Key Points

Question

Does the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination safely improve care when used in the emergency department (ED) evaluation of hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma?

Findings

In this trial of 925 hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma, randomization to the FAST vs standard trauma examination did not result in significant improvement in the rate of abdominal computed tomographic scans, time in the ED, hospital charges, or missed intra-abdominal injuries vs children randomized to standard trauma evaluation.

Meaning

The study findings do not support the routine use of FAST in the ED for hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma.

Abstract

Importance

The utility of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination in children is unknown.

Objective

To determine if the FAST examination during initial evaluation of injured children improves clinical care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical trial (April 2012-May 2015) that involved 975 hemodynamically stable children and adolescents younger than 18 years treated for blunt torso trauma at the University of California, Davis Medical Center, a level I trauma center.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to a standard trauma evaluation with the FAST examination by the treating ED physician or a standard trauma evaluation alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Coprimary outcomes were rate of abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scans in the ED, missed intra-abdominal injuries, ED length of stay, and hospital charges.

Results

Among the 925 patients who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 9.7 [5.3] years; 575 males [62%]), all completed the study. A total of 50 patients (5.4%, 95% CI, 4.0% to 7.1%) were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injuries, including 40 (80%; 95% CI, 66% to 90%) who had intraperitoneal fluid found on an abdominal CT scan, and 9 patients (0.97%; 95% CI, 0.44% to 1.8%) underwent laparotomy. The proportion of patients with abdominal CT scans was 241 of 460 (52.4%) in the FAST group and 254 of 465 (54.6%) in the standard care–only group (difference, −2.2%; 95% CI, −8.7% to 4.2%). One case of missed intra-abdominal injury occurred in a patient in the FAST group and none in the control group (difference, 0.2%; 95% CI, −0.6% to 1.2%). The mean ED length of stay was 6.03 hours in the FAST group and 6.07 hours in the standard care–only group (difference, −0.04 hours; 95% CI, −0.47 to 0.40 hours). Median hospital charges were $46 415 in the FAST group and $47 759 in the standard care–only group (difference, −$1180; 95% CI, −$6651 to $4291).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among hemodynamically stable children treated in an ED following blunt torso trauma, the use of FAST compared with standard care only did not improve clinical care, including use of resources; ED length of stay; missed intra-abdominal injuries; or hospital charges. These findings do not support the routine use of FAST in this setting.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01540318

This randomized clinical trial compares the effects of adding focused assessment sonography for trauma (FAST) examination to a standard trauma evaluation on missed diagnoses and health services outcomes for pediatric patients with blunt torso trauma.

Introduction

The focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination is used in the evaluation of injured patients, with the goal of identifying hemoperitoneum associated with intra-abdominal injuries. Most research regarding the FAST examination has involved injured adults. Advantages of the FAST examination compared with computed tomography (CT) include bedside availability during emergency department (ED) evaluation or resuscitation, rapid completion, ability for serial examinations, performance and interpretation by ED physicians, and lack of exposure to radiation. Although the sensitivity of the FAST examination for detecting hemoperitoneum in children is inferior to CT, its use may safely decrease abdominal CT in selected patients.

Evidence from randomized clinical trials involving adults indicates that incorporating the FAST examination during the initial evaluation resulted in decreased abdominal CT use, hospital lengths of stay (LOSs), complications, and hospital charges.

The FAST examination is not routinely used in the initial evaluation of injured children, perhaps reflecting the absence of randomized clinical trials involving children. A 1999 survey of pediatric emergency medicine physicians suggested that the FAST examination was used for less than 15% of injured children evaluated for possible intra-abdominal injuries. Similarly, in a 2007-2010 observational study conducted in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network the FAST examination was used for 14% of children with blunt torso trauma.

The objective of this study was to determine if the FAST examination performed during the initial evaluation of hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma decreases abdominal CT use, ED LOS, and hospital charges without significantly increasing missed intra-abdominal injuries. It was hypothesized that evaluating children with blunt torso trauma with the FAST examination would result in improved care and reduced costs.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This randomized, nonblinded clinical trial involving children with blunt torso trauma was conducted at the University of California, Davis Medical Center, a large urban, level I pediatric trauma center (April 2012-May 2015). The local institutional review board approved the study (See the Supplement for the study protocol). Once guardians of enrolled patients arrived in the ED, they consented to participate in a telephone follow-up.

