Abstract

Background

D-dimer, a biomarker of coagulation, is higher in blacks than whites and has been associated with stroke and CHD.

Objectives

To assess the association of higher D-dimer with stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD) in blacks and whites.

Materials/Methods

REGARDS recruited 30,239 black and white participants across the contiguous US and measured baseline D-dimer in stroke (n=646) and CHD (n=654) cases and a cohort random sample (n=1,104). Cox models adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors determined the hazard ratio (HR) for increasing D-dimer for cardiovascular disease with bootstrapping to assess the difference in HR for CHD versus stroke by race.

Results

D-dimer was higher with increasing age, female sex, diabetes, hypertension, pre-baseline cardiovascular disease and higher C-reactive protein (CRP). Accounting for cardiovascular risk factors, each doubling of D-dimer was associated with increased stroke (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.01, 1.31) and CHD (HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.11, 1.45) risk. The difference in the HR between CHD and stroke was 0.20 (95% CI >0.00, 0.58) for blacks and 0.02 (95% CI −0.30, 0.27) for whites. CRP mediated 22% (95% CI 5%, 41%) of the association between D-dimer and CHD and none of the association with stroke.

Discussion

Higher D-dimer increased the risk of stroke and CHD independent of cardiovascular risk factors and CRP, with perhaps a stronger association for CHD versus stroke in blacks than whites. These findings highlight potential different pathophysiology of vascular disease by disease site and race suggesting potential further studies targeting haemostasis in primary prevention of vascular disease.

Keywords: Continental Population Groups, Coronary Disease, D-dimer, Epidemiology Stroke

Introduction

The role haemostasis biomarkers and more specifically D-dimer play in stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD) risk is not established, and the quality of evidence for stroke is less than that available for CHD(1–3). While stroke and CHD share many risk factors, each disease is unique and inflammation and coagulation may play different roles. Fibrin fragment D-dimer is a circulating peptide degradation product of cross-linked fibrin (formed during thrombus formation). In the general population plasma levels reflect systemic fibrin formation, with higher levels reflecting more systemic fibrin formation and a tendency for increased thrombosis(4). Most but not all studies show an association of higher D-dimer with future CHD, with similar but fewer results for stroke(5–9). Further, existing studies include few non-Caucasian participants and do not compare associations of D-dimer across cardiovascular diseases. As African-Americans (blacks) have higher levels of D-dimer and other markers of haemostasis than Caucasian-Americans (whites), differences in haemostasis may potentially explain any black-white differences in cardiovascular disease risk(9–11). Further, as risk factors for stroke and CHD differ, we sought to assess whether haemostasis, as measured by plasma D-dimer levels, is differentially associated with stroke and CHD risk(2).

We used the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study to assess the association of D-dimer with stroke and CHD and stratifying by race (blacks and whites). Further, we evaluated whether inflammation mediates any of the association of D-dimer with cardiovascular disease and whether racial differences in D-dimer cause any of the known racial differences in stroke risk. By understanding potential mechanisms of cardiovascular disease risk in individuals, researchers can design novel preventive strategies targeting domains of risk such as haemostasis, inflammation, or platelet function.

Materials and Methods

Cohort

REGARDS recruited 30,239 individuals from the contiguous United States (US) between 2003–07. By design, the cohort was 55% female, 41% black and 56% lived in the southeast of the U.S. (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana) with recruitment goal being 50% for each stratum. Potential participants were contacted by telephone, and after verbal informed consent, participated in a computer assisted telephone interview gathering basic demographic and risk factor data. Exclusion criteria were medical conditions preventing long-term participation, active cancer or treatment for cancer in the past 12 months, resident in or on the waiting list for a nursing home, inability to communicate in English, or race other than black or white (by participant self-report). Participants then underwent an in-home visit where anthropomorphic data, medication inventory, fasting phlebotomy, and written informed consent were performed (Examination Management Systems Incorporated, Irving, Texas) with detailed methods previously published(12–14). This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

