Abstract

Background

The availability and affordability of safe, effective, high-quality, affordable anticancer therapies are a core requirement for effective national cancer control plans.

Method

Online survey based on a previously validated approach. The aims of the study were to evaluate (i) the availability on national formulary of licensed antineoplastic medicines across the globe, (ii) patient out-of-pocket costs for the medications, (iii) the actual availability of the medication for a patient with a valid prescription, (iv) information relating to possible factors adversely impacting the availability of antineoplastic agents and (v) the impact of the country’s level of economic development on these parameters. A total of 304 field reporters from 97 countries were invited to participate. The preliminary set of data was posted on the ESMO website for open peer review and amendments have been incorporated into the final report.

Results

Surveys were submitted by 135 reporters from 63 countries and additional peer-review data were submitted by 54 reporters from 19 countries. There are substantial differences in the formulary availability, out-of-pocket costs and actual availability for many anticancer medicines. The most substantial issues are in lower-middle- and low-income countries. Even among medications on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) the discrepancies are profound and these relate to high out-of-pocket costs (in low-middle-income countries 32.0% of EML medicines are available only at full cost and 5.2% are not available at all, and for low-income countries, the corresponding figures are even worse at 57.7% and 8.3%, respectively).

Conclusions

There is wide global variation in formulary availability, out-of-pocket expenditures and actual availability for most licensed anticancer medicines. Low- and low-middle-income countries have significant lack of availability and high out-of-pocket expenditures for cancer medicines on the WHO EML, with much less availability of new, more expensive targeted agents compared with high-income countries.

Keywords: public policy, anticancer medicines, antineoplastic medicines, public health, WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, ESMO

Introduction

The General Assembly of the United Nations, in its 2011 Political Declaration on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases [1], highlighted the primary role and responsibility of governments in improving access and affordability to high-quality medicines. Indeed, in a controversial step, it has even encouraged the full use of trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS) flexibilities, including compulsory licensing, to achieve this end if necessary. Furthermore, in its Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013 to 2020, the World Health Assembly [2] has set a target of an 80% availability of affordable basic technologies and essential medicines required to treat major non-communicable diseases including cancer. Within cancer care and national cancer control planning, medicines play an essential core role, along with surgery and radiotherapy, in both cure and palliation. Endorsed and promoted by ESMO and the Union for International Cancer Control among others, this approach was emphasised in the very recent 70th World Health Assembly resolution on cancer prevention and control [3].

The World Health Organisation defines essential medicines as those that ‘satisfy the priority health care needs of the population which they are intended to be available in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information, and at a price the individual and community can afford’ [4, 5]. In 2015, the WHO made the largest update of its Model List of Essential Medicines for cancer since its inception in 1977 [5].

The European Society for Medical Oncology’s 2020 vision statement recognises that progress in the management of cancer care can and will only occur when high-quality care is both available and affordable to everyone everywhere [6]. This concern underscores the impetus for the previous ESMO study to evaluate the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of anticancer medications in Europe [7], which highlighted dramatic disparities of access particularly to new and expensive anticancer medications between the wealthier countries of Western Europe and the developing economies of Eastern Europe. Similar concerns also drove the development of the ESMO-led Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) studies evaluating the availability out-of-pocket costs and regulatory barriers impeding access of cancer patients to opioid medications for the relief of moderate and severe cancer pain [8–13]. Building on these validated approaches to public policy surveys, this study extends geographic coverage to further inform about the current state of global oncology regarding the availability and affordability of cancer medicines.

The primary aims of the study were to evaluate (i) the formulary availability of licensed antineoplastic medicines in the countries of the world outside of Europe, (ii) patient out-of-pocket costs for the medications, (iii) the actual availability of the medication for a patient with a valid prescription, (iv) information relating to possible factors adversely impacting the availability of antineoplastic agents and (v) the impact of the country’s level of economic development on these parameters.

Methods

Project development

The study was developed by the ESMO Global Policy Committee, with input and cooperation of the ESMO Executive Board, ESMO National Representatives and other ESMO committees, including those covering EU Policy, Education, Practising Oncologists, as well as the ESMO Faculty and three collaborating partners: the Union for International Cancer Control, the Institute of Cancer Policy of King’s College London and the European Society of Oncology Pharmacy (ESOP). Implementation and data analysis was carried out by independent researchers from the collaborating partner organisations. The World Health Organization (WHO) was a supporting partner in this project as part of an ongoing 3-year work plan between WHO and ESMO, who enjoys ‘official relations status’ with WHO.

Study format and data collection

The questionnaire-based survey tool was modelled on the previous ESMO study of the availability and accessibility of anticancer medicines in Europe [7].

The survey consisted of three parts: part 1 consisted of six general questions regarding the country’s healthcare system; part 2 surveyed the formulary of generic anticancer medication commonly used over a wide range of cancers, and part 3 surveyed the formulary of generic anticancer medication used in seven high-incidence cancers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diseases surveyed

|

The list of anticancer medications for each disease entity was derived from ESMO and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as well as ‘UpToDate’ subject reviews, where medicines approved by either the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as of March 2015 were included. The list was edited for relevance by the ESMO Global Policy Committee.

Field reporters were asked to indicate the following for each medication: whether it was permissible to prescribe the cancer medicine for the stated indication; if the medication costs are reimbursed for this indication; the average proportion of the full retail price patients are obliged to pay out-of-pocket for the medication; the actual availability of the medication for most patients in the country when prescribed and in cases where the medication is not always available, the dominant reason for lack of availability.

ESMO and the collaborating partners sought to identify a minimum of two field reporters, either oncologists or oncology pharmacists, through an iterative process for each country. The field reporters were derived from either national or approved representatives of the professional organisations collaborating in this project. A total of 304 field reporters from 97 countries were invited to participate. Repeat requests for data submission were sent to non-responding invitees to minimise the number of countries where data was not verifiable between two or more reporters.

