How signaling and scaffolding proteins are coordinated apically to control junctional tension and hence epithelial cell growth is unclear. Tsoumpekos et al. identify the Drosophila scaffolding protein Big bang as a novel regulator of growth in epithelial cells of the wing disc by showing that big bang ensures proper junctional tension and apical cytocortex organization.

Abstract

Growth of epithelial tissues is regulated by a plethora of components, including signaling and scaffolding proteins, but also by junctional tension, mediated by the actomyosin cytoskeleton. However, how these players are spatially organized and functionally coordinated is not well understood. Here, we identify the Drosophila melanogaster scaffolding protein Big bang as a novel regulator of growth in epithelial cells of the wing disc by ensuring proper junctional tension. Loss of big bang results in the reduction of the regulatory light chain of nonmuscle myosin, Spaghetti squash. This is associated with an increased apical cell surface, decreased junctional tension, and smaller wings. Strikingly, these phenotypic traits of big bang mutant discs can be rescued by expressing constitutively active Spaghetti squash. Big bang colocalizes with Spaghetti squash in the apical cytocortex and is found in the same protein complex. These results suggest that in epithelial cells of developing wings, the scaffolding protein Big bang controls apical cytocortex organization, which is important for regulating cell shape and tissue growth.

Introduction

Epithelial tissue morphogenesis and growth are regulated by a plethora of mechanisms and components, including the actomyosin cytoskeleton, polarity regulators, various signaling pathways, systemic cues, and cell–cell and cell–matrix contacts (Zhang et al., 2010; Lye and Sanson, 2011; Röper, 2015). Many of the participating components are organized as multiprotein complexes in the apex of the cell, such as adhesion or signaling complexes, and are instrumental in regulating cell and tissue behavior—for example, cell size, cell division and shape, and tissue growth and folding. Signals can modulate actomyosin activity, thereby inducing morphogenetic changes. On the other hand, there is increasing evidence that mechanical forces originating from the actin cytoskeleton are essential regulators of tissue morphogenesis and growth by modulating signaling pathway activities (Lye and Sanson, 2011; Colombelli and Solon, 2013; Clark et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2016; LeGoff and Lecuit, 2016; Vasquez and Martin, 2016). Excess actin polymerization, for example, induced by various actin-binding proteins, can result in excess growth (Fernández et al., 2011; Sansores-Garcia et al., 2011; Yu and Guan, 2013; Gaspar and Tapon, 2014; Rauskolb et al., 2014; Deng et al., 2015; Sun and Irvine, 2016). How tension is sensed and how it is converted into chemical signaling to modify gene expression and ultimately cell behavior is still poorly understood. So far, no general concept has emerged, which may also be a result of a variety of cell- and tissue-specific tension sensors and their cellular effectors. Among the known tension sensors involved in growth control are cytoskeletal components, e.g., Spectrin and actin (Sansores-Garcia et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2015; Fletcher et al., 2015; Gaspar et al., 2015), but also the junctional components α- and β-catenin and p120-catenin, which act either indirectly via other proteins or directly, by translocating into the nucleus (Spadaro et al., 2012; Rauskolb et al., 2014). These few examples underscore the important role of cytoskeleton-/junction-mediated tension in growth control, but at the same time they unveil the complexity of growth regulation by tension. Among the effectors are signaling pathways, such as ECM-mediated signaling or the Hippo pathway, which are conserved from flies to mammals (Ingber, 2006; Badouel et al., 2009; Halder et al., 2012; Dupont, 2016; Sun and Irvine, 2016).

These results also indicate that we are far from a complete picture of how tissue tension controls growth. Given that adherens junctions, a major site of tension modulation, reside apically in epithelial cells, and that many of the regulatory and signaling molecules localize apically as well, one important question remains, namely, which components help to organize the apical cytocortex itself. Solving this question is crucial to understand how the different factors involved are coordinated and how they impact junctional tension. To identify these components, we conducted a genetic modifier screen aimed to find novel regulators of wing growth (Nemetschke and Knust, 2016). One of the modifiers turned out to be big bang (bbg). bbg encodes a scaffolding protein with three PSD-95/Discs large/ZO-1 (PDZ) domains, which has previously been shown to regulate border cell migration and gut immune responses (Aranjuez et al., 2012; Bonnay et al., 2013).

PDZ domains are protein–protein interaction domains composed of 80 to 100 amino acids each (Ye and Zhang, 2013) and are among the most abundant protein interaction domains described. A recent examination of the genomic SMART database revealed the presence of 88 PDZ domain–containing proteins encoded in the Drosophila melanogaster genome, and about twice as much in the human genome. PDZ domain–containing proteins function as scaffolding molecules, which can contain one or several PDZ domains, often along with other protein–protein interaction domains, e.g., SH3, L27, or GUK domains. Their structural organization makes them versatile proteins to organize multiprotein scaffolds, which are involved in the assembly, maintenance, and function of localized macromolecular complexes or networks. These scaffolding proteins mediate important cell biological functions, such as apico-basal cell polarity, adhesion, or signaling (Sheng and Sala, 2001; Roh and Margolis, 2003; Zhang and Wang, 2003; Ye and Zhang, 2013).

Results presented here now add a novel function to PDZ domain–containing proteins by showing that the scaffolding protein Bbg controls the apical cytocortex in cells of the developing fly wing discs by organizing an apical protein complex. One component of this complex turned out to be Spaghetti squash (Sqh), the Drosophila regulatory light chain of nonmuscle myosin. Loss of Bbg reduces the level of Sqh and its apical localization. We further show by epistasis experiments that Bbg acts upstream of Sqh, because all phenotypes manifested in the absence of bbg, namely reduced junctional tension, increased apical surface area, and reduced wing growth, could be rescued by the expression of a constitutively active form of Sqh.

Results

bbg regulates wing growth during Drosophila development

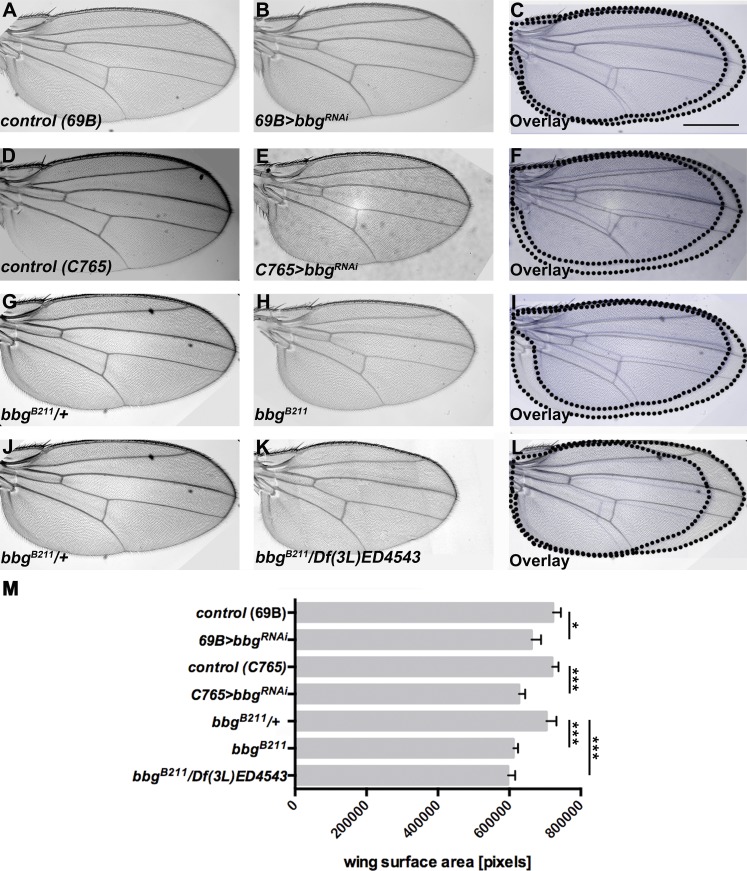

The Drosophila wing imaginal discs have turned out as an ideal model in which to study the genetic, molecular, and cell biological basis of various aspects of tissue morphogenesis and growth. To identify novel regulators of wing growth, we performed a genetic screen by scoring for mutations that dominantly modify the small wing phenotype induced by overexpression of the membrane-bound extracellular domain of Crb (Nemetschke and Knust, 2016). One of the enhancers identified in this screen was bbg. bbg encodes a scaffolding protein with three PDZ domains and has been described to control border cell migration in the follicle (Kim et al., 2006) and to modulate the gut immune tolerance (Bonnay et al., 2013). To determine whether bbg controls wing size on its own, we knocked down bbg activity in developing wings. RNAi-mediated knockdown of bbg by using two different Gal4 lines resulted in smaller wings (Fig. 1, A–F; quantified in Fig. 1 M). Reduction of Irbp, a predicted off-target of bbg RNAi (Aranjuez et al., 2012), did not show any growth defect in wings of adult flies (Fig. S1 A–F; quantified in Fig. S1 G). bbgB211 homozygous mutant flies, which are viable (Kim et al., 2006), as well as bbgB211/Df(3L)4543 hemizygotes, develop even smaller wings (Fig. 1, G–L; quantified in Fig. 1 M).

Figure 1.

