Abstract

This study uses the Drugs@FDA database to analyze clinical development times for drugs to treat serious diseases within the 4 FDA expedited programs intended to speed drug review and approval.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has 4 expedited programs to speed the development and review of drugs treating serious diseases: (1) priority review leads to FDA review in 6 months (vs 10 months for standard review); (2) accelerated approval permits approval based on surrogate measures; and (3) fast-track and (4) breakthrough therapy programs are intended to reduce the duration of clinical trials (Table). Clinical development times for drugs in these expedited programs, particularly the newly created breakthrough program (enacted in 2012), have not been comprehensively assessed. We analyzed clinical development times within each of the 4 expedited programs separately and between drugs qualifying for any vs no expedited program. Because fast-track and breakthrough programs are intended to abbreviate the overall drug development process, we also examined development times for drugs receiving either or both of these 2 programs (regardless of other programs).

Table. Characteristics of the FDA’s Expedited Programs for Drugs Treating Serious Diseasesa.

| Characteristics | Accelerated Approval Program | Priority Review Programb | Fast-Track Program | Breakthrough Therapy Program |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year issued or enacted | 1992c | 1992d | 1997e | 2012 |

| Approval based on effect on a surrogate measure or intermediate end point reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit | ✓ | |||

| Shorter FDA review time | ✓ | |||

| Rolling review of application | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Actions to expedite development process | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Organizational commitment and intensive guidance on efficient drug developmentf | ✓ |

Abbreviation: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

Drugs may qualify for more than 1 expedited program.

Priority review aims to provide FDA decision within 6 mo vs 10 mo for standard review.

The FDA’s subpart H (21 CFR §314.500-§314.560; drugs) and subpart E (21 CFR §601.40-§601.46; biologics) regulations were issued in 1992.

From 1975 through 1992, the FDA prioritized drug review using a 3-tiered system: type A, type B, and type C.

The FDA’s subpart E regulations (21 CFR §312.80-§312.88) were issued in 1988; Congress codified fast-track in 1997.

The 1988 subpart E regulations also provided for early consultation and the involvement of senior FDA officials.

Methods

We identified all new FDA-approved drugs and biologics from January 2012 through December 2016 using the Drugs@FDA database and extracted the date of approval and expedited program(s) (priority review, accelerated approval, fast-track, or breakthrough).

Clinical development times were calculated as the time elapsed from the Investigational New Drug (IND) application (when human testing begins) to first FDA approval. IND application dates were obtained from FDA documents, administrative correspondence, and patent extension notices. Dates could not be located for 2 products. The Mann-Whitney test compared median development times between drugs not in any expedited program vs those in at least 1 (a drug can qualify for all 4). We compared development times for priority review or accelerated approval (but not fast-track or breakthrough) drugs vs no expedited program. We also compared, regardless of other programs, (1) drugs with vs without fast-track status; (2) drugs with vs without breakthrough status; (3) fast-track, nonbreakthrough drugs vs breakthrough, non–fast-track drugs; and (4) breakthrough, fast-track drugs vs breakthrough, non–fast-track drugs. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp), version 12. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 174 new drug approvals, 105 (60%) were in 1 or more expedited programs. The expedited programs for 90 drugs included priority review (52%); accelerated approval for 26 drugs (15%); fast-track for 63 drugs (36%); and breakthrough for 29 drugs (17%).

