Key Points

Question

What is the variation in contrast volume and acute kidney injury incidence among US physicians after performing percutaneous coronary intervention?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study involving more than 1.3 million patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, a large variation in acute kidney injury incidence and contrast use was observed among physicians who performed the procedures. There was no evidence that physicians used significantly less contrast in patients at higher risk of acute kidney injury.

Meaning

The variation among physicians and the absence of an adjustment in contrast volume for patients at higher risk for acute kidney injury underscores an important opportunity to reduce acute kidney injury.

Abstract

Importance

Acute kidney injury (AKI) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is common, morbid, and costly; increases patients’ mortality risk; and can be mitigated by limiting contrast use.

Objective

To examine the national variation in AKI incidence and contrast use among US physicians and the variation’s association with patients’ risk of developing AKI after PCI.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used the American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) CathPCI Registry to identify in-hospital care for PCI in the United States. Participants included 1 349 612 patients who underwent PCI performed by 5973 physicians in 1338 hospitals between June 1, 2009, and June 30, 2012. Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2014, to August 31, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was AKI, defined according to the Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria as an absolute increase of 0.3 mg/dL or more or a relative increase of 50% or more from preprocedural to peak creatinine. A secondary outcome was the mean contrast volume as reported in the NCDR CathPCI Registry. Physicians who performed more than 50 PCIs per year were the main exposure variable of interest. Hierarchical regression with adjustment for patients’ AKI risk was used to identify the variation in AKI rates, the variation in contrast use, and the association of contrast volume with patients’ predicted AKI risk.

Results

Of the 1 349 612 patients who underwent PCI, the mean (SD) age was 64.9 (12.2) years, 908 318 (67.3%) were men, and 441 294 (32.7%) were women. Acute kidney injury occurred in 94 584 patients (7%). A large variation in AKI rates was observed among individual physicians ranging from 0% to 30% (unadjusted), with a mean adjusted 43% excess likelihood of AKI (median odds ratio, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.41-1.44) for statistically identical patients presenting to 2 random physicians. A large variation in physicians’ mean contrast volume, ranging from 79 mL to 487 mL with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.23 (interquartile range, 0.21-0.25), was also observed, implying a 23% variation in contrast volume among physicians after adjustment. There was minimal correlation between contrast use and patients’ AKI risk (r = −0.054). Sensitivity analysis after excluding complex cases showed that the physician variation in AKI remained unchanged.

Conclusions and Relevance

Acute kidney injury rates vary greatly among physicians, who also vary markedly in their use of contrast and do not use substantially less contrast in patients with higher risk for AKI. These findings suggest an important opportunity to reduce AKI by reducing the variation in contrast volumes across physicians and lowering its use in higher-risk patients.

This cross-sectional study uses NCDR CathPCI Registry data to examine the variation in contrast volume and acute kidney injury incidence among physicians who perform percutaneous coronary intervention.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is common, occurring in 7% of patients, but is a severely morbid and costly event that increases the risk of dialysis and mortality. Because hydration has modest benefit and administration of sodium bicarbonate and N-acetylcysteine has not proved to be effective in preventing AKI, reducing contrast volume may be the most effective strategy for preventing AKI.

Despite the morbidity and mortality of AKI, little is known about physician variation in contrast use in the United States and its association with AKI. A previous study found marked variation in AKI incidence rates directly associated with hospitals but did not examine the variability in physicians’ use of contrast, which is a modifiable factor for preventing AKI. We hypothesized that if physician variation in AKI incidence and contrast volumes exists, it would highlight an important opportunity to improve PCI safety. Using the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) CathPCI Registry, we examined (1) the variation in AKI rates among physicians, (2) the variation in physicians’ use of contrast, and (3) the association of contrast use with patients’ AKI risk.

Methods

Study Population

The NCDR CathPCI Registry has been previously described. This study included patients who underwent a PCI between June 1, 2009, and June 30, 2012 (N = 1 646 153), and excluded patients without preprocedure and postprocedure creatinine values (239 025 [14.5%]), those undergoing multiple PCIs during the hospitalization (32 999 [2.0%]), and those already undergoing dialysis (24 517 [1.5%]). The final analytical cohort included 1 349 612 patients undergoing PCI performed by 5973 physicians in 1338 institutions. The Chesapeake Institutional Review Board granted approval to the American College of Cardiology Foundation NCDR CathPCI Registry and waived the patient informed consent requirement. Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2014, to August 31, 2016.

