Abstract

Prostate cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. Hypoxia-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), driven by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), is involved in cancer progression and metastasis. The present study was designed to explore the role of propofol in hypoxia-induced resistance of prostate cancer cells to docetaxel. We used the Cell Counting Kit-8 and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation assay to measure cell viability and cell proliferation, respectively, in prostate cancer cell lines. Then, we detected HIF-1α, E-cadherin, and vimentin expression using western blotting. Propofol reversed the hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in the prostate cancer cell lines. Propofol not only decreased hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression, but also reversed hypoxia-induced EMT by suppressing HIF-1α. Furthermore, small interfering RNA–mediated silencing of HIF-1α reversed the hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance, although there was little change in docetaxel sensitivity between the hypoxia group and propofol group. The induction of hypoxia did not affect E-cadherin and vimentin expression, and under the siRNA knockdown conditions, the effects of propofol were obviated. These data support a role for propofol in regulating EMT in prostate cancer cells. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that propofol plays an important role in hypoxia-induced docetaxel sensitivity and EMT in prostate cancer cells and that it is a potential drug for overcoming drug resistance in prostate cancer cells via HIF-1α suppression.

1. Introduction

Hypoxia is common in the microenvironment of solid tumors and is associated with tumor invasion, distant metastasis, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [1–3]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) regulates the expression of proteins that increase oxygen delivery, which enables cells to survive in oxygen-deficient conditions [4]. HIF is a heterodimer consisting of the HIF-1α and HIF-1β transcription factors [5]. HIF-1α is the most important hypoxia-induced transcription factor and has multiple functions in tumor progression, including changes in the aggressive behavior of the tumor [6]. Moreover, HIF-1α plays a role in prostate cancer cell EMT and migration [7]. EMT is involved in many crucial cancer cell functions, including tissue reorganization, tumorigenesis, cancer recurrence, and metastasis [8]. EMT is characterized by the combined loss of epithelial cell junction proteins such as E-cadherin and the gain of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin or fibronectin [9]. It has become increasingly clear over recent years that EMT, a critical developmental process, plays a major role in cancer progression [10, 11]. Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death among men in developed countries [12]. Docetaxel is produced semisynthetically from the needles of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia) [13]. In recent years, docetaxel has been considered standard first-line therapy in prostate cancer cases [14]; however, it confers only a modest survival advantage, as patients eventually acquire docetaxel resistance [15]. However, the mechanisms involved in hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance remain unclear. Therefore, it is urgent that this mechanism be elucidated.

Propofol (2, 6-diisopropylphenol), a general sedative and hypnotic agent, is widely used for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia [16]. Accumulating evidence suggests that propofol has several nonanesthetic effects [17]. Recently, it was reported that propofol has potential anticancer properties, such as inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, and metastasis and inducing cancer cell apoptosis [18–20]. Recent studies have shown that propofol can suppress cell invasion and reverse EMT by decreasing HIF-1α expression in lipopolysaccharide-treated non-small cell lung cancer cells [21]. Furthermore, propofol inhibits viability and induces apoptosis in lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cervical cancer cells [22–24]. However, this process has not been completely elucidated in prostate cancer cell lines.

In this study, we found that propofol could reverse hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells by reversing EMT via HIF-1α inhibition. The stronger sensitivity of the cells to the combined docetaxel and propofol treatment as compared with docetaxel-only treatment that we observed shows that propofol sensitized the prostate cancer cells to the hypoxia-induced docetaxel inhibitory effect.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Induction of Hypoxia

The human prostate cancer cell lines PC3, DU145, and 22RV1 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 21% O2 and 5% CO2. For hypoxic culture, the cells were placed in a hypoxic incubator (1% O2, 5% CO2) at 37°C for 6 h. HIF-1α small interfering RNA (siRNA) and negative siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Propofol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

We used Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) to determine the cell viability rate. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in 100 μL maintenance medium and cultured for 24 h. The culture medium was replaced with 10% FBS–medium containing the drugs (docetaxel (μM): 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100; propofol (μM): 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320). After 48-h incubation, 10 μL CCK-8 solution was added, the cells were incubated for 3 h, and then the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an MRX II microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, USA). The cell viability rate was calculated as a percentage of untreated controls.

