Abstract

Objective

Traditional episodic memory tests employ a delayed recall length ranging from 10-30 minutes. The neurobiological process of memory consolidation extends well beyond these time intervals, however, raising the possibility that these tests might not be fully sensitive to the subtle neurocognitive changes found in early disease or age-related decline. We aimed to determine the sensitivity of a 1-week delayed recall paradigm to medial temporal lobe (MTL) structure among neurologically normal older adults.

Methods

140 functionally intact, older adults (mean age=75.8) completed a story recall test in which participants learned to 90% criterion. Recall was tested after 30-minutes and 1-week. Participants also completed a standardized list learning task with a 20-minute delay and a structural brain MRI. The medial temporal lobe (MTL), including the parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and entorhinal, was our primary region of interest.

Results

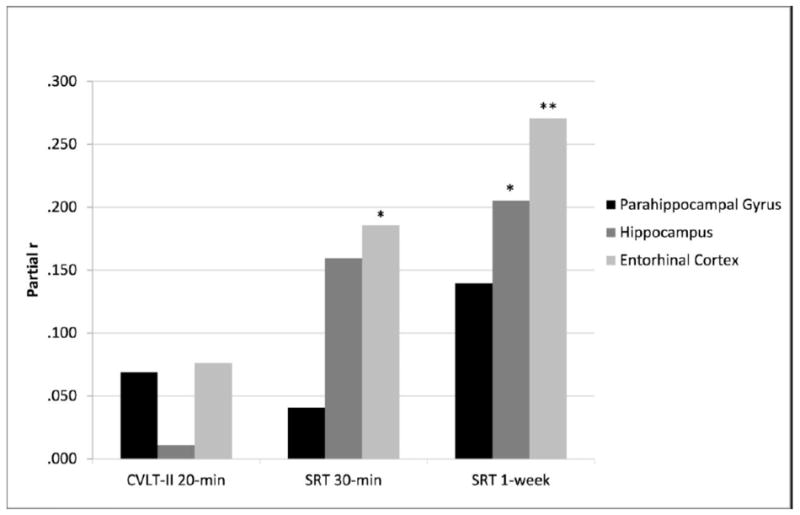

Controlling for age, education, gender and total intracranial volume, the standard 20- and 30-minute recalls showed no significant relationship with MTL. In contrast, 1-week recall was uniquely associated with MTL structure (partial r=0.24, p=0.006), specifically entorhinal (partial r=0.27; p=0.001) and hippocampal (partial r=0.21, p=0.02) volumes.

Conclusion

Memory paradigms that utilize 1-week delays are more sensitive than standard paradigms to MTL volumes in neurologically normal older adults. Longer delay periods may improve detection of memory consolidation abilities associated with age-related, and potentially pathological, neurobehavioral change.

Keywords: Aging, Alzheimer’s disease, Memory consolidation, Entorhinal cortex, Hippocampus, Neuropsychology

Introduction

Consolidation refers to the time-dependent process by which new memories are stabilized following an initial learning experience (Squire & Alvarez, 1995). From a neurobiological perspective, new information is consolidated into long-term memory through two temporally graded processes: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. During initial synaptic consolidation, cellular-level events (e.g., protein synthesis) stabilize learned information in a hippocampal-dependent manner over the course of hours (Davis & Squire, 1984; Platano et. al, 2008). Subsequently, systems consolidation takes place over days to weeks, or even years, during which information becomes gradually reorganized via connections to the neocortex establishing novel neocortical-hippocampal networks (Squire, Genzel, Wixted, & Morris, 2015).

Despite the evidence for an extensive consolidation period, standard assessment of episodic memory in neuropsychology typically utilizes a learning phase during which novel information to be acquired is presented, followed by recall or recognition after delays of only 10-30 minutes (Delis, Freeland, Kramer, & Kaplan, 1988; Wechsler, 1987). One concern this raises is that traditional memory measures that posit to tap into medial temporal lobe-related consolidation abilities may not be sufficient to fully capture temporally-sensitive synaptic or systems consolidation processes. Furthermore, standard delayed recall testing employed in healthy adult cohorts can be vulnerable to ceiling effects that limit variance and impact statistical relationships with other measures (Uttl, Graf, & Richter, 2002). Assessments that detect memory consolidation abilities, particularly subtle and ecologically relevant deficits, in neurologically intact, older adults are difficult to develop and warrant further attention (Spooner & Pachana, 2006).

