Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of a laparoscopic niche resection on niche‐related symptoms and/or fertility‐related problems, ultrasound findings and quality of life.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

University hospital.

Population

Women with a large niche (residual myometrium <3 mm) and complaints of either postmenstrual spotting, dysmenorrhoea, intrauterine fluid accumulation and/or difficulties with embryo transfer due to distorted anatomy.

Methods

Women filled out questionnaires and a validated menstrual score chart at baseline and 6 months after the laparoscopic niche resection. At baseline and between 3 and 6 months follow up niches were evaluated by transvaginal ultrasound.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was reduction of the main problem 6 months after the intervention. Secondary outcomes were complications, menstrual characteristics, dysmenorrhoea, niche measurements, intrauterine fluid, surgical outcomes, satisfaction and quality of life.

Results

In all, 101 women underwent a laparoscopic niche resection. In 80 women (79.2%) the main problem was improved or resolved. Postmenstrual spotting was significantly reduced by 7 days at 6 months follow up compared with baseline. Dysmenorrhoea and discomfort related to spotting was also significantly reduced. The residual myometrium was increased significantly at follow up. The intrauterine fluid was resolved in 86.9% of the women with intrauterine fluid at baseline; 83.3% of women were (very) satisfied. The physical component of quality of life increased, the mental component did not change.

Conclusions

A laparoscopic niche resection reduced postmenstrual spotting, discomfort due to spotting, dysmenorrhoea and the presence of intrauterine fluid in the majority of women and increased the residual myometrium.

Tweetable abstract

Laparoscopic niche resection reduces niche‐related problems and enlarges the residual myometrium.

Keywords: Caesarean scar, caesarean section, laparoscopic niche resection, niche, postmenstrual spotting, spotting

Tweetable abstract

Laparoscopic niche resection reduces niche‐related problems and enlarges the residual myometrium.

Introduction

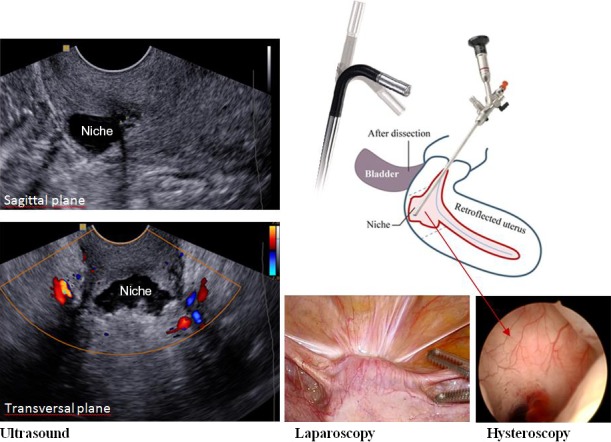

After incomplete healing of the uterine caesarean section scar a niche can be observed. A niche is a disruption of the integrity of the myometrium at the site of the caesarean scar. It can be visualised by sonohysterography or hysteroscopy.1, 2, 3 Niches with a minimum depth of 1 or 2 mm can be visualised in approximately 60% of women and large niches (with a residual myometrium [RM] <50% of the total myometrial thickness) in 24% with sonohysterography at 3–12 months after caesarean section (see Figure 1 for a large niche).1, 2 Niches are reported to be associated with postmenstrual spotting.1, 2, 3 Other symptoms include dysmenorrhoea and chronic pelvic pain.4, 5 It has been postulated that the accumulation of fluid and mucus in a large niche may impair fertility due to reduced implantation and penetration of spermatozoa.6 Furthermore, a niche can cause inaccessibility to the uterine cavity, in particular in retroflected uteri, causing problems during intrauterine insemination or embryo transfer. A niche can cause obstetric complications as well, such as niche pregnancies, malplacentation or uterine rupture.7, 8, 9

Figure 1.

A schematic overview of the method of laparoscopic niche resection under hysteroscopic control and the ultrasound image of the niche.

