SUMMARY

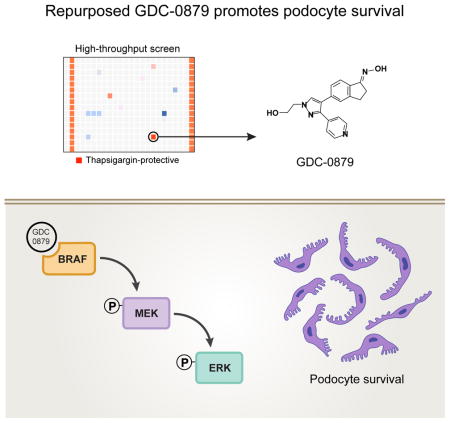

Progressive kidney diseases affect approximately 500 million people worldwide. Podocytes are terminally differentiated cells of the kidney filter, whose loss leads to disease progression and kidney failure. To date, there are no therapies to promote podocyte survival. Drug repurposing may therefore help accelerate the development of cures in an area of tremendous unmet need. In a newly developed high-throughput screening assay of podocyte viability, we identified the BRAFV600E inhibitor GDC-0879 and the adenylate cyclase agonist forskolin as podocyte survival promoting compounds. GDC-0879 protects podocytes from injury through paradoxical activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. Forskolin promotes podocyte survival by attenuating protein biosynthesis. Importantly, GDC-0879 and forskolin are shown to promote podocyte survival against an array of cellular stressors. This work reveals new therapeutic targets for much needed podocyte-protective therapies, and provides insights into the use of GDC-0879-like molecules for the treatment of progressive kidney diseases.

In Brief (eTOC Blurb)

Sieber et al. implement a high throughput screening assay of podocyte viability and find that the BRAF inhibitor GDC-0879 protects podocytes by restoring MAPK signaling, offering a novel repurposing strategy for targeted kidney therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Progressive kidney diseases are a rising, worldwide public health problem (Jha et al., 2013), and yet no treatments to prevent them or halt their progression have been developed in the last 40 years (D’Agati et al., 2011; Jha et al., 2013; Mundel and Greka, 2015). Damage and loss of podocytes, a component of the three–layered kidney filtering unit, is a critical event in the pathogenesis of progressive kidney disease leading to kidney failure (Wiggins, 2007). Therefore, there is tremendous unmet need for therapies targeted specifically to podocyte survival.

With its complex architecture as an integral component of the filter barrier, the podocyte is the only post-mitotic cell in the kidney, and its unique role and activity require a highly dynamic endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Markers of ER stress have been detected in podocytes in different kidney diseases (Bek et al., 2006), as well as in human kidney biopsies (Sieber et al., 2010). ER stress by exposure to thapsigargin and palmitic acid has been previously shown to lead to podocyte death (Sieber et al., 2010). We sought to develop and validate a high throughput screen (HTS) for small molecules that promote podocyte survival. Given the lack of available podocyte-targeted therapies and the urgent unmet need, we focused our efforts in this proof-of-concept study on drug repurposing, and we screened the Selleck Bioactive Compound Library comprised of 1649 clinically applied and preclinical molecules.

Cell context-dependent activity of targeted anti-tumor drugs has been the subject of intense scientific inquiry (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2011). The considerable excitement following the positive therapeutic effects of BRAF inhibitors in clinical trials in patients with metastatic melanoma was tempered by the observation that about 25% of patients treated with these drugs unexpectedly developed hyperproliferative skin lesions (keratoacanthomas) and squamous-cell carcinomas, which resolved following drug withdrawal (Cichowski and Jänne, 2010). Paradoxically, although tumor cells carrying cancer-causing BRAF mutations (BRAFV600E) die when exposed to the ATP-competitive BRAF inhibitor GDC-0879, other tumor cells (i.e. with KRAS mutations) or wild-type cells proliferate in the presence of the same compound (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010). This phenomenon is due to differential GDC-0879 binding to mutant BRAF versus wild-type BRAF: when GDC-0879 binds mutant BRAF, it inactivates it, causing cancer cells to die; in contrast, its binding to wild-type BRAF (or CRAF) promotes dimeric complex formation and results in activation of MEK/ERK signaling and tumor cell proliferation (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010). These studies show that cellular context is critically important for the mechanism of action of GDC-0879 in cancer cells. However, nothing is known about the effects of this compound on non-proliferating, post-mitotic cells. Here we describe the discovery that GDC-0879 promotes podocyte survival, revealing a cell-context-specific effect in post-mitotic podocytes.

RESULTS

HTS assay development: ER stress–induced cell death in post-mitotic podocytes

Cell death caused by chronic ER stress is associated with a shift from an adaptive to a pro-apoptotic unfolded protein response (UPR), and the switch is attributed to the PERK–ATF4 branch, which is the main regulator of the apoptosis–linked transcription factor CHOP (Fig. S1A) (Harding et al., 2000a; Hetz, 2012; Marciniak et al., 2004; Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). We evaluated the effect of thapsigargin, a sarcoplasmic/ER calcium ATPase (Atp2a2, also known as SERCA) inhibitor, and a widely used ER stressor (Kijima et al., 1991), on podocyte death by confirming the involvement of PERK signaling as a switch from an early adaptive to a late pro-apoptotic ER stress response in podocytes (Fig. S1B–E). Of interest, depletion of the ATF4 effector GADD34 (Kaufman, 2002; Ma and Hendershot, 2001) in podocytes caused greater susceptibility to thapsigargin (Fig. S1F, G), suggesting that release of a GADD34–mediated negative feedback (Fig. S1A), enabling sustained PERK signaling during ER stress (Fig. S1H, I), promotes podocyte death. Depletion of the well-established pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP (Fig. S1J) did not rescue thapsigargin–mediated cell death (Fig. S1K). Together, these data confirmed thapsigargin as a cell death inducer in podocytes, and defined a window between the adaptive and late pro-apoptotic phases of thapsigargin injury within which to screen for small molecules promoting podocyte survival. We thus designed a high throughput screen (HTS) using thapsigargin, seeking to identify podocyte-protective compounds.

