Abstract

Our goal was to test a cascade model to identify developmental pathways, or chains of risk, from neighborhood deprivation in childhood to alcohol use disorder (AUD) in young adulthood. Using Swedish general population data, we examined whether exposure to neighborhood deprivation during early and middle childhood was associated with indicators of social functioning in adolescence and emerging adulthood, and whether these were predictive of AUD. Structural equation models showed exposure to neighborhood deprivation was associated with lower school achievement during adolescence, poor social functioning during emerging adulthood, and the development of AUD for both males and females. Understanding longitudinal pathways from early exposure to adverse environments to later AUD can inform prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, neighborhood deprivation, social functioning, Sweden

Excessive alcohol use is one of the leading causes of preventable death in the United States (US) (Mokdad et al., 2004). Alcohol use disorders (AUD) are debilitating, multi-faceted, recurrent conditions that impose a significant burden on the global population every year (Odlaug et al., 2016; Rehm and Imtiaz, 2016; Rehm et al., 2006; Whiteford et al., 2013). Alcohol-attributed productivity losses, disability and premature death are profound, especially among younger adults with AUD (Rehm et al., 2014). Although AUD is serious and prevalent, it also is preventable. Even in countries with strong social welfare systems, such as Sweden, supportive early neighborhood and family contexts can have a positive influence on later health outcomes, including AUD and other substance use disorders (Gauffin et al., 2013; Johansson et al., 2015; Kendler et al., 2014a; Sellstrom et al., 2011). There are many processes through which the neighborhood context may impact AUD, and understanding the longitudinal pathways from early exposure to adverse environments to later AUD can inform prevention and intervention. Given the intensive nature of the data required, this type of longitudinal study is relatively rare, however.

Developmental cascade theories suggest that successful completion of salient developmental tasks, or important accomplishments specific to a given developmental period, are interrelated over long periods, with earlier success (or difficulty) affecting later development through various pathways (Obradović et al., 2010; Roisman et al., 2004). Thus, disruptions in salient domains at each stage of development prospectively predict adverse outcomes at the next developmental stage (Eiden et al., 2016), thereby mediating the impact of the immediately preceding domain on later outcomes (Dodge et al., 2009). These cascading influences may then extend into adulthood, with early antisocial and high-risk behaviors being associated with adverse adult outcomes (Dodge et al., 2009).

Cascade models of adolescent substance use, more specifically, have explored how exposure to early-childhood risk factors leads to other risk factors later in childhood such as academic problems, with both early and later childhood risk factors linked in turn to adolescent (and later) substance use and associated problems (Sitnick et al., 2014). These “chains of risk” are important to identify as they offer insight into possible time points and strategies for intervention. By identifying early developmental correlates of AUD, targeted interventions may be directed at individuals when alcohol use is less entrenched and more malleable (Sitnick et al., 2014). Environmental interventions also can help prevent onset of alcohol use, as well as reducing heavy use and stopping progression to AUD (Ahern et al., 2015). In the current paper, we use population registry data from Sweden to examine pathways from exposure to neighborhood deprivation during early and middle childhood, focusing on school achievement during adolescence and social functioning during emerging adulthood as mediators of neighborhood effects on AUD.

Chains of risk: Beginning with neighborhood deprivation

Neighborhood deprivation poses many risks for child and adolescent development (Drukker et al., 2003; Kalff et al., 2001; Kohen et al., 2008; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Schneiders et al., 2003). Deprived neighborhoods have fewer educational and employment opportunities (Williams and Collins, 2001), poor-quality physical, social and service environments (Macintyre et al., 1993), and weaker informal social control over deviant health-related behaviors, including substance use (Drukker et al., 2003; Karriker-Jaffe, 2011; Sampson et al., 1997). Although all of these represent possible pathways from neighborhood deprivation to adverse health outcomes, the ways in which neighborhood deprivation influences AUD through these chains of risk remains relatively understudied.

Two possible mediators are school achievement during adolescence and social functioning during emerging adulthood, including attainment of higher education and employment (Masten et al., 2008). Neighborhood deprivation in childhood may result in lower school achievement due to exposure to poorer quality schools and fewer other educational resources, as well as due to exposure to stressors including crime and violence. Repeated or continual environmental stress can impair cognitive and social development (Shonkoff et al., 2009; Shonkoff and Garner, 2012) and reduce the likelihood of educational success. The influence of neighborhood deprivation on educational outcomes has been heavily investigated, with established links to lower scholastic performance (Ainsworth, 2002), increased school dropout (Harding, 2003; Rendón, 2014), and decreased likelihood of high school graduation (Crowder and South, 2011; Wodtke et al., 2016) and of obtaining a college degree (Owens, 2010). Adolescents who do poorly in school are at higher risk for substance use, and school performance and academic achievement are predictors of AUD and alcohol-related mortality in adulthood (Budhiraja and Landberg, 2016; Crum et al., 2006; Gauffin et al., 2015). However, little research has reported on school achievement as a mediator of the relationship between neighborhood deprivation and AUD in young adulthood. Research on social functioning that includes successful accomplishment of other developmentally-appropriate tasks during emerging adulthood—such as being gainfully employed or otherwise integrated as a productive and functioning member of society—as a mediator of this relationship is even rarer. A Danish study used population registry data to compare employment in early adulthood (ages 21–27) for people who had lived in deprived neighborhoods in childhood (ages 8–9) with a control group matched on gender and age but who had lived in a relatively affluent neighboring area (Lander et al., 2012); rates of unemployment were significantly higher for the people who had lived in the deprived area as children. Our study aims to build on this research by explicitly emphasizing educational attainment and employment as intermediate outcomes on the pathway from early neighborhood deprivation to young adult AUD.

Sensitive periods of exposure to neighborhood deprivation

In addition to identifying pathways from early risk factors to later outcomes, developmental theories suggest that timing and chronicity of exposure to adversity differentially influence many long-term health outcomes (Slopen et al., 2014). In terms of timing, exposure to risk factors and stressors during sensitive developmental periods may be particularly damaging (McCutcheon et al., 2010; Olff et al., 2007). Sensitive developmental periods refer to life phases such as childhood and adolescence during which exposures to risk factors such as neighborhood deprivation may be more strongly associated with long-term AUD risk. When considering school achievement, exposure to neighborhood deprivation during early childhood may be markedly detrimental from a basic developmental perspective (Heckman, 2006; Knudsen et al., 2006), however school quality during middle childhood may be essential during this early period of mastery of fundamental skills necessary for academic success later in adolescence.

In terms of chronicity, sustained exposure to neighborhood deprivation over time and across developmental periods may be more damaging than exposure of a shorter duration (Crowder and South, 2011; Wodtke et al., 2016; Wodtke et al., 2011). Despite recommendations that neighborhood effects should be studied within a longitudinal and developmental framework (Ferraro and Shippee, 2009; Wodtke et al., 2011), few prior studies have examined how the effects of neighborhood deprivation vary across different developmental periods (but see, for example, Wodtke et al., 2016), or how neighborhood effects may be strengthened with longer duration of exposure (as exceptions, see Cerdá et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2014), particularly on AUD.

Current study

The goal of this study is to test a cascade model to identify developmental pathways, or chains of risk, from neighborhood deprivation in early childhood to AUD in young adulthood. We use data from the Swedish general population to examine whether exposure to neighborhood deprivation during two key developmental periods (early and middle childhood) is associated with school achievement in adolescence and later difficulties with social functioning in emerging adulthood, and whether these, in turn, are predictive of onset of AUD in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Our hypothesis is that, after accounting for parental SES and parent externalizing behavior, another key predictor of child academic problems (Berg et al., 2016; Gifford et al., 2015) and substance use (Chassin et al., 1999; Kendler et al., 2013; Kendler et al., 2016c), exposure to neighborhood deprivation during early and middle childhood will be associated with lower school achievement in adolescence, as well as reduced social functioning in young adulthood, leading to subsequent development of AUD. We use stratified models to assess these pathways separately for men and women, as some research suggests sex differences in the effects of early adversity on later outcomes (Johansson et al., 2015; Kroneman et al., 2004).

