Abstract

Background

Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) such as osimertinib are the last line of targeted treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) EGFR-mutant harboring T790M. Different mechanisms of acquired resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs have been proposed. It is therefore crucial to identify new and effective strategies to overcome successive acquired mechanisms of resistance.

Methods

For Amplicon-seq analysis, samples from the index patient (primary and metastasis lesions at different timepoints) as well as the patient-derived orthotopic xenograft tumors corresponding to the different treatment arms were used. All samples were formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded, selected and evaluated by a pathologist. For droplet digital PCR, 20 patients diagnosed with NSCLC at baseline or progression to different lines of TKI therapies were selected. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks corresponding to either primary tumor or metastasis specimens were used for analysis. For single-cell analysis, orthotopically grown metastases were dissected from the brain of an athymic nu/nu mouse and cryopreserved at −80°C.

Results

In a brain metastasis lesion from a NSCLC patient presenting an EGFR T790M mutation, we detected MET gene amplification after prolonged treatment with osimertinib. Importantly, the combination of capmatinib (c-MET inhibitor) and afatinib (ErbB-1/2/4 inhibitor) completely suppressed tumor growth in mice orthotopically injected with cells derived from this brain metastasis. In those mice treated with capmatinib or afatinib as monotherapy, we observed the emergence of KRAS G12C clones. Single-cell gene expression analyses also revealed intratumor heterogeneity, indicating the presence of a KRAS-driven subclone. We also detected low-frequent KRAS G12C alleles in patients treated with various EGFR-TKIs.

Conclusion

Acquired resistance to subsequent EGFR-TKI treatment lines in EGFR-mutant lung cancer patients may induce genetic plasticity. We assess the biological insights of tumor heterogeneity in an osimertinib-resistant tumor with acquired MET-amplification and propose new treatment strategies in this situation.

Keywords: NSCLC, EGFR, T790M, MET, acquired resistance, intratumor plasticity

Introduction

Compared with standard first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, first- and second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) blocking epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling have improved outcomes for lung cancer patients with activating mutations in the EGFR gene [1–3]. However, acquired resistance through a second-site mutation at position 790 (T790M) in the EGFR kinase domain limits the potential of these therapies [4]. Third-generation T790M inhibitors such as osimertinib [5], rociletinib [6], olmutinib [7], and nazartinib [8] are covalent mutant-selective EGFR-TKIs targeting sensitizing mutations in the presence of the T790M. Although these drugs are showing clinical benefit for lung cancer patients [9, 10], resistance occurs and the lack of further treatment options currently represents a major challenge in the field.

Recent data suggest several tertiary mutations in EGFR, such as C797S, L798I and L718Q as mechanisms of resistance to third-generation TKIs targeting EGFR T790M [11–13]. Finally, osimertinib resistance is being linked to either ERBB2 copy number gain, MET gene amplification, NRAS E63K or KRAS G12S mutations [14–16].

Methods

Here, present the case of a patient with a metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. For the described study, we obtained tumor sample from lung tumor and brain metastasis. This metastasis was also used for the patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) development by injecting cells in mouse brain. All samples from both patient and PDOX, preserved as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), were initially genotyped by Amplicon-seq and the orthotopically grown metastases from the PDOX were used for the single-cell analysis. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) study was carried out using all the available samples from patient and PDOX. In addition, for the ddPCR study, samples from 20 patients diagnosed with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at different stages of their treatment were selected. Full description in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Results