GDC-0879 and forskolin identified as podocyte protective compounds

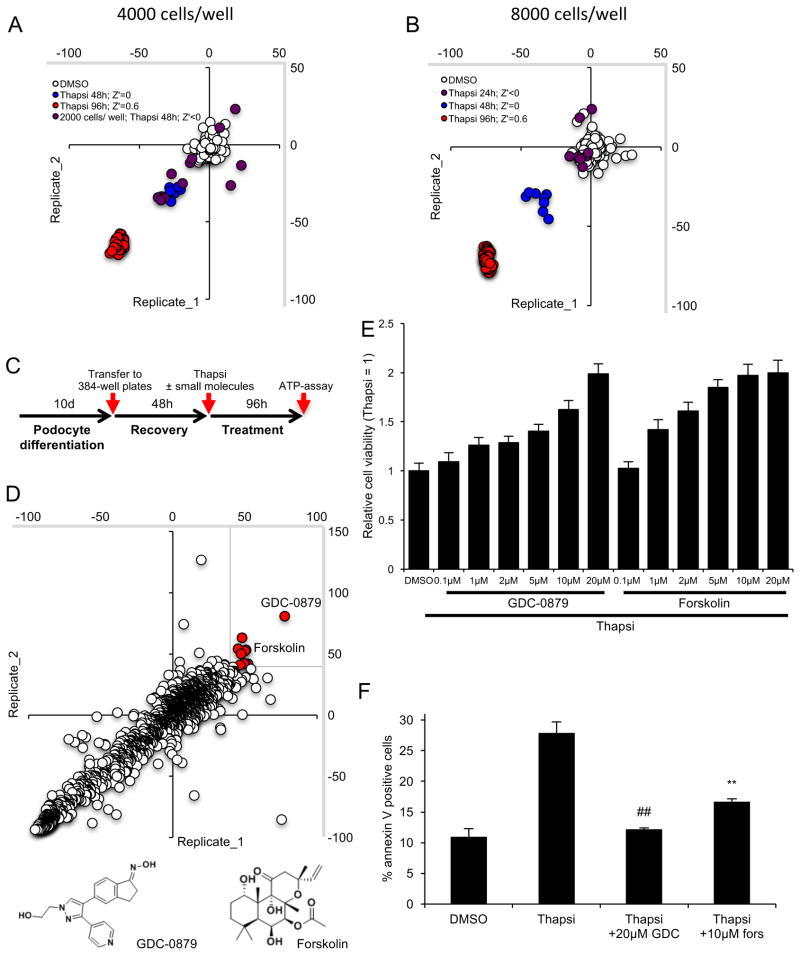

The HTS was implemented by transferring fully differentiated podocytes into 384 well plates (Fig. 1A–C). Optimal and reproducible cell confluency and homogeneity with minimal well–to–well variability was achieved at 4,000 to 8,000 cells per well on collagen–I coated wells (Fig. 1A, B). Using thapsigargin, relative cell viability was assessed based on cellular ATP levels. A favorable Z′ of 0.5 (0.5 ≤ Z′ ≤ 1, (Zhang et al., 1999)) characterizing the separation window of thapsigargin– and vehicle (DMSO)–treated cells, was confirmed at 96 hours (Fig. 1A, B).

Figure 1. GDC-0879 and forskolin identified in HTS of clinically active compounds.

A, B) High throughput assay development and reproducibility. A favorable Z′ ≥0.5 was obtained at 96 hours of thapsigargin–treatment. Fully differentiated podocytes were re–plated into 384–well plates at 2000 (A), 4000 (A) and 8000 (B) cells per well and thapsigargin was applied for the indicated times, respectively. Scatterplot between several replicates as percent change of cell viability relative to DMSO control–treated cells determined by assessing ATP levels. Z′ indicates screen potency of the different conditions. C) Scheme of HTS workflow. D) 1649 compounds were screened in duplicates for their effect on thapsigargin–mediated cell death. Scatterplot between two replicates as percent change of cell viability relative to thapsigargin–treated cells determined by assessing ATP levels. Protective hits were defined as compounds eliciting responses for both replicates individually that are larger than 40% (red dots). The chemical structures of GDC-0879 and forskolin are shown below. E) Dose responsive effect of GDC-0879 and forskolin on thapsigargin–treated podocytes at 96 hours. Bar graph represents relative cell viability (ATP levels) ± SD, data normalized to thapsigargin treatment (n=32). F) Annexin V in podocytes treated with thapsigargin in the presence or absence of GDC and forskolin at 48 hours. Bar graph shows mean % ± SD of annexin V positive cells (n=3). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ## p < 0.0001 (vs. thapsigargin, Bonferroni–corrected).

The Selleck Library was screened in duplicate, with excellent reproducibility (Fig. 1D). Ten compounds (representing a 0.6% hit rate) passed the arbitrary threshold of a protective response defined as more than 40% of thapsigargin-only treated cells (see methods for details). These early hits were re–tested in a dose–dependent (0.1 – 20μM) manner, and cell viability was again determined based on relative ATP levels in a secondary screen. Of these compounds, the BRAF inhibitor GDC-0879 emerged as the top hit (Fig. 1D). The adenylate cyclase agonist forskolin was also identified as a putative podocyte protector (Fig. 1D). Both hits were confirmed to be significantly protective in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). The effect on cell death was validated orthogonally using annexin V positive staining (Fig. 1F). We also asked if other BRAF inhibitors are podocyte protective. Several BRAF inhibitors (Sorafenib, Dabrafenib, SB590885, PLX4720 and Vemurafenib) were part of the Selleck Library (Fig. S2A), of which SB590885 nearly passed the hit threshold. A follow-up, secondary cell viability screen performed at 4 dose points showed a trend towards protection for Dabrafenib and SB590885 (Fig. S2B). In support of BRAF inhibitors as podocyte-protective compounds, an additional follow up screen with 367 kinase inhibitors revealed another BRAF inhibitor, SB-682330, which rescued podocytes with greater than 10-fold higher efficacy compared to GDC-0879 (Fig. S2C). These data confirmed that a number of compounds targeting BRAF promote podocyte survival.

