Abstract

Objectives

The present study aimed to test the association between high and low carbohydrate diets and obesity, and second, to test the link between total carbohydrate intake (as a percentage of total energy intake) and obesity.

Setting, participants and outcome measures

We sought MEDLINE, PubMed and Google Scholar for observation studies published between January 1990 and December 2016 assessing an association between obesity and high-carbohydrate intake. Two independent reviewers selected candidate studies, extracted data and assessed study quality.

Results

The study identified 22 articles that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria and quantified an association between carbohydrate intake and obesity. The first pooled strata (high-carbohydrate versus low-carbohydrate intake) suggested a weak increased risk of obesity. The second pooled strata (increasing percentage of total carbohydrate intake in daily diet) showed a weak decreased risk of obesity. Both these pooled strata estimates were, however, not statistically significant.

Conclusions

On the basis of the current study, it cannot be concluded that a high-carbohydrate diet or increased percentage of total energy intake in the form of carbohydrates increases the odds of obesity. A central limitation of the study was the non-standard classification of dietary intake across the studies, as well as confounders like total energy intake, activity levels, age and gender. Further studies are needed that specifically classify refined versus unrefined carbohydrate intake, as well as studies that investigate the relationship between high fat, high unrefined carbohydrate–sugar diets.

PROSPERO registration number

Keywords: high carbohydrate intake, obesity, observational

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Systematic review of observational studies across low income, middle income countries and high income countries and first to explore this angle as far as we are aware.

The scarcity of studies and/or data that either measured obesity risk versus total carbohydrate intake or alternatively measured obesity risk on the basis of a high versus low carbohydrate intake is a limitation.

The non-standardised instruments for total dietary and total carbohydrate intake across studies is a further limitation.

The heterogeneity in the classification of dietary carbohydrates and variation in staple carbohydrates is especially emphasised across different countries/cultures as well as developed versus developing settings and has been further compounded by socioeconomic changes over the last three decades.

Studies with high heterogeneity and varying design and measurement quality may limit the quality of evidence from this study.

Introduction

Global estimates in 2005 indicated 937 million people were overweight and 328 million were obese.1 In 2010, an estimated 3.4 million deaths, 3.9% of years of life lost, and 3.8% of disability-adjusted life-years worldwide, were attributed to overweight and obesity.2 The rate of change of obesity in this global study indicated significant increases in both men and women. In men the proportion of adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or greater increased from 28.8% in 1980 to 36.9% in 2013 and for women increased from 29.8% to 38%. These increases occurred in both developed and low income, middle income countries. In addition, significant increases in obesity were also recorded among children and adolescents in developed countries that indicated 23.8% of boys were either overweight or obese and 22.6% of girls. Overweight and obesity is also increasing in children and adolescents in low income, middle income countries and has risen from 8.1% in 1980 to 12.9% in 2013 for boys and from 8.4% to 13.4% for girls.2 The relationship between dietary intake, and specifically the role of carbohydrates and obesity at a population level, is also unclear.

The aetiology of obesity increasingly reflects excessive calorie intake matched with higher levels of sedentary activity that occur in the face of a worldwide urban migration. In this scenario, traditional diets are often replaced with low cost energy dense foodstuffs produced by the industrialised food.3–5 Body weight is ultimately determined by the interaction of genetic, environmental and psychosocial factors acting through the physiological mediators of energy intake and energy expenditure.6–8 Nevertheless, carbohydrates have been linked to disease for many decades9 and more recently with an epidemic of type 2 diabetes.10 Although there is no consistent evidence that carbohydrates have driven the current levels of global obesity, carbohydrates form a major component of most national diets.11

The objective of this systematic review/meta-analysis is to investigate the relationship between carbohydrate intake and obesity. More specifically, the first question is whether a high versus low carbohydrate diet is a risk factor for obesity and second, whether total carbohydrate intake is a risk factor related to obesity?

Materials and methods

Registration of protocol with PROSPERO

In accordance with the guidelines, the systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 8 June 2015. The protocol was also formally peer reviewed and published in BMJ Open. Carbohydrate intake, obesity, metabolic syndrome and cancer risk? A two-part systematic review and meta-analysis protocol to estimate attributability.12

This systematic review was aligned to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines13 to ensure all necessary steps have been followed (see online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2017-018449supp001.pdf (195.3KB, pdf)

Data sources and searches

We used MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar to identify suitable studies that evaluated the determinants of obesity including the effect of high versus low carbohydrate diets, as well as the percentage of carbohydrates in total dietary intake. Studies published between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 2016 were included. In addition, web-based studies that were unpublished (eg, reports or unpublished theses) were evaluated using research engines like Google Scholar. The following keywords or medical subject headings on MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar were used:

(‘carbohydrate’ OR ‘low carbohydrate’ OR ‘low carb’ OR ‘high carbohydrate’ OR ‘high carb’) AND (‘composition’ OR ‘diet’ OR ‘dietary’ OR ‘intake’ OR ‘determinant’) AND (‘obesity’ OR ‘obese’) AND (‘attributable’ OR ‘odds’ OR ‘risk’ OR ‘hazard’ OR ‘prevalence’).