Laboratory

Laboratory methods have been described in detail previously(15). Phlebotomy was performed after a 10–12 hour fast in the morning at the in-home visit. Samples were centrifuged locally and shipped overnight on dry-ice to the study laboratory at the University of Vermont where they were recentrifuged and stored at −80°C. D-dimer was measured in plasma using an immunoturbidometric assay on the STAR analyzer and reported in ug/mL (Diagnostica Stago, Asnières sur Seine, France) with an interassay coefficient of variation of 5–17%. D-dimer was measured in incident stroke cases (n = 646, 269 blacks), incident CHD cases (n=654, 289 blacks), and in a stratified cohort random sample (CRS, n=1,104, 552 blacks). C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured using a high-sensitivity particle enhanced immunonephelometric assay on the BNII nephelometer, (N High Sensitivity CRP, Dade Behring Incorporated, Deerfield, IL) with an interassay CV 2–6%. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglycerides were measured by colorimetric reflectance spectrophotometry using the Ortho Vitros Clinical Chemistry System 950IRC instrument (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY), with low density lipoprotein cholesterol calculated by the Friedewald equation for subjects with triglycerides <400 mg/dl. Lipids and CRP were measured in the entire cohort.

Definitions

Baseline conditions were present at or before the date of the in-home visit. Prevalent stroke and peripheral arterial disease was based on participant self-report and prevalent CHD was based on participant self-report or electrocardiogram evidence of prior myocardial infarction. Prevalent cardiovascular disease was defined as stroke, peripheral arterial disease, or CHD present at enrolment. Atrial fibrillation was defined as participant report of atrial fibrillation or by electrocardiogram done at the in-home exam. Left ventricular hypertrophy was defined using the baseline electrocardiogram. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose ≥126mg/dL, nonfasting glucose ≥200mg/dL, or self-reported use of diabetes medications. Systolic blood pressure was the average of two seated measures after a 5 minute rest. Use of antihypertensive medications and cholesterol lowering medications was defined by participant self-report from a medication inventory.

Outcomes

Participants were followed for incident stroke and CHD events, with detailed methods for stroke(12) and CHD(16) event ascertainment previously published. Participants or proxies were contacted every 6 months by telephone to ascertain stroke or stroke symptoms and potential CHD hospitalizations as well as fatal CHD or stroke events. Medical records, including neuroimaging and other diagnostic reports, as well as death certificates and summaries of last hospitalizations in those who died, were retrieved and centrally reviewed by physicians to confirm endpoints. For stroke, adjudication was based on the World Health Organization’s definition of stroke and/or imaging consistent with stroke. Follow-up for stroke was complete through September 1, 2011. For CHD, adjudication followed published guidelines for major epidemiology studies for nonfatal myocardial infarction and acute CHD death(17). Myocardial infarction diagnoses were based on a rising and/or falling pattern of cardiac biomarkers to a level at least twice the upper limit of normal for the biomarker; clinical signs or symptoms consistent with ischemia; and electrocardiogram findings guided by the Minnesota Code. Acute CHD death was ascertained through interviews with proxies or next of kin about circumstances immediately prior to death, autopsy reports, hospital records, death certificates and medical history obtained at baseline. Follow-up for CHD was complete through December 31, 2009, and only definite or probable events were included in this analysis.