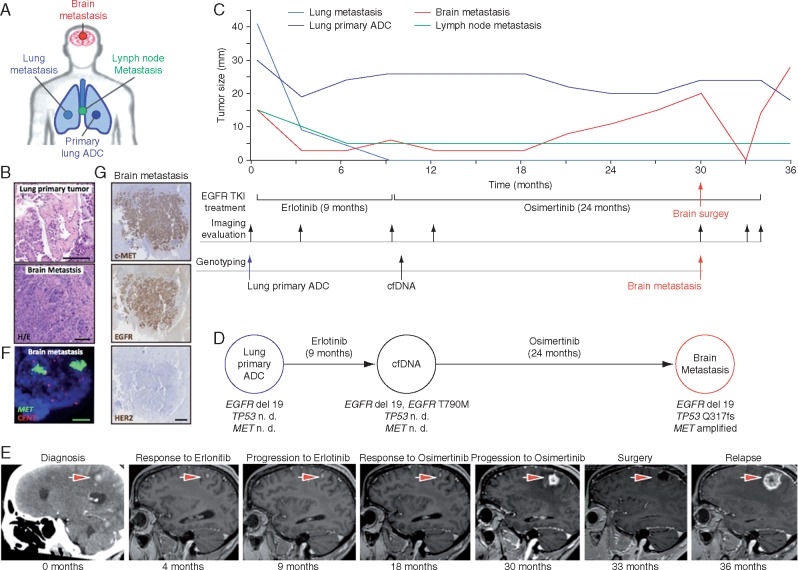

To identify new mechanisms of resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs and define novel treatment strategies, we analyzed the molecular evolution of tumor samples from an EGFR-mutant lung cancer patient treated with consecutive lines of EGFR-TKIs (Figure 1A–C). All available samples were analyzed using targeted re-sequencing detecting mutations in a panel of 57 oncogenes and tumor suppressors [11] (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) or copy number alterations using an nCounter panel. At diagnosis, the patient presented an advanced lung adenocarcinoma with mediastinal lymph nodes, lung and brain metastases initially treated with whole brain radiotherapy (Figure 1C). Since the primary lung adenocarcinoma sample harbored exon 19 deletion in EGFR, the patient was treated with erlotinib (Figure 1D). All lesions initially responded to EGFR blockade until bone metastasis appeared after 9 months of erlotinib treatment (Figure 1C and E). At that time, the patient was included in a phase I clinical trial (AURA trial), receiving treatment with osimertinib. The analysis of cfDNA detected an additional EGFR T790M mutation (Figure 1C and D). Therapy initially reduced brain metastasis and treatment with osimertinib was sustained 21 months until the progressive metastatic brain lesion enlarged and required surgical resection (Figure 1C and E). Following brain surgery, osimertinib was continued for and additional 3 months due to clinical benefit. NGS analyses on this surgical specimen once again showed the deletion of exon 19 in EGFR and the TP53 Q317fs mutation and loss of EGFR T790M mutation (Figure 1D). Additionally, we identified a high-level amplification of the MET oncogene that was confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization [17] (FISH) (copy number of >40; MET/CEN7 ratio of >5) (Figure 1D and F), and high levels of c-MET protein by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1G). HER2 amplification was excluded as a resistance mechanism since no amplification was detected by FISH (ERBB2 gene copy number of 6; ERBB2/CEN17 [18] ratio of 1.1), or by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1F and data not shown). The emergence of this MET amplification in the context of an exon 19 deletion of EGFR and a regression of EGFR T790M mutation led us to combine EGFR and c-MET inhibitors to block the growth of the progressive brain metastasis [19]. Unfortunately, the patient suffered a rapid relapse and died soon after brain surgery.

Figure 1.

Evolution and plasticity of acquired resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in NSCLC harboring EGFR mutation. (A) Study of the molecular profiling of metastatic brain biopsy specimen of female patient with NSCLC exon 19 deletion and T790M mutation treated with osimertinib. (A, C and D) ADC, adenocarcinoma. (B) Morphological appearance of primary and metastatic lung lesions (haematoxylin and eosin, 20×). (C) Serial of target tumor lesions measures and the lower panel displays anti-EGFR treatment, imaging evaluation and genotyping along the evolution of the metastatic disease. (D) Molecular profiling of paired biopsies: baseline and at the time of progression to erlotinib and osimertinib. n. d., non-determined. (E) Representative brain MRI and CT scans at the time points indicated are provided; the largest brain target lesion is indicated with an arrow. (F) FISH analyses showing the presence of MET amplification in the brain metastasis after relapse osimertinib (MET gene, green signals; CEN7, red signals; 100×). (G) High expression of cMET and EGFR proteins was observed in brain lesion by immunohistochemistry. No expression for HER2 was found (2.5×).

