Abstract

Interfaces between organelles are emerging as critical platforms for many biological responses in eukaryotic cells. In yeast, the ERMES complex is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–mitochondria tether composed of four proteins, three of which contain a SMP (synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial-lipid binding protein) domain. No functional ortholog for any ERMES protein has been identified in metazoans. Here, we identified PDZD8 as an ER protein present at ER-mitochondria contacts. The SMP domain of PDZD8 is functionally orthologous to the SMP domain found in yeast Mmm1. PDZD8 was necessary for the formation of ER-mitochondria contacts in mammalian cells. In neurons, PDZD8 was required for calcium ion (Ca2+) uptake by mitochondria after synaptically induced Ca2+-release from ER and thereby regulated cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics. Thus, PDZD8 represents a critical ER-mitochondria tethering protein in metazoans. We suggest that ER-mitochondria coupling is involved in the regulation of dendritic Ca2+ dynamics in mammalian neurons.

Contacts between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the mitochondria are thought to represent a signaling hub where Ca2+ and lipid exchange can occur between these two organelles (1, 2). In addition, changes in the extent of ER-mitochondria contacts have been reported in various models of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (3–5). Several proteins that are enriched at ER-mitochondria in mammalian cells, including Mitofusin2, have been proposed to play a role in modulating the contacts between these organelles (6–9). However, mutation of the genes encoding these proteins has complex and sometimes contradictory phenotypic consequences on ER-mitochondria contacts (10–12).

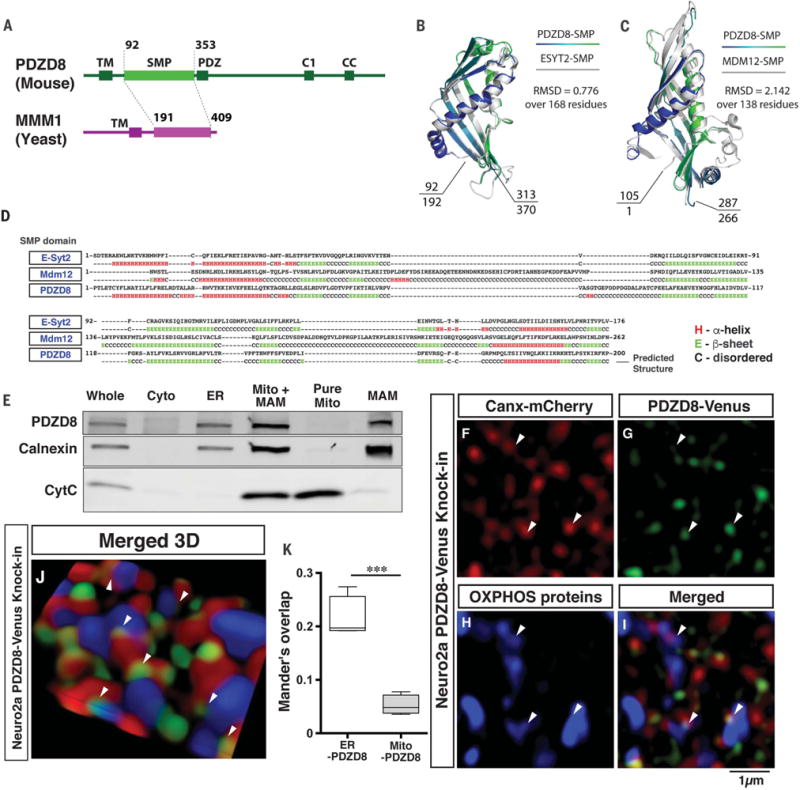

The ER–mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES) complex functions as a tether between the ER and mitochondria in budding yeast (1). Three out of four ERMES complex proteins (Mmm1, Mdm12, and Mdm34) contain an SMP domain. Trans-heterodimerization of SMP domains within proteins such as extended synaptotagmin 2 (E-syt2) was recently proposed to participate in lipid exchange between ER and plasma membrane (13–15). Based on low levels of amino acid sequence homology, no ERMES complex ortholog has been identified in metazoans (16, 17) (fig. S1, C to E). Recent bioinformatics approaches predicted the existence of several SMP domain–containing proteins in metazoans (18, 19), including a protein of unknown function called PDZD8. A search of the PDB (Protein Data Bank) using the Phyre2 protein modeling server showed that the SMP-containing proteins E-syt2 (PDB code 4P42) and the ERMES complex protein Mdm12 (PDB code 5gyk), respectively, are similar to residues 92 to 367 and 105 to 287 of PDZD8 with >99.8% confidence [expected value of <10−26 in hidden Markov models (HMM)-HMM–based lightning-fast iterative sequence search (HHBLITS)] (Fig. 1, B and C). Furthermore, there is a high correspondence in the secondary structure elements (SSEs) of the predicted SMP domain of PDZD8 and the actual SSEs in the SMP domains of E-syt2 and Mdm12 (Fig. 1D). These results strongly suggest that PDZD8 is an SMP-containing protein. We therefore explored the possibility that PDZD8 constitutes a structural and functional ortholog of the ERMES component Mmm1.

Fig. 1. The SMP domain–containing PDZD8 is a mammalian ortholog of yeast Mmm1 and is present at ER-mitochondria contact sites.