The issue of optimal delay lengths is particularly salient for our understanding of age-related memory changes. Medial temporal structures, which are integral to memory (Squire, Stark, & Clark, 2004; Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991), are one of the earliest neuroanatomical regions targeted in Alzheimer-related pathogenesis (Du et al., 2004; Kaye et al., 1997; Sperling et al., 2011). Recent studies have demonstrated that cognitively normal adults with smaller baseline volumes of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, as well as increased rates of atrophy in these regions, are at greater risk for the development of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease (Soldan et. al, 2016; Younes, Albert, & Miller, 2014). Recall measures that not only accurately reflect the temporally-graded processes underlying consolidation, but are also sensitive to the neuroanatomical markers that often precede detectable cognitive impairment are critically needed for early detection of memory decline in aging.

The primary purpose of this study is to compare the length of delay periods employed in standard episodic memory testing with longer delay periods. We hypothesized that recall performance at a 1-week delay would be more strongly associated with medial temporal lobe volumes than memory recall at delays of 20-30 minutes, consistent with posited underlying consolidation-specific neurobiological processes.

Methods

Participants

140 neurologically normal, community dwelling older adults (ages: 63-92) were recruited from the University of California San Francisco, Memory and Aging Center. Initial screening included an informant interview and a neurological examination. Participant inclusion was based upon a Clinical Dementia Rating (Morris, 1993) score of 0, no informant report of cognitive decline during the previous year, and no findings during neurological or neuropsychological examination that raised concern for emerging cognitive decline or pathological neurobehavioral syndrome. All subjects were reviewed at a consensus case conference with a neuropsychologist and neurologist (Albert et. al, 2011; McKhann et. al; 2011). Exclusion criteria included syndromic diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), neurological condition that could affect cognition (e.g., epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease), substance use diagnosis in the last 20 years, significant systemic medical illnesses, or current depression (Geriatric Depression Scale ≥15 of 30). All participants provided written informed consent and the UCSF Committee on Human Research approved the study protocol.

Delayed Recall Assessments

Story Recall Test

The story recall test (SRT; Butler et al., 2009; Lezak, 1995) consisted of a 20-unit story that was read to participants for a minimum of five learning trials. After each presentation, participants were asked to immediately recall the story. Once the participant reached a learning criterion of 90% (18 out of 20 units), training on the story was discontinued. In the current study, the number of total learning trials ranged from 5 to 9, with 5 trials as the median and mode. Participants were then asked to recall the story after 30-minute and 1-week delays. The 1-week delay recall was conducted via telephone follow-up during which participants were asked to re-tell the story to the examiner. At the time of the original testing, participants were notified that they would be receiving a phone call one week later but were not told they would be asked to recall the story.

California Verbal Learning Test-second edition

Participants (n=129) also completed the California Verbal Learning Test-second edition (CVLT-II; Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Ober, 2000). On the CVLT-II, individuals were given a list of 16 words to recall across five learning trials and were then asked to recall the words after an interference trial (freely and with semantic cueing) and after a 20-minute delay.

Neuroimaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans were obtained using a 3-Tesla Siemens Tim Trio system equipped with a 12-channel head coil at the UCSF Neuroscience Imaging Center. T1 weighted whole brain images were acquired with a volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (MPRAGE, TR/TE = 2300/3 milliseconds) with 9-degree flip angle, FOV = 256 × 240 mm and 160 slices, and 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm voxel size.