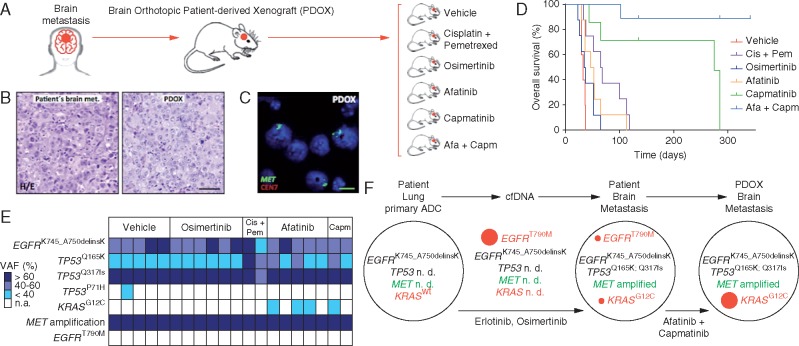

At the time of surgery of brain metastasis, we obtained surgical tumor tissue to implant orthotopically in immunodeficient nude mice, generating an orthoxenograft or PDOX model (Figure 2A) [20, 21]. PDOXs present high concordance with the original clinical tumors [22, 23]. In this particular case, PDOX not only faithfully recapitulated the patient’s histology but also preserved MET amplification (Figure 2B and C) and similar EGFR status (total proteins by IHC and CNV using FISH) (supplementary Figure S3 and Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). This model allowed us to explore the efficacy of an EGFR inhibitor and c-MET inhibitor combined.

Figure 2.

Orthotopic patient-derived xenograft (PDOX) models using the same fresh metastatic brain biopsy of our patient at the time of progression to osimertinib. (A) Different PDOX cohorts that received treatment with vehicle, osimertinib, cisplatin/pemetrexed, afatinib, capmatinib and a combination of capmatinib and afatinib (capmatinib/afatinib). (A, B and E) Cis, cisplatin; Pem, pemetrexed; Cap, capmatinib; Afa, afatinib. (B) Representative images showing high similarity between patient brain metastasis and its PDX (20×). (C) MET gene amplification by FISH in the PDX (MET gene, green signals; CEN7, red signals; 100×). (D) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the different PDOX treated cohorts. (E) Genotyping of PDOX samples obtained from mice that progressed to the different treatments. VAF, variant allele frequency. (F) Representation of clonal evolution of the acquired resistance. KRAS G12C and EGFR T790M mutations were only detected by ddPCR in patient lesions. n. d., non-determined; ADC, adenocarcinoma.

Passable biopsies were orthotopically implanted into the brain of 35 nude mice that were randomized and treated with vehicle, cisplatin/pemetrexed (standard chemotherapy), osimertinib (EGFR sensitizing and T790M resistance mutation inhibitor), afatinib (ErbB-1/2/4 inhibitor), capmatinib (c-MET inhibitor) and a combination of capmatinib and afatinib (Figure 2A). All treatments were administered during 21 days. Capmatinib alone or combined with afatinib showed superior efficacy, significantly increasing the overall survival of mice (Figure 2D). Strikingly, none of the capmatinib/afatinib treated mice displayed weight loss, increased intracranial pressure, presented any tumor evidence, or scaring in the brain or any other analyzed tissues after 300 days upon tumor implantation. These data demonstrate that capmatinib/afatinib treatment cured all mice. In the case of capmatinib monotherapy, two mice died 2 months after tumor implantation presenting brain tumors upon necropsy. Another two mice died after 9 months with no brain tumor, but one presented a lung metastasis and the other a mesenteric lesion. When treated with afatinib alone, all mice progressed with growing brain tumors and had to be killed earlier after treatment initiation. Similarly, PDOX treated with osimertinib did not show any benefit, confirming the resistance observed in the patient. In summary, c-MET, as opposed to EGFR blockade, was effective. The combination of the two, however, was the most potent therapy showing curative potential.

We then genotyped PDOX samples obtained from mice that progressed to the different treatments (Figure 2G). All xenograft tissues showed the same exon 19 deletion in EGFR, TP53 Q317fs mutation as well as MET amplification detected in the original patient’s brain metastasis (Figure 2C, E and F). In addition, we observed a subclonal TP53 Q165K mutation in some xenografts. Interestingly, we detected the emergence of a subclonal KRAS G12C mutation exclusively in xenograft tumors from mice treated with afatinib or capmatinib as monotherapy. This data suggested the surfacing of minor preexisting KRAS G12C mutant clones as a mechanism of resistance to effective EGFR or c-MET signaling blockade. In the original patient’s metastatic brain tumor biopsy, we actually confirmed the existence of EGFR T790M and KRAS G12C mutations at low-allele frequencies using ddPCR [24].