Loss of bbg results in smaller wings. (A–C) Control (69B-Gal4) wing (A), wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (B), and overlay (C). (D–F) Control (C765-Gal4) wing (D), wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi with C765-Gal4 (E), and overlay (F). (G–I) bbgB211/+ heterozygous wing (G), bbgB211 mutant wing (H), and overlay (I). (J–L) bbgB211/+ heterozygous wing (J), bbgB211/Df(3L)ED4543 wing (K), and overlay (L). (M) Wing size measurement of the surface area of 50 (A–C and G–I) and 15 (D–F and J–L) independent females per genotype. The statistical analysis (M) used t test and ANOVA. *, P ≤ 0.1; ***, P ≤ 0.001. G and J show the same wing, because all figures depicted here were obtained in the same experiment. Error bars show SD. Bar, 500 µm.

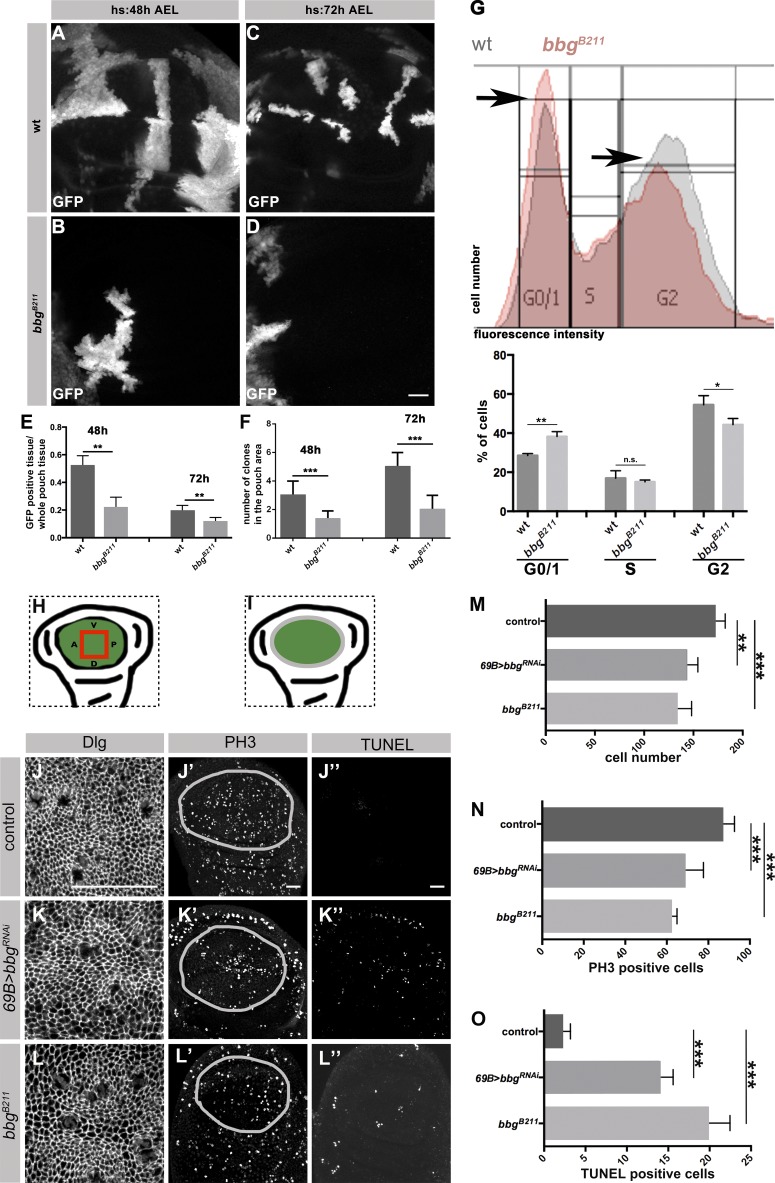

The adult fly wing develops from the wing imaginal disc, an epithelial sac built from a single layered epithelium. Specified during embryogenesis, wing discs expand about a 1,000-fold through proliferation during larval stages. The wing blade originates from the central area of the disc, the pouch (Fig. 2 I, green). To analyze the role of bbg in wing growth, we studied the proliferation behavior of bbgB211 homozygous cells by inducing bbgB211 mutant clones at two different developmental stages. To exclude any cell competition, GFP-positive bbgB211 mutant clones were studied in bbgB211 mutant discs. Their behavior was compared with that of GFP-positive WT clones induced in WT discs. The total clone area per wing pouch was determined in third instar larvae (L3) discs. GFP-positive bbgB211 clones in bbgB211 mutant discs were ∼50% or 70% smaller than GFP-positive WT clones in WT discs when induced at 48 h or 72 h after egg laying (AEL), respectively (Fig. 2, A–F; quantified in Fig. 2 E). In addition, the number of GFP-labeled bbgB211 mutant clones was reduced by ∼50% compared with the number of WT clones when induced 48 h AEL, and ∼60% less mutant clones were observed upon induction at 72 h AEL (Fig. 2 F). These results indicate that bbg is required for normal wing growth in Drosophila.

Figure 2.

Loss of bbg results in fewer cells and increased apoptosis in L3 wing discs. (A–D) GFP expressing clones in WT (A and C), and bbgB211 mutant L3 wing discs (B and D) induced at different time points (heat-shock [hs] 48 h and 72 h AEL) and stained with an anti-GFP. (E and F) Ratio of GFP-positive clones to the whole pouch (E), and number of GFP-positive clones in the pouch of WT and bbgB211 mutant L3 wing discs (F), induced by 48 and 72 h AEL, using 10 independent discs per genotype. (G) FACS analysis from cells of ∼20 L3 wing discs (10,000 events/cells per condition) of WT and bbgB211 mutant. Histograms display DNA content/fluorescent intensity (x-axis) and cell numbers (y-axis). Diagram: Mean of WT and bbgB211 mutant cells in every cell cycle stage (three biological replicates per condition). (H and I) Cartoons representing the wing pouch (green), the area measured in J, K, and L (red box, H) and the outline of the pouch measured in J′, J′′, K′, K′′, L′, and L′′ (gray outline, I). Control (69B-Gal4; J–J′′), 69B>bbgRNAi (K–K′′), and bbgB211 mutant (L–L′′) L3 wing discs stained with anti-Dlg, anti-PH3, and TUNEL, respectively. Measurement of cell numbers (M), PH3-positive cells (N), and TUNEL-positive cells (O) in all three genotypes, respectively, using eight independent L3 wing discs per genotype. The statistical analysis (E–G and M–O) used t test and ANOVA. *, P ≤ 0.1; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. Error bars show SD. Bars, 25 µm.

To further determine whether the smaller wings of flies lacking bbg were a result of cell cycle arrest, we identified the cell cycle stages in WT and bbgB211 mutant wing disc cells by FACS analysis. Notably, we compared exactly the same number of events both in WT and bbgB211 mutants. The two different peaks shown in the histogram (Fig. 2 G) allowed us to distinguish the G0/1 and G2 phases (black arrows in Fig. 2 G). In the absence of bbg, the number of cells in G2 are reduced by ∼19% and those in G0/G1 are increased by ∼19% compared with the corresponding numbers of WT cells (Fig. 2 G). From this we conclude that loss of bbgB211 perturbs cell cycle progression, because there are fewer cells in G2 and more cells in G1/G0. To better understand the basis of the perturbed cell cycle, we determined cell number, cell division, and apoptosis in wing discs of L3 larvae. The analysis was restricted to the center of the wing pouch (red rectangle in Fig. 2 H). Cell borders were marked by an antibody against Discs large (Dlg). L3 wing pouches of animals expressing bbgRNAi or of bbgB211 homozygous mutant animals exhibited 20% and 35% fewer cells, respectively, in comparison to control animals (Fig. 2, J–L′; quantified in Fig. 2 M).

Cell numbers and hence wing size can be regulated through cell divisions or cell death or a combination of these, and many genes have been identified that regulate this process (Hariharan, 2015). To study the effect of bbg on proliferation, the number of mitotic cells in the whole pouch area (Fig. 2 I, green) was counted, using an antibody that detects mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 (PH3). Compared with WT control animals, the number of mitotic cells was reduced by 22% in wing pouches of L3 larvae expressing bbgRNAi and by 29% in bbgB211 homozygous mutant animals (Fig. 2, J′, K′, and L′; quantified in Fig. 2 N). This result, together with a comparable decrease in cell number in bbgB211 mutant discs (see Fig. 2 M) and an increase in the number of cells in G1/G0 (Fig. 2 G), pointed to an increase in apoptosis. To corroborate this assumption, apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL assays in wing discs. In the wing pouch of WT L3 discs, the number of apoptotic cells was very low (Fig. 2 J′′), as reported previously (Milán et al., 1997). In contrast, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly increased upon knockdown or loss of bbg (Fig. 2, K′′ and L′′; quantified in Fig. 2 O). This result is in agreement with the observation that fewer clones were observed in mutant discs when induced at 72 h APF (Fig. 2 F). To exclude the possibility that bbgB211 RNAi wing discs are developmentally delayed, we expressed RNAi only in the posterior compartment using en-Gal4 and compared the anterior/posterior ratio of PH3- and TUNEL-positive cells. The results support the previous data, in that the posterior compartment with reduced level of Bbg reveals less proliferating, PH3-positive cells and more apoptotic cells (Fig. S2, A–F). Collectively, the reduced wing-size in bbgB211 mutants can be attributed, at least partially, to increased apoptosis.