Study screening and selection

We included studies examining healthy adults (18 years or older). We also included studies on people who were overweight or obese, but otherwise excluded (after evaluation) studies of populations restricted to specific diseases, conditions or metabolic disorders. Of specific interest were general population studies that investigated the prevalence of obesity in relation to detailed dietary intake.11 Studies quantifying dietary intake in terms of total carbohydrate intake as a percentage of total energy, and high versus low carbohydrate intake in relation to the odds of obesity, were included.

Two authors (KS, BS) independently screened study titles and abstracts for potential eligibility. Screening questions were developed and pilot-tested with a subset of records before implementation. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and the two authors independently applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to identify appropriate studies in this review. Disagreement was assessed using the kappa statistic and was resolved through discussion and a third arbitrator. We developed a summary table with characteristics of included studies. Reasons for exclusion of studies were documented.

Appraisal of the quality of included studies

Three reviewers (KS, CS, TM) were content experts and one reviewer was an experienced biostatistician and epidemiologist (BS). The contents experts only assessed potential publications with respect to the appropriateness of the research questions being tested. The biostatistician only evaluated the appropriateness of the individual study methods employed to ensure that an OR was developed to assess the relationship between carbohydrate intake and the risk of obesity.

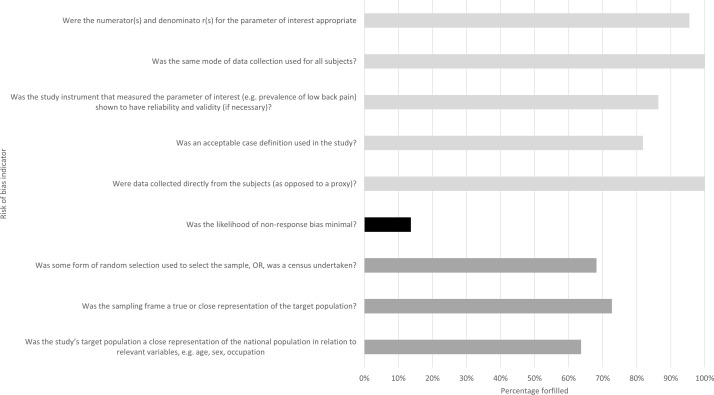

Two reviewers (BS, KS) also evaluated studies for quality and bias using an adapted version of the Risk of Bias Tool for Prevalence Studies developed by Hoy et al.14 The tool has nine indicators to assess risk of bias which include the representativeness of sample, sampling frame, random selection, non-response bias, direct informant and reliability/validity of the instrument(s). We dichotomised the quality appraisal for each item on the Hoy scale as ‘low risk’, that is, 0 or ‘high risk’, that is, 1. We further classified a response rate <80% with no assessment of responders versus non-responders as high risk in our assessment of the non-response indicator. If the selected text of the manuscript was unclear with regards to s specific indicator, when then assigned a high risk of bias. A study was considered to have a high overall risk of bias if ≤3 criteria were met, moderate risk of bias if 4–6 criteria were met and low risk of bias if studies met 7–9 criteria. The detailed assessment of risk of bias for the selected 22 studies are presented in online supplementary table 2. Only 1 study was scored as having a high risk of bias, 7 scored a medium risk of bias and the majority (n=14) were scored as low risk of bias. The potential of non-response bias appeared high based on the 80% minimum response rate cut-off. The sampling frame and strategy were the next least fulfilled criteria based on the bias criteria indicators on the Hoy instrument (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk of bias assessment of the nine indicators comparing the Hoy et al14 instrument (light grey, low risk; medium grey, moderate risk; black, high risk).

bmjopen-2017-018449supp002.pdf (236KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included cross-sectional, case–control or cohort studies assessing risk factors for obesity including dietary carbohydrate intake (carbohydrate percentage intake of total energy and high vs low carbohydrate intake). Case series or case reports without controls were excluded. We excluded studies assessing restricted dietary interventions as our primary objective was to assess reported carbohydrate intake and measured obesity in normal diet. Studies not performed in human participants were excluded, as were studies lacking primary data and/or explicit method description. Studies with major ethical issues were also excluded. The classification of obesity was based on BMI or visceral obesity (waist circumference). We considered both published and unpublished studies. No language restriction was applied.

Data extraction and management

Feedback was solicited from the research team regarding the draft list of data variables for extraction. Data extraction forms were developed and pilot-tested in Distiller SR. One person (BS) extracted all the information. A second person (KS) verified 20% of studies for general characteristics information and 100% of studies regarding outcome data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third team member. Information on the descriptive and quantitative characteristics of studies included the following: publication details (eg, year of publication, language, publication status), characteristics of study (eg, study design, methods, country, setting, sample size, number of centres (if applicable), duration of follow-up, source of funding), characteristics of population (eg, age, gender, ethnicity, cointerventions, information regarding respondent bias or representativeness of the included population) and details about the exposure (eg, type of diet, percentage of total calories obtained from carbohydrate consumption, method of assessing carbohydrate consumption; type of educational or other interventions and description, type of professional delivering intervention). Following extraction of data we noted the need to stratify the studies in two exposure strata, namely:

High versus low carbohydrate intake.