A laparoscopic niche resection can be considered for large problematic niches with an RM of <3 mm in women with a desire to conceive. However, current evidence for the efficacy of niche resection in the reduction of symptoms and the effect on reproductive outcomes of this innovative therapy is scarce.10 Laparoscopic niche resection was first described by Jacobson et al. in 2003.11 Most of the following studies have a retrospective design and as a consequence were not always able to make a comparison with baseline data. To date, the largest prospective study included 38 women.12

The aim of the current prospective study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a laparoscopic niche resection on postmenstrual spotting, dysmenorrhoea, intrauterine fluid, quality of life and on ultrasound findings at 6‐month follow up.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was performed between 2010 and 2015 in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in VU Medical Centre in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. All women with a niche and an RM <3 mm measured with sonohysterography, and one or more of the following problems—(1) postmenstrual spotting; (2) dysmenorrhoea; (3) midcycle intrauterine fluid accumulation diagnosed during fertility workup and considered to hamper implantation or (4) difficulties with the embryo transfer and preferring a surgical therapy—were asked to participate in the study.

Postmenstrual spotting was defined as either ≥2 days of intermenstrual spotting, or ≥2 days of brownish discharge immediately at the end of the menstrual period when the total period of the menstrual bleeding exceeded 7 days.

Exclusion criteria were an age <18 years, contraindications for general anaesthesia, pregnancy, a (suspected) malignancy, uterine or cervical polyps, submucosal fibroids, atypical endometrial cells, cervical dysplasia, cervical/pelvic infection, presence of a hydrosalpinx or an irregular cycle (>35 days or intercycle variation ≥2 weeks). We did not offer surgery to asymptomatic women with a large niche and a desire to conceive because we do not know yet if a laparoscopic niche resection reduces the risk of obstetric complications. Eligible women who had no (future) desire to conceive were advised to take hormones, use a levonorgestrel intrauterine device or undergo a hysterectomy. Women were informed about the study methods and the experimental character of this surgical intervention. They were also urged to use contraceptives for 6 months after the intervention to allow the uterine scar to heal properly and we advised a primary caesarean section at term during subsequent pregnancies. All women that met the selection criteria were included consecutively and signed informed consent before surgery. The niche resection was not performed outside the study.

Intervention

The niche resection was executed by two of the three gynaecologists (HB, JH, WH). The niche resection was guided by hysteroscopy (Figure 1). After filling the bladder with 200 ml blue dye solution the niche was opened using a a monopolar hook and excised with a cold scissor. All fibrotic tissue was excised. The wound was sutured in two layers, approximating the full thickness, including the endometrium. The first suture layer included four separate vicryl sutures, the second layer was a single double inverting suture. Adhesion barrier (hyaluronic acid) was used. After the first 50 procedures we additionally shortened the round ligaments in the case of an extreme retroflected uterus to minimise counteracting forces on the wound. The anatomic result was assessed at the end of the procedure by hysteroscopy. A urinary catheter was removed after approximately 12 hours. Applied surgical technique, findings, and perioperative and postoperative complications were registered. Details of the technique are described and illustrated in our step‐by‐step tutorial (J.A.F. Huirne, A.J.M.W. Vervoort , R. De Leeuw, H.A.M. Brölmann, W.J. Hehenkamp, Submitted).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the reduction of the main problem at 6‐month follow up. Reduction of the main problem was defined as—(1) a reduction in the number of days of postmenstrual spotting, (2) a reduction of dysmenorrhoea (visual analogue scale score), (3) the absence of intrauterine fluid or (4) a substantial enlargement of the RM of the niche (as surrogacy outcome for ease of embryo transfer) measured with transvaginal ultrasound (TVU).

Secondary outcome measures were postmenstrual spotting, spotting at the end of the menstruation, intermenstrual spotting, dysmenorrhoea (visual analogue scale 0–10), discomfort due to spotting (visual analogue scale 0–10), surgical outcomes (operating time, blood loss, satisfaction of the gynaecologist on a Likert scale [0–5 scale]), complications, quality of life (SF36),13 women's satisfaction, niche characteristics using TVU and presence of intrauterine fluid. Women completed questionnaires and a validated menstrual score card14 at baseline and 6 months after the intervention. Quality of life was assessed at 3 months and TVU was executed at baseline and between 3 and 6 months follow up. All women received sonohysterography at baseline, but given the discomfort, this was not repeated on a routine basis after the intervention and was not taken into account in our analyses.

Niche measurements

At baseline, women underwent TVU and sonohysterography to assess uterine and niche characteristics. We assessed the position of the uterus and fluid accumulation in the niche and uterine cavity. Using both TVU and sonohysterography, the niche was measured in the sagittal plane where the niche was the largest (maximum depth, thinnest RM). Niche depth and RM were assessed in a standardised manner (Figure S1a). The niche was also measured in the transverse plane where the largest dimensions were visible (Figure S1b).