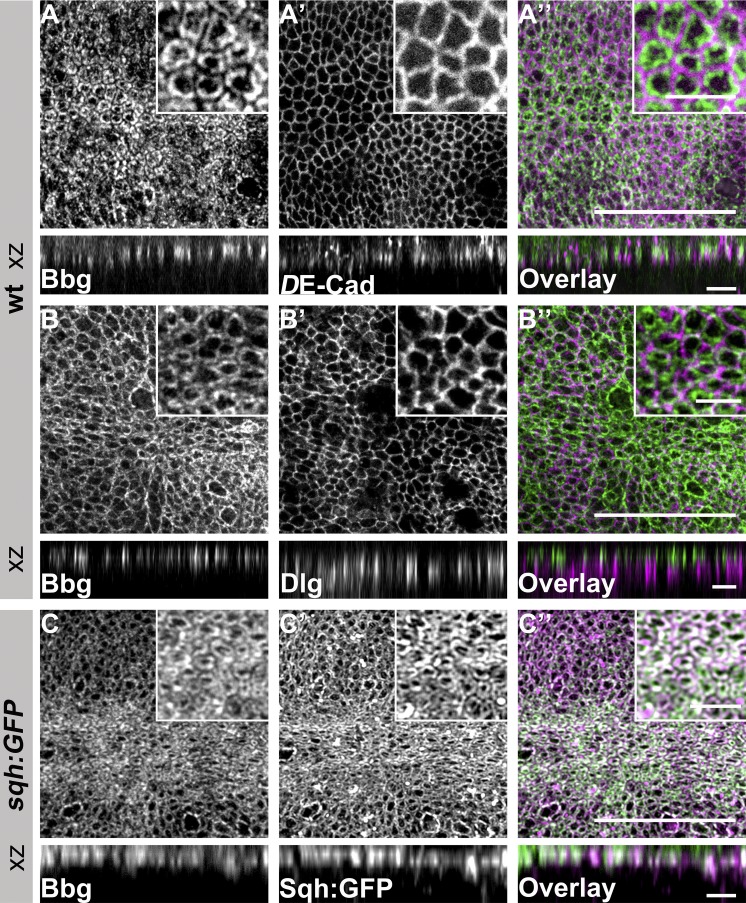

Bbg localizes in the apical cytocortex and regulates growth through Sqh

To further elucidate the mechanism by which bbg exerts its function, we raised antibodies that should detect all predicted Bbg isoforms. The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by Western blot (WB) analysis (Fig. S3 A) and immunohistochemical staining of wing discs, in which bbg was reduced in the posterior compartment by RNAi-mediated knockdown (Fig. S3, B–B′′). In wing disc cells of third instar WT larvae, Bbg localized in the apical cytocortex (Fig. 3, A–A′′), apical to Dlg (Fig. 3, B–B′′). Here, Bbg colocalized with Sqh-GFP (Fig. 3, C–C′′), the Drosophila regulatory light chain of nonmuscle myosin II (Karess et al., 1991). Sqh has been reported to be enriched in the apical cytocortex (Landsberg et al., 2009) and is required, together with the myosin II heavy chain, encoded by zipper (zip), for many morphogenetic processes, including imaginal discs morphogenesis (Edwards and Kiehart, 1996; Aldaz et al., 2013). In the wing disc, Bbg was enriched in the cell cortex along the anterior-posterior (AP) compartment boundary (Fig. S3, C–C′, white arrows), thus reproducing the pattern of actin and Sqh localization (Landsberg et al., 2009), and in the cortex of cells entering mitosis (Fig. S3 C′, magenta arrowheads).

Figure 3.

Bbg localizes in the apical cytocortex of L3 wing disc epithelial cells. (A–B′′) WT L3 wing discs stained with anti-Bbg (A and B), anti–DE-Cadherin (DE-Cad; A′), anti-Dlg (B′), and the respective overlays (A′′ and B′′). (C–C′′) sqh-GFP L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg (C), Sqh-GFP (endogenous signal, C′) and the respective overlay (C′′). The projection in B was taken from a more lateral view compared with that of A and C. Insets, top right: Respective pouch areas. xz projection shows the central area of the same L3 wing discs. Bars: (A′′, B′′, and C′′) 25 µm; (xz projections and small boxes) 5 µm.

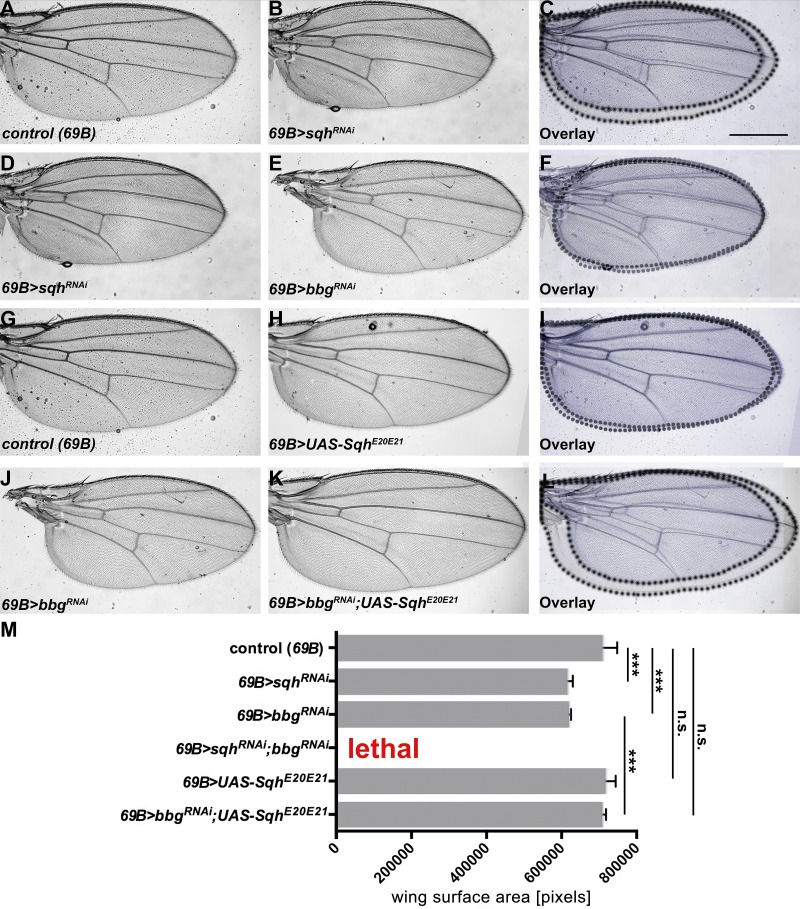

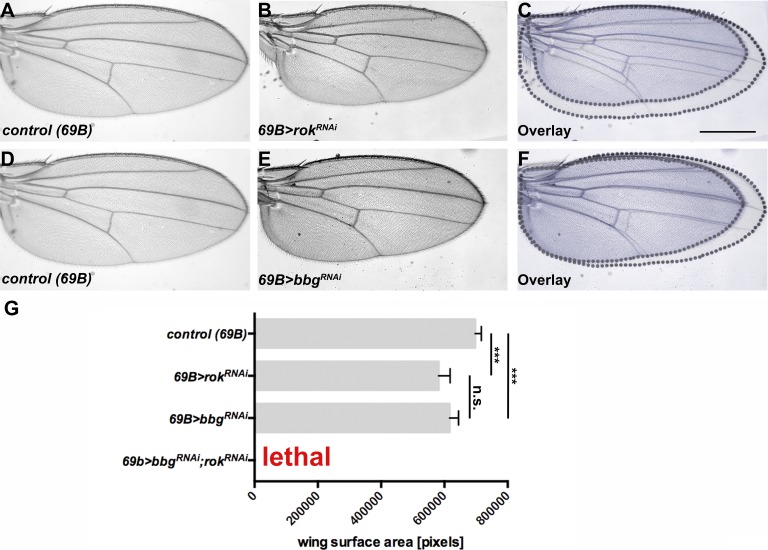

To analyze a possible link between bbg and sqh, we looked at the role of sqh in WT and bbg mutant discs. Therefore, we asked whether Sqh itself regulates wing size. Knocking down sqh reduced wing size to a similar extent as knocking down bbg (Fig. 4, compare A–C with D–F; quantified in Fig. 4 M). Strikingly, concomitant knockdown of sqh and bbg in the whole wing resulted in nearly 100% lethality. To further unveil the relationship between bbg and sqh, we overexpressed ShqE20E21, a variant in which the two regulatory phosphorylation sites, Thr-20 and Ser-21, are mutated to phosphomimetic Glu residues. This variant has been shown to act as a constitutive active form of Sqh (Winter et al., 2001). As previously reported (Rauskolb et al., 2014), overexpression of SqhE20E21 in developing WT wings had no effect on wing growth (Fig. 4, G–I; quantified in Fig. 4 M). However, concomitant expression of SqhE20E21 and bbg RNAi rescued the small wing phenotype of bbg RNAi flies (Fig. 4, J–L; quantified in Fig. 4 M). The activity of Sqh is regulated by phosphorylation, and one of the known kinases is Rho-associated protein kinase (Rok; Winter et al., 2001; Amano et al., 2010). As previously shown (Rauskolb et al., 2014), lowering the activity of Rok also gives rise to smaller wings (Fig. 5, A–C and G). Therefore, we also tested the genetic interaction between bbg and rok, and found that concomitant knockdown of rok and bbg also resulted in lethality (Fig. 5 G), supporting the link between bbg and sqh. These results suggest that bbg acts upstream of sqh to control wing size.