Electronic survey forms were developed on a Qualtrics survey software platform which facilitated automatic data entry into an Excel spread sheet for analysis. Data submitted between 30 April and 18 December 2015 by the two field reporters from each country were cross-checked by the principle investigator (Nathan Cherny). When discrepancies between reporters were identified, clarifications were requested. When discrepancies persisted, priority was given to the response provided by the most highly credentialed reporter and where supportive data were presented. The principle investigator tabulated and graphically presented the data in the format used in the previous ESMO survey for Europe [7].

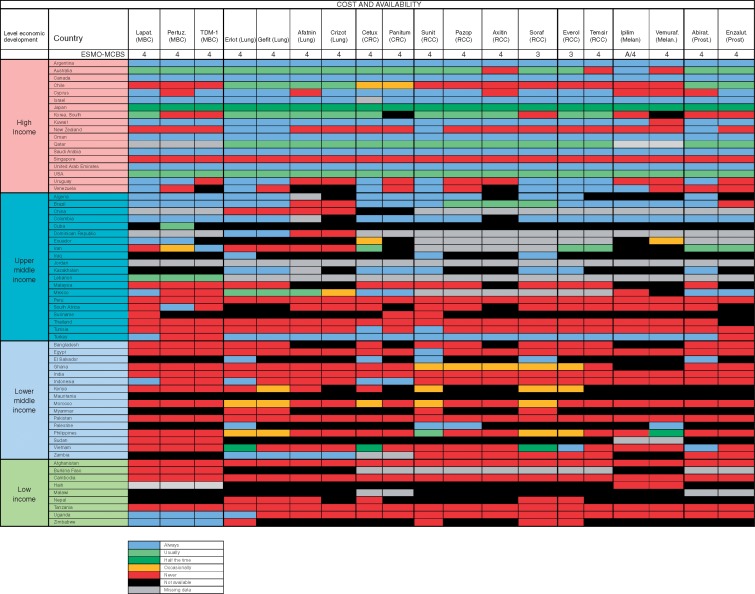

Data regarding medications with relatively recent marketing approval and not included in the 2015 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, were cross-referenced with scores derived from the ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS) using the revised version 1.1 of the scale [14].

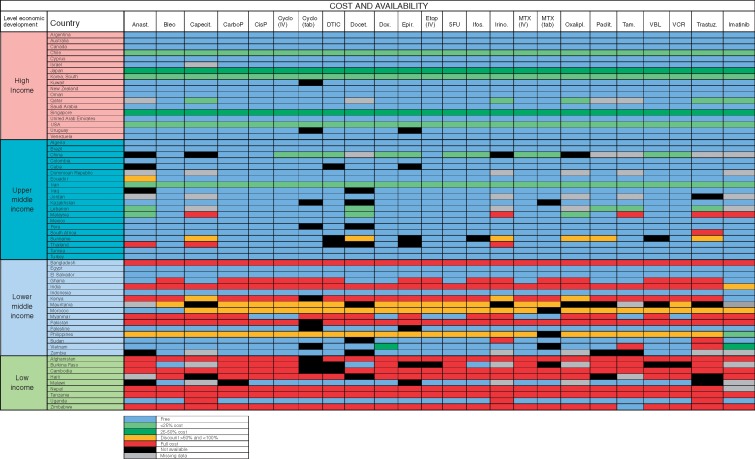

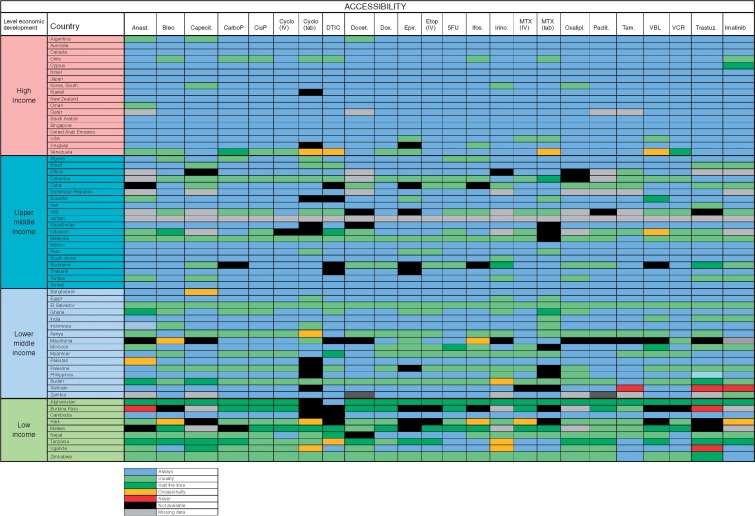

The results pertaining to study aims 1 and 2 are presented in figures labelled ‘Formulary availability and out-of-pocket cost’. These colour-coded figures indicate (in black) medications that are not on formulary (aim 1), and for medicines on formulary (other colours), indicate the percentage of the full price that patients pay out-of-pocket after state or insurance reimbursement (aim 2). The results pertaining to aim 3, actual availability of the medication for a patient with a valid prescription are presented in figures labelled ‘Actual availability’. These colour-coded figures indicate (in black) medications that are not on formulary, and for medicines on formulary (other colours), indicate the percentage of instances in which a patient with a valid prescription can actually access the prescribed medication.

The preliminary data were posted on the ESMO website for external validation between 16 March and 31 May 2016. Invitations were sent to all members of the coordinating and collaborating partner organisations to review the data and to submit any corrections or amendments. Amendments and corrections were collated, cross-checked and incorporated into the final report.

The country data are stratified according to the level of each country’s economic development based on World Bank Criteria (http://data.worldbank.org/country) classifying them as high income (high), upper middle income, lower middle income and low-income (low) and are presented alphabetically. For clarity of presentation, and to highlight findings of inequity and impact, this report focuses on medications included in the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines [5] and recently approved medications with an ESMO-MCBS score >2 (corresponding to moderate to high level of clinical benefit) [14].

