Abstract

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is the most common infectious cause of blindness and bacterial sexually transmitted infection worldwide. Ct strain-specific differences in clinical trachoma suggest that genetic polymorphisms in Ct may contribute to the observed variability in severity of clinical disease.

Methods

Using Ct whole genome sequences obtained directly from conjunctival swabs, we studied Ct genomic diversity and associations between Ct genetic polymorphisms with ocular localization and disease severity in a treatment-naïve trachoma-endemic population in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa.

Results

All Ct sequences fall within the T2 ocular clade phylogenetically. This is consistent with the presence of the characteristic deletion in trpA resulting in a truncated non-functional protein and the ocular tyrosine repeat regions present in tarP associated with ocular tissue localization. We have identified 21 Ct non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with ocular localization, including SNPs within pmpD (odds ratio, OR = 4.07, p* = 0.001) and tarP (OR = 0.34, p* = 0.009). Eight synonymous SNPs associated with disease severity were found in yjfH (rlmB) (OR = 0.13, p* = 0.037), CTA0273 (OR = 0.12, p* = 0.027), trmD (OR = 0.12, p* = 0.032), CTA0744 (OR = 0.12, p* = 0.041), glgA (OR = 0.10, p* = 0.026), alaS (OR = 0.10, p* = 0.032), pmpE (OR = 0.08, p* = 0.001) and the intergenic region CTA0744–CTA0745 (OR = 0.13, p* = 0.043).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the extent of genomic diversity within a naturally circulating population of ocular Ct and is the first to describe novel genomic associations with disease severity. These findings direct investigation of host-pathogen interactions that may be important in ocular Ct pathogenesis and disease transmission.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13073-018-0521-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Trachoma, Disease severity, Genome-wide association analysis, Single nucleotide polymorphisms, Pathogen genomic diversity

Background

The obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is the leading infectious cause of blindness (trachoma) and the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection [1, 2].

Ct strains are differentiated into biovars based on pathobiological characteristics and serovars based on serological reactivity for the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) encoded by ompA [3]. Serovars largely differentiate biological groups associated with trachoma (A–C), sexually transmitted disease (D–K) and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) (L1–L3). Despite diverse biological phenotypes, Ct strains share near complete genomic synteny and gene content [4], suggesting that minor genetic changes influence pathogen-host and tissue-specific infection characteristics [5–8]. All published African ocular Ct genomes are situated on the ocular branch within the T2 clade of non-LGV urogenital isolates [4]. Currently there are only 31 published ocular Ct genome sequences [4, 9–12].

The pathogenesis of chlamydial infection begins with epithelial inflammation and may progress to chronic immunofibrogenic processes leading to blindness and infertility, though many Ct infections do not result in sequelae [13, 14]. Strain-specific differences related to clinical presentation have been investigated in trachoma [8, 15, 16]. These studies examined a small number of ocular Ct isolates from the major trachoma serotypes and found a small subset of genes in addition to ompA that were associated with differences in in vitro growth rate, burst size, plaque morphology, interferon gamma –(IFNγ) sensitivity and, most importantly, intensity of infection and clinical disease severity in non-human primates (NHPs), suggesting that genetic polymorphisms in Ct may contribute to the observed variability in severity of trachoma in endemic communities [8].

The obligate intracellular development of Ct has presented significant technical barriers to basic research into chlamydial biology. Only recently has genetic manipulation of the chlamydial plasmid been possible, allowing in vitro transformation and modification studies, though this remains technically challenging, necessitating alternative approaches [17, 18].

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) has recently been used to identify regions of likely recombination in recent clinical isolates, demonstrating that WGS analysis may be an effective approach for the discovery of loci associated with clinical presentation [6]. Additionally, a number of putative virulence factors have been identified through WGS analysis and subsequent in vitro and animal studies [5, 19–30]. However, there are currently no published population-based studies of Ct using WGS with corresponding detailed clinical data, making it difficult to relate genetic changes to functional relevance and virulence factors in vivo.

There is an increasing pool of Ct genomic data, largely from archived samples following cell culture and more recently directly from clinical samples [31]. WGS data obtained directly from clinical samples can be preferable to using WGS data obtained from cell-cultured Ct, since repeated passage of Ct results in mutations that are not observed in vivo [32–34].

Ct bacterial load is associated with disease severity, particularly conjunctival inflammation, in active (infective) trachoma [35]. Conjunctival inflammation has previously been shown to be a marker of severe disease and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of scarring trachoma [36–38]. In this study we used principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensions of clinical grade of inflammation (defined using the P score from the follicles, papillary hypertrophy, conjunctival scarring (FPC) trachoma grading system [39]) and Ct bacterial load to a single metric to define an in vivo conjunctival phenotype in active (infective) trachoma. PCA is a recognized dimension reduction technique used to combine multiple correlated traits into their uncorrelated principal components (PCs) [40–42], allowing us to examine the relationship between Ct genotype and disease severity. These data from the trachoma-endemic region of the Bijagós Archipelago of Guinea-Bissau currently represent the largest collection of ocular Ct sequences from a single population and provide a unique opportunity to gain insight into ocular Ct pathogenesis in humans.

Methods

Survey, clinical examination and sample collection

Survey, clinical examination and sample collection methods have been described previously [43, 44]. Briefly, we conducted a cross-sectional population-based survey in trachoma-endemic communities on the Bijagós Archipelago of Guinea-Bissau. The upper tarsal conjunctivae of each consenting participant were examined, digital photographs were taken, a clinical trachoma grade was assigned and two sequential conjunctival swabs were obtained from the left upper tarsal conjunctiva of each individual using a standardized method [43]. DNA was extracted and Ct omcB (genomic) copies/swab quantified from the second conjunctival swab using droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) [44, 45].

We used the modified FPC grading system for trachoma [39]. The modified FPC system allows detailed scoring of the conjunctiva for the presence of follicles (F score), papillary hypertrophy (conjunctival inflammation) (P score) and conjunctival scarring (C score), assigning a grade of 0–3 for each parameter. A single validated grader conducted the examinations, and these were verified by an expert grader (masked to the field grades and ddPCR results) using the digital photographs. Grader concordance was measured using Cohen’s kappa, where a kappa > 0.9 was used as the threshold to indicate good agreement.

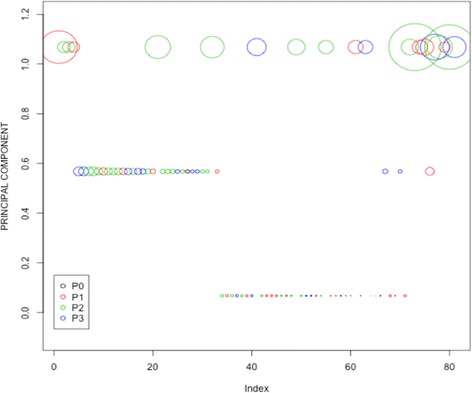

Conjunctival inflammation (P score) is known to have a strong association with Ct bacterial load in this and other populations [35, 46–49]. For this study we used PCA to combine the presence of inflammation (defined by the P score using the FPC trachoma grading system [39]) with Ct bacterial load (defined by tertile cut-offs illustrated in Additional file 1: Figure S1) [50]. The conjunctival disease phenotype is a dimension reduction of these two variables, defining what we observed in the conjunctiva at the time of sampling (Fig. 1). Dimension reduction using PCA to define complex disease phenotypes in genome-wide association studies (GWASs) is well recognized, as it allows multiple traits to be included to capture a more complex phenotype and accounts for correlation between traits. This approach therefore may reveal novel loci or pathways that would not be evident in a single-trait GWAS, where the full extent of genetic variation cannot be captured [40].

Fig. 1.

Composite in vivo conjunctival disease severity phenotype in ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection. A composite in vivo phenotype was derived using principal component analysis (PCA) for dimension reduction of two phenotypic traits: a disease severity score (using the P score value) and C. trachomatis load (where C. trachomatis load was log transformed and cut-offs determined from the resulting density plot (see Additional file 1: Figure S1)). Each circle represents an individual infection (represented on the x-axis (Index), n = 81). Circle size reflects C. trachomatis load and circle colour reflects inflammatory P score (P0–P3) defined using the modified FPC (follicles, papillary hypertrophy, conjunctival scarring) grading system for trachoma [39]

Preparation of chlamydial DNA from cell culture

For eight specimens, WGS data were obtained following Ct isolation in cell culture (from the first conjunctival swab) as a preliminary exploration of Ct genomic diversity in this population. Briefly, samples were isolated in McCoy cell cultures by removing 100 μl eluate from the original swab with direct inoculation onto a glass coverslip within a bijou containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). The inocula were centrifuged onto cell cultures at 1800 rpm for 30 min. Following centrifugation the cell culture supernatant was removed and cycloheximide-containing DMEM was added to infected cells which were then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3 days. Viable Ct elementary bodies (EBs) were observed by phase contrast microscopy. Cells were harvested and further passaged every 3 days until all isolates reached a multiplicity of infection between 50 and 90% in 2xT25 flasks. Each isolate was prepared and the EBs purified as described previously [51]. DNA was extracted from the purified EBs using the Promega Wizard Genomic Purification kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol [52].

Pre-sequencing target enrichment

For the remaining specimens (n = 118), WGS data were obtained directly from clinical samples. DNA baits spanning the length of the Ct genome were compiled by SureDesign and synthesized by SureSelectXT (Agilent Technologies, UK). The total DNA extracted from clinical samples was quantified and carrier human genomic DNA added to obtain a total of 3 μg input for library preparation. DNA was sheared using a Covaris E210 acoustic focusing unit [31]. End-repair, non-templated addition of 3′-A adapter ligation, hybridization, enrichment PCR and all post- reaction clean-up steps were performed according to the SureSelectXT Illumina Paired-End Sequencing Library protocol (v1.4.1 Sept 2012). All recommended quality control measures were performed between steps.

