We report a new membrane system showing dynamic controllable multiphase transport and separation under steady-state pressure.

Abstract

The development of membrane technology is central to fields ranging from resource harvesting to medicine, but the existing designs are unable to handle the complex sorting of multiphase substances required for many systems. Especially, the dynamic multiphase transport and separation under a steady-state applied pressure have great benefits for membrane science, but have not been realized at present. Moreover, the incorporation of precisely dynamic control with avoidance of contamination of membranes remains elusive. We show a versatile strategy for creating elastomeric microporous membrane-based systems that can finely control and dynamically modulate the sorting of a wide range of gases and liquids under a steady-state applied pressure, nearly eliminate fouling, and can be easily applied over many size scales, pressures, and environments. Experiments and theoretical calculation demonstrate the stability of our system and the tunability of the critical pressure. Dynamic transport of gas and liquid can be achieved through our gating interfacial design and the controllable pores’ deformation without changing the applied pressure. Therefore, we believe that this system will bring new opportunities for many applications, such as gas-involved chemical reactions, fuel cells, multiphase separation, multiphase flow, multiphase microreactors, colloidal particle synthesis, and sizing nano/microparticles.

INTRODUCTION

Directed transport and separation of gas and liquid through membranes are of great significance in real-world applications, such as gas-involved chemical reactions (1), fuel cells (2, 3), multiphase flow (4, 5), multiphase microreactors (4, 6), droplet microfluidics (7), colloidal particle synthesis (8), sizing nano/microparticles (9), etc. Various functional membranes for controllable gas and liquid transport (10–12) and multiphase separation (13–18) have been developed. Conventionally, the multiphase are separated on the basis of the tunable wettability, which allows the penetration of one phase while blocking the other phases (15, 19). Although remarkable achievements have been made in membrane technologies, persistent challenges remain unresolved, specifically (i) keeping the trade-off of the permeability and selectivity of membrane materials, (ii) realizing dynamically controllable substance transport and multiphase separation, (iii) realizing the multiphase separation under a steady-state pressure, (iv) achieving antifouling properties, and (v) keeping robustness of the operation (20). Pore size and inner surface properties of the membranes are two key factors in determining membrane separation property (21–23). On the one hand, attempts have been made to control the pore geometry of the membranes. However, for traditional porous membranes (polyvinylidene difluoride, polytetrafluoroethylene, nylon, etc.) (24), the pore size cannot be dynamically adjusted once the membranes are fabricated (21). On the other hand, the inner surface of porous membranes is functionalized to obtain selectivity for fluid separation (25–27). In this case, inner surface modification usually makes the preparation process more complex, and it pushes harder to dynamically modify the inner surface while transporting substances (28).

It is worth mentioning that dynamic multiphase transport and separation under a steady-state applied pressure could bring great benefits for membrane science but remain as a distant prospect. For the traditional system, most of the multiphase transport and separation are based on pressure changes. For instance, degassing by reducing the pressure (29) or liquid-liquid separation by increasing the pressure (30) usually needs extra energy to make the pressure change. Meanwhile, the pressure change will also affect the entire system, not just the membrane itself, and thus the energy acted on the other parts is wasted. Besides, the unstable pressure condition may impede many real-world applications, because many chemical reactions need steady-state pressure conditions to ensure high chemical efficiency and yield.

To address the above issues, here we show a versatile strategy for creating a new family of dynamic hybrid liquid-solid membrane—liquid gating elastomeric porous membrane (LGEPM) system. It consists of an elastomeric porous membrane (EPM) infiltrated with a functional liquid that can use the tunability of the elastomeric membrane material and the membrane’s interaction with the gating liquid. The dynamically controllable gas and liquid transport and separation are achieved by our gating interfacial design and by adjusting the pore size of membranes. The dynamic multiphase separation can be achieved under a steady-state applied pressure. Elastomeric materials (EMs) have been widely applied in stretchable devices (12, 31–34) and bring new opportunities to develop porous membranes with adjustable pores for multiphase transport and separation (35–38). Moreover, the immiscible liquid can have a random shape to adjust itself to the external condition, and it brings an ideal dynamic material with solid porous membranes to provide the new gating strategies (28). The liquid-based system transforms the basic scientific properties of the membranes from a solid-liquid/solid-gas interface to a liquid-liquid/liquid-gas interface. Each transport substance has a specific critical pressure to overcome the capillary pressure at the liquid-gas or liquid-liquid interface. This LGEPM system exhibits an unprecedented combination of good permeability with excellent selectivity. Meanwhile, on the basis of our interfacial design, this tunable system could promote a potential to dynamically separate gas and liquid by simply deforming the EPMs. To establish a stable LGEPM system, the membrane material and fluid materials are rationalized for a lower energy state. By optimizing the interfacial configuration, it ensures a sustainable antifouling behavior. Because of the elastic nature of the materials, this system exhibits excellent recovery, adaptivity, and robust operation. The system may enlighten further experimental and theoretical efforts for applications in gas-involved chemical reactions (8) and can be further generalized to other more complicated functional EPMs for the exploitation of smart membrane materials (9, 39–41).

RESULTS

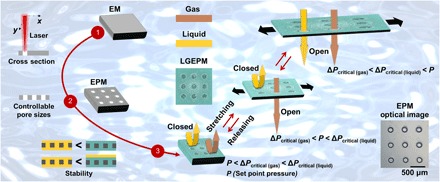

The LGEPM system is composed of an EPM impregnated with a selected gating liquid. Figure 1 provides an illustration of the preparation of the system and the operation mechanism. LGEPM is formed by impregnating a functional gating liquid into a suitable porous membrane. On the basis of our gating interfacial design, the gating liquid is capillary-stabilized in the porous structure. To ensure a stable LGEPM system, the interfacial design for getting the lower energy state is performed by setting energy criteria among the membrane, the gating liquid, and the transport fluid. The EPM with porous array structures and controllable sizes can be fabricated from EM by laser cutting methods (figs. S1 and S3). The whole membrane with homogeneous pores in the central area is shown in fig. S2. EPM can also be formed by replica molding (fig. S4). Each method is beneficial for fabricating certain ranges of pore geometry. Optimal pore sizes ranging from 5 to 350 μm could be obtained.