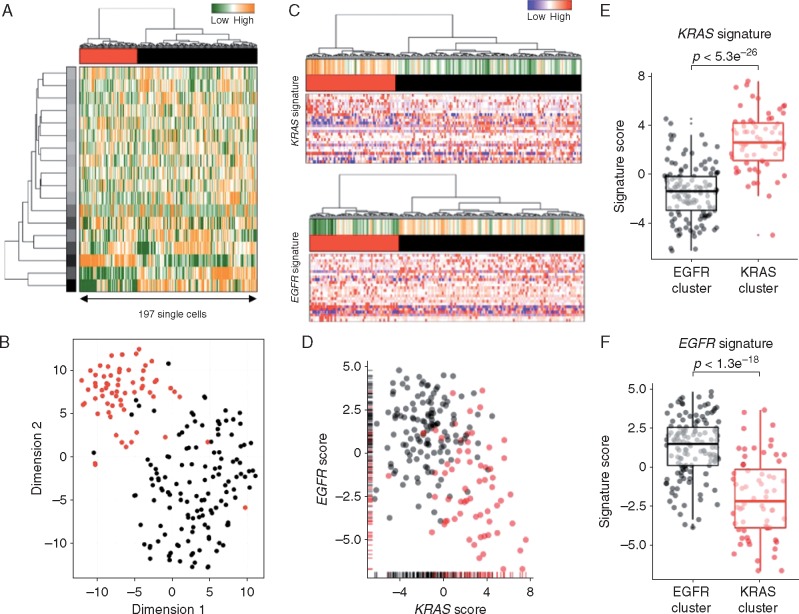

To study this phenomenon further, we evaluated clonal distribution within xenograft tumor samples by single-cell transcriptome analysis (massive parallel single-cell RNA-sequencing, MARS-Seq) [25, 26]. We sequenced 197 randomly selected cells from a tumor xenograft that grew in the brain of a capmatinib treated mouse and presented a KRAS G12C mutation and an exon 19 deletion in EGFR (Figure 2D and E). Using hierarchical clustering, or dimensional reduction representations (tSNE), we grouped single cells based on their differential transcriptional profiles and identified two main subpopulations (Figure 3A and B). We hypothesized that these two subpopulations may represent tumor subclones driven by either KRAS or EGFR activating mutations. To test this hypothesis, we first defined EGFR and KRAS distinctive transcriptional signatures by comparing primary lung adenocarcinoma specimens’ mutant for EGFR or KRAS [27] (supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Remarkably, KRAS-activated genes were upregulated in the less abundant subclone, while EGFR-related genes were activated in the remaining tumor cells (Figure 3C and D). Indeed, we observed a significantly increased expression of the KRAS- or EGFR-signature genes in the minor and major subpopulation, respectively, supporting their distinct activities in the putative tumor subclones (Student’s t-test, Figure 3E and F). The putative EGFR-driven subclone showed a significant association to genes whose expression was altered following targeted EGFR inhibition in vitro (supplementary Figure S1A–D, available at Annals of Oncology online), further supporting a clonal separation of the oncogenes. Collectively, these results support the existence of two distinct tumor subclones driven by either KRAS or EGFR activating mutations. Surprisingly, we further noticed the increased expression of immune system related genes in the KRAS-driven subclone (supplementary Figure S1E and F, available at Annals of Oncology online). We analyzed the PD-L1 expression by IHC in patient brain metastasis, PDOX KRAS WT and PDOX KRAS Mut (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 3.

Single-cell transcriptome profiles point to the presence of a KRAS-driven subclone. (A) Hierarchical clustering of 197 single cells (columns) derived from a capmatinib-resistant PDOX using the most variable gene sets [32]. Cells are grouped into two putative subclones (column labels) and correlating gene sets are summarized in aspects. Displayed are the most variable aspects (rows) and their importance (row colors). (B) Gene expression variances between cells displayed as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) representation using previous defined distances and cluster identities (as in A). (C) Gene expression signatures derived from KRAS (upper panel) or EGFR (lower panel) mutant primary lung adenocarcinomas [27]. Gene expression levels of single cells are displayed as relative intensities [22]. Displayed are the 25 most variant genes and signatures are summarized in the panel above (orange: overrepresented; green: underrepresented). (D) Mutational signature intensities of single cells. Cells are separated by their signature expression levels for EGFR and KRAS mutations. Cells were assigned to clusters as in (A). Direct comparison of KRAS (E) or EGFR (F) signature scores between the putative subclones (KRAS: red; EGFR: black). Significant differences between groups (Student’s t-test) are indicated.