Figure 4.

bbgand sqh genetically interact. (A–C) Control (69B-Gal4) wing (A), wing expressing UAS-sqhRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (B), and overlay (C). (D–F) Wing expressing UAS-sqhRNAi (D), wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (E), and overlay (F). (G–I) Control (69B-Gal4) wing (G), wing expressing UAS-SqhE20E21 with 69B-Gal4 (H), and overlay (I). (J–L) Wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (J), wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi;UAS-SqhE20E21 with 69B-Gal4 (K), and overlay (L). (M) Wing size measurement of the surface area of 15 independent females per genotype. The statistical analysis (M) used t test and ANOVA. ***, P ≤ 0.001. A and G show the same control wing, because all figures depicted were obtained in the same experiment. Error bars show SD. Bar, 500 µm.

Figure 5.

bbgand rok genetically interact. (A–C) Control (69B-Gal4) wing (A), wing expressing UAS-rokRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (B), and overlay (C). (D–F) Control (69B-Gal4) wing (D), wing expressing UAS-bbgRNAi with 69B-Gal4 (E), and overlay (F). (G) Wing size measurement of the surface area of 15 independent females per genotype. The statistical analysis (G) used t test and ANOVA. ***, P ≤ 0.001. A and D show the same control wing, because all figures depicted were obtained in the same experiment. Error bars show SD. Bar, 500 µm.

Bbg stabilizes Sqh in the apical cytocortex of wing disc cells

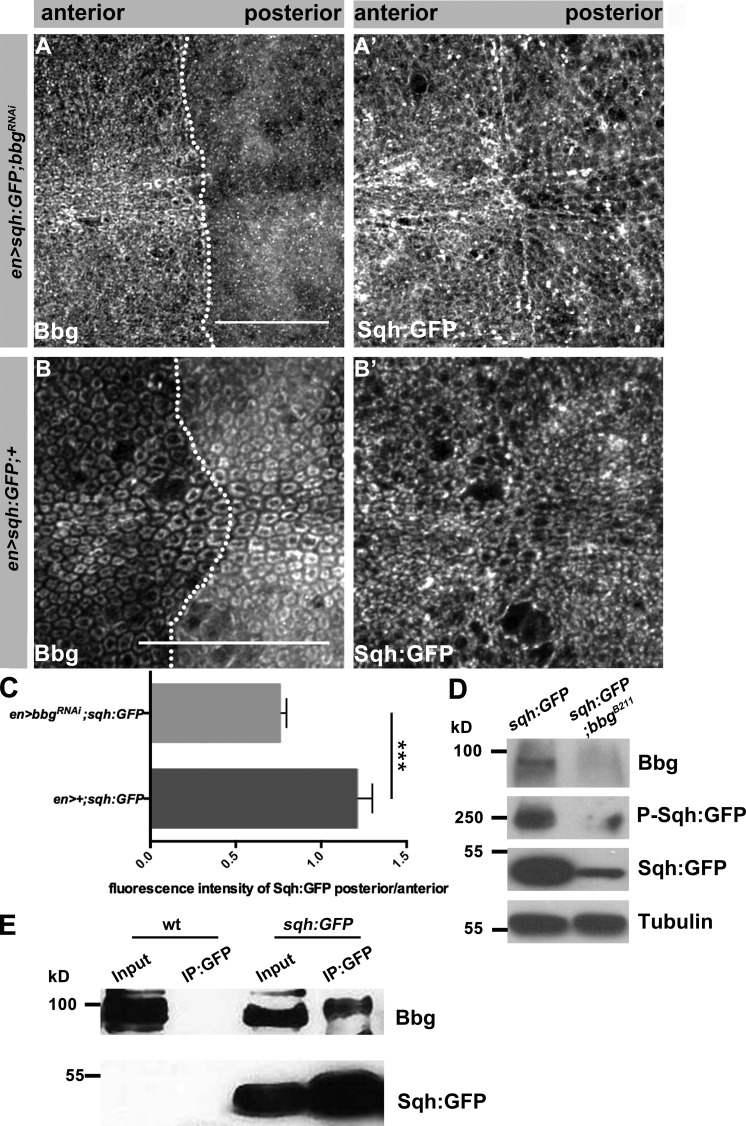

Next, we set out to study the molecular relationship between Bbg and Sqh. To analyze the localization of Sqh, we used animals expressing Sqh-GFP under the endogenous promoter in a sqh mutant background. This transgene completely rescues all sqh mutant phenotypes (Royou et al., 2004). Upon reduction of Bbg, Sqh-GFP was more diffuse (Fig. 6, A–B′). In addition, the amount of Sqh-GFP, as measured by fluorescence intensity, was reduced by 30% upon reduction of bbg in the posterior compartment of the wing disc in comparison to the control, anterior compartment (Fig. 6 C). To further determine the molecular interaction between Bbg and Sqh, we performed WB analysis of protein extracts from L3 wing discs. The amount of Sqh-GFP was reduced in bbgB211 mutants (Fig. 6 D), confirming the results from immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, the phosphorylated form of Sqh was reduced in the absence of Bbg as well.

Figure 6.

Bbg is in the same protein complex as Sqh and stabilizes Sqh in the apical cytocortex. (A and A′) Pouch of en-Gal4, UAS:RFP, sqh-GFP; UAS-bbgRNAi L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg (A) and Sqh-GFP (endogenous signal, A′). (B and B′) Pouch of en-Gal4, UAS:RFP, sqh-GFP L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg (B) and Sqh-GFP (endogenous signal, B′), respectively. (C) Ratio of fluorescence intensity of Sqh-GFP in en-Gal4, UAS:RFP, sqh-GFP; UAS-bbgRNAi and en-Gal4, UAS:RFP, sqh-GFP L3 wing discs (six independent discs per genotype). (D) WB of protein extracts isolated from sqh-GFP and sqh-GFP;bbgB211 L3 wing discs, showing a reduction of total and phosphorylated Sqh-GFP in sqh-GFP;bbgB211. Tubulin served as loading control. Antibodies used were anti-Bbg, anti-GFP (for both Sqh-GFP and Phospho-Sqh-GFP), and antitubulin. (E) IP from protein extracts isolated from WT and sqh-GFP L3 wing discs, using an anti-GFP antibody (three biological replicates per condition). Bbg is immunoprecipitated from extracts of Sqh-GFP (two right lanes), but not from WT extracts (two left lanes). The statistical analysis (C) used t test and ANOVA. **, P ≤ 0.01. Error bar shows SD. Bars, 25 µm.

The colocalization of the two proteins in the apical cortex let us to speculate that the two proteins may be part of the same complex. To address this question, we immunoprecipitated Sqh-GFP from protein extracts of wing disc lysates, using an anti-GFP antibody. Bbg was pulled down from discs expressing Sqh-GFP (Fig. 6 E, right two lanes), but not from control (WT) discs (Fig. 6 E, left two lanes). To conclude, Bbg can be found in a protein complex with Sqh in wing imaginal discs, where it stabilizes Sqh in the apical cytocortex.

