Nuttall SD. Comparison of alternative nucleophiles for Sortase A-mediated bioconjugation and application in neuronal cell labelling. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2014;12:2675–2685. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42325e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli RR, Hell T, Merkel AS, Grawunder U. Sortase enzyme-mediated generation of site-specifically conjugated antibody drug conjugates with high in vitro and in vivo potency. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhorst J, de Been MW, Kleerebezem M, Siezen RJ. Genome-wide detection and analysis of cell wall-bound proteins with LPxTG-like sorting motifs. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187:4928–4934. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4928-4934.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico IS, Carlson BL, Bertozzi CR. Introducing genetically encoded aldehydes into proteins. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3:321–322. doi: 10.1038/nchembio878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Cohen J, Song X, Zhao A, Ye Z, Feulner CJ, … Chen PR. Improved variants of SrtA for site-specific conjugation on antibodies and proteins with high efficiency. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:31899. doi: 10.1038/srep31899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan L, Cross HF, She JK, Cavalli G, Martins HFP, Neylon C. Covalent attachment of proteins to solid supports and surfaces via Sortase-mediated ligation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Dorr BM, Liu DR. A general strategy for the evolution of bond-forming enzymes using yeast display. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11399–11404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101046108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Howarth M, Lin W, Ting AY. Site-specific labeling of cell surface proteins with biophysical probes using biotin ligase. Nature Methods. 2005;2:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nmeth735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Sun Q, Molino NM, Wang SW, Boder ET, Chen W. Sortase A-mediated multi-functionalization of protein nanoparticles. Chemical Communications. 2015;51:12107–12110. doi: 10.1039/C5CC03769G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr BM, Ham HO, An C, Chaikof EL, Liu DR. Reprogramming the specificity of sortase enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:13343–13348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411179111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth BP, Zhang Z, Hosokawa A, Distefano MD. Selective labeling of proteins by using protein farnesyltransferase. Chembiochem. 2007;8:98–105. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echan LA, Speicher DW. Protein detection in gels using fixation. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2002;29:10.5:10.5.1–10.5.18. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1005s29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T, Duarte JN, Ling J, Li Z, Guz-man JS, Ploegh HL. Structurally defined αMHC-II nanobody-drug conjugates: A therapeutic and imaging system for B-cell lymphoma. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2016;55:2416–2420. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Suárez M, Baruah H, Martínez-Hernández L, Xie KT, Baskin JM, Bertozzi CR, Ting AY. Redirecting lipoic acid ligase for cell surface protein labeling with small-molecule probes. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25:1483–1487. doi: 10.1038/nbt1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher SR. One-dimensional SDS gel electrophoresis of proteins. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2012;68:10.1:10.1.1–10.1.44. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1001s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianella P, Snapp EL, Levy M. An in vitro compartmentalization-based method for the selection of bond-forming enzymes from large libraries. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2016;113:1647–1657. doi: 10.1002/bit.25939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow JE, Salit ML, Cochran JR. In vivo site-specific protein tagging with diverse amines using an engineered sortase variant. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:7496–7499. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haridas V, Sadanandan S, Dheepthi NU. Sortase-based bio-organic strategies for macromolecular synthesis. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1857–1867. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck T, Pham PH, Hammes F, Thöny-Meyer L, Richter M. Continuous monitoring of enzymatic reactions on surfaces by real-time flow cytometry: Sortase a catalyzed protein immobilization as a case study. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2014;25:1492–1500. doi: 10.1021/bc500230r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess GT, Cragnolini JJ, Popp MW, Allen MA, Dougan SK, Spooner E, … Guimaraes CP. M13 bacteriophage display framework that allows sortase-mediated modification of surface-accessible phage proteins. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2012;23:1478–1487. doi: 10.1021/bc300130z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess GT, Guimaraes CP, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, Belcher AM. Orthogonal labeling of M13 minor capsid proteins with DNA to self-assemble end-to-end multiphage structures. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2013;2:490–496. doi: 10.1021/sb400019s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinner MJ, Johnsson K. How to obtain labeled proteins and what to do with them. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2010;21:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H, Ishikawa S, Nagamune T. Ca2+ -independent sortase-A exhibits high selective protein ligation activity in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Biotechnology Journal. 2015;10:1487–1492. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirel PH, Schmitter MJ, Dessen P, Fayat G, Blanquet S. Extent of N-terminal methionine excision from Escherichia coli proteins is governed by the side-chain length of the penultimate amino acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:8247–8251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui JZ, Tamsen S, Song Y, Tsourkas A. LASIC: Light activated site-specific conjugation of native IgGs. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2015;26:1456–1460. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilangovan U, Ton-That H, Iwahara J, Schneewind O, Clubb R. Structure of sortase, the transpeptidase that anchors proteins to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:6056–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101064198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josic D, Kovac S. Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography of proteins. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2010;61:8.7:8.7.1–8.7.22. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0807s61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Kwon S, Wang CIA, Huang YH, Chan LY, Tan CC, … Craik DJ. Semienzymatic cyclization of disulfide-rich peptides using Sortase A. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:6627–6638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Colescott RL, Bossiniger CD, Cook PI. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Analytical Biochemistry. 1970;34:595–598. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Axup JY, Schultz PG. Protein conjugation with genetically encoded unnatural amino acids. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2013;17:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashigawa Y, Kumeta H, Ogura K, Inagaki F. Attachment of an NMR-invisible solubility enhancement tag using a sortase-mediated protein ligation method. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2009;43:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koussa MA, Sotomayor M, Wong WP. Protocol for sortase-mediated construction of DNA-protein hybrids and functional nanostructures. Methods. 2014;67:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le RK, Raeeszadeh-Sarmazdeh M, Boder ET, Frymier PD. Sortase-mediated ligation of PsaE-modified photosystem I from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 to a conductive surface for enhanced photocurrent production on a gold electrode. Langmuir. 2015;31:1180–1188. doi: 10.1021/la5031284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levary DA, Parthasarathy R, Boder ET, Ackerman ME. Protein-protein fusion catalyzed by sortase A. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YM, Li YT, Pan M, Kong XQ, Huang YC, Hong ZY, Liu L. Irreversible site-specific hydrazinolysis of proteins by use of sortase. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2014;53:2198–2202. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebscher S, Kornberger P, Fink G, Trost-Gross EM, Höss E, Skerra A, Bordusa F. Derivatization of antibody Fab fragments: A designer enzyme for native protein modification. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1096–1100. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201400059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, Ting AY. Transglutaminase-catalyzed site-specific conjugation of small-molecule probes to proteins in vitro and on the surface of living cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:4542–4543. doi: 10.1021/ja0604111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litou ZI, Bagos PG, Tsirigos KD, Liakopoulos TD, Hamodrakas SJ. Prediction of cell wall sorting signals in gram-positive bacteria with a hidden markov model: Application to complete genomes. Journal of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. 2008;6:387–401. doi: 10.1142/S0219720008003382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Luo EY, Flora DB, Mezo AR. Irreversible sortase A-mediated ligation driven by diketopiperazine formation. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2014;79:487–492. doi: 10.1021/jo4024914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakhov MP, Mattern MR, Malakhova OA, Drinker M, Weeks SD, Butt TR. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. Journal of Structural and Functional Genomics. 2004;5:75–86. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H, Hart SA, Schink A, Pollok BA. Sortase-mediated protein ligation: A new method for protein engineering. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:2670–2671. doi: 10.1021/ja039915e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa S, Vikani N, Betti C, Ballet S, Vanderhaegen S, Steyaert J, … Devoogdt N. Sortase A-mediated site-specific labeling of camelid single-domain antibody-fragments: A versatile strategy for multiple molecular imaging modalities. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging. 2016;11:328–339. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GKT, Wang S, Qiu Y, Hemu X, Lian Y, Tam JP. Butelase 1 is an Asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nature Chemical Biology. 2014;10:732–738. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni D, Xu P, Gallagher S. Immunoblotting and immunodetection. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2017;88:10.10.1–10.10.37. doi: 10.1002/cpps.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R, Subramanian S, Boder ET. Sortase A as a novel molecular “stapler” for sequence-specific protein conjugation. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2007;18:469–476. doi: 10.1021/bc060339w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BM, Alt K, Jeffery CM, Price RI, Jagdale S, Rigby S, … Donnelly PS. Enzyme-mediated site-specific bio-conjugation of metal complexes to proteins: Sortase-mediated coupling of copper-64 to a single-chain antibody. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2014;53:6115–6119. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty KJ. Metal-chelate affinity chromatography. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 1996;4:9.4:9.4.1–9.4.16. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0904s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotukh K, Geltinger B, Heinrich N, Gerth F, Beyermann M, Freund C, Schwarzer D. Directed evolution of sortase a mutants with altered substrate selectivity profiles. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:17536–17539. doi: 10.1021/ja205630g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policarpo RL, Kang H, Liao X, Rabideau AE, Simon MD, Pentelute BL. Flow-based enzymatic ligation by sortase A. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2014;53:9203–9208. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp MW, Antos JM, Grotenbreg GM, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. Sortagging: A versatile method for protein labeling. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3:707–708. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp MWL, Ploegh HL. Making and breaking peptide bonds: Protein engineering using sortase. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2011;50:5024–5032. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritz S, Wolf Y, Kraetke O, Klose J, Bienert M, Beyermann M. Synthesis of biologically active peptide nucleic acid-peptide conjugates by sortase-mediated ligation. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2007;72:3909–3912. doi: 10.1021/jo062331l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Amiram M, Gao W, McCafferty DG, Chilkoti A. Sortase-catalyzed initiator attachment enables high yield growth of a stealth polymer from the C terminus of a protein. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2013;34:1256–1260. doi: 10.1002/marc.201300460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabuka D. Chemoenzymatic methods for site-specific protein modification. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2010;14:790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian M, Dozier JK, Distefano MD. Enzymatic labeling of proteins: Techniques and approaches. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2013;24:1277–1294. doi: 10.1021/bc400102w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian M, Keliher E, Dougan M, Juras PK, Cavallari M, Wojtkiewicz GR, … Ploegh H. The use of (18)F-2-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) to label antibody fragments for immuno-PET of pancreatic cancer. ACS Central Science. 2015;1:142–147. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refaei MA, Combs AL, Kojetin DJ, Cavanagh J, Caperelli C, Rance M, … Tsang P. Observing selected domains in multi-domain proteins via sortase-mediated ligation and NMR spectroscopy. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2011;49:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9464-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzefeld M. Sortagging: A robust and efficient chemoenzymatic ligation strategy. Chemistry A European Journal. 2014;20:8516–8529. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Row DR, Roark TJ, Philip MC, Perkins LL, Antos JM. Enhancing the efficiency of sortase-mediated ligations through nickel-peptide complex formation. Chemical Communications. 2015;51:12548–12551. doi: 10.1039/C5CC04657B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samantaray S, Marathe U, Dasgupta S, Nandicoori VK, Roy RP. Peptide-sugar ligation catalyzed by transpeptidase sortase: A facile approach to neoglycoconjugate synthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:2132–2133. doi: 10.1021/ja077358g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmohl L, Schwarzer D. Sortase-mediated ligations for the site-specific modification of proteins. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2014;22C:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonen L, Pille J, Borrmann A, Nolte RJM, van Hest JCM. Sortase A-mediated n-terminal modification of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus for highly efficient cargo loading. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2015;26:2429–2434. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher D, Helma J, Mann FA, Pichler G, Natale F, Krause E, … Leonhardt H. Versatile and efficient site-specific protein functionalization by tubulin tyrosine ligase. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2015;54:13787–13791. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Kundrat L, Pishesha N, Bilate A, Theile C, Maruyama T, … Lodish HF. Engineered red blood cells as carriers for systemic delivery of a wide array of functional probes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:10131–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409861111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinisi A, Popp MWL, Antos JM, Pansegrau W, Savino S, Nissum M, … Buti L. Development of an influenza virus protein array using sortagging technology. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2012;23:1119–1126. doi: 10.1021/bc200577u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer CD, Davis BG. Selective chemical protein modification. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4740. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swee LK, Guimaraes CP, Sehrawat S, Spooner E, Barrasa MI, Ploegh HL. Sortase-mediated modification of αDEC205 affords optimization of antigen presentation and immunization against a set of viral epitopes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:1428–1433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214994110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swee LK, Lourido S, Bell GW, Ingram JR, Ploegh HL. One-step enzymatic modification of the cell surface redirects cellular cytotoxicity and parasite tropism. ACS Chemical Biology. 2015;10:460–465. doi: 10.1021/cb500462t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Yamamoto T, Tsukiji S, Nagamune T. Site-specific protein modification on living cells catalyzed by Sortase. Chembiochem. 2008;9:802–807. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton-That H, Faull KF, Schneewind O. Anchor structure of staphylococcal surface proteins. A branched peptide that links the carboxyl terminus of proteins to the cell wall. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:22285–22292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van ’t Hof W, Maňásková SH, Veerman ECI, Bolscher JGM. Sortase-mediated backbone cyclization of proteins and peptides. Biological Chemistry. 2015;396:283–293. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K, Kwakkenbos MJ, Claassen YB, Maijoor K, Böhne M, van der Sluijs KF, … Spits H. Bispecific antibody generated with sortase and click chemistry has broad antiinfluenza virus activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:16820–16825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408605111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh DS. An overview of enzymatic reagents for the removal of affinity tags. Protein Expression and Purification. 2011;80:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund K, Honarvar H, Tolmachev V, Eriksson Karlström A. Design, preparation, and characterization of PNA-based hybridization probes for affibody-molecule-mediated pretargeting. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2015;26:1724–1736. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Fascione MA, Webb ME, Turnbull WB. Efficient N-terminal labeling of proteins by use of sortase. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2012;51:9377–9380. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Webb ME, Turnbull WB. Depsipeptide substrates for sortase-mediated N-terminal protein ligation. Nature Protocols. 2014;9:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield P. Preparation of soluble proteins from Escherichia coli. Current Protocols in Protein Science. 2014;78:6.2.1–6.2.22. doi: 10.1002/047114064.ps0602s78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte MD, Wu T, Guimaraes CP, Theile CS, Blom AEM, Ingram JR, … Ploegh HL. Site-specific protein modification using immobilized sortase in batch and continuous-flow systems. Nature Protocols. 2015;10:508–516. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Guo X, Wang Q, Swarts BM, Guo Z. Sortase A-catalyzed transpeptidation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol derivatives for chemoenzymatic synthesis of GPI-anchored proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:1567–1571. doi: 10.1021/ja906611x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuethrich I, Peeters JGC, Blom AEM, Theile CS, Li Z, Spooner E, … Guimaraes CP. Site-specific chemoenzymatic labeling of aerolysin enables the identification of new aerolysin receptors. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nagamune T. Expansion of the sortase-mediated labeling method for site-specific N-terminal labeling of cell surface proteins on living cells. Chemical Communications. 2009:1022–1024. doi: 10.1039/b818792d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura Y, Hirakawa H, Yamaguchi S, Nagamune T. Enhancement of sortase A-mediated protein ligation by inducing a β-hairpin structure around the ligation site. Chemical Communications. 2011;47:4742–4744. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05334a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Straight PD, McLoughlin SM, Zhou Z, Lin AJ, Golan DE, … Walsh CT. Genetically encoded short peptide tag for versatile protein labeling by Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15815–15820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]