2.3. HIF-1α siRNA Transfection

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at (1 × 105 cells/well) and transfected with HIF-1α siRNA or negative siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The transfection medium (Opti-MEM; Gibco) was removed and replaced with complete medium 6 h after transfection. All experiments were performed for 24 h after transfection and repeated three times.

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was used to detect protein expression. Briefly, the cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min on ice. Then, the lysates were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to determine the protein concentrations. Protein (20 μg) from each sample was separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies (anti–E-cadherin, anti-vimentin, anti–HIF-1α, diluted 1 : 1000 in TBST; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Then, the membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 2000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) for 2 h at 37°C. β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as the loading control. Protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Biological Industries, Beit HaEmek, Israel). Gray value analysis of the protein bands was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.5. 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Analysis

The EdU incorporation assay was used to calculate DNA incorporation/synthesis. Measurement of the rate of cell proliferation inhibition was assessed using a Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to a procedure described previously [25].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using a t-test or one- or two-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's or Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Hypoxia Induced Docetaxel Resistance in Prostate Cancer Cells

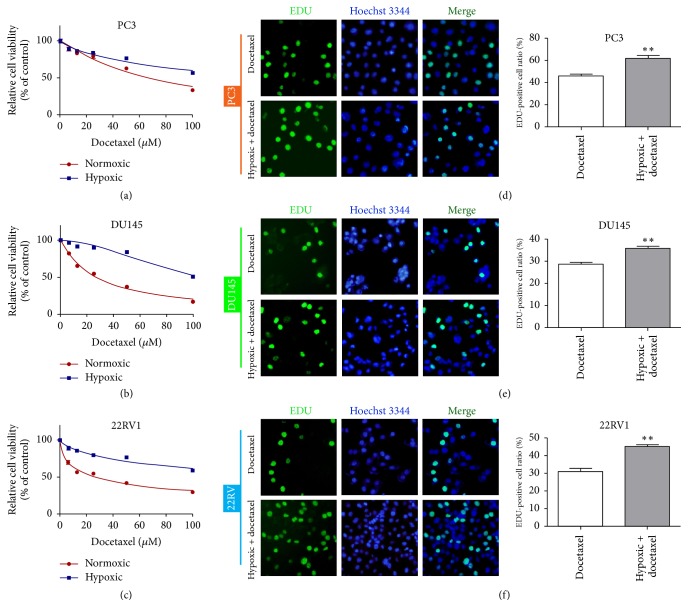

To investigate prostate cancer cell sensitivity to docetaxel under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, we used the CCK-8 assay to measure cell viability. Cell viability was significantly increased in hypoxic conditions compared with normoxia (Figures 1(a)–1(c), Table 1), confirming that hypoxia induces docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells. The EdU incorporation assay was used to measure the effects of docetaxel on prostate cancer cell proliferation following 48-h treatment under hypoxic conditions. Docetaxel treatment in hypoxia enhanced cell proliferation (P < 0.01 versus docetaxel) (Figures 1(d)–1(f)).

Figure 1.

Hypoxia-induced prostate cancer cell resistance to docetaxel. (a–c) CCK-8 detection of viability of prostate cancer cells in normoxic or hypoxic conditions after docetaxel treatment. (d–f) EdU assay detection of the proliferation rate of prostate cancer cells treated with docetaxel under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus docetaxel.

Table 1.

The cell viability of PC cells treated with different concentrations of docetaxel under normoxia and hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | Hypoxic | |

| PC3 | 66.26 (58.30 to 74.22) | 169.6 (123.9 to 215.2) |

| DU145 | 27.03 (25.46 to 28.59) | 106.9 (97.00 to 116.8) |

| 22RV1 | 26.73 (22.92 to 30.54) | 208.7 (130.2 to 287.2) |

IC50 values show docetaxel concentration [μM, mean (95% confidence intervals)].