(A) Domain organization of S. cerevisiae Mmm1 and mammalian PDZD8 proteins. (B and C) Superimposition of Phyre2 structural homology models for the SMP domains of PDZD8 over the crystal structures of mammalian E-syt2 (192 to 370 amino acids) (B) or S. cerevisiae Mdm12 (1 to 266 amino acids) (C). Root mean square deviation of atomic positions (RMSD) values show higher similarity with E-syt2 than Mdm12 (see fig. S1). (D) Predicted secondary structure of the SMP domain of PDZD8 (mouse) alignment with E-syt2 (human) and Mdm12 (S. cerevisiae) suggests a high degree of structural homology at the secondary structural level. Expected value = 3.5 × 10−26 (PDZD8 versus E-syt2). (E) Western blots of subcellular fractionation from HEK293T cells demonstrates the presence of endogenous PDZD8 in ER and MAM fractions. MAM fraction was isolated using a Percoll gradient and immunoblotted with antibodies to PDZD8, calnexin (for ER and MAM fractions), and cytochrome C (for mitochondrial fraction). (F to K) We generated a mouse Neuro2a (N2a) cell line by knockin of Venus in the endogenous Pdzd8 genomic locus to create a C-terminal fusion PDZD8-Venus fusion protein by transfecting with a plasmid expressing guide RNA targeted to PDZD8 sequence and Cas9, together with the donor plasmid (see fig. S6A for details). N2a cells that had stably integrated the donor plasmid were enriched by selection with 600 μg/ml Geneticin (G418 sulfate). The targeted cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Canx-mCherry (ER marker) and stained with antibodies to red fluorescent protein, GFP, and OXPHOS (oxidative phosphorylation) complex (mitochondrial marker). The stained cells were imaged with super-resolution microscopy (3D SIM). Images from a single plane [(F) to (I)] and a 3D reconstructed image (J) are shown. Arrowheads indicate the localization of PDZD8 at ER-mitochondria contact sites. (K) Analysis of colocalization between ER and PDZD8-Venus, and mitochondria and PDZD8-Venus using Mander’s overlap demonstrates PDZD8 localization with ER but not mitochondria. Data are from four cells in each group. ***P < 0.0005, Student’s t test.

Investigating the functional similarity between the SMP domains of Mmm1 and PDZD8

Mmm1 and PDZD8 contain an N-terminal transmembrane domain followed by an SMP domain, although PDZD8 has a longer C-terminal extension, including predicted PDZ, C1, and coil-coiled (CC) domains (Fig. 1A). In addition, Mmm1 is the only SMP-containing ERMES subunit localized to the ER in yeast (1, 20). Modeling indicated that the predicted SMP domains of PDZD8 and Mmm1 are structurally homologous with the SMP domains of E-syt2 and Mdm12 (Fig. 1, B and C, and fig. S1, A to C). To determine whether PDZD8 and Mmm1 are functionally homologous, we first expressed PDZD8 in yeast and tested its localization. PDZD8-Venus colocalized with yeast ER-resident protein Pho88, suggesting conserved and functional ER targeting of PDZD8 (fig. S2A).

Next, we investigated whether PDZD8 could functionally complement for Mmm1 function. Deletion of the MMM1 gene resulted in critical cellular and mitochondrial defects, including (i) the collapse of the mitochondrial tubular network into one or two large spherical structures, (ii) severe mitochondrial inheritance defects during cell division, and (iii) the complete loss of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (figs. S3 to S5) (21, 22). Because mmm1Δ cells rapidly accumulate suppressor mutations (23), we used a plasmid shuffling experimental strategy to replace endogenous MMM1 with genes of interest to avoid adaptation to the loss of MMM1 (fig. S3A). Briefly, we transformed a low-copy plasmid bearing genes of interest, including PDZD8 variants under the MMM1 promoter and a URA3 selectable marker (pRESC), into heterozygous mmm1Δ/MMM1 diploid cells expressing mitochondria-targeted Cit1p-mCherry. Haploid cells containing the rescue plasmid and a deletion of MMM1 (pRESC + mmm1Δ) were generated from the diploids and analyzed for functional rescue. Finally, to exclude the possibility of genomic adaptation, we tested whether the recovered phenotype could be reversed by loss of the rescue plasmid through 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) incubation, which is toxic to cells expressing URA3 and selects for spontaneous loss of pRESC (fig. S3A).

First, we attempted to rescue the mmm1Δ with the truncated form of PDZD8 containing the transmembrane and SMP domains (PDZD8TM-SMP) or the SMP domain-swapped MMM1 with a PDZD8-SMP domain (pMMM1-SMPPDZD8_full) (fig. S3, B and C). However, these proteins were not able to restore the mitochondrial morphology, inheritance, and mtDNA maintenance defects, unlike wild-type MMM1 (fig. S3, B and C).

