Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Case fatality after total anterior circulation stroke is high. Our objective was to describe the experiences and needs of patients and caregivers, and to explore whether, and how, palliative care should be integrated into stroke care.

METHODS:

From 3 stroke services in Scotland, we recruited a purposive sample of people with total anterior circulation stroke, and conducted serial, qualitative interviews with them and their informal and professional caregivers at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year. Interviews were transcribed for thematic and narrative analysis. The Palliative Care Outcome Scale, EuroQol-5D-5L and Caregiver Strain Index questionnaires were completed after interviews. We also conducted a data linkage study of all patients with anterior circulation stroke admitted to the 3 services over 6 months, which included case fatality, place of death and readmissions.

RESULTS:

Data linkage (n = 219) showed that 57% of patients with total anterior circulation stroke died within 6 months. The questionnaires recorded that the patients experienced immediate and persistent emotional distress and poor quality of life. We conducted 99 interviews with 34 patients and their informal and professional careers. We identified several major themes. Patients and caregivers faced death or a life not worth living. Those who survived felt grief for a former life. Professionals focused on physical rehabilitation rather than preparation for death or limited recovery. Future planning was challenging. “Palliative care” had connotations of treatment withdrawal and imminent death.

INTERPRETATION:

Major stroke brings likelihood of death but little preparation. Realistic planning with patients and informal caregivers should be offered, raising the possibility of death or survival with disability. Practising the principles of palliative care is needed, but the term “palliative care” should be avoided or reframed.

Stroke is the second leading global cause of death, accounting for 11% of deaths worldwide.1,2 Five-year survival is similar to all cancers combined and heart failure.3 Prognosis is particularly poor for patients with total anterior circulation syndrome strokes; i.e., the “full house” of unilateral motor or sensory loss with cortical symptoms (e.g., aphasia or inattention) and homonymous hemianopia.4 A physical trajectory for patients with severe stroke has been proposed of sudden decline in functional status at stroke onset, and ending in death or survival with long-term disability.5

Palliative care seeks to support people to live well with deteriorating health until they die and improves outcomes when introduced early alongside disease-modifying treatment.6,7 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that holistic care for people with any life-threatening illness should include the key principles of palliative care.8 Patients with severe stroke and their informal caregivers (the term “informal caregiver” is used to include family or unpaid caregivers) stand to benefit when their physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual and practical needs are anticipated and addressed.9–11 Cohort studies and qualitative research in patients with major stroke have identified difficulties with symptom management, communication, family support and proxy decision-making among patients dying with acute stroke.12–15 However, there is insufficient detail about the immediate and long-term psychological, emotional and spiritual needs of stroke survivors and their informal caregivers to understand whether, and how, palliative care should be integrated into stroke care. A mixed-methods approach was considered the most appropriate method to explore these dynamic complex issues.16

Our objective was to understand patients and informal and professional caregivers’ experiences, concerns and priorities in the 12 months after total anterior circulation syndrome stroke, and to identify the potential role of palliative care within stroke care, both in hospital and the community.

Methods

Design

To explore patterns of death, we employed a mixed-methods approach using individual in-depth interviews with patients, informal caregivers and health or social care professionals, or joint interviews with patient and caregiver; questionnaires, if patients and caregivers were able to complete them; and a data linkage study of all patients with total anterior circulation syndrome admitted to the 3 participating stroke units in central Scotland (2 of which were in academic centres). We specifically used serial qualitative multiperspective interviews, as this is a robust method for understanding evolving and complex processes.17 We used questionnaires to allow a numeric comparison using standardized measures across the interviewees, and to observe how the questionnaires might perform serially in a future trial.

Data generation

Qualitative component

The qualitative study included patients with total anterior circulation syndrome with a modified Rankin score of 4 or 5. To capture a range of experiences, we aimed to recruit a minimum of 10 patients in each of the dichotomous groups of age (70 yr or older, or younger than 70); sex; artificial or oral feeding; right and left hemisphere stroke; substantial comorbidity or not; and at least 5 people who were expected to go home. In total, we aimed to recruit about 30 patients because this was expected to achieve saturation, based on our previous experience of serial qualitative interviews in other end-of-life patient groups.17

Patients admitted to the 3 stroke units, or their legally recognized representative or next of kin, were identified and approached by a clinician or a Scottish Stroke Research Network nurse working in a stroke unit in 3 Scottish Health Boards between June 2014 and January 2015. We used a recruitment grid to ensure we recruited the required diversity of participants. We obtained consent from those patients with capacity (using aphasia-friendly materials if needed). Proxy consent was obtained for patients with incapacity. A researcher then contacted participants. See Box 1 for special considerations we adopted for people deemed not to have capacity.

Box 1: Special considerations in dealing with people with incapacity.

Where there was not an Adults with Incapacity Order, patients’ capacity to consent was established by the clinical team (i.e., not the interviewers).