Methods

Data Sources

We linked Swedish National Registers by the unique identification number assigned at birth or upon immigration to all Swedish inhabitants. The identification number was replaced by a serial number to assure anonymity. Ethical approval for this study was secured from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University.

The following national data sources were used to construct our analysis dataset: The Multi-Generation Register, linking individuals born after 1932 to their parents (Ekbom, 2011); the Swedish Census, containing information on household income and education every five years from 1960 to 1990; the Total Population Register, containing annual data on family structure from 1990 to 2013; the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies, including annual information on income, unemployment, social welfare recipients, and education from 1990 to 2012; the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register, containing hospitalizations for Swedish inhabitants from 1964 to 2012; the Swedish Outpatient Register, covering medical diagnosis in open care clinics from 2001 to 2012; the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register for prescriptions picked up at pharmacies by patients from July 2005 to March 2014; the Swedish Crime Register, covering all convictions in lower court from 1973 to 2012; the Suspicion register, identifying individuals strongly suspected of a crime from 1995 to 2012; the Swedish Mortality Register from 1973 to April 2014, containing causes and timing of death; and the National School Register, which contained information on school achievement from grade 9, the last year of compulsory school, between 1988 and 2013. Further details about each measure derived from these diverse sources are provided below.

Sample

We include Swedish born males (n=452,598) and females (n=431,371), born between 1979 and 1990, with at least one of the biological parents registered, at least one assessment of neighborhood deprivation in each age interval, and an assessment of school achievement. The median birth year was 1985.

Measures

Alcohol use disorder

Alcohol use disorder is characterized by physiological tolerance of high levels of alcohol, withdrawal symptoms upon cutting down or stopping consumption, impaired control over drinking, and physical, psychological and social problems stemming from use (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 1992). People with AUD come into contact with the healthcare system for many reasons, including seeking treatment for the disorder itself, as well as to treat associated physical and mental health conditions. For this study, AUD was derived from medical registers using International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes for alcohol abuse (excluding acute intoxication) and alcohol-attributed somatic diagnoses for conditions such as alcohol-related liver diseases, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy and gastritis (ICD-8 codes: 571.0, 291, 303, and 980; ICD-9 codes: V79B, 305A, 357F, 571A, 571B, 571C, 571D, 425F, 535D, 291, 303, and 980; and ICD-10 codes: E244, G312, G621, G721, I426, K292, K700, K701, K702, K703, K704, K709, K852, K860, O354, T510, T512, T511, T513, T518, T519, F101, F102, F103, F104, F105, F106, F107, F108, F109). We also identified cases of AUD for individuals in the Prescribed Drug Registry who had retrieved medications approved for the treatment of AUD: disulfiram (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System, N07BB01), acamprosate (N07BB03), and/or naltrexone (N07BB04). Additionally, we identified individuals with at least two convictions for or suspicions (that did not lead to conviction) of drunk driving or being drunk while in charge of maritime vessel (by law 1951:649, paragraphs 4 and 4A, and law 1994:1009, paragraphs 4 and 5; or suspicion codes 3005 and 3201). In Sweden, the legal threshold for impaired driving (0.02 blood alcohol content, BAC) is much lower than in the US, Canada and the United Kingdom (0.08 BAC) (World Health Organization, 2016). There is much less social tolerance for drunk driving, and casual drinkers do not typically drive after drinking. To reduce false positives, we required two or more criminal registrations for drunk driving; these individuals show markedly elevated odds of appearing in the medical registries as well (odds ratios ranging from 9.6 to 13.5 in one study of Swedish adoptees) (Kendler et al., 2015).

The outcome variables were timing of AUD onset, assessed for two age periods: by age 18 and between ages 19 and 24. For males with AUD before age 19, the mean age of onset was 15.9 (SD = 2.4), and for females it was 16.0 (SD = 1.9), with a median age of 16 for both males and females. The corresponding ages of AUD onset in emerging adulthood were 20.9 (SD = 2.3) for males and 20.6 (SD = 2.2) for females, with a median age of 21 for both sexes.

Neighborhood socioeconomic status

Neighborhood socioeconomic status (NSES) was derived yearly using a composite measure based on four neighborhood characteristics of the population aged 25–64: proportion with low education (<10 years), low income (defined as less than 50% of individual median income from all sources, including from interest and dividends), unemployment (not employed, excluding full-time students, those completing compulsory military service, and early retirees) and receipt of social welfare (at any time during that year). For a more detailed description of the measure, see Winkleby et al. (2007). A deprived neighborhood was defined as an area with a value below 1 standard deviation from the mean.

Although NSES was assessed yearly, we focus on the categorical measure of residence in a deprived area for least one year during each age period (early childhood being ages 0–6 and middle childhood being ages 7–12). This composite measure is calculated from 1985 onward. During the first period, 9.1% of males lived in a deprived area only one year, and 19.0% lived in a deprived area for at least two years. For females, the corresponding figures were 9.2% and 22.6%. During the second period, 5.8% of males lived in a deprived area only one year, and 18.0% lived in a deprived area for at least two years. For females, the corresponding figures were 5.9% and 18.2%. Tetrachoric correlations for consecutive years were about 0.8 on average, suggesting that a one-time assessment was a valid proxy for the period. Preliminary analyses showed that there was no strong evidence of a cumulative exposure effect for neighborhood deprivation, and the odds ratios for AUD were very similar for a 1-year exposure and for 2 or more years of exposure to neighborhood deprivation (versus no exposure). This suggests that any exposure to neighborhood deprivation during these sensitive developmental periods significantly raised risk of subsequently developing AUD. Additionally, for the preliminary models predicting AUD onset during adolescence and young adulthood, model fit (indicated by the Akaike information criterion, AIC) was better using the dichotomous indicators of exposure to neighborhood deprivation than when using a 7- or 6-category variable indicating the cumulative exposure during each time period of interest.

Social functioning during adolescence

Social functioning during adolescence was assessed using school achievement from the National School Registry, which provides average educational achievement for all students at the end of grade 9 (usually at age 16). These grades are considered to be important and culturally relevant, as they are used when applying to upper secondary school. The average scores were standardized by year and by gender to have mean 0 and standard deviation (SD) 1, with numbers greater than 0 indicating higher achievement (Kendler et al., 2016b). This variable is referred to as school achievement.

From 1988 to 1997, the school achievement score was expressed on a scale between 1 and 5 (mean was 3.1 (SD=0.69) for males and 3.41 (SD=0.67) for females), and it was a nationally-relative measure of school performance. Scores showed minimal inflation over time and followed a Gaussian distribution. From 1998 and onwards, the score was instead expressed on a scale from 10 to 320 (overall mean was 195.4 (SD=56.3) for boys and 217.7 (SD=57.9) for girls) utilizing a criterion referenced system, where students were assessed for their achievement of certain competencies. Scores were not standardized across schools and could not be represented by a Gaussian distribution.

Information on school achievement was fairly complete (2.9% missing), with slightly higher rates of missingness for residents of deprived neighborhoods: On average, 4.3% of children exposed to neighborhood deprivation during either period in childhood were missing school achievement, compared to 2.4% of their peers who were not exposed to neighborhood deprivation.

Social functioning during emerging adulthood

Social functioning during emerging adulthood was defined by a dichotomous measure capturing whether a person was employed, doing military service or going to the university at any time between age 19 and 24. Educational attainment is a developmental task in emerging adulthood that enables successful transition to adulthood (Roisman et al., 2004). Older adolescents and emerging adults with fewer prospects in terms of a higher education may use work as a means of successfully transitioning to adult roles (Mortimer and Shanahan, 2003). We used an indicator variable for low social functioning to denote those people who had a period of time when they were not engaged in any of these typical activities during emerging adulthood. A small group (944 (0.21%) of males and 598 (0.14%) of females) met criteria for low social functioning during this period.

