Abstract

Introduction

Hospital readmissions within 30 days are a healthcare quality problem associated with increased costs and poor health outcomes. Identifying interventions to improve patients’ successful transition from inpatient to outpatient care is a continued challenge.

Methods and analysis

This is a single-centre pragmatic randomised and controlled clinical trial examining the effectiveness of a discharge follow-up phone call to reduce 30-day inpatient readmissions. Our primary endpoint is inpatient readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge censored for death analysed with an intention-to-treat approach. Secondary endpoints included observation status readmission within 30 days, time to readmission, all-cause emergency department revisits within 30 days, patient satisfaction (measured as mean Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores) and 30-day mortality. Exploratory endpoints include the need for assistance with discharge plan implementation among those randomised to the intervention arm and reached by the study nurse, and the number of call attempts to achieve successful intervention delivery. Consistent with the Learning Healthcare System model for clinical research, timeliness is a critical quality for studies to most effectively inform hospital clinical practice. We are challenged to apply pragmatic design elements in order to maintain a high-quality practicable study providing timely results. This type of prospective pragmatic trial empowers the advancement of hospital-wide evidence-based practice directly affecting patients.

Ethics and dissemination

Study results will inform the structure, objective and function of future iterations of the hospital’s discharge follow-up phone call programme and be submitted for publication in the literature.

Trial registration number

NCT03050918; Pre-results.

Keywords: discharge phone call, pragmatic clinical trial, hospital readmission, transition of care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Single-centre trial conducted at a tertiary care referral centre with inclusion limited to the general medicine population to improve generalisability.

Designed to demonstrate effectiveness with pragmatic concessions (including an anticipated 30% intervention delivery rate) limiting our ability to determine efficacy.

The need to inform a time-sensitive clinical practice decision in the context of clinical equipoise led to the appropriate selection of more pragmatic and less explanatory design elements.

Waiver of consent and use of clinical informatics resources permitted study feasibility.

Potentially obtaining external readmission data from a health information exchange is a data access innovation overcoming a traditional hospital readmission research limitation.

Introduction

In 2010, the US Affordable Care Act tasked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to implement financial penalties for hospitals with excessive 30-day inpatient readmission rates.1 Penalties are withheld reimbursements for select diagnoses designed to incentivise hospital to support higher-quality discharge care transitions.2 In 2016, penalties amounting to over $500 million were withheld from 2597 (47%) US hospitals.3 In responses to this national quality improvement challenge Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) launched a nursing-based discharge follow-up phone call programme to support more successful inpatient-to-outpatient transitions and improve patient satisfaction. Prior studies have attempted to determine whether a phone call can reduce hospital revisits. The literature is limited as existing studies target very specific patient populations, are of insufficient design quality, or evaluate follow-up calls as part of a larger care bundle.4–16 As our hospital system piloted this programme, we found it crucial to rigorously quantify the impact of the intervention before it is launched as a health system-wide programme. An impactful intervention could be adopted by other hospitals as an investment in quality, safety and more effectively stewarding institutional resources. Our study team was challenged to embed a high-quality clinical trial, specifically randomisation and blinding, into the operations of daily inpatient care without disturbing the workflow of medical providers. Our null hypothesis is a follow-up phone call will have no impact on 30-day hospital readmissions. Here, we discuss how we appropriately included pragmatic design elements for this superiority trial making the study practicable and results more timely than an explanatory trial approach.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is a single-centre pragmatic randomised and controlled clinical trial examining the effectiveness of a discharge follow-up phone call on 30-day inpatient readmissions. The study began on 13 February 2017 with a 1-week informatics run-in period to assure the fidelity of our study dataflow as embedded into real-time clinical care at VUMC (figure 1). Trial initiation was on 20 February 2017 when enrolment began. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT03050918). The unit of study is each inpatient hospitalisation, so a revisit after 30 days, but within the study period is included as a new observation.17 We requested a waiver of consent from our IRB given several considerations. Usual care for patients discharge from the hospital includes reviewing documentation noting their new medication regimen with attention to changes, follow-up appointment scheduling plan or dates, education on new diagnoses and symptoms for which to seek care. The trial examines the effectiveness of a newly established but existing clinical programme calling patients within 7 days of hospital discharge to support successful transition to outpatient care. As a result the intervention is in active use, but its impact is unclear, thus demonstrating equipoise. The care to be received by control and intervention group patients is within the scope of acceptable practice, and poses minimal risk to patients exposed or withheld from the programme.18 Consenting control group patients would have been logistically impracticable given available resources. In addition, the informed consent process would involve education on the risk of readmission targeted by the intervention. This could bias study results by prompting patient action to mitigate the risk and consequently make the results, for an important clinical question, uninterpretable.19 Waiver of consent was granted. We randomise two clinical practice options—discharge with and without a follow-up call—to best examine the effectiveness of the programme under actual clinical care conditions. Our study protocol reporting is adherent to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) Groups’ guidelines for pragmatic clinical trials and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidance for interventional trial protocols.20 21

