Abstract

Colorectal cancers comprise a complex mixture of malignant cells, non-transformed cells, and microorganisms. Fusobacterium nucleatum is among the most prevalent bacterial species in colorectal cancer tissues. Here we show that colonization of human colorectal cancers with Fusobacterium and its associated microbiome, —including Bacteroides, Selenomonas, and Prevotella species, —is maintained in distal metastases, demonstrating microbiome stability between paired primary and -metastatic tumors. In situ hybridization analysis revealed that Fusobacterium is predominantly associated with cancer cells in the metastatic lesions. Mouse xenografts of human primary colorectal adenocarcinomas were found to retain viable Fusobacterium and its associated microbiome through successive passages. Treatment of mice bearing a colon cancer xenograft with the antibiotic metronidazole reduced Fusobacterium load, cancer cell proliferation, and overall tumor growth. These observations argue for further investigation of antimicrobial interventions as a potential treatment for patients with Fusobacterium-associated colorectal cancer.

The cancer-associated microbiota is known to influence cancer development and progression, most notably for colorectal cancer (1–5). Unbiased genomic analyses have revealed an enrichment of Fusobacterium nucleatum in human colon cancers and adenomas relative to non-cancerous colon tissues (6, 7). These observations have been confirmed in studies of multiple colon cancer patient cohorts from around the world (8–12). Increased tumor levels of F. nucleatum have been correlated with lower T-cell infiltration (13); with advanced disease stage and poorer patient survival (10, 11, 14); and with clinical and molecular characteristics such as right-sided anatomic location, BRAF mutation, and hypermutation with microsatellite instability (9, 12, 15).

Studies in diverse experimental models have suggested a pro-tumorigenic role for Fusobacterium. Feeding mice with Fusobacterium (16–18), infection of colorectal cancer cell lines with Fusobacterium (19–21), and generation of xenografts derived from Fusobacterium-infected colorectal cancer cell lines (17) were all observed to potentiate tumor cell growth. Suggested mechanisms have ranged from enhanced tumor cell adhesion and invasion (17, 19, 22), to modulation of the host immune response (16, 23), to activation of the Toll-like receptor 4 pathway (17, 20, 21). However, not all animal or cellular studies of Fusobacterium have demonstrated a cancer-promoting effect (24). A recent editorial has highlighted the importance of studying Fusobacterium infection in colon cancer as a component of the diverse microbiota within the native tumor microenvironment (25).

To investigate the role of Fusobacterium and its associated microbiota in native human colorectal cancers, we analyzed five independent cohorts of patient-derived colorectal cancers for Fusobacterium and microbiome RNA and/or DNA. Where technically possible, we performed Fusobacterium culture and tested the effect of antibiotic treatment upon the growth of propagated patient-derived colon cancer xenografts. These cohorts (table S1) include: (i) 11 fresh-frozen primary colorectal cancers and paired liver metastases (frozen paired cohort); (ii) 77 fresh-frozen primary colorectal cancers with detailed recurrence information (frozen primary cohort); (iii) published data from 430 resected fresh-frozen colon carcinomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas (26) (TCGA cohort), together with data from 201 resected fresh-frozen hepatocellular carcinomas from TCGA (27); (iv) 101 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded colorectal carcinomas and paired liver metastases (FFPE paired cohort); and (v) 13 fresh primary colorectal cancers used for patient-derived xenograft studies (xenograft cohort).