Selection of Participants

Hemodynamically stable children and adolescents (<18 years) with blunt torso trauma presenting to the ED within 24 hours of the traumatic event were eligible. Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box) were designed to identify a study population with an approximate 5% risk of intra-abdominal injury. To assess for enrollment bias, we collected basic information from all eligible patients who were not enrolled.

Box. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Inclusion Criteria (Eligible If Any Criteria Below Met)

-

Blunt torso trauma resulting from a significant mechanism of injury

Motor vehicle collision: faster than 60 mph (96 kmph), ejection, or rollover

Automobile vs pedestrian or bicycle: automobile speed faster than 25 mph (40 kmph)

Falls greater than 20 ft (6 m) in height

Crush injury to the torso

Physical assault involving the abdomen

Decreased level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale score <15 or age-appropriate behavior) in association with blunt torso trauma

-

Blunt traumatic event with any of the following (regardless of the mechanism):

Extremity paralysis

Multiple long bone fractures (eg, tibia and humerus fracture)

History and physical examination suggestive of intra-abdominal injury following blunt torso trauma of any mechanism (including mechanisms of injury of less severity than mentioned above)

Exclusion Criteria

Prehospital or ED age-adjusted hypotension

Prehospital or ED Glasgow Coma Scale score <9

Presence of an abdominal seat belt sign

Penetrating trauma

Traumatic injury occurring more than 24 hours prior to the time of ED presentation

Transfer of the patient to the study site ED from an outside facility with abdominal CT scan, diagnostic peritoneal lavage, or laparotomy previously performed

Patients with known disease processes resulting in intraperitoneal fluid (eg, liver failure, ventriculoperitoneal shunts)

Intervention

Children were stratified into 3 age categories (< 3 years, 3-9.99 years, and ≥10 years) and randomized in blocks of 20 within these age cohorts. The allocation schedule was generated using random number functions in SAS software by the statistician. Bedside FAST examinations were performed on patients randomized to the FAST group by the ED physicians providing care. All ED physicians participating in this study were required to be certified in performing FAST examinations based on guidelines of the American College of Emergency Physicians. FAST examinations were performed using a portable ultrasound scanner with 3.5 MHz and 5.0 MHz transducers (Zonare Z One Ultra, Mindray). Patients underwent standard FAST examinations including views of the Morison pouch, the splenorenal fossa, long and short axis of the pelvis, and subxyphoid views. No attempts to image the solid organs or intraperitoneal gutters were made because these views are not routine in the FAST examination. All FAST examinations were uploaded and backed up on a server. Emergency department physicians caring for the patients made bedside interpretations and recorded them on the data collection forms and on the ultrasound at the time of imaging. Bedside FAST examination results were classified as positive if any intraperitoneal fluid was identified or negative if no such fluid was noted. FAST examinations were categorized as indeterminate if the bedside physician was unable to make a definitive determination. For study purposes, all FAST examination results were presented for interpretation to 1 of 2 experienced ED ultrasonographers (K.M.K., J.S.R.). These reviewers were masked to all clinical data and categorized FAST examinations as positive, negative, or indeterminate for intraperitoneal fluid.

Data Collection

Emergency department physicians completed data collection forms at the initial evaluation and documented pertinent patient history and physical examination findings. All efforts were made to minimize missing data during ED data collection. Physicians documented their suspicion of intra-abdominal injury, both before and after the FAST examination (in the FAST group), as one of the following: less than 1%, 1% to 5%, 6% to 10%, 11% to 50%, or more than 50%. In addition, physicians documented whether the FAST examination results changed their decision to obtain an abdominal CT scan. Patient cases were managed by ED physicians, along with pediatric surgeons, trauma surgeons, or both. Interactions between physicians were not dictated by study protocol. No protocol for obtaining abdominal CT was in place during the study.

Patients were hospitalized at the discretion of the treating physicians. Data from hospitalized patients’ electronic medical records were collected for determination of outcomes by research coordinators masked to randomization group. For those patients discharged from the ED, the guardians were contacted 1 week after the ED visit. The telephone survey assessed for any possible missed intra-abdominal injuries or abdominal CT scans performed after the ED visit. For those guardians unable to be contacted after 6 telephone attempts, the patient’s medical records and ED and trauma process improvement records were reviewed to identify any patients with possible missed injuries.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were the rate of abdominal CT use, missed intra-abdominal injuries, ED LOS, and hospital charges. Abdominal CT use was defined as the proportion of patients undergoing abdominal CT scans during their ED evaluation or hospitalization. A missed intra-abdominal injury was defined by diagnosis of such an injury after the patient left the ED. The ED LOS was defined as the time from ED arrival to disposition determination (ie, writing of admission or discharge orders). Hospital charges were collected from the study site’s billing office and reflect the total charges for the index ED visit and hospitalization (if hospitalized).

