Abstract

Because virtually all tissues contain blood vessels, the importance of hemevascularization has been long recognized in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. However, the lymphatic vasculature has only recently become a subject of interest. Central to the task of growing a lymphatic network are lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), which constitute the innermost layer of all lymphatic vessels. The central molecule that directs proliferation and migration of LECs during embryogenesis is vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C). VEGF-C is therefore an important ingredient for LEC culture and attempts to (re)generate lymphatic vessels and networks. During its biosynthesis VEGF-C undergoes a stepwise proteolytic processing, during which its properties and affinities for its interaction partners change. Many of these fundamental aspects of VEGF-C biosynthesis have only recently been uncovered. So far, most—if not all—applications of VEGF-C do not discriminate between different forms of VEGF-C. However, for lymphatic regeneration and engineering purposes, it appears mandatory to understand these differences, since they relate, e.g., to important aspects such as biodistribution and receptor activation potential. In this review, we discuss the molecular biology of VEGF-C as it relates to the growth of LECs and lymphatic vessels. However, the properties of VEGF-C are similarly relevant for the cardiovascular system, since both old and recent data show that VEGF-C can have a profound effect on the blood vasculature.

Keywords: vascular endothelial growth factor C, lymphatic vessels, lymphedema, tissue engineering, A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3, collagen and calcium binding EGF domains 1, growth factors, VEGF receptors

Introduction

Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) form the innermost layer of lymphatic vessels, and they play a central role during the growth of the lymphatic system (Bautch and Caron, 2015). Lymphatic insufficiency can be the result of an underdeveloped lymphatic network (Butler et al., 2009), and hence the idea of growing lymphatic structures has been proposed early on as a potential treatment strategy for lymphedema (Karkkainen et al., 2001a; Saaristo et al., 2002). Irrespective of whether these structures are regrown in situ (Karkkainen et al., 2001b; Dai et al., 2010; Moriondo et al., 2010; Güç et al., 2017) or in vitro (Helm et al., 2007; Gibot et al., 2017; Knezevic et al., 2017), the growth and assembly of LECs into vessels and networks are central to the task of lymphatic engineering (Kanapathy et al., 2014; Schaupper et al., 2016).

Therefore, it is appropriate—when setting out to (re)construct lymphatic vessels—to get familiar with LEC proliferation, migration, assembly, and maintenance. The central growth factor that mediates these tasks is vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C). While being a member of the VEGF family of growth factors, VEGF-C is in many aspects very different from the vascular endothelial growth factor prototype VEGF-A.

VEGFs and VEGF Receptors (VEGFRs)

The primary receptors of all VEGF family members are tyrosine kinase receptors. With certain exceptions (Olsson et al., 2006), they are only expressed by endothelial cells. However, all three VEGFRs (VEGFR-1, -2 and -3) are not equally distributed on endothelial cells. In the adult organism, VEGFR-3 expression is largely restricted to LECs (Kaipainen et al., 1995), while VEGFR-1 expression is very low on LECs (Shibuya, 2001), and VEGFR-2 can be found both on LECs and blood vascular endothelial cells (BECs) (Holmes et al., 2007). VEGFRs are activated by dimerization, which is achieved by the dimeric nature of the VEGF ligands. The two receptor binding epitopes of each VEGF ligand are composite epitopes and are absent in monomeric VEGF species (Muller et al., 1997). Hence, monomeric VEGF species bind their respective receptors only with low affinity (Fuh et al., 1998) or not at all (Grunewald et al., 2010).

Apart from the VEGFRs, most VEGFs bind to co-receptors, which stabilize the VEGF/VEGFR interaction and increase the effective growth factor concentration on the cell surface, for example, neuropilins (Grunewald et al., 2010), integrins (Soldi et al., 1999), or syndecans (Johns et al., 2016). However, these interactions are typically of lower affinity than the VEGF/VEGFR interaction (Soker et al., 2002).

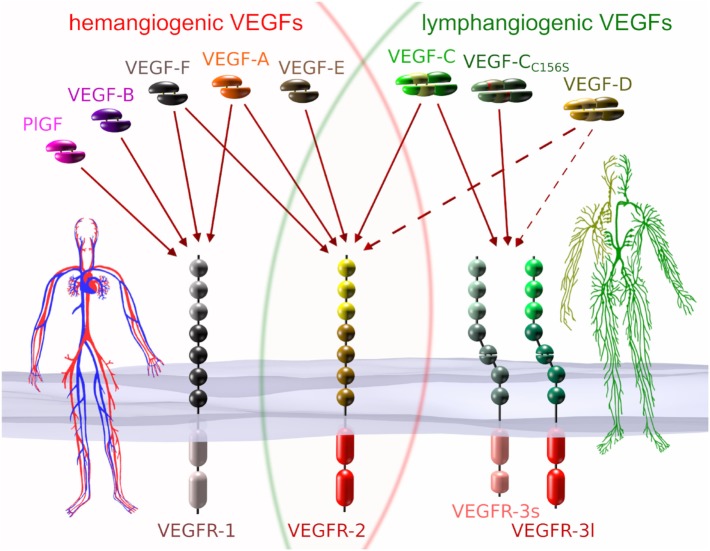

In humans, five different genes encode VEGF family members: VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC, VEGFD, and PGF (placenta growth factor), respectively. Each VEGF can be roughly categorized as being hemangiogenic (VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF-B) or lymphangiogenic (VEGF-C and VEGF-D). Unique to the hemangiogenic VEGFs is their interaction with VEGFR-1, while only members of the lymphangiogenic group do interact with VEGFR-3. VEGFR-2, which is the receptor that drives proliferation and migration of BECs, can be activated by some but not all members from both groups (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

VEGFs and VEGF receptors (VEGFRs). Each of the five mammalian VEGFs [PlGF, VEGF-A to -D], the viral VEGF-E, and the snake venom VEGF-F interacts specifically with a certain subset of the three VEGFRs. VEGF-CC156S is an engineered vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) variant that interacts predominantly with VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) (Joukov et al., 1998). VEGFs that interact with all three receptors do not naturally exist, but have been engineered (Jeltsch et al., 2006). VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1) and VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) are expressed on blood vascular endothelial cells (BECs), while VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 are expressed on lymphatic endothelial cells. VEGFR-3 is the primary mitogenic receptor for lymphatic endothelium, while VEGFR-2 is the primary mitogenic receptor for blood vascular endothelium. Exclusive to higher primates is the appearance of a short splice isoform of VEGFR-3 (VEGFR-3s) (Pajusola et al., 1993; Borg et al., 1995; Hughes, 2001). Signaling pathways activated by VEGFR-3s are partially distinct from those activated by the long splice isoform (VEGFR-3l), since it lacks some of the phosphorylation sites required for mediator docking (e.g., for Shc-Grb2) (Fournier et al., 1995; Dixelius et al., 2003). The dotted arrows from VEGF-D indicate heterogeneous binding patterns. While mature human VEGF-D can activate VEGFR-2, this seems not to be the case for mouse VEGF-D (Baldwin et al., 2001), and consequently, VEGF-D function could have diverged since the evolutionary divide some 60–65 million years ago (O’Leary et al., 2013). Additionally, human VEGF-D can selectively lose its affinity for VEGFR-3 after proteolytic processing (Leppanen et al., 2011).

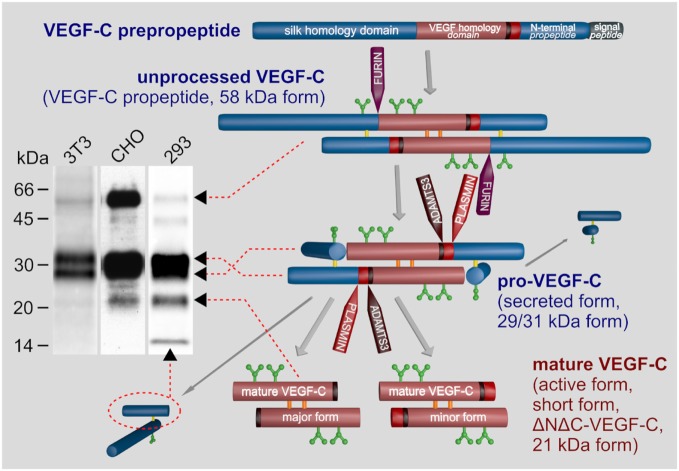

All VEGF family members are characterized by the central VEGF homology domain (VHD, aka PDGF/VEGF domain) (EMBL-EBI, 2017). The VHD contains the receptor binding domain and features a pattern of characteristically spaced cysteine residues, which gives rise to a cystine knot (Holmes and Zachary, 2005). In addition to the VHD, most VEGFs feature accessory sequences that further delineate the specific properties of individual VEGFs: the affinity of, e.g., VEGF-A to the co-receptors neuropilin-1 and -2 (NP-1 and NP-2) (Neufeld et al., 2002), or of VEGF-C to the co-receptor NP-2 (Karpanen et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2010), heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (Johns et al., 2016), and to the extracellular matrix (Jha et al., 2017). In VEGF-C and VEGF-D, the N- and C-terminal accessory sequences are exceptionally long and function as propeptides, which fold into own domains (see Figure 2) and need to be removed for activation by two proteolytic cleavages.