Family socioeconomic status (SES)

Family socioeconomic status (SES) was a latent variable based on four components: low parental education (<10 years), low family income (below half the median), receipt of social welfare (at any time during the year), and unemployment (at any time during the year). Data were drawn from the Total Population Register, the Swedish Longitudinal Integration Database, and the Swedish Census for Education. The family SES variables are characteristics of the biological parents when the child was age 15, except for education, which represents the highest lifetime education of the parents. Almost a quarter (22.9% males and 22.5% females) met criteria for at least one of the indicators of low family SES.

Parent externalizing behavior

Parent externalizing behavior was defined as lifetime AUD, drug abuse or criminal behavior in either of the biological parents. Parental AUD was ascertained as for the primary outcome. Parental drug abuse is identified based on medical diagnoses, convictions and suspicions of drug crimes, and prescribed drugs for treatment of drug use disorder, as described in Kendler et al. (2012). Parental criminal behavior is identified based on convictions in lower court and includes violent crime, property crime and white collar crime; see Kendler et al. (2016a) for a more detailed description of this measure. Slightly more than a quarter (27.1% of males and 27.5% of females) had a parent registered for externalizing behavior at any time; this represents a combination of genetic and environmental risk for AUD (Edwards et al., 2017).

Statistical Methods

Preliminary analyses included bivariate correlations and logistic and linear regression models to examine unadjusted relationships between neighborhood deprivation, social functioning and AUD. Adjusted regression models accounted for family SES and parental externalizing behavior.

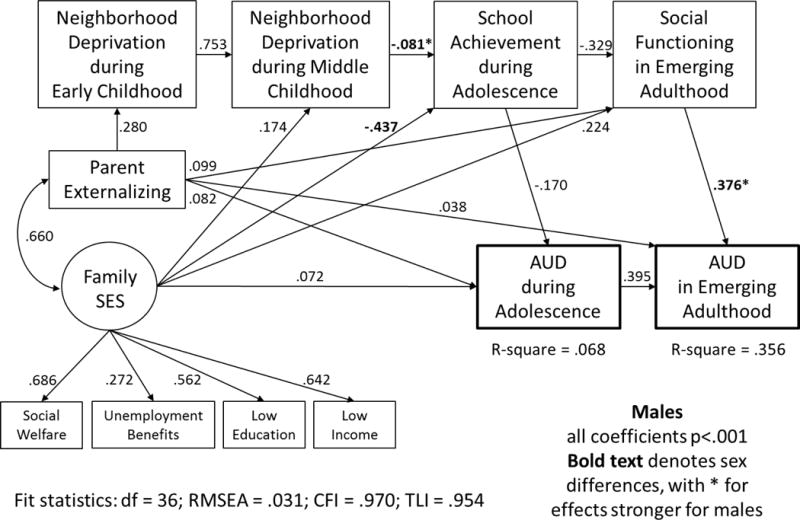

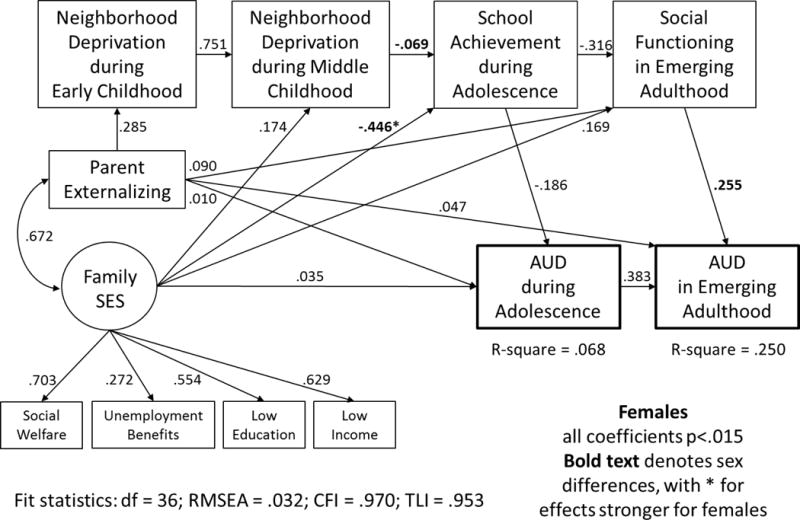

To quantify the influence of school achievement and social functioning as mediators on the pathway from neighborhood deprivation to AUD in emerging adulthood, we utilized a structural equation model (SEM). The model was built in steps. First, we added early (ages 0–6) and middle childhood (ages 7–12) exposure to neighborhood deprivation and estimated their influences on AUD before age 18 and in emerging adulthood. Next, we added parental externalizing behavior and a latent variable representing family SES, allowing correlation between these two family measures. We then added social functioning during adolescence and emerging adulthood, with paths from both family SES and parental externalizing behavior. School achievement during adolescence also had a path from middle childhood NSES. In each step, we evaluated the model utilizing indices reflecting explanatory power and parsimony: the Tucker Lewis index (TLI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) in combination with size, signs, and significance of the path estimates. Because family SES and parental externalizing behavior were highly correlated, it was not possible to include both of them as predictors for all variables in the model; the final analytic model therefore included select paths to neighborhood deprivation, social functioning and AUD outcomes as shown in Figures 1 and 2. The analysis was stratified by gender, and only results from the final models are presented. We conducted modeling using Mplus version 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) with the WLSMV (Weighted Least Square Mean- and Variance-Adjusted) estimator. Indirect effects were estimated using the Model Indirect sub-command (Muthén and Muthén, 2013).

Figure 1.

Standardized model coefficients for males

Figure 2.

Standardized model coefficients for females

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A small proportion (1.5%) of males had developed AUD by the end of adolescence; this increased to 2.5% who had developed AUD during emerging adulthood. Proportions were similar for females, with 1.5% who had developed AUD by the end of adolescence and 1.9% during emerging adulthood. About a quarter of the sample lived in a deprived neighborhood at some point from birth to age 6 (28.1% males, 28.3% females), with similar proportions who lived in a deprived neighborhood at some point between ages 7–12 (23.8% males, 24.1% females). About two-thirds of the children who lived in a deprived area during the first period also lived in a deprived area during the second period (61.5% males, 61.7% females).

For both males and females, those who developed AUD had greater exposure to neighborhood deprivation during both early and middle childhood than their counterparts who did not develop AUD (Table 1). They also had lower family SES and a higher prevalence of parental externalizing behavior, as well as lower school achievement during adolescence and lower social functioning in emerging adulthood than those who had not developed AUD during either adolescence or emerging adulthood. Correlations among all of the variables are shown in Table 2. The highest correlations (r = 0.79) were between exposure to neighborhood deprivation in early and middle childhood; all others were markedly lower.

Table 1.

