Abstract

The amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) are key regulators of sodium and potassium and colocalize in the late distal convoluted tubule of the kidney. Loss of the αENaC subunit leads to a perinatal lethal phenotype characterized by sodium loss and hyperkalemia resembling the human syndrome pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 (PHA-I). In adulthood, inducible nephron-specific deletion of αENaC in mice mimics the lethal phenotype observed in neonates, and as in humans, this phenotype is prevented by a high sodium (HNa+)/low potassium (LK+) rescue diet. Rescue reflects activation of NCC, which is suppressed at baseline by elevated plasma potassium concentration. In this study, we investigated the role of the γENaC subunit in the PHA-I phenotype. Nephron-specific γENaC knockout mice also presented with salt-wasting syndrome and severe hyperkalemia. Unlike mice lacking αENaC or βΕΝaC, an HNa+/LK+ diet did not normalize plasma potassium (K+) concentration or increase NCC activation. However, when K+ was eliminated from the diet at the time that γENaC was deleted, plasma K+ concentration and NCC activity remained normal, and progressive weight loss was prevented. Loss of the late distal convoluted tubule, as well as overall reduced βENaC subunit expression, may be responsible for the more severe hyperkalemia. We conclude that plasma K+ concentration becomes the determining and limiting factor in regulating NCC activity, regardless of Na+ balance in γENaC-deficient mice.

Keywords: epithelial sodium channel, Pseudohypoaldosteronism, thiazide-sensitive, Na+/Cl- co-transporter, SPAK

In humans, mutations in the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), composed of three highly homologous subunits (α, β, and γ)1,2 are causative for the systemic form of pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 (PHA-I) resulting in Na+ loss, metabolic acidosis, dehydration, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and, if untreated, perinatal lethality.3 ENaC is expressed in tight epithelia, like in the principal cells of the distal tubule and the collecting duct, the distal colon, and of several excretory ducts, where it determines Na+ and K+ homeostasis and regulates BP.4 Germline deletion of each of the subunit genes in mice results in perinatal lethality.5–7 In vitro, maximal ENaC activity is only achieved with all three (αβγ) ENaC subunits present, whereas coexpression of either αβENaC or αγENaC subunits in Xenopus oocytes leads to an about 100-fold reduced amiloride-sensitive Na+ current. Expression of the γENaC subunit alone reveals no ENaC-mediated current.2 This is confirmed by ex vivo experiments where amiloride-sensitive transepithelial potential difference is measured in tracheal explants from constitutive α and γENaC knockout mice. Whereas αENaC-deficient explants show no ENaC activity, a remaining 15% ENaC activity is measured in explants from γENaC knockout mice.5,7 Furthermore, in vitro data demonstrate that the γENaC may be more important for channel surface expression and trafficking than the βENaC subunit.8 Interestingly, specific pore-lining residues in the second transmembrane domain of the γENaC subunits are responsible for both, the gating of ENaC channel and the amiloride interaction, and channels lacking the γENaC subunit exhibit a higher open probability and decreased sensitivity to amiloride compared with αγ- or αβγ-containing ENaC channels.9 Likewise, proteolytic cleavage of γENaC has a specific role in ENaC activation by serine proteases as demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo experiments.10 In rat kidneys, the abundance of the full-length form (90-kD) of γENaC subunit is decreased, whereas the cleaved form (70-kD) is increased under a low Na+ diet.11 Aldosterone infusion or high K+ diet feeding in rats leads to changes in the processing and maturation of the different ENaC subunits in kidney.11 Under a Na+-depleted diet, the stimulation of ENaC activity in rats results in an increase of the cleaved γENaC subunit in the Golgi.12 Recently, it was demonstrated that proteolytic cleavage of the γENaC subunit occurs also in human kidney and in patients with proteinuria.13 Overall, these data indicate that the γ subunit has a specific physiologic role in channel function and its hormonal regulation.

A negative linear relationship between the plasma K+ concentration and the abundance of the phosphorylated form of the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) was demonstrated in several studies,14,15 and was consistent with data from conditional adult αENaC knockout mice,16 missing the αENaC subunit in the kidney revealing an aldosterone-independent but K+-dependent NCC regulation.

In this study, we further addressed whether renal tubular ENaC channels consisting of αβ (lacking the γENaC subunit) along the adult nephron generate sufficient ENaC activity to prevent salt wasting, severe hyperkalemia, and lethality, characteristic of systemic PHA-I.

Results

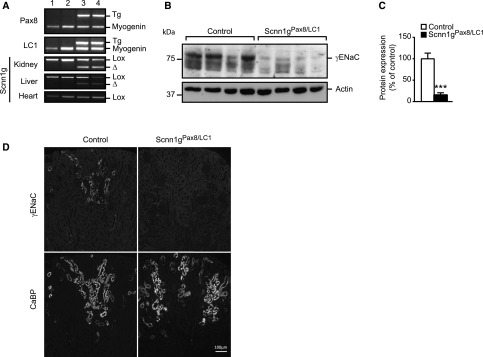

Adult Nephron-Specific γENaC-Deficient Mice Develop a Severe Hyperkalemia

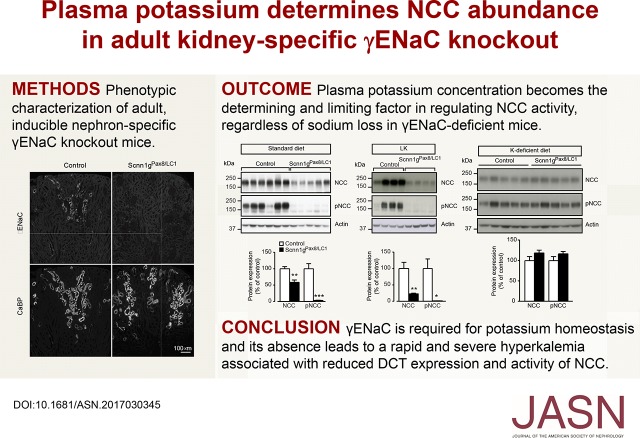

Treatment of 1-month-old control and experimental conditional gENaC knockout mice with doxycycline and standard diet (protocol A; Supplemental Figure 1A) resulted in efficient gene targeting in kidneys as revealed by DNA and protein expression (17% of controls; P<0.001) levels (Figure 1A). Moderate recombination was found in the liver, but not in the heart (Figure 1A, lane 3 and 4). In kidney, Western blot analyses revealed a significant decrease of γENaC protein in experimental animals (Figure 1, B and C). This was further confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1D). Four-week-old γENaC knockout and control mice were fed with a standard diet and placed in metabolic cages (protocol A; Supplemental Figure 1A). Control mice were still in their growing phase and thus kept gaining weight. Because of the sickness and rapid body weight loss observed in γENaC knockout mice, the experiment was interrupted at day 3 of doxycycline treatment (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 1A). The mice presented with clinical symptoms of severe PHA-1 characterized by significant lower plasma Na+ concentration and severe hyperkalemia (Figure 2B). This was accompanied by a >13-fold increase of the plasma aldosterone level (Table 1) and decreased food and feces output (Supplemental Figure 2, A and C). The 24-hour water intake and urine volume remained stable (Supplemental Figure 2, B and D). Consistent with the decrease of food intake, the 24-hour Na+ and K+ intake was significantly lowered (Supplemental Figure 2, E and F). Although 24-hour urinary Na+ excretion was increased at day 2 and normalized thereafter (Figure 2C), the 24-hour K+ excretion was significantly lowered at day 3 (Figure 2D). In addition, food and Na+ intake were significantly decreased (Supplemental Figure 2, A and E) and the whole Na+ balance became negative in knockout animals. Furthermore, γENaC knockout mice exhibited severe dehydration consistent with increased hematocrit, plasma osmolality, and urea (Table 2). No significant effect was seen in plasma glucose levels and urine volume and osmolality, as well as in the urine-to-plasma osmolality ratio and creatinine clearance (Table 2). Hence, γENaC-deficient mice develop a PHA-I phenotype characterized by a severe hyperkalemia and dehydration.