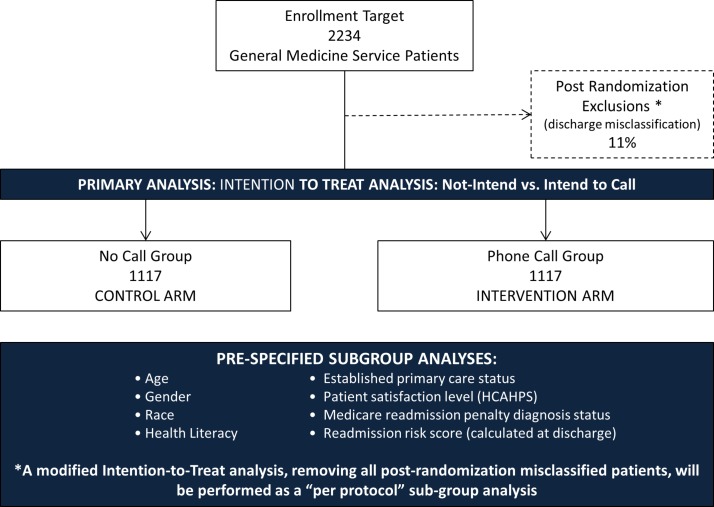

Figure 1.

Study design schematic and enrolment projection. HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Outcomes

Our primary endpoint is inpatient readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge censored for death. We considered the composite outcome of 30-day inpatient readmission or death. However, we found 30-day mortality rates in our general medicine population in the year prior to be 2.6%. This suggests death is not a significant competing risk and informative censoring22 would be a minimal issue. Secondary endpoints include observation status readmission within 30 days, time to readmission, all-cause emergency department (ED) revisits within 30 days, patient satisfaction (measured as mean Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores)23 and 30-day mortality. Exploratory endpoints include the need for assistance with discharge plan implementation among those randomised to the intervention arm and reached by the study nurse, and the number of call attempts to successful intervention delivery.

Study population

We include all hospital adult inpatients discharged home from a general medicine service in our urban tertiary care hospital. We exclude inhospital deaths since the study outcome was not applicable, patients who left the hospital against medical advice due to the limited opportunity for discharge planning, and those transferred to a skilled nursing facility or another hospital since they were not discharged with the expectation their health maintenance will be managed from home and supported by clinic-based outpatient care. To improve the generalisability of our study findings to the typical general medicine patient population, we did not include those discharged from our medical subspecialty services. Our hospital serves as a referral centre for complex cases from a wide catchment. In addition, the patients admitted to a subspecialty service are those requiring direct subspecialist care. As a result, our subspecialty service patients may have or require discharge planning not provided in a typical hospital setting.

Recruitment

We identify eligible patients via a custom programmed discharged patient report generated from the medical centre’s electronic health record (EHR) admission, discharge and transfer (ADT) system each weekday morning. This auto-generated report applies our inclusion and exclusion criteria using EHR ADT data documented during clinical care, and loads as a spreadsheet to a secure folder accessible to select study team members. It includes patient name, admission date, discharge date, discharging hospital provider team, age, address, primary phone number and primary care doctor.