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis and activation of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C). VEGF-C is produced as an inactive propeptide. Proprotein convertases such as furin, PC5, or PC7 cleave between the VEGF homology domain and the C-terminal silk homology domain resulting in pro-VEGF-C. The silk homology domain is not removed by this cleavage, but remains covalently connected via cysteine bridges to the rest of pro-VEGF-C (Joukov et al., 1997b). Pro-VEGF-C is able to bind VEGFR-3, but does not activate it (Jeltsch et al., 2014). The second proteolytic cleavage by A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3 (ADAMTS3) removes both terminal domains resulting in mature, active VEGF-C. Cleavage by ADAMTS3 results in the major form of the mature VEGF-C, which is nine amino acids shorter compared to the minor form, which is likely a product of plasmin cleavage (Joukov et al., 1998; Baldwin et al., 2001; Jeltsch et al., 2014). Three N-glycosylation sites are found in VEGF-C (shown in green). Alternative names for different VEGF-C forms are given in brackets. The band pattern of VEGF-C produced from a full-length cDNA resolved by SDS-PAGE depends on the expressing cell line, expression levels and the antibody used for immunoprecipitation and/or Western blotting. 3T3 fibroblasts produce almost exclusively pro-VEGF-C. In high-level-expressing CHO cells, a significant fraction of the secreted protein can remain unprocessed. Among the most efficiently processing cells are 293 cells, but pro-VEGF-C still represents the majority of the VEGF-C protein.

While only five genes encode the mammalian VEGFs, the actual number of different VEGFs is much larger. Within the hemangiogenic VEGFs, functional diversity is generated mostly by alternative splicing, resulting in differences in the affinity for HSPGs (“heparin affinity”) (Robinson and Stringer, 2001). For VEGF-C, no functions have been assigned yet to the described alternative splice variants (Lee et al., 1996; Ensembl, 2016).

The Lymphangiogenic VEGFs

Vascular endothelial growth factor C was discovered more than 20 years ago as a binding partner of VEGFR-3 from the cell culture supernatant of the human prostate cancer cell line PC3 (Joukov et al., 1996). In the same year, also murine VEGF-C was described and initially named VRP (VEGF-related protein) (Lee et al., 1996). The specific lymphangiogenic properties of VEGF-C were demonstrated in various animal models (Jeltsch et al., 1997; Oh et al., 1997). VEGF-D is the second member of the lymphangiogenic VEGF subgroup. It was discovered independently by three research teams and named once FIGF (c-fos-induced growth factor) (Orlandini et al., 1996) and twice VEGF-D (Yamada et al., 1997; Achen et al., 1998). Both VEGF-C and VEGF-D use posttranslational modification by proteolytic cleavage to generate molecular species diversity (Joukov et al., 1997b; Stacker et al., 1999), but the proteases are different (Bui et al., 2016). While VEGF-D shares many similarities with VEGF-C, it cannot replace VEGF-C (see the VEGF-D paragraph).

Different VEGF-C Forms, the VEGF-CC156S Mutant and Angiogenic “Side Effects”

The most prominent differences between the different VEGF-C forms are the affinities for the receptors, co-receptors, and the extracellular matrix. With increasing processing (see Figure 2), VEGF-C’s affinity for both VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 increases, and fully processed mature VEGF-C is therefore not only lymphangiogenic but also angiogenic (Joukov et al., 1997a; Anisimov et al., 2009) and induces the permeability of blood vessels (Joukov et al., 1997b). To identify which functions of VEGF-C are mediated by which receptor (VEGFR-2 versus VEGFR-3), the VEGF-CC156S mutant was developed (Joukov et al., 1998) (commercially available from R&D systems as 752-VC or its rat homolog from Reliatech as R20-016). This mutant largely lacks VEGFR-2 affinity and can therefore be used to exclude VEGF-C effects on the blood vasculature (Veikkola et al., 2001). However, despite its dual receptor binding, the effect of wild type VEGF-C on the blood vasculature is minimal in many models, and recent data suggest that the localization of pro-VEGF-C on LEC surfaces prior to activation could explain this specificity (Jha et al., 2017). Most reports that attribute a prominent angiogenic effect to VEGF-C have investigated prenatal development (Oh et al., 1997; Lohela et al., 2008) or used VEGF-C forms lacking the propeptides (Oh et al., 1997; Cao et al., 1998; Sweat et al., 2014). The propeptides keep VEGF-C inactive (Joukov et al., 1997b), are required for localizing VEGF-C (Jha et al., 2017), and are removed by sequential proteolysis by furin (Siegfried et al., 2003) and A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3 (ADAMTS3) (Jeltsch et al., 2014) or plasmin (McColl et al., 2003).

The relationship between affinity and receptor activation is not straightforward: pro-VEGF-C is able to bind VEGFR-3 under cooperation of NP-2 without any detectable receptor activation. In fact, it is even a competitive inhibitor of mature VEGF-C for VEGFR-3 activation (Jeltsch et al., 2014).

VEGF-D

VEGF-D is the closest paralog of VEGF-C (Achen et al., 1998). The angiogenic potential of mature VEGF-D has been shown to be stronger compared to mature VEGF-C (Rissanen et al., 2003), which is explained by the fact that maximally processed VEGF-D exclusively binds to VEGFR-2, while VEGF-C retains in its maximally processed form the capacity to bind VEGFR-3 (Leppanen et al., 2011). It is differently activated than VEGF-C (Bui et al., 2016), and because the proteolytic environment is difficult to predict and control, the use of VEGF-D for LEC stimulation remains problematic. Moreover, Vegfd gene-deleted mice have no lymphatic phenotype arguing for no major role in the development of the murine lymphatic system (Baldwin et al., 2005).

Requirement for Collagen and Calcium Binding EGF Domains 1 (CCBE1) AND ADAMTS3

The two molecules that are required for the proteolytic activation of VEGF-C are the CCBE1 protein and the ADAMTS3 protease. ADAMTS3 catalyzes the final step in the proteolytic processing of VEGF-C, removing the N-terminal propeptide and releasing the fully active, mature VEGF-C (Jeltsch et al., 2014; see Figure 2). In vitro, large amounts of ADAMTS3 are able to activate pro-VEGF-C, but in vivo, ADAMTS3 requires the assistance of CCBE1 for the efficient activation of VEGF-C. CCBE1 enhances the VEGF-C activation by two different mechanisms: it increases the processivity of the ADAMTS3 enzyme (Roukens et al., 2015) and it colocalizes VEGF-C and ADAMTS3 on cell surfaces and ECM to form the trimeric activation complex (Bui et al., 2016; Jha et al., 2017). Similar to Vegfc, the genetic ablation of either Ccbe1 or Adamts3 in mice results in a general halt of lymphatic development (Bos et al., 2011; Hagerling et al., 2013; Janssen et al., 2015).

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3 cleavage results in the so-called “major” form of mature VEGF-C (Joukov et al., 1998; Jeltsch et al., 2014). The so-called “minor” form is nine amino acids longer at its N-terminus and is presumably generated by plasmin. Plasmin might activate VEGF-C during wound healing and inflammatory processes (McColl et al., 2003), where it could rapidly release large amounts of active VEGF-C from matrix-bound, “latent” pro-VEGF-C. However, it is still unclear, whether there is any difference between the lymphangiogenesis response to the “major” and “minor” forms of mature VEGF-C.