Statistical analysis

All tests were performed two sided and a P‐value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The difference between follow‐up moment and baseline of continuous data were analysed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for related samples because of a nonparametric deviation of the data. A Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the presence of (midcycle) intrauterine fluid. Both satisfaction of patients with the treatment and of gynaecologists with the anatomic result reported on a Likert‐scale at 6 months were transformed into binary data using ‘dissatisfied’ (combining dissatisfied, very dissatisfied or neutral) or ‘satisfied’ (combining satisfied or very satisfied) as values. To exclude any confounding effect of amenorrhoea due to continuous use of hormones or pregnancy we executed a subgroup analysis excluding these women.

Results

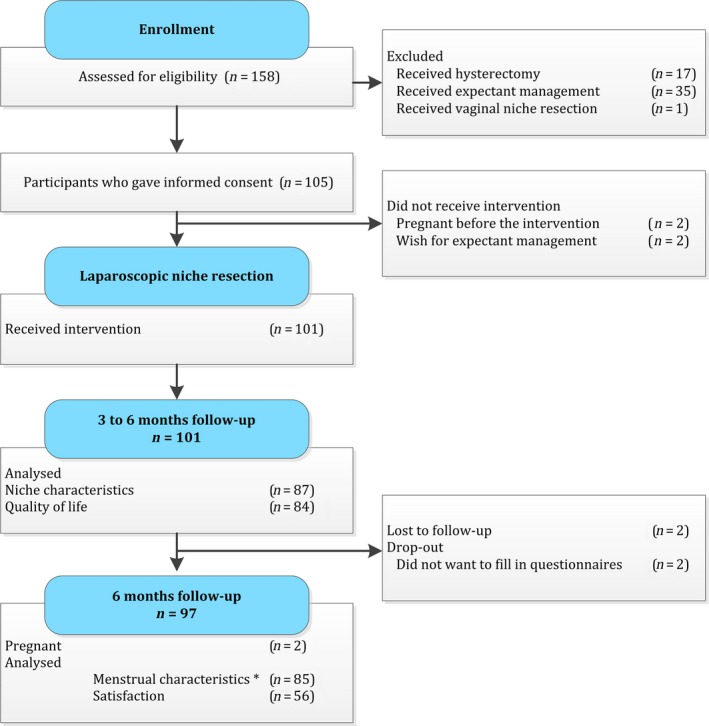

In total 158 women with a large niche visited our outpatient department in the study period because of symptoms or fertility problems. Of these women, 35 women received a conservative therapy (hormonal medication or expectant management). One woman with a very low niche received a vaginal niche resection. An additional 17 women without the desire to preserve the uterus received a laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. Finally 105 women gave informed consent and were included in the study. In two women we did not perform a laparoscopic niche resection because they became pregnant during the period when they were placed on the waiting list (mean of 6 months). Two women decided not to undergo the niche resection and wished for expectant management. In total, 101 women underwent a laparoscopic niche resection. Baseline characteristics are reported for all women. Two women were lost to follow up and two women did not want to fill out the questionnaires (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart. *Menstrual characteristics are analysed for women who experienced postmenstrual spotting at baseline (n = 85).

The flowchart (Figure 2) presents the number of women for whom data were present for the different outcomes.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. In total 55% of the women reported postmenstrual spotting, 11% dysmenorrhoea, 28% midcycle intrauterine fluid accumulation and 6% difficulties with the embryo transfer as their main problem and reason for participating in the study. However, most of the women reported more than one symptom; 84% postmenstrual spotting, 41% dysmenorrhoea, 46% midcycle intrauterine fluid accumulation and 21% problems during embryo transfer due to a distorted anatomy and 47% had previous unsuccessful assisted reproductive therapies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Parameter | n = 101 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.8 ± 10.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 24.5 ± 3.5 |

| Smoking | 22 (22.2%) |

| Use of anticoagulation | 2 (2.0%) |

| Parity | 1 (1–2) |

| Number of caesarean sections | 1 (1–1) |

| Time since last caesarean section (months) | 45 (28.0–62.0) |

| Main indication for the intervention | |

| Postmenstrual spotting | 56 (55.4%) |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 11 (10.9%) |