Study procedure

Randomisation and blinding

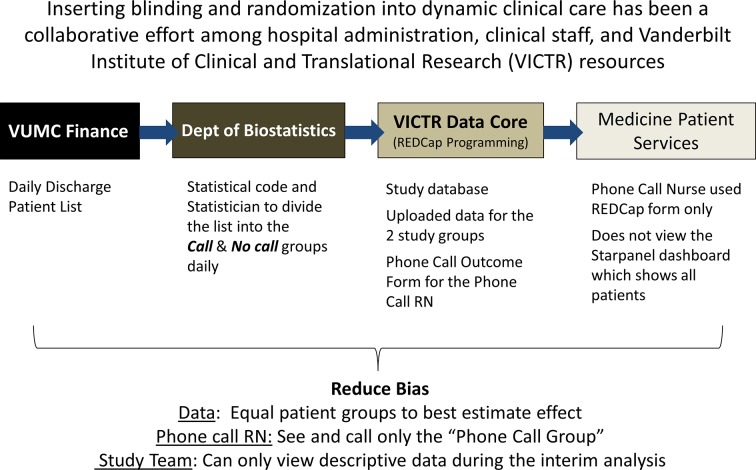

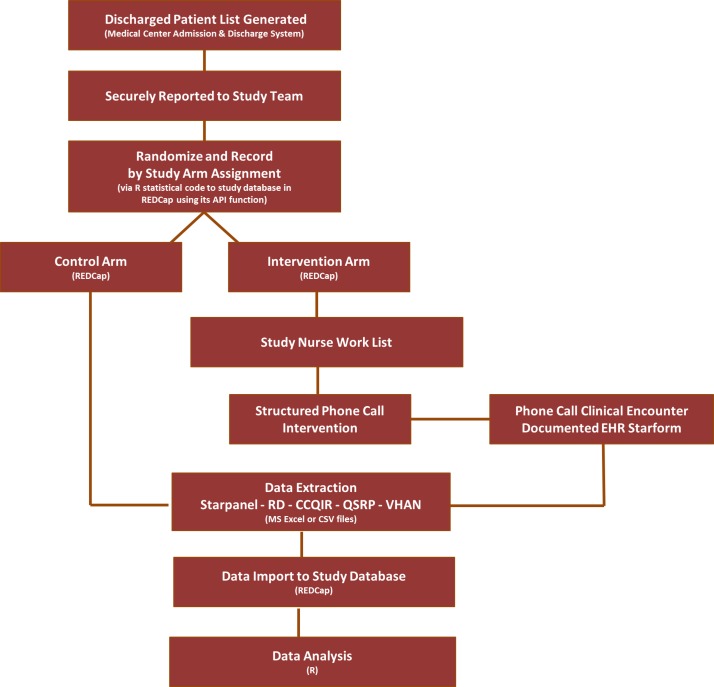

Each weekday morning the list of eligible patients is randomised by a study team member (HD, DB or MYABY) using the statistical program, R V.3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015, https://www.R-project.org) random sample function with a stable seed to promote reproducibility (see online supplementary I). The study database was created in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capitulation, https://www.project-redcap.org/), a secure web-enabled research data capture system designed to protect and secure protected patient health information.24 REDCap’s application program interface was used to upload those randomised to each study arm (by R) into separate study databases. The study registered nurse (Phone Call RN, ST) was blinded to the control arm database, but used the intervention arm database as her work list (figure 2). A form was created in the intervention database to display the name, phone number, address, admission data, discharge date, discharge service, primary care doctor and hours since discharge in a user-friendly format to aid the Phone Call RN’s workflow (online supplementary II). This replaces a similar discharge dashboard within the EHR that was built to support the hospital discharge phone call programme. Constructing the intervention database form in REDCap was required to blind the Phone Call RN to the control group due to EHR information technology limitations making us unable to randomise or blind the existing dashboard. The REDCap form looks different in structure, but is identical in function while including only intervention group patients.

Figure 2.

Operationalising randomisation and blinding within dynamic hospital care. REDCap, Research Electronic Data Capitulation; RN, Registered Nurse; VICTR, Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research; VUMC, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

bmjopen-2017-019600supp001.pdf (408.1KB, pdf)

Postrandomisation exclusions

During the study design phase, we examined a historical cohort of patients who would have met our inclusion criteria and we found the discharge status of patients in our ADT system was not always correct. Chart review and discussion with physician and nursing staff indicated this occurred when there are late changes to the anticipated disposition plan, when the patient leaves the hospital before the care plan can be finalised, or during busy periods when non-care team members are proactively assisting with the discharge process. To permit a secondary per-protocol analysis, the Phone Call RN reviews the chart of each eligible patient to confirm they were truly discharged home. If this was not the case, the patient is identified as ineligible for a call, excluded from intervention delivery, but retained in the study for analysis. This same discharge verification process was repeated (by MCB) in the control arm to ensure balance between study arms (figure 1).

Discharge plan review

After confirming the discharge disposition, the Phone Call RN reviews the medical record to determine what was expected to occur after hospital discharge, including medication changes, follow-up appointments, education for new diagnoses and symptoms for which to seek urgent care. The review provides a reference point from which to assess the patient’s understanding and ability to ‘teach back’25 26 each element of the care plan.

Intervention delivery

The phone call intervention was designed to be consistent with the existing hospital programme. It is a semistructured discharge phone call assessment (online supplementary III) delivered by the Phone Call RN. The Phone Call RN (ST) completed institutional training on discharge health coaching; interpreting discharge care plan documentation in the hospital EHR and methods to contact discharge teams, visiting health assistance, pharmacists for assistance, durable medical equipment vendors and follow-up providers. A first call attempt is made within 72 hours of discharge on weekdays. If there is no answer, up to four call attempts are made until 7 days postdischarge.

