Abstract

Introduction

In Australia, societal and individual preferences for funding fertility treatment remain largely unknown. This has resulted in a lack of evidence about willingness to pay (WTP) for fertility treatment by either the general population (the funders) or infertile individuals (who directly benefit). Using a stated preference discrete choice experiment (SPDCE) approach has been suggested as a more appropriate method to inform economic evaluations of fertility treatment. We outline the protocol for an ongoing study which aims to assess fertility treatment preferences of both the general population and infertile individuals, and indirectly estimate their WTP for fertility treatment.

Methods and analysis

Two separate but related SPDCEs will be conducted for two population samples—the general population and infertile individuals—to elicit preferences for fertility treatment to indirectly estimate WTP. We describe the qualitative work to be undertaken to design the SPDCEs. We will use D-efficient fractional experimental designs informed by prior coefficients from the pilot surveys. The mode of administration for the SPDCE is also discussed. The final results will be analysed using mixed logit or latent class model.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is being funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant AP1104543 and has been approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC 17255) and a fertility clinic’s ethics committee. Findings of the study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and presented at various conferences. A lay summary of the results will be made publicly available on the University of New South Wales National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit website. Our results will contribute to the development of an evidence-based policy framework for the provision of cost-effective and patient-centred fertility treatment in Australia.

Keywords: reproductive medicine, infertility, stated preference discrete choice experiment, willingness to pay

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this study will be the first to measure and quantify preferences for fertility treatment for the general population and infertile individuals in Australia.

The study design is unique and capable of eliciting preferences from both the general population and individuals experiencing fertility treatment.

The results will contribute to the development of an evidence-based policy framework for the provision of cost-effective and patient-centred fertility treatment in Australia.

The stated preference discrete choice experiment surveys will be undertaken in Australia which could affect generalisability to other settings.

Introduction

One in six couples suffer infertility, causing significant personal suffering to possibly more than 50 million couples worldwide.1–3 Rates of infertility are predicted to increase with the trend to postpone childbearing, deteriorating sperm quality, and rising rates of obesity and some sexually transmitted diseases.4

Economic evaluations that consider outcomes of fertility treatment are scarce, mainly because the unique objective of fertility treatment is to create new life rather than extend or improve health-related quality of life, unlike other forms of medical care.5 The outcomes of fertility treatment are also broader than those traditionally considered in healthcare and include substantial non-health related, such as family formation, existential meaning and individual identity. Furthermore, process outcomes related to delivery of treatment, such as continuity of care, joint decision-making and convenience, are also important drivers of satisfaction with treatment.6–11

These multiple and varied outcomes do not usually have a market price and cannot all be captured and valued in a conventional quality-adjusted life year (QALY) framework.5 12–16 Fertility treatment involves multiple stakeholders, including the mother, father, donor and society, which further makes the QALY measure unsuitable.12 13 17–21 Despite supportive public funding of fertility treatment in Australia through its universal health insurance scheme (Medicare), societal and individual preferences for funding fertility treatment remain largely unknown. This results in a lack of evidence about willingness to pay (WTP) for fertility treatment by either the general population (the indirect funders through tax contribution) or infertile individuals (who directly benefit). Without estimates of the shadow price for fertility treatment, as expressed by WTP estimates, the economic value of fertility treatment and its cost-effectiveness are lacking to inform policy and resource allocation decision-making.12

Using stated preference discrete choice experiment (SPDCE) has been suggested as an appropriate method for evaluating broad outcomes of fertility treatment in monetary terms.13 15 22 23 This approach indirectly elicits WTP estimates for any treatment attributes (characteristics) without being restricted to health outcomes alone.

We outline a unique design of two separate but related SPDCEs to elicit treatment preferences from the general population and infertile individuals to indirectly estimate WTP values for the attributes and levels of fertility treatment. The general population sample will be representative of the Australian population which includes members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) community. Infertile individuals will be patients recruited from fertility clinics who may also include members of the LGBTIQ community who have access to a variety of treatment options such as donor and egg sharing programmes. To our knowledge, this study will be the first to measure and quantify preferences for fertility treatment for both the general population and infertile individuals.