Fig. 1. Preparation and schematics of the LGEPM system.

Gas is in brown, liquid is in yellow, and LGEPM is in green. EPM is fabricated from EM by laser cutting. Pore sizes in the EPM are rationally controllable. By impregnating a gating liquid in the EPM, LGEPM is formed. To establish a stable LGEPM system, the materials should follow a proper interfacial design. Transport of gas and liquid can be dynamically controlled by deforming the LGEPM. If both ΔPcritical (gas) and ΔPcritical (liquid) are higher than the applied pressure P, neither of them will penetrate the LGEPM. The pore size of LGEPM increases with stretching, and the critical pressure of the transport substance decreases simultaneously. When ΔPcritical (gas) is below P and ΔPcritical (liquid) is above P, only gas permeates the LGEPM. As the stretching process continues, the critical pressure continually drops. When both ΔPcritical (gas) and ΔPcritical (liquid) are lower than P, both gas and liquid flow through the LGEPM. Once the stress is released, the LGEPM recovers to its initial state. The inset shows a microscopic image of an EPM demonstrating a homogeneous pore distribution (scale bar, 500 μm).

The LGEPM deforms continuously once a mechanical stress is applied; hence, this system can be used to dynamically tune the abilities for transporting and separating the target substance. In this process, the pore deformation plays an important role in governing the critical pressure of the transport fluid. Therefore, by stretching and releasing the LGEPM, their critical pressure can be dynamically controlled, whereas the applied pressure is kept as a constant during the deformation. It brings new possibilities for dynamic multiphase separation applications at multiple fixed pressures. For instance, gas and liquid can be efficiently separated from their mixture via the LGEPM. When the tunable critical pressure of both gas and liquid is higher than the applied pressure (P) [denoted as P < ΔPcritical (gas) < ΔPcritical (liquid)], neither would penetrate the LGEPM. Thus, the LGEPM is in a “closed” state for both gas and liquid. When the mechanical stretch is applied to the LGEPM, the pores of the LGEPM are expanded and the tunable critical pressure of transport substances decreases. When the tunable critical pressure of gas is lower than P and the tunable critical pressure of liquid is higher than P [denoted as ΔPcritical (gas) < P < ΔPcritical (liquid)], only gas flows through the LGEPM. As the stretching process continues, the pores are further expanded and the tunable critical pressure of transport substances further decreases. Once the tunable critical pressure of both gas and liquid is below the applied pressure [denoted as ΔPcritical (gas) < ΔPcritical (liquid) < P], the mixture transports through the LGEPM. When the stress is released, the LGEPM returns to its original state. This LGEPM system provides new strategies for dynamic, responsive, selective, and tunable gas and liquid transport (movie S1).

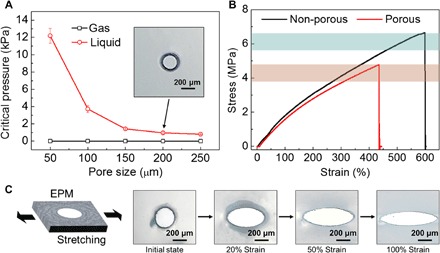

The critical pressure of transporting gas and liquid through the EPM with various pore sizes is determined, as in Fig. 2A. The critical pressure of gas [ΔPcritical (gas)] is zero and that of liquid [ΔPcritical (liquid)] decreases with increasing pore size. For the transport of liquid through the EPM, the critical pressure depends on the Laplace pressure, 4γlg/d, where γlg is the liquid-gas surface tension and d is the average effective pore size. Among the pore size range of 50 to 250 μm, the critical pressure of liquid decreases markedly among the size range of 50 to 150 μm, whereas it does not vary much among the size range of 150 to 250 μm. Nice and round pores are distributed on the EPM, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2A. The pressure difference between ΔPcritical (liquid) and ΔPcritical (gas) also diminishes with increasing pore size. To control the pore size of the EPM, it is necessary to examine the elasticity of the material. For the nonporous silicone rubber membrane, the maximum strain could be up to 600% with the highest stress of 6.7 MPa. For the porous silicone rubber membrane, the maximum strain could be up to 430% with the highest stress of 4.8 MPa (Fig. 2B). The reduction of the maximum strain is related to the pore sensitivity of the EM due to the existence of pores (42). By stretching the EPM in one dimension, dramatic shape change is observed. By increasing the deformation extent from the initial state (0%) to 100% strain in the longitudinal direction, the round pore changes to ellipse gradually and, meanwhile, the area of the pore increases upon stretching (Fig. 2C and movie S2).

Fig. 2. Influence of pore size on the transport substance and the feasibility of pore size control.

(A) Pore size dependence of critical pressure of gas and liquid through the bare EPM. (B) Stress-strain behavior of a nonporous and a porous silicone rubber membrane. (C) Optical micrographs of a pore in EPM during stretching, with the images representing 0 to 100% strain (from left to right).