The semistructured script is used to guide a verbal clinical assessment obtaining information on potential causes of hospital readmission that can be identified and addressed to support a stable transition to outpatient care. Following the methods of health coaching,25 26 the phone call focuses on assessing the patient’s knowledge of their discharge diagnosis, discharge medication plan with attention to changes, follow-up appointments and actualisation of anticipated discharge supports (ie, acquisition of durable medical equipment, visiting health assistance and medication procurement). Patients are asked to teach back their discharge plan for these three domains. If any knowledge or care transition gaps are identified, the Phone Call RN provides re-education, and determines if additional discharge plan supports are needed. Additional supports include facilitating durable medical equipment acquisition, making a home health connection, referral to a primary care provider, referral to an ED, engagement of case management or social work assistance, medication education, medication changes, request for pharmacist assistance, request for other provider assistance, follow-up appointment reminders, follow-up appointment scheduling, providing self-care teaching (wound care, diet, activity, etc).

A focused review of symptoms is conducted to identify conditions that could benefit from early attention including potential medication side effect, care plan failure or new symptoms requiring provider evaluation. Depending on the issue identified, the Phone Call RN can engage the discharging provider, primary care doctor, hospital pharmacist or follow-up provider in addressing this medical need. When a provider cannot be contacted or identified for concerning symptoms, patients are referred to an urgent care facilities or ED to reconcile symptoms with the discharge status.

Patients in both the control and intervention arms may be contacted by non-study discharge follow-up care teams involved in their care as consultants or their primary care home as part of routine care. This may dilute our intervention effect, but replicates implementation scenario of real-world care.

Data collection

Patient and initial visit data

Patient visit data are obtained from the hospital clinical data repository, the Research Derivative,27 curated by a Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Institute (VICTR) data management team. Our study team will share enrolled patients’ date of service, medical record number and hospital visit encounter number for the Research Derivative programmers to pull patient demographic, comorbidity, initial hospital visit and discharge data. All data are uploaded to our study REDCap database.

Intervention data

The outcome of each call attempt and intervention delivery encounter is recorded directly in the REDCap database. Prior to the study, the Phone Call RN was simultaneously documenting the outcomes of her calls (failures to reach patients and assistance provided to reached patients) in an administrative Microsoft Excel file used for daily reporting to supervisors. She will continue to complete her clinical documentation in the EHR as a clinical note. We, however, replaced her spreadsheet by adding her data collection fields into the intervention data collection form describe above (see online supplementary II). At the end of each work day, she downloads the call data from the intervention arm database as a Microsoft Excel file that looks identical to her prior spreadsheet. This permits consistent and maximal capture of intervention data within the study database without placing an additional data collection burden that could reduce her call attempt frequency and intervention delivery rate.

Revisit data

We pull data related to any inpatient, observation or ED revisit within 30 days to our hospital from the EHR including admitting and discharge diagnoses. This is done at 45 days to permit capture of delayed clinical documentation. It also permits us to monitor any readmissions, occurring shortly after the standard 30-day window for our primary outcome, as part of our safety analysis. If there were a significant number of readmissions just after 30 days, we could achieve acceptable 30-day readmission performance. The binary outcome measure could mask a potential care quality issue occurring just beyond the boundary of measure. The additional 15 days permit the evaluation of this potential phenomenon. Patient satisfaction data are retrieved from the hospital Quality and Patient Safety Office at 60 days postdischarge. This follow-up interval was selected due to the historical maximum return rate of 27% being achieved at this follow-up period at our institution.

Existing readmission penalties are not limited to patients readmitted to the original facility. A readmission reduction in our intervention arm could be attributed to shifting readmissions to an outside hospital more closely associated with the patient’s outpatient care base. Attempting to surmount this problem was a priority given the wide catchment area of our tertiary care hospital. Acquiring external readmission data in a timely fashion is a major challenge given limited data sharing among hospitals and 2–3 year data lags for curated national databases including National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Nationwide Emergency Department Sample) and Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result Medicare databases.

Given the need for a more timely result to inform institutional practice, we recognised this limitation and primarily planned to use provider documented EHR readmission data. Vanderbilt, however, is a hub for a Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute sponsored programme to develop a health information exchange (HIE) within a regionalised health community called The Vanderbilt Health Affiliate Network (VHAN).28 Initial data sharing began shortly before our study and involved three area hospitals. Despite hospital referral patterns suggesting these hospitals were not a major source of our referred patients, we are pursuing this unique opportunity to obtain this external and typically unavailable data. VHAN is not yet organised for research data requests. This study is being used as a prototype to develop interinstitutional data sharing agreements. We are attempting to coordinate the transfer of ADT data into the HIE to meet our study timeline. The success of this effort is to be determined.