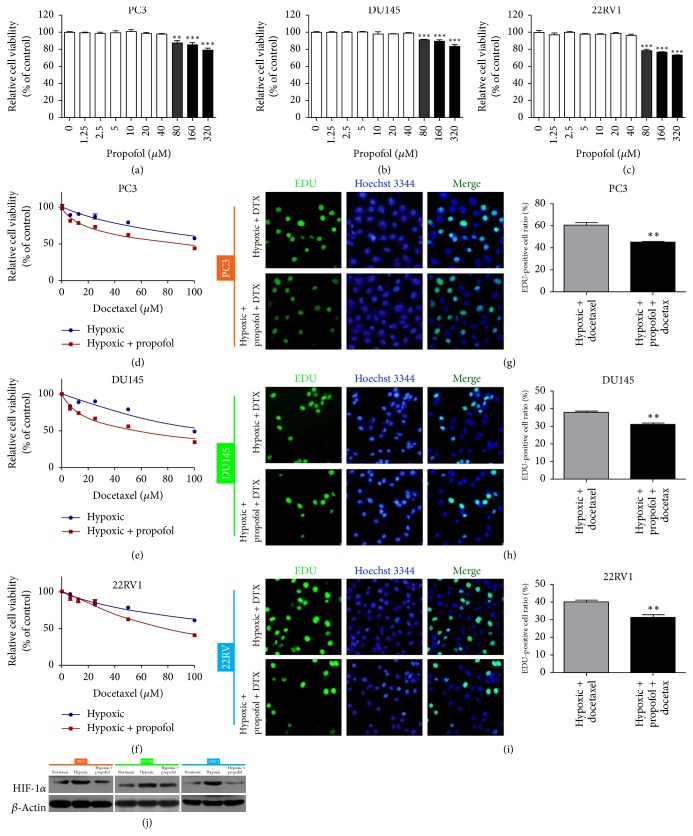

3.2. Propofol Reversed Hypoxia-Induced Docetaxel Resistance in Prostate Cancer Cells

To evaluate whether propofol could reverse hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance, we used CCK-8 to measure the viability of cells treated with docetaxel alone or with docetaxel combined with propofol under hypoxic conditions. Initially, 80, 160, or 320 μM propofol significantly inhibited cell viability compared with 0 μM propofol (Figures 2(a)–2(c)). Then, we selected the highest concentration of propofol (40 μM) that caused little effect for further analyses. Surprisingly, docetaxel sensitivity was enhanced after combination with propofol (Figures 2(d)–2(f), Table 2). The EdU incorporation assay indicated that the EdU-positive cell ratio was significantly decreased compared to the hypoxia + docetaxel group (P < 0.01) (Figures 2(g)–2(i)). Then we detected HIF-1α expression in prostate cancer cells under hypoxic conditions and with or without propofol and found that hypoxia induced HIF-1α upregulation, whereas propofol suppression of HIF-1α expression reversed this result (Figure 2(j), Table 3). These findings demonstrate that propofol reverses hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 2.

Propofol reversed hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells. (a–c) Human prostate cancer cells were treated with propofol for 48 h, and cell viability was measured using CCK-8. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus 0 μM. (d–f) Cell viability was measured in prostate cancer cells treated with docetaxel with or without propofol (40 μM) under hypoxic conditions for 48 h. (g–i) EdU assay detection of the proliferation rate of prostate cancer cells treated with docetaxel or docetaxel plus propofol under hypoxic conditions. Histograms represent the positive cell rate (%). ∗∗P < 0.01 versus hypoxia + docetaxel. DTX, docetaxel. (j) Western blotting detection of HIF-1α expression following propofol treatment under hypoxic or normoxic conditions.

