Abstract

Given the prevalence and impact of childhood food allergy, there is increasing interest in interventions targeting disease prevention. Although interventions such as early introduction of dietary peanut have demonstrated efficacy in a small number of well-conducted randomized clinical trials, evidence for broader effectiveness and successful implementation at a population level is still lacking, although epidemiological data suggest that such strategies are likely to be successful, at least for peanut. In this commentary, we explore the issues of translating evidence of efficacy studies (performed under optimal conditions) to make policy recommendations at a population level, and highlight potential benefits, harms, and unintended consequences of making population-based recommendations on the basis of randomized controlled trials. We discuss the complexity and barriers to effective primary and secondary prevention intervention implementation in resource-poor settings.

Key words: Allergy, Prevention, Peanut, Translation, Implementation

Abbreviations used: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; LEAP, Learning Early About Peanut; NNT, Number needed to treat; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; WAO, World Allergy Organization

Information for Category 1 CME Credit.

Credit can now be obtained, free for a limited time, by reading the review articles in this issue. Please note the following instructions.

Method of Physician Participation in Learning Process: The core material for these activities can be read in this issue of the Journal or online at the JACI: In Practice Web site: www.jaci-inpractice.org/. The accompanying tests may only be submitted online at www.jaci-inpractice.org/. Fax or other copies will not be accepted.

Date of Original Release: March 1, 2018. Credit may be obtained for these courses until February 28, 2019.

Copyright Statement: Copyright © 2018-2020. All rights reserved.

Overall Purpose/Goal: To provide excellent reviews on key aspects of allergic disease to those who research, treat, or manage allergic disease.

Target Audience: Physicians and researchers within the field of allergic disease.

Accreditation/Provider Statements and Credit Designation: The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The AAAAI designates this journal-based CME activity for 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

List of Design Committee Members: Paul J. Turner, FRACP, PhD, Dianne E. Campbell, FRACP, PhD, Robert J. Boyle, MB ChB, PhD, and Michael E. Levin, MD (authors); Michael Schatz, MD, MS (editor)

Learning objectives:

-

1.

To describe the issues in using study data to inform population-based interventions to prevent food allergy.

-

2.

To understand the need to distinguish between Efficacy trials (which might reflect ideal circumstances) and Effectiveness trials (which assess effect in the “real world”).

-

3.

To identify the current knowledge and evidence gaps in strategies that have been considered to potentially prevent food allergy at a population level.

Recognition of Commercial Support: This CME has not received external commercial support.

Disclosure of Relevant Financial Relationships with Commercial Interests: P. J. Turner has received consultancy fees from the UK Departments of Health with respect to primary prevention strategies for food allergy; co-authored guidance on primary prevention for the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology; was co-investigator on the Beating Egg Allergy (BEAT) study (a primary prevention trial for egg allergy) funded by the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation. D. E. Campbell is a member of the National Allergy Strategy working group to implement primary prevention food allergy strategies (funded by the Australian Federal Government); co-authored guidance from the Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy with respect to primary prevention; and was chief investigator for the BEAT study, funded by the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation. R. J. Boyle received consultancy fees by the UK Food Standards Agency to undertake a meta-analysis and systematic review of primary prevention strategies for food allergy. M. E. Levin has no relevant conflicts of interest to declare. M. Schatz discloses no relevant financial relationships.

The mainstay of food allergy management has been allergen avoidance and the provision of rescue medication in the event of accidental reactions. The lack of alternative robust treatment options, together with an increasing prevalence in many countries,1 has created a major public health concern. This has stimulated research into the processes underlying the development of food allergy, with the aim of identifying effective prevention strategies. Such strategies may be population based or targeted to an individual, and can be divided into primary prevention (which aim to prevent disease before its onset) and secondary prevention (where early signs are targeted to mitigate or halt disease).2

Clinical trials are generally undertaken with significant resources, optimal conditions, and homogeneous participants with limited geographical and environmental variation. Such studies are efficacy trials—assessing the outcome of an intervention under ideal conditions. This is in contrast to effectiveness trials, which are performed under real-life, pragmatic conditions. It is insufficient to demonstrate that an intervention is successful within the confines of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to ensure that it will be an effective intervention across the population at large.3 Population-based interventions need to be assessed not only for level of evidence, applicability, and feasibility before recommendations are made, but they also need to be evaluated once implemented, such that their actual impact, and any unintended consequences (or harm), can be determined.

