Abstract

The prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating CD57-positive lymphocytes (CD57+ lymphocytes) in human solid tumors remains controversial. Herein, we conducted a meta-analysis including 26 published studies with 7656 patients identified from PubMed and EBSCO to assess the prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes in human solid tumors. We found that CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration significantly improved overall survival (OS) including 1 – year, 3 – year and 5 – year survival, and disease – free survival (DFS) in all types of solid tumors. In stratified analyses, CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration was significantly associated with better OS in hepatocellular, esophageal, head and neck carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, 5 – year survival in colorectal cancer, and 3 – year and 5 – year survival in gastric cancer, but not with 1 – year survival in gastric cancer, or 1 – year or 3 – year survival in colorectal cancer. In addition, high density of intratumoral CD57+ lymphocytes was significantly inversely correlated with lymph node metastasis and TNM stage of solid tumor. In conclusion, CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration leads to a favorable clinical outcome in solid tumors, implicating that it is a useful biomarker for prognosis and adoptive immunotherapy based on these cells may be a promising choice for treatment.

Keywords: tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes, favorable outcome, solid tumor, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Tumor microenvironment (TME) has proven to be closely related to the development and progression of cancer through diverse mechanisms including promoting immune suppression and stimulating angiogenesis [1]. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TICs) are considered to be the important components of TME [2]. Previous studies have revealed that TICs provided prognostic values in several types of solid tumors [3]. However, it is important to distinguish among a variety of immune cells as they may play differential roles in the TME. As the important component of adaptive immunity, the functions of CD57-positive lymphocytes in TME have drawn much attention in recent decades. Furthermore, these lymphocytes have been demonstrated to play significant roles in a number of human cancers.

CD57, also called human natural killer-1 (HNK-1) or LEU-7, has been shown to be present on CD4+ T, especially on CD8+ T and natural killer (NK) cells at the late stages of differentiation. It is generally applied to recognize the terminally differentiated cells with lower proliferative capacity and altered functional activities. CD57-positive lymphocytes (CD57+ lymphocytes) are often increased in solid tumors. Recent studies have associated tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes and cancer prognosis, but their results were controversial [4]. Thus, the value of these cells as a biomarker for prognosis and related immunotherapy need further assessment.

Herein, we performed this meta-analysis to quantitatively explore the correlation between high density of CD57+ lymphocytes and clinical outcomes such as overall survival (OS) and disease–free survival (DFS), thereby provided more evidence on the clinical value of CD57+ lymphocytes for prognostic prediction for solid tumors.

RESULTS

Search results

Total 9664 Literatures were searched and the results were displayed in Supplementary Figure 1. 26 studies containing 7656 patients with solid tumor were identified for the assessment of tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes [5–30]. All included studies were assessed using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), and met the inclusion criteria. Characteristics of these studies for OS, DFS and clinicopathological features including TNM stage etal have been exhibited in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 respectively.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Year | Tumor type | No. of Patients | Male/Female | median age (range) (year) | CD57+ lymphocytes: High/Low | Tumor stage | median follow-up date (months) | Survival | Quality Score (NOS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen, Y.F et al. [5] | 2016 | Colorectal cancer | 300 | 158/142 | < 60: 48%; ≥ 60: 52% |

NR | I–IV | 62.9 ± 29.3 | OS, DFS | 6 |

| Chaput, N. et al. [6] | 2013 | Colorectal cancer | 196 | 108/88 | (27, 86) | 56/100 | II–III | ≥ 24 | OS, DFS | 7 |

| Liska, V. et al. [7] | 2012 | Colorectal cancer | 150 | 93/57 | NR | 34/11 | NR | NR | OS | 6 |

| Sconocchia, G. et al. [8] | 2011 | Colorectal cancer | 1400 | NR | 71 (30, 96) | 189/1070 | NR | NR | OS | 6 |

| Menon, A. G. et al. [9] | 2004 | Colorectal cancer | 93 | 56/37 | < 50: 13%; ≥ 50: 87% |