Whole genome sequencing and sequence quality filtering

DNA was sequenced at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute using Illumina paired-end technology (Illumina GAII or HiSeq 2000). All 126 sequences passed standard FastQC quality control criteria [53]. Sequences were aligned to the most closely related reference genome, Chlamydia trachomatis A/HAR-13 (GenBank accession umber NC_007429.1 and plasmid GenBank accession number NC_007430.1), using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [54]. SAMtools/BCFtools (SAMtools v1.3.1) [55] and the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) [56] were used to call SNPs. We used standard GATK SNP calling algorithms, where > 10× depth of coverage is routinely used as the threshold value [56, 57]. This has been shown to be adequate for SNP calling in this context [57–59].

Variants were selected as the intersection data set between those obtained using both SNP callers and SNPs were further quality-filtered. SNP alleles were called using an alternative coverage-based approach where a missing call was assigned to a site if the total coverage was less than 20× depth or where one of the four nucleotides accounted for at least 80% total coverage [60]. There was a clear relationship between the mean depth of coverage and the proportion of missing calls, based on which we retained sequences with greater than 10× mean depth of coverage over the whole genome (81 sequences retained).

Heterozygous calls were removed, and SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of less than 25% were removed. Samples with greater than 25% genome-wide missing data and 30% missing data per SNP were excluded from the analysis (n = 10, 71 sequences retained). All SNP positions with a MAF greater than 20% were identified using BCFtools v0.1.19 (https://samtools.github.io/bcftools/). Sequences were excluded from the final GWAS if more than 300 such positions were found using methods described by Hadfield et al. [61]. The quality assessment and filtering process is shown in Fig. 2. Details of the WGS data are provided in Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Fig. 2.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) quality filtering processes and threshold criteria for inclusion in analyses. Ct DNA detected using droplet digital PCR [45]. WGS data were obtained using SureSelect target enrichment [31] (or chlamydial cell culture) and Illumina paired-end sequencing. FastQC [53] was used to assess basic WGS quality. SNP alleles were called against reference strain Ct A/HAR-13 using an alternative coverage-based approach where a missing call was assigned to a site if the total coverage was less than 20× depth or where one of the four nucleotides accounted for at least 80% total coverage [60]. There was a clear relationship between the mean depth of coverage and genome-wide proportion of missing calls; therefore, only sequences with greater than 10× mean depth of coverage over the whole genome were retained using the GATK Best Practices threshold [56, 57]. Heterozygous calls were removed and SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of less than 25% were removed. Samples with greater than 25% genome-wide missing data and 30% missing data per SNP were excluded from the analysis. WGS sequence quality is shown in detail in Additional file 12: Figure S12. *n = 157 including the 71 Bijagós sequences in addition to 48 Rombo District sequences and 38 reference sequences

Phylogenetic reconstruction

Samples were mapped to the ocular reference strain Ct A/HAR-13 and SNPs were called as described above. Phylogenies were computed using RAxML v7.8.2 [62] from a variable sites alignment using a generalized time-reversible (GTR) + gamma model and are midpoint rooted. Recombination is known to occur in Ct [4, 6] and can be problematic in constructing phylogeny. We applied three compatibility-based recombination detection methods to detect regions of recombination using PhiPack [63]: the pairwise homoplasy index (Phi), the maximum χ2 and the neighbour similarity score (NSS) across the genome alignment. We also examined the confidence in the phylogenetic tree by computing RAxML site-based likelihood scores [62]. Phylogenetic trees were examined adjusting for recombination using the methods described above.

Additionally, sequence data for the tryptophan operon (CTA0182 and CTA0184–CTA0186), tarP (CTA0498), nine polymorphic membrane proteins (CTA0447–CTA0449, CTA0884, CTA0949–CTA0952 and CTA0954) and ompA (CTA0742) were extracted from the 81 ocular Ct sequences from Guinea-Bissau retained after quality control filtering described above, 48 ocular sequences originating from a study conducted in Kahe village, Rombo District, Tanzania [64] and 38 publicly available reference sequences. Phylogenies were constructed as described above.

Polymorphisms, insertions and deletions (indels) and truncations for the tryptophan operon were manually determined from aligned sequences using SeaView [65]. Tyrosine repeat regions and actin-binding domains in tarP were found using RADAR [66] and Pfam [67] respectively.

Pairwise diversity

A comparison was made between the two population-based Ct sequence data sets from the Bijagós (Guinea-Bissau) and Rombo (Tanzania) sequences whereby short read data from the 81 Bijagós sequences and 48 Rombo sequences were mapped against Ct A/HAR-13 using SAMtools. Within-population pairwise nucleotide diversity was calculated using the formula:

where n is the number of sequences, x is the frequency of sequences i and j and πij is the number of nucleotide differences per site between sequences i and j [68]. The frequency of sequences was considered uniform within the populations, and sites with missing calls were excluded on a per-sequence basis.

Genome-wide association analyses

To investigate the association between Ct polymorphisms with ocular localization and clinical disease severity, we used permutation-based logistic regression methods, which are powerful and well-recognized tools in GWAS, allowing for adjustment for population structure, age and gender in the model and accounting for multiple testing [69–72].

We used permutation analyses of 100,024 phenotypic re-samplings, where the distribution of the p value was approximated by simulating data sets through randomization under the null hypothesis of no association between phenotype and genotype. Genome-wide significance was determined as p* ≤ 0.05, where p* was defined as the fraction of re-sampled (simulated) data that returned p values that were less than or equal to the p values observed in the data [50]. All analyses were conducted using the R statistical package v3.0.2 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/) using MASS, GLM and lsr. All R script used for these analyses is contained within Additional file 3: Figure S3 and is released as a CC-BY open resource (CC-BY-SA 3.0).

Ocular localization

Tissue localization is defined as the localization (or presence) of a detectable Ct infection to either the conjunctival epithelium or the urogenital tract. Short read data from the 129 clinical ocular sequences from the pairwise diversity analysis and 38 publicly available reference sequences from ocular (n = 8), urogenital (n = 17) and rectal (n = 13) sites were mapped against Ct A/HAR-13 using SAMtools. Only polymorphic sites were retained, and SNPs were filtered as described above. The final analysis includes 1007 SNPs from 157 sequences, a phylogeny of which is contained within Additional file 4: Figure S4. A permutation-based generalized linear regression model was used to test the association between collection site (ocular or urogenital tissue localization) and polymorphic sites. For each SNP the standard error for the t statistic was estimated from the model and used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals. A χ2 test was used to determine the association between ocular localization-associated SNPs and both gene expression stage and predicted localization of the encoded proteins. The developmental cycle expression stage for each transcript was based on data and groupings from Belland et al. [73]. Predicted localization of expressed proteins was defined using the consensus from three predictions using CELLO [74], PSORTb [75] and LocTree3 [76].

Clinical disease severity

A permutation-based ordinal logistic regression model was used to test the association between the disease severity score (using the in vivo conjunctival phenotype defined previously) and polymorphic sites. The final analysis includes 129 SNPs from 71 sequences derived as described in Fig. 2. For each SNP the standard error for the t statistic was estimated from the model and used to calculate the ORs and 95% confidence intervals. Individuals’ age and gender were included as a covariate to the regression analysis.

We investigated the effect of population structure on the results of the GWAS analysis using PCA [77]. The first three PCs captured the majority of structural variation, but including them in the model had no effect; therefore, they were not included in the final model.

We corrected for genomic inflation if the occurrence of a polymorphism in the population was more than 90% or if there was a MAF of 3%.

Results

Conjunctival swabs collected during a cross-sectional population-based trachoma survey on the Bijagós Archipelago yielded 220 ocular Ct infections detected by Ct plasmid-based ddPCR. Of the 220 Ct infections detected, 184 were quantifiable using Ct genome-based ddPCR.

We obtained WGS data from 126/220 samples using cell culture (n = 8) or direct sequencing from swabs with SureSelectXT target enrichment (n = 118), representing the largest cross-sectional collection of ocular Ct WGS. Eighty-one of these sequences were subsequently included in the phylogenetic and diversity analyses and 71 were retained in the final genome-wide association (tissue localization (derived from the anatomical site of sample collection) and disease severity) analyses. The quality filtering process is illustrated in Fig. 2 and detailed in Methods.

