Key Points

Question

Do any of 4 oral combination analgesics (3 with different opioids and 1 opioid-free) provide more effective reduction of moderate to severe acute extremity pain in the emergency department (ED)?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 411 ED patients with acute extremity pain (mean score, 8.7 on the 11-point numerical rating scale), there was no significant difference in pain reduction at 2 hours. Mean pain scores decreased by 4.3 with ibuprofen and acetaminophen (paracetamol); 4.4 with oxycodone and acetaminophen; 3.5 with hydrocodone and acetaminophen; and 3.9 with codeine and acetaminophen.

Meaning

For adult ED patients with acute extremity pain, there were no clinically important differences in pain reduction at 2 hours with ibuprofen and acetaminophen or 3 different opioid and acetaminophen combination analgesics.

Abstract

Importance

The choice of analgesic to treat acute pain in the emergency department (ED) lacks a clear evidence base. The combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen (paracetamol) may represent a viable nonopioid alternative.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy of 4 oral analgesics.

Design, Settings, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial conducted at 2 urban EDs in the Bronx, New York, that included 416 patients aged 21 to 64 years with moderate to severe acute extremity pain enrolled from July 2015 to August 2016.

Interventions

Participants (104 per each combination analgesic group) received 400 mg of ibuprofen and 1000 mg of acetaminophen; 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen; 5 mg of hydrocodone and 300 mg of acetaminophen; or 30 mg of codeine and 300 mg of acetaminophen.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the between-group difference in decline in pain 2 hours after ingestion. Pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS), in which 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst possible pain. The predefined minimum clinically important difference was 1.3 on the NRS. Analysis of variance was used to test the overall between-group difference at P = .05 and 99.2% CIs adjusted for multiple pairwise comparisons.

Results

Of 416 patients randomized, 411 were analyzed (mean [SD] age, 37 [12] years; 199 [48%] women; 247 [60%] Latino). The baseline mean NRS pain score was 8.7 (SD, 1.3). At 2 hours, the mean NRS pain score decreased by 4.3 (95% CI, 3.6 to 4.9) in the ibuprofen and acetaminophen group; by 4.4 (95% CI, 3.7 to 5.0) in the oxycodone and acetaminophen group; by 3.5 (95% CI, 2.9 to 4.2) in the hydrocodone and acetaminophen group; and by 3.9 (95% CI, 3.2 to 4.5) in the codeine and acetaminophen group (P = .053). The largest difference in decline in the NRS pain score from baseline to 2 hours was between the oxycodone and acetaminophen group and the hydrocodone and acetaminophen group (0.9; 99.2% CI, −0.1 to 1.8), which was less than the minimum clinically important difference in NRS pain score of 1.3. Adverse events were not assessed.

Conclusions and Relevance

For patients presenting to the ED with acute extremity pain, there were no statistically significant or clinically important differences in pain reduction at 2 hours among single-dose treatment with ibuprofen and acetaminophen or with 3 different opioid and acetaminophen combination analgesics. Further research to assess adverse events and other dosing may be warranted.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02455518

This randomized clinical trial compares the efficacy of 4 oral combination analgesics among adult patients treated for moderate to severe acute extremity pain at 2 urban emergency departments in the United States.

Introduction

The United States is facing an opioid epidemic with almost 500 000 individuals dying from drug overdoses since 2000. Despite the epidemic, opioid analgesics remain the first-line treatment for moderate to severe acute pain in the emergency department (ED). Based on data from 2006-2010, opioids were prescribed for 18.7% of ED discharges.

Acute extremity injuries are a common painful presenting condition seen in emergency practice. Depending on the degree of discomfort, patients are often treated with a single dose of an oral analgesic while awaiting further care. There are many analgesic options, but evidence to inform clinical choice in this context is sparse.

Relatively few ED studies have compared the efficacy of the 3 most commonly used opioid analgesics in the ED and none has compared them in a single study. Although opioids are considered to provide stronger analgesia than nonopioid analgesics, 1 ED-based study found that adding combination oxycodone and acetaminophen to naproxen did not improve pain relief at 1 week in patients with acute low back pain. Several postsurgical studies have found combination nonopioids to be as effective as a combination of codeine and acetaminophen.

Changing prescribing practices is an important step in addressing the opioid epidemic and its adverse effects on US communities, and research suggests that even short-term opioid use may confer a predisposition to opioid dependence.