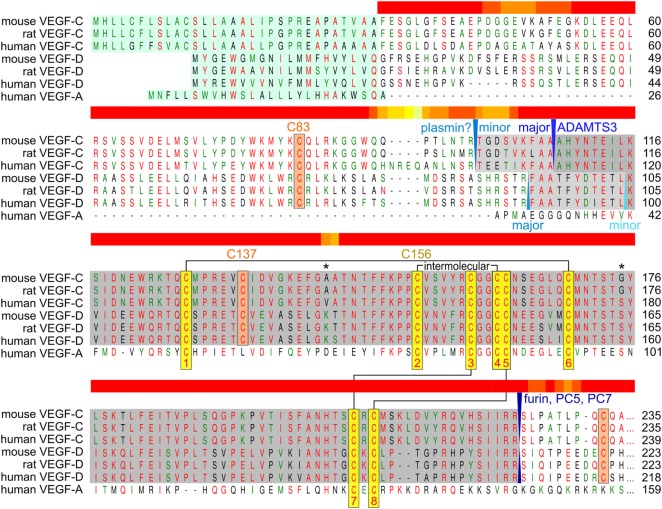

To bypass the complex proteolytic maturation of VEGF-C, the recombinant production of mature VEGF-C is almost exclusively done from a truncated cDNA. However, this is not without problems, since VEGF-C contains in its VHD—as opposed to VEGF-A—an extra cysteine residue (Cys 137), which interferes with intermolecular disulfide bond formation (Chiu et al., 2014) and protein stability (Anisimov et al., 2009; Leppanen et al., 2011) (see Figure 3). It has been proposed that when produced from a full-length cDNA, cysteine residues from the VEGF-C propeptides could protect Cys 137 and thus facilitate correct disulfide bond formation in the VHD.

Figure 3.

Alignment of human, mouse, and rat vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C)/D with human VEGF-A. The sequences of the active, mature VEGF-C/D are boxed gray. Proteolytic cleavage sites and enzymes (if known) are indicated in blue colors. The signal peptide is boxed green. The eight conserved cysteines of the PDGF/VEGF signature (Muller et al., 1997) are boxed yellow and intra- and intermolecular disulfide bridges are indicated by black connecting lines. VEGF-C/D-specific conserved cysteine residues are boxed in orange. The two asterisks denote the only two amino acid residues that are different between fully processed mouse and human VEGF-C. Cysteine 156, which is mutated to serine in the VEGFR-3-monospecific variant VEGF-CC156S, participates in the intermolecular cystine bridge (Joukov et al., 1998). When mature VEGF-C is produced from a truncated cDNA, the single cysteine 137 remains unpaired decreasing protein stability (Anisimov et al., 2009; Leppanen et al., 2011). When pairing with cysteine 156, cysteine 137 interferes with intermolecular disulfide bond formation and protein folding, explaining the observation of significant amounts of single-linked dimers, non-covalent VEGF-C dimers and VEGF-C monomers (Joukov et al., 1996; Jeltsch et al., 2006; Chiu et al., 2014). Above the alignment, a heat map indicates the areas of highest divergence, deduced from a more comprehensive alignment of VEGF-A, -C, and -D. The C-terminal domains of VEGF-C/D are not shown.

The Enigmatic “Silk Homology” Domain

Very intriguing is the repetitive arrangement of cysteine residues (CX10CXCXC) in the C-terminal propeptide of VEGF-C. This signature is unique within vertebrate proteins, and its phylogenetic origin remains unknown. Except in VEGF-C, it occurs, e.g., in the balbiani ring protein 3 and salivary proteins of silk weaving mosquito larvae of the genus Chironomus (Dignam and Case, 1990). Therefore, the term “silk homology domain” was coined to describe the C-terminal propeptide (Joukov et al., 1996). In addition to regulating the activity of VEGF-C, this domain endows the molecule with most of its heparin affinity (Johns et al., 2016), and it is the determining factor for the ECM sequestration of VEGF-C (Jha et al., 2017). Interestingly, sequestration and proteolysis-mediated release of active VEGF-C have also been reverse engineered by concatenating a fibrin-binding (FB) and a MMP-degradable polypeptide sequence N-terminally to the mature VEGF-C sequence (Güç et al., 2017). This protein (FB-VEGF-C) compared favorably to mature VEGF-C in the local induction of lymphangiogenesis, but native sequestration of wild-type VEGF-C expressed from a full-length cDNA was not included in this comparison.

Regulation of VEGF-C Signaling

Compared to VEGF-A, not much is known about the regulation of VEGF-C expression in vivo. The fact that VEGF-C is produced as an inactive precursor (pro-VEGF-C) indicates that much of its regulation happens after its constitutive secretion at the level of proteolytic activation. However, while the activation mechanism itself has been studied extensively (Jeltsch et al., 2014; Roukens et al., 2015; Bui et al., 2016; Jha et al., 2017), virtually nothing is known about the regulation of the obligatory protease ADAMTS3 and its cofactor CCBE1.

In the adult organism, inflammation potently upregulates VEGF-C expression, most notably by macrophages (Ristimäki et al., 1998; Baluk et al., 2005; Krebs et al., 2012), resulting in a negative feedback loop (Zhou et al., 2011; Christiansen et al., 2016) promoting resolution in some models, while aggravating the situation in others (Kim et al., 2014).

The interstitial pressure that builds up during development in blood-vascularized but lymphatic-free tissues leads via β1-integrin-mediated mechanoinduction to enhanced VEGFR-3 phosphorylation (Planas-Paz et al., 2012). However, it remains unclear, whether meaningful VEGFR-3 phosphorylation can happen in vivo entirely without ligand, although the kinase activity of VEGFR-3 is dispensable in vitro (Galvagni et al., 2010). In any case, the interplay of mechanical forces with growth factor signaling for the establishment of functional lymphatic networks has been shown in many systems (Sabine et al., 2016). Binding of mature VEGF-C to VEGFR-3 results in the activation of both the MAPK/ERK and AKT intracellular signaling pathways (Mäkinen et al., 2001; Deng et al., 2015), which promote survival, growth, and migration in LECs (Mäkinen et al., 2001).

VEGF-C Signaling in Embryonic Development

VEGF receptor 3 was discovered before VEGF-C and VEGF-D, and therefore, VEGFR-3 was between 1992 and 1996 an “orphan receptor”, i.e., a receptor without known ligand. However, soon after the discovery of VEGFR-3, the specific expression pattern of VEGFR-3 suggested that its function was closely related to the lymphatic system. In the early stages of embryonic development, all endothelial cells express VEGFR-3, but its expression becomes progressively restricted to LECs (Kaipainen et al., 1995). Finally, VEGFR-3 expression becomes sufficiently specific for LECs that it has been used to identify LECs (Petrova et al., 2008), despite the existence of other VEGFR-3 expressing endothelial cells, e.g., angiogenic, sinusoidal, and fenestrated BECs.

The pivotal role of the VEGFR-3 ligand VEGF-C in the establishment of the lymphatic vasculature is witnessed by the fact that mice devoid of VEGF-C do not develop any lymphatic structures and form generalized edema from E12.5, resulting in embryonic death around E16.5 (Karkkainen et al., 2004).

Interestingly, mice devoid of the VEGF-C receptor VEGFR-3 die already around E9.5, before the first lymphatic structures develop, from failures in the organization and maturation of blood vessels (Dumont et al., 1998). However, embryonic lethality after deletion of both VEGFR-3 ligands, VEGF-C and VEGF-D, occurs only around E16.5, suggesting no role of these ligands for VEGFR-3 activation in early embryogenesis (Haiko et al., 2008). Since VEGFR-3 can form heterodimers with VEGFR-2, this might be a substitute mechanism for VEGFR-3 activation (Dixelius et al., 2003; Nilsson et al., 2010). Alternatively, ligandless baseline signaling (Zhang et al., 2005; Galvagni et al., 2010), mechanoinduction (Planas-Paz et al., 2012), or unrecognized ligands might provide a sufficient stimulus. Interestingly, neither the development of the blood vascular system nor of the lymphatic vascular system is affected by the lack of the second lymphangiogenic growth factor VEGF-D (Baldwin et al., 2005).

Genetic Lesions in the VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 Signaling Pathway

So far, mutations in 27 genes have been found to cause human lymphedema conditions. Several of these mutations affect components of the VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signaling pathway (Table 1). Interestingly, a major fraction of hereditary lymphedema patients present with mutations in VEGFR-3, while mutations in the other genes are relatively rare (Brouillard et al., 2014, 2017).

Table 1.