Prevalence of neighborhood, family and social risk factors for people with and without alcohol use disorder (AUD) during adolescence and emerging adulthood

| AUD prior to end of adolescence (up to age 18) | AUD AUD in emerging adulthood (ages 19–24) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AUD | AUD | No AUD | AUD | |

| Males (N=452,598) | n=445,980 | n=6,618 | n=441,451 | n=11,147 |

| Early childhood (ages 0–6) | 125,048 | 2,274 (34.4%) | 123,245 | 4,077 (36.6%) |

| neighborhood deprivation | (28.0%) | (27.9%) | ||

| Middle childhood (ages 7–12) | 105,847 | 1,942 (29.3%) | 104,339 | 3,450 (31.0%) |

| neighborhood deprivation | (23.7%) | (23.6%) | ||

| Parent externalizing behavior | 119,950 | 2,921 (44.1%) | 117,506 | 5,365 (48.1%) |

| (lifetime) | (26.9%) | (26.6%) | ||

| Low family SES a | 99,539 (22.3%) | 2,303 (34.8%) | 97,801 (22.2%) | 4,041 (36.3%) |

| Family social welfare | 22,584 (5.1%) | 757 (11.4%) | 21,988 (5.0%) | 1,353 (12.1%) |

| Parental unemployment | 24,427 (5.5%) | 413 (6.2%) | 24,121 (5.5%) | 719 (6.4%) |

| Low parental education | 47,016 (10.5%) | 1,028 (15.5%) | 46,118 (10.4%) | 1,926 (17.3%) |

| Low family income | 30,514 (6.8%) | 863 (13.0%) | 29,831 (6.8%) | 1,546 (13.9%) |

| School achievement, mean (SD) | 0.03 (0.96) | −0.59 (1.11) | 0.04 (0.95) | −0.72 (1.10) |

| Poor social functioning | 878 (0.2%) | 66 (1.0%) | 754 (0.2%) | 190 (1.7%) |

| Females (N=431,371) | n=424,692 | n=6,679 | n=423,327 | n=8,044 |

| Early childhood (ages 0–6) | 119,982 | 2,286 (34.2%) | 119,472 | 2,796 (34.8%) |

| neighborhood deprivation | (28.3%) | (28.2%) | ||

| Middle childhood (ages 7–12) | 101,920 | 1,896 (28.4%) | 101,512 | 2,304 (28.6%) |

| neighborhood deprivation | (24.0%) | (24.0%) | ||

| Parent externalizing behavior | 115,718 | 2,976 (44.6%) | 114,995 | 3,699 (46.0%) |

| (lifetime) | (27.2%) | (22.7%) | ||

| Low family SES a | 96,480 (22.7%) | 2,276 (34.1%) | 96,158 (22.7%) | 2,598 (32.3%) |

| Family social welfare | 22,567 (5.3%) | 784 (1.7%) | 22,510 (5.3%) | 841 (0.1%) |

| Parental unemployment | 23,377 (5.5%) | 430 (6.4%) | 23,337 (5.1%) | 470 (5.8%) |

| Low parental education | 45,085 (10.6%) | 968 (14.5%) | 44,940 (10.6%) | 1,113 (13.8%) |

| Low family income | 30,010 (7.1%) | 887 (13.3%) | 29,851 (7.1%) | 1,046 (13.0%) |

| School achievement, mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.95) | −0.63 (1.14) | 0.04 (0.95) | −0.59 (1.13) |

| Poor social functioning | 561 (0.1%) | 37 (0.6%) | 545 (0.1%) | 53 (0.7%) |

Family had at least one of the four indicators of low socioeconomic status (SES).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) AUD prior to end of adolescence (up to age 18) | — | 0.399 | 0.069 | 0.050 | −0.242 | 0.208 | 0.178 | 0.176 | 0.030 | 0.079 | 0.153 |

| (2) AUD in emerging adulthood (ages 19–24) | 0.446 | — | 0.075 | 0.060 | −0.242 | 0.248 | 0.208 | 0.156 | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.148 |

| (3) Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 0.071 | 0.104 | — | 0.787 | −0.179 | 0.165 | 0.220 | 0.246 | 0.129 | 0.218 | 0.250 |

| (4) Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 0.069 | 0.096 | 0.787 | — | −0.190 | 0.155 | 0.211 | 0.302 | 0.136 | 0.272 | 0.254 |

| (5) School achievement during adolescence | −0.235 | −0.323 | −0.168 | −0.178 | — | −0.532 | −0.314 | −0.383 | −0.085 | −0.349 | −0.257 |

| (6) Poor social functioning in emerging adulthood | 0.242 | 0.387 | 0.181 | 0.190 | −0.540 | — | 0.347 | 0.380 | 0.121 | 0.240 | 0.263 |

| (7) Parent externalizing behavior | 0.184 | 0.251 | 0.214 | 0.206 | −0.304 | 0.280 | — | 0.435 | 0.108 | 0.274 | 0.499 |

| (8) Family social welfare | 0.175 | 0.214 | 0.234 | 0.287 | −0.357 | 0.345 | 0.422 | — | 0.217 | 0.351 | 0.350 |

| (9) Parental unemployment | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.125 | 0.137 | −0.077 | 0.086 | 0.102 | 0.213 | — | 0.171 | 0.175 |

| (10) Low parental education | 0.099 | 0.141 | 0.217 | 0.272 | −0.350 | 0.253 | 0.268 | 0.337 | 0.164 | — | 0.282 |

| (11) Low family income | 0.135 | 0.187 | 0.244 | 0.256 | −0.255 | 0.200 | 0.494 | 0.359 | 0.194 | 0.286 | — |

Note: Females (N=431,371) above and males (N=452,598) below diagonal.

Preliminary Regression Models

Logistic regression models showed evidence of the hypothesized relationships between neighborhood deprivation and AUD (Table 3). Males and females exposed to neighborhood deprivation in early childhood and/or in middle childhood had higher odds of developing AUD by the end of adolescence and during emerging adulthood (ORs ranged from 1.32 to 1.48), even after adjusting for parental externalizing behavior and family SES (adjusted odds ratios, aORs, ranged from 1.07 to 1.22). One exception was the adjusted model of the association between neighborhood deprivation in middle childhood with AUD onset prior to the end of adolescence for females (aOR=1.04).

Table 3.

Relationship between early exposure to neighborhood deprivation and alcohol use disorder (AUD) during adolescence and emerging adulthood

| Males (N=452,598) |

Females (N=431,371) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUD by age 18 OR (95% CI) |

AUD between ages 19–24 OR (95% CI) |

AUD by age 18 OR (95% CI) |

AUD between ages 19–24 OR (95% CI) |

|

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) | 1.48 (1.43, 1.55) | 1.32 (1.26, 1.39) | 1.35 (1.29, 1.42) |

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.27) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.21) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 1.85 (1.76, 1.95) | 2.16 (2.08, 2.25) | 1.86 (1.77, 1.96) | 2.04 (1.95, 2.14) |

| Family social welfare | 1.73 (1.59, 1.87) | 1.73 (1.62, 1.84) | 1.71 (1.58, 1.86) | 1.49 (1.37, 1.60) |

| Parental unemployment | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.91 (0.83, 1.00) |

| Low parental education | 1.21 (1.13, 1.29) | 1.33 (1.26, 1.40) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.18) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.21) |

| Low family income | 1.40 (1.29, 1.51) | 1.39 (1.31, 1.48) | 1.40 (1.30, 1.51) | 1.36 (1.27, 1.46) |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 1.36 (1.27, 1.41) | 1.45 (1.39, 1.51) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) |

| aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 1.86 (1.77, 1.96) | 2.18 (2.09, 2.27) | 1.88 (1.78, 1.98) | 2.06 (1.96, 2.16) |

| Family social welfare | 1.73 (1.59, 1.87) | 1.73 (1.62, 1.84) | 1.72 (1.59, 1.87) | 1.49 (1.38, 1.61) |

| Parental unemployment | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.91 (0.83, 1.00) |

| Low parental education | 1.21 (1.12, 1.29) | 1.33 (1.26, 1.40) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.19) | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) |

| Low family income | 1.40 (1.30, 1.51) | 1.40 (1.32, 1.49) | 1.41 (1.31, 1.52) | 1.37 (1.28, 1.47) |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.40) | 1.26 (1.18, 1.34) | 1.29 (1.22, 1.37) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.28) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 1.11 (1.04, 1.18) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25) | 1.14 (1.07, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 1.04 (0.98, 1.12) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 1.85 (1.76, 1.95) | 2.16 (2.08, 2.25) | 1.89 (1.77, 1.97) | 2.04 (1.95, 2.14) |

| Family social welfare | 1.72 (1.59, 1.87) | 1.72 (1.61, 1.83) | 1.72 (1.59, 1.86) | 1.48 (1.37, 1.60) |

| Parental unemployment | 0.96 (0.86, 1.06) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.91 (0.83, 1.00) |

| Low parental education | 1.20 (1.12, 1.29) | 1.32 (1.26, 1.39) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.12) |

| Low family income | 1.39 (1.29, 1.51) | 1.39 (1.31, 1.47) | 1.40 (1.30, 1.51) | 1.36 (1.17, 1.46) |