Results

Surveys were submitted by 135 individual reporters from 63 countries (Tables 2 and 3). Additional data following peer review were submitted by a further 54 reporters from 19 countries.

Table 2.

Country demographics

| Total countries | Surveyed countries | Percent of countries surveyed in Region | Total Population (bil) | Surveyed population (bil) | Percent of surveyed population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 51 | 11 | 21.5% | 0.795 | 0.262 | 32.9% |

| Asia and India | 29 | 18 | 62.1% | 3.703 | 3.601 | 97.2% |

| North America | 5 | 2 | 40.0% | 0.332 | 0.332 | 100.0% |

| Oceania | 21 | 2 | 9.5% | 0.033 | 0.024 | 72.7% |

| Middle East | 16 | 12 | 75% | 0.195 | 0.153 | 78.4% |

| North Africa | 6 | 4 | 66.7% | 0.161 | 0.155 | 96.2% |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 45 | 14 | 31.1% | 0.562 | 0.502 | 89.3% |

| 173 | 63 | 36.4% | 5.781 | 5.029 | 86.9% |

Table 3.

Number of field reporters for each country

| Number of field reporters | Country |

|---|---|

| >6 | Turkey (N = 1) |

| 6 | Egypt, Oman (N = 2) |

| 5 | Australia, Canada, India, Israel, Japan, Palestine (N = 6) |

| 4 | Argentina, Chile, Cyprus (N = 3) |

| 3 | Brazil, Myanmar, Colombia, Kenya, Korea (South), Peru, Singapore, South Africa, Sudan, Thailand, USA (N = 10) |

| 2 | Iraq, Lebanon, Malaysia, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia (N = 6) |

| 1 | Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ghana, Haiti, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Malawi, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tanzania, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Venezuela, Zimbabwe (N = 28) |

Medications included in the World Health Organization’s 2015 Model List of Essential Medicines

The antineoplastic medicines chapter of the WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines was updated in April 2015 [5] following comprehensive review. The WHO updated the list adding 16 new medicines such as capecitabine (for colorectal and breast cancer), oxaliplatin (for adjuvant and metastatic colorectal cancer), irinotecan (for metastatic colorectal cancer), vinorelbine (for non-small-cell lung cancer and metastatic breast cancer), anastrozole (for adjuvant and metastatic breast cancer) and two very high-cost medications, which at that time were still under patent protection: imatinib (for GIST tumours) and trastuzumab (for adjuvant and metastatic HER2 overexpressed breast cancer).

In high-income and in upper middle-income countries, most of the medicines incorporated into the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines are on formulary and are available to patients at either no cost or on a subsidised basis (Figure 1). Overall in low-middle-income and in low-income countries reports of poor accessibility are greater, and in many countries, patients incur full out-of-pocket cost even for generic anticancer medications that are on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (Table 4). These observations are most pertinent in Bangladesh, Ghana, India, Kenya, Myanmar, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Haiti, Nepal, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

Figure 1.

Medication on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: formulary availability and out-of-pocket costs. Anast, Anastrozole; Bleo, Bleomycin; Capecit, Capecitabine; CarboP, Caboplatinum; CisP, CisPlatinum; Cyclo, Cyclophosphamide; DTIC, Decarbazine; Docet., Docitaxel; Dox, doxorubicin; Epir, Epirubicin; Etop, Etoposide; Ifos, Ifosfamide; Irino, Irinotecan; MTX, methotrexate; Oxalipl, Oxaliplatinum; Paclit, Paclitaxel; Tam, Tamoxifen; VBL, Vinblastine; VCR, Vincristine; Trastuz, Trastuzumab.

Table 4.

Percentages of individual medication reports of non-availability, availability at full price only, and available but not accessible for 24 medicines from the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for cancer stratified by national income level

| Essential medicines (n = 24) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| National Income level (n = number of countries) | Not available (%) | Available only at full price (%) | Available but not accessible (%) |

| High (n = 18) | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Upper middle (n = 20) | 4.1 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| Lower middle (n = 16) | 5.2 | 32.0 | 0.8 |

| Low (n = 9) | 8.3 | 57.7 | 1.3 |

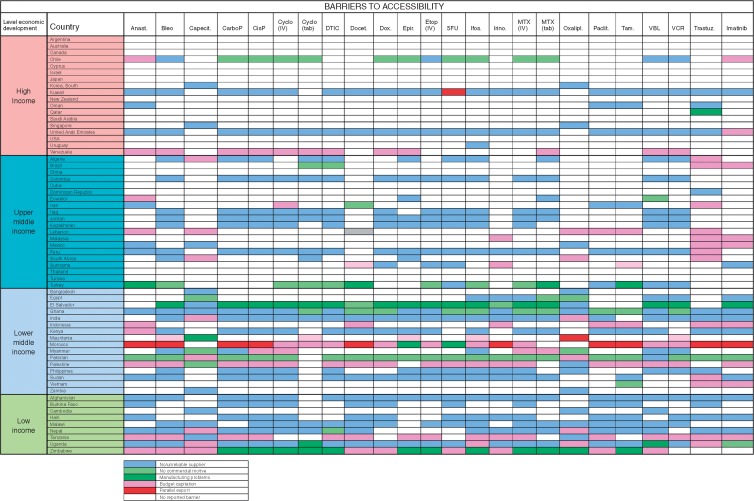

Problems with the accessibility of medicines were reported substantially more prevalent in middle-income and low-income countries (Figure 2): in particular in Colombia, Iraq, Malaysia, Suriname El Salvador, Kenya, Sudan Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Haiti, Malawi, Nepal, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The dominant reported barriers to accessibility were either a lack of or unreliable supplier, or budgetary restraint (Figure 3). Lack of commercial motive and manufacturing problems was less commonly reported.