Total carbohydrate percentage intake of total energy.

Data synthesis/analysis

Data were analysed using a random-effect meta-analysis model and incorporating a restricted maximum-likelihood variance estimator. Effect measures were presented as ORs with 95% CIs. All analyses were performed using R software V.3.2.0 or later (R Core Team (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org/). The following packages were of R software were used for the meta-analyses: ‘meta’ V.4.2–0 (General Package for Meta-Analysis) and ‘metafor’ V.1.9–7 (A comprehensive collection of functions for conducting meta-analyses in). Recent Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines were used for preparing summary tables for the primary outcomes.15 16

Heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in our meta-analysis using the I2 statistic. If the I2 was greater than 50% we regarded this as substantial heterogeneity.

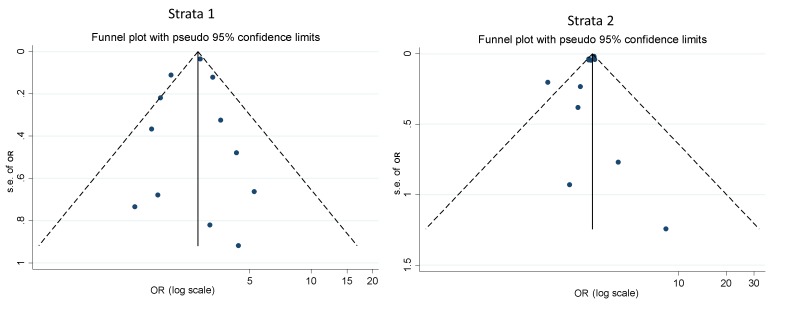

Publication bias

We investigated publication bias using funnel plots and Eggers test.17 In cases where asymmetry was present based on visual assessment, we performed exploratory analyses to investigate and adjust this using trim and/or fill analysis.18

Sensitivity analysis

To further identify potential sources of heterogeneity, we performed the following subgroup analysis by type of carbohydrate intake that is, high versus low classification compared with carbohydrate percentage intake of total energy.

Results

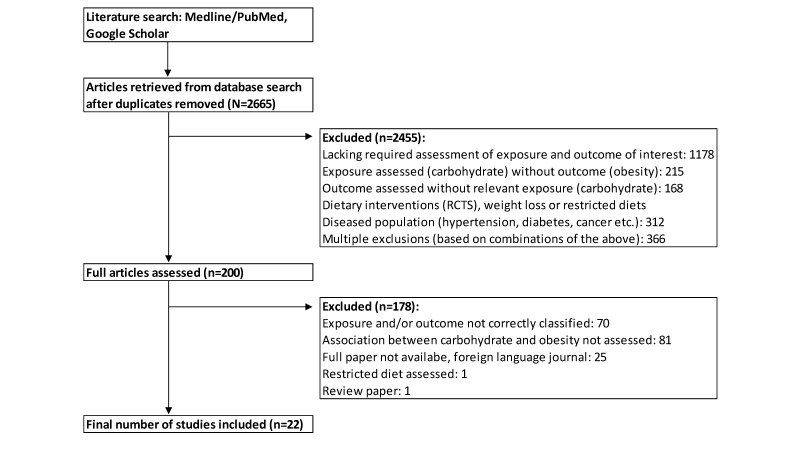

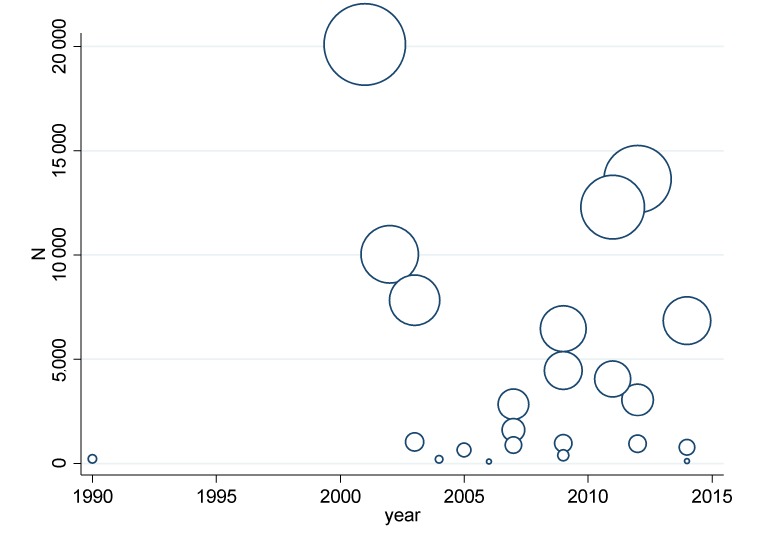

Of 2665 retrieved citations, 200 articles were selected following abstract screening, following which 22 articles met the inclusion criteria. Figure 2 shows our search and selection/exclusion process. There was high agreement between articles selected based on abstract screening between the two reviewers (96.12% agreement between two independent raters, *kappa statistic=0.633, P<0.001). Figure 3 shows that all but one of the eligible and selected articles were published since 2000. There were a few large studies in early 2000s, a decrease in sample size of studies in mid-2000s period and then increase in sample size from 2009.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection following search and selection/exclusion process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Figure 3.