In this commentary, we discuss the main challenges and risks of using data from efficacy trials to develop public health interventions appropriate to the general population, and explore barriers to the successful implementation of measures to reduce the community burden of food allergy.

Assessing the Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations

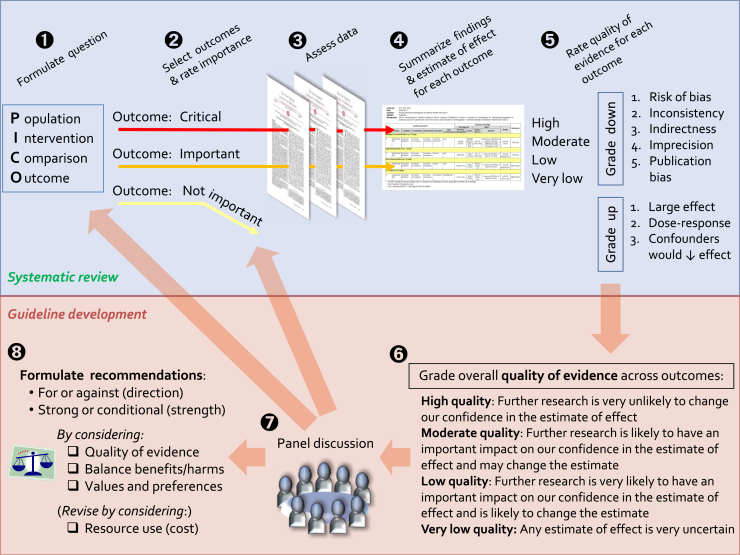

The first requirement for any disease prevention program is ensuring the sensible and accurate translation of evidence arising from clinical trials into public health recommendations and policy. This is a complex process that is best approached in a systematic way. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group has developed a commonly used tool to evaluate the certainty of findings arising from a systematic review of the evidence,4, 5 and a separate tool to assist with making recommendations for treatment, diagnosis, or prevention.6 These are summarized in Figure 1. In brief, the available evidence for each outcome of interest is first assessed for quality, from very low to high, according to the confidence in the evidence. This may be downgraded because of variety of reasons as outlined in Table I. Once the quality of the evidence has been assessed and considered sufficiently robust to merit consideration for translation, the applicability to the wider population must then be evaluated (Table II). A strong recommendation would be appropriate when most patients (or their families) would want the intervention, where the majority of clinicians agree that the intervention should be offered, and where the recommendations are acceptable as a public health measure to policy makers.8

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the GRADE approach for synthesizing evidence and developing recommendations.

Adapted with permission from: Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from: www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook. Accessed January 23, 2018.

Table I.

Factors that reduce the confidence in evidence for primary prevention strategies—as applicable to studies assessing the impact of early introduction of allergen into the diet for primary prevention

| Factor | Examples |

|---|---|

| Study limitations |

|

| Inconsistent results |

|

| Indirectness of evidence |

|

| Imprecision |

|

| Publication bias |

|

PP, Primary prevention.

Table II.

Applying the evidence to the population

| Individual | At-risk population | Wider population | Health system and public health recommendations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priority of the problem | High if family history | High | Possibly lower. | Low priority compared with other health conditions |

| Applicability/generalizability of the evidence | High—where evidence is from studies in high-risk populations | Less applicable to lower risk groups, as the effect of intervention is less | ||

| Benefits vs harms | Benefits likely to outweigh harms, with a smaller NNT to achieve benefit | Benefits may be less likely to outweigh harms, with a larger NNT to achieve benefit and other unseen consequences of intervention becoming more important | ||

| Resource use | Are the out-of-pocket costs relative to the benefits in favor of the intervention? | Does the cost-effectiveness of the intervention favor the intervention? | Is the intervention cost-effective compared with other public health interventions? | |

| Equity | What is the impact on health equity? | |||

| Acceptability | Is the intervention acceptable to the individual, their carers, and health care provider? | Is the intervention acceptable to key stakeholders? | Is the intervention more acceptable than alternatives including health interventions for other diseases? | |

| Feasibility | Is the intervention feasible to the individual, their carers, and health care provider? | Is the intervention feasible to a high-risk population, their carers, and health care provider? | Is the intervention feasible to implement at a public health level? | |

NNT, Number needed to treat.

Adapted from Alonso-Coello et al.6

The GRADE framework has been used by the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma group and working groups within the World Allergy Organization (WAO),9 and by WAO to make recommendations regarding the use of probiotics for allergic disease prevention.10 However, with respect to food allergy prevention, although there have been several recommendations arising from national specialist organizations, it is not clear that any of these have yet undertaken this robust approach to formulating recommendations to be implemented at a population level.