Structural alignment of the SMP domains of Mmm1 and PDZD8 or Mdm12 revealed that the only major differences in SSEs reside within the two loops of the first β sheet (L1 and L2 for Pdzd8 and L1 for Mdm12) (fig. S1D). Thus, we next tested an MMM1 SMP-domain swap with PDZD8 that spared the original L1 and L2 MMM1-SMP regions (pMMM1-SMPPDZD8+L1L2) (fig. S4). Surprisingly, expression of the yeast MMM1/mouse PDZD8 chimera containing L1 and L2 or MMM1/Mdm12 chimera containing L1 restored (i) retention of mtDNA in ~25% of cells examined (fig. S4, D and E), (ii) mitochondrial inheritance in ~50% of the cells examined (fig. S4, D and F), and (iii) normal tubular mitochondrial morphology in ~30% of the organelles examined (fig. S4, D and G; see fig. S5 for the development of the mitochondrial morphology quantification method). Plasmid loss by 5-FOA reversed the rescue phenotype (fig. S4).

Despite containing the original L1 and L2 loops from MMM1, the SMP domain of the rescue construct (pMMM1-SMPPDZD8+L1L2) consisted of >75% of the primary sequence found in PDZD8, with only ~15% sequence identity to MMM1. Moreover, although the rescue with pMMM1-SMPPDZD8+L1L2 was partial, it was similar to that observed when the SMP domain of Mmm1 was replaced with the SMP domain of another ERMES protein, Mdm12 (fig. S4). Thus, the SMP domain of metazoan PDZD8 is as functional as a yeast SMP domain.

Thus, SMP domains from yeast MMM1 represent a structural and functional ortholog of the SMP domain of metazoans PDZD8. Additionally, we find that functional homology between MMM1 and PDZD8 SMP domains does not extend to the L1 and L2 loops. The L1 and L2 loops are poorly conserved even among the Ascomycota, such as Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Magnaporthe oryzae, and Neurospora crassa. Thus, variability in the L1 and L2 loops may lend specificity of SMP domains to a particular functional context in different organisms.

PDZD8 is an ER protein localized at ER-mitochondria contact sites

Because both Mmm1 and PDZD8 reside in the ER in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we examined the subcellular localization of PDZD8 in mammalian cells. PDZD8-HA in HeLa cells showed extensive colocalization with ER-targeted Calnexin–yellow fluorescent protein (fig. S2B). To examine the localization of endogenous PDZD8, we produced a PDZD8-Venus knockin Neuro2a (N2a) cell line in which Venus fluorescent protein was knocked into the PDZD8 genomic locus using CRISPR-Cas9 (fig. S6A). The endogenous expression was confirmed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1, F to K) and Western blots using antibodies to PDZD8 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (fig. S6, B and C). ER and mitochondria in PDZD8-Venus knockin N2a (N2aPDZD8-Venus) cells were labeled by coexpression of Calnexin-mCherry and staining with an antibody cocktail against mitochondrial proteins (OXPHOS). Super-resolution imaging with structured illumination microscopy (SIM) revealed that endogenous PDZD8-Venus was localized in the ER and also found at ER-mitochondria contact sites (Fig. 1, F to K; fig. S6, E to H; and movie S1).

Subcellular fractionation of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells using antibody to PDZD8 (24) and N2aPDZD8-Venus cells confirmed that PDZD8 was enriched in the ER and present at the mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) fraction but not detected in the pure mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1E and fig. S6D). Thus PDZD8 is an ER-resident protein that is also localized at ER-mitochondria contact sites.

PDZD8 is required for formation of ER-mitochondria membrane contacts

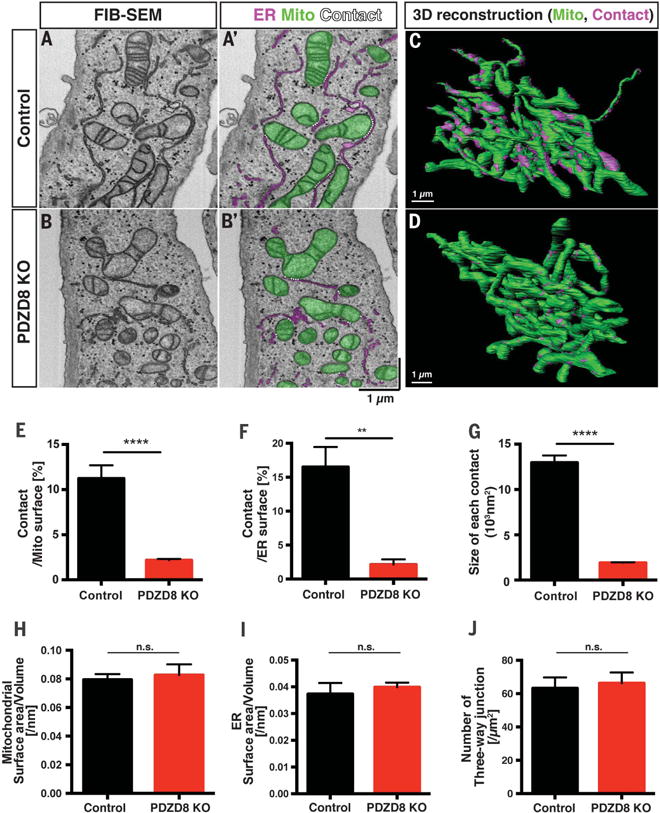

Because PDZD8 was present at ER-mitochondria contact sites and contained an SMP domain structurally and functionally orthologous to yeast ERMES complex protein Mmm1, we investigated whether PDZD8 functioned as a tethering protein and whether it was required for the formation of ER-mitochondria contacts. To map ER-mitochondria contacts quantitatively, we performed three-dimensional serial scanning electron microscopy (3D SEM) using focus ion beam–scanning EM (FIB-SEM) (Fig. 2 and movies S2 to S5). The 3D reconstructions of FIB-SEM stacks showed that the volume-surface ratio of mitochondria (Fig. 2H) and ER (Fig. 2I) and the number of three-way junctions (an index often used to measure ER tubule complexity (25, 26) (Fig. 2J) were not significantly different between the control and PDZD8 knockout (KO) cells (24). Thus, deletion of PDZD8 had no detectable effect on the structure of mitochondria and ER networks (Fig. 2, H to J, and movies S2 to S5).