The objective of this study was to compare the degree of pain reduction at 2 hours after ingestion of 4 oral combination analgesics. One of the analgesics was opioid-free, whereas the other 3 contained an opioid, and all 4 were combined with acetaminophen (paracetamol).

Methods

Overview

In this randomized double-blind clinical trial, adult patients were enrolled during an ED visit for acute extremity pain. Patients received a single dose of an oral combination analgesic (ibuprofen and acetaminophen, oxycodone and acetaminophen, hydrocodone and acetaminophen, or codeine and acetaminophen) and were asked to rate their pain intensity using a verbal numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 at 1 and 2 hours following ingestion. The Albert Einstein College of Medicine institutional review board provided ethical oversight and study approval. All participants provided written informed consent in either English or Spanish. Data were collected between July 2015 and August 2016. The protocol and statistical analysis plan as well as additional post hoc analyses appear in Supplement 1.

Study Setting

This study was conducted in 2 EDs of the Montefiore Medical Center. The Moses division is an urban teaching hospital with more than 100 000 adult visits annually, and is located in the west Bronx, New York. The Weiler division is a community hospital with more than 70 000 adult visits annually, and is located in the east Bronx, New York. Salaried, trained, full-time, bilingual (English and Spanish) research associates staffed the ED 24 hours per day, 7 days per week during the accrual period.

Participant Selection

Patients were considered for inclusion if they were adults aged 21 years through 64 years who presented to the ED for management of acute extremity pain, which was defined as pain originating distal to and including the shoulder joint in the upper extremities and distal to and including the hip joint in the lower extremities. Eligible patients were required to have a clinical indication for radiological imaging (based on judgment of the ED attending physician) that would provide a built-in delay during which most patients would be able to provide 1- and 2-hour pain scores. The need for imaging also was considered to be a proxy for more severe injury, thus increasing the likelihood that an oral opioid analgesic might be an appropriate choice for pain relief in the judgment of the ED attending physician.

Patients were excluded for the following reasons: past use of methadone; presence of a chronic condition requiring frequent pain management such as sickle cell disease, fibromyalgia, or any neuropathy; history of an adverse reaction to any of the study medications; had taken opioids within the past 24 hours; had taken ibuprofen or acetaminophen within the past 8 hours; pregnant according to either a urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin test; breastfeeding (per patient report); history of peptic ulcer disease; report of any prior use of recreational narcotics; medical condition that might affect metabolism of opioid analgesics, acetaminophen, or ibuprofen such as hepatitis, renal insufficiency, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, Addison disease, or Cushing disease; presence of any medicine that might interact with 1 of the study medications (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants).

Interventions

After randomization, all patients rated their pain immediately before taking the study analgesic and again both 1 and 2 hours after taking the medication while remaining in the ED. Patients discharged prior to 2 hours were reached at the 2-hour time point via a previously confirmed cell phone number. Patients who required rescue analgesics (based on the discretion of the ED attending physician) received an unblinded 5-mg dose of oral oxycodone, which could be administered at any point during the 2-hour study period. Additional analgesia could also be administered based on the discretion of the ED attending physician.

All patients received 3 identical, opaque capsules containing a total amount of 400 mg of ibuprofen and 1000 mg of acetaminophen; 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen; 5 mg of hydrocodone and 300 mg of acetaminophen; or 30 mg of codeine and 300 mg of acetaminophen. Three capsules were used because the amount of analgesic administered was more than would fit into either 1 or 2 blinded capsules small enough for patients to comfortably swallow. All study analgesics were taken under direct observation to confirm ingestion.

Randomization and Blinding

A research pharmacist performed the stratified randomization in blocks of 8 using an online randomization plan generator. The pharmacist masked the analgesics by placing them into identical unmarked opaque capsules, which were packed with small amounts of lactose to equalize weight and then sealed. The pharmacist created research packets, each with 3 tablets containing the masked investigational medication. Research packets were removed by nurses from the Pyxis automated medical dispensing system located in the ED, and administered to the study patients. The randomized allocation schedule could only be accessed by the research pharmacist, who had no role in dispensing the medication.