Intervention Strategies for Prevention of Food Allergy

Table III summarizes existing synthesized evidence for food allergy prevention interventions of current high interest using the GRADE approach. Although it is beyond the scope of this review to discuss each intervention in detail, there are only a few interventions that currently have sufficient evidence to warrant consideration as a population-based implementation. These include early introduction of peanut and egg to the infant diet,17 maternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and lactation,10 and maternal fish oil supplementation during pregnancy.11, 12, 14 The remainder of the synthesized evidence to date shows low or no evidence when assessed using the GRADE approach,13, 15, 16, 18, 19 including allergen avoidance during pregnancy and lactation.11, 12, 13 We do not discuss probiotics or fish oil further in this commentary, because the evidence for their effectiveness is of either indirect or low quality (Table III) and neither are widely recommended for food allergy prevention in most current guidelines.

Table III.

Assessment of synthesized evidence for prevention of food allergy using the GRADE approach

| Strategy | Effect size | GRADE quality of evidence | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal | |||

| • Maternal allergen avoidance | No evidence that maternal allergen avoidance is effective in reducing FA or sensitization11, 12, 13 | No evidence | There is increasing evidence that maternal avoidance increases the risk of allergic sensitization and food allergy in offspring |

| • Maternal fish oil supplementation | Fish oil reduces sensitization to egg: RR 0.55 [95% CI 0.40-0.76]11, 12, 14 Fish oil reduces sensitization to peanut: RR 0.62 [95% CI 0.40-0.96]11, 12, 14 |

⊗ ⊗ ⊗ ○ Moderate | Evidence downgraded for indirectness: no evidence of the impact on FA outcomes (as opposed to sensitization). However, recommendation is cheap and acceptable |

| • Maternal probiotics | No evidence10, 11, 12 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | Poor study quality, indirect outcome, inconsistent with data related to other outcomes |

| During lactation | |||

| • Maternal allergen avoidance | No evidence to suggest avoidance is an effective strategy11, 12, 13 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | |

| • Maternal probiotics | No evidence that probiotics influence risk of food allergy10, 11, 12 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | |

| • Maternal fish oil | No evidence11, 12, 14 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | Most studies assessed fish oil supplementation during pregnancy ± lactation |

| Infant feeding | |||

| • Hypoallergenic formula | No consistent evidence that partially or extensively hydrolyzed formula reduces risk15 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | |

| • Infant prebiotics | No evidence that prebiotics reduce the risk of atopic disease or food allergy: data sparse11, 12, 16 | ○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence | |

| • Infant probiotics | Probiotics may reduce sensitization to cow's milk but not other allergens: RR 0.60 [0.37-0.96]10, 11, 12 | ⊗ ⊗ ○ ○ Low | These trials used a combination of maternal and infant supplementation interventions; it is unclear as to the relative effects of each of these in isolation. Evidence downgraded for indirectness and imprecision |

| • Age of introduction of allergenic foods | Introduction of egg from 4 to 6 mo reduces the risk of egg allergy: RR 0.56 [95% CI 0.36-0.87]17 Introduction of peanut from 4 to 11 mo reduces the risk of peanut allergy: RR 0.29 [95% CI 0.11-0.74]17 |

⊗ ⊗ ⊗ ○ Moderate ⊗ ⊗ ⊗ ○ Moderate |

Reduced because of indirectness of evidence (some studies only recruited infants without any sensitization, thus excluding already-sensitized infants) Evidence downgraded for imprecision and indirectness (control intervention, ie, peanut avoidance to age 5 y is not representative of population norms), but increased due to strength of effect |

| Other | |||

| • Skin interventions∗ | No evidence that skin care impacts on FA or sensitization: RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.58, 1.46) for sIgE to egg >0.35 kU/L18 RR 0.45 (95% CI 0.13-1.61) for positive SPT to a food allergen at 12 mo19 |

○ ○ ○ ○ No evidence |

CI, Confidence interval; FA, food allergy; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; RR, risk ratio; SPT, skin prick test.

Not synthesized data.