Table 2.

The cell viability of PC cells treated with docetaxel alone or docetaxel plus propofol under hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | IC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic | Hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 159.1 (107.6 to 210.6) | 88.00 (69.51 to 106.5) |

| DU145 | 114.4 (86.92 to 141.9) | 54.45 (48.74 to 60.16) |

| 22RV1 | 179.4 (131.1 to 227.6) | 77.67 (67.55 to 87.79) |

IC50 values show docetaxel concentration [μM, mean (95% confidence intervals)].

Table 3.

The grey value of the HIF-1α protein treated with or without propofol under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | HIF-1α/β-actin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | Hypoxic | Hypoxic + Propofol | |

| PC3 | 0.448049 | 0.942486 | 0.508608 |

| DU145 | 0.420623 | 1.034483 | 0.698514 |

| 22RV1 | 0.439184 | 1.303041 | 0.549622 |

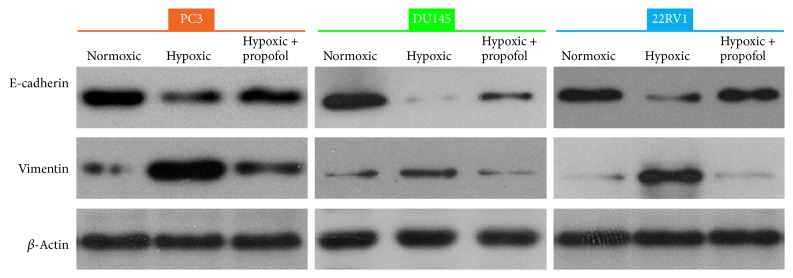

3.3. Propofol Partially Reversed Hypoxia-Induced EMT in Prostate Cancer Cells

To determine whether the mechanism of propofol reversed hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance is related to EMT, we detected E-cadherin and vimentin expression by western blotting. Hypoxia downregulated E-cadherin expression and increased vimentin expression in the cells. In addition, E-cadherin expression was increased and vimentin expression was decreased after propofol treatment as compared with the hypoxia-induced group, indicating that propofol can reverse hypoxia-induced EMT in prostate cancer cells (Figure 3, Tables 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Propofol partially reversed hypoxia-induced EMT. Western blot showing E-cadherin and vimentin expression in prostate cancer cells treated with or without propofol under hypoxic or normoxic conditions.

Table 4.

The grey value of the E-cadherin protein treated with or without propofol under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | E-cadherin/β-actin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | Hypoxic | Hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 1.167701 | 0.66641 | 0.906073 |

| DU145 | 0.972721 | 0.038215 | 0.421248 |

| 22RV1 | 0.641246 | 0.174243 | 0.555517 |

Table 5.

The grey value of the vimentin protein treated with or without propofol under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | Vimentin/β-actin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | Hypoxic | Hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 0.2797 | 1.436738 | 0.685475 |