Bbg is required to stabilize junctional tension in wing imaginal discs

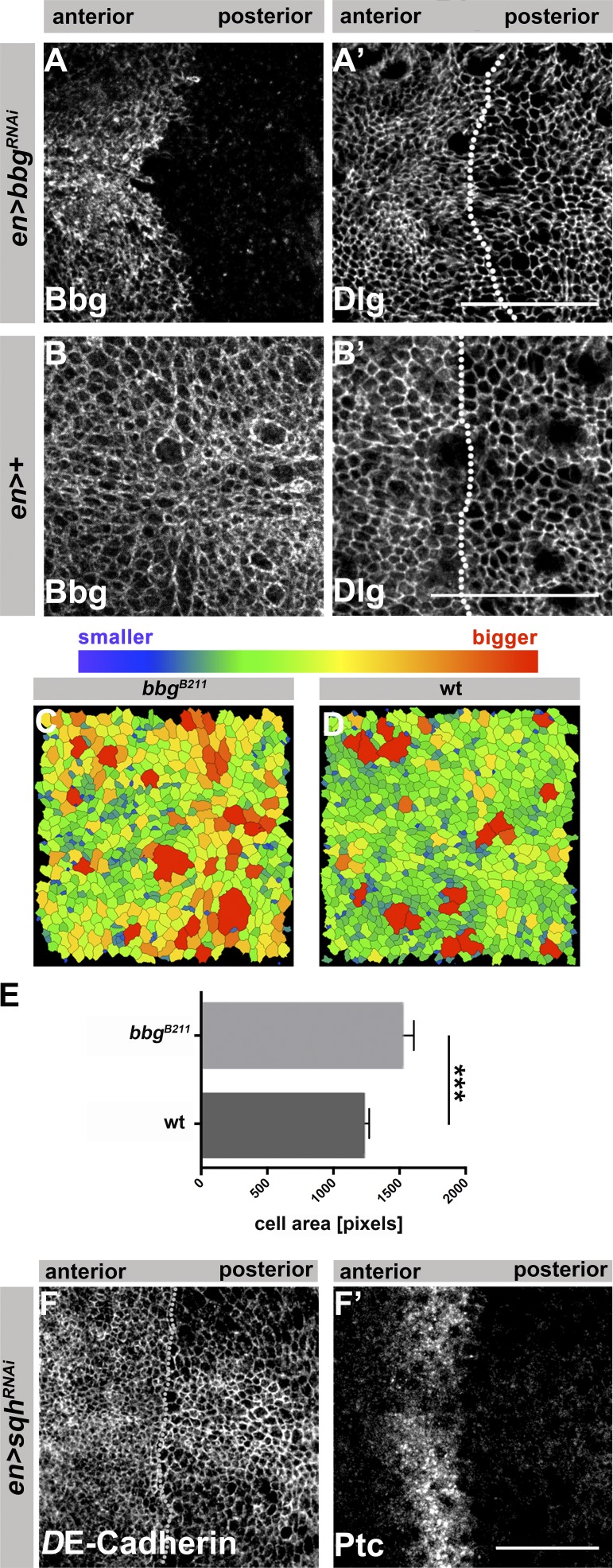

We noticed that the apical surface of cells in bbgB211 mutant L3 wing discs appeared larger in size in comparison to WT cells (Fig. 2, J and L). We confirmed this observation by knocking down bbg in the posterior compartment of L3 wing discs (Fig. 7, A–B′). Quantification of apical cell surface area in wing discs stained for DE-cadherin to outline the cell apex (Fig. 7, C and D) revealed a ∼23% increase of apical cell surface area in bbgB211 mutant cells compared with corresponding WT cells (Fig. 7 E). Similar to loss of bbg, RNAi-mediated reduction of sqh in the posterior compartment had no effect on DE-cadherin localization and tissue integrity (Fig. 7 F), and resulted in enlarged cell surface areas (Fig. 7, F–F′), supporting the previous conclusion that bbg and sqh act on a common pathway.

Figure 7.

Loss of bbg or sqh results in cells with larger surface areas. en>bbgRNAi (A and A′) and control (en-Gal4; B and B′) L3 wing discs, stained with anti-Bbg and anti-Dlg, respectively. The dotted lines in A′ and B′ highlight the AP boundary. Images of bbgB211 mutant (C) and WT (D) L3 wing discs tracked using the “Tissue Analyzer” plug-in from Fiji to quantify the surface area of the cells. Cell outlines were tracked from anti–DE-cadherin staining from fixed tissues. (E) Measurement of the mean pixel area of each cell per image (three independent samples were quantified per genotype). (F and F′) Wing pouch of L3 discs expressing UAS-sqhRNAi with en-Gal4, stained with anti–DE-cadherin (F) and anti-Patched (Ptc; F′). The dotted line in H highlights the AP boundary. The statistical analysis (F) used t test and ANOVA. ***, P ≤ 0.001. Error bar shows SD. Bars: (A–B′ and F and F′) 25 µm.

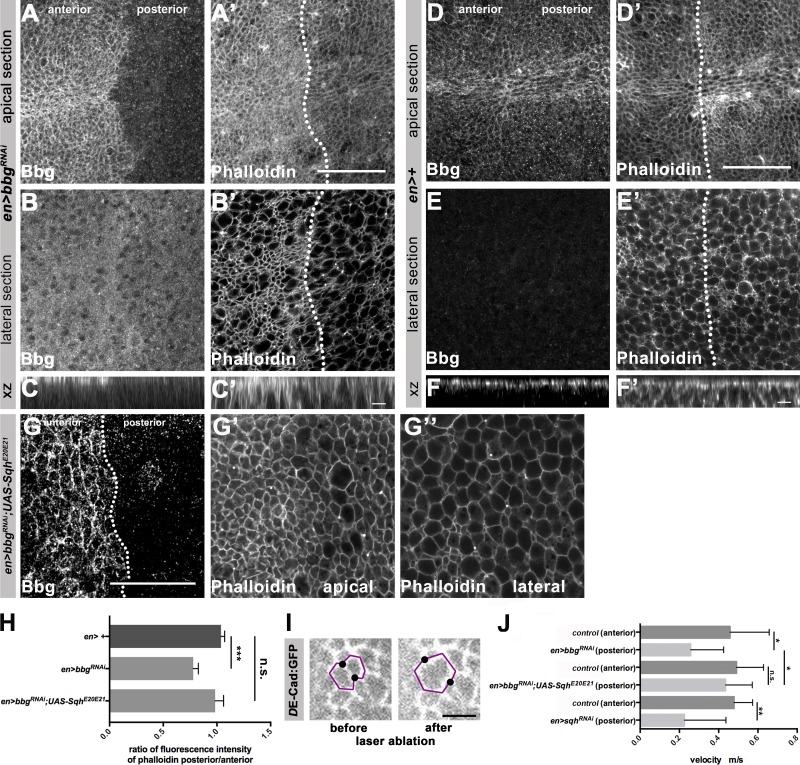

Because Sqh is a major regulator of actin, we asked whether absence of bbg affects actin localization. We knocked down bbg by expressing RNAi in the posterior compartment of wing discs and stained with phalloidin. Under these conditions, F-actin was reduced by ∼25% both apically and laterally in comparison to the anterior, bbg-positive tissue (Fig. 8, A–F′; quantified in Fig. 8 H). Reduction of F-actin upon knockdown of bbg could be prevented by simultaneous overexpression of SqhE20E21 (Fig. 8, G–G′′, quantified in Fig. 8 H).

Figure 8.

Bbg and Sqh cooperate to control the apical actomyosin and junctional tension. (A–B′) en-Gal4; UAS-bbgRNAi L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg and Phalloidin-488 (F-actin), apical (A and A′) and lateral (B and B′) sections. (C and C′) xz projection of the central area of the respective L3 wing disc shown in A–B′. (D–E′) Control (en-Gal4) L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg and Phalloidin-488, apical (D and D′) and lateral (E and E′) sections. (F and F′) xz projection of the central area of the respective L3 wing disc shown in D–E′. (G) en-Gal4, UAS-bbgRNAi;UAS-SqhE20E21 L3 wing disc stained with anti-Bbg and Phalloidin-488 (F-actin), apical (G′) and lateral (G′′) sections. (H) Ratio of posterior/anterior fluorescence intensity of phalloidin of control (en-Gal4), en-Gal4, UAS-bbgRNAi and en-Gal4, bbgRNAi;UAS-SqhE20E21 L3 wing discs (seven independent discs per condition). (I) Cells from DE-cadherin:GFP L3 wing discs before and after laser ablation. The black dots show the cell vertices that were displaced upon laser ablation. (J) Measurement of the velocity of the displaced cell junctions in the anterior en-Gal4 (control) and posterior (en-Gal4, UAS-bbgRNAi, en-Gal4, UAS-bbgRNAi;UAS-SqhE20E21, en-Gal4; UAS-sqhRNAi, respectively) compartments upon laser ablation; n = 14. The statistical analysis (H) used t test and ANOVA. *, P ≤ 0.1; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. Error bar shows SD. Bars: (A–B′, D–E′, and G–G′′) 25 µm; (C, C′, F, and F′) 5 µm.

Actin is a major regulator of tension, and tension has been shown to regulate growth (Mao et al., 2013; Schluck et al., 2013; LeGoff and Lecuit, 2016). To determine whether bbg controls tension in wing imaginal discs, we ablated single cell junctions by laser and quantified the initial velocity of the movement of vertices, which is a suitable readout for mechanical tension (Fig. 8 I; Landsberg et al., 2009). The velocity was reduced by 47% upon RNAi-mediated knockdown of bbg in the posterior compartment in comparison to the velocity in the anterior, bbg-positive control compartments (Fig. 8 J). A similar reduction in the initial velocity (52%) was observed upon knocking down sqh (Fig. 8 J). Strikingly, simultaneous expression of SqhE20E21 and bbg RNAi rescued the reduced velocity observed in bbg RNAi discs and brought it back to WT levels. To conclude, bbg controls junctional tension in wing imaginal discs by promoting the activity of Sqh.

Collectively, our data show that bbg is a key organizer of the apical cytocortex by regulating the localization and hence activity of Sqh. This conclusion is based on the observation that all defects observed upon loss of bbg, namely increased apical surface, reduced junctional tension, and reduced wing growth, were all rescued by the expression of a constitutively active form of Sqh.