Generalizability of Evidence

Generalizability is a primary limitation of the early allergenic food introduction trials,14 particularly for peanut. The evidence that early peanut introduction reduces the risk of peanut allergy is largely derived from a single study, the Learning Early About Peanut (LEAP) study.20 In this single-center study, treatment compliance was very high, and the advice given to the control group (complete peanut avoidance until age 5 years) is not consistent with current advice in most countries. This is relevant when attempting to apply the results of LEAP to a general population, where levels of compliance with the active intervention are likely to be lower than they were in the original trial,21 and the “no intervention” option is not equivalent to strict avoidance of peanut to age 5 years.22 Evidence of efficacy for early introduction of egg comes from a number of RCTs that have been the subject of meta-analysis.17 The risk ratio for the impact of early egg introduction on the risk of egg allergy is surprisingly consistent across those trials completed to date, despite differences in intervention, timing of introduction, and the population studies. In contrast, there is significant variation in adverse events according to the nature of the intervention (ie, boiled egg vs raw egg powder). So for egg, there appears to be less of an issue with regard to efficacy outcomes, but a question over generalizability in terms of how the formulation of egg (boiled, raw egg powder, etc.) impacts on the frequency and nature of adverse events.

The impact of any given intervention is closely related to the risk of developing food allergy in the population under study. On the basis of a recent systematic review,17 the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent a single case of egg allergy is relatively high in an unselected population, but lower for infants with early onset moderate-severe eczema—a group at higher risk for egg allergy23 (Table IVA). Data for peanut are more sparse, because they are derived in the main from a single trial (LEAP) and because peanut allergy is less common than egg allergy. However, the picture is similar: early introduction in an unselected population requires a relatively large number needed to treat, compared with a population of infants with early onset moderate-severe eczema and/or egg allergy (Table IVB). However, the well-described “prevention paradox” acknowledges that effective population-based interventions are generally more useful than those that target specific at-risk groups—where interventions can achieve large overall health gains for whole populations but may offer only small advantages to each individual.24

Table IV.

Number needed to treat with early introduction of egg and peanut, stratified by risk

| Population | Control risk/1000 infants | Intervention risk/1000 infants | Risk difference | 95% CI | Number needed to treat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Absolute risk differences for different populations associated with early introduction of egg | |||||

| Normal risk∗ | 54 | 30 | 24 | 7-35 | 42 (29-143) |

| High risk† | 100 | 56 | 44 | 13-64 | 23 (16-77) |

| Very high risk‡ | 500 | 280 | 220 | 65-320 | 5 (3-15) |

| (B) Absolute risk differences for different populations associated with early introduction of peanut | |||||

| Normal risk∗ | 25 | 7 | 18 | 6-22 | 56 (45-167) |

| High risk‡ | 170 | 49 | 121 | 44-151 | 8 (7-23) |

Control risks are estimated from included studies or when relevant from other large population-based studies for populations at different risks of the outcome.17

CI, Confidence interval.

Risk refers to the unselected population of infants.

Infants at a high hereditary risk of allergic disease.

Infants with moderate-to-severe eczema.

Applicability—Variations in Populations and Setting

Food allergy prevention research has largely been conducted in resource-rich settings with a high prevalence of food allergy. This poses considerable challenges when extrapolating these data to other settings,25 not just in terms of resources and acceptability (as discussed below) but also in the assessment of the effect. Simply put, the impact of an intervention depends on the local prevalence of food allergy, whether the “proven” intervention is efficacious in the population in question, and if it can be effectively implemented in the setting.

Epidemiological data on food allergy prevalence is limited in many regions,1 and confounded by differences in methods of diagnosis and bias due to sampling specialized populations or low response rates. The most rigorous data, based on food challenges in unselected populations, are only available for the USA, Europe, China, Thailand, Australia, and South Africa.26 Lower rates of background risk reduce the impact of interventions, increasing the NNT, although there are data to suggest that the prevalence of food allergy in low-middle income countries may be increasing to similar levels as high-income countries,27 as these countries undergo modernization and expose the population to more proinflammatory predisposing factors and less rural, protective factors. Primary prevention strategies impact on the processes that lead to sensitization and onward to clinical reactivity, but these same processes are affected by urbanization,28 socioeconomic class,29 ethnicity,30 and migration patterns.31, 32 These factors all increase the uncertainty of effect when extrapolating data from research to other populations.

Unintended Consequences of Community-Based Prevention Strategies

Although food allergy prevention is a clear benefit of any given intervention, less is understood about the potential harm that might result from population-based policies. The medium-to long-term impact of early allergen introduction on maternal and child health outcomes has not been fully assessed, and is potentially of greater concern in low-medium income settings. Although beneficial effects have been shown for the prevention of a specific food allergy in the child administered the intervention, it is not clear whether the overall benefit of the intervention outweighs the burden of treatment, and whether there are adverse effects for the child or other household members.

Exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life (and by definition, delayed introduction of solids and other liquids) is the current World Health Organization advice irrespective of the geographical region. Whilst early food introduction strategies do not promote early cessation of breastfeeding, the duration of exclusive breastfeeding is clearly reduced and there may be a reduction in the overall duration of breastfeeding, although this has not been observed when examined in the context of RCTs to date.33, 34 The benefits of breastfeeding are clear, with a significant reduction in the risk of infant otitis media, lower respiratory tract infections, gastroenteritis, with possible beneficial effects on child intelligence and adult economic productivity, reduced obesity, and incidence of diabetes.35 There is evidence that “partial breastfeeding” (the combination of breastfeeding with other fluids or solids) is less effective at protection against childhood infections than exclusive breastfeeding,36 and that partial breastfeeding is high-risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission.37 This is likely to be particularly relevant in low-medium income settings such as Africa and Asia, where infant mortality and morbidity from infections remains high, and where a large proportion of the world's population reside. At the same time, background rates of food allergy are lower in these areas, so the population-level benefit of interventions to prevent food allergy is less. In those regions where food allergy is increasing, along with conditions associated with poverty such as HIV and malnutrition, there is a significant challenge in devising infant feeding strategies for atopic children: public health advice to introduce complementary foods early may be ill-advised and an individualized approach may be required.38

Concerns have also been raised as to the consequences of displacement of breast milk and weaning foods by high-calorie foods such as peanut and egg. Data from the LEAP,20, 39 Enquiring About Tolerance,33, 40 and Beating Egg Allergy34, 41 studies do not indicate any significant short-term detrimental effects on growth33, 34, 39; however, these studies were conducted in highly selected and motivated families largely from higher socioeconomic backgrounds with higher levels of education, in resource-rich settings. Whether a similar neutral impact would be seen at a population level, in the absence of the monitoring and advice available within a clinical trial, is unclear and of significant concern. A UK government risk assessment also considered toxicological issues as a potential risk—for example, aflatoxin (peanut) or salmonella (egg) exposure to very young infants with early allergen exposure,22 which illustrates the need to consider potential risks beyond those which may seem relevant to the allergy community.

Another possible unintended harmful consequence of food allergy prevention through early exposure to allergenic foods is screening. Screening has been proposed as an important step before early introduction.42 However, there are considerable logistical risks to the resourcing of such a recommendation, as we have outlined before, which might impact on the benefit of early introduction and cause harm, by delaying the timing of introduction.43 It is not inconceivable that parents might be deterred by a screening and introduction process, due to limited financial resources or access to screening/supervised introduction, or out of fear they have missed a crucial window of opportunity to introduce the food. This would result in a paradoxical effect, where overproscriptive guidelines to support early introduction have the opposite effect and increase the risk of food allergy in later life.

Feasibility, Equity and Resource Use

The most successful examples of population-based intervention include those that require little active participation from the population, such as water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries and vitamin fortification of staple foods. In both cases, large proportions of the population receive the intervention regardless of risk stratification for disease or even personal knowledge. Other successful interventions where a higher level of active participation is required have achieved large population uptake in many regions. Examples include folate supplementation in pregnancy, neonatal vitamin K administration, and childhood vaccination. Success has been achieved by the incorporation of interventions into standard models of care, with opt-out (rather than opt-in) policies, or by linking participation with the intervention to a desired resource (eg, school enrolment, childcare, or welfare support payments being linked to vaccination).

Strategies that require individual “screening” to assess suitability of an intervention (such as those recommended by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases42 before the introduction of peanut into the infant diet) increase the resource needed for implementation, may delay timing of the intervention, and also exacerbate issues of equity of access and resource. This can also impact on the effectiveness of an intervention: for example, families may have to wait many months for “screening” because of a lack of access or ability to finance health services, which in turn delays the timing of early introduction and therefore its effectiveness. Moreover, with respect to food allergy prevention, the arguments for “screening” currently lack a fundamental evidence base of efficacy and cost-effectiveness.

Resources vary considerably from one country to another, and even within the same country. The substantial disparity in health outcomes between countries of differing socioeconomic status requires attention to those disorders contributing most to the burden of disease in lower-middle income countries. Moreover, in less developed settings, lower public awareness of food allergy and under-awareness of health care providers, together with competing demands on the health system, will result in altered health and prevention priorities for individuals and for governments in these settings.26 Acceptability of food allergy primary prevention strategies in these settings may also be reduced.