The presence of minor KRAS mutant clones could be a clinically relevant mechanism of resistance to EGFR-TKIs and/or c-MET inhibitors and remain undetectable by standard techniques (NGS, qPCR, Sanger sequencing). Consequently, we used the most sensitive genetic assay, ddPCR [23] for a retrospectively genetic profiling of EGFR-mutated lung cancer patient samples (Table 1). In the biopsies at the time of progression to EGFR-TKIs from 13 EGFR-mutated patients, we detected five EGFR T790M and three KRAS G12C mutant tumors. These patients were originally considered wild type for these alterations when evaluated with NGS (Table 1). Furthermore, none of the seven tumor samples evaluated from surgical early-stage NSCLC patients with the presence of mutation in EGFR and naïve to EGFR-TKIs presented KRAS G12C mutations. In one of the samples, we detected EGFR T790M.

Table 1.

Twenty EGFR-mutated lung cancer samples were assessed retrospectively by a ddPCR assay

| Patient sample | Gender | Smoking habit | Previous lines of treatment | Previous lines of TKI | TKI | Activating EGFR mutation | Baseline EGFR T790M (ddPCR) | Baseline KRAS G12C (ddPCR) | Progression to TKI EGFR T790M (ddPCR) | Progression to TKI KRAS G12C (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Former | 2 | 2 | Gefitinib Nazartinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | 13.35% | 0.0027% |

| 2 | Female | Former | 2 | 1 | Erlotinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | 1.60% | 0.14% |

| 3 | Female | Never | 3 | 2 | Erlotinib Osimertinib | p.L858R | N/A | N/A | N/A | WT |

| 4 | Male | Former | 4 | 1 | Erlotinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | WT | WT |

| 5 | Female | Never | 4 | 2 | Erlotinib Nazartinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | 76.30% | WT |

| 6 | Male | Former | 4 | 2 | Afatinib Nazartinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | 12.20% | WT |

| 7 | Female | Former | 3 | 2 | Afatinib Gefitinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | WT | WT |

| 8 | Female | Never | 1 | 1 | Erlotinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | WT | WT |

| 9 | Female | Never | 3 | 2 | Erlotinib Gefitinib | p.L858R | N/A | N/A | WT | 0.75% |

| 10 | Female | Never | 7 | 2 | Erlotinib Gefitinib | p.L858R | N/A | N/A | WT | WT |

| 11 | Female | Never | 4 | 3 | Dacomitinib Nazartinib Osimertinib | p.L858R | N/A | N/A | 95.75% | WT |

| 12 | Female | Never | 4 | 3 | Erlotinib Rociletinib Osimertinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | WT | WT |

| 13 | Female | Former | 7 | 3 | Gefitinib Erlotinib Osimertinib | ex19del | N/A | N/A | N/A | WT |

| 14 | Female | Never | Naive | 0 | Naive | ex19del | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Male | Never | Naive | 0 | Naive | p.L858R | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | Female | Former | Naive | 0 | Naive | ex19del | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | Female | Never | Naive | 0 | Naive | p.L858R | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 18 | Male | Former | Naive | 0 | Naive | Del p.V769 | 0.33% | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 19 | Female | Never | Naive | 0 | Naive | p.L858R | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

| 20 | Female | Never | Naive | 0 | Naive | ex19del | WT | WT | N/A | N/A |

Thirteen tumor samples from EGFR-mutated patients at the time of progression to EGFR-TKIs were analyzed. Seven biopsies were evaluated from surgical early-stage NSCLC patients with the presence of EGFR mutation and naïve for EGFR-TKI therapy.