SPM Analysis

MRI scans were segmented using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) 12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) software. A study-specific template was created using the DARTEL toolbox (Ashburner & Ridgway 2007). Tissue maps were normalized to template space through applying concatenated warps from native to study-specific template space and study-specific to template space. The normalized maps were subsequently Jacobian modulated and smoothed. Regions of interest (ROI) volumes were then extracted from the Desikan-Killiany atlas (Desikan et al., 2006). The primary ROIs for this study were bilateral volumes of the parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and entorhinal cortex. These three volumes were then summed to calculate a composite volume for the medial temporal lobe. Additionally, a composite volume of the occipital lobe was calculated to provide a comparison brain region that is not implicated in memory functioning and is typically spared in Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration. The occipital lobe composite was the sum of bilateral volumes of the cuneus, lateral occipital cortex, lingual gyrus and pericalcarine cortex.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using PASW 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Multivariable linear regression models adjusting for age, sex, education, and total intracranial volume were performed to examine relationships between memory scores (i.e., story recall 30-minute and 1-week, CVLT-II 20-minute) and medial temporal lobe (region of interest) and occipital lobe (control region) volumes. In linear regression modeling, normality of the dependent variable is a necessary assumption, while such models are robust to normality of the independent variables. Therefore, despite the mildly skewed variance of one of our independent variables (30-minute recall memory scores), linear regression was selected to model our relationships of interest between memory scores and brain volumes. Immediate recall was not controlled for in the story recall test analyses because all subjects learned to the same 90% criterion. To capture “consolidation” after initial learning effects comparably, CVLT-II trial 5 scores were adjusted for in the CVLT-II 20-minute analysis. We present the regression model unstandardized beta coefficients representing the absolute relationship between memory performance and brain volumes, and additionally calculated standardized Pearson partial r effect sizes to enhance comparability and interpretability of the relationships across the disparate memory scores and brain volumes. We also examined associations between memory scores and volumes of the three MTL subregions (i.e., parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex).

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Our sample of 140 neurologically normal adults was 55% female and 95% White with a mean age of 75.8 years (SD=5.9, Range: 58-92; see Table 1), mean education of 17.4 years (SD=2.1, Range: 12-20), and median Mini-Mental State Examination score of 29 (interquartile range 28-30). On the story recall test, the mean number of story units recalled after 30-minutes and 1-week were 18.4 (SD=1.5) and 12.8 (SD=3.8), respectively (out of 20 possible).

Table 1.

Clinico-demographic characteristics of study sample (n=140).

| Age, y | 75.8 (5.9) |

|

| |

| Education, y | 17.4 (2.1) |

|

| |

| Sex, % F | 55% (77) |

|

| |

| MMSE (median, IQR) | 29 (28, 30) |

|

| |

| CVLT-II | |

| Trial 5 | 12.6 (2.7) |

| 20-minute delay | 11.7 (3.0) |

|

| |

| Story Recall Test (Range 0 to 20) | |

| 30-minute delay | 18.4 (1.5) |

| 1-week delay | 12.8 (3.8) |

|

| |

| Total Avg Medial Temporal Lobe Volume (mm3) | 8974.1 (905.2) |

| Entorhinal Cortex | 2366.5 (311.3) |

| Parahippocampal Gyrus | 1998.2 (204.4) |

| Hippocampus | 4609.4 (447.6) |

Abbreviations: MMSE= Mini-Mental State Examination; CVLT-II= California Verbal Learning Test- Second Edition; Avg= average