A total of 1034 unique SNP sites were identified within the 126 Bijagós Ct genomes relative to the reference strain Ct A/HAR-13. Following application of further threshold criteria based on MAF and genome-wide missing data thresholds, we retained only high-quality genomic data in the final association analyses (129 SNPs from 71 sequences). There were no significant differences between the 71 retained and the 55 excluded sequences with respect to demographic characteristics, bacterial load, disease severity scores or geographical location (Table 1). Clinical and demographic details of the survey participants in whom we did not identify Ct infection have been published previously [43]. Of the ten SNPs initially identified within the Ct plasmid sequences, none fulfilled the quality filtering criteria, and they were not retained for the genome-wide association analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis sequences included in the disease severity association analysis

| Sequence ID | Sample ID | Average depth of coverage | % Missing readsa | Gender | Age (years) | Island code | Village code | Ocular loadb | P scorec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11152_3_1 | 14,344 | 764 | 0.35% | M | 4 | 002 | 33 | 202,632 | 1 |

| 11152_3_10 | 17,347 | 121 | 0.21% | M | 5 | 001 | 17 | 69,093 | 2 |

| 11152_3_11 | 4422 | 19 | 19.95% | F | 2 | 001 | 12 | 68,782 | 2 |

| 11152_3_12 | 11,231 | 68 | 2.24% | M | 0 | 003 | 43 | 64,036 | 1 |

| 11152_3_13 | 15,631 | 21 | 14.93% | F | 2 | 002 | 33 | 55,749 | 3 |

| 11152_3_14 | 6105 | 1664 | 0.05% | F | 1 | 001 | 14 | 55,202 | 3 |

| 11152_3_15 | 12,628 | 191 | 0.10% | F | 12 | 002 | 29 | 54,651 | 2 |

| 11152_3_16 | 7524 | 2065 | 0.14% | M | 10 | 002 | 35 | 54,539 | 2 |

| 11152_3_17 | 5016 | 61 | 0.44% | F | 1 | 001 | 15 | 46,510 | 2 |

| 11152_3_18 | 1485 | 44 | 1.21% | F | 4 | 002 | 27 | 45,929 | 1 |

| 11152_3_19 | 15,554 | 825 | 0.06% | F | 1 | 002 | 33 | 44,052 | 2 |

| 11152_3_20 | 6094 | 3070 | 0.00% | F | 3 | 001 | 14 | 42,917 | 2 |

| 11152_3_22 | 5082 | 51 | 0.81% | M | 6 | 001 | 15 | 42,427 | 1 |

| 11152_3_23 | 12,969 | 3643 | 1.81% | F | 3 | 002 | 29 | 41,308 | 3 |

| 11152_3_25 | 8140 | 246 | 0.36% | M | 13 | 001 | 20 | 39,816 | 2 |

| 11152_3_26 | 6083 | 2746 | 0.00% | F | 23 | 001 | 14 | 38,771 | 3 |

| 11152_3_27 | 16,621 | 1664 | 0.00% | M | 3 | 002 | 37 | 33,514 | 3 |

| 11152_3_28 | 16,852 | 143 | 0.16% | M | 5 | 002 | 38 | 31,228 | 2 |

| 11152_3_29 | 16,588 | 53 | 0.81% | M | 6 | 002 | 37 | 29,991 | 1 |

| 11152_3_3 | 4180 | 51 | 0.92% | M | 2 | 001 | 12 | 140,693 | 2 |

| 11152_3_30 | 7612 | 107 | 0.44% | F | 3 | 002 | 35 | 28,528 | 2 |

| 11152_3_31 | 6985 | 177 | 0.10% | M | 6 | 001 | 17 | 27,924 | 2 |

| 11152_3_32 | 4411 | 24 | 9.68% | F | 1 | 001 | 12 | 27,584 | 2 |

| 11152_3_33 | 4257 | 381 | 0.06% | M | 0 | 001 | 12 | 24,033 | 3 |

| 11152_3_34 | 4400 | 48 | 0.98% | M | 6 | 001 | 12 | 23,435 | 2 |

| 11152_3_35 | 15,180 | 571 | 0.35% | F | 7 | 002 | 33 | 23,254 | 0 |

| 11152_3_36 | 13,596 | 496 | 0.06% | M | 18 | 002 | 23 | 22,098 | 3 |

| 11152_3_37 | 1672 | 20 | 18.42% | M | 6 | 002 | 25 | 21,630 | 3 |

| 11152_3_38 | 5181 | 81 | 0.32% | M | 4 | 001 | 15 | 21,339 | 2 |

| 11152_3_39 | 15,532 | 243 | 0.08% | F | 25 | 002 | 33 | 21,174 | 2 |

| 11152_3_4 | 8074 | 150 | 0.13% | M | 4 | 001 | 18 | 131,175 | 2 |

| 11152_3_40 | 16,984 | 145 | 0.19% | M | 4 | 002 | 21 | 20,113 | 1 |

| 11152_3_41 | 1881 | 37 | 2.71% | F | 1 | 002 | 32 | 15,963 | 2 |

| 11152_3_42 | 10,032 | 101 | 0.16% | M | 2 | 003 | 42 | 15,706 | 1 |

| 11152_3_43 | 8492 | 70 | 2.60% | M | 1 | 004 | 45 | 15,582 | 2 |

| 11152_3_44 | 13,585 | 31 | 4.97% | M | 23 | 002 | 23 | 15,417 | 3 |

| 11152_3_48 | 7535 | 61 | 0.84% | M | 18 | 002 | 35 | 13,439 | 3 |

| 11152_3_5 | 7095 | 235 | 0.44% | F | 4 | 001 | 17 | 105,453 | 3 |

| 11152_3_50 | 6028 | 46 | 1.24% | F | 4 | 001 | 14 | 12,961 | 2 |

| 11152_3_52 | 10,021 | 20 | 16.15% | F | 6 | 003 | 42 | 11,840 | 1 |

| 11152_3_55 | 12,650 | 59 | 0.54% | M | 6 | 002 | 29 | 9001 | 2 |

| 11152_3_57 | 8965 | 21 | 16.60% | M | 27 | 003 | 43 | 7336 | 1 |

| 11152_3_58 | 5104 | 33 | 3.68% | M | 2 | 001 | 15 | 7203 | 2 |

| 11152_3_6 | 16,599 | 52 | 0.73% | M | 9 | 002 | 37 | 96,333 | 2 |

| 11152_3_62 | 7062 | 22 | 13.41% | F | 4 | 001 | 17 | 6986 | 3 |

| 11152_3_63 | 8778 | 17 | 25.47% | F | 11 | 004 | 46 | 6760 | 3 |

| 11152_3_66 | 1892 | 45 | 1.25% | F | 2 | 002 | 32 | 6374 | 1 |

| 11152_3_7 | 10,747 | 581 | 1.82% | F | 3 | 003 | 44 | 82,916 | 2 |

| 11152_3_70 | 13,189 | 25 | 8.87% | F | 3 | 002 | 24 | 4703 | 1 |

| 11152_3_74 | 15,499 | 24 | 10.49% | M | 5 | 002 | 33 | 4226 | 1 |

| 11152_3_76 | 726 | 417 | 0.06% | F | 3 | 002 | 26 | 3753 | 0 |

| 11152_3_77 | 7579 | 105 | 0.52% | F | 5 | 002 | 35 | 3468 | 1 |

| 11152_3_78 | 12,089 | 16 | 27.78% | F | 13 | 002 | 47 | 3203 | 2 |

| 11152_3_8 | 6996 | 38 | 2.03% | M | 3 | 001 | 17 | 82,614 | 1 |

| 11152_3_88 | 748 | 163 | 0.10% | F | 2 | 002 | 26 | 1636 | 0 |

| 11152_3_9 | 10,967 | 20 | 17.52% | F | 2 | 003 | 44 | 81,124 | 3 |

| 11152_3_92 | 1463 | 73 | 0.30% | F | 42 | 002 | 27 | 1273 | 2 |

| 13108_1_14 | 24,519 | 51 | 2.81% | M | 2 | 004 | 45 | 29,040 | 3 |

| 13108_1_15 | 6941 | 33 | 1.81% | M | 36 | 001 | 17 | 13,155 | 1 |

| 13108_1_7 | 25,124 | 27 | 5.27% | M | 4 | 002 | 22 | 21,750 | 3 |

| 13108_1_9 | 22,154 | 18 | 20.56% | F | 5 | 003 | 43 | 14,349 | 1 |

| 8422_8_49 | 2353 | 39 | 5.70% | M | 11 | 002 | 35 | 96,889 | 2 |

| 8422_8_50 | 2366 | 82 | 1.08% | M | 1 | 002 | 35 | 289,778 | 2 |

| 9471_4_86 | 12,980 | 287 | 1.90% | M | 4 | 002 | 29 | 85,456 | 1 |

| 9471_4_87 | 15,367 | 215 | 0.46% | M | 1 | 002 | 33 | 99,064 | 1 |

| 9471_4_88 | 15,543 | 192 | 0.11% | F | 23 | 002 | 33 | 49,125 | 1 |

| 9471_4_89 | 1870 | 119 | 0.14% | M | 3 | 002 | 32 | 158,548 | 3 |

| 9471_4_90 | 2145 | 111 | 0.11% | M | 15 | 002 | 32 | 140,297 | 2 |

| 9471_4_91 | 4158 | 94 | 0.14% | M | 4 | 001 | 12 | 63,654 | 1 |

| 9471_4_92 | 4169 | 85 | 0.13% | F | 3 | 001 | 12 | 274,835 | 2 |

| 9471_4_93 | 7590 | 242 | 0.51% | F | 1 | 002 | 35 | 128,025 | 3 |

Sequences (n = 55) were excluded from the association analysis if there was (1) < 10× coverage, (2)a > 25% missing reads genome-wide and (3) > 25% missing (N) calls at the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) locus. Coverage and missing data were correlated and resulted in exclusion of the same samples irrespective of criteria chosen. Seventy-one sequences were retained in the final disease severity analysis. bOcular C. trachomatis load = omcB (C. trachomatis genome) copies per conjunctival swab measured using droplet digital PCR. cP score = conjunctival inflammation score (0–3) using the modified FPC (follicles, papillary hypertrophy, conjunctival scarring) grading system for trachoma [39]