In general, the elevated risk of developing AUD was similar for both periods of exposure to neighborhood deprivation; for example, for males, early childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation increased the odds of developing AUD prior to the end of adolescence by 7% (aOR = 1.07) and middle childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation increased the odds of developing AUD prior to the end of adolescence by 11% (aOR = 1.11). When both exposure periods were included together (also Table 3), unadjusted models showed each period of exposure to neighborhood deprivation was associated with increased odds of developing AUD in adolescence and young adulthood; in adjusted models, the early exposure period (ages 0–6) emerged as most strongly related to AUD onset for both males and females.

When considering the hypothesized mediating variables, regression models confirmed the expected relationships between neighborhood deprivation and both school achievement during adolescence and social functioning during emerging adulthood. Males and females exposed to neighborhood deprivation in early childhood and/or in middle childhood had lower school achievement during adolescence (Table 4) and higher odds of poor social functioning during emerging adulthood (Table 5). As with the elevated risk of developing AUD, the relationships with the hypothesized mediators were similar for both periods of exposure to neighborhood deprivation. For example, for males, early childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation decreased school achievement by 0.17 SDs (the unit for the standardized score) on average (adjusted B = −0.17) and middle childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation was associated with decreased school achievement by 0.19 SDs on average (adjusted B = −0.19). When both exposure periods were included together, each maintained a significant association with school achievement, even in the adjusted model. Sensitivity analyses showed that the relationship of school achievement with neighborhood deprivation did not vary significantly for the two grade scoring systems (pre- and post-1998; results available upon request).

Table 4.

Relationships of early exposure to neighborhood deprivation with school achievement during adolescence

| Males (N=452,598) |

Females (N=431,371) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Intercept | 0.11 (0.10, 0.11) | 0.27 (0.26, 0.27) | 0.11 (0.11, 0.12) | 0.28 (0.28, 0.28) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | −0.29 (−0.30, −0.29) | −0.17 (−0.18, −0.17) | −0.29 (−0.29, −0.28) | −0.16 (−0.16, −0.15) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | −0.37 (−0.38, −0.36) | −0.38 (−0.39, −0.37) | ||

| Family social welfare | −0.50 (−0.51, −0.49) | −0.56 (−0.57, −0.55) | ||

| Parental unemployment | −0.04 (−0.06, −0.03) | −0.05 (−0.06, −0.03) | ||

| Low parental education | −0.48 (−0.49, −0.47) | −0.48 (−0.48, −0.47) | ||

| Low family income | −0.22 (−0.24, −0.21) | −0.22 (−0.23, −0.21) | ||

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 0.10 (0.09, 0.10) | 0.26 (0.26, 0.27) | 0.11 (0.11, 0.11) | 0.28 (0.27, 0.28) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | −0.32 (−0.33, −0.32) | −0.19 (−0.19, −0.18) | −0.32 (−0.32, −0.31) | −0.17 (−0.17, −0.16) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | −0.37 (−0.38, −0.37) | −0.38 (−0.39, −0.38) | ||

| Family social welfare | −0.49 (−0.50, −0.48) | −0.55 (−0.57, −0.54) | ||

| Parental unemployment | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.03) | −0.04 (−0.06, −0.03) | ||

| Low parental education | −0.48 (−0.48, −0.47) | −0.47 (−0.48, −0.46) | ||

| Low family income | −0.22 (−0.24, −0.21) | −0.22 (0.23, −0.21) | ||

| B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | 0.13 (0.12, 0.13) | 0.28 (0.27, 0.28) | 0.13 (0.13, 0.14) | 0.29 (0.29, 0.29) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | −0.18 (−0.19, −0,17) | −0.11 (−0.12, −0.11) | −0.17 (−0.18, −0.16) | −0.10 (−0.11, −0.09) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | −0.22 (−0.23, −0.21) | −0.12 (−0.13, −0.11) | −0.22 (−0.22, −0.21) | −0.11 (−0.12, −0.10) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | −0.37 (−0.37, −0.36) | −0.38 (−0.38, −0.37) | ||

| Family social welfare | −0.49 (−0.50, −0.48) | −0.55 (−0.56, −0.54) | ||

| Parental unemployment | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.03) | −0.04 (−0.05, −0.03) | ||

| Low parental education | −0.47 (−0.48, −0.46) | −0.47 (−0.47, −0.45) | ||

| Low family income | −0.22 (−0.23, −0.21) | −0.22 (−0.23, −0.21) | ||

Table 5.

Relationships of early exposure to neighborhood deprivation with low social functioning during emerging adulthood

| Males (N=452,598) |

Females (N=431,371) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 2.44 (2.15, 2.78) | 1.52 (1.33, 1.73) | 2.43 (2.07, 2.86) | 1.59 (1.34, 1.88) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 3.34 (2.88, 3.86) | 2.57 (2.15, 3.07) | ||

| Family social welfare | 3.77 (3.24, 4.39) | 3.64 (3.00, 4.42) | ||

| Parental unemployment | 1.22 (0.99, 1.51) | 1.14 (0.87, 1.50) | ||

| Low parental education | 1.05 (1.77, 2.37) | 2.38 (1.98, 2.85) | ||

| Low family income | 1.76 (1.50, 2.06) | 1.38 (1.11, 1.70) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 2.74 (2.41, 3.12) | 1.60 (1.40, 1.83) | 2.43 (2.07, 2.86) | 1.47 (1.24, 1.74) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 3.35 (2.90, 3.88) | 2.61 (2.19, 3.12) | ||

| Family social welfare | 3.67 (3.15, 4.27) | 3.61 (2.97, 4.39) | ||

| Parental unemployment | 1.22 (0.99, 1.50) | 1.15 (0.88, 1.51) | ||

| Low parental education | 2.01 (1.73, 2.33) | 2.36 (1.97, 2.84) | ||

| Low family income | 1.75 (1.49, 2.05) | 1.39 (1.13, 1.72) | ||

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 0–6 | 1.63 (1.39, 1.91) | 1.28 (1.09, 1.49) | 1.80 (1.48, 2.20) | 1.45 (1.19, 1.76) |

| Neighborhood deprivation ages 7–12 | 2.05 (1.75, 2.41) | 1.40 (1.20, 1.65) | 1.71 (1.40, 2.09) | 1.20 (0.98, 1.47) |

| Parent externalizing behavior | 3.31 (2.86, 3.83) | 2.57 (2.14, 3.06) | ||

| Family social welfare | 3.64 (3.13, 4.25) | 3.57 (2.94, 3.24) | ||

| Parental unemployment | 1.21 (0.98, 1.49) | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) | ||

| Low parental education | 1.99 (1.72, 2.31) | 2.34 (1.95, 2.81) | ||

| Low family income | 1.73 (1.48, 2.03) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.69) | ||

The pattern was similar for poor social functioning in emerging adulthood, with early childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation increasing the odds of poor social functioning by 52% (aOR = 1.52) and middle childhood exposure to neighborhood deprivation increasing the odds by 60% (aOR = 1.60) for males. When both exposure periods were included together, for boys, both unadjusted and adjusted models showed each period of exposure to neighborhood deprivation was associated with increased odds of low social functioning in young adulthood, with slightly stronger effects for exposure to neighborhood deprivation during middle childhood compared to early childhood. For girls, in the adjusted models the early exposure period (ages 0–6) was more strongly related to poor social functioning in emerging adulthood than the later exposure period.