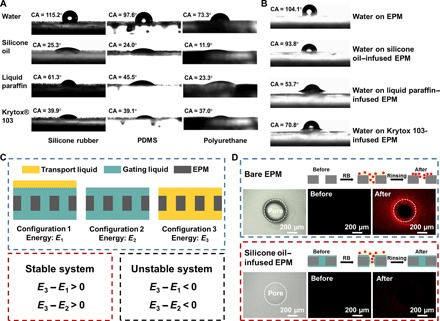

To transport the substance through the LGEPM system, we need to ensure that the transport fluid would not replace the gating liquid inside the membrane. For the transport gas, it ideally satisfies this criterion. To get a stable system when transporting liquid through the LGEPM system, it is necessary to check the wettability of the gating and transport liquid on the EPM, the wettability of the transport liquid on the LGEPM, and the interfacial energy of different configurations. The contact angle (CA) of water, silicone oil, liquid paraffin, and Krytox 103 oil on the substrates of silicone rubber, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and polyurethane were measured. Water shows a CA higher than 90° on silicone rubber and PDMS, whereas it has a CA of 73.3 ± 4.7° on polyurethane. Silicone oil has a low CA of 25.3 ± 1.9°, 24.0 ± 2.3°, and 11.9 ± 0.9° on silicone rubber, PDMS, and polyurethane, respectively. Using the silicone oil as the gating liquid and water as the transport liquid, silicone oil shows a higher affinity on the selected substrates than that of water (Fig. 3A). Similarly, liquid paraffin and Krytox 103 also preferentially wet those substrates better than water. When the EPM (silicone rubber) is infused with silicone oil, liquid paraffin, and Krytox 103, water has different CAs on those liquid surfaces. Those CAs are smaller than that on the bare EPM (Fig. 3B). Thus, it is also necessary to compare the surface tension of those liquids and the interfacial surface tension between water and those liquids (Table 1). To ensure a stable LGEPM system, the total interfacial energies of the following configurations should be considered: (i) the membrane is infused with the gating liquid and the transport fluid is floating on top of it (E1), (ii) the membrane is infused with the gating liquid (E2), and (iii) the membrane is infused with the transport fluid (E3) (Fig. 3C). To make sure that the porous membrane has a higher affinity to the gating liquid than the transport fluid, one should satisfy ΔEI = E3 – E1 > 0 and ΔEII = E3 – E2 > 0 (43). ΔEI and ΔEII are interpreted as

| (1) |

| (2) |

where R is the roughness factor of the EPM (R = 2), which is determined as the ratio between the actual and projected surface areas. γA, γB, and γAB represent the surface tension of transport liquid, gating liquid, and the interfacial surface tension between the transport and gating liquids. θA and θB are the equilibrium CAs of the transport and gating liquids on a flat solid membrane surface, respectively.

Fig. 3. The wettability, energy critera, and antifouling properties of LGEPM.

(A) The CA of water, silicone oil, liquid paraffin, and Krytox 103 on silicone rubber, PDMS, and polyurethane membrane. (B) The CA of water on EPM, silicone oil–, liquid paraffin–, and Krytox 103–infused EPM. EPM is silicone rubber. (C) The energy of different configurations and the criteria for a stable and unstable LGEPM system. (D) The comparison of untreated and RB-treated bare EPM and silicone oil–infused EPM. EPM is silicone rubber.

Table 1. Comparison of theoretical relationship with experimental results for various porous membrane/gating liquid/transport liquid combinations.

The parameters are measured at room temperature (25°C). The unit of γA, γB, γAB, ΔEI, and ΔEII is mN/m. The unit of θA and θB is degrees (°). The case number is arranged on the basis of the order of solid materials.

| Case no. | Solid materials | Transport liquid (A) | Gating liquid (B) | γA | γB | γAB | θA | θB | ΔE1 | ΔE2 |

Stable system? |

|

| Theo. | Exp. | |||||||||||

| 1 | Silicone rubber | DI water | Silicone oil | 72.4 | 17.4 | 42.6 | 115.2 | 25.3 | 46.5 | 144.1 | Y | Y |

| 2 | Silicone rubber | DI water | Liquid paraffin | 72.4 | 29.6 | 41.6 | 115.2 | 61.3 | 41.8 | 126.2 | Y | Y |

| 3 | Silicone rubber | Liquid paraffin | Silicone oil | 29.6 | 17.4 | 0.4 | 61.3 | 25.3 | 2.6 | 15.2 | Y | Y |

| 4 | Silicone rubber | DI water | Krytox 103 | 72.4 | 17.7 | 53.7 | 115.2 | 39.9 | 34.9 | 143.3 | Y | Y |

| 5 | Silicone rubber | Silicone oil | Krytox 103 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 9.8 | 25.3 | 39.9 | −14.1 | −4.6 | N | N |

| 6 | Silicone rubber | Liquid paraffin | Krytox 103 | 29.6 | 17.7 | 11.0 | 61.3 | 39.9 | −12.4 | 10.6 | Y/N | N |

| 7 | PDMS | DI water | Silicone oil | 72.4 | 17.4 | 42.6 | 97.6 | 24.0 | 8.2 | 105.8 | Y | Y |

| 8 | PDMS | DI water | Liquid paraffin | 72.4 | 29.6 | 41.6 | 97.6 | 45.5 | 19.0 | 103.4 | Y | Y |

| 9 | PDMS | Liquid paraffin | Silicone oil | 29.6 | 17.4 | 0.4 | 45.5 | 24.0 | −10.1 | 2.5 | Y/N | N |

| 10 | PDMS | DI water | Krytox 103 | 72.4 | 17.7 | 53.7 | 97.6 | 39.1 | −7.2 | 101.2 | Y/N | Y |

| 11 | PDMS | Silicone oil | Krytox 103 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 9.8 | 24.0 | 39.1 | −14.1 | −4.6 | N | N |

| 12 | PDMS | Liquid paraffin | Krytox 103 | 29.6 | 17.7 | 11.0 | 45.5 | 39.1 | −25.1 | −2.2 | N | N |

| 13 | Polyurethane | DI water | Silicone oil | 72.4 | 17.4 | 42.6 | 73.3 | 11.9 | −50.2 | 47.4 | Y/N | N |

| 14 | Polyurethane | DI water | Liquid paraffin | 72.4 | 29.6 | 41.6 | 73.3 | 23.3 | −28.9 | 55.5 | Y/N | N |

| 15 | Polyurethane | Liquid paraffin | Silicone oil | 29.6 | 17.4 | 0.4 | 23.3 | 11.9 | −20.7 | −8.1 | N | N |

| 16 | Polyurethane | DI water | Krytox 103 | 72.4 | 17.7 | 53.7 | 73.3 | 37.0 | −67.1 | 41.3 | Y/N | N |

| 17 | Polyurethane | Silicone oil | Krytox 103 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 9.8 | 11.9 | 37.0 | −15.6 | −6.1 | N | N |

| 18 | Polyurethane | Liquid paraffin | Krytox 103 | 29.6 | 17.7 | 11.0 | 23.3 | 37.0 | −37.1 | −14.2 | N | N |