| Intrauterine fluid | 28 (27.7%) |

| Reconstructing anatomy for fertility treatment | 6 (5.9%) |

| Problems a | |

| Postmenstrual spotting | 85 (84.2%) |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 41 (40.6%) |

| Intrauterine fluid | 46 (45.5%) |

| Difficulties during the insertion of an embryo transfer or intrauterine insemination catheter | 21 (20.8%) |

| Wish to conceive | 89 (92.7%) |

| Subfertility (>1 year) | 71 (70.3%) |

| Fertility treatment in history | |

| Ovulation induction | 3 (3.1%) |

| Intrauterine insemination | 17 (17.5%) |

| In vitro fertilisation | 27 (27.8%) |

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or n (valid %).

Problems that were reported by the patient as one of the reasons for the intervention.

Surgical outcomes

Surgical outcomes are reported in the Supplementary material (Table S1). In total, five complications occurred during the niche resection: one reactive conversion to a laparotomy was needed because of an entry‐related vessel injury, one additional suture was needed to treat bleeding from a branch of an epigastric vessel, two muscular bladder lacerations were sutured during the same procedure and in one woman the uterus was perforated with the hysteroscope during the dissection of the bladder. In 30% of the women, additional shortening of the round ligaments was executed. During hysteroscopic evaluation immediately after uterine closure no niche could be identified in 56% and a niche of <1 mm depth in 44% of the women. Subjective evaluation of the anatomic result at the end of the intervention by the primary surgeon was satisfactory in all cases.

Reduction in reported symptoms or problems

In 80 women (79.2%) the main niche‐related problem was improved at 6 months follow up (Table S2).

Menstrual characteristics

Menstrual characteristics, except for dysmenorrhoea, are presented only for the women who experienced postmenstrual spotting at baseline (n = 85) (Table 2). Median postmenstrual spotting reduced from 9 days (interquartile range [IQR] 6–14 days) at baseline to 2 (IQR 0–4) days at 6 months follow up (P ≤ 0.01). Intermenstrual spotting reduced from 5 days (IQR 1–10) at baseline to 0 (IQR 0–0) days (P ≤ 0.01). Dysmenorrhoea reduced from a median score of 6.0 (IQR 4.0–8.0) at baseline to 4.0 (0.0–7.0) (P ≤ 0.01). Median discomfort due to spotting reduced from a score of 7.2 (IQR 5.0–9.0) to 0 (IQR 0.0–3.0) (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 2). A subgroup analysis, excluding women with amenorrhoea due to the use of continuous oral contraceptives, Mirena intrauterine device, gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist or pregnancy at follow up, gave consistent results for all menstrual outcomes for the 6 months follow up (Table S3).

Table 2.

Menstrual and niche characteristics

| Parameter | Baseline | 6 months | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding characteristics | |||

| Days of clear red blood loss during menstruation | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.81 |

| Total days of spotting (postmenstrual spottinga) | 9 (6–14) | 2 (0–4) | <0.01 |

| Intermenstrual spotting (days) | 5 (1–10) | 0 (0–0) | <0.01 |

| Discomfort due to spotting (VAS 0–10) | 7.2 (5.0–9.0) | 0 (0–3.0) | <0.01 |

| Dysmenorrhoea (VAS 0–10) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 4.0 (0–7.0) | <0.01 |

| Use of hormonal medication | |||

| Oral contraception | 13 (15.7%) | 19 (26.8%) | |

| Mirena intrauterine device | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | |

| Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist | 0 | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Continuous oral contraception | 0 | 2 (2.8%) | |

| Pregnancy | |||

| Pregnant | 2 | ||

| Niche characteristics | |||

| Number of women | 101 | 87 | |

| Position of uterus | |||

| Anteroverted | 35 (36.8%) | 40 (56.3%) | <0.01 |

| Stretched | 12 (11.9%) | 12 (16.9%) | 0.66 |

| Retroverted | 41 (43.2%) | 18 (25.4%) | <0.01 |

| Extreme retrovertedb | 7 (7.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0.77 |

| Median depth niche (mm) | 9.9 (7.2–13.4) | 4.2 (2.6–6.7) | <0.01 |

| Median residual myometrial thickness (mm) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 5.3 (4.0–6.9) | <0.01 |

| Intrauterine fluid | 42 (45.7%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.08 (OR 0.18; 95% CI 0.02–1.46) |

Data are reported as median (IQR) or as n (valid %). All menstrual characteristics are given for women with postmenstrual spotting at baseline, except for dysmenorrhoea. Dysmenorrhoea is reported for all women.