Study sample size by year (combined strata).

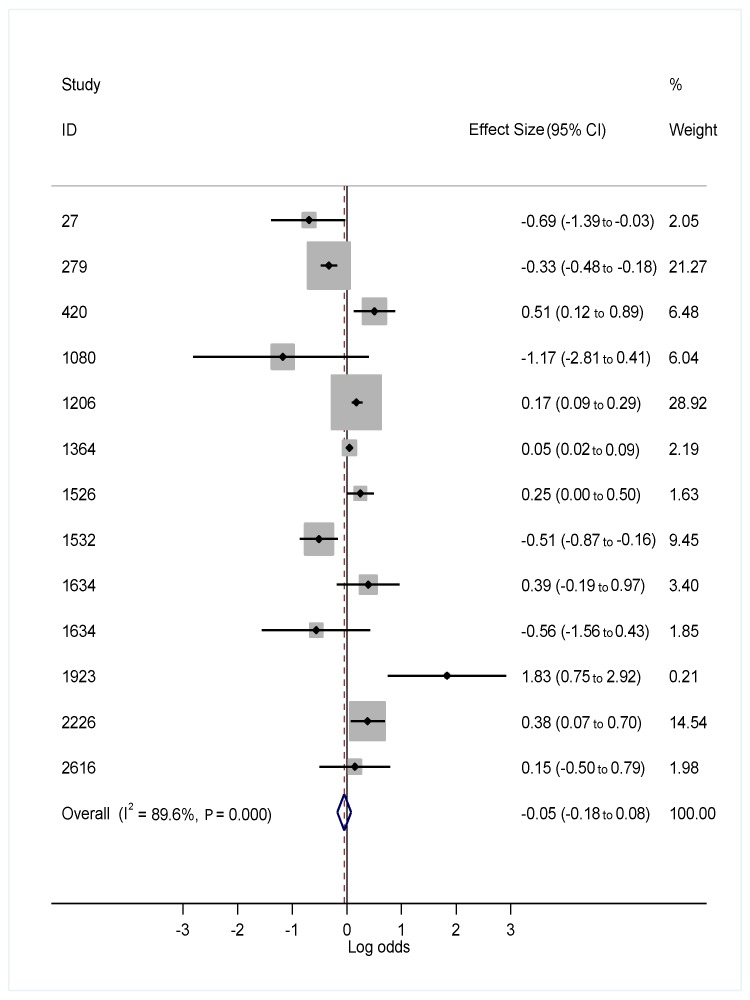

The ORs of becoming obese based on carbohydrate intake were tested using two strata of data (table 1). Stratum 1 was based on high versus low classification of carbohydrate intake while stratum two assessed carbohydrate percentage intake of total energy. In stratum 1, 13 adult-based studies showed a non-significant pooled OR of 1.043 (95% CI: 0.933 to 1.154) indicating a slight positive relationship between high-carbohydrate intake and obesity (figure 4). Within this stratum, eight studies showed an increased risk of obesity and five studies a reduced risk of obesity. Of the eight studies showing an increased risk, four Korean-based studies, making up 51.92% of the total pooled sample, showed an increased risk of obesity related to high-carbohydrate diets (ID 420, 2616), a high-carbohydrate rice-based diet (1206) and a high carbohydrate refined grains based diet (2226). Two studies in the South Western United States showed contrasting odds in the risk of obesity across two ethnic groups. In these two studies, Hispanic women indicated a reduced risk of obesity in relation to a high-carbohydrate diet, whereas white women indicated an increased risk of obesity. The highest odds of increased obesity were indicated in a Sri Lankan study involving high levels of inactivity, as well as a high-carbohydrate intake.

Table 1.

ORs (and log odds) for developing obesity as a result of high versus low carbohydrate diet (strata 1) or increasing carbohydrate intake percentage (strata 2)

| Strata | Identification Number |

Study | Exposure measured | OR | 95% CI | Log OR | 95% CI | Sample size |

| 1 | 27 | Ahluwalia et al48 | ||||||

| 1 | 279 | Bowman and Spence49 | Above 55% calories (high) vs 0%–30% calories (very low) | 0.72 | 0.62 to 0.84 | −0.14 | −0.21 to −0.08 | 10 014 |

| 1 | 420 | Choi et al50 | Quartile (Q) 4 vs 1 | 1.66 | 1.13 to 2.43 | 0.22 | 0.05 to 0.39 | 3050 |

| 1 | 1080 | Jackson et al51 | Tertiale 3 vs 1 for Carbohydrate intake | 0.31 | 0.06 to 1.50 | −0.51 | −1.22 to 0.18 | 2842 |

| 1 | 1206 | Kim et al52 | Tertiale 3 vs 1 for white rice and kimchi | 1.19 | 1.09 to 1.33 | 0.08 | 0.04 to 0.12 | 13 618 |

| 1 | 1364 | Lin et al53 | Rice dietary pattern | 1.05 | 1.02 to 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 1030 |

| 1 | 1526 | Meng et al54 | Staple food and vegetables higher obesity (Q4 vs Q1 higher proportion carb intake) | 1.28 | 1.00 to 1.64 | 0.11 | 0 to 0.22 | 768 |