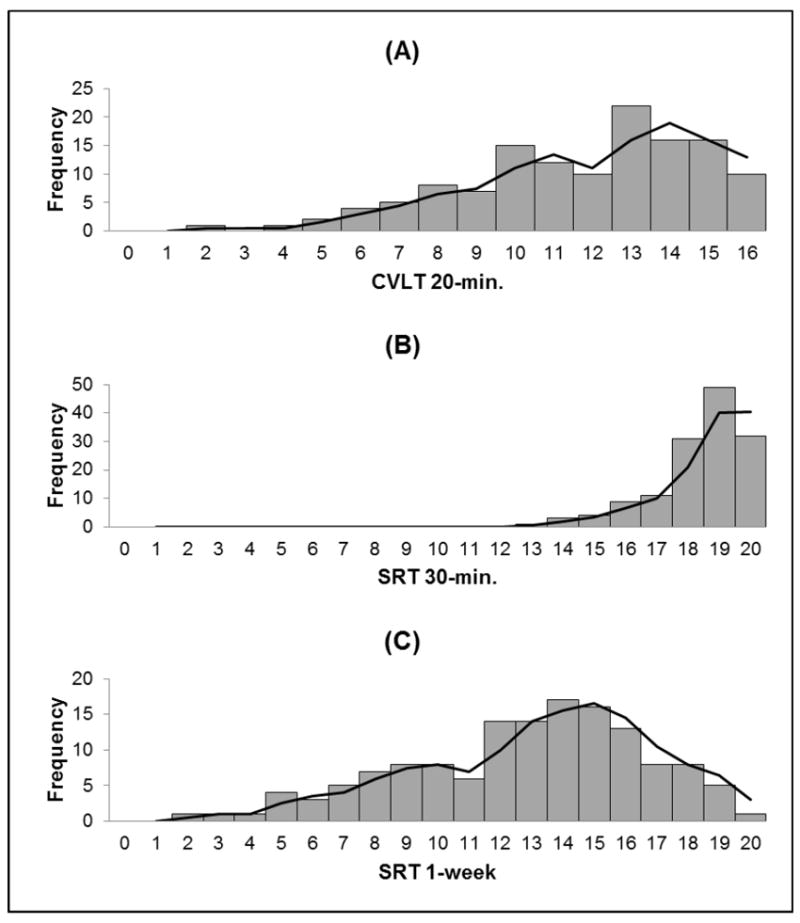

The distribution of 1-week recall scores, with a skewness of -0.518 (SE=0.205), kurtosis of -0.247 (SE=0.407), and variance of 14.714, more closely resembled a normal distribution when compared to the 20 and 30-minute recall scores. The 20 and 30-minute recall scores had a skewness of -0.675 (SE=0.213) and -1.259 (SE=0.205), kurtosis of -0.038 (SE=0.423) and 1.500 (SE=0.407), and variance of 9.180 and 2.240, respectively.

Demographic Correlates of the Story Recall Test at 30 Minute and 1 Week Delays

There were no significant sex differences on story memory recall performance at 30-minutes (t=1.05, p=0.23) or 1-week (t=-1.10, p=0.28). Memory recall at 30-minutes was negatively associated with age (r=-0.25, p=0.003) and positively associated with education (r=0.23, p=0.006). Performance at the 1-week delay was also negatively associated with age (r=-0.31, p<0.001) but had no significant association with education (r=-0.03, p=0.74). As expected, recall after 30-minutes significantly correlated with recall after 1-week (r=0.23, p=0.006).

Neuroanatomic Correlates of 20-30 Minute Delayed Recall

There was a non-significant trend for a relationship between 30-minute recall on the story recall test and medial temporal volume (partial r=0.16, p=0.07). For the CVLT-II, after also including Trial 5 in the model, the relationship between 20-minute delayed recall and medial temporal lobe volumes was not significant (partial r=0.05, p=0.58). Removing Trial 5 as a covariate in the model did not produce a significant relationship (partial r=0.01, p=0.94). Similar non-significant relationships were found when comparing the occipital lobe volumes to 20-minute (partial r=0.13, p=0.15) and 30-minute recall (partial r=0.08, p=0.36).

Neuroanatomic Correlates of 1-Week Delayed Recall

In contrast to the non-significant findings with the 20-30 minute delays, larger medial temporal volumes were significantly associated with better recall on the story recall test after a 1-week delay (partial r=0.24, p=0.006; see Table 2). As expected, the relationship between memory performance at the 1-week delay and occipital lobe volume was not significant (partial r=0.09, p=0.30).

Table 2.

1-week but not 20-30 minute recall performance is uniquely associated with medial temporal lobe volumes among healthy older adults.

| CVLT-II 20-minute Recall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| β | b | 95% CI | p value | Partial r | |

| Age | -0.33 | -48.8 | -68.2, -29.3 | <0.001 | -0.37 |

| Education | -0.07 | 28.1 | -84, 27.2 | 0.314 | -0.01 |

| Sex | 0.03 | 48.2 | -252.7, 349.1 | 0.752 | 0.01 |

| TIV | 0.67 | 5304.5 | 4011.4, 6597.7 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| CVLT T5 | -0.07 | -24.4 | -97.2, 48.5 | 0.509 | -0.04 |

| CVLT 20-min | 0.06 | 17.4 | -45.3, 80.1 | 0.583 | 0.05 |

| Model R2=0.48 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Story Recall Test 30-minute Recall | |||||

