Abstract

Muscle contraction requires the physiology to adapt rapidly to meet the surge in energy demand. To investigate the shift in metabolic control, especially between oxygen and metabolism, researchers often depend on near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure noninvasively the tissue O2. Because NIRS detects the overlapping myoglobin (Mb) and hemoglobin (Hb) signals in muscle, interpreting the data as an index of cellular or vascular O2 requires deconvoluting the relative contribution. Currently, many in the NIRS field ascribe the signal to Hb. In contrast, 1H NMR has only detected the Mb signal in contracting muscle, and comparative NIRS and NMR experiments indicate a predominant Mb contribution. The present study has examined the question of the NIRS signal origin by measuring simultaneously the 1H NMR, 31P NMR, and NIRS signals in finger flexor muscles during the transition from rest to contraction, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion. The experiment results confirm a predominant Mb contribution to the NIRS signal from muscle. Given the NMR and NIRS corroborated changes in the intracellular O2, the analysis shows that at the onset of muscle contraction, O2 declines immediately and reaches new steady states as contraction intensity rises. Moreover, lactate formation increases even under quite aerobic condition.

Keywords: muscle, metabolism, bioenergetics, lactate, near infrared, oxygen

at the initiation of muscle contraction, the sudden surge in energy demand elicits a rapid physiological response and alters oxidative metabolism. How metabolism responds to the dynamic change in oxygenation and energy demand during a muscle contraction cycle poses a classic physiology question. To understand the role of O2, researchers often rely on noninvasive near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) methods to measure O2 level changes. The method is predicated on detecting the NIRS myoglobin (Mb) and hemoglobin (Hb) signals and on using the respective O2 dissociation constants to determine the cellular or vascular O2. Unfortunately, the NIRS Mb and Hb signals overlap, and the analysis cannot distinguish between changes in vascular vs. intracellular partial pressure of oxygen (Po2) (28). Nevertheless, most researchers have ascribed the NIRS signal in muscle to Hb. From this orthodox vantage, NIRS monitors the vascular Po2 (35).

However, studies have started to challenge the monolithic assignment of the NIRS signal to only Hb. Because 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can detect the distinct proximal histidyl NδH and Val E11 signals of Mb and Hb, it can follow the intracellular and vascular O2 changes in muscle oxygenation (16, 55, 91). Seal and human skeletal muscle experiments have expanded the approach to study the metabolic response during contraction, recovery, ischemia, reperfusion, and apnea (19, 69, 77). Indeed, muscle experiments have consistently shown that as V̇o2 rises with increasing contraction intensity, the intracellular Po2 does not increase. It actually decreases.

Because NMR can distinguish the Mb and Hb signals, it can help clarify the origin of the NIRS signals from muscle and gather appropriate insight on the role of the O2 supply in triggering the shift in metabolism. In that way, experiments can better utilize the advantages of NIRS and NMR techniques. NIRS can detect the composite Mb + Hb signal with better temporal resolution, while NMR can distinguish the Mb and Hb signal with better spectral resolution. NMR can better localize the Mb signal in tissue (90). The combined NIRS and NMR approach can then provide unique insights into some fundamental physiology questions: Must the cell cross an anaerobic threshold before lactate formation increases or does lactate form even under aerobic condition (13, 14, 38, 95). Aerobic lactate formation stands central to the intercellular and intracellular lactate shuttle hypotheses (11, 12). Do phosphocreatine (PCr) and lactate share the same O2 threshold? Perfused heart experiments certainly do not detect an identical critical Po2 (54).

In contrast to previous studies using a parallel experiment design, we have conducted simultaneous 1H NMR, 31P NMR, and NIRS measurements of finger flexor muscles during rest, contraction, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion to determine the relative contribution of Mb and Hb to the NIRS signal and to assess any hypoxia threshold triggering a shift in lactate and PCr metabolism (54, 91).

Both the NMR and NIRS data show a rapid and proportional increase in the deoxyMb signal with increasing exercise intensity, consistent with previous reports (69, 88). Cellular Po2 declines with increasing percent of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). NMR cannot detect any Hb contribution to the NMR signal during exercise. However, Hb contributes < 20% to the NMR signal during ischemia. The NMR results imply that the observed Mb + Hb NIRS signal from muscle reflects predominantly the Mb signal (91). Hb does not contribute significantly.

When the Po2 begins to drop during muscle contraction to a level well above the P50 of Mb, PCr and pH levels change. Yet at the same cellular Po2 during ischemia, PCr and pH levels remain relatively constant. O2 level alone does not control metabolism. In fact, the lactate level, derived from the pH values observed in the 31P spectra indicates that the cell has already started to ramp up lactate formation at Po2 well above any apparent hypoxia threshold (46).

The study then shows that NIRS detects primarily Mb oxygenation, intracellular Po2 declines in proportion to MVC and metabolism, lactate level begins to change well before any apparent hypoxia threshold, and metabolism differs sharply at the same cellular Po2 but contrasting physiological conditions. These findings provide then unique perspectives on measuring tissue O2 and on assessing the role of O2 in controlling muscle bioenergetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Four healthy males (37 ± 13 yr) volunteered and provided written, informed consent to take part in the study. All experimental procedures were undertaken with the approval of the Timone University-Hospital Ethics Committee and in accordance with the standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (2000). In the 24 h before the study session, subjects were asked to refrain from any intense physical activity.

Study design.

Each subject participated in a specific session that measured simultaneously the NIRS/MRS (magnetic resonance spectroscopy) signals from the superficial finger flexor muscles during a rest-exercise-recovery-ischemia-reperfusion protocol. A deflated pressure cuff was initially positioned on the upper arm of the subject. The subject then sat on a chair close to the magnet and inserted the belly of his forearm horizontally into the magnet bore above a 50-mm-diameter double-tuned 1H/31P surface coil. This coil was part of a home-built ergometer that allowed muscle contraction inside the superconductive magnet (Bruker Biospec 47/30) as previously described (83).

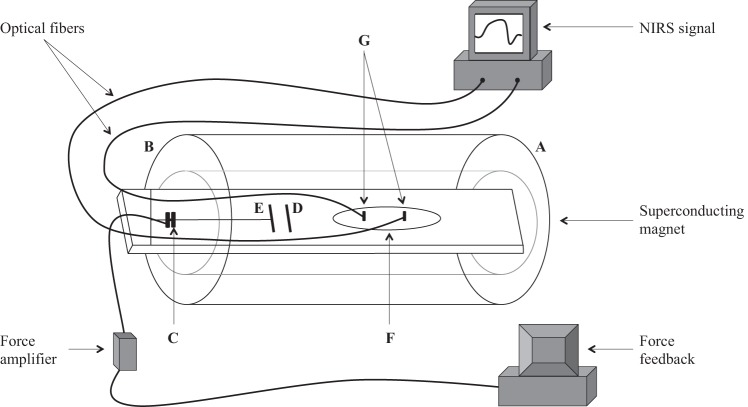

The ergometer consisted of two independent, fully adjustable handle bars, which allowed the subject to position the belly of the forearm muscles above the surface coil (Fig. 1). The distal bar was connected to a force transducer, which measured the intensity of each isometric contraction. The force signal was amplified and recorded on a personal computer using WinATS software version 6.5 (Sysma, Aix-en-Provence, France). The force level was also displayed on a digital meter visible to both subjects and researchers. Two nonmagnetic optical fibers were also positioned in the center of the surface coil adjacent the superficial finger flexor muscles. The fibers were connected to the NIRS spectrometer (Oxymon, Artinis) located ~5 m away from the superconductive magnet.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the ergometer. The arm reaches into the magnet from side A toward side B, and the fingers grab handle E, while the palm rests against handle D. A force transducer (C) measures the contraction force and sends the signal to a home-built amplifier. A meter then displays the measured force as a feedback to the subject, who then adjusts the contraction intensity to reach the targeted force at each % maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) step. The belly of the forearm rests on top of the 1H/31P double-tuned surface coil (F) and also on top of the coplanar near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) optodes (G). Optical fibers transmit the NIRS signals to a personal computer, which monitors and records, every 0.1 s, the NIRS signal.

The forearm was placed approximately at the same height as the shoulder to ensure a good venous return. A practice session first familiarized the subject with the ergometer and the exercise regimen. Maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) of the superficial finger flexor muscles was then determined through three repeated measurements separated by at least a 1-min interval. Subjects were asked to squeeze the handle bars as strongly as possible and were verbally encouraged during the contraction. The highest isometric force was then recorded as the MVC for each subject.

Exercise-ischemia-reperfusion protocol.

Exercise consisted of ramp, repeated isometric finger flexion performed at three different intensities: 10%, 20%, and 30% of the MVC, without any intervening rest period. Each exercise step was performed in a 2-min trial and consisted of 80 total isometric contractions. The subject listened to a beeper that signaled the subject to begin squeezing the bars to achieve the desired %MVC. A digital meter gave each subject a visual feedback of the generated contraction force and target level required for each exercise step. A 2nd beep then signals the subject to relax. Each beep signal was separated by a 1.5-s period. During a given 3-s contraction cycle interval, contraction lasted 1.5 s and relaxation lasted 1.5 s. The pulse program triggered the spectrometer to initiate an acquisition pulse in synchrony with each beep and to collect 1H and 31P NMR signals during each contraction cycle.

Synchronizing the NMR acquisition with muscle contraction ensured the coil and NIRS detector would repeatedly sample signals from approximately the same spatial location in the muscle. Such an experimental approach minimized errors from movement artifacts and improved signal averaging.

An 8-min recovery period followed the 6-min exercise session. After the recovery period, a pressure cuff around the arm was rapidly inflated (within 2 s) to 200 mmHg (well above the systolic pressure) and was maintained for a 6-min period. The cuff pressure was then rapidly released.

NMR.

A pulse sequence interleaved 31P and 1H signal acquisitions on a 4.7-T Bruker Biospec 47/30 magnet system, and the data transfer utilized the Multi-ScanControl Tool (MSC, Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany) as previously described (3). Since longitudinal relaxation times of 31P and 1H metabolites differ significantly, the sequence design allowed for the accumulation of a number of 1H scans between the 31P scans. 31P-MRS spectra were acquired with a pulse-acquisition sequence using a 250-µs single square pulse, 120-ms acquisition time, and a 1.38-s relaxation time. The total repetition time was 1.5 s (7). The analysis used data averaged over a 30-s block (20 accumulations).

1H MRS signal of the proximal histidyl NδH of the deoxymyoglobin (DMb) resonance was selectively excited using a Gaussian pulse. Signals were acquired with a 14-ms repetition time; 214 transients were collected in a 3-s contraction interval. The analysis used data averaged over a 60-s block (4,280 accumulations). Consequently, 31P and 1H signal acquisition had a 30-s and 60-s time resolution, respectively.