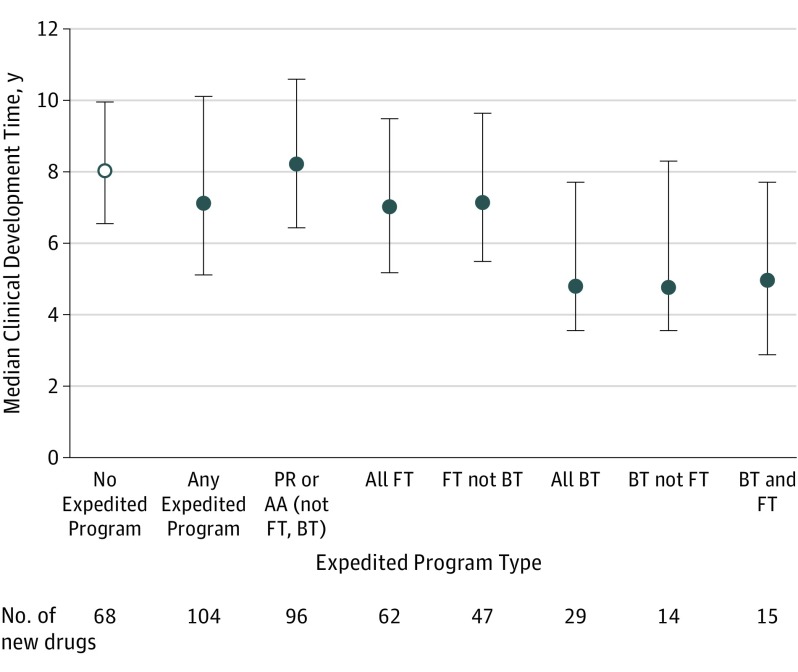

The median development time for drugs in at least 1 expedited program was 7.1 years (interquartile range [IQR], 5.1-10.1) compared with 8.0 years for nonexpedited drugs (IQR, 6.5-10.0; P = .04) (Figure). For nonbreakthrough, non–fast-track drugs, development times were not significantly different between drugs with priority review or accelerated approval vs no expedited program (8.2 years [IQR, 6.4-10.6] vs 8.0 years [IQR, 6.5-10.0]; P = .35).

Figure. Median Clinical Development Times for New Drugs Approved by the FDA, 2012-2016.

AA indicates accelerated approval; BT, breakthrough therapy; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; FT, fast-track; PR, priority review. Clinical development times were calculated from the date of the Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the date of FDA approval. Any expedited program means any of PR, AA, FT, or BT. Development times were not available for 2 drugs in the study cohort. Error bars indicate interquartile ranges.

Development times were shorter for fast-track vs non–fast-track drugs (7.0 years [IQR, 5.2-9.5] vs 8.0 years [IQR, 6.2-10.3]; P = .03) and for breakthrough vs nonbreakthrough drugs (4.8 years [IQR, 3.6-7.7] vs 8.0 years [IQR, 6.2-10.3]; P < .001), regardless of other programs. Breakthrough, non–fast-track drugs had shorter development times than fast-track, nonbreakthrough drugs (4.8 years [IQR, 3.6-8.3] vs 7.1 years [IQR, 5.5-9.6]; P = .001). Development times were similar for breakthrough, fast-track drugs vs breakthrough, non–fast-track drugs (5.0 years [IQR, 2.9-7.7] vs 4.8 years [IQR, 3.6-8.3]; P = .93).

Discussion

The median time from IND application to FDA approval was 0.9 years shorter for drugs with vs without any expedited program. Although priority review provides 4-month shorter FDA review, drugs with priority review (or accelerated approval) were not associated with faster overall development times. The shortest median development time of 4.8 years (32% shorter than fast-track drugs) was observed for drugs with breakthrough status, which provides qualifying manufacturers with all of the benefits of the fast-track designation plus even more intensive guidance on efficient drug development. Study limitations are that only approved agents were analyzed, and potential bias may exist in which drugs are selected for expedited programs.

Through December 2016, 165 investigational drugs received breakthrough status, and the frequency of breakthrough therapy approvals has increased. Despite the association of breakthrough status with heightened expectations of benefit by physicians and patients, expedited drug approvals have also been associated with greater postmarket safety risks. Although this program provides greater speed, regulators should ensure clear communication about the limitations of the collected evidence and the additional risks that these drugs may impose on patients.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration Guidance for industry: expedited programs for serious conditions—drugs and biologics. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm358301.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration Novel drug approvals for 2016. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/druginnovation/ucm483775.htm. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 3.Downing NS, Shah ND, Aminawung JA, et al. . Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1854-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kesselheim AS, Woloshin S, Eddings W, Franklin JM, Ross KM, Schwartz LM. Physicians’ knowledge about FDA approval standards and perceptions of the “breakthrough therapy” designation. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1516-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnamurti T, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Fischhoff B. A randomized trial testing US Food and Drug Administration “breakthrough” language. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1856-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]