| 1 | 1532 | Merchant et al55 | Quartiles of carbohydrate intake compared with the lowest intake category (Q4 vs Q1) | 0.60 | 0.42 to 0.85 | −0.22 | −0.38 to −0.07 | 4451 |

| 1 | 1634 | Murtaugh et al56 | High versus low: carbohydrate (% energy)—non-Hispanic (white) | 1.48 | 0.83 to 2.63 | 0.17 | −0.08 to 0.42 | 1599 |

| 1 | 1634 | Murtaugh et al56 | High versus low: carbohydrate (% energy)—Hispanic | 0.57 | 0.21 to 1.54 | −0.24 | −0.68 to 0.19 | 871 |

| 1 | 1923 | Rathnayake et al57 | Percent of energy from carbohydrate: high (≥70%) | 6.26 | 2.11 to 18.57 | 0.80 | 0.32 to 1.27 | 100 |

| 1 | 2226 | Song et al58 | Energy from Carbohydrates (Q5 vs Q1) | 1.46 | 1.07 to 2.01 | 0.16 | 0.03 to 0.30 | 6845 |

| 1 | 2616 | Youn et al59 | Q4 vs Q1 carbohydrate intake | 1.16 | 0.60 to 2.21 | 0.06 | −0.22 to 0.35 | 933 |

| 2 | 130 | Austin et al60 | Carbohydrate intake (% of energy)—NHANES I | 0.99 | 0.95 to 1.04 | 0.00 | −0.02 to 0.02 | 12 276 |

| 2 | 130 | Austin et al60 | Carbohydrate intake (% of energy)—NHANES 2005/2006 | 0.99 | 0.95 to 1.03 | 0.00 | −0.02 to 0.01 | 4057 |

| 2 | 782 | Garaulet et al61 | Carbohydrate intake (% of energy) | 0.71 | 0.25 to 2.07 | −0.15 | −0.60 to 0.32 | 193 |

| 2 | 930 | Hartline-Grafton et al62 | Carbohydrate intake (% of energy) | 0.83 | 0.54 to 1.29 | −0.08 | −0.27 to 0.11 | 373 |

| 2 | 1297 | Langlois et al63 | Carbohydrate intake (% of energy) | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.07 | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.03 | 6454 |

| 2 | 1410 | Lyles III et al64 | Carbohydrate dietary variety score | 1.42 | 0.85 to 2.36 | 0.15 | −0.07 to 0.37 | 74 |

| 2 | 1426 | Ma et al65 | Daily dietary glycemic index versus BMI continuous | 2.12 | 1.23 to 3.67 | 0.33 | 0.09 to 0.56 | 641 |

| 2 | 1480 | Maskarinec et al66 | Carbohydrate (1 g/100 kcal) | 1.08 | 1.04 to 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.02 to 0.05 | 101 699 |

| 2 | 1557 | Miller et al67 | Lean vs obese subjects and energy derived from carbohydrates | 0.87 | 0.67 to 1.13 | −0.06 | −0.18 to 0.05 | 216 |

| 2 | 1587 | Mokhtar et al68 | Carbohydrate mean daily energy intake | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 to 0.04 | 20 080 |

| 2 | 2591 | Yang et al69 | Carbohydrate intakes (% of energy) | 0.39 | 0.24 to 0.64 | −0.41 | −0.62 to −0.19 | 7828 |

BMI, body mass index; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of association (logs OR) between high and low carbohydrate intake and obesity.