Outcome Measures

Pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point NRS in which a score of 0 indicates no pain and a score of 10 indicates the worst possible pain. The NRS is commonly used in EDs for assessing initial pain at triage and changes in pain levels during evaluation and treatment. The primary outcome was the between-group difference in mean change in NRS pain score among patients receiving 1 of the 4 combination analgesics, measured from the time before ingestion of the study medication to 2 hours later. Secondary outcomes included between-group differences in mean NRS scores at 1 hour and responses to a 4-point Likert scale rating pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. The data collection instrument went through several iterations and the Likert scale was not included in the final data collection instrument. The minimum clinically important difference was defined as a mean NRS pain score of 1.3 based on the standard previously derived and independently validated definition.

Additional outcomes not described in the original protocol included the proportion of patients receiving rescue analgesics, the total amount of analgesics in morphine equivalent units, and an analysis of patients with either documented fractures or a pain score of 10. Demographic characteristics were collected to describe the population from which the sample was drawn.

Sample Size Calculation

The following parameters were used to calculate the sample size: an overall 2-sided significance level of .05 (.008 for all pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni correction), 80% power, between-group difference for change in mean NRS pain score of 1.3, and a within-group SD of 2.6 based on estimates of variability from our prior work. Using these parameters, we estimated that 100 patients would be needed per group for a total of 400 patients.

Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. All patients who were enrolled and met inclusion criteria were analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. Those with missing NRS data (1 per group) had their missing values calculated by imputation. Details of the imputation analysis appear in Supplement 2. The primary analysis was a 1-way analysis of variance testing the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the effect of the medications on mean change in pain from baseline to 2 hours with a significance level of .05. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust the overall significance level of .05 to account for multiple comparisons when all pairwise mean differences in pain were compared, resulting in 99.2% CIs.

Four patients were missing 1, 2, or 3 NRS scores (Figure). Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to keep these patients in the intention-to-treat analysis. In a post hoc analysis, NRS scores at 2 hours were imputed for patients who received rescue medication. This was done to address bias that could be introduced if receipt of rescue medication differed by treatment group. If the distributions differ, the 2-hour NRS scores would reflect the combined effect of the initial and rescue analgesics, thus attenuating differences between treatment groups. The imputation model included baseline and 1-hour NRS scores, receipt of rescue analgesia, language of interview, age, sex, site, ethnicity, treatment group, diagnosis, and nonpharmacological interventions. For all analyses, we used SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM) and Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp).

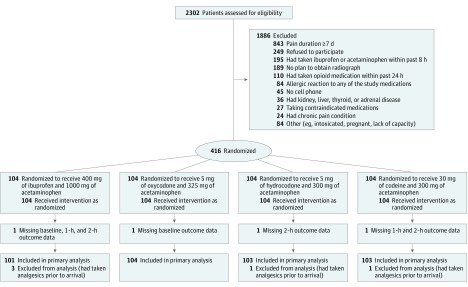

Figure. Flow of Patients Through Acute Extremity Pain Trial.

Results

During a 13-month period beginning in July 2015, 416 patients were randomized (Figure). Of these, 5 patients received nonopioid analgesia within the past 8 hours (an exclusion criterion) and were inadvertently randomized and later excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 411, 48% were female, 60% were Latino, and 31% were black. Baseline characteristics were similar in all groups (Table 1). Baseline pain intensity was initially high (mean NRS pain score, 8.7 [SD, 1.3]) and did not differ between groups (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Ibuprofen and Acetaminophena |

Oxycodone and Acetaminophenb |

Hydrocodone and Acetaminophenc |

Codeine and Acetaminophend |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 101 | 104 | 103 | 103 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 54 (54) | 50 (48) | 51 (50) | 44 (43) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 37 (11) | 37 (12) | 37 (13) | 37 (12) |

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | ||||

| Sprain or strain | 64 (63) | 66 (64) | 59 (57) | 67 (65) |

| Extremity fracture | 21 (21) | 23 (22) | 21 (20) | 24 (23) |

| Muscle pain | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 12 (12) | 7 (7) |

| Contusion | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Nonpharmacological ED interventions, No. (%) | ||||

| Elastic bandage | 39 (39) | 37 (36) | 23 (22) | 36 (35) |

| Splint | 12 (12) | 20 (19) | 18 (18) | 10 (10) |

| Cast | 10 (10) | 14 (14) | 6 (6) | 11 (11) |

| Ice | 7 (7) | 11 (11) | 10 (10) | 4 (4) |

| Other | 11 (11) | 5 (5) | 15 (15) | 16 (16) |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

Patients received 400 mg of ibuprofen and 1000 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 5 mg of hydrocodone and 300 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 30 mg of codeine and 300 mg of acetaminophen.