Discussion

In summary, we observed how a lung adenocarcinoma presenting an activating deletion of exon 19 in the EGFR gene acquired a second T790M mutation in the same gene upon treatment with erlotinib, while MET amplification was detected after subsequent osimertinib. In the same line, previous studies showed how MET copy number gain causes gefitinib resistance in CNS lesions utilizing mouse in vivo imaging models [28]. At this point, we also detected KRAS G12C and EGFR T790M by ddPCR. Importantly, in a PDOX model, we demonstrated that this MET amplification is essential for lung cancer cell survival since capmatinib therapy proved very effective. Intriguingly, for the very first time, we show c-MET signaling inhibition with capmatinib to be more potent when combined with afatinib than as a single agent in our mouse model. This afatinib effect contrasted with its complete lack of activity as monotherapy. This benefit of combining afatinib could have been mediated by its previously described capacity to block ERBB3 or ERBB4 activations by heregulin ligand in EGFR mutant lung tumors [29]. This inhibition of ERBB3/4 or the inhibition of EGFR itself, are both possible mechanism that require further investigation. Our data suggest that this oncogenic ERBB activation would only be relevant for the survival of cancer cells addicted to hyperactive c-MET signaling. In this sense, c-MET and EGFR (ERBB1) form membrane heterodimers in normal and cancer cells leading to their trans-phosphorylation and activation of downstream MAPK pathway. Additionally, c-MET/KRAS/ERK signaling induces the transcription of EGF ligand and EGFR activation as a positive feedback loop. Further analyses will be required to confirm the relevance of such crosstalk between EGFR or ERBB3/4 with c-MET as a molecular determinant of response to combined c-MET and EGFR blockade in advanced lung cancer.

Our results also evidence the extreme plasticity of lung adenocarcinoma genomes that evolve to adapt to as well as survive the pharmacological pressure of third-generation EGFR-TKIs. Could this be a consequence of selecting de novo mutations in lung cancer genomes or is it reflective of the early coexistence of multiple genetic clones with distinctive capacities to resist target-directed therapies? Our findings support the hypothesis of lung adenocarcinomas consisting of a complex map of genetic clones ready for selection under effective pharmacological pressure. We clearly observed the emergence of KRAS G12C mutant clones upon blocking two upstream activating components of the MAPK pathway such as EGFR or c-MET. Similarly, oncogenic KRAS mutations were described as resistance mechanisms to anti-EGFR antibodies in colorectal cancer [30, 31], a phenomenon that can also involve clonal enrichment upon treatment.

Indeed, we observed that drugs blocking EGFR or c-MET signaling preferentially promoted the emergence of genetic alterations in EGFR, MET and KRAS genes; all essential components of the oncogenic TKR/KRAS/MAPK pathway. This particular genetic evolution confirms the strict addiction of lung tumors to TKR/KRAS/MAPK pathway as a driving force of drug-resistance and disease progression. Consistent with our aforementioned observations, subsequent therapy should be assessed as a combination of the EGFR inhibitor with c-MET inhibitors.

In these highly heterogeneous lung tumor samples, we also noted a subpopulation of cells presenting a distinctive KRAS gene expression signature enriched in immune-related components. Indeed, initial clinical data indicate that KRAS mutant lung adenocarcinomas could be more sensitive to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thus, we also suggest immunotherapy as a later line of treatment of those patients with EGFR mutant lung tumors that progress to consecutive lines of EGFR-TKIs and present emergence of KRAS mutant as well as potentially immunosensitive clones.

Finally, our data indicated that lung adenocarcinomas might evolve rapidly due to the surfacing of minor pre-existing genetic clones resistant to specific targeted therapies. Therefore, more complex therapies combining EGFR-TKIs with MET inhibitors and/or immunotherapy could be considered for lung cancer patients at earlier stages. This novel approach could prevent drug resistance and disease progression later on. For this reason, the clinical implementation of genetic technologies with higher sensitivity will be crucial in defining the genetic landscape of polyclonal tumors in patients’ candidate to target-directed therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the Cellex Foundation for providing facilities and equipment, and Ayudas Merck Serono de Investigación 2016 for its support. We would like to thank to Amanda Wren for excellent technical assistance in writing the manuscript. We thank to Jose Jimenez and Irene Sansano for technical assistance with FFPE and immunohistochemistry.