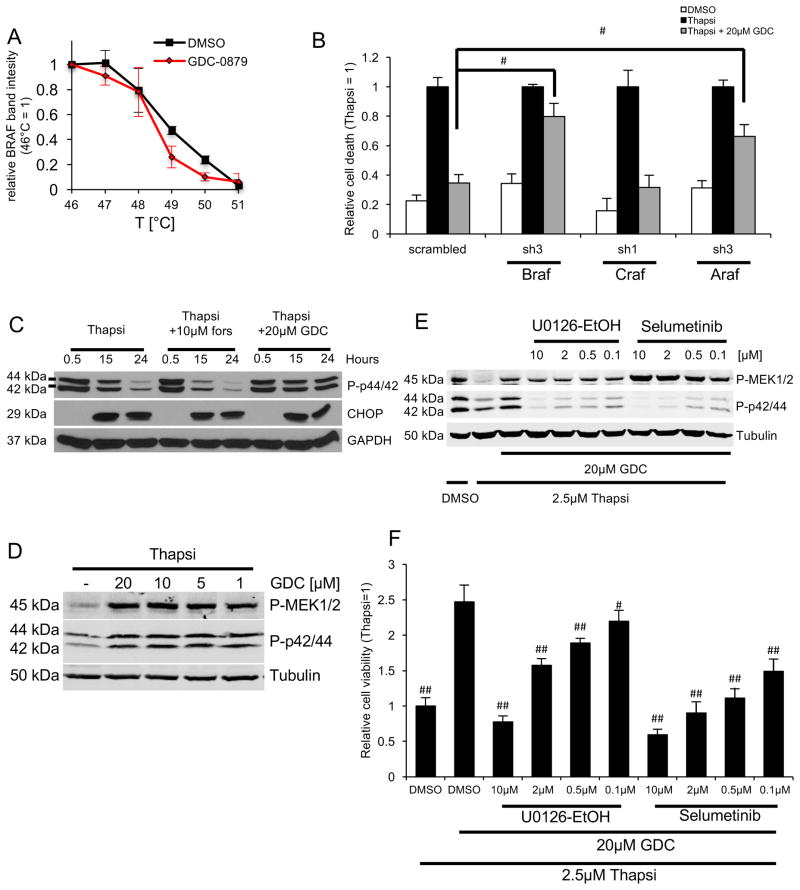

GDC-0879 promotes podocyte survival by restoring MAPK activity

GDC-0879 was designed to target a specific BRAF mutation (BRAFV600E) often found in melanomas, but it also binds wild type BRAF, CRAF and ARAF, with minimal efficacy against other kinases (Hansen et al., 2008; Hoeflich et al., 2009). In podocytes, GDC-0879 negatively affected thermal stability of endogenous wild type BRAF as assessed by cellular thermal shift assays (Fig. 2A), suggesting GDC-0879 binds BRAF. To test whether the protective action of GDC-0879 is through BRAF, we examined GDC-0879’s effect in Raf kinase depleted podocytes. GDC-0879’s rescue effect was reversed in podocytes expressing the most efficient shRNAs against Braf and Araf (Fig. 2B, Fig. S2D). This experiment suggested that, in addition to BRAF, GDC-0879 could also affect signaling events downstream of BRAF-ARAF in podocytes. As an additional control, given previous studies where GDC-0879 was shown to bind weakly to casein kinase 1 delta (CK1δ, 50%), ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (RSK1, 25%), and receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 (RIP2K, 25%) (Hoeflich et al., 2009), we performed targeted studies in podocytes using CK1δ, RSK1 and RIP2K inhibitors. None of these inhibitors, either individually or in all combinations, rescued podocytes from thapsigargin (Fig. S2E).

Figure 2. GDC-0879 promotes podocyte survival through activation of MEK/ERK signaling.

A) Decreased thermal stability assessed by cellular thermal shift assay indicated GDC-0879 as a target of BRAF. B) Knockdown of BRAF, ARAF and CRAF did not affect thapsigargin-mediated podocyte death. In the presence of GDC-0879, BRAF– and ARAF–depletion was sufficient to partially reverse the protective effect of GDC-0879. Bar graph represents relative annexin V positive cells ± SD, data normalized to thapsigargin (n=3), # p < 0.001 (vs. scrambled thapsi+GDC, Bonferroni-corrected). D) GDC-0879 restored ERK activity as assessed by phosphorylated p42/44 levels. Forskolin had no effect on p44/42 phosphorylation. CHOP abundance was not affected by compound treatment. D) Detection of simultaneous MEK1/2 and p44/42 phosphorylation by GDC-0879 at 4-dose points. E) MEK inhibitors Selumetinib and UO216-EtOH blocked GDC-0879-mediated p42/44 phosphorylation. F) MEK inhibitors Selumetinib and UO216-EtOH reversed the podocyte protective effect of GDC-0879. Bar graph represents relative cell viability (ATP levels) ± SD. Thapsigargin treatment was set to 1 (n=16); # p < 0.001, ## p < 0.0001 (vs thapsi + GDC-0879, Bonferroni-corrected).

Next, we sought to assess the effect of GDC-0879 on MEK/ERK signaling downstream of BRAF (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010). Thapsigargin treatment induced a significant reduction in ERK activity as shown by reduced p44/42 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation (Fig. 2C) and MEK activity as shown by reduced MEK1/2 phosphorylation (P-MEK1/2)(Fig. 2D), which correlated with the induction of the pro-apoptotic ER stress marker CHOP (Fig. 2C). GDC-0879 reversed the thapsigargin-mediated reduction in p42/44 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). CHOP levels remained unaffected, indicating that ER stress persists in podocytes, despite GDC-0879 treatment. GDC-0879 restored both p44/42 and MEK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2D), suggesting that podocytes undergo a paradoxical MEK/ERK activation similar to that observed in some cancer cells (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010).

To gain further insight into the role of restored MAPK signaling on podocyte survival, we investigated the effect of MEK inhibitors. The Selleck Library included the four MEK inhibitors Selumetinib, U0126-EtOH, Trametinib, and PD0325901 (Fig. S2A). Similar to the initial HTS, a follow-up cell viability screen at 4 dose points confirmed that MEK inhibitors alone have no effect on thapsigargin-induced podocyte death (Fig. S2F). In contrast, treatment with the MEK inhibitors Selumetinib and U0126-EtOH reversed the protective effect of GDC-0879. The two MEK inhibitors dose-dependently reversed GDC-0879-dependent p44/42 phosphorylation and blocked the survival benefit conferred by GDC-0879 on podocytes (Fig. 2E, F). These data indicated that GDC-0879 protects podocytes from thapsigargin-induced death through activation of MEK/ERK signaling.

Forskolin protects podocytes by blunting protein biosynthesis

Next, we turned our attention to forskolin, the chemically distinct hit from the primary screen (Fig. 1D–F). In contrast to GDC-0879, forskolin did not affect thapsigargin-mediated MAPK signaling (Fig. 2C, D). To investigate the well–characterized role of forskolin as an adenylate cyclase agonist elevating intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels (Seamon et al., 1981), podocytes were treated with thapsigargin in the presence of the phosphodiesterase–resistant cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP (1mM), which resulted in enhanced survival (Fig. S3A, B). To investigate whether the cAMP targets protein kinase A (PKA) and EPAC (exchange factor directly activated by cAMP (Gloerich and Bos, 2010)) are involved in this mechanism, we tested a) single- and double-knockdown of the two catalytic PKA subunits α and β (Fig. S3C, D), b) addition of the PKA inhibitor H89 (Fig. S3D), c) PKA Cα, Cβ and cAMP regulated binding protein (CREB) triple–knockdown (Fig. S3E, F) (Kim et al., 2008; Mayr and Montminy, 2001), d) knockdown of EPAC1, and quadruple–knockdown of PKA Cα and β, CREB, and EPAC1 (Fig. S3E, F). None of these could reverse the forskolin effect (Fig. S3D, F). Of note, PKA Cα and β double-silenced podocytes showed increased CREB activation (P-CREB), which was not affected by forskolin and H89 (Fig. S3G), leading to the speculation that compensatory mechanisms are activated in PKA-depleted cells. Nevertheless, these results did not link PKA activity to forskolin’s protective effect on thapsigargin-treated podocytes. Taken together, these findings suggested that forskolin promotes podocyte survival in a PKA– and EPAC–independent manner.