Ocular C. trachomatis phylogeny and diversity

For the phylogeny and diversity analyses, 81 Bijagós Ct sequences were included on the basis of the quality filtering criteria described in detail in Fig. 2. SNP-based phylogenetic trees constructed using all 1034 SNPs for sequences above 10× coverage (n = 81), with 54 published Ct reference genomes, are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Maximum likelihood reconstruction of whole genome phylogeny of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis sequences from the Bijagós Archipelago (Guinea-Bissau). Maximum likelihood reconstruction of the whole genome phylogeny of 81 Ct sequences from the Bijagós Islands and 54 Ct reference strains. Bijagós Ct sequences (n = 81) were mapped to Ct A/HAR-13 using SAMtools [55]. SNPs were called as described by Harris et al. [4]. Phylogenies were computed with RAxML [62] from a variable sites alignment using a GTR + gamma model and are midpoint rooted. The scale bar indicates evolutionary distance. Bijagós Ct sequences in this study are coloured black, and reference strains are coloured by tissue localization (red = Ocular, green = Urogenital, blue = LGV). Branches are supported by > 90% of 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branches supported by 80–90% (orange) and < 80% (brown) bootstrap replicates are indicated

The Bijagós sequences are situated within the T2 ocular monophyletic lineage with all other ocular Ct sequences [59] except those described by Andersson et al. [10]. However, our population-based collection of ocular Ct sequences has much greater diversity at whole genome resolution than previously demonstrated in African trachoma isolates [4, 8]. We used a pairwise diversity (π) metric to compare two populations of ocular Ct from regions with similar trachoma endemicity and studies with similar design, sample size and available epidemiological metadata. These data show much greater genomic diversity in the Bijagós ocular Ct sequences (π = 0.07167) compared to the Tanzanian (Rombo) ocular Ct sequences (π = 0.00047).

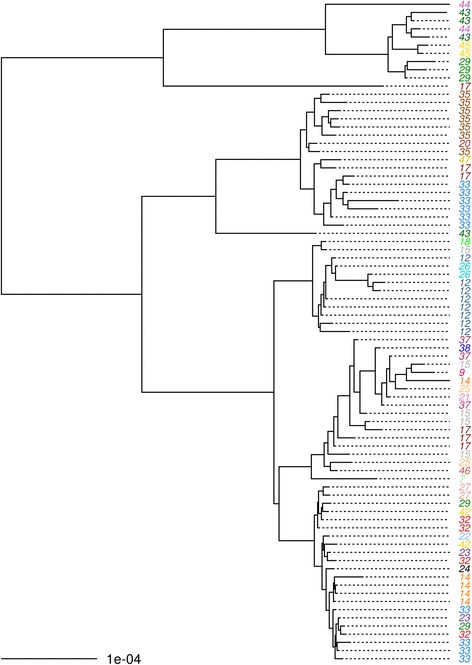

By ompA genotyping, 73 of the Bijagós sequences are genotype A and 8 are genotype B, supporting their classical ocular nature (Additional file 5: Figure S5). The high resolution of WGS data obtained directly from clinical samples captures diversity that may be useful in strain classification, particularly as we found some evidence of clustering at village level, although the very small number of sequences per village means that it is not possible to provide accurate estimates of clustering in this study (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing clustering of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis sequence types by village. RAxML maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction including all ocular Ct sequences retained in the final disease severity association analysis after quality filtering (n = 71). Ocular Ct sequences are labelled by village (villages numbered and coloured), midpoint-rooted and mapped to reference Ct A/HAR-13. Branches are supported by > 90% of 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branches supported by 80–90% (orange) and < 80% (brown) bootstrap replicates are indicated

Homoplasic SNPs and regions affected by recombination are shown in Additional file 6: Figure S6a. Removal of these regions of recombination identified using the pairwise homoplasy index had no effect on phylogenetic relationships. Additionally, a site-wise log likelihood plot demonstrated that there was no clear genomic region where there was significant lack of confidence in the tree construction due to recombination (Additional file 6: Figure S6b). Whether regions containing recombination were included or excluded, tree topology remained essentially identical, indicating that branching order is not affected by the removal of these regions.

Genome-wide analysis of C. trachomatis localization

Candidate genes thought to be involved in or indicative of ocular localization or preference were examined to further characterize this population of ocular Ct. Polymorphisms and truncations in the tryptophan operon have previously been implicated in the inability of ocular Ct to infect and survive in the genital tract [5]. All sequences contained mutations in trpA resulting in truncation. The majority (80/81) were truncated at the previously characterized deletion at position 533 [5]. Polymorphisms in trpB and trpR were less common (Additional file 7: Figure S7).

The variable domain structure of the translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein (tarP) has also been implicated in tropism [78]. Ocular strains possess more actin-binding domains (three or four) and fewer tyrosine repeat regions (between one and three). Urogenital strain tarP sequences have low copy numbers of both, and LGV strain sequences have additional tyrosine repeat regions. In this study, all sequences contain the expected three tyrosine repeat regions and three or four actin-binding domains (Additional file 7: Figure S7).

The nine virulence-associated polymorphic membrane proteins (Pmp) are variably related to tissue preference, with all encoding genes except pmpA, pmpD and pmpE clustering by tissue location [20]. In this population all phylogenies of the six tropism-clustering pmps show that all sequences cluster with other ocular sequences (Additional file 8: Figure S8).

Permutation-based re-sampling methods, commonly used in GWAS analyses, were used to account for multiple comparisons [69–72]. We tested 1007 SNPs in 157 Ct sequences (Fig. 2) for association with ocular localization (defined by anatomical site of sample collection), comparing 127 ocular, 17 urogenital and 13 LGV strains (Fig. 5a). One hundred and five SNPs were significantly associated with ocular localization (p* < 0.05), of which 21 were non-synonymous (details in Table 2a and Additional file 9: Figure S9). These were within a number of genes known to be polymorphic, genes previously identified as tropism-associated (CTA0156, CTA0498/tarP and CTA0743/pbpB) and virulence factors (CTA0498/tarP and CTA0884/pmpD). Four genes contained multiple non-synonymous SNPs (CTA_0733/karG, CTA_089/5sucD, CTA_0087 and CTA_0145/oppA_1), and ten genes contained multiple synonymous SNPs. Of the genes containing multiple synonymous SNPs, five contained more than three SNPs (CTA_0739/tsf, CTA_0733/karG, CTA_0156, CTA_0154 and CTA_0153). No predicted protein localization was over-represented in the ocular localization-related SNPs (p = 0.6174); however, early and very-late expressed genes were over-represented (p = 0.0197).

Fig. 5.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms on the Chlamydia trachomatis genome associated with (a) ocular localization and (b) disease severity at genome-wide significance. a Ocular localization-associated SNPs across the C. trachomatis genome. There were 1007 SNPs identified in coding and non-coding regions and included in permutation-based linear regression models in the Ct genome-wide association analysis. The threshold for genome-wide significance is indicated by the dashed line (p* < 0.05). The y-axis shows the –log10 p value. A –log10 p value of 1.3 is equivalent to a permuted p value of 0.05 (p* < 0.05). Synonymous (black) and non-synonymous SNPs (red) are indicated. Regions informative for ocular localization and genes of interest are labelled in blue. b Disease severity-associated SNPs across the Ct genome. From 129 SNPs identified in coding and non-coding regions, SNPs associated with the disease severity phenotype at genome-wide significance are identified using permutation-based ordinal logistic regression models adjusting for age in the Ct genome-wide association analysis. The threshold for genome-wide significance is indicated by the dashed line (p* < 0.05). The y-axis shows the –log10 p value. A log10 p value of 1.3 is equivalent to a permuted p value of 0.05 (p* < 0.05). Genes significantly associated with disease severity are labelled in blue

Table 2.

SNPs across the Chlamydia trachomatis genome identified using permutation-based genome-wide association analysis for (A) ocular localization (non-synonymous only) and (B) disease severity

| (A) | |||||||||||||||

| SNP position | Ocular allele (%) | Urogenital allele (%) | Name A/HAR-13 | CDS | p value | p* | OR | 95% CI (UL) | 95% CI (LL) | t | SE(t) | MAF | N calls at locus | Ocular AA | Urogenital AA |

| 168,413 | A (61.54) | G (93.33) | CTA_0156 | CDS | 5E-05 | 1E-04 | 21.56 | 6.11 | 137.25 | 4.07 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.04 | H | R |

| 95,863 | A (60.47) | G (86.67) | CTA_0087 | CDS | 7E-05 | 1E-04 | 9.56 | 3.47 | 33.86 | 3.98 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.02 | E | G |

| 785,083 | A (62.20) | G (96.67) | pbpB | CDS | 2E-04 | 1E-04 | 45.92 | 9.34 | 831.41 | 3.70 | 1.03 | 0.49 | 0.05 | I | V |

| 777,345 | A (58.59) | G (96.67) | karG | CDS | 3E-04 | 1E-04 | 40.71 | 8.29 | 736.79 | 3.59 | 1.03 | 0.47 | 0.04 | Y | H |

| 156,982 | C (51.54) | T (90.00) | oppA_1 | CDS | 4E-04 | 1E-04 | 9.44 | 3.13 | 40.92 | 3.54 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.02 | V | I |

| 637,206 | A (56.59) | C (96.67) | sctR | CDS | 5E-04 | 1E-04 | 36.25 | 7.39 | 655.80 | 3.48 | 1.03 | 0.45 | 0.03 | K | Q |

| 157,069 | A (51.54) | G (86.67) | oppA_1 | CDS | 7E-04 | 3E-04 | 6.81 | 2.48 | 24.09 | 3.39 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.02 | S | P |

| 367,095 | C (60.77) | T (73.33) | CTA_0348 | CDS | 1E-03 | 1E-03 | 4.23 | 1.81 | 10.82 | 3.20 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.01 | T | I |