Postmenstrual spotting is defined as two or more days of intermenstrual spotting, or two or more days of brownish discharge immediately after the menstrual period when the total period of the menstrual bleeding exceeded 7 days.

Extreme retroverted was defined as a position of the uterus at an angle of ≤45 degrees with the cervix.

Sonographic characteristics of the niche and intrauterine fluid accumulation

Niche characteristics were measured in 87 out of 101 women (86.1%) between 3 and 6 months follow up (Table 2). The median depth of the niche reduced from 9.9 mm (IQR 7.2–13.4) to 4.2 mm (IQR 2.6–6.7) (P ≤ 0.01). Median residual myometrial thickness increased from 1.2 mm (IQR 0.8–1.7) to 5.3 mm (IQR 4.0–6.9) at follow up (P ≤ 0.01) (Figure S2).

In 48 women (57.1%) the RM was >5 mm and in 41 women (59.4%) the RM was thicker than 50% of the total myometrial thickness. Intrauterine fluid was seen in 46% of the women at baseline and in 6.5% at follow up (P = 0.08, OR 0.18 95% CI 0.02–1.46).

Quality of life and women's satisfaction

The quality of life was reported by 84 women (83.1%). The physical component of quality of life increased from 52.6 (IQR 46.3–57.8) to 55.2 (IQR 47.7–58.2) (P = 0.04). The total mental component scale did not change. The satisfaction questionnaire was filled out by 54 women (53.5%). At 6 months follow up 45 women (83.3%) were (very) satisfied (Table S4).

Additional interventions

Three women received a hysteroscopic niche resection before 6 months follow up because of persisting spotting and a small remaining niche after the laparoscopic niche resection. One woman received a gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist because of severe endometriosis and was down‐regulated until her following in vitro fertilisation cycle.

Learning curve and failed procedures

The median operating time was 17.5 minutes less in the second 51 women (132.5 minutes [IQR 110–161] (P ≤ 0.01) compared with the first 50 women (150 minutes [IQR 145–180]). Total blood loss and complication rate or failed procedures did not differ between these groups.

In 19 women (22.3% of women with spotting) postmenstrual spotting did not improve. In 12 women (11.9%) the RM did not enlarge and remained <3 mm. Dysmenorrhoea did not improve in 14 women (34.1%) and in five women (10.9%) accumulation of intrauterine fluid remained present.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the largest consecutive cohort on laparoscopic niche resection that has been published. Sonographic features improved as indicated by the increased RM. In 79.2% of women the main problem improved or resolved. Furthermore spotting, dysmenorrhoea and physical quality of life improved and women were very satisfied. Also, results are promising for patients with fertility problems or undergoing fertility therapy, since intrauterine fluid disappeared in most women and the niche depth decreased and residual myometrium increased, which might ease the possibility for inserting a catheter into the correct location for embryo transfer.

Strengths and limitations

As far as we are aware this is the first large prospective cohort study that evaluated the effect of a laparoscopic niche resection on niche‐related symptoms and/or fertility‐related problems and ultrasound findings at a follow up of 6 months. Women were all included consecutively and all inclusion and exclusion criteria have been well described. We used a standardised protocol for the niche resection, ultrasound evaluation of the uterus and niche measurement. We used validated questionnaires to evaluate quality of life and menstrual pattern.13, 14 We applied an additional analysis excluding women with amenorrhoea, which showed robustness of our results.

Our study's limitations include that results might be influenced by a learning curve in performing the niche resection; however, that is in fact what happens in reality but should be taken into account in counselling. A number of women had co‐morbidities such as endometriosis or adenomyosis, which might have led to an underestimation of the effect of the intervention on pain complaints or healing of the uterine wound. Additionally a substantial number of women had chronic pelvic pain and/or dyspareunia before the study, but we did not measure this as an outcome.

Niche characteristics were measured in 86.1% of participating women. A number of women did not come to the follow up or were evaluated in other hospitals because of the distance from their living address to our hospital.

