Abstract

Design

Multi-center, prospective cohort study

Methods

Every two years between 2009 and 2013 (3 times), 646 HIV+ and 300 demographically-similar HIV-uninfected (HIV-) women from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study completed neuropsychological (NP) testing and questionnaires measuring PRFs (perceived stress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, depressive symptoms). Using mixed-effects regressions, we examined separate and interactive associations between HIV-serostatus and PRFs on performance over time.

Results

HIV+ and HIV- women had similar rates of PRFs. Fluency was the only domain where performance over time depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and stress or PTSD (p’s<0.05); not depression. In HIV, higher stress and PTSD were associated with a greater cognitive decline in performance (p’s<0.05) versus lower stress and PTSD. Irrespective of time, performance on learning and memory depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and stress or PTSD (p’s≤0.05). In the context of HIV, stress and PTSD were negatively associated with performance. Effects were pronounced on learning among HIV+ women without effective treatment or viral suppression. Regardless of time or HIV-serostatus, all PRFs were associated with lower speed, global NP, and executive function.

Conclusions

More than depression, perceived stress and PTSD symptoms are treatment targets to potentially improve fluency, learning, and memory in women living with HIV particularly when HIV treatment is not optimal.

Keywords: Stress, HIV, learning, memory, women, cognition

Introduction

Negative life stressors such as childhood trauma and adult physical and sexual violence are prevalent among HIV-infected (HIV+) women[1–5]. These stressors increase susceptibility to mood and anxiety disorders[6–8] and contribute to perturbations in cognition and brain functioning[9, 10]. Among HIV+ women, psychological risk factors (PRFs), including perceived stress, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and depressive symptoms, are associated with deficits in verbal learning, memory, and attention[11–14]. Cross-sectional results from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS, n=1505), showed an interaction between PRFs and HIV status, such that perceived stress and anxiety were more strongly associated with deficits in learning and memory among HIV+ compared to HIV- women. By contrast, depressive symptoms were associated with a similarly lower level of cognitive performance in HIV+ and HIV- women. This pattern of behavioral effects suggests that the neurobiological effects of PRFs on cognition differs between HIV+ and HIV- women, potentially through differences in stress responsivity and immune function. Stress, PTSD, and depression influence the adaptive immune response in HIV+ women, but stress may have a stronger influence than depression because stress is more strongly associated with regulatory mechanisms necessary to maintain immune cell homeostasis[15] which may impact brain homeostasis[16]. Consistent with that view, our neuroimaging studies in the WIHS suggest that HIV, perceived stress and post-traumatic stress, individually and in combination, affect the structure and function of the prefrontal cortex, regions dense in receptors that bind to the stress hormone, glucocorticoids[17, 18].

PRFs and cognitive performance may change over time in HIV+ individuals. Understanding the dynamic nature of these associations over time is important to determine the reliability of associations across successive time-points and to determine whether associations become weaker or stronger over time, or show the same magnitude over time. We sought to examine the interactive associations between HIV and PRFs on cognitive functioning over time in a large cohort of women. Here we present the first series of longitudinal analyses examining these interactions in the WIHS cohort across three cognitive assessments conducted over a 4-year period. Given our previous cross-sectional results[12, 14], we hypothesized that the negative effect of PRFs on cognition would be greater in the context of HIV. Moreover, given our cross-sectional findings, we expected that perceived stress and post-traumatic stress would exacerbate HIV-associated cognitive compromise particularly for verbal memory and this relationship would become stronger over time[13, 17, 18].

Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the WIHS, a longitudinal, multi-site cohort study of the natural and treated history of HIV+ and HIV- women (http://wihshealth.org). Study enrollment occurred in two waves. The first wave occurred between October 1994 and November 1995 and the second between October 2001 and September 2002 from six sites (Brooklyn, Bronx, Chicago, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco). Detailed information regarding recruitment procedures and eligibility criteria have been previous published[19, 20].

Primary Predictor Variables

Concurrent with the neuropsychological (NP) test battery, questionnaires were administered measuring perceived stress, PTSD symptoms, and depressive symptoms. Stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a 10-item scale that assesses the degree to which life situations in the previous month are evaluated as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded (Likert scale, 0=never, 4=very often)[21, 22]. Consistent with our previous work[14, 17, 18], the PSS-10 was dichotomized and considered to be higher when scores were in the top tertile (present sample ≥ 20 points) and lower when in the bottom two tertiles (<20 points). PTSD symptoms were measured with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C), a 17-item measure of PTSD symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal) as defined by DSM-IV[23]. As in our previous work[13], probable PTSD was defined as meeting DSM-IV symptom criteria in the previous month (≥1 B item—re-experiencing, ≥3 C items—avoidance, & ≥2 D items—arousal) and the total severity score >44. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Elevated depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks was defined using a standard cutoff score of 16[24, 25] which we have also used in our previous work[12, 17, 26].