For patients with incapacity, relatives gave proxy consent and acted as proxy information-givers.

We developed aphasia-friendly information sheets about the study.

The interviewers received training in communicating with people who have aphasia.

We used tailored information sheets for different participant groups (e.g., patients with or without aphasia, relatives).

Written informed consent was obtained or reaffirmed before interviews.

Patients deemed by the clinical team during the follow-up year as having lost the capacity to consent were not interviewed again, but their relatives continued in the study.

Two experienced female qualitative researchers (nurse researcher and senior social scientist) undertook the interviews with stroke survivors or their informal caregiver or relative at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year.18 At each time point, participants nominated a key health or social care professional for interview. Patient and relative interviews took place in the hospital ward or in their homes or residential care. Professionals were interviewed at their workplace or by telephone. The interviews took a narrative approach using topic guides that included, for instance, asking professionals how they perceived “palliative care.” The researchers did not directly ask patients and caregivers about end-of-life care, death or dying, but if the participants raised the topic, this was explored using their terms; the researchers asked whether the participants had heard of palliative care, and what they understood it to mean. Interviews lasted 20 to 90 minutes, were digitally recorded and fully transcribed with field notes.19

Two lay advisory groups — one from a support group for patients with stroke and their informal caregivers, and another from a group specifically for people with speech loss — regularly discussed emerging findings. Four end-of-study focus groups (n = 36) of informal caregivers, stroke clinicians, general practitioners, geriatricians, palliative care specialists, allied health professionals, care home managers and policy-makers considered emerging recommendations.

Questionnaires

After each interview, we mailed the EuroQol-5D-5L (quality of life) and the Patient Outcome Score (multidimensional needs) to patients and the Carer Strain Index (caregiver well-being) to caregivers.20–22

Data linkage

We obtained Scottish Stroke Care Audit data for all patients with total anterior circulation syndrome admitted to the 3 stroke units during the 6 months of recruitment to the qualitative study. We linked these data with hospital and National Register for Scotland data for the year after the index stroke, to describe temporal patterns of death.

Data analysis

The qualitative analysis was iterative and ongoing alongside further data generation. It was guided by the research questions, key theoretical concepts in the literature and assimilated themes arising from the data. We performed thematic and narrative analysis and used a constructivist and interpretivist framework.19,23 Principles of grounded theory were used in the sense that data analysis was iterative and guided by emerging themes as well as by the research questions.24 We were thus open to new ideas or themes and were also able to situate our findings within the existing theoretical landscape. The interviews with individual patients, caregivers and professionals were initially coded separately. Then, each set of individual patient’s and caregiver’s transcripts was analyzed over time to identify dynamic changes, generating 29 individual case studies. Next, we analyzed patient transcripts together to gather patients’ perceptions; informal caregiver transcripts to examine the caregivers’ perspectives; and health care professional transcripts to gain their views. Finally, we analyzed all the transcripts (patients’, caregivers’ and professionals’) from each of the 3 time points together to look at issues specific to each point. The insights were integrated with the assistance of NVivo 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd.) to show common themes and divergent perspectives. We then traced themes across the 3 data sets to give an in-depth multiperspective picture of experiences and outcomes.25

We triangulated between methods and between the views of the various participant groups to enrich our understanding of the data, employing mainly the mixed-methods matrix approach, which integrates both qualitative and quantitative data for each participant at the analysis stage of the study.25 We scrutinized deviant cases, or accounts of experiences that differed from those commonly reported, to refine our comprehension of emerging narratives.26 Early in the study, the interviewers (MK, EC) reviewed each other’s initial interview transcripts to ensure similarity of interviewing approach. MK coded all the transcripts and met frequently with a principal investigator (SAM) to discuss the emerging findings. The evolving analysis was reviewed by the investigator group at quarterly meetings. We established an audit trail using field notes, recruitment logs, records of meetings and analytical discussions. We used multiple data collection sites to enhance the transferability of our findings and undertook data linkage to enable a description of the wider study context, in terms of outcomes for a cohort of patients with total anterior circulation syndrome.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (reference 14/SS/0060) and the Caldicott Guardian for the data linkage study. The local NHS Research & Development services conferred governance approval.

Results

Two hundred and nineteen patients with total anterior circulation syndrome (185 ischemic stroke [85%]; 33 hemorrhagic stroke [15%]) were admitted to the 3 participating stroke units during the study recruitment period. Six-month case fatality was 57% (125 deaths). One-year case fatality was 60% (132 deaths); of these deaths, 88 (67%) occurred during the first 4 weeks.

We recruited 34 patients to the qualitative study (Table 1) and performed 99 qualitative interviews (Table 2) over the first year after stroke. Between half and two-thirds of questionnaires were returned; these showed anxiety of family or friends, low self-worth, lack of information, difficulty sharing feelings and emotional distress (Table 3). See Box 2 for specific details according to specific data sources, including data linkage. We present the integrated findings from the 3 methods.