Hereditary human lymphedema conditions involving the vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C)/VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) signaling pathway.

| GENE (protein) | Human condition (OMIM, alternative name) | Lymphedema phenotype | Reference for the initial linkage | Molecular etiology | Viable animal models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLT4 (VEGFR-3) | Hereditary lymphedema type 1A (153100, Milroy disease) | Predominantly the lower extremities | Irrthum et al. (2000), Karkkainen et al. (2000) | Dominant negative inactivation of the intracellular kinase domain (Irrthum et al., 2000; Karkkainen et al., 2000) | Chy mice (inactivating Flt4 mutation) (Karkkainen et al., 2001b); VEGFR-3 inhibition (Mäkinen et al., 2001) |

| VEGFC (VEGF-C) | Hereditary lymphedema type 1D (615907, Milroy-like disease) | Gordon et al. (2013), Balboa-Beltran et al. (2014) | Secretion defect (Gordon et al., 2013; Villefranc et al., 2013) | Chy-3 mice (hemizygous Vegfc deletion) (Dellinger et al., 2007); conditional Vegfc ko mice (Nurmi et al., 2015) | |

| CCBE1 (Collagen and calcium-binding EGF domain-containing protein 1) | Hennekam syndrome type 1 (235510) |

Generalized | Alders et al. (2009) | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3 activation defect (Jeltsch et al., 2014; Roukens et al., 2015), localization defect (Jha et al., 2017) | Conditional Ccbe1 ko mice (Bui et al., 2016) |

| Cholestasis–lymphedema syndrome (214900, Aagenaes syndrome) | Shah et al. (2013), Viveiros et al. (2017) | ||||

| FAT4 (Protocadherin Fat4) | Hennekam syndrome type 2 (616006) |

Alders et al. (2014) | Unknown molecular etiology | Vascular abnormalities were not reported for the full Fat4 ko mice (Saburi et al., 2008) | |

| Van Maldergem syndrome type 2 (615546) | |||||

| ADAMTS3 (A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 3) | Hennekam syndrome type 3 | Brouillard et al. (2017) | Secretion defect (Brouillard et al., 2017), localization defect (Jha et al., 2017) | Conditional Adamts3 ko mice (Bui et al., 2016) | |

Although in hereditary lymphedema type 1A and 1D, all cells carry the mutant VEGFR-3 or VEGF-C gene, not all lymphatic vessels and body parts are equally affected. Hypoplastic or aplastic lymph capillaries are mainly found in peripheral, superficial regions (Bollinger et al., 1983). However, in addition to the underdeveloped lymphatic structures, a functional deficit seems to play a variable, but significant role in the manifestation of the edema (Mellor et al., 2010). A higher hydrostatic pressure resulting in increased drainage needs in the extremities could possibly explain localized symptoms. However, leg edema is as well observed in mice and newborns, where hydrostatic pressure differences are negligible (Karkkainen et al., 2001a). Alternatively, LECs from different vascular beds could have a different sensitivity for VEGFR-3 signaling, perhaps due to a different developmental origin.

LEC Culture and VEGF-C Signaling

During embryonic growth, signaling by VEGF-C is necessary for the establishment of the lymphatic vasculature (Karkkainen et al., 2004). In the adult organism, the dependency on VEGF-C is less pronounced, and ablation of VEGF-C in the adult organism appears well tolerated also over longer periods of time, except for the intestinal lymphatics (the lacteals) and meningeal lymphatics, which depend on a steady supply with VEGF-C (Nurmi et al., 2015; Antila et al., 2017). It is not known, whether this difference is due to the higher stress or increased turnover of intestinal LECs compared to, e.g., adult skin LECs, which are mostly in the resting phase (Alexander et al., 2010). Despite the apparent VEGF-C requirements for proliferating LECs in vivo, LEC vendors specifically endorse only the use of the hemangiogenic VEGF-A for LEC culture. However, some researchers have modified such media to contain VEGF-C (Mäkinen et al., 2001; Petrova et al., 2002; Podgrabinska et al., 2002; Veikkola et al., 2003). While serum does typically contain VEGF-C in the single digit ng/ml-range (R&D Systems, 2017), serum-supplemented LEC culture medium would still contain only small amounts of VEGF-C compared to VEGF-A, which stimulates VEGFR-2, but not VEGFR-3. While VEGF-A stimulates LEC proliferation and lymphatic vessel dilation in vitro (Dellinger and Brekken, 2011) and increases the density of lymphatic in vitro capillary networks (Marino et al., 2014) to a similar degree as VEGF-C, its importance for in vivo LEC proliferation is arguable as only very few in vivo models of VEGF-A application seem to directly affect lymphatic networks (Shin et al., 2008). While VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 activation both result in PKC-dependent Akt phosphorylation, the activation routes and kinetics differ (Mäkinen et al., 2001). Importantly, SOX18 and KLF4, which are implicated in LEC differentiation (Francois et al., 2008; Park et al., 2014), are specifically regulated by VEGFR-3 (Dieterich et al., 2017).

The specific form of VEGF-C that is used for LEC culture supplementation is the active, mature form, but pro-VEGF-C also might be an attractive option, since the LEC-expressed ADAMTS3 and CCBE1 (Jha et al., 2017) would concertedly convert it into the mature form, providing a differently localized and perhaps more sustained stimulus. Due to its potent synergistic effect with VEGF-C, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) also needs consideration as a LEC culture additive (Kajiya et al., 2005; Gibot et al., 2016).

When VEGF-C is Not Enough

While in some models, the angiogenic component of VEGF-C can be exposed (e.g., in the heart) (Losordo et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2014), VEGF-C predominantly affects the lymphatic system. Not surprisingly, most therapeutic applications of VEGF-C are targeting the lymphatics (Tammela et al., 2007; Honkonen et al., 2013; Klotz et al., 2015), and VEGF-C should therefore be considered the primary growth factor of choice in lymphatic engineering tasks that involve LECs. While necessary, VEGF-C alone is not sufficient for the successful establishment of a functional lymphatic network in some situations (Goldman et al., 2005), and blocking signals that inhibit lymphangiogenesis such as TGF-β1 (Avraham et al., 2010) might be necessary. An elegant way bypassing the need for VEGF-C supplementation is the coculture of LECs with other cell types. In addition to secreted factors, cell–cell contacts appear important for the establishment of lymphatic networks. In one model, lymphangiogenesis was sustained by fibroblast-derived VEGF-C and HGF. While VEGF-C appeared to be constitutively expressed by fibroblasts, HGF expression was induced only in the cocultures (Gibot et al., 2016). Whether the fibroblasts were also able to stimulate the release of Reelin from the LECs was not analyzed in this model. Reelin release from LECs is normally induced by smooth muscle cell contacts and is required for the establishment of collecting vessels (Lutter et al., 2012). In another coculture model, LECs, BECs, and adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs) in a 3D fibrin matrix depended on the addition of exogenous VEGF-C for substantial LEC network formation in addition to cell–cell contacts between LECs and ASCs (Knezevic et al., 2017). In the same model, BEC network formation was not affected by the absence of exogenous VEGF-C.

Directing Regenerative Lymphatic Growth In Vivo

The mechanisms of the directional growth are similar for blood vessels and nerve cell axons (Carmeliet, 2003): a specialized cell on the tip of the vascular sprout (tip cell) determines the direction of growth of subsequent cells (stalk cells) by extending filopodia with growth factor receptors (Gerhardt et al., 2003). However, in vivo evidence for the importance of VEGF gradients for the directed growth of vascular networks is sparse (Ruhrberg et al., 2002), and also in vitro, convincing evidence is largely absent (Bautch, 2012). Likewise, filopodia seems to be dispensable for vascular patterning (Wacker et al., 2014). In the expansion of lymphatic networks, similar directed sprouting can be observed, but e.g. in the mouse tail lymphedema model, the mere application of VEGF-C was not enough to induce sprouting lymphangiogenesis (Goldman et al., 2005). Moreover, and contrary to expectations, VEGF-C levels correlated even in some models with lymphedema formation, apparently via inducing vascular leakage and immune cell infiltration (Gousopoulos et al., 2017). Surgical grafting of engineered small lymphatic structures is difficult unless they are grafted as part of a larger tissue (e.g., a vascularized skin graft). Hence, the idea of generating lymphatics in situ is attractive and indeed has been successfully achieved in some animal models using different delivery strategies for VEGF-C (Karkkainen et al., 2001b; Szuba et al., 2002; Yoon et al., 2003). The question whether VEGF-C alone is enough (Breier, 2005; Goldman et al., 2005) has recently at least received a partial answer by the discovery of obligatory cofactors such as CCBE1 and ADAMTS3 for correct VEGF-C localization and efficient activation (Jeltsch et al., 2014; Jha et al., 2017), and the presence or absence of these factors might explain differences in the lymphatic response. After encouraging preclinical studies (Tammela et al., 2007), the therapeutic value of VEGF-C for an improved integration of transplanted lymph nodes into the regional lymph system is currently under investigation (Tervala et al., 2015). It is less obvious how large collecting lymphatics could be generated in situ, but flow-stimulated remodeling of smaller lymphatics might happen akin to the hemodynamic remodeling of blood vessels (Culver and Dickinson, 2010).