30/62 | II–III | 73.2 (1.2, 223.2) |

DFS | 7 |

| Coca, S. et al. [10] | 1997 | Colorectal cancer | 186 | 110/76 | 63.4 (29, 84) | 25/132 | I–III | ≥ 60 | OS, DFS | 6 |

| Gao, Q. et al. [11] | 2012 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 206 | 186/20 | ≤ 49: 50.5%; > 49: 49.5% |

NR | I–III | 48.1 (3.4, 111.9) |

OS, DFS | 8 |

| Zhao, J. J. et al. [12] | 2014 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 163 | 131/32 | < 50: 57%; ≥ 50: 43% |

82/81 | NR | NR | OS | 7 |

| Liu, K. et al. [13] | 2015 | Gastric cancer | 166 | 41/125 | < 60: 60.8%; ≥ 60: 39.2% |

83/83 | I–IV | 65.88 | OS | 8 |

| Ishigami, S. et al. [14] | 2000 | Gastric cancer | 169 | 121/48 | 63.8 (30, 87) | 53/116 | NR | 63 | OS | 7 |

| Ishigami, Sumiya. et al. [15] | 2000 | Gastric cancer | 146 | 108/38 | 63.8 (30, 87) | 39/107 | I–IV | 87 | OS | 7 |

| Lv, L. et al. [16] | 2011 | Esophageal carcinoma | 181 | 141/40 | < 60: 58%; ≥ 60: 42% |

91/90 | I–IV | NR | OS | 8 |

| Hsia, J. Y. et al. [17] | 2005 | Esophageal carcinoma | 38 | 38/0 | < 60: 47.4%; ≥ 60: 52.6% |

14/24 | I–IV | NR | OS | 6 |

| Fang, J. et al. [18] | 2017 | Head and neck carcinoma | 78 | 57/21 | 60 (24, 82) | 34/44 | I–IV | 48 (29, 93) | OS | 7 |

| Taghavi, N. et al. [19] | 2016 | Head and neck carcinoma | 57 | 27/30 | 62.89 (34, 91) | 26/31 | NR | 29 (10, 85) | OS | 7 |

| Fraga, C. A. et al. [20] | 2012 | Head and neck carcinoma | 70 | 61/9 | 54.9 (36, 88) | 35/35 | NR | NR | OS | 6 |

| Karpathiou, G. et al. [21] | 2017 | Head and neck carcinoma | 152 | 128/24 | 58.5 (40, 88) | 71/81 | I–IV | 24 (3, 84) | OS | 7 |

| Hernandez-Prieto, S. et al. [22] | 2015 | Non-small cell lung cancer | 84 | 72/12 | 66.5 ±10.2 | 29/55 | I–II | 45.97 | DFS | 6 |

| Villegas, F. R. et al. [23] | 2002 | Non-small cell lung cancer | 50 | 49/1 | (50, 81) | 21/29 | I–IIIA | (6.2, 149.3) | OS | 6 |

| Takanami, I. et al. [24] | 2001 | Non-small cell lung cancer | 150 | 83/67 | 61 (30, 81) | 53/97 | I–IIIA | (60, 120) | OS | 8 |

| Donskov, F. et al. [25] | 2006 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | 120 | 85/35 | 57 (19, 74) | 34/51 | IV | 7 (32, 73) | OS | 7 |

| Li, K. et al. [26] | 2009 | Ovarian Cancer | 82 | 0/82 | (26, 80) | 33/49 | I–IV | (1, 154) | OS | 6 |

| Ohnishi, K. et al. [27] | 2016 | Endometrial Carcinoma | 79 | 0/79 | 59 (30, 74) | 37/38 | I–IV | NR | OS | 7 |

| Hansen, B. D. et al. [28] | 2006 | Melanoma | 27 | 16/11 | 49 (31, 65) | 13/12 | IV | 8.9 (1, 35) | OS | 6 |

| Blaker, Y. N. et al. [29] | 2016 | Lymphoma | 52 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 120 (15.6, 40.8) |