Statistical Analyses

We performed a stratified case-cohort analysis using methods proposed by Prentice with detailed methods in REGARDS previously published(18–21). In the CRS, correlates of D-dimer quintiles were determined accounting for sample weighting; categorical variables were compared using the Rao-Scott χ2 statistic and means of continuous variables using weighted analysis of variance.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) with robust sandwich estimators to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) accounting for sample weighting. Due to skewing, D-dimer was log base 2 transformed and analysed per 1 unit log D-dimer increment when analysed as a continuous variable (which can be interpreted as a doubling of non-transformed D-dimer concentrations). Models for stroke excluded participants with prevalent stroke and models for CHD excluded participants with prevalent CHD at baseline. Three models were fitted each for stroke and CHD, the first adjusting for demographics, the second with additional adjustment for cardiovascular disease risk factors, and the third by adding C-reactive protein (CRP) to the cardiovascular disease risk factor model. For stroke, the basic model was adjusted for age, sex, region, race, and an age by race interaction term which in previous analyses was shown to be significant(12). The second model added adjustment for risk factors in the Framingham Stroke Risk Score including systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, prevalent cardiovascular disease, prevalent atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular hypertrophy(22). For CHD, the basic model was adjusted for age, sex, region and race and the cardiovascular risk factor model added systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and use of cholesterol-lowering medications. The third model added the natural log of CRP to the cardiovascular risk factor model. The difference in the HR for D-dimer between stroke and CHD was calculated by subtracting the two HR and the 95% CI for the difference was calculated by bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. The natural log of CRP was added to the second model to assess how much of the association of D-dimer with cardiovascular events was explained by D-dimer as an inflammation marker. Models were presented for the entire cohort as well as the HR for blacks and whites separately (a pre-specified analysis). Finally, we performed mediation analysis to determine whether D-dimer mediated any of the excess stroke risk in blacks using bootstrapping with 1,000 replicate samples with replacement to determine the 95% CI of the difference between the HR of race with and without D-dimer in the model. Participants with missing covariates were dropped from the analysis and individuals were followed until the date of last follow-up, withdrawal from the study, or death.

Sensitivity analyses were done excluding haemorrhagic strokes and excluding participants with either baseline CHD or baseline stroke from analyses of either endpoint (i.e. CHD cases from the stroke models and stroke cases from the CHD models). All analyses were done using SAS 9.3 (Gary, North Carolina).

Results

During follow-up, there were 654 incidence CHD events (median follow-up 4.4 years, interquartile range 3.1 – 5.5 years) and 646 incident stroke events (median follow-up 5.8 years, interquartile range 4.1 – 7.0). Median D-dimer in the CRS was 0.40ug/mL (IQR 0.23 – 0.76), 0.52ug/mL (IQR 0.31, 0.92) in stroke cases and 0.52 ug/mL (IQR 0.32, 0.92) in CHD cases.

Presented In table 1, higher D-dimer was observed with older age, female sex, higher systolic blood pressure and use of antihypertensive medications, higher HDL cholesterol, higher CRP, and higher prevalence of baseline cardiovascular disease and left ventricular hypertrophy (all p <0.05). The geometric mean D-dimer was higher in blacks (0.49ug/mL) than whites (0.39ug/mL) (p<0.001). There was no association between D-dimer and total cholesterol, current smoking, or atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Association of Baseline Cardiovascular Risk Factors with D-dimer Concentration in REGARDS

| D-dimer Quintiles (ng/mL) | Q5 (≥0.90) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0 – 0.22) | Q2 (0.23 – 0.32) | Q3 (0.33 – 0.51) | Q4 (0.52 – 0.89) | |||

| Cohort Random Sample (N, weighted %) | 177 (19.7%) | 156 (17.9%) | 212 (21.9%) | 231 (20.46%) | 257 (20.0%) | - |

| Age (years, mean, SE) | 59.3 (0.5) | 62.4 (0.6) | 65.7 (0.6) | 67.4 (0.6) | 69.8 (0.61) | <0.001 |

| Sex, Male (n, %) | 105 (48.3%) | 88 (52.3%) | 103 (43.6%) | 115 (46.1%) | 105 (34.0%) | 0.04 |

| Race, Black (n, %) | 73 (32.0%) | 72 (39.5%) | 94 (39.6%) | 123 (44.9%) | 148 (49.1%) | 0.06 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg, mean, SE) | 122 (1) | 125 (1) | 128 (1) | 130 (2) | 129 (1) | <0.01 |

| Using blood pressure medications (n, %) | 69 (44.1%) | 72 (48.8%) | 103 (50.6%) | 134 (55.9%) | 162 (62.5%) | 0.04 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL, mean, SE) | 194 (3.5) | 186 (3) | 188 (3) | 190 (3) | 190 (3) | 0.74 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL, mean, SE) | 51 (1) | 49 (1) | 51 (1.2) | 51 (1.3) | 55 (1.6) | 0.04 |