Theoretically, when both ΔEI and ΔEII are positive values, LGEPM is a stable system. However, if both are negative values, LGEPM tends to be an unstable system. Therefore, different EPMs with silicone oil, liquid paraffin, and Krytox 103 as the gating liquid, and water as the transport liquid were analyzed via the energy relationship. We found that the application of silicone oil, liquid paraffin, and Krytox 103 in silicone rubber porous membrane ensures a stable LGEPM system both theoretically and experimentally for transporting deionized (DI) water. Extensive comparisons of various configurations are discussed in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that silicone oil–infused EPM also exhibits excellent antifouling property (Fig. 3D). Rhodamine B (RB) is chosen as a representative example to test the antifouling property, because RB is an extremely sticky organic molecule that can attach to surfaces by nonspecific bonding. Both the bare and silicone oil–infused EPMs are treated with RB solution and then rinsed with DI water. Initially, both the bare and silicone oil–infused EPMs do not show any fluorescence. After RB treatment, the bare EPM is contaminated with RB even after rinsing, whereas the silicone oil–infused EPM does not show any fluorescence, indicating its antifouling property.

As mentioned above, satisfying both Eqs. 1 and 2 will ensure a stable LGEPM system. Conversely, when neither Eq. 1 nor Eq. 2 is satisfied, gating liquid will be replaced by transport liquid. If only one of the equations is satisfied, gating liquid might or might not be replaced by transport liquid. Hence, we explored different combinations of porous membrane/gating liquid/transport liquid and compared the experimental results with the theoretical relationships. Our findings indicate that these relationships are in accordance with all the experimental configurations (Table 1). In the case of a silicone rubber porous membrane with silicone oil, liquid paraffin, or Krytox 103 as the gating liquid and with DI water as the transport liquid, the system is both theoretically and experimentally stable (cases 1, 2, and 4). A silicone rubber porous membrane with silicone oil as the gating liquid and liquid paraffin as the transport liquid is also a stable systems, both theoretically and experimentally (case 3). Similarly, a PDMS porous membrane with silicone oil or liquid paraffin as the gating liquid to transport DI water is a stable system both theoretically and experimentally (cases 7 and 8). For those systems that may or may not be stable theoretically, most of them are proven to be experimentally unstable (cases 6, 9, 13, 14, and 16), whereas only one case shows experimental stability (case 10). Those systems that are always theoretically unstable are also experimentally unstable (case 5, 11, 12, 15, 17, and 18).

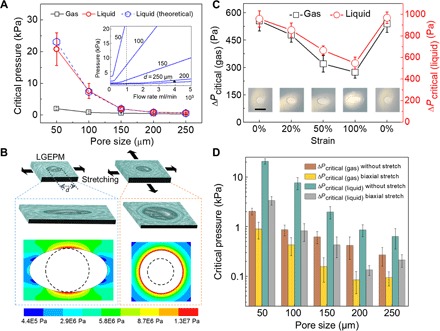

Next, the LGEPM system (case 1) under static one- and two-dimensional stretching was studied. Without any deformation, it is necessary to examine the relation between the critical pressure and pore size. On the basis of the experimental results, the critical pressure of both gas and liquid decreases with increasing the pore size in LGEPM (Fig. 4A), which is similar to the liquid passing through the bare EPM in Fig. 2A. Theoretically, the transport of gas and liquid through the LGEPM is expected to occur through the capillary mechanism. The critical pressure will be the one to deform the surface of the gating liquid. For a gas, the pressure that has to be overcome is the Laplace pressure (21), 4γlg/d, where γlg is the liquid-gas surface tension and d is the average effective pore size. For a liquid, the critical pressure will be related to the liquid-liquid interfacial tension γll and also the effective pore size d, that is, 4γll/d. Therefore, theoretically, the smaller the pore size, the higher pressure is needed to transport the substance.

Fig. 4. Static mechanical stretching of LGEPM and the critical pressure of gas and liquid during stretching.

(A) Pore size depedence of the critical pressure of gas and liquid transported through the LGEPM at a certain flow rate (1000 μl/min). Inset is the theoretical model of the critical pressure of LGEPM with different pore sizes at different flow rates. (B) Schematic illustration of one- and two-dimensional stretch applied to the LGEPM, and upon deformation, the LGEPM elongates in the direction of stretching. Inserted figures depict the stress distribution surrounding the pore in the one- and two-dimensional stretching process. Dashed circles represent the initial size of the pores. (C) Critical pressure of gas and liquid flowing through the LGEPM as a function of one-dimensional strain. Insets are the representative optical images of LGEPM during the deformation process. Scale bar, 200 μm. (D) Critical pressure of gas and liquid flowing through the LGEPM in various pore sizes without stretch and with two-dimensional stretch (50% strain biaxially). Gating liquid in (A), (C), and (D) is silicone oil. EPM is silicone rubber.

For the gas or liquid passing through the porous membrane, the transmembrane pressure ΔP will also depend on the flow rate Q by the Darcy’s law (21, 44–46)

| (3) |

where A and h represent the area and thickness, respectively, of the porous membrane, μ is the viscosity of the liquid, and k is the permeability of the porous membrane. k is interpreted as (21, 44, 45, 47)

| (4) |

where Φ is the porosity, γ is the liquid-gas surface tension when transporting gas or liquid-liquid surface tension when transporting liquid through the LGEPM, d is the average pore size, and σ is the SD of distributed pore sizes in the membrane. This relationship agrees well with the experimental gating pressure at different flow rates (fig. S5). Using our model, we predict how the gating pressure for transporting water depends on the pore size of the membrane (Fig. 4A, inset). The theoretical curve is in accordance with the experimental results (Fig. 4A, blue curve), where the crtical pressure decreases with increasing the pore size.