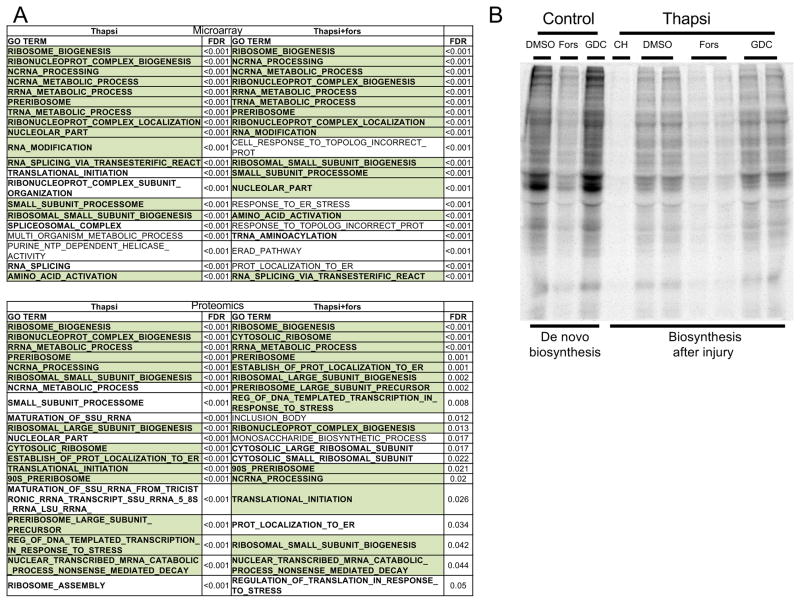

To gain insights into the target pathways affected by forskolin, we took an unbiased approach and evaluated global gene expression and proteomic profiles shortly before the onset of thapsigargin-mediated cell death (20 hours). Gene Ontology (GO)-term-dependent gene set enrichment analysis showed highest enrichment scores related to protein biosynthesis (RNA processing, ribosome biosynthesis, translation). A detailed look at the individual relative gene expression and protein abundance levels revealed a significant reduction of protein biosynthetic activity in the presence of forskolin (Fig. S4). Of interest, these findings were in line with our experiments showing that low dose cycloheximide alone, which is more potent than forskolin in inhibiting protein biosynthesis (Fig. 3B), is not protective for podocytes (Fig. S1). However, the combination of cycloheximide with a PERK inhibitor (Fig. S1) rescued podocytes, suggesting there is an optimal, narrow therapeutic window for attenuation of protein biosynthesis as a podocyte protective strategy. Seeking to validate these findings by measuring methionine incorporation as a marker of protein biosynthesis, we found that forskolin blocked biosynthesis at baseline as well as after thapsigargin-induced podocyte injury (Fig. 3B). Of note, GDC-0879 had no effect on protein biosynthesis (Fig. 3B). Dialing down protein biosynthesis may thus be a mechanism of action for forskolin, suggesting that the compound fine-tunes responses to sustained cellular stress, thus improving cell survival.

Figure 3. Forskolin promotes podocyte survival by attenuating protein biosynthesis.

A) GSEA of microarray and proteomics data of podocytes treated with thapsigargin revealed enrichment for genes/proteins associated with protein biosynthesis (bold). Top 20 GO term enriched gene sets are indicated (FDR, false discovery rate). Gene sets shared between thapsigargin ± forskolin are highlighted in green. B) Forskolin, but not GDC-0879, attenuated protein biosynthesis after sustained podocyte injury (thapsi) as measured by fluorescently labeled incorporated methionine analog L-azidohomoalanine. 15 hour de novo protein biosynthesis was evaluated at baseline (control) or after 9 hour of thapsigargin-treatment (9–24 hour). See methods for details.

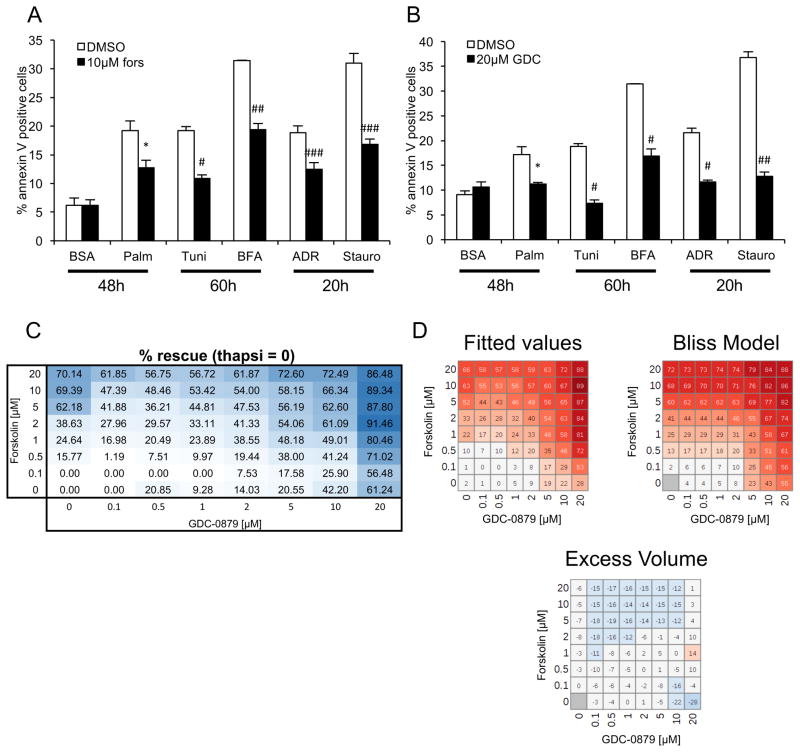

GDC-0879 and forskolin promote podocyte survival against an array of cellular stressors

GDC-0879 protected podocytes from thapsigargin-induced death without changing CHOP abundance (Fig. 2C), thus indicating that the rescue effect was downstream of the UPR or, alternatively, independent of ER stress. Similarly, forskolin treatment did not alter the UPR markers BIP, CHOP, GADD34 or splicing of Xbp1 (Xbp1s)(Fig. S5A, B), nor did it alter the nuclear localization of CHOP or ER morphology (indicated by the ER chaperone calnexin)(Fig. S5C, D) (Ron and Walter, 2007). Also, the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin did not reverse the protective effect of forskolin (Fig. S5E, F). Together, these findings pointed to the intriguing possibility that GDC-0879 and forskolin may defend podocytes from a broader array of cellular stressors, even ones that do not involve ER stress.