Cognitive Outcomes

Beginning in 2009, certified study personnel administered three longitudinal NP assessments to WIHS participants biennially over a 4-year period. The cognitive domains included learning and memory (primary outcomes of interest given previous cross-sectional studies[12–14, 17, 18]), attention, executive function, fluency, psychomotor speed, and motor skills. Table 1 provides the specific tests and outcomes used to assess each domain. Following methods used in other large HIV cohort studies[11–14], demographically adjusted T-scores were derived for each individual outcome adjusting for age, years of education, Wide Range Achievement-3 reading subtest (WRAT, measure of premorbid intellect), race (African American vs not), ethnicity (Hispanic vs not), and number of times the test had been administered in WIHS. Prior to the creation of T-scores, all timed outcomes were log transformed to normalize the distributions and then reverse scored so that higher scores equated to better performance across all domains. For each domain, a composite T-score was derived by averaging the T-scores for domains with ≥2 outcomes. If only one test in a domain was completed, the T-score for that test was used. A global NP composite T-score was derived for individuals who had T-scores for at least 4 out of 6 cognitive domains.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological tests administered to Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) participants between 2009 and 2013.

| Domain | Neuropsychological Test | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Verbal learning | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) | Total learning across trials |

| Verbal memory | HVLT-R | Delay free recall |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Attention/working memory | Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS) | Total correct for experimental condition |

| Total correct for control condition | ||

| Executive function | Trail Making Test Part B | Time to completion |

| Stroop Test Trial 3 | Time to completion | |

| Psychomotor speed | Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) | Total correct |

| Stroop Test Trial 2 | Time to completion | |

| Verbal fluency | Letter fluency (F, A, S) | Total correct words generated |

| Semantic fluency | Total correct animals generated | |

| Fine motor skills | Grooved Pegboard | Average time to complete dominant and non-dominant hand |

Statistical Analyses

A series of mixed-effects regression models (MRM) were used to examine whether PRFs altered the pattern of NP performance (domain-specific and global cognitive T-scores) for HIV+ and HIV- women. Temporal ordering was structured into the analysis by the nature of the self-reported questionnaires used. For example, the PSS-10 and PCL-C assess stress and PTSD symptoms in the past month whereas the CES-D assesses depressive symptom in the past two weeks. MRMs were selected to handle the repeated measurements of individuals over time and the nesting of individuals within site. Three primary sets of analyses were conducted—one for each of the three PRFs (PSS-10, PCL-C and CES-D) which was done to avoid the issue of multicollinearity between measures (correlations ranged between 0.65 and 0.75). For each set of analyses, the primary predictor variables included the PRFs (time-varying predictor), HIV-serostatus, Time, and all two- and three-way interactions. Higher order interactions with non-significant p-values (based on an alpha of p≤0.05) were dropped one at a time in order of decreasing p-value size. If there were no significant interactions with Time, the average effects of the PRF and HIV-serostatus were also reported (Supplemental Tables 1, 2, and 3 for all final MRM models). All analyses included a standard set of covariates[11] including: wave of enrollment (1994–1995, 2001–2002), self-reported annual household income (≤$12,000, >12,000, and missing), harmful alcohol use (>7 drinks/week or ≥4 drinks in one sitting), smoking status (current refers to within the past week, former, never), marijuana use, and crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use (recent refers to within 6 months of the most recent WIHS visit, former, never), psychiatric antidepressant/antipsychotic medication (0, 1, or 2 medications), and positive Hepatitis C antibody. Observations were trimmed where the studentized residuals were >|4.5| to ensure effects were not driven by extreme values (<1% of observations for only motor skills and speed). When the interaction between HIV serostatus and a PRF were significant on a domain, planned analyses of HIV+ women only were conducted to examine interactions between PRFs and a standard set[11] of HIV-related characteristics including current HIV RNA (undetectable, <10,000copies/ml, ≥10,000 copies/ml; determined using COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ; Oct 2008 through March 2011 sensitive to 48cp/ml; April 2011 to present sensitive to 20cp/ml), nadir and current CD4 cell count (<200, 200–500, >500), reported clinical AIDS diagnosis, years on ART, proportion of total WIHS visits with undetectable HIV RNA, cART use and adherence (cART use+≥95 adherence, cART use+<95% adherence, no cART), and current Efavirenz use because of documented NP side effects. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4. Significance was set at p<0.05 two-tailed.

Results

Measures of NP performance and concurrent PRFs were available for 946 WIHS participants (646 HIV+ and 300 HIV- women) (Table 1). HIV+ women were significantly but slightly older, more likely to be HCV positive, and reported more antidepressants/antipsychotics use than HIV- women (p’s<0.05). HIV+ women were also less likely to engage in recent heavy alcohol use as well as recent marijuana use compared to HIV- women (p’s<0.05). All factors were included as covariates in the primary analyses except age which was accounted for in the creation of the T-score.