On the basis of the elastic nature of the LGEPM, the pore geometry can be dynamically tuned. Thus, the critical pressure of the transport substance through this system could be dynamically modulated for a given membrane. During one-dimensional stretching, the pore in the membrane extends from circular to elliptical and the stress is concentrated on the circle along the nonstretched axis (Fig. 4B, left, and movie S2), whereas during two-dimensional stretching, the pore extends biaxially and the stress is distributed around the pore with gradient (Fig. 4B, right). The stress distribution of pore arrays under one- and two-dimensional stretching also indicates similar concentrated stress to that of the single pore (fig. S6). In addition, the pressure difference caused by the surface tension of the gating liquid (hundreds of pascal) is much lower than that caused by the mechanical force (in megapascal), so that it will not influence the deformation of the LGEPM system (Fig. 4B). In both one- and two-dimensional stretching cases, the area of the pore increases during stretching. For one-dimensional stretching, the critical pressure of gas and liquid both decreases with increasing strain. When the system is stretched to 100% strain, ΔPcritical (gas) reduces from 555 ± 55 to 274 ± 32 Pa, whereas ΔPcritical (liquid) reduces from 958 ± 75 to 547 ± 56 Pa (Fig. 4C). At different extent of deformation, the pressure change of gas and liquid is different, and the pressure change of gas is more dramatic than that of liquid (fig. S7). If the stress is released, the LGEPM returns to the original state. For two-dimensional stretching to the strain of 50%, all the LGEPMs with various pore sizes from 50 to 250 μm, ΔPcritical (gas) and ΔPcritical (liquid) both drop markedly under the strain (Fig. 4D). The system recovers once the biaxial stress is released. It also indicates that the normalized change of critical pressure caused by two-dimensional stretching is more dramatical than that caused by one-dimensional stretching. Subsequently, we also explored more for the static deformation of the LGEPM by not impreganating the gating liquid (fig. S8), varying the pore size of the EPM (fig. S9), and substituting the gating liquid with liquid paraffin (fig. S10). All the results indicate that the critical pressure of transport fluid decreases with increasing the extent of stretching, and the state can recover upon the relaxation of the mechanical stretch. For transporting the same fluid (DI water as an example), different membane materials and different gating liquids were examined to form different LGEPM configurations (fig. S11). For the same membrane infused with different gating liquids or applying the same gating liquid in different porous membranes, the critical pressure of transport fluid to permeate LGEPM is different due to the difference of surface tensions of the gating liquid, the affinity of the gating liquid to the membrane, and the interficial surface tensions between the gating liquid and transport liquid (fig. S11).

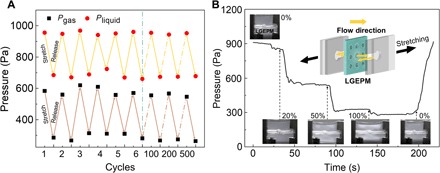

To further examine this scenario, we studied periodic one-dimensional static deformations and dynamic deformations of LGEPM. The LGEPM still works well after long cyclic deformations. Figure 5A demonstrates the pressure response to the repeated one-dimensional static stretch and release steps up to 500 cycles (50% strain). The critical pressure of both gas and water changes periodically with stretching and releasing. The pressure reduces when the LGEPM is stretched and recovers when the mechanical force is released (Fig. 5A and fig. S12). If the mechanical stimulus is dynamically applied to the LGEPM, the pressure of the transport fluid dynamically changes with the applied stress, as shown in Fig. 5B. The nonstretched and stretched (50% strain) porous membranes both show uniform pore distribution in the center of the membrane, as shown in fig. S13. If nonuniform pores are distributed in the membrane, compared with the membranes bearing uniform pores in it (the same pore area for the two membranes), the critical pressure of the transport substance will decrease because of the larger permeability through the larger pores (fig. S14). Obviously, the pore size is markedly changed with the deformation of LGEPM (movie S3). By slightly stretching the system to 20% strain, the pressure decreases sharply from 900 to 563 Pa. With further stretching to 50% strain, the pressure reduces to 315 Pa (Fig. 5B). When stretched to 100% strain, the pressure drops to 275 Pa. As soon as the stress is released, the strain recovers to zero and the pressure goes up to 915 Pa. The three “steps” show that LGEPM has a real-time pressure response to the mechanical stimulus. During the dynamic stretching process, the pressure remains stable as long as there is no strain. This paves the fundament for the dynamic transport and separation of different fluids.

Fig. 5. The durability of LGEPM during static deformation and liquid transport in a dynamic one-dimensional stretching process.

(A) The transport of gas and liquid can be periodically controlled through the LGEPM system. (B) Transport of liquid in a dynamic deformation process. The inset is a schematic of the LGEPM system. Inserted optical images are the corresponding LGEPM systems under different deformation extent.

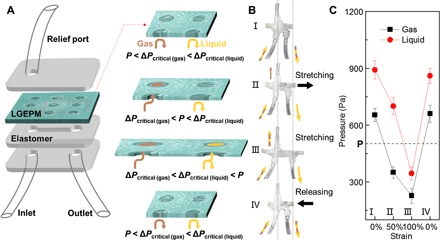

Furthermore, an LGEPM-based device is developed that enables active and selective transport by simply adjusting the mechanical stress (Fig. 6). Repelling both gas and liquid, transporting gas but repelling the liquid, and transporting both gas and liquid can be realized in different pressure ranges while maintaining the applied pressure P as a constant (Fig. 6, A and B). Before stretching [denoted as P < ΔPcritical (gas) < ΔPcritical (liquid)], both gas and liquid were repelled because of the small pore size and large crtical pressures (Fig. 6B, state I). When the critical pressure of gas drops below the applied pressure resulting from the expansion of pore size in the stretching process [denoted as ΔPcritical (gas) < P < ΔPcritical (liquid)], gas penetrates the membranes to the relief port while liquid flows through the outlet (Fig. 6B, state II). Thus, the outlets are degassed liquid. In this case, gas and liquid could be thoroughly separated. On the basis of the current design, the separation efficiency is ~97%. With further stretching and expanding of pores, the critical pressure of gas and liquid further drops [denoted as ΔPcritical (gas) < ΔPcritical (liquid) < P] and liquid can also penetrate the LGEPM; therefore, both gas and liquid flow through the relief port (Fig. 6B, state III). Once the stress is released, both gas and liquid are repelled by the LGEPM and flow through the outlet (Fig. 6B, state IV). The whole process of dynamic gas and liquid transport was monitored by measuring the critcal pressure of the gas and liquid, as shown in Fig. 6C (movie S4). It is worth mentioning that this approach achieves the phases transport and separation from their mixture merely by dynamically modulating the mechanical stress. It is based on the dynamic tunability of the materials under the steady-state pressure (the applied pressure P is 500 Pa; Fig. 6C) instead of adjusting the applied pressure of fluids through the system, which is limited in previous gating systems (21).