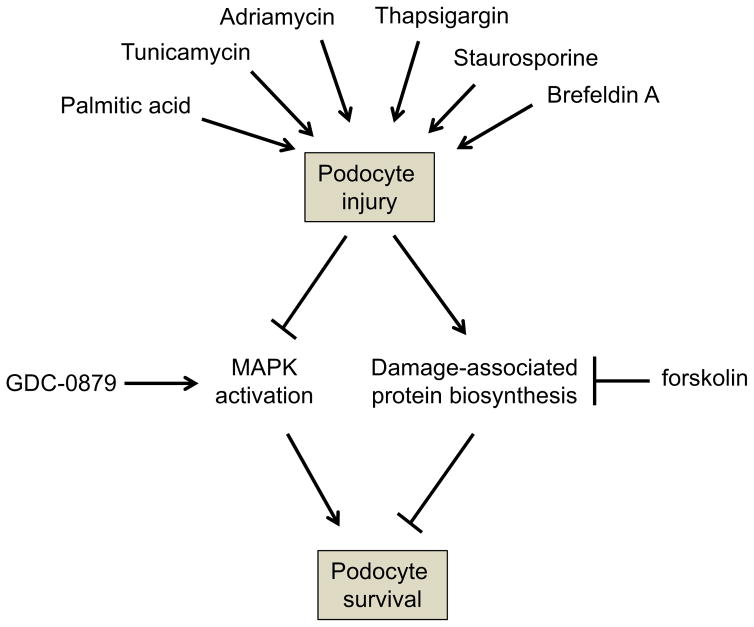

To test this notion, cell survival was measured after cells were treated with ER stress–independent cell death inducers such as adriamycin (DNA damage) or staurosporine (pankinase inhibitor), as well as other ER stress–inducing agents such as palmitic acid, tunicamycin or brefeldin A, in the presence of forskolin (Fig. 4A) or GDC-0879 (Fig. 4B). These studies showed that the protective effect of both drugs was universal, regardless of cell death inducer (Fig. 4A, B). An 8-dose point matrix combination experiment showed that both compounds protect podocytes from death in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 4C). Analysis using a Bliss independence synergy model did not support synergy between the two compounds (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data indicated that the two compounds work independently to attenuate cell death in podocytes (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. GDC-0879 and forskolin protect podocytes from diverse cellular stressors.

A, B) Cell survival was measured after cells were treated with palmitic acid, tunicamycin, brefeldin A, adriamycin or staurosporine in the presence of forskolin (A) and GDC-0879 (B). C) A matrix of the combination of GDC-0879 and forskolin at 8-dose points. D) Predicted values based on curve fits of the compound combinations, Bliss independence synergy model predicted activity, and difference between curve fits and model prediction (excess volume). No synergy was observed between the two compounds. In combination, observed rescue was modestly less than predicted by synergy model for higher concentrations of forskolin, suggesting mild antagonism that may be due to cytotoxicity. Poor fit for two values at 10 and 20 μM of GDC-0879 alone results in likely artifact in corresponding calculated excess volume. Similar results were seen with a Loewe additivity model.

Figure 5. New mechanistic insights into podocyte-protective therapeutic targets.

A variety of agents (palmitic acid, tunicamycin, brefeldin A, adriamycin, staurosporine and thapsigargin) promote podocyte injury. This results in a reduction in MEK/ERK signaling, which leads to cell death. GDC-0879 promotes activation of MAPK signaling to rescue podocytes. In a parallel pathway, podocyte injury results in a compensatory induction of protein biosynthesis. Forskolin confers a protective advantage by attenuating protein biosynthesis.

DISCUSSION

The successful execution of a HTS revealed GDC-0879 and forskolin as podocyte-protective compounds (Fig. 5). The HTS described in this study was initially designed to target ER stress–induced cell death, but in light of our findings with several stressors (Fig. 5), this HTS can likely be adapted and deployed for screening against different types of podocyte injury (inflammatory, metabolic etc.). Our findings have several important biological as well as therapeutic implications.

First, forskolin was shown to protect podocytes in a cAMP-dependent manner, which is in line with recent in vivo data showing that forskolin protects mice from severe kidney injury (Li et al., 2014). Furthermore, inactivation of adenylate cyclase 1 results in increased susceptibility to kidney filter damage (Xiao et al., 2011). Our data indicate that forskolin’s effects are independent of the cAMP targets PKA and Epac (Fig. S3), and provide evidence that the mechanism of action of podocyte survival involves attenuation of protein biosynthesis (Fig. 3). While (early) adaptive changes in protein translation are well-established in ER stress (Harding et al., 2001; Harding et al., 2000b), the regulation of chronic stress-associated protein biosynthesis by forskolin appears to be a mechanism for podocyte survival that has not been previously described.

Second, our studies show that GDC-0879 binds BRAF in podocytes to initiate MEK/ERK signaling and thus protect podocytes from a variety of cell death inducers (Fig. 5). These data extend the previously identified cell context-dependent activity of GDC-0879 in rapidly proliferating cancer cells (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2011), by revealing a pro-survival effect of this compound in non-proliferating, post-mitotic podocytes. Therefore, while in some cancer cells GDC-0879 activates MEK/ERK to promote proliferation, in post-mitotic podocytes activation of the same pathway promotes survival, by preventing injury-induced cell death. Despite evidence that GDC-0879 and another BRAF inhibitor (SB-682330) are efficient podocyte protectors, several other BRAF inhibitors (Dabrafenib, SB-590885) did not show the same efficacy. Another ATP-competitive BRAF inhibitor, PLX-4720, which appears to mediate the same paradoxical activation of MAPK signaling, albeit more weakly, in some cancer cells (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010), did not rescue podocytes from injury. It is known that different type 1 BRAF inhibitors have distinct effects on BRAF, affecting BRAF/BRAF and BRAF/CRAF dimerization as well as BRAF-MEK1 complex stability (Haling et al., 2014). It is also worth noting that the paradoxical activation of the MAPK pathway by GDC-0879 (and more weakly by PLX-4720) was only found in 50% of all cancer cell lines tested (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010), suggesting that the events downstream of RAF binding by each of these chemically distinct compounds are complex and cell-context dependent.

Our data also provide a hint that GDC-0879 may act in podocytes not only through BRAF but also through ARAF (but not CRAF). This is in contrast to some cancer cells, where BRAF-CRAF dimers have been implicated in the paradoxical activation of MEK/ERK (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2011). CRAF is in fact the most potent effector of GDC-0879 in some cancer cell lines (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010), whereas it appears to play no role in the mechanism of action of GDC-0879 in podocytes. On the other hand, ARAF homodimers have also been implicated in MAPK pathway activation and cell migration in some cancer cells (Mooz et al., 2014). We speculate that both BRAF and ARAF may be induced to play a role in injured podocytes, though further studies will be needed to clarify the significance of this finding. Similarly, while we have identified an important protective role for MEK/ERK signaling in podocytes, the downstream events that confer protection from cell death are not well understood. There is some evidence that the activity of certain MAPK kinases, such as Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 kinase may be harmful to podocytes (Martineau et al., 2004), which again suggests that the specific cell context may be critical to understanding the role of different members of this kinase family for podocyte health and disease.

In conclusion, our data suggest that GDC-0879 and forskolin promote podocyte survival from several different cell death inducers (Fig. 5). Since podocyte death is a critical tipping point in the development and progression of many kidney diseases (Wharram et al., 2005; Wiggins, 2007), and since drug discovery for kidney diseases has been stagnant for more than 40 years (Brenner, 2016; Breyer and Susztak, 2016), our approach of repurposing a compound such as GDC-0879 to promote podocyte survival has important clinical implications. While we must confirm the protective actions of GDC-0879 in vivo, this study validates the podocyte as the cell of choice for future HTS campaigns, and reveals GDC-0879 as an excellent starting point for the development of targeted, podocyte-protective therapies.