|

| |||||

| β | b | 95% CI | p value | Partial r | |

|

| |||||

| Age | -0.26 | -40.4 | -60.3, -20.5 | <0.001 | -0.33 |

| Education | -0.04 | -16.2 | -71.6, 39.2 | 0.564 | -0.05 |

| Sex | <0.01 | 1.4 | -298.5, 301.2 | 0.993 | 0.00 |

| TIV | 0.62 | 5068.3 | 3732.6, 6404.1 | <0.001 | 0.54 |

| SRT 30-min | 0.12 | 75.3 | -4.9, 155.4 | 0.066 | 0.16 |

| Model R2=0.48 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Story Recall Test 1-week Recall | |||||

|

| |||||

| β | b | 95% CI | p value | Partial r | |

|

| |||||

| Age | -0.24 | -36.8 | -56.6, -17 | <0.001 | -0.30 |

| Education | -0.01 | -3.9 | -57.2, 49.5 | 0.886 | -0.01 |

| Sex | -0.01 | -15.3 | -310.6, 280.1 | 0.919 | -0.01 |

| TIV | 0.63 | 5179.6 | 3871.8, 6487.4 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| SRT 1-week | 0.18 | 43.0 | 12.7, 73.3 | <0.01 | 0.24 |

| Model R2=0.49 | |||||

Outcome: Medial Temporal Lobe Volumes

Abbreviations: TIV= total intracranial volume; SRT= Story Recall Test; CVLT T5= Trial 5 of CVLT-II

We also explored the associations between 1-week delay and the individual medial temporal regions to determine if any specific structures were driving the relationship. Story recall scores at the 1-week delay demonstrated significant relationships with entorhinal (partial r=0.27, p=0.001; see Figure 1) and hippocampal volumes (partial r=0.21, p=0.02), but not parahippocampal volumes (partial r=0.14, p=0.11).

Figure 1.

Histograms of memory recall performance at varied delay lengths. The distribution of memory recall at the 1-week delay (Panel c) displayed the most variance and least amount of skewness in comparison to the 20-minute (Panel a) and 30-minute (Panel b) delays.

Discussion

We demonstrate that memory testing utilizing a 1-week delay period is a stronger predictor of MTL volumes (i.e., entorhinal cortex, hippocampus) in older adults than the more commonly used 20-30 minute delays. These data are consistent with the existing neurobiological literature of consolidation, during which length of time delay is a critical factor for the transfer of information through synaptic and network remodeling (Mcgaugh, 2000; Taubenfeld, Wiig, Bear, & Alberini, 1999).

Examination of animal models has begun to elucidate how the memory consolidation process occurs through stages of synaptic and systems consolidation. Operating within the temporal range of minutes to hours after initial memory encoding, synaptic consolidation involves molecular and cellular alterations that increase the robustness of synaptic connections in the MTL (Bailey, Bartsch, & Kandel, 1996). While the cellular adaptations of synaptic consolidation occur within a relatively short timeframe, systems consolidation requires the active reorganization of medial temporal and neocortical networks that can take place anywhere from days to years (Alvarez & Squire, 1994). In the context of our findings, traditional 20-30 minute memory paradigms may not be as sensitive to the cellular and proteomic-level capacities of the MTL that are important for consolidation. On the other hand, the 1-week delay may be more representative of the ability to develop the more stable MTL modifications associated with the important shift from synaptic to systems consolidation. Since our data is cross-sectional, we must also consider the possibility that the 1-week delay is stronger at detecting longstanding capacities of the MTL, as opposed to a shift in MTL capacities due to aging. Along these lines, studies demonstrating that smaller baseline volumes of the MTL predict future rates of MTL atrophy and cognitive decline reinforce the importance of measures that are clinically sensitive to even longstanding MTL structure subtleties (Soldan et. al, 2016; Younes, Albert, & Miller, 2014).