| Current Smoking (n, %) | 28 (12.3%) | 28 (11.1%) | 32 (14.0%) | 32 (13.3%) | 37 (17.7%) | 0.56 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (n, %) | 26 (14.5%) | 29 (18.1%) | 47 (23.1%) | 56 (25.8%) | 52 (21.8%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (n, %) | 27 (16.3%) | 20 (12.3%) | 26 (11.3%) | 53 (20.9%) | 71 (28.3%) | 0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation (n, %) | 23 (12.5%) | 12 (8.4%) | 19 (8.5%) | 15 (8.6%) | 23 (9.6%) | 0.80 |

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (n, %) | 15 (8.5%) | 9 (6.0%) | 12 (3.6%) | 27 (12.8%) | 34 (9.6%) | 0.01 |

| CRP (mg/dL, geometric mean, SE) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.4) | 3.3 (2.02) | <0.001 |

Higher baseline D-dimer was associated with increased risk of both incident CHD and stroke (Table 2). In the demographic model, each doubling D-dimer was associated with a 32% higher risk of CHD (HR 1.32; 95% CI 1.17, 1.50) and a 20% higher risk of stroke (HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.07, 1.35). The HR of stroke for D-dimer was similar in blacks and whites (HR 1.18 for blacks and 1.22 for whites, p-interaction =0.80), while the HR of CHD was non-significantly higher for blacks than whites (HR 1.41 for blacks and 1.24 for whites, p-interaction =0.30). When adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors, the HRs were slightly attenuated but statistical significance was maintained (Table 2). When D-dimer was divided into quintiles (Table 3), there was little evidence for a consistent association in blacks or whites for stroke in either the demographic or the risk factor-adjusted models. There was an association for CHD, with the highest D-dimer quintile having an HR of 1.73 (95% CI 1.02, 2.93) for CHD. While the point-estimate was greater for blacks (HR 2.41; 95% CI 1.08, 5.29) than whites (HR 1.50; 95% CI 0.73, 3.08) in the risk factor adjusted model, the interaction between D-dimer and race was not significant (pinteraction = 0.24). There was no sex by D-dimer interaction (continuous analysis) in the risk factor adjusted model for stroke or CHD.

Table 2.

Association of Baseline D-dimer with Cardiovascular Disease Risk

| Per Doubling D-dimer | Difference in HR (CHD – Stroke, 95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHD HR (95% CI) |

Stroke HR (95% CI) |

||

| Demographic Model* | |||

| Entire cohort | 1.32 (1.17, 1.50) | 1.20 (1.07, 1.35) | 0.12 (−0.04, 0.31) |

| Blacks | 1.41 (1.19, 1.67) | 1.18 (1.00, 1.40) | 0.23 (0.01, 0.56) |

| Whites | 1.24 (1.04, 1.48) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.44) | 0.02 (−0.20, 0.23) |

| p-interactionrace* D-dimer | 0.30 | 0.80 | |

| Risk Factor Model† | |||

| Entire Cohort | 1.27 (1.11, 1.45) | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 0.12 (−0.07, 0.33) |

| Blacks | 1.33 (1.11, 1.59) | 1.12 (0.92, 1.34) | 0.20 (0.00, 0.58) |

| Whites | 1.21 (1.01, 1.47) | 1.19 (0.99, 1.42) | 0.02 (−0.30, 0.27) |

| p-interactionrace* D-dimer | 0.49 | 0.60 | |

CHD: Adjusted for age, sex, region, and race

Stroke: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, and age*race

CHD: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and taking cholesterol-lowering medications

Stroke: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, age*race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, baseline cardiovascular disease, baseline atrial fibrillation, and baseline left ventricular hypertrophy

Table 3.