Figure 2.

Medication on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: Actual availability (accessibility with valid prescription). Anast, Anastrozole; Bleo, Bleomycin; Capecit, Capecitabine; CarboP, Caboplatinum; CisP, CisPlatinum; Cyclo, Cyclophosphamide; DTIC, Decarbazine; Docet., Docitaxel; Dox, doxorubicin; Epir, Epirubicin; Etop, Etoposide; Ifos, Ifosfamide; Irino, Irinotecan; MTX, methotrexate; Oxalipl, Oxaliplatinum; Praclit, Paclitaxel; Tam, Tamoxifen; VBL, Vinblastine; VCR, Vincristine; Trastuz, Trastuzumab.

Figure 3.

Medication on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: Dominant Barrier to Accessibility. Anast, Anestrozole; Bleo, Bleomycin; Capecit, Capecitabine; CarboP, Caboplatinum; CisP, CisPlatinum; Cyclo, Cyclophosphamide; DTIC, Decarbazine; Docet., Docitaxel; Dox, doxorubicin; Epir, Epirubicin; Etop, Etoposide; Ifos, Ifosfamide; Irino, Irinotecan; MTX, methotrexate; Oxalipl, Oxaliplatinum; Paclit, Paclitaxel; Tam, Tamoxifen; VBL, Vinblastine; VCR, Vincristine; Trastuz, Trastuzumab.

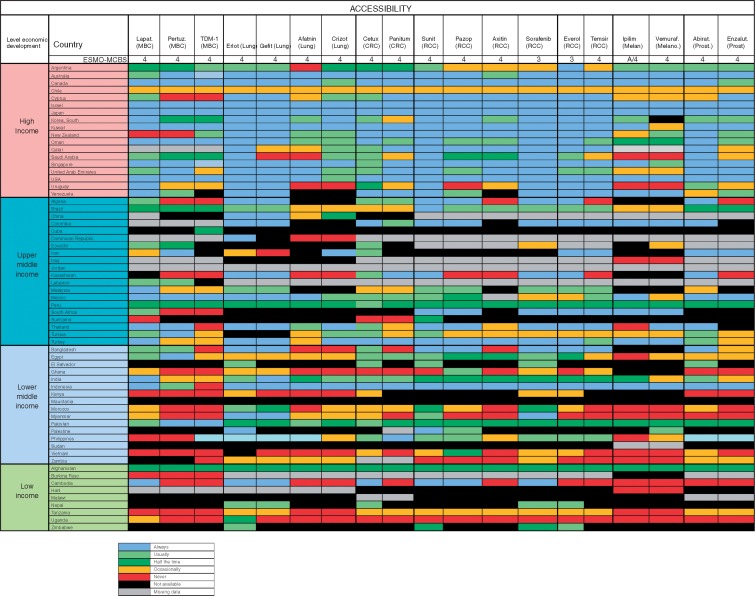

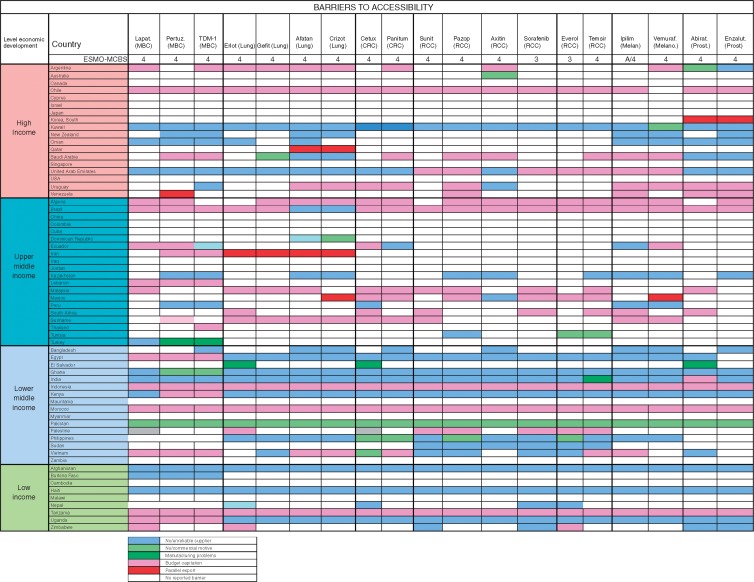

Approved medications not on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, with ESMO-MCBS score >2

At the time we did the survey, 19 medications from 7 disease groups met these criteria; lapatinib, pertuzumab and TDM-1 (breast cancer); erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib (EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer), crizotinib (ALK translocated non-small-cell lung cancer); cetuximab and panitumumab (RAS/RAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer); sunitinib, pazopanib, axitinib, sorafenib, everolimus and temsirolimus (renal cell cancer); ipilimumab and vemurafenib (melanoma) and abiraterone and enzalutamide (prostate cancer).

In most middle- and low-income countries, with few exceptions (Brazil, Colombia and Turkey), these medications not on the WHO EML are very infrequently available at reduced cost to patients and many of them were not available at all. High out-of-pocket costs were less frequent in high-income countries where the medications were almost always on formulary (Figure 4). Overall accessibility of these agents was less than for medications included in the WHO EML, and problems of accessibility were greater in lower-middle and low-income countries (Table 5). Even in high-income countries, limited accessibility was sporadically reported and was most frequently reported in Chile, Cyprus Saudi Arabia, Uruguay and Venezuela (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Recently approved medications not on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, with ESMO-MCBS score >2: Formulary availability and out-of-pocket costs. MBC, Metastatic breast cancer; CRC, Colorectal cancer; RCC, Renal cell cancer; Melan, Melanoma; Prost, Prostate; Lapat, Lapatinib; Pertuz, Pertuzumab; Erlot, Eroltinib; Gefit, Gefitinib; Aftatin, Atafinib; Cetux, Cetuxumab; Panitum, Panitumumab; Suni, Sunitinib; Pazop, Pazopinib; Axitin, Axitinib; Soraf, Sorafinib; Everol, Everolimus; Ipilim, Ipilimumab; Vemuraf, Vermrafenib; Abirat, Abiraterone; Enzalut, Enzalutamide.