| DU145 | 0.128068 | 0.335682 | 0.154392 |

| 22RV1 | 0.071099 | 0.741434 | 0.109708 |

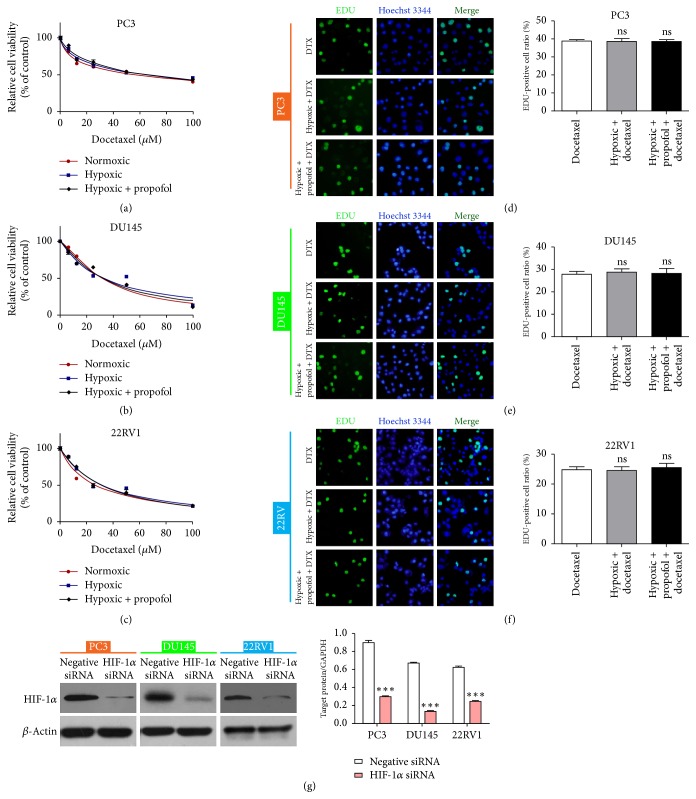

3.4. HIF-1α Knockdown Partially Reversed Hypoxia-Induced Docetaxel Resistance

Hypoxia promotes EMT by activating HIF-1α [26]. Although we had determined that propofol could reverse hypoxia-induced EMT in prostate cancer cells, it was unclear whether the effect of propofol was related to HIF-1α. We hypothesized that propofol affects hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells by regulating HIF-1α. To further examine this effect, we transfected HIF-1α siRNA into prostate cancer cells and then examined their viability following docetaxel treatment with or without propofol in hypoxic conditions or with docetaxel alone in normoxia; there was little change in the docetaxel resistance among the three groups (Figures 4(a)–4(c), Table 6). Furthermore, HIF-1α knockdown partially reversed the hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance (Figures 4(a)–4(c)). The proliferation-suppressing effect of docetaxel was verified by the EdU assay, although there was no significant difference among the groups (Figures 4(d)–4(f)). Western blotting was performed to determine knockdown efficiency (Figure 4(g)). The findings show that inhibiting HIF-1α reverses hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in PC cells.

Figure 4.

HIF-1α knockdown partially reversed hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance. (a–c) Cell viability assay quantification of prostate cancer cells treated with docetaxel with or without propofol under normoxic or hypoxic conditions following HIF-1α knockdown. (d–f) EdU assay detection of the proliferation rate of prostate cancer cells following HIF-1α knockdown and treatment with docetaxel, docetaxel plus propofol in hypoxia, or docetaxel alone in normoxia. (g) Western blot assessment of HIF-1α knockdown efficiency in hypoxia condition; histogram represents the average grey value of the HIF-1α protein. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus control. DTX, docetaxel; ns, not significant.

Table 6.

The cell viability of PC cells treated with docetaxel alone under normoxia or hypoxia conditions or docetaxel plus propofol under hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | IC50 (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | Hypoxic | Hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 55.73 (46.25 to 65.21) | 64.58 (54.11 to 75.05) | 65.54 (52.64 to 78.43) |

| DU145 | 31.44 (29.31 to 33.58) | 32.20 (27.81 to 36.59) | 31.63 (28.10 to 35.17) |

| 22RV1 | 26.61 (23.49 to 29.73) | 31.65 (27.96 to 35.35) | 31.10 (27.38 to 34.81) |

IC50 values show docetaxel concentration [μM, mean (95% confidence intervals)].

3.5. Propofol Played a Role in Prostate Cancer Cell Docetaxel Sensitivity by Decreasing HIF-1α

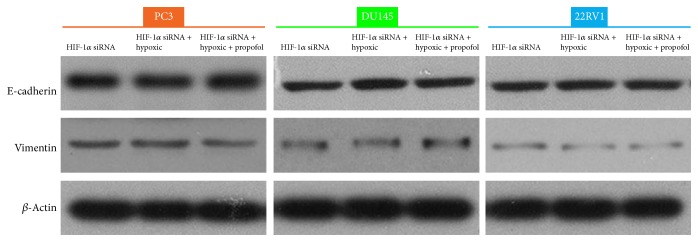

We determined that hypoxia induced E-cadherin downregulation and vimentin upregulation. To explore the mechanism underlying EMT and hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance due to HIF-1α overexpression in prostate cancer cells, we knocked down HIF-1α and examined E-cadherin and vimentin expression using western blotting. Interestingly, hypoxia did not affect E-cadherin and vimentin expression. However, the effects of propofol were blocked such that there was no significant change in the levels of expression of EMT markers between any of the groups (Figure 5(a), Tables 7 and 8).