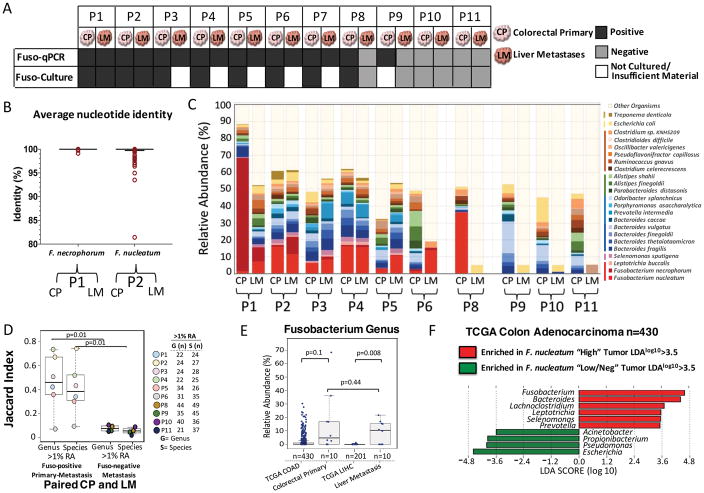

Using the frozen paired cohort, we tested whether we could culture viable Fusobacterium from primary colorectal carcinomas and corresponding liver metastases. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) studies showed that 9 of 11 (82%) snap-frozen primary tumors (table S2) were positive for Fusobacterium in the primary tumor [patients one through nine (P1 through P9)]; we could isolate Fusobacterium from 73% of these tumors (n = 8 of 11 tumors; P1 through P8) (Fig. 1A). In addition, we cultured Fusobacterium from two liver metastases (P1 and P2) from Fusobacterium-positive primary tumors. Five metastatic specimens had inadequate amounts of tissue for culture but were positive for Fusobacterium by qPCR (P3 through P7), for a total of seven primary-metastatic tumor pairs (64%) testing positive for Fusobacterium by qPCR (Fig. 1A). This finding extends previous results showing the presence of Fusobacterium nucleic acids in hepatic and lymph node metastases of colon cancer (7, 22, 28) to now demonstrate that viable Fusobacterium are present in distant metastases.

Fig. 1. Fusobacterium colonizes liver metastases of Fusobacterium associated colorectal primary tumors.

(A) Schematic of Fusobacterium culture and Fusobacterium-targeted qPCR status of paired snap-frozen colorectal primary tumors and liver metastases from 11 patients (P1 to P11) from the frozen paired cohort. (B) Aligned dot plot representing the average nucleotide identity (ANI) of whole-genome sequencing data from F. necrophorum isolated from paired primary colorectal tumor (CP) and liver metastasis (LM) of P1 and F. nucleatum isolate cultured from paired primary tumors and liver metastasis of P2. F. necrophorum P1 two-way ANI: 100% (SD: 0.01%) from 10,220 fragments; F. nucleatum P2 two-way ANI: 99.99% (SD: 0.23%) from 7334 fragments. (C) Species-level microbial composition of paired colorectal primary tumors and liver metastases (frozen paired cohort), assayed by RNA sequencing followed by PathSeq analysis for microbial identification. For simplicity, only organisms with >2% relative abundance (RA) in at least one tumor are shown. The colors correspond to bacterial taxonomic class. Red, Fusobacteriia; pink, Negativicutes; blue/green, Bacteroidia; orange, Clostridia; yellow, Gamma-proteobacteria; dark brown, Spirochaetes. The samples are separated into three groups: Fusobacterium-positive primary tumor and metastases (n = 6 pairs), Fusobacterium-positive primary tumor and Fusobacterium-negative metastases (n = 1 pair), and Fusobacterium-negative primary tumor and metastases (n = 3 pairs). P7 had insufficient tissue for RNA sequencing analysis. (D) Box plots represent the Jaccard index (proportion of shared genera or species) between paired colorectal primary tumors and liver metastases at both the genus and species level at 1% RA. The box represents the first and third quartiles, and error bars indicate the 95% confidence level of the median. Paired samples that were positive for Fusobacterium in both the primary tumor and metastasis were compared with paired samples where the metastasis was Fusobacterium-negative. P values were determined using Welch’s two-sample t test. (E) Box plots of Fusobacterium RA in primary colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) (n = 430) and primary liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) (n = 201) from TCGA (TCGA cohort) and primary-metastasis pairs from 10 patients. The box represents the first and third quartiles, and error bars indicate the 95% confidence level of the median. P values were determined using Welch’s two-sample t test with correction for unequal variances. (F) Identification of bacteria that co-occur with Fusobacterium in primary COAD (TCGA cohort). Primary COAD tumors were subset into two groups: Fusobacterium “High” if Fusobacterium RA was >1% (n = 110, median RA = 5%, mean RA = 7.4%) and Fusobacterium “Low/Neg” if RA was <1% (n = 320, median RA = 0.06%, mean RA = 0.16%). The bar plot illustrates genera enriched (red) and depleted (green) in COAD with >1% Fusobacterium RA. LDA, linear discriminant analysis.

To address whether the same Fusobacterium is present in primary cancers and metastases, we performed whole-genome sequencing of pure Fusobacterium isolates from primary and metastatic tumors from two patients (P1 and P2). For both patients, the primary-metastatic tumor pairs harbored highly similar strains of Fusobacterium, with >99.9% average nucleotide identity, despite the tissue being collected months (P2) or even years (P1) apart (Fig. 1B and fig. S1). We cultured Fusobacterium. necrophorum subsp. funduliforme from the primary colorectal tumor and liver metastasis of P1 and F. nucleatum subsp. animalis from the primary tumor and metastasis of P2. We also cultured other anaerobes, including Bacteroides species, from the primary-metastasis pairs (table S3). Our finding of nearly identical, viable Fusobacterium strains in matched primary and metastatic colorectal cancers confirms the persistence of viable Fusobacterium through the metastatic process and suggests that Fusobacterium may migrate with the colorectal cancer cells to the metastatic site.