Our data showing that the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus have the strongest relationships with 1-week delayed recall also has important clinical implications. Consolidation dysfunction is the clinical hallmark of AD, and relatedly, extensive in vivo human imaging research document the vulnerability of the medial temporal regions, including the hippocampus and entorhinal to change in normal aging and AD (Du et. al, 2003; Jack et. al, 1998). Pathological studies examining the MTL in AD provide evidence that not only do the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus undergo the greatest amount of atrophy in AD, but also that AD pathology originates in the entorhinal cortex and then advances into the hippocampus (Braak, Alafuzoff, Arzberger, Kretzschmar, & Tredici, 2006; Braak & Braak, 1993; Braak & Braak, 1996; Pennanen et al., 2004). Furthermore, our data parallels the current body of literature examining the sensitivity of 1-week delay memory paradigms in clinical populations. Most notably a recent study demonstrated that individuals with mild cognitive impairment demonstrated impaired 1-week but not 30-minute delayed recall performance in comparison to healthy controls (Walsh et. al, 2014). In conjunction with our data, the findings of Walsh et. al identify memory recall performance at a 1-week delay period as a sensitive behavioral marker to monitor for early detection, and subsequent treatment outcomes, of neurocognitive dysfunction in aging and preclinical AD.

Our study is among the first to investigate memory consolidation over an extended delay period and link it to neurological aging markers in healthy older adults. An additional strength of the memory paradigm is the use of a learning criterion that allowed for measurement of delayed recall as a function of consolidation uninfluenced by variations in immediate recall (i.e., initial learning comparable at 80% across all participants). We acknowledge several limitations to this study. Given that our data is cross-sectional and associative, we cannot determine the directionality of the relationships between delayed recall and these neuroanatomic processes. Furthermore, the observed effect sizes between a 1-week delay and MTL regions were small to medium suggesting that other factors are importantly playing a role in predicting our brain regions of interest. Nonetheless, our data support an objective behavioral marker of brain regions susceptible to aging and AD that could be used to help diagnosed and medial temporal lobe status. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the longer term implications of baseline weaknesses in memory consolidation after 1-week. Although we believe the implementation of a 1-week delay period to be a major strength of this study, it should be noted that participants were assessed over the phone after one week, while testing at 20-30 minute delay periods took place in-person. Accordingly, we cannot rule out the possibility that the more robust 1-week delay relationship with MTL structure was influenced by environmental differences between story learning (in-person) and 1-week delay (over the phone). Contextual changes in learning environment may increase the inherent difficulty of the 1-week delay as compared to 30-minute delay. Nonetheless, our data support the initial feasibility and validity of memory assessment over the phone; such assessments may have higher ecological validity and better capture real-world MTL functioning. Lastly, while our neuroanatomic correlates reflect MTL structure, they do not measure MTL function. As a result, we are restricted in our ability to interpret how MTL regions process memory consolidation. Despite controlling for age, education, gender and intracranial volume, we must still acknowledge the potential for additional external variables (e.g., exercise, inflammation) to impact brain structure and memory performance through independent mechanisms.

In our sample of neurologically normal older adults, memory performance at a 1-week delay period had stronger relationships with MTL volumes than recall after 20-30 minute delays. Our results suggest that the extension of delay periods in clinical assessment may improve our sensitivity to subtle functioning in two markers of early AD pathology, poor memory consolidation and MTL atrophy in functionally intact, older adults. Our findings also suggest that future studies investigating memory consolidation may benefit by controlling for initial learning (e.g., learning to 90% criterion), thus separating recall from initial acquisition. Future studies are needed to investigate the sensitivity of 1-week delay periods to additional neurodegenerative biomarkers (e.g., Aβ, tau) and would benefit from the inclusion of MCI and AD groups to capture the full continuum of clinical staging. By implementing modifications in delay periods to the current benchmarks in memory assessment, we may improve our ability to assist older adults at the onset of cognitive decline.

Figure 2.

Neuroanatomic correlates of memory consolidation at varied delay lengths. Effect sizes were largest for all medial temporal lobe subregions at the 1-week delay.

Note. Partial r values covaried for age, sex, gender, intracranial volumes and CVLT-II trial 5 scores (CVLT-II 20-min. analysis only); CVLT-II 20-min= California Verbal Learning Test- Second Edition Long Delay Free Recall; SRT 30-min/1-week= Story Recall Test 30-minute/1-week Delay; *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIH-NIA grants NIA R01AG032289 (PI: Kramer), R01AG048234 (PI: Kramer), UCSF ADRC P50 AG023501 and the Larry L. Hillblom Network Grant for the Prevention of Age-Associated Cognitive Decline 2014-A-004-NET (PI: Kramer).