Fig. 2. PDZD8 is required for the formation of the ER-mitochondria contacts in mammalian cells.

(A to D) The 3D ultrastructural features of control HeLa cells or PDZD8-KO HeLa cells (24) were examined with FIB-SEM. [(A) and (B)] Representative individual electron micrographs of control (A and A′) or PDZD8-KO (B and B′) cells. The mitochondria and ER were labeled with green and magenta, respectively (A′ and B′). The ER-mitochondria contact sites are indicated by dashed white lines (<25 nm distance between membranes). [(C) and (D)] The 3D distribution of single continuous mitochondria (green) and corresponding ER-mitochondria contact sites (magenta) reconstructed from FIB-SEM image stacks of a control (A) and a PDZD8-KO HeLa cell (B). (E to J) Quantification of the ER-mitochondria contact sites [(E) to (G)], mitochondrial (H), and ER [(I) and (J)] morphology from the 3D reconstructions. (E) Percentage of mitochondrial surface area in direct contact with ER is significantly decreased in PDZD8-KO HeLa cells compared with control HeLa cells (see also movies S2 to S5). (F) Percentage of ER surface area in contact with mitochondria is also significantly reduced in PDZD8-KO HeLa cells compared with control HeLa cells. (G) Average surface area of ER-mitochondria contact sites in PDZD8-KO HeLa cells is significantly decreased compared with control cells. [(H) and (I)] Mitochondrial (H) or ER (I) surface area to volume ratio is not significantly different between control and PDZD8-KO HeLa cells, suggesting the absence of significant change in the overall structure of both organelles. (J) Quantification of the number of three-way junctions in the ER network, a quantitative index of the extent of tubular ER (25, 26). The number of three-way junctions in the ER structure is not significantly different in PDZD8-KO HeLa cells compared with control cells. [(E), (G), and (H)] The total number of the contact sites identified in these serial EM reconstructions was 2011 (control) and 3197 (PDZD8-KO) from 10 control and 11 PDZD8-KO mitochondria fully reconstructed. For (F), (I), and (J), the ER network was quantified in regions surrounding mitochondria in four to six cells of each genotype. A nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to test statistical significance. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. Cells quantified are from two independent cell cultures. Data are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean. n.s., not significant.

We also quantified the size and distribution of ER-mitochondria contact sites [defined as membrane appositions between the two organelles with less than 25 nm distance (16)] on 10 mitochondrial segments from five HeLa cells (total surface area 2.8 × 102 μm2; total volume 13 μm3) and 11 mitochondrial segments from six PDZD8 KO HeLa cells (total surface area 3.0 × 102 μm2; total volume 17 μm3). As previously reported (2, 27, 28), 11.2% of the mitochondrial surface area was in contact with ER in control HeLa cells but, strikingly, only 2.2% of mitochondrial surface was in contact with ER in PDZD8 KO cells (Fig. 2E). We also normalized the surface of ER-mitochondria contacts relative to ER surface area: 16.5% of the ER surface area was in contact with the mitochondria in control cells, but only 2.1% of ER surface was in contact with the mitochondria in PDZD8 KO cells (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, the average surface of individual ER-mitochondria contacts was also decreased by ~80% in PDZD8 KO HeLa compared with control HeLa cells (Fig. 2G). These results strongly suggested that PDZD8 is required for tethering ER and mitochondria membranes in human cells.

PDZD8-mediated tethering is critical for ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer

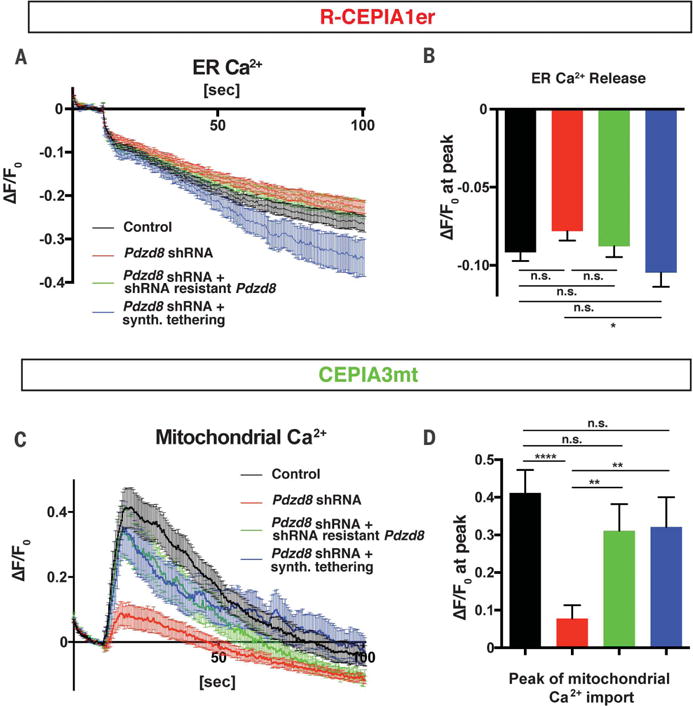

ER-mitochondria contacts are emerging as signaling hubs and have been proposed to play a critical role in Ca2+ exchange between these two organelles (2, 28–30). Upon activation of ryanodine and/or inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3R), Ca2+ released from the ER transiently reaches concentrations high enough to open the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) complex at the ER-mitochondria contacts (30–32), promoting efficient mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. To determine whether ER-mitochondria tethering by PDZD8 plays a role in Ca2+ transfer between these two organelles, we monitored Ca2+ dynamics in the ER and mitochondria simultaneously (33). We expressed genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECI) targeted to the ER (red fluorescence; R-CEPIA1er) (33) and the mitochondria (green fluorescence; CEPIA3mt) (33). In control NIH3T3 cells, stimulation of purinergic receptors with extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) (34), which generates IP3, robustly activates IP3R and induced Ca2+ release from ER stores leading to rapid Ca2+ import into mitochondria (Fig. 3 and movie S6). In contrast, in NIH3T3 cells expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) efficiently knocking down Pdzd8 (fig. S6, B and C, and fig. S7, B and C), Ca2+ import into mitochondria after ATP stimulation was significantly reduced, even though Ca2+ release from the ER was not significantly affected (Fig. 3; movie S7; and fig. S8, C and D). In addition, expression of an shRNA-resistant Pdzd8 cDNA restored Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria in ATP-treated NIH3T3 cells expressing Pdzd8 shRNA (Fig. 3). Importantly, resting Ca2+ levels in both ER and mitochondria (fig. S8, E and F), ER-independent mitochondrial Ca2+ import (fig. S9, A and B), and mitochondrial membrane potential (fig. S9, C and D) were not significantly altered in PDZD8-deficient cells. Furthermore, expression levels of mitochondrial Ca2+ regulatory proteins and other tethering proteins were not altered in Pdzd8 knockdown NIH3T3 cells (fig. S9, E to H).

Fig. 3. PDZD8-dependent membrane contacts are required for ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer.

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding mitochondria-targeted GECI (CEPIA3mt), ER-targeted GECI (R-CEPIA1er), and combinations of constructs indicated [a control plasmid (Control), a Pdzd8 shRNA plasmid, a Pdzd8 shRNA-resistant Pdzd8 cDNA-expressing plasmid, or a synthetic ER-mitochondria tethering protein]. Cells were stimulated with 200 μM extracellular ATP, and fluorescence from CEPIA3mt and R-CEPIA1er was measured. (A to D) Changes of fluorescence (ΔF) from R-CEPIA1er [(A) and (B)] or CEPIA3mt [(C) and (D)], normalized by basal signals before the stimulation (F0). Peak intensity of ΔF/F0 at 10 s after ATP stimulation shows significant reduction of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake [(C) and (D)], but not ER Ca2+ release [(A) and (B)], in Pdzd8-depleted cells (red lines and bars) compared with those in the control (black lines and bars). This altered phenotype is rescued by introducing a shRNA-resistant Pdzd8 plasmid (green lines and bars) or a synthetic ER-mitochondria tethering protein (blue lines and bars). n = 67 for control, 71 for Pdzd8-KD, 32 for Pdzd8 rescue, and 30 for tethering. Statistical significance: n.s., P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, according to unpaired t test with Welch’s correction.

To determine whether this reduced mitochondrial Ca2+ import in Pdzd8-deficient cells was indeed due to the loss of the ER-mitochondria contacts, we performed a rescue experiment using a synthetic tethering protein (28) that restored ER-mitochondria contacts (fig. S8A). Expression of a synthetic ER-mitochondria tethering construct almost completely rescued the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake induced by ATP application in PDZD8-deficient cells back to control levels (Fig. 3). Thus, our results demonstrate that ER-mitochondria tethering mediated by PDZD8 is required for efficient Ca2+ transfer from ER into mitochondria in metazoan cells.

Synaptically induced Ca2+ release from ER stores triggers mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites of neurons are critical for physiological responses, including synaptic integration and plasticity (35, 36). Although several studies have suggested that ER stores and mitochondria can influence dendritic Ca2+ dynamics (37–47), the functional importance of ER-mitochondria contacts is unknown in neurons. PDZD8 was expressed at high levels throughout the developing and adult mouse central nervous system (CNS), including in the neocortex (fig. S10). Thus, we investigated whether ER-mitochondria tethering by PDZD8 affected Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites of mouse cortical pyramidal neurons.