To quantitate the relative abundance (RA) of Fusobacterium and to evaluate the overall microbiome in the paired primary and metastatic tumors, we performed RNA sequencing of 10 primary cancers and their matched liver metastases from the frozen paired cohort (P1 to P6 and P8 to -P11). PathSeq analysis (29) of the RNA sequencing data showed that the same Fusobacterium species were present, at a similar relative abundance, in the paired primary-metastatic tumors (Fig. 1C, samples P1 to P6) and that the overall dominant microbiome was also qualitatively similar. In addition to F. nucleatum and F. necrophorum, primary cancer microbes that persisted in the liver metastases included Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, and several typically oral anaerobes such as Prevotella intermedia and Selenomonas sputigena (Fig. 1C). In contrast, there was little similarity between bacterial sequences in the primary colorectal cancer and liver metastasis in the lone sample where Fusobacterium was present in the primary cancer but not detected in the metastasis (Fig. 1C, sample P8) or in the three samples with low or undetectable levels of Fusobacterium in the primary cancer (Fig. 1C, samples P9 to -P11). Jaccard index analysis revealed a high correlation between the dominant bacterial genera in the primary tumor and metastasis for Fusobacterium-positive pairs, but a low correlation between bacterial genera in the primary tumor and metastasis for Fusobacterium-negative pairs (Fig. 1D and fig. S2).

Targeted bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing on DNA from the 11 frozen paired samples confirmed that (i) Fusobacterium species are present in paired primary-metastatic tumors, (ii) the relative abundance of Fusobacterium is correlated between primary tumors and metastases, and (iii) the dominant microbial genera in the liver metastases correspond to those in the primary tumors, demonstrating microbiome stability between paired Fusobacterium-positive primary-metastatic tumors (P= 0.01), (fig. S3).

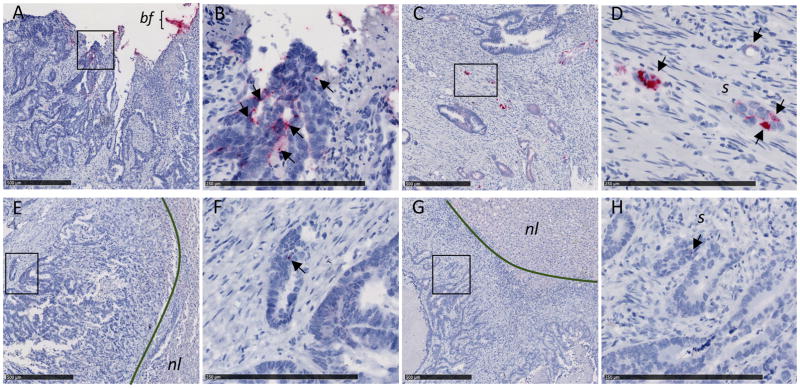

To investigate the relationship between Fusobacterium and cancer recurrence, we performed microbial culture and bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequencing in a blinded fashion on the “frozen primary cohort” of 77 snap-frozen colorectal cancers lacking paired metastases (n = 21 with recurrence, n = 56 without recurrence) (table S4), discovered that 44 of 77 tumors (57%) had cultivable Fusobacterium species and 45 of 77 had >1% Fusobacterium relative abundance. We found no correlation between Fusobacterium load or culture with either recurrence or stable disease, in this cohort (fig. S4). To assess Fusobacterium persistence and its correlation with clinical parameters, we analyzed the 101 primary-metastasis pairs from the FFPE paired cohort (table S5). We found that 43% (n = 44 of 101) of primary colorectal cancers tested positive for Fusobacterium by qPCR and 45% (n = 20 of 44) of liver metastases arising from these primary tumors were Fusobacterium-positive (fig. S5A). To determine the spatial distribution of Fusobacterium in these tumors, Fusobacterium RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) analysis was performed on five qPCR-positive primary-metastasis pairs from this cohort (table S6, Fig. 2, and fig. S6). Both biofilm and invasive F. nucleatum were observed in primary colorectal cancer (Fig. 2, A to D). Invasive F. nucleatum distribution was highly heterogeneous and focal, found in isolated or small groups of cells with morphology consistent with that of malignant cells, and located close to the lumen and ulcerated regions. F. nucleatum was also observed in glandular structures present in the tumor center and invasive margins, but to a lesser extent. In adjacent normal mucosa (when present), F. nucleatum was exclusively located in the biofilm. In liver metastasis, F. nucleatum was predominantly localized in isolated cells whose histomorphology is consistent with colon cancer cells (Fig. 2, E to H), although occasional stromal F. nucleatum could be observed as well. No F. nucleatum was detected in the adjacent residual liver parenchyma.

Fig. 2. F. nucleatum RNA ISH analysis of matched primary colorectal tumors and liver metastases.