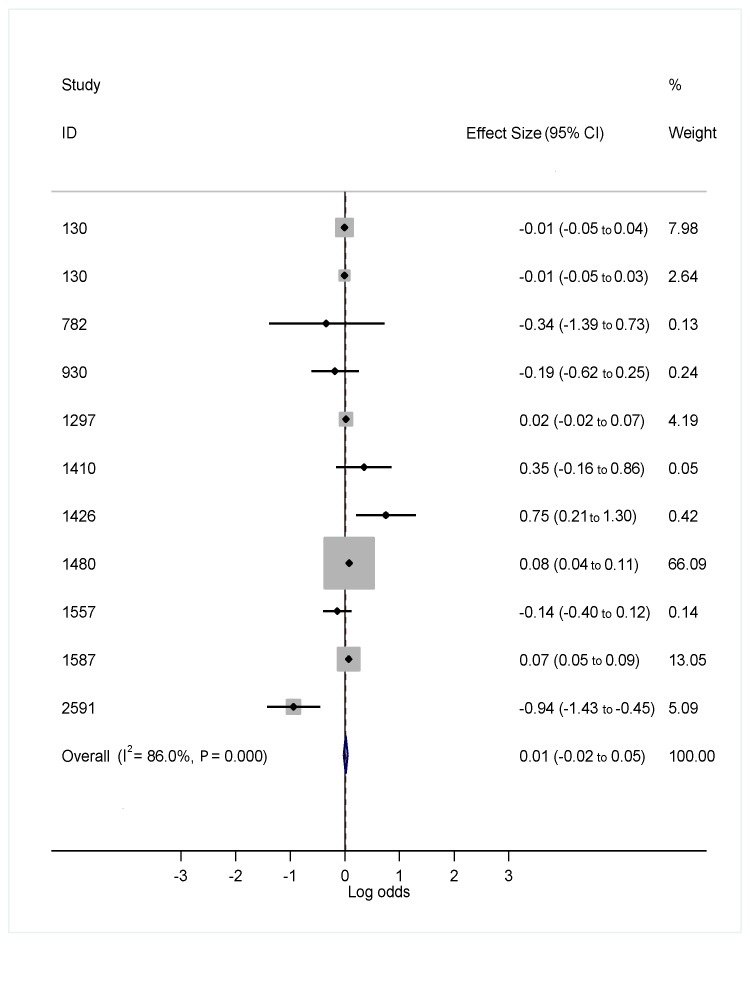

In strata 2, 11 adult-based studies investigated the relationship between total calorie intake of carbohydrates and the odds of obesity. Six studies showed a reduced risk and five an increased risk (figure 5), once more with a non-significant pooled OR of 0.984 (95% CI: 0.926 to 1.042), in opposite direction to results observed for stratum 1 (table 1). One study, involving multiple surveys of a multiethnic Hawaiian population (ID 1480), making up 66% of the total pooled sample, indicated a 7.7% increased risk of obesity in response to a higher percentage of total carbohydrate intake. Conversely, the three US-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), making up 15.71% of the total pooled sample indicated no increased risk (ID 130, 130) or a reduced risk of obesity (ID 2591).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of association (log OR) between percentage of total carbohydrate intake and obesity.

The results of the meta-analyses by strata both suggested prominent heterogeneity across individual studies (stratum 1 I2=85.4%; strata 2 I2=86.1%). Possible reasons for this are discussed under the limitations section.

Publication bias: the P-values from the Egger test for publication bias by strata both suggested no significant publication bias (stratum 1 P=0.691; strata 2 P=0.199). A visualisation based on funnel plots (figure 6) confirmed a likely lack of potential publication bias.

Figure 6.

Funnel plots for assessment of publication bias by strata.

Discussion

The results of this systematic review/meta-analysis study, suggest that a higher proportion of carbohydrates in unrestricted diets do not increase obesity levels. Our paper, therefore, cannot contradict the assumption of the total energy intake/expenditure paradigm as the primary driver of body weight, modulated by an interaction of genetic, environmental and psychosocial factors.6–8 Other studies, however, have indicated that certain dietary carbohydrates, like sugar sweetened beverages, have been shown to be positively associated with weight gain.11 19 20

The results of a number of systematic reviews, investigating high versus low carbohydrate restricted calorie diets, are interesting. In terms of achieving weight loss on a restricted calorie diet, both high fat—low carbohydrate and low fat—high carbohydrate diets were equally effective although there were differences in serum lipid profiles.21–23 Low carbohydrate restricted calorie diets (high fat) have shown that they induce at least the same level (or more) of weight loss than their low fat (high carbohydrate) counterpart diets.1 24 25 Low-carbohydrate diets also substantially reduce body weight, BMI, abdominal circumference, systolic and diastolic BP and triglycerides, as well as fasting glucose, glycated haemoglobin, plasma insulin and plasma C reactive protein, as well as increasing high-density lipoprotein.26 From a physiological perspective, low-carbohydrate diets may decrease calorie intake because they increase demands on protein and amino acid turnover for gluconeogenesis which has a high energy cost. Alternatively, low-carbohydrate diets may induce weight loss due to reducing insulin concentrations, thus promoting free fatty acid mobilisation from body fat storage.27 Low-carbohydrates diets are also related to weight loss because of increased levels of satiety thus positively re-enforcing reduced calorie intake.28 29

The linkage between carbohydrates and obesity continues to be an intense debate with no clear resolution at this stage. A major issue that needs to be addressed is whether the opposing roles of carbohydrates in disease is paralleled by their role in obesity. The good and bad role of refined versus unrefined carbohydrates is well documented in disease.30–32 Refined carbohydrates and sugars have long been labelled as the cause of ‘saccharine disease’ involving a wide variety of vascular disorders,9 metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes,33 cardiovascular and kidney disease.34 Conversely, the protective role of unrefined carbohydrates is reflected in a ‘consistent, inverse association between dietary whole grains and the incidence of cardiovascular disease’.30 In general, moreover, pooled meta-analyses have indicated a protective effect from the consumption of coarse grains.35 36 Interestingly, a recent projection of longevity in 35 industrialised countries reflects that carbohydrates are an integral aspect of the diets of the four leading countries.37–39 The opposing roles of dietary carbohydrates and obesity is also supported in the literature that demonstrates bad carbohydrates (unrefined carbohydrates and sugar) promote obesity while unrefined carbohydrates may have the opposite effect.7 11 40 However, the same evidence of good and bad carbohydrates in obesity is far from conclusive and the studies included in this paper provided insufficient evidence of the risk of obesity relating to different categories of carbohydrates as envisaged in our initial research protocol.