Table 5.

Percentages of individual medication reports of non-availability, availability at full price only, and available but not accessible, for 19 recently approved medications not on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, with ESMO-MCBS score >2, stratified by national income level

| New medications with high ESMO-MCBS (n = 19) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| National income level (n = number of countries) | Not available (%) | Available only at full price (%) | Available but not accessible (%) |

| High (n = 18) | 1.0 | 15.0 | 3.0 |

| Upper middle (n = 20) | 27.3 | 34.3 | 7.4 |

| Lower middle (n = 16) | 32.0 | 53.0 | 21.6 |

| Low (n = 9) | 39.4 | 58.5 | 26.3 |

Figure 5.

Recently approved medications not on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, with ESMO-MCBS score >2: Actual availability (accessibility with valid prescription). MBC, Metastatic breast cancer; CRC, Colorectal cancer; RCC, Renal cell cancer; Melan, Melanoma; Prost, Prostate; Lapat, Lapatinib; Pertuz, Pertuzumab; Erlot, Eroltinib; Gefit, Gefitinib; Aftatin, Atafinib; Cetux, Cetuxumab; Panitum, Panitumumab; Suni, Sunitinib; Pazop, Pazopinib; Axitin, Axitinib; Soraf, Sorafinib; Everol, Everolimus; Ipilim, Ipilimumab; Vemuraf, Vermrafenib; Abirat, Abiraterone; Enzalut, Enzalutamide.

The dominant reported barriers to accessibility to cancer medicines were budgetary constraints as well as unreliable supply. The dominant reported barrier in high-income and upper middle-income countries was budgetary constraints, while in lower middle-income and low-income countries, lack of supplier or commercial motivation was increasingly dominant. Parallel export, whereby shortages are caused by the export of relatively inexpensive medications for foreign use, was infrequently reported as a major cause of lack of accessibility; however, it was reported in South Korea, Qatar, Venezuela, Iran and Mexico (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Recently approved medications not on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, with ESMO-MCBS score >2: Dominant Barrier to Accessibility. MBC, Metastatic breast cancer; CRC, Colorectal cancer; RCC, Renal cell cancer; Melan, Melanoma; Prost, Prostate; Lapat, Lapatinib; Pertuz, Pertuzumab; Erlot, Eroltinib; Gefit, Gefitinib; Aftatin, Atafinib; Cetux, Cetuxumab; Panitum, Panitumumab; Suni, Sunitinib; Pazop, Pazopinib; Axitin, Axitinib; Soraf, Sorafinib; Everol, Everolimus; Ipilim, Ipilimumab; Vemuraf, Vermrafenib; Abirat, Abiraterone; Enzalut, Enzalutamide.

Full tabular reports

The full tabular reports for widely used generic medications and for the seven disease-related indications are presented in the supplementary Excel File, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Discussion

The are several major findings of this study. First, and of greatest concern, is the finding that for cancer patients and their families in low-middle- and low-income countries of the world, many anticancer medications recommended on the WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines are available only at full cost as an out-of-pocket expense, and that accessibility is limited because of unreliable supply. Second, many of the recently approved agents in the treatment of metastatic cancers are often unavailable or available only again at great personal expense in countries other than those which are most economically developed. This contributes to profound inequity in access to treatment and care of patients with for example, EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell cancer, melanoma, RAS/RAF wild-type metastatic colon cancer, castrate-resistant prostate cancer and Her-2 amplified metastatic breast cancer.

These findings are consistent with those of the previous International Consortium study evaluating the formulary availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of anticancer medication in Europe, which demonstrated similar patterns of availability and accessibility between the high-income countries of Western Europe compared with the upper middle-income countries of Eastern Europe [7]. Significantly, the European study did not include any low-middle- or low-income countries [7], and it is in these severely economically challenged countries that the greatest discrepancies in access occur.

The discrepancies in access to cancer care and major discrepancies in cancer outcomes between rich and poor countries are well recognised and described [15, 16]. Recent trends suggest that this divide is widening: there is evidence that the prevalence and mortality of cancer in high-income countries are declining, while in poor countries they are increasing [15, 17–19]. The Global Task Force On Expanded Access To Cancer Care And Control [17] reported that only 5% of global resources for cancer care are spent in the developing world despite having almost 80% of disability-adjusted life years lost to cancer globally.

The cancer burden and mortality of the economically disadvantaged countries of the world is disproportionate [15–17, 20] for a range of reasons. Cancer prevention and early detection programs are weak [17–19], there is a high and rising prevalence of tobacco smoking [21], a rising incidence of obesity [22], and low immunisation rates and viral infections such as hepatitis and human papilloma virus account for 20%–30% of cancer deaths [18]. A range of social determinants mean that most patients who present to conventional cancer care (many never make it this far) do so with advanced disease [15, 16, 20]. For those patients who do present with potentially curable disease, the situation is further confounded by poor clinical governance and quality of care, the lack of general financing for healthcare, and low levels of health insurance or social security coverage [23]. The ability to provide care is further impeded by well recognised deficits in pathology [24], radiotherapy [25] and surgery [26] reflecting a systems-wide failure to deliver on or develop comprehensive national cancer control plans. Finally, all of these discrepancies are further exacerbated by the rising cost of both old and new cancer medicines [27].