Figure 5.

Propofol played a role in hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance by decreasing HIF-1α. Western blot showing E-cadherin and vimentin expression in HIF-1α–knockdown prostate cancer cells under hypoxia treated with or without propofol.

Table 7.

The grey value of the E-cadherin protein treated with or without propofol after knockdown of HIF-1α under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | E-cadherin/β-actin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α siRNA | HIF-1α siRNA + hypoxic | HIF-1α siRNA + hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 0.66447 | 0.64527 | 0.675951 |

| DU145 | 0.431083 | 0.4735 | 0.443874 |

| 22RV1 | 0.426146 | 0.465596 | 0.447101 |

Table 8.

The grey value of the vimentin protein treated with or without propofol after knockdown of HIF-1α under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

| Cell lines | Vimentin/β-actin | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α siRNA | HIF-1α siRNA + hypoxic | HIF-1α siRNA + hypoxic + propofol | |

| PC3 | 0.144313 | 0.152617 | 0.154287 |

| DU145 | 0.109956 | 0.107534 | 0.105961 |

| 22RV1 | 0.049789 | 0.048136 | 0.040924 |

4. Discussion

Docetaxel is more effective against progressive human prostate cancer than other conventional anticancer agents [27]. Unfortunately, drug resistance negatively impacts the effects of this treatment. The mechanisms involved in docetaxel resistance in hypoxia remain unclear, so further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

In clinical practice, propofol is commonly used in the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. An intravenously administered hypnotic agent, propofol, is widely used in all types of surgeries due to its short effect and rapid recovery. A variety of studies have illustrated its neuroprotective property [28, 29]. Recently, research has focused on its antitumor effect [30]. Several studies have shown that propofol can be used in combination with current clinical chemotherapeutic drug regimens such as gemcitabine or paclitaxel [31, 32]. Moreover, it had been proved that propofol works as an antioxidant and that propofol can act in an antioxidant capacity mainly on mitochondrial Complex I to decrease cellular ROS levels required to stabilize HIF [33]. In the present study, we hypothesized that propofol is involved in docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells. Western blotting and CCK-8 showed that hypoxia induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells, which is consistent with that reported for breast cancer cells in response to doxorubicin [34]. Docetaxel treatment in hypoxic condition enhanced prostate cancer cell proliferation. However, combining docetaxel with propofol enhanced docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer cells.

EMT is considered an essential step in cancer progression and metastasis because it allows cancer cells to migrate, invade the surrounding tissues, and escape into the bloodstream, such that primary tumors can metastasize to other organs [35]. Some microenvironmental factors, such as hypoxia, are also involved in EMT during malignant cell transformation [36]. Hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression enhances EMT and induces resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, promoting tumor migration and invasion. EMT may be a key process regulating resistance to chemotherapy in malignant tumors [37, 38]. NSCLC cells with an epithelial phenotype are more sensitive to chemotherapy than those with a mesenchymal phenotype. We proved that combined docetaxel with propofol enhanced sensitivity under hypoxia condition in prostate cancer cells, and it was related to HIF-1α expression. Then western blot analysis showed that hypoxia induced HIF-1α upregulation compared with normoxia, but propofol induced the HIF-1α downregulation as compared with hypoxia. Next, we attempted to identify whether propofol has EMT-inhibiting capability. We directly evaluated the effect of propofol on several hypoxia-mediated EMT parameters, including E-cadherin and vimentin expression levels. We found that propofol inhibited the hypoxia-induced EMT and reversed the hypoxia-induced E-cadherin downregulation and vimentin upregulation. Taken together, these data indicate that propofol reverses hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells by preventing EMT. HIF-1α is a key transcription factor induced by hypoxia [39] and it activates the transcription of genes implicated in tumor angiogenesis, cell survival, and resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs [40–42]. Thus, inhibiting HIF-α activity or EMT might be a new target for innovative mechanism-based drug discovery for cancer disease. We transfected HIF-1α siRNA into prostate cancer cells to knock down HIF-1α expression and found that hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance disappeared and that propofol did not reverse docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells after HIF-1α siRNA transfection.