The MSC recorded automatically the 1H and 31P NMR data in separate data storage bins. Data were then processed using the advanced method for accurate, robust, and efficient spectral fitting (AMARES) (93) interfaced within the IDL environment (Interactive Data Language, Research Systems, Boulder, CO) as previously described (58). A prior knowledge algorithm was used to quantitate the 31P ATP multiplets and the single Mb peak as previously described (57).

The inorganic phosphate (Pi) chemical shift provided a means to estimate intracellular pH using Eq. 1 (2):

| (1) |

where pK = 6.75, δA = δppm of [H2PO4]− at 3.27 ppm, δB = δppm of [HPO4]2− at 5.69, and δo = δppm of observed Pi. The δppm was referenced to the PCr chemical shift.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS).

NIRS signal was collected throughout the protocol, simultaneously with interleaved 31P and 1H MRS signal acquisitions. A continuous-wave near-infrared spectrometer (Oxymon Mk III, Artinis Medical Systems) recorded the NIRS signal at a 10-Hz sampling rate with two probes connected by optical fibers positioned 4.5 cm apart on the belly of the forearm. The software supplied with the system (Oxysoft, Artinis Medical Systems) converted the NIRS signals into relative concentrations of deoxymyoglobin (DMb) and deoxyhemoglobin (DHb) together with the corresponding oxygenated forms, oxymyoglobin (MbO2) and oxyhemoglobin (HbO2). The Oxymon software used the 850-nm signal intensity to indicate (MbO2 + HbO2) level and the 760-nm signal intensity to indicate the (DMb + DHb) level. The difference between the 760-nm and 850-nm signal provided an index of the relative change between composite Hb and Mb oxygenation (47, 91).

The NIRS data were sampled at 10 Hz (0.1 s time resolution), and the baseline values were first set at rest and then normalized to the signal obtained at the end of the 6-min ischemia period, which the analysis assumed to correspond to the anoxia condition and total deoxygenated Mb and Hb states. Half-time (t1/2) (time required to reach half the value of the observed change) of oxygen desaturation/saturation was calculated for each transition (different exercise intensities, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion). The analysis used a 29-point running average on the NIRS data to smooth the curves.

VPCr and kPCr determination.

The PCr recovery kinetic parameters were determined by fitting the PCr time-dependent changes during the recovery period to a monoexponential curve described by the equation:

| (2) |

where [PCr]ex is the concentration of PCr measured at end of exercise, [PCr]rec refers to the amount of PCr resynthesized during the post-exercise recovery period, and k the PCr resynthesis rate constant. The analysis used the PCr resting level of 36 mM (82). The initial rate of PCr resynthesis (VPCr) was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where the difference between the total PCr ([PCr]total) and the PCr at the end of exercise ([PCr]ex) indicates the amount of PCr consumed during exercise. VPCr provided an index of the oxidative phosphorylation capacity (2, 57, 68).

Lactate determination.

∆[Lac] was calculated from the ∆pH as reflected in the chemical shift of the Pi signal in the 31P NMR spectra (46). The method derived from the reaction stoichiometry between [H+] released during Lac deprotonation. Subsequent binding of H+ to histidine in proteins, carnosine, and Pi established the relationship between ∆Lac and ∆H+ according to the following equation:

| (4) |

where [histidine] = 0.036 M, [carnosine] = 0.014 M, khist = 3.162 × 10−7 M, kcarn = 5.011 × 10−8 M, and kPi = 1.549 × 10−7 M. [Pi] and [H+] were determined experimentally from 31P spectra. PCr, ATP, and Pi levels were determined from integrated areas of the PCr, β-ATP, and Pi signals, respectively. The areas were then normalized to the resting state values.

Tissue Po2.

1H spectra provided information related to the deoxyMb (DMb) signal and the corresponding increase indicated an increased cellular deoxygenation. The Mb desaturation magnitude was normalized to the maximal amplitude recorded at the end of the 6-min ischemia period as previously described (69, 91). Po2 was calculated according to the following equation:

| (5) |

where the 1H NMR signal intensity of DMb at the end of ischemia was set to 100% deoxyMb or [Mb], [MbO2] = 100 − [Mb], and P50 = 2.93 at 39°C.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with Statistica software version 9 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). Normality was checked using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare parameters at the different steps of the protocol (rest, 10%, 20%, and 30% MVC exercise, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion). When a main effect or a significant interaction was found, a Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis was performed. Significance was accepted when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the experimental setup. The arm reaches into the magnet from side A toward side B, and the fingers grab handle E, while the palm rests against handle D. A force transducer (C) measures the contraction force and transmits the signal to a home-built amplifier, which increases the signal gain. The signal gets relayed to a display meter, which serves as a feedback for the subject to adjust the contraction force to reach the required target level at each %MVC step. The belly of the forearm rests on top of the 1H/31P double-tuned surface coil (F) and also the optodes (G). Optic fibers carry the NIRS signal to a personal computer, which monitors and records continuously the NIRS signal sampled at 10 Hz.

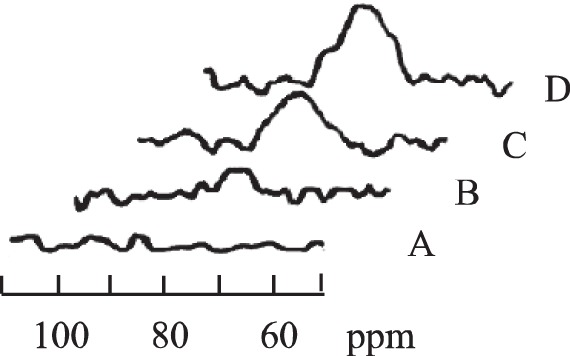

Figure 2 shows representative 1H NMR spectra from the forearm at rest (A), 10% MVC (B), 20% MVC (C), and 30% MVC (D). The signal at 78 ppm arises from the proximal histidyl-NδH of DMb. At rest, no detectable signal of DMb appears. At increasing %MVC, the contraction force produces a rising DMb signal intensity. Increasing signal intensity indicates declining levels of tissue oxygenation. The DMb signal rises in proportion to increasing %MVC. No other signal appears in the spectral region. At 30% MVC, the analysis has ascribed the bumps upfield and downfield of the DMb to noise, since their apparent maxima do not appear consistently at the same chemical shift and do not correspond to any assignable peak. The composite peak does not display the presence of DHb, which has intrinsic characteristics of a paramagnetically broadened peak. The DMb signal disappears quickly at the end of exercise and remains undetectable throughout the recovery period.

Fig. 2.

1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signal of the proximal histidyl NδH of deoxyMb at rest (A), 10% MVC (B), 20% MVC (C), and 30% MVC (D).

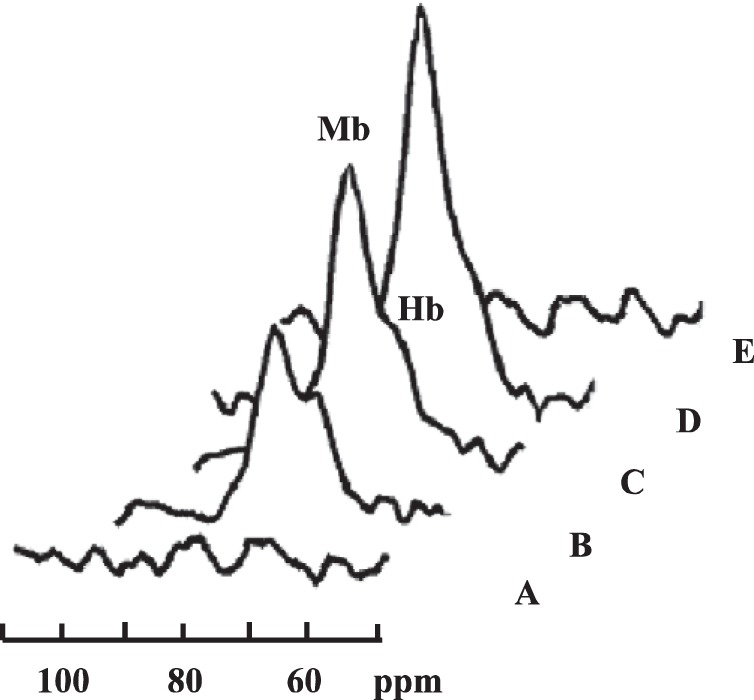

NMR cannot detect any DMb signal during the recovery period (Fig. 3A). With ischemia, the 1H NMR signal of the proximal histidyl NδH of DMb appears once the cuff has inflated to 200 mmHg, well above the systolic pressure (Fig. 3, B–D). The DMb signal approaches gradually an intensity plateau in ~6 min. Upon the release of the cuff pressure, the DMb signal disappears rapidly (Fig. 3E). An additional peak on the shoulder of the Mb signal appears at 73 ppm. Previous studies have assigned the peak to the proximal histidyl NδH of the β subunit of deoxyHb (DHb) (77, 89, 91). The DHb signal comprises < 20% of the total DMb and DHb signals. During muscle contraction, NMR does not detect any DHb signal.

Fig. 3.

1H NMR signal of the proximal histidyl NδH of deoxy Mb (A) at the end of recovery and at time periods following cuff inflation: 2 min (B), 4 min (C), and 6 min (D). Releasing the cuff pressure restores the blood flow, and the deoxy Mb signal disappears (E). The peak on the shoulder of the Mb signal arises from the proximal histidyl NδH signal from the β subunit of deoxy Hb as previously assigned (91).