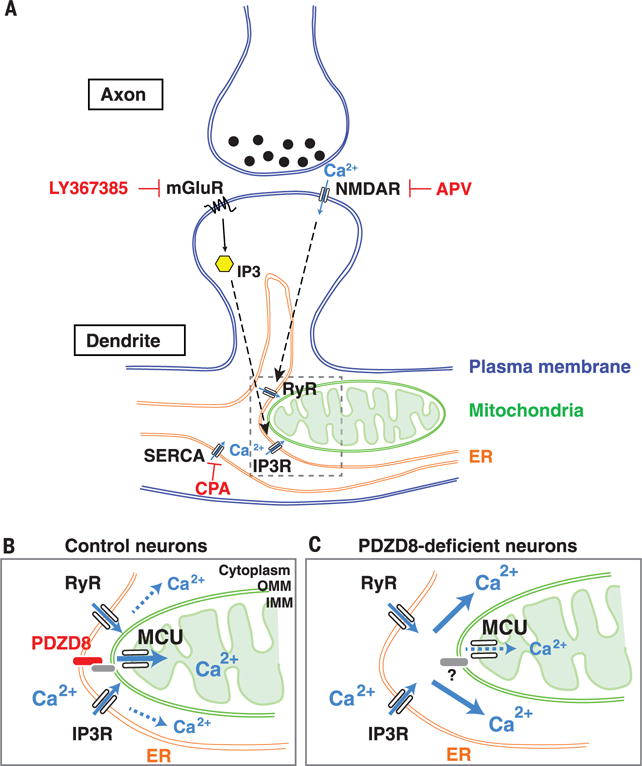

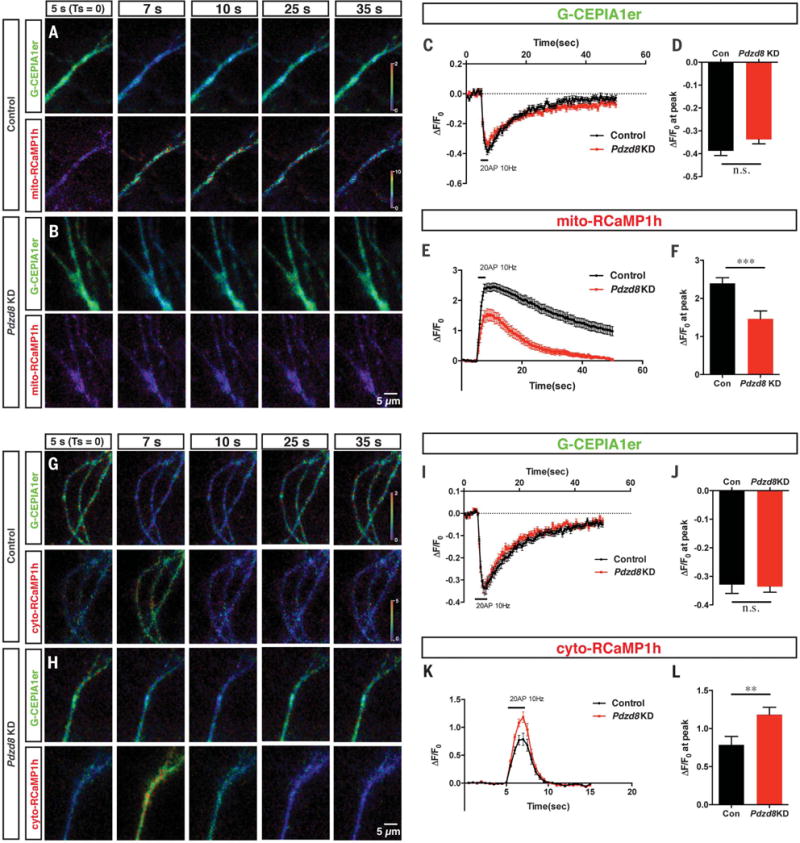

We used green (G)–CEPIA1er and mitochondria-targeted RCaMP1h (mito-RCaMP1h) to visualize ER ([Ca2+]ER) and mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ ([Ca2+]mito) dynamics simultaneously (33, 48) in synaptically mature cortical pyramidal neurons. We induced synaptic activity by stimulation with a concentric bipolar electrode [20 action potentials (AP) at 10Hz], which efficiently triggers pre-synaptic release in close proximity to the dendrites of target neurons (49). The dendrites of untreated, control cortical pyramidal neurons showed robust ER Ca2+ release and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake after synaptic stimulation (fig. S12). Mitochondrial Ca2+ import in dendrites was dependent on ER Ca2+ release by applying a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor as shown by application of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA). CPA treatment efficiently depleted [Ca2+]ER and also abolished mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (fig. S12, A to F). Thus, Ca2+ released from ER stores is the main source of mitochondrial Ca2+ import in dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons. Previous studies have suggested that activation of postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and/or metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) trigger efficient Ca2+ release from ER stores (40, 41, 44–46, 50). Consistent with this, incubation with the NMDA receptor antagonist D-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid or the mGluR1 blocker LY367385 abolished ER Ca2+ release and suppressed mitochondrial Ca2+ import (fig. S12, G to N). Thus, as expected, activation of both NMDA receptor and mGluR1 are required for synaptically evoked Ca2+ release from ER stores in the dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. PDZD8 is an ER-mitochondria tethering protein regulating dendritic Ca2+ dynamics in neurons.

Schema summarizing the main findings in this study. (A) In dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons, synaptically induced ER Ca2+ release requires both mGluR and NMDA receptor (see results in fig. S12). Our results demonstrate that the majority of synaptically induced Ca2+ imported into dendritic mitochondria originates from ER stores. (B and C) Our results also demonstrate that in neuronal dendrites, PDZD8-dependent ER-mitochondria tethering plays a critical role in cytoplasmic Ca2+ homeostasis because in the absence of PDZD8 (C), a significantly higher fraction of synaptically induced Ca2+ release from the ER ends up in the cytoplasm rather than in the mitochondrial matrix, compared with control (B).