Table 2. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores and Decline in Pain Scores by Treatment Group.

| NRS Pain Score, Mean (95% CI)a | P Valuef | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen and Acetaminophenb |

Oxycodone and Acetaminophenc |

Hydrocodone and Acetaminophend |

Codeine and Acetaminophene |

||

| No. of patientsg | 101 | 104 | 103 | 103 | |

| Primary end point: decline in score to 2 h | 4.3 (3.6 to 4.9) | 4.4 (3.7 to 5.0) | 3.5 (2.9 to 4.2) | 3.9 (3.2 to 4.5) | .053 |

| Baseline score | 8.9 (8.5 to 9.2) | 8.7 (8.3 to 9.0) | 8.6 (8.3 to 9.0) | 8.6 (8.2 to 8.9) | .47 |

| Score at 1 h | 5.9 (5.3 to 6.6) | 5.5 (4.9 to 6.2) | 6.2 (5.6 to 6.9) | 5.9 (5.2 to 6.5) | .25 |

| Score at 2 h | 4.6 (3.9 to 5.3) | 4.3 (3.6 to 5.0) | 5.1 (4.5 to 5.8) | 4.7 (4.0 to 5.4) | .13 |

| Decline in score to 1 h | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.5) | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.7) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.0) | 2.7 (2.1 to 3.3) | .13 |

Pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point NRS in which a score of 0 indicates no pain and a score of 10 indicates the worst possible pain.

Patients received 400 mg of ibuprofen and 1000 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 5 mg of hydrocodone and 300 mg of acetaminophen.

Patients received 30 mg of codeine and 300 mg of acetaminophen.

Calculated using analysis of variance.

One patient in each group had imputed NRS data.

Pain intensity declined over time in all treatment groups (Table 2). At 2 hours, the mean NRS pain score decreased by 4.3 (95% CI, 3.6 to 4.9) in the ibuprofen and acetaminophen group; by 4.4 (95% CI, 3.7 to 5.0) in the oxycodone and acetaminophen group; by 3.5 (95% CI, 2.9 to 4.2) in the hydrocodone and acetaminophen group; and by 3.9 (95% CI, 3.2 to 4.5) in the codeine and acetaminophen group. The overall test of the null hypothesis that there is no difference in change in pain by treatment group from baseline to 2 hours (the primary outcome measure) was not statistically significant (P = .053). There was also no significant difference at 1 hour (P = .13) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the comparisons in mean change in pain between each pair of analgesics. None of the differences between analgesics was statistically significant or met the a priori definition of a minimally clinically important difference in mean NRS pain score of 1.3.

Table 3. Between-Group Difference in Mean Change in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores.

| Comparison | Between-Group Difference in Mean Change in NRS Pain Score (99.2% CI)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| From Baseline to 1 h | From Baseline to 2 h | |

| Ibuprofen and acetaminophen vs oxycodone and acetaminophen | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) | −0.1 (−1.0 to 0.8) |

| Ibuprofen and acetaminophen vs hydrocodone and acetaminophen | 0.5 (−0.3 to 1.3) | 0.8 (−0.2 to 1.7) |

| Ibuprofen and acetaminophen vs codeine and acetaminophen | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.0) | 0.4 (−0.6 to 1.3) |

| Oxycodone and acetaminophen vs hydrocodone and acetaminophen | 0.7 (−0.1 to 1.5) | 0.9 (−0.1 to 1.8) |

| Oxycodone and acetaminophen vs codeine and acetaminophen | 0.4 (−0.4 to 1.2) | 0.5 (−0.4 to 1.4) |

| Hydrocodone and acetaminophen vs codeine and acetaminophen | −0.3 (−1.1 to 0.5) | −0.4 (−1.3 to 0.6) |

Indicates mean change in pain of first analgesic minus mean change in pain from second analgesic. Pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point NRS in which a score of 0 indicates no pain and a score of 10 indicates the worst possible pain.