Association of Baseline D-dimer Quintiles with Cardiovascular Disease Risk

| CHD HR (95% CI) |

Stroke HR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Blacks | Whites | All | Blacks | Whites | |

| Demographic Model* | ||||||

| Quintile 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Quintile 2 | 0.96 (0.60, 1.56) | 1.00 (0.46, 2.15) | 0.99 (0.53, 1.83) | 1.10 (0.70, 1.73) | 0.55 (0.26, 1.14) | 1.67 (0.93, 2.98) |

| Quintile 3 | 1.35 (0.85, 2.14) | 1.46 (0.72, 2.99) | 1.34 (0.74, 2.42) | 1.28 (0.83, 1.96) | 1.02 (0.53, 1.96) | 1.43 (0.81, 2.51) |

| Quintile 4 | 1.99 (1.25, 3.17) | 2.61 (1.28, 5.34) | 1.72 (0.94, 3.13) | 1.49 (0.97, 2.28) | 1.02 (0.52, 2.02) | 1.83 (1.06, 3.18) |

| Quintile 5 | 2.17 (1.33, 3.52) | 2.77 (1.34, 5.73) | 1.86 (0.98, 3.93) | 1.55 (0.99, 2.42) | 1.15 (0.57, 2.29) | 1.78 (0.99, 3.20) |

| Risk Factor Model† | ||||||

| Quintile 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Quintile 2 | 0.90 (0.54, 1.51) | 0.96 (0.41, 2.24) | 0.91 (0.46, 1.81) | 1.14 (0.70, 1.86) | 0.60 (0.27, 1.31) | 1.71 (0.90, 3.25) |

| Quintile 3 | 1.14 (0.69, 1.87) | 1.29 (0.58, 2.87) | 1.11 (0.56, 2.19) | 1.23, 0.76, 1.97) | 1.09 (0.53, 2.22) | 1.31 (0.69, 2.47) |

| Quintile 4 | 1.44 (0.86, 2.41) | 2.31 (1.05, 5.10) | 1.12 (0.55, 2.27) | 1.09 (0.67, 1.78) | 0.86 (0.41, 1.81) | 1.21 (0.63, 2.31) |

| Quintile 5 | 1.73 (1.02, 2.93) | 2.41 (1.08, 5.39) | 1.50 (0.73, 3.08) | 1.39 (0.85, 2.28) | 1.03 (0.48, 2.20) | 1.71 (0.90, 3.24) |

CHD: Adjusted for age, sex, region, and race

Stroke: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, and age*race

CHD: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and taking cholesterol-lowering medications

Stroke: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, age*race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, baseline cardiovascular disease, baseline atrial fibrillation, and baseline left ventricular hypertrophy

Comparison of the Association of D-dimer with CHD and Stroke

Though the point estimate of the association of D-dimer was higher for CHD than for stroke in the risk factor model (1.27 vs 1.15), this difference was not statistically significant (difference in HR between CHD and stroke 0.12; 95% CI for the difference −0.07, 0.33). However, when stratified by race, the association of D-dimer was significantly greater in CHD than stroke in blacks (difference in HR for CHD minus stroke 0.20; 95% CI >0.00, 0.58) but not whites (difference in HR for CHD minus stroke 0.02; 95% CI −0.30, 0.27).