OS | 6 |

| Wangerin, H. et al. [30] | 2014 | Prostate cancer | 3261 | 3261/0 | 62 | NR | NR | 34 (1, 144) | OS | 6 |

Meta-analyses

OS

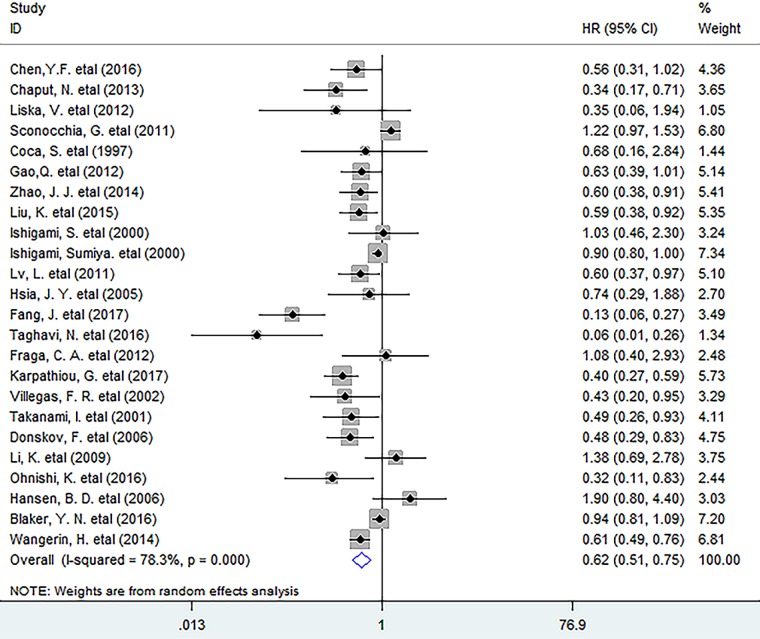

In this meta-analysis, the pooled results indicated that increased density of intratumoral CD57+ lymphocytes was significantly associated with better OS (HR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.75, P = 0.000) in solid tumors (Figure 1). More specifically, CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration significantly improved 1 – year (OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.77, P = 0.022) and 3 – year (OR = 3.09, 95% CI 2.03 to 4.70, P = 0.000) as well as 5 – year (OR = 3.48, 95% CI 2.24 to 5.42, P = 0.000) survival rate in patients. (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 1. Forest plots describing HR of the association between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and OS in solid tumors.