SIGNIFICANCE

Podocyte death is a critical event in the progression of many chronic kidney diseases. Here we established and applied a high throughput podocyte viability assay and identified GDC-0879 as a podocyte-protective drug. The protective action of GDC-0879 was linked to restored MAPK signaling. This study validates the podocyte as the cell of choice for future HTS campaigns, and reveals GDC-0879 as a starting point for the development of targeted, podocyte-protective therapies.

STAR+ METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Anna Greka (agreka@bwh.harvard.edu or agreka@broadinstitute.org)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Immortalized murine podocytes (see key resources table) were cultured as previously described (Mundel et al., 1997; Shankland et al., 2007). Briefly, conditionally immortalized podocytes were cultured under permissive conditions (33°C) in RPMI–1640 (#21875, ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS (#10270, ThermoFisher Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (#15140, ThermoFisher Scientific) and interferon–γ on type I collagen. Induction of differentiation is mediated by a thermo shift to 37°C without interferon–γ in 6–well plates (apoptosis assays, and mRNA isolation,) and 10cm dishes (protein isolation). Experiments were performed at day 11 of differentiation. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM (#41965, ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

Basic information of SIV-infected Chinese rhesus macaques on antiretroviral therapy

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CREB | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9197, RRID:AB_331277 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-P-CREB | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9198, RRID:AB_2561044 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-EPAC1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4155, RRID:AB_1903962 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-BiP | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3177, RRID:AB2119845 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Ubiquitin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3933, RRID:AB_2180538 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ATF4 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#11815, RRID:AB_2616025 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ARAF | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#75804, RRID: N/A |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-BRAF | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#14814, RRID: N/A |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CRAF | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#53745, RRID: N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-P-p42/44 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9101, RRID:AB_331646 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-P-MEK1/2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9121, RRID:AB_331648 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-CHOP (GADD153) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-7351, RRID:AB_627411 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-GADD34 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-825, RRID:AB_2168847 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Calnexin | Abcam | Cat#ab22595, RRID:AB_2069006 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH | EMD Millipore | Cat#MAB374, RRID:AB_2107445 |

| Annexin V, Alexa Fluor™ 647 conjugate | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#A23204, RRID:AB_2341149 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Thapsigargin | EMD Millipore | Cat#586005 |

| GSK2656157 | EMD Millipore | Cat#504651 |

| Lactacystin | EMD Millipore | Cat#426100 |

| Forskolin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F6886 |

| Cycloheximide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C1988 |

| Tunicamycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T7765 |

| Brefeldin A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#B6751 |

| Staurosporine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#S6942 |

| Adriamycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#D1515 |

| Palmitic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P9767 |

| Fatty acid-free BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A8806 |

| IC 261 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#I0658 |

| SL0101 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#559285 |

| GDC-0879 | APExBio | Cat#A5071 |

| Sobrafenib | APExBio | Cat#A3009 |

| Dabrafenib | APExBio | Cat#B1407 |

| SB590885 | APExBio | Cat#B1406 |

| PLX-4720 | APExBio | Cat#A3016 |

| Vemurafenib | APExBio | Cat#A3004 |

| Selumetinib | APExBio | Cat#A8207 |

| PD0325901 | APExBio | Cat#A3013 |

| Trametinib | APExBio | Cat#A3018 |

| U0126-EtOH | APExBio | Cat#A1337 |

| Necrostatin-2 | APExBio | Cat#A3652 |

| Propidium iodide | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#P3566 |

| Polybrene | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TR-1003-G |

| Recombinant mouse interferon gamma | Cell Sciences | Cat#CRI001B |

| Type I collagen | Corning | Cat#354236 |

| Fugene | Promega | Cat#E2311 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Click-IT™ AHA (L-Azidohomoalanie) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C10102 |

| Click-IT™ Tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) Protein Analysis | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C33370 |

| CellTiter–Glo® Luminescent Cell viability assay | Promega | Cat#7572 |

| 2x GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix | Promega | Cat#A6001 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Microarray dataset | Fig. 3A | GEO Submission GSE106172 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE106172) |

| Proteomics dataset | Fig. 3A | MassIVE Accession number MSV000081651 (ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000081651) |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Conditionally immortalized murine podocytes | (Mundel et al., 1997) | RRID:CVCL_AS86 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer sequences | Table S1 | N/A |

| shRNA sequences | Table S1 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GSEAPreranked | GenePattern platform, Broad institute | http://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern/modules/docs/GSEAPreranked/1 |

| Genedata Screener version 13.0.0 | Genedata | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Compound libraries | ||

| Selleck Bioactive Compound library | Selleck Chemicals; Broad institute (1649 compounds) | N/A |

| Published kinase inhibitor set (PKIS) | GSK; Broad institute (367 compounds) | N/A |

METHOD DETAILS

HTS podocyte viability assay

At day 11 of differentiation, podocytes were trypsinized, re–plated in collagen I–coated 384-well plates at a density of 4’000–8’000 cells per well and recovered for 48 hours before the experiment. Treatment with 2.5μM thapsigargin (EMD Millipore) in a total volume of 30 μl, and in the presence of the individual compounds (see key resources table for library details) was applied for 96 hours. Each small molecule was tested in duplicate. Cell viability was determined by measuring relative ATP levels in an EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer) using the CellTiter–Glo® Luminescent Cell viability assay (see key resources table) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Positive and negative control cells were DMSO alone and thapsigargin in DMSO, respectively. Compounds were considered as hits (protective effect on thapsigargin–induced cell death) when both samples individually passed the 3σ threshold (hit: replicate1 ≥ thapsigargingargin±3σ ≤ replicate2).

Cell death analysis

Podocytes were treated as indicated in text. Palmitic acid complexed to BSA was prepared as described (Sieber et al., 2010; Sieber et al., 2013). Annexin V and PI staining was performed as previously reported (Sieber et al., 2010; Sieber et al., 2013). In brief, the cells were trypsinized, washed once with PBS, and resuspended in 120 μl annexin V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). 100 μl of the cell suspension was used for the staining procedure. Alexa–647 annexin V was applied for 15 min at room temperature at a dilution of 1:40 and an additional 400 μl of annexin V binding buffer and propidium iodide (1:5000) were added before analysis. 20,000 – 25,000 cells were analyzed by flow cytometery (BD LSRFortessa, BD Biosciences) (Asanuma et al., 2007). Annexin V positive (annexin V+/PI− and annexin V+/PI+) cells were counted as dead cells. For every single experiment involving shRNA-mediated gene silencing the knockdown efficiency was confirmed (data inclusion criteria).

Lentivirus production

Lentivirus production in HEK293 cells and podocyte transduction were performed as previously reported (Asanuma et al., 2007; Sieber et al., 2010; Sieber et al., 2013). In brief, HEK293 cells (40–60% confluency in a 10cm tissue culture dish) were triple-transfected with the two helper plasmids pCMV-dR8.91 (3.8μg) and VSV-G (0.38μg), and the shRNA-containing pLKO.1 (3.8μg) using Fugene (24μl). The transfection media (DMEM, 10% FBS) was replaced 8–12 hours post transfection with fresh antibiotics-containing media. Virus was harvested 60 hours later (68–72 hours post transfection). See key resources table for shRNA details.