In conclusion, we have established that propofol plays an important role in hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells. Propofol reversed hypoxia-induced docetaxel resistance through EMT by inhibiting hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression. These results indicate that propofol has potential as a therapeutic agent for improving prostate cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Clinical Scientific Research Fund Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2015ZYC-A78).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rankin E. B., Giaccia A. J. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science. 2016;352(6282):175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza G. L. Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2012;33(4):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y., Liu Y., Yan X., et al. HIFs enhance the migratory and neoplastic capacities of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by promoting EMT. Tumor Biology. 2014;35(8):8103–8114. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Do N. Y., Shin H.-J., Lee J.-E. Wheatgrass extract inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 cells. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2017;11(2):83–89. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2017.11.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Vaupel P. The role of hypoxia-induced factors in tumor progression. The Oncologist. 2004;9(supplement 5):10–17. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90005-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahimi-Horn M. C., Bellot G., Pouysségur J. Hypoxia and energetic tumour metabolism. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2011;21(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo Y., Lan L., Jiang Y.-G., et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and migration of prostate cancer stem cells is driven by cancer-associated fibroblasts in an HIF-1alpha/beta- catenin-dependent pathway. Molecules and Cells. 2013;36(2):138–144. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiery J. P., Sleeman J. P. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7(2):131–142. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiery J. P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2003;15(6):740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grünert S., Jechlinger M., Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(8):657–665. doi: 10.1038/nrm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Their J. P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumor progression. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(6):442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H., Liu T., Guo J., et al. Brefeldin A enhances docetaxel-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in monolayer and 3D cultures. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2017;27(11):2286–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francini E., Sweeney C. J. Docetaxel activity in the era of life-prolonging hormonal therapies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. European Urology. 2016;70(3):410–412. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Wei H., Wang J., et al. Electropolymerized polyaniline/manganese iron oxide hybrids with an enhanced color switching response and electrochemical energy storage. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2015;3(41):20778–20790. doi: 10.1039/c5ta04439a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yip G. M. S., Chen Z.-W., Edge C. J., et al. A propofol binding site on mammalian GABAA receptors identified by photolabeling. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9(11):715–720. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasileiou I., Xanthos T., Koudouna E., et al. Propofol: a review of its non-anaesthetic effects. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;605(1–3):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L., Wang N., Zhou S., Ye W., Jing G., Zhang M. Propofol induces proliferation and invasion of gallbladder cancer cells through activation of Nrf2. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;31(1, article no. 66) doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z. T., Gong H. Y., Zheng F., Liu D. J., Yue X. Q. Propofol suppresses proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells via downregulation of microRNA-221 expression. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2015;14(3):8117–8124. doi: 10.4238/2015.July.17.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z. T., Gong H. Y., Zheng F., Liu D. J., Dong T. L. Propofol suppresses proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by upregulating microrna-133a expression. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2015;14(3):7529–7537. doi: 10.4238/2015.July.3.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang N., Liang Y., Yang P., Ji F. Propofol suppresses LPS-induced nuclear accumulation of HIF-1α and tumor aggressiveness in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Reports. 2017;37(5):2611–2619. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang N., Liang Y., Yang P., Yang T., Jiang L. Propofol inhibits lung cancer cell viability and induces cell apoptosis by upregulating microRNA-486 expression. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2017;50(1) doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20165794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z., Zhang J., Hong G., Quan J., Zhang L., Yu M. Propofol inhibits growth and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells through regulation of the miR-21/Slug signaling pathway. American Journal of Translational Research. 2016;8(10):4120–4133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H., Lu Y., Pang Y., Li M., Cheng X., Chen J. Propofol enhances the cisplatin-induced apoptosis on cervical cancer cells via EGFR/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017;86:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chehrehasa F., Meedeniya A. C. B., Dwyer P., Abrahamsen G., Mackay-Sim A. EdU, a new thymidine analogue for labelling proliferating cells in the nervous system. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2009;177(1):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S.-W., Zhang Z.-G., Hao Y.-X., et al. HIF-1α induces the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer stem cells through the Snail pathway. Oncotarget . 2017;8(6):9535–9545. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonpavde G., Sternberg C. N. The role of docetaxel based therapy for prostate cancer in the era of targeted medicine: review article. International Journal of Urology. 2010;17(3):228–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xi H.-J., Zhang T.-H., Tao T., et al. Propofol improved neurobehavioral outcome of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion rats by regulating Bcl-2 and Bax expression. Brain Research. 2011;1410:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ergün R., Akdemir G., Şen S., Taşçi A., Ergüngör F. Neuroprotective effects of propofol following global cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosurgical Review. 2002;25(1-2):95–98. doi: 10.1007/s101430100171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathy-Hartert M., Deby-Dupont G., Hans P., Deby C., Lamy M. Protective activity of propofol, Diprivan and intralipid against active oxygen species. Mediators of Inflammation. 1998;7(5):327–333. doi: 10.1080/09629359890848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du Q.-H., Xu Y.-B., Zhang M.-Y., Yun P., He C.-Y. Propofol induces apoptosis and increases gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer cells in vitro by inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activity. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;19(33):5485–5492. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X.-F., Liao J., Xin Z.-Q., Lu W.-Q., Liu A.-L. Relaxin attenuates silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by regulating collagen type I and MMP-2. International Immunopharmacology. 2013;17(3):537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergamini C., Moruzzi N., Volta F., et al. Role of mitochondrial complex I and protective effect of CoQ10 supplementation in propofol induced cytotoxicity. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2016;48(4):413–423. doi: 10.1007/s10863-016-9673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu P., Du F., Chen W., Yao M., Lv K., Liu Y. Tanshinone IIA blocks epithelial-mesenchymal transition through HIF-1α downregulation, reversing hypoxia-induced chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer cell lines. Oncology Reports. 2014;31(6):2561–2568. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kothari A. N., Mi Z., Zapf M., Kuo P. C. Novel clinical therapeutics targeting the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. linical and Translational Medicine. 2014;3, article 35 doi: 10.1186/s40169-014-0035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philip B., Ito K., Moreno-Sánchez R., Ralph S. J. HIF expression and the role of hypoxic microenvironments within primary tumours as protective sites driving cancer stem cell renewal and metastatic progression. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(8):1699–1707. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoshino H., Miyoshi N., Nagai K.-I., et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition with expression of SNAI1-induced chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;390(3):1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheel C., Weinberg R. A. Phenotypic plasticity and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in cancer and normal stem cells? International Journal of Cancer. 2011;129(10):2310–2314. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris A. L. Hypoxia—a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(1):38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown J. M., Wilson W. R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(6):437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minakata K., Takahashi F., Nara T., et al. Hypoxia induces gefitinib resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer with both mutant and wild-type epidermal growth factor receptors. Cancer Science. 2012;103(11):1946–1954. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murakami A., Takahashi F., Nurwidya F., et al. Hypoxia increases gefitinib-resistant lung cancer stem cells through the activation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086459.e86459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]