Table 1:

Profile of participants in the qualitative study at recruitment

| Patient characteristics | No. of participants* n = 34 |

|---|---|

| Mean age, yr (range) | 75 (20–98) |

| Sex, female | 20 |

| Stroke in dominant hemisphere | 20 |

| First stroke | 29 |

| Recurrent stroke | 5 |

| Modified Rankin score (0–6)27† | score 5: 22; score 4: 12 |

| Tube fed (nasogastric or gastrostomy) | 18 |

| Has Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation Order | 14 |

| Has incapacity certificate | 19 |

| Substantial speech loss (aphasia) | 24 |

| Permanent indwelling urinary catheter (urinary incontinence) | 20 |

| Has informal caregiver at home | 18 |

| Residential area | urban: 25; rural: 4; semi-urban:5 |

| Has hypertension | 18 |

| Has major comorbidities, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, renal failure, dementia | 15 patients: no comorbidities; 12: 1; 5: 3; 1: 3 |

| Median number of medicines prescribed at the time of recruitment | 5 (range 0–9) |

Except where indicated otherwise.

Modified Rankin scores: 4 = moderately severe disability; unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance; 5 = severe disability; bedridden, incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention.

Table 2:

Completed interviews at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months

| Participants* | No. of interviews | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 wk | 6 mo | 12 mo | Total | |

| Patient alone | 6 | 5 | 5 | 16 |

| Patient and caregiver | 5 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Informal caregiver alone | 21 | 5 | 4 | 30 |

| Bereavement interviews with informal caregiver | 2 | 7 | 0 | 9 |

| Health and social care professionals† | 16 | 12 | 5 | 33 |

| Total | 50 | 33 | 16 | 99 |

Thirty-four index patients were recruited. Five died before 6-wk interview. Between the first interview at 6 wk and the second at 6 mo, 11 people died, 1 person moved away, 1 person withdrew for personal reasons, and 7 were lost to follow-up because they were very unwell and had several readmissions. This gave us 9 participants for round 2 interviews at 6 mo. One more person died between interview 2 and the final interview at 12 mo, leaving 8 participants for the final interviews.

Twelve hospital doctors and nurses, 9 physiotherapists, 2 speech and language therapists, 2 community nurses, 3 home care workers, 2 care home managers and 3 general practitioners.

Table 3:

Quantitative data collected at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months

| Questionnaires | 6 wk | 6 mo | 1 yr |

|---|---|---|---|

| POS* | |||

| Questionnaires sent | 21 | 10 | 6 |

| Questionnaires returned | 13 | 5 | 4 |

| Return rate, % | 62 | 50 | 67 |

| POS score (median) | 15 | 8 | 10 |

| POS score (range) | 4–25 | 5–21 | 5–26 |

| EQ-5D† | |||

| Questionnaires sent | 18 | 9 | 6 |

| Questionnaires returned | 12 | 5 | 4 |

| Return rate, % | 67 | 56 | 67 |

| EQ-5D score (median) | 19 | 11 | 18 |

| EQ-5D score (range) | 5–23 | 5–18 | 13–22 |

| EQ-5D VAS score (median)‡ | 50 | 72 | 45 |

| EQ-5D VAS score (range) | 15–90 | 60–90 | 30–75 |

| CSI§ | |||

| Questionnaires sent | 27 | 8 | 5 |

| Questionnaires returned | 14 | 4 | 3 |

| Return rate, % | 52 | 50 | 60 |

| CSI score (median) | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| CSI score (range) | 3–11 | 4–8 | 3–8 |

Note: CSI = Carer Strain Index, POS = Palliative Care Outcome scale.

POS ranges from 0 to 4 in 10 dimensions of need. Each of these dimensions is monitored individually over time and not usually summated.

EQ5D range 5–25 where 5 represents no problems.

EQ5D VAS range 0–100 where 0 is worst health.

CSI score range 0–12 where 0 represents no caregiver strain. A CSI score of 7 or more indicates a high level of stress.

Box 2: Summary of the findings relating to the qualitative interviews, the questionnaire results and the data linkage findings.

Qualitative interviews: We approached 39 eligible people and recruited 34 participants. Five died or withdrew before the first interview at 6 weeks, leaving 29 participants, who represented a range of age, gender, social situations, dominant or nondominant stroke, and social circumstances. They ranged from a previously healthy 19-year-old to many older people with substantial comorbidities (Table 1). We conducted 99 interviews in total. Many informal caregivers were interviewed alone because many patients lacked capacity to participate or had difficulty in communicating well as a result of speech loss. Eleven patients died between the first and second interview. By 12 months, n = 19 (59%) had died (Table 2).