Factors and Outcomes

The primary outcome of AKI was defined as the change from preprocedure creatinine levels to peak creatinine levels according to the Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria as an absolute increase of 0.3 mg/dL or more or as a relative increase of 50% or more from preprocedural to peak creatinine. A secondary outcome was the physicians’ mean contrast volume. This analysis was limited to physicians performing 50 or more PCIs. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation, and the preprocedural AKI risk was calculated from a previously validated NCDR CathPCI Registry model.

Statistical Analysis

Physician Variation in AKI Rate and Contrast Volume

To ascertain the unadjusted variation in AKI rate and mean contrast volume, we graphed the range of AKI by physicians and their mean contrast volume. For the adjusted variation in AKI by physicians, we developed a hierarchical logistic regression model, with AKI as the dependent variable and physician as the random effect to account for clustering while adjusting for confounders from the previously published NCDR CathPCI Registry AKI model. Our model yielded the physicians’ median odds ratio (MOR), an estimate of variation in AKI attributable to physicians when adjusted for confounders. We developed a similar hierarchical linear regression model with contrast volume as the dependent variable, which yielded the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), an estimate of the variation in contrast volumes explained by physicians when adjusted for confounders. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed t test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Two-sided P values were used to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 13.1 (SAS Institute Inc).

Association of Contrast Volume With Patients’ AKI Risk and AKI Incidence

To examine whether physicians used less contrast in patients with higher AKI risk, we correlated contrast use with AKI risk and calculated the mean contrast volume used, by deciles of AKI risk. To identify the association of physicians’ variation in contrast volume with their rate of AKI, we used a hierarchical logistic regression model with AKI as the dependent variable, physician as the random effect, and physicians’ mean contrast volume (per 75-mL increase in excess contrast) adjusted for patients’ AKI risk.

Sensitivity Analysis

Because procedural complexity may affect AKI variation by physicians, we performed a sensitivity analysis to examine whether physicians’ AKI variation differed by high or low PCI complexity. High PCI complexity consisted of left main PCI, multivessel PCI, chronic total occlusion PCI, type C lesions, and saphenous vein graft lesions. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted by overnight stay vs same-day discharge, physicians’ even vs odd National Provider Identifier number, and a more stringent definition of AKI as a creatinine level of 0.5 mg/dL or higher (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Among the 1 349 612 patients who underwent PCIs performed by 5973 physicians at 1338 hospitals, 908 318 (67.3%) were men and 441 294 (32.7%) were women, with a mean (SD) age of 64.9 (12.2%) years (Table). Acute kidney injury developed in 94 584 patients (7.0%), of whom 80 547 (85.2%) experienced stage I AKI, 6412 (6.8%) stage II, and 3440 (3.6%) stage III. Patients who developed AKI were more likely to have comorbidities, a higher pre-PCI creatinine level (mean [SD], 1.3 [0.8] vs 1.1 [0.5] mg/dL), and higher length of stay by almost 4 days (mean [SD], 5.7 [8.1] vs 2.0 [3.8] days).

Table. Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Procedural Characteristics by Presence of Acute Kidney Injurya.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 1 349 612) |

AKI (n = 94 584) |

No AKI (n = 1 255 028) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.9 (12.2) | 68.3 (12.4) | 64.6 (12.1) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 908 318 (67.3) | 57 310 (60.6) | 851 008 (67.8) |

| Female | 441 294 (32.7) | 37 274 (39.4) | 404 020 (32.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| White | 1 191 488 (88.3) | 80 492 (85.1) | 1 110 996 (88.5) |

| Black or African American | 107 778 (8.0) | 10 368 (11.0) | 97 410 (7.8) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.1 (12.8) | 30.5 (13.4) | 30.1 (12.7) |

| No insurance, No. (%) | 91 743 (6.8) | 5843 (6.2) | 85 900 (6.8) |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | 2.2 (4.3) | 5.7 (8.1) | 2.0 (3.8) |

| AKI Variables | |||

| Creatinine level, mean (SD), mg/dL | |||

| Before procedure | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| After procedure | 1.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.4) |