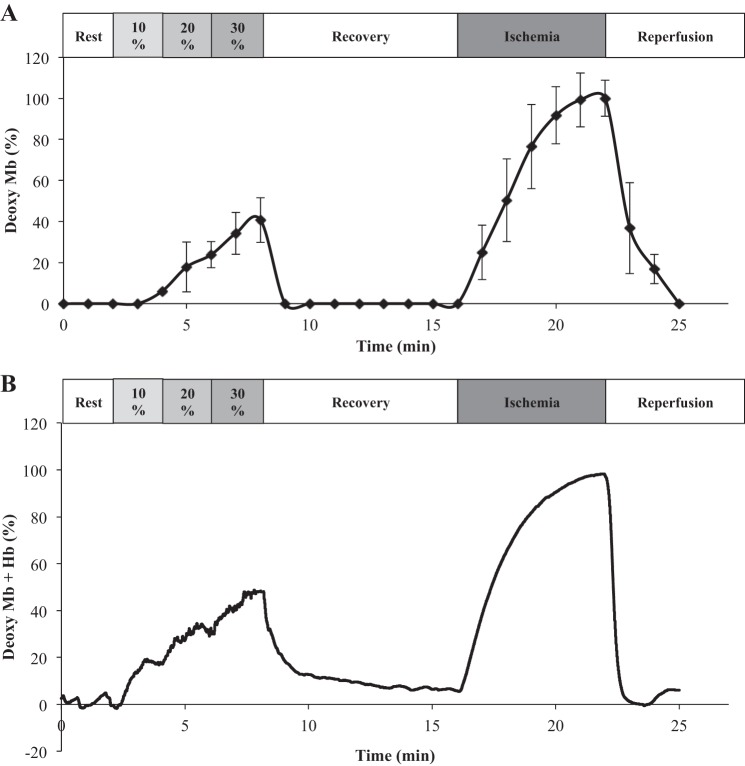

The time-dependent changes in the NMR signal of DMb during the exercise-rest-ischemia-reperfusion protocol show stepwise increase with each rising %MVC (Fig. 4A). Once muscle contraction ceases, O2 returns immediately as indicated by the rapid disappearance of the DMb signal. DMb remains undetectable throughout the recovery period. At the start of ischemia, the DMb signal reappears, and its intensity increases with time. After 6 min, the DMb signal approaches a plateau intensity, which the analysis has assumed to reflect the 100% deoxygenated Mb state. Normalizing the DMb signal to the maximum signal as the totally deoxygenated Mb state provides an index of the relative DMb change throughout the exercise, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion protocol (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Graph of time-dependent change in the NMR and NIRS signals during the exercise-recovery-ischemia-reperfusion protocol. The analysis assumes the signal intensity at the end of the ischemia period corresponds to the anoxic state and deoxymyoglobin (DMb) = 100%. A: the NMR signal of DMb does not appear during rest, recovery, and reperfusion. It increases progressively with %MVC and with ischemia. B: NIRS also detects no DMb + deoxyhemoglobin (DHb) signal at rest, recovery, and reperfusion. At each %MVC step, the NIRS DMb + DHb signal increases rapidly to a new steady state. The NIRS signal declines rapidly to its baseline level during recovery. During ischemia, the DMb + DHb signal also rises and approaches a plateau within 6 min. Once blood flow returns, the NIRS signal disappears rapidly.

Table 1.

NMR and NIRS Values

| Exercise |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% MVC | 20% MVC | 30% MVC | Recovery | Ischemia | Reperfusion | |

| NMR measurements | ||||||

| deoxyMb, % | 6* | 23 ± 7 | 40 ± 9 | NM | 100 | NM |

| Po2, mmHg | 45.90* | 9.81 | 4.40 | NM | ND | NM |

| ΔPCr, % | 11 ± 4 | 20 ± 7 | 34 ± 10 | NM | 7 ± 2 | NM |

| ΔpH | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.21 ± 0.14 | NM | 0.05 ± 0.05 | NM |

| VPCr, mM/min | NM | NM | NM | 15.6 ± 3.5 | NM | NM |

| kPCr, min−1 | NM | NM | NM | 1.16 ± 0.19 | NM | NM |

| t1/2 PCr, min | NM | NM | NM | 0.27 ± 0.04 | NM | NM |

| t1/2 DMb, min | NM | NM | NM | NM | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| NIRS measurements | ||||||

| deoxyMb-Hb, % | 19 ± 10 | 33 ± 18 | 47 ± 32 | NM | 100 | NM |

| Po2, mmHg | 12.5 | 5.95 | 3.3 | NM | NM | NM |

| t1/2 DMb-DHb, min | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD. DMb and DMb-Hb signals are normalized to the signal at end of ischemia as 100%. ΔPCr and ΔpH, change relative to resting value. VPCr and kPCr, initial rate and the rate constant of PCr resynthesis, respectively; t1/2 PCr, t1/2 DMb, and t1/2 DMb-DHb, half-time of PCr, deoxyMb, and deoxyMb-Hb kinetics, respectively. Po2 calculation used a P50 of 2.93 mmHg. NM, not measurable; ND, not defined.

DMb signal was not detectable in all subjects.

Figure 4B illustrates the corresponding evolution of the NIRS signal, which comprises of contribution from both DMb and DHb. At each MVC step, the improved time resolution of the NIRS over the NMR measurement confirms that DMb + DHb has reached rapidly a new steady state. NIRS also shows a decreasing O2 level as exercise intensity increases. During the recovery period, the NIRS signal declines rapidly to its baseline level. With ischemia, the NIRS signal rises again and approaches a plateau. The analysis assumes the plateau signal intensity at the end of the ischemia period reflects the anoxic state, totally deoxygenated Mb and Hb states, and has normalized all the NIRS signal relative to ischemia end-point signal intensity. Upon reperfusion, the NIRS signal disappears rapidly. Both the NMR and NIRS measurements corroborate.

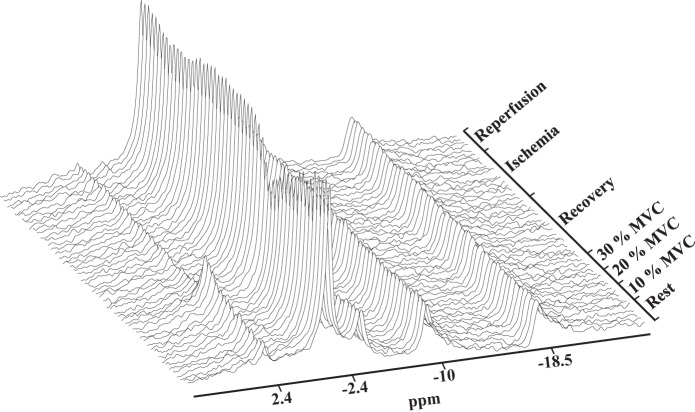

Figure 5 shows the corresponding 31P NMR spectra collected during the experiment protocol. Each spectrum corresponds to a 30-s signal accumulation. During exercise, the PCr signal loses intensity as %MVC increases. Pi intensity increases. The Pi chemical shift also changes. During the other periods, including the ischemia period, the PCr level does not change markedly. Throughout the experimental protocol, ATP remains constant.

Fig. 5.

31P NMR spectra during exercise-recovery-ischemia-reperfusion protocol. Each spectrum reflects 30 s signal accumulation.

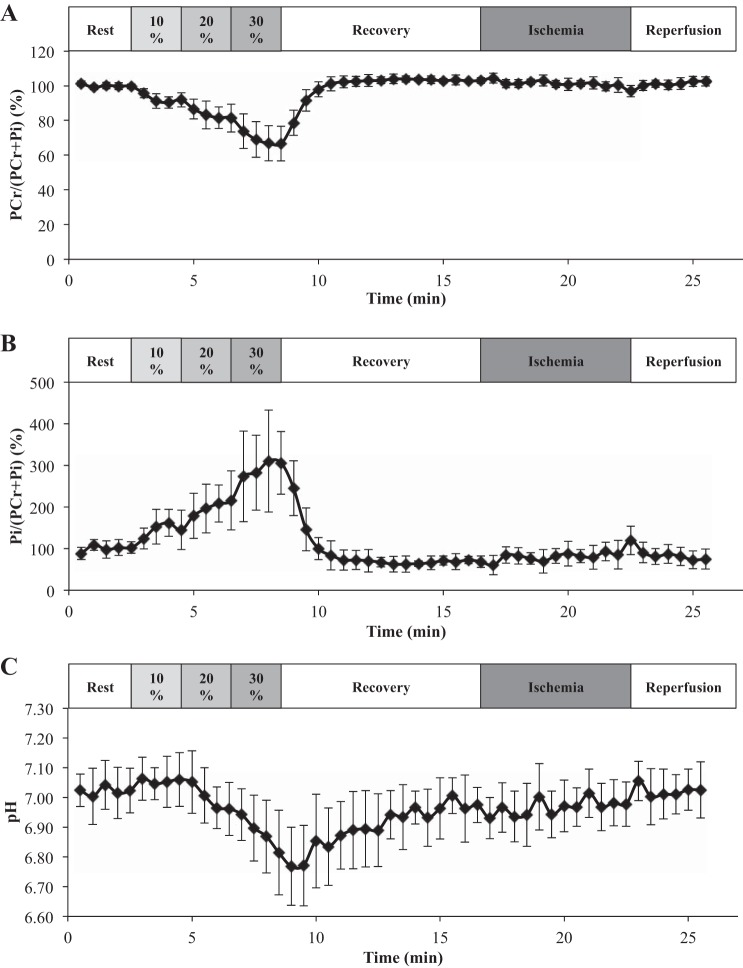

Figure 6A graphs the time-dependent change in PCr/(PCr + Pi), which declines during exercise (Table 2). At each %MVC step, PCr/(PCr + Pi) reaches a new steady state. During recovery, PCr returns to its resting level. During ischemia and reperfusion, PCr/(PCr + Pi) does not change significantly. Similarly, Fig. 6B shows that Pi/(PCr + Pi) increases as %MVC increases and also reaches new steady states. It returns to resting level after recovery. PCr displays no significant change during ischemia and reperfusion (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

A: time-dependent change in PCr/(PCr + Pi) during the exercise-recovery-ischemia-reperfusion protocol. PCr/(PCr + Pi) declines during exercise but returns to its resting level during recovery. During ischemia and reperfusion, PCr/(PCr + Pi) level does not change significantly. B: time-dependent change in Pi/(PCr + Pi) during the course of exercise-recovery-ischemia-reperfusion protocol. Pi/(PCr + Pi) level increases with %MVC and returns to resting level during recovery. No change occurs during ischemia and reperfusion. C: pH decreases during exercise and returns slowly to its initial level during recovery. Ischemia and reperfusion do not perturb the pH. PCr, phosphocreatine; Pi, inorganic phosphate.

Table 2.

Metabolic and physiological response at different exercise intensities

| Intensity, %MVC | PCr/(PCr + Pi), % | Pi/(PCr + Pi), % | pH | ΔLac |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (rest) | 100 | 100 | 7.02 ± 0.07 | 0 |

| 10 | 89 ± 4 | 220 ± 25 | 7.01 ± 0.06 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| 20 | 80 ± 7 | 275 ± 68 | 6.94 ± 0.08 | 4.9 ± 1.1 |

| 30 | 66 ± 10 | 358 ± 86 | 6.81 ± 0.14 | 7.6 ± 2.9 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD. ΔPCr and ΔpH, change relative to resting value. NM, not measurable; ND, not defined.

The chemical shift of the Pi leads to an estimate of the cellular pH. The pH value decreases as exercise intensity increases (Table 2). It recovers slowly to its resting value after exercise. However, the pH value does not change significantly during ischemia and postischemic-reperfusion (Fig. 6C and Table 1).