| 544,233 | A (61.54) | G (73.33) | CTA_0510 | CDS | 1E-03 | 3E-04 | 4.23 | 1.81 | 10.82 | 3.20 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.02 | R | G |

| 954,865 | A (59.69) | G (73.33) | pmpD | CDS | 2E-03 | 1E-04 | 4.04 | 1.73 | 10.33 | 3.10 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.04 | E | G |

| 969,418 | C (59.06) | T (73.33) | sucD | CDS | 2E-03 | 1E-04 | 3.94 | 1.68 | 10.07 | 3.04 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.03 | T | I |

| 544,610 | A (61.54) | G (70.00) | atoS | CDS | 3E-03 | 1E-03 | 3.59 | 1.56 | 8.85 | 2.92 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.01 | D | G |

| 543,548 | T (60.63) | C (70.00) | CTA_0508 | CDS | 5E-03 | 1E-04 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.67 | −2.83 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.06 | F | S |

| 969,583 | T (58.73) | C (70.00) | sucD | CDS | 7E-03 | 1E-04 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.70 | −2.72 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.04 | L | P |

| 44,611 | C (60.63) | T (66.67) | CTA_0043 | CDS | 1E-02 | 1E-04 | 2.96 | 1.30 | 7.10 | 2.53 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.04 | A | V |

| 533,906 | T (74.62) | C (50.00) | CTA_0498 | CDS | 1E-02 | 9E-03 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.80 | −2.51 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.01 | L | P |

| 295,635 | G (61.24) | A (63.33) | CTA_0284 | CDS | 2E-02 | 1E-04 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.86 | −2.30 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.03 | R | K |

| 95,527 | C (60.77) | T (60.00) | CTA_0087 | CDS | 5E-02 | 4E-02 | 2.24 | 1.00 | 5.15 | 1.94 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.01 | S | L |

| 413,567 | A (60.47) | G (60.00) | CTA_0391 | CDS | 6E-02 | 1E-04 | 2.21 | 0.99 | 5.08 | 1.91 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.04 | V | A |

| 1,027,490 | G (58.91) | T (60.00) | CTA_0948 | CDS | 7E-02 | 1E-04 | 2.13 | 0.96 | 4.91 | 1.83 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.01 | P | Q |

| 777,183 | T (58.59) | C (60.00) | karG | CDS | 7E-02 | 1E-04 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 1.06 | −1.80 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.04 | I | V |

| 168,413 | A (61.54) | G (93.33) | CTA_0156 | CDS | 5E-05 | 1E-04 | 21.56 | 6.11 | 137.2 | 4.07 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.04 | H | R |

| (B) | |||||||||||||||

| SNP position | Reference allele | Alternative allele | Name A/HAR-13 | CDS/NCR | Strand | p* | p value | t | SE(t) | OR | 95% CI (UL) | (LL) | MAF | N calls at locus | |

| 1,028,728 | C | T | pmpE | CDS | – | 0.013 | 0.011 | −2.550 | 0.555 | 0.078 | 0.026 | 0.232 | 0.310 | 7.042 | |

| 875,804 | C | T | alaS | CDS | – | 0.024 | 0.022 | −2.298 | 0.530 | 0.100 | 0.036 | 0.284 | 0.310 | 4.225 | |

| 939,488 | G | A | glgA | CDS | – | 0.026 | 0.023 | −2.273 | 0.491 | 0.103 | 0.039 | 0.270 | 0.479 | 4.225 | |

| 285,610 | G | A | CTA_0273 | CDS | – | 0.027 | 0.034 | −2.123 | 0.526 | 0.120 | 0.043 | 0.336 | 0.310 | 4.225 | |

| 32,779 | G | A | trmD | CDS | + | 0.032 | 0.031 | −2.160 | 0.525 | 0.115 | 0.041 | 0.323 | 0.310 | 2.817 | |

| 465,330 | C | G | yjfH | CDS | – | 0.037 | 0.042 | −2.032 | 0.519 | 0.131 | 0.047 | 0.362 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 787,841 | A | G | NA | inter | NA | 0.038 | 0.038 | −2.074 | 0.524 | 0.126 | 0.045 | 0.351 | 0.310 | 4.225 | |

| 827,184 | A | G | CTA_0774 | CDS | + | 0.041 | 0.043 | −2.020 | 0.516 | 0.133 | 0.048 | 0.365 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 22,049 | G | T | ileS | CDS | + | 0.057 | 0.050 | −1.962 | 0.505 | 0.141 | 0.052 | 0.378 | 0.324 | 4.225 | |

| 152,011 | G | A | NA | inter | NA | 0.058 | 0.050 | −1.964 | 0.505 | 0.140 | 0.052 | 0.377 | 0.324 | 4.225 | |

| 710,787 | A | C | CTA_0675 | CDS | – | 0.060 | 0.052 | −1.941 | 0.517 | 0.144 | 0.052 | 0.396 | 0.310 | 4.225 | |

| 19,085 | T | C | NA | inter | NA | 0.061 | 0.060 | −1.882 | 0.530 | 0.152 | 0.054 | 0.430 | 0.296 | 5.634 | |

| 388,175 | G | A | CTA_0368 | CDS | – | 0.061 | 0.059 | −1.889 | 0.524 | 0.151 | 0.054 | 0.422 | 0.296 | 1.408 | |

| 696,782 | A | T | rpoD | CDS | – | 0.064 | 0.062 | −1.864 | 0.511 | 0.155 | 0.057 | 0.422 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 286,636 | C | T | lgt | CDS | – | 0.065 | 0.061 | −1.876 | 0.511 | 0.153 | 0.056 | 0.417 | 0.310 | 0.000 | |

| 930,453 | C | T | mutS | CDS | – | 0.067 | 0.061 | −1.876 | 0.511 | 0.153 | 0.056 | 0.417 | 0.310 | 0.000 | |

| 465,525 | C | T | CTA_0439 | CDS | – | 0.067 | 0.062 | −1.865 | 0.472 | 0.155 | 0.061 | 0.391 | 0.493 | 1.408 | |

| 60,858 | G | A | CTA_0057 | CDS | – | 0.068 | 0.070 | −1.813 | 0.512 | 0.163 | 0.060 | 0.445 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 835,039 | G | A | CTA_0782 | CDS | – | 0.070 | 0.061 | −1.876 | 0.511 | 0.153 | 0.056 | 0.417 | 0.310 | 0.000 | |

| 19,005 | A | G | NA | inter | NA | 0.071 | 0.071 | −1.807 | 0.525 | 0.164 | 0.059 | 0.459 | 0.296 | 2.817 | |

| 4554 | A | G | gatB | CDS | + | 0.071 | 0.070 | −1.813 | 0.512 | 0.163 | 0.060 | 0.445 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 303,590 | C | A | murE | CDS | – | 0.072 | 0.061 | −1.876 | 0.511 | 0.153 | 0.056 | 0.417 | 0.310 | 0.000 | |

| 215,130 | C | T | gyrA_1 | CDS | – | 0.072 | 0.062 | −1.864 | 0.511 | 0.155 | 0.057 | 0.422 | 0.310 | 1.408 | |

| 806,382 | C | T | CTA_0761 | CDS | + | 0.073 | 0.058 | −1.896 | 0.530 | 0.150 | 0.053 | 0.424 | 0.296 | 4.225 | |

| 778,783 | G | A | rrf | CDS | – | 0.077 | 0.075 | −1.780 | 0.502 | 0.169 | 0.063 | 0.451 | 0.324 | 2.817 | |

| 136,812 | G | A | incF | CDS | + | 0.079 | 0.075 | −1.780 | 0.502 | 0.169 | 0.063 | 0.451 | 0.324 | 2.817 | |

| 169,573 | G | A | CTA_0156 | CDS | + | 0.082 | 0.077 | −1.771 | 0.523 | 0.170 | 0.061 | 0.474 | 0.310 | 9.859 | |

| 956,953 | C | T | pmpD | CDS | + | 0.082 | 0.072 | −1.800 | 0.523 | 0.165 | 0.059 | 0.461 | 0.296 | 2.817 | |

| 44,990 | A | G | ruvB | CDS | + | 0.087 | 0.086 | −1.718 | 0.493 | 0.179 | 0.068 | 0.472 | 0.338 | 2.817 | |

| 62,140 | G | T | sucA | CDS | + | 0.091 | 0.078 | −1.760 | 0.502 | 0.172 | 0.064 | 0.461 | 0.324 | 5.634 | |

| 542,521 | G | A | CTA_0507 | CDS | – | 0.092 | 0.090 | −1.696 | 0.494 | 0.183 | 0.070 | 0.483 | 0.338 | 2.817 | |

| 181,019 | C | A | CTA_0164 | CDS | – | 0.095 | 0.096 | −1.666 | 0.494 | 0.189 | 0.072 | 0.498 | 0.338 | 4.225 | |

| 151,156 | C | G | CTA_0140 | CDS | – | 0.096 | 0.077 | 1.770 | 0.502 | 5.871 | 2.195 | 15.703 | 0.324 | 4.225 | |

| 1,028,728 | C | A | pmpE | CDS | – | 0.01 | 0.011 | −2.550 | 0.555 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 13.58% | |

| 1,028,728 | C | T | pmpE | CDS | – | 0.0134 | 0.0108 | −2.5504 | 0.5550 | 0.0781 | 0.0263 | 0.2317 | 0.3099 | 7.0423 | |

| 875,804 | C | T | alaS | CDS | – | 0.0242 | 0.0216 | −2.2981 | 0.5295 | 0.1005 | 0.0356 | 0.2836 | 0.3099 | 4.2254 | |