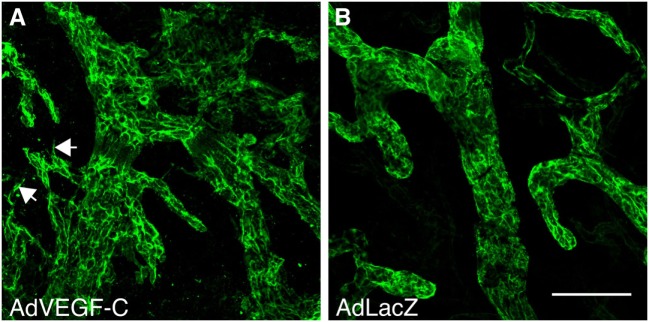

Although preclinical experience with in situ reconstitution of lymphatic networks using VEGF-C exists for more than 15 years, there is only one ongoing phase I clinical trial using VEGF-C therapy, namely the application of a VEGF-C-expressing adenovirus (AdVEGF-C, see Figure 4), in combination with lymph node transplantation for the treatment of secondary lymphedema after breast cancer surgery. The slow adoption might partly result from animal studies that identify VEGF-C as a key inducer for the growth and dissemination of certain tumors (for references, see Figure 5). While it is prudent to take the complete picture of VEGF-C biology as shown in Figure 5 into consideration when reconstructing lymphatics, the localized and limited availability of VEGF-C in this specific ongoing phase I study should exclude tumor-promoting side effects, paving the way for phase II studies.

Figure 4.

Vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) induces specifically the growth of the lymphatic vasculature. Whole-mount LYVE-1 staining of mouse ears 2 weeks after adenoviral transduction with VEGF-C (A) and LacZ (B). AdVEGF-C induces hyperplasia of and neo-sprouting from the lymphatic vasculature. Arrows indicate lymphatic sprouting. Bar, 100 µm.

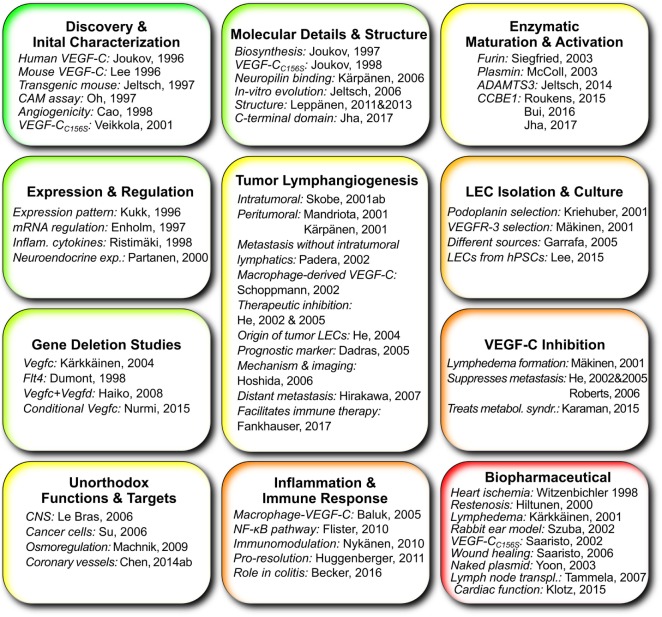

Figure 5.

Works that give important insights into vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and its function grouped according to topic. Publications about the use of VEGF-C specifically in lymphatic tissue engineering are not included since this list tries to highlight the elemental scientific insights on which tissue engineering can build.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sinem Karaman for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (award numbers 304042, 303778, 273612, and 265982), the K. Albin Johansson, and the Magnus Ehrnrooth Foundation. The ILS doctoral program, University of Helsinki supported the salary of SKJ.

References

- Achen M. G., Jeltsch M., Kukk E., Mäkinen T., Vitali A., Wilks A. F., et al. (1998). Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) is a ligand for the tyrosine kinases VEGF receptor 2 (Flk1) and VEGF receptor 3 (Flt4). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 548–553. 10.1073/pnas.95.2.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alders M., Al-Gazali L., Cordeiro I., Dallapiccola B., Garavelli L., Tuysuz B., et al. (2014). Hennekam syndrome can be caused by FAT4 mutations and be allelic to Van Maldergem syndrome. Hum. Genet. 133, 1161–1167. 10.1007/s00439-014-1456-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alders M., Hogan B. M., Gjini E., Salehi F., Al-Gazali L., Hennekam E. A., et al. (2009). Mutations in CCBE1 cause generalized lymph vessel dysplasia in humans. Nat. Genet. 41, 1272–1274. 10.1038/ng.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J. S., Ganta V. C., Jordan P. A., Witte M. H. (2010). Gastrointestinal lymphatics in health and disease. Pathophysiology 17, 315–335. 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimov A., Alitalo A., Korpisalo P., Soronen J., Kaijalainen S., Leppänen V.-M., et al. (2009). Activated forms of VEGF-C and VEGF-D provide improved vascular function in skeletal muscle. Circ. Res. 104, 1302–1312. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antila S., Karaman S., Nurmi H., Airavaara M., Voutilainen M. H., Mathivet T., et al. (2017). Development and plasticity of meningeal lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3645–3667. 10.1084/jem.20170391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham T., Daluvoy S., Zampell J., Yan A., Haviv Y. S., Rockson S. G., et al. (2010). Blockade of transforming growth factor-β1 accelerates lymphatic regeneration during wound repair. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 3202–3214. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balboa-Beltran E., Fernández-Seara M. J., Pérez-Muñuzuri A., Lago R., García-Magán C., Couce M. L., et al. (2014). A novel stop mutation in the vascular endothelial growth factor-C gene (VEGFC) results in Milroy-like disease. J. Med. Genet. 51, 475–478. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin M. E., Catimel B., Nice E. C., Roufail S., Hall N. E., Stenvers K. L., et al. (2001). The specificity of receptor binding by vascular endothelial growth factor-D is different in mouse and man. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19166–19171. 10.1074/jbc.M100097200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin M. E., Halford M. M., Roufail S., Williams R. A., Hibbs M. L., Grail D., et al. (2005). vascular endothelial growth factor D is dispensable for development of the lymphatic system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2441–2449. 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2441-2449.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluk P., Tammela T., Ator E., Lyubynska N., Achen M. G., Hicklin D. J., et al. (2005). Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 247–257. 10.1172/JCI200522037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautch V. L. (2012). VEGF-directed blood vessel patterning: from cells to organism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006452. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautch V. L., Caron K. M. (2015). Blood and lymphatic vessel formation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a008268. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger A., Isenring G., Franzeck U. K., Brunner U. (1983). Aplasia of superficial lymphatic capillaries in hereditary and connatal lymphedema (Milroy’s disease). Lymphology 16, 27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J. P., deLapeyrière O., Noguchi T., Rottapel R., Dubreuil P., Birnbaum D. (1995). Biochemical characterization of two isoforms of FLT4, a VEGF receptor-related tyrosine kinase. Oncogene 10, 973–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos F. L., Caunt M., Peterson-Maduro J., Planas-Paz L., Kowalski J., Karpanen T., et al. (2011). CCBE1 is essential for mammalian lymphatic vascular development and enhances the lymphangiogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-C in vivo. Circ. Res. 109, 486–491. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.250738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier G. (2005). Lymphangiogenesis in regenerating tissue: is VEGF-C sufficient? Circ. Res. 96, 1132–1134. 10.1161/01.RES.0000170976.63688.ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillard P., Boon L., Vikkula M. (2014). Genetics of lymphatic anomalies. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 898–904. 10.1172/JCI71614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillard P., Dupont L., Helaers R., Coulie R., Tiller G. E., Peeden J., et al. (2017). Loss of ADAMTS3 activity causes Hennekam lymphangiectasia–lymphedema syndrome 3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 4095–4104. 10.1093/hmg/ddx297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui H. M., Enis D., Robciuc M. R., Nurmi H. J., Cohen J., Chen M., et al. (2016). Proteolytic activation defines distinct lymphangiogenic mechanisms for VEGFC and VEGFD. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 2167–2180. 10.1172/JCI83967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. G., Isogai S., Weinstein B. M. (2009). Lymphatic development. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 87, 222–231. 10.1002/bdrc.20155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Linden P., Farnebo J., Cao R., Eriksson A., Kumar V., et al. (1998). Vascular endothelial growth factor C induces angiogenesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14389–14394. 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. (2003). Blood vessels and nerves: common signals, pathways and diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, nrg1158. 10.1038/nrg1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. I., Sharma B., Akerberg B. N., Numi H. J., Kivelä R., Saharinen P., et al. (2014). The sinus venosus contributes to coronary vasculature through VEGFC-stimulated angiogenesis. Development 141, 4500–4512. 10.1242/dev.113639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J., Wong J.W. H., Gerometta M., Hogg P. J. (2014). Mechanism of dimerization of a recombinant mature vascular endothelial growth factor C. Biochemistry 53, 7–9. 10.1021/bi401518b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen A. J., Dieterich L. C., Ohs I., Bachmann S. B., Bianchi R., Proulx S. T., et al. (2016). Lymphatic endothelial cells attenuate inflammation via suppression of dendritic cell maturation. Oncotarget 7, 39421–39435. 10.18632/oncotarget.9820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J. C., Dickinson M. E. (2010). The effects of hemodynamic force on embryonic development. Microcirculation 1994, 164–178. 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00025.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai T.t, Jiang Z.h, Li S. I., Zhou Gd, Kretlow J. D., Cao Wg, et al. (2010). Reconstruction of lymph vessel by lymphatic endothelial cells combined with polyglycolic acid scaffolds: a pilot study. J. Biotechnol. 150, 182–189. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger M. T., Brekken R. A. (2011). Phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 is required for VEGF-A/VEGFR2-induced proliferation and migration of lymphatic endothelium. PLoS ONE 6:e28947. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger M. T., Hunter R. J., Bernas M. J., Witte M. H., Erickson R. P. (2007). Chy-3 mice are Vegfc haploinsufficient and exhibit defective dermal superficial to deep lymphatic transition and dermal lymphatic hypoplasia. Dev. Dyn. 236, 2346–2355. 10.1002/dvdy.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Zhang X., Simons M. (2015). Molecular controls of lymphatic VEGFR3 signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 421–429. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich L. C., Ducoli L., Shin J. W., Detmar M. (2017). Distinct transcriptional responses of lymphatic endothelial cells to VEGFR-3 and VEGFR-2 stimulation. Sci. Data 4, 170106. 10.1038/sdata.2017.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam S. S., Case S. T. (1990). Balbiani ring 3 in Chironomus tentans encodes a 185-kDa secretory protein which is synthesized throughout the fourth larval instar. Gene 88, 133–140. 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90024-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixelius J., Mäkinen T., Wirzenius M., Karkkainen M. J., Wernstedt C., Alitalo K., et al. (2003). Ligand-induced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR-3) heterodimerization with VEGFR-2 in primary lymphatic endothelial cells regulates tyrosine phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40973–40979. 10.1074/jbc.M304499200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont D. J., Jussila L., Taipale J., Lymboussaki A., Mustonen T., Pajusola K., et al. (1998). Cardiovascular failure in mouse embryos deficient in VEGF Receptor-3. Science 282, 946–949. 10.1126/science.282.5390.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMBL-EBI. (2017). PDGF/VEGF Domain (IPR000072) < InterPro < EMBL-EBI. Available at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/IPR000072