Structural Equation Models

Coefficients from the final structural equation model are included in Table 6. For males, the model explained 35.6% of the variance in AUD in emerging adulthood. Model fit statistics are shown on Figure 1. For females, the model explained 25% of the variance in AUD in emerging adulthood, with model fit statistics shown on Figure 2. As hypothesized, for both males and females, exposure to neighborhood deprivation was associated with lower school achievement during adolescence, poor social functioning during emerging adulthood, and the development of AUD. Family SES and parental externalizing behavior also were associated with the measures of social functioning and the AUD outcomes as expected.

Table 6.

Coefficients from full structural equation model

| Males (N=452,598) | Females (N=431,371) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Estimate | 95% CIs | Estimate | 95% CIs | |

| Latent variable (Family SES) | ||||

| Family SES by Social Welfare Benefits | 0.686 | (0.679, 0.693) | 0.703 | (0.696, 0.710) |

| Family SES by Unemployment Benefits | 0.272 | (0.264. 0.280) | 0.272 | (0.264, 0.281) |

| Family SES by Low Parental Education | 0.562 | (0.555, 0.568) | 0.554 | (0.547, 0.560) |

| Family SES by Low Income | 0.642 | (0.635, 0.648) | 0.629 | (0.623, 0.635) |

| Path estimates | ||||

| Neighborhood Deprivation ages 0–6 on Parent Externalizing | 0.280 | (0.275, 0.285) | 0.285 | (0.280, 0.290) |

| Neighborhood Deprivation ages 7–12 on Family SES | 0.174 | (0.169, 0.179) | 0.174 | (0.169, 0.179) |

| Neighborhood Deprivation ages 7–12 on Neighborhood Deprivation ages 0–6 | 0.753 | (0.750, 0.755) | 0.751 | (0.748, 0.754) |

| School Achievement on Family SES | −0.437 | (−0.441, −0.443) | −0.446 | (−0.450, −0.441) |

| School Achievement on Neighborhood Deprivation ages 7–12 | −0.081 | (−0.085, −0.077) | −0.069 | (−0.073, −0.065) |

| Poor Social Functioning on Parent Externalizing | 0.099 | (0.060, 0.139) | 0.090 | (0.041, 0.147) |

| Poor Social Functioning on Family SES | 0.224 | (0.181, 0.267) | 0.169 | (0.109, 0.229) |

| Poor Social Functioning on School Achievement | −0.329 | (−0.349, −0.308) | −0.316 | (−0.340, −0.291) |

| AUD before 18 on Parent Externalizing | 0.082 | (0.059, 0.104) | 0.100 | (0.076, 0.123) |

| AUD before 18 on Family SES | 0.072 | (0.042, 0.100) | 0.035 | (0.004, 0.065) |

| AUD before 18 on School Achievement | −0.170 | (−0.181, −0.159) | −0.186 | (−0.198, −0.175) |

| AUD in Emerging Adulthood on Parent Externalizing | 0.038 | (0.021, 0.056) | 0.047 | (0.030, 0.065) |

| AUD in Emerging Adulthood on AUD before 18 | 0.395 | (0.380, 0.410) | 0.383 | (0.365, 0.400) |

| AUD in Emerging Adulthood on Poor Social Functioning | 0.376 | (0.354, 0.398) | 0.255 | (0.229, 0.281) |

| Correlations | ||||

| Family SES with Parent Externalizing | 0.660 | (0.655, 0.666) | 0.672 | (0.667, 0.678) |

Note: Substantive pathways with non−overlapping 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for males and females in bold type.

In addition to differences in the model R-squares for males and females, three substantive pathways varied by gender (as indicated by non-overlapping confidence intervals from the sex-stratified models). There were stronger associations between exposure to neighborhood deprivation during middle childhood and school achievement during adolescence and between poor social functioning in emerging adulthood and AUD in emerging adulthood for males than for females; for females, the association between family SES and school achievement during adolescence was stronger than it was for males.

For males, the indirect effects from neighborhood deprivation in early childhood (between ages 0–6) to AUD in emerging adulthood (total indirect effect: standardized coefficient, std coef = 0.012) suggested one pathway going through neighborhood deprivation in middle childhood (ages 7–12), to school achievement in adolescence, and to AUD prior to age 18 (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.004), and another going through neighborhood deprivation in middle childhood (ages 7–12), to school achievement in adolescence, and to low social functioning in emerging adulthood (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.008). Inclusion of a residual direct effect from neighborhood deprivation to AUD did not improve model fit. The indirect effects from low family SES to AUD in emerging adulthood (total indirect effect: std coef = 0.199) revealed the largest specific indirect pathway was from family SES directly to low social functioning in emerging adulthood (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.084); this pathway was substantially larger than either involving exposure to neighborhood deprivation (specific indirect effects: std coefs = 0.001 and 0.002).

For females, as for males, the indirect effects from neighborhood deprivation in early childhood (between ages 0–6) to AUD in emerging adulthood (total indirect effect: std coef = 0.008) also suggested two pathways, with one going through neighborhood deprivation in middle childhood (ages 7–12), to school achievement in adolescence, and to AUD prior to age 18 (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.004), and another going through neighborhood deprivation in middle childhood (ages 7–12), to school achievement in adolescence, and to low social functioning in emerging adulthood (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.004). As in the model for males, inclusion of a residual direct effect from neighborhood deprivation to AUD did not improve model fit for females. The indirect effects from low family SES to AUD in emerging adulthood (total indirect effect: std coef = 0.130) also showed the largest specific indirect pathway was from family SES directly to low social functioning in emerging adulthood (specific indirect effect: std coef = 0.046). As for males, this pathway was substantially larger than either involving exposure to neighborhood deprivation (specific indirect effects: both std coefs = 0.001).

Discussion

Using population registry data from Sweden, we examined direct and indirect pathways linking early residence in deprived neighborhoods with the development of alcohol use disorders by age 24. Our results suggest there are important chains of risk from early exposure to neighborhood deprivation in childhood to AUD in emerging adulthood that operate indirectly through school achievement in adolescence and later indicators of social functioning, including educational attainment and gainful employment or enrollment in military service during emerging adulthood. Although these pathways were modest in strength, given the prevalence of exposure to neighborhood deprivation (approximately 25% in this population) and the opportunity to identify adolescents through the school system who may be at elevated risk for AUD later in life, greater attention to these indirect mechanisms is warranted. In countries such as the US that do not have such strong traditions of social welfare and that have schools that are more economically segregated and that vary widely in quality, these effects may be even greater than in Sweden. Thus, our findings merit replication with longitudinal data in other national contexts. Because these indicators of social functioning are strongly related to many health outcomes in addition to AUD (Cutler and Lleras-Muney, 2010; Link and Phelan, 1995), future studies also should assess whether and how school quality may impact educational attainment and employment outcomes for adolescents and young adults exposed to neighborhood deprivation early in the lifecourse.

The structural equation models explained more of the variance in young men’s AUD development than young women’s, and there were differences in the strength of the associations of exposure to neighborhood deprivation during middle childhood and of family SES with school achievement during adolescence for males and females. Neighborhood deprivation was more strongly associated with school achievement of adolescent boys than girls, while family SES was more strongly associated with school achievement for adolescent girls than boys. Due to variations in parenting and other factors, during middle childhood there may be differential exposure of boys and girls to potentially negative neighborhood influences (Kroneman et al., 2004), such as deviant peer networks, that could contribute to the observed gender differences in negative academic outcomes during adolescence. Other research has found stronger effects of the family context than of the neighborhood context for girls (Kroneman et al., 2004), and this also may be due in part to differences in parenting practices during childhood and adolescence. Future longitudinal studies with detailed information on parent-child bonding and parental monitoring would be informative for further understanding the chains of risk for young residents of deprived neighborhoods.