| 939,488 | G | A | glgA | CDS | – | 0.0259 | 0.0230 | −2.2727 | 0.4906 | 0.1030 | 0.0394 | 0.2695 | 0.4789 | 4.2254 | |

| 285,610 | G | A | CTA_0273 | CDS | – | 0.0269 | 0.0338 | −2.1226 | 0.5264 | 0.1197 | 0.0427 | 0.3359 | 0.3099 | 4.2254 | |

| 32,779 | G | A | trmD | CDS | + | 0.0318 | 0.0308 | −2.1596 | 0.5248 | 0.1154 | 0.0412 | 0.3227 | 0.3099 | 2.8169 | |

| 465,330 | C | G | yjfH | CDS | – | 0.0370 | 0.0422 | −2.0315 | 0.5187 | 0.1311 | 0.0474 | 0.3625 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 787,841 | A | G | NA | inter | NA | 0.0377 | 0.0381 | −2.0742 | 0.5236 | 0.1257 | 0.0450 | 0.3506 | 0.3099 | 4.2254 | |

| 827,184 | A | G | CTA_0774 | CDS | + | 0.0413 | 0.0433 | −2.0203 | 0.5164 | 0.1326 | 0.0482 | 0.3648 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 22,049 | G | T | ileS | CDS | + | 0.0568 | 0.0497 | −1.9624 | 0.5052 | 0.1405 | 0.0522 | 0.3782 | 0.3239 | 4.2254 | |

| 152,011 | G | A | NA | inter | NA | 0.0578 | 0.0495 | −1.9642 | 0.5051 | 0.1403 | 0.0521 | 0.3775 | 0.3239 | 4.2254 | |

| 710,787 | A | C | CTA_0675 | CDS | – | 0.0605 | 0.0523 | −1.9409 | 0.5174 | 0.1436 | 0.0521 | 0.3958 | 0.3099 | 4.2254 | |

| 19,085 | T | C | NA | inter | NA | 0.0608 | 0.0598 | −1.8819 | 0.5298 | 0.1523 | 0.0539 | 0.4302 | 0.2958 | 5.6338 | |

| 388,175 | G | A | CTA_0368 | CDS | – | 0.0610 | 0.0589 | −1.8889 | 0.5238 | 0.1512 | 0.0542 | 0.4222 | 0.2958 | 1.4085 | |

| 696,782 | A | T | rpoD | CDS | – | 0.0638 | 0.0623 | −1.8643 | 0.5114 | 0.1550 | 0.0569 | 0.4223 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 286,636 | C | T | lgt | CDS | – | 0.0654 | 0.0606 | −1.8764 | 0.5113 | 0.1531 | 0.0562 | 0.4172 | 0.3099 | 0.0000 | |

| 930,453 | C | T | mutS | CDS | – | 0.0668 | 0.0606 | −1.8764 | 0.5113 | 0.1531 | 0.0562 | 0.4172 | 0.3099 | 0.0000 | |

| 465,525 | C | T | CTA_0439 | CDS | – | 0.0670 | 0.0622 | −1.8650 | 0.4719 | 0.1549 | 0.0614 | 0.3905 | 0.4930 | 1.4085 | |

| 60,858 | G | A | CTA_0057 | CDS | – | 0.0684 | 0.0698 | −1.8134 | 0.5121 | 0.1631 | 0.0598 | 0.4450 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 835,039 | G | A | CTA_0782 | CDS | – | 0.0700 | 0.0606 | −1.8764 | 0.5113 | 0.1531 | 0.0562 | 0.4172 | 0.3099 | 0.0000 | |

| 19,005 | A | G | NA | inter | NA | 0.0710 | 0.0707 | −1.8074 | 0.5254 | 0.1641 | 0.0586 | 0.4595 | 0.2958 | 2.8169 | |

| 4554 | A | G | gatB | CDS | + | 0.0713 | 0.0698 | −1.8134 | 0.5121 | 0.1631 | 0.0598 | 0.4450 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 303,590 | C | A | murE | CDS | – | 0.0718 | 0.0606 | −1.8764 | 0.5113 | 0.1531 | 0.0562 | 0.4172 | 0.3099 | 0.0000 | |

| 215,130 | C | T | gyrA_1 | CDS | – | 0.0722 | 0.0623 | −1.8643 | 0.5114 | 0.1550 | 0.0569 | 0.4223 | 0.3099 | 1.4085 | |

| 806,382 | C | T | CTA_0761 | CDS | + | 0.0726 | 0.0580 | −1.8960 | 0.5297 | 0.1502 | 0.0532 | 0.4241 | 0.2958 | 4.2254 | |

| 778,783 | G | A | rrf | CDS | – | 0.0767 | 0.0751 | −1.7797 | 0.5021 | 0.1687 | 0.0630 | 0.4514 | 0.3239 | 2.8169 | |

| 136,812 | G | A | incF | CDS | + | 0.0792 | 0.0751 | −1.7797 | 0.5021 | 0.1687 | 0.0630 | 0.4514 | 0.3239 | 2.8169 | |

| 169,573 | G | A | CTA_0156 | CDS | + | 0.0821 | 0.0765 | −1.7712 | 0.5227 | 0.1701 | 0.0611 | 0.4740 | 0.3099 | 9.8592 | |

| 956,953 | C | T | pmpD | CDS | + | 0.0823 | 0.0719 | −1.7998 | 0.5226 | 0.1653 | 0.0594 | 0.4605 | 0.2958 | 2.8169 | |

| 44,990 | A | G | ruvB | CDS | + | 0.0871 | 0.0858 | −1.7181 | 0.4932 | 0.1794 | 0.0682 | 0.4717 | 0.3380 | 2.8169 | |

| 62,140 | G | T | sucA | CDS | + | 0.0914 | 0.0784 | −1.7601 | 0.5024 | 0.1720 | 0.0643 | 0.4605 | 0.3239 | 5.6338 | |

| 542,521 | G | A | CTA_0507 | CDS | – | 0.0916 | 0.0899 | −1.6960 | 0.4940 | 0.1834 | 0.0696 | 0.4830 | 0.3380 | 2.8169 | |

| 181,019 | C | A | CTA_0164 | CDS | – | 0.0953 | 0.0958 | −1.6656 | 0.4940 | 0.1891 | 0.0718 | 0.4979 | 0.3380 | 4.2254 | |

| 151,156 | C | G | CTA_0140 | CDS | – | 0.0955 | 0.0767 | 1.7701 | 0.5019 | 5.8714 | 2.1953 | 15.7035 | 0.3239 | 4.2254 | |

(a) Ocular localization-associated non-synonymous SNPs (p value < 0.1). Position of the SNPs and name of the impacted gene are from the Ct A/HAR-13 (GenBank accession number NC_007429) genome. ‘Allele percentage’ is the percentage of each group where the given allele was present. ‘CDS/NCR’ identifies whether the SNP was in a coding or non-coding region. ‘p*’ indicates p values from 100,024 simulations indicating genome-wide significance at p* < 0.05. ‘t’ is the t statistic; SE(t) is the standard error of the t statistic. ‘OR’ is the adjusted odds ratio (derived from the t statistic). ‘95% CI’ = 95% confidence interval of the OR.; ‘UL’ upper limit, ‘LL’ lower limit. ‘MAF’ is the minor allele frequency. ‘N calls at locus’ is the proportion of isolates which had no base called. ‘AA’ is the amino acid coded for

(b) Disease severity-associated SNPs (p value < 0.1). Disease severity is defined by a composite in vivo conjunctival phenotype derived using principal component analysis using ocular C. trachomatis load and conjunctival inflammatory (P) score (using the modified FPC (follicles, papillary hypertrophy, conjunctival scarring) trachoma grading system [39]). ‘Reference allele’ indicates the reference allele on Ct A/HAR-13 (GenBank accession number NC_007429). ‘CDS/NCR’ identifies whether the SNP was in a coding, non-coding or intergenic region. ‘p*’ = permuted p value after 100,024 simulations indicating genome-wide significance at p* < 0.05. ‘t’ is the t statistic; SE(t) is the standard error of the t statistic. ‘OR’ is the adjusted odds ratio (derived from the t statistic). ‘95% CI’ = 95% confidence interval of the OR; ‘UL’ upper limit, ‘LL’ lower limit. ‘MAF’ is the minor allele frequency. ‘N calls at locus’ is the proportion of isolates which had no base called

Markers of disease severity in ocular C. trachomatis infection

Using permutation-based re-sampling methods, eight SNPs were found to be significantly associated with disease severity (Fig. 5b). Seven of these are in coding regions (relative to Ct A/HAR-13). Five are present at nucleotide positions 465,330 (OR = 0.13, p* = 0.037), 32,779 (OR = 0.12, p* = 0.032), 875,804 (OR = 0.10, p* = 0.024), 939,488 (OR = 0.10, p* = 0.026) and 1,028,728 (OR = 0.08, p* = 0.013) (where p* is the permuted p value with a genome-wide threshold of 0.05) representing synonymous codon changes within the genes yjfH, trmD, alaS, glgA and pmpE respectively. Three further genome-wide significant synonymous SNPs were present at positions 827,184 (OR = 0.3, p* = 0.041) within the predicted coding sequence (CDS) CTA0744, 285,610 (OR = 0.12, p* = 0.027) within CTA0273 and 787,841 (OR = 0.13, p* = 0.043) in the intergenic region between loci CTA0744–CTA0745 (Table 2b and Additional file 10: Figure S10).