Questionnaires: A total of 110 questionnaires were given or posted out to patients and caregivers across the 3 time points. In total, 64 were returned, a response rate varying from 50% to 67% (Table 3). The Palliative Care Outcome Scale at 6 weeks identified anxiety of family or friends, low self-worth, lack of information and difficulty sharing feelings. Anxiety remained prominent for both patients and informal caregivers at 6 and 12 months. The EuroQol-5D-5L identified problems with mobility, self-care and doing usual activities. The Carer Strain Index had average scores of 7, indicating high levels of distress among caregivers throughout the 12 months.

Data linkage: One-year follow-up (for hospital admissions and death) analyzed service use and outcomes for all 219 patients with total anterior circulation stroke. This type of stroke affected mainly older people (29% aged 70–79 yr [n = 64]; 49% older than 80 yr [n = 107]), and 61% (n = 134) were women. One-year mortality was 60% (132 deaths). Although 61% died of cerebrovascular disease, a further 25% died from heart disease. Most had an ischemic stroke (85%, n = 185), but patients with hemorrhagic stroke (15%, n = 33) had a poor outcome with a median time to death of just 6 days. Early mortality was high overall, with 67% (n = 88) of deaths occurring in the first 4 weeks and only a 14% discharge (n = 18) rate at that point. By 6 months, 57% (n = 126) of the original cohort had died. The remaining stroke survivors had a better prognosis, with 5% (n = 5) dying by 12 months. There were 27 hospital readmissions, with all but 2 occurring in the first 6 months. People who survived to 6 months were living in the community with long-term disability and not using hospital services. However, the high early death rate meant that 92% (n = 121) of deaths occurred in hospital.

Experiences and key concerns of patients, informal caregivers and professionals

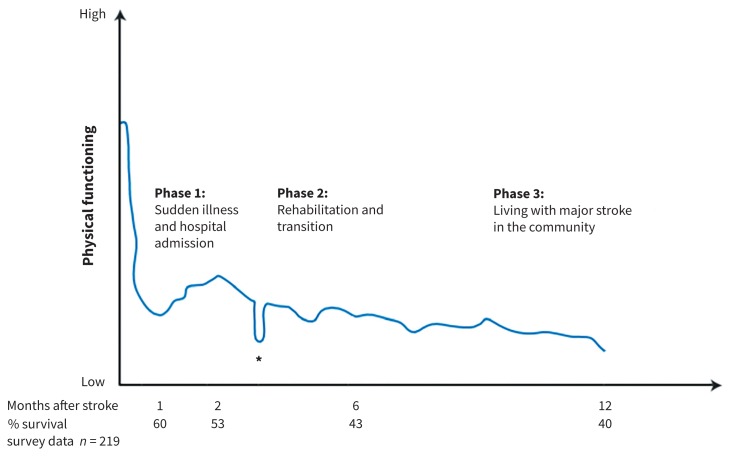

A typical trajectory of physical decline with people with total anterior circulation syndrome is illustrated in Figure 1 based on the findings generated from our mixed methods. This extends and enriches Creutzfeldt’s proposal for a “fourth trajectory.”5 It visualizes how the typical physical functioning of patients who survived the stroke tended to progress during the following 12 months. The percentages of patients surviving at 1, 2, 6 and 12 months are also shown. Key quotations are in Box 3.

Figure 1:

Archetypal physical trajectory of decline for people with total anterior circulation stroke. *At some time in the first 12 months, most people have 1 or more episodes of acute functional decline owing to a comorbidity such as a chest infection.

Box 3: Quotations.

Phase 1

Q1: “I felt helplessness; I felt as if my mother was dead but yet she wasn’t dead. I felt guilty because I had phoned the ambulance and I thought perhaps I shouldn’t have phoned the ambulance and then she would have died, and perhaps that would have been better” (daughter — first interview).

Q2: “It just struck one night. Unusual for me, I fell out of bed. I don’t think I’ve ever done that before. I remember lying there and thinking, ‘Now if I don’t get up on that bed, I could die here’” (patient — first interview).

Q3: “We kept getting conflicting stories, so sometimes one would say one thing and then the other one would say another and that was the only thing we were a bit confused about” (daughter — first interview).

Q4: “We need her to really try hard so we need to keep her thinking it’s going to get better, otherwise she won’t commit and then you won’t get the same outcome. You’re very positive even though you think long term it might not happen” (physiotherapist — first interview).

Q5: “We had a meeting with them when they said that they’d taken Dad as far as he could go and they’d be transferring him to the rehab unit … When we got there, we started to discover things we felt should have been told at the very, very start of the whole process, and it would have created a completely different atmosphere in the way we handled the whole situation and progressed through it” (daughter and son-in-law — bereavement interview).

Q6: “I look back over the course of [X’s] admission; I will have sat down with that family for hours and hours in total, and that’s all time that I’m, you know, it’s very important and I would do that plus more if I could, but all of these things take time, and to be able to have the time, you need that resource, but you also need the skill” (hospital doctor — first interview).