Aims

The specific objectives of the study are to assess WTP values for fertility treatment from the general population and infertile individuals. The study will determine whether:

The current level of Medicare expenditure for fertility treatment in Australia is in line with the general population’s and individuals’ WTP for the treatment;

The general population’s WTP for fertility treatment varies by patient characteristics and family structures.

The general population’s and patients’ WTP for fertility treatment can be influenced by the attributes of treatment.

Methods and analysis

Overview of SPDCE approach

The SPDCE approach is an attribute-based measure of value which can capture broader aspects of an intervention, including outcomes not related to health, and process outcomes related to delivery of treatment.24 SPDCEs have a theoretical basis on random utility theory which assumes that individuals value an intervention based on the bundle of its attributes as a whole25 and that they prefer an intervention that gives them the highest level of satisfaction based on the individual attributes.26 In an SPDCE, respondents are presented with specially designed hypothetical scenarios of treatment programmes where at least one attribute of the treatment is varied systematically in terms of its levels. Individuals are asked to choose an option they prefer, including an ‘opt-out’. The extent to which respondents ‘trade-off’ one set of attributes against one another is assessed through logistic regression models.27 28 The dependent variable in the model represents the likelihood of choosing one alternative with specific attributes and levels over another. The independent variables are the attributes and levels of treatment. Heterogeneity can be accounted for using covariates or their specification in a mixed logit (MXL) or latent class (LC) models.29–31 When a cost attribute is included, it is possible to indirectly estimate WTP values for particular attributes of treatment.22 24 32 33

Crucial to the SPDCE process is the conduct of the following five stages: (1) identification of attributes for fertility treatment, (2) assignment of levels to these attributes, (3) development of an experimental design to define the choice alternatives to be presented to respondents, (4) development and administration of questionnaires to collect data and (5) data input and analysis of responses from the surveys.31 34–36 We are currently in the first stage of identifying attributes of fertility treatment. The whole study is estimated to take 18 months from June 2017 when ethical approval was obtained. In the following section, we summarise the steps involved in our planned SPDCE.

Qualitative component to inform the development of attributes and levels

The attributes and levels of the SPDCEs will be developed based on a qualitative component of the study which includes a literature review and focus-group discussions (FGDs).35 37–42 The latter will involve two distinct sample groups: general population and infertile individuals (n=8–16). The general population will be recruited using a poster advertisement placed on noticeboards in public places such as shopping centres and libraries, and an online classified advertisement placed on social media and advertising websites such as ‘Gumtree’. Infertile individuals will be recruited from a fertility clinic in Sydney through a poster advertisement which will be placed in the clinic. These participants will be a mix of those who are considering, currently using or have previously used fertility treatment.

For both population groups, individuals who are interested in participating in the FGD are asked to respond to the study advertisements by contacting the research team through email or telephone for more information. Following contact, a member of the research team will provide additional information on the purpose of the FGDs to ensure participants have adequate knowledge and understand what their participation would involve. At the same time, potential participants will be screened for eligibility. All participants must be aged 18 years or older, able to speak English, Australian citizens or residents, and with the ability to provide consent. There are no eligibility criteria related to gender or marital status. If they meet the set inclusion criteria, prospective participants will be asked to provide an email address for the researchers to send them an invitation with the details of the FGD and the participant information sheet and consent form (PISCF). Both FGDs will be facilitated by two researchers and will last approximately 1–1.5 hours. The discussions will be audio-recorded and later transcribed without any identifying information.