Podocytes were transduced in the presence of 4μg/ml Polybrene for 8–16 hours and experiments were performed at least 4 days after viral transduction. shRNA sequences are listed in key resources table.

Western blot

Western blotting was done as previously reported (Sieber et al., 2010; Sieber et al., 2013). In brief, proteins (in RIPA lysis buffer) were separated in by 4–12%, 10%, or 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Prior to primary antibody incubation (in blocking solution, overnight at 4ºC) membranes were blocked for 30 minutes (5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.2% Tween). Antibodies against CREB1, P-CREB1, EPAC1, BIP, Ubiquitin, ATF4, CHOP, ARAF, BRAF, CRAF, GADD34, P-p42/44, P-MEK1/2, and GAPDH were applied at dilutions of 1:1000, 1:500, 1:1’000, 1:1’000, 1:1’000, 1’1000, 1:1’000, 1:1’000, 1:1’000, 1:1’000, 1:500, 1:1’000, 1:1’000 and 1:10’000, respectively. Secondary antibodies were applied for 1 houre at room temperature. The immunoblots were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE healthcare) on autoradiography films (Labscientific Inc). See key resources table for antibody details. Equal Coomassie staining of membranes indicating successful transfer and equal protein loading served as data inclusion criteria.

Quantitative real–time RT–PCR

Total RNA extraction (#74104, Qiagen), cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR were performed as reported (Sieber et al., 2013). Real-time PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μl using 2× GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and 0.75 μM of the particular primers. Gapdh was used as internal control. The experiments were carried out in a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min and 40 cycles of amplification (95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec). Primer sequences are listed in key resources table. Analysis of dissociation curves confirmed a single PCR product (data inclusion criteria).

Protein translation analysis by metabolic labeling

Podocytes were incubated in methionine-free media (#A14517, Life Technologies) for hour prior to treatment initiation. Treatment was carried out in methionine-free media in the presence of 50μM of the methionine analog L-azidohomoalanine (see key resources table). Specifically, in the experiment evaluating protein biosynthesis after injury, podocytes were treated with thapsigargin in the presence or absence of the indicated compounds. At 9 hours of treatment podocytes were incubated in methionine-free media (plus indicated compounds, no thapsigargin) for 1 hour, which was followed by a 15 hour incubation allowing L-azidohomoalanine incorporation (see above). The 15 hour treatment was carried out in the presence of the indicated compounds (no thapsigargin). Cells were lysed in 1% SDS, 50mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The viscosity of the lysates was strongly decreased by three freeze/thaw cycles. Subsequently, the lysates were vortexed for 5 min at 4°C and spun down for 5 min at 18’000×g at 4°C. Click-iT® labeling (50–80μg protein) with tetramethylrodamine (see key resources table) was performed according to the manufacturers protocol. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and de novo synthesized proteins were detected under UV (300nm). After UV detection, the gel was fixed and stained with 1% (w/v) Coomassie to check equal loading.

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

CETSAs were performed as described here (Jafari et al., 2014). In brief, podocytes were treated in the presence or absence of GDC-0879 for 2 hours, collected (trypsinized), washed in 1× PBS, resuspended in 1× PBS (plus protease inhibitors) and distributed in 0.2ml PCR tubes (100μl; 200’000 cells). The cells were incubated at their designated temperatures for 3min, at 25ºC for 3min and snap frozen immediately after. Cells were lysed by three freeze/thaw cycles and spun at 20’000×g for 20min (4ºC) to remove precipitated protein. The supernatant was analysed by Western blot to examine thermal stability of BRAF.

Immunocytochemistry

Podocytes grown in 35mm tissue culture dishes were fixed for 5 min in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4% Sucrose (Sigma), and permeabilized for 10 min in 0.3% Triton X–100 (Sigma-Aldrich, in PBS). The blocking solution contained 2% FCS (ThermoFisher Scientific), 2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.2% Fish–gelatine (Sigma-Aldrich, in PBS) for 30 min. Antibodies were incubated for 1 hour in blocking. Alexa 488–labeled secondary antibodies against mouse (#A11001, ThermoFisher Scientific) or rabbit (#A11034, ThermoFisher Scientific) IgG were applied at 1:500 in blocking solution for 1 hour. Cells were mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (#S3023, Dako), and imaged by confocal microscopy. Images were acquired in a blinded manner.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was isolated as described above and microarray was performed by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Genomics and Microarray core facility using the Mouse Gene 2.0 ST Array (Affymetrix). Analysis of probe level data (Cel files) was conducted using the ‘affy’ package in R (Gautier et al., 2004). Background correction, normalization and expression calculation was performed with the rma function using default parameters. Differential gene expression was calculated using the empirical Bayes method. Genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed.

Proteomics

Total protein was isolated from podocytes treated with 2.5μM thapsigargin in the presence or absence of 10μM forskolin for 16 hours. Vehicle (DMSO)-treated cells were used as controls. Protein lysates, 2 replicates per condition, were prepared in 8M urea, 75mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA in 50mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 2 μg/mL aprotinin (#A6103, Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/mL Leupeptin (#11017101001, Roche), and 1 mM PMSF (#78830, Sigma-Aldrich) and proteomics was performed by the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School Proteomics Platform as previously reported (Mertins et al., 2016; Mertins et al., 2013; Mertins et al., 2014) by using TMT labeling.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Representative experiments of at least three repeats are shown. Statistical significance and number of replicates are indicated in the respective figure legends. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significance of differences (based on normal distribution assumptions) was calculated with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post–hoc tests using Prism 6 program. The significance level was set to p < 0.05.

Microarray. Differential gene expression was calculated using the empirical Bayes method. Genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Gene set enrichment analysis (Subramanian et al., 2005) was conducted on the GenePattern platform (Reich et al., 2006) using the GSEAPreRanked module with a ranked list of differentially expressed genes (microarray) and proteins (proteomics).

Compound synergy was determined using the Bliss independence synergy model and Loewe additivity model applied in Genedata Screener version 13.0.0.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Gene profiling data deposited GEO Submission GSE106172 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE106172) Proteomics data files deposited MassIVE Accession number MSV000081651 (ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000081651)

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HTS identifies the BRAFV600E inhibitor GDC-0879 as a podocyte protective drug

GDC-0879 restores MAPK signaling in podocytes

GDC-0879 protects podocytes from an array of cell death inducers

The podocyte is the target of choice for the development of kidney therapeutics

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicola Tolliday, Kate Hartland, Patrick McCarren, Bridget Wagner and Stuart Schreiber at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard for their generous advice.

J.S. was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation fellowships PBBSP3–144160 and P300P3–151739, N.W. by a Deutsche Forschungs Gesellschaft fellowship (WI 4612/1-1), A.W.J by a Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 31003A-144112/1, P.M. by NIH grants DK057683, DK062472, DK091218, and A.G. by NIH grants DK099465, DK103658, and DK095045.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.S. designed and performed the experiments; M.R., S.M., J.Sch., and J.Z. performed experiments; J.S., N.W., A.C., A.M., J.G., A.W.J., N.U., O.A., S.C., P.M. and A.G. analyzed the data; P.M., A.W.J., and A.G. supervised the project, J.S. and A.G. wrote the paper; A.G. is responsible for the contents of this manuscript; all authors read and agreed with the contents of the manuscript.