Phase 2

Q7: “I remember when we came home from that visit, [my husband] said to me, ‘I wish my mum had just passed away when she took her stroke at first.’ I said, ‘I didn’t want to say that to you, but I’ve been thinking that all the time.’ It’s so sad when someone has to suffer like that” (daughter-in-law — bereavement interview).

Q8: “And my point is, yes, you can bring people back from these severe strokes, but I don’t feel that the infrastructure is there to give them a reasonable quality of life. It’s like bringing someone back from a major stroke and then putting them in solitary confinement …” (daughter — bereavement interview).

Q9: “I remember saying to my daughter, ‘I feel so disabled, and that upsets me, because what does the future hold at this moment — nothing worthwhile looking forward to.’ So then I got told off and she said, ‘What about the man who comes in the afternoon and is in a wheelchair?’ I said, ‘I know. I mustn’t be like that, but it is how I feel’” (patient — second interview).

Q10: “I think if you had, like, say, a heart attack or cancer, there would be something there to try and, you know, this is our plan, this is what we’re going to do. But you can’t plan ahead because everything’s up in the air; and it’s like we had a meeting last week with all the doctors and everybody and the team, and they’re great, I mean, they sit and explain everything to you, but you’re still coming away with nothing. It’s just all talk and there’s nothing because there’s basically nothing they can say because it’s the brain, so we are just now, is limbo” (daughters — first interview).

Q11: “It’s all to do with funding and care availability … we just have to wait. Then there’s the possibility of boarding, which is always a shame but it can’t be avoided, unfortunately, when we need the bed for someone else” (hospital-based physiotherapist — first interview).

Phase 3

Q12: “You get to a level with some people and it’s when do we stop? Because we’ve kind of plateaued, and then it’s their expectations of the services which are available, but also it’s having that difficult conversation of saying you’re not going to manage the stairs again or you’re not going to be able to get out on your own, you’re always going to have to have somebody with you. And then I think people hate us for saying it” (community physiotherapist — third interview).

Q13: “Well, I can see things here that are familiar, but I knew whenever I was in it, I wasn’t home … My husband keeps saying I’ve got to accept it. ‘This is your home and you’re in it.’ But I can’t” (patient — second interview).

Q14: “I’m hoping that I can … make enough money to hopefully get him out of here and get him cared for like in a house that I own, but … But I don’t know if I’ll be able to do it as fast as I know I need to …” (son — third interview).

Q15: “I have nothing but praise for the care home. They let us put up his pictures and make it as much like his home as we could … in fact, the manageress went to assess Dad and her expression to me was that she was heartbroken to see him in that situation [in hospital], and she says, ‘whatever happens, we have to get him out of there’” (daughter — bereavement interview).

Q16: “If we’d had honesty from the start, rather than the end of the process, we would have done things differently … rather than pushing him, pushing him for something that was never going to happen” (daughter — bereavement interview).

Q17: “Doctor X, she was a very nice person, but she really took me unawares when she said, ‘What do you think of your mother-in-law’s quality of life?’ And she said, ‘We could stop feeding her,’ and I thought no, I couldn’t cope with that. It’s not for us to decide how long she’s going to live. I was really, really upset. I said, ‘You can’t do that,’ and she left it at that” (daughter-in-law — bereavement interview).

Use of the term “palliative care”

Q18: “I wouldn’t say she was a palliative patient just yet, in terms of helping her to die peacefully or pain free or anything like that. So she’s going on to the nursing home, so I wouldn’t consider her a palliative patient just now” (stroke unit nurse — first interview).

Q19: “I suppose it depends what we mean by ‘palliative care,’ but it’s, you know, no more needles and no more drips and no more antibiotics …” (hospital doctor — first interview).

Q20: “I try to emphasize that just because we’re shifting the approach to palliation, it’s still really hard to predict what happens from here, and I usually try and say that, you know, some people deteriorate very quickly, some people deteriorate very slowly, some people stabilize and don’t deteriorate particularly” (hospital doctor — first interview).

Q21: “Much as I’d love to say if only we had access to a communication team from palliative care, that would solve all our problems, it clearly wouldn’t. It’s about upskilling everybody and allowing us all to have the skills and time for communicating well” (hospital doctor — first interview).

Q22: “Maybe ask a question in the event of you becoming … would you choose to let nature take its course, have you spoken to your next of kin about what you would like? Something like that, so it was in your medical records. Like organ donation. I think you need to write it down” (bereaved carer — bereavement interview).

Q23: “One of the staff said, ‘He’s not going to need a wheelchair because he’s obviously now palliative care,’ which I found very upsetting, that you go from being a priority to being an inconvenience” (daughter — bereavement interview).

Q24: “I sometimes tell the team to scrap the word ‘palliative’ … It does give the wrong focus … if they’re not dying” (hospital doctor — first interview).