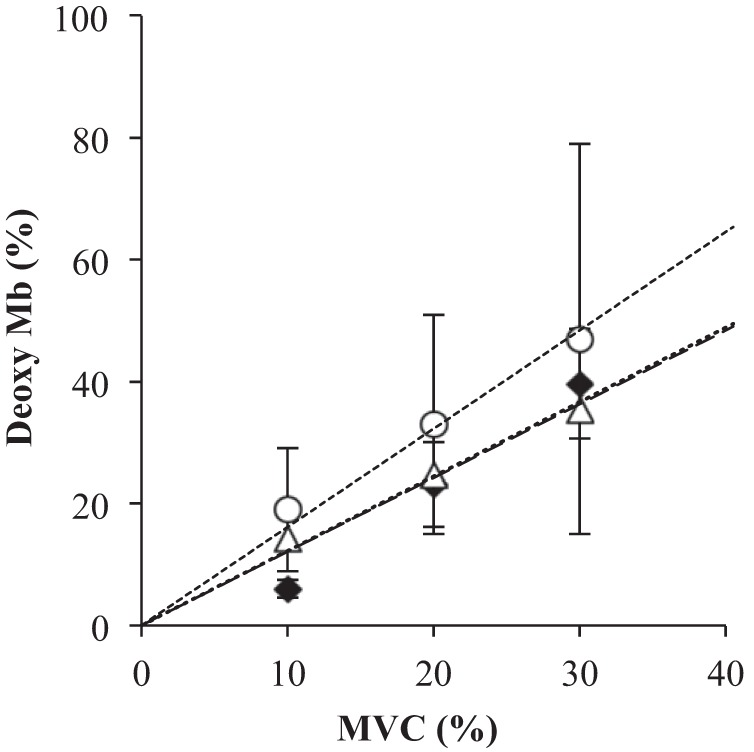

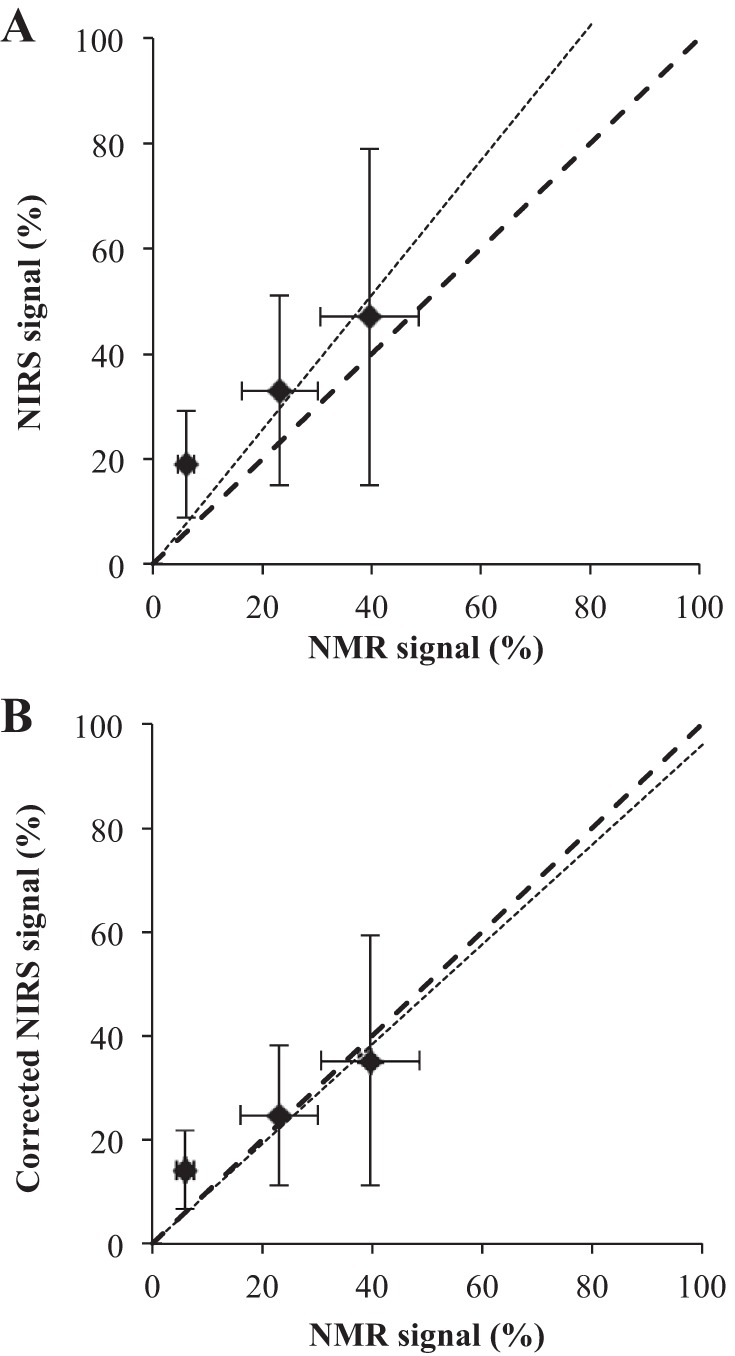

A comparative analysis of deoxyMb derived from the NMR data and the uncorrected NIRS data with contributions from both DMb and DHb indicates a similar trend with respect to %MVC (Fig. 7). Because the NMR analysis shows that DHb can contribute at most 20% to the NIRS signal, the analysis has corrected the NIRS data with an upper bound estimate of the Hb contribution. The analysis yields the relationship between DMb vs. %MVC as follows: uncorrected NIRS, y = 1.61x (r2 = 0.99); corrected NIRS, y = 1.21x (r2 = 0.99), and NMR, y = 1.22x (r2 = 0.95). Uncorrected NIRS data yield ∼1.3 times higher values than the NMR data. Using the corrected NIRS, however, the NIRS and NMR curves now match.

Fig. 7.

A plot of DMb vs. %MVC: the relationship between %MVC and DMb based on the NMR, DMb based on the uncorrected NIRS signal, and DMb based on the corrected NIRS signal, which assumes an upper estimate of a 20% DHb contribution. The analysis yields the following linear regression results: NMR, y = 1.22x, r2 = 0.95 (◆); uncorrected NIRS, y = 1.61x, r2 = 0.99 (○); and corrected NIRS, y = 1.21x, r2 = 0.99 (△). y = DMb, x = %MVC.

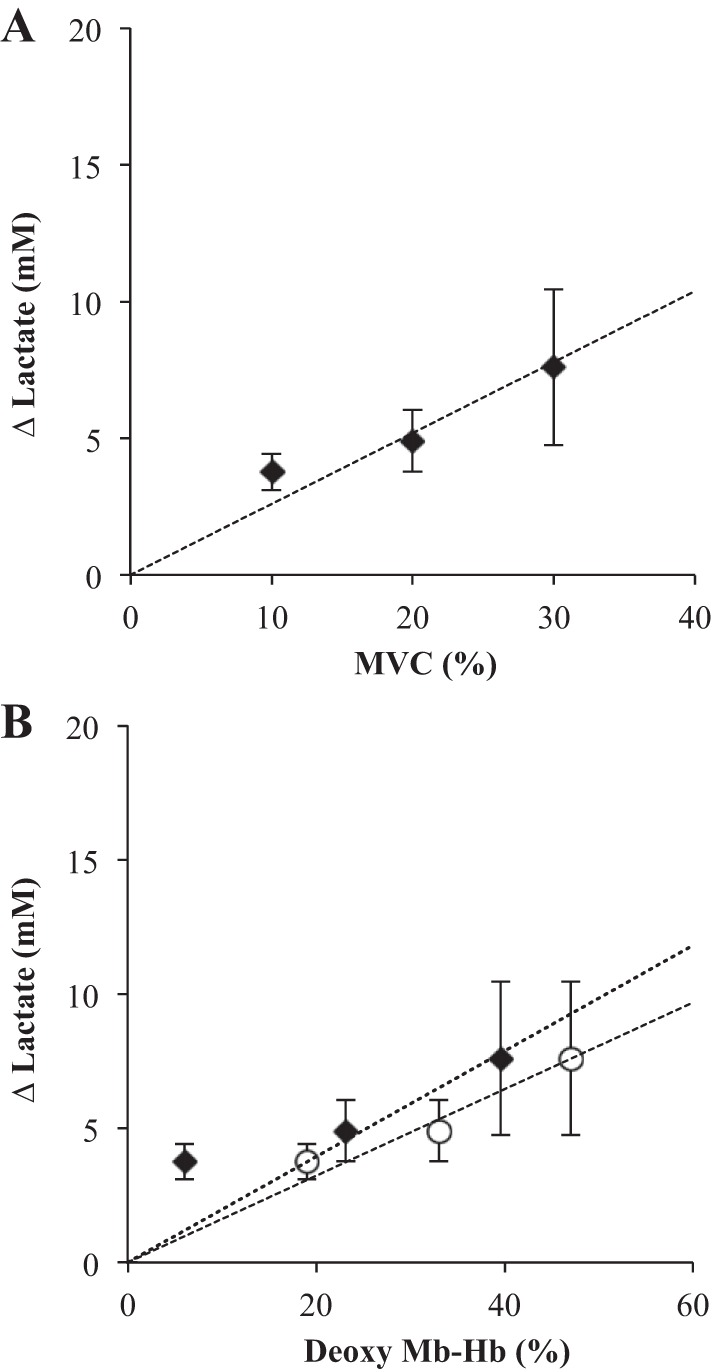

The pH values obtained from the 31P spectra lead to an estimate of lactate (Lac) (Table 2). Relative to the resting Lac level, Lac shows a linear rise with %MVC. A linear regression of ΔLac vs. %MVC yields y = 0.26x (r2 = 0.95), where y = ΔLac and x = %MVC (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

A: a plot of the lactate change relative to its resting state concentration (ΔLac) vs. %MVC: Linear regression of ΔLac vs. %MVC yields y = 0.26x, r2 = 0.95. B: a plot of the lactate change relative to its resting state concentration (ΔLac) vs. Deoxy Mb-Hb: Linear regression of ΔLac and Deoxy Mb-Hb based on the uncorrected NIRS signal yields y = 0.16x, r2 = 0.97 (○). The regression of ΔLac and DMb based on the NMR signal shows y = 0.20x, r2 = 0.77 (◆). Excluding the first Mb point, the line fit yields y = 0.20x, r2 = 0.99.