High out-of-pocket costs for treatments are a key limitation to accessing health services. Even in high-income countries, high co-payments for expensive anticancer medication are a major cause of personal bankruptcy [28–31] and in low-income countries often there is little financial risk protection because costs are largely borne by households themselves rather than by governments or insurance schemes [31–36]. On average, almost 50% of health care financing in low-income countries comes from out-of-pocket payments, as compared with 30% in middle-income countries, and 14% in high-income countries. [23, 31, 35]. For patients and for their families, this is often catastrophic, because care is either unaffordable or, when paid for from personal finances, pushes many into poverty from medical expenses, particularly when this is combined with a loss of income due to ill-health [20, 33, 34, 37].

International public policy initiatives to improve access to affordable medications

There have been many aspirational initiatives to address this issue. The 2011 Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the UN General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases [1] declared that the global burden and threat of non-communicable diseases including cancer is a major concern which undermines social and economic development. It highlighted the primary role and responsibility of Governments in these issues. This UN document repeatedly highlighted the issue of affordability of medical technologies and even endorsed ‘the full use of trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights (TRIPS) flexibilities’. Property Rights (TRIPS) agreements of the World Trade Organization has provisions for compulsory licensing as an option of last resort after attempts to negotiate a voluntary licence on reasonable commercial terms have failed [38–42].

The WHO has emphasised that provision of adequate financial protection from the costs of seeking and using medical care is a critical marker of the effectiveness of a healthcare system [43] and has encouraged its Member States to provide universal health coverage in some form [35] as a means to promote the human right to health [44]. The United Nations passed a declaration that calls for universal access to health care that does not cause financial hardship [45] and has further reiterated the goal of universal health coverage under goal number 3 (good health and well-being) of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals [46]. More recently, the World Health Assembly (WHA), the governing body of the WHO, passed a landmark resolution on Cancer prevention and control [3], representing a big step forward in the awareness and acceptance of the need for immediate action from all UN Member States to take concrete actions on cancer control. While the 2011 UN Political Declaration emphasised prevention, the 2017 Cancer Resolution calls on Member States to ensure a comprehensive approach through national cancer control plans, to assure cancer registries gather complete and accurate data, and most importantly, to provide access to cancer services, including timely access to cancer medicines, vaccines and medical devices, and to optimise their oncology workforce [3].

ESMO has been continuously active in these areas and has contributed to the updates of the WHO EML model list [5], and the 2017 WHO list of priority medical devices for cancer management [47] that highlights, for the most frequent tumour types, the specific medical devices necessary for the delivery of adequate care. To fulfil the call of the 2017 Cancer Resolution, WHO is developing an oncology workforce study in collaboration with ESMO’s Global Policy Committee. The study will include a survey which will match the list of necessary cancer interventions to professional competencies required to deliver them, accompanied by a modelling tool to estimate future workforce requirements [48].

The WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines is a guide for the development of national and institutional essential medicine lists that was developed with the aim of promoting equity in health. The WHO defines essential medicines are those ‘that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population. They are selected with due regard to public health relevance, evidence on efficacy and safety, and comparative cost-effectiveness. Essential medicines are intended to be available within the context of functioning health systems at all times in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information, and at a price the individual and the community can afford’ [4]. One of the voluntary aims of the World Health Assembly Global Action Plan for the Prevention And Control Of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020 includes the aim [2] to achieve an 80% availability of the WHO basic technologies and essential medicines, including generics, required to treat major noncommunicable diseases in both public and private facilities. With regard to anticancer medications, this ESMO study indicates that the international community is still far from achieving this goal. Indeed delivering better outcomes with affordable cancer medicines requires significant cancer systems and health care delivery improvements in many countries in fundamental areas–such as detecting cancer at the earliest possible stage, and the provision of high-quality basic surgical and medical services.

Learning from positive experiences

Among the low-middle-income and low-income countries, some stand out as exceptions in managing to provide essential anticancer medicines at affordable prices as a part of developing broad cancer care systems; examples include Egypt, El Salvador, Indonesia, Malawi, Palestine, Sudan, Uganda, Vietnam and Zambia (Table 1). These data, if sustained by confirmatory studies, suggest that there may be salient models in governance and public health administration to be derived from the experience of these low-middle- and low-income countries that are politically committed to addressing affordable, equitable and safe cancer care, including the provision of cancer medicines.

Disclaimers

The information presented in this survey is a time-constrained ‘snapshot’ of the situation, as was reported during the survey period, and it will be subject to change over time. Consequently this dataset does not incorporate newer immunotherapies that were introduced to the therapeutic repertoire since the study was designed and administered.

The data were derived from practicing clinicians and oncology pharmacists working in the field and not from state authorities or statutory bodies. Reporting physicians were asked to consult with regulatory authorities in circumstances in which they were unsure of cost or a formulary issue. The accuracy of the data is dependent on the reporting accuracy of field reporters and their due diligence in verification of facts. Field reporters were nominated on the basis of recognised involvement in oncology practice and, in many cases, in leadership positions in oncology or in oncology pharmacy in their country.

When submitted responses were incomplete, submitted data were entered and items not addressed were marked as missing data. In the dataset for medicines on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines there were no missing data. In the dataset for new medications with an ESMO-MCBS score >2, missing data rates varied between the national income groups: high income 4%, upper middle income 21%, low middle income 1%, low income 11%.

The methodology used in this study incorporated measures to minimise error, including multiple reporters, cross-checks between reporters, and a process of open peer review. Cross-checking between reporters was not possible in 26 countries where submissions were received by only one reporter, in which case additional verification was only possible in the open peer-review process.

In summary, this study finds that there are disparities in the formulary availability, out-of-pocket costs to patients, and actual availability for many anticancer medicines particularly in middle- and low-income countries of the world. In low-middle-income and low-income countries these discrepancies are profound even for anticancer medicines included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Discrepancies are most severe in incurable diseases where gains in improved patient outcomes are dependent on the availability of expensive anticancer agents for which major differences were seen in availability and in out-of-pocket costs of in all but the very wealthiest countries in the world.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the feedback and input of representatives of the collaborating partner organisations who critically reviewed earlier versions of this manuscript. Acknowledgement also goes to the support and contributions of the ESMO Executive Board, who authorised funding of this project, and the logistic and organisational support provided by ESMO Staff and in particular Gracemarie Bricalli, project manager, and Nicola Latino, survey manager. The authors also thank and acknowledge the wonderful field reporters who completed the survey and peer review. In Appendix, we have listed the field reporters who have agreed to place their names in this publication and we also thank those who wished to remain anonymous.