The FGDs will use a nominal group technique41 43–45 where a facilitator will ask participants to think about the important features of fertility treatment and whether the way it is provided might matter to them or other individuals when choosing one fertility treatment over another. Participants will be asked to silently generate a list of the attributes of fertility treatment. One participant at a time will be asked to state a single attribute to the group which will be recorded verbatim on a whiteboard. This process will continue until saturation after which attributes will be clarified and similar attributes grouped together by FGD participants. Following this, participants will be asked to rank order the identified attributes privately based on personal preferences for the attributes. In case the cost attribute is not identified during the FGDs, it will, nevertheless, be included to allow the indirect estimation of WTP through marginal rate of substitution (MRS).32 46–49

Selection of attributes and levels for the SPDCE

A comprehensive list of potential attributes and levels from this qualitative work will be broadly categorised into two groups: attributes related to the outcomes of treatment and attributes related to the process, delivery or provision of treatment.6 7 11 50–54 A consensus group of experts in fertility treatment will help synthesise the attributes, assign levels to the attributes (where they were not identified by the FGDs) and refine the wording for clarity. The number of attributes to include in the SPDCE model will be limited to eight each with two to four levels based on the rules-of-thumb used in many studies.34 40 55–57 Using too many attributes and levels increases the complexity of the choice tasks for respondents which may result in individuals not trading-off the attributes or in respondent fatigue.58 59

SPDCE design

The consolidated attributes and levels of fertility treatment will be used in the initial orthogonal fractional experimental design. This will define the choice alternatives for a pilot survey of both the general population and infertile individuals.49 This design will have no prior information about preferences for fertility treatment.49 Subsequently, the coefficients from the pilot surveys will be used as prior information to inform the construction of optimal or efficient fractional experimental designs for the final surveys of the two sample groups.57 60 61 The SPDCE designs will be unlabelled34 62 63 and will follow design principles stipulated by Huber and Zwerina.64 Ngene software will be used for constructing experimental designs.65

Questionnaire development and administration

The choice tasks in the SPDCE questionnaire for the pilot surveys will be similar for the two sample groups, developed using the output of the fractional experimental designs without prior information on preferences. These choice tasks will differ in the final surveys as they will be built using the coefficients obtained from the results of the pilot surveys which will differ between the two groups. The format of the questionnaire will follow guidelines which suggest the provision of an introduction; an explanation of the context of the survey, the attributes and their levels; an example of the choice task; an emphasis on respondents’ time commitment, and the importance of their participation and confidentiality.49 Respondents will be guided on where to direct any queries on the survey and how to proceed answering the choice questions. The questionnaire will also include additional follow-up questions which will include an evaluation of the level of difficulty of the choice tasks on a five-point scale of very easy, easy, okay, difficult and very difficult; and respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics.

The SPDCE questionnaire will be tested for face and theoretical validity. Face validity will be done with a small group of individuals to refine the phrasing and comprehension, while theoretical validity will be explored in the pilot surveys through sign and significance of the parameter estimates to ensure that they conform to a priori expectations, especially for the time or cost attribute which would normally show a monotonic relationship.66 Two additional choice sets will also be included to act as consistency and reliability checks.56 66 67 A consistency check is a theoretically dominant choice set on attribute-levels which is used to test the rationality of the respondents, while a reliability check is simply a reinsertion of a choice set from the experimental design to somewhere later in the design.

Sampling and recruitment

Sample size calculation in SPDCE studies has not been fully developed, with most studies still using the ‘rules-of-thumb’ or relying on the use of efficient experimental designs. This has the potential benefit of reducing CIs of parameter estimates in a SPDCE model, hence permitting the use of reduced sample sizes.57 68–70

A sample size of 20 respondents has been suggested as adequate to be able to estimate an SPDCE model.34 Previous studies have generally shown that sample sizes of 40–100 respondents may be sufficient for reliable statistical analysis.71 Orme69 proposes a total of 300 respondents for robust quantitative research and a minimum of 200 per group for subgroup analysis. This study will benefit from using sample sizes well above the rules-of-thumb and efficient experimental designs for the final surveys, in order to have robust results.

All surveys will be administered online with a sample size of 30 participants for pilot surveys of the general population and infertile individuals. Participants for both pilot surveys will be recruited using the same methods as used for the FGDs. For the two samples, interested participants will respond to the study advertisements by contacting researchers either by email or phone. Following screening for eligibility, potential participants will be emailed a survey invitation and PISCF with a link to the online pilot survey. By completing and submitting the survey, participants will be providing their consent.