Seventy-three patients (17.8%) received rescue analgesics within the 2-hour period (Table 4). The distribution of receipt of rescue analgesia was not statistically significant, but the estimates varied by as much as 9% (oxycodone and acetaminophen vs codeine and acetaminophen). Results of the analysis with multiple imputations of the NRS pain scores for patients who received rescue analgesics were nearly identical to the analysis without imputation (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). There were no clinically important or statistically significant differences in efficacy when these post hoc analyses were performed.

Table 4. Rescue Analgesic and Total Morphine Equivalent Units Received Within 2 Hours.

| Ibuprofen and Acetaminophen |

Oxycodone and Acetaminophen |

Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen |

Codeine and Acetaminophen |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 101 | 104 | 103 | 103 | |

| Received rescue analgesic, No. (%) | 18 (17.8) | 14 (13.5) | 18 (17.5) | 23 (22.3) | .42 |

| Type of rescue analgesic received, No. (%) | |||||

| Oxycodone | 17 (16.8) | 13 (12.5) | 17 (16.5) | 22 (21.4) | .55 |

| Morphine | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | |

| Tramadol | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Analgesic dose in morphine equivalent units, mean (SD)a | |||||

| Initial | 0 (0) | 7.5 (0) | 5.0 (0) | 4.5 (0) | NAb |

| Rescue | 1.6 (3.5) | 1.1 (2.7) | 1.7 (3.2) | 2.0 (3.4) | .27 |

| Total | 1.6 (3.5) | 8.6 (2.7) | 6.7 (3.2) | 6.5 (3.4) | <.001 |

Calculated based on the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Opioid Oral Morphine Milligram Equivalent conversion factor table: 1.5 for oxycodone; 1.0 for hydrocodone; 0.15 for codeine; 0.1 for tramadol; and 3.0 for intravenous morphine.

Statistical test cannot be calculated.

The amount of rescue analgesia received in morphine equivalent units was not significantly different across groups (Table 4). The total amount of opioid was significantly associated with treatment group. One patient in the ibuprofen and acetaminophen group received 6 mg of intravenous morphine and 1 patient in the codeine and acetaminophen group received 4 mg of intravenous morphine.

We conducted a post hoc subset analysis to assess whether any analgesic was more effective for severe pain among patients who either (1) rated their initial pain as a score of 10 on the NRS or (2) had a documented fracture on radiological imaging. The results were similar to those from the entire sample. There were no statistically significant or clinically important between-group differences (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

Among patients presenting to the ED with acute extremity pain, none of 4 different combination analgesics, 1 of which was opioid-free, resulted in greater pain relief after 2 hours. The largest difference in decline in mean NRS pain score between any 2 treatments was 0.9 at the 2-hour time point, a difference that was not statistically significant and was less than 1.3, which is a commonly used criterion to define minimal clinically important difference in pain. The findings support the inference that there are no clinically meaningful differences between the analgesic effects of these 4 analgesics and suggest that a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen represents an alternative to oral opioid analgesics for the treatment of acute extremity pain in the ED.

Relatively few studies have made direct comparison of commonly used oral opioid analgesics for the treatment of acute pain. These studies are difficult to compare because they used varying doses, had different outcomes, and had methodological limitations, including small sample sizes and substantial loss to follow-up. However, the results generally support the inference that opioid analgesics have similar efficacy.

The combination of nonopioids makes clinical sense because of the potential to increase analgesic efficacy through different modes of action. However, there are relatively few studies of the relative efficacy of combination nonopioid oral analgesics vs oral opioids; all were postoperative or dental studies that compared a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen vs codeine and acetaminophen. None found any dose of codeine (30 mg or 60 mg) to be superior to the combination of 400 mg of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in doses ranging from 325 mg to 1000 mg. One ED-based study compared a combination nonopioid vs oxycodone. All patients received ibuprofen and acetaminophen. There were 3 groups in the study (group 1 received 1000 mg of acetaminophen, 400 mg of ibuprofen, and 200 mg of thiamine; group 2 received 1000 mg of acetaminophen, 400 mg of ibuprofen, and 60 mg of codeine; and group 3 received 1000 mg of acetaminophen, 400 mg of ibuprofen, and 10 mg of oxycodone). At 30 minutes, there was no difference in analgesic efficacy among the groups. The evidence from these studies suggests that the lack of greater pain reduction with opioid analgesics over the combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen found in the current study may generalize beyond the treatment of acute extremity pain. In contrast to earlier research, the current study offered a direct comparison of the most commonly prescribed oral opioids used in the ED and a nonopioid combination.