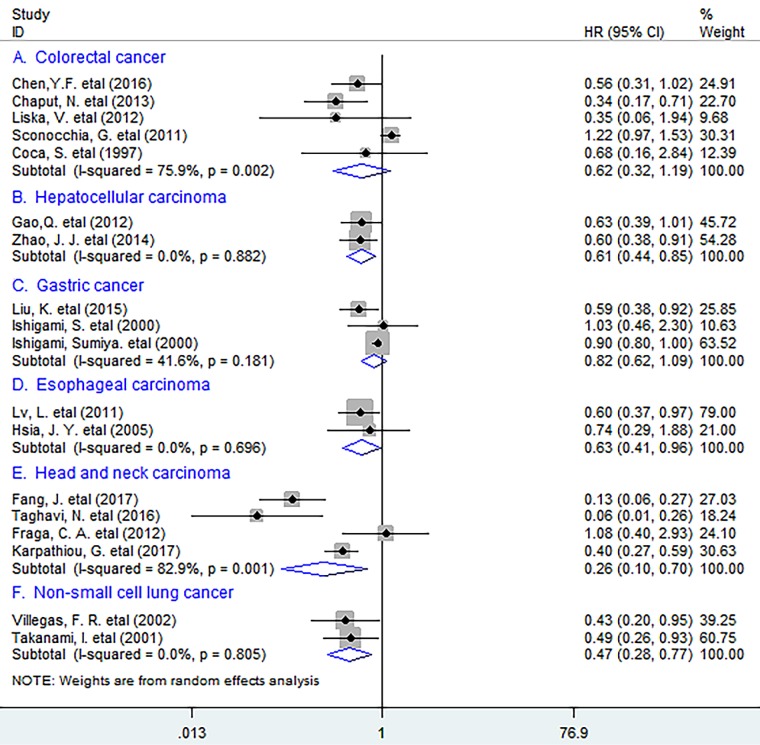

In subgroup analyses according to the types of cancer, the results indicated that CD57+ lymphocytes infiltrating into tumor significantly improved OS in hepatocellular cancer (HCC) (HR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.85, P = 0.003) and esophageal carcinoma (EC) (HR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.96, P = 0.033), with no heterogeneity being found (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.882; I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.696 respectively) (Figure 2). Similar results were observed between tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes and OS in head and neck carcinoma (HNC) (HR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.70, P = 0.007) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (HR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.77, P = 0.003). However, no significant correlation between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and OS in colorectal cancer (CRC) (HR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.19, P = 0.152) or gastric cancer (GC) (HR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.09, P = 0.167) was found.

Figure 2. Stratified analyses describing HRs of the association between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and OS.