Funding

ESMO (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

The authors have declared the following: AE: Currently conducting research sponsored by Roche, GSK, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Celltrion and Apotex Inc. NC: received funding from ESMO for project design and development, data analysis and writing the article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

| Name | Country |

|---|---|

| Mohammad Shafiq Faqeerzai | Afghanistan |

| Eduardo Lagomarsino | Argentina |

| Bernardo Leone | Argentina |

| Eduardo Cazap | Argentina |

| Brian Stein | Australia |

| Deme Karikios | Australia |

| Ganes Pranavan | Australia |

| Ian Olver | Australia |

| Shaun O’Connor | Australia |

| Sandro Cavallero | Brazil |

| Elaine Moraes | Brazil |

| Franklin Pimentel | Brazil |

| Evanius Wiermann | Brazil |

| Yobi Alexis Sawadogo | Burkina Faso |

| Turobova Tatiana | Cambodia |

| Carole Chambers | Canada |

| Gerald Batist | Canada |

| Roanne Segal | Canada |

| Sara Aguayo | Chile |

| Bettina Muller | Chile |

| Luis Villanueva | Chile |

| Carlos Castro | Colombia |

| Luis-Rodolfo Gomez-Wolff | Colombia |

| George Astras | Cyprus |

| Sophia Nestoros | Cyprus |

| Enrique Teran | Ecuador |

| Rasha Fahmi | Egypt |

| Waleed Nafae | Egypt |

| Ahmed Elzawawy | Egypt |

| Luis Carias | El Salvador |

| Verna Vanderpuye | Ghana |

| Joseph Junior Bernard | Haiti |

| Navneet Singh | India |

| Gouri Shankar Bhattacharyya | India |

| Wesley Jose | India |

| Aniket Thoke | India |

| Bhawna Sirohi | India |

| Gangadhar Vajrala | India |

| Maryam Rassouli | Iran |

| Mohammad-Reza Ghavam-Nasiri | Iran |

| Manwar Alnaqqash | Iraq |

| Raphael Catane | Israel |

| Yasushi Goto | Japan |

| Shinya Suzuki | Japan |

| Yasuhiro Fujiwara | Japan |

| Atsushi Ohtsu | Japan |

| Dilyara Kaidarova | Kazakhstan |

| David Wata | Kenya |

| Irene Weru | Kenya |

| Seock-Ah Im | Korea |

| Khaled Alsaleh | Kuwait |

| Michel Daher | Lebanon |

| Wilberforce Mhango | Malawi |

| Harbans Dhillon | Malaysia |

| Jean Rene Clemenceau | Mexico |

| Mariana Lopez Lemus | Mexico |

| Paula Cabrera-Galeana | Mexico |

| Hafidi Youssef | Morocco |

| She Mon | Myanmar |

| Soe Aung | Myanmar |

| Khin Chit | Myanmar |

| Rajeeb Deo | Nepal |

| Subhas Pandit | Nepal |

| Robert Matthew Strother | New Zealand |

| Bassim Al Bahrani | Oman |

| Adil Aljarrah Alajmi | Oman |

| Wahid Al Kharusi | Oman |

| Arif Ali | Pakistan |

| Hani Ayyash | Palestine |

| Salah Abushanab | Palestine |

| Khaled Thabet | Palestine |

| Mohammad Najajreh | Palestine |

| Silvia Neciosup | Peru |

| Luis Mas | Peru |

| Dennis Sacdalan | Philippines |

| Jorge Lognaci | Philippines |

| Kakil Rasul | Qatar |

| Ali Al-Shangeeti | Saudi Arabia |

| Medhat Faris | Saudi Arabia |

| Kaung Yuan Lew | Singapore |

| Paul Ruff | South Africa |

| Catharina Van der Merwe | South Africa |

| Ahmed Elhaj | Sudan |

| Dafalla Abuidris | Sudan |

| Nahla Gafer | Sudan |

| Els Dams | Suriname |

| Deogratias Katabalo | Tanzania |

| Twalib Ngoma | Tanzania |

| Virote Sriuranpong | Thailand |

| Thitiya Dejthevaporn | Thailand |

| Charuwan Akewanlop | Thailand |

| Hamouda Boussen | Tunisia |

| Myriam Razgallah Khrouf | Tunisia |

| Mehmet Akif Ozturk | Turkey |

| Vahit Ozmen | Turkey |

| Filiz Çay Şenler | Turkey |

| Ibrahim Turker | Turkey |

| Rejin Kebudi | Turkey |

| Ahmet Özet | Turkey |

| Dilşen Çolak | Turkey |

| Meltem Baykara | Turkey |

| Benjamin Mwesige | Uganda |

| Linda Bosserman | USA |

| Stephen Grubbs | USA |

| Carlos Garbino | Uruguay |

| Maria Aponte-Rueda | Venezuela |

| Sunil Daryanani | Venezuela |

| Kennedy Lishimpi | Zambia |

| Lewis Banda | Zambia |

| Ntokozo Ndlovu | Zimbabwe |

References

- 1. United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. New York: United Nations; 2011; http://www.who.int/nmh/events/un_ncd_summit2011/political_declaration_en.pdf: pp13 (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Assembly S-S. Follow-up to the political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. WHA6610, 2013. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf?ua=12013; pp55 (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 3. Seventieth World Health Assembly. Cancer prevention and control in the context of an integrated approach (A70/32). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017; pp6 http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_32-en.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 2007; 1–162 (back cover). [PubMed]