Fig. 6. Dynamic gas and liquid transport by LGEPM.

(A) Left: Sketch of the LGEPM in dynamic gas and liquid transport (not to scale). Right: Detailed states of the LGEPM under various strains. (B) Snapshots of the stretching and releasing process. (C) Pressure control for transporting and separating gas and liquid in a dynamic process.

DISCUSSION

In conclusion, we introduce an LGEPM system to dynamically control the transport and separation of gas and liquid under a steady-state applied pressure in response to a mechanical stimulus. The feasibility of adjusting the pore size, the selectivity of interfacial configurations, and the stability of the LGEPM are investigated. We rationalize the energy configurations from different combinations of materials to form a stable system. Because of optimized material selection and interfacial design, antifouling behavior is obtained. By the static one- or two-dimensional deformation and dynamic deformation of the LGEPM, the critical pressure of the transport fluid can be rationally tuned. Moreover, the dynamic gas and liquid transport and separation are achieved by using a proper interfacial configuration and by mechanically adjusting the extent of stretch on the LGEPM system. In this process, the tunability of the critical pressure relies on the deformation of the porous materials under a steady-state pressure rather than modifying the applied pressure. We anticipate that the dynamic tunabilities of the LGEPM itself combined with the liquid-liquid or liquid-gas interfacial design will be of benefit in the fields ranging from gas-involved chemical reactions, fuel cells, medical devices, and multiphase reactions, to colloidal particle synthesis and beyond.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material fabrication

Silicone rubber membranes and polyurethane membranes were purchased from Tuohong Co. Ltd. Silicone oil was purchased from Macklin, and liquid paraffin was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer base and Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer curing agent were purchased from Dow Corning Corporation. PDMS membranes were prepared by mixing the base and curing agent at a 10:1 curing ratio and curing for 3 hours at 70°C. The EPMs were fabricated by multiple methods. Porous silicone rubber and polyurethane membranes with pore size larger than 100 μm were fabricated by Huagong CO2 Laser LSC 20 with the maximum power at 30 W. Porous silicone rubber membranes with pore size <50 μm were fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Cutting in Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Porous PDMS membranes were fabricated by replica molding from silicon mold conducted by the School of Electronics Engineering and Computer Science, Peking University. All chemicals were chemically pure–grade and were used as received. Air was used as the gas. Milli-Q DI water with a resistivity of 18.2 megohm·cm was used in all experiments. Liquid-infused membranes were generated by infusing the silicone oil, liquid paraffin, or Krytox 103 into a variety of porous membranes. They were prepared by dropping ~10 μl cm−2 gating liquid on the surfaces of porous membranes, and uniform coverage was achieved after a while. RB aqueous solution was prepared by dissolving RB powders in DI water at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml.

Surface characterization

An Olympus DP80 optical microscope was used to determine the surface morphology. Fluorescent and bright-field optical images were obtained by a DM 6000B Leica microscope.

Wetting characterization

Water CA, surface tension of water, silicone oil, liquid paraffin, Krytox 103, and interfacial tension between different liquids were measured by a CA measurement system OCA100 (DataPhysics). In the CA measurements, small droplets of water (5 μl) were placed on multiple areas on the surface of the samples. Surface tension and interfacial tension were measured through the pendant drop method. The value of CA, surface tension, and interfacial tension was an average of at least five independent measurements.

Stress-strain test and mechanical stimulus experiments

The stress-strain test was conducted on an ESM301 motorized test stand. Sample size was 10 mm × 1 mm × 0.2 mm. For the static deformation test, the single porous membrane was prestretched and then sealed in two polymethyl methacrylate sheets to measure the critical pressures. More than 100 cycles of stretching and releasing experiments were taken by an electric tensile rig fabricated by Shanghai Shigan Co. Ltd. The maximum force it can provide was 500 N. For the dynamic deformation test, the multiporous membrane was assembled and sealed with several layers of 3M VHB tapes. Then, the dynamic stretching and releasing tests were carried out by the electric tensile rig. Software ANSYS 17.0 finite-element analysis was used to simulate the stress distribution. In the stress simulation, the Young’s modulus of silicone rubber was set as 5 MPa, the Poisson’s ratio was taken as 0.49, and the load was 500 N/cm2.

Transmembrane pressure measurements

The transmembrane properties of the EPMs with and without gating liquids were determined by measuring the transmembrane pressure (ΔP) during the flow of air and DI water. ΔP was measured by wet/wet current output differential pressure transmitters (PX154-025DI and PX273-020DI) from OMEGA Engineering Inc. (Stamford). A porous membrane in a square shape (the average length is 40 mm, as shown in fig. S2) was sealed in 3M VHB tapes. Single porous membranes were used in Figs. 2, 4, and 5A; otherwise, multiporous membranes with nine pores were used. A Harvard Apparatus PHD ULTRA Syringe Pump was used in all experiments. A flow rate of 1000 μl min−1 was used in the experiments of Figs. 2A, 4 (A and C), and 5. A flow rate of 100 μl min−1 was used in the experiments of Fig. 6. For the gas-liquid separation experiments, air and DI water were pumped together to form the gas-liquid mixture at a flow rate of 1000 μl min−1. The bubble size of the gas is from 5 to 10 mm in length (the pumping tube has an inner diameter of 2 mm, and the bubble volume is about 15.7 to 31.4 μl). The separation efficiency was calculated by comparing the volume of water obtained in the outlet with the volume of input liquid during a period of time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The preparation of LGEPM, surface characterization, wetting characterization, transmembrane pressure tests, and most of the work were performed in Xiamen University. The fabrication of EPM and stress-strain tests were performed in the Key Laboratory of Bio-inspired Materials and Interfacial Science, Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry. Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21673197), the Young Overseas High-level Talents Introduction Plan, the 111 Project (grant no. B16029), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (grant no. 20720170050). Author contributions: X.H. conceived the idea. X.H., Z.S., and H.W. designed the research and drafted the manuscript. Z.S., H.W., and Y.T. performed the experiments. All authors analyzed and interpreted the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/2/eaao6724/DC1

section S1. Multiple methods to fabricate porous membranes with various pore sizes on different EMs.