Evaluating Prevention Recommendations and Policies: Lessons and Future Directions

An intervention may be based on high-quality evidence that in turn drives a strong recommendation for implementation, can appear applicable and feasible, and yet still not be effective across a population. This can be due to failure of implementation, or unforeseen lack of effectiveness at a population level. Thorough evaluation of population-targeted prevention strategies is therefore crucial in determining real-life effectiveness and in identifying unintended consequences and harms. Public-health recommendations should never be made with a “let's try it and see…” approach: an intervention must have a coherent plan for evaluation included in the implementation plan.44

The universal or opt-in models presented above for health prevention (water fluoridation, vitamin fortification of foods, etc.) are unlikely to be applicable to the current proven interventions available for primary prevention of food allergy at a population level. As shown in Table III, high-quality RCT evidence for prevention strategies is currently limited to early introduction of peanut and egg into the diet of infants, with the most marked effects confined to a high risk population. Evidence may emerge of interventions that may be more amenable to passive population-based implementation, but the current proven strategy requires high levels of active participation and effective dissemination of information and education. This does not bode well, as the evidence is that population-based interventions that require high levels of participant participation and population-wide education are in general ineffective: for example, smoking, obesity, and skin cancer prevention interventions have been largely disappointing.

On the other hand, the current evidence for earlier introduction of peanut and egg is also consistent with the existing epidemiological data that delaying these allergens into the infant diet increases the risk of developing allergy to these foods.11, 12 The original basis for LEAP came from epidemiological comparisons in peanut consumption (and specifically, age of introduction) between Israel and the UK.20 Strategies that seek to reverse previous advice to delay introduction (such as that recommended by ASCIA in Australia)45 may be more successful at a population level than attempts to actively promote “early” introduction.

Looking specifically at uptake of current and past infant feeding guidelines, the evidence that education and dissemination of feeding recommendations alone impacts on infant feeding practices is poor. Prior to the USA, Europe, the UK, and Australasia changing their infant feeding guidelines around 2008 (in response to emerging data from observational cohort studies that did not suggest a protective effect for the delayed introduction of allergenic food into infants' diet), there was population-based data to suggest that many families did not heed or follow this advice.46 Similarly, despite the near-universal recommendation to exclusively breastfeed for at least 4 months in high-income countries, only a relatively small proportion of mothers in these regions achieve this target. In the UK, 30% of infants had already had solids introduced into their diet by age 4 months, 75% by 5 months, and 94% by 6 months.47 In Australia, only 39% of infants were exclusively breastfed after 3 months of age in 2010.48

Specific recommendations for the prevention of peanut allergy have now been released in at least 2 regions, the USA42 and Australia.45 They vary considerably in their approach: one with a specific emphasis on screening for suitability (a high resource model), the other minimizing the role of screening and aiming for broader uptake. This creates an opportunity to examine how these different approaches will be taken up and accepted by the population at large, and whether they will be effective in reducing rates of peanut allergy. Now is the time to put in place robust systems for measuring uptake and outcome in these regions, so we can make clear assessments about the effectiveness of each approach and in turn inform implementation recommendations for other regions.

Summary

Public health strategies that require active participation from the community require individuals and families to not only know about changes in recommendations, but to knowingly alter behavior. This can be particularly difficult where infant feeding is concerned. There is little existing evidence that it is possible to achieve a widespread behavioral change in a complex area such as infant feeding, where so many cultural, resource, and emotional factors are at play.

Families vary in their preferences and perception of risk. Some may prioritize the introduction of food allergens early during weaning because of family history or a specific concern over the potential for food allergy. For others, the same specific drivers may increase anxiety over the potential for an allergic reaction, and interfere with their willingness to undertake early introduction. Such individual preferences will differ from health care professionals, who might be concerned as to their advice resulting in an allergic reaction, and policy makers who need to balance the risks of allergic reactions occurring in the community with the benefits on reducing the risk of food allergy.

It is insufficient for population-based interventions to be based on the highest level of evidence; they also need to be generalizable, simple, cheap, doable, and have the ability to be evaluated after implementation. There are few interventions at preventing food allergy that pass the high evidence bar, although this will hopefully change as more evidence is generated from studies of high quality in heterogeneous populations and across regions. Until then, we remain in a transitional phase: it therefore behooves us to exercise appropriate caution when developing and implementing strategies aimed at primary prevention of food allergy, at a population level.