The final survey for the general population will be administered by a commercial survey company, recruiting 3000 participants from a panel of the Australian population. Recruitment of infertile individuals will be through a fertility organisation’s clinics and a national infertility consumer organisation (n=250–300). Interested individuals will respond to the study advertisements by email or telephone and will be emailed the invitation and PISCF with a link to an online survey. Clicking on a link within the consent form will imply consent to start the survey, and they can withdraw at any time. Full consent will be deemed after they complete and submit the entire survey.

Data analysis plan

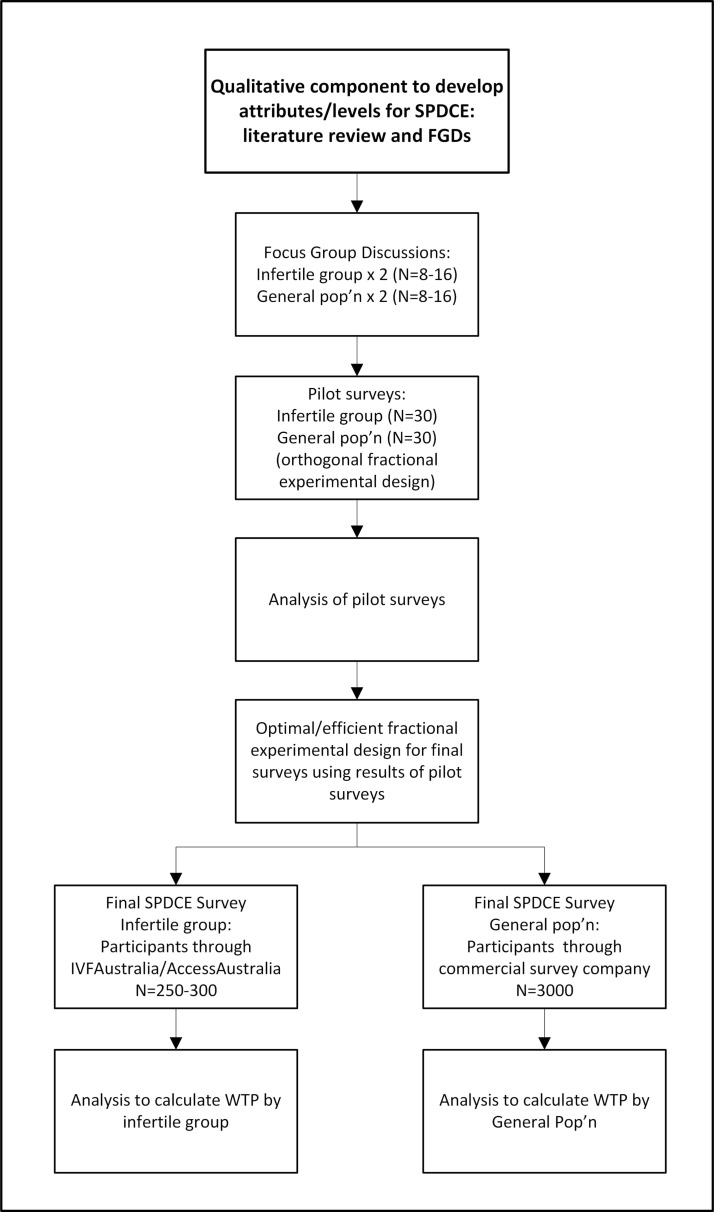

The responses from the SPDCE surveys will initially be analysed using logistic regression with a multinomial logit model in Stata V.14 or Nlogit software. To estimate WTP, the results of a MXL or LC model which account for preference heterogeneity will be used. The success rate, time and cost attributes of fertility treatment will be modelled as continuous variables in order to apply the MRS. Differences in preferences between individual groups will be explored through the interaction between the attributes or levels and the sociodemographic characteristics. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of activities for our study.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of activities. FGD, focus-group discussion; pop’n, population; SPDCE, stated preference discrete choice experiment; WTP, willingness to pay.

Ethics and dissemination

All participants will be provided with a PISCF before undertaking any study activity. There will be no incentive payment of any form to participants. Findings of the study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals and presented at various conferences. A lay summary of the results will be made available publicly on the University of New South Wales National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit website. The results will be used to contribute to the development of an evidence-based policy framework for the provision of cost-effective and patient-centred fertility treatments in Australia.