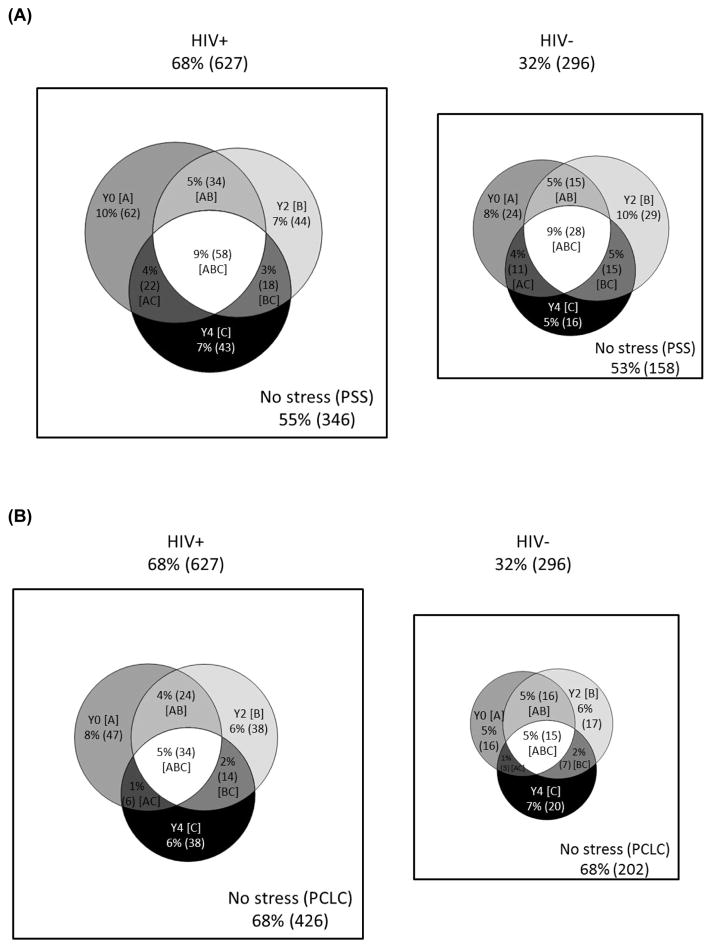

Longitudinal patterns of PSS-10, PCL-C, and CES-D were similar for HIV+ and HIV- women (Figure 1). Specifically, among HIV+ women, 55% had PSS-10 scores in the bottom two tertiles (<20 points) at all 3 NC visits, 36% had PSS-10 scores in the top tertile (≥20 points) at 1 or 2 visits, and 9% had PSS-10 in the top tertile at all 3 visits compared to 53%, 37% and 9% among HIV- women. For PCL-C, 27% of HIV+ and 27% of HIV- had probable PTSD at 1 or 2 visits; 5% of HIV+ and 5% of HIV- had probable PTSD at all 3 visits. Among HIV+ women, 32% had elevated CES-D at 1 or 2 visits and 12% at all 3 visits compared to 32% and 10% among HIV- women.

Figure 1.

(A) Comparative Venn diagrams depicting perceived stress exposures over time. Cells are mutually exclusive. Stress indicated by PSS-10 at [A] Y0 (baseline only); [B] Y2 (year 2 only); [C] Y4 (year 4 only); [AB] Y0 and Y2; [AC] Y0 and Y4; [BC] Y2 and Y4; [ABC] Y0, Y2, and Y4. PSS-10=Perceived Stress Scale-10

(B) Comparative Venn diagrams depicting post-traumatic stress exposures over time. Cells are mutually exclusive. Stress indicated by PCL-C at [A] Y0 (baseline only); [B] Y2 (year 2 only); [C] Y4 (year 4 only); [AB] Y0 and Y2; [AC] Y0 and Y4; [BC] Y2 and Y4; [ABC] Y0, Y2, and Y4. PCL-C=PTSD symptom checklist

(C) Comparative Venn diagrams depicting depression exposures over time. Cells are mutually exclusive. Depression indicated by CES-D at [A] Y0 (baseline only); [B] Y2 (year 2 only); [C] Y4 (year 4 only); [AB] Y0 and Y2; [AC] Y0 and Y4; [BC] Y2 and Y4; [ABC] Y0, Y2, and Y4. CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression

Separate and Interactive Effects of HIV-serostatus and PRFs on NP Performance

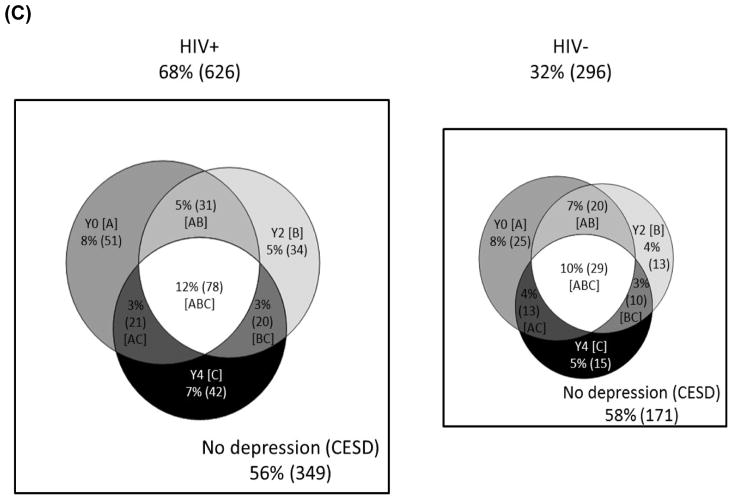

Verbal fluency was the only cognitive domain where the magnitude of change in performance over time depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and stress or PTSD (p’s<0.05; Figure 2). For both the PSS-10 and PCL-C, the PRF by time interaction was significant for HIV+ (p’s<0.05) but not HIV- women (p’s>0.37). Restricting the follow-up to HIV+ women, higher PSS-10 (B[unstandardized beta]=−0.7, SE[standard error]=0.3, p=0.02) and PTSD (B=−0.9, SE=0.4, p=0.02) were associated with a greater decline in performance over time compared to lower PSS-10 (B=−0.3 SE=0.2, p=0.07) and no PTSD (B=−0.4, SE=0.2, p=0.40). Essentially, the effect of PSS-10 and PCL-C is not apparent until 4 years. There was no cognitive domain where the magnitude of change in performance over time depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Performance on verbal fluency over time was dependent on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and psychological risk factors (perceived stress, post-traumatic stress).

Note. PSS-10=Perceived Stress Scale-10; PCL-C=PTSD symptom checklist. *significant difference at p<0.05.

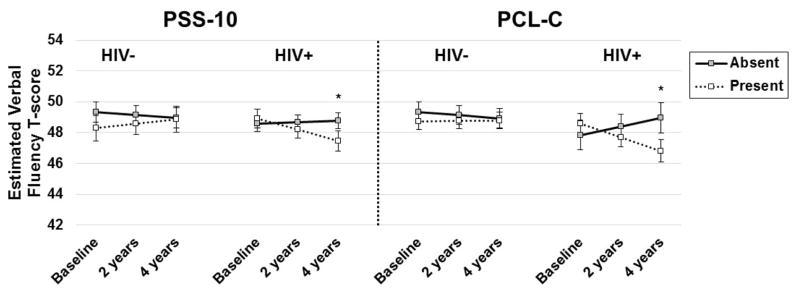

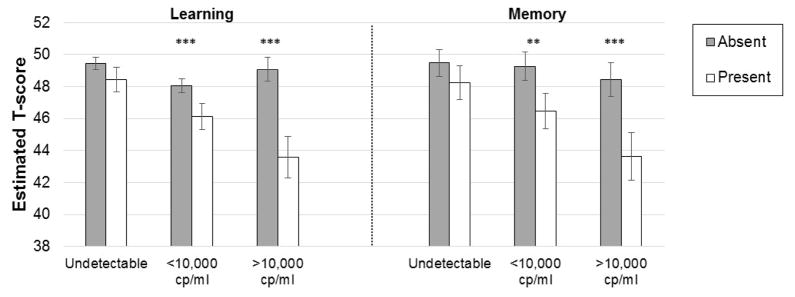

Regardless of time, performance on the two primary domains of interest—verbal memory and learning depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and stress or PTSD (Figure 3). Across time points, higher PSS-10 was associated with lower performance on memory among HIV+ (B=−1.3, SE=0.5, p=0.009) but not HIV- women (B=0.4, SE=0.7, p=0.59). Across time points, PTSD associated with lower performance on both learning (B=−2.7, SE=0.6, p<0.0001) and memory (B=−2.4, SE=0.6, p<0.0001) among HIV+ but not HIV- women (p’s>0.31). While PTSD was associated negatively with executive function in both HIV+ (B=−1.1, SE=0.4, p=0.01) and HIV- women (B=−2.8, SE=0.6, p<0.0001), the magnitude of the association was greater among HIV- compared to HIV+ women (p=0.04). Additionally, performance on attention/working memory depended on the combined influence of HIV-serostatus and CES-D (p=0.01). On average, elevated depressive symptoms were associated with lower performance among HIV- (B=−2.4, SE=0.7, p<0.001) but not HIV+ women (B=−0.7, SE=0.5, p=0.12).

Figure 3.

Performance on neuropsychological functioning was dependent on HIV-serostatus and psychological risk factors (perceived stress, post-traumatic stress, and depressive symptoms).

Note. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05; PSS-10=Perceived Stress Scale-10; PCL-C=PTSD symptom checklist; CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression.