Additional nonprespecified outcome data collected included time to abdominal CT, hospital LOS, and physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury before and after the FAST examination (for patients in the FAST group). Time to abdominal CT was defined as the time from ED arrival to CT imaging.

Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

Sample size calculations were made a priori for all primary outcome measures except missed intra-abdominal injury (due to its expected infrequency). All sample size calculations assumed an α of .05, under 2-sided hypothesis testing, and β error of .20 (power = 80%).

A 1-hour decrease in ED LOS was considered clinically important. Based on preliminary data from the study site including a hospitalization rate of 64% and a mean ED LOS of 8.1 (SD, 4) hours for hospitalized patients and 5.1 (SD, 3) hours for discharged patients, a 1-hour decrease in ED LOS would require 504 admitted patients and 284 discharged patients (788 total patients). This would allow detection of important differences in analyses stratified by admission status in the hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients, respectively. A 10 percentage-point reduction in the abdominal CT rate was considered clinically important and feasible based on prior studies demonstrating a 16 percentage-point CT reduction in injured adults and a 13 percentage-point reduction in injured children with the use of the FAST examination. Based on preliminary data demonstrating an abdominal CT rate of 60% among injured children, a sample size of 776 patients was required. A 15% charge reduction (the charge for 1 abdominal CT scan) was considered important. Based on preliminary data demonstrating mean charges of $36 491 (SD, $29 537), 916 patients were required to detect the hypothesized reduction of $5474. Hence, the latter outcome necessitated setting our target sample size to 916.

Missing data were minimal; therefore, no statistical imputation was performed. All continuous data except for hospital charges were described as the mean and 1 SD and compared using the t test. Hospital charges had a skewed distribution and thus were reported as the median with first and third quartiles (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared them using quantile regression. Categorical data were compared using the χ2 test for association, unless any expected cell frequencies were less than 5, when the Fisher exact test was used. Agreement between the ED physician and the ED ultrasound expert was measured with a weighted κ (95% CI) for agreement (using the default Chichetti-Allison weights). The McNemar χ2 test was used to compare differences in proportions between before and after FAST physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury. All statistical tests were 2 sided with a P value of .05 considered significant. Effect sizes summarizing between-group differences were expressed with 95% CIs. Hypothesis tests and 95% CIs were computed without adjustment for multiple comparisons because our analyses were limited to a single prespecified primary outcome for each outcome domain. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software 14 (StataCorp LP).