Representative images of F. nucleatum spatial distribution in paired samples from P187 primary colorectal tumor (A and B) and liver metastasis (E and F) and P188 primary colorectal tumor (C and D) and liver metastasis (G and H) from the FFPE paired cohort are shown. Arrows indicate cells with histomorphology consistent with that of colon cancer cells infected by invasive F. nucleatum (red dots) in both primary colorectal tumors (B and D) and matched liver metastases (F and H). Fusobacterium-containing biofilm (bf) is highlighted in the colorectal tumor of P187 (A). Fusobacterium was not detected in normal liver (nl) tissue [(E) and (F)]. s, stroma. Panels (B), (D), (F), and (H) show magnification of the boxed areas in (A), (C), (E), and (G), respectively. Scale bars: 500 mm in (A), (C), (E), and (G); 250 mm in (B), (D), (F), and (H).

Notably, none of the 57 Fusobacterium-negative primary colorectal tumors were associated with a Fusobacterium-positive liver metastasis (n = 0 of 57; P = 0) (fig. S5A). Consistent with previous reports (15), the presence of Fusobacterium in paired primary tumors and corresponding metastases was enriched in metastatic cancers of the cecum and ascending colon cancers (n = 10 of 20 Fusobacterium-positive primary-metastasis pairs, P = 0.002), (fig. S5B), whereas cancers that were Fusobacterium-negative in both primary and metastatic lesions were more likely to be rectal cancers (n = 29 of 57 of the Fusobacterium-negative primary-metastasis pairs, P = 0.016), (fig. S5B). To assess the relationship between patient survival and Fusobacterium presence in the primary cecum and ascending colon, we carried out PathSeq (29) analysis on RNA sequencing data from the 430 primary colon adenocarcinomas in the TCGA cohort. Patients with cancer of the cecum and ascending colon exhibited worse overall survival than patients with non-cecum ascending colon cancer (P = 0.01) (fig. S5C). Among patients with cecum and ascending colon tumors, we observed poorer overall survival in correlation with tumor Fusobacterium load (fig. S5D), (P = 0.004).

To determine whether Fusobacterium is associated with primary liver hepatocellular carcinoma, we performed PathSeq analysis (29) of RNA sequencing data from 201 primary liver tumors from the TCGA cohort. This analysis demonstrated that Fusobacterium is rare in primary liver carcinomas and that the relative abundance of Fusobacterium is significantly enriched in liver metastases arising from colorectal cancers compared with primary liver cancers (P = 0.008) (Fig. 1E). PathSeq analysis of data from the TCGA cohort also confirmed that the microbes present in liver metastases of Fusobacterium-positive colorectal carcinomas are similar to those associated with Fusobacterium in primary colorectal carcinoma. Selenomonas, Bacteroides, and Prevotella genera were shared between primary and metastatic colorectal cancers and also correlated with Fusobacterium abundance in primary colon adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1F, fig. S7, and table S7).

Given that metastatic colorectal carcinomas harbored cultivable Fusobacterium, we wondered whether viable Fusobacterium could persist in xenografts from human colorectal cancers, which would provide a valuable model system for evaluating the effects of microbiota modulation on cancer growth. In a double-blinded approach, 13 fresh human primary colorectal tumors from the xenograft cohort were evaluated, by culture or qPCR, for the presence of Fusobacterium. In parallel, these tumors were implanted subcutaneously, by an independent investigator, into Nu/Nu mice to establish patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) (table S8). All five Fusobacterium–culture positive tumors resulted in successful xenografts (fig. S8), one of four qPCR-positive but culture-negative tumors gave rise to a successful xenograft, and none of the four Fusobacterium-negative tumors generated successful xenografts (P = 0.003). Tumor grade did not appear to significantly influence successful xenograft formation (P = 0.1) (fig. S9A), although we noted a modest association between Fusobacterium-cultivability and high-grade tumors in this cohort (n = 4 of 5 tumors, P = 0.03) (fig. S9B).