| New requirement for dialysis, No. (%) | 4185 (0.3) | 4185 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| AKI stage, No. (%)b | |||

| No AKI | 1 255 028 (93.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 255 028 (100.0) |

| Stage I | 80 547 (6.0) | 80 547 (85.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage II | 6412 (0.5) | 6412 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage III | 3440 (0.3) | 3440 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| New dialysis | 4185 (0.3) | 4185 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| GFR and contrast volume | |||

| GFR by MDRD equation, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2,c | 73.0 (22.6) | 64.1 (28.7) | 73.7 (22.0) |

| GFR level, No. (%), mL/min/1.73 m2 | |||

| Normal: >60 | 957 136 (70.9) | 48 945 (51.9) | 908 191 (72.4) |

| Mild: >45-60 | 229 427 (17.0) | 18 539 (19.7) | 210 888 (16.8) |

| Moderate: 30-45 | 123 017 (9.1) | 16 111 (17.1) | 106 906 (8.5) |

| Severe: <30 | 39 790 (2.9) | 10 747 (11.4) | 29 043 (2.3) |

| Contrast volume level, mL, No. (%) | |||

| 0-50 | 23 171 (1.7) | 1849 (2.0) | 21 322 (1.7) |

| 51-100 | 139 388 (10.4) | 9922 (10.5) | 129 466 (10.3) |

| 101-150 | 306 762 (22.8) | 19 967 (21.2) | 286 795 (22.9) |

| 151-200 | 350 100 (26.0) | 22 835 (24.2) | 327 265 (26.2) |

| 201-250 | 240 920 (17.9) | 16 441 (17.4) | 224 479 (17.9) |

| 251-300 | 141 460 (10.5) | 10 563 (11.2) | 130 897 (10.5) |

| 301-350 | 68 966 (5.1) | 5572 (5.9) | 63 394 (5.1) |

| 351-400 | 37 563 (2.8) | 3297 (3.5) | 34 266 (2.7) |

| >400 | 36 926 (2.7) | 3795 (4.0) | 33 131 (2.6) |

| Contrast volume, mean (SD), mL | 197.7 (90.5) | 205.7 (100.4) | 197.1 (89.6) |

| History, No. (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 486 687 (36.1) | 46 727 (49.4) | 439 960 (35.1) |

| Hypertension | 1 104 205 (81.9) | 81 899 (86.6) | 1 022 306 (81.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1 073 707 (79.6) | 73 186 (77.5) | 1 000 521 (79.8) |

| Family history of premature CAD | 330 477 (24.5) | 18 746 (19.8) | 311 731 (24.8) |

| Myocardial infarction | 404 299 (30.0) | 30 777 (32.6) | 373 522 (29.8) |

| Heart failure | 158 706 (11.8) | 21 782 (23.0) | 136 924 (10.9) |

| Valve surgery/procedure | 20 002 (1.5) | 1977 (2.1) | 18 025 (1.4) |

| PCI | 538 899 (39.9) | 34 524 (36.5) | 504 375 (40.2) |

| CABG | 249 692 (18.5) | 20 060 (21.2) | 229 632 (18.3) |

| Currently undergoing dialysis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 166 297 (12.3) | 17 664 (18.7) | 148 633 (11.8) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 165 465 (12.3) | 17 414 (18.4) | 14 8051 (11.8) |

| Chronic lung disease | 206 002 (15.3) | 19 336 (20.5) | 186 666 (14.9) |

| Anemia | 51 402 (3.9) | 10 521 (11.4) | 40 881 (3.3) |

| Current/recent smoker (within 1 y) | 376 391 (27.9) | 22 162 (23.5) | 354 229 (28.2) |

| Catheterization Laboratory Visit | |||

| CAD presentation, No. (%) | |||

| No presentation documented | 116 285 (8.6) | 6492 (6.9) | 109 793 (8.8) |

| Other symptoms | 36 897 (2.7) | 2285 (2.4) | 34 612 (2.8) |

| Stable angina | 216 050 (16.0) | 8240 (8.7) | 207 810 (16.6) |

| Unstable angina | 501 711 (37.2) | 27 500 (29.1) | 474 211 (37.8) |

| Non-STEMI | 262 515 (19.5) | 26 448 (28.0) | 236 067 (18.8) |

| STEMI | 215 727 (16.0) | 23 594 (25.0) | 192 133 (15.3) |

| Heart failure within 2 wk, No. (%) | 136 967 (10.2) | 23 815 (25.2) | 11 3152 (9.0) |