Phase 1: Sudden illness and acute hospital admission

The sudden unexpected event of major stroke came as a major life crisis. Its life-threatening but unpredictable course posed huge challenges for patients, informal caregivers and professionals. Although the possibility of dying was clear to all involved, it was rarely voiced. Family members were unsure whether they were “doing the right thing” for patients (Q1). Participants faced complex care-planning decisions about resuscitation and feeding interventions (Q2).

Communication with informal caregivers and among staff was often challenging, as circumstances could change rapidly and many patients had lost capacity. Patients and caregivers expressed “dual narratives”; i.e., the narrative of a good recovery competing with a more realistic account of disability or death. Everyone had thoughts about death, but most patients felt unable to raise these with professionals. When the stroke first occurred, professionals aimed at life-saving treatment unless the patient was clearly dying, so professionals and patients expressed hope for a good recovery, even if death had been mentioned as a possible outcome. This sometimes confused caregivers (Q3). Staff confessed to being overoptimistic in order to motivate people and encourage participation in physical rehabilitation (Q4).

Many patients and informal caregivers would have welcomed more support in making decisions and in planning for the future from day 1. The focus was on active rehabilitation, recovery, motivation and hope, with much less discussion and preparation for limited recovery. Many professionals gave time and listened and communicated well, but future planning was less evident (Q5 and Q6).

Phase 2: Rehabilitation and transition to the community

Emotional needs and ability to adapt to a radically altered life varied. Some said it was difficult to see life as “a life worth living” (Q7).

As in the earlier phase, maintaining a sense of dignity and personhood was central. In rehabilitation wards, people felt trapped, as they could not be discharged home until their physical abilities improved. Some caregivers and patients began to suggest that it would have been better if the patient had died, rather than living with severe disability. The sort of life deemed “unacceptable” was subjective: some accepted their disability; others with a better physical recovery felt discontented and grieved for their former life (Q8 and Q9). These caregivers felt that there was less forward planning than in other illnesses (Q10).

Most patients wished to return home initially, but later realized this was complex, being compounded by pressure on hospital and care home beds (Q11).

Phase 3: Living with major stroke in the community

Many people, especially those with aphasia and cognitive impairments, found difficulties in accessing services and equipment. Some felt abandoned and experienced loss of hope and meaning. This was exacerbated once professionals assessed patients as having reached their “plateau,” when many services were withdrawn (Q12). Those who returned to living at home had to adjust to a very different way of life and a home disrupted by hoists, commodes and boxes of medication (Q13).

Most patients and their informal caregivers came to appreciate the advantages a good care home offered when they could not manage at home. However, one family member still wanted to take their parent home (Q14). For informal caregivers, a nearby care home with friendly staff who inspired trust was important. Many care homes provided equipment and care that was difficult to achieve at home (Q15). Many informal caregivers felt that future care planning for both recovery and deterioration would have been helpful (Q16).

A few people died in care homes, where care home staff generally managed discussions and decisions sensitively. However, one participant was shocked when the general practitioner in the care home approached her as she visited her relative and began an end-of-life conversation without any warning (Q17).

Use of the term “palliative care”

Some staff viewed the term “palliative care” as something negative, applicable only to someone who was clearly dying (Q18 and Q19).

Professionals actively sought to offer holistic care to patients and caregivers, but also struggled with the words “palliative care.” Barriers to its use included prognostic uncertainty, although one physician understood that this may remain, even after introducing a palliative approach (Q20). Professionals spoke about the need for everyone involved in patient care to have the time and ability to communicate effectively, with referrals being made to specialist palliative care only when required (Q21).

One bereaved relative suggested following a routine approach to document preferences (Q22); using the word insensitively with patients could upset them (Q23). One hospital doctor suggested that the word may best be avoided (Q24).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of 219 persons with total anterior circulation stroke, we found that that 57% died within 6 months. Over this time, the professionals focused on active physical rehabilitation, recovery, motivation and hope, and took less account of psychological, social and existential needs. However, care planning was difficult because of uncertain prognosis, variable and changing understandings, expectations and coping strategies.28 Patients and their informal caregivers faced sudden complex decisions, anxiety, distressing symptoms and the likelihood of death. Transition to home or to a care home brought feelings of abandonment. Some experienced a lack of hope and meaning, and grief for a former life. The term “palliative care” was equated with “last-days-of-life” care by health care professionals, patients and family.

Previous studies have identified high case fatality after severe stroke, multiple long-term physical problems, substantial emotional distress, prognostic uncertainty and a sense of abandonment after discharge from hospital.10,29,30 Our study confirms and adds richness to these findings, and contributes several new insights. First, staff focused on active physical rehabilitation, recovery, motivation and hope, while patients and caregivers felt that they needed more preparation for, and discussion of, the possibility of death and living with severe disability. The questionnaires documented poor quality of life and multidimensional needs, and highlighted anxiety and caregiver distress throughout. Patients described a degree of suffering consistent with considerable unmet palliative care needs. Second, for those patients who survived, there was grief among both patients and family for the loss of their previous life, identity and roles; this could be considered as an evolving bereavement process, with some patients and family wondering if death would have been preferable to survival with disability. This evolving process has also been reported in severe head injury and dementia.31,32

Third, patients and professionals found the term “palliative care” difficult to use, as it was equated with “end-of-life” care and withdrawal of treatment. This is still true even in people with cancer.33 This contrasts with the WHO’s definition and recent affirmation of the term as active treatment to prevent distress, starting from diagnosis of a life-threatening illness (Box 4).