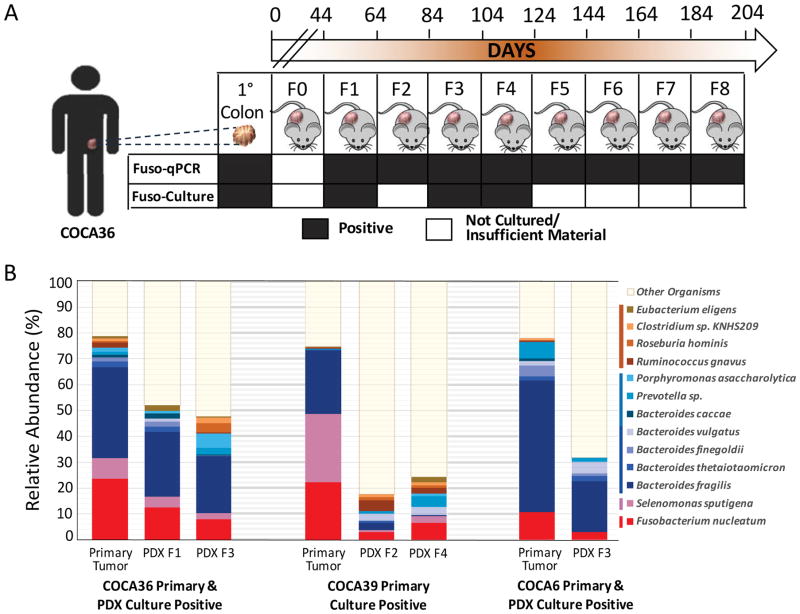

Next, we sought to determine whether Fusobacterium would remain viable and stably associated with a xenograft. A PDX derived from an F. nucleatum culture–positive colon cancer (COCA36) was passaged to F8, over 29 weeks, and tested for F. nucleatum. We cultured F. nucleatum from this PDX for up to four generations and 124 days in vivo. All xenograft generations, from F1 through F8, were positive for Fusobacterium by qPCR (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we cultured other anaerobic bacteria, including B. fragilis and B. thetaiotaomicron, from both the primary tumor and PDXs. We further cultured Fusobacterium from PDXs generated from two additional patient tumors (table S9). qPCR and microbiome analysis of fecal pellets and oral swabs from the PDX-bearing animals were negative for Fusobacterium species (fig. S10), arguing against the possibility of Fusobacterium arising from the endogenous murine microbiota.

Fig. 3. Fusobacterium and co-occurring anaerobes persist in colon adenocarcinoma PDXs.

(A) Assessment of Fusobacterium persistence in PDX COCA36 over a period of 204 days. Fusobacterium persistence was determined via microbial culture and Fusobacterium-targeted qPCR. F0 denotes the first implantation of the tumor into mice; F1 to F8 represent sequential xenograft passages after F0. (B) Species-level microbial composition of three patient primary colon adenocarcinomas (COCA36, COCA39, and COCA6) and subsequent PDXs. Total RNA sequencing was carried out, followed by PathSeq analysis for microbial identification. For simplicity, selected species with >1% relative abundance in the primary tumor and either corresponding PDX are shown. The colors correspond to bacterial taxonomic class. Red, Fusobacteriia; pink, Negativicutes; blue/green, Bacteroidia; orange, Clostridia.

To evaluate the overall microbiome stability and to identify bacteria that are persistently associated with the primary colorectal tumor and derived xenografts, we carried out unbiased total RNA sequencing followed by PathSeq analysis, which revealed that F. nucleatum and other Gram-negative anaerobes, including B. fragilis and S. sputigena, persist in these PDX models for multiple generations (Fig. 3B). The bacteria that persist within the PDX include the genera that we report to persist in distant-site metastases to the liver (Fig. 1C) and that are enriched in Fusobacterium-associated colorectal cancer from analysis of TCGA data (Fig. 1F). Bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequencing further confirmed the persistence of Fusobacterium and co-occurring anaerobes in these primary colorectal tumors and derived xenografts (fig. S11).

Transmission electron microscopy showed that F. nucleatum isolates from both the primary colon carcinoma and PDX were invasive when incubated with human colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and HCT-116. Upon infection with F. nucleatum, we saw evidence of bacterial cells within vesicle-like structures in the cancer cell (fig. S12, A to C). We also observed evidence of bacterial adhesion and invasion in the respective patient xenograft tissue (fig. S12D).