Discussion

This collection of clinical ocular Ct WGS from a single trachoma-endemic population to be characterized has enabled us to describe the population diversity of naturally occurring Ct in a treatment-naïve population. We used detailed clinical grading combined with microbial quantitation to perform a GWAS and investigated associations between Ct polymorphisms with ocular localization and disease severity in trachoma.

Unlike the recently published Australian Ct sequences [10], all Bijagós sequences clustered as expected within the T2 ocular clade derived from a urogenital ancestor [59, 61], each with loci typically associated with ocular tissue localization (trpA and tarP). Although the Bijagós sequences conform to the classical ocular genotype, the phylogenetic data show greater than expected diversity compared to historical reference strains of ocular Ct [4] and a population of clinical ocular Ct sequences obtained from cultured clinical conjunctival swab specimens collected from another African trachoma-endemic population [64] (Additional file 4: Figure S4). Our use of direct WGS from clinical samples reveals the natural diversity of a population-based collection of endemic treatment-naïve ocular Ct infections. This diversity may indicate genome-wide selection for advantageous mutations as demonstrated in other pathogens [79] or simply the naturally diverse circulation of endemic treatment-naïve ocular Ct.

The apparent village-level clustering provides new evidence that WGS has the necessary molecular resolution to fully investigate Ct transmission. Although the number of sequences from each village was very small, overall Ct genomic diversity supports our hypothesis of ongoing or recent transmission, since diversity requires mutation, recombination and gene flow. The data from this study demonstrate such mutation and indicate that WGS data may be useful in defining transmission networks and developing transmission maps, which have not been adequately defined using alternative Ct genotyping systems. Whole genome mapping has previously been shown to be a useful tool in the analysis of outbreaks and bacterial pathogen transmission [80, 81] and thus has multiple potential applications in epidemiological analysis and transmission studies. However, greater numbers of sequences per village are required to validate this finding.

Such diversity is likely to be representative of recombination present in Ct [82]. Genome-wide recombination was common and widespread within these sequences. Extensive recombination has been noted in previous studies and is thought to be a source of diversification with possible interstrain recombination [4, 82]. Recombination may represent fixation of recombination in regions that are under diversifying selection pressure [4].

Recently, a handful of bacterial GWASs have provided insight into the genetic basis of bacterial host preference, antibiotic resistance and virulence [83–88]. Until now, most inferences regarding disease-modifying virulence factors in chlamydial infection have been derived from a limited number of comparative genomic studies where only a few virulence factors were associated with disease severity. Chlamydial genomic association data have previously been used to highlight genes potentially involved in pathoadaptation [10, 89] and tissue localization [90].

In the current GWAS we found 21 genome-wide significant non-synonymous SNPs associated with ocular localization and eight genome-wide significant synonymous SNPs associated with disease severity.

Confidence that new SNPs identified in the ocular localization GWAS are candidate markers of pathoadaptation is supported by the observation that half of the SNPs identified have previously been described as polymorphic or recombinant within Ct and the ocular serovars [8, 91–93].

In support of the hypothesis that early events in infection and intracellular growth are crucial events in Ct survival and pathogenicity, we identified SNPs within genes that are expressed from the beginning of the chlamydial developmental cycle including CTA0156 (encoding early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) [73]), CTA0498 (encoding translocated actin-recruiting phosphoprotein (tarP) [94]) and CTA0884 (encoding polymorphic membrane protein D (PmpD) [95]), which have identified roles in entry to and initial interactions with host cells.

Two of the four genes containing multiple non-synonymous SNPs (karG and sucD) are involved in ATP metabolism and, more generally, chlamydial metabolism. Two of the genes with multiple synonymous mutations (ruvB and CTA_0284) are also involved in metabolism. Growth rates are known to vary significantly between biovars. The developmental cycle in ocular serovars is substantially longer than that in genital serovars [96]. These genes and the identified SNPs may therefore be important in the differential growth and development of Ct serovars. This is supported by the downregulation of sucD expression during in vitro persistence. Slower growth in ocular strains occurs primarily in the entry and early stages of differentiation, which may also indicate the role of previously described genes involved in entry into cells.

The eight disease severity-associated SNPs are within less well-characterized genes. Apart from pmpE, the remaining genes identified in this study have been shown to be relatively conserved [90]. This suggests that these SNPs may be important in ocular Ct pathogenesis, rather than in longer term chlamydial evolution. Three of these genes are putative Ct virulence factors, with functions in nutrient acquisition (glgA [24, 28, 97]), host-cell adhesion (pmpE [98]) and response to IFNγ-induced stress (trmD [73]). Homologues of alaS [99, 100] and CTA0273 [101, 102] are known virulence factors in related Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that these genes are potentially important in Ct pathogenesis.

Transcriptome analysis of chlamydial growth in vitro has shown that there is highly upregulated gene expression of trmD (encoding a transfer RNA (tRNA) methyltransferase) associated with growth in the presence of IFNγ, thought to be important in the maintenance of chlamydial infection [73]. yjfH (renamed rlmB) is phylogenetically related to the TrmD family and encodes the protein RlmB, which is important for the synthesis and assembly of the components of the ribosome [103]. In Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae and Mycoplasma genitalium, RlmB catalyses the methylation of guanosine 2251 in 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which is of importance in peptidyl tRNA recognition but is not essential for bacterial growth [103, 104]. alaS encodes a tRNA ligase of the class II aminoacyl tRNA synthetase family involved in cytoplasmic protein biosynthesis. It is not known to have virulence associations in chlamydial infection, but has been described as a component of a virulence operon in Haemophilus ducreyi [99] and H. influenzae [100]. The CDS CTA0273 encodes a predicted inner membrane protein translocase component of the autotransporter YidC, an inner membrane insertase important in virulence in E. coli [101] and Streptococcus mutans [102]. Our study suggests that these loci may be important in disease severity and host-pathogen interactions in chlamydial infection. A summary of available literature for these key ocular localization and disease severity-associated SNPs is tabulated in Additional file 11: Figure S11. We cannot speculate further on the effect of these polymorphisms on expression. It is possible that the synonymous disease severity-associated SNPs are markers in linkage for disease-causing alleles that were not included in the final GWAS analysis. For both analyses, further mechanistic studies are required to establish causality and validity and to fully understand the nature of the associations presented.

Though we were intrinsically limited to those cases where infection was detectable and from which we were able to obtain Ct WGS data, our population-based treatment-naïve sample attempts to provide a representative picture of what is observed in ocular Ct infection. We acknowledge that there may be Ct genotypes that are cleared by the immune system such that we do not capture them in a cross-sectional study. We are limited to the small sample size in this study, but attempt to address the issues of statistical power and multiple testing by using a bi-dimensional conjunctival phenotype and permutation-based multivariable regression analysis. To date, many published microbial GWASs have sample sizes under 500 [105], including several key studies examining virulence [84] and drug resistance [85] in Staphylococcus aureus with sample sizes of 75 and 90 respectively.

Conclusions

The potential of bacterial GWASs has only recently been realized, and despite the limitations with sample size, their use to study Ct in this way is particularly important, since in vitro models are intrinsically difficult to develop, and it has not been possible to study urogenital Ct in the same way due to the lack of a clearly defined in vivo disease phenotype. The genomic markers identified in this study provide important direction for validation through in vitro functional studies and a unique opportunity to understand host-pathogen interactions likely to be important in Ct pathogenesis in humans. The greater than expected diversity within this population of naturally circulating ocular Ct and the clustering at village level demonstrate the potential utility of WGS in epidemiological and clinical studies. This will enable us to understand transmission in both ocular and urogenital Ct infection and will have significant public health implications in preventing and eliminating chlamydial disease in humans.

Additional files

Figure S1. Histogram and density plot showing log-transformed C. trachomatis load (omcB copies/swab) data. (PDF 111 kb)

Figure S2. Detailed summary of whole genome sequence (WGS) data quality control of Bijagós Chlamydia trachomatis sequences. (PDF 76 kb)

Figure S3. R Script used for (A) tissue localization and (B) disease severity Chlamydia trachomatis GWAS. (PDF 180 kb)

Figure S4. Maximum likelihood reconstruction of whole genome phylogeny of Chlamydia trachomatis sequences examined in the tissue localization analysis. (PDF 357 kb)

Figure S5. Maximum likelihood reconstruction of the ompA (CTA0742) phylogeny. (PDF 450 kb)

Figure S6. Recombination present across Bijagós Chlamydia trachomatis genome sequences using the pairwise homoplasy index (Phi) and the site-wise log likelihood support for the best-scoring maximum likelihood tree. (PDF 153 kb)

Figure S7. Tyrosine repeat regions and actin-binding domains in tarP (CTA0948) and polymorphisms in the trp operon (CTA0182–CTA0186) (trpR, trpB and trpA) within Bijagós (Bissau-Guinean) ocular Chlamydia trachomatis sequences. (PDF 49 kb)

Figure S8. Maximum likelihood reconstruction of phylogeny by polymorphic membrane protein (Pmp) genes A–I. (PDF 1738 kb)

Figure S9. Ocular localization-associated SNPs (p value < 0.1). (PDF 150 kb)

Figure S10. SNPs across the Chlamydia trachomatis genome associated with disease severity using permutation-based genome-wide association analysis. (PDF 158 kb)

Figure S11. Summary of published studies supporting the key ocular localization and disease severity-associated SNPs [106–114]. (PDF 105 kb)

Figure S12. European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI)) accession numbers relating to C. trachomatis sequence data analysed in this study. (PDF 75 kb)

Acknowledgements

We extend thanks to colleagues at the Programa Nacional de Saúde de Visão in the Ministério de Saúde Publica in Bissau, the study participants and dedicated field research team in Guinea-Bissau and the Medical Research Council (MRC) Unit The Gambia for their support and collaboration in this work.