Limitations of SPDCE approach in the context of this study

The SPDCE approach offers great potential for informing policy and addressing resource allocation questions related to the provision of fertility treatment. However, there are a number of methodological limitations that are common to all SPDCEs. In the context of our study, the first challenge relates to selecting a limited number of attributes and levels that are both practically feasible to include in an SPDCE and define the fertility treatment. There are likely multiple attributes and levels that could influence choices of fertility treatment from the perspective of both the general population and patients. However, only up to eight each with two to four levels are ideal.34 56 Too many attributes and levels can affect the statistical quality of the SPDCE design, and result in too great a cognitive burden on respondents to answer an excessive number of choice sets.55 57

Furthermore, the SPDCE surveys will be undertaken in Australia which could affect generalisability to other settings. Australia is a developed country with a relatively supportive funding environment for fertility treatment through the universal insurance scheme (Medicare). Finally, the choices made by the participants based on the hypothetical scenarios presented in the SPDCE may not reflect real-life choices. However, the FGDs, careful development of the experimental design and analyses will minimise this risk, plus the comparison of the results of the SPDCE to the revealed preferences reflected by fertility treatment utilisation rates and government rebate will provide a mechanism for validating the results.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GMC and MS wrote the grant application. WB wrote the first draft of the protocol. WB, ND, MS and GMC contributed to the drafting and editing of the protocol and approved the final version.