Many limitations persist to establish whether there is a direct link between high-carbohydrate intake and obesity. First, the non-standard nature of dietary records used across different settings make it difficult to compare the results in a meta study. In particular, the selected studies did not quantify different classes of carbohydrates.41 42 This is further complicated by significant changes in carbohydrate type and proportion in the same population groups over time.43 Finally, multiple confounding influences are nuanced across different populations, as well as age, gender and different ethnic groups in the same population, as well as differences across the urban–rural divide.6 44 45

A further limitation of our study was the concentration of a few countries in the two strata and the recognition that different populations/subpopulations consume varying proportions of different categories of carbohydrates in their daily diet.46 This limitation is further nuanced by the nutrition transition experienced in industrialising countries in which higher a proportion of carbohydrates consumed consist of refined carbohydrates and sugars.47 In the first stratum, the weighting of the pooled sample was largely made up of South Korean and United States data. In the second stratum, the pooled sample was influenced by a large sample resulting from multiple surveys of a multiethnic Hawaiian population. A further limitation was the heterogeneity across studies as evidenced by the large I2 statistics. This was potentially due to the heterogeneity in the classification of dietary intake across the studies.

Conclusion

Based on our findings it cannot be concluded that a high-carbohydrate diet, or increased percentage of total energy intake in the form of carbohydrates, increases the odds of being obese. Mounting evidence exists, however, to indicate that the obesity epidemic has occurred during the industrial food era that has promoted the increased intake of refined carbohydrates and sugars. Further studies are needed that specifically investigate obesity as a function of different carbohydrate groups including refined versus unrefined carbohydrate intake. In parallel, prospective studies are needed to ascertain the relationship between obesity and long term high fat, high unrefined carbohydrates–sugar diets. We, therefore, advise readers that the assumption that all carbohydrates are not linked to obesity, is potentially erroneous.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Colleen Aldous and Professor Timothy Noakes for their input into the protocol which was designed for this study and previously published.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the systematic literature review, the collection and screening of publications. KS and BS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the findings. KS and BS drafted the manuscript. TM and CS reviewed and provided input to revise the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for submission.