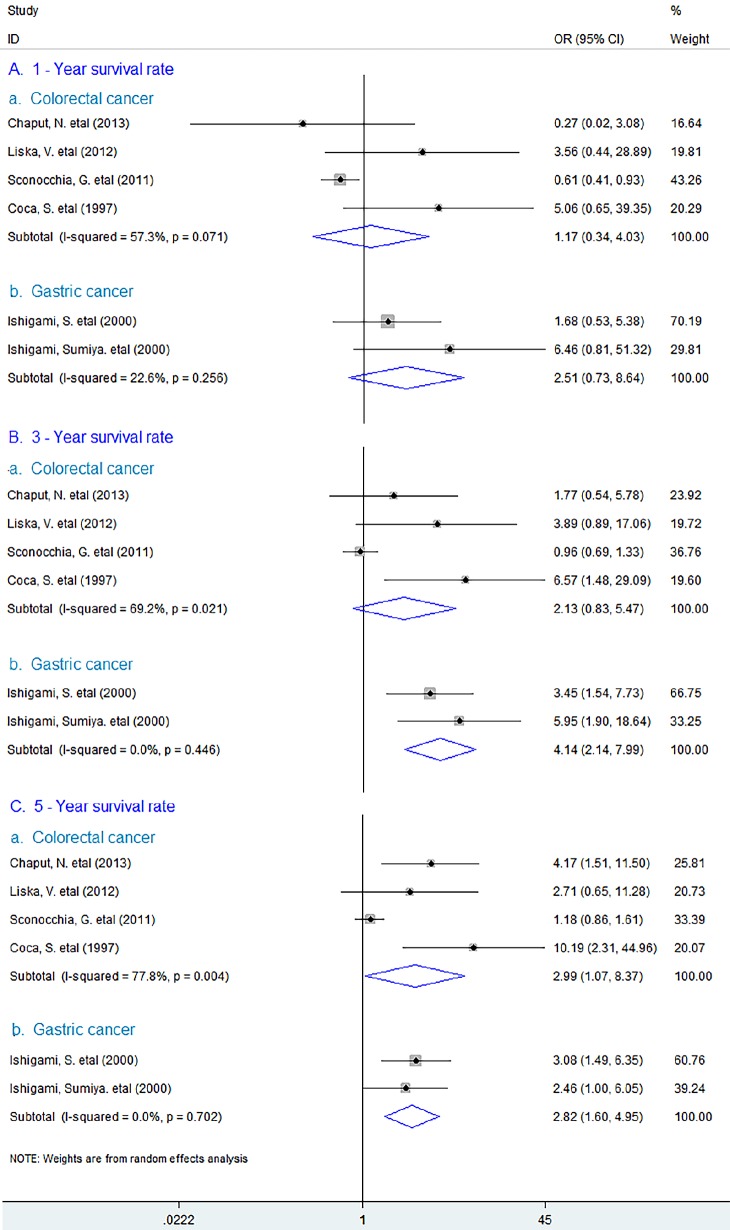

In addition, the study showed that increased density of CD57+ lymphocytes was associated with better 5 – year (OR = 2.99, 95% CI 1.07 to 8.37, P = 0.037), but not with 1 – year (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.03, P = 0.809) or 3 – year survival rate (OR = 2.13, 95% CI 0.83 to 5.47, P = 0.114) survival rate in CRC. Whereas in GC, CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration could significantly improve 3 – year (OR = 4.14, 95% CI 2.14 to 7.99, P = 0.000) and 5 – year (OR = 2.82, 95% CI 1.60 to 4.95, P = 0.000) except 1 – year survival rate (OR = 2.51, 95% CI 0.73 to 8.64, P = 0.144). (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Forest plots describing ORs of the association between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and OS at 1-year, 3-year and 5-year in colorectal and gastric cancer.

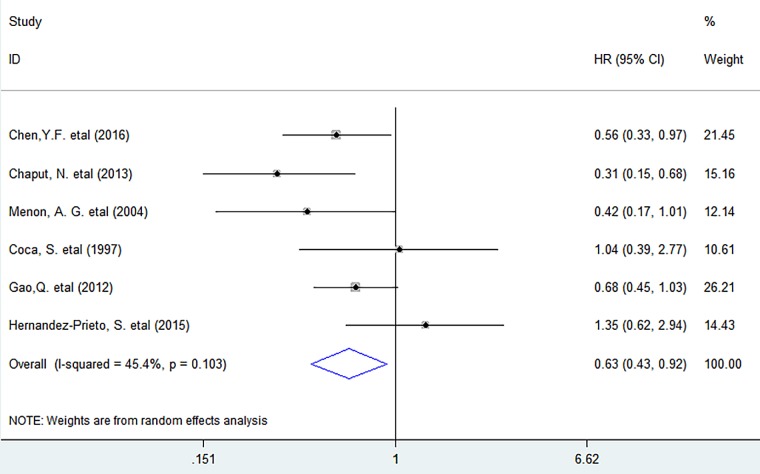

DFS

Meta-analysis showed that CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration significantly improved DFS (HR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.92, P = 0.016) in solid tumors, with no significant heterogeneity existing among studies (I2 = 45.4%, P = 0.103). (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Forest plots describing HR of the association between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and DFS in solid tumors.

We next investigated whether tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes correlated with clinicopathological features including lymph node metastasis etal of tumor. We found that CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration was significantly inversely associated with lymph node metastasis (OR = 0.36, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.50, P = 0.000) and TNM stage (OR = 2.14, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.11, P = 0.022), but not with tumor differentiation (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.17, P = 0.229), or vascular invasion (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.09, P = 0.525) of patients. (Supplementary Figure 3)

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses indicated that none of the studies included in the meta-analysis could significantly affect the overall HR for OS or DFS. (data not shown)

Publication bias

Funnel plot and Egger's test showed that there was no publication bias between CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration and OS (P = 0.984) or DFS (P = 0.492) in patients with solid tumor.

DISCUSSION

Lymphocytes play a vital role in protecting the host from pathogenic microorganisms especially viruses and cancer. In the last decades, although many studies have associated tumor-infiltrating CD57+ lymphocytes and prognosis of solid tumors, their results were not consistent even controversial. In the present meta-analysis, we found that CD57-positive terminally differentiated lymphocyte infiltration had a positive prognostic effect associated with survival in solid tumors especially in HCC, EC, HNC, NSCLC, CRC and GC. In addition, increased density of CD57+ lymphocytes inversely correlated with lymph node metastasis and TNM stage of solid tumor. These findings suggest that CD57+ lymphocytes are one of the important players in establishment of antitumor immunity in human solid tumors that retarding tumor progression.