| Cardiomyopathy or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, No. (%) | 137 706 (10.2) | 17 223 (18.2) | 120 483 (9.6) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction before PCI, mean (SD), % | 52.3 (12.5) | 46.8 (15.0) | 52.6 (12.3) |

| Cardiogenic shock within 24 h, No. (%) | 25 553 (1.9) | 8573 (9.1) | 16 980 (1.4) |

| IABP used during admission, No. (%) | 34 421 (2.6) | 10 861 (11.5) | 23 560 (1.9) |

| IABP used before PCI, No. (%) | 3439 (0.3) | 1141 (1.2) | 2298 (0.2) |

| Cardiac arrest within 24 h, No. (%) | 25 400 (1.9) | 5829 (6.2) | 19 571 (1.6) |

| Fluoroscopy time, mean (SD), min | 14.8 (11.7) | 17.1 (13.6) | 14.6 (11.5) |

| Outcomes, No. (%) | |||

| Death in hospital | 16 019 (1.2) | 9340 (9.9) | 6679 (0.5) |

| Myocardial infarction (biomarker positive) | 29 184 (2.2) | 3518 (3.7) | 25 666 (2.0) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 13 838 (1.0) | 5965 (6.3) | 7873 (0.6) |

| Heart failure | 14 705 (1.1) | 6101 (6.5) | 8604 (0.7) |

| CVA/stroke | 3305 (0.2) | 1033 (1.1) | 2272 (0.2) |

| Other vascular complications requiring treatment | 6271 (0.5) | 1395 (1.5) | 4876 (0.4) |

| Received RBCs/whole blood transfusion | 38 809 (2.9) | 14 714 (15.6) | 24 095 (1.9) |

| Bleeding event within 72 h | 25 247 (1.9) | 6465 (6.8) | 18 782 (1.5) |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RBCs, red blood cells; Scr, serum creatinine; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

P < .001 for all comparisons between the AKI and no AKI groups. Continuous variables were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed t test; categorical variables, using the χ2 or Fisher exact test.

Classification/staging system for AKI is as follows: Stage 1: increase in serum creatinine of more than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL (≥26.4 μmol/L) or increase to more than or equal to 150% to 200% (1.5- to 2-fold) from baseline. Stage 2: increase in serum creatinine to more than 200% to 300% (>2-fold to 3-fold) from baseline. Stage 3: increase in serum creatinine to more than 300% (>3-fold) from baseline (or serum creatinine of more than or equal to 4.0 mg/dL [≥354 μmol/L] with an acute increase of at least 0.5 mg/dL [44 μmol/L]).

The MDRD equation is as follows: GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 175 × (Scr)−1.154 × (Age)−0.203 × (0.742 if female) × (1.212 if African American).

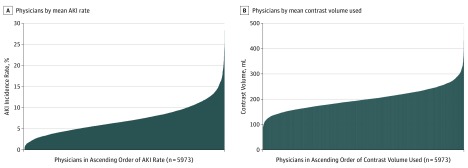

Physician Variation in AKI Rate and Contrast Volume

We observed wide variation in AKI rates across physicians from 0% to 30% (Figure 1A). When adjusted for patient characteristics and AKI risk, we found significant variation in AKI rates across physicians (MOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.41-1.44; P < .001), implying a mean 43% excess AKI risk for statistically identical patients treated by 2 random physicians. We observed significant variation in physicians’ mean contrast volume (range, 79-487 mL) (Figure 1B). When adjusted for patient characteristics and accounting for differences across physicians, we found a significant variation in contrast volumes across physicians (ICC, 0.23; interquartile range, 0.21-0.25; P < .001), implying that 23% of the variation in contrast volume was directly explained by physicians rather than by patient characteristics.

Figure 1. Variation in Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Incidence Rate and Mean Contrast Volume per Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Among US Physicians.

A, Physicians (on the x-axis) are listed in ascending order according to their AKI rate, lowest to highest. B, Physicians (on the x-axis) are listed in ascending order according to their mean contrast volume used, lowest to highest.