Funding: This study is being funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant AP1104543.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The ethics approval was obtained from the university of New South Wales human research ethics committee (HEC 17255) and a fertility clinic’s ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, et al. . National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001356 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, et al. . International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1506–12. 10.1093/humrep/dem046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labett Research and Marketing. Fertility study: attitudes, experiences and behaviours of Australian general public. Lower Hutt, New Zealand: Fertility Society of Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, et al. . Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: taking control of your fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2013;11:66 10.1186/1477-7827-11-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly MP, Hoorens S, Chambers GM. ESHRE Reproduction and Society Task Force. The costs and consequences of assisted reproductive technology: an economic perspective. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:603–13. 10.1093/humupd/dmq013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarts JW, Huppelschoten AG, van Empel IW, et al. . How patient-centred care relates to patients' quality of life and distress: a study in 427 women experiencing infertility. Hum Reprod 2012;27:488–95. 10.1093/humrep/der386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Empel IW, Aarts JW, Cohlen BJ, et al. . Measuring patient-centredness, the neglected outcome in fertility care: a random multicentre validation study. Hum Reprod 2010;25:2516–26. 10.1093/humrep/deq219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cousineau TM, Green TC, Corsini E, et al. . Online psychoeducational support for infertile women: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2008;23:554–66. 10.1093/humrep/dem306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Empel IW, Nelen WL, Tepe ET, et al. . Weaknesses, strengths and needs in fertility care according to patients. Hum Reprod 2010;25:142–9. 10.1093/humrep/dep362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dancet EA, D’Hooghe TM, Sermeus W, et al. . Patients from across Europe have similar views on patient-centred care: an international multilingual qualitative study in infertility care. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1702–11. 10.1093/humrep/des061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mourad SM, Nelen WL, Akkermans RP, et al. . Determinants of patients' experiences and satisfaction with fertility care. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1254–60. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird D, Barri P, Bhattacharya S, et al. . Economic aspects of infertility care: a challenge for researchers and clinicians. Hum Reprod 2015;30:2243–8. 10.1093/humrep/dev163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlin N, Parkin D. Funding fertility: issues in the allocation and distribution of resources to assisted reproduction technologies. Hum Fertil 2003;6:S2–S6. 10.1080/1464770312331369153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan M. Should government fund assisted reproductive techniques? A study using willingness to pay. Appl Econ 1997;29:841–9. 10.1080/000368497326499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Wijngaard L, Rodijk IC, van der Veen F, et al. . Patient preference for a long-acting recombinant FSH product in ovarian hyperstimulation in IVF: a discrete choice experiment. Hum Reprod 2015;30:331–7. 10.1093/humrep/deu307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston RJ, Boyle KJ, Adamowicz Wiktor, et al. . Contemporary Guidance for Stated Preference Studies. J of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2017;4:319–405. 10.1086/691697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scotland GS, McLernon D, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. . Minimising twins in in vitro fertilisation: a modelling study assessing the costs, consequences and cost-utility of elective single versus double embryo transfer over a 20-year time horizon. BJOG: An Int J of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2011;118:1073–83. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratcliffe J. The economics of the IVF programme: a critical review: National Centre for Health Program Evaluation, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Brandeau ML. Evaluating Cost-effectiveness of Interventions That Affect Fertility and Childbearing: How Health Effects Are Measured Matters. Med Decis Making 2015;35:818–46. 10.1177/0272989X15583845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Versteegh MM, Brouwer WBF. Patient and general public preferences for health states: A call to reconsider current guidelines. Soc Sci Med 2016;165:66–74. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolan P, Edlin R. Is it really possible to build a bridge between cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis? J Health Econ 2002;21:827–43. 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan M. Using conjoint analysis to take account of patient preferences and go beyond health outcomes: an application to in vitro fertilisation. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:535–46. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00374-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musters AM, de Bekker-Grob EW, Mochtar MH, et al. . Women’s perspectives regarding subcutaneous injections, costs and live birth rates in IVF. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2425–31. 10.1093/humrep/der177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tockhorn-Heidenreich A, Ryan M, Hernández R. Discrete Choice Experiments : Facey KM, Ploug Hansen H, Single ANV, Patient Involvement in Health Technology Assessment. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2017:121–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ 1966;74:132–57. 10.1086/259131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior Zarembka P, Frontiers of econometrics: Academic Press, 1974:105–42. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Discrete Choice Experiments in a Nutshell : Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M, Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care. Springer Netherlands, 2008:13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanley N, Wright RE, Alvarez-Farizo B. Estimating the economic value of improvements in river ecology using choice experiments: an application to the water framework directive. J Environ Manage 2006;78:183–93. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spinks J, Chaboyer W, Bucknall T, et al. . Patient and nurse preferences for nurse handover-using preferences to inform policy: a discrete choice experiment protocol. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008941 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goossens LM, Utens CM, Smeenk FW, et al. . Should I stay or should I go home? A latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment on hospital-at-home. Value Health 2014;17:588–96. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lancsar E, Fiebig DG, Hole AR. Discrete choice experiments: A guide to model specification, estimation and software. Pharmacoeconomics 2017;35:697–716. 10.1007/s40273-017-0506-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan M, Kolstad J, Rockers P, et al. . How to conduct a Discrete Choice Experiment for health workforce recruitment and retention in remote and rural areas: a user guide with case studies: CapacityPlus World Bank and World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIntosh E, Clarke P, Frew E, et al. . Applied Methods of Cost-Benefit Analysis in Health Care: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661–77. 