The close association between increased CD57+ lymphocytes and improved survival of patients identified in this study may relate to the following reasons: first, CD57 expression in lymphocytes such as CD8+ T and NK cells correlates with increased expression of cytolytic enzymes such as granzyme A, granzyme B and perforin, suggesting that CD57+ lymphocytes possess the ability to cytolysis target cells including tumor cells [31]. Second, CD4+ T, CD8+ T and NK cells expressing CD57 antigen can produce more IFN-γ to inhibit the growth of tumor when stimulated [32]. In addition, CD57+ NK cells, known as one of the important components in adaptive immunity, can up-regulate MHC Class I and MHC Class II molecule on tumor cells through IFN-γ secretion to allow cytotoxic T – lymphocytes to recognize tumor – specific antigens thereby exerting antitumor effect [33]. More importantly, CD57+ NK cells can enhance the responses of T lymphocytes through the interactions between NK and dendritic cells (DC) that induce maturation and activation of DCs, [34]. with these cell – derived IFN-γ inducing T – cell polarization [35]. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that the CD57+ lymphocytes are able to potentiate the antitumor immune responses in the TME and fight against tumor growth and spread therefore improving survival.

However, some limitations exist in this study. Morphometric analyses for CD57+ lymphocytes used in included studies were not consistent. In addition, we were unable to gain the pooled results for some cancers such as renal cell carcinoma and ovarian cancer etal due to the lack of enough data.

In conclusion, CD57+ lymphocyte infiltration leads to a favorable clinical outcome of patients with solid tumor, implicating that it is a useful biomarker for prognosis and adoptive immunotherapy based on these cells may be a promising choice for treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

We searched PubMed and EBSCO for studies assessing the density of CD57+ lymphocytes in tumor tissue and survival in patients with solid tumor from 1996 to June 30th 2017. The searching keywords were (CD57 [Title/Abstract] OR HNK-1 [Title/Abstract] OR LEU-7 [Title/Abstract]) AND (neoplasms [Title/Abstract] OR tumor [Title/Abstract] OR cancer [Title/Abstract] OR carcinoma [Title/Abstract]) AND (prognosis [Title/Abstract] OR survival [Title/Abstract]). A total of 2900 and 6764 entries were identified in PubMed and EBSCO respectively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria of the meta-analysis were: studies included must have (1) been published as original articles; (2) evaluated human subjects; (3) CD57+ lymphocytes in tumor specimens were measured by immunohistochemistry (IHC); (4) provided hazard ratios (HRs) or Kaplan – Meier curves of high and low CD57+ lymphocyte density with overall survival (OS), and/or disease – free survival (DFS); (5) published in English.

We excluded studies that were not published as full texts, including commentary, case report, conference abstracts and letters to editors, studies that not report sufficient data to estimate hazard ratios (HRs); studies that detected lymphocytes not with marker ‘CD57’, ‘HNK-1’, or ‘LEU-7’, or detected CD57+ lymphocytes in metastases or not in tumor tissues.

Endpoints

OS and DFS were the endpoints used in this meta-analysis. OS was recorded as the primary endpoint, and the second endpoint was DFS. Cut-offs of CD57+ lymphocyte density defined by individual studies classified cancer patients into high- and low- groups.

Data extraction

Two authors (GM.H. and SM.W.) independently reviewed and extracted data using predefined data abstraction forms from each eligible study. Extracted information included first author's name, publication year, country, number of patients, median age, gender, Tumor, Lymph Node, Metastasis (TNM) stage, tumor differentiation, time of follow-up, technique used to quantify CD57+ lymphocytes, and cut-off value to determine high density of these cells. OS, DFS and clinicopathological data were extracted from the text, tables, or Kaplan – Meier curves for both high and low CD57+ lymphocyte density groups.

Quality assessment

The studies included in the meta-analysis were cohort studies. The quality of each included study was assessed using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) by two independent authors [36]. The studies with 6 scores or more were classified as high quality studies. A consensus NOS score for each item was achieved.

Statistical analysis

Extracted data were combined into a meta-analysis using STATA 12.0 analysis software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the chi-squared based Q-test or the I2 method [37]. Data were combined according to the random-effect model in the presence of heterogeneity [38], otherwise, the fixed-effect model was performed [39]. Sensitivity analysis was employed to assess the influence of each study on the pooled result. Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test [40]. were calculated to investigate potential publication bias. All P values were two-sided and less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLE

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the departments who helped in this study.