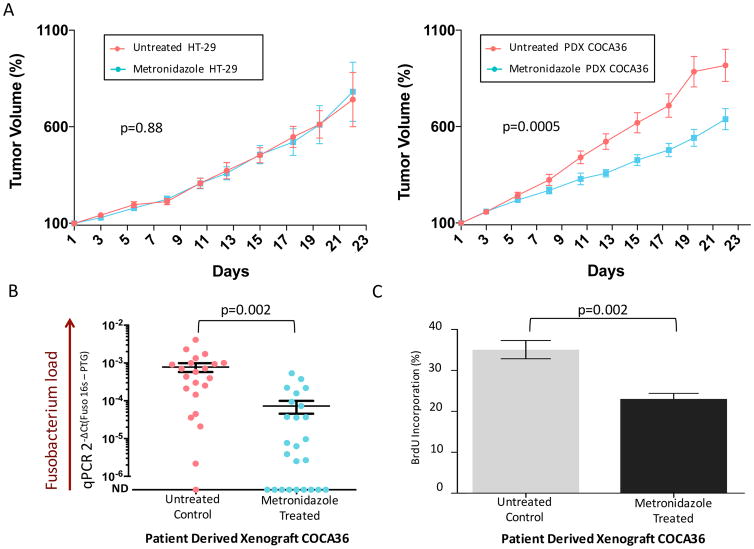

Finally, we asked whether treatment of Fusobacterium-positive colon cancer xenografts with either (i) an antibiotic to which Fusobacterium is resistant or (ii) an antibiotic to which Fusobacterium is sensitive would affect tumor growth. We chose erythromycin as a resistant antibiotic because the F. nucleatum clinical isolates were resistant to high concentrations of erythromycin (minimum inhibitory concentration >25 μg/ml) (fig. S13A). After oral gavage of the Fusobacterium-harboring PDX COCA36, with erythromycin, we observed a slight decrease in tumor volume compared with mice treated with the vehicle control. However, erythromycin did not significantly affect the trajectory of tumor growth (P = 0.073) (fig. S13B), Fusobacterium tumor load (P = 0.98) (fig. S13C), or tumor cell proliferation (P = 0.3) (fig. S13D).

For a Fusobacterium-killing antibiotic, we chose metronidazole because fusobacteria are known to be highly sensitive to this drug (30). We then confirmed sensitivity of the F. nucleatum isolate from PDX COCA36 (minimum inhibitory concentration < 0.01 μg/ml) (fig. S14). Because PDXs could not be generated from Fusobacterium-negative primary tumors, we treated Fusobacterium-free xenografts derived from HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cells with metronidazole to assess whether metronidazole inhibits the growth of Fusobacterium-negative colorectal carcinomas. This experiment revealed no significant change in tumor growth (P = 0.88) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Treatment of Fusobacterium-colonized PDXs with metronidazole reduces tumor growth in vivo.

(A) (Left) Tumor volume percentage of Fusobacterium-free xenografts derived from HT-29 cells treated with metronidazole (treated; 19 animals) or with vehicle (untreated; 20 animals). (Right) Tumor volume percentage of Fusobacterium-positive PDX tumors (COCA36) treated with metronidazole (treated; 25 animals) or with vehicle (untreated; 22 animals). P values were determined by the Wald test. Tumors were measured in a blinded fashion on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays each week. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. The remaining number of HT-29-derived xenografts and PDX-implanted animals at each time point is included in the supplementary materials. (B) Assessment of Fusobacterium tissue load. Fusobacterium-targeted qPCR on PDX tissue (COCA36) after treatment with metronidazole (treated) or with vehicle (untreated). ND, not detected. The center bar represents the mean; error bars indicate SEM. P values were determined using Welch’s two-sample t test. DCt, delta cycle threshold; PTG, prostaglandin transporter. (C) Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) immunohistochemistry of PDX tumors to assess cell proliferation. The bar plot represents the percentage of cells with BrdU incorporation in treated and untreated PDXs (n = 6 animals). per arm); error bars denote mean ± SEM. P values were determined using the Welch’s two-sample t test.

Finally, oral administration of metronidazole to mice bearing Fusobacterium-positive PDXs resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the trajectory of tumor growth, compared with PDXs in mice treated with vehicle (P = 0.0005) (Fig. 4A). Treatment with metronidazole was associated with a significant decrease in Fusobacterium load in the tumor tissue (P = 0.002) (Fig. 4B), as well as a significant reduction in tumor cell proliferation (P = 0.002) (Fig. 4C and fig. S15).

We have shown that (i) Fusobacterium is persistently associated with distant metastases from primary human colorectal cancers; (ii) invasive Fusobacterium can be detected in liver metastases by ISH; (iii) Fusobacterium co-occurs with other Gram-negative anaerobes in primary and matched metastatic tumors; (iv) Fusobacterium survives in colorectal cancer PDXs through multiple generations; and (v) treatment of a Fusobacterium-harboring PDX model with the antibiotic metronidazole decreases Fusobacterium load, cancer cell proliferation, and tumor growth. The persistence of Fusobacterium and its associated microbiome in both metastasis and PDXs, as well as the ability of antibiotic treatment to reduce PDX growth, point to the potential of Fusobacterium, and its associated microbiota, to contribute to colorectal cancer growth and metastasis. On the basis of our observation that the dominant microbiome is highly similar in primary-metastatic pairs and the concordance of Fusobacterium strains found in primary tumors and paired metastases, we hypothesize that Fusobacterium travels with the primary tumor cells to distant sites, as part of metastatic tissue colonization. This suggests that the tumor microbiota are intrinsic and essential components of the cancer microenvironment.