Regardless of time or HIV-serostatus, PRFs were associated with lower performance on a number of domains. On average, higher PSS-10 was associated with lower performance on global function (B=−0.9, SE=0.02, p<0.0001), verbal learning (B=−1.2, SE=0.04, p=0.004), attention/working memory (B=−1.1, SE=0.04, p=0.004), executive function (B=−1.1, SE=0.03, p<0.0001), and psychomotor speed (B=−1.4, SE=0.3, p<0.0001). On motor function, performance improved over time with lower PSS-10 (B=0.7, SE=0.3, p=0.02) compared to higher PSS-10 (B=−0.8, SE=0.5, p=0.17). A similar, but slightly stronger pattern was noted on the PCL-C. Across time points, PTSD was associated with lower performance on global function (B=−1.4, SE=0.2, p<0.0001), attention/working memory (B=−2.4, SE=0.5, p<0.0001), psychomotor speed (B=−1.8, SE=0.3, p<0.0001), and motor function (B=−1.2, SE=0.5, p=0.009). For the CES-D elevated depressive symptoms were associated with lower performance on global function (B=−1.4, SE=0.2, p<0.0001), memory (B=−1.4, SE=0.4, p=0.001), executive function (B=−1.6, SE=0.3, p<0.0001), psychomotor speed (B=−1.4, SE=0.3, p<0.0001), verbal fluency (B=−1.0, SE=0.3, p= 0.002), and motor function (B=−2.0, SE=0.4, p<0.0001) across time points.

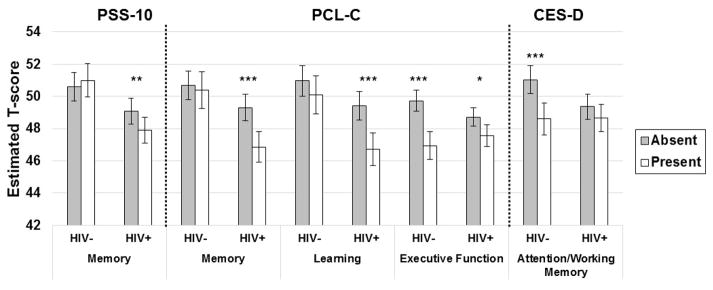

In subanalyses among HIV+ women, HIV-related characteristics did not moderate the association of PSS-10 on verbal memory. However, current viral load moderated the effects of PTSD on both verbal learning (p=0.04) and verbal memory (p=0.03); the negative association of PTSD on verbal learning and verbal memory was only present when women had a detectable HIV RNA (Figure 4). Additionally, cART use/adherence (p=0.005) and the proportion of virally suppressed visits in WIHS (p=0.04) moderated the association between PTSD and verbal learning. Specifically, the negative association of PTSD with verbal learning was only present when women were not receiving cART or when women on cART reported non adherence (<95% adherence). Finally, a greater proportion of visits with viral suppression was associated with better verbal learning (p=0.001) but only when women did not have PTSD.

Figure 4.

The average negative association of post-traumatic stress (present vs. absent) on verbal learning and memory is moderated by current HIV RNA.

Note. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we provide evidence consistent with our cross-sectional findings[14] that elevated perceived stress and PTSD symptoms in the context of HIV are linked to alterations in verbal abilities (learning, memory, fluency) but not to other cognitive domains measured in this study. In individuals with HIV, the presence of perceived stress or PTSD symptoms compared to the absence of these factors are associated with a greater decline in verbal fluency over time and persistent negative effects on verbal learning and memory. Our results suggest that the effects of perceived and PTSD symptoms on fluency performance may be more delayed and require the occurrence of chronic periods of stress whereas verbal learning and memory may be more impacted by acute periods of stress in the context of HIV. Our findings suggest that perceived stress and PTSD symptoms, more so than depressive symptoms, may contribute to different patterns of detrimental NP performance (stably declining or persistent impairment) among HIV+ individuals[27]. Moreover, our findings suggest that perceived stress and PTSD symptoms are a possible treatment target for improving verbal abilities among HIV+ women.

There are a number of possible mechanistic explanations for perceived stress and PTSD symptoms negatively influencing verbal abilities in the context of HIV. One possibility is that HIV and these PRFs may individually or in combination impair cognition in HIV+ women through effects on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Neuroimaging and postmortem studies show that alterations in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex contribute to memory deficits among HIV+ individuals[28–30] and stress may compound these effects on the prefrontal cortex[17, 18]. Additionally, alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the key mediator of the stress response system, may mediate the relationship between these PRFs and memory in HIV+ individuals. Acute and chronic stressors alter the HPA axis, leading to neuronal atrophy in the prefrontal cortex[31, 32]. Additionally, HIV+ individuals show disruptions in the HPA axis including elevated basal cortisol levels[33–37]. Thus, both HIV and chronic stress are associated with disruption in HPA axis activation including elevated basal cortisol level, and the combination of both HIV and stress may have additive or multiplicative effects on HPA dysregulation.