Figure 1.

Efficient recombination of γENaC in kidneys of inducible nephron-specific γENaC knockout mice. (A) Genotyping using Scnn1g-specific PCR primers on DNA extracted from kidney, liver, and heart from controls (lanes 1 and 2) and experimental (knockout, Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice (lanes 3 and 4); note absence of recombination in controls (lanes 1 and 2) and the presence of recombination in the liver (lanes 3 and 4). (B) Western blot analyses of whole kidneys and (C) their quantification 2 days after induction in γENaC control and experimental mice. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin and expressed in percentage of control. (D) Immunofluorescence detection of γENaC and CaBP in consecutive kidney sections from control or knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice after 2 days of standard diet; protocol A. Results are presented as mean±SEM and data were analyzed by unpaired t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. ***P<0.001.

Figure 2.

Adult γENaC-deficient mice develop a severe PHA-1 phenotype. (A) Body weight changes (Δ body weight) in percentage of initial body weight monitored during three consecutive days after doxycycline induction on a standard diet (protocol A); Scnn1g: each group, n=5. (B) Measurement of plasma electrolytes, Na+ (left) and K+ (right, mmol/L) in γENaC control (n=7) and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1, n=6) mice. Measurement of urinary Na+ (C) and K+ (D) excretion (mmol/24 h per gram of body weight) in γENaC control and knockout (each group, n=5) mice; protocol A. Values were normalized to the body weight. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

Table 1.

Serum aldosterone concentration in γENaC control and experimental mice

| Plasma Aldosterone, nM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Control Mice | Experimental Mice |

| Standard diet | 2.8±0.3 (3) | 36.6±7.8 (3)a |

| LK+ diet | 0.6±0.2 (5) | 17.7±2.4 (5)b |

Values are given as mean±SEM; number of mice indicated in parentheses. Plasma aldosterone was measured as described in Concise Methods. For each group, γENaC knockout (experimental) mice were compared with their diet-matched control mice; LK+, low potassium.

P<0.05.

P<0.001.

Table 2.

Balance of whole body fluid of γENaC control and knockout (experimental) mice

| Parameters | Standard Diet, protocol A (+3 d) | |

|---|---|---|

| γENaC | ||

| Control Mice | Experimental Mice | |

| Hematocrit, % | 46±0.3 (5) | 59.2±1.3 (5)a |

| Plasma Na+, mmol/L | 149.5±1.1 (6) | 146.3±1 (4)b |

| Plasma K+, mmol/L | 4.7±0.3 (6) | 9±1.1 (6)c |

| Plasma urea, mmol/L | 19±0.7 (7) | 55.7±3.3 (7)a |

| Plasma glucose, mmol/L | 12.6±0.5 (7) | 11±0.5 (7)b |

| Plasma Osm (calculated) | 341.4 (6) | 377 (6) |

| Plasma Osmolality, mOsm/kg H2O | 320.7±1.5 (6) | 367.8±10.3 (6)c |

| Plasma creatinine, mg/dl per 24 h | 0.2±0.02 (6) | 0.2±0.01 (6)b |

| Volume urine, ml/24 h | 0.8±0.2 (6) | 0.9±0.3 (6)b |

| Urine creatinine, mg/dl per 24 h | 35.5±6.6 (6) | 39±3.6 (6)b |

| Urine osmolality, mOsm/kg H2O | 3480.7±394.7 | 4875.3±1005.8b |

| Creatinine clearance, µl/min | 89.7±4 (6) | 129.8±39.7 (6)b |

| U/Posm | 10.9±1.2 (6) | 13±2.4 (6)b |

Values are given as mean±SEM; number of mice is indicated in parentheses. γENaC knockout mice were compared with their corresponding control mice. Osm, osmolality; U/Posm, urine-to-plasma osmolality ratio.

P<0.001.

NS.

P<0.01.

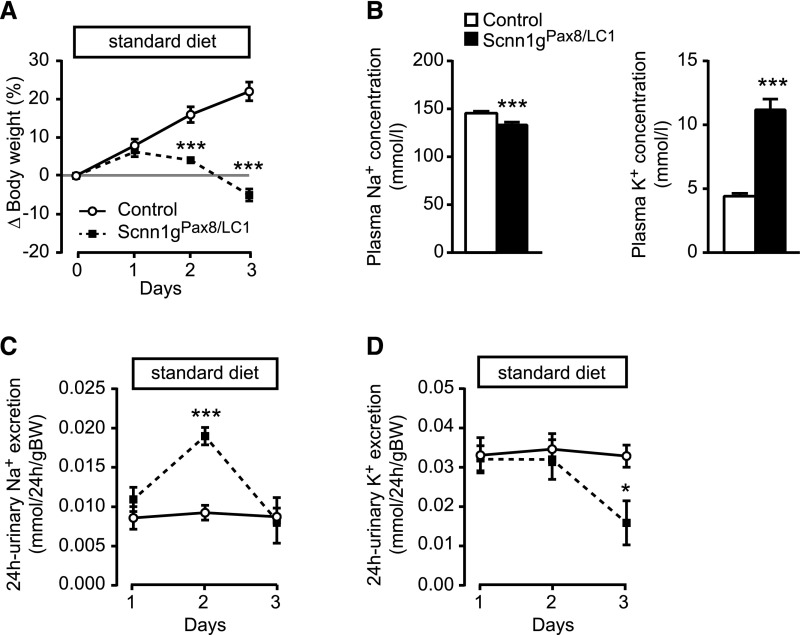

γENaC Knockout Mice Are Not Rescued on Low Potassium Diet and High or Standard Sodium Diet