Mortality data

We initially planned to obtain 30-day mortality data from our EHR which included deaths documented by institutional providers and the National Technology Information Services Death Master File29 30 updated in our EHR with a 6-month data lag. Due to national regulatory changes, this data update became unavailable. Our alternative approach is to account for delayed notification and documentation with a 120-day window to assess 30-day mortality.

Sample size considerations

Using data for general medicine inpatients from the prior year, we estimate approximately 3048 patients will be eligible for the study over a 7-month study period with 1:1 randomisation. Based on our experience with the current pilot, we have planned for a 30% intervention delivery rate (see figure 1). We expect this will be higher since 1:1 randomisation will reduce the Phone Call RNs workload by 50% enabling more call attempts per patient, thus increasing the likelihood of call success.

Study length and timeline

An informatics run-in period began on 7 February 2017 to test the integrity of the randomisation and blinding procedure (see figure 2) and data collection plan (see figure 3). Official study enrolment began on 20 February 2017. We will obtain interim impact estimates of the discharge phone call intervention at 50% enrolment estimated to occur in July 2017 (3.5 months), and will conduct the definitive analysis at 100% enrolment expected in October 2017 (7 months). Data collection and the study analysis will account for a 30-day readmission follow-up and the 45-day safety evaluation window. A preliminary analysis is expected in November 2017 after the database is cleaned and locked. We will add external readmission (if available) and mortality data in March of 2018.

Figure 3.

Discharge phone call study data sources and flow. API, application program interface; CCQIR, Center for Clinical Quality and Implementation Sciences Research; CSV, comma separated value formatted file; EHR, electronic health record; QSRP, Quality Safety and Risk Prevention; RD, Research Derivative; REDCap, Research Electronic Data Capitulation; VHAN, The Vanderbilt Health Affiliate Network.

Data confidentiality, sources and sharing

Only key study personnel will have access to the full study dataset which will be maintained in REDCap. All data for this study are either documented by the Phone Call RN or sourced directly from the EHR data repository. A de-identified version of the study database will be made available to other investigators on request for IRB-approved clinical research.

Data quality and safety monitoring

The interim analysis will be conducted by an independent biostatistician (LW) and Data Quality and Safety Officer (TH). The results will be reviewed by a three member Safety Monitoring Committee including our Data Quality and Safety Officer; the hospital Chief Executive Officer; and Chief Quality, Patient Safety and Risk Prevention Officer. Given the minimal risk of the intervention, there are no stopping rules. In addition to the study data analysis, the Safety Committee will review (1) a 10% sample of the Phone Call Nurse’s daily reports to her supervisors which is an element of clinical care reporting and (2) a summary of potential safety concerns from the office overseeing this clinical programme, the Medicine Patient Care Centre. The study team will remain blinded to outcome-associated results.

Analysis plan

General approach

The primary analysis will examine our primary outcome and secondary outcomes via an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis where comparisons will be made between the two study arms. We will follow with a secondary modified ITT (mITT) analysis of patients remaining after our postrandomisation exclusions to permit a per-protocol analysis. We will consider each revisit beyond 30 days as an independent event during which the patient could be re-enrolled and randomised again to either study arm. This is consistent with the methodology of the US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.17 The two primary statisticians used a dummy assignment variable to create the code to run the analyses. One-third non-blinded statistician will run the code with the real assignment variable replacing the dummy variable. This approach will be used for both the interim and final statistical analyses to reduce the potential for bias. Subgroup analyses will examine outcome differences by treatment assignment, age, gender, race, highest educational attainment, health literacy, established primary care status, patient satisfaction level, Medicare readmission penalty diagnosis status and readmission risk score calculated at discharge as part of routine care at VUMC. Lastly, among patients in the intervention arm who are called and reached, we will use descriptive statistics to quantify the need for patient assistance with discharge plan implementation.

Statistical analysis

In our univariate analysis, differences among patient characteristic groups will be assessed using the continuity corrected χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous outcomes and the Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical outcomes. In our multivariate analysis, we will examine the relationship between treatment assignment and our secondary endpoints using logistic regression. The study is not powered for a time-to-event analysis; however, we will explore time to readmission using the Cox proportional hazard model to understand when readmissions occur. In order to provide hospital leadership with preliminary efficacy data, we will perform the interim analysis at 50% enrolment (approximately 3.5 months) followed by the final analysis after achieving 100% enrolment. We have a prespecified α level of significance of 0.05 with penalties for the mid-study interim analysis per the O’Brian-Fleming alpha- spending function allowing for an α-significance level of 0.005 for the interim and 0.048 for the final analyses.