The idea that nonopioid analgesics have less analgesic efficacy and that there are differences between the opioids can be found in the World Health Organization pain ladder that has guided clinicians in the treatment of cancer and noncancer pain since 1986. Depending on the intensity of pain, nonopioids (eg, ibuprofen, acetaminophen) are prescribed first, and then, as necessary, mild opioids (eg, codeine), followed by strong opioids (eg, hydrocodone, oxycodone). The findings of the current study coupled with the existing literature do not support these distinctions among the oral analgesics for the treatment of acute extremity pain.

In light of the substantial increase in prescription opioid-related overdoses and deaths, the widespread use of oral opioids has been questioned. Overuse and misuse of opioid analgesics in the community is an important contributor to the opioid epidemic; however, the current study only focused on treatment in the ED. If a nonopioid combination analgesic provides comparable pain relief to that obtained by oral opioids commonly used in the ED, it is possible that physicians may be more likely to discharge patients and prescribe the same nonopioid combination analgesics. In addition, patients might be more accepting of that analgesic so long as it provides ample pain relief when used in the ED. This change in prescribing habit could potentially help mitigate the ongoing opioid epidemic by reducing the number of people initially exposed to opioids and the subsequent risk of addiction, as shown in a recent study that found long-term opioid use was significantly higher among patients treated by high-intensity ED opioid prescribers than among patients treated by low-intensity ED opioid prescribers.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the follow-up time was limited to 2 hours. Although a more prolonged follow-up would have provided additional information, the goal was to determine if a single dose of an analgesic would provide superior pain relief for patients while in the ED. In addition, the enrolled patient population included those generally seen in a fast-track setting, in which patients are discharged quickly with minimal or no testing. Whether the duration of analgesia differs among the analgesics is unknown, although the half-lives are similar and range from approximately 3 hours to 4 hours.

Second, the oral opioids used in this study may be dispensed as 1 or 2 tablets at a time. We chose to administer the equivalent of 1 tablet. There are no nationally representative data sets that allow estimation of usual analgesic dose in the ED setting. For example, the National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey has medication and route information but not dose information. The dosage used in this study represents common practice among physicians from a variety of training programs and institutions. The dose of opioid chosen also reflects prior studies, which have shown effective pain relief at the identical dosages used in the current study. In addition, there was concern that many physicians would not refer patients for enrollment if it meant administering higher doses of opioids because most patients were expected to be discharged quickly and the rescue analgesic was predefined to be 5 mg of oxycodone.

Third, approximately 18% of patients received rescue analgesia, and this may have driven results toward the null. However, additional analyses imputing NRS pain score for patients who received rescue analgesics also showed no clinically important or statistically significant difference.

Fourth, adverse effect information was not collected. Such information could influence the choice of analgesic prescribed, especially if one group had significantly more adverse effects than another group. Significant adverse effects were not expected to occur during the 2-hour follow-up of this study. However, a similar ED-based study lasting 90 minutes had an incidence of adverse events of 1.6% in the codeine group, 3.3% in the nonopioid group, and 16.9% in the oxycodone group, with lightheadedness accounting for 70% of adverse events in the oxycodone group. In that study, the amount of oxycodone and codeine administered was double the dose used in the current study and thus is not directly comparable.

Fifth, the nonopioid combination analgesic used requires 2 separate analgesics (ibuprofen and acetaminophen) and this could represent a barrier because there is no single tablet available in the United States that combines these 2 drugs. A combination product of ibuprofen and acetaminophen (paracetamol) in a single tablet is available for patients in Australia and New Zealand, though in smaller dosages than were used in this study.

Conclusions

For patients presenting to the ED with acute extremity pain, there were no statistically significant or clinically important differences in pain reduction at 2 hours among single-dose treatment with ibuprofen and acetaminophen or with 3 different opioid and acetaminophen combination analgesics. Further research to assess adverse events and other dosing may be warranted.