Mediation Analysis

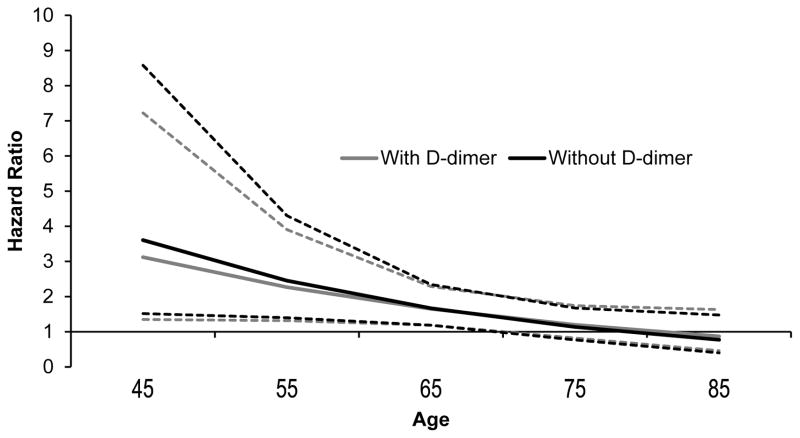

The HR of D-dimer with stroke decreased non-significantly by 13.3% (95% CI 0.0%, 40.0%) when CRP was added to the model 2 (Table 4). In contrast, the HR of D-dimer with CHD decreased significantly by 22.7% (95% CI 5.5%, 41.1%) when CRP was added to model 2 (Table 4). Figure 1 presents the association of race with stroke with and without D-dimer in the risk factor model at various ages. Consistent with prior studies, the hazard ratio for black race with stroke was highest at younger ages with a p-interaction between age and race of 0.03 in the risk factor model. Though addition of D-dimer to the risk factor model decreased the HR for the association of black race with stroke, this difference was not significant at any age (Figure 1). There was no age by race interaction for CHD (p-interaction = 0.39) in the risk factor adjusted model and there was no association of race with CHD in the main cohort.

Table 4.

Attenuation of the Association of D-dimer with Cardiovascular Disease by CRP*

| Stroke | CHD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per Doubling of D-dimer | Percent Decrease in HR (Without - With CRP) | Per Doubling of D-dimer | Percent Decrease in HR (Without - With CRP) | |||

| HR for D-dimer | HR for D-dimer adjusted for CRP | HR D-dimer | HR for D-dimer adjusted for CRP | |||

| All | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 1.13 (0.99, 1.29) | 13.3% (0.0%, 40.0%) | 1.27 (1.11, 1.45) | 1.22 (1.05, 1.40) | 22.7% (5.5% 41.1%) |

| Blacks | 1.12 (0.92, 1.34) | 1.08 (0.89, 1.31) | 33.3% (0.0%, 67.5.0%) | 1.33 (1.11, 1.59) | 1.28 (1.06, 1.55) | 15.1% (0.6%, 33.0%) |

| Whites | 1.19 (0.99, 1.42) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.40) | 10.5% (0.0%, 27.9%) | 1.21 (1.01, 1.47) | 1.15 (0.94, 1.40) | 28.5% (6.7%, 61.9%) |

CHD: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and taking cholesterol-lowering medications

Stroke: Adjusted for age, sex, region, race, age*race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, diabetes, current smoking, baseline cardiovascular disease, baseline atrial fibrillation, and baseline left ventricular hypertrophy

Figure 1.

Mediation of the Association of Black Race with Stroke by D-dimer by Age

Heavy lines represent the Hazard Ratio, dashed lines 95% CI. Percent mediation (95% CI): Age 45: 18% (−6%, 69%), Age 55: 12% (−9%, 42%), Age 65: 3% (−17%, 24%); Age 75: 43% (−120%, 26%); Age 85: No increased risk for blacks.

Sensitivity analyses excluding haemorrhagic strokes (n = 73) did not change the interpretation of the results, nor did excluding participants with both prevalent stroke and CHD from all analyses (data not shown).

Discussion

Higher D-dimer was associated with stroke and CHD in blacks and whites. For blacks, the association of D-dimer was stronger for CHD than stroke, while the association was similar in whites. Higher CRP significantly decreased (but did not eliminate) the association of D-dimer with CHD but had no effect on the association of D-dimer with stroke. While D-dimer did decrease the excess risk of stroke seen in blacks at younger ages this did not reach statistical significance.