ΔLac also rises with increasing DMb and DMb + DHb derived from NMR and NIRS, respectively (Fig. 8B). The linear regression based on the NMR data yields y = 0.20x (r2 = 0.77). ΔLac should not change from its resting value when O2 fully saturates Mb. Without including the first DMb point, which contains a significant uncertainty, and assuming a y-intercept of 0, the regression improves sharply but continues to yield y = 0.20x (r2 = 0.99). The linear regression of ΔLac vs. DMb + DHb based on the NIRS data yields y = 0.16 (r2 = 0.97).

Figure 9 correlates the NIRS (DHb + DMb) and NMR (DMb) signals. A perfect correlation will have points coincident with the 1:1 identity line and fit the equation y = x, where y = NIRS signal and x = NMR signal. Uncorrected NIRS signal yields a higher estimate for DMb with a line y = 1.28x, r2 = 0.87. Subtracting the upper bound estimate of 20% contribution from DHb yields y = 0.96x, r2 = 0.87.

Fig. 9.

A plot correlating NIRS and NMR signals. A: uncorrected NIRS, y = 1.28x, r2 = 0.87. B: corrected NIRS, y = 0.96x, r2 = 0.87. A perfect match would yield the ideal line of y = x. y = NIRS signal, x = NMR signal.

DISCUSSION

NIRS.

In contrast to visible light, near-infrared radiation (NIR) has a deeper penetration depth. With a typical source-detector separation of 3 cm, NIR radiation from 750 to 1,400 nm can penetrate a banana-shaped volume centered ~1.5 cm below the surface (71, 76, 87, 92). A larger spacing between the source and detector will allow sampling signals from a deeper volume. However, the signals will have a lower intensity.

Both DHb and DMb display overlapping signals at 760 nm. MbO2 and HbO2 also exhibit a broad overlapping signals from 800 to 900 nm. For the measurement of MbO2 and HbO2, many NIRS instruments use as a reference the 850-nm signal in the flat region of the DHb and DMb spectra, which lies outside the lipid interference centered at 940 nm and the intense water signal at 1,000 nm (18). Given the Mb and Hb signals and the respective in vitro dissociation constants (Kd), an analysis can derive an estimate of the tissue Po2 (22, 34, 35, 48). The noninvasive and convenient approach has established NIRS as a standard methodology to investigate tissue oxygenation in different human organs in vivo and under different physiological conditions, such as cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, or Becker muscular dystrophy (1, 28, 33, 70, 72, 74).

For brain studies, only Hb and cytochromes (Cyt) contribute to the NIRS signal, since brain has no Mb. Measurements at two (or more) wavelengths help differentiate the relative contributions (53, 78). Because muscle has a significant amount of Mb, the NIRS method must deconvolute the Mb contribution.

Hb as the predominant signal source.

Many researchers have ascribed Hb as the only significant source of the NIRS signal based on comparative analyses of the NIRS signal with and without blood in an isolated perfused rat hindlimb model, on chemical oxidation of tissue Mb, and on inferences from NMR data (27, 85).

Seiyama et al. (85) substituted perflurocarbon (Fluosol-43) for blood to decrease the hematocrit from the normal 40% to 1.4%. Upon switching the buffer gas with 95% O2 to a 95% N2 in the Fluosol-enriched vasculature, they created a purported anoxia state within “a short period of time” and noted the DHb + DMb NIRS signal intensity decreased by 90%. Given the disappearance of 90% of the NIRS signal with the blood substitute, Seiyama et al. (85) concluded that Mb can contribute only 10% to the NIRS signal.

Because the report did not contain any measurements to verify anoxia, to assess blood flow, and to monitor basic physiology functions, residual concerns have emerged. Moreover, the experiments did not account for the adverse effects of perflurocarbon on the vasculature (60, 61). These adverse physiological effects would significantly alter the interpretation. In contrast to the report of Seiyama et al. (85), recent experiments using a buffer-perfused hindlimb model have detected a robust NIRS signal and have attributed over 50% of the NIRS signal to Mb (64).

Wilson et al. (97) infused ethyl peroxide in an isolated perfused canine gracilis muscle to oxidize the heme iron from Fe2+- to Fe3+-Mb, often termed metMb. Because metMb cannot bind O2, it cannot undergo a transition between the oxygenated and deoxygenated state. If Mb contributes significantly to the NIRS signal, then Mb-inactivated muscle should exhibit a decreased signal response during exercise. Such signal decrease would reflect the fractional Mb contribution to the NIRS signal. But Wilson et al. (97) detected no difference in the NIRS response and concluded that Mb did not contribute to the NIRS signal.

Whether ethyl peroxide actually oxidizes Mb in vivo poses a major concern, since Wilson et al. never verified or quantified the extent of Mb oxidation in vivo. The researchers only presumed that the peroxide reactivity (peroxide:Mb ~ 1:1) observed in vitro should also oxidize the heme from Fe2+ to Fe3+ in vivo. To the contrary, actual measurements of Mb oxidation in tissue reveal a recalcitrant metMb formation. Even though sodium nitrite (NaNO2) oxidizes Mb readily in vitro at NO2-to-Mb ratio of 1:1, oxidizing Mb in perfused myocardium requires at least a 40:1 molar ratio (21). The cell resists Mb oxidation and most likely uses its robust Mb reductase system to convert any Fe3+-Mb back to Fe2+Mb. The introduction of ethyl peroxide at a peroxide-to-Mb ratio of 1:1 might not have oxidized any Mb in tissue. As a result, control vs. Mb oxidized muscle would show no difference in the signal response, as observed.

Some studies have used the correlation between NIRS and venous O2 measurement to implicate the Hb origin of the NIRS signal (27, 97). These studies, however, do not report on the production of DMb. In fact, 1H NMR detects no DMb signal in some studies, unless the exercise intensity exceeds 80% of peak intensity (62). Below 80% peak intensity, no DMb signal appears. From 80% to 100% peak intensity, the DMb signal intensity increases sharply, which indicates that Po2 continues to drop markedly and does not reach any plateau. Because NMR detects no DMb signal at < 80% peak intensity, while the NIRS can observe an increasing DHb + DMb signal, Mancini et al. (62) concluded that NIRS measured predominantly the Hb signal. However, the present study and other literature reports show a detectable DMb signal ramping up from low-exercise intensity, well below 80%, to peak maximum intensity (69). The contrasting results might arise simply from low NMR detection sensitivity, which would fail to detect DMb signal at low exercise intensities and report an errant induction delay in Mb desaturation. Such a viewpoint can potentially reconcile the discrepant NMR observations and remove the NMR basis for imposing a predominant Hb origin to the NIRS signal.

Mb as the actual signal source.

1H NMR has observed that Mb can rapidly release its O2 store during contraction, since it can detect the His-F8 NδH signal from the DMb (69, 91). Indeed, as soon as contraction starts, NMR detects a DMb signal from human leg muscle (19). No delay intervenes. Mb releases immediately its O2 store upon the sudden surge in energy demand. In fact, NMR analysis indicates that in human leg muscle Mb desaturates immediately at the onset of contraction with a t1/2 ~ 24 s (19). NIRS experiments with buffer-perfused rat hindlimb also detect no significant delay in Mb desaturation and have determined the kinetics with a t1/2 ~ 45 s (88). In the present study, NIRS reveals similar Mb desaturation kinetics with a t1/2 ~ 27 s at 30% MVC.

During ischemia, the 1H NMR spectra show clearly a DMb appearing at 78 ppm. Another peak assigned to DHb appears at 73 ppm (91). The DHb signal represents no more than 0.2 of the total Mb and Hb signal. In contrast, during exercise, only the DMb peak appears.

The analysis has assigned the bumps upfield and downfield of the DMb peak observed at 30% MVC to noise, since these peaks do have maxima at chemical shift positions corresponding to any assignable peak in the spectral window, exhibit very narrow peaks whose linewidths match the window function broadening, do not show the intrinsic, characteristic broad lines arising from a paramagnetically shortened T1 and T2, exhibit approximately the same intensity as baseline noise, and do not appear consistently in every spectrum.

The results agree perfectly with previously published NMR and NIRS experimental observation on exercising leg muscle. In the leg spectra collected with a parallel NMR and NIRS experimental design, DHb signal appears only during ischemia and comprises <10% of the overall DMb + DHb signal (91). No DHb signal appears during exercise. With the improved signal to noise from gastrocnemius muscle, both NMR and NIRS signals display a similar desaturation kinetics during exercise, recovery, ischemia, and reperfusion (50, 91).

Under all exercise conditions, NMR cannot detect any DHb signal. Even though some researchers have asserted that NMR cannot detect DHb in erythrocytes, many literature reports have presented convincing evidence to show that Hb in erythrocytes has sufficient mobility to yield a detectable NMR signal (15, 31, 32, 56, 59, 84, 94). The DHb signal detected during ischemia confirms its NMR visibility. Moreover, during exercise, the pulsatile reflow of HbO2 into the muscle bed during the relaxation phase of each contraction cycle would diminish the averaged DHb signal. No HbO2 reflow occurs during ischemia.

With simultaneous NMR and NIRS measurements, the present study confirms that MbO2 releases within seconds its O2 at the start of contraction to reach a new steady-state level, that the O2 level falls progressively with increasing %MVC, and that the kinetics of MbO2 desaturation observed by NMR and by NIRS match. Mb contributes predominantly to the NIRS signal from muscle, especially during contraction. Hb does not contribute significantly.

Models of the relative Mb vs. Hb contribution.

Computer models and spectral transformation methods have also challenged a predominant Hb contribution to the NIRS signal. Even though the NIRS signals overlap, Mb and Hb do exhibit slight spectral differences. A second derivative transformation reveals spectral differences in vitro, which lead to a basis for a wavelength shift analysis that can distinguish Mb from Hb in vivo (63). With the second derivative analysis, Hb contributes only 21% of the NIRS signal arising from the human first dorsal interosseous muscle.

Davis and Barstow (28) have also modeled the Mb and Hb contribution to the NIRS signal in human muscle. Their model shows that Mb can contribute 85–95% of the light-absorbing potential in resting muscle. From rest to peak exercise, Mb contributes ∼70% of the changes in NIRS signal (28). Nioka et al. (73) have also examined the relative contribution of Hb and Mb. They conclude that Mb contributes ~50% to the NIRS signal. The model of Hoofd et al. (44) model also estimates ~50% Mb contribution.

In contrast to the orthodox perception, computer models and spectral transformation methods also support the notion that Mb contributes significantly to the NIRS signal.

Impact of assigning NIRS to Hb vs. Mb.