PDZD8 regulates dendritic Ca2+ dynamics in cortical neurons

Pdzd8 knockdown in cortical layer II/III pyramidal neurons did not impair the overall structure and distribution of dendritic ER and mitochondria in vivo (fig. S11). To determine whether PDZD8-dependent ER-mitochondria membrane tethering regulates ER and mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics in neuronal dendrites, we introduced G-CEPIA1er and mito-RCaMP1h with either control or Pdzd8 shRNA using ex utero electroporation in cortical pyramidal neurons. After physiological synaptic stimulation (20 AP at 10 Hz), Ca2+ release from ER stores was coupled with robust mitochondrial Ca2+ import in dendrites expressing control shRNA (Fig. 4, A to F, and movie S8). However, mitochondrial Ca2+ import was significantly reduced in Pdzd8 knockdown neurons, consistent with data obtained in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 4, B, E, and F, and movie S9). Expression levels of MCU or proteins proposed to regulate ER-mitochondria contacts (PIPIP51 and VDAC1) were not changed in Pdzd8 knockdown neurons (fig. S13, A to D). Furthermore, mitochondrial Ca2+ import and extrusion kinetics, as well as resting Ca2+ amount in ER and mitochondria, were not altered in PDZD8-deficient neurons (fig. S13, E to J). These results strongly suggest that the significant reduction of mitochondrial Ca2+ import upon induction of ER Ca2+ release in dendrite PDZD8-deficient neurons is most likely due to the loss of ER-mitochondria contacts rather than to secondary effects due to alteration of the mitochondrial Ca2+ import machinery.

Fig. 4. PDZD8 loss of function in cortical neurons identifies a novel role for ER-mitochondria interface in the regulation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites.

(A to F) Dendritic ER and mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics were monitored using G-CEPIA1er and mito-RCaMP1h, respectively. G-CEPIA1er and mito-RCaMP1h were cotransfected with control or Pdzd8 shRNA plasmids using ex utero electroporation at embryonic day 15.5 and imaged at 19 to 22 days in vitro (DIV). Proximal dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons display significant ER Ca2+ release and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake after physiological stimulation of presynaptic release (20 AP at 10 Hz). Representative images are displayed as normalized ratio (ΔF/F0) of each probe [(A) and (B)]. This stimulation evokes normal ER Ca2+ release in dendrites of both control and PDZD8-deficient neurons [(C) and (D)] but shows significantly decreased mitochondrial Ca2+ import [(E) and (F)]. n = 63 dendritic segments from 18 neurons for control and 28 dendritic segments from 14 neurons for Pdzd8 knockdown. (G to L) Dendritic ER (G-CEPIA1er) and cytosolic Ca2+ (RCaMP1h) levels were visualized before and after 20 AP in 21 to 22 DIV cortical neurons. [(G) and (H)] Cropped images show fluorescence as ratio normalized by basal signals before stimulation (ΔF/F0). Cytosolic Ca2+ accumulation is significantly higher in Pdzd8 knockdown neurons compared with control [(K) and (L)] despite unchanged ER Ca2+ release evoked by synaptic stimulation [(I) to (J)]. n = 30 dendritic segments from 10 neurons for control and 39 dendritic segments from 13 neurons for Pdzd8 knockdown. Statistical significance: n.s., P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, according to unpaired t test with Welch’s correction.

Finally, we investigated whether this uncoupling of ER-mitochondria Ca2+ exchange by PDZD8 loss of function resulted in impaired cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) dynamics. To do this, we coelectroporated G-CEPIA1er and cytosolic RCaMP1h together with control or Pdzd8 shRNA and imaged them before and after synaptic stimulation (20 AP at 10 Hz). [Ca2+]c levels were significantly elevated in Pdzd8 knockdown dendrites compared with control dendrites (Fig. 4, G to L). Thus, a significant fraction of Ca2+ released from ER stores is directly imported into mitochondria upon synaptic activation in control dendrites, and PDZD8 regulates cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites through its function in ER-mitochondria tethering.