There is little doubt that there is an association of baseline elevated D-dimer with future cardiovascular disease events as most prior studies report an increased risk of cardiovascular events with higher D-dimer(5, 7–9). As seen in Table 1, higher D-dimer is correlated with adverse levels of many cardiovascular risk factors, but also with higher levels of HDL cholesterol. The pathophysiology between D-dimer and cardiovascular risk factors is not understood, however despite adjusting for these risk factors, D-dimer remained associated with cardiovascular risk. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, including 587 incident stroke and transient ischemic attack events in an elderly white population, the HR for cerebrovascular events was 1.65 (95% CI 1.19, 2.29) for the top compared to the bottom quintile of D-dimer, compared to a HR of 1.39 reported here(8). In the same analysis in CHS, with 739 CHD events, the HR of CHD for those in the 5th compared with the 1st quintile of D-dimer was 1.57 (95% CI 1.20, 2.04), compared to 1.73 reported here(8). In a meta-analysis with 1,535 CHD events, the top tertile of D-dimer was associated with an OR of 1.7 (95% CI 1.3, 2.2) for CHD, compared to the bottom tertile. In two of three studies that reported a combined CVD outcome (including stroke and CHD), higher D-dimer was associated with CVD events(7–9). In Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, the association of D-dimer with cardiovascular events was attenuated by adjustment for demographics and cardiovascular risk factors, but the total number of cardiovascular disease events was less than a quarter of the number of events in the current study(9).

The current study extends these observations as we assessed whether there was any difference by race, by cardiovascular disease type, and whether CRP, a biomarker of inflammation impacted the association of D-dimer with cardiovascular disease. While the end pathophysiology is similar in most cardiovascular disease, a thrombus blocking an artery, the underlying processes leading to tissue ischemia can differ(23). Prevention of cardiovascular disease has focused on traditional risk factor modification (namely hypertension and lipids) and to a lesser extent treatment with antiplatelet agents(24). What is lacking is a more refined approach targeting individualized underlying pathophysiology of potential cardiovascular disease rather than overall cardiovascular disease risk.

Anticoagulation therapies have been investigated for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. For stroke prevention, warfarin is superior to antiplatelet agents among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation(25) and may confer a slight advantage in the setting heart failure and normal sinus rhythm but at the cost of more bleeding events(26). In the primary prevention of CHD, warfarin is as efficacious as aspirin and may provide additional benefit when added to aspirin but at the cost of increased bleeding(27). While D-dimer has not been shown to improve risk stratification for cardiovascular disease(7, 8), our findings may offer insights into future individualized targeted approaches to prevent cardiovascular disease, perhaps specifically for CHD in blacks. Assuming D-dimer is a marker of activated coagulation, elevated levels may help identify a patient population who could benefit more from agents targeted at haemostasis rather than platelet function or lipids for primary prevention(28). Extreme caution and well-designed clinical trials are needed before using haemostasis biomarkers to determine the best primary prevention strategy in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease.

While REGARDS is a large national study, the design of REGARDS introduces both strengths and weaknesses over prior studies with participants centred on recruiting centres; REGARDS has a significant number of participants from rural areas which increases the generalizability of the findings, but potentially introduces a greater variation in the standards of care for stroke and CHD. Additionally, REGARDS assessed D-dimer at only at one time point. D-dimer varies depending on the acute health status of the participant, however this would tend to bias our results towards the null. Despite these weaknesses, out data demonstrate that D-dimer is associated with both stroke and CHD risk and that D-dimer may shed light onto different pathophysiologies of cardiovascular disease by cardiovascular disease type and race.

In summary, higher D-dimer was associated with an increased risk of stroke and CHD in REGARDS. The association was stronger for CHD, especially in blacks than whites suggesting coagulation may play a greater role in CHD in blacks. From a clinical standpoint, our data introduce the idea that haemostasis may play a different role in the pathogenesis of vascular disease by site (stroke versus CHD) and by race (black versus white) and that studies incorporating primary prevention strategies targeting individualized cardiovascular disease risk profiles are needed to reduce cardiovascular disease in all individuals.

Extra Table.

| What is Known | Elevated D-dimer levels are associated with cardiovascular disease |

| Cardiovascular disease incidence varies by race | |

| D-dimer levels vary by race | |

| What this Paper Adds | Elevated D-dimer is a greater risk factor for coronary heart disease than stroke |

| The increased risk for coronary heart disease is greater in American Blacks than whites | |

| The association of D-dimer with cardiovascular disease is not dependent on elevated biomarkers of inflammation |

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States of America.