- Ensembl. (2016). Transcript: Vegfc-203 (ENSMUST00000210831.1) – Protein Sequence – Mus musculus – Ensembl Genome Browser 90. Available at: https://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/Transcript/Sequence_Protein?db=core;g=ENSMUSG00000031520;r=8:54077606-54187096;t=ENSMUST00000210831

- Fournier E., Dubreuil P., Birnbaum D., Borg J. P. (1995). Mutation at tyrosine residue 1337 abrogates ligand-dependent transforming capacity of the FLT4 receptor. Oncogene 11, 921–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois M., Caprini A., Hosking B., Orsenigo F., Wilhelm D., Browne C., et al. (2008). Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature 456, 643–647. 10.1038/nature07391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuh G., Li B., Crowley C., Cunningham B., Wells J. A. (1998). Requirements for binding and signaling of the kinase domain receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 11197–11204. 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvagni F., Pennacchini S., Salameh A., Rocchigiani M., Neri F., Orlandini M., et al. (2010). Endothelial cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix induces c-Src–dependent VEGFR-3 phosphorylation without the activation of the receptor intrinsic kinase activity. Circ. Res. 106, 1839–1848. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Golding M., Fruttiger M., Ruhrberg C., Lundkvist A., Abramsson A., et al. (2003). VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J. Cell Biol. 161, 1163–1177. 10.1083/jcb.200302047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibot L., Galbraith T., Bourland J., Rogic A., Skobe M., Auger F. A. (2017). Tissue-engineered 3D human lymphatic microvascular network for in vitro studies of lymphangiogenesis. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1077. 10.1038/nprot.2017.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibot L., Galbraith T., Kloos B., Das S., Lacroix D. A., Auger F. A., et al. (2016). Cell-based approach for 3D reconstruction of lymphatic capillaries in vitro reveals distinct functions of HGF and VEGF-C in lymphangiogenesis. Biomaterials 78, 129–139. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman J., Le T. X., Skobe M., Swartz M. A. (2005). Overexpression of VEGF-C causes transient lymphatic hyperplasia but not increased lymphangiogenesis in regenerating skin. Circ. Res. 96, 1193–1199. 10.1161/01.RES.0000168918.27576.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon K., Schulte D., Brice G., Simpson M. A., Roukens M. G., van Impel A., et al. (2013). Mutation in vascular endothelial growth factor-C, a ligand for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3, is associated with autosomal dominant Milroy-like primary lymphedema. Circ. Res. 112, 956–960. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousopoulos E., Proulx S. T., Bachmann S. B., Dieterich L. C., Scholl J., Karaman S., et al. (2017). An important role of VEGF-C in promoting lymphedema development. J. Invest. Dermatol. 137, 1995–2004. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald F. S., Prota A. E., Giese A., Ballmer-Hofer K. (2010). Structure–function analysis of VEGF receptor activation and the role of coreceptors in angiogenic signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1804, 567–580. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güç E., Briquez P. S., Foretay D., Fankhauser M. A., Hubbell J. A., Kilarski W. W., et al. (2017). Local induction of lymphangiogenesis with engineered fibrin-binding VEGF-C promotes wound healing by increasing immune cell trafficking and matrix remodeling. Biomaterials 131, 160–175. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerling R., Pollmann C., Andreas M., Schmidt C., Nurmi H., Adams R. H., et al. (2013). A novel multistep mechanism for initial lymphangiogenesis in mouse embryos based on ultramicroscopy. EMBO J. 32, 629–644. 10.1038/emboj.2012.340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiko P., Makinen T., Keskitalo S., Taipale J., Karkkainen M. J., Baldwin M. E., et al. (2008). Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and VEGF-D is not equivalent to vegf receptor 3 deletion in mouse embryos. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4843–4850. 10.1128/MCB.02214-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm C.-L. E., Zisch A., Swartz M. A. (2007). Engineered blood and lymphatic capillaries in 3-D VEGF-fibrin-collagen matrices with interstitial flow. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 96, 167–176. 10.1002/bit.21185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D. I., Zachary I. (2005). The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family: angiogenic factors in health and disease. Genome Biol. 6, 209. 10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K., Roberts O. L., Thomas A. M., Cross M. J. (2007). Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cell. Signal. 19, 2003–2012. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkonen K. M., Visuri M. T., Tervala T. V., Halonen P. J., Koivisto M., Lahteenvuo M. T., et al. (2013). Lymph node transfer and perinodal lymphatic growth factor treatment for lymphedema. Ann. Surg. 257, 961–967. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826ed043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. C. (2001). Alternative splicing of the human VEGFGR-3/FLT4 gene as a consequence of an integrated human endogenous retrovirus. J. Mol. Evol. 53, 77–79. 10.1007/s002390010195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irrthum A., Karkkainen M. J., Devriendt K., Alitalo K., Vikkula M. (2000). Congenital hereditary lymphedema caused by a mutation that inactivates VEGFR3 tyrosine kinase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 295–301. 10.1086/303019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen L., Dupont L., Bekhouche M., Noel A., Leduc C., Voz M., et al. (2015). ADAMTS3 activity is mandatory for embryonic lymphangiogenesis and regulates placental angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 19, 53–65. 10.1007/s10456-015-9488-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch M., Jha S. K., Tvorogov D., Anisimov A., Leppänen V.-M., Holopainen T., et al. (2014). CCBE1 enhances lymphangiogenesis via a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs-3–mediated vascular endothelial growth factor-C activation. Circulation 129, 1962–1971. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch M., Kaipainen A., Joukov V., Meng X., Lakso M., Rauvala H., et al. (1997). Hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels in VEGF-C transgenic mice. Science 276, 1423–1425. 10.1126/science.276.5317.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch M., Karpanen T., Strandin T., Aho K., Lankinen H., Alitalo K. (2006). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF-C mosaic molecules reveal specificity determinants and feature novel receptor binding patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12187–12195. 10.1074/jbc.M511593200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S. K., Rauniyar K., Karpanen T., Leppänen V.-M., Brouillard P., Vikkula M., et al. (2017). Efficient activation of the lymphangiogenic growth factor VEGF-C requires the C-terminal domain of VEGF-C and the N-terminal domain of CCBE1. Sci. Rep. 7, 4916. 10.1038/s41598-017-04982-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns S. C., Yin X., Jeltsch M., Bishop J. R., Schuksz M., El Ghazal R., et al. (2016). Functional importance of a proteoglycan coreceptor in pathologic lymphangiogenesis. Circ. Res. 119, 210–221. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Kaipainen A., Jeltsch M., Pajusola K., Olofsson B., Kumar V., et al. (1997a). Vascular endothelial growth factors VEGF-B and VEGF-C. J. Cell. Physiol. 173, 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Sorsa T., Kumar V., Jeltsch M., Claesson-Welsh L., Cao Y., et al. (1997b). Proteolytic processing regulates receptor specificity and activity of VEGF-C. EMBO J. 16, 3898–3911. 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Kumar V., Sorsa T., Arighi E., Weich H., Saksela O., et al. (1998). A recombinant mutant vascular endothelial growth factor-C that has lost vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 binding, activation, and vascular permeability activities. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6599–6602. 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V., Pajusola K., Kaipainen A., Chilov D., Lahtinen I., Kukk E., et al. (1996). A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 15, 290–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaipainen A., Korhonen J., Mustonen T., van Hinsbergh V. W., Fang G. H., Dumont D., et al. (1995). Expression of the fms-like tyrosine kinase 4 gene becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelium during development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3566–3570. 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiya K., Hirakawa S., Ma B., Drinnenberg I., Detmar M. (2005). Hepatocyte growth factor promotes lymphatic vessel formation and function. EMBO J. 24, 2885–2895. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanapathy M., Patel N. M., Kalaskar D. M., Mosahebi A., Mehrara B. J., Seifalian A. M. (2014). Tissue-engineered lymphatic graft for the treatment of lymphedema. J. Surg. Res. 192, 544–554. 