Footnotes

P. J. Turner is in receipt of a Clinician Scientist award funded by the UK Medical Research Council (reference MR/K010468/1). P. J. Turner and R. J. Boyle are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Conflicts of interest: P. J. Turner has received consultancy fees from the UK Departments of Health with respect to primary prevention strategies for food allergy; co-authored guidance on primary prevention for the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology; was co-investigator on the Beating Egg Allergy (BEAT) study (a primary prevention trial for egg allergy) funded by the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation. D. E. Campbell is a member of the National Allergy Strategy working group to implement primary prevention food allergy strategies (funded by the Australian Federal Government); co-authored guidance from the Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy with respect to primary prevention; and was chief investigator for the BEAT study, funded by the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation. R. J. Boyle received consultancy fees by the UK Food Standards Agency to undertake a meta-analysis and systematic review of primary prevention strategies for food allergy. M. E. Levin has no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Prescott S.L., Padania R., Allen K.J., Campbell D.E., Sinn J., Fiocchi A. A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. World Allergy Organ J. 2013;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Health promotion and disease prevention through population-based interventions, including action to address social determinants and health inequity. http://www.emro.who.int/about-who/public-health-functions/health-promotion-disease-prevention.html Available from: Accessed December 11, 2017.

- 3.Rothwell P.M. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., Kunz R., Falck-Ytter Y., Alonso-Coello P. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brozek J.L., Akl E.A., Alonso-Coello P., Lang D., Jaeschke R., Williams J.W. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines. Part 1 of 3. An overview of the GRADE approach and grading quality of evidence about interventions. Allergy. 2009;64:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso-Coello P., Schunemann H.J., Moberg J., Brignardello-Petersen R., Akl E.A., Davoli M. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassler D., Briel M., Montori V.M., Lane M., Glasziou P., Zhou Q. Stopping randomized trials early for benefit and estimation of treatment effects: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1180–1187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Kunz R., Falck-Ytter Y., Vist G.E., Liberati A., GRADE Working Group Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brozek J.L., Akl E.A., Compalati E., Kreis J., Terracciano L., Fiocchi A. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines part 3 of 3. The GRADE approach to developing recommendations. Allergy. 2011;66:588–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiocchi A., Pawankar R., Cuello-Garcia C., Ahn K., Al-Hammadi S., Agarwal A. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): probiotics. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silva D., Geromi M., Halken S., Host A., Panesar S.S., Muraro A. on behalf of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Primary prevention of food allergy in children and adults: systematic review. Allergy. 2014;69:581–589. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Larsen V, Ierodiakonou D, Jarrold K, Cunha S, Chivinge J, Robinson Z, et al. Diet during pregnancy and infancy, and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kramer M.S., Kakuma R. Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD000133. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000133.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Best K.P., Gold M., Kennedy D., Martin J., Makrides M. Omega-3 long-chain PUFA intake during pregnancy and allergic disease outcomes in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:128–143. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.111104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle R.J., Ierodiakonou D., Khan T., Chivinge J., Robinson Z., Geoghegan N. Hydrolysed formula and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;352:i974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuello-Garcia C.A., Fiocchi A., Pawankar R., Yepes-Nuñez J.J., Morgano G.P., Zhang Y. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): prebiotics. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:10. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0102-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ierodiakonou D., Garcia-Larsen V., Logan A., Groome A., Cunha S., Chivinge J. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1181–1192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horimukai K., Morita K., Narita M., Kondo M., Kitazawa H., Nozaki M. Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:824–830.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe A.J., Su J.C., Allen K.J., Abramson M.J., Cranswick N., Robertson C.F. A randomized trial of a barrier lipid replacement strategy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis and allergic sensitization: the PEBBLES pilot study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e19–e21. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Toit G., Roberts G., Sayre P.H., Bahnson H.T., Radulovic S., Santos A.F. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803–813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer D.J., Prescott S.L., Perkin M.R. Early introduction of food reduces food allergy—Pro and Con. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:214–221. doi: 10.1111/pai.12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint Statement from the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition and the Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer products and the Environment Assessing the health benefits and risks of the introduction of peanut and hen's egg into the infant diet before six months of age in the UK. Food Standards Agency. 2016. https://cot.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/jointsacncotallergystatementfinal2.pdf Available from: Accessed December 11, 2017.