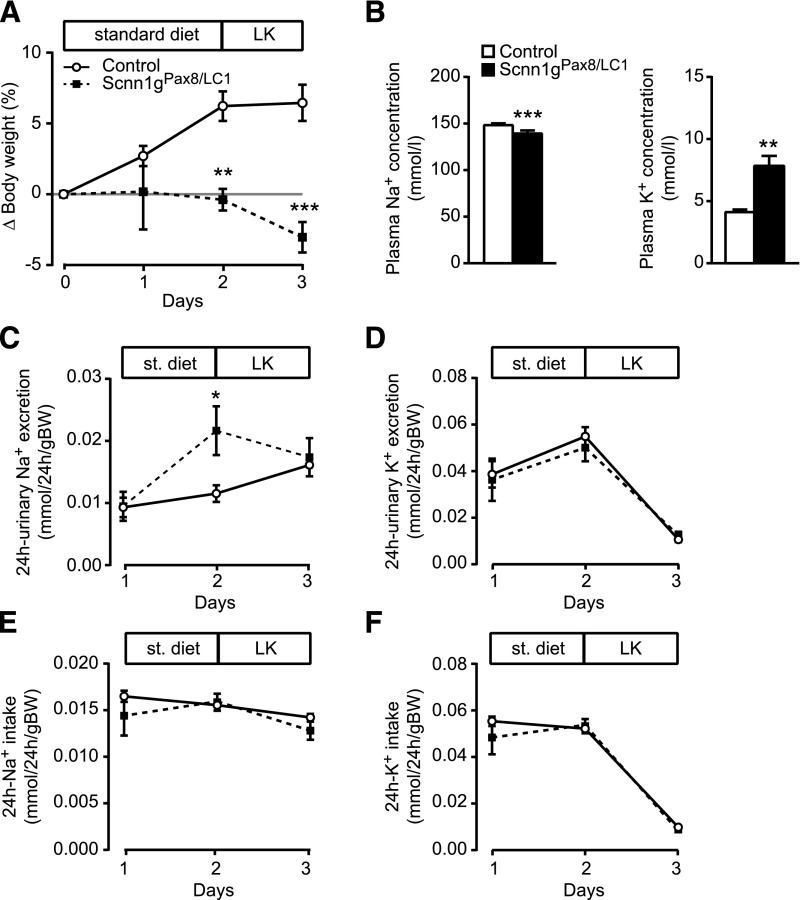

To determine if the severe PHA-I phenotype is rescued as previously observed in αENaC-deficient mice,16 γENaC knockout was induced by doxycycline. Mice were kept for 3 days under a standard diet, and then switched to a HNa+ and LK+ diet (protocol B, Supplemental Figure 1) and parameters were measured every 6 hours to monitor rapid changes. γENaC knockout mice continued to lose weight (Figure 3A), and presented with a highly significant and severe hyperkalemia and lower plasma Na+ concentration (Figure 3B). Urinary Na+ and K+ excretion (Figure 3, C and D) and Na+ and K+ intake (Figure 3, E and F) significantly differed from controls, and γENaC knockout mice stopped eating and had significantly decreased food and water consumption, feces output, and urine volume (Figure 3, C and E, Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adult γENaC-deficient mice present severe hyperkalemia under HNa+/LK+ diet. (A) Body weight changes (Δ body weight) of γENaC control and experimental (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice (each group: n=8) in percentage of initial body weight on a standard and short-term HNa+/LK+ diet (protocol B). (B) Measurements of plasma Na+ (left) and K+ (right) concentrations (mmol/L) in γENaC control and knockout mice (each group, n=8) at 18 hours after diet switch. Measurement of (C) urinary Na+ and (D) K+ excretion (mmol/gram of body weight), and (E) Na+ and (F) K+ intake (mmol/gram of body weight) in γENaC control and knockout (each group, n=8) mice after doxycycline treatment on a standard diet (24-hour) and HNa+/LK+ diet (6-hour measurement); protocol B. Values were normalized to the body weight. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

A LK+ but standard Na+ diet (LK+; protocol C, Supplemental Figure 1) equally resulted in significant weight loss, lower plasma Na+ concentration and hyperkalemia (Figure 4, A and B). Plasma aldosterone concentrations were significantly increased in γENaC knockout mice (Table 1). Although urinary Na+ excretion is increased on the second day under standard diet and normalized under LK+ diet (Figure 4C), the urinary K+ excretion (Figure 4D), the Na+ and K+ intake (Figure 4, E and F), food consumption, feces output, and urine volume (Supplemental Figure 4, A, C, and D) did not differ between control and experimental mice under both standard and LK+ diet. Water intake is even increased in experimental mice in comparison to control littermates (Supplemental Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Short-term LK+ diet fails to normalize the body weight and the plasma electrolytes of γENaC-deficient mice. (A) Body weight changes (Δ body weight) in percentage of initial body weight, and (B) plasma Na+ (left) and K+ (right) concentrations (mmol/L) under low potassium diet (protocol C) in control and knockout mice (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) (each group, n=6). Twenty-four-hour urinary (C) Na+ and (D) K+ excretion (mmol/24 h per gram of body weight), and (E) 24 hours Na+ and (F) K+ intake (mmol/24 h per gram of body weight) in controls and knockout mice (each group, n=6); values (A) and (C–F) are normalized to body weight. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