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M. J., Ferrell R. E., Lawrence E. C., Kimak M. A., Levinson K. L., McTigue M. A., et al. (2000). Missense mutations interfere with VEGFR-3 signalling in primary lymphoedema. Nat. Genet. 25, 153–159. 10.1038/75997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M. J., Haiko P., Sainio K., Partanen J., Taipale J., Petrova T. V., et al. (2004). Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat. Immunol. 5, 74–80. 10.1038/ni1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M. J., Jussila L., Alitalo K., Ferrell R. E., Finegold D. N. (2001a). Molecular regulation of lymphangiogenesis and targets for tissue oedema. Trends Mol. Med. 7, 18–22. 10.1016/S1471-4914(00)01864-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen M. J., Saaristo A., Jussila L., Karila K. A., Lawrence E. C., Pajusola K., et al. (2001b). A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12677–12682. 10.1073/pnas.221449198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpanen T., Wirzenius M., Mäkinen T., Veikkola T., Haisma H. J., Achen M. G., et al. (2006). Lymphangiogenic growth factor responsiveness is modulated by postnatal lymphatic vessel maturation. Am. J. Pathol. 169, 708–718. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-D., Kang Y., Kim J., Papangeli I., Kang H., Wu J., et al. (2014). Essential role of apelin signaling during lymphatic development in zebrafish. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 338–345. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L., Norman S., Vieira J. M., Masters M., Rohling M., Dubé K. N., et al. (2015). Cardiac lymphatics are heterogeneous in origin and respond to injury. Nature 522, 62–67. 10.1038/nature14483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic L., Schaupper M., Mühleder S., Schimek K., Hasenberg T., Marx U., et al. (2017). Engineering blood and lymphatic microvascular networks in fibrin matrices. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 5, 25. 10.3389/fbioe.2017.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs R., Tikkanen J. M., Ropponen J. O., Jeltsch M., Jokinen J. J., Yla-Herttuala S., et al. (2012). Critical role of VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signaling in innate and adaptive immune responses in experimental obliterative bronchiolitis. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 1607–1620. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Gray A., Yuan J., Luoh S. M., Avraham H., Wood W. I. (1996). Vascular endothelial growth factor-related protein: a ligand and specific activator of the tyrosine kinase receptor Flt4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 1988–1992. 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen V.-M., Jeltsch M., Anisimov A., Tvorogov D., Aho K., Kalkkinen N., et al. (2011). Structural determinants of vascular endothelial growth factor-D receptor binding and specificity. Blood 117, 1507–1515. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohela M., Heloterä H., Haiko P., Dumont D. J., Alitalo K. (2008). Transgenic induction of vascular endothelial growth factor-C is strongly angiogenic in mouse embryos but leads to persistent lymphatic hyperplasia in adult tissues. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1891–1901. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losordo D. W., Vale P. R., Hendel R. C., Milliken C. E., Fortuin F. D., Cummings N., et al. (2002). Phase 1/2 placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-escalating trial of myocardial vascular endothelial growth factor 2 gene transfer by catheter delivery in patients with chronic myocardial ischemia. Circulation 105, 2012–2018. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000015982.70785.B7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter S., Xie S., Tatin F., Makinen T. (2012). Smooth muscle–endothelial cell communication activates Reelin signaling and regulates lymphatic vessel formation. J. Cell Biol. 197, 837–849. 10.1083/jcb.201110132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen T., Veikkola T., Mustjoki S., Karpanen T., Catimel B., Nice E. C., et al. (2001). Isolated lymphatic endothelial cells transduce growth, survival and migratory signals via the VEGF-C/D receptor VEGFR-3. EMBO J. 20, 4762–4773. 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino D., Luginbühl J., Scola S., Meuli M., Reichmann E. (2014). Bioengineering dermo-epidermal skin grafts with blood and lymphatic capillaries. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, ra14–ra221. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl B. K., Baldwin M. E., Roufail S., Freeman C., Moritz R. L., Simpson R. J., et al. (2003). Plasmin activates the lymphangiogenic growth factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D. J. Exp. Med. 198, 863–868. 10.1084/jem.20030361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor R. H., Hubert C. E., Stanton A. W. B., Tate N., Akhras V., Smith A., et al. (2010). Lymphatic dysfunction, not aplasia, underlies Milroy disease. Microcirculation 17, 281–296. 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriondo A., Boschetti F., Bianchin F., Lattanzio S., Marcozzi C., Negrini D. (2010). Tissue contribution to the mechanical features of diaphragmatic initial lymphatics. J. Physiol. 588, 3957–3969. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.196204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller Y. A., Li B., Christinger H. W., Wells J. A., Cunningham B. C., de Vos A. M. (1997). Vascular endothelial growth factor: crystal structure and functional mapping of the kinase domain receptor binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7192–7197. 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld G., Kessler O., Herzog Y. (2002). The interaction of neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 with tyrosine-kinase receptors for VEGF. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 515, 81–90. 10.1007/978-1-4615-0119-0_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson I., Bahram F., Li X., Gualandi L., Koch S., Jarvius M., et al. (2010). VEGF receptor 2/-3 heterodimers detected in situ by proximity ligation on angiogenic sprouts. EMBO J. 29, 1377–1388. 10.1038/emboj.2010.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi H., Saharinen P., Zarkada G., Zheng W., Robciuc M. R., Alitalo K. (2015). VEGF-C is required for intestinal lymphatic vessel maintenance and lipid absorption. EMBO Mol. Med. 7, 1418–1425. 10.15252/emmm.201505731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.-J., Jeltsch M. M., Birkenhäger R., McCarthy J.E. G., Weich H. A., Christ B., et al. (1997). VEGF and VEGF-C: specific induction of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the differentiated avian chorioallantoic membrane. Dev. Biol. 188, 96–109. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary M. A., Bloch J. I., Flynn J. J., Gaudin T. J., Giallombardo A., Giannini N. P., et al. (2013). The placental mammal ancestor and the post–K-Pg radiation of placentals. Science 339, 662–667. 10.1126/science.1229237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson A.-K., Dimberg A., Kreuger J., Claesson-Welsh L. (2006). VEGF receptor signalling in control of vascular function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 359–371. 10.1038/nrm1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandini M., Marconcini L., Ferruzzi R., Oliviero S. (1996). Identification of a c-fos-induced gene that is related to the platelet-derived growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11675–11680. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajusola K., Aprelikova O., Armstrong E., Morris S., Alitalo K. (1993). Two human FLT4 receptor tyrosine kinase isoforms with distinct carboxy terminal tails are produced by alternative processing of primary transcripts. Oncogene 8, 2931–2937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D.-Y., Lee J., Park I., Choi D., Lee S., Song S., et al. (2014). Lymphatic regulator PROX1 determines Schlemm’s canal integrity and identity. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 3960–3974. 10.1172/JCI75392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova T. V., Bono P., Holnthoner W., Chesnes J., Pytowski B., Sihto H., et al. (2008). VEGFR-3 expression is restricted to blood and lymphatic vessels in solid tumors. Cancer Cell 13, 554–556. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova T. V., Mäkinen T., Mäkelä T. P., Saarela J., Virtanen I., Ferrell R. E., et al. (2002). Lymphatic endothelial reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells by the Prox-1 homeobox transcription factor. EMBO J. 21, 4593–4599. 10.1093/emboj/cdf470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas-Paz L., Strilić B., Goedecke A., Breier G., Fässler R., Lammert E. (2012). Mechanoinduction of lymph vessel expansion. EMBO J. 31, 788–804. 10.1038/emboj.2011.456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podgrabinska S., Braun P., Velasco P., Kloos B., Pepper M. S., Jackson D. G., et al. (2002). Molecular characterization of lymphatic endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16069–16074. 10.1073/pnas.242401399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R&D Systems. (2017). Human VEGF-C Quantikine ELISA Kit DVEC00: R&D Systems. Available at: https://www.rndsystems.com/products/human-vegf-c-quantikine-elisa-kit_dvec00