Box 4: Definition and historical development of palliative care.

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients who are facing life-threatening illness, as well as that of their informal caregivers, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and assessment and treatment of physical, psychosocial and spiritual problems.8

Forty years ago, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined palliative care as an approach to care. It quickly developed into a specialty, and most patients and clinicians now consider it to be a specialty concerned with people who are imminently dying, as we found in this study. However, in 2014, palliative care was reaffirmed as an approach, when the WHO resolved that it should be routinely integrated with disease-modifying care to improve patient and informal caregiver experience and outcomes. It should be integrated when a disease is “life-threatening,” rather than when the patient is imminently dying. It encompasses support to live as well as possible with deteriorating health as well as bereavement care.

A realistic model of care would be to prepare for survival, decline or death, balancing “hoping for the best” with “preparing for the worst.”5 This palliative approach more often occurs for patients with progressive cancer and increasingly for people with nonmalignant conditions such as heart, lung and renal failure and frailty.34 Shared decision-making and individualized care is crucial.30,35–37 Staff must be supported and trained in talking openly and honestly about the possibility of death or survival with severe disability, particularly in the acute setting, where the majority of deaths occur. Models of bereavement support might help professionals to facilitate both the more traditional restoration-oriented approaches to rehabilitation and loss-oriented rehabilitation that allows people to express and work through devastating life changes.38 The principles of palliative care should be embedded within stroke services, but the term “palliative care” should currently be avoided or reframed because of the implications of abandonment rather than a positive approach to care.33,39 Some specific recommendations are offered in Box 5.

Box 5: Suggestions to improve stroke care.

Acute hospital

Stroke care should encompass the principles of palliative care from admission through rehabilitation, encompassing physical, social, psychological and existential aspects.

There should be person-centred, shared decision-making supported by effective patient-oriented information about treatment options and outcomes.

Staff should be given support and training in key principles of palliative care, as well as support to talk openly with patients and caregivers about the possibility of dying.

Rehabilitation ward

All dimensions of need and what matters to the patient and caregiver should be reviewed frequently.

Anxieties and loss of meaning, purpose and value in life, and grief for former life should be addressed, with openness about discussing such issues.

There should be liaison with the primary care team to plan ongoing care.

Primary care

A care plan should be started or updated and communicated, in liaison with social work.

Informal caregivers should be supported, and use of local resources facilitated, including for grief in bereavement.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths included the mixed-methods design, with serial multiperspective interviews dynamically integrating data from patients, informal and professional caregivers, and rigorous analysis with service user involvement through the 2 lay advisory groups and the 4 end-of-study focus groups to aid interpretation. For instance, the service user involvement explained the challenges of accessing support when people have aphasia, and the experience of discharge back to the community after a long admission. To promote credibility and generalizability and transferability of the data, we sought to find exceptions, then used triangulation ( multiple methods of data collection, data sources, researchers or theories), to obtain a high level of concordance in category development. We adopted a relatively large longitudinal multisite interview study to enable prolonged engagement in the field and used a varied sample to ensure that a range of perspectives were explored.

Limitations included the following: we recruited patients from Scotland only; some patients participated in only 1 interview because of loss to follow-up or death (although we performed several bereavement interviews with informal caregivers), and the sample comprised all white British people. No formal training in palliative care had occurred in any of the stroke units, although some online learning was available; this is likely to be the case in most facilities internationally.

Conclusion

In this study of patients experiencing major stroke, death occurred in more than half in the first 6 months. Care of those who survived the acute event focused on physical rehabilitation and did not address persistent disability, loss and death. Realistic planning with patients and informal caregivers should include these factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all patients, informal and professional caregivers, and clinical colleagues who identified participants, and to members of the lay advisory groups for their involvement throughout the study. They thank the Scottish Stroke Research Network for support with patient recruitment, and Sian Nowell, National Service Scotland, for conducting the data linkage. Heather Goodare, who cares for her husband with a stroke, commented on an earlier draft of this article.

See related article at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.170956

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Gillian Mead, Marilyn Kendall, Eileen Cowey, Mark Barber, Christine McAlpine, David Stott and Scott Murray conceived the study and contributed to its design. Gillian Mead and Marilyn Kendall prepared the application for ethics approval and the patient information leaflets. Marilyn Kendall led the study and undertook data collection and initial analysis with Eileen Cowey. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data and reviewing the early and final drafts. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by the Chief Scientist Office, grant number CZH/4/1033. The funder played no part in undertaking the research apart from funding it.