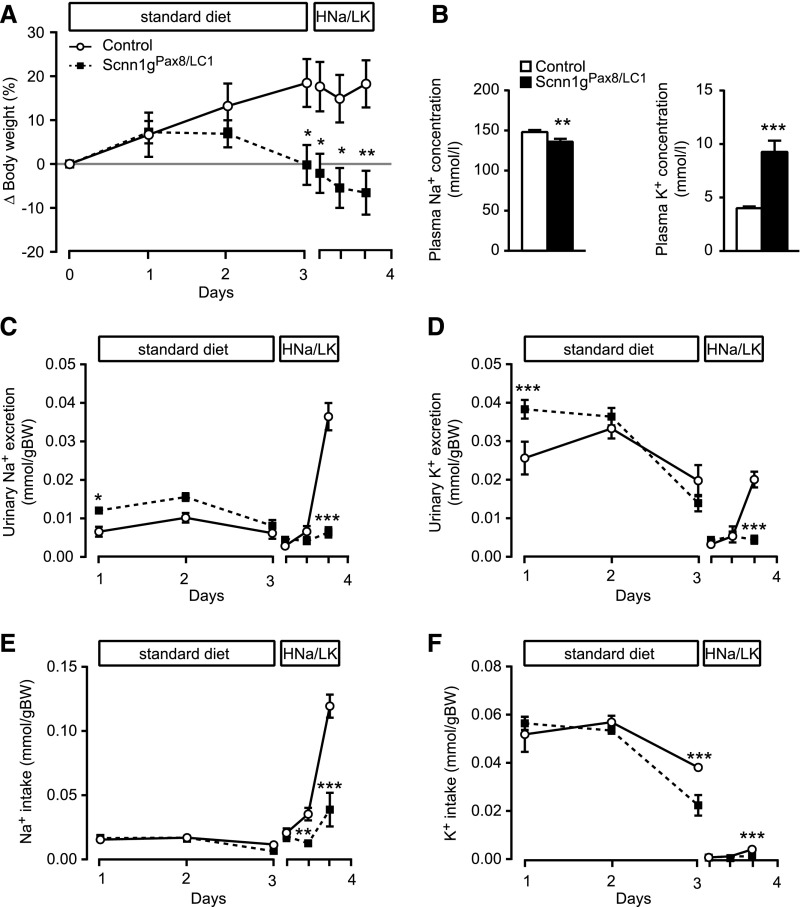

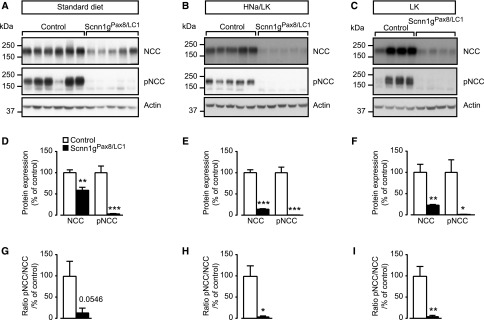

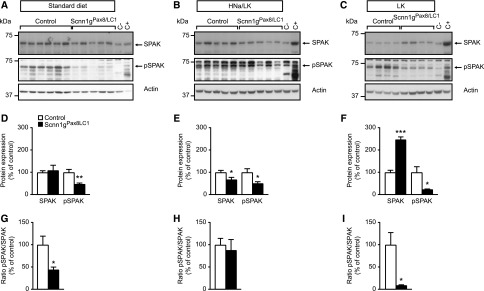

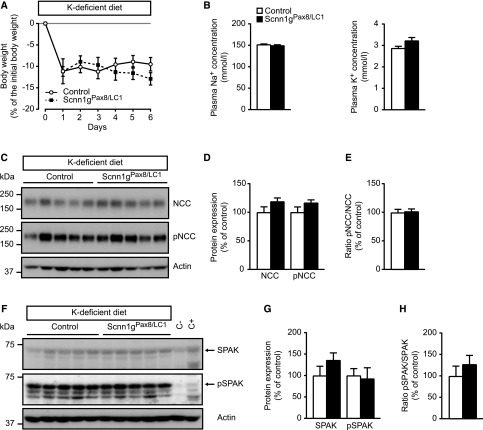

HNa+/LK+ or LK+ Diet Does Not Restore NCC and SPAK Expression in γENaC Knockout Mice

Because the NCC is differently regulated through a high Na+17 or a low K+ diet,18 we further analyzed total and phosphorylated NCC protein expression in cortex-enriched kidney lysate from γENaC control and knockout mice kept under standard (protocol A), HNa+/LK+ (protocol B), and LK+ diet (protocol C) (Figure 5). Under standard diet (Figure 5, A and D), HNa+/LK+ diet (Figure 5, B and E), and LK+ diet (Figure 5, C and F), experimental mice exhibited a downregulation of both total and phosphorylated (T53) form of NCC protein expression. The ratio of NCC phosphorylation to the total expression was decreased on each of the diets (Figure 5, G–I). The phosphorylation of SPAK (Figure 6) followed the same pattern of expression as that of pT53-NCC (Figure 5) under standard diet (Figure 6, A and D), HNa+/LK+ (Figure 6, B and E), and LK+ diet (Figure 6, C and F). Although SPAK activity (expressed as pSPAK to total SPAK ratio) followed the NCC activity under standard (Figure 6, A, D, and G) and LK+ (Figure 6, C, F, and I) diet, SPAK activity was unchanged under HNa+/LK+ diet (Figure 6, B, E, and H). Before doxycycline induction, protein abundances of NCC, pNCC, SPAK, and pSPAK did not significantly differ (Supplemental Figure 5). In summary, the severe hyperkalemia was not normalized in γENaC knockout mice on both LK+ and high or standard Na+ diets. This is consistent with the findings that NCC, pNCC, SPAK, and pSPAK expression were not normalized on both HNa+/LK+ and LK+ diets.

Figure 5.

Low potassium in combination with standard or high sodium diet does not normalize total NCC and pNCC in γENaC-deficient mice. (A) Representative Western blot analysis of total NCC, pNCC, and actin on kidney cortex extracts from control and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice on a standard diet; gENaC control, n=6 and knockout mice, n=5 (protocol A). (B) Short-term HNa+/LK+ diet (protocol B) in γENaC control and knockout mice; each group: n=5. (C) Short-term low potassium diet (1 day) in γENaC control and knockout group; each group: n=4 (protocol C). (D–F) Quantification of proteins and (G–I) ratio of pNCC to total NCC abundance from corresponding Western blot analyses. Protein levels are normalized to actin and expressed in percentage of control. Results are presented as mean±SEM and data were analyzed by unpaired t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Figure 6.

Low potassium in combination with standard or high sodium diet does not normalize pSPAK in γENaC-deficient mice. (A) Representative Western blot analyses of pSPAK and actin on kidney cortex extracts from control and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice on a standard diet; γENaC control, n=6 and knockout mice. n=5 (protocol A). (B) Short-term HNa+/LK+ diet (protocol B) in γENaC control and knockout mice; each group, n=5. (C) Short-term LK+ diet (1 day) in γENaC control and knockout group; each group, n=4 (protocol C). (D–F) Quantification of proteins and (G–I) ratio of pSPAK to total SPAK abundance from corresponding Western blot analyses. Kidneys from SPAK knockout mice were used as negative controls. Protein levels are normalized to actin and expressed in percentage of control. C−, kidney protein lysate from SPAK-deficient (negative control); C+, from SPAK wildtype mice (positive control). Results are presented as mean±SEM and data were analyzed by unpaired t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

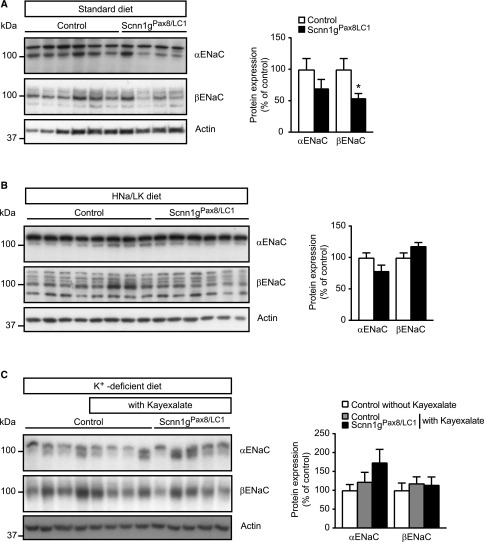

γENaC Knockout Mice Are Rescued on a Kayexalate-Supplemented K+-Deficient Diet But Still Present with Low NCC Activity and Salt Wasting

On a standard diet and unlike αENaC subunit expression, βENaC subunit expression was significantly downregulated in γENaC-deficient mice, consistent with a loss in apical βENaC subunit expression within the DCT2 (Figures 7A and 8; protocol A). In contrast, on a HNa+/LK+ diet, βENaC subunit abundance did not differ (Figure 7B, protocol B). To analyze whether inhibiting K+ entry further prevents body weight loss and severe hyperkalemia, a K+-deficient diet was applied 2 days before doxycycline induction (day −2). Mice were additionally treated with a K+-chelator at day 0 (kayexalate; protocol D, Supplemental Figure 1). After an initial body weight loss at day 1, control mice without kayexalate maintained a 10% reduced body weight, whereas control and knockout mice treated with kayexalate between day 2 and day 11 of doxycycline induction regained weight (Supplemental Figure 6). At day 16, mice were placed into metabolic cages to determine the physiologic parameters (protocol D, Supplemental Figures 1, 7, and 8). With few exceptions, the control mice with or without kayexalate behaved similarly and differed from the knockout group with respect to further weight gain, 24-hour urinary Na+ excretion, (Supplemental Figure 7). The latter showed salt wasting despite near-normalized 24-hour Na+ intake (Supplemental Figure 7, B and D). Twenty-four-hour urinary K+ excretion did only differ at day 20 (Supplemental Figure 7, C and E). At day 18 and 20 after doxycycline induction, knockout mice consumed significantly less compared with controls (Supplemental Figure 7F). Water intake, feces weight, and urine volume did not differ between groups (Supplemental Figure 7, G–I). α and βENaC subunit abundances did not differ (Figure 7C, protocol D).