Funding

ARL was funded by the Wellcome Trust through a Clinical Research Training Fellowship (grant number 097330/Z/11/Z). MJH and ChR were funded by a Wellcome Trust Program Grant (grant number 079246/Z/06/Z). ChR was funded by the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (grant number 105609/Z/14/Z). Work undertaken by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute by NRT, HSS and JH was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 098051) and the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (grant number 105609/Z/14/Z). TGC is funded by the MRC UK (grant numbers MR/K000551/1, MR/M01360X/1, MR/N010469/1). JP was funded by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) PhD studentship, and FC and HP were funded by Bloomsbury Colleges Research Fund PhD studentships.

Availability of data and materials

All sequence data are available from the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) short read archive. See Additional file 12: Figure S12 for details and accession numbers.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- Ct

Chlamydia trachomatis

- ddPCR

Droplet digital PCR

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EB

Elementary body

- FPC

Follicles, papillary hypertrophy, conjunctival scarring

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- indels

Insertions and deletions

- LGV

Lymphogranuloma venereum

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- MOMP

Major outer membrane protein

- NHP

Non-human primate

- NSS

Neighbour similarity score

- PC

Principal component

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

Authors’ contributions

ARL, RLB, MJH, SEB and NRT designed the study. ARL, SEB, EC and MN conducted the field study. ARL, ChR and SEB conducted the molecular laboratory work. LTC and INC performed the chlamydial cell culture. HSS and JH designed and performed the whole genome sequencing and initial FastQC. ARL, ChR, HP, FC and TGC conducted the GWAS analysis. HP, JP, SH, JH and HSS supported the phylogenetic analysis. ARL, HP, MJH, DCWM, TGC and NRT wrote the paper. All authors have contributed to and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Comitê Nacional de Ética e Saúde (Guinea-Bissau), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (UK) and The Gambia Government/MRC Joint Ethics Committee (The Gambia). Written informed consent to participate and publish anonymized patient data was obtained from all study participants or their guardians on their behalf if participants were children. A signature or thumbprint was considered an appropriate record of consent in this setting by the above ethical bodies. All communities received treatment for endemic trachoma in accordance with the World Health Organization and national policies following the survey.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish anonymized patient data was obtained from all study participants as described above.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13073-018-0521-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

A. R. Last, Email: anna.last@lshtm.ac.uk

H. Pickering, Email: harry.pickering@lshtm.ac.uk

C. h. Roberts, Email: chrissyhroberts@yahoo.co.uk

F. Coll, Email: francesc.coll@lshtm.ac.uk

J. Phelan, Email: jody.phelan@lshtm.ac.uk

S. E. Burr, Email: sarah.burr@lshtm.ac.uk

E. Cassama, Email: eunitxsil@gmail.com

M. Nabicassa, Email: pnlcegueira@yahoo.com.br

H. M. B. Seth-Smith, Email: hss@seth-smith.org

J. Hadfield, Email: jh22@sanger.ac.uk

L. T. Cutcliffe, Email: lesley.cutcliffe@btinternet.com

I. N. Clarke, Email: inc@soton.ac.uk

D. C. W. Mabey, Email: david.mabey@lshtm.ac.uk

R. L. Bailey, Email: robin.bailey@lshtm.ac.uk

T. G. Clark, Email: taane.clark@lshtm.ac.uk

N. R. Thomson, Email: nrt@sanger.ac.uk

M. J. Holland, Email: martin.holland@lshtm.ac.uk

References

- 1.Hu VH, et al. Epidemiology and control of trachoma: systematic review. Tropical Med Int Health. 2010;15(6):673–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez P, et al. Typing of Chlamydia trachomatis by restriction endonuclease analysis of the amplified major outer membrane protein gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1132–1136. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.6.1132-1136.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris SR, et al. Whole genome analysis of diverse Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies phylogenetic relationships masked by current clinical typing. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):413–4s1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caldwell HD, et al. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiates between genital and ocular isolates: implications in pathogenesis and infection tropism. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1757–1769. doi: 10.1172/JCI17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffrey BM, et al. Genome sequencing of recent clinical Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies loci associated with tissue tropism and regions of apparent recombination. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2544–2553. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01324-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunes A, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP. Genomic features beyond C. trachomatis phenotypes: what do we think we know? Infect Genet Evol. 2013;16:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kari L, et al. Pathogenic diversity among Chlamydia trachomatis ocular strains in non-human primates is affected by subtle genomic variations. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:449–456. doi: 10.1086/525285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butcher RMR, et al. Low prevalence of conjunctival infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in a treatment-naive trachoma-endemic region of the Solomon Islands. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(10):e0005051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson P, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis from Australian Aboriginal people with trachoma are polyphyletic composed of multiple distinctive lineages. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10688. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng L, et al. Survey, culture and genome analysis of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis in Tibetan boarding primary schools in Qinghai Province, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;6:207. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borges V, et al. Complete genome sequence of Chlamydia trachomatis ocular serovar C strain TW-3. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e01204–e01213. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01204-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darville T, Hiltke T. Pathogenesis of genital tract disease due to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Supplement_2):S114–S225. doi: 10.1086/652397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Valkengoed IG, et al. Overestimation of complication rates in evaluations of Chlamydia trachomatis screening programmes—implications for cost-effectiveness analyses. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(2):416–425. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey RL, et al. Molecular epidemiology of trachoma in a Gambian village. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:813–817. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.11.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreasen AA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis ompA variants in trachoma: what do they tell us? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(9):e306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, et al. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, et al. Transformation of a plasmid-free genital tract isolate with a plasmid vector carrying a deletion in CDS6 revealed that this gene regulates inclusion phenotype. Pathogens Dis. 2013;67(2):100–103. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longbottom D, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of genes coding for the highly immunogenic cluster of 90 kilodalton envelope proteins from the Chlamydia psittaci subtype that causes abortion in sheep. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1317–1324. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1317-1324.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes JP, et al. Polymorphisms in the nine polymorphic membrane proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis across all serovars: evidence for serovar Da recombination and correlation with tissue tropism. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:275–286. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.275-286.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockey DD, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. Cloning and characterization of a Chlamydia psittaci gene coding for a protein localized in the inclusion membrane of infected cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:617–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefty PS, Stephens RS. Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion system is encoded on ten operons preceded by a sigma 70-like promoter element. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:198–206. doi: 10.1128/JB.01034-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson JH, et al. In vivo and in vitro studies of Chlamydia trachomatis TrpR:DNA interaction. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59(6):1678–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connell CM, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 activation by Chlamydia trachomatis is plasmid dependent, and plasmid-responsive chromosomal loci are coordinately regulated in response to glucose limitation by C. trachomatis but not by C. muridarum. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1044–1056. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01118-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackstadt T, Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Fischer ER. Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:119–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson DE, et al. Inhibition of Chlamydiae by primary alcohols correlates with strain specific complement of plasticity zone phospholipase D genes. Infect Immun. 2006;74(1):73–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.73-80.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson JH, Hughes S, Hogan D. Polymorphisms in the Chlamydia trachomatis cytotoxin locus associated with ocular and genital isolates. Infect Immun. 2004;72(12):7063–7072. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7063-7072.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson JH, et al. The Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid is a transcriptional regulator of chromosomal genes and a virulence factor. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2273–2283. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00102-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frazer LC, et al. Plasmid-cured Chlamydia caviae activates TLR2-dependent signaling and retains virulence in the guinea pig model of genital tract infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song L, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-encoded pgp4 is a transcriptional regulator of virulence-associated genes. Infect Immun. 2013;81(3):636. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01305-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christiansen MT, et al. Whole genome enrichment and sequencing of Chlamydia trachomatis directly from clinical samples. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:591. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borges V, et al. Effect of long-term laboratory propagation on Chlamydia trachomatis genome dynamics. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;17:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borges V, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis in vivo to in vitro transition reveals mechanisms of phase variation and downregulation of virulence factors. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonner C, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis virulence factor CT135 is stable in vivo but highly polymorphic in vitro. Pathog Dis. 2015;73(6):ftv043. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton MJ, et al. Which members of a community need antibiotics to control trachoma? Conjunctival Chlamydia trachomatis load in Gambian villages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(10):4215–4222. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conway DJ, et al. Scarring trachoma is associated with polymorphisms in TNF-alpha gene promoter and with increased TNF-alpha levels in tear fluid. Infect Immun. 1997;65(3):1003–1006. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1003-1006.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West SK, et al. Progression of active trachoma to scarring in a cohort of Tanzanian children. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8(2–3):137–144. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.2.137.4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burton MJ, et al. Pathogenesis of progressive scarring trachoma in Ethiopia and Tanzania: two cohort studies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(5):e0003763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawson CR, Jones BR, Tarizzo ML. Guide to trachoma control in programs for the prevention of blindness. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid JS, et al. A principal component meta-analysis on multiple anthropometric traits identifies novel loci for body shape. Nat Comms. 2016;7:13357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, et al. Conditional and joint multiple SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variance influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44:S1–S3. doi: 10.1038/ng.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aschard H, et al. Maximising the power of principal component analysis of correlated phenotypes in genome wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Last AR, et al. Risk factors for active trachoma and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in treatment-naïve trachoma-hyperendemic communities of the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea Bissau. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6):e2900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Last A, et al. Plasmid copy number and disease severity in naturally occurring ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(1):324–327. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02618-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]