Funding

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministries of Health and Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria-Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (PI14/01248, PI13-01339, PIE13/00022, PI16/01898); AECC Scientific Foundation (GCB14-2170); and Fundación Mutua Madrileña (AP150932014). HGP and HH are Miguel Servet researchers funded by the Spanish Institute of Health Carlos III (CPII14/00037, CP14/00229). PN laboratory is funded by the Tumor Biomarker Research Program of the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Foundation (FBBVA) (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

All authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K. et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2380–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R. et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N. et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3327–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D. et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 75ra26.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S. et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov 2014; 4: 1046–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walter AO, Sjin RT, Haringsma HJ. et al. Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that overcomes T790M mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov 2013; 3: 1404–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park K, Han JY, Kim DW. et al. 190TiP: ELUXA 1: phase II study of BI 1482694 (HM61713) in patients (pts) with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after treatment with an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR TKI). J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11(4 Suppl): S139. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jia Y, Juarez J, Li J. et al. EGF816 exerts anticancer effects in non-small cell lung cancer by irreversibly and selectively targeting primary and acquired activating mutations in the EGF receptor. Cancer Res 2016; 76(6): 1591–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jänne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW. et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1689–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sequist LV, Soria JC, Camidge DR.. Update to rociletinib data with the RECIST confirmed response rate. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 2296–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thress K, Paweletz CP, Felip E. et al. Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med 2015; 21: 560–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chabon JJ, Simmons AD, Lovejoy AF. et al. Circulating tumor DNA profiling reveals heterogeneity of EGFR inhibitor resistance mechanisms in lung cancer patients. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 11815.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bersanelli M, Minari R, Bordi P. et al. L718Q mutation as new mechanism of acquired resistance to AZD9291 in EGFR-mutated NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2016; 11(10): e121–e123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Planchard D, Loriot Y, André F. et al. EGFR-independent mechanisms of acquired resistance to AZD9291 in EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC patients. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 2073–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eberlein CA, Stetson D, Markovets AA. et al. Acquired resistance to the mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor AZD9291 is associated with increased dependence on RAS signaling in preclinical models. Cancer Res 2015; 12: 2489–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ortiz-Cuaran S, Scheffler M, Plenker D. et al. Heterogeneous mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance to third-generation EGFR inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(19): 4837–4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schildhaus HU, Schultheis AM, Rüschoff J. et al. MET amplification status in therapy-naïve adeno- and squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21(4): 907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rüschoff J, Hanna W, Bilous M. et al. HER2 testing in gastric cancer: a practical approach. Mod Pathol 2012; 25: 637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheffler M, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Bos M. et al. Spatial tumor heterogeneity in lung cancer with acquired epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance: targeting high-level MET-amplification and EGFR T790M mutation occurring at different sites in the same patient. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10(6): e40–e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. John T, Kohler D, Pintilie M. et al. The ability to form primary tumor xenografts is predictive of increased risk of disease recurrence in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fiebig HH, Maier A, Burger AM.. Clonogenic assay with established human tumor xenografts: correlation of in vitro to in vivo activity as a basis for anticancer drug discovery. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40: 802–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffman RM. Patient-derived orthotopic xenografts: better mimic of metastasis than subcutaneous xenografts. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15: 451–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fichtner I, Rolff J, Soong R. et al. Establishment of patient-derived non-small cell lung cancer xenografts as models for the identification of predictive biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 6456–6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA. et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem 2011; 83: 8604–8610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H. et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science 2014; 343: 776–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paul F, Arkin Y, Giladi A. et al. Transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment in myeloid progenitors. Cell 2015; 163: 1663–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 511: 543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nanjo S, Arai S, Wang W. et al. MET copy number gain is associated with gefitinib resistance in leptomeningeal carcinomatosis of EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2017; 16(3): 506–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yonesaka K, Kudo K, Nishida S. et al. The pan-HER family tyrosine kinase inhibitor afatinib overcomes HER3 ligand heregulin-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 33602–33611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S. et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature 2012; 486: 532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diaz LA Jr, Williams RT, Kinde I. et al. The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR blockade in colorectal cancers. Nature 2012; 486: 537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan J, Salathia N, Liu R. et al. Characterizing transcriptional heterogeneity through pathway and gene set overdispersion analysis. Nat Methods 2016; 13: 241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.