Glucocorticoid receptor function may also play an important role in stress-related memory impairments in HIV+ women. Chronic stress reduces glucocorticoid receptor expression in the hippocampus and frontoparietal cortex although these studies were in males[38, 39]. Animal studies demonstrate the importance of glucocorticoid receptor function to memory. For example, intracellular trafficking of the glucocorticoid receptor is diminished in the hippocampus of aged rats[40], especially in those with hippocampal-related memory impairments[41]. Cumulative over-exposure to glucocorticoids is also associated with age-related prefrontal impairments in rats[42]. Thus, glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction and altered cortisol levels combined could predispose HIV+ women to stress-associated psychiatric disorders and memory impairment linked to glucocorticoid resistance.

Whereas perceived stress, PTSD symptoms, and depressive symptoms were negatively associated with global NP function, unlike perceived stress and PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms did not interact with HIV-serostatus on verbal abilities. Rather, HIV-serostatus moderated the effects of depressive symptoms in the domain of attention/working memory. However, on average, elevated depressive symptoms were associated with worse performance among HIV-, but not HIV+, women. Important to note is that, irrespective of depression symptoms, the attention/working memory performance of HIV+ women was worse than HIV- women without depressive symptoms and similar to HIV- women with depressive symptoms suggesting that the effects of HIV infection on performance overwhelm any negative effect of depressive symptoms. Although it is unclear what drives the pattern of effects, our findings give rise to the greater importance of targeting perceived stress and PTSD symptoms among HIV+ compared to HIV- individuals.

In HIV+ women, perceived stress and PTSD symptoms may have a stronger influence on HPA axis regulation and immune function compared to depressive symptoms. Although CD4 cell count is associated with both higher self-reported perceived stress, worry, and depressive symptoms, regulatory T cells are associated with higher self-reported perceived stress and worry but not depressive symptoms[15]. Thus, although both stress, worry, and depression appear to be associated with the overall adaptive immune response in HIV+ women, stress and worry appears to be more strongly associated with regulatory mechanisms essential to maintain immune cell homeostasis[15] which may impact brain homeostasis[16].

Among HIV-related clinical characteristics, the strongest modifiers of the effect of PRFs on verbal learning and memory were current HIV RNA, cART use and adherence, and the proportion of time a woman achieves viral suppression over time. Specifically, the associations of PTSD symptoms with learning and memory were most pronounced among women with detectable HIV RNA and women who were not on cART nor adherent to their cART regimen. These findings are consistent with animal studies demonstrating that high levels of glucocorticoid exposure augment the negative effects of the neurotoxic viral protein, gp120, in the hippocampus through release of toxins by microglia[43, 44].

The primary limitation is that we utilized self-report screeners of PTSD and depression rather than a structured diagnostic interview. Although studies indicate the CES-D and PCL-C are valid and reliable markers of mental health disorders, we have not validated scores in the WIHS. It is possible that the CES-D and PCL-C inventories may overestimate the number of individuals meeting criteria for a clinical diagnosis. Finally, our symptom-based measures may capture many mechanistic pathways linking mental health to cognition including inflammation and disordered sleep. Current and lifetime psychiatric diagnostic data are now available in the WIHS HIV+ women which will allow us to further examine whether associations we identified between mental health symptom based screening measures and NC performance are similar. Longer term follow-up is also needed to further determine the predictive nature of PRFs on cognition in HIV+ and HIV- women. Finally, other cognitive domains including social cognition may be impacted by PRFs in HIV+ and HIV- women, however, other domains such as visuospatial abilities and emotion processing were not part of the neurocognitive test battery administered in the WIHS.

In sum, HIV+ women are vulnerable to deficits in verbal abilities including verbal learning and memory. High perceived stress and PTSD symptoms, but not depressive symptoms, appear to be consistently linked to worse performance on these domains in the context of HIV. Stress reduction and post-traumatic stress prevention and treatment programs could help improve and maintain learning and memory function in women living with HIV and in turn may contribute to optimal HIV treatment adherence and viral suppression.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Demographics and other descriptive information about the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) participants as a function on HIV status at the first neuropsychological test administration which occurred between 2009 and 2011.