Results

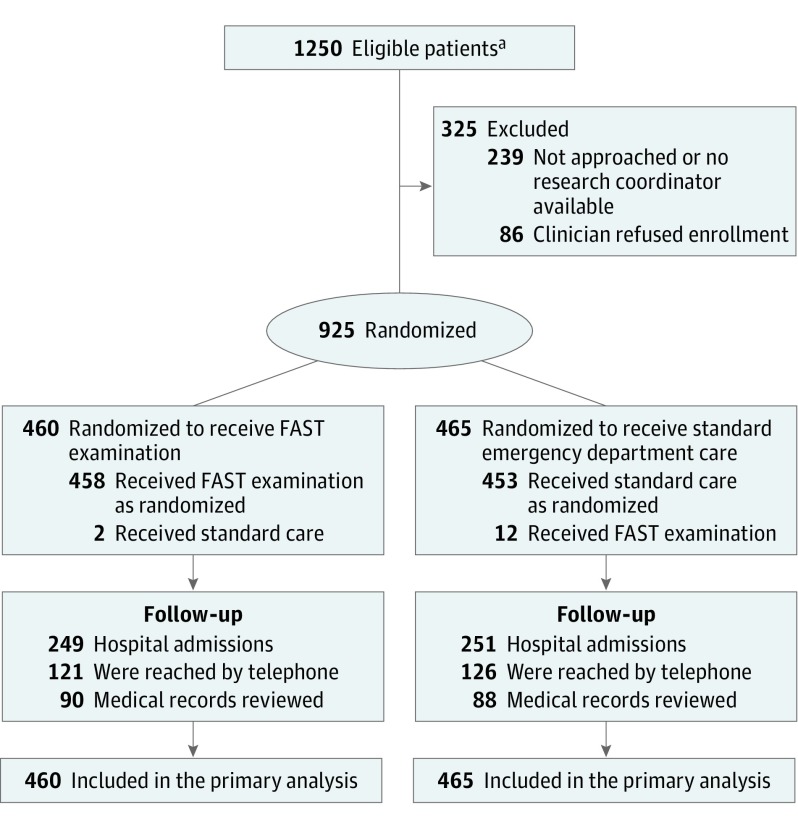

Twelve hundred fifty patients met eligibility criteria during the study. Of these, 925 (74%) were enrolled into the study (Figure 1) and comprised the study population. Mean age was 9.7 (SD, 5.3) years and 575 (62%) were male. Median Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15 (IQR, 15-15) and Pediatric Trauma Score was 10 (IQR, 10-11). Fifty patients (5.4%; 95% CI, 4.0%-7.1%) were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injuries, including 40 (80%; 95% CI, 66%-90%) with intraperitoneal fluid detected by abdominal CT scan, and 9 (0.97%; 95% CI, 0.44%-1.8%) underwent laparotomy.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Pediatric Patients With Blunt Torso Trauma.

aThe number of patients screened who met the exclusion criteria are not available.

FAST indicates focused assessment with sonography for trauma.

Four hundred sixty patients were randomized to the FAST examination group and 465 to the standard care–only group. Baseline demographics for the 2 groups were similar (Table 1). Eligible patients not enrolled (n = 325) were similar to enrolled patients (Table 1) although enrolled patients had a lower percentage of falls and a higher percentage of automobile vs pedestrians or bicycle events. Participating ED physicians included 35 board-certified or eligible emergency physicians and 5 board-certified pediatric emergency physicians.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| No. (%) of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| FAST Examination (n = 460) |

Standard Care Only (n = 465) |

Eligible but Not Enrolled (n = 325) |

|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 9.7 (5.3) | 9.7 (5.3) | 9.5 (5.8) |

| Male sex | 286 (62) | 289 (62) | 201 (62) |

| Mechanism of injury | |||

| MVC | 139 (30) | 138 (30) | 90 (28) |

| Motorcycle | 33 (7) | 41 (9) | 15 (5) |

| Fall | 95 (21) | 102 (22) | 99 (30) |

| Auto vs pedestrian or bikea | 98 (21) | 111 (24) | 56 (17) |

| Fall from bike | 29 (6) | 17 (4) | 17 (5) |

| Assault | 12 (3) | 10 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Blow to abdomen | 14 (3) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Other | 40 (9) | 41 (9) | 37 (11) |

| Initial GCS score, median (IQR), scoreb | 15 (15-15) | 15 (15-15) | |

| Pediatric Trauma Score, median (IQR)c | 11 (10-11) | 10 (10-11) | |

| Abdominal tenderness | 159 (35) | 151 (32) | |

| Physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury, %d | |||

| <1 | 105 (23) | 129 (28) | |

| 1-5 | 201 (44) | 177 (38) | |

| 6-10 | 95 (21) | 88 (19) | |

| 11-50 | 48 (10) | 65 (14) | |

| >50 | 9 (2) | 4 (1) | |

| Intra-abdominal injurye | 24 (5.2) | 26 (5.6) | 14 (4.3) |

| Intra-abdominal injury with intraperitoneal fluide | 19 (4.1) | 21 (4.5) | 10 (3.1) |

Abbreviations: FAST, focused assessment with sonography for trauma; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; IQR, interquartile range; MVC, motor vehicle collision.

Patients were struck by an automobile while a pedestrian or bicyclist.

Missing for 2 patients. The GCS scores reflect patient mental status and range from 3 to 15 with a score of 3 indicating coma and 15 reflecting normal alertness.

Missing for 4 patients. The score reflects the severity of injury and predicts mortality, and ranges from −6 (most severely injured) to 12 (least severely injured).

Missing for 4 patients.

Intra-abdominal injury and intra-abdominal injury with intraperitoneal fluid were identified by either abdominal CT scan or exploratory laparotomy.