Here, we have identified PDZD8 as an ER-mitochondria tethering protein in metazoan cells and demonstrated that the SMP domain–containing protein PDZD8 might represent a structural and functional ortholog of the yeast ERMES protein component Mmm1. Furthermore, our results also demonstrate the importance of ER-mitochondria tethering for dendritic Ca2+ homeostasis in mammalian neurons (Fig. 5, B and C). Dendritic Ca2+ dynamics play several critical functions ranging from synaptic integration properties to various forms of synaptic plasticity (35, 36). Cytoplasmic Ca2+ microdomains in neuronal dendrites represent a cellular mechanism recently proposed to regulate branch-specific synaptic integration and plasticity (51, 52). We suggest that the control of cytoplasmic Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites involves ER-mitochondria coupling and, by analogy to its proposed functions in non-neuronal cells, this organelle interface might play other important biological functions such as lipid exchange and coupling of mitochondrial DNA replication with mitochondrial fission in neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Zhang and J. Sodroski for providing the PDZD8 KO cell line and antibody to PDZD8, W. Rice and E. Eng for help with FIB-SEM imaging, and S. Morton for helping with the generation of PDZD8 antibody with Covance. We thank D. Hirsh for connecting us with the NYSBC. We thank E. Area-Gomez, T. M. Jessell, and B. Honig for their advice and critical reading of the manuscript and members of the Polleux laboratory for constructive discussions. This work was supported by grants awarded from NIH (NS089456 to F.P. and GM122589 and GM45735 to L.A.P.), an award from the Fondation Roger De Spoelberch (F.P.), an International Research Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Y.H.), and a grant from JST/PRESTO (JPMJPR16F7 to Y.H.). D.S.P. also acknowledges NIH grant GM030518 to B. Honig and equipment grants S10OD012351 and S10OD021764 to the Columbia Department of Systems Biology. N-SIM images were collected in the Confocal and Specialized Microscopy Shared Resource of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University, supported by NIH grants P30 CA013696 (National Cancer Institute) and Shared Instrumentation Grant 1S10 OD14584. The Helios data collection was performed at the Simons Electron Microscopy Center located at the NYSBC, supported by grants from the Simons Foundation (349247) and New York Office of Science Technology and Academic Research (NYSTAR) with additional support from NIH S10 RR029300. RNA in situ hybridization was performed by the RNA In Situ Hybridization Core facility at Baylor College of Medicine, which is supported by a Shared Instrumentation Grant from NIH (1S10OD016167) and NIH Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center grant U54 HD083092 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or NIH. Y.H. and F.P. conceptualized the study and were assisted by S-K.K., W.M.P., and L.A.P. in experimental design. F.P. supervised the study. Y.H., S-K.K., and P.E. carried out experiments in mammalian systems. W.M.P. performed experiments in yeast. W.M.P. and L.A.P. analyzed the data obtained from the experiments in yeast. W.M.P. and D.S.P. performed structural protein modeling. Y.H., H.P., M.A.P., and J.L. performed and analyzed the 3D FIB-SEM results. A.R. performed 3D FIB-SEM image acquisition. Y.H., S-K.K., W.M.P., L.A.P., and F.P. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/358/6363/623/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

References (53–64)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Kornmann B, et al. Science. 2009;325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzuto R, et al. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Area-Gomez E, et al. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1810–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Area-Gomez E, Schon EA. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;38:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paillusson S, et al. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabadkai G, et al. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:901–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vos KJ, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1299–1311. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim Y, Cho IT, Schoel LJ, Cho G, Golden JA. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:679–696. doi: 10.1002/ana.24488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosson P, Marchetti A, Ravazzola M, Orci L. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e46293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filadi R, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E2174–E2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504880112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naon D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11249–11254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606786113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AhYoung AP, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E3179–E3188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422363112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schauder CM, et al. Nature. 2014;510:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong H, Park J, Lee C. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1857–1871. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helle SC, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2526–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alva V, Lupas AN. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopec KO, Alva V, Lupas AN. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1927–1931. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee I, Hong W. FASEB J. 2006;20:202–206. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4581hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornmann B, Walter P. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1389–1393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanekamp T, et al. Genetics. 2002;162:1147–1156. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobbs AE, Srinivasan M, McCaffery JM, Jensen RE. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:401–410. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang AB, Peter AT John, Walter P, Kornmann B. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:883–890. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201502105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S, Sodroski J. Virology. 2015;481:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westrate LM, Lee JE, Prinz WA, Voeltz GK. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:791–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-163501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:418–423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423026112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoica R, et al. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3996. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Csordás G, et al. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowland AA, Voeltz GK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:607–625. doi: 10.1038/nrm3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giacomello M, et al. Mol Cell. 2010;38:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csordás G, et al. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patron M, et al. Mol Cell. 2014;53:726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki J, et al. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4153. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnstock G. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spruston N. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:206–221. doi: 10.1038/nrn2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjöström PJ, Rancz EA, Roth A, Häusser M. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:769–840. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SH, et al. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5953–5963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0465-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thayer SA, Miller RJ. J Physiol. 1990;425:85–115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cherra SJ, 3rd, Steer E, Gusdon AM, Kiselyov K, Chu CT. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeckel MF, Kapur A, Johnston D. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:625–633. doi: 10.1038/10180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emptage N, Bliss TV, Fine A. Neuron. 1999;22:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishiyama M, Hong K, Mikoshiba K, Poo MM, Kato K. Nature. 2000;408:584–588. doi: 10.1038/35046067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finch EA, Augustine GJ. Nature. 1998;396:753–756. doi: 10.1038/25541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takechi H, Eilers J, Konnerth A. Nature. 1998;396:757–760. doi: 10.1038/25547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang SS, Denk W, Häusser M. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/81792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyata M, et al. Neuron. 2000;28:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee KF, Soares C, Thivierge JP, Béïque JC. Neuron. 2016;89:784–799. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akerboom J, et al. Front Mol Neurosci. 2013;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maximov A, Pang ZP, Tervo DG, Südhof TC. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;161:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verkhratsky A. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:201–279. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Losonczy A, Makara JK, Magee JC. Nature. 2008;452:436–441. doi: 10.1038/nature06725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheffield ME, Dombeck DA. Nature. 2015;517:200–204. doi: 10.1038/nature13871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.