When comparing exposure to neighborhood deprivation for early and middle childhood, the adjusted regression models suggested that early childhood exposures (from birth to age 6) were more strongly associated with AUD than later childhood exposures (from ages 7–12). However, both periods showed evidence of independent effects on school achievement during adolescence. These findings suggest there is a need to provide services to support the youngest residents of deprived neighborhoods, perhaps even prior to starting formal schooling (Heckman, 2006; Knudsen et al., 2006), as well as to continue to intervene to ameliorate negative effects of neighborhood deprivation later in childhood. Effective early childhood interventions include home visits by nurses to support new parents (Olds et al., 1998), high-quality preschool programs such as Head Start (Barnett, 1998; Heckman et al., 2013; Reynolds et al., 2001), and providing support to families (particularly those with pre-adolescent children) so they can relocate to a different neighborhood (Chetty et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2009; Leventhal and Dupere, 2011). Interventions to support economically disadvantaged parents in obtaining higher education, professional certifications and more stable employment (Holzer and Martinson, 2005; Kane and Rouse, 1999; Leigh and Gill, 1997; Mathur, 2004) also may benefit their children, particularly in single-parent households.

We did not include measures of neighborhood deprivation after middle childhood. Future research should examine effects on substance use and AUD of later exposure to neighborhood deprivation, including during adolescence. Adolescence may be a highly sensitive period for environmental exposures on health behaviors (Kravitz-Wirtz, 2016c), as the typical independence gained during the teenage years may increase exposure to environmental risk factors such as deviant peers who also live in the neighborhood.

It is noteworthy that the preliminary analyses showed there was not strong evidence of a cumulative exposure effect for neighborhood deprivation independent of the effects of low family SES on the AUD and social functioning outcomes. It is unknown whether this pattern would hold in other national contexts, as there is some evidence from US studies to support the cumulative disadvantage hypothesis in relation to educational attainment (Crowder and South, 2011), alcohol use (Cerdá et al., 2010), smoking (Kravitz-Wirtz, 2016b) and general health status (Clarke et al., 2014; Kravitz-Wirtz, 2016a). In the US, other research suggests that, although some families are more mobile than others, in general families do not move to different types of neighborhoods: Data for children under age 16 in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics suggest single-point-in-time estimates of neighborhood exposures are very highly correlated with multi-year averages (r<.95), even for families who move (r<.83) (Kunz et al., 2003). In this Swedish sample, a majority (over 60%) of the children who lived in a deprived neighborhood in early childhood also lived in a deprived neighborhood during middle childhood. It is possible that compounded exposure to neighborhood deprivation may be worse in a context of limited social mobility. The robust associations of low family SES with AUD and the educational mediators also suggests that targeted services to support families who receive social welfare benefits may offer substantial benefit for children’s health and development.

This study has several important strengths, such as the longitudinal, population-representative data and rigorous assessment of direct effects and indirect pathways from early exposure to neighborhood deprivation to AUD in emerging adulthood. One caveat relates to the low prevalence of AUD in our study relative to survey-based prevalence studies. Given the ascertainment of AUD cases using healthcare, pharmacy and criminal registries, these cases of AUD are likely to be more severe than other instances of alcohol misuse that do not require treatment; it also could be argued that these are the individuals most in need of early intervention, however. Another limitation is that we focused on family factors by including a composite measure of family SES and an indicator of parental externalizing behaviors as a measure of genetic and environmental risk for AUD. One Swedish study examining siblings who lived in different neighborhoods suggested that unobserved family confounders might explain much of the neighborhood risk for criminal behavior in emerging adulthood (Sariaslan et al., 2013). Others using rigorous co-sibling designs have shown an effect of neighborhood deprivation on drug use disorders that is at least partly causal though (Kendler et al., 2014a; Kendler et al., 2014b). Of note, familial confounding of the association between neighborhood deprivation and drug use disorders may be greater when assessing substance use outcomes at younger ages compared to later in the lifecourse (Kendler et al., 2014b), and associations of neighborhood deprivation with substance use are generally weaker, or in the opposite direction (that is, with neighborhood deprivation being associated with less substance use), for adolescents than for adults (Karriker-Jaffe, 2011). Analysis of genetically-informative data to further disentangle family and neighborhood effects over the lifecourse would be beneficial.

The Swedish setting for this study may limit the generalizability of findings to similar cultural contexts. However, the heritability of AUD is highly similar in Sweden and the US (Kendler et al., 1997; Prescott and Kendler, 1999), and although the exact manifestation of the examined processes may vary across national contexts, it is likely that major mechanisms underlying AUD are broadly similar across Western countries. Also of note, demographic and economic changes in Sweden during the last decades have resulted in a more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population, and there is a social gradient of AUD in Sweden that is similar to that in the US. Additionally, the universal health care system in Sweden could be regarded as a strength in the interpretation of results, as it holds constant an important potential confounder in the existing social gradient in health. Given our focus on neighborhood effects on AUD over the lifecourse, these findings from Sweden are relevant for informing replication research, prevention and treatment in the US and other developed countries.

Our findings suggest early exposure to neighborhood deprivation may trigger chains of risk that culminate in the development of AUD. Future lifecourse research utilizing co-relative designs and techniques such as propensity scoring may assist in distinguishing causal influences from confounding effects. Targeted interventions to reach young residents of deprived neighborhood and their families could have substantial long-term benefits for reducing the burden of alcohol on adolescents and young adults. These prevention efforts also may result in other favorable health and social outcomes related to greater school achievement, educational attainment and gainful employment over the lifecourse.

Highlights.

Early neighborhood deprivation was associated with later social functioning.

Poor social functioning was associated with later alcohol use disorder.