10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kløjgaard ME, Bech M, Søgaard R. Designing a Stated Choice Experiment: The Value of a Qualitative Process. J of Choice Modelling 2012;5:1–18. 10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70050-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods: analysis and applications: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, et al. . Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ 2012;21:730–41. 10.1002/hec.1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guttmann R, Castle R, Fiebig DG. Use of discrete choice experiments in health economics: An update of the literature. CHERE WORKING PAPER 2009/2. Sydney: University of Technology, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kragt ME. Evidence-based Research in Environmental Choice Experiments. Working Paper 1310. Australia: School of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Western Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. . Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiligsmann M, van Durme C, Geusens P, et al. . Nominal group technique to select attributes for discrete choice experiments: an example for drug treatment choice in osteoporosis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:133 10.2147/PPA.S38408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vass C, Rigby D, Payne K. The Role of Qualitative Research Methods in Discrete Choice Experiments. Med Decis Making 2017;37:298–313. 10.1177/0272989X16683934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey N, Holmes CA. Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract 2012;18:188–94. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kremer IE, Evers SM, Jongen PJ, et al. . Identification and prioritization of important attributes of disease-modifying drugs in decision making among patients with multiple sclerosis: A nominal group technique and best-worst scaling. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164862 10.1371/journal.pone.0164862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:655–62. 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlsson F. Non-Market Valuation: Stated Preference Methods: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greiner R, Bliemer M, Ballweg J. Design considerations of a choice experiment to estimate likely participation by north Australian pastoralists in contractual biodiversity conservation. J of Choice Modelling 2014;10:34–45. 10.1016/j.jocm.2014.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan M, Gerard K, Watson V, et al. . Practical Issues in Conducting a Discrete Choice Experiment In: Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M, eds Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care: Springer Netherlands, 2008:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied Choice Analysis. 2nd edn United Kingdom: Cambridge University Presss, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Empel IW, Dancet EA, Koolman XH, et al. . Physicians underestimate the importance of patient-centredness to patients: a discrete choice experiment in fertility care. Hum Reprod 2011;26:584–93. 10.1093/humrep/deq389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dancet EA, Nelen WL, Sermeus W, et al. . The patients' perspective on fertility care: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:467–87. 10.1093/humupd/dmq004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palumbo A, De La Fuente P, Rodríguez M, et al. . Willingness to pay and conjoint analysis to determine women’s preferences for ovarian stimulating hormones in the treatment of infertility in Spain. Hum Reprod 2011;26:1790–8. 10.1093/humrep/der139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porter R, Kissel C, Saunders H, et al. . Patient and nurse evaluation of recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone administration methods: comparison of two follitropin injection pens. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:727–35. 10.1185/030079908X273291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dancet EA, D’Hooghe TM, Spiessens C, et al. . Quality indicators for all dimensions of infertility care quality: consensus between professionals and patients. Hum Reprod 2013;28:1584–97. 10.1093/humrep/det056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfarr C, Schmid A, Schneider U. Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Understand Preferences in Health Care. Health Care Provision and Patient Mobility: Health Integration in the European Union, 2014:27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kjær T. A review of the discrete choice experiment-with emphasis on its application in health care: Syddansk Universitet Denmark 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rose JM, Bliemer MCJ. Constructing efficient stated choice experimental designs. Transp Rev 2009;29:587–617. 10.1080/01441640902827623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lloyd AJ. Threats to the estimation of benefit: are preference elicitation methods accurate? Health Econ 2003;12:393–402. 10.1002/hec.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ 2012;21:145–72. 10.1002/hec.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Domínguez-Torreiro M. Alternative experimental design paradigms in choice experiments and their effects on consumer demand estimates for beef from endangered local cattle breeds: An empirical test. Food Qual Prefer 2014;35:15–23. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, et al. . Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: A report of the ispor conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health 2016;19:300–15. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doherty E, Campbell D, Hynes S, et al. . Examining labelling effects within discrete choice experiments: an application to recreational site choice. J Environ Manage 2013;125 94–104. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoyos D. The state of the art of environmental valuation with discrete choice experiments. Ecological Economics 2010;69:1595–603. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huber J, Zwerina K. The importance of utility balance in efficient choice designs. J of Marketing Research 1996;33:307 10.2307/3152127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choicemetrics. Ngene 1.1.2: User manual and reference guide: Choice Metrics Pty Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ryan M, Major K, Skåtun D. Using discrete choice experiments to go beyond clinical outcomes when evaluating clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2005;11:328–38. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carlsson F, Mørkbak MR, Olsen SB. The first time is the hardest: A test of ordering effects in choice experiments. Journal of Choice Modelling 2012;5:19–37. 10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70051-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Efficiency benefits of choice model experimental design updating: a case study. Conference(53rd) Cairns, Australia: Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society.2009. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orme B. Getting Started with Conjoint Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research Madison. Wisconsin: Research Publishers, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, et al. . Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: A practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373–84. 10.1007/s40271-015-0118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Bekker-Grob EW, Bliemer MC, Donkers B, et al. . Patients' and urologists' preferences for prostate cancer treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer 2013;109:633–40. 10.1038/bjc.2013.370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.