Because many NIRS researchers have ascribed Hb as the predominant contributor to the NIRS signal, studies have often interpreted the overall change in the NIRS signal as a reflection of blood volume change and capillary blood flow adjustment. Since the Hb concentration in erythrocyte does not change, any increase or decrease of the integrated NIRS signal of HbO2 and DHb must correlate with blood volume and provides a basis to estimate of O2 extraction and O2 consumption (V̇o2) (26, 29, 30). Such a dominant Hb contribution from the start of contraction supports implicitly the idea that the O2 supply or the O2 gradient created by the distance from the capillary to the cell can adjust rapidly to accommodate the surge in V̇o2 (6, 52, 65). Current reviews continue to discuss the prevailing ideas about NIRS signal quantification, limitations, and biomedical applications based on Hb as the major contributor to the NIRS signal (22, 35). However, if Hb does not contribute significantly to the NIRS signal during muscle contraction, then the blood volume interpretation appears tenuous. Instead a window into changes in the intracellular O2 would cast different perspectives on the dynamic interaction between the vascular and the cellular O2.

Assigning the NIRS to predominantly DMb opens a vista into the relationship between intracellular O2 and metabolism, as muscle transitions from rest to exercise. Both the NMR and NIRS data show rapid Mb desaturation at the start of contraction. With better time resolution than NMR, NIRS defines better the O2 kinetics in finger flexor muscles. Metabolism appears to match the changing O2 level. However, the low time resolution of the 31P NMR measurements, relative to the NIRS measurements, precludes presently a confident analysis of any tight correlation. Future experiments are needed to assess how tightly PCr and O2 kinetics correlate and cast unique insight into the dynamic change in metabolic regulation at the onset of muscle contraction.

Limitation in absolute quantification of tissue oxygenation.

Determining tissue oxygenation requires defining the totally ischemic or anoxic state and using the corresponding signal to normalize all signals in either the NMR or NIRS methodology. Most experiments have relied on a standard protocol to occlude blood flow to the muscle bed by increasing rapidly the pressure cuff around an arm or leg to create an experimentally defined signal corresponding to an assumed 100% deoxygenated state. When the signal during ischemia approaches a plateau, after ~6 min of blood occlusion, most experimenters have considered this signal to reflect the anoxic state and have used it to normalize the other signals.

However, reaching a signal intensity plateau does not always indicate a fully deoxygenated state. In fact, it just represents a new steady state. Ischemia applied for 6 min might still not deplete all the endogenous oxygen stores, given the low oxygen consumption rate of resting muscle (8). Moreover, pressure cuffing even at pressures well above the systolic pressure might still not stop blood flow in deep vessels, especially for large muscle groups (e.g., quadriceps). Given the low oxygen consumption of resting muscle, potential residual blood flow, and incomplete depletion of all endogenous O2, muscle cells might not have reached any O2 threshold, which would trigger creatine kinase or glycolysis to generate any compensating ATP.

In the present study, defining the signal at the end of 6 min as an operational ischemia condition will not alter the outcome of the comparative or relative analysis of NIRS vs. NMR results. For absolute quantitation of tissue oxygenation, however, the experimental design must include other criteria to establish the presence of a 100% deoxygenated state.

In NMR, using the Val E11 signal of MbO2 avoids normalizing to an anoxic state signal, since its intensity reaches a maximum under well-oxygenated conditions and decreases as O2 level declines (55). NIRS cannot use the corresponding MbO2 or HbO2 signal in the same manner, since the broad, overlapping NIRS signals of MbO2 and HbO2 spanning from 700 to 1,000 nm do not display any sharp peak maxima (18). Unfortunately, at present, detecting the Val E11 signal in low magnetic field, where most skeletal muscle experiments occur, still poses a technical challenge for NMR researchers to overcome.

Aerobic lactate formation.

From a conventional vantage point, as intracellular O2 declines substrate phosphorylation should begin to rise and compensate for the ATP loss from oxidative phosphorylation. O2 insufficiency should breach a critical point, before substrate phosphorylation begins to compensate for the missing oxidative ATP generation. Under resting conditions, the vascular O2 supplies the myocytes with sufficient O2 to saturate more than 90% of the MbO2. Given the Mb P50 of ~2 mmHg at 35°C, the resting cellular Po2 stands well above 18 mmHg. Many studies, however, have estimated a Po2 of ~10 mmHg for the resting state.

At the onset of contraction, no apparent delay intervenes the immediate desaturation of MbO2 (19). With increasing exercise intensity, which corresponds to increasing oxygen consumption (V̇o2), O2 level does not increase at all. Instead it declines progressively. Unless the resting myocyte stands at the brink of hypoxia, the initial decrease in O2 should not correspond to any hypoxia onset. In fact, perfused heart experiments show that O2 level must reach a critical Po2 around the P50 of Mb to trigger reactions to compensate for the oxidative ATP loss. At the critical point, V̇o2 and PCr begin to fall. Contractile function decreases. Lactate formation also increases but has a much higher critical Po2. In essence, lactate formation begins to increase at Po2 of 4.4 mmHg, whereas PCr and V̇o2 respond at ~2 mmHg. ATP has a critical Po2 of 0.8 mmHg (54).

In the present study, lactate level, as derived from the pH change reflected in the 31P spectra, also begins to rise when the contraction reaches only 10% MVC. At 10% MVC, both 1H NMR and NIRS estimate a Po2 ranging from 10 to 46 mmHg, well above any anticipated critical Po2. The interleaved 1H/31P NMR signal acquisitions combined with simultaneous NIRS measurement record in real time change in O2 and lactate and reveal that lactate formation starts to rise even under quite aerobic conditions. As such, O2 insufficiency alone cannot trigger the rise in lactate formation.

Indeed, studies correlating the 1H NMR signal of DMb with lactate efflux observed from femoral catheters have also shown a linear increase in lactate with MVC, starting at 25% MVC. However, at all MVC steps (25%, 50%, 75%, and 90%), the reported DMb signal intensity remains constant at a plateau value of 50% of maximum DMb (79, 80). DMb displays no progressive ramp-up from 25% to 50% MVC, which stands in contrast to the present and previous studies (69, 88). Even at 25% MVC, MbO2 has desaturated to 50% level, which represents a critical Po2 level (17, 54). The present study demonstrates that lactate formation begins at cellular Po2 well above the P50. O2 insufficiency does not appear to constitute a necessary and sufficient condition for an increased formation of lactate (25).

Brooks et al. have also observed muscle producing lactate even in the presence of abundant O2. To rationalize aerobic lactate formation, they have proposed a lactate shuttle from glycolytic white fibers to oxidative red fibers to redistribute lactate as an energy source. With the detection of a mitochondrial monocarboxylate lactate transporter and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), the idea has expanded to include a potential shuttle from the cytosol to the mitochondria (11–13, 24, 38, 41, 42).

Cellular role for aerobic lactate.

A biochemical mechanism underlying lactate production under aerobic conditions has recently emerged. It is predicated on triggered 31P studies that show rapid and significant millisecond consumption of PCr during a muscle contraction (20). Because lactate can also serve as a precursor for oxidative metabolism, its accumulation under aerobic conditions could serve as a buffer to balance any transient mismatch between oxidative phosphorylation and energy demand. During glycogenolysis in the contraction phase, lactate accumulates. During the much longer relaxation phase lactate can serve as a precursor for acetyl CoA formation and oxidative ATP generation (23, 86).

The limited glycogen supply in the cell, however, demands a dynamic replenishment during the relaxation phase. Otherwise, the cell would rapidly expend all its glycogen store. In the glycogen shunt, glycogen supplies the ATP millisecond needs and serves as a temporal energy buffer (20). Even though glyconeogenesis occurs primarily in liver, studies have already shown that lactate can also serve as a carbon precursor for glyconeogenesis in muscle (9, 49, 66, 67). The relative contribution of glucose and lactate to glycogen replenishment in exercising muscle remains an open question.

However, both the intracellular lactate shuttle and glycogen shunt models require muscle to mobilize rapidly lactate into the acetyl CoA pool. Indeed, recent dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) studies confirm that muscle can mobilize lactate rapidly and that pyruvate dehydrogenase can compete with lactate dehydrogenase to divert lactate into the acetyl CoA pool (75). The DNP experimental observations support a critical tenability of the glycogen shunt, lactate shuttle, and lactate as an energy buffer hypotheses.

Limitation in determining lactate from pH change.

Determining the change in the lactate level based on the H+ released has limitations. Many physiologists have railed against the lactic acidosis misnomer, because it implies the deprotonation of lactic acid leads to 1:1 H+ release. At physiological pH, both pyruvate and lactate form as the deprotonated species. Lactate deprotonation cannot lead to the observed H+ release. Terming the acidosis observed in contracting muscle as metabolic acidosis helps to properly frame the question about the source of the H+ formed in glycolysis.

However, physiologists do not agree on the H+ source or the stoichiometry leading to the metabolic acidosis. Investigators have pointed out the H+ release in the lactate dehydrogenase reaction cannot accumulate, since the glyceraldehye 3-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction in the glycolysis pathway consumes an equivalent amount of H+ (37, 43). Even though many have agreed that ATP hydrolysis contributes to the H+ release, the actual H+:lactate stoichiometry, which relates the contribution of glycolysis to the observed metabolic acidosis, remains a controversial and heated topic of debate (81).

The present study has used the semiempirical equation developed and tested by Hsu and Dawson (46), which relates H+ released to lactate formed by considering three key H+ buffering reactions involving phosphate, carnosine, and histidine. Based on the pH shift during exercise, the analysis suggests that lactate formation has increased at the apparently high O2 level, well above the P50 of Mb and above any anticipated hypoxia threshold. Quantitative analysis of the relationship between O2 and lactate formation awaits future experiments, which must measure lactate directly to corroborate the analysis in the present study.

Scaling and calibrating the NIRS signal.

Although the present experiment has interrogated a small muscle group, flexor digitorum superficialis, the results should apply to large muscle groups. That outlook is predicated on the excellent agreement between the results from the present study and results from gastrocnemius muscle during plantar flexion exercise (91). In the leg study, DHb contributes <10% to the overall NIRS signal of DMb + DHb. During all exercise protocols, NMR cannot detect any DHb signal. Nevertheless, the NIRS and NMR kinetics profile of the DMb match. Both simultaneous and parallel NIRS and NMR measurements reach the same conclusion. The DHb NIRS signal in gastrocnemius muscle also does not predominate.

The amount of DHb contribution to the NIRS signal, although small, will vary in different muscle groups and with different exercise protocols. Correcting the observed NIRS signal with an upper-bound estimate of DHb contribution of 20% reconciles almost perfectly the NMR and NMR measurements. The results could suggest DHb still has a slight contribution to the NIRS and NMR during exercise. Alternatively, they can also indicate the NIRS and NMR sampling volumes do not overlap, and changes in tissue characteristics during exercise have different measurement effects. These effects would lead to measurement discrepancies. The current experimental data cannot determine how well the sampling volumes match or the impact of changes in tissue characteristics. Future experiments must clarify.