Trial protocol

Imputation process

eTable 1. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores and Decline in Pain Score by Treatment Groups with Imputation of NRS scores for Patients Who Received Rescue Analgesia

eTable 2. Between-Group Difference in Mean Change in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores with Imputation of NRS scores for Patients Who Received Rescue Analgesia

eTable 3. Post hoc Analysis of Subset of Patients with Severe Pain (NRS = 10 or Documented Fracture)

References

- 1.Burke DS. Forecasting the opioid epidemic. Science. 2016;354(6312):529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kea B, Fu R, Lowe RA, Sun BC. Interpreting the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: United States emergency department opioid prescribing, 2006-2010. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(2):159-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang AK, Bijur PE, Holden L, Gallagher EJ. Comparative analgesic efficacy of oxycodone/acetaminophen versus hydrocodone/acetaminophen for short-term pain management in adults following ED discharge. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(11):1254-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang AK, Bijur PE, Lupow JB, Gallagher EJ. Comparative analgesic efficacy of oxycodone/acetaminophen vs codeine/acetaminophen for short-term pain management following ED discharge. Pain Med. 2015;16(12):2397-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang AK, Bijur PE, Munjal KG, Gallagher EJ. Randomized clinical trial of hydrocodone/acetaminophen versus codeine/acetaminophen in the treatment of acute extremity pain after emergency department discharge. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, Black C, Roberts A. Comparison of oxycodone and hydrocodone for the treatment of acute pain associated with fractures: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):282-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turturro MA, Paris PM, Yealy DM, Menegazzi JJ. Hydrocodone versus codeine in acute musculoskeletal pain. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(10):1100-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, et al. . Naproxen with cyclobenzaprine, oxycodone/acetaminophen, or placebo for treating acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1572-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(7):1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels SE, Goulder MA, Aspley S, Reader S. A randomised, five-parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial comparing the efficacy and tolerability of analgesic combinations including a novel single-tablet combination of ibuprofen/paracetamol for postoperative dental pain. Pain. 2011;152(3):632-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, Porter G. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(3):472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, Porter G. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(12):3792-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler MM, Ancona RM, Beauchamp GA, et al. . Emergency department prescription opioids as an initial exposure preceding addiction. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):202-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(4):390-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holdgate A, Asha S, Craig J, Thompson J. Comparison of a verbal numeric rating scale with the visual analogue scale for the measurement of acute pain. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2003;15(5-6):441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todd KH. Clinical versus statistical significance in the assessment of pain relief. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(4):439-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedgwick P. Multiple hypothesis testing and Bonferroni’s correction. BMJ. 2014;349:g6284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forbes JA, Bates JA, Edquist IA, et al. . Evaluation of two opioid-acetaminophen combinations and placebo in postoperative oral surgery pain. Pharmacotherapy. 1994;14(2):139-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litkowski LJ, Christensen SE, Adamson DN, Van Dyke T, Han SH, Newman KB. Analgesic efficacy and tolerability of oxycodone 5 mg/ibuprofen 400 mg compared with those of oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg and hydrocodone 7.5 mg/acetaminophen 500 mg in patients with moderate to severe postoperative pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose, parallel-group study in a dental pain model. Clin Ther. 2005;27(4):418-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palangio M, Morris E, Doyle RT Jr, Dornseif BE, Valente TJ. Combination hydrocodone and ibuprofen versus combination oxycodone and acetaminophen in the treatment of moderate or severe acute low back pain. Clin Ther. 2002;24(1):87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palangio M, Wideman GL, Keffer M, et al. . Combination hydrocodone and ibuprofen versus combination oxycodone and acetaminophen in the treatment of postoperative obstetric or gynecologic pain. Clin Ther. 2000;22(5):600-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raffa RB. Pharmacology of oral combination analgesics: rational therapy for pain. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(4):257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson CL. Effectiveness of the World Health Organization cancer pain relief guidelines: an integrative review. J Pain Res. 2016;9:515-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gostin LO, Hodge JG Jr, Noe SA. Reframing the opioid epidemic as a national emergency. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Imputation process

eTable 1. Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores and Decline in Pain Score by Treatment Groups with Imputation of NRS scores for Patients Who Received Rescue Analgesia

eTable 2. Between-Group Difference in Mean Change in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Scores with Imputation of NRS scores for Patients Who Received Rescue Analgesia

eTable 3. Post hoc Analysis of Subset of Patients with Severe Pain (NRS = 10 or Documented Fracture)