- Rissanen T. T., Markkanen J. E., Gruchala M., Heikura T., Puranen A., Kettunen M. I., et al. (2003). VEGF-D is the strongest angiogenic and lymphangiogenic effector among VEGFs delivered into skeletal muscle via adenoviruses. Circ. Res. 92, 1098–1106. 10.1161/01.RES.0000073584.46059.E3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristimäki A., Narko K., Enholm B., Joukov V., Alitalo K. (1998). Proinflammatory cytokines regulate expression of the lymphatic endothelial mitogen vascular endothelial growth factor-C. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8413–8418. 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. J., Stringer S. E. (2001). The splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their receptors. J. Cell Sci. 114, 853–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roukens M. G., Peterson-Maduro J., Padberg Y., Jeltsch M., Leppänen V.-M., Bos F. L., et al. (2015). Functional dissection of the CCBE1 protein: a crucial requirement for the collagen repeat domain. Circ. Res. 116, 1660–1669. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhrberg C., Gerhardt H., Golding M., Watson R., Ioannidou S., Fujisawa H., et al. (2002). Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 2684–2698. 10.1101/gad.242002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saaristo A., Veikkola T., Tammela T., Enholm B., Karkkainen M. J., Pajusola K., et al. (2002). Lymphangiogenic gene therapy with minimal blood vascular side effects. J. Exp. Med. 196, 719–730. 10.1084/jem.20020587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabine A., Saygili Demir C., Petrova T. V. (2016). Endothelial cell responses to biomechanical forces in lymphatic vessels. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 25, 451–465. 10.1089/ars.2016.6685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saburi S., Hester I., Fischer E., Pontoglio M., Eremina V., Gessler M., et al. (2008). Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 40, 1010. 10.1038/ng.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaupper M., Jeltsch M., Rohringer S., Redl H., Holnthoner W. (2016). Lymphatic vessels in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 22, 395–407. 10.1089/ten.TEB.2016.0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S., Conlin L. K., Gomez L., Aagenaes Ø, Eiklid K., Knisely A. S., et al. (2013). CCBE1 mutation in two siblings, one manifesting lymphedema-cholestasis syndrome, and the other, fetal hydrops. PLoS ONE 8, e75770. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya M. (2001). Structure and function of VEGF/VEGF-receptor system involved in angiogenesis. Cell Struct. Funct. 26, 25–35. 10.1247/csf.26.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. W., Huggenberger R., Detmar M. (2008). Transcriptional profiling of VEGF-A and VEGF-C target genes in lymphatic endothelium reveals endothelial-specific molecule-1 as a novel mediator of lymphangiogenesis. Blood 112, 2318–2326. 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried G., Basak A., Cromlish J. A., Benjannet S., Marcinkiewicz J., Chrétien M., et al. (2003). The secretory proprotein convertases furin, PC5, and PC7 activate VEGF-C to induce tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1723–1732. 10.1172/JCI17220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soker S., Miao H.-Q., Nomi M., Takashima S., Klagsbrun M. (2002). VEGF165 mediates formation of complexes containing VEGFR-2 and neuropilin-1 that enhance VEGF165-receptor binding. J. Cell. Biochem. 85, 357–368. 10.1002/jcb.10140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldi R., Mitola S., Strasly M., Defilippi P., Tarone G., Bussolino F. (1999). Role of alphavbeta3 integrin in the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. EMBO J. 18, 882–892. 10.1093/emboj/18.4.882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacker S. A., Stenvers K., Caesar C., Vitali A., Domagala T., Nice E., et al. (1999). Biosynthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor-D involves proteolytic processing which generates non-covalent homodimers. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32127–32136. 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweat R. S., Sloas D. C., Murfee W. L. (2014). VEGF-C induces lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in the rat mesentery culture model. Microcirculation 21, 532–540. 10.1111/micc.12132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuba A., Skobe M., Karkkainen M. J., Shin W. S., Beynet D. P., Rockson N. B., et al. (2002). Therapeutic lymphangiogenesis with human recombinant VEGF-C. FASEB J. 16, 1985–1987. 10.1096/fj.02-0401fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T., Saaristo A., Holopainen T., Lyytikkä J., Kotronen A., Pitkonen M., et al. (2007). Therapeutic differentiation and maturation of lymphatic vessels after lymph node dissection and transplantation. Nat. Med. 13, 1458–1466. 10.1038/nm1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervala T. V., Hartiala P., Tammela T., Visuri M. T., Ylä-Herttuala S., Alitalo K., et al. (2015). Growth factor therapy and lymph node graft for lymphedema. J. Surg. Res. 196, 200–207. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veikkola T., Jussila L., Makinen T., Karpanen T., Jeltsch M., Petrova T. V., et al. (2001). Signalling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 is sufficient for lymphangiogenesis in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 20, 1223–1231. 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veikkola T., Lohela M., Ikenberg K., Makinen T., Korff T., Saaristo A., et al. (2003). Intrinsic versus micro environmental regulation of lymphatic endothelial cell phenotype and function. FASEB J. 17, 2006–2013. 10.1096/fj.03-0179com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villefranc J. A., Nicoli S., Bentley K., Jeltsch M., Zarkada G., Moore J. C., et al. (2013). A truncation allele in vascular endothelial growth factor c reveals distinct modes of signaling during lymphatic and vascular development. Development 140, 1497–1506. 10.1242/dev.084152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros A., Reiterer M., Schaefer B., Finkenstedt A., Schneeberger S., Schwaighofer H., et al. (2017). CCBE1 mutation causing sclerosing cholangitis: expanding the spectrum of lymphedema-cholestasis syndrome. Hepatology 66, 286–288. 10.1002/hep.29037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker A., Gerhardt H., Phng L.-K. (2014). Tissue guidance without filopodia. Commun. Integr. Biol. 7, e28820. 10.4161/cib.28820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Yuan L., Mak J., Pardanaud L., Caunt M., Kasman I., et al. (2010). Neuropilin-2 mediates VEGF-C–induced lymphatic sprouting together with VEGFR3. J. Cell Biol. 188, 115–130. 10.1083/jcb.200903137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Nezu J., Shimane M., Hirata Y. (1997). Molecular cloning of a novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-D. Genomics 42, 483–488. 10.1006/geno.1997.4774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y., Murayama T., Gravereaux E., Tkebuchava T., Silver M., Curry C., et al. (2003). VEGF-C gene therapy augments postnatal lymphangiogenesis and ameliorates secondary lymphedema. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 717–725. 10.1172/JCI15830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Groopman J. E., Wang J. F. (2005). Extracellular matrix regulates endothelial functions through interaction of VEGFR-3 and integrin alpha5beta1. J. Cell. Physiol. 202, 205–214. 10.1002/jcp.20106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Guo R., Wood R., Boyce B. F., Liang Q., Wang Y.-J., et al. (2011). VEGF-C attenuates joint damage in chronic inflammatory arthritis by accelerating local lymphatic drainage. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 2318–2328. 10.1002/art.30421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]