Targeted interventions in deprived neighborhoods may prevent alcohol use disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA023534, M-PIs K.S. Kendler & K. Sundquist), ALF Skåne (K. Sundquist) and Forte, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life & Welfare (Reg.nr: 2013-1836 to K. Sundquist). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication to disseminate the findings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Ahern J, Balzer L, Galea S. The roles of outlet density and norms in alcohol use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;151:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth JW. Why does it take a village? The mediation of neighborhood effects on educational achievement. Social Forces. 2002;81:117–152. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. DSM-5; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett WS. Long-term cognitive and academic effects of early childhood education on children in poverty. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27:204–207. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg L, Back K, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Parental alcohol-related disorders and school performance in 16-year-olds-a Swedish national cohort study. Addiction. 2016;111:1795–1803. doi: 10.1111/add.13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja M, Landberg J. Socioeconomic disparities in alcohol-related mortality in Sweden, 1991–2006: A register-based follow-up study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:307–314. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Diez Roux AV, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe C. The relationship between neighborhood poverty and alcohol use: Estimation by marginal structural models. Epidemiology. 2010;21:482–489. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e13539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:106–119. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF. The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review. 2016;106:855–902. doi: 10.1257/aer.20150572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Morenoff J, Debbink M, Golberstein E, Elliott MR, Lantz PM. Cumulative exposure to neighborhood context: consequences for health transitions over the adult life course. Research on Aging. 2014;36:115–142. doi: 10.1177/0164027512470702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder K, South SJ. Spatial and temporal dimensions of neighborhood effects on high school graduation. Social Science Research. 2011;40:87–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Juon HS, Green KM, Robertson J, Fothergill K, Ensminger M. Educational achievement and early school behavior as predictors of alcohol-use disorders: 35-year follow-up of the Woodlawn Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:75–85. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2009;74:vii-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drukker M, Kaplan C, Feron F, van Os J. Children’s health-related quality of life, neighbourhood socio-economic deprivation and social capital. A contextual analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AC, Lönn SL, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Sundquist J, Kendler KS, Sundquist K. Time-specific and cumulative effects of exposure to parental externalizing behavior on risk for young adult alcohol use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;72:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Lessard J, Colder CR, Livingston J, Casey M, Leonard KE. Developmental cascade model for adolescent substance use from infancy to late adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2016;52:1619–1633. doi: 10.1037/dev0000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekbom A. The Swedish Multi-generation Register. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;675:215–220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-423-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF, Shippee TP. Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist. 2009;49:333–343. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauffin K, Hemmingsson T, Hjern A. The effect of childhood socioeconomic position on alcohol-related disorders later in life: a Swedish national cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:932–938. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauffin K, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. School performance and alcohol-related disorders in early adulthood: a Swedish national cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:919–927. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EJ, Sloan FA, Eldred LM, Evans KE. Intergenerational effects of parental substance-related convictions and adult drug treatment court participation on children’s school performance. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85:452–468. doi: 10.1037/ort0000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ. Counterfactual models of neighborhood effects: the effect of neighborhood poverty on dropping out and teenage pregnancy. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;109:676–719. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J, Pinto R, Savelyev P. Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. The American Economic Review. 2013;103:2052–2086. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science. 2006;312:1900–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Martinson K. Can we improve job retention and advancement among low-income working parents? Urban Institute, Georgetown University; 2005. p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L, Langille L, Lyons R, Hughes J, Martin D, Winstanley V. Does moving from a high-poverty to lower-poverty neighborhood improve mental health? A realist review of ‘Moving to Opportunity’. Health & Place. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson K, San Sebastian M, Hammarstrom A, Gustafsson PE. Neighbourhood disadvantage and individual adversities in adolescence and total alcohol consumption up to midlife-Results from the Northern Swedish Cohort. Health Place. 2015;33:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalff AC, Kroes M, Vles JS, Hendriksen JG, Feron FJ, Steyaert J, van Zeben TM, Jolles J, van Os J. Neighbourhood level and individual level SES effects on child problem behaviour: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:246–250. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane TJ, Rouse CE. The community college: Educating students at the margin between college and work. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1999;13:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Areas of disadvantage: a systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Edwards A, Hickman M, Heron J, Macleod J, Lewis G, Dick DM. Dimensions of parental alcohol use/problems and offspring temperament, externalizing behaviors, and alcohol use/problems. Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research. 2013;37:2118–2127. doi: 10.1111/acer.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Ji J, Edwards AC, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. An extended Swedish national adoption study of alcohol use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:211–218. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Lonn SL, Maes HH, Lichtenstein P, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. A Swedish population-based multivariate twin study of externalizing disorders. Behav Genet. 2016a;46:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s10519-015-9741-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Maes HH, Sundquist K, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J. Genetic and family and community environmental effects on drug abuse in adolescence: a Swedish national twin and sibling study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014a;171:209–217. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Mezuk B, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. A Swedish national prospective and co-relative study of school achievement at age 16, and risk for schizophrenia, other nonaffective psychosis, and bipolar illness. Schizophr Bull. 2016b;42:77–86. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. The causal nature of the association between neighborhood deprivation and drug abuse: a prospective national Swedish co-relative control study. Psychol Med. 2014b;44:2537–2546. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. The rearing environment and risk for drug abuse: a Swedish national high-risk adopted and not adopted co-sibling control study. Psychol Med. 2016c;46:1359–1366. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Neale MC, Pedersen NL. Temperance board registration for alcohol abuse in a national sample of Swedish male twins, born 1902 to 1949. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:178–184. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140090015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Sundquist K, Ohlsson H, Palmer K, Maes H, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Genetic and familial environmental influences on the risk for drug abuse: a national Swedish adoption study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:690–697. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Heckman JJ, Cameron JL, Shonkoff JP. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10155–10162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600888103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen DE, Leventhal T, Dahinten VS, McIntosh CN. Neighborhood disadvantage: pathways of effects for young children. Child Dev. 2008;79:156–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz-Wirtz N. Cumulative effects of growing up in separate and unequal neighborhoods on racial disparities in self-rated health in early adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 2016a;57:453–470. doi: 10.1177/0022146516671568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz-Wirtz N. A discrete-time analysis of the effects of more prolonged exposure to neighborhood poverty on the risk of smoking initiation by age 25. Soc Sci Med. 2016b;148:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz-Wirtz N. Temporal effects of child and adolescent exposure to neighborhood disadvantage on Black/White disparities in young adult obesity. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2016c;58:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Is neighborhood context differently related to externalizing problems and delinquency for girls compared with boys? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2004;7:109–122. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030288.01347.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz J, Page ME, Solon G. Are point-in-time measures of neighborhood characteristics useful proxies for children’s long-run neighborhood environment? Economics Letters. 2003;79:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lander F, Rasmussen K, Mortensen JT. Social inequalities in childhood are predictors of unemployment in early adulthood. Dan Med J. 2012;59:A4394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh D, Gill A. Labor market returns to community college: Evidence from returning adults. Journal of Human Resources. 1997;32:334–353. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupere V. Moving to Opportunity: Does long-term exposure to ‘low-poverty’ neighborhoods make a difference for adolescents? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, Maciver S, Sooman A. Area, class and health: should we be focusing on places or people? Journal of Social Policy. 1993;22:213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Faden VB, Zucker RA, Spear LP. Underage drinking: a developmental framework. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 4):S235–251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur A. From jobs to careers: How California community college credentials pay off for welfare participants. California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office for the Center for Law & Social Policy; Sacramento, CA. 2004. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon VV, Sartor CE, Pommer NE, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PA, Heath AC. Age at trauma exposure and PTSD risk in young adult women. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:811–814. doi: 10.1002/jts.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ. Handbook of the Life Course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide, Version 7. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Burt KB, Masten AS. Testing a dual cascade model linking competence and symptoms over 20 years from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:90–102. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odlaug BL, Gual A, DeCourcy J, Perry R, Pike J, Heron L, Rehm J. Alcohol dependence, co-occurring conditions and attributable burden. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:201–209. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Henderson CR, Jr, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Pettitt L, Sidora K, Morris P, Powers J. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1238–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BP. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens A. Neighborhoods and schools as competing and reinforcing contexts for educational attainment. Sociology of Education. 2010;83:287–311. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of male twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:34–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Dawson D, Frick U, Gmel G, Roerecke M, Shield KD, Grant B. Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research. 2014;38:1068–1077. doi: 10.1111/acer.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Imtiaz S. A narrative review of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2016;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Taylor B, Room R. Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:503–513. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendón M. Drop Out and ‘Disconnected’ Young Adults: Examining the Impact of Neighborhood and School Contexts. Urban Review. 2014;46:169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Robertson DL, Mann EA. Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low-income children in public schools. JAMA. 2001;285:2339–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Tellegen A. Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development. 2004;75:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariaslan A, Langstrom N, D’Onofrio B, Hallqvist J, Franck J, Lichtenstein P. The impact of neighbourhood deprivation on adolescent violent criminality and substance misuse: a longitudinal, quasi-experimental study of the total Swedish population. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1057–1066. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders J, Drukker M, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, van Os J, Nicolson NA. Neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage and behavioural problems from late childhood into early adolescence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:699–703. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellstrom E, O’Campo P, Muntaner C, Arnoldsson G, Hjern A. Hospital admissions of young persons for illicit drug use or abuse: does neighborhood of residence matter? Health Place. 2011;17:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick SL, Shaw DS, Hyde LW. Precursors of adolescent substance use from early childhood and early adolescence: testing a developmental cascade model. Dev Psychopathol. 2014;26:125–140. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Cumulative adversity in childhood and emergent risk factors for long-term health. J Pediatr. 2014;164:631–638. e631–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJL, Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382:1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]