Power calculation

The study design is targeted to achieve a minimum of 80% power before October 2017 (see table 1). Given the 0.048 α level for our final analysis, and controls anticipated to have a 13.52% readmission rate based on estimates, this requires approximately 320 patients enrolled per month (n=2234). We assessed this enrolment target as feasible after observing there were approximately 508 eligible patients per month based on medical centre data collected from the year prior. We noted approximately 11% of these patient would need to be excluded from the mITT analysis after randomisation due to mis-categorised hospital discharge status affecting study eligibility reducing potential monthly enrolment to 452 (n=3164 or 1582 patients per arm). This 11% may be balanced if the hospital continues to experience its 11% annual growth in inpatient admissions, and opens a total of 45 new general medicine beds as scheduled to occur in months 3 and 6 of our study. In table 1, we illustrate conservative and ambitious enrolment scenarios with estimates for 80% and 90% power. Considering we have one Phone Call Study Nurse and will miss enrolment days for paid time off or sick days, we opted for a more conservative power target and detectable differences of 80% and 3.9%, respectively. This carries an associated enrolment of 1117 patent per arm (n=2234 or 11 patients per day).

Table 1.

Power and sample size scenarios

| Conservative | Ambitious | |||

| Control group readmission rate* | 13.52% | 13.52% | 13.52% | 13.52% |

| Intervention group readmission rate | 9.60% | 9.10% | 10.20% | 9.70% |

| Power | 80% | 90% | 80% | 90% |

| Detectable difference | 3.9% | 4.4% | 3.3% | 3.8% |

| Projected study sample size | 1117 | 1117 | 1582 | 1582 |

Two-group X2 test of equal proportions (equal n’s), two-sided test, final analysis α=0.048.

*Historical Vanderbilt University Medical Center readmission rates.

Discussion

We were challenged to design a high-quality clinical trial while providing a definitive yet timely result to inform hospital clinical practice without disturbing active clinical care. Our research team has had to maintain high expectations while executing a pragmatic plan.31 The engagement of administrative leaders as members of our study team has heightened the collaboration between clinical research and hospital operations. Hospital leadership has justified being more patient than administrative practice typically allows in anticipation of high-quality results. If a benefit is demonstrate, it can be expected to translate well as a clinical care programme since it was tested in the context of real-world clinical practice.

More robust results with randomisation

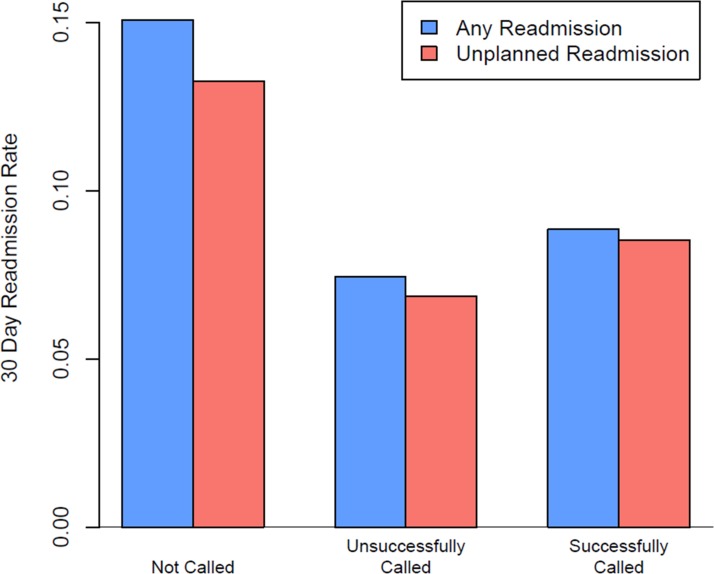

The hospital’s original phone call programme analysis compared readmission rates in patients not called, those called by the Phone Call Nurse and reached, and those called and not reached (figure 4). The results demonstrated lower readmission rates in those who we attempted to call, but never reached. Patients in the three groups, however, were not the same (table 2). Specifically, those called and reached were younger, included fewer whites, had lower acuity visits (lower Case Mix Index), included more transfers from an outside hospital, and were more often admitted from the ED. Patients not called had longer mean hospital length of stay (by 1.6 days), included more black patients, and were most likely to be admitted via the ED. University research leadership noted that blinding and randomisation within a clinical trial would produce two groups of patients with a near equal distribution of known and unknown characteristics, thus controlling for the confounding factors. Subsequent discussions led to the commission of this study.