Discussion

Wing growth is controlled by various signaling pathways, cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion, cell shape, and cytoskeletal activity (Hariharan, 2015). Here we show that the scaffolding protein Bbg is an organizer of the apical cytocortex, and is required for cell shape and junctional tension, thereby regulating growth of the Drosophila wing imaginal discs.

bbg expression is highly dynamic in a variety of epithelia throughout development. Previous data (Kim et al., 2006) and results presented here suggest that the subcellular localization of Bbg proteins is cell type–specific, which could explain the distinct functions observed in different tissues. In the adult midgut, where bbg mediates the gut immune response, Bbg colocalizes with Coracle at septate junctions (Bonnay et al., 2013). In wing imaginal discs, however, Bbg could not be detected at the septate junctions but rather in the apical cytocortex (this study). According to Flybase (http://flybase.org/), bbg encodes eight isoforms. Therefore, it is possible that the difference in Bbg localization is a result of the expression of alternative isoforms in different tissues, which may organize distinct protein complexes with cell-type specific localization and function. In fact, unlike in wing discs, knocking down bbg in migrating border cells had no obvious effect on actomyosin organization (Aranjuez et al., 2012). mRNAs of all predicted Bbg isoforms are expressed in wing discs (Tsoumpekos, 2016); therefore, the function described here cannot be allocated to any specific isoform. All Bbg proteins are scaffolding proteins with two or three PDZ domains. PDZ domains are protein–protein interaction modules, often found together with other protein–protein interaction domains in molecules that organize supramolecular protein complexes, which are involved in diverse biological processes, such as signaling, trafficking, adhesion, or growth (Subbaiah et al., 2011). Many of these processes depend on the ability to cluster functionally related components at defined cellular compartments at or close to the plasma membrane. Here we show that Bbg resides in a protein complex together with Sqh in the apical cytocortex of wing imaginal disc cells, but whether the two proteins interact directly remains to be elucidated. The organization of Bbg with three PDZ domains makes it an ideal candidate to coordinate components of the actomyosin network, including Sqh, and regulators of growth control.

Various results point to a close functional link between bbg and sqh in wing imaginal discs: both are required for proper wing size and show genetic interactions, their proteins colocalize in a common complex in the apical cytocortex of wing disc epithelial cells, both proteins are needed for maintaining proper junctional tension in the wing imaginal disc, and Bbg stabilizes Sqh in the apical cytocortex. Increasing evidence points to an important role of tension in growth regulation (Mao et al., 2011; Rauskolb et al., 2011, 2014; Sansores-Garcia et al., 2011; LeGoff and Lecuit, 2016; Sun and Irvine, 2016). Therefore, we hypothesize that Bbg controls growth in the imaginal discs by regulating tension through the organization of the actomyosin network. This assumption is supported by various observations. First, the protein complex pulled down with an antibody against Bbg contained, besides Sqh, other regulators of the actomyosin network, including the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain (called Zipper in flies), actin 57B, and α- and β-spectrin (Tsoumpekos, 2016). Spectrins are cytoskeletal scaffolding proteins, which are important for plasma membrane integrity and cytocortex organization (Machnicka et al., 2014), and modulate the activity of the apical actomyosin, thereby controlling the Hippo signaling pathway (Deng et al., 2015). In addition, mutations in bbg were found to modify the synapse growth phenotype induced by a dominant-negative mutation in Glued (Chang et al., 2013). Glued encodes Dynactin 1, a subunit of the dynactin complex, which associates with cytoplasmic dynein, a motor protein involved in microtubule-based transport processes. Second, the apical surface was enlarged in bbg mutant wing disc epithelial cells, which is likely to be caused by a decrease in F-actin. In the absence of dachs, for example, which encodes an unconventional myosin, the apical surface of wing disc cells is larger, and wing size is reduced (Mao et al., 2011).

Third, bbg mutant wing discs showed increased apoptosis. This could also be a consequence of F-actin destabilization, because increased F-actin levels induced by overexpressing of the capping proteins α and β can decrease apoptosis (Amândio et al., 2014). Finally, in WT wing discs, Bbg, together with actin and Sqh, is enriched at the AP compartment boundary, an area of increased tension required to prevent cell mixing along the compartment boundary (Landsberg et al., 2009; Umetsu and Dahmann, 2015). In addition, Bbg is enriched in dividing cells, which require increased tension during rounding up (Rosa et al., 2015).

How Bbg, by maintaining proper junctional tension, regulates tissue growth remains to be elucidated. Tension has been reported to be a regulator of the transcriptional coactivator Yorkie (Yki), the Drosophila orthologue of mammalian Yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (YAP/TAZ; Halder et al., 2012; Piccolo et al., 2014. This regulation can occur via the Drosophila kinase Warts (Wts; large tumor suppressor [LATS] in vertebrates; Wada et al., 2011; Rauskolb et al., 2014), a component of the Hippo pathway. Other studies suggest a more direct influence of the actomyosin on Yki activity (Dupont et al., 2011; Aragona et al., 2013). Reduced Yki phosphorylation (e.g., in the absence of the Warts or Hippo kinase) induces Yki translocation into the nucleus, where it up-regulates expression of antiapoptotic and proproliferation genes (Halder et al., 2012; Finch-Edmondson and Sudol, 2016; Sun and Irvine, 2016). Our preliminary results show that reduced growth in the absence of bbg is associated with reduced expression of the Hippo target gene Diap1, suggesting that bbg may regulate growth via the Hippo signaling pathway. This conclusion is in line with recent results showing that overexpression of Sqh in wing discs increases the expression of the Hippo target genes expanded and Diap1 (Rauskolb et al., 2014).

However, the canonical kinase cascade of the Hippo pathway is only one of several pathways that can regulate Yki activation and hence growth. For example, a recent study performed in Madine-Darbine canine kidney cells showed that tension mediated by the apical, circumferential actin belt represses translocation of Yki into the nucleus and hence target gene expression, a process that involves the interaction between E-cadherin and Merlin (Furukawa et al., 2017). Furthermore, vertebrate Yki has been documented to act as an apical sensor in some epithelial cells (Elbediwy et al., 2016). Although loss of bbg in wing discs does not affect overall epithelial polarity, E-cadherin localization, and tissue integrity, preliminary data indicate that some apical proteins (e.g., Crb) are affected in mutant cells. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that Bbg, as a multi-PDZ scaffolding protein, is a versatile organizer of the apical cytocortex, thereby regulating the overall apical organization. This, in turn, is important for proper control of Yki or other regulators of growth. Identifying additional components recruited by Bbg and unraveling their function and possible interactions will further our understanding of the protein network localized in the apical cytocortex that fine-tunes tissue growth.

Materials and methods

Genetics

bbgB211 has previously been described a null allele (Kim et al., 2006), and was provided by G.L. Boulianne (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada). The following RNAi lines were used: UAS-bbgRNAi (III), UAS-bbgRNAi (II), UAS-sqhRNAi (III), and UAS-IrbpRNAi (II; Vienna Drosophila Resource Center 15974, 15975, 7917, and 16758). UAS-SqhE20E21 (III) and en-Gal4;DE-Cad::GFP/DE-Cad::GFP;UAS-GFP (Aliee et al., 2012) and engrailed (en)-Gal4>UAS-RFP, sqh-GFP (II) were gifts from C. Dahmann (Technical University Dresden, Dresden, Germany). 69B-Gal4 and C765-Gal4, expressed in the whole wing disc, and engrailed-Gal4(hen), provided by S. Eaton (Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany), expressed in the posterior compartment of the wing, were used. Df(3L)ED4543/TM6C (8073) and yw,sqhAX3;sqh-GFP (Royou et al., 2004; 57144) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (http://flystocks.bio.indiana.edu/). Unless otherwise stated, flies were raised at 25°C on standard food. Flip-out clones were generated using ywhsflp;actinpromoter.FRT.STOP.FRT.Gal4-UAS-GFP (provided by S. Eaton) or by crossing the previous stock with bbgB211 flies. For wing disc clones, 37°C heat shocks were performed for 2 h at different developmental stages.

Generation of anti-Bbg antibody

Using a bbg cDNA as template, 0.67 kb, encoding 224 amino acids, was amplified by PCR using the following primers: forward, 5′-ATGTCGACGCAGTGCCAAGAGTCGAGGTCA-3′; reverse, 5′-GTGTCGACTCTTTAGTGGAGGATCAGCCTC-3′. The amplicon was subcloned into the plasmid pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen), digested with SalI (restriction sites included in the primers), and subcloned into pGEX-4T-1(His)6C (based on the Amersham vector pGEX-4T-1 with a GST-tag, modified to also include a 6xHis tag; Kim et al., 2006), provided by G.L. Boulianne. Expression of recombinant protein was induced (500 µM IPTG, 37°C, 4 h) using the BL21DE3 expression strain (Novagen). Tagged protein was purified using Ni-NTA Agarose beads (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GST-tagged recombinant protein was injected into female New Zealand White rabbits (2.5–3.0 kg). The serum was purified on HiTrap NHS-activated HP columns and concentrated in an Amicon Ultra 30K. The final concentration of the antibody was 5.64 mg/ml.