Figure 7.

The βENaC subunit expression is reduced on a standard diet in γENaC-deficient mice. (A–C) Representative Western blot analyses for α and βENaC on whole kidney protein extracts from γENaC control and knockout mice on (A) standard diet (control, n=6; knockout, Scnn1gPax8/LC1, n=4), (B) HNa+/LK+ (control, n=8; knockout, n=6), and (C) K+-deficient diet (control, n=4) plus kayexalate (control, n=4; knockout, n=5; left panels, and quantification of proteins from corresponding Western blot analyses; right panels, protocol D). Protein expression was normalized to the amount of β-actin and reported relative to control values. Results are presented as mean±SEM, and data were analyzed by unpaired t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P<0.05.

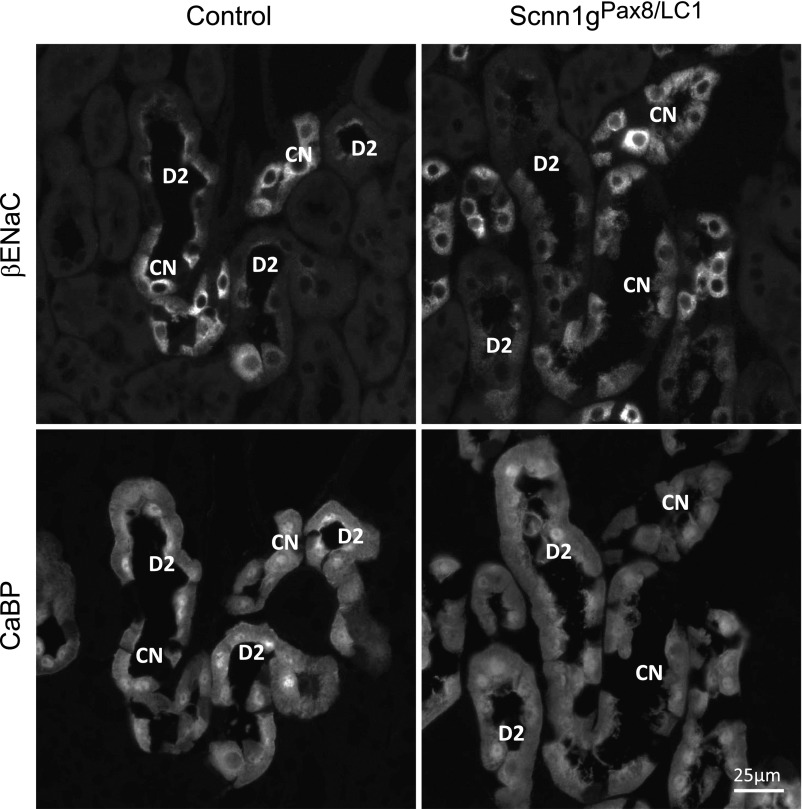

Figure 8.

Loss of apical βENaC subunit expression within the DCT2 in γENaC-deficient mice. Immunofluorescence detection of βENaC and CaBP in consecutive kidney sections from control (left) and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1, right) mice after 2 days of standard diet; protocol A. CN, CNT; D2, DCT2.

Interestingly, despite elevated plasma Na+ levels in the controls, knockout mice exhibited Na+ and K+ plasma concentrations within the normal range (Supplemental Figure 8, A and B), whereas controls showed hypokalemia (Supplemental Figure 8, A and B). Nevertheless, experimental mice still showed a reduced abundance of both the total (Supplemental Figure 8, C and E) and phosphorylated (T53) form (Supplemental Figure 8, D and F) of NCC compared with control littermates. The ratio of NCC phosphorylation/total expression was unchanged (Supplemental Figure 8G). The 24-hour fecal Na+ loss was significantly decreased, whereas the 24 hours fecal K+ was not altered in comparison to controls (Supplemental Figure 9, A and B). In controls treated with kayexalate-supplemented K+-deficient diet, 52% of the total Na+ intake was recovered in the feces and 48% in the urine. Experimental mice presented a fecal Na+ loss of 6% and a urinary Na+ loss of 94% (Supplemental Figure 9C). In control and experimental mice, the total recovery of the K+ intake was similar and accounted for 79% and 70% of fecal, and 21% and 30% of urinary K+ loss in control and experimental mice, respectively (Supplemental Figure 9D).

Preventive K+-Deficient Diet Restores Both NCC Activity and Plasma Potassium Concentration in γENaC Knockout Mice

To determine if a K+-deficient diet alone is sufficient to restore NCC activity, we treated mice with a K+-deficient diet at the same day (day 0) as doxycycline induction (protocol E, Supplemental Figure 1). The body weight of control and knockout groups rapidly decreased (by about 10%) after doxycycline induction, and was not significantly different (Figure 9A). Equally, after 6 days of treatment, both plasma Na+ and K+ levels were no longer different (Figure 9B). The NCC, pNCC, SPAK, and pSPAK abundances and the pNCC to NCC ratio did not differ in experimental and control mice (Figure 9, C–H). In summary, hyperkalemia in γENaC-deficient mice could be efficiently prevented by K+-deficient diet at the time of doxycycline induction. This suggests that plasma K+ concentration is the primary trigger to alter NCC abundance, which is thus independent of γENaC deficiency. However, once the mice develop hyperkalemia, the phenotype is not easily reversible, i.e., the NCC abundance and activity remained significantly lower, and this is dependent on the presence of γENaC subunit expression.

Figure 9.