Footnotes

Disclosures

J. H. Kramer receives royalties from Pearson, Inc. for the California Verbal Learning Test.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Petersen RC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez P, Squire LR. Memory consolidation and the medial temporal lobe: A simple network model. Neurobiology. 1994;91:7041–7045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Ridgway GR. Symmetric diffeomorphic modeling of longitudinal structural MRI. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2012.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bailey CH, Bartsch D, Kandel ER. Toward a molecular definition of long-term memory storage Memory Has at Least Two Major Forms. 1996;93:13445–13452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathologica. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Braak H, Braak E, Bohl J. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Eur Neurol. 1993;33:403–408. doi: 10.1159/000116984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, Braak H. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1996;165:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CR, Bhaduri A, Acosta-Cabronero J, Nestor PJ, Kapur N, Graham KS, Zeman AZ, et al. Transient epileptic amnesia: Regional brain atrophy and its relationship to memory deficits. Brain. 2009 doi: 10.1093/brain/awn336. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davis HP, Squire LR. Protein synthesis and memory: a review. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:518–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Killiany RJ, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Du AT, Schuff N, Kramer JH, Ganzer S, Zhu XP, Jagust WJ, Weiner MD, et al. Higher atrophy rate of entorhinal cortex than hippocampus in AD. Neurology. 2004;62:422–427. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106462.72282.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du AT, Schuff N, Zhu XP, Jagust WJ, Miller BL, Reed BR, Weiner MW, et al. Atrophy rates of entorhinal cortex in AD and normal aging. Neurology. 2003;60(3):481–486. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000044400.11317.ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu Y, O’brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E, et al. The rate of medial temporal lobe atrophy in typical aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51(4):993–999. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye JA, Swihart T, Howieson D, Dame A, Moore MM, Karnos T, Sexton G, et al. Volume loss of the hippocampus and temporal lobe in healthy elderly persons destined to develop dementia. Neurology. 1997;48:1297–1304. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mcgaugh JL. Memory- a Century of Consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–252. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2412. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen C, Kivipelto M, Tuomainen S, Hartikainen P, Hanninen T, Laakso MP, Soininen H, et al. Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in mild cognitive impairment and early AD. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004 doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00084-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Platano D, Fattoretti P, Balietti M, Giorgetti B, Casoli T, Di Stefano G, Aicardi G, et al. Synaptic Remodeling in Hippocampal CA1 Region of Aged Rats Correlates with Better Memory Performance in Passive Avoidance Test. Rejuvenation Research. 2008;11(2):341–348. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0725. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2008.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Lu Y, Wang M, Selnes O, Albert M, Miller MI, et al. Relationship of medial temporal lobe atrophy, APOE genotype, and cognitive reserve in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016 doi: 10.1002/hbm.22810. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Phelps CH, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia : The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner DM, Pachana NA. Ecological validity in neuropsychological assessment : A case for greater consideration in research with neurologically intact populations. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.04.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Alvarez P. Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation : a neurobiological perspective. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1995;5:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Genzel L, Wixted JT, Morris RG. Memory consolidation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021766. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Squire LR, Stark CEL, Clark RE. THE MEDIAL TEMPORAL LOBE *. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:279–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144130. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubenfeld SM, Wiig KA, Bear MF, Alberini CM. A molecular correlate of memory amnesia in the hippocampus. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:309–310. doi: 10.1038/7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttl B, Graf P, Richter LK. Verbal Paired Associates tests limits on validity and reliability. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2002;17(6):567–581. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6177(01)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CM, Wilkins S, Magouirk Bettcher B, Butler CR, Miller BL, Kramer JH, et al. Memory consolidation in aging and MCI after 1 week. 2014 doi: 10.1037/neu0000013. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wechsler D. WMS-R: Wechsler memory scale-revised. Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Younes L, Albert M, Miller MI. NeuroImage : Clinical Inferring changepoint times of medial temporal lobe morphometric change in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. YNICL. 2014;5:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.04.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]