Coprimary Outcomes

No significant differences between groups were identified in the rates of abdominal CT scans (difference, −2.2%; 95% CI, −8.7% to 4.2%, P = .50), missed intra-abdominal injuries (difference, 0.2%; 95% CI, −0.6% to 1.2%; P = .50), ED LOS (difference, −0.04 hours; 95% CI, −0.47 to 0.40 hours; P = .88), or hospital charges (difference, −$1180; 95% CI, −$6651 to $4291; P = .67; Table 2). One case of missed intra-abdominal injury occurred in the FAST group. This patient was a 13-year-old male struck by a car while riding his bicycle. He had a negative FAST examination and had normal liver transaminases. Following ED observation, the patient underwent abdominal CT for continued abdominal pain. Initial interpretation of the CT was negative and the patient was discharged home. The following day a pediatric radiologist reinterpreted the CT as showing a grade 1 liver laceration. The patient returned to the ED and was admitted for observation.

Table 2. Patient Outcomes.

| No. (%) of Patients | Difference (95% CI), %a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FAST Examination (n = 460) |

Standard Care Only (n = 465) |

||

| Abdominal CT | 241 (52.4) | 254 (54.6) | −2.2 (−8.7 to 4.2) |

| Missed intra-abdominal injuries | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.2) |

| ED LOS, mean (SD) [95% CI], h | 6.03 (3.07) [5.76 to 6.31] |

6.07 (3.71) [5.73 to 6.40] |

−0.04 (−0.47 to 0.40) |

| Hospital charges, median (IQR), $ thousands | 46.4 (32.3 to 74.9) | 47.8 (33.0 to 79.8) | −1.2 (−6.6 to 4.3) |

| Time to CT | |||

| No. of patients | 238 | 253 | |

| Mean (SD) [95% CI], h | 2.65 (1.66) [2.44 to 2.86] |

2.54 (1.77) [2.32 to 2.76] |

0.11 (−0.20 to 0.42) |

| Laparotomy | 7 (1.5) | 2 (0.4) | 1.1 (−0.3 to 2.7) |

| Hospitalization | 249 (54.1) | 251 (54.0) | 0.2 (−6.3 to 6.6) |

| ICU admission | 76 (16.5) | 76 (16.3) | 0.2 (−4.6 to 5.0) |

| Hospital LOS, median (IQR), h | 29.6 (18.3 to 63.3) | 40.2 (19.9 to 82.6) | −10.7 (−19.7 to −1.6) |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; FAST, focused assessment with sonography for trauma; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay.

The difference in the median hospital charges and hospital LOS was computed using quantile regression. Confidence intervals for risk differences for rare outcomes were computed using Newcombe hybrid score method, as implemented in Joseph Coveney’s Stata module rdci. Confidence intervals are otherwise based on standard large-sample methods.

Nonprespecified Analyses

Hospitalization and laparotomy rates and time to CT were not significantly different between the 2 groups, but the hospital LOS was shorter in patients randomized to the FAST examination (Table 2). All 9 patients undergoing laparotomy had abdominal CT scans performed in the ED prior to laparotomy.

Fourteen patients (3%) were considered to have indeterminate FAST examinations by the treating physicians and all underwent abdominal CT scanning. Agreement in FAST interpretations between the treating physicians and the ultrasound expert reviewer was moderate (κ, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.30-0.60; Table 3). Among the 19 patients in the FAST cohort who had intra-abdominal injuries and intraperitoneal fluid on CT, the treating physicians’ FAST interpretations were 5 positive, 10 negative, and 4 indeterminate. The ultrasound expert reviewer interpreted 6 positive, 12 negative, and 1 indeterminate.

Table 3. Agreement Between Emergency Medicine Physician and Ultrasound Expert Reviewer in Those Randomized to Receive FAST Examination (n = 451)a.

| Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Expert | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positiveb | Indeterminateb | Negativeb | ||

| Emergency medicine physician | ||||

| Positiveb | 13 (57) | 1 (6) | 11 (2.4) | 25 |

| Indeterminateb | 0 | 4 (25) | 10 (2.4) | 14 |

| Negativeb | 10 (43) | 11 (69) | 391 (94.9) | 412 |

| Total | 23 | 16 | 412 | 451 |

Abbreviation: FAST, focused assessment with sonography for trauma.

Cells report No. (%) of patients. Missing data for FAST interpretations (n = 9) are not included.

FAST examinations were thought positive if intraperitoneal fluid was present and negative if none was identified on any of the views obtained.