γENaC-deficient mice do not differ from control mice under K+-deficient diet. (A) Body weight changes (Δ body weight) of γENaC control and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice (each group: n=9) in percentage of initial body weight on an LK+ diet (protocol E). (B) Measurements of plasma Na+ (left) and K+ (right) concentrations (mmol/L) in γENaC control and knockout mice (each group, n=9) at day 6 of diet application. (C) Representative Western blot analyses of total NCC, pNCC, and actin on kidney cortex extracts from control and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice on a K+-deficient diet. (D) Quantification of proteins and (E) ratio of pNCC to total NCC abundance from corresponding Western blot analyses. (F) Representative Western blot analyses of total SPAK, pSPAK, and actin on kidney cortex extracts from control and knockout (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice on a K+-deficient diet. (G) Quantification of proteins and (H) ratio of pSPAK to total SPAK abundance from corresponding Western blot analyses. Protein levels are normalized to actin and expressed in percentage of control. C−, kidney protein lysate from SPAK-deficient (negative control); C+, from SPAK wildtype mice (positive control). Results are presented as mean±SEM and data (B, D, E, G, H) were analyzed by unpaired t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Deletion of γENaC Subunits in Adult Nephrons Leads to Severe Hyperkalemia

Acute deletion of γENaC subunits occurred efficiently in nephrons of adult mice (Figure 1). Experimental γENaC-deficient mice become rapidly sick and develop a severe hyperkalemia (Figure 2). This phenotype thus mimics newborn mice harboring a constitutive deletion of the γENaC (Scnn1g) subunit.7 In inducible nephron-specific knockout mice, residual ENaC activities of αβ or as previously shown,16 βγ ENaC channels are not sufficient for survival. In our study, γENaC knockout mice show a more severe phenotype (increased body weight loss and severe hyperkalemia) (Table 1) when compared with α- and βENaC-deficient mice16,19, and independent of challenging diets. High plasma K+ levels may play a determinant role in cardiac arrest or flaccid paralysis,20,21 a phenotype we observed in mice with severe hyperkalemia (Figure 2B). Although hyperkalemia can be reversed in both α and βENaC-deficient mice treated with HNa+/LK+ diet or LK+ diet,16,19 this cannot be done in γENaC-deficient mice using the same protocol (Figure 3) or even when starting the LK+ treatment 1 day earlier (Figure 4). Hyperkalemia in patients with PHA-I is life-threatening, leading to cardiac arrhythmia and, ultimately, to cardiac arrest.22,23 Our data reveal a severe hyperkalemia accompanied by a decrease in food intake and a severe dehydration.

γENaC Knockout Mice Are Not Rescued by Sodium Supplement and Low Potassium Diet

Acute genetic deletion of γENaC subunit in the kidney is not compensated by increased Na+ reabsorption in proximal or distal nephrons through NKCC2, NCC, or the electroneutral sodium transporter.24 According to the in vitro subunit assembly data,2 we expected a less severe phenotype in γENaC knockout mice than in experimental αENaC-deficient mice.16 Switching to HNa+/LK+ diet (or LK+) keeps the γENaC-deficient mice severely hyperkalemic (Figures 3 and 4) whereas αENaC-deficient mice are rescued, despite a comparable initial loss of body weight.16 This led us to suggest that the γENaC subunit may exhibit a specific role in the channel activity. Interestingly, in αENaC-deficient mice, βENaC protein abundance was increased under standard diet,16 and might indicate a compensatory mechanism. Although no change in α and γENaC subunit expression is observed in βENaC-deficient mice,19 γENaC-deficient mice exhibited an overall decrease in βENaC protein abundance (Figure 7) and loss of apical βENaC subunit expression within the DCT2 (Figure 8), likely leading to an even lower ENaC activity, and thus to severe and irreversible hyperkalemia.

In wild-type mice, a LK+ diet is a strong stimulus to increase NCC activity.18 In our study and independently of the increase of the plasma aldosterone concentration (Table 1) and the concentration of both Na+ and K+ diets (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure 8), both the total and phosphorylated form of NCC of kidney extracts from γENaC knockout mice remained downregulated. We propose an aldosterone-independent and K+-dependent NCC regulation, where the observed decrease in pNCC is linked to the plasma K+ concentration.16 Using Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry, we exclude tubular atrophy as cause for the decrease in NCC because the expression of calbindin was not changed (Figures 1D and 8, data not shown). Our data thus clearly reveal a remarkable differential effect of Na+ and K+ diets on the phenotype and the survival of αENaC knockout and γENaC knockout mice.16

NCC Protein Abundance and Activity Is Coupled with Plasma K+ Concentrations

The development of severe hyperkalemia in γENaC-deficient mice could only be prevented by feeding a K+-deficient diet at the same time as doxycycline treatment (day 0) (Figure 9). Mice additionally treated with kayexalate regained their initial body weight (Supplemental Figures 6, 7, and 8). The exchange of K+ for Na+ and/or an activation of Na+ reabsorption in the colon, as previously observed,25 might further explain the significant reduction of fecal Na+ loss (Supplemental Figure 9). The Na+ balance shifted to an increased urinary Na+ loss that coincided with NCC downregulation (Supplemental Figure 9). In vitro results of Mistry et al.26 proposed that NCC and ENaC are bound to each other, and that the inhibition of one inhibits the activity of the other; more experiments are required to clarify the kind of interaction in ENaC models. The intracellular termini and the two transmembrane domains of γENaC subunit might be more important for channel surface expression and trafficking than those of the corresponding βENaC subunit.8 In this context, it is interesting to note that renal tubular cells lacking γENaC subunit expression exhibit no apical α and βENaC localization and thus no compensation, which may further contribute to the severe PHA-I phenotype (Supplemental Figure 10). Normalization of severe hyperkalemia by HNa+/LK+ diet was sufficient to normalize expression of both the total and phosphorylated form of NCC in αENaC knockout mice.16 Normokalemia is sufficient and necessary to normalize NCC expression and activity, despite absence of γENaC. This is in agreement with the study of Terker et al.,27 who proposed that changes in plasma K+ concentrations are the cause of NCC modulation. Contrary to the α and βENaC mouse models, the study of the γENaC-deficient mice unveiled that a preventive treatment with a K+-deficient diet restored NCC and SPAK activity and thus avoided the development of a severe PHA-I phenotype.

In summary, our data clearly show that (1) the γENaC-deficient mice develop a PHA-I phenotype with severe hyperkalemia and salt losing syndrome, as observed in the αENaC knockout model; (2) unlike the αENaC knockout model, severe hyperkalemia remains severe under HNa+/LK+ and LK+ diets with a drastic decrease of NCC expression and activity; (3) kayexalate-supplemented K+-deficient diet restored plasma Na+ and K+ levels within the physiologic range, although reduced NCC and pNCC abundance still result in salt wasting; and (4) preventing hyperkalemia through a K+-deficient diet completely normalizes NCC expression and activity in γENaC knockout mice. Our study demonstrates that γENaC is required for the modulation of K+ homeostasis and its absence leads to a rapid and severe hyperkalemia. These data further reveal a strong link between plasma K+ concentrations and NCC regulation, and thus unveils that the plasma K+ concentration is the predominant regulator of NCC expression and activity in the adult γENaC knockout model.