| HIV-uninfected (n=300) | HIV-infected (n=646) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.1 (9.9) | 46.5 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 12.3 (3.0) | 12.5 (2.9) | 0.40 |

| WRAT-3 reading subtest, mean (SD) | 89.7 (18.0) | 91.9 (17.8) | 0.08 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 207 (69) | 425 (66) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 21 (7) | 80 (12) | |

| Hispanic | 59 (20) | 111 (17) | |

| Other | 13 (4) | 30 (5) | |

| Annual household income ≤12,000/year, n (%) | 146 (49) | 290 (45) | 0.54 |

| Higher perceived stress, n (%) | 79 (26) | 183 (28) | 0.52 |

| PTSD symptoms, n (%) | 51 (17) | 116 (18) | 0.72 |

| Elevated depressive symptoms, n (%) | 88 (29) | 192 (30) | 0.89 |

| Antidepressant/Antipsychotic medication | <0.001 | ||

| None | 250 (83) | 466 (72) | |

| 1 | 36 (12) | 131 (20) | |

| 2 | 14 (5) | 49 (8) | |

| Any history of past abuse | 197 (68) | 414 (67) | 0.78 |

| History of sexual abuse | 114 (39) | 265 (43) | 0.32 |

| History of physical violence | 160 (55) | 338 (55) | 0.93 |

| History of domestic coercion | 101 (35) | 246 (40) | 0.15 |

| Hepatitis C RNA positive, n (%) | 39 (13) | 137 (21) | 0.003 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Current | 88 (29) | 173 (27) | |

| Former | 148 (49) | 261 (40) | |

| Never | 64 (21) | 212 (33) | |

| Recent harmful alcohol use, n (%) | 70 (23) | 103 (16) | 0.006 |

| Marijuana use, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Recent | 76 (25) | 95 (15) | |

| Former | 162 (54) | 384 (59) | |

| Never | 62 (21) | 167 (26) | |

| Crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use, n (%) | 0.08 | ||

| Recent | 31 (10) | 40 (6) | |

| Former | 151 (50) | 336 (52) | |

| Never | 118 (39) | 270 (42) | |

| HIV medication | - | ||

| HAART | 489 (76) | ||

| Mono/combination | 9 (1) | ||

| No medication | 146 (23) | ||

| Current Efavirenz use | - | 149 (23) | |

| Nadir CD4 count in WIHS, median (IQR) | - | 201 (212) | |

| Current CD4 count, median (IQR) | - | 521 (401) | |

| HIV RNA, Median (IQR) | - | 48 (966) | |

| Proportion of WIHS visits, M (SD) | |||

| HIV RNA <500 copies/mL | - | 53 (29) | |

| On HAART | 59 (32) | ||

| Adherence (≥95%) to ART, n (%) | - | 425 (85) | |

| ART duration (years), M (SD) | - | 7.3 (6.3) | |

| HAART duration (years), M (SD) | - | 6.2 (5.6) | |

| Reported AIDS diagnosis, n (%) | - | 270 (42) | |

Note.

Main effect of HIV Status is significant at p<0.05. WRAT-3=Wide Range Achievement Test standard score; current refers to within the past week; recent, refers to within 6 months of the most recent WIHS visit; heavy alcohol use reflects >7 drinks/week or ≥4 drinks in one sitting; WIHS=Women’s Interagency HIV Study; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder. ART=antiretroviral therapy; IQR=interquartile range; Variables reported as n (%) were analyzed with Chi-square tests. Variables reported as M (SD) were analyzed with independent t-tests. Variables reported as median/IQR were analyzed with Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Cases missing any history of abuse (sexual, physical violence, domestic coercion)=38, history of sexual abuse=43, sexual abuse as a kid=73, physical violence=40, domestic coercion=38.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: Dr. Rubin’s effort was supported by Grant Number 1K01MH098798-01 and Dr. Valcour’s by K24MH098759, each from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Michael Saag, Mirjam-Colette Kempf, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004, Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson); U01-AI-031834, Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French); U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397, UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora); U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA) and UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA).

Footnotes

Author contribution

Drs. Rubin and Maki conceived the study idea. Dr. Rubin takes responsibility for the integrity of the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Financial Disclosures Dr. Valcour has served as a consultant to Merck and ViiV healthcare on topics related to HIV and aging.