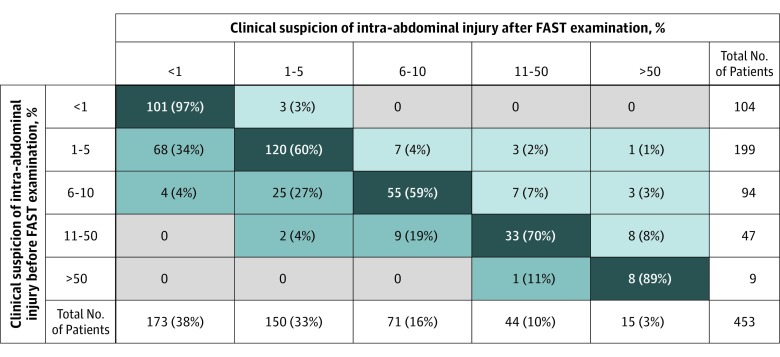

In the FAST group, physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury decreased after the performance of the FAST examination (Figure 2). The proportion of patients with physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury of less than 1% increased after the FAST examination (change in proportion, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.11-0.18; P < .001). Similarly, the proportion of patients with physician suspicion of 5% or less increased following the FAST examination (change in proportion, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.02-0.07; P = .002). Among the 173 patients considered to have a risk of intra-abdominal injury of less than 1% after the FAST examination, none (0%, 95% CI, 0%-1.7%) were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injury, and 49 (28%, 95% CI, 22%-36%) underwent abdominal CT. Physicians documented changes in their plans to order CTs for 25 patients after the FAST examination. In 13 cases, physicians decided not to perform a planned abdominal CT following the FAST examination, and none were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injuries. In 12 cases, physicians decided to obtain an abdominal CT when a CT scan was not planned prior to the FAST examination. One was diagnosed with an intra-abdominal injury. In this case, the FAST examination demonstrated intraperitoneal fluid in the Morison pouch. After the development of peritonitis, the patient was found to have a jejunal injury.

Figure 2. Clinician Suspicion of Intra-abdominal in the FAST Group Before and After the FAST Examination.

Seven patients had missing data for clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury either before or after the focused assessment with sonography (FAST) examination and are not included in this figure. Rows represent clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury prior to performing the FAST examination. Columns represent clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury after performing the FAST examination; data represent No. (%) of patients. The dark blue cells (diagonal) represent no change in clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury after the FAST examination; light blue (above the diagonal), increased clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury after the FAST examination; and medium blue (below the diagonal), decreased clinician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury after the FAST examination.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of hemodynamically stable children treated in an ED following blunt torso trauma, the use of the FAST examination compared with standard care only did not improve any of the primary outcomes including resource use, ED LOS, missed intra-abdominal injuries, or hospital charges. Therefore, the study suggests that the routine use of the FAST examination in hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma may not be useful.

These results differ from 2 earlier randomized clinical trials involving injured adults. Both studies demonstrated substantial improvement in clinical care (decrease in abdominal CT rate, complications, and charges) and improved patient throughput of the patients randomized to undergo the FAST examination. The current study identified decreased hospital LOS in the FAST group similar to 1 of the adult studies. This finding, however, may be due to chance, and the clinical importance of this difference is unclear.

The results of a large, multicenter observational study of injured children suggested that children considered to be at low risk of intra-abdominal injury (ie, 1%-10% pre-FAST risk assessment of intra-abdominal injury) had a lower rate of abdominal CT scans if FAST examinations were performed. In that study, the FAST examination had little effect on abdominal CT use in children considered to have a risk of intra-abdominal of more than 10%. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that the FAST examination has a negative likelihood ratio of 0.36 for hemoperitoneum, and therefore a negative result has the largest clinical effect on posttest probability of intra-abdominal injury when pretest suspicion is low. However, the FAST examination should not influence clinical decision making regarding CT use when patients are considered at substantial risk.

Despite the findings of the 2 randomized clinical trials of adults and the large multicenter pediatric observational study, there is little prior evidence supporting the routine use of the FAST examination for children with blunt torso trauma. A single-center observational study (involving children) also questioned the utility of the FAST examination due to its limited sensitivity (50%). Similarly, the results of a prospective observational study of 357 children undergoing FAST examinations also suggests that the utility of FAST examinations is low due to the low sensitivity (52%) and marginal negative likelihood ratio (0.50). These results led the authors to conclude that a negative FAST test result “aids little in decision making.” The results of our trial support this assertion because physicians did not frequently alter care based on the examination results.