Concise Methods

Nephron-Specific Knockout of γENaC

Nephron-specific γENaC-deficient mice (Scnn1glox/lox;Pax8::rTA0/tg;TRE::LC-10/tg; γENaC knockout mice, experimental mice) and control mice (Scnn1glox/lox;TRE::LC-10/tg; Scnn1gLC1, Scnn1glox/lox;Pax8::rtTA0/tg; Scnn1gPax8, and Scnn1glox/lox) were obtained by interbreeding Scnn1glox/lox mice28 single-transgenic for Pax8::rTA0/tg or TRE::LC-10/tg.29 They were genotyped by PCR from ear biopsies (Pax8-rtTA_ST1: 5′-CCATGTCTAGACTGGACAAGA-3′, Pax8-rtTA_ST2: 5′-CTCCAGGCCACATATGATTAG-3′; LC-1 Cre3: 5′-TCGCTGCATTACCGGTCGATGC-3′; LC-1 Cre4: 5′-CCATGAGTGAACGAACCTGGTCG-3′).16 Recombination at the Scnn1g locus was determined by the following primers: 19as, 5′ CAT AGA CAC AGC CAT TGA AC 3′; 12as, 5′ TTG ATG GAG ACA GAG ACG G 3′; and 18s, GCC TGA TAA GAG AAG TCT G 3′. PCR was done according to standard conditions (35 cycles, 1 minute at 94°C, 56°C, and 72°C). For breeding, mice were kept under a 14 hour light/10 hour dark cycle. Animal maintenance and protocols were done according to Swiss guidelines and as accepted by the local authority (Service de la consommation et des affaires vétérinaires of the canton of Vaud, Switzerland).

At 3 weeks of age, mice were changed to a different light/dark cycle (12/12 hours). One week later (4-week-old mice), littermates (control and experimental) were provided for 2–3 days with doxycycline (2 mg/ml doxycycline hydrochloride; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and 2% sucrose in the drinking water (protocol A, Supplemental Figure 1A).

Analysis of Mice on Doxycycline Treatment

Body weight, water and food consumption, urine volume, feces output, and urinary electrolytes were determined and analyzed after doxycycline induction (at day 0). Body weight is presented as percentage of Δ body weight change with respect to the initial reference weight (at day 0). After 3 days, various metabolic values were determined (plasma aldosterone, osmolality, glucose, urea, creatinine, hematocrit values, and plasma electrolytes). Details of different diets are indicated (Supplemental Figure 1, A–E). High sodium (HNa+) and low potassium (LK+) protocols (protocol B): after doxycycline induction, control and experimental (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice were individually placed into metabolic cages (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy) and fed a standard diet (0.17% Na+ and 0.97% K+) for three consecutive days followed by a switch to a high sodium (3.5% Na+) and low potassium diet (K+-deficient [<0.1% K+] diet supplemented with 0.2% K+ in drinking water). Food was given as powder (ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH). LK+ protocols (protocol C): after two consecutive days under a standard diet, control and experimental (Scnn1gPax8/LC1) mice were fed with a LK+ diet (0.17% Na+; <0.1% K+ given as powder), supplemented with 0.2% K+ in drinking water (LK+ diet) up to one day. K+-deficient diet was supplemented with the K+ chelator kayexalate (poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate); Sigma Aldrich [protocol D]): 2 days before doxycycline induction, mice were fed with a K+-deficient diet (0.17% Na+; <0.1% K+ given as powder) and on doxycycline induction, control and experimental mice were treated with kayexalate mixed with the food (0.96 µl/d per gram of body weight) for up to 20 days. K+-deficient diet (protocol E): on doxycycline induction, control and experimental mice were fed a K+-deficient diet (0.17% Na+; <0.1% K+ given as powder) for up to 6 days. Changes in body weight, and consumption of water and food, as well as urine volume and feces output were regularly determined (6 hours: protocol B; 24 hours: protocols A, C, and D). For further analysis, organs (kidney, liver, and heart) and plasma samples were collected after mice were euthanized.

Metabolic Parameters

Urine was collected in metabolic cages and urinary Na+ and K+ concentrations were determined (flame photometer; Cole-Parmer Instruments) (protocol A, Supplemental Figure 1A). Na+ and K+ intakes were calculated from electrolyte concentration in the different diets (protocols A, B, D, E, and F). For LK+ diet (protocol C), K+ intake was calculated from K+ concentration in drinking water (0.2%). Twenty-four-hour fecal samples for Na+ and K+ concentration were collected at the end of protocol D (day 20). Briefly, the samples were dried at around 800°C for 8 hours, weighed, and resuspended overnight in 0.6% HCl. After centrifugation, an aliquot of supernatant was measured for Na+ and K+ concentration (flame photometer). Na+ and K+ balance were calculated as ratio between the quantity of Na+ or K+ output (in urine and feces), normalized by the quantity of Na+ intake at day 20. Na+ and K+ intake were depicted as percentage of control. Osmolality of serum and urine was evaluated using an Advanced 2020 Osmometer (Advanced Instruments). Body weight was used as reference for normalization of food consumption and water intake as well as urine and feces. RIA (Coat-A-Count RIA kit; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Ballerup, Denmark) was used for plasma aldosterone (protocols A and C, Supplemental Figure 1, A and C, Table 1). Mouse samples with values >1200 pg/ml were further diluted using a serum pool with a low aldosterone concentration (<50 pg/ml). The measurements of creatinine and glucose (clearance for creatinine is in microliters per minute) were performed at the Zurich Integrative Rodent Physiology platform (University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland). The plasma osmolality was determined from (2×[serum Na+])+(2×[serum K+])+[serum glucose]+[serum urea] (Table 2).30 The fractional excretion of Na+ and K+ was assessed as described.31

Protein was extracted from frozen tissue as described.32 The following antibodies were obtained and used as previously described33 (anti-α, β, γENaC, pT53-NCC, NCC) or obtained from Millipore (anti-pSPAK). Antibodies were diluted at a ratio of 1:500 (NCC, αENaC, pSPAK) or 1:1000 (βENaC, γENaC, pNCC (T53). Loading was controlled with actin (β-actin antibody; Sigma-Aldrich). The signal from SPAK was verified using kidney protein lysates of SPAK-deficient mice as negative control (C-; generously supplied by O. Staub).34,35

Immunofluorescence

Kidney cryosections (5-μm thick) were exposed overnight to primary antibodies against Cre (1:10,000),36 βENaC (1:40,000),37 γENaC (dilution 1:40,000),37 or CaBP D28k (1:10,000) (Swant, Marly, CH), followed by incubation with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies goat anti–rabbit-CY3 (1:1000) and goat anti–mouse-FITC (1:100) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). A fluorescence microscope (Leica DM6000 B; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) was used for photography and pictures were further processed (Leica Application Suite software) and then imported into Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA) and Powerpoint for image arrangement and labeling.