section S2. The theoretical model agrees with the experimental critical pressure at a series of flow rates.

section S3. Deformation of EPM under one- or two-dimensional stretch.

section S4. Critical pressure change in various LGEPM systems.

section S5. Durability of the LGEPM system.

section S6. Uniformity of the EPMs during deformation.

fig. S1. The fabrication of EPM by CO2 laser cutting and its morphology.

fig. S2. The image of a whole silicone rubber membrane with nine pores in the center.

fig. S3. The fabrication of EPM by femtosecond laser cutting and its morphology.

fig. S4. The fabrication of porous PDMS membrane by Si replica molding method and its morphology.

fig. S5. The experimental and theoretical models of critical pressure of water transporting through the LGEPM at different flow rates.

fig. S6. Stress distribution of the elastomeric multiporous membrane.

fig. S7. Different pressure change via different deformation extent.

fig. S8. Critical pressure change of bare silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S9. Critical pressure change of silicone oil–infused silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S10. Critical pressure change of liquid paraffin–infused silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S11. Critical pressure of water passing through different gating liquids in two types of membrane materials.

fig. S12. The pressure of gas and liquid after cycles of stretch and relaxation.

fig. S13. Images of nonstretched and stretched EPMs.

fig. S14. Different pore size distribution leads to different gating performance.

movie S1. Preparation and mechanism of LGEPM system.

movie S2. One-dimensional stretching of EPM.

movie S3. Dynamic deformation of LGEPM.