Competing financial interests.

P.M. declares equity in Goldfinch Biopharma. A.G. has a financial interest in Goldfinch Biopharma, which was reviewed and is managed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. A.G. also declares consultation services for Bristol Myers Squibb and Third Rock Ventures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asanuma K, Campbell KN, Kim K, Faul C, Mundel P. Nuclear relocation of the nephrin and CD2AP-binding protein dendrin promotes apoptosis of podocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10134–10139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700917104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bek MF, Bayer M, Müller B, Greiber S, Lang D, Schwab A, August C, Springer E, Rohrbach R, Huber TB, et al. Expression and function of C/EBP homology protein (GADD153) in podocytes. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:20–32. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L. Back to the Future: Paving the Way for the Next Generation of Renal Therapeutics. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer MD, Susztak K. Developing Treatments for Chronic Kidney Disease in the 21st Century. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36:436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichowski K, Jänne PA. Drug discovery: inhibitors that activate. Nature. 2010;464:358–359. doi: 10.1038/464358a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha DA, Ladrière L, Ortis F, Igoillo-Esteve M, Gurzov EN, Lupi R, Marchetti P, Eizirik DL, Cnop M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists protect pancreatic beta-cells from lipotoxic endoplasmic reticulum stress through upregulation of BiP and JunB. Diabetes. 2009;58:2851–2862. doi: 10.2337/db09-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agati VD, Kaskel FJ, Falk RJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2398–2411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1106556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. affy--analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloerich M, Bos JL. Epac: defining a new mechanism for cAMP action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:355–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haling JR, Sudhamsu J, Yen I, Sideris S, Sandoval W, Phung W, Bravo BJ, Giannetti AM, Peck A, Masselot A, et al. Structure of the BRAF-MEK complex reveals a kinase activity independent role for BRAF in MAPK signaling. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JD, Grina J, Newhouse B, Welch M, Topalov G, Littman N, Callejo M, Gloor S, Martinson M, Laird E, et al. Potent and selective pyrazole-based inhibitors of B-Raf kinase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4692–4695. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Novoa I, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Urano F, Jousse C, Ron D. Translational regulation in the cellular response to biosynthetic load on the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2001;66:499–508. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000a;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000b;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, Ludlam MJ, Stokoe D, Gloor SL, Vigers G, et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature08833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich KP, Herter S, Tien J, Wong L, Berry L, Chan J, O’Brien C, Modrusan Z, Seshagiri S, Lackner M, et al. Antitumor efficacy of the novel RAF inhibitor GDC-0879 is predicted by BRAFV600E mutational status and sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway suppression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3042–3051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari R, Almqvist H, Axelsson H, Ignatushchenko M, Lundbäck T, Nordlund P, Martinez Molina D. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:2100–2122. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382:260–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1389–1398. doi: 10.1172/JCI16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijima Y, Ogunbunmi E, Fleischer S. Drug action of thapsigargin on the Ca2+ pump protein of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22912–22918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Nian C, Widenmaier S, McIntosh CH. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide-mediated up-regulation of beta-cell antiapoptotic Bcl-2 gene expression is coordinated by cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) and cAMP-responsive CREB coactivator 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1644–1656. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00325-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tao H, Xie K, Ni Z, Yan Y, Wei K, Chuang PY, He JC, Gu L. cAMP signaling prevents podocyte apoptosis via activation of protein kinase A and mitochondrial fusion. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Hendershot LM. The unfolding tale of the unfolded protein response. Cell. 2001;107:827–830. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00623-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau LC, McVeigh LI, Jasmin BJ, Kennedy CR. p38 MAP kinase mediates mechanically induced COX-2 and PG EP4 receptor expression in podocytes: implications for the actin cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F693–701. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00331.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertins P, Mani DR, Ruggles KV, Gillette MA, Clauser KR, Wang P, Wang X, Qiao JW, Cao S, Petralia F, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;534:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature18003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertins P, Qiao JW, Patel J, Udeshi ND, Clauser KR, Mani DR, Burgess MW, Gillette MA, Jaffe JD, Carr SA. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat Methods. 2013;10:634–637. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertins P, Yang F, Liu T, Mani DR, Petyuk VA, Gillette MA, Clauser KR, Qiao JW, Gritsenko MA, Moore RJ, et al. Ischemia in tumors induces early and sustained phosphorylation changes in stress kinase pathways but does not affect global protein levels. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:1690–1704. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.036392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooz J, Oberoi-Khanuja TK, Harms GS, Wang W, Jaiswal BS, Seshagiri S, Tikkanen R, Rajalingam K. Dimerization of the kinase ARAF promotes MAPK pathway activation and cell migration. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra73. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Greka A. Developing therapeutic ‘arrows’ with the precision of William Tell: the time has come for targeted therapies in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:388–392. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Zúñiga Mejía Borja A, Pavenstädt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:248–258. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, Shi H, Atefi M, Titz B, Gabay MT, et al. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480:387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GenePattern 2.0. Nat Genet. 2006;38:500–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0506-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamon KB, Padgett W, Daly JW. Forskolin: unique diterpene activator of adenylate cyclase in membranes and in intact cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:3363–3367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankland SJ, Pippin JW, Reiser J, Mundel P. Podocytes in culture: past, present, and future. Kidney Int. 2007;72:26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber J, Lindenmeyer MT, Kampe K, Campbell KN, Cohen CD, Hopfer H, Mundel P, Jehle AW. Regulation of podocyte survival and endoplasmic reticulum stress by fatty acids. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F821–829. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00196.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber J, Weins A, Kampe K, Gruber S, Lindenmeyer MT, Cohen CD, Orellana JM, Mundel P, Jehle AW. Susceptibility of podocytes to palmitic acid is regulated by stearoyl-CoA desaturases 1 and 2. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:735–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schadewijk A, van’t Wout EF, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS. A quantitative method for detection of spliced X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1) mRNA as a measure of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2012;17:275–279. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0306-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RF, Abdel-Majid RM, Barnett MW, Willis BS, Katsnelson A, Gillingwater TH, McKnight GS, Kind PC, Neumann PE. Involvement of protein kinase A in patterning of the mouse somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5393–5401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0750-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharram BL, Goyal M, Wiggins JE, Sanden SK, Hussain S, Filipiak WE, Saunders TL, Dysko RC, Kohno K, Holzman LB, et al. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2941–2952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins RC. The spectrum of podocytopathies: a unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1205–1214. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z, He L, Takemoto M, Jalanko H, Chan GC, Storm DR, Betsholtz C, Tryggvason K, Patrakka J. Glomerular podocytes express type 1 adenylate cyclase: inactivation results in susceptibility to proteinuria. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;118:e39–48. doi: 10.1159/000320382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.