Figure 4.

Non-randomised pretrial 30-day readmission rates by phone call status.

Table 2.

Distribution of patient characteristics from the non-randomised pretrial observational study of the phone call programme and readmission rates

| Not called (n=16 096) | Called but not reached (n=10 749) |

Called and reached (n=8447) | |

| Any readmission within 30 days* | 15.1 (2425) | 7.4 (171) | 8.8 (747) |

| Unplanned readmission within 30 days* | 13.3 (2133) | 6.9 (158) | 8.5 (719) |

| Gender (male)* | 48.1 (7742) | 41.7 (960) | 46.5 (3932) |

| Race* | |||

| White | 79.0 (12 711) | 77.5 (1785) | 80.5 (6801) |

| Black | 15.9 (2561) | 14.9 (342) | 14.1 (1192) |

| Other | 1.7 (280) | 1.9 (44) | 1.7 (142) |

| Unknown | 3.4 (544) | 5.7 (131) | 3.7 (312) |

| Age† | 50.8 (19.5) | 45.9 (18.5) | 52.6 (182) |

| Hospital length of stay | 5.8 (7) | 4.2 (4.7) | 4.2 (4.6) |

| Case Mix Index‡ | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.9 (2.0) | 2.2 (2.3) |

| Transferred from another hospital* | 18.7 (3017) | 21.1 (485) | 17.4 (1470) |

| Admission from the emergency department* | 66.8 (10 756) | 59.3 (1366) | 44.4 (3752) |

Bold value indicates values with notable differences when compared to the other groups.

*Percentage and number of patients.

†Mean and SD.

‡Case Mix Index is a complex measure of patient illness level and the intensity of services received during a hospital stay.

Learning healthcare partnership

VICTR and the hospital have recently engaged in a Learning Healthcare System32 partnership where clinical practice informs our research and research directly informs practice. Our trial is a pilot for the Learning Healthcare System Platform, a centre within the Institute to aid the development of high-quality pragmatic studies and timely study completion through the provision of resources, expert consultation and leadership facilitation. The platform will permit us to tackle significant gaps that arise between acquiring scientific evidence and the implementation of this evidence to advance healthcare delivery towards the goal of improving individual and population health. In some cases, existing evidence is not implemented. In the case of our study, there is an unmet need for evidence despite the need to develop appropriate clinical practice. Timeliness is a critical quality for studies to most effectively inform hospital clinical practice. Improving health and healthcare requires careful focus on both the content and process of care. Bolstering learning healthcare will be part of the solution.

Enabling pragmatic design elements

Enabling features of our study that can be considered to advance work in this area include waiver of consent, defining a feasible yet generalisable study population to produce results that can be translated to diverse care environments, engaging clinical informatics with clinical and statistical partners to facilitate data capture from the EHR, considering whether postrandomisation exclusions would contribute or diminish generalisable results, employing sample size considerations and power calculations that include hospital administrative projections while maintaining conservative enrolment targets. More broadly, we have focused on the effectiveness of our intervention under real-world conditions and limitations, rather than efficacy. This involves accepting potential contamination of our effect from non-study-related usual care. We expect that these factors will be distributed evenly among intervention and control patients by randomisation. They may potentially dilute the intervention effect. We expect our large sample size will provide enough power to detect a clinically meaningful effect.

Ethics and dissemination

Our hospital leadership awaits the final results. We have their commitment that study results will directly affect hospital practice. Study conclusions will inform the structure, objective and function of future iteration of the discharge follow-up phone call programme and be submitted for publication in the literature. The completion of large trials embedded into clinical practice that produce timely results can bridge the need for robust analyses and early answer to guide dynamic clinical practice decisions. Moreover, this type of prospective pragmatic study empowers the advancement of hospital-wide evidence-based practice directly affecting patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the following individuals for their administrative support for this study: Emily Bruer, Katie Worley, Brittney E Jackson, Christina Kampe, Adam Lewis, Becky Jerome, Paul Harris, Deede Wang, Kathryn Goggins, Lara Meade and Jill Pulley.