movie S4. Dynamic gas and liquid separation process by LGEPM.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Yu C. M., Cao M. Y., Dong Z. C., Wang J. M., Li K., Jiang L., Spontaneous and directional transportation of gas bubbles on superhydrophobic cones. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3236–3243 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bussel H. P. L. H., Koene F. G. H., Mallant R. K. A. M., Dynamic model of solid polymer fuel cell water management. J. Power Sources 71, 218–222 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen F., Chu H.-S., Soong C.-Y., Yan W.-M., Effective schemes to control the dynamic behavior of the water transport in the membrane of PEM fuel cell. J. Power Sources 140, 243–249 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Günther A., Jensen K. F., Multiphase microfluidics: From flow characteristics to chemical and materials synthesis. Lab Chip 6, 1487–1503 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abolhasani M., Jensen K. F., Oscillatory multiphase flow strategy for chemistry and biology. Lab Chip 16, 2775–2784 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdallah R., Meille V., Shaw J., Wenn D., de Bellefon C., Gas–liquid and gas–liquid–solid catalysis in a mesh microreactor. Chem. Commun. 0, 372–373 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shang L., Cheng Y., Zhao Y., Emerging droplet microfluidics. Chem. Rev. 117, 7964–8040 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunther A., Khan S. A., Thalmann M., Trachsel F., Jensen K. F., Transport and reaction in microscale segmented gas–liquid flow. Lab Chip 4, 278–286 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel R., Willmott G., Kozak D., Roberts G. S., Anderson W., Groenewegen L., Glossop B., Barnett A., Turner A., Trau M., Quantitative sizing of nano/microparticles with a tunable elastomeric pore sensor. Anal. Chem. 83, 3499–3506 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillip W. A., Rzayev J., Hillmyer M. A., Cussler E. L., Gas and water liquid transport through nanoporous block copolymer membranes. J. Membrane Sci. 286, 144–152 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koros W. J., Zhang C., Materials for next-generation molecularly selective synthetic membranes. Nat. Mater. 16, 289–297 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J., Laoui T., Karnik R., Nanofluidic transport governed by the liquid/vapour interface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 317–323 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W. F., Liu N., Cao Y. Z., Lin X., Liu Y. N., Feng L., Superwetting porous materials for wastewater treatment: From immiscible oil/water mixture to emulsion separation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1600029 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J. J., Liu H. L., Jiang L., Membrane-based strategy for efficient ionic liquids/water separation assisted by superwettability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606544 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou L. L., Wang L., Wang N., Guo F., Liu J., Chen Y., Liu J., Zhao Y., Jiang L., Separation of organic liquid mixture by flexible nanofibrous membranes with precisely tunable wettability. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e334 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gin D. L., Noble R. D., Designing the next generation of chemical separation membranes. Science 332, 674–676 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian X., Jin H., Sainio J., Ras R. H. A., Ikkala O., Droplet and fluid gating by biomimetic janus membranes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 6023–6028 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y., Zhang M., Wang Z., Underwater superoleophobic membrane with enhanced oil–water separation, antimicrobial, and antifouling activities. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1500664 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu M., Wang S., Jiang L., Nature-inspired superwettability systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17036 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L., Boutilier M. S. H., Kidambi P. R., Jang D., Hadjiconstantinou N. G., Karnik R., Fundamental transport mechanisms, fabrication and potential applications of nanoporous atomically thin membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 509–522 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou X., Hu Y. H., Grinthal A., Khan M., Aizenberg J., Liquid-based gating mechanism with tunable multiphase selectivity and antifouling behaviour. Nature 519, 70–73 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao M., Li K., Dong Z., Yu C., Yang S., Song C., Liu K., Jiang L., Superhydrophobic “pump”: Continuous and spontaneous antigravity water delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4114–4119 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui X., Chen K., Xing H., Yang Q., Krishna R., Bao Z., Wu H., Zhou W., Dong X., Han Y., Li B., Ren Q., Zaworotko M. J., Chen B., Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene. Science 353, 141–144 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W., Shi Z., Zhang F., Liu X., Jin J., Jiang L., Superhydrophobic and superoleophilic PVDF membranes for effective separation of water-in-oil emulsions with high flux. Adv. Mater. 25, 2071–2076 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo S., Kim J.-H., Shin M., Park H., Kim J.-H., Lee S.-Y., Park S., Hierarchical multiscale hyperporous block copolymer membranes via tunable dual-phase separation. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadeghi I., Aroujalian A., Raisi A., Dabir B., Fathizadeh M., Surface modification of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes by corona air plasma for separation of oil/water emulsions. J. Membrane Sci. 430, 24–36 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrieu-Brunsen A., Micoureau S., Tagliazucchi M., Szleifer I., Azzaroni O., Soler-Illia G. J. A. A., Mesoporous hybrid thin film membranes with PMETAC@silica architectures: Controlling ionic gating through the tuning of polyelectrolyte density. Chem. Mater. 27, 808–821 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou X., Smart gating multi-scale pore/channel-based membranes. Adv. Mater. 28, 7049–7064 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson J. M., Gazin M., Laakso S., Haraldsson T., Malhotra-Kumar S., Mäki M., Goossens H., van der Wijngaart W., Active liquid degassing in microfluidic systems. Lab Chip 13, 4366–4373 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamo A., Heider P. L., Weeranoppanant N., Jensen K. F., Membrane-based, liquid–liquid separator with integrated pressure control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 10802–10808 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers J. A., Someya T., Huang Y., Materials and mechanics for stretchable electronics. Science 327, 1603–1607 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuk H., Zhang T., Parada G. A., Liu X. Y., Zhao X. H., Skin-inspired hydrogel–elastomer hybrids with robust interfaces and functional microstructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 12028 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekitani T., Noguchi Y., Hata K., Fukushima T., Aida T., Someya T., A rubberlike stretchable active matrix using elastic conductors. Science 321, 1468–1472 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips K. R., England G. T., Sunny S., Shirman E., Shirman T., Vogel N., Aizenberg J., A colloidoscope of colloid-based porous materials and their uses. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 281–322 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao X., Hu Y., Grinthal A., Wong T.-S., Mahadevan L., Aizenberg J., Adaptive fluid-infused porous films with tunable transparency and wettability. Nat. Mater. 12, 529–534 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan Y. J., Meng X. S., Li H. Y., Kuang S. Y., Zhang L., Wu Y., Wang Z. L., Zhu G., Stretchable porous carbon nanotube-elastomer hybrid nanocomposite for harvesting mechanical energy. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603115 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao X., Dunn S. S., Kim P., Duffy M., Alvarenga J., Aizenberg J., Fluorogel elastomers with tunable transparency, elasticity, shape-memory, and antifouling properties. Angew. Chem. 53, 4418–4422 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui J., Daniel D., Grinthal A., Lin K., Aizenberg J., Dynamic polymer systems with self-regulated secretion for the control of surface properties and material healing. Nat. Mater. 14, 790–795 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esch E. W., Bahinski A., Huh D., Organs-on-chips at the frontiers of drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 14, 248–260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeong G. S., Baek D.-H., Jung H. C., Song J. H., Moon J. H., Hong S. W., Kim I. Y., Lee S.-H., Solderable and electroplatable flexible electronic circuit on a porous stretchable elastomer. Nat. Commun. 3, 977 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou X., Zhang Y. S., Santiago G. T.-d., Alvarez M. M., Ribas J., Jonas S. J., Weiss P. S., Andrews A. M., Aizenberg J., Khademhosseini A., Interplay between materials and microfluidics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17016 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C., Wang Z., Suo Z., Flaw sensitivity of highly stretchable materials. Extreme Mech. Lett. 10, 50–57 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong T.-S., Kang S. H., Tang S. K. Y., Smythe E. J., Hatton B. D., Grinthal A., Aizenberg J., Bioinspired self-repairing slippery surfaces with pressure-stable omniphobicity. Nature 477, 443–447 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biot M. A., General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J. Appl. Phys. 12, 155–164 (1941). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purcell W. R., Capillary pressures - Their measurement using mercury and the calculation of permeability therefrom. J. Petrol. Technol. 1, 39–48 (1949). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bazyar H., Javadpour S., Lammertink R. G. H., On the gating mechanism of slippery liquid infused porous membranes. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1600025 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanani D. M., Fissell W. H., Roy S., Dubnisheva A., Fleischman A., Zydney A. L., Permeability–selectivity analysis for ultrafiltration: Effect of pore geometry. J. Membrane Sci. 349, 405–410 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/2/eaao6724/DC1

section S1. Multiple methods to fabricate porous membranes with various pore sizes on different EMs.

section S2. The theoretical model agrees with the experimental critical pressure at a series of flow rates.

section S3. Deformation of EPM under one- or two-dimensional stretch.

section S4. Critical pressure change in various LGEPM systems.

section S5. Durability of the LGEPM system.

section S6. Uniformity of the EPMs during deformation.

fig. S1. The fabrication of EPM by CO2 laser cutting and its morphology.

fig. S2. The image of a whole silicone rubber membrane with nine pores in the center.

fig. S3. The fabrication of EPM by femtosecond laser cutting and its morphology.

fig. S4. The fabrication of porous PDMS membrane by Si replica molding method and its morphology.

fig. S5. The experimental and theoretical models of critical pressure of water transporting through the LGEPM at different flow rates.

fig. S6. Stress distribution of the elastomeric multiporous membrane.

fig. S7. Different pressure change via different deformation extent.

fig. S8. Critical pressure change of bare silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S9. Critical pressure change of silicone oil–infused silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S10. Critical pressure change of liquid paraffin–infused silicone rubber membranes in a static stretching process.

fig. S11. Critical pressure of water passing through different gating liquids in two types of membrane materials.

fig. S12. The pressure of gas and liquid after cycles of stretch and relaxation.

fig. S13. Images of nonstretched and stretched EPMs.

fig. S14. Different pore size distribution leads to different gating performance.

movie S1. Preparation and mechanism of LGEPM system.

movie S2. One-dimensional stretching of EPM.

movie S3. Dynamic deformation of LGEPM.

movie S4. Dynamic gas and liquid separation process by LGEPM.