Statistical Analyses

Values are indicated as mean±SEM, and data were evaluated by unpaired two-tailed t test. Values expressed as a function of time were analyzed using multiple comparisons by two-way ANOVA (Bonferroni). Data in Figures 2, A, C, and D, 3, A and C–F, 4, A and C–F, and 9A, and Supplemental Figures 2–4, 6, and 7 were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (Bonferroni). P<0.05 was considered as significant; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Anne-Marie Mérillat for excellent photographic work, and to Oliver Staub for providing protein lysates from SPAK-deficient mice. E.B. and E.H. designed the study. E.B., C.S., M.P.M., and D.L.-C. carried out experiments. E.B., R.P., J.L., D.L.-C., R.K., B.C.R., and E.H. analyzed the data. E.B., C.S., and E.H. made the figures; E.B. and E.H. drafted and revised the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding was provided by Swiss National Science Foundation (FNRS 31003A_144198/1 and 31003A_163347), the Leducq Foundation, and European Cooperation in Science and Technology Action BM1301 Aldosterone and Mineralocorticoid Receptor.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017030345/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Canessa CM, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC: Epithelial sodium channel related to proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Nature 361: 467–470, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, et al.: Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature 367: 463–467, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanukoglu I, Hanukoglu A: Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) family: Phylogeny, structure-function, tissue distribution, and associated inherited diseases. Gene 579: 95–132, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boscardin E, Alijevic O, Hummler E, Frateschi S, Kellenberger S: The function and regulation of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) and the epithelial Na(+) channel (ENaC): IUPHAR Review 19. Br J Pharmacol 173: 2671–2701, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hummler E, Barker P, Gatzy J, Beermann F, Verdumo C, Schmidt A, et al.: Early death due to defective neonatal lung liquid clearance in alpha-ENaC-deficient mice. Nat Genet 12: 325–328, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald FJ, Yang B, Hrstka RF, Drummond HA, Tarr DE, McCray PB Jr, et al.: Disruption of the beta subunit of the epithelial Na+ channel in mice: Hyperkalemia and neonatal death associated with a pseudohypoaldosteronism phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 1727–1731, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker PM, Nguyen MS, Gatzy JT, Grubb B, Norman H, Hummler E, et al.: Role of gammaENaC subunit in lung liquid clearance and electrolyte balance in newborn mice. Insights into perinatal adaptation and pseudohypoaldosteronism. J Clin Invest 102: 1634–1640, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstas AA, Korbmacher C: The gamma-subunit of ENaC is more important for channel surface expression than the beta-subunit. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C447–C456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Kleyman TR: Gamma subunit second transmembrane domain contributes to epithelial sodium channel gating and amiloride block. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1585–F1592, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossier BC, Stutts MJ: Activation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by serine proteases. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 361–379, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ergonul Z, Frindt G, Palmer LG: Regulation of maturation and processing of ENaC subunits in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F683–F693, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frindt G, Gravotta D, Palmer LG: Regulation of ENaC trafficking in rat kidney. J Gen Physiol 147: 217–227, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zachar RM, Skjødt K, Marcussen N, Walter S, Toft A, Nielsen MR, et al.: The epithelial sodium channel γ-subunit is processed proteolytically in human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 95–106, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terker AS, Zhang C, Erspamer KJ, Gamba G, Yang CL, Ellison DH: Unique chloride-sensing properties of WNK4 permit the distal nephron to modulate potassium homeostasis. Kidney Int 89: 127–134, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czogalla J, Vohra T, Penton D, Kirschmann M, Craigie E, Loffing J: The mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) regulates ENaC but not NCC in mice with random MR deletion. Pflugers Arch 468: 849–858, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perrier R, Boscardin E, Malsure S, Sergi C, Maillard MP, Loffing J, et al.: Severe salt-losing syndrome and hyperkalemia induced by adult nephron-specific knockout of the epithelial sodium channel α-subunit. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2309–2318, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiga M, Rai T, Yang SS, Ohta A, Takizawa T, Sasaki S, et al.: Dietary salt regulates the phosphorylation of OSR1/SPAK kinases and the sodium chloride cotransporter through aldosterone. Kidney Int 74: 1403–1409, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade JB, Liu J, Coleman R, Grimm PR, Delpire E, Welling PA: SPAK-mediated NCC regulation in response to low-K+ diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308: F923–F931, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boscardin E, Perrier R, Sergi C, Maillard M, Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, et al.: Severe hyperkalemia is rescued by low-potassium diet in renal βENaC-deficient mice [published online ahead of print May 31, 2017]. Pflugers Arch doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1990-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evers S, Engelien A, Karsch V, Hund M: Secondary hyperkalaemic paralysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 64: 249–252, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg SK, Saxena S, Juneja D, Singh O, Kumar M, Mukherji JD: Hyperkalemia: A rare cause of acute flaccid quadriparesis. Indian J Crit Care Med 18: 46–48, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajpoot SK, Maggi C, Bhangoo A: Pseudohypoaldosteronism in a neonate presenting as life-threatening arrhythmia. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2014: 130077, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nobel YR, Lodish MB, Raygada M, Rivero JD, Faucz FR, Abraham SB, et al.: Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 due to novel variants of SCNN1B gene. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2016: 150104, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leviel F, Hübner CA, Houillier P, Morla L, El Moghrabi S, Brideau G, et al.: The Na+-dependent chloride-bicarbonate exchanger SLC4A8 mediates an electroneutral Na+ reabsorption process in the renal cortical collecting ducts of mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1627–1635, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malsure S, Wang Q, Charles RP, Sergi C, Perrier R, Christensen BM, et al.: Colon-specific deletion of epithelial sodium channel causes sodium loss and aldosterone resistance. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1453–1464, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mistry AC, Wynne BM, Yu L, Tomilin V, Yue Q, Zhou Y, et al.: The sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC) and epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) associate. Biochem J 473: 3237–3252, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terker AS, Yarbrough B, Ferdaus MZ, Lazelle RA, Erspamer KJ, Meermeier NP, et al.: Direct and indirect mineralocorticoid effects determine distal salt transport. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2436–2445, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mérillat AM, Charles RP, Porret A, Maillard M, Rossier B, Beermann F, et al.: Conditional gene targeting of the ENaC subunit genes Scnn1b and Scnn1g. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F249–F256, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traykova-Brauch M, Schönig K, Greiner O, Miloud T, Jauch A, Bode M, et al.: An efficient and versatile system for acute and chronic modulation of renal tubular function in transgenic mice. Nat Med 14: 979–984, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraut JA, Xing SX: Approach to the evaluation of a patient with an increased serum osmolal gap and high-anion-gap metabolic acidosis. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 480–484, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espinel CH: The FENa test. Use in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. JAMA 236: 579–581, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arroyo JP, Lagnaz D, Ronzaud C, Vázquez N, Ko BS, Moddes L, et al.: Nedd4-2 modulates renal Na+-Cl- cotransporter via the aldosterone-SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1707–1719, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen MV, Grossmann S, Roesinger M, Gresko N, Todkar AP, Barmettler G, et al.: Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney Int 83: 811–824, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delpire E, Gagnon KB: SPAK and OSR1: STE20 kinases involved in the regulation of ion homoeostasis and volume control in mammalian cells. Biochem J 409: 321–331, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick JA, Mutig K, Nelson JH, Saritas T, Hoorn EJ, Yang CL, et al. : A SPAK isoform switch modulates renal salt transport and blood pressure. Cell Metab 14: 352–364, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kellendonk C, Tronche F, Casanova E, Anlag K, Opherk C, Schütz G: Inducible site-specific recombination in the brain. J Mol Biol 285: 175–182, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner CA, Loffing-Cueni D, Yan Q, Schulz N, Fakitsas P, Carrel M, et al.: Mouse model of type II Bartter’s syndrome. II. Altered expression of renal sodium- and water-transporting proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1373–F1380, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.