Flow cytometry

Approximately 20 L3 wing discs were dissociated into single cells using a solution containing trypsin and Hoechst 33342 (1:1,000; diluted in PBS) for 1.5 h at RT. The samples were directly sorted using FACS. The flow cytometry was performed on a 5-laser BD FACSAria IIIu sorter (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using the FACS Diva software (v8.0; BD Bioscience) and the flow cytometry modeling software ModFit LT. Gates were applied as follows: a P1 gate was set on a side scatter/forward scatter (SSC/FSC) dot plot to identify live cells based on size and shape. The P1 fraction was restricted by setting a P2 gate on a SSC/GFP (exponential, blue laser, 488 nm). The P3 gate was generated on a BV2421-W/BV421-H (linear, UV laser, 375 nm) dot plot to discriminate singlets and to visualize the DNA content using the Hoechst 33342 dye. Out of the P3 population, a histogram for counts/BV421-A (linear, UV laser, 375 nm) was generated to analyze the cell cycle. Each 10,000 events from P2 were acquired to analyze the cell cycle of the different samples and genotypes. Voltage parameters were set based on WT controls.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used at the indicated concentrations for immunofluorescence (IF)/ or WB/rabbit anti-Bbg (1:1,000; IF and WB; this work), mouse anti-Dlg (1:1,000; IF; DSHB 4F3), rat anti-DE-cadherin (1:1,000; IF; DSHB DCAD2), rabbit anti-PH3 (1:1,000; IF; Millipore 06–570), rabbit anti-IgG (1:1,000; WB; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rat antitubulin (1:3,000; WB; AbD Serotec), rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000; IF and WB; Invitrogen), mouse anti-GFP (1:1,000; WB; Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-Ptc (1:100; IF DSHB apa1), secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, 568, and 647 (1:1,000; IF; Invitrogen), or HRP (1:5,000; WB; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Phalloidin-488 (1:1,000; IF; Invitrogen) was used to label F-actin.

IF and imaging

Wing discs were dissected on ice, transferred to a sticky glue area on a common slide (e.g., WT with bbgB211 mutant, together), and processed together. Therefore, IF and imaging conditions for different samples of the same experiment were exactly identical. Discs were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 20 min, washed in PBT (PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in blocking solution (PBT/5% BSA). Tissues were washed with PBT, incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 2 h at RT, washed with PBT, and mounted in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 700 inverted confocal microscope using Zeiss Plan-Neofluar 25x 0.8 Oil/Gly/Water and Zeiss LCI Plan-Neofluar 63x 1.3 Gly/Water DIC lenses at 23°C and processed using ZEN2010 and Fiji. For Fig. 6 and for the processing of stained images, the “Tissue Analyzer” plug-in from Fiji was used, which automatically measures different parameters, such as cell surface area. All images shown are projections of 5 µm (except those shown in Fig. 8, A–G′′; sections were 1 µm each) and were representatives of the results obtained from several independent experiments (between 5 and 10 individual L3 wing discs and staining per genotype; more details in the legends to Figs. 2, 3, 6–8, S2, and S3). Fiji was used for quantification of cell numbers, PH3-positive, and TUNEL-positive cells. For this, a square of similar size was placed in the center of the pouch when comparing staining in whole discs, or in the center of the anterior and posterior compartment when comparing expression in these two compartments. For counting cell numbers, the Fiji plug-in “Cell Counter” was used. For measuring fluorescence intensity of Sqh or phalloidin, the same square selection was applied, and pixel intensity was measured using Fiji.

TUNEL assay

TUNEL assays were performed using the Roche in situ cell death detection kit (fluorescein, 1 684 795). In brief, L3 wing discs were fixed with 4% PFA in blocking solution for 20 min and washed with PBT. Discs were transferred to the reaction/enzyme buffer containing terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (provided by Roche). After enzyme incubation at 37°C for 1 h, discs were rinsed three times in PBT and, after incubation in secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 2 h at RT, discs were washed with PBT and mounted in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired using an LSM 700 inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss) using a 25× lens and processed using Fiji.

Mounting of adult wings

The left wings from female flies were dissected in PBS and mounted in Euparal MTNG medium (6372B). Wing size determination is the result of averaging 15 independent wing measurements (except from Fig. 1, which is derived from 50 wings), performed under strict temperature control (25°C), because the Gal4 system is temperature-dependent. By doing so, we tried to compensate for any phenotypic variability. Images were obtained with an Axionplan2 imaging microscope (Zeiss) using a 5× lens and processed using Fiji.

WBs and immunoprecipitation (IPs)

20 L3 wing discs were dissected in PBS on ice and homogenized in 50 µl 2 × SDS loading buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 0.2% Bromophenol nlue, 20% glycerol, and 2% β-mercaptoethanol) using a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube and pestle. Samples were boiled, clarified by centrifugation, and run on Phos-Tag gels (12.5%; WAKO) for separation of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated proteins. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane 0.45 µm (GE Healthcare) and probed using the antibodies described in the Antibodies section. For IPs, 200 L3 wing discs were collected on dry ice and homogenized before addition of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 250 µg/ml PefaBloc, 2 µg/ml aprotinin, and 1 µg/ml pepstatin). The lysate was left on ice for 30 min and clarified by centrifugation. 1 mg total protein was used per IP. After adding the antibody, the lysate was incubated at 4°C for 2 h. 50 µl protein G agarose (GE Healthcare) per IP was added and left to rotate at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed six times with lysis buffer and boiled with loading buffer for 5 min at 100°C, and proteins were analyzed by conventional SDS-PAGE.

Laser ablation

Experiments were performed essentially as described (Farhadifar et al., 2007). Wing imaginal discs (genotypes: en-Gal4;DE-Cad::GFP/DE-Cad::GFP;UAS-GFP/UAS-bbgRNAi, UAS-bbgRNAi;UAS-SqhE20E21, or UAS-sqhRNAi) were briefly rinsed twice in 70% ethanol, dissected in M3 medium (S3652; Sigma-Aldrich) and transferred to a 35-mm culture dish with glass bottom (P35G; MakTek). For the analysis of the vertex displacements, an inverted microscope with a 63×/1.2 numerical aperture water immersion objective was used. The laser beam was focused to a fixed spot of ∼1.2 µm in the focal plane. The laser focus is targeted at adherens junctions. Images were recorded every 0.25 s over a period of ∼30 s.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that reduction of Irbp does not affect wing growth. In Fig. S2, RNAi-mediated reduction of bbg results in reduced cell numbers and increased apoptosis in L3 wing discs. Fig. S3 shows that the anti-Bbg antibody specifically detects Bbg molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank G. L. Boulianne, S. Eaton, C. Dahmann, the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center and the Bloomington Stock Centers for flies and antibodies. Special thanks goes to Cagdas Göktas and Marcus Michel, laboratory members of C. Dahmann’s laboratory, for advice on laser ablation/cell tension experiments. We thank the following Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics facilities: Patrick Keller, antibody facility, for antibody production, Ina Nüsslein for FACS analysis, and the Light Microscopy Facility, in particular J. Peychl, for microscopy guidance. The authors are grateful to Marino Zerial for critical and constructive comments on the manuscript, to members of the Knust laboratory for fruitful and constant advice, and to Francois Schweisguth for allowing the authors to conduct a few experiments in his laboratory.

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society. G. Tsoumpekos was a member of the International Max Planck Research School for Cell, Developmental, and Systems Biology and a doctoral student at Technische Universität Dresden.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: G. Tsoumpekos designed and performed the experiments, interpreted the results, and was involved in writing the manuscript. L. Nemetschke performed the genetic screen and the initial interaction studies and was involved in editing the manuscript. E. Knust conceptualized the goal, supported data interpretation, wrote and edited the manuscript, and acquired funding.