Association of Contrast Volume With AKI Rates

As expected, higher contrast use was associated with higher AKI rates (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Physicians who used more contrast had an odds ratio of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.40-1.43) per incremental 75-mL increase in contrast use (P < .001) after adjusting for patient characteristics and AKI risk. Thus, every incremental 75 mL of contrast used increased the risk of AKI by 42%. A scatterplot (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) demonstrates that physicians who used more contrast had patients with a higher rate of observed AKI.

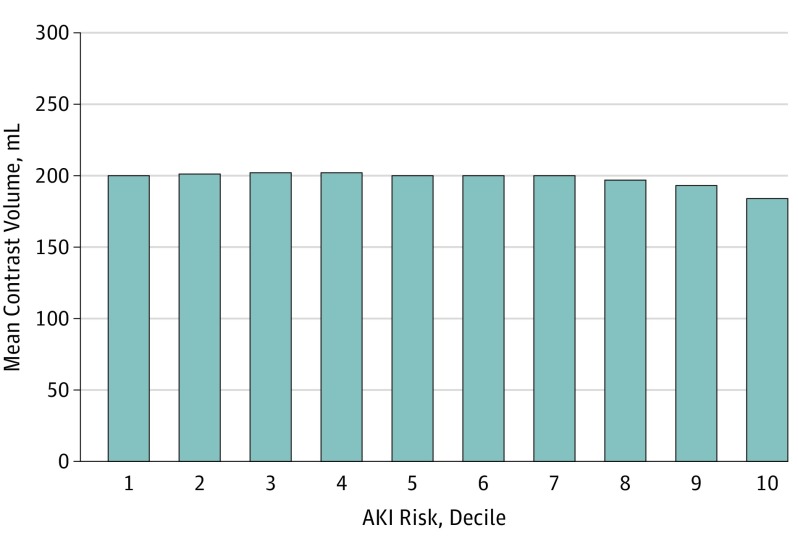

Association of Patients’ AKI Risk With Contrast Use

Unlike the expectation that patients with higher AKI risk would be treated with less contrast, a minimal association was observed between patients’ AKI risk and contrast volumes (r = −0.054). The contrast used remained fairly constant over deciles 1 to 9 of AKI risk (Figure 2), with only a minimal (16-mL) mean reduction in the highest risk decile.

Figure 2. Physicians’ Mean Contrast Volume by Deciles of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) Risk.

The AKI risk is calculated by using variables from the parsimonious AKI risk prediction model: sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, and race), clinical risk factors (prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, bypass surgery or heart failure, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, lung disease, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and baseline chronic kidney disease stage), and other disease severity characteristics (stable angina, unstable angina, non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction or ST-elevation myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and use of a balloon pump).

Sensitivity Analysis

Approximately 675 000 patients (50%) belonged to the high-complexity cohort. Sensitivity analysis of physician variation in AKI in the high PCI complexity vs low PCI complexity groups showed that the MOR for the low PCI complexity cohort was 1.45 (95% CI, 1.43-1.48) and for the high PCI complexity cohort was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.39-1.43). Thus, physician variation in AKI remained essentially unchanged by PCI complexity. Additional sensitivity analyses by overnight stay vs same-day discharge, physicians’ even vs odd National Provider Identifier number, and a more stringent definition of AKI as 0.5 mg/dL or higher showed that the physician variation in AKI and contrast remained unchanged.

Discussion

Acute kidney injury is a serious complication of PCI that is associated with high morbidity, mortality, length of stay, and costs. To our knowledge, this study of more than 1.3 million patients on the NCDR CathPCI Registry is the first that highlights an important opportunity for reducing contrast use and AKI. We observed a large variation in AKI rates and contrast volume among physicians, independent of patient factors. Unlike the expectation that patients with higher risk of AKI would be treated with less contrast, we found a minimal reduction of contrast volumes in patients with higher risk of AKI. In addition, we found that the physician variation in AKI did not change by PCI complexity, implying that variation in AKI is attributable to physician practices rather than case complexity. Thus, our study lays the foundation for national efforts to reduce AKI rates by extending the strategies of Brown et al and by providing clinicians with safe contrast volumes prior to PCI procedures.