Our results highlight the need for further studies on microbiota modulation as a potential treatment for Fusobacterium-associated colorectal carcinomas. One concern is the negative effect of broad spectrum antibiotics on the healthy intestinal microbiota. Given that metronidazole targets a range of anaerobic bacteria, including co-occurring anaerobes that persist with Fusobacterium, one would ideally want to develop a Fusobacterium-specific antimicrobial agent to assess the effect of selective targeting of Fusobacterium on tumor growth. Important questions raised by our findings are whether conventional chemotherapeutic regimens for colorectal cancer will affect the colon cancer microbiota and whether the microbiota will modulate the response to such therapies. A recent study, reporting that colorectal tumors with a high Fusobacterium load are more likely to develop recurrence (21), supports the concept that Fusobacterium-positive tumors may benefit from anti-fusobacterial therapy. Our results provide a strong foundation for pursuing targeted approaches for colorectal cancer treatment directed against Fusobacterium and other key constituents of the cancer microbiota.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants (R35 CA197568 to M.M., R35 CA197735 to S.O., K07 CA148894 to K.N., and R01 CA118553 and R01 CA169141 to C.S.F.) and Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center GI SPORE P50 grant CA 127003 to C.S.F. (this grant also supports S.B., A.J.A., W.C.H., K.N., and S.O.). In addition, M.M. is supported by an American Cancer Society Research Professorship; W.C.H. is supported by the Hale Family Center for Pancreatic Cancer; C.S.F. is supported by the Project P Fund for Colorectal Cancer Research, Stand-up-to-Cancer (Colorectal Cancer Dream Team), the Chambers Family Fund for Colorectal Cancer Research, the Team Perry Fund, and the Clark Family Fund for GI Cancer Research; S.B. is supported by a Prevent Cancer Foundation Figdor Family Fellowship; G.S., N.M., E.E., P.N., and J.T. are supported by the Cellex Private Foundation; and P.N. is supported by the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Foundation. M.M. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of and holds stock in OrigiMed, a biotechnology company that provides sequencing information for cancer diagnostics. C.S.F. is on the Board of CytomX Therapeutics, a biotechnology company that is developing therapeutic antibodies for cancer, and is a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Genentech, Merck, Sanofi, Five Prime Therapeutics, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Agios Pharmaceuticals, Taiho Oncology, and KEW Group. M.M. and S.B. are inventors on U.S. Provisional Patent Application no. 62/534,672, submitted by the Broad Institute and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, that covers targeting of Fusobacterium for treatment of colorectal cancer. All raw sequencing data from this study can be accessed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the bioproject PRJNA362951. Bacterial whole-genome sequences have been deposited at DNA Data Bank of Japan/European Nucleotide Archive/GenBank, with the following NCBI accession, GenBank assembly accession, and BioSample numbers, respectively: F. necrophorum subsp. funduliforme P1_CP patient P1 primary colorectal tumor (NPNF00000000, GCA_002761995.1, and SAMN07448029), F. necrophorum subsp. funduliforme P1_LM patient P1 liver metastasis (NPNE00000000, GCA_002762025.1, and SAMN07448030), F. nucleatum subsp. animalis P2_CP patient P2 primary colorectal tumor (NPND00000000, GCA_002762005.1, and SAMN07448031), and F. nucleatum subsp. animalis P2_LM patient P2 liver metastasis (NPNC00000000, GCA_002762015.1, and SAMN07448032).