References

- Aldaz S., Escudero L.M., and Freeman M.. 2013. Dual role of myosin II during Drosophila imaginal disc metamorphosis. Nat. Commun. 4:1761 10.1038/ncomms2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliee M., Röper J.C., Landsberg K.P., Pentzold C., Widmann T.J., Jülicher F., and Dahmann C.. 2012. Physical mechanisms shaping the Drosophila dorsoventral compartment boundary. Curr. Biol. 22:967–976. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amândio A.R., Gaspar P., Whited J.L., and Janody F.. 2014. Subunits of the Drosophila actin-capping protein heterodimer regulate each other at multiple levels. PLoS One. 9:e96326 10.1371/journal.pone.0096326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M., Nakayama M., and Kaibuchi K.. 2010. Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 67:545–554. 10.1002/cm.20472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona M., Panciera T., Manfrin A., Giulitti S., Michielin F., Elvassore N., Dupont S., and Piccolo S.. 2013. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 154:1047–1059. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranjuez G., Kudlaty E., Longworth M.S., and McDonald J.A.. 2012. On the role of PDZ domain-encoding genes in Drosophila border cell migration. G3 (Bethesda). 2:1379–1391. 10.1534/g3.112.004093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouel C., Garg A., and McNeill H.. 2009. Herding Hippos: regulating growth in flies and man. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21:837–843. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnay F., Cohen-Berros E., Hoffmann M., Kim S.Y., Boulianne G.L., Hoffmann J.A., Matt N., and Reichhart J.M.. 2013. big bang gene modulates gut immune tolerance in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:2957–2962. 10.1073/pnas.1221910110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Kreko T., Davison H., Cusmano T., Wu Y., Rothenfluh A., and Eaton B.A.. 2013. Normal dynactin complex function during synapse growth in Drosophila requires membrane binding by Arfaptin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24:1749–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W., Acharya B.R., Peyret G., Fardin M.A., Mège R.M., Ladoux B., Yap A.S., Fanning A.S., and Peifer M.. 2016. Remodeling the zonula adherens in response to tension and the role of afadin in this response. J. Cell Biol. 213:243–260. 10.1083/jcb.201506115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A.G., Wartlick O., Salbreux G., and Paluch E.K.. 2014. Stresses at the cell surface during animal cell morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 24:R484–R494. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombelli J., and Solon J.. 2013. Force communication in multicellular tissues addressed by laser nanosurgery. Cell Tissue Res. 352:133–147. 10.1007/s00441-012-1445-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Wang W., Yu J., Zheng Y., Qing Y., and Pan D.. 2015. Spectrin regulates Hippo signaling by modulating cortical actomyosin activity. eLife. 4:e06567 10.7554/eLife.06567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S. 2016. Role of YAP/TAZ in cell-matrix adhesion-mediated signalling and mechanotransduction. Exp. Cell Res. 343:42–53. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S., Morsut L., Aragona M., Enzo E., Giulitti S., Cordenonsi M., Zanconato F., Le Digabel J., Forcato M., Bicciato S., et al. 2011. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 474:179–183. 10.1038/nature10137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K.A., and Kiehart D.P.. 1996. Drosophila nonmuscle myosin II has multiple essential roles in imaginal disc and egg chamber morphogenesis. Development. 122:1499–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbediwy A., Vincent-Mistiaen Z.I., and Thompson B.J.. 2016. YAP and TAZ in epithelial stem cells: A sensor for cell polarity, mechanical forces and tissue damage. BioEssays. 38:644–653. 10.1002/bies.201600037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadifar R., Röper J.C., Aigouy B., Eaton S., and Jülicher F.. 2007. The influence of cell mechanics, cell-cell interactions, and proliferation on epithelial packing. Curr. Biol. 17:2095–2104. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández B.G., Gaspar P., Brás-Pereira C., Jezowska B., Rebelo S.R., and Janody F.. 2011. Actin-Capping Protein and the Hippo pathway regulate F-actin and tissue growth in Drosophila. Development. 138:2337–2346. 10.1242/dev.063545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Edmondson M., and Sudol M.. 2016. Framework to function: mechanosensitive regulators of gene transcription. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 21:28 10.1186/s11658-016-0028-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher G.C., Elbediwy A., Khanal I., Ribeiro P.S., Tapon N., and Thompson B.J.. 2015. The Spectrin cytoskeleton regulates the Hippo signalling pathway. EMBO J. 34:940–954. 10.15252/embj.201489642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K.T., Yamashita K., Sakurai N., and Ohno S.. 2017. The Epithelial Circumferential Actin Belt Regulates YAP/TAZ through Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling of Merlin. Cell Reports. 20:1435–1447. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P., and Tapon N.. 2014. Sensing the local environment: actin architecture and Hippo signalling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 31:74–83. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P., Holder M.V., Aerne B.L., Janody F., and Tapon N.. 2015. Zyxin antagonizes the FERM protein expanded to couple F-actin and Yorkie-dependent organ growth. Curr. Biol. 25:679–689. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G., Dupont S., and Piccolo S.. 2012. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:591–600. 10.1038/nrm3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan I.K. 2015. Organ Size Control: Lessons from Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 34:255–265. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D.E. 2006. Mechanical control of tissue morphogenesis during embryological development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 50:255–266. 10.1387/ijdb.052044di [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karess R.E., Chang X.J., Edwards K.A., Kulkarni S., Aguilera I., and Kiehart D.P.. 1991. The regulatory light chain of nonmuscle myosin is encoded by spaghetti-squash, a gene required for cytokinesis in Drosophila. Cell. 65:1177–1189. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90013-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Renihan M.K., and Boulianne G.L.. 2006. Characterization of big bang, a novel gene encoding for PDZ domain-containing proteins that are dynamically expressed throughout Drosophila development. Gene Expr. Patterns. 6:504–518. 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg K.P., Farhadifar R., Ranft J., Umetsu D., Widmann T.J., Bittig T., Said A., Jülicher F., and Dahmann C.. 2009. Increased cell bond tension governs cell sorting at the Drosophila anteroposterior compartment boundary. Curr. Biol. 19:1950–1955. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGoff L., and Lecuit T.. 2016. Mechanical Forces and Growth in Animal Tissues. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8:a019232 10.1101/cshperspect.a019232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lye C.M., and Sanson B.. 2011. Tension and epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila early embryos. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 95:145–187. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385065-2.00005-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka B., Czogalla A., Hryniewicz-Jankowska A., Boguslawska D.M., Grochowalska R., Heger E., and Sikorski A.F.. 2014. Spectrins: a structural platform for stabilization and activation of membrane channels, receptors and transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1838:620–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Tournier A.L., Bates P.A., Gale J.E., Tapon N., and Thompson B.J.. 2011. Planar polarization of the atypical myosin Dachs orients cell divisions in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 25:131–136. 10.1101/gad.610511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Tournier A.L., Hoppe A., Kester L., Thompson B.J., and Tapon N.. 2013. Differential proliferation rates generate patterns of mechanical tension that orient tissue growth. EMBO J. 32:2790–2803. 10.1038/emboj.2013.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milán M., Campuzano S., and García-Bellido A.. 1997. Developmental parameters of cell death in the wing disc of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:5691–5696. 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemetschke L., and Knust E.. 2016. Drosophila Crumbs prevents ectopic Notch activation in developing wings by inhibiting ligand-independent endocytosis. Development. 143:4543–4553. 10.1242/dev.141762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo S., Dupont S., and Cordenonsi M.. 2014. The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol. Rev. 94:1287–1312. 10.1152/physrev.00005.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C., Pan G., Reddy B.V., Oh H., and Irvine K.D.. 2011. Zyxin links fat signaling to the hippo pathway. PLoS Biol. 9:e1000624 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C., Sun S., Sun G., Pan Y., and Irvine K.D.. 2014. Cytoskeletal tension inhibits Hippo signaling through an Ajuba-Warts complex. Cell. 158:143–156. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh M.H., and Margolis B.. 2003. Composition and function of PDZ protein complexes during cell polarization. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 285:F377–F387. 10.1152/ajprenal.00086.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper K. 2015. Integration of cell-cell adhesion and contractile actomyosin activity during morphogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 112:103–127. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A., Vlassaks E., Pichaud F., and Baum B.. 2015. Ect2/Pbl acts via Rho and polarity proteins to direct the assembly of an isotropic actomyosin cortex upon mitotic entry. Dev. Cell. 32:604–616. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royou A., Field C., Sisson J.C., Sullivan W., and Karess R.. 2004. Reassessing the role and dynamics of nonmuscle myosin II during furrow formation in early Drosophila embryos. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:838–850. 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansores-Garcia L., Bossuyt W., Wada K., Yonemura S., Tao C., Sasaki H., and Halder G.. 2011. Modulating F-actin organization induces organ growth by affecting the Hippo pathway. EMBO J. 30:2325–2335. 10.1038/emboj.2011.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluck T., Nienhaus U., Aegerter-Wilmsen T., and Aegerter C.M.. 2013. Mechanical control of organ size in the development of the Drosophila wing disc. PLoS One. 8:e76171 10.1371/journal.pone.0076171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., and Sala C.. 2001. PDZ domains and the organization of supramolecular complexes. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24:1–29. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro D., Tapia R., Pulimeno P., and Citi S.. 2012. The control of gene expression and cell proliferation by the epithelial apical junctional complex. Essays Biochem. 53:83–93. 10.1042/bse0530083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiah V.K., Kranjec C., Thomas M., and Banks L.. 2011. PDZ domains: the building blocks regulating tumorigenesis. Biochem. J. 439:195–205. 10.1042/BJ20110903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., and Irvine K.D.. 2016. Cellular Organization and Cytoskeletal Regulation of the Hippo Signaling Network. Trends Cell Biol. 26:694–704. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoumpekos G.2016. big bang, a novel regulator of tissue growth in Drosophila melanogaster. PhD thesis. Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Umetsu D., and Dahmann C.. 2015. Signals and mechanics shaping compartment boundaries in Drosophila. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 4:407–417. 10.1002/wdev.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez C.G., and Martin A.C.. 2016. Force transmission in epithelial tissues. Dev. Dyn. 245:361–371. 10.1002/dvdy.24384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K., Itoga K., Okano T., Yonemura S., and Sasaki H.. 2011. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development. 138:3907–3914. 10.1242/dev.070987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C.G., Wang B., Ballew A., Royou A., Karess R., Axelrod J.D., and Luo L.. 2001. Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) links Frizzled-mediated planar cell polarity signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell. 105:81–91. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00298-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F., and Zhang M.. 2013. Structures and target recognition modes of PDZ domains: recurring themes and emerging pictures. Biochem. J. 455:1–14. 10.1042/BJ20130783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F.X., and Guan K.L.. 2013. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 27:355–371. 10.1101/gad.210773.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., and Wang W.. 2003. Organization of signaling complexes by PDZ-domain scaffold proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 36:530–538. 10.1021/ar020210b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Gally C., and Labouesse M.. 2010. Tissue morphogenesis: how multiple cells cooperate to generate a tissue. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22:575–582. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.