Footnotes

Contributors: MYABY is the principal investigator leading study design and implementation. HD is the primary statistician for the project. DB directly supervises data analysis and statistical plan implementation, and contributed to the study design. MMH contributed to the intervention design, study nurse training and is actively involved in study implementation. CLG is the scientific research coordinator for the study via the Learning Healthcare System Platform. SK contributed to study design and the analysis plan. NC contributed to the study design, implementation plan and the continued engagement of hospital leadership to support study implementation through completion. SM is the study nurse delivering the phone call intervention. MCB contributed to the study design and data collection. JM contributed to the study design. FEH provided senior guidance on the study design and the analysis plan. TH serves as the study safety officer and contributed to the study design, statistical analysis plan and leading the blinded interim analysis along with LW who is the study’s non-blinded statistician. GB provided senior scientific oversight for all aspects of the study. All authors reviewed and contributed to the final form of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the US National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant numbers 5UL1TR000445 and 1UL1TR002243; and a National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant numbers 5K12HL109019 and 1K23HL133477. The NIH is located in 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, et al. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1543–51. 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)”. AHRQ, CMS.gov https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html (accessed 25 Aug 2017).

- 3.American Hospital Association. Fast facts on US hospitals. 2017. http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml (accessed 25 Aug 2017).

- 4.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffman M. Health coaching: a new and exciting technique to enhance patient self-management and improve outcomes. Home Healthc Nurse 2007;25:271–4. 10.1097/01.NHH.0000267287.84952.8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huffman MH. HEALTH COACHING: a fresh, new approach to improve quality outcomes and compliance for patients with chronic conditions. Home Healthc Nurse 2009;27:490–6. 10.1097/01.NHH.0000360924.64474.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaban RB, Weissman JS, Samuel PA, et al. Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: a randomized controlled study. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1228–33. 10.1007/s11606-008-0618-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisman DS, Bashir L, Mehta A, et al. A medical resident post-discharge phone call study. Hosp Pract 2012;40:138–44. 10.3810/hp.2012.04.979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman LE, Sarkar U, Kessell E, et al. Support from hospital to home for elders: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:472–81. 10.7326/M14-0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong FK, So C, Chau J, et al. Economic evaluation of the differential benefits of home visits with telephone calls and telephone calls only in transitional discharge support. Age Ageing 2015;44:143–7. 10.1093/ageing/afu166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mistiaen P, Poot E, follow‐up T. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD004510 10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soong C, Kurabi B, Wells D, et al. Do post discharge phone calls improve care transitions? A cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e112230 10.1371/journal.pone.0112230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan B, Goldman LE, Sarkar U, et al. The effect of a care transition intervention on the patient experience of older multi-lingual adults in the safety net: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1788–94. 10.1007/s11606-015-3362-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong FK, Chow SK, Chan TM, et al. Comparison of effects between home visits with telephone calls and telephone calls only for transitional discharge support: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2014;43:91–7. 10.1093/ageing/aft123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Quinn K, et al. Assessing the impact of nurse post-discharge telephone calls on 30-day hospital readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1519–25. 10.1007/s11606-014-2954-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, et al. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med 2001;111:26–30. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00966-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS 2017 procedure-specific measures updates and specifications report hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures. Version 6. &Ldquo;multiple readmissions”. 13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Code of Federal Regulations. "Protection of human subjects." National institutes of health office for protection from research risks, 2009. Title 45:Part 46.116:d1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health and Human Services, Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections. January 31, 2008 SACHRP letter to HHS Secretary: recommendations related to waiver of informed consent and interpretation of “minimal risk”. 2008. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/2008-january-31-letter/index.html (accessed 1 Dec 2017).

- 20.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390 10.1136/bmj.a2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang MC, Qin J, Chiang CT. Analyzing recurrent event data with informative censoring. J Am Stat Assoc 2001;96:1057–65. 10.1198/016214501753209031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano LA, Elliott MN, Goldstein E, et al. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev 2010;67:27–37. 10.1177/1077558709341065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, et al. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nurs Outlook 2011;59:85–94. 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jager AJ, Wynia MK. Who gets a teach-back? Patient-reported incidence of experiencing a teach-back. J Health Commun 2012;17(Suppl 3):294–302. 10.1080/10810730.2012.712624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbloom ST, Harris P, Pulley J, et al. The mid-South clinical data research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21:627–32. 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danciu I, Cowan JD, Basford M, et al. Secondary use of clinical data: the Vanderbilt approach. J Biomed Inform 2014;52:28–35. 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM. Comparison of National Death Index and World Wide Web death searches. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:107–11. 10.1093/aje/152.2.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams BC, Demitrack LB, Fries BE. The accuracy of the National Death Index when personal identifiers other than Social Security number are used. Am J Public Health 1992;82:1145–7. 10.2105/AJPH.82.8.1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM. Roundtable on evidence-based medicine The learning healthcare system: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, 2007. Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53492/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019600supp001.pdf (408.1KB, pdf)