In our study, the use of the FAST examination was associated with a decrease in physician suspicion of intra-abdominal injury. This decrease was primarily seen in children initially believed to have a 1% to 10% risk of intra-abdominal injury prior to the FAST examination. Changes in physician suspicion associated with the FAST examination, however, did not result in decreases in abdominal CT use.

This study excluded certain high-risk patients, such as those with hypotension, for whom the FAST examination may have the potential to be beneficial. The FAST examination is considered the standard of care at the study site in hypotensive injured adults and has a reported sensitivity of 100% for hemoperitoneum in hypotensive injured children. Including these high-risk patients in the current study may have improved the sensitivity of the FAST examination.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, it was performed at a single site and specific aspects of clinical practice at the study site may have influenced the results. Participating physicians may have had preconceived notions regarding the utility of the FAST examination, which may have affected CT decision making and care provided. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other sites. A multicenter randomized clinical trial would more definitively answer the question regarding the utility of the FAST examination for injured children. Second, despite randomizing 925 patients, the study may not have been adequately powered to detect small differences in outcomes between the 2 groups or in different age strata.

Third, a population with an approximate 5% risk of intra-abdominal injury was targeted. This was chosen because of the limited test sensitivity of the FAST examination, and abdominal CT is likely indicated for most children with higher risk. Thus, FAST test characteristics in the current study given this selected patient population should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the study measured and analyzed differences in charges between the 2 groups. However, charges do not reflect the true cost of care that was delivered to the patient.

Fifth, because the intervention being studied must be performed by the treating physician and the results known to the physician providing care, the study was not blinded. Research coordinators assessing outcomes, however, were blinded to study group assignment. Finally, agreement between the ED physicians and the ED ultrasound expert was only moderate. However, the aim of the study was not to assess agreement between physicians in the performance of the FAST examination but rather to evaluate the effect of the use of the FAST examination on clinical outcomes and resource use.

Conclusions

Among hemodynamically stable children treated in an ED following blunt torso trauma, the use of the FAST examination compared with standard care only did not improve clinical care, including use of resources; ED throughput; intra-abdominal injuries; or hospital charges. These findings do not support the routine use of the FAST examination in this setting.

Study Protocol.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department.

References

- 1.Ma OJ, Mateer JR, Ogata M, Kefer MP, Wittmann D, Aprahamian C. Prospective analysis of a rapid trauma ultrasound examination performed by emergency physicians. J Trauma. 1995;38(6):879-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH, Champion HR. Prospective evaluation of surgeons’ use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients. J Trauma. 1993;34(4):516-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stengel D, Rademacher G, Ekkernkamp A, Güthoff C, Mutze S. Emergency ultrasound-based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD004446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes JF, Gladman A, Chang CH. Performance of abdominal ultrasonography in pediatric blunt trauma patients: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(9):1588-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melniker LA, Leibner E, McKenney MG, Lopez P, Briggs WM, Mancuso CA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of point-of-care, limited ultrasonography for trauma in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(3):227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose JS, Levitt MA, Porter J, et al. . Does the presence of ultrasound really affect computed tomographic scan use? a prospective randomized trial of ultrasound in trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51(3):545-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baka AG, Delgado CA, Simon HK. Current use and perceived utility of ultrasound for evaluation of pediatric compared with adult trauma patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(3):163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menaker J, Blumberg S, Wisner DH, et al. ; Intra-abdominal Injury Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) . Use of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination and its impact on abdominal computed tomography use in hemodynamically stable children with blunt torso trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):427-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes JF, Lillis K, Monroe D, et al. . Identifying children at very low risk of clinically important blunt abdominal injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Emergency Physicians https://www.acep.org/clinical---practice-management/ultrasound. Accessed May 23, 2017.

- 11.Scaife ER, Rollins MD, Barnhart DC, et al. . The role of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in pediatric trauma evaluation. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1377-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox JC, Boysen M, Gharahbaghian L, et al. . Test characteristics of focused assessment of sonography for trauma for clinically significant abdominal free fluid in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):477-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes JF, Harris D, Battistella FD. Performance of abdominal ultrasonography in blunt trauma patients with out-of-hospital or emergency department hypotension. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(3):354-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes JF, Brant WE, Bond WF, Sokolove PE, Kuppermann N. Emergency department ultrasonography in the evaluation of hypotensive and normotensive children with blunt abdominal trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(7):968-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):873-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol.