Key Points

Question

Which of the nonpharmacological interventions used for postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty are effective?

Findings

In a systematic review of 5509 studies, 39 randomized clinical trials were included in a meta-analysis (2391 patients) and demonstrated moderate-certainty evidence that electrotherapy and acupuncture reduce or delay opioid consumption, but there is low certainty or very low certainty that they improve pain. Continuous passive motion and preoperative exercise do not improve pain or reduce opioid consumption (low certainty or very low certainty), and cryotherapy reduces opioid consumption but does not improve pain (very low certainty).

Meaning

After total knee arthroplasty, electrotherapy and acupuncture were associated with reduced and delayed opioid consumption.

Abstract

Importance

There is increased interest in nonpharmacological treatments to reduce pain after total knee arthroplasty. Yet, little consensus supports the effectiveness of these interventions.

Objective

To systematically review and meta-analyze evidence of nonpharmacological interventions for postoperative pain management after total knee arthroplasty.

Data Sources

Database searches of MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE (OVID), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science (ISI database), Physiotherapy Evidence (PEDRO) database, and ClinicalTrials.gov for the period between January 1946 and April 2016.

Study Selection

Randomized clinical trials comparing nonpharmacological interventions with other interventions in combination with standard care were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Three reviewers independently extracted the data from selected articles using a standardized form and assessed the risk of bias. A random-effects model was used for the analyses.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Postoperative pain and consumption of opioids and analgesics.

Results

Of 5509 studies, 39 randomized clinical trials were included in the meta-analysis (2391 patients). The most commonly performed interventions included continuous passive motion, preoperative exercise, cryotherapy, electrotherapy, and acupuncture. Moderate-certainty evidence showed that electrotherapy reduced the use of opioids (mean difference, −3.50; 95% CI, −5.90 to −1.10 morphine equivalents in milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours; P = .004; I2 = 17%) and that acupuncture delayed opioid use (mean difference, 46.17; 95% CI, 20.84 to 71.50 minutes to the first patient-controlled analgesia; P < .001; I2 = 19%). There was low-certainty evidence that acupuncture improved pain (mean difference, −1.14; 95% CI, −1.90 to −0.38 on a visual analog scale at 2 days; P = .003; I2 = 0%). Very low-certainty evidence showed that cryotherapy was associated with a reduction in opioid consumption (mean difference, −0.13; 95% CI, −0.26 to −0.01 morphine equivalents in milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours; P = .03; I2 = 86%) and in pain improvement (mean difference, −0.51; 95% CI, −1.00 to −0.02 on the visual analog scale; P < .05; I2 = 62%). Low-certainty or very low-certainty evidence showed that continuous passive motion and preoperative exercise had no pain improvement and reduction in opioid consumption: for continuous passive motion, the mean differences were −0.05 (95% CI, −0.35 to 0.25) on the visual analog scale (P = .74; I2 = 52%) and 6.58 (95% CI, −6.33 to 19.49) opioid consumption at 1 and 2 weeks (P = .32, I2 = 87%), and for preoperative exercise, the mean difference was −0.14 (95% CI, −1.11 to 0.84) on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index Scale (P = .78, I2 = 65%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this meta-analysis, electrotherapy and acupuncture after total knee arthroplasty were associated with reduced and delayed opioid consumption.

This systematic review and meta-analysis outlines the evidence for nonpharmacological interventions for postoperative pain management after total knee arthroplasty.

Introduction

There are 234 million major surgical procedures performed every year worldwide, and most patients experience moderate to severe postoperative pain. Inadequate postoperative pain management has profound acute effects, including immune system suppression, decreased mobility that increases deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism rates, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. Long-term influences of poor pain management include transition to chronic pain and prolonged narcotic consumption, which can result in opioid dependence, an epidemic in the United States.

First-line therapies to treat postoperative pain are pharmacological, including anesthetics, opioids, and acetaminophen. Recently, nonpharmacological approaches to pain management aimed at reducing the use of prescription medications have increased. Physiotherapy is effective in treating postoperative pain and quality-of-life improvement and is standard treatment. However, other commonly used interventions for pain management have conflicting evidence on their effectiveness. As opioid addiction becomes a national priority, the importance of using effective nonpharmacological strategies for postoperative pain is now a top scientific priority.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures worldwide. It is used for patients with advanced knee osteoarthritis, and the goals of surgery are to decrease pain, restore mobility and function, and improve health-related quality of life. Total knee arthroplasty is associated with intense postoperative pain, and many patients report moderate to severe postoperative pain past the anticipated recovery period. Therefore, many nonpharmaceutical therapies are performed in this population. Ensuring effective therapies for postoperative pain management is an important part of TKA care.

We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of commonly used drug-free interventions for pain management after TKA. We gathered evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on postoperative pain as measured by established pain metrics and reduced analgesic consumption, including opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). This comprehensive analysis of nonpharmaceutical pain management therapies can inform practice and identify effective pain management regimens that could also potentially reduce the prescribing of opioids after surgery.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in accord with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Search Strategy

Databases

In an academic medical setting, we searched electronic databases to identify relevant studies for the period between January 1946 and April 2016, including MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE (OVID), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science (ISI database), Physiotherapy Evidence (PEDRO) database, and clinicaltrials.gov. We scanned reference lists of selected reviews, original articles, and textbooks to find additional articles. We conducted a gray literature search for other documents and hand searches of key conference proceedings, journals, professional organizations’ websites, national joint replacement registries, and guideline clearing houses. Snowball technique was applied to the search strategy.

Search Criteria

Because our aim was to be as comprehensive as possible in the systematic review, we did not place time or publication status limits to the search except for restriction to the English language. Two Chinese studies with English abstracts were considered; however, translation resources were not available to include them. We used the following search string in each database: (postoperative pain* OR postoperative pain OR post-operative pain) AND (total knee* or total knee arthroplasty OR total knee replacement OR TKA). Asterisks are used to truncate words, so that every desinence after the asterisks will be searched. To achieve the highest sensitivity, we used a combination of keywords and indexed terms (eg, PubMed Medical Subject Headings).

Patients, Interventions, Comparators, and Outcomes

Our primary search objective addressed the PICO (patients, interventions, comparators, and outcomes) question. These targets included (P) patients undergoing primary TKA, (I) nonpharmacological treatments for pain management (plus usual analgesic therapy), (C) other nonpharmacological intervention or no intervention (plus usual analgesic therapy), and (O) postoperative pain relief, and opioid and NSAID consumption.

Study Selection

Design

Postoperative pain management is generally layered, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Hence, we selected studies comparing nonpharmacological interventions with routine pharmacological treatment either with other nonpharmacological approaches or with only routine pharmacological treatments. We restricted our meta-analysis to RCTs in which patients were 18 years or older and had elective primary surgical procedures that included all forms of fixation (cemented, hybrid, or cementless), surgical approaches (medial, lateral, parapatellar, or minimally invasive), and types of prostheses (constrained, semiconstrained, or mobile platform).

Outcomes of Interest

Three of us (D.T., D.G., and K.R.D.) independently screened all identified articles by scanning abstracts or portions of the text to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus between the reviewers. Postoperative pain relief was defined as the mean difference in scores on the visual analog scale (VAS) or the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index Scale (WOMAC). Opioid and other analgesic consumption was evaluated in terms of the mean difference in consumption of morphine equivalents in milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours, while other analgesic consumption was evaluated as the mean difference in the number of tablets per day. Time to first request for analgesia (patient-controlled analgesia [PCA]) in the acupuncture group was defined as minutes from the end of the intervention to the first PCA.

Information about quality of life was not systematically provided in the studies. Therefore, it was not included.

Intervention

We restricted our focus to commonly studied postoperative pain interventions. These included continuous passive motion (CPM), preoperative exercise, cryotherapy, electrotherapy, and acupuncture.

Continuous passive motion consists of using an external machine to provide regular movement to the knee using a predetermined range of motion (ROM). Theoretically, the repeated movements help increase ROM, while simultaneously improving pain.

Preoperative exercise (or prehabilitation) involves sessions performed by the patients in the weeks preceding surgery. This regimen enables them to cope better with the physical stress associated with the surgical procedure and aids postoperative rehabilitation efforts.

Cryotherapy is based on applying cold to the surgical site either through ice bags or cooled water to minimize tissue trauma. The theory is that application of cooler substances reduces intra-articular temperatures, which interferes with the conduction of nerve signals and reduces local blood flow. These changes lead to decreased swelling and perceived pain.

Electrotherapy (based on electrophysical agents) aims to reduce pain and improve function through an energy transfer to the body. These modalities include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and pulsed electromagnetic fields.

Acupuncture is a form of traditional Chinese medicine that requires the insertion of needles at specific points on the body to alleviate pain and other ailments. The plausible mechanism of acupuncture analgesia is its effect on the central nervous system, particularly a short-term and long-term effect on µ-opioid receptors, and consequent regulation of neurotransmitters and hormones.

Study Quality Assessment

Two of us (D.T. and D.G.) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the parameters defined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions criteria. Disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus between the reviewers. Based on the information provided from included studies, each item was recorded as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear (lack of information or unknown risk of bias).

Two of us (D.T. and D.G.) independently assessed the quality of the body of evidence for the different outcomes considered through the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, a validated and widely implemented tool to rate the quality of scientific evidence. According to the GRADE approach, we assessed 5 domains, grading the strength of evidence for each outcome.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Three of us (D.T., D.G., and K.R.D.) independently extracted the data from included articles. Key information was gathered systematically using a standardized form. These variables included country, year of publication, number of participants, intervention, age, sex, study design, duration of intervention, outcome time points, statistical method, postoperative pain, opioid or analgesic consumption, and summary of the results.

For the pain scores, we standardized the results to a single scale by converting outcomes reported on a numerical rating scale to a 10-point VAS. Where possible, the results were extracted manually from the published figures. Data in other forms (ie, median, interquartile range, and mean [95% CI]) were converted to means (SDs) according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. If data (eg, SDs and SEs) were not presented in the original article, corresponding authors were contacted to acquire the missing data, although no responses were received. We also normalized data for pain relief and analgesic consumption, opioid and other analgesic consumption, and time before the first analgesic treatment. Specifically, all data on opioid consumption were converted to milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours, other analgesic consumption was converted to the number of tablets per day, and time before the first analgesic treatment was converted to minutes.

We examined the evidence tables for clinical (participants, interventions, controls, outcomes, and measurement tools) and methodological heterogeneity to determine whether the studies were similar enough to perform a meta-analysis. Where appropriate to pool the results, we used weighted mean differences for continuous data using the same measurement scales and standardized mean differences for continuous outcomes using different scales. We pooled both sets of summary statistics using the inverse variance method, which included studies from different time points, and we conducted sensitivity analyses by single time point.

We tested statistical heterogeneity to determine if it was appropriate to combine the studies for meta-analysis. We examined heterogeneity graphically using forest plots and statistically by calculating the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). We considered an I2 statistic greater than 50% to be substantially heterogeneous. According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, in cases where the number of studies was less than 5 or studies were substantially heterogeneous, we used a random-effects model. We calculated the random-effects estimates for the corresponding statistics using the method by DerSimonian and Laird. Forest plots were created to display effect estimates with 95% CIs for individual trials and pooled results. For all data analysis, we used a software program (RevMan, version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration).

Results

Search Findings

Supplementary information is provided in eTables 1, 2, and 3 in the Supplement and in eFigures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, and 42 in the Supplement. Our search yielded 5509 studies, of which 120 (112 from selection and 8 added by hand and snowball searching) were appropriate for further assessment. Of the 77 RCTs we read in extenso, we extracted the data from 39 RCTs for our meta-analysis (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Included studies were published between 1991 and 2015.

Study Characteristics

A pooled total of 2391 patients were examined in the RCTs (Table 1). We categorized the 39 RCTs based on 2 outcomes (pain relief and analgesic consumption, including different measures and types) and 5 interventions, including 18 studies in the CPM group (14 on pain and 5 on analgesics), 3 studies in the preoperative exercise group (all on pain), 12 studies in the cryotherapy group (8 on pain and 10 on analgesics), 4 studies in the electrotherapy group (2 on pain and 2 on analgesics), and 4 studies in the acupuncture group (2 on pain and 3 on analgesics). One study recurred in 3 different categories owing to multiple comparison groups within the article. For the studies that did not provide sufficient data, we attempted to contact authors but received no response.

Table 1. Characteristics of Randomized Clinical Trials of Nonpharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty.

| Source | Country | No. of Participants in Per-Protocol Analysis | Intervention | Age, Mean (SD) or Median (Range), y | Female, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | |||||

| Beaupré et al, 2001 | Canada | 120 | T1: CPM | T1: 68 (9) | T1: 30 |

| T2: Slider board | T2: 68 (9) | T2: 50 | |||

| C: Standard exercise | C: 69 (8) | C: 52.5 | |||

| Bennett et al, 2005 | Australia | 147 | T1: Standard CPM | T1: 70.7 | T1: 72.3 |

| T2: Early flexion CPM | T2: 71.4 | T2: 64.6 | |||

| C: No CPM | C: 71.7 | C: 67.3 | |||

| Bruun-Olsen et al, 2009 | Norway | 63 | T: CPM plus active exercise | 68 (10) | T: 73 |

| C: Active exercise | 71 (10) | C: 67 | |||

| Chen et al, 2013 | Taiwan | 107 | T: CPM plus basic rehabilitation | T: 69.3 (6.8) | NA |

| C: Basic rehabilitation | C: 69.5 (8.2) | NA | |||

| Colwell and Morris 1992 | United States | 22 | T: CPM plus standard rehabilitation | T: 73 | T: 67 |

| C: Immobilization in a posterior splint plus standard rehabilitation | C: 74 | C: 70 | |||

| Denis et al, 2006 | Canada | 81 | T1: Low-intensity CPM plus conventional physical therapy | T1: 69.6 (6.7) | T1: 61.5 |

| T2: High-intensity CPM plus conventional physical therapy | T2: 68.4 (7.4) | T2: 46.4 | |||

| C: Conventional physical therapy | C: 67.1 (7.6) | C: 51.9 | |||

| Harms and Engstrom, 1991 | United Kingdom | 113 | T: CPM plus standardized exercise | T1: 69 (9) | T1: 78 |

| C: Standardized exercise | C: 71 (10) | C: 93 | |||

| Kim et al, 2009 | South Korea | 100 | T: Regular PROME plus standard exercise | 67.9 (53-83) | 100 |

| C: Standard exercise (no PROME) | NA | NA | |||

| Lenssen et al, 2003 | The Netherlands | 40 | T: CPM plus physical therapy | T: 65 (9) | T: 71 |

| C: Physical therapy | C: 66 (10) | C: 63 | |||

| Lenssen et al, 2008 | The Netherlands | 60 | T: CPM plus physical therapy | T: 68.9 (6.1) | T: 60 |

| C: Physical therapy | C: 67.5 (8.9) | C: 70 | |||

| MacDonald et al, 2000 | Canada | 120 | T1: CPM with ROM 0°-50° | NA | NA |

| T2: CPM with ROM 70°-110° | NA | NA | |||

| C: No CPM | NA | NA | |||

| Maniar et al, 2012 | India | 86 | T1: 1 d of CPM plus conventional physical therapy | T1: 66.8 | T1: 89 |

| T2: 3 d of CPM plus conventional physical therapy | T2: 66 | T2: 87 | |||

| C: Conventional physical therapy | C: 67.4 | C: 92 | |||

| May et al, 1999 | United States | 19 | T: CPM plus physical therapy | T: 73 (4) | T: 67 |

| C: Lower limb mobility board plus physical therapy | C: 66 (9) | C: 71 | |||

| McInnes et al, 1992 | United States | 93 | T: CPM plus conventional rehabilitation | T: 65.7 (1.6) | T: 65 |

| C: Conventional rehabilitation | C: 70.2 (1.3) | C: 64 | |||

| Montgomery and Eliasson, 1996 | United Kingdom | 60 | T: CPM | T: 74 (5) | T: 86 |

| C: Active physical therapy | C: 76 (6) | C: 75 | |||

| Pope et al, 1997 | Australia | 53 | T1: CPM 0°-40° ROM plus physical therapy | T1: 72.5 | T1: 64.7 |

| T2: CPM 0°-70° ROM plus physical therapy | T2: 72.7 | T2: 50 | |||

| C: Physical therapy | C: 72.2 | C: 69.6 | |||

| Sahin et al, 2006 | Turkey | 31 | T: CPM plus physical therapy | T: 61 (6.0) | T: 86 |

| C: Physical therapy | C: 61.6 (7.5) | C: 86 | |||

| Walker et al, 1991 | United States | 22 | T: CPM | T: 72.7 (61-83) | NA |

| C: No CPM | C: 73.6 (65-82) | ||||

| Preoperative Exercise | |||||

| Calatayud et al, 2016 | Spain | 44 | T: 8 wk of exercise training program 3 d per wk before surgery | T: 66.8 (4.8) | 84 |

| C: No intervention | NA | NA | |||

| Gstoettner et al, 2011 | Austria | 35 | T: 6 wk of preoperative proprioceptive training program | T: 72.8 (65-78) | NA |

| C: No intervention | C: 66.9 (61-75) | NA | |||

| McKay et al, 2012 | Canada | 22 | T: 6 wk of prehabilitation exercise training program | T: 60.58 (8.05) | T: 66.67 |

| C: No intervention | C: 63.5 (4.93) | C: 50 | |||

| Cryotherapy | |||||

| Albrecht et al, 1997 | Germany | 98 | T1: Intermittent ice blocks | T1: 69.8 | NA |

| T2: Continuous cold therapy | T2: 71.9 | NA | |||

| C: Standard postoperative care plus CPM | C: 73.8 | NA | |||

| Gibbons et al, 2001 | United Kingdom | 60 | T: Cold compression dressing | T: 70 | T: 63 |

| C: Robert Jones modified bandage | C: 71 | C: 53 | |||

| Ivey et al, 1994 | United States | 88 | T1: Hot ice thermal pads at 10°C | T1: 64.5 | T1: 57 |

| T2: Hot ice thermal pads at 15.6°C | T2: 64.2 | T2: 63 | |||

| C: Hot ice thermal pads at 21.1°C | C: 66.9 | C: 73 | |||

| Kullenberg et al, 2006 | Sweden | 83 | T: Cold compression applied with the Cryo Cuff (Aircast Incorporated) | T: 68.1 (6) | T: 74 |

| C: Standard care | C: 68.9 (6.8) | C: 70 | |||

| Levy and Marmar, 1993 | United States | 80 | T: Cold compression applied with the Cryo Cuff (Aircast Incorporated) | T: 74 | T: 82.5 |

| C: No intervention | C: 73 | C: 80 | |||

| Morsi, 2002 | Egypt | 60 | T: Cooling device | NA | NA |

| C: Standard care | NA | NA | |||

| Radkowski et al, 2007 | United States | 64 | T: Cryotherapy at 7.2°C continued until discharge plus elastic wrap | T: 63.7 | T: 54 |

| C: Cryotherapy at 23.9°C continued until discharge plus elastic wrap | C: 66.9 | C: 36 | |||

| Smith et al, 2002 | Australia | 84 | T: Cold therapy | T: 72.1 (7.8) | T: 54.8 |

| C: Compression bandage | C: 72 (7.1) | C: 45.2 | |||

| Su et al, 2012 | United States | 187 | T: Cryopneumatic device | NA | NA |

| C: Ice and static compression | NA | NA | |||

| Thienpont, 2014 | Belgium | 100 | T: Continuous cooling at 11°C | T: 67.5 (10.5) | T: 70 |

| C: Cold packs (conserved at −17°C) | C: 68.5 (10) | C: 80 | |||

| Webb et al, 1998 | United Kingdom | 31 | T: Cold compression with the Cryo Cuff (Aircast Incorporated) | T: 69.0 | NA |

| C: Standard care | C: 70.9 | NA | |||

| Walker et al, 1991 | United States | 30 | Continuous cooling pad plus CPM | T: 75.0 (58-87) | NA |

| CPM | C: 70.0 (56-82) | NA | |||

| Electrotherapy | |||||

| Adravanti et al, 2014 | Italy | 26 | T: Pulsed electromagnetic fields plus standard rehabilitation | T: 66 (13) | T: 62.5 |

| C: Standard rehabilitation | C: 73 (5) | C: 53 | |||

| Borckardt et al, 2013 | United States | 40 | T: Transcranial direct current stimulation | NA | NA |

| C: Sham transcranial direct current stimulation | NA | NA | |||

| Moretti et al, 2012 | Italy | 30 | T: Stimulation with pulsed electromagnetic fields 4 h per d for 60 d plus kinesitherapy | T: 70.5 (8.1) | NA |

| C: Kinesitherapy | C: 70.0 (10.6) | NA | |||

| Walker et al, 1991 | United States | 48 | T1: TENS plus CPM | T: 69.8 (61-69) | NA |

| T2: Subthreshold TENS plus CPM | T2: 73.9 (55-84) | NA | |||

| C: CPM | C: 73.9 (60-86) | NA | |||

| Acupuncture | |||||

| Chen et al, 2015 | Taiwan | 60 | T: Auricular acupuncture under general anesthesia | T: 68.9 (9.0) | T: 90 |

| C: Sham auricular acupuncture under general anesthesia | C: 69.0 (8.6) | C: 73 | |||

| Mikashima et al, 2012 | Japan | 80 | T: Acupuncture treatment plus standard rehabilitation | T: 72 (7) | T: 75 |

| C: Standard rehabilitation | C: 73 (5) | C: 70 | |||

| Tsang et al, 2007 | Hong Kong | 30 | T: Acupuncture plus standard rehabilitation | T: 70.6 (5.8) | T: 80 |

| C: Sham acupuncture plus standard rehabilitation | C: 66.1 (7.5) | C: 80 | |||

| Tzeng et al, 2015 | Taiwan | 47 | T1: Electroacupuncture | T1: 70.1 (6.9) | T1: 82 |

| T2: Sham electroacupuncture | T2: 69.6 (5.6) | T2: 75 | |||

| C: No intervention | C: 71.4 (7.3) | C: 71 | |||

Abbreviations: C, control group; CPM, continuous passive motion; NA, not available; PROME, passive ROM exercise; ROM, range of motion; T, treatment group; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Quality Assessment

All studies were assessed for the risk of bias (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The methodological heterogeneity reflects the different range of interventions we examined. We identified that the highest bias in studies was due to improper or absent masking during the study (31 of 39 RCTs). In 2 studies on cryotherapy, masking was adequately achieved. Studies also showed high risk of bias for selective outcome reporting in 13 cases, particularly in those testing the effectiveness of CPM, cryotherapy, and electrotherapy RCTs. There was also high risk of bias due to improper or absent random sequencing methods in 8 studies. Last, a study in the electrotherapy group showed high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data. We conducted sensitivity subgroup analyses for all the outcomes considered, classifying for sequence generation and allocation concealment availability, and no significant differences were shown (eFigures 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19 in the Supplement). The GRADE quality of evidence certainty level of evidence assessment is reported in detail below in the Assessed Outcomes and Evidence Synthesis subsection, in Table 2, and in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Main Findings of the Meta-analysis of Nonpharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplastya.

| Variable | No. of Studies | No. of Participants | Effect Estimate (95% CI) | I2 Heterogeneity, % | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Relief on the VAS | |||||

| CPM | 9 | 1025 | −0.05 (−0.35 to 0.25) | 52 | Very low |

| 1 wk | 8 | 575 | −0.27 (−0.70 to 0.16) | 35 | |

| 2 wk | 2 | 145 | −0.81 (−3.30 to 1.68) | 88 | |

| 3 mo | 2 | 170 | 0.50 (−0.30 to 1.29) | 54 | |

| 6 mo | 2 | 135 | 0.15 (−0.04 to 0.35) | 0 | |

| Cryotherapy | 8 | 1382 | −0.51 (−1.00 to −0.02) | 62 | Very low |

| Day 1 after surgery | 7 | 529 | −0.21 (−0.89 to 0.48) | 40 | |

| Day 2 after surgery | 5 | 422 | −1.00 (−2.01 to 0.02) | 59 | |

| Day 3 after surgery | 6 | 431 | −0.44 (−1.37 to 0.49) | 75 | |

| Electrotherapy | 2 | 189 | −2.11 (−2.74 to −1.47) | 80 | Very low |

| 1 mo | 2 | 63 | −1.95 (−2.68 to −1.22) | 17 | |

| 2 mo | 2 | 63 | −2.34 (−4.49 to −0.19) | 94 | |

| 6 mo | 2 | 63 | −2.60 (−5.12 to −0.08) | 83 | |

| Acupuncture | 3 | 230 | −0.66 (−1.29 to −0.03) | 69 | Low |

| 2 d | 2 | 90 | −1.14 (−1.90 to −0.38) | 0 | |

| 8 d | 2 | 140 | −0.37 (−1.04 to 0.30) | 72 | |

| Pain Relief on the WOMAC | |||||

| CPM | 5 | 578 | 0.03 (−0.19 to 0.24) | 0 | Low |

| 6 wk | 2 | 168 | −0.66 (−2.12 to 0.81) | 60 | |

| 3 mo | 3 | 242 | 0.05 (−0.22 to 0.32) | 0 | |

| 6 mo | 2 | 168 | −0.34 (−1.35 to 0.68) | 0 | |

| Preoperative exercise | 3 | 132 | −0.14 (−1.11 to 0.84) | 65 | Low |

| 6 wk | 2 | 60 | 0.34 (−0.32 to 0.99) | 0 | |

| 12 wk | 2 | 72 | −0.78 (−1.63 to 0.07) | 8 | |

| Opioid Consumptionb | |||||

| CPM | 5 | 313 | 6.58 (−6.33 to 19.49) | 87 | Very low |

| 1 wk | 3 | 178 | 11.12 (−12.21 to 34.44) | 80 | |

| 2 wk | 2 | 135 | −3.78 (−7.67 to 0.11) | 8 | |

| Cryotherapy within 48 h | 7 | 468 | −0.13 (−0.26 to −0.01) | 86 | Very low |

| Cryotherapy vs nothing | 2 | 61 | −0.18 (−0.30 to −0.06) | 0 | |

| Cryotherapy vs compression | 5 | 407 | −0.12 (−0.28 to 0.04) | 90 | |

| Electrotherapy within 48 h | 2 | 99 | −3.50 (−5.90 to −1.10) | 17 | Moderate |

| Acupuncture within 48 h | 2 | 123 | −0.71 (−1.44 to 0.02) | 64 | Low |

| Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 2 | 90 | −0.92 (−2.19 to 0.35) | 79 | |

| Acupuncture vs nothing | 1 | 33 | −0.40 (−1.05 to 0.25) | NA | |

| NSAID Consumption | |||||

| Cryotherapy within 48 h | 3 | 363 | −0.75 (−1.63 to 0.12) | 95 | Very low |

| Cryotherapy vs nothing | 1 | 60 | −1.90 (−2.25 to −1.55) | NA | |

| Cryotherapy vs compression | 2 | 303 | −0.31 (−0.55 to −0.07) | 0 | |

| Time to First PCAc | |||||

| Acupuncture | 2 | 124 | 46.17 (20.84 to 71.50) | 19 | Moderate |

| Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture | 2 | 91 | 34.58 (−12.61 to 81.77) | 53 | |

| Acupuncture vs nothing | 1 | 33 | 57.90 (16.52 to 99.28) | NA | |

Abbreviations: CPM, continuous passive motion; GRADE, Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; NA, not available; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; VAS, visual analog scale (range, 0-10); WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index Scale (range, 0-20).

The inverse variance method was used for the statistical analyses.

Units are the mean use of morphine equivalents in milligrams at 1 and 2 weeks for CPM, the number of tablets per 48 hours for cryotherapy, and morphine equivalents in milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours for all other variables under this heading.

Units are minutes after surgery.

Publication Bias

To address publication bias, we created funnel plots for all analyses. No asymmetric patterns were seen (eFigures 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, and 29 in the Supplement).

Interventions

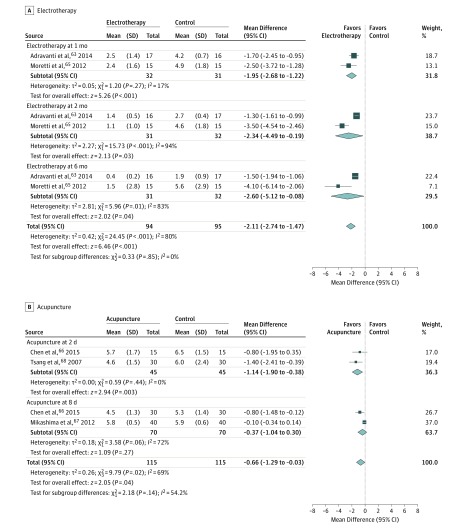

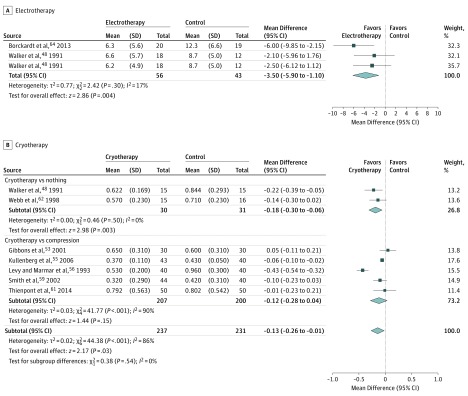

The key findings of the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 2 for 2 types of pain scales and for 3 types of analgesic outcomes. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the meta-analyses that reported statistically significant results.

Figure 1. Pain Relief and Analgesic Consumption.

Shown are individual and pooled weighted mean differences in pain measured with a visual analog scale using the inverse variance method. A, The mean differences at 1, 2, and 6 months after surgery. B, The mean differences at 2 days and 8 days after surgery. A random-effects model was used to pool the data.

Figure 2. Opioid and Other Analgesic Consumption.

Shown are individual and pooled weighted mean differences in opioid consumption within 48 hours after surgery (morphine equivalents in milligrams per kilogram per 48 hours) using the inverse variance method. A, Electrotherapy. B, Cryotherapy. A random-effects model was used to pool the data.

Assessed Outcomes and Evidence Synthesis

Pain Relief and Analgesic Consumption

We found that the quality of evidence was of low certainty or very low certainty for pain improvement in all examined interventions (Table 2). Meta-analysis of 2 pain relief studies (189 patients) suggested a significant improvement in experimental groups vs controls with electrotherapy, with mean differences of −1.95 (95% CI, −2.68 to −1.22; P < .001; I2 = 17%) on the VAS at 1 month, −2.34 (95% CI, −4.49 to −0.19; P = .03; I2 = 94%) on the VAS at 2 months, and −2.60 (95% CI, −5.12 to −0.08; P = .04; I2 = 83%) on the VAS at 6 months (Figure 1A). Meta-analysis of 3 studies (230 patients) suggested a significant improvement in experimental groups vs controls with acupuncture, with a mean difference of −1.14 (95% CI, −1.90 to −0.38; P = .003; I2 = 0%) on the VAS at 6 months (Figure 1B). Meta-analysis of 8 studies (1383 patients) showed a mean difference with cryotherapy of −0.51 (95% CI, −1.00 to −0.02; P < .05; I2 = 62%), but all subgroup analyses showed no statistically significant mean differences (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Meta-analysis of 9 studies (1025 patients) suggested no significant improvement in experimental groups vs controls with CPM (mean differences, −0.05; 95% CI, −0.35 to 0.25; P = .74; I2 = 52% on the VAS at 1 week and 6 months and −0.20; 95% CI, −0.62 to 0.23; P = .54; I2 = 0% on the CPM WOMAC at 6 weeks and 6 months) (eFigure 3 and eFigure 4 in the Supplement) or with preoperative exercise (mean difference, −0.14; 95% CI, −1.11 to 0.84; P = .78; I2 = 65% on the WOMAC at 6 and 12 weeks) (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

To address possible overestimation that could originate from the study design (ie, pain as a primary or secondary outcome), we conducted sensitivity subgroup analyses. No significant differences were found (eFigures 20, 21, 22, and 23 in the Supplement).

Opioid and Other Analgesic Consumption

Meta-analysis of 2 studies (99 patients) showed moderate-certainty reduction in opioid consumption for electrotherapy (mean difference, −3.50; 95% CI, −5.90 to −1.10 opioids in milligrams per hour; P = .004; I2 = 17%) (Figure 2A). Meta-analysis of 7 studies (468 patients) showed very low-certainty reduction in opioid consumption for cryotherapy (mean difference, −0.13; 95% CI, −0.26 to −0.01 opioids in milligrams per hour; P = .03; I2 = 86%) (Figure 2B). Meta-analysis of 3 studies (363 patients) showed very low-certainty nonreduction in nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) consumption for cryotherapy (mean difference, −0.75; 95% CI, −1.63 to 0.12 tablets per day; P = .09; I2 = 95%). Nevertheless, subgroup analyses showed a significant reduction in NSAID consumption, with mean differences of −1.90 (95% CI, −2.25 to −1.55 tablets per day; P < .01; I2 = not applicable) for cryotherapy vs nothing (1 study, with 60 patients) and −0.31 (95% CI, −0.55 to −0.07 tablet per day; P = .01; I2 = 0%) for cryotherapy vs compression (2 studies, with 303 patients) (eFigure 6 in the Supplement). Acupuncture (2 studies, with 123 patients) and CPM (5 studies, with 313 patients) showed no significant differences between experimental groups and controls for amount of opioid consumed after surgery, with low-certainty and very low-certainty evidence, respectively: the mean differences were −0.71 (95% CI, −1.44 to 0.02 opioids in milligrams per hour; P = .06; I2 = 64%) for acupuncture (eFigure 7 in the Supplement) and 6.58 (95% CI, −6.33, to 19.49 opioids in milligrams per hour; P = .32; I2 = 87%) for CPM (eFigure 8 in the Supplement). Preoperative exercise studies did not report data on opioid consumption.

To address opioid consumption changes across the study period, we conducted sensitivity analyses stratifying for period (before or after 2000). The results were not significant (eFigure 39 and eFigure 40 in the Supplement).

Time Before the First Analgesic Treatment

In 2 studies (124 patients), we assessed time to first PCA in the acupuncture group and found moderate-certainty evidence that acupuncture significantly increases this period (mean difference, 46.17; 95% CI, 20.84-71.50 minutes; P < .001; I2 = 19%) (eFigure 9 in the Supplement). Also, a subgroup analysis carried out in 1 study revealed a stronger difference in the acupuncture group compared with controls, with a mean difference of 57.90 (95% CI, 6.52-99.28 minutes; P = .006; I2 = not applicable).

Conflict of Interest of Included Studies

Authors of 7 studies reported at least 1 conflict of interest statement. Only 3 studies explicitly identified the funding sources (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This meta-analysis found moderate evidence that electrotherapy and acupuncture improved postoperative pain management and reduced opioid consumption. We found very low-certainty evidence that cryotherapy reduced opioid consumption, but there was no evidence that it improves perceived pain. The meta-analysis suggests that CPM and preoperative exercise do not help alleviate pain (measured at different time points and using different scales) or reduce opioid consumption.

Electrotherapy and acupuncture are known to reduce postoperative pain. Electrotherapy is thought to decrease pain by stimulating the pain fibers with a nonpainful stimulus that blocks painful stimuli from reaching the brain and is free of adverse effects. One study recommended electrotherapy to reduce analgesic use for various surgical procedures. Our findings suggest that electrotherapy may not only reduce early pain but also change the long-term trajectory of recovery from pain after TKA. We found evidence that electrotherapy changed pain severity at 1, 2, and 6 months, with increasing effect sizes over time. Hence, electrotherapy might be considered an effective nonpharmacological ancillary intervention to standard pharmacological therapy for long-term pain improvement. This finding is an important and underappreciated contribution to the literature that examines factors influencing the propensity to develop chronic pain after surgery, an area of significant general interest in clinical literature. However, because the quality of the studies analyzed for this outcome was very low, more high-quality RCTs on long-term pain improvement after electrotherapy are needed.

Our findings showed that acupuncture pain relief benefits concentrate in the early postoperative phase but are ineffective in the long run. A delay in opioid consumption can be considered a proxy of lower pain levels; high postoperative pain can lead to chronic pain. Our results suggest that acupuncture led to a modest delay in PCA requests, leading to possible benefits in this critical time window. Similarly, others have found that acupuncture provides significant pain improvement in patients undergoing TKA and total hip arthroplasty in the first 2 days after surgery. The acupuncture studies had less risk of bias than other modalities, so our conclusions regarding their benefit are more secure. If confirmed in future studies, our findings support the use of both electrotherapy and acupuncture after TKA.

We found less evidence that cryotherapy reduced opioid and NSAID consumption. While a Cochrane review article reported a small benefit of cryotherapy for pain at 2 days after surgery but not at 1 and 3 days, our results demonstrated very low-certainty evidence for this intervention on postoperative analgesia after TKA. More research about this intervention could focus on opioid consumption effects.

The CPM results are particularly notable. Continuous passive motion is commonly used after TKA, with the 2 proposed benefits of improved function and reduced pain. However, recent work has not shown the usefulness of CPM in improving functionality and rehabilitation. The RCTs included in our meta-analysis found very low-certainty evidence that CPM reduces opioid consumption during the early postoperative phase and found low-certainty or very low-certainty evidence that CPM provides no improvement in perceived pain. Our findings are consistent with a Cochrane review article that also found no benefits of CPM on function, pain, or quality of life after TKA. These results need to be cautiously considered because CPM is not without risk. Also, CPM is an expensive and time-consuming procedure. Because the results of other studies have suggested that CPM is ineffective in improving functionality and that CPM is associated with increased hospital length of stay, careful consideration should be exercised before applying this treatment.

Our study also found little evidence to support that preoperative exercise improves postoperative pain and thus adds to conflicting literature. Several studies have reported that preoperative exercise had no significant benefit in improving functionality, quality of life, or pain for patients after TKA, whereas others found that the intervention improved postoperative pain, hospital length of stay, and physical function after various surgical procedures. However, given the poor quality of the evidence, our results do not support the use of preoperative exercise for patients after TKA and advocate for further high-quality studies on this topic.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered before interpreting these findings. First, for each intervention and outcome, we could only include a small number of studies in the analysis because of high heterogeneity in the timing and type of interventions. To address this issue, we pooled studies from different time points to obtain larger sample sizes, and subgroup analyses showed results similar to the overall findings (eFigures 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, and 38 in the Supplement). Age and sex were not differently distributed in the groups (treatment vs control as shown in the meta-regressions) (eFigure 41 and eFigure 42 in the Supplement). Second, studies often showed a high risk or unclear risk of bias, which may have led to overestimations or underestimations of the reported effects. However, we assessed the quality of evidence through a validated tool and took into account the level of certainty of evidence for each outcome. Third, most studies did not achieve full masking, which also may have caused overestimation of effects in various meta-analyses conducted. Fourth, some studies lacked sufficient data to measure dispersion for the effect measurement (SD or SE). We attempted to address this problem by contacting authors but never obtained a response.

Conclusions

Although past studies have investigated individual nonpharmaceutical interventions for different postoperative outcomes after TKA, to our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first comprehensive study to examine the most frequent treatments, adding new evidence on drug consumption. As prescription opioid use is under national scrutiny and because surgery has been identified as an avenue for addiction, it is important to recognize effective alternatives to standard pharmacological therapy, which remains the first option for treatment. Our study provides modest but clinically significant evidence that electrotherapy and acupuncture can potentially reduce and delay opioid consumption. However, strong supporting research is further needed. Evidence for other interventions, although limited by the quality of the underlying literature, had less support.

eTable 1. Risk of Bias Summary From Randomized Clinical Trials for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eTable 2. GRADE of Evidence Assessment for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eTable 3. Summary of Key Review Findings for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eFigure 1. PRISMA Flowchart Depicting the Search Strategy

eFigure 2. Pain Relief: Cryotherapy

eFigure 3. Pain Relief: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 4. Pain Relief: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 5. Pain Relief: Preoperative Exercise

eFigure 6. NSAID Consumption: Cryotherapy

eFigure 7. Opioid Consumption: Acupuncture

eFigure 8. Opioid Consumption: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 9. Acupuncture

eFigure 10. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 11. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 12. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 13. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 14. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 15. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 16. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 17. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 18. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 19. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 20. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 21. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 22. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 23. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 24. Funnel Plot of Comparison for CPM Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 25. Funnel Plot of Comparison for CPM Trials Measured in Terms of Opioid Consumption (mg/kg/48 Hours of Morphine Equivalent)

eFigure 26. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Cryotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale

eFigure 27. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Cryotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Opioid Consumption (mg/kg/48 Hours of Morphine Equivalent)

eFigure 28. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Electrotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 29. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Acupuncture Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 30. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 31. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 32. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 33. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 34. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 35. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 36. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 37. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 38. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 39. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Time (Studies Divided If Published Prior or Comprising Year 2000 or From 2001 Onwards)

eFigure 40. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Time (Studies Divided If Published Prior or Comprising Year 2000 or From 2001 Onwards)

eFigure 41. Results of the Meta-Regression for the Distribution of Age in the Groups (Treatment vs Control)

eFigure 42. Results of the Meta-Regression for the Distribution of Sex in the Groups (Treatment vs Control)

References

- 1.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. . An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(2):534-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23(1):21-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1618-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doctor J, Cowan P, Meeker D, Bruckenthal P, Broderick J Encouraging integrative, non-opioid approaches to pain: a policy agenda. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/10/04/encouraging-integrative-non-opioid-approaches-to-pain-a-policy-agenda/. Accessed November 17, 2016.

- 6.Kerr DR, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):174-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zukowski M, Kotfis K. The use of opioid adjuvants in perioperative multimodal analgesia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2012;44(1):42-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chughtai M, Elmallah RD, Mistry JB, et al. Nonpharmacologic pain management and muscle strengthening following total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(3):194-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakespeare D, Kinzel V. Rehabilitation after total knee replacement: time to go home? Knee. 2005;12(3):185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascarin NC, Vancini RL, Andrade ML, Magalhães EP, de Lira CA, Coimbra IB. Effects of kinesiotherapy, ultrasound and electrotherapy in management of bilateral knee osteoarthritis: prospective clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(13):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey LA, Brosseau L, Herbert RD. Continuous passive motion following total knee arthroplasty in people with arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD004260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbasi J. As opioid epidemic rages, complementary health approaches to pain gain traction. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2343-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brander V, Stulberg SD. Rehabilitation after hip- and knee-joint replacement: an experience- and evidence-based approach to care. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11)(suppl):S98-S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? a systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435-e000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puolakka PA, Rorarius MG, Roviola M, Puolakka TJ, Nordhausen K, Lindgren L. Persistent pain following knee arthroplasty. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27(5):455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crespin DJ, Griffin KH, Johnson JR, et al. Acupuncture provides short-term pain relief for patients in a total joint replacement program. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1195-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCartney CJ, Nelligan K. Postoperative pain management after total knee arthroplasty in elderly patients: treatment options. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(2):83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gori D, Tedesco D, Fantini MP, Hernandez-Boussard T, Desai K, Bianciardi L Non-pharmaceutical interventions in post-operative pain management of total knee replacement. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016052104. Accessed November 28, 2016.

- 20.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheppard MS, Westlake SM, McQuarrie A. Continuous passive motion: where are we now? Physiother Can. 1995;47(1):36-39. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaupré LA, Lier D, Davies DM, Johnston DB. The effect of a preoperative exercise and education program on functional recovery, health related quality of life, and health service utilization following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(6):1166-1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adie S, Kwan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA, Mittal R. Cryotherapy following total knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson T. Key concepts with electrophysical agents. Phys Ther Rev. 2010;15(4):351-359. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sims J. The mechanism of acupuncture analgesia: a review. Complement Ther Med. 1997;5(2):102-111. doi: 10.1016/S0965-2299(97)80008-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris RE, Zubieta JK, Scott DJ, Napadow V, Gracely RH, Clauw DJ. Traditional Chinese acupuncture and placebo (sham) acupuncture are differentiated by their effects on µ-opioid receptors (MORs). Neuroimage. 2009;47(3):1077-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Updated March 2011. Accessed July 10, 2016.

- 28.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):380-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, et al. ; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Back, Neck Group . 2015 Updated Method Guideline for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Back and Neck Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1660-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaupré LA, Davies DM, Jones CA, Cinats JG. Exercise combined with continuous passive motion or slider board therapy compared with exercise only: a randomized controlled trial of patients following total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2001;81(4):1029-1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett LA, Brearley SC, Hart JA, Bailey MJ. A comparison of 2 continuous passive motion protocols after total knee arthroplasty: a controlled and randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(2):225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruun-Olsen V, Heiberg KE, Mengshoel AM. Continuous passive motion as an adjunct to active exercises in early rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(4):277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen LH, Chen CH, Lin SY, et al. Aggressive continuous passive motion exercise does not improve knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(3-4):389-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colwell CW Jr, Morris BA. The influence of continuous passive motion on the results of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(276):225-228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denis M, Moffet H, Caron F, Ouellet D, Paquet J, Nolet L. Effectiveness of continuous passive motion and conventional physical therapy after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2006;86(2):174-185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harms M, Engstrom B. Continuous passive motion as an adjunct to treatment in the physiotherapy management of the total knee arthroplasty patient. Physiotherapy. 1991;77(4):301-307. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(10)61768-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim TK, Park KK, Yoon SW, Kim SJ, Chang CB, Seong SC. Clinical value of regular passive ROM exercise by a physical therapist after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(10):1152-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenssen A, de Bie RA, Bulstra SK, van Steyn MJA. Continuous passive motion (CPM) in rehabilitation following total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. Phys Ther Rev. 2003;(8):123-129. doi: 10.1179/108331903225003019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenssen TA, van Steyn MJ, Crijns YH, et al. Effectiveness of prolonged use of continuous passive motion (CPM), as an adjunct to physiotherapy, after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, McCalden RW, Kramer J, Vaz M. Prospective randomized clinical trial of continuous passive motion after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(380):30-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maniar RN, Baviskar JV, Singhi T, Rathi SS. To use or not to use continuous passive motion post–total knee arthroplasty presenting functional assessment results in early recovery. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):193-200.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.May LA, Busse W, Zayac D, Whitridge MR. Comparison of continuous passive motion (CPM) machines and lower limb mobility boards (LLiMB) in the rehabilitation of patients with total knee arthroplasty. Can J Rehabil. 1999;12:257-263. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McInnes J, Larson MG, Daltroy LH, et al. . A controlled evaluation of continuous passive motion in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1992;268(11):1423-1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montgomery F, Eliasson M. Continuous passive motion compared to active physical therapy after knee arthroplasty: similar hospitalization times in a randomized study of 68 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(1):7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pope RO, Corcoran S, McCaul K, Howie DW. Continuous passive motion after primary total knee arthroplasty: does it offer any benefits? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(6):914-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sahin E, Akalin E, Bircan C, et al. . The effects of continuous passive motion on outcome in total knee arthroplasty. J Rheumatol Med Rehabil. 2006;17(2):85-90. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker RH, Morris BA, Angulo DL, Schneider J, Colwell CW Jr. Postoperative use of continuous passive motion, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and continuous cooling pad following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6(2):151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calatayud J, Casaña J, Ezzatvar Y, Jakobsen MD, Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. High-intensity preoperative training improves physical and functional recovery in the early post-operative periods after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial [published online January 14, 2016]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gstoettner M, Raschner C, Dirnberger E, Leimser H, Krismer M. Preoperative proprioceptive training in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2011;18(4):265-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKay C, Prapavessis H, Doherty T. The effect of a prehabilitation exercise program on quadriceps strength for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled pilot study. PM R. 2012;4(9):647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albrecht S, le Blond R, Köhler V, et al. [Cryotherapy as analgesic technique in direct, postoperative treatment following elective joint replacement] [in German]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1997;135(1):45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibbons CE, Solan MC, Ricketts DM, Patterson M. Cryotherapy compared with Robert Jones bandage after total knee replacement: a prospective randomized trial. Int Orthop. 2001;25(4):250-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivey M, Johnston RV, Uchida T. Cryotherapy for postoperative pain relief following knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9(3):285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kullenberg B, Ylipää S, Söderlund K, Resch S. Postoperative cryotherapy after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 86 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1175-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(297):174-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morsi E. Continuous-flow cold therapy after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):718-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radkowski CA, Pietrobon R, Vail TP, Nunley JA II, Jain NB, Easley ME. Cryotherapy temperature differences after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2007;16(2):67-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith J, Stevens J, Taylor M, Tibbey J. Bandaging and cold therapy in total knee replacement surgery. Orthop Nurs. 2002;21(2):61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Su EP, Perna M, Boettner F, et al. . A prospective, multi-center, randomised trial to evaluate the efficacy of a cryopneumatic device on total knee arthroplasty recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11)(suppl A):153-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thienpont E. Does advanced cryotherapy reduce pain and narcotic consumption after knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3417-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Webb JM, Williams D, Ivory JP, Day S, Williamson DM. The use of cold compression dressings after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Orthopedics. 1998;21(1):59-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adravanti P, Nicoletti S, Setti S, Ampollini A, de Girolamo L. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic field therapy in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. Int Orthop. 2014;38(2):397-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borckardt JJ, Reeves ST, Robinson SM, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) reduces postsurgical opioid consumption in total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Clin J Pain. 2013;29(11):925-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moretti B, Notarnicola A, Moretti L, et al. I-ONE therapy in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized and controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen CC, Yang CC, Hu CC, Shih HN, Chang YH, Hsieh PH. Acupuncture for pain relief after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40(1):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mikashima Y, Takagi T, Tomatsu T, Horikoshi M, Ikari K, Momohara S. Efficacy of acupuncture during post-acute phase of rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. J Tradit Chin Med. 2012;32(4):545-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsang RC, Tsang PL, Ko CY, Kong BC, Lee WY, Yip HT. Effects of acupuncture and sham acupuncture in addition to physiotherapy in patients undergoing bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(8):719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tzeng CY, Chang SL, Wu CC, et al. Single-blinded, randomised preliminary study evaluating the effects of 2 Hz electroacupuncture for postoperative pain in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Acupunct Med. 2015;33(4):284-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Ljunggreen AE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can reduce postoperative analgesic consumption: a meta-analysis with assessment of optimal treatment parameters for postoperative pain. Eur J Pain. 2003;7(2):181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joshi RN, White PB, Murray-Weir M, Alexiades MM, Sculco TP, Ranawat AS. Prospective randomized trial of the efficacy of continuous passive motion post total knee arthroplasty: experience of the Hospital for Special Surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2364-2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cabilan CJ, Hines S, Munday J. The effectiveness of prehabilitation or preoperative exercise for surgical patients: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(1):146-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoogeboom TJ, Oosting E, Vriezekolk JE, et al. Therapeutic validity and effectiveness of preoperative exercise on functional recovery after joint replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santa Mina D, Clarke H, Ritvo P, et al. Effect of total-body prehabilitation on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2014;100(3):196-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Risk of Bias Summary From Randomized Clinical Trials for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eTable 2. GRADE of Evidence Assessment for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eTable 3. Summary of Key Review Findings for Non-Pharmacological Postoperative Pain Management After Total Knee Arthroplasty

eFigure 1. PRISMA Flowchart Depicting the Search Strategy

eFigure 2. Pain Relief: Cryotherapy

eFigure 3. Pain Relief: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 4. Pain Relief: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 5. Pain Relief: Preoperative Exercise

eFigure 6. NSAID Consumption: Cryotherapy

eFigure 7. Opioid Consumption: Acupuncture

eFigure 8. Opioid Consumption: Continuous Passive Motion (CPM)

eFigure 9. Acupuncture

eFigure 10. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 11. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 12. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 13. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 14. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 15. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 16. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 17. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 18. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 19. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on Allocation Concealment and Random Sequence Generation

eFigure 20. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 21. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 22. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 23. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies Based on How Pain Outcome Was Considered (Either Primary or Secondary)

eFigure 24. Funnel Plot of Comparison for CPM Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 25. Funnel Plot of Comparison for CPM Trials Measured in Terms of Opioid Consumption (mg/kg/48 Hours of Morphine Equivalent)

eFigure 26. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Cryotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale

eFigure 27. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Cryotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Opioid Consumption (mg/kg/48 Hours of Morphine Equivalent)

eFigure 28. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Electrotherapy Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 29. Funnel Plot of Comparison for Acupuncture Trials Measured in Terms of Reported Points in the VAS Scale at 1 Week

eFigure 30. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 31. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 32. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 33. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 34. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 35. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 36. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 37. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 38. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Type of Control

eFigure 39. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Time (Studies Divided If Published Prior or Comprising Year 2000 or From 2001 Onwards)

eFigure 40. Subgroup Sensitivity Analysis Comparing Studies by Time (Studies Divided If Published Prior or Comprising Year 2000 or From 2001 Onwards)

eFigure 41. Results of the Meta-Regression for the Distribution of Age in the Groups (Treatment vs Control)

eFigure 42. Results of the Meta-Regression for the Distribution of Sex in the Groups (Treatment vs Control)