We used a standardised method to measure niche characteristics, in which we agreed to measure the depth and the RM of the niche at the deepest point with the smallest RM. We learned that the use of only the measurements of the depth and the RM does not give an adequate image of the actual size of the niche. One can measure a niche with a comparable RM thickness, independent of the volume of the niche, this is illustrated in the Supplementary material (Figure S3). Given the proven association between niche volume and postmenstrual spotting,1 it would have been more appropriate if additional sagittal length, transversal width and/or three‐dimensional volume of the niche were measured. In addition, in case of a lateral branch, it is important to measure the niche sizes at the location of the ‘main’ niche and at the site of the lateral branch. These measurement advices are also supported by the Niche Task Force of the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. A Delphi study of these advices will be published soon.

An increase in RM is a surrogate outcome for the estimated ease of embryo transfer; however, take‐home‐baby rate is the best reproductive outcome but this requires a longer follow up.

Interpretation

Several case reports, case series and small prospective cohort studies with a maximum of 38 included women and one larger retrospective comparative study (n = 59) have been reported.5, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 Eleven articles (including a total of 65 women) reported a reduction or complete resolution of postmenstrual spotting; however, this was mostly not measured in a standardised way.5, 16, 18, 20, 21, 24, 26, 27, 29 Pelvic pain and/or dysmenorrhoea was reported to be resolved after laparoscopic niche resection in 36 women.5, 18, 21, 29 The residual myometrial thickness was increased after laparoscopic niche resection in all studies, but only three studies compared the outcomes with baseline measurements.15, 16, 17 Although these studies are mainly of small sample size or have a retrospective design, reported results are comparative to our findings.

Dysmenorrhoea only slightly improved in our study. Hypothetically this could be explained by a reduction of accumulation of blood in the niche and related uterine contractions, although this needs to be confirmed. Given the fact that we found co‐morbidity, such as endometriosis, in 22.8% of the women it cannot be expected that all pain symptoms will be resolved so it is important to include this information in pre‐operative counselling.

An interesting finding was the high score for spotting‐related discomfort (7.2 on a scale of 0–10) at baseline, which emphasises that spotting should not be neglected as a bothersome symptom and should be taken seriously by healthcare providers. The number of days of postmenstrual spotting is additional to the normal menstrual bleeding days. At 6 months follow up postmenstrual spotting was reduced in 77.7% of women. Physical quality of life improved significantly 6 months after the intervention, which is a valuable observation, but the clinical importance of this improvement in a general (not niche‐specific) quality of life questionnaire can be questioned. Improvement of outcomes was not related to the niche depth or RM; however, it would have been more appropriate to measure the volume to assess possible associations.

Future perspectives

Future research should focus on long‐term follow up of complaints, niche characteristics and fertility outcome and on identifying predictors for clinical failure.

Before offering a large surgical procedure with possible complications to women with spotting or dysmenorrhoea, we have the opinion that hormones should be offered first, although there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of hormonal therapy on niche‐related symptoms.36, 37 Future studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of hormonal therapies in comparison to hysteroscopic or laparoscopic niche resection, dependent on the size of the niche, the RM and future desire to conceive.

According to the IDEAL (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment, and Long‐term study) framework, developed to assess the stage of implementation of new surgical techniques,38 we may conclude that the phases of Idea and Development have been more or less completed and that the laparoscopic niche is entering the explorative phase. This means that its feasibility and safety have been proven and that it is time to set up comparative trials. In the current study we did not include women without niche‐related symptoms or problems with their fertility therapies. The benefit of a laparoscopic niche resection in asymptomatic women with large niches and subfertility should be studied in a randomised controlled trial before it is implemented for this indication in daily practice.

Conclusion

A laparoscopic niche resection reduces postmenstrual spotting by 7 days, it reduces discomfort due to spotting, dysmenorrhoea and the presence of intrauterine fluid in most women and enlarges the RM 6 months after the intervention. Despite the promising results, not all women benefited from the procedure and given the possible learning curve the intervention should preferably be executed in centres with special expertise only. Future studies need to be performed to identify which women and which specific niche characteristics will benefit most from this procedure. More studies and preferably randomised trials comparing this intervention with expectant management are needed to assess the real benefit of this procedure.

Disclosure of interest

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

JHU and HBR contributed to the design of this study. JHU, HBR and WHE performed the laparoscopic niche resections. AVE analysed the data and all the other authors contributed to the interpretation of data. AVE drafted the manuscript and JVI, LVO, WHE, HBR and JHU made substantial contributions to it. All the authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

Details of ethical approval

This study was approved by the National Central Committee on Research involving Human Subjects (CCMO—NL37922.029.11), by the ethics committee of the VU Medical Centre Amsterdam (mo. 2011/297) on 2 October 2011.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Niche measurements using sonography.

Figure S2. Median residual myometrium at baseline and between 3 to 6 months follow‐up.

Figure S3. Measurement of a comparable RM in two niches with different volumes.

Table S1. Surgical outcomes.

Table S2. Reduction of the main problem.

Table S3. Subgroup analyses on menstrual characteristics excluding women with amenorrhea due to continuous oral contraceptive use, levonorgestrel IUD or pregnancy.

Table S4. Quality of life* and women's satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women that participated in the study and our research physician Ted Korsen for her help with collecting data.

Vervoort AJMW, Vissers J, Hehenkamp WJK, Brölmann HAM, Huirne JAF. The effect of laparoscopic resection of large niches in the uterine caesarean scar on symptoms, ultrasound findings and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2018; 125:317–325.

Study registration: The study is registered in the ISRCTN register (ref. no. ISRCTN02271575) on 23 April 2013.

References

- 1. Bij de Vaate AJ, Brolmann HA, van der Voet LF, van der Slikke JW, Veersema S, Huirne JA. Ultrasound evaluation of the Cesarean scar: relation between a niche and postmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;37:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Voet LF, Bij de Vaate AM, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Long‐term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: a prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG 2014;121:236–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bij de Vaate AJ, van der Voet LF, Naji O, Witmer M, Veersema S, Brolmann HA, et al. Prevalence, potential risk factors for development and symptoms related to the presence of uterine niches following Cesarean section: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;43:372–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang CB, Chiu WW, Lee CY, Sun YL, Lin YH, Tseng CJ. Cesarean scar defect: correlation between Cesarean section number, defect size, clinical symptoms and uterine position. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;34:85–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marotta ML, Donnez J, Squifflet J, Jadoul P, Darii N, Donnez O. Laparoscopic repair of post‐cesarean section uterine scar defects diagnosed in nonpregnant women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20:386–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fabres C, Arriagada P, Fernandez C, Mackenna A, Zegers F, Fernandez E. Surgical treatment and follow‐up of women with intermenstrual bleeding due to cesarean section scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005;12:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jurkovic D. Cesarean scar pregnancy and placenta accreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;43:361–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Vaate AJ, Brolmann HA, van der Slikke JW, Wouters MG, Schats R, Huirne JA. Therapeutic options of caesarean scar pregnancy: case series and literature review. J Clin Ultrasound 2010;38:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bujold E, Jastrow N, Simoneau J, Brunet S, Gauthier RJ. Prediction of complete uterine rupture by sonographic evaluation of the lower uterine segment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Voet LF, Vervoort AJ, Veersema S, Bij de Vaate AJ, Brolmann HA, Huirne JA. Minimally invasive therapy for gynaecological symptoms related to a niche in the caesarean scar: a systematic review. BJOG 2014;121:145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacobson MT, Osias J, Velasco A, Charles R, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic repair of a uteroperitoneal fistula. JSLS 2003;7:367–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donnez O, Donnez J, Orellana R, Dolmans MM. Gynecological and obstetrical outcomes after laparoscopic repair of a cesarean scar defect in a series of 38 women. Fertil Steril 2017;107:289–96.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maarse M, BijdeVaate AJM, Huirne JAF, Brölmann HAM. De maandkalender; een hulpmiddel voor een efficiënte menstruatieanamnese. Utrecht: NTOG; 2012. pp. 231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanimura S, Funamoto H, Hosono T, Shitano Y, Nakashima M, Ametani Y, et al. New diagnostic criteria and operative strategy for cesarean scar syndrome: endoscopic repair for secondary infertility caused by cesarean scar defect. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Api M, Boza A, Gorgen H, Api O. Should cesarean scar defect be treated laparoscopically? A case report and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22:1145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J. Laparoscopic repair of wide and deep uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section. Fertil Steril 2008;89:974–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li C, Guo Y, Liu Y, Cheng J, Zhang W. Hysteroscopic and laparoscopic management of uterine defects on previous cesarean delivery scars. J Perinat Med 2014;42:363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siedhoff MT, Schiff LD, Moulder JK, Toubia T, Ivester T. Robotic‐assisted laparoscopic removal of cesarean scar ectopic and hysterotomy revision. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:681–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yalcinkaya TM, Akar ME, Kammire LD, Johnston‐MacAnanny EB, Mertz HL. Robotic‐assisted laparoscopic repair of symptomatic cesarean scar defect: a report of two cases. J Reprod Med 2011;56:265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klemm P, Koehler C, Mangler M, Schneider U, Schneider A. Laparoscopic and vaginal repair of uterine scar dehiscence following cesarean section as detected by ultrasound. J Perinat Med 2005;33:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kent A, Shakir F, Jan H. Demonstration of laparoscopic resection of uterine sacculation (niche) with uterine reconstruction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014;21:327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ciebiera M, Jakiel G, Slabuszewska‐Jozwiak A. Laparoscopic correction of the uterine muscle loss in the scar after a Caesarean section delivery. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2013;8:342–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeremy B, Bonneau C, Guillo E, Paniel BJ, Le TA, Haddad B, et al. Uterine ishtmique transmural hernia: results of its repair on symptoms and fertility. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2013;41:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahmoud MS, Nezhat FR. Robotic‐assisted laparoscopic repair of a cesarean section scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22:1135–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nirgianakis K, Oehler R, Mueller M. The Rendez‐vous technique for treatment of caesarean scar defects: a novel combined endoscopic approach. Surg Endosc 2016;30:770–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. La Rosa MF, McCarthy S, Richter C, Azodi M. Robotic repair of uterine dehiscence. JSLS 2013;17:156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dimitriou E, Mpalinakos P, Bardis N, Pistofidis G. Laparoscopic repair of a uterine wall defect on a caesarean scar. Gynecol Surg 2011;8:S76. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vakharia H, Afifi Y. Laparoscopic management of a cervical niche (sacculation) presenting with postmenstrual bleeding and sub‐fertility. Gynecol Surg 2014;11:206. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kostov P, Huber AW, Raio L, Mueller MD. Uterine scar dehiscence repair in GÇ£rendez‐vousGÇØ technique. Gynecol Surg 2009;6:S65. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garbin O, Vautravers A, Wattiez A. Laparoscopic repair of uterine scar dehiscence following caesarean section. Gynecol Surg 2011;8:S79. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tokawa M, Levy K, Douek V, Monteagudo A, Timor‐Tritsch IE. Uneventful pregnancy and cesarean delivery after successful robotic surgical repair of a vaginal‐birth‐after‐cesarean section (VBAC) created uterine fistula in the scar. Ultrasound Med Biol 2015;41:S147–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Istre O, Springborg H. Laparoscopic repair of uterine scar after C section. Gynecol Surg 2011;8:S76. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sangha R. Obstetric outcomes after robotic‐assisted laparoscopic repair of Cesarean Scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014;21:S199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y. A comparative study of transvaginal repair and laparoscopic repair in the management of patients with previous cesarean scar defect. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2016;23:535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tahara M, Shimizu T, Shimoura H. Preliminary report of treatment with oral contraceptive pills for intermenstrual vaginal bleeding secondary to a cesarean section scar. Fertil Steril 2006;86:477–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Florio P, Gubbini G, Marra E, Dores D, Nascetti D, Bruni L, et al. A retrospective case‐control study comparing hysteroscopic resection versus hormonal modulation in treating menstrual disorders due to isthmocele. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011;27:434–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nikkels C, Vervoort A, Mol B, Hehenkamp W, Huirne J, Brölmann H. Laparoscopic resection of uterine caesarean scar (?niche’); staging of innovation in the IDEAL classification based on a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;215:247‐53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.06.027. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Niche measurements using sonography.

Figure S2. Median residual myometrium at baseline and between 3 to 6 months follow‐up.

Figure S3. Measurement of a comparable RM in two niches with different volumes.

Table S1. Surgical outcomes.

Table S2. Reduction of the main problem.

Table S3. Subgroup analyses on menstrual characteristics excluding women with amenorrhea due to continuous oral contraceptive use, levonorgestrel IUD or pregnancy.

Table S4. Quality of life* and women's satisfaction.