We can surmise that variation in contrast volumes is perhaps associated with frequent injections, ventriculograms, larger bore guides, trainees’ involvement, multivessel PCI without staging the second or third vessel, and variation in interventional techniques of wiring lesions and balloon and stent placement, which all consume contrast. A qualitative study is needed on such interventional practices and the potential unintended consequences of efforts to reduce contrast.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, these data do not provide reasons for the variation in contrast volumes and AKI. Second, there may be residual risk factors and confounding that the study did not capture, such as extreme tortuosity and calcification that required more contrast. Third, misclassification of contrast volume because of voluntary self-reporting to the NCDR CathPCI Registry may exist, but this misclassification would have to vary markedly across physicians to negate our findings. Fourth, we excluded 239 025 patients (14.5%) who did not have 2 creatinine values, and it is possible that missing creatinine levels could cluster by physician and confound the results. Fifth, our data do not account for different types of contrast media. Finally, AKI is multifactorial; cholesterol embolization, low cardiac output, hydration, and nephrotoxic medications contributing to AKI are not well captured in the NCDR CathPCI Registry and should be explored as contributing factors for AKI.

Conclusions

We found that AKI rates and contrast volumes vary substantially among physicians. A significant proportion of this variation was associated with differences in contrast use. Moreover, there was little evidence that physicians were limiting the amount of contrast in patients at higher risk for AKI. Furthermore, the physician variation in AKI incidence remained unchanged after excluding complex cases. This study underscores an important opportunity to reduce AKI by reducing the variation in contrast volumes used by physicians across US centers.

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Increasing Contrast Volume and AKI

eFigure 2. Correlation Between Physicians’ Average Contrast Volume Used and Their Average Observed AKI Rate

References

- 1.Tsai TT, Patel UD, Chang TI, et al. . Validated contemporary risk model of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Cath-PCI Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai TT, Patel UD, Chang TI, et al. . Contemporary incidence, predictors, and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: insights from the NCDR Cath-PCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amin AP, Shapiro R, Novak E, et al. . Costs of contrast induced acute kidney injury [Abstract 316]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(suppl 1):A316. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin AP, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al. . The prognostic importance of worsening renal function during an acute myocardial infarction on long-term mortality. Am Heart J. 2010;160(6):1065-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brar SS, Hiremath S, Dangas G, Mehran R, Brar SK, Leon MB. Sodium bicarbonate for the prevention of contrast induced-acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1584-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoste EA, De Waele JJ, Gevaert SA, Uchino S, Kellum JA. Sodium bicarbonate for prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(3):747-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACT Investigators Acetylcysteine for prevention of renal outcomes in patients undergoing coronary and peripheral vascular angiography: main results from the randomized Acetylcysteine for Contrast-Induced Nephropathy Trial (ACT). Circulation. 2011;124(11):1250-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin P, Bach RG, Kosiborod M, et al. . Abstract 354: large variation in contrast use during PCI—an important opportunity for reducing acute kidney injury. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(suppl 1):A354. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin AP, Salisbury AC, McCullough PA, et al. . Trends in the incidence of acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moussa I, Hermann A, Messenger JC, et al. . The NCDR CathPCI Registry: a US national perspective on care and outcomes for percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2013;99(5):297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration . Using standardized serum creatinine values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen K, Petersen JH, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Endahl L. Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics. 2000;56(3):909-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. . A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S, Lake ET. Multilevel modeling of a clustered continuous outcome: nurses’ work hours and burnout. Nurs Res. 2005;54(6):406-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JR, Solomon RJ, Sarnak MJ, et al. ; Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group . Reducing contrast-induced acute kidney injury using a regional multicenter quality improvement intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(5):693-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. ; Acute Kidney Injury Network . Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafiq A, Pokarel Y, Qintar M, Kennedy K, Spertus JA, Amin AP. A novel method for estimating the optimal contrast amount needed to minimize acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention [abstract 110]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:A110. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurm HS, Dixon SR, Smith DE, et al. ; BMC2 (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium) Registry . Renal function-based contrast dosing to define safe limits of radiographic contrast media in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(9):907-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Increasing Contrast Volume and AKI

eFigure 2. Correlation Between Physicians’ Average Contrast Volume Used and Their Average Observed AKI Rate