Nevertheless, experimental protocols starting with an NMR calibration of the DMb + DHb observed NIRS signal would improve the interpretation of the NIRS measurement and avoid potential errors.

Dynamic change in bioenergetics.

At the initiation of muscle contraction, the NIRS signals of DMb + DHb rise immediately to a steady state with a t1/2 = 24–42 s, consistent with the NMR observation of MbO2 desaturating immediately with a t1/2 ~ 27 s (19). With increasing contraction intensity, both the NMR and NIRS signals show MbO2 desaturating more. At 30% MVC, the fraction of deoxyMb reaches 40–57%. Since muscle oxygen consumption (V̇o2) should rise proportionately with MVC, the results indicate that as V̇o2 increases with contraction intensity, the cellular O2 level falls linearly.

The declining O2 with rising V̇o2 seems somewhat incongruous with the notion that O2 supply determines V̇o2. Respiration rate, however, depends upon the tight coupling of a multistep process involving ATP formation, electron transport, proton-motive force, and V̇o2. The declining O2 with a rising respiration rate would militate against the O2 supply as the rate-limiting step but requires cytochrome oxidase to have a much lower Km than the Mb P50. Indeed cytochrome oxidase has a Km of 0.1 mmHg in reducing O2 to H2O (96).

So, the declining cellular Po2 with exercise increases the O2 gradient, which enhances the O2 flux into the cell to meet the elevated V̇o2. At the same time, cellular O2 level must remain above the cytochrome oxidase Km, so that other components of respiration can still enhance its rate. Indeed, cytochrome oxidase experiments impute proton translocation and not O2 binding as the rate-limiting step (10, 36).

Moreover, the cellular Po2 does not by itself determine the metabolic response. Starting at 10% MVC, PCr declines. It declines further at 20% and 30% MVC, consistent with previous observations (69). Intracellular acidosis also increases progressively, whereas ATP level remains constant. During ischemia the cellular O2 level also decreases. However, even after 6 min of ischemia, as MbO2 approaches an experimentally determined full desaturation well below the O2 level observed at 30% MVC, neither PCr/(PCr + Pi) nor pH change significantly. At the same cellular Po2, exercise and ischemia elicit very different metabolic responses. During exercise, lactate formation rises, PCr drops, and pH declines. During ischemia, lactate formation, PCr, and pH exhibit no significant change. The contrast in metabolic response at the same Po2 in ischemia and during exercise underscores the contrasting perspectives in analyzing the steady-state ATP vs. ATP turnover. Steady-state ATP may show no change in ischemia vs. during exercise. Yet, the ATP turnover differs dramatically. ATP consumption, tightly linked to V̇o2, during exercise far exceeds the consumption during ischemia. Indeed, ATP utilization, rather than O2 supply alone or steady-state ATP level, drives the relationship linking falling O2, shifting metabolism, and rising V̇o2 (19).

PCr recovery and oxidative capacity.

The interplay of different kinetics casts also perspectives into the role of O2 in regulating the PCr recovery rate, which serves as an index of oxidative phosphorylation capacity. How the returning O2 controls oxidative ATP regeneration, as reflected in the PCr recovery, continues to pose a pressing physiological question.

During postischemic reperfusion, NIRS indicates that O2 returns to the cell with a t1/2 of 0.2 min (~12 s). The NMR shows a somewhat slower t1/2 of 0.9 min (54 s). Because NIRS measurement has a time resolution of 0.1 s, whereas NMR has a 60-s time resolution, the contrasting time constants might not have any physiological significance. Nevertheless, it highlights the potential of measuring the hyperemia during postischemia, if the analysis has confidence in interpreting a faster NIRS time constant from the rapid reflow of oxygenated blood during hyperemia. A proper analysis, however, must determine the contribution from altered tissue characteristics between ischemia and postischemia, since sudden changes in fluid volume affect the photon migration pathway, which in turn will modulate the NIRS signal intensity. In fact, given better signal to noise of the DMb and DHb signal after ischemia, NMR can also discriminate the kinetics of blood reflow and restoration of oxidative metabolism.

In postischemic reperfusion, the returning O2 does not impact any PCr recovery, since during the 6-min ischemia, PCr level has remained constant. During exercise recovery, O2 recovery rate also does not appear to limit PCr recovery rate, which reflects the restoration of the oxidative phosphorylation. NIRS shows O2 recovering with a t1/2 of 0.4 min (~24s). PCr recovers after 30% MVC with a t1/2 of 0.27 min (~16 s). Within the measurement errors, O2 and PCr show matching recovery kinetics. The returning intracellular supply of O2 recovery correlates with ATP recovery and the oxidative phosphorylation restoration (51, 68).

Both intracellular O2 and PCr also decrease rapidly at the onset of contraction. The data do not reveal any metabolic inertia consistent with the discrepancy between the observed delay between blood flow adjustment and O2 extraction (arteriovenous difference) (39, 40). In the metabolic inertia hypothesis, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity cannot accommodate the surge in energy demand at the onset of muscle contraction. PDH cannot switch rapidly into its activated form (PDHα) (5, 45). In support of the hypothesis, introducing dichloroacetate (DCA), which can increase PDHα level 4 times over its control level, does not decrease the start of muscle O2 extraction (4).

However, 1H NMR measurements of intracellular myoglobin show an immediate desaturation at the onset of contraction (19). Based on the Mb kinetics, the intracellular V̇o2 shows no sign of delay. In fact, in recent 13C dynamic nuclear polarization experiments, the relative PDHα (as reflected in the flux from Lac→HCO3 vs. Lac→Pyr) shows that DCA can trigger an immediate rise in PDHα, 37 times above the control level (75). PDH does not have any limitation in switching rapidly to its activated form to enhance acetyl CoA formation. The extent of metabolic inertia in exercising muscle remains unclear.

Conclusions.

Combined NIRS and interleaved 1H and 31P NMR measurements have determined a predominant Mb contribution to the NIRS signal from muscle. Both the NMR and NIRS data point to a progressive decline of the intracellular O2 level as the exercise intensity increases. Despite the modest decrease in O2 level, well above the critical Po2 (P50 of Mb), lactate formation begins to increase. The rapid decline in the O2 supply and restoration of O2 during exercise and recovery indicate O2 alone does not limit metabolism.

Perspectives and Significance

At the initiation of muscle contraction, energy demand surges. V̇o2 rises and metabolism shifts to meet the new energy demand. The available O2 and its impact on altered metabolic regulation stand as central concerns in muscle and in respiratory physiology. To understand the impact of O2 in exercising muscle, many studies have relied on near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure noninvasively the tissue O2. Because the NIRS methodology is predicated on detecting the overlapping myoglobin (Mb) and hemoglobin (Hb) signals, the relative contribution of Mb and Hb to the NIRS signal has posed a longstanding question. Even though the current paradigm embraces Hb as the primary source, the present study shows that the NIRS signal in muscle originates predominantly from Mb and not from Hb. 1H NMR can detect the DMb signal in exercising and ischemic muscle. However, it can only detect the DHb signal in ischemic muscle, which comprises 20% of the total Mb and Hb signal.

Using both 1H NMR and NIRS techniques to map tissue oxygenation during muscle contraction yields unique physiology insights: Mb desaturates rapidly and reaches within seconds a new steady state, tissue oxygenation decreases with increasing exercise intensity, at the same intracellular Po2 the metabolic response during exercise differs dramatically to the response during ischemia, and lactate formation increases at an O2 level that does not appear to breach any hypoxia threshold. Given the different advantages of the NIRS and NMR, a combined methodological approach promises to clarify the metabolic regulation of muscle as it transitions from a resting to an active contracting state.

GRANTS

We gratefully acknowledge funding support from France-Berkeley-Fund (201013861), Burroughs Wellcome Travel Grant (1012774), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS UMR 7339), and the France Life Imaging Network (ANR-11-INBS-0006).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.B., B.C., and T.J. conceived and designed research; D.B., B.C., and T.J. performed experiments; D.B., B.C., and T.J. analyzed data; D.B., B.C., and T.J. interpreted results of experiments; D.B., B.C., and T.J. prepared figures; D.B., B.C., and T.J. drafted manuscript; D.B., B.C., and T.J. edited and revised manuscript; D.B., B.C., and T.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge C. Vilmen Centre de Résonance Magnétique Biologique et Médicale (CRMBM), Y. Le Fur (CRMBM), and C. Wary (Bruker Biospin) for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allart E, Olivier N, Hovart H, Thevenon A, Tiffreau V. Evaluation of muscle oxygenation by near-infrared spectroscopy in patients with Becker muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 22: 720–727, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold DL, Matthews PM, Radda GK. Metabolic recovery after exercise and the assessment of mitochondrial function in vivo in human skeletal muscle by means of 31P NMR. Magn Reson Med 1: 307–315, 1984. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baligand C, Jouvion G, Schakman O, Gilson H, Wary C, Thissen JP, Carlier PG. Multiparametric functional nuclear magnetic resonance imaging shows alterations associated with plasmid electrotransfer in mouse skeletal muscle. J Gene Med 14: 598–608, 2012. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangsbo J, Gibala MJ, Howarth KR, Krustrup P. Tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates accumulate at the onset of intense exercise in man but are not essential for the increase in muscle oxygen uptake. Pflügers Arch 452: 737–743, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsbo J, Gibala MJ, Krustrup P, González-Alonso J, Saltin B. Enhanced pyruvate dehydrogenase activity does not affect muscle O2 uptake at onset of intense exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R273–R280, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bank W, Chance B. An oxidative defect in metabolic myopathies: diagnosis by noninvasive tissue oximetry. Ann Neurol 36: 830–837, 1994. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendahan D, Confort-Gouny S, Kozak-Reiss G, Cozzone PJ. Heterogeneity of metabolic response to muscular exercise in humans. New criteria of invariance defined by in vivo phosphorus-31 NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett 272: 155–158, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80472-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blei ML, Conley KE, Kushmerick MJ. Separate measures of ATP utilization and recovery in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 465: 203–222, 1993. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonen A, McDermott JC, Tan MH. Glycogenesis and glyconeogenesis in skeletal muscle: effects of pH and hormones. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 258: E693–E700, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brändén M, Sigurdson H, Namslauer A, Gennis RB, Adelroth P, Brzezinski P. On the role of the K-proton transfer pathway in cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5013–5018, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081088398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks GA. Cell-cell and intracellular lactate shuttles. J Physiol 587: 5591–5600, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks GA. Intra- and extra-cellular lactate shuttles. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32: 790–799, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks GA. Lactate production under fully aerobic conditions: the lactate shuttle during rest and exercise. Fed Proc 45: 2924–2929, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks GA. The lactate shuttle during exercise and recovery. Med Sci Sports Exerc 18: 360–368, 1986. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198606000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown FF, Campbell ID. Nuclear magnetic resonance of intact biological systems. N.m.r. studies of red cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 289: 395–406, 1980. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung Y. Oxygen reperfusion is limited in the postischemic hypertrophic myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2075–H2084, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00619.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung Y, Jue T. Critical oxygen and myoglobin function in myocardium. In: Current and Future Applications of Magnetic Resonance in Cardiovascular Medicine, edited by Higgins CB, Ingwall JS, Pohost GM. Armonk, NY: Futura, 1998, p. 511–528. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung Y, Jue T. Noninvasive NMR and NIRS measurement of vascular and intracellular oxygenation in vivo. In: Application of Near Infrared Spectroscopy in Biomedicine, edited by Jue T. Boston, MA: Springer, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6252-1_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung Y, Molé PA, Sailasuta N, Tran TK, Hurd R, Jue T. Control of respiration and bioenergetics during muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C730–C738, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00138.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung Y, Sharman R, Carlsen R, Unger SW, Larson D, Jue T. Metabolic fluctuation during a muscle contraction cycle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C846–C852, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung Y, Xu D, Jue T. Nitrite oxidation of myoglobin in perfused myocardium: implications for energy coupling in respiration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1166–H1173, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colier WN, Meeuwsen IB, Degens H, Oeseburg B. Determination of oxygen consumption in muscle during exercise using near infrared spectroscopy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 107: 151–155, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connett RJ, Gayeski TE, Honig CR. Energy sources in fully aerobic rest-work transitions: a new role for glycolysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 248: H922–H929, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connett RJ, Gayeski TE, Honig CR. Lactate accumulation in fully aerobic, working, dog gracilis muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 246: H120–H128, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connett RJ, Gayeski TE, Honig CR. Lactate efflux is unrelated to intracellular Po2 in a working red muscle in situ. J Appl Physiol (1985) 61: 402–408, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cope M, Delpy DT. System for long-term measurement of cerebral blood and tissue oxygenation on newborn infants by near infra-red transillumination. Med Biol Eng Comput 26: 289–294, 1988. doi: 10.1007/BF02447083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costes F, Barthélémy JC, Féasson L, Busso T, Geyssant A, Denis C. Comparison of muscle near-infrared spectroscopy and femoral blood gases during steady-state exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 80: 1345–1350, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis ML, Barstow TJ. Estimated contribution of hemoglobin and myoglobin to near infrared spectroscopy. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 186: 180–187, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Blasi RA, Cope M, Elwell C, Safoue F, Ferrari M. Noninvasive measurement of human forearm oxygen consumption by near infrared spectroscopy. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 67: 20–25, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00377698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Blasi RA, Ferrari M, Natali A, Conti G, Mega A, Gasparetto A. Noninvasive measurement of forearm blood flow and oxygen consumption by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 76: 1388–1393, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everhart CH, Gabriel DA, Johnson CS Jr. Tracer diffusion coefficients of oxyhemoglobin A and oxyhemoglobin S in blood cells as determined by pulsed field gradient NMR. Biophys Chem 16: 241–245, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(82)87006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Everhart CH, Johnson CS Jr. The determination of tracer diffusion coefficients for proteins by means of pulsed field gradient NMR with applications to hemoglobin. J Magn Reson 48: 466–474, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari M, Binzoni T, Quaresima V. Oxidative metabolism in muscle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352: 677–683, 1997. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrari M, Mottola L, Quaresima V. Principles, techniques, and limitations of near infrared spectroscopy. Can J Appl Physiol 29: 463–487, 2004. doi: 10.1139/h04-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrari M, Muthalib M, Quaresima V. The use of near-infrared spectroscopy in understanding skeletal muscle physiology: recent developments. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 369: 4577–4590, 2011. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gennis RB. How does cytochrome oxidase pump protons? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 12747–12749, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gevers W. Generation of protons by metabolic processes in heart cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 9: 867–874, 1977. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2828(77)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gladden LB. Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J Physiol 558: 5–30, 2004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grassi B. Regulation of oxygen consumption at exercise onset: is it really controversial? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 29: 134–138, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grassi B, Gladden LB, Stary CM, Wagner PD, Hogan MC. Peripheral O2 diffusion does not affect V̇o2 on-kinetics in isolated in situ canine muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 85: 1404–1412, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto T, Hussien R, Brooks GA. Colocalization of MCT1, CD147, and LDH in mitochondrial inner membrane of L6 muscle cells: evidence of a mitochondrial lactate oxidation complex. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1237–E1244, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00594.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashimoto T, Masuda S, Taguchi S, Brooks GA. Immunohistochemical analysis of MCT1, MCT2 and MCT4 expression in rat plantaris muscle. J Physiol 567: 121–129, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochachka PW, Mommsen TP. Protons and anaerobiosis. Science 219: 1391–1397, 1983. doi: 10.1126/science.6298937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoofd L, Colier W, Oeseburg B. A modeling investigation to the possible role of myoglobin in human muscle in near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurements. Adv Exp Med Biol 530: 637–643, 2003. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howlett RA, Heigenhauser GJ, Hultman E, Hollidge-Horvat MG, Spriet LL. Effects of dichloroacetate infusion on human skeletal muscle metabolism at the onset of exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 277: E18–E25, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu AC, Dawson MJ. Accuracy of 1H and 31P MRS analyses of lactate in skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med 44: 418–426, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jöbsis FF. Non-invasive, infra-red monitoring of cerebral O2 sufficiency, blood volume, HbO2-Hb shifts and bloodflow. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 64: 452–453, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jöbsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 198: 1264–1267, 1977. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson JL, Bagby GJ. Gluconeogenic pathway in liver and muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 64: 1591–1599, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jue T, Tran TK, Mole P, Chung Y, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Kreutzer U, Kuno S. Myoglobin and O2 consumption in exercising human gastrocnemius muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol 471: 289–294, 1999. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4717-4_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kemp GJ, Taylor DJ, Radda GK. Control of phosphocreatine resynthesis during recovery from exercise in human skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed 6: 66–72, 1993. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940060111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kindig CA, Richardson TE, Poole DC. Skeletal muscle capillary hemodynamics from rest to contractions: implications for oxygen transfer. J Appl Physiol (1985) 92: 2513–2520, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01222.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klungsøyr L, Støa KF. Spectrophotometric determination of hemoglobin oxygen saturation: the method of Drabkin & Schmidt as modified for its use in clinical routine analysis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 6: 270–276, 1954. doi: 10.3109/00365515409134863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kreutzer U, Jue T. Critical intracellular oxygen in the myocardium as determined with the 1H NMR signal of myoglobin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H1675–H1681, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreutzer U, Wang DS, Jue T. Observing the 1H NMR signal of the myoglobin Val-E11 in myocardium: an index of cellular oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 4731–4733, 1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuchel PW, Chapman BE. Translational diffusion of hemoglobin in human erythrocytes and hemolysates. J Magn Reson 94: 574–580, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Layec G, Bringard A, Le Fur Y, Vilmen C, Micallef JP, Perrey S, Cozzone PJ, Bendahan D. Reproducibility assessment of metabolic variables characterizing muscle energetics in vivo: A 31P-MRS study. Magn Reson Med 62: 840–854, 2009. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le Fur Y, Nicoli F, Guye M, Confort-Gouny S, Cozzone PJ, Kober F. Grid-free interactive and automated data processing for MR chemical shift imaging data. MAGMA 23: 23–30, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s10334-009-0186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.London RE, Gregg CT, Matwiyoff NA. Nuclear magnetic resonance of rotational mobility of mouse hemoglobin labeled with [2-13C]histidine. Science 188: 266–268, 1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1118727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowe KC. Fluosol: the first commercial injectable perfluorocarbon oxygen carrier. In: Blood Substitutes, edited by Winslow RS. San Diego, CA: Academic, 2006, p. 276–287. doi: 10.1016/B978-012759760-7/50034-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lowe KC. Perfluorinated blood substitutes and artificial oxygen carriers. Blood Rev 13: 171–184, 1999. doi: 10.1054/blre.1999.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mancini DM, Wilson JR, Bolinger L, Li H, Kendrick K, Chance B, Leigh JS. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurement of deoxymyoglobin during exercise in patients with heart failure. Demonstration of abnormal muscle metabolism despite adequate oxygenation. Circulation 90: 500–508, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marcinek DJ, Amara CE, Matz K, Conley KE, Schenkman KA. Wavelength shift analysis: a simple method to determine the contribution of hemoglobin and myoglobin to in vivo optical spectra. Appl Spectrosc 61: 665–669, 2007. doi: 10.1366/000370207781269819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Masuda K, Takakura H, Furuichi Y, Iwase S, Jue T. NIRS measurement of O2 dynamics in contracting blood and buffer perfused hindlimb muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol 662: 323–328, 2010. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1241-1_46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCully KK, Hamaoka T. Near-infrared spectroscopy: what can it tell us about oxygen saturation in skeletal muscle? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 28: 123–127, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McDermott JC, Bonen A. Glyconeogenic and oxidative lactate utilization in skeletal muscle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 70: 142–149, 1992. doi: 10.1139/y92-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McLane JA, Holloszy JO. Glycogen synthesis from lactate in the three types of skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 254: 6548–6553, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meyer RA. A linear model of muscle respiration explains monoexponential phosphocreatine changes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 254: C548–C553, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molé PA, Chung Y, Tran TK, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Jue T. Myoglobin desaturation with exercise intensity in human gastrocnemius muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R173–R180, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molinari F, Joy Martis R, Acharya UR, Meiburger KM, De Luca R, Petraroli G, Liboni W. Empirical mode decomposition analysis of near-infrared spectroscopy muscular signals to assess the effect of physical activity in type 2 diabetic patients. Comput Biol Med 59: 1–9, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mourant JR, Fuselier T, Boyer J, Johnson TM, Bigio IJ. Predictions and measurements of scattering and absorption over broad wavelength ranges in tissue phantoms. Appl Opt 36: 949–957, 1997. doi: 10.1364/AO.36.000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nielsen HB. Systematic review of near-infrared spectroscopy determined cerebral oxygenation during non-cardiac surgery. Front Physiol 5: 93, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nioka S, Wang DJ, Im J, Hamaoka T, Wang ZJ, Leigh JS, Chance B. Simulation of Mb/Hb in NIRS and oxygen gradient in the human and canine skeletal muscles using H-NMR and NIRS. Adv Exp Med Biol 578: 223–228, 2006. doi: 10.1007/0-387-29540-2_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]