Funding: This study was partly funded through the MRC South Africa (University of KwaZulu-Natal Gastrointestinal Cancer Research Centre (GICRC)).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hu T, Mills KT, Yao L, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets versus low-fat diets on metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176(suppl 7):44–54. 10.1093/aje/kws264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science 1998;280:1371–4. 10.1126/science.280.5368.1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Obesity in Britain: gluttony or sloth? BMJ 1995;311:437–9. 10.1136/bmj.311.7002.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gluckman P, Nishtar S, Armstrong T. Ending childhood obesity: a multidimensional challenge. Lancet 2015;385:1048–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60509-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jebb SA. Aetiology of obesity. Br Med Bull 1997;53:264–85. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jebb SA. Dietary strategies for the prevention of obesity. Proc Nutr Soc 2005;64:217–27. 10.1079/PNS2005429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jéquier E. Pathways to obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26(Suppl 2):12–17. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleave TL. The saccharine disease: conditions caused by the taking of refined carbohydratessuch as sugar and white flour: Elsevier, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiNicolantonio JJ, O’Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Added fructose: a principal driver of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jebb SA. Carbohydrates and obesity: from evidence to policy in the UK. Proceedings of the nutrition society. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sartorius B, Sartorius K, Aldous C, et al. Carbohydrate intake, obesity, metabolic syndrome and cancer risk? A two-part systematic review and meta-analysis protocol to estimate attributability. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009301 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N, et al. GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables-binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:158–72. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt GH, Thorlund K, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 13. Preparing summary of findings tables and evidence profiles-continuous outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:173–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Y, Olendzki B, Chiriboga D, et al. Association between dietary carbohydrates and body weight. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:359–67. 10.1093/aje/kwi051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:274–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fagerberg B, Andersson O, Nilsson U, et al. Weight-reducing diets: role of carbohydrates on sympathetic nervous activity and hypotensive response. Int J Obes 1984;8:237–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foraker RE, Pennell M, Sprangers P, et al. Effect of a low-fat or low-carbohydrate weight-loss diet on markers of cardiovascular risk among premenopausal women: a randomized trial. J Womens Health 2014;23:675–80. 10.1089/jwh.2013.4638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noakes M, Keogh JB, Foster PR, et al. Effect of an energy-restricted, high-protein, low-fat diet relative to a conventional high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of cardiovascular health in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:1298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:285–93. 10.1001/archinte.166.3.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hession M, Rolland C, Kulkarni U, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes Rev 2009;10:36–50. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos FL, Esteves SS, da Costa Pereira A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of the effects of low carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Obes Rev 2012;13:1048–66. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, et al. Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:260–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halton TL, Hu FB. The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:373–85. 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noakes TD, Windt J. Evidence that supports the prescription of low-carbohydrate high-fat diets: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:133–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2008;18:283–90. 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clar C, Al-Khudairy L, Loveman E, et al. Low glycaemic index diets for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;7:CD004467 10.1002/14651858.CD004467.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly SAM, Hartley L, Loveman E, et al. Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;104 10.1002/14651858.CD005051.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2477–83. 10.2337/dc10-1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson RJ, Segal MS, Sautin Y, et al. Potential role of sugar (fructose) in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fardet A, Boirie Y. Associations between food and beverage groups and major diet-related chronic diseases: an exhaustive review of pooled/meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Nutr Rev 2014;72:741–62. 10.1111/nure.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slavin JL, Jacobs D, Marquart L, et al. The role of whole grains in disease prevention. J Am Diet Assoc 2001;101:780–5. 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00194-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, et al. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet 2017;389:1323–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32381-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poulain JP. The contemporary diet in France: “de-structuration” or from commensalism to “vagabond feeding”. Appetite 2002;39:43–55. 10.1006/appe.2001.0461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SH, Kim MS, Lee MS, et al. Korean diet: characteristics and historical background. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2016;3:26–31. 10.1016/j.jef.2016.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aller EE, Abete I, Astrup A, et al. Starches, sugars and obesity. Nutrients 2011;3:341–69. 10.3390/nu3030341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sempos CT, Johnson NE, Smith EL, et al. Effects of intraindividual and interindividual variation in repeated dietary records. Am J Epidemiol 1985;121:120–30. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A, et al. Comparison of dietary assessment methods in nutritional epidemiology: weighed records v. 24 h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J Nutr 1994;72:619–43. 10.1079/BJN19940064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28 Suppl 3:2–9. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM, Catalano PM. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:964–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jebb SA, Moore MS. Contribution of a sedentary lifestyle and inactivity to the etiology of overweight and obesity: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31(Suppl 11):S534–41. 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merchant AT, Anand SS, Kelemen LE, et al. Carbohydrate intake and HDL in a multiethnic population. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev 1997;55:31–43. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahluwalia N, Ferrières J, Dallongeville J, et al. Association of macronutrient intake patterns with being overweight in a population-based random sample of men in France. Diabetes Metab 2009;35:129–36. 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman SA, Spence JT. A comparison of low-carbohydrate vs. high-carbohydrate diets: energy restriction, nutrient quality and correlation to body mass index. J Am Coll Nutr 2002;21:268–74. 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi J, Se-Young O, Lee D, et al. Characteristics of diet patterns in metabolically obese, normal weight adults (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 2005). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012;22:567–74. 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson M, Walker S, Cruickshank JK, et al. Diet and overweight and obesity in populations of African origin: Cameroon, Jamaica and the UK. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:122–30. 10.1017/S1368980007246762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Jo I, Joung H. A rice-based traditional dietary pattern is associated with obesity in Korean adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:246–53. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin H, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns of Hispanic elders are associated with acculturation and obesity. J Nutr 2003;133:3651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng P, Jia L, Gao X, et al. [Overweight and obesity in Shanghai adults and their associations with dietary patterns]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2014;43:567–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Merchant AT, Vatanparast H, Barlas S, et al. Carbohydrate intake and overweight and obesity among healthy adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:1165–72. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murtaugh MA, Herrick JS, Sweeney C, et al. Diet composition and risk of overweight and obesity in women living in the southwestern United States. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:1311–21. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rathnayake KM, Roopasingam T, Dibley MJ. High carbohydrate diet and physical inactivity associated with central obesity among premenopausal housewives in Sri Lanka. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:564 10.1186/1756-0500-7-564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song S, Lee JE, Song WO, et al. Carbohydrate intake and refined-grain consumption are associated with metabolic syndrome in the Korean adult population. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114:54–62. 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Youn S, Woo HD, Cho YA, et al. Association between dietary carbohydrate, glycemic index, glycemic load, and the prevalence of obesity in Korean men and women. Nutr Res 2012;32:153–9. 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971-2006. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:836–43. 10.3945/ajcn.110.000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garaulet M, Marín C, Pérez-Llamas F, et al. Adiposity and dietary intake in cardiovascular risk in an obese population from a Mediterranean area. J Physiol Biochem 2004;60:39–49. 10.1007/BF03168219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartline-Grafton HL, Rose D, Johnson CC, et al. Are school employees role models of healthful eating? Dietary intake results from the ACTION worksite wellness trial. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:1548–56. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.06.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Langlois K, Garriguet D, Findlay L. Diet composition and obesity among Canadian adults. Health Rep 2009;20:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lyles TE, Desmond R, Faulk LE, et al. Diet variety based on macronutrient intake and its relationship with body mass index. MedGenMed 2006;8:359–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma Y, et al. Association between Dietary Carbohydrates and Body Weight. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:359–67. 10.1093/aje/kwi051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maskarinec G, Takata Y, Pagano I, et al. Trends and dietary determinants of overweight and obesity in a multiethnic population. Obesity 2006;14:717–26. 10.1038/oby.2006.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller WC, Lindeman AK, Wallace J, et al. Diet composition, energy intake, and exercise in relation to body fat in men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 1990;52:426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mokhtar N, Elati J, Chabir R, et al. Diet culture and obesity in northern Africa. J Nutr 2001;131:887S–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang EJ, Chung HK, Kim WY, et al. Carbohydrate intake is associated with diet quality and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in U.S. adults: NHANES III. J Am Coll Nutr 2003;22:71–9. 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018449supp001.pdf (195.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018449supp002.pdf (236KB, pdf)