Abbreviations

- OS

overall survival

- DFS

disease-free survival

- HR

hazard ratio

- OR

odds ratios

- Cl

confidence interval

- TNM

Tumor

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- EC

esophageal carcinoma

- HNC

head and neck carcinoma

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- GC

gastric cancer

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- NR

not reported.

Footnotes

Author contributions

GM.H. conceived of the study, participated in its design, extracted data, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SM.W. participated in its design and the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81702803, GMH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Motz GT, Coukos G. The parallel lives of angiogenesis and immunosuppression: cancer and other tales. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:702–711. doi: 10.1038/nri3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leffers N, Gooden MJ, de Jong RA, Hoogeboom BN, ten Hoor KA, Hollema H, Boezen HM, van der Zee AG, Daemen T, Nijman HW. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes in primary and metastatic lesions of advanced stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:449–459. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0583-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen CM, White MJ, Goodier MR, Riley EM. Functional Significance of CD57 Expression on Human NK Cells and Relevance to Disease. Front Immunol. 2013;4:422. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Yuan R, Wu X, He X, Zeng Y, Fan X, Wang L, Wang J, Lan P, Wu X. A Novel Immune Marker Model Predicts Oncological Outcomes of Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:826–832. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaput N, Svrcek M, Auperin A, Locher C, Drusch F, Malka D, Taieb J, Goere D, Ducreux M, Boige V. Tumour-infiltrating CD68+ and CD57+ cells predict patient outcome in stage II–III colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liska V, Vycital O, Daum O, Novak P, Treska V, Bruha J, Pitule P, Holubec L. Infiltration of colorectal carcinoma by S100+ dendritic cells and CD57+ lymphocytes as independent prognostic factors after radical surgical treatment. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2129–2132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sconocchia G, Zlobec I, Lugli A, Calabrese D, Iezzi G, Karamitopoulou E, Patsouris ES, Peros G, Horcic M, Tornillo L, Zuber M, Droeser R, Muraro MG, et al. Tumor infiltration by FcgammaRIII (CD16)+ myeloid cells is associated with improved survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2663–2672. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon AG, Janssen-van Rhijn CM, Morreau H, Putter H, Tollenaar RA, van de Velde CJ, Fleuren GJ, Kuppen PJ. Immune system and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a detailed immunohistochemical analysis. Lab Invest. 2004;84:493–501. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coca S, Perez-Piqueras J, Martinez D, Colmenarejo A, Saez MA, Vallejo C, Martos JA, Moreno M. The prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:2320–2328. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2320::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Q, Zhou J, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, Song K, Huang XW, Sun J, Shi YH, Li BZ, Xiao YS, Fan J. Infiltrating memory/senescent T cell ratio predicts extrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:455–466. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao JJ, Pan QZ, Pan K, Weng DS, Wang QJ, Li JJ, Lv L, Wang DD, Zheng HX, Jiang SS, Zhang XF, Xia JC. Interleukin-37 mediates the antitumor activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: role for CD57+ NK cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5177. doi: 10.1038/srep05177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu K, Yang K, Wu B, Chen H, Chen X, Chen X, Jiang L, Ye F, He D, Lu Z, Xue L, Zhang W, Li Q, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells Are Associated With Prognosis of Gastric Cancer. Medicine. 2015;94:e1631. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Xiangming C, Iwashige H, Aridome K, Hokita S, Aikou T. Clinical impact of intratumoral natural killer cell and dendritic cell infiltration in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2000;159:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Che X, Iwashige H, Aridome K, Hokita S, Aikou T. Prognostic value of intratumoral natural killer cells in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv L, Pan K, Li XD, She KL, Zhao JJ, Wang W, Chen JG, Chen YB, Yun JP, Xia JC. The accumulation and prognosis value of tumor infiltrating IL-17 producing cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsia JY, Chen JT, Chen CY, Hsu CP, Miaw J, Huang YS, Yang CY. Prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in primary resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang J, Li X, Ma D, Liu X, Chen Y, Wang Y, Lui VWY, Xia J, Cheng B, Wang Z. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating immune cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:375. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taghavi N, Bagheri S, Akbarzadeh A. Prognostic implication of CD57, CD16, and TGF-beta expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2016;45:58–62. doi: 10.1111/jop.12320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraga CA, de Oliveira MV, Domingos PL, Botelho AC, Guimaraes AL, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Correa-Oliveira R, De Paula AM. Infiltrating CD57+ inflammatory cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis and prognostic significance. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2012;20:285–290. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318228357b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpathiou G, Casteillo F, Giroult JB, Forest F, Fournel P, Monaya A, Froudarakis M, Dumollard JM, Prades JM, Peoc'h M. Prognostic impact of immune microenvironment in laryngeal and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Immune cell subtypes, immuno-suppressive pathways and clinicopathologic characteristics. Oncotarget. 2017;8:19310–19322. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14242. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez-Prieto S, Romera A, Ferrer M, Subiza JL, Lopez-Asenjo JA, Jarabo JR, Gomez AM, Molina EM, Puente J, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Hernando F, Perez-Villamil B, Diaz-Rubio E, Sanz-Ortega J. A 50-gene signature is a novel scoring system for tumor-infiltrating immune cells with strong correlation with clinical outcome of stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:330–338. doi: 10.1007/s12094-014-1235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villegas FR, Coca S, Villarrubia VG, Jimenez R, Chillon MJ, Jareno J, Zuil M, Callol L. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancer. Lung cancer. 2002;35:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takanami I, Takeuchi K, Giga M. The prognostic value of natural killer cell infiltration in resected pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1058–1063. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1997–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Matsumura N, Suzuki A, Yagi H, Yamaguchi K, Baba T, Fujii S, Konishi I. Clinical significance of the NKG2D ligands, MICA/B, ULBP2 in ovarian cancer: high expression of ULBP2 is an indicator of poor prognosis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:641–652. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0585-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohnishi K, Yamaguchi M, Erdenebaatar C, Saito F, Tashiro H, Katabuchi H, Takeya M, Komohara Y. Prognostic significance of CD169-positive lymph node sinus macrophages in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:846–852. doi: 10.1111/cas.12929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen BD, Schmidt H, von der Maase H, Sjoegren P, Agger R, Hokland M. Tumour-associated macrophages are related to progression in patients with metastatic melanoma following interleukin-2 based immunotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:400–405. doi: 10.1080/02841860500471798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaker YN, Spetalen S, Brodtkorb M, Lingjaerde OC, Beiske K, Ostenstad B, Sander B, Wahlin BE, Melen CM, Myklebust JH, Holte H, Delabie J, Smeland EB. The tumour microenvironment influences survival and time to transformation in follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2016;175:102–114. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wangerin H, Kristiansen G, Schlomm T, Stephan C, Gunia S, Zimpfer A, Weichert W, Sauter G, Erbersdobler A. CD57 expression in incidental, clinically manifest, and metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:356427. doi: 10.1155/2014/356427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chattopadhyay PK, Betts MR, Price DA, Gostick E, Horton H, Roederer M, De Rosa SC. The cytolytic enzymes granyzme A, granzyme B, and perforin: expression patterns, cell distribution, and their relationship to cell maturity and bright CD57 expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:88–97. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez-Verges S, Milush JM, Pandey S, York VA, Arakawa-Hoyt J, Pircher H, Norris PJ, Nixon DF, Lanier LL. CD57 defines a functionally distinct population of mature NK cells in the human CD56dimCD16+ NK-cell subset. Blood. 2010;116:3865–3874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurosawa S, Harada M, Matsuzaki G, Shinomiya Y, Terao H, Kobayashi N, Nomoto K. Early-appearing tumour-infiltrating natural killer cells play a crucial role in the generation of anti-tumour T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1995;85:338–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:327–333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuritz SJ, Landis JR, Koch GG. A general overview of Mantel-Haenszel methods: applications and recent developments. Annu Rev Public Health. 1988;9:123–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.09.050188.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.