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Mühlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, Abujamel T, Dogan B, Rogers AB, Rhodes JM, Stintzi A, Simpson KW, Hansen JJ, Keku TO, Fodor AA, Jobin C. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hope ME, Hold GL, Kain R, El-Omar EM. Sporadic colorectal cancer – role of the commensal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;244:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowland IR. The role of the gastrointestinal microbiota in colorectal cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:1524–1527. doi: 10.2174/138161209788168191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S, Rhee KJ, Albesiano E, Rabizadeh S, Wu X, Yen HR, Huso DL, Brancati FL, Wick E, McAllister F, Housseau F, Pardoll DM, Sears CL. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat Med. 2009;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, Pei Z. Bacteria, inflammation, and colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6741–6746. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J, Barnes R, Watson P, Allen-Vercoe E, Moore RA, Holt RA. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:299–306. doi: 10.1101/gr.126516.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Ojesina AI, Jung J, Bass AJ, Tabernero J, Baselga J, Liu C, Shivdasani RA, Ogino S, Birren BW, Huttenhower C, Garrett WS, Meyerson M. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCoy AN, Araújo-Pérez F, Azcárate-Peril A, Yeh JJ, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Fusobacterium is associated with colorectal adenomas. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e53653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahara T, Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Maruyama R, Chung W, Garriga J, Jelinek J, Yamano HO, Sugai T, An B, Shureiqi I, Toyota M, Kondo Y, Estécio MRH, Issa J-PJ. Fusobacterium in colonic flora and molecular features of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1311–1318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan L, Schmid J, Ebert M, Soucek P, Kunicka T, Liska V, Bruha J, Neary P, Dezeeuw N, Tommasino M, Jenab M, Prehn JHM, Hughes DJ. Fusobacterium nucleatum associates with stages of colorectal neoplasia development, colorectal cancer and disease outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1381–1390. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito M, Kanno S, Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, Igarashi H, Takahashi T, Tachibana M, Takahashi H, Yoshii S, Takenouchi T, Hasegawa T, Okita K, Hirata K, Maruyama R, Suzuki H, Imai K, Yamamoto H, Shinomura Y. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1258–1268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li YY, Ge Q-X, Cao J, Zhou Y-J, Du Y-L, Shen B, Wan Y-JY, Nie Y-Q. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum infection with colorectal cancer in Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3227–3233. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Yamauchi M, Inamura K, Kim SA, Masuda A, Nowak JA, Nosho K, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Watanabe H, Bullman S, Milner DA, Harris CC, Giovannucci E, Garraway LA, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Chan AT, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T cells in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:653–661. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Bullman S, Milner DA, Baba H, Giovannucci EL, Garraway LA, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Meyerson M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut. 2016;65:1973–1980. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mima K, Cao Y, Chan AT, Qian ZR, Nowak JA, Masugi Y, Shi Y, Song M, da Silva A, Gu M, Li W, Hamada T, Kosumi K, Hanyuda A, Liu L, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Bullman S, Brennan CA, Milner DA, Baba H, Garraway LA, Meyerhardt JA, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Meyerson M, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Nishihara R, Ogino S. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue according to tumor location. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e200. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL, El-Omar EM, Brenner D, Fuchs CS, Meyerson M, Garrett WS. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Weng W, Peng J, Hong L, Yang L, Toiyama Y, Gao R, Liu M, Yin M, Pan C, Li H, Guo B, Zhu Q, Wei Q, Moyer M-P, Wang P, Cai S, Goel A, Qin H, Ma Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating Toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor-κB, and up-regulating expression of microRNA-21. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:851–866.e24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu YN, Yu T-C, Zhao H-J, Sun T-T, Chen H-M, Chen H-Y, An H-F, Weng Y-R, Yu J, Li M, Qin W-X, Ma X, Shen N, Hong J, Fang J-Y. Berberine may rescue Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced colorectal tumorigenesis by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32013–32026. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinstein MR, Wang X, Liu W, Hao Y, Cai G, Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Peng Y, Yu J, Chen T, Wu Y, Shi L, Li Q, Wu J, Fu X. Invasive Fusobacterium nucleatum activates beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer via a TLR4/P-PAK1 cascade. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31802–31814. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, Sun T, Ma D, Han J, Qian Y, Kryczek I, Sun D, Nagarsheth N, Chen Y, Chen H, Hong J, Zou W, Fang J-Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by modulating autophagy. Cell. 2017;170:548–563.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abed J, Emgård JEM, Zamir G, Faroja M, Almogy G, Grenov A, Sol A, Naor R, Pikarsky E, Atlan KA, Mellul A, Chaushu S, Manson AL, Earl AM, Ou N, Brennan CA, Garrett WS, Bachrach G. Fap2 mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum colorectal adenocarcinoma enrichment by binding to tumor-expressed Gal-GalNAc. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gur C, Ibrahim Y, Isaacson B, Yamin R, Abed J, Gamliel M, Enk J, Bar-On Y, Stanietsky-Kaynan N, Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Shussman N, Almogy G, Cuapio A, Hofer E, Mevorach D, Tabib A, Ortenberg R, Markel G, Miklić K, Jonjic S, Brennan CA, Garrett WS, Bachrach G, Mandelboim O. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015;42:344–355. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomkovich S, Yang Y, Winglee K, Gauthier J, Mühlbauer M, Sun X, Mohamadzadeh M, Liu X, Martin P, Wang GP, Oswald E, Fodor AA, Jobin C. Locoregional effects of microbiota in a preclinical model of colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2620–2632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt RA, Cochrane K. Tumor potentiating mechanisms of Fusobacterium nucleatum, a multifaceted microbe. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:694–696. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:1327–1341.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J, Chen Y, Fu X, Zhou X, Peng Y, Shi L, Chen T, Wu Y. Invasive Fusobacterium nucleatum may play a role in the carcinogenesis of proximal colon cancer through the serrated neoplasia pathway. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1318–1326. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostic AD, Ojesina AI, Pedamallu CS, Jung J, Verhaak RGW, Getz G, Meyerson M. PathSeq: Software to identify or discover microbes by deep sequencing of human tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:393–396. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löfmark S, Edlund C, Nord CE. Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(suppl 1):S16–S23. doi: 10.1086/647939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin FE, Nadkarni MA, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Quantitative microbiological study of human carious dentine by culture and real-time PCR: Association of anaerobes with histopathological changes in chronic pulpitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1698–1704. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1698-1704.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig W. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics and identification. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;120:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. 2014 Jun 23; arXiv:1406.5823 [stat.CO] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen I-MA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: A system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2271–2278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView Server: A comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(suppl 2):W181–W184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.