References

- 1.Brief DJ, Bollinger AR, Vielhauer MJ, Berger-Greenstein JA, Morgan EE, Brady SM, et al. Understanding the interface of HIV, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use and its implications for health outcomes. AIDS Care. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S97–120. doi: 10.1080/09540120412301315259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spies G, Afifi TO, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Sareen J, Seedat S. Mental health outcomes in HIV and childhood maltreatment: a systematic review. Systematic reviews. 2012;1:30. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, Weiss DS. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2091–2100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, Richardson J, Young M, Holman S, et al. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):560–565. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker MR, Benning L, Weber KM, Sherman SG, Adedimeji A, Wilson TE, et al. Physical and Sexual Violence Predictors: 20 Years of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study Cohort. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neigh GN, Gillespie CF, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiological toll of child abuse and neglect. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(4):389–410. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heim C, Shugart M, Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52(7):671–690. doi: 10.1002/dev.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penza KM, Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological effects of childhood abuse: implications for the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masson M, East-Richard C, Cellard C. A meta-analysis on the impact of psychiatric disorders and maltreatment on cognition. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(2):143–156. doi: 10.1037/neu0000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(4):305–315. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Valcour V, Martin E, Crystal H, Young M, et al. Cognitive function in women with HIV: findings from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Neurology. 2015;84(3):231–240. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin LH, Sundermann EE, Cook JA, Martin EM, Golub ET, Weber KM, et al. Investigation of menopausal stage and symptoms on cognition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014;21(9) doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin LH, Pyra M, Cook JA, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Martin E, et al. Post-traumatic stress is associated with verbal learning, memory, and psychomotor speed in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(2):159–169. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0380-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin LH, Cook JA, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Martin E, Valcour V, et al. The association of perceived stress and verbal memory is greater in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2015;21(4):422–432. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehm KE, Konkle-Parker D. Association of CD4+ T cell subpopulations and psychological stress measures in women living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1281880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Groot NS, Burgas MT. Is membrane homeostasis the missing link between inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases? Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2015;72(24):4795–4805. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2038-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin LH, Wu M, Sundermann EE, Meyer VJ, Smith R, Weber KM, et al. Elevated stress is associated with prefrontal cortex dysfunction during a verbal memory task in women with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0446-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin LH, Meyer VJ, RJC, Sundermann EE, Wu M, Weber KM, et al. Prefrontal cortical volume loss is associated with stress-related deficits in verbal learning and memory in HIV-infected women. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;92(Pt B):166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. Division NCfPBS, editor. PCL-C for DSM-IV. Boston: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comstock GW, Helsing KJ. Symptoms of depression in two communities. Psychol Med. 1976;6(4):551–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin LH, Cook JA, Grey DD, Weber K, Wells C, Golub ET, et al. Perinatal depressive symptoms in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected women: a prospective study from preconception to postpartum. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(9):1287–1295. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maki PM, Cohen MH, Weber K, Little DM, Fornelli D, Rubin LH, et al. Impairments in memory and hippocampal function in HIV-positive vs HIV-negative women: a preliminary study. Neurology. 2009;72(19):1661–1668. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a55f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castelo JM, Sherman SJ, Courtney MG, Melrose RJ, Stern CE. Altered hippocampal-prefrontal activation in HIV patients during episodic memory encoding. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1688–1695. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218305.09183.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine AJ, Soontornniyomkij V, Achim CL, Masliah E, Gelman BB, Sinsheimer JS, et al. Multilevel analysis of neuropathogenesis of neurocognitive impairment in HIV. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(4):431–441. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0410-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wellman CL. Dendritic reorganization in pyramidal neurons in medial prefrontal cortex after chronic corticosterone administration. Journal of neurobiology. 2001;49(3):245–253. doi: 10.1002/neu.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biglino A, Limone P, Forno B, Pollono A, Cariti G, Molinatti GM, et al. Altered adrenocorticotropin and cortisol response to corticotropin-releasing hormone in HIV-1 infection. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;133(2):173–179. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1330173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verges B, Chavanet P, Desgres J, Vaillant G, Waldner A, Brun JM, et al. Adrenal function in HIV infected patients. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1989;121(5):633–637. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1210633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enwonwu CO, Meeks VI, Sawiris PG. Elevated cortisol levels in whole saliva in HIV infected individuals. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104(3):322–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lortholary O, Christeff N, Casassus P, Thobie N, Veyssier P, Trogoff B, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(2):791–796. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christeff N, Gherbi N, Mammes O, Dalle MT, Gharakhanian S, Lortholary O, et al. Serum cortisol and DHEA concentrations during HIV infection. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22(Suppl 1):S11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herman JP, Adams D, Prewitt C. Regulatory changes in neuroendocrine stress-integrative circuitry produced by a variable stress paradigm. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61(2):180–190. doi: 10.1159/000126839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitraki E, Karandrea D, Kittas C. Long-lasting effects of stress on glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in the rat brain. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;69(5):331–338. doi: 10.1159/000054435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy EK, Spencer RL, Sipe KJ, Herman JP. Decrements in nuclear glucocorticoid receptor (GR) protein levels and DNA binding in aged rat hippocampus. Endocrinology. 2002;143(4):1362–1370. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SY, Hwang YK, Yun HS, Han JS. Decreased levels of nuclear glucocorticoid receptor protein in the hippocampus of aged Long-Evans rats with cognitive impairment. Brain Research. 2012;1478:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson RM, Birnie AK, Koblesky NK, Romig-Martin SA, Radley JJ. Adrenocortical status predicts the degree of age-related deficits in prefrontal structural plasticity and working memory. J Neurosci. 2014;34(25):8387–8397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1385-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yusim A, Franklin L, Brooke S, Ajilore O, Sapolsky R. Glucocorticoids exacerbate the deleterious effects of gp120 in hippocampal and cortical explants. J Neurochem. 2000;74(3):1000–1007. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooke SM, Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoid exacerbation of gp120 neurotoxicity: role of microglia. Exp Neurol. 2002;177(1):151–158. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.