Data sharing: Further data are available from Gillian Mead.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association [published erratums in Circulation 2015;131:e535; Circulation 2016;133:e417]. Circulation 2015;131:e29–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deaths from cardiovascular diseases: implications for end of life care in England. Bristol (UK): National End of Life Care Intelligence Network; 2013. Available: www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/deaths_from_cardiovascular_diseases (accessed 2017 Feb. 6). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askoxylakis V, Thieke C, Pleger ST, et al. Long-term survival of cancer patients compared to heart failure and stroke: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 2010;10:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, et al. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet 1991;337:1521–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creutzfeldt CJ, Longstreth WT, Holloway RG. Predicting decline and survival in severe acute brain injury: the fourth trajectory. BMJ 2015;351:h3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tassinari D, Drudi F, Monterubbianesi MC, et al. Early palliative care in advanced oncologic and non-oncologic chronic diseases: a systematic review of literature. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2016;11:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Definition of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 2017 Sept. 6). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addington-Hall J, Lay M, Altmann D, et al. Symptom control, communication with health professionals, and hospital care of stroke patients in the last year of life as reported by surviving family, friends, and officials. Stroke 1995;26:2242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burton CR, Payne S, Addington-Hall J, et al. The palliative care needs of acute stroke patients: a prospective study of hospital admissions. Age Ageing 2010;39:554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson H, Milberg A, Hjelm K, et al. End of life care for patients dying of stroke: a comparative registry study of stroke and cancer. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso A, Ebert AD, Dörr D, et al. End-of-life decisions in acute stroke patients: an observational cohort study. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne S, Burton C, Addington-Hall J, et al. End-of-life issues in acute stroke care: a qualitative study of the experiences and preferences of patients and families. Palliat Med 2010;24:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer ME, Depla M, Wojtkowiak J, et al. Life-and-death decision-making in the acute phase after a severe stroke: Interviews with relatives. Palliat Med 2015;29:451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowey E, Smith LN, Stott DJ, et al. Impact of a clinical pathway on end-of-life care following stroke: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med 2015;29:249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowan M, Huston P. Qualitative research articles: information for authors and peer reviewers. CMAJ 1997;157:1442–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray SA, Kendall M, Carduff E, et al. Use of serial qualitative interviews to understand patients’ evolving experiences and needs. BMJ 2009;339:b3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendall M, Murray SA, Carduff E, et al. Use of multiperspective qualitative interviews to understand patients’ and carers’ beliefs, experiences, and needs. BMJ 2009;339:b4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charon R. Narrative medicine: honoring the stories of illness. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palliative Care Outcome Scale (POS) [main page]. London (UK): Cicely Saunders Institute; 2012. Available: http://pos-pal.org/ (accessed 2017 May 24). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson BC. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol 1983;38:344–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the human sciences. London (UK): Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryant A, Charmaz K. The SAGE handbook of grounded theory. London (UK), Thousand Oaks (CA), New Delhi (India), Singapore: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010;341:c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziebland S, McPherson A. Making sense of qualitative data analysis: an introduction with illustrations from DIPEx (personal experiences of health and illness). Med Educ 2006;40:405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruno A, Shah N, Lin C, et al. Improving modified Rankin Scale assessment with a simplified questionnaire. Stroke 2010;41:1048–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Palliative care in chronic illnesses: we need to move from prognostic paralysis to active total care. BMJ 2005;330:611–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holloway RG, Benesch CG, Burgin WS, et al. Prognosis and decision making in severe stroke. JAMA 2005;294:725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun LT, Grady KL, Kutner JS, et al. ; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. Palliative care and cardiovascular disease and stroke: a policy statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Circulation 2016;134:e198–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coping with grief after brain surgery. Nottingham (UK): Headway — the brain injury association; 2017. Available: www.headway.org.uk/news/national-news/coping-with-grief-after-brain-injury/ (accessed 2017 July 17). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loss and bereavement in people with dementia. Edinburgh (Scotland): Alzheimer Scotland; 2011. Available: www.alzscot.org/information_and_resources/information_sheet/1788_loss_and_bereavement_in_people_with_dementia (accessed 2017 July 17). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimbell B, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Managing uncertainty in advanced liver disease: a qualitative, multiperspective, serial interview study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, et al. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356:j878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliver D, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. Palliative care in chronic and progressive neurological disease: summary of a consensus review. Eur J Palliat Care 2016;23:232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National clinical guideline for stroke. 5th ed London (UK): Royal College of Physicians; 2016. Available: www.strokeaudit.org/SupportFiles/Documents/Guidelines/2016-National-Clinical-Guideline-for-Stroke-5t-%281%29.aspx (accessed 2017 Sept. 6). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999;23:197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.About palliative care. New York: Center to advance palliative care (CAPC) Available: www.capc.org/about/palliative-care/ (accessed 2017 July 18). [Google Scholar]