- 5. World Health Organization. The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines: Report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2015 in WHO Technical Report Series. Geneva: World Health Association 2015; 553.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/189763/189761/9789241209946_eng.pdf?ua=9789241209941 (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 6. European Society for Medical Oncology. ESMO 2020 vision. Lugano: ESMO 2015; pp12 www.esmo.org/content/download/68849/1233986/file/ESMO-1232020-vision-brochure.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 7. Cherny N, Sullivan R, Torode J. et al. ESMO European Consortium Study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in Europe. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 1423–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cleary J, Simha N, Panieri A. et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in India: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): xi33–xi40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cleary J, Silbermann M, Scholten W. et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in the Middle East: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): xi51–xi59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cleary J, Radbruch L, Torode J, Cherny NI.. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Asia: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): xi24–xi32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cleary J, Powell RA, Munene G. et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Africa: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): xi14–xi23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cleary J, De Lima L, Eisenchlas J. et al. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Latin America and the Caribbean: a report from the Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI). Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 11): xi41–xi50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherny NI, Cleary J, Scholten W. et al. The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) project to evaluate the availability and accessibility of opioids for the management of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East: Introduction and Methodology. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: xi7–xi13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cherny N, Dafni U, Bogaerts J. et al. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Version 1.1. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(10): 2340–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H. et al. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25 676 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet 2015; 385: 977–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forman D, Ferlay J.. The global and regional burden of cancer In Stewart B, Wild CP (eds), World Cancer Report 2014. Geneva: International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO; 2014; 16–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knaul FM, Frenk J, Shulman L, for the Global Task Force on Expanded Access to Cancer Care and Control in Developing Countries. Closing the cancer divide: a blueprint to expand access in low and middle income countries. Boston, MA: Harvard Global Equity Initiative; 2011; 286.http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k69586&pageid=icb.page495154 (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A.. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends–an update Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016; 25: 16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hashim D, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C. et al. The global decrease in cancer mortality: trends and disparities. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 926–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bray D, Transitions in human development and the global cancer burden In Stewart B, Wild CP (eds), World Cancer Report 2014. Geneva: International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO; 2014; 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N. et al. The tobacco atlas. American Cancer Society, Atlanta: 2015; 46.http://3pk43x313ggr4cy0lh3tctjh.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/TA5_2015_WEB.pdf (August 2017, date lase accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 22. Popkin BM, Slining MM.. New dynamics in global obesity facing low- and middle-income countries. Obes Rev 2013; 14(Suppl 2): 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mills A. Health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fleming KA, Naidoo M, Wilson M. et al. An essential pathology package for low- and middle-income countries. Am J Clin Pathol 2017; 147: 15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB. et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1153–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan R, Alatise OI, Anderson BO. et al. Global cancer surgery: delivering safe, affordable, and timely cancer surgery. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1193–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prasad V, De Jesús K, Mailankody S.. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017; 14: 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banegas MP, Guy GP Jr., de Moor JS. et al. For working-age cancer survivors, medical debt and bankruptcy create financial hardships. Health Affairs 2016; 35: 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garg PK, Jain BK.. New cancer drugs at the cost of bankruptcy: will the oncologist tell the patients the benefit in terms of days/weeks added to life? Oncologist 2014; 19: 1291.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A. et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Affairs 2013; 32: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. ACTION Study Group. Policy and priorities for national cancer control planning in low-and middle-income countries: Lessons from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Costs in Oncology prospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer 2017; 74: 26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pramesh CS, Badwe RA, Borthakur BB. et al. Delivery of affordable and equitable cancer care in India. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: e223–e233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alam K, Mahal A.. Economic impacts of health shocks on households in low and middle income countries: a review of the literature. Global Health 2014; 10: 21.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kankeu HT, Saksena P, Xu K, Evans DB.. The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Sys 2013; 11: 31.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010; 106.http://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/ (August 2017, date last Accessed). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Preker AS, Lindner ME, Chernichovsky D, Schellekens OP, Scaling up affordable health insurance: staying the course. World Bank Publications; 2013; 781.https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13836 (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 37. International Labour Organization. Social Health Protection: An ILO strategy towards universal access to health care. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2008; 108.http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_secsoc_5956.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Trade Organization. Compulsory licensing of pharmaceuticals and TRIPS. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/public_health_faq_e.htm (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 39. Herget G. WTO approves TRIPS amendment on importing under compulsory licensing. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev 2006; 11: 23–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kapp C. World Trade Organisation reaches agreement on generic medicines. New deal will make it easier for poorer countries to import cut-price generic drugs made under compulsory licensing. Lancet 2003; 362: 807.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lopes Gd L Jr., de Souza JA, Barrios C.. Access to cancer medications in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10: 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beall R, Kuhn R.. Trends in compulsory licensing of pharmaceuticals since the Doha Declaration: a database analysis. PLoS Med 2012; 9: e1001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000; 215.http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/ (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 44. World Health Organisation. Factsheet 323: Health and Human Rights. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs323/en/ ( August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 45. UN General Assembly. Global Health and Foreign Policy resolution 2012_67th GA. 2012; 6.https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/Global%20Health%20and%20Foreign%20Policy%20resolution%202012_67th%20GA.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 46. United Nations economic and Social Council. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary-General. 2016; 28.https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2016/secretary-general-sdg-report-2016–EN.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed).

- 47. World Health Organization. WHO list of priority medical devices for cancer management. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017; 252.http://www.who.int/medical_devices/publications/priority_med_dev_cancer_management/en/. (August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ullrich A, Ciardiello F, Bricalli G. et al. ESMO and WHO: 14 years of working in partnership on cancer control. ESMO Open 2016; 1: 6.http://esmoopen.bmj.com/content/esmoopen/1/3/e000012.full.pdf (August 2017, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]