- 23.Martin P.E., Eckert J.K., Koplin J.J., Lowe A.J., Gurrin L.C., Dharmage S.C. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? Results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:255–264. doi: 10.1111/cea.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . 2002. Choosing Priority Strategies for Risk Prevention. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/chapter6/en/index1.html. Accessed December 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray C.L. Epidemiology of food allergy. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;27:334–337. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin M.E., Gray C.L., Marrugo J. Food allergy: international and developing world perspectives. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2016;4:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prescott S., Allen K.J. Food allergy: riding the second wave of the allergy epidemic. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta R.S., Springston E.E., Smith B., Warrier M.R., Pongracic J., Holl J.L. Geographic variability of childhood food allergy in the United States. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51:856–861. doi: 10.1177/0009922812448526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta R.S., Springston E.E., Warrier M.R., Smith B., Kumar R., Pongracic J. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e9–e17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenhawt M., Weiss C., Conte M.L., Doucet M., Engler A., Camargo C.A., Jr. Racial and ethnic disparity in food allergy in the United States: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panjari M., Koplin J.J., Dharmage S.C., Peters R.L., Gurrin L.C., Sawyer S.M. Nut allergy prevalence and differences between Asian-born children and Australian-born children of Asian descent: a state-wide survey of children at primary school entry in Victoria, Australia. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:602–609. doi: 10.1111/cea.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koplin J.J., Peters R.L., Ponsonby A.L., Gurrin L.C., Hill D., Tang M.L. Increased risk of peanut allergy in infants of Asian-born parents compared to those of Australian-born parents. Allergy. 2014;69:1639–1647. doi: 10.1111/all.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkin M.R., Logan K., Marrs T., Radulovic S., Craven J., Flohr C. Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study: feasibility of an early allergenic food introduction regimen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1477–1486.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan J.W., Turner P.J., Valerio C., Sertori R., Barnes E.H., Campbell D.E. Striking the balance between primary prevention of allergic disease and optimal infant growth and nutrition. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:844–847. doi: 10.1111/pai.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Victora C.G., Bahl R., Barros A.J., Franca G.V., Horton S., Krasevec J. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankar M.J., Sinha B., Chowdhury R., Bhandari N., Taneja S., Martines J. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:3–13. doi: 10.1111/apa.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Becquet R., Bland R., Leroy V., Rollins N.C., Ekouevi D.K., Coutsoudis A. Duration, pattern of breastfeeding and postnatal transmission of HIV: pooled analysis of individual data from West and South African cohorts. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin M., Goga A., Doherty T., Coovadia H., Sanders D., Green R.J. Allergy and infant feeding guidelines in the context of resource-constrained settings. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:455–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feeney M., Du Toit G., Roberts G., Sayre P.H., Lawson K., Bahnson H.T. Immune Tolerance Network LEAP Study Team. Impact of peanut consumption in the LEAP study: feasibility, growth, and nutrition. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1108–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkin M.R., Logan K., Tseng A., Raji B., Ayis S., Peacock J. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1733–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan J.W., Valerio C., Barnes E.H., Turner P.J., Van Asperen P.A., Kakakios A.M. Beating Egg Allergy Trial (BEAT) Study Group. A randomized trial of egg introduction from 4 months of age in infants at risk for egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1621–1628.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Togias A., Cooper S.F., Acebal M.L., Assa'ad A., Baker J.R., Jr., Beck L.A. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner P.J., Campbell D.E. Implementing primary prevention for peanut allergy at a population level. JAMA. 2017;317:1111–1112. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glanz K., Bishop D.B. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Netting M.J., Campbell D.E., Koplin J.J., Beck K.M., McWilliam V., Dharmage S.C. Centre for Food and Allergy Research, the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, the National Allergy Strategy, and the Australian Infant Feeding Summit Consensus Group. An Australian Consensus on Infant Feeding Guidelines to Prevent Food Allergy: outcomes from the Australian Infant Feeding Summit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1617–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hourihane J.O., Aiken R., Briggs R., Gudgeon L.A., Grimshaw K.E., DunnGalvin A. The impact of government advice to pregnant mothers regarding peanut avoidance on the prevalence of peanut allergy in United Kingdom children at school entry. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1197–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) Infant Feeding Survey. 2010. http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB08694 Available from: Accessed December 11, 2017.

- 48.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) AIHW; Canberra, Australia: 2011. Australian National Infant Feeding Survey: Indicator Results. Report No.: Cat. no. PHE 156. [Google Scholar]