Author roles: conception and design of analysis and interpretation of data: N. A. Zakai, L. A. McClure, S. E. Judd, B. Kissela, G. Howard, M. M. Safford, M. Cushman; funding: N. A. Zakai, G. Howard, M. M. Safford; drafting of the manuscript (N. A. Zakai) and critical revision (L. A. McClure, S. E. Judd, B. Kissela, G. Howard, M. M. Safford, M. Cushman).

This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service, Bethesda, MD, United States. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org. Additional funding was also secured from K08HL096841 (PI N. Zakai) and R01HL080477 (PI M. Safford) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service, Bethesda, MD, United States.

References

- 1.Bhatia M, Rothwell PM. A systematic comparison of the quality and volume of published data available on novel risk factors for stroke versus coronary heart disease. Cerebrovascular diseases. 2005;20(3):180–6. doi: 10.1159/000087202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gliksman M, Wilson A. Are hemostatic factors responsible for the paradoxical risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke? Stroke. 1992;23(4):607–10. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qizilbash N. Are risk factors for stroke and coronary disease the same? Current opinion in lipidology. 1998;9(4):325–8. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam SS, Key NS, Greenberg CS. D-dimer antigen: current concepts and future prospects. Blood. 2009;113(13):2878–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danesh J, Whincup P, Walker M, et al. Fibrin D-dimer and coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2001;103(19):2323–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.19.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May M, Lawlor DA, Patel R, et al. Associations of von Willebrand factor, fibrin D-dimer and tissue plasminogen activator with incident coronary heart disease: British Women’s Heart and Health cohort study. European journal of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation : official journal of the European Society of Cardiology, Working Groups on Epidemiology & Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology. 2007;14(5):638–45. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280e129d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzoulaki I, Murray GD, Lee AJ, et al. Relative value of inflammatory, hemostatic, and rheological factors for incident myocardial infarction and stroke: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Circulation. 2007;115(16):2119–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zakai NA, Katz R, Jenny NS, et al. Inflammation and hemostasis biomarkers and cardiovascular risk in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2007;5(6):1128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folsom AR, Delaney JA, Lutsey PL, et al. Associations of factor VIIIc, D-dimer, and plasmin-antiplasmin with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(6):349–53. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutsey PL, Wassel CL, Cushman M, et al. Genetic admixture is associated with plasma hemostatic factor levels in self-identified African Americans and Hispanics: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(4):543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Steffen LM, et al. Plasma hemostatic factors and endothelial markers in four racial/ethnic groups: the MESA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(12):2629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard G, Cushman M, Kissela BM, et al. Traditional risk factors as the underlying cause of racial disparities in stroke: lessons from the half-full (empty?) glass. Stroke. 2011;42(12):3369–75. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–43. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Annals of neurology. 2011;69(4):619–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.22385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillett SR, Boyle RH, Zakai NA, et al. Validating laboratory results in a national observational cohort study without field centers: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke cohort. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(16–17):243–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safford MM, Brown TM, Muntner PM, et al. Association of race and sex with risk of incident acute coronary heart disease events. Jama. 2012;308(17):1768–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luepker RV, Apple FS, Christenson RH, et al. Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: a statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2003;108(20):2543–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100560.46946.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, et al. Analysis of case-cohort designs. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1999;52(12):1165–72. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulathinal S, Karvanen J, Saarela O, et al. Case-cohort design in practice - experiences from the MORGAM Project. Epidemiologic perspectives & innovations : EP+I. 2007;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cushman M, Judd SE, Howard VJ, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and stroke risk: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke cohort. Stroke. 2014;45(6):1646–50. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zakai NA, Judd SE, Alexander K, et al. ABO blood type and stroke risk: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2014;12(4):564–70. doi: 10.1111/jth.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(3):312–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott J. Pathophysiology and biochemistry of cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(3):271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 2002;106(3):388–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal S, Hachamovitch R, Menon V. Current trial-associated outcomes with warfarin in prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):623–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.121. discussion 31–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar G, Goyal MK. Warfarin versus Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke in Heart Failure: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacCallum PK, Brennan PJ, Meade TW. Minimum effective